There’s no Michelangelo coming from Pittsburgh

If art is the tip of the iceberg

I’m the part sinking below.

Smalltown, Lou Reed & John CaleIntroduction

The view from the periphery

Until 2017, Poland Fashion Week was held twice yearly in Łódź. This city in central Poland was a center of textile production until the collapse of the communist economy. Łódź is full of empty brownstone factory buildings that match the bare-brick post-industrial aesthetic of the 2010s. In one of those factories, we visited the 2012 Fashion Week. In the tram from the station, we already spotted the fashion people coming in from Warsaw: thin, stylish, dressed in black. A ticket cost 20 zlotys (about 5 euros) and could be bought at the entrance. Tickets provided access to all catwalk shows, the showroom and a photo exhibition.

The main hall with the catwalk was half empty during our visit. The front row was reserved for VIPs. On the seats were papers with names of Polish fashion journalists, designers and magazine editors. Although some shows attracted more spectators than others, most VIPs never showed up during our visit. The models made more of an impression than the clothes they showed. Most models were Polish (as the Fashion Week Director told us later), and had a typical high-fashion look: tall, fierce, pale, elegant, unsmiling and “edgy”. Their outfits, however, seemed like student work: experimental, rather unwearable ideas-in-textile.

The visitors were a mix of fashion professionals—buyers, sellers, designers, bookers, stylists, journalists, models—and mostly young fashion lovers. Everybody present seemed to be Polish: we once heard French spoken; we did not hear people speaking English. While the catwalk show was avant-garde and non-commercial, most brands and goods in the showroom were mainstream: streetwear and large international brands. The showroom featured a hodgepodge of small labels and one-person businesses in clothing and accessories, commercial clothing brands, and prominent, noisy stands from the sponsors, including global fashion brands (Maybelline, Schwarzkopf, Orsay), Polish newspapers and fashion magazines, and a Californian wine producer called Carlo Rossi. Food stands sold Carlo Rossi wine, and sushi with small pieces of paper specifying the calories in each item.

The overall experience was starkly different from the fashion weeks of Milan or Paris (which we also visited). There, the entire fashion field “materializes” in a single, high-energy event, with everybody trying to catch trends, create buzz and close deals [Entwistle and Rocamora Reference Entwistle and Rocamora2006]. People wait in line for hours, hoping to attend a show. Tickets are invitation-only and hard to come by. In Łódź, we walked up to the box office and paid a small fee. In spite of many things to see and do, the atmosphere was listless. The lack of urgency was underlined by the disconnect between the art-school atmosphere of the shows, and the commercialism of the showroom exhibits.

The Poland Fashion Week website claimed that the event has “earned the recognition of international fashion circles” and “is part of the official world calendar of Fashion weeks.”Footnote 1 It showed clips of full catwalk shows cheering radiant models and international celebrities like Paris Hilton – nothing like our own experience of low attendance and low energy. This website, however, is now defunct. In 2017, Poland Fashion Week was replaced by the smaller, more modestly named “Łódź Young Fashion”.Footnote 2 The website’s insistence on outside recognition already signaled peripheralness. In London, Paris, Milan or New York nobody feels compelled to emphasize relations to “international fashion circles”. The center never needs to justify itself. In Łódź, we experienced what it means to be the periphery.

All cultural fields are embedded in transnational center-periphery systems [Buchholz Reference Buchholz2016; Heilbron Reference Heilbron1999; LaVie and Varriale Reference Lavie and Varriale2019; Velthuis and Brandellero Reference Velthuis and Brandellero2018]. Most studies of cultural production focus on centers, where creative clusters emerge, tastemakers converge, pundits consecrate new trends, and the hopeful gather to “make it” [for fashion, see Bovone Reference Bovone2005; Currid Reference Currid2008; Godart Reference Godart2018; Hoppe Reference Hoppe, Cattani, Ferriani, Godart and Sgourev2020; Mears Reference Mears2011; Williams and Currid-Halkett Reference Williams and Currid-Halkett2011]. These studies show how the making of cultural value depends on a clustering of tastemakers in tight-knit “art worlds”. In Łódź, we witnessed how the reverse happened: limited networking or clustering, little buzz, few pundits, no tastemakers. Consequently, not much value was created, either in material or symbolic terms.

This article shifts our focus to the periphery by analyzing the production of value in semi-peripheral and peripheral fashion fields. We argue that more peripheral settings have distinct dynamics and characteristics that researchers have failed to note because they focused on global “hubs”. Drawing on fieldwork in the Polish and Dutch fashion fields, we identify three key features of (semi-)peripheral fields. First, the dependence on foreign centers for goods, standards and consecration produces specific peripheral structures. Second, peripheral producers adopt specific peripheral strategies for creating value. While peripheral strategies may effectively accrue material value, they are less effective in creating symbolic value, and rarely lead to consecration: attribution of the highest symbolic value. Third, the peripheral experience shapes people’s subjectivities, creating peripheral selves. In cultural fields like fashion, where work is central to self-worth and self-experience, these peripheral selves are often defined by a mismatch between taste and place, self and setting, high fashion affiliations and mainstream reality.

A view from the periphery allows us, first, to move forward our understanding of globalization. Our analysis shows that (semi-)peripheral fields are more than a reversal or faint reflection of centers. Theorizing the periphery sheds new light on global interdependencies, transnational fields and, therefore, also on the working of (transnational) cultural production. Second, the view from the periphery leads us to conceptualize “peripheralness” as a distinct dimension of social inequality. Peripheralness is a dominated social position that defines and constrains the strategies and options available to peripheral actors, producing a distinct peripheral sense of self. Like all forms of inequality, peripheralness is not a binary divide, but a continuum from “most central” to “most peripheral”. Finally, the view from the periphery allows us to uncover blind spots of dominant field-theoretical approaches to cultural production, notably their focus on cultural centers and their lack of attention to subjectivity.

Both globalization theory and studies of cultural production led us to expect that peripheral life would be grim: marked by dependency, frustrated aspirations and a sense of failure. Peripheral actors, like other people in dominated positions, see the world and themselves simultaneously through their own eyes, and through the eyes of dominant others. Scholars of inequality since Du Bois [(Reference Du Bois1903) 2008] have pointed out that the “double vision” resulting from a dominated position fosters alienation, frustration and embarrassment. To our surprise, however, many informants experienced their lives in more peripheral fields as preferable to life in the center. In less prestigious fashion fields, this double vision can make people’s working lives bearable, pleasurable, and even profitable. Many peripheral strategies capitalize on this double vision, for instance by brokering between centers and peripheries. Moreover, peripheral selves may serve as a safeguard against the precarity and exploitation typical of high-status, winner-take-all centers [Duffy Reference Duffy2017; Baker and Hesmondhalgh Reference Baker and Hesmondhalgh2013; Mears Reference Mears2015; Neff, Wissinger and Zukin Reference Neff, Wissinger and Zukin2005]. Dominated, dependent positions can therefore be perceived as preferable to more “central” positions which, in the eyes of sociologists and most actors in the field, are “objectively” higher up the ladder. Peripheral fashion people complain profusely about events like Poland Fashion Week, or its Dutch equivalent, Amsterdam Fashion Week. But, in the end, most prefer being a big (or medium-sized) fish in a small pond, to being a small fish in a big pond – even when this small pond is at times as listless, embarrassing and ultimately doomed as Poland Fashion Week.

The Production of Value in Cultural Peripheries

Value and consecration in fashion fields

Cultural fields revolve around the production of symbolic and material value. In fashion, the cultural field that produces and disseminates material goods (clothing, make-up, photographs), symbolic goods (brands, magazines), and aesthetic styles related to bodily adornment [Entwistle Reference Entwistle2009; Godart Reference Godart2014], this process of value-production is particularly fickle. Outfits or hairstyles considered beautiful or “hot” one year often lose their luster by the next. Value in fashion therefore has little to do with use value or material cost: the price of a designer handbag is easily hundreds of times its cost of production. How “beautiful” a fashion model is, how “good” a design or photograph, ultimately depends on collective judgments of actors in the field [Aspers Reference Aspers2012; Godart and Mears Reference Godart and Mears2009].

