Introduction

In the study of world politics, regions are an odd concept. On the one hand, their existence in the practice of politics is most often taken for granted. Political agents would seldom contest if one considered a varied range of geographic aggregates, such as Asia, the Amazon, or Andalucía, to be regions. On the other hand, what makes a region a region, who belongs to them, and how they affect world politics are questions that could spark controversy.Footnote 1 Whereas Asia is a massive continent, including multiple states, cultures, and geographies, Andalucía is a juridically bounded subnational entity, and the Amazon is foremost a cross-border ecosystem. In common, these regions seem easily discernible territorial cuts of the world, but delineating their limits, who falls inside them, and which actors (if any) can act on their behalf is a much more complex social and political matter.

This contradiction of regions as both intuitive and intricate is intrinsic to their status and effects in world politics. Regions become a useful category for the analysis and practice of world politics when it comes to describing territorial entities whose boundaries are blurry, spaces that we often do not know when it starts and where it ends. Thus, the political effects of regions are associated with their ability to produce and reproduce territorial boundaries, differentiating ‘we from them’ and ‘inside from outside’.Footnote 2 However, different from the borders of modern states, regional boundaries are hardly given; they tend to be blurred, contested, and dependent on the social relations that recursively animate and reproduce them.Footnote 3 In a state system, which is defined by crisp sovereign borders, regions emerge as anomalous entities that, just like states, are defined by their territorial boundaries but whose boundaries are most often in the making.Footnote 4 In this sense, as Luk Van Langenhove posits, the political existence of regions ‘may be defined by what they are not: they are not sovereign states’.Footnote 5 At the same time, regions are intrinsically territorialised and, thus, distinct from the global as well.Footnote 6 Therefore, regions play a crucial role in world politics as forms of political territoriality that escape the framework of nation-states and their clear-cut linear borders.

This contradiction of the region as both unbounded and bounded manifests in the two key concepts used in its study.Footnote 7 The boundary-raising character of regions has been associated with what we call regionalism: the political project and programme of region-making, which is centred on producing regional boundaries that are often delimited by membership in regional institutions.Footnote 8 In parallel, the ‘unowned process’Footnote 9 of region-making through the undirected binding of social actors is associated with the concept of regionalisation, which tends to describe the ‘patterns of cooperation, integration, complementarity and convergence’Footnote 10 that are often not directed by any specific actors or states.Footnote 11 Although indissociable in practice, the concepts of regionalism and regionalisation represent two archetypical pathways for the emergence of regions that can be more or less salient in different cases. Whereas the latter stresses region-building as the binding of relations among actors, the first focuses on the bounding of these relations within a given territorialised boundary.

In the current article, following perspectives from political geography and relational sociology, I argue that the concept of regionalism reflects the production of regions as territory and that regionalisation reflects its production as networks.Footnote 12 Processes of territorialisation border the social space, ‘constructing inside/outside divides’,Footnote 13 while network processes produce the social space through interconnectivity and interdependence.Footnote 14 I further argue that understanding the interplay between regionalism – the territorialised and bounded aspect of regions – and regionalisation – the networked-relational aspect of regions – is crucial in understanding both their making and makings in world politics. That is, the very process that constitutes regions, their making, is at the root of their effects, their makings. On the one hand, unshielded by the norm of sovereignty, regions exist through the continuous making of their boundaries while also shaping the political world through their bounding, by producing territorially demarcated us–them and inside–outside markers besides those of states. On the other hand, at the same time, regions are built and held together through a web of relations, which, once in place, organise the regional world, binding together its constitutive social actors. Hence, the making of regions as political communities through the dynamics of binding and bounding also shapes their makings in world politics.

At the core of this dialectic between territory and network, the bounding and binding of region-making can be understood as hooked by brokerage structures. Brokerage refers to the mediating roles in networks – a position between one or more actors that would otherwise be disconnected.Footnote 15 Brokerage positions allow for some actors to at least exert three roles that bring social entities to life: they can coordinate relations within their groups; they can represent their groups vis-à-vis external actors; and they can gatekeep relations from the outside.Footnote 16 The binding and bounding of regions can be understood as a combination of these roles. Regionalisation reflects this coordinating role that some actors may acquire purposefully or not in binding regions as cohesive social entities. Regionalism reflects the political project of sustaining and controlling the boundaries of a region and the interactions between its inside and outside.

This analytical lens allows for understanding the emergence of regions as an ever-ongoing process relying on internal cohesion-building and external boundary reproduction, thus turning the making of the region into the root of its makings. These ideal-typical pathways go beyond a traditional analysis of region-making, opening the possibility of investigating multiple empirical pathways in which the regional boundaries are produced and actors therein are tied together. It avoids the universalisation of Eurocentric integration benchmarks while permitting comparison among the types and forms of region-making.Footnote 17 Indeed, regions may have distinct capacities for binding actors and controlling boundaries; they can also vary in terms of which actors they bind together, which others they exclude, and the network positionalities of them all. In any case, the ways in which the often-diffuse process of regionalisation and the more strategic projects of regionalism interplay becomes an empirical question.

In the remainder of the article, I develop this theoretical approach and apply it to the study of regionalism surrounding the Amazon basin and rainforest ecosystem. This case is a useful application for three main reasons. First, from the perspective of most actors in the modern international system, until late in the twentieth century, the Amazon was mainly the periphery of a few states, not a sociopolitical space of its own. This allows us to trace the emergence of its regionalism and regionalisation in world politics almost de novo.

Second, it illustrates how this framework foregrounds the dynamics of a region that does not fit traditional models. The Amazon case presents a type of region – regions anchored in cross-border ecosystems – whose study and theorisation are still incipient in world politics.Footnote 18 As a region, the Amazon has emerged internationally as a defensive response of local state actors to global awareness of its preservation as an ecosystem. It was a way to coordinate efforts to maintain national borders as the main boundary of the region and local states as its main representatives and gatekeepers in world politics. Furthermore, the binding and bounding of the Amazon as a region and its effects on the global governance of its underlying ecosystem are not coupled with strong shared identities, high levels of cross-border socioeconomic flows, or robust institutional integration. Hence, the case also illustrates the capacity of this relational framework to shed light on the makings of a region, even when it does not achieve the usual benchmarks of regional integration.

The present article is divided into three sections. The first section reviews the previous literature on regionalism and regionalisation in world politics to demonstrate how these can be better understood as archetypical region-building pathways through boundary-raising and network-binding, respectively. The second section presents brokerage mechanisms as the glue linking processes of regionalisation and regionalism in the making of regions. The third section turns to region-building in the Amazon. I first offer a brief discussion of binding and bounding mechanisms in the process of consolidation of the region around the Amazon Cooperation Treaty (ACT). The section then focuses on the manifestation of the Amazon as a region in global environmental governance by analysing its role in bounding and binding interactions in UN-level negotiations involving the ecosystem from 1992 to 2018. The current study uses original data extracted from Earth Negotiation BulletinsFootnote 19 reports to analyse the networks of interactions, the positionality of Amazon actors therein, and their patterns of relationship with non-Amazon actors.

Regionalism and regionalisation: Revisiting pathways of region-building in world politics

Regions are political territorialities that are continuously under construction. As two relevant theorists of regions in world politics posit, ‘mostly when we speak of regions, we actually mean regions in the making. There are no “natural” or “given” regions, but these are created and recreated in the process of global transformation.’Footnote 20 I further argue that we can only make sense of the ways in which regions affect world politics in such a processual matter through their constitution. Regions shape the world by organising the forms of political territoriality that escape the sovereignty model of the modern international order. Territorial stability is at the core of modern state sovereignty.Footnote 21 In contrast, regions have much blurrier and more contested boundaries that depend on the social relations that recursively animate and reproduce them. As the Brexit and COVID-19 pandemic responses have shown, even strongly institutionalised regional organisations such as the European Union (EU) still demand significant political mobilisation to maintain its boundaries and cohesion as a political entity. Therefore, regions exist and affect world politics by reproducing themselves as bounded entities. The making and makings of regions cannot be fully disentangled; regions affect world politics through their becoming.

In international relations, the emergence of regions has been associated with two archetypical processes: regionalism and regionalisation. The definitions of regionalism vary, but in common, they tend to focus on the production of markers that distinguish between those inside and those outside a region. Some authors have focused on the construction of shared identities, or the production of some level of ‘we-ness’.Footnote 22 Iver B. Neumann stresses how the process of regional collective identity formation entails the inclusion of some and exclusion of others.Footnote 23 Other authors define regionalism as the institutionalisation of regions as formal organisations, which is most often championed by states as a means of jointly governing a shared political space that they cannot otherwise govern through their state sovereignty alone.Footnote 24 These dynamics of institutionalisation also produce an inside and outside, including and integrating the members of regional institutions and excluding the rest.Footnote 25 In addition, both the social focus on identity construction and institutional focus on organisations tend to describe somewhat reflexive, intentional projects of region-building. In regionalism, political actors tend to own their region-making efforts and actively work to construct them as distinctive territorial markers. Therefore, at the core of regionalism is the bounding of regions, constructing and sustaining the demarcations that allow for distinguishing those who are inside of a delimited territoriality from those who are left outside.

The concept of regionalisation, in turn, refers to the less purposeful, unowned process in which regions emerge out of bundles of greater social interactions. Regionalisation is associated with a more diffuse social and economic process, which contrasts with the more politically driven nature of regionalism.Footnote 26 It denotes what some see as the de facto emergence of regions and their constitutive societal integration.Footnote 27 Thus, regionalisation is the binding of social actors together, producing a critical mass of interactions that constitutes a region as a distinctive social space.

In this sense, regionalisation is often seen as the desired outcome of regionalism, but in practice, the latter may or may not produce greater regional integration. Julia Gray's work on zombie regionalismFootnote 28 shows that regional organisations often fail to deliver their intended integration outcomes. Still, as I explore in the Amazon case, regionalism may not have regionalisation as its end goal; it may just bind together joint action sufficient to sustain a group boundary. This is the case of several region-building projects in the Global South that work as sovereignty clubs where sovereignty preservation has taken precedence over transnational integration.Footnote 29 The notion of defensive regionalism against global hegemonic influences, prevalent in Latin America,Footnote 30 or of a virtual regionalism to bolster the domestic legitimacy of autocratic regimes, as identified in Central Asia,Footnote 31 both reflect a similar dynamic.

Conversely, regions can affect world politics without a political project in place. At the international level, the notion of regional security complexes captures how regions can emerge out of shared relationships, regardless of intentional region-building.Footnote 32 Similarly, regionalised informal governance arrangements that escape the scope of specific regional organisations can be seen as a more fluid cluster of sociopolitical relations, with more flexible boundaries.Footnote 33 Perhaps, an even more intuitive description of regionalisation without regionalism is John Harrison and Michael Hoyler's concept of transmetropolitan regions, where social interactions merge urban areas together and beyond their jurisdiction, producing a novel and unbounded spatial assemblage.Footnote 34

Therefore, although regionalism and regionalisation are most often indissociable dimensions of regions, in practice, they describe two archetypical pathways of region-making. Regionalism describes the bounding of regions, the production of more or less crisp and institutionalised makers that allow its territorialisation, the production of we and them, along with inside-outside distinctions. Regionalisation denotes the binding of regions and the amalgamation of social interactions, constituting a distinctive social space. Whereas regionalism emphasises the more deliberate political project of region-building, regionalisation describes a potentially more autonomous social process that may or may not be tied to a political project. In world politics, regionalism tends to be more prominent because of its political nature, affording agency to those who can produce and control regional boundaries.Footnote 35 On the other hand, regionalism that produces empty boundaries and is unable to spur internal binding tends to be dismissed as irrelevant.Footnote 36

I propose that the bounding of regions can be seen as the mechanism undergirding regionalism and that the binding of regions can be seen as the mechanism producing regionalisation. I later argue that regions always rely on tying the dynamics of regionalism and regionalisation, the mechanisms of binding and bounding of regions that sustain a region's territoriality. Still, we should not assume that any of these pathways has precedence over the other. These are two archetypes of region-making that can be more or less salient in the constitution of any given region. Figure 1 shows regionalism and regionalisation as two dimensions in a property space.Footnote 37 The arrows coming from the bottom left to the upper right of the figure show some of the multiple pathways of region-making. Regions are most salient as political entities the closer they are to the top-right corner of the figure and less so the closer they are to the bottom left corner.

Figure 1. Pathways of region-making in world politics.

This framework allows us to map and expand on previous typologies of region-making. Björn Hettne and Fredrik Söderbaum's intuitive path to ‘regioness’, starting from latent regional spaces, going through non-institutionalised regional complexes, and finally reaching progressively bounded and cohesive regional communities, can be read as describing pathways closer to the straight diagonal of Figure 1.Footnote 38 Theories of regional integration in general – and the neofunctionalist tradition in particular – also tend to see regionalisation and regionalism driving one another in a virtuous cycle.Footnote 39 Nevertheless, in reality, regions vary from this ideal pathway. They can be built primarily through regionalism's bounding mechanism of institutionalisation or identity demarcation, or they can emerge out of a more diffuse process of regionalisation.

The regionalism pathway is more well known, where the boundaries of the region are institutionalised in a top-down manner through a political project. The European Union and its model of regional integration is perhaps the most concrete example of this pathway. The arrow bending towards the top-left of the graph illustrates this regionalism-led process of region-making. However, for some regions, institutionalisation may follow the densification of social relations in a regional space. This is a pathway more common in smaller scales, as in conurbations that overflow the jurisdictions of multiple cities and create new urban spaces that are only later institutionalised,Footnote 40 or in micro-regionalism across the sides of national borders.Footnote 41 At the international level, ASEAN's creation and evolution is closer to a regionalisation-led pathway, in which intuitional depth often followed the densification of relationships and countries’ interdependencies as part of an emerging regional security complex.Footnote 42

However, regions can also stabilise at any point in the map, having either stronger boundaries or stronger internal binding. This framework recognises that regions can have many trajectories and types, while also acknowledging that some have a more salient political existence by combining strong binding and bounding dynamics. All types of regions positioned in Figure 1 can be understood as stabilisations of these processes at different degrees of regionalism and regionalisation. Regional communities can equally have either stronger formal boundaries (for instance, the EU) or have a more complexly bounded bundle of tight relations (for instance, ASEAN). Other regions can exist without clear political demarcation. This is the case of smaller de facto regions, such as the aforementioned transmetropolitan areas, but also of some much larger regional security complexes, such as the Middle East's ‘regionalization without regionalism’.Footnote 43 In turn, regionalism may never produce regionalisation, leaving its well-defined regional boundaries empty of any greater integration, as with the manifold ‘zombie’ regional organisations that fail to spur integration within their boundaries.Footnote 44 Furthermore, regionalism might not even have regionalisation as its main goal and instead be centred on sustaining joint state action and boundary preservation, as I argue is the case for the Amazon and many other club-like sovereignty-preserving regionalisms in the Global South.Footnote 45

In any case, regions’ constitution and stabilisation rely upon combinations of mechanisms of bounding and binding. The question then becomes how to make sense of the entanglement between these two archetypical mechanisms and processes. In political geography, regions are often seen as scales that interweave the network and territorial ontologies of the social space.Footnote 46 Just as regionalism, processes of territorialisation border the social space, ‘constructing inside/outside divides’.Footnote 47 Just as with regionalisation, network processes produce social space through interconnectivity and interdependence.Footnote 48 Following these perspectives, I argue that we should explore the production of regions through this co-constitutive entanglement of network and territorial processes – of relations and boundaries.

To make sense of this duality of regions, as both seemingly coherent entities and bundles of relations, I propose a network theory of a region's making and makings. As discussed before, regions can have either their networks or boundaries be more salient, but these are always in a dialectical relation. Networks structure the conditions of the possibility for stabilising regional boundaries, while the contested delineation of these boundaries helps condition the production of these relations within its borders. In other words, as I argue in the next section, regions cannot be a product of networks or territorial boundaries alone; instead, they are produced out of networked territorialities.

Networking territoriality: The binding and bounding of regions as political entities

I propose that regions are best understood as network territorialities produced through some combination of binding and bounding mechanisms. This perspective is grounded on a processual–relational ontology that conceives of the social world as composed of webs of relations.Footnote 49 Thus, the existence of social entities, their boundaries, and their attributes are not assumed but rather taken as the object of investigation.Footnote 50 The contours and content of seemingly cohesive social entities, such as states and regions, then become the puzzle. This relational world can be depicted and investigated as networks.

Networks are patterns of relations that constitute complex social entities and the structures that shape their actors. Network structures constituting any given social entity, however, are seldom properly bounded. Even stable entities, such as states, are composed of networks of relations that escape their boundaries. From a relational perspective, hence, no matter how seemingly stable an entity is, its boundaries are always in constant tension with its underlying networks. This becomes particularly relevant if the entities we aim to study have intrinsically blurred boundaries, as regions tend to have.

In network terms, socially bounded entities become able to reproduce themselves when their boundaries enclose a cluster of relations that is internally – rather than externally – denser.Footnote 51 Charles Tilly speaks specifically about the relational production of political communities, such as regions, in these terms;Footnote 52 he argues that a clustered network topography is what affords a political community to sustain a public representation of their boundaries and to retain denser relations within it. Daniel Nexon further argues that this combination of stable categorical boundaries and dense internal social relations shapes the ability of social entities to act collectively and acquire corporate agency.Footnote 53 This is because a clustered network structure and clearer boundaries allow some actors within that corporate entity to occupy brokerage positions, linking the inside and outside of such an entity.Footnote 54 These brokerage position works as bridges in networks, where an actor links one or more other actors that would otherwise be disconnected.Footnote 55 Thus, brokerage positions occupy ‘sites of difference’ that allow some actors to elect one side as the inside and the other as the outside, mediating interactions across that boundary.Footnote 56

The notion of brokerage positions in network theory allows us to think about the interlocking of binding and bounding mechanisms and, thus, about the entanglement between the process of regionalism and regionalisation. To make this point clear, we can look at Roger V. Gould and Roberto M. Fernandez's typology of modes of brokerage, which takes into consideration both group boundaries and network structures.Footnote 57 They present several modes of mediation associated with brokerage, but three are particularly relevant here: coordination, representation, and gatekeeping. Coordination is the mode of brokerage possible within a given boundary. It is what holds a group together, thus being akin to the mechanism of binding that we associate with regionalisation. Representation and gatekeeping are modes of brokerage between a group and external actors. Representation refers to acting on behalf of a group vis-à-vis external actors, and gatekeeping refers to the control of flows coming from the outside. In both cases, these modes of brokerage are rooted in maintaining inside-outside delimitation and, thus, can be associated with the bounding mechanism underpinning regionalism. Figure 2 illustrates these three modes of brokerage and their association with the mechanisms of binding and bounding that we advance here.

Figure 2. Binding and bounding mechanisms of social entity stabilisation.

The interlocking of regionalism and regionalisation can be understood by combinations of these binding and bounding dynamics of brokerage. It is possible, then, to reinterpret the regionalism and regionalisation pathways as the transformations in a network of relations occurring through these mechanisms of binding and bounding. In either case, actors mobilise perceptions of shared territoriality to produce a distinctive cluster of relations and couple this cluster with a recognisable boundary.

Figure 3 illustrates both pathways of region-making from the latent territoriality of geographical proximity in structure (a) to the cohesive network structure of a region (d), delimited by an institutional boundary and with defined insiders and outsiders. In the regionalisation path, precedence is taken by the more spontaneous social interactions binding geographical proximity into a cluster of relations, creating the opportunity for a boundary to demarcate a region politically. In the regionalism path, in turn, boundary-making takes the lead, and shared membership to a regional identity or institution is what drives changes in the topography of relations. At any point in either pathway, regions affect world politics in the same ways by producing novel networked configurations of political territorialisation.

Figure 3. Processual–relational pathways of region-making in world politics.

As discussed before, the binding of regionalisation may not be politically demarcated, and the boundaries of regionalism may not spur denser relations within the region and still have effects. Blurrily delimited de facto regions or regional security complexes, even if they do not have crisp boundaries, still affect world politics by pulling actors together to produce coordination that would otherwise be absent. Regionalism failing to produce regionalisation can be equally relevant if its boundaries allow for some degree of control between the inside and outside of its boundary. Furthermore, the same regional boundary can have more success in delimiting some types of relations (that is, economic, political, social) and less in others.

Even more importantly, this novel configuration of political territorialisation by no means needs to be circumscribed to the geographical frontiers of a region vis-à-vis external neighbours. Within a geographically contiguous space, it can include some actors (often state actors and powerful interest groups) and exclude other actors (often marginalised non-state actors). Equally, regions can affect world politics far beyond their local geographical space by binding and bounding actors in international forums, for instance.

The case of the Amazon rainforest is emblematic of these nuances. Its main regional organisation, the Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization (ACTO), is often seen as having limited ability to affect the governance of the ecosystem in each of its member states. Yet as we discuss below, the regionalism anchored in the ACTO still produces the territorialities that have bound the Amazon as a region in the global governance of the ecosystