1. Introduction

In the nearly twenty years since the Organization for African Unity became the African Union (AU),Footnote 1 it seems the AU has been in a state of perpetual reorganization, expansion, or modification.Footnote 2 The pace of change has sometimes been dizzying. Just in 2016, the AU committed to creating the African Minerals Development Centre, the African CDC, the African Science Research and Innovation Council, the Pan African Intellectual Property Organization, the Africa Sports Council, and the African Observatory in Science Technology and Innovation.Footnote 3

But many of these institutions exist only on paper.Footnote 4 For example, the AU formally adopted a constitutive document for all of the organizations listed in the paragraph above, but those documents have not been ratified by enough member states for them to enter into force.Footnote 5 The result is that the organizations exist in limbo waiting for the state support they need to come into being. Once their constitutive documents come into force, the AU will still have to give them the resources they need to succeed.

Even some older institutions still exist only on paper. For example, the Protocol on the African Investment Bank (adopted 2009), the Agreement for the Establishment of the African Risk Capacity Agency (adopted 2012) and the Protocol on the Establishment of the African Monetary Fund (adopted 2014) have not been ratified by enough states to enter into force.Footnote 6 In fact, of the three financial institutions that were specifically listed in the AU’s Constitutive Act in 2001 as being core components of the AU,Footnote 7 none of them exist yet.Footnote 8 The repeated failure of the AU to create functioning institutions has raised legitimate questions about whether the AU has the political will and capacity to follow-through on its many commitments.Footnote 9

These questions about the AU’s ability and desire to create functioning institutions are particularly relevant to its recent adoption of the Malabo Protocol.Footnote 10 The Malabo Protocol adds an international criminal law component to the jurisdiction of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights (ACJHR).Footnote 11 The addition of criminal jurisdiction to the ACJHR represents a significant increase in the court’s subject matter jurisdiction.Footnote 12 It also greatly increases the difficulty of the court’s work and necessitates a more complex organizational structure.Footnote 13 But can this new and improved ACJHR be successful? Will the AU have the political will to make it a reality? This chapter argues that the resources that the AU eventually devotes to the ACJHR will shed light on whether to be hopeful or doubtful about the court’s eventual success.

Building a functioning international criminal court is not easy. It requires substantial investigative and adjudicative resources.Footnote 14 If the AU does not devote sufficient resources to the ACJHR, it will not be successful.Footnote 15 Of course, having sufficient resources is not a guarantee of success, but if the AU devotes sufficient resources to the international criminal law component of the ACJHR that would be a very hopeful sign. First and foremost, it would indicate that the AU is committed to the ACJHR’s success. This is incredibly important as the ACJHR will not be successful if it does not have the financial and political support of the AU.Footnote 16

Thus, this chapter will explore the resources that will be needed to give the ACJHR a functioning international criminal law component. The International Criminal Court (ICC) will be used as a comparator. The ICC has publicly released information about the resource requirements of its own work and that will form the basis for predicting the eventual requirements of the ACJHR. While it is impossible to know exactly what resources are needed to carry out the Malabo Protocol, this chapter estimates that a fully operational ACJHR will need about 370 full-time personnel and a budget of approximately 50 million euros per year.Footnote 17 It is unlikely that the Malabo Protocol can be successful in the long-run with dramatically fewer resources than this. When the Malabo Protocol comes into force, the resources that the AU devotes to its implementation will give us insight into whether the expanded ACJHR can be successful.

2. The Development of the AU’s Judicial Bodies

In general, the evolution of the AU’s judicial bodies looks similar to the rest of the AU in that they have undergone rapid and extensive changes.Footnote 18 It also looks similar to the rest of the AU in that there has been a lack of follow-through. The first judicial body within the AU was the African Court of Human and Peoples’ Rights (the ACHPR). It was created to foster the “attainment of the objectives of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights.”Footnote 19 The protocol establishing the ACHPR was opened for signature in June 1998 and entered into force in January 2008.Footnote 20

In addition, the AU’s Constitutive Act called for the establishment of a Court of JusticeFootnote 21 to serve as the “principal judicial organ” of the AU.Footnote 22 A protocol for the establishment of the African Court of Justice (ACJ) was adopted in July 2003 and entered into force in February 2009.Footnote 23 Almost as soon as the ACJ’s constitutive document had been adopted, the AU began talking about merging the ACHPR and the ACJ into a single court.Footnote 24 This was premised, at least in part, on the desire to reduce the cost of supporting two separate international courts.Footnote 25

In 2008, the AU issued the Protocol on the Statute of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights.Footnote 26 This protocol merges the two existing courts to create the ACJHR.Footnote 27 While the protocol to establish the ACJHR was adopted in 2008, it has never come into force. It requires fifteen ratifications to enter into force,Footnote 28 but has only been ratified by six states.Footnote 29

Yet even though the protocol establishing the ACJHR had not come into force, in 2009 the AU began discussing modifying the ACJHR to add an international criminal component.Footnote 30 This was driven largely by the indictment of African government officials by European states and the ICC.Footnote 31 The indictments were seen by the AU as inappropriate interference in African affairs.Footnote 32 By adding a criminal component to the ACJHR, the AU hoped to take control of the indictment and trial of African leaders.Footnote 33 These discussions culminated in 2014 in the adoption of the awkwardly-named Protocol on Amendments to the Protocol on the Statute of the African Court of Justice and Human rights (hereafter called the “Malabo Protocol” because it was adopted in the city of Malabo in Equatorial Guinea).Footnote 34 Entry into force of the Malabo Protocol requires fifteen ratifications,Footnote 35 but, as of July 2017, it had not been ratified by a single country.Footnote 36

The story of the AU’s judicial bodies has been one of over-commitment and under-delivery. Almost ten years ago, the AU decided to merge the ACHPR and the ACJ to form a single court – the ACJHR. Progress toward that goal has been slow. But despite the fact that the ACJHR had not been established yet, the AU almost immediately began discussions to greatly expand the planned ACJHR by adding an international criminal law component.

At the rate that ratifications are currently being received, it could be another five or ten years before the protocol establishing the ACJHR comes into force.Footnote 37 At that point, it would require another fifteen ratifications of the Malabo Protocol before the amendments to add a criminal component to the ACJHR would take effect. As a result, it is not clear when or if the Malabo Protocol will come into effect, but it is unlikely to occur in the near future.Footnote 38

3. A New African Criminal Court?

Assuming that, at some point in the future, the Malabo Protocol comes into force, what would happen? The Protocol makes a number of significant changes to the ACJHR. First, it alters the structure of the ACJHR. As originally conceived, the ACJHR would have two sections: a Human Rights Section that would hear all cases relating to “human and/or peoples’ rights” and a General Affairs Section that would hear all other eligible cases.Footnote 39 The Malabo Protocol adds a new International Criminal Law Section,Footnote 40 which has jurisdiction over “all cases relating to the crimes specified” in the statute.Footnote 41

The addition of a criminal component to the ACJHR required other structural changes. For example, it necessitates the creation of an Office of the Prosecutor, and a Defence Office.Footnote 42 The Office of the Prosecutor will be responsible for “the investigation and prosecution” of crimesFootnote 43 while the Defence Office will be responsible for “protecting the rights of the defence [and] providing support and assistance to defence counsel.”Footnote 44

The Malabo Protocol also lays out the crimes the expanded ACJHR will have jurisdiction over. First, it will have jurisdiction over the core crimes under international law: genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity.Footnote 45 It will also have jurisdiction over the crime of aggression.Footnote 46 The definitions of these four crimes appear to have been largely based on the definition of those crimes in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, although some changes have been made to expand them at the margins.Footnote 47 The ACJHR will also have jurisdiction over a number of crimes that are not within the jurisdiction of the ICC like piracy, terrorism, corruption, money laundering, drug trafficking, human trafficking, and the exploitation of natural resources.Footnote 48 These new crimes represent a potential source of problems as some of them do not have well-established definitions.Footnote 49

The overall result is a significant change in both structure and jurisdiction for the ACJHR. The resulting court will be unique in its attempt to incorporate the components of a regional international court, a human rights court, and an international criminal court into a single institution.Footnote 50 But will the new and expanded ACJHR be successful? This question will be explored below.

4. Between Hope and Doubt

The adoption of the Malabo Protocol has left many observers unsure whether to be hopeful or doubtful. On the one hand, there are reasons to be hopeful that the Malabo Protocol will make a positive impact.Footnote 51 First, having a regional court capable of investigating mass atrocities committed in Africa could help shrink the impunity gap on the continent.Footnote 52 Second, there may be some benefit in having cases arising out of African situations prosecuted in Africa.Footnote 53 Third, the Malabo Protocol will grant to the ACJHR the ability to prosecute some crimes that are outside the jurisdiction of the ICC, but are relevant in an African context.Footnote 54 Fourth, it says all the right things.Footnote 55 In the Preamble to the Malabo Protocol, the AU reiterated its commitment to “peace, security and stability on the continent” and to protecting human rights, the rule of law and good governance.Footnote 56 The members of the AU also stressed their “condemnation and rejection of impunity” and claimed that the changes in the Malabo Protocol will help “prevent[] serious and massive violations of human and peoples’ rights … and ensur[e] accountability for them wherever they occur.”Footnote 57 In short, the stated goals of the Malabo Protocol are very positive. They hold out hope of preventing atrocities and ensuring accountability. Thus, there are reasons to be hopeful.Footnote 58

On the other hand, there are also reasons to be doubtful.Footnote 59 The first concern is that the AU often appears to lack the political will and capacity to implement its vision for the organization.Footnote 60 This can be seen with the AU’s financial institutions. Despite being identified as key to the organization in the Constitutive Act, more than fifteen years later they still do not exist.Footnote 61 Something similar may happen to the Malabo Protocol.Footnote 62 Even if the Malabo Protocol does come into force, will the AU have the political will and resources to adequately fund the expanded ACJHR?Footnote 63

A second concern is whether the AU really intends the Malabo Protocol to be successful. The AU has a tense relationship with the ICC.Footnote 64 The ICC has brought charges against a number of African leaders and this has upset many AU member states.Footnote 65 The indictments of Presidents Al-Bashir of Sudan and Kenyatta of Kenya “galvanized [the] AU’s resolve to establish an African regional criminal court to basically serve as a substitute and operate parallel to the ICC.”Footnote 66 Thus, one way to view the Malabo Protocol is as a mechanism to prevent the ICC from exercising jurisdiction over senior government officials accused of committing crimes in Africa.Footnote 67 And indeed, there are some signs that the drafters of the Malabo Protocol hoped that the addition of criminal jurisdiction to the ACJHR would have this effect.Footnote 68

Creating a regional court whose work would prevent the ICC from exercising jurisdiction over violations of international criminal law committed in Africa would be fine if the AU intended the ACJHR to fairly and impartially prosecute violations committed by African leaders.Footnote 69 But there is also the possibility that the AU intends to use the Malabo Protocol to try and shield African leaders from accountability for human rights violations.Footnote 70 For example, the Malabo Protocol has a worrying provision on immunities.Footnote 71 It prevents the ACJHR from instituting or continuing cases against “any serving AU Head of State” or “other senior state officials.”Footnote 72 This has led to fears that the Protocol is designed, not to end impunity, but to shield African leaders from accountability.Footnote 73

Given that there are reasons to be both hopeful and doubtful about the Malabo Protocol, how should we view it?Footnote 74 The answer may lie in what happens if and when the Protocol enters into force. At that time, the AU will have the difficult task of turning the blueprint in the Malabo Protocol into a functioning international criminal court. It will have to staff the court and give it the resources and support it needs to be successful. This will not be an easy task.Footnote 75

One key indicator of the AU’s intentions toward the new and improved ACJHR will be the resources it devotes to the court. For it to live up to the hopeful vision of a successful regional court that reduces impunity and prevents atrocities, the ACJHR will have to have sufficient resources to carry out both its investigative and its adjudicative functions. On the other hand, if the court is mainly intended to insulate African leaders from accountability for human rights abuses, it will probably not be given the resources to conduct robust investigations and prosecutions. Thus, one way to evaluate the court will be to look at the resources it receives.

Of course, adequate resources are not a guarantee of success, but they are a prerequisite for it.Footnote 76 It will be extremely difficult for the court to be successful if it lacks the resources to carry out its functions. The rest of this chapter will examine what sort of resources one would expect the new ACJHR to need to be successful. Section 5 will look at the scope of the crimes usually investigated by international criminal courts, while Section 6 explores the investigative resources necessary to meaningfully investigate those crimes. Section 7 describes a typical trial at an international criminal court, while Section 8 explores the adjudicative resources necessary for such a trial. Section 9 presents an estimate of the staffing needs and costs of a fully operational ACJHR, while Section 10 compares those estimated costs to the AU’s early projections of the expense of the court. Finally, this chapter’s conclusions are presented in Section 11.

5. International Crimes

Most domestic crimes involve a single perpetrator, a single victim and a single crime site.Footnote 77 And very few domestic crimes involve the most serious offenses like rape and murder.Footnote 78 International crimes, at least the ones that are investigated and tried before international courts, look nothing like the typical domestic crime.

First, the kinds of crimes that are investigated and prosecuted at international tribunals are almost always perpetrated by large hierarchically organized groups working together.Footnote 79 Most often the perpetrators are military or paramilitary units of various sorts. In addition, the majority of international crimes take place as part of an armed conflict, with all the systematic violence that entails.Footnote 80 Even when there is not an armed conflict, there is still usually extensive politically-motivated violence aimed at civilians.Footnote 81 International crimes are also usually much larger in geographic and temporal scope than domestic investigations. The typical ICC investigation involved crimes committed at dozens of different crime sites over time periods that ranged from several months to several years.Footnote 82

International crimes also tend to be extremely serious and involve the widespread commission of rape, torture, murder, inhumane treatment and forcible displacement. For example, at the ICC, the average investigation covered the unlawful deaths of more than a thousand peopleFootnote 83 and the forcible displacement of huge numbers of civilians.Footnote 84 Systematic rape is a common feature of international crimes.Footnote 85 International crimes also tend to be marked by extreme cruelty, often against vulnerable groups like women, children, and the elderly.Footnote 86

As a result of these features, international crimes are vastly more complex than the average domestic crime. They involve a larger number of victims, more serious offenses, and take place over larger areas and longer time periods. They also take place during periods of systematic violence and tend to be carried out by large hierarchically organized groups. As a result, they require substantial resources to investigate.Footnote 87

6. Investigative Resources

Assuming the ACJHR undertakes criminal investigations that are similar in gravity to those undertaken by the ICC,Footnote 88 the ICC’s experience can be a guide to the investigative resources the ACJHR will need. The typical ICC investigation lasts about three years.Footnote 89 The investigative team varies in size over the course of the investigation, with fewer in the first few months and the last few months. But for at least two years, during what the ICC calls the “full investigation” phase, the investigative team is composed of about 35 personnel.Footnote 90

This team includes investigators and analysts, as well as a handful of lawyers, legal assistants and case managers.Footnote 91 It also includes specialists in forensics and digital evidence, and personnel to provide field support and security.Footnote 92 Over the course of three years, this team will screen hundreds of potential witnesses, interview about 170 of them, and collect thousands of pieces of physical and digital evidence.Footnote 93 It will then analyze this information so that the Prosecutor can decide whether to issue charges and, if so, who to charge, and what to charge them with.

It might be tempting to conclude that the ACJHR needs only one investigative team, but then it would only be able to undertake one investigation every three years. This would almost certainly not be enough. For example, the ICC anticipates opening nine new preliminary investigations and one new full investigation every year.Footnote 94 This is on top of the six active investigations it will have in any given year.Footnote 95

The ACJHR will probably need at least two investigative teams. Given that investigative teams only need to be at full strength during the middle of the investigation, it seems plausible that two teams could handle three investigations every three years (assuming that the start of the investigations was staggered). This would give the ACJHR the capacity to undertake approximately one new investigation every year. Thus, in any given year, the ACJHR would have two investigations ongoing, one that was being wrapped up, and have the ability to open one new one, if necessary. This is less investigative capacity than the ICC has, but would probably be sufficient, at least initially.

7. International Trials

Of course, completing an investigation is only the first step in a long process. The most visible part of the process comes next: the trial. International trials are complex undertakings that can take years to complete. For example, at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), the average trial took 176 court days to complete.Footnote 96 During the trial, an average of 120 witnesses testified and more than 2,000 exhibits were entered into evidence.Footnote 97 While some have criticized international trials as too long and too slow,Footnote 98 it appears that this complexity is necessary.Footnote 99

International trials feature a number of factors that increase their complexity relative to the average domestic trial. First of all, they often involve multiple defendants accused of acting together, which increases trial complexity.Footnote 100 International trials also tend to involve a large number of charges against each accused, which also increases complexity.Footnote 101 Finally, another hallmark of international trials is that the accused tend to be senior military or political leaders, which also increases the length of the resulting trial.Footnote 102

This latter point is particularly important as it generates significant additional trial complexity.Footnote 103 This complexity appears to be a result of the difficulty of attributing responsibility for mass atrocities to senior leaders who are both geographically and organizationally distant from the crimes.Footnote 104 Attributing responsibility requires establishing evidence that links the charged persons to the crimes carried out by the direct perpetrators. International criminal lawyers refer to this as the “linking evidence” and it is critical to demonstrating the guilt of the accused. Establishing this link, however, is complex and time-consuming. This complexity is necessary, however, if courts are serious about ending impunity for those most responsible for mass atrocities.Footnote 105

One result of the length and complexity of international trials is that courts need significant resources to carry them out. This is true both in the Office of the Prosecutor and Chambers. If adjudicative resources are insufficient, then trials may be delayed. In a worst case scenario, prosecutions may fail for lack of evidence or accused may have to be released because of the delay in bringing them to trial.

8. Adjudicative Resources

So, what adjudicative resources does the new ACJHR need to conduct successful trials? Again, the experience of the ICC will be used as a guide. The Office of the Prosecutor at the ICC estimates that the average trial takes about five and a half years from the completion of the investigation until the conclusion of the appeal. This includes half a year of pre-trial preparation, three years for the actual trial, and two years for the appeal.Footnote 106 The core trial team is composed of about 15 personnel. The majority of these personnel come from the prosecution division and includes lawyers, legal assistants, and case managers.Footnote 107 They are supported by a small number of investigators who provide support for cross-examination of defense witnesses and investigation of defense theories.Footnote 108 This team has to be in place for about three and a half years to complete a single trial. Assuming that the ACJHR closes one investigation each yearFootnote 109 and that (like the ICC) the majority of new investigations result in immediate trial proceedings,Footnote 110 then there will be approximately one new trial beginning each year. Given that each trial lasts three years, the ACJHR would need at least three trial teams to staff those trials.

The Office of the Prosecutor at the ACJHR will also need a group of lawyers and support staff dedicated to appeals. If one trial finishes each year, and appeals last two years, then on average there will be at least two final appeals going on at any time. To handle two final appeals plus a small number of interlocutory appeals arising out of ongoing cases, the ICC requires seven personnel.Footnote 111 It seems likely that the ACJHR would need an appeals section of about the same size.

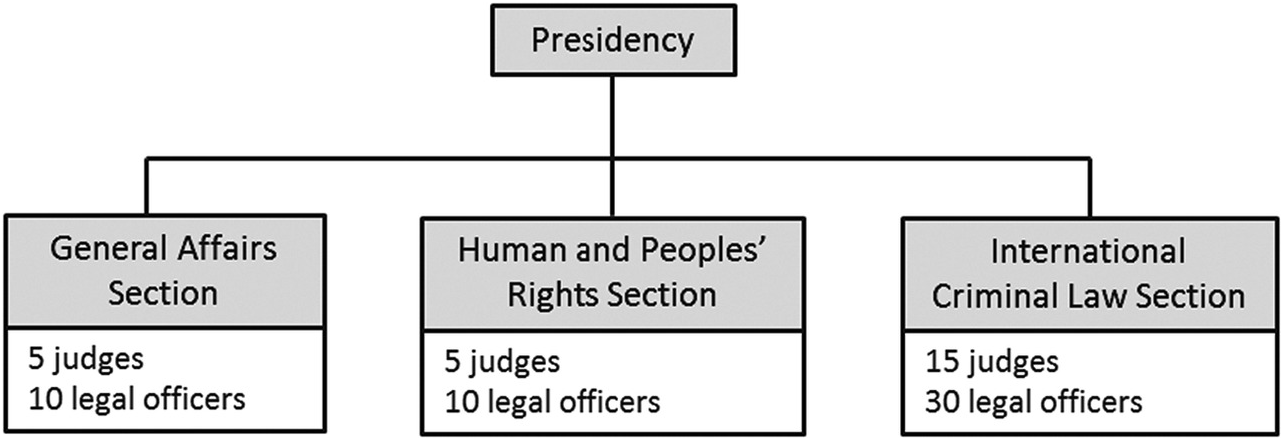

In addition to the required personnel within the Office of the Prosecutor, the ACJHR will also require the necessary staff within Chambers. The new International Criminal Law Section will have within it three Chambers: a Pre-Trial Chamber, a Trial Chamber and an Appellate Chamber.Footnote 112 But, it appears the International Criminal Law Section as a whole will have only six judges.Footnote 113 This is almost certainly inadequate.Footnote 114

The Pre-Trial Chamber requires one judge, the Trial Chamber requires three judges, and the Appellate Chamber requires five judges. Even if only one trial was going on at a time six judges would be inadequate because it would be impossible to staff all three chambers unless judges sat on multiple chambers for the same case. This would be problematic as it would require a judge who sat at an earlier stage of a case (say as a trial judge) to then adjudicate a later stage (say as an appellate judge). Having the same judge sit at different stages of the same case undermines the defendants’ fair trial rights.Footnote 115 So, for this reason alone, the ACJHR would need at least nine judges so that no judge would have to sit at different stages of the same case.

But even nine judges would probably not be enough. Assuming that one new trial begins each year and that each trial lasts about three years,Footnote 116 the ACJHR will need to constitute three Trial Chambers. This would require nine judges on its own. Even if the existing Appellate Chamber could handle all of the appeals and a single Pre-Trial Chamber judge could handle all pre-trial matters that would still mean that the ACJHR would need fifteen judges just in the International Criminal Law Section.Footnote 117

In addition to 15 judges, the International Criminal Law Section would also need the necessary legal personnel to support those judges. The ICC estimates that it needs five full-time legal personnel assigned to Chambers per trial.Footnote 118 If the ACJHR has similar needs, it would require fifteen legal personnel to staff the three Trial Chambers. Again, following the ICC’s model, the Appellate Chamber would need a staff of ten legal officersFootnote 119 while the Pre-Trial Chamber would require only two personnel (assuming that only a single judge is assigned to it).Footnote 120

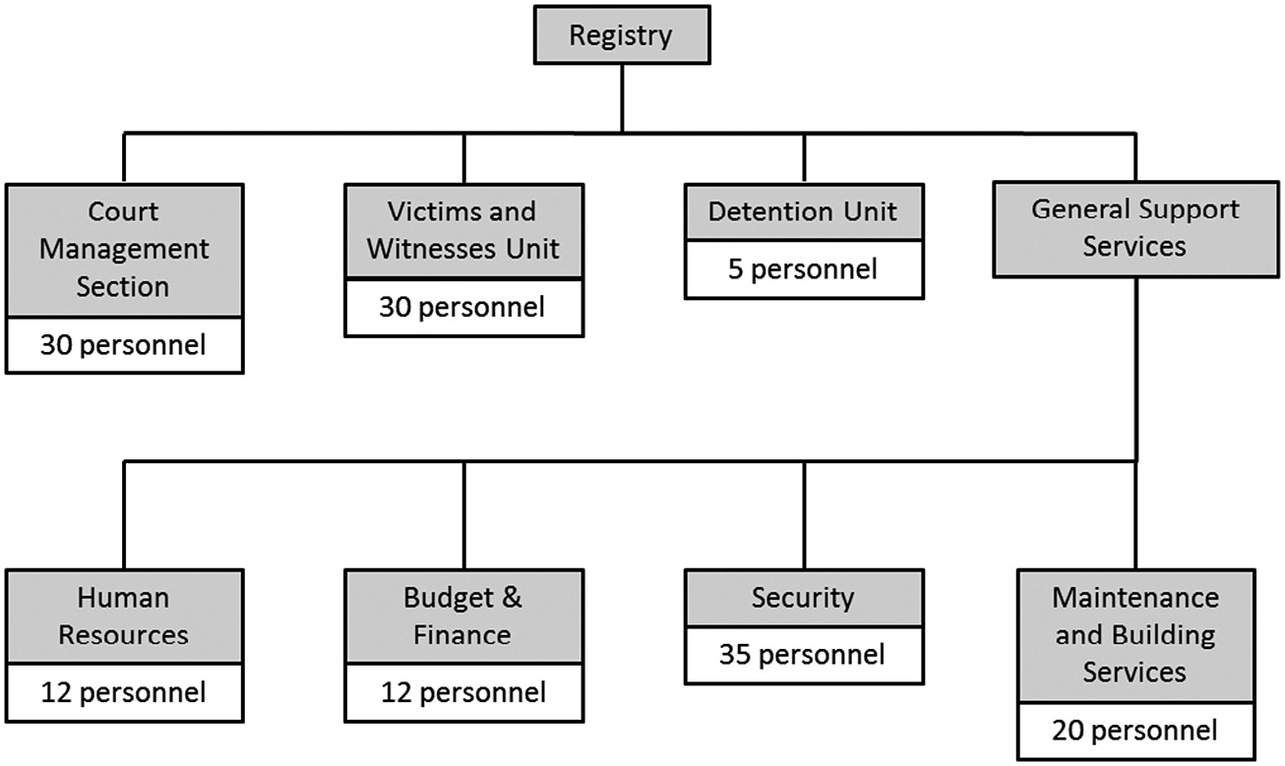

Finally, the Chambers will need something like the ICC’s Court Management Section, which maintains the official records of the proceedings, distributes orders and decisions and maintains the Court’s calendar, including the scheduling of all hearings.Footnote 121 The ICC employs 33 people in the Court Management SectionFootnote 122 to support the work of 18 judges.Footnote 123 This chapter argues that the ACJHR will eventually need fifteen judges in the International Criminal Law Section. This is on top of the judges in the Human and Peoples’ Rights Section and the General Affairs Section. Accordingly, it seems likely that the ACJHR will need a similarly sized court management section to support the work of those judges.

9. Staffing a New International Tribunal

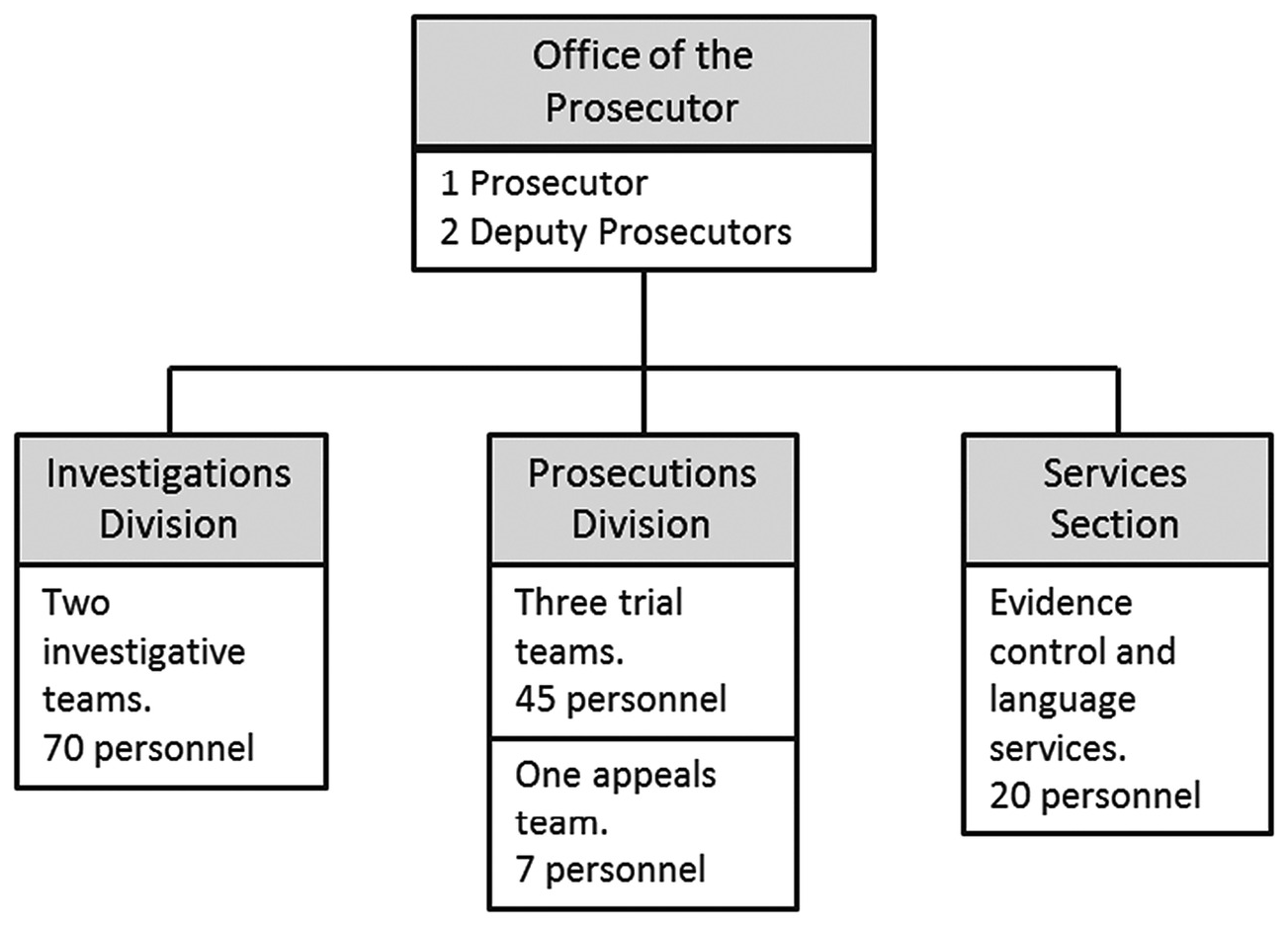

As the previous sections have demonstrated, building a functioning international criminal court is far from simple. First, it will need to have the staff to carry out its investigative functions. Within the new ACJHR’s Office of the Prosecutor this will probably mean two investigative teams of about 35 personnel each. This will include a mix of investigators, analysts, forensics experts, and legal personnel.

The court will also have to have sufficient personnel to carry out its adjudicative functions. This will almost certainly mean in increase in the number of judges assigned to the International Criminal Law Section to 15 or so judges. They would need to be supported by at least twice that number of legal officers. In addition the prosecutions division within the Office of the Prosecutor will need three trial teams of about 15 personnel each plus an appeals team of about 7 or 8 personnel. Finally, there must be some organ like the ICC’s Court Management Section to create the official record and handle all of the scheduling issues.

And these are just the core personnel tasked with carrying out the investigations and trials. In practice, international courts need additional personnel to support the core tasks. For example, the OTP at the ICC contains a Services Section that contains the Information and Evidence Unit and the Language Services Unit.Footnote 124 These are important units that help control and preserve evidence and provide the interpretation and translation services that are almost certainly going to be needed by the investigative and prosecutorial teams.Footnote 125 The Services Section at the ICC is about one-third the size of the Investigation Division and half the size of the Prosecutions Division.Footnote 126

In addition, the Amended Statute of the new ACJHR specifically says that the Registrar must create a Victims and Witnesses Unit to provide “protective measure and security arrangements, counselling and other appropriate assistance” for victims and witnesses.Footnote 127 It also requires the Registrar to set up a Detention Management Unit to “manage the conditions of detention of suspects and accused persons.”Footnote 128 Finally, the Amended Statute provides for an independent Defence Office that will be responsible for “protecting the rights of the defense, providing support and assistance to defence counsel … .”Footnote 129 These units will have to be staffed. At the ICC, the Office of Public Counsel for the Defence has similar functions to the ACJHR’s Defence Office and has five personnel.Footnote 130 Similarly, the ICC’s Detention Section has five staff members.Footnote 131 The ICC office most similar to the ACJHR’s Victims and Witnesses Unit is the Victims and Witnesses Section.Footnote 132 The ICC employs 63 people in this task.Footnote 133

It is also highly likely that the new ACJHR will need other more general support services. At the ICC, these are located within the Registry. It is likely the same would be true at the ACJHR.Footnote 134 At the ICC, the Registry includes functions like a Human Resources Section,Footnote 135 a Budget Section,Footnote 136 a Finance Section,Footnote 137 a Security and Safety SectionFootnote 138 and a General Services Section.Footnote 139 While the ACJHR would not necessarily need to be structured in the exact same way, it will need the same services. It will need to have staff that provide security, clean and maintain the buildings, and pay the bills. Even if we assume that the new ACJHR would only need about half as many personnel in these functions as the ICC, it would still need something like 80 people in these support positions.

The following organizational charts make an educated guess about what resources the new and expanded ACJHR will need to successfully investigate and prosecute international crimes once it is fully operational.Footnote 140 These are not meant to be exact predictions. For example, it may be possible to make the investigations teams slightly smaller. Or it might be possible to have fewer legal officers in Chambers and fewer personnel in the Victims and Witnesses Unit. Perhaps the court can get by with fewer personnel in support roles. Of course, cutting corners on resources can be counter-productive, as the ICC has discovered.Footnote 141

These figures suggest a court with about 145 personnel in the Office of the Prosecutor. The majority of the personnel in the OTP would be working on investigations. The Presidency would be composed of 25 judges and 50 legal officers. Their primary function would be to hear the trials and appeals. Finally, the Registry would require about 145 personnel to provide the needed support services to the court. In addition, the Defence Office will have five or six staff members. This assumes that there will be no permanent interpretation/translation office in the Registry and that interpretation and translation services will be provided under service contracts rather than through the hiring of full-time personnel.Footnote 142

Overall, the expanded ACJHR would have a staff of about 370 personnel. This would make it roughly one-third the size of the ICC, which currently has about 1,100 personnel.Footnote 143 This implies an expected cost of about 48 million euros per year for the new ACJHR.Footnote 144 This is many times the current budget of the AU’s judicial bodies.Footnote 145

10. Early AU Estimates of the ACJHR’s Needs

The AU’s member states have been concerned about the consequences of expanding the ACJHR’s jurisdiction.Footnote 146 So, for example, at a meeting of Ministers of Justice in 2012, various delegations asked about the “financial and budgetary implications” of expanding the jurisdiction of the court.Footnote 147 This concern has resulted in a small number of documents that discuss the expected resource requirements of the ACJHR. Unfortunately, these documents are from 2012, so it is unclear whether they still represent the position of the AU.Footnote 148 But given that they are the only financial projections from the AU that are available, this chapter will discuss them.

The reports discuss whether there are existing courts that could be used as examples of the resources the ACJHR will need. For example, the report of the meeting of Ministers of Justice notes that the Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL) cost $16 million per year in 2011 and employed slightly more than 100 personnel.Footnote 149 It also notes that the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) cost $130 million per year in 2010 and employed 800 staff.Footnote 150 But it takes no position on whether either of them is a good model for the ACJHR. Another report suggests that the trial of the former President of Chad, Hissène Habré, in Senegal, which reportedly cost about 7 million euros over three years, represents the “most appropriate” comparison.Footnote 151

All of these comparisons are flawed. The ACJHR probably does not need to be as big as the ICTR at its height.Footnote 152 Nor is the trial of a single individual – Hissène Habré – likely to represent the experience of the ACJHR, which may need to open one new investigation and begin one new trial every year.Footnote 153 The SCSL in 2011 is not a particularly good comparison either. By 2011, the SCSL had almost completed its mandate. The only significant legal activity that year was the trial of Charles Taylor.Footnote 154 There were no new investigationsFootnote 155 and minimal activity by the Appeals Chamber.Footnote 156 The expanded ACJHR will have to undertake complex investigations and be able to deal with more than one trial and appeal at a time. The most obvious contemporaneous comparator is the ICC. The omission of references to the ICC in the AU’s documents may stem from its difficult relationship with the ICC.Footnote 157

If the SCSL is to be used as a comparator, however, then the SCSL in 2007 is a better choice. In that year, the SCSL was engaged in the CDF trial, the RUF trial, and the AFRC trial.Footnote 158 There was also substantial activity in the Appeals Chamber.Footnote 159 The Office of the Prosecutor, in addition to participating in the ongoing trials, was also engaged in the investigation of the Charles Taylor case.Footnote 160 This is more like what a fully operational ACJHR can expect. But it is worth noting that the SCSL cost $36 million in 2007 and employed more than 400 people.Footnote 161 This is similar to the projections in this chapter.Footnote 162

Besides looking for appropriate comparators, one of the AU’s reports also contains a proposed staffing table for the expanded ACJHR.Footnote 163 A summary of that information is contained below in Table 38.1.Footnote 164 One noticeable (and presumably deliberate) omission is any entry for the judges and their salaries. But beyond that, there are some staffing assumptions that are simply unrealistic.

| Office | Components | No. of Staff | Estimated Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Registrar | |||

| Office of the Registrar | 18 | $420,791 | |

| Information and Communication | 3 | $89,403 | |

| Languages Unit | 41 | $1,127,451 | |

| Sub-Total | 62 | $1,637,645 | |

| Legal Division | |||

| Office of the Division | 1 | $45,551 | |

| Legal Unit | 16 | $511,568 | |

| Library, Archives, and Documentation | 14 | $266,692 | |

| Sub-Total | 31 | $823,811 | |

| Finance, Admin. and HR | |||

| Office of the Division | 2 | $91,102 | |

| Finance, Budgeting, and Accounting | 6 | $131,838 | |

| HR and Administration | 8 | $169,668 | |

| Procurement, Travel, and Transport | 11 | $144,809 | |

| IT Services | 10 | $254,860 | |

| Security and Safety | 30 | $326,022 | |

| Protocol Unit | 9 | $168,546 | |

| Sub-Total | 76 | $1,286,845 | |

| Office of the Prosecutor | |||

| Office of the Prosecutor | 6 | $189,696 | |

| Prosecution Division | 5 | $161,511 | |

| Investigation Division | 1 | $38,489 | |

| Sub-Total | 12 | $389,696 | |

| Total | 181 | $4,137,997 |

For instance, the Office of the Prosecutor does not have sufficient capacity. Apart from the Prosecutor and two Deputy Prosecutors, it has only four legal officers in the Prosecution Division. This might be enough to conduct a single, relatively simple trial, but even then it lacks sufficient support in the form of legal assistants and case managers.Footnote 165 It would not permit the ACJHR to undertake complex trials or try more than one case at a time. There is also no provision for an appellate team. This may not be needed at start-up, but at some point the Office of the Prosecutor will need staff devoted to appeals.Footnote 166

A bigger problem is the lack of investigative capacity. The staffing table only provides for a single individual in the Investigation Division. This is inadequate, even at start-up. International criminal investigations are enormously complex and require substantial resources.Footnote 167 The typical ICC investigation team is composed of 35 personnel, including investigators, analysts, lawyers, legal assistants, case managers, and specialists in forensics and digital evidence.Footnote 168 Without a robust investigative capacity, the ACJHR cannot be successful.

There are also problems in other organs of the court. For instance, there appears to be only a single person assigned to the Defence Office and a single person assigned to the Victims and Witnesses Unit. Both of these units will almost certainly need additional staff. The ICC has five personnel in the Office of Public Counsel for the Defence and 63 people in the Victims and Witnesses Section.Footnote 169 The ACJHR may not need this many personnel, but two people is almost certainly insufficient.

In addition to omitting the judges and their salaries, the proposed staffing table does not provide for any legal officers in Chambers. The ICC averages almost two legal officers per judge, which implies a need for approximately 30 legal officers in Chambers.Footnote 170 A final issue is that the proposed staffing table does not appear to provide for a large enough court management section. It indicates that there will be 9 personnel assigned as either court recorders, assistant court recorders, or court clerks. This is probably not enough.Footnote 171

While the staffing proposal is presented as the ACJHR’s staff requirements at the “outset,”Footnote 172 it would not be sufficient even at start-up. As soon as the ACJHR received its first case, which would likely occur during the court’s first year of operation, the problems would begin. Without any investigative capacity it would not be able to conduct an investigation. The court would likely be overwhelmed with victims and witnesses that it is ill-prepared to accommodate. It also seems to lack the legal officers and court management personnel necessary to support the judges in their work.

It may be a mistake to read too much into the AU’s early projections. Nevertheless, if the expanded ACJHR’s staffing ends up looking like the 2012 proposal, it is unlikely that it will be successful. Such a court might be able to try one small case every two or three years, but it would not be able to live up to the AU’s expectations. The Malabo Protocol states that the expanded ACJHR is intended to prevent serious violation of human and peoples’ rights and ensure accountability for those violations.Footnote 173 For it to achieve these goals, the ACJHR will need robust investigative, prosecutorial, and adjudicative capacity. Furthermore, If it does not have sufficient resources to investigate and prosecute those situations which would otherwise fall under the purview of the ICC, it will not be able to achieve the AU’s goal of depriving the ICC of jurisdiction over situations in Africa either.Footnote 174

11. Conclusion

The main takeaway from this chapter is that operating an international criminal court is not cheap. Investigating and prosecuting mass atrocities takes significant resources. Thus one way to evaluate the expanded ACJHR will be to look at the resources the AU assigns to the court. If the AU does not assign it sufficient resources to carry out complex in-depth investigations and difficult multi-year trials and appeals, then it is extremely unlikely that the court will be successful in shrinking the impunity gap or preventing atrocities. If, on the other hand, the AU does provide the ACJHR with the resources and political support it needs to carry out its mandate, then there will be reason to be hopeful about its eventual success.Footnote 175