Following a field-theoretical approach to cultural production [Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1993, (1992) Reference Bourdieu1996; Fligstein and McAdam Reference Fligstein and McAdam2012], we assume that cultural value is created through relational, mainly status-related dynamics in semi-autonomous fields. In such fields, value results from the “production of belief” [Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1993] in the legitimacy of the cultural standards and social hierarchies of the field [Allen and Lincoln Reference Allen and Lincoln2004]. The production of belief happens most explicitly in moments of consecration that “venerate a select few cultural creators or works that are worthy of particular admiration in contrast to the multitude that are not” [Schmutz and Faupel Reference Schmutz and Faupel2010: 687]. Consecration is typically done by high status actors. For instance, the famous “September issue” of Vogue identifies the season’s new “looks”, which are adopted by fashion professionals around the world—eventually ending up, in diluted form, in our wardrobes [Moeran Reference Moeran2006]. Institutions and individuals such as top models, designers or celebrities are important tastemakers that endorse and embody good fashion.

Actors pursue field-specific strategies for producing value and acquiring status. These strategies are shaped and constrained by the logic of this field and by people’s field position [Fligstein and McAdam Reference Fligstein and McAdam2012]. In her ethnography of fashion modeling, Mears [2011] shows that some strategies––like participating in modeling contests––are accessible to all aspiring models, while other strategies are reserved for established models with sufficient cultural or social capital. As people “move up the ladder”, they have more to choose from and can act more strategically. A central strategic choice for fashion professionals is whether to aim for “high fashion” or “commercial” fashion. High fashion is the autonomous pole of fashion production, with avant-garde styles and a constant quest for novelty. The commercial subfield has a more conventional, accessible aesthetic. Here, material value is more easily accrued—for successful actors the money is good—but the symbolic value is limited. In the high fashion subfield, the reverse is true: prestige is high, but this symbolic capital is not easily converted into economic capital. These subfields are generally considered mutually exclusive: everyone working in fashion chooses, or is assigned, a field, and adapts their strategies accordingly. Thus, strategies towards success are shaped and constrained by the logic of the field, field position and subfield.

The field-theoretical conceptualization of actors pursuing field-specific strategies towards valuation and consecration has some blind spots. First, because of the focus on power dynamics, studies of cultural production focus disproportionally on central places like New York, London or (for fashion) Milan or Paris [cf. Hoppe Reference Hoppe, Cattani, Ferriani, Godart and Sgourev2020]. However, such high-prestige fields may not be representative for cultural production. Cultural fields like fashion are “winner-take-all” markets, with high benefits for few people [Abbing Reference Abbing2002]. Especially prestigious centers attract a “reserve army” of hopefuls, willing to work for little compensation [Duffy Reference Duffy2017; Mears Reference Mears2015]. As the work ethos of these precarious workers hinges on the belief in the goals of the field, their sense of self becomes connected with professional aspirations. A focus on central fields, where the stakes are high, may therefore paint a rather extreme picture of success, struggle and professional dedication.

Second, field theoretical approaches to cultural production tend to assume that strategies are aspirational. Especially in Bourdieu’s original conceptualization, cultural production is a constant quest for consecration and domination. However, the view from the periphery challenges this assumption of aspiration: the notion that cultural work is about the dream of “making it big”. Even though peripheral workers know that the highest forms of consecration are unlikely to be achieved in their local field, not everybody in the periphery is plotting to leave to the center to “make it there”.

This article tackles these limitations of field theoretical approaches by asking what “making it” means for peripheral workers. We investigate what sorts of value and success peripheral cultural producers pursue, and what strategies they employ to achieve them. This approach resonates with previous critiques of field theory that have challenged the assumption of aspiration and consecration as a driving force in cultural fields, pointing to other motives like uncertainty reduction [Bielby and Bielby Reference Bielby and Bielby1994], moral worth and dignity [Lamont Reference Lamont2000], avoiding failure [Baker and Hesmondhalgh Reference Baker and Hesmondhalgh2013], good work [Ezzy Reference Ezzy1997], creative freedom [Yavo-Ayalon Reference Yavo-Ayalom2019], or even love [Friedland Reference Friedland2013].

From cultural centers to cultural peripheries

In today’s global culture, transnational dynamics are central to cultural valuation and consecration. Studies of cultural value production have focused on global cultural capitals like Paris, London or New York, where global standards are set for fashion, as for art, literature, movies and academic work. However, these centers cannot exist without a periphery. In the study of globalization and center-periphery dynamics, the periphery has remained “curiously undertheorized” [cf. Buchholz Reference Buchholz2018: 19]

Center-periphery models highlight the interconnection of power imbalances in the capitalist world system: peripheries are dominated socially, spatially, economically, and culturally by a powerful “core” [Wallerstein Reference Wallerstein1974] or “center” [Hannerz Reference Hannerz1989; Shills Reference Shils and Ignotus1961]. Three distinct approaches to cultural center-periphery relations have analyzed the macro-, meso-, and micro-mechanisms that produce and sustain cultural domination and dependence.

The macro-approach has focused on transnational (cultural) fields [Buchholz Reference Buchholz2018; Kuipers Reference Kuipers2011]. In these fields, an asymmetrical flow of products, ideas and standards from dominant centers to peripheries strengthens central cities and weakens local production. Local fields increasingly mirror the standards and structure of central fields, although cultural policies and local cultural (sub)fields may counter such homogenizing tendencies [Buchholz Reference Buchholz2016; Sapiro Reference Sapiro2010]. This dependence is uneven but mutual: peripheral actors look to centers for styles and standards; central actors depend on peripheries for markets and raw materials.

In the meso-approach, the emergence of economic/geographical centers is interpreted as the clustering of industries [Currid Reference Currid2008; Godart Reference Godart2014; Pratt Reference Pratt2008; Scott Reference Scott2000; for fashion Merlo and Polese Reference Merlo and Polese2006]. Production attracts related businesses, which increases specialization and fosters synergy, leading to growing investments and a mushrooming of related businesses. These clustering processes are layered and polycentric, with “supercentral” hubs and smaller, often more specialized clusters in the semi-periphery. This meso-approach theorizes center-peripheries as a continuum from most central to most peripheral. In peripheral regions, lack of human capital and investments produces a self-reinforcing cycle of economic stagnation, emigration and exploitation [Kühn Reference Kühn2015]. Hoppe [Reference Hoppe, Cattani, Ferriani, Godart and Sgourev2020], whose analysis of the fashion week of a semi-peripheral US city resonates strongly with our findings, argues that semi-peripheries are caught up in another cycle: lack of investments and human capital lead to “imperfect imitation” of centers, producing failed legitimacy. “Semi-peripheral” places are more integrated into transnational networks than peripheral places; while also dependent and often exploited, they may have distinct competitive advantages, like availability of state support or good infrastructure [Mordue and Sweeney Reference Mordue and Sweeney2020], and potential for innovation because of their relative isolation from central networks fosters creativity and independent thinking [Brandellero and Kloosterman Reference Brandellero and Kloosterman2010].

The micro-approach, finally, shows how social networks produce center-periphery relations. This approach is not necessarily about geography: all networks have centers and peripheries. The dense cores of networks maximize opportunities for connecting with like-minded or well-connected people. This is especially important in cultural fields because of the social nature of valuation processes [Crossley Reference Crossley2015]. The micro-focus highlights strategic possibilities resulting from network positions. Peripheral professionals benefit from a move to the center, while core actors benefit from collaborating with innovative peripheral actors [Cattani and Ferriani Reference Cattani and Ferriani2008; Dahlander and Frederiksen Reference Dahlander and Frederiksen2012; Godart et al. Reference Godart, Maddux, Shipilov and Galinski2015]. However, “the challenge for peripheral players is that the same social position that enables them to depart from prevailing norms may also restrict their access to resources and social contacts that would facilitate the completion and legitimation of their work.” [Cattani, Ferriani and Allison Reference Cattani, Ferriani and Allison2014: 216] The network approach thus highlights the importance of brokerage by “cultural intermediaries” [Franssen and Kuipers Reference Franssen and Kuipers2013; Maguire and Matthews Reference Maguire and Matthews2012], who connect dense cores with innovative but isolated (semi-)peripheries.

These approaches identify different mechanisms that explain why and how production of value happens mainly in centers. All three paint a rather grim picture of peripheries: dependent, dominated, stagnant, exploited though with a (dormant) potential for innovation. However, peripheries are rarely singled out for theoretization or empirical scrutiny. Consequently, existing theories and studies tell us little about the structural characteristics of peripheral production, the particular forms of disadvantage confronting peripheral actors, or the strategies available to them. As Kühn [Reference Kühn2015: 256] observes: “The emergence of peripheries is […] not only the structural opposite of processes of centralization, but periphery and center mutually influence each another.” To grasp the working of (cultural) production, we must understand centers and peripheries (note the plural) as part of transnational relations with mutual, though imbalanced, dependencies. To do that, we must work towards a theory of the periphery: What are the structural characteristics of peripheral worlds? What strategies do peripheral actors pursue in creating what sort of value? How does this affect their sense of self?

Method, Data and Research Approach

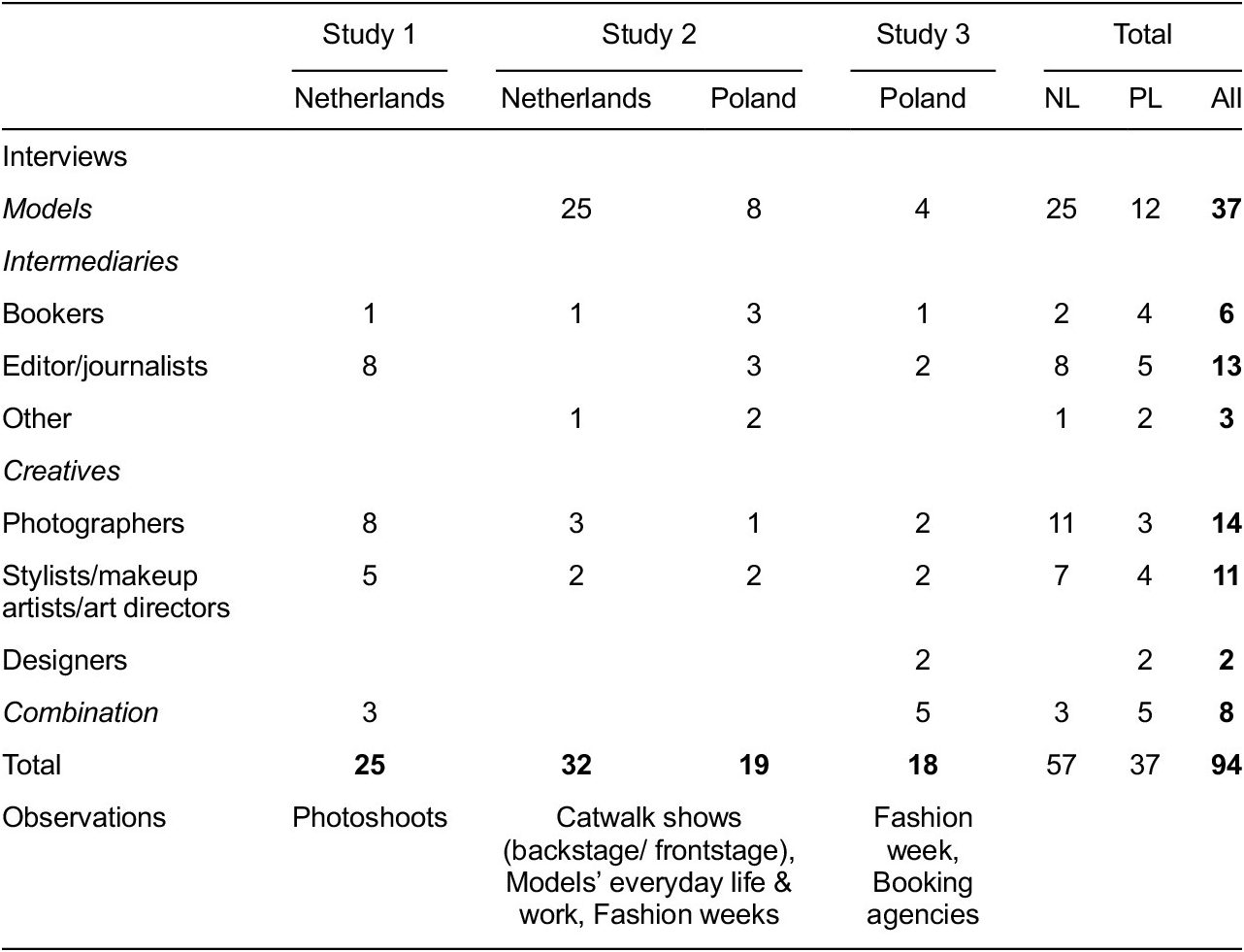

This article is based on 94 interviews and ethnographic observation in the fashion fields of the Netherlands (mainly Amsterdam) and Poland (mainly Warsaw). It combines findings from three studies conducted between 2010 and 2017 as part of a larger project studying the shaping of aesthetic standards and cultural value in European fashion, especially fashion modelling, photography and journalism.

Table 1 presents an overview of our data. We focus on three categories of fashion professionals: fashion models, creatives (designers, stylists) and cultural intermediaries (bookers and journalists) who function as cultural brokers and gatekeepers. We analytically separate models because, as will become clear in the analysis, their distinct “forms of capital”––bodily capital [Mears Reference Mears2015] versus creative skills––enable distinct strategies and opportunities. The methodological appendix provides a further description of methods, sampling, data and analysis for each separate study. The first dataset, collected for a study of aesthetic standards in fashion photography in Italy, the UK and the Netherlands [Laan and Kuipers Reference Laan (van der) and Kuipers2016a; Reference Laan (van der)b], consists of observations of photoshoots and interviews with Dutch fashion creatives and journalists. The peripheral character of Dutch fashion was a salient theme: informants were oriented towards international standards and complained about the lack of glamour, status and quality of the dependent Dutch field. Study 2 investigated fashion modelling in France, the Netherlands and Poland [Holla Reference Holla2016; Reference Holla2018; Reference Holla2020]. While the Paris field proved quite distinct, the Dutch and Polish findings showed striking similarities in field structure, working conditions, aesthetic standards, and fashion professionals’ self-experience. The third study analyzed the production of symbolic and material value among creatives and intermediaries in fashion capital Milan and peripheral Warsaw. The Polish findings were remarkably similar to Study 1 regarding field structure, production of aesthetic standards, and workers’ self-perception.

Table 1 Overview of data

None of these studies set out to explicitly analyse “peripheralness”. However, the project was designed around a contrast of central and peripheral sites. Each study compared central and peripheral countries. Center-periphery relations therefore featured prominently in the theoretical framework and the research questions of each study. In this article, we “upgrade” peripheralness from a central axis of comparison across cases, to a core concept singled out for further theorization. This “upgrade” emerged abductively [Tavory and Timmermans Reference Tavory and Timmermans2014] from our empirical research. In all three studies, we were struck by similarities between the more peripheral sites. A focus on what Yavo-Ayalon [2019] aptly called “periphererality” seemed a useful way to make sense of the theoretical loose ends in our data. At the conclusion of the separate projects, we therefore pooled our data for a focused analysis of peripheries.

All interviews and observation materials were recoded for this article, using a coding scheme developed in various rounds. The coding scheme focused on three major themes: 1. Peripheral worlds: people’s observations on the structural features of local fashion, including types of work, organizations, products, market structures, resources and relations within and beyond the field; 2. Peripheral strategies: professional practices and strategies for creating material and symbolic value for various types of work and workers; 3. Peripheral selves: personal experiences and reflections on work in (semi-)peripheral fashion in relation to professional positions and activities. We paid specific attention to informants’ professional position (creative, model or intermediary) and to comparative observations, such as comparisons between the local fashion field and other fields, mentions of fashion capitals, or personal experiences of working abroad. Such comparative observations were common in our conversations.

Peripheral worlds

The transnational fashion field is dominated by the fashion capitals London, Milan, Paris and New York, where all dominant fashion institutions—designers, magazines, modeling agencies, fashion weeks—are based. Their influence is clearly felt in Amsterdam and Warsaw, where Polish and Dutch fashion production is concentrated. Both cities are dominant in their own country, but decidedly peripheral to transnational fashion. In fashion, as in other fields, the Netherlands is like an affluent suburb: strongly connected with international networks, with high-quality fashion and design academies delivering skilled professionals, but too small and close to fashion hubs to develop a full-fledged infrastructure. The Polish fashion industry is less institutionalized and less integrated into the transnational field. This is due both to Poland’s isolation from international fashion until 1989, and its lower prosperity and greater distance from (fashion) centers. If we see center-periphery as a continuum, the Netherlands would qualify as semi-periphery, midway between central hubs and more peripheral places like Poland.

Both Amsterdam and Warsaw are distinctly peripheral in the sense that they have relatively few fashion-related businesses, and local businesses report difficulties in connecting with local (let alone international) markets. A Polish designer explained:

The problem with the fashion market in Poland. There are too few boutiques, multibrands, to actually develop this market. It’s like a closed circle. There are fashion designers, but no shops. They want to sell it, but it runs and runs. Maybe one day it will change.Footnote 3

This is a central macro-mechanism of center-periphery relations. Global producers undercut local prices because of advantages of scale. Both retailers and local customers increasingly rely on imports, local producers are crowded out, dependence on centers increases, and local markets are not able to develop.

In a small market, money is tight. This lack of funds was evident throughout our fieldwork. Many informants had a “day job” to sustain themselves, and often worked for free. Even in paid jobs, people complained they could not produce the quality they wanted. A Dutch photographer stated, “There is more budget abroad, especially in America and Germany and France too. So you can just do better things. Prettier locations, better models, better make-up, better hair.” Less money was available for advertising and sponsoring, the main revenue source for fashion magazines. Local magazines and franchises of ELLE or Grazia rely heavily on stock photos and photoshoots from sister magazines abroad. A Dutch fashion editor explained:

English [sister magazine] has another vision, it also is another market. I find it very difficult, this buying of images. You just feel it doesn’t fit. […] it happens a lot, it all is a matter of money. But as a magazine maker I find it horrible, because I make a magazine for the Dutch market. If I were to work for France, I would do it completely differently. If we buy stuff from an American magazine, that is also made by someone who has a vision, but for an American woman. Not a Dutch woman. It doesn’t fit.

Dependence on imports makes it difficult to develop a local style. Each imported image means less work for local models, photographers, stylists, make-up and hair artists, and fewer opportunities for local creatives to showcase their work. Thus, peripheral fields are marked by a reverse of the multiplier effect of economic clusters, where economic activity propels more business. While “cumulative causation” [Wade Reference Wade2005] propels growth in centers, the absence of this effect prevents “take-off” in peripheries.

Both in Warsaw and Amsterdam, we found little diversification and specialization. Production chains were short, with little connection to related industries “upstream” (manufacturing, wholesales) or downstream (advertising, retail). Here too, we see a reversal of the mechanisms leading to clustering. Consequently, according to a Polish fashion director/journalist “the division of labor is less strict, it overlaps more, [because of] the size and the age of the industry. You cannot even call it that, an industry.” This lack of specialization, in turn, hampers professionalization. According to a Polish model with international experience:

It’s a much higher level in France, or New York, or other places. [There] every person involved, from photographer, to the stylist, to the model even the assistant, is treated as a professional. Here [Warsaw], even now, it’s still very difficult for people in this business. Because the market is not that big, it doesn’t have enough money to pay well. So they work from one job to another, mostly as freelancers. They are very ambitious, but the market does not really allow them to discover themselves, and their passion.

The lack of specialization led to complex job descriptions. We spoke to a stylist who worked as a fashion model; designers working as stylists or journalists; a journalist cum fashion director cum shop owner; a photographer doubling as hair and make-up artist; a fashion make-up artist who did movie make-up. Informants carefully “curated” professional identities as they believed “fuzzy” labor identities harmed their professional reputation. Models had separate commercial and editorial portfolios. A Dutch photographer had separate business cards: a colorful commercial one, a sober black and white card for the high fashion work that was her “passion”. A high-end fashion photographer even worked with a pseudonym, because his work for men’s magazines “excludes other work. For a long time, I shot Playboy using the name of friends who worked in ICT”.

These characteristics of peripheral fashion fields—small market, limited specialization, limited opportunities for developing local styles and talents—result from dependency. Polish and Dutch fashion producers and consumers rely on fashion centers for complex manufactured goods, like images, clothes or perfumes. They also import the most complex good of them all: meaning, embedded in images, formats, styles, brands. In return, the periphery exports raw material: people, or “talent” as the industry calls it. Poland, and to a lesser extent the Netherlands, are important harvesting grounds for fashion models: “new faces”, women and sometimes men, usually in their teens, who are scouted and prepped for careers in transnational fashion [Darr and Mears Reference Darr and Mears2017]. A network of intermediaries, so-called “bookers”, has emerged around the marketing of models for international markets. Eastern European models are especially popular because they conform to the fashion world’s aesthetic standards: white, pale, thin, tall, often blonde. It is commonly believed in the industry that “Eastern Europeans” accept worse pay and working conditions. Indeed, for Polish models, the material benefits were more attractive than for their Dutch counterparts.

The best “raw material” is usually whisked away to the centers. Photographers, fashion directors and editors complained that requests for “the best” local models were often refused. A fashion editor for a Dutch popular magazine: “Of course they never give these models to Margriet”. On the other hand, local actors often only come to believe these models are “the best” because of their central consecration. As this Polish booker explained:

Polish clients will consider hiring the model only if she did something abroad. If we have a new face, and she’s amazing, no one in Poland will work with her […] Because they want to have this proof from the international market that okay, they like this girl, so we can take her […] the big designers are not afraid of that […] So she can do more easily the best shows internationally. Really in the Milan Fashion Week, or Paris Fashion Week, they can do some amazing like Harper’s Bazaar, or ELLE magazines all over the world.

Most Polish and Dutch bookers believe that making a model work locally might “spoil their potential”. Local jobs, though sometimes well-paid, are believed to contaminate one’s chances of becoming a high-status editorial model.

Very successful peripheral creatives often move to the center: designers move their shows to Paris, photographers sell their photos in Milan or New York. Consequently, Warsaw and Amsterdam hardly have a local “high-end”. Depending on whom we talked to, the local high fashion subfield was said to be very small or nonexistent. The first group pointed to innovative design in fashion schools and local franchises of high-fashion magazines like Vogue or Harper’s Bazaar that (sometimes) promote local models, designers and photographers. This was the “fashion academy” design that we saw at Poland Fashion Week. The––much larger––second group, however, argued that such “arty” fashion hardly ever reached consumers, and dismissed local high-end franchises as “watered down”, “derivative”, “copycat” versions. This included a journalist working for Dutch Vogue:

Everything, literally everything in the Netherlands is influenced by other countries. […] I’m sorry but everything is a copy. All TV shows are copies of shows from England and America. Linda [magazine] is a copy of Oprah. You know it’s all copies […] The Netherlands, I’m really sorry, I would like it to be different, but I find little of interest here. Yeah, sure, we have our designers and we do have good people, but we simply always look outward.

A Polish fashion director summed this up succinctly: “Polish designers are people who copy brands from abroad.”

Peripheral fashion ultimately depends on the center for the production of belief: the center sets the standards, and consecrates the best. Our informants religiously kept up with international fashion through social media, magazines and visits to the major fashion weeks. A Dutch photographer explained: “I think it simply works like this: if Vogue says, next year we will be wearing leggings up to here, then here it will probably be a year later, but then we will all be wearing them up to here. Simply because everybody looks at the same magazines.” Because of the absent high-end, local fashion professionals have insufficient symbolic capital to make successful claims about aesthetic quality, especially about the most valuable aesthetic quality: high-end, innovative styles.

From this perspective, the peripheral fashion world does indeed look grim and dominated. Peripheralness produces a distinct form of disadvantage. The small, dependent market makes it difficult, but not impossible to accrue material value. However, accruing symbolic value is particularly hard because of the absent high-end and reliance on outside valuation and consecration. Following the field-theoretical logics outlined above, this raises the following question: what strategies for producing value are available to peripheral actors in this dominated field?

Peripheral strategies

Peripheral fields are small, with limited specialization, no high-end to speak of, and depend on foreign centers for standards and consecration. Given these limitations, what can actors in the (semi-)periphery do to create material and symbolic value?

Based on existing studies of cultural production, we expected most strategies to be founded on aspirations to make it in the center. While this was the case for most models, only a few of the creatives and intermediaries we spoke to actively pursued this aspirational strategy. By intermediaries we mean bookers (modelling agents), fashion journalists and other “style entrepreneurs” [Aspers Reference Aspers2012] brokering between center and periphery. The intermediaries we met usually knew the center well but were satisfied with their local lives. For creatives (photographers, stylists, designers, make-up artists), the center was more a dream than a strategy. When they talked about international success, this was often done ironically or bashfully, and their plans were quite vague: “maybe someone in New York will see my website” (designer, Poland). Insofar as creatives unfolded concrete plans, their strategies resembled what we know from central cultural production [Duffy Reference Duffy2017; Neff, Wissinger and Zukin Reference Neff, Wissinger and Zukin2005]: getting a foot in the door by working for free. However, our peripheral informants often planned to rely on Polish or Dutch connections, and they often presented their move as a temporary one.

Among our informants, fashion models most confidently and concretely pursued fully-fledged aspirational strategies to make it in the center. Modeling agencies often lure peripheral models with promises of the catwalks of Paris and New York. Once models are “signed up”, an infrastructure of mother agencies, sister agencies and model houses makes this promise quite realistic. However, this is just the beginning of an uncertain existence in a competitive, unpredictable market where most fail [Mears Reference Mears2011]. Most models have limited control over their strategies, which are mostly determined by bookers, who groom models for specific fields: editorial or commercial; local, more Paris, or maybe more New York.

Peripheral models often start out by pursuing a high-risk high-end career in the center. However, many informants shifted gear quickly: a central career is demanding, while even modest central success brings symbolic and economic benefits at home. Less prestigious commercial work abroad can be very lucrative and still impressive from a peripheral perspective. Thus, peripheral models often employ a “best of both worlds” strategy that combines peripheral and central, and often also editorial and commercial work. A semi-retired 28-year Dutch model explained:

When you’re in the fashion scene [people] are disparaging about commercial work. Like: this cash cow is just doing catalogues. Well, this cash cow now lives in a nice house on [Amsterdam canal]. And is driving a fat Mercedes. And the girl who just did editorials to put in a nice picture frame maybe has 10,000 euros in her account.

Even Dutch and Polish models with a successful international high-end career, including supermodels like (Dutch) Doutzen Kroes or (Polish) Anja Rubik, often live at home intermittently, combining prestigious central work with peripheral jobs. This mixed strategy offers an attractive balance of material and symbolic benefits, and appears to be less easily available to central models. Centrally based models run an immediate risk of reducing their symbolic value when working primarily for material gain. Thus, peripheral models often combine the best of both worlds.

While some creatives also pursued “best of both worlds” strategies, most of them were focused on a career in the local field. We call these strategies of resignation, to distinguish them from more explicitly aspirational global or best of both worlds strategies. As we will see, this does not mean that people are “resigned” to failure or a lesser life. While our sample does not include the aspirational creatives who left and made it or failed, many informants had left and returned, after working as interns, assistants, and occasionally established creatives in Paris, London, Milan, New York, Tokyo and Berlin. This was an effective strategy: they acquired artistic and technical skills, an avant-garde sense of style, and a high-status professional network to kickstart their more peripheral careers. This is what happened to a fashion editor who worked as an assistant with a famous designer in Paris: “[Dutch fashion people] all came to get clothes from me for their shoot. They were so happy a Dutch woman was working there. So I got to know Dutch [magazine], and then someone left [magazine] and I went to work there.” A Polish hairdresser/stylist experienced how international experience instantly elevated his status: “Warsaw had weak hairstyles, people didn’t like them. I was somebody different. I told them: I’m from London. It was funny because people in Warsaw started to say that this new hairstylist is from London. Good PR.”

In more peripheral fields, a stint in a fashion capital is an important rite of passage. Learning “bicultural fluency” [Tatum and Browne Reference Tatum and Browne2019] is an established part of fashion curricula. The dean of the Warsaw Fashion Academy explained that “… fashion is international. It would be stupid to prepare them on the Polish market. After the second year, they go for an internship abroad […] for Alexander McQueen, for Jon Galliano, for Marc Jacobs. They’re coming [back] with a very big experience.” Such internships socialize and consecrate new fashion recruits. The resulting symbolic capital and cosmopolitan skills are useful anywhere in the fashion field: at home, in centers, in other peripheral places.

There strategies are “resigned” because pursuing value in peripheries comes with one sacrifice: due to the missing high-end, peripheral fashion professionals must embrace a more commercial aesthetic than they personally prefer. After immersion in the fashion world, especially in fashion capitals, people are socialized into unusual, “high-fashion” standards. A Polish model explained: “My mind is a little bit poisoned. After so many years with these edgy girls. Like my friends they’re like, this girl is super cute. I’m like, her? Are you fucking kidding me? She’s ugly. She’s boring.” Some principled creatives clung to their highbrow taste. Life was difficult for those who pursued high-end styles in the periphery. They sustained themselves with a day job outside fashion, or with commercial work they disdained, worrying it would “contaminate” their professional identity.

This brings us to a difference between the two peripheral fields. In Poland, some “style entrepreneurs” tried to develop a local high-end, for instance by founding Poland Fashion Week. In 2015, the director of the event confided to us: “We wish the level one day was the same, and the Polish name was known as well like Jean Paul Gaultier, right? That will be the great moment in the fashion industry.” In the Netherlands, nobody we spoke to believed that Dutch fashion would develop its own high-end. This fits our characterization of the Netherlands as a semi-peripheral “suburb” versus Poland as a less prosperous but more autonomous peripheral field.

Most creatives understood that a peripheral career meant a commercial career. This led to specific peripheral aspirations, focused on producing specific forms of peripheral value and success. One example of this is the focus on “quality mainstream” fashion. In Amsterdam, for instance, many designers and stylists work in “quality denim”, a large market with leading labels and its own fashion week: The Amsterdam Denim Days, which “bring together the community and consumers, addicts and fanatics, brands and buyers, to celebrate its unique denim passion”.Footnote 4 Similarly, this designer sees “quality streetwear” as the future of Polish fashion:

Street wear companies […] develop their business much better than high fashion designers. […] I personally know a few people who design for their own company and sell it all over Europe [with] 50, 60, 100 shops. They do fashion shows, but they are […] mid-level, not aspiring to be another Comme des Garçons. […] Streetwear is the market now, and there is more money in it than high fashion [for] just this two percent of the population.

This strategy is reminiscent of the “popular highbrow” tastes adopted by aspirational middle classes [Eijck and Knulst Reference Eijck and Knulst2005]. The rationale is similar: aspirational middle groups campaign to upgrade their own popular tastes.

Other resigned peripheral strategies exploit the layered nature of center-periphery relations that we know from the geographical meso-approach to primary and secondary centers. An Amsterdam model first tried her luck in Paris. After being confronted with the high demands there, she moved a “step down” to South Africa, thus “cashing in” her status in this even more peripheral field. This also works the other way around: from more peripheral positions, Amsterdam and Warsaw are stepping stones to the center. When designers from Mallorca were invited to show their collections at Poland Fashion Week, a journalist observed that “for them, this is probably a step up”. Amsterdam is actively trying to establish itself as a secondary center for creatives: a semi-peripheral hub between fashion capitals and more peripheral places. A Dutch photographer explained:

Paris and London heavily influence the Netherlands. They remain ahead, but nonetheless, the Netherlands follows very quickly. But comparing Amsterdam to Cape Town, that is lagging behind with, well, everything, it is suddenly very influential. But not only the Netherlands, Europe as a whole. I am happy to be a Dutch photographer, because it makes it easy to work in Cape Town.

Intermediaries, like models but unlike creatives, also exploit the “best of both worlds”, but take a different approach: strategies of mediation. As they create material and symbolic value by brokering between local fields and centers, their main ambition is to build good networks, at home, in fashion capitals and elsewhere. For this, they do not need to make it abroad. Bookers mediate mostly “upwards”, towards the center. They scout and coach models and prep them in the transnational field. Fashion journalists, bloggers and influencers usually mediate “downwards”: they collect styles and objects internationally and adapt them for local publics. A Polish journalist described his work as “proselytizing” by spreading “fashion consciousness”. A Dutch fashion editor described her work as “translation”:

We absolutely look at the fashion shows that happen twice a year, in Paris, Milan, New York, London. It is our harvesting ground. […] many people think that we are just making stuff up. Well, forget it. It is all based on know-how from the international catwalks.

This practice accounts for the “derivative”, “copycat” feel of peripheral styles, which Hoppe [2020] has described as the semi-peripheral cycle of “imperfect imitation” leading to failed legitimacy and failure of local fields to “take off”. Incidentally, intermediaries try to reverse the flow, recommending creatives or products to their central contacts—but this is rarely successful. These transnational intermediaries are very successful in converting the “double consciousness” of (semi-)peripheral life into symbolic and material value. They are often well paid, especially if they work for prestigious magazines or agencies, and their interesting “cosmopolitan” work carries prestige.

These peripheral strategies show how center-periphery relations reproduce themselves. We find three types of strategies for creating value: aspiration is oriented towards the center or towards combining the “best of both worlds”; resignation, which is oriented towards peripheries; and bridging center and periphery through mediation. Aspirational strategies are most common among the models in our sample, who typically benefit from value production in the center and require mediation from bookers. Resigned strategies were most common for creatives: they affirm the periphery’s less prestigious position, and often depend on mediation from “translators” like journalists.

This looks like a classical Bourdieusian closed circle: inequalities within fields are supported by symbolic distinctions: commercial versus high-fashion, center versus peripheral versus even more peripheral. These distinctions shape the production of material and symbolic value, making it difficult for the dominated to produce value. Thus, inequalities breed more inequalities. However, this interpretation leaves us with some loose ends. First, most informants did not aspire to escape or challenge their dominated position. Second, informants repeatedly assured us they were satisfied with the strategies that sustained their peripheral lives—except for peripheral creatives with highbrow ambitions. A possible Bourdieusian explanation would be that people tell stories to justify the things they cannot change—a form of “false consciousness” or “post-hoc rationalization”. An alternative explanation is that peripheral actors have realistic assessments of their chances, possibly more so than people trying to make it in the center. These options point in different theoretical directions—a Marxist-Bourdieusian false consciousness versus a rationalistic perspective on people weighing their chances. However, both interpretations suggest that people can have various subjective stances vis-à-vis their “objective” social positions. To assess these conflicting explanations, we need to consider people’s reflexive understanding of their peripheral position, that is, their peripheral selves.

Peripheral selves

How does working in a peripheral field shape people’s subjectivities or their experience of self? Our first experiences, like the disheartening visit to Poland Fashion Week, led us to expect that peripheral life would be a sad affair. Theories on center-periphery relations and cultural production confirmed these grim expectations. Given the fusion of work and person in the “high commitment” [Wacquant Reference Wacquant1998] fashion world, we assumed that work in dependent, dominated cultural fields would negatively affect people’s sense of self.

This appeared to be confirmed by a peripheral culture of complaint: informants often expressed their disdain, disappointment and even disgust vis-à-vis local fashion. Take for instance Milena, an editor for a Polish franchise of an international glossy:

My friend, editor in chief of ELLE Poland, invited ELLE Czech and ELLE Russia to the Fashion Week. They were shocked by the low level of design. It was a bit embarrassing. I was embarrassed … It’s a company that wants to make money. Just imagine: they came up with the idea that to visit the Fashion Week you can buy a ticket! And the ticket prices are crazy. I cannot imagine buying a ticket for a fashion show in Paris. It’s impossible, right? You have to be a brilliant fashion editor, a brilliant photographer, a brilliant client or buyer to get an invitation. You cannot buy it. And in Poland they are selling the tickets! Come on, it’s not a cinema or theatre, it’s a venue for fashion!

Milena’s story was a typically peripheral self-performance. Delivering her displeasure with some gusto, she marked boundaries between herself and fellow-Poles, seeking common ground with us (“impossible, right?”). By telling the story through her visitors’ eyes, she adopted what G.H. Mead called “the attitude of the other toward [herself]” [Mead Reference Mead1964: 171].

Many informants, like Milena, expressed disdain towards the local field:

I don’t look at Polish fashion magazines anymore […] I stopped a couple of years ago […] I can’t find anything interesting […] it’s always the same, nothing new, nothing surprising (Editor-in-chief, Warsaw).

It’s horrible. But that’s how the Polish fashion market is. Unfortunately, it’s very small and mainstream, all the brands actually do ugly fashion, but still they sell pretty well (Designer/stylist, Warsaw).

I’m bored by Dutch fashion (Art director, Amsterdam).

I find most things very bland, very uninteresting. Most Dutch fashion magazines I don’t even buy […] Dutch magazines are so god-awful commercial […] There is no creative platform anymore (Photographer, Amsterdam).

These quotes reflect the mismatch central to peripheral fashion: between transnational “fashion-forward” tastes, often adopted by peripheral fashion professionals, and the mainstream standards and botched high-fashion ambitions of the local field. This results in boundary-drawing that is reminiscent of sociological accounts of upwardly mobile people. Like them, peripheral fashion producers combine apologetic or dismissive attitudes towards their origin with reverence for their newly adopted, more legitimate culture [Friedman Reference Friedman2012; Sennett and Cobb 1972].

The “double consciousness” of peripheral fashion workers springs from this identification with legitimate fashion culture. From novice model to senior producer, all informants saw their field and work simultaneously from a local perspective and from the (imagined) vantage point of central others. Milena’s embarrassment is a negative expression of this “seeing oneself through the eyes of others”. The positive counterpart is pride at outside recognition:

One of my productions was purchased by Chinese ELLE […] Of course that makes you proud, being from the Netherlands, thinking, wow, [my work] going abroad. They are looking at us now. Before we were only looking at other [countries], but now they are noticing us! (Art director, Amsterdam).

This pride can also be collective. Informants often referred to local photographers, models, designers or editors who had “made it” in the center, claiming them as sources of collective pride.

Many studies of disadvantaged groups have argued that disadvantage produces a double vision: the dominated see the world from their own experience, and through the eyes of higher status groups. Du Bois famously spoke of the “double consciousness” or “twoness” of African-Americans, who both see their own “Black” world, and the “White” world beyond the “veil” or “one-way mirror” [Du Bois (Reference Du Bois1903) 2008; Itzigsohn and Brown Reference Itzigsohn and Brown2015]. Feminist authors have pointed to women adopting a “male gaze” [Mulvey Reference Mulvey1989] when perceiving themselves and other women. A similar “twoness” marks the self-experience of peripheral fashion people. Du Bois’s metaphor of the one-way mirror captures both the power imbalance and the asymmetrical knowledge in this double consciousness. Those in power do not see reality on the other side; their worldview is single, united, coherent.

However, the double consciousness of our peripheral fashion workers differs fundamentally from the truly disadvantaged who were analyzed by Du Bois. Even our most precarious informants were educated, well-connected and worked in a prestigious field. From the perspective of transnational fashion, their status is marginal, but from the local perspective, they are employed in a prestigious creative field with interesting cosmopolitan connections. Their marginalization therefore does not lead to a daily experience of exclusion.

For transnational cultural producers, this double consciousness can be strategically exploited as “cosmopolitan capital” [Weenink Reference Weenink2008]. For the intermediaries, especially, a double vision is a business model: their work relies on their intimate familiarity with both worlds, and their practical “feel” for unequal dependencies. This explains their satisfaction with their lives, especially among “upwards” intermediaries who exploit the periphery’s weaknesses and support the flow of potential to the center. “Downwards” intermediaries showed a more conflicted sense of self, as their lives consisted of watering down central styles, and making do with limited budgets. Although this forced them to compromise personal tastes, they could present themselves as “proselytizing” or “educating”, while simultaneously complaining about the local fields’ low quality. They used their double consciousness to accrue material and cultural value. Their peripheral experience created a satisfied, rather aloof subjectivity.

For successful models and some best-of-both world creatives, the double consciousness did not result in alienation but in a contented, “settled” sense of self, with lives well-calibrated to make the best of their twoness. Jill, a Dutch model who loves high-end work because of its “depth” moved back from Paris to her “home base” Amsterdam, and now commutes to fashion capitals, because living in Paris caused her to “drift from herself”:

Mentally, the work is tough. You’re away from home, alone, and you are thrown into this new group of people each time. […] Everyone judges you by your looks. You have to be mentally strong, stay convinced of yourself, be confident. […] I think I’m able to find a good balance between myself and this world. But I don’t want to fully adapt, because then I lose my identity.

Jill’s alienation echoes the words of Mariusz, the Polish stylist/hairdresser who “cashed in” after working in London:

I didn’t feel very good in London. I always felt stressed […] Sometimes they’d pay me 3,000 pounds a day for a commercial. But I think with this pressure of this [high-end] compartment, these people are not so nice. […] I was totally alone. I didn’t have friends […] Nobody talks with you after work. It was not for me. I don’t like the city, I don’t like working there.

People like Jill and Mariusz have “both roots and wings” [Beck Reference Beck2002], enjoying the privileges of working in the center, and the comfortable, connected experience of home. This allows them to remain connected with their loved ones, and to show off their success: “The ones who have made it to the top, they like to work in Poland, because they like it when their mother sees it”, as Milena put it.

For most creatives and for less successful models this double consciousness is less easily translated into a profitable working life. Their experience of mismatch was expressed in complaining, as we already saw. However, the more we talked to people, the more appreciative comments we heard about peripheral life, often in explicit contrast with negative stories about life in the center. Models and creatives, even successful ones, told us about hard work, rejection and cutthroat competition. The models, moreover, reported experiences of high demands, intense scrutiny and control: endless “go-sees”, inspections of young women wearing nothing but underwear; and repeated, public measuring of hips and waist. Because of the high competition, aesthetic demands are more extreme in fashion capitals. As two Dutch models (a woman and man, respectively) explain:

When I was modeling abroad, I was skinnier than now, but losing weight was still a frequent request. When I had a bikini shoot or a fashion week coming up, I would, well, I wouldn’t say starve myself, but really watch my food. Now [in Amsterdam] I’m a size 8 and I communicate this: I’m curvy, feminine. […] I don’t want to take that anymore, it’s not worth the money, and fuck off, you know.

There is nothing glamorous about modeling in Paris, New York or Milan. When you’re there, you have to share an apartment with ten other models; you barely have warm running water; you have to chase the cockroaches away from under your kitchen sink; your underwear gets stolen from the washing line. Well, that’s just not glamorous.

These stories highlight an interesting contrast between individual and collective experience of inequality. Peripheral fashion as a field is dependent and dominated. However, on a personal level, the experiences of dependence and domination are more pronounced in the fashion centers. Daily life in winner-take-all markets consists of highly dramatized, individualized experiences of inequality, competition and rejection [Mears Reference Mears2011; Reference Mears2015]. This takes a more direct toll on people’s sense of self than collectively experienced exclusion and domination. Moreover, the stark inequalities in centers spur competition, pitting models, creatives and intermediaries against each other.

Comparisons between center and periphery sparked many “good labour stories” [Ezzy Reference Ezzy1997] about (semi-)peripheral life. Polish and Dutch fashion fields were described as informal, sociable and close-knit. An American stylist working in Amsterdam liked it because it was “cozy” and “a village”. Polish informants assured us that while they disliked Poland Fashion Week they always went “to see their friends”, and “catch up with old schoolmates”.

Moreover, informants lauded the greater freedom enjoyed in a field not defined by strict high-end standards––an insight that echoes network studies stressing the peripheral potential for innovation and creativity [Dahlander and Freriksen Reference Dahlander and Frederiksen2012; Yavo-Ayalon Reference Yavo-Ayalom2019]. A high-end photographer commuting between Warsaw and Berlin preferred Warsaw because “the potential for experimentation and innovation is higher here.” Another Warsaw designer experienced the focus on––modest–commercial success as liberating: “I can do what I like. I don’t do clothes for styling in a magazine, or Anna Wintour or somebody. I prefer clothes for normal people for the street. That, for me, is the most important.”

Third, peripheral working conditions are described as more “humane”. For instance, peripheral modelling agencies take better care of their models: “Elite or other hip agencies don’t give an ass whether you finish school or not. They will just send you, hop, abroad, hop, to Paris” (Booker, Amsterdam). Moreover, financial arrangements are often more generous:

Paris, I hate the commission they take from the models. It’s the highest in the world. In your pocket you’re left with 40%. In Milan you’re left with 60%. In Poland you get 80%. Because everywhere you have to pay tax, and the commission. The commission in Paris kills you. But still it’s very snobbish to say that you’re successful in Paris (Model, Poland).

Because of such exploitative conditions, many informants found that peripheral work was more profitable. This refers, however, to purely material profit, with limited symbolic value in the field. It requires a rejection of the “belief” that prioritizes symbolic value over material gain.

The strategies of resignation to the periphery often hinged on the rejection of this belief. Those who embraced these strategies saw fashion primarily as a path to money and a good life, rather than the fullfilment of self. Another Amsterdam model stated:

I prefer the secondary market […] that’s not exactly fashion, but I feel there is more of a challenge. The jobs are more commercial, the atmosphere is more relaxed. I also prefer commercial work for the money. It’s more profitable. It’s nice to work for large fashion houses or magazines, but at the end of the day the bills need to get paid. And you can’t do that with beautiful pictures.

In more peripheral cities, one can think of fashion as “just work”. Many informants noted the advantage of this disengagement. It prevents the colonization of life and self, and shields one from the harshness of fashion centers:

I love what I do, love to be creative but I don’t like the industry and most of the people in it. I mean they’re just shallow. It’s not an intellectual industry. It’s not. So superficiality has much to do with it. I’s really sad. You know if I’m really honest, I’m not going to bla bla: it’s got a very dark side. It changes people. They think of themselves as God knows what. Even here, in this very small village [laughs]. It’s very, something that creeps into their brains, making them think they are “it”. Know what I mean? Where does that come from? (Stylist, Amsterdam).

In the fashion centers, value and self overlap: the quest for recognition and consecration becomes synonymous with the realization of self. This life is tempting: enthralled informants described the energy and exhilaration that comes from the collective production of beauty and belief in the fashion capitals. But peripheral actors have a luxury that central actors do not have: the option of stepping back and disengaging. Their peripheral world is less energetic and less coherent, but offers other opportunities for good work and a good life. While the chances of making it big are lower in the periphery, “twoness” can also be experienced as a privilege: it allows fashion workers to consider what it means to be the periphery, what it means to be the center, and to consider both options in the light of work, value, and self.

Conclusion Theorizing Peripheralness as a Dimension of Inequality

In this article, we analyzed the interconnections between structure, strategy and self in peripheral cultural production. This analysis aims to contribute to a theory of the periphery that conceptualizes peripheralness as a distinct constellation of structural condition, possibilities for strategic action and subjective experience and, thus, as a specific axis of inequality embedded in transnational center-periphery relations.

Our studies found that Polish and Dutch fashion fields had much in common, despite great differences in prosperity, politics, culture and transnational integration. We argue that these similarities are the result of “periphereality” [Yavo-Ayalon Reference Yavo-Ayalom2019]. Semi-peripheral cultural fields constrain and shape possibilities for workers for creating material value (income, profits, stable careers, thriving businesses) and symbolic value (awards, jobs with prestigious designers, magazines, or photographers, engagements with high-end brands). Hence, more peripheral cultural fields are peripheral worlds with specific structural characteristics, marked by dependence on international fashion capitals for goods and for aesthetic valuation and consecration. To create value, Polish and Dutch fashion workers employ peripheral strategies. These strategies for producing value are sometimes based on the aspiration to make it in the center or in exploiting “the best of both worlds”, but more commonly are focused on mediation between centers and peripheries, or resignation vis-à-vis their peripheral position. Finally, producers in peripheries have peripheral selves: subjectivities that emerge from working in an industry that depends on central “others” for valuation and consecration.

Thus, our analysis connects objective conditions of peripheral and semi-peripheral cultural production with subjective experiences of peripheral life. We argue that the self-experience of peripheral fashion workers is marked by a “double consciousness”: they simultaneously see the world from their peripheral perspective, and through the eyes of (imagined) central “others”. For these relatively privileged cultural workers, this experience of “twoness” [Du Bois (Reference Du Bois1903) 2008], was both a burden and an asset. Their peripheral strategies allowed them to cope with, and sometimes even exploit their double vision.

This analysis has some limitations. First, our observations and interviews are skewed towards the “stayers”. During our research in fashion centers, we met some Dutch and Poles who left to “make it” elsewhere, but they are not included in this analysis. Moreover, our field analysis is based on ethnography and interviews, and therefore on perceptions of structure, strategy and self rather than on “hard” institutional or field data. Finally, because our Polish and Dutch samples differ, we did not conduct a systematic cross-national comparison. Instead, we offer an abductive theoretization that focuses on similarities between these fields, across a number of professions and field positions. Further research in other (semi-)peripheral (cultural) fields could expand and test our insights, for instance with systematic institutional data to map structural characteristics of peripheries and dynamics and degrees of peripheralization. It could also develop a more systematic comparison of more semi-peripheral cities like Amsterdam, more peripheral cities like Warsaw, and possibly even more peripheral places like Cape Town (or Łódź). Moreover, follow-up studies could look at strategies and self-experiences of “stayers” and more and less successful “leavers”, or more systematically explore types and degrees of peripheralness, including peripheral fields in the Global South.

Our analysis of peripheral worlds, strategies and selves has implications beyond the study of fashion and cultural production. It sheds new light on our understanding of center-periphery relations, and thus advances our understanding of globalization. Center-periphery models underlie virtually all debates about globalization, but as Buchholz [2018: 19] observes: “the center-periphery model itself has remained curiously undertheorized”. We found that center-periphery theories are scattered across different disciplines that highlight different analytical mechanisms. Macro-approaches, like world-systems theory or transnational field theory, focus on asymmetrical dependencies, exploitation and (cultural) domination. Organization scholars and geographers stress meso-dynamics, like the creation (or not) of economic clusters and value chains. Network scholars analyze micro-processes and the opportunities afforded by network positions in cores, peripheries, or in-between. Despite these differences, however, all three approaches have overwhelmingly focused on centers and hubs, ignoring peripheries and processes of peripheralization. Our analysis shifts the view to the periphery, and integrates dynamics on the macro-, meso- and micro-levels by linking transnational and field structures with individual strategies and experiences. This move also allows us to think of peripheralness as a continuum that ranges from “very central” to “very peripheral”. Like all dimensions of inequality, peripheralness can pertain to people but also institutions and places.

This article offers building blocks for a new theory of the periphery. The distinct characteristics of peripheries partly result from the inverse of well-known mechanisms producing centralization: increasing dependence and stagnation through asymmetrical flows, fewer network connections and limited clustering and specialization. Our analysis also underlines the importance of imitation as a form of dependence that is especially important in cultural fields defines by style [Hoppe Reference Hoppe, Cattani, Ferriani, Godart and Sgourev2020]. However, other aspects of peripheral fields seem uniquely peripheral, and to our knowledge have not been theorized before: the absent high-end, extensive networks of upward and downward transnational intermediaries, and specifically peripheral strategies like pursuing the “best of both worlds”, developing “quality mainstream” or teaching “cosmopolitan skills”. Our analysis also points to the dynamics sustaining more peripheral fields. First, more peripheral fields persist because local actors are invested in sustaining them, and because many national actors and institutions are invested in maintaining a local cultural field [cf. Kuipers Reference Kuipers2015]. Moreover, local fashion fields persist because the transnational fashion system—and therefore, the center—needs them, as markets and as harvesting grounds for labor or ideas. Thus, the dependence is asymmetrical, but mutual: centers and peripheries are interdependent.

We hope this analysis clears the path for new theoretizations of peripheries that bridge individual, interpersonal, organizational and structural dynamics of peripheralization. For instance, we think the budding literature on transnational (cultural) fields [Buchholz Reference Buchholz2016; Kuipers Reference Kuipers2011, Reference Kuipers2015; LaVie and Varriale Reference Lavie and Varriale2019; Sapiro Reference Sapiro2010] could benefit from the more processual, dynamic insights from network analysis, and the “layered” understandings of multiple centers and peripheries in geographical and organizational meso-theories.

Second, the view from the periphery uncovered some blind spots in existing approaches to cultural production, notably field theory in its various guises. Most work of cultural production assumes that actors strategically operate to achieve consecration, legitimation or domination. Most of our informants, however, seemed quite content to pursue less aspirational strategies focusing on good work or a good life. Some of this reported satisfaction may result from compensation of cognitive dissonance. However, it often seemed well-argued and grounded in well-informed understandings of both periphery and center. The view from the periphery therefore exposes and questions theories of action and motivation embedded in field theory. To understand human action, we should take seriously “other good reasons for practice” [Friedland Reference Friedland2013]: avoiding failure, pursuing beauty, being creative, living a good life or, as Milena observed, “wanting your mother to see you”.

The view from the periphery also highlighted another shortcoming of field theory: its lack of attention to self and self-experience. In cultural centers, it is easy to assume a seamless overlap between “objective” social position and “subjective” self-experience. Field theoretical concepts such as habitus [Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1993, (1992) Reference Bourdieu1996] or strategy [Fligstein and McAdam Reference Fligstein and McAdam2012] offer theories of action but not of subjectivity or self. This, again, becomes evident in the periphery, where people simultaneously imagine themselves from their local perspective and through the eyes of imagined “central” Others [cf. Mead (1932) Reference Mead1964]. Thus, peripheral actors, like other dominated actors, have a “double consciousness”. Readers may be surprised to see Du Bois’s notion of “double consciousness” and “the one-way mirror” applied to 21st century white European fashion professionals—even including a professional group, European fashion models, that benefit from their whiteness [Mears Reference Mears2020]. We see this as another step towards Du Bois’s (well-deserved) inclusion in the sociological canon as a general theorist of global inequalities, rather than a specific theorist of early 1900s American race relations.

This leads us to the final implication of our analysis of the periphery as structure and experience. We propose to see peripheralness as a distinct axis of inequality: a form of social dis/advantage springing from global asymmetrical dependencies. However, peripheralness is an unusual form of inequality. While peripheral fields are dependent and dominated, relations within the field may be relatively egalitarian compared with the harsh inequalities of global centers. Peripheral fashion workers are cut off from the highest rewards, but are also spared painful individualized experiences of exclusion, rejection and failure. In other words: peripheralness is a form of inequality that is experienced collectively rather than individually. This takes out much of the sting of this particular form of domination: on a day-to-day basis, it does not hurt much. On the contrary, the association with a prestigious transnational field may even yield symbolic capital in the local field. This may explain why many peripheral fashion workers prefer to be a big, small or medium-sized fish in a small—dominated and dependent—pond, rather than pursuing the glamorous, harsh life in a big pond.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003975622000224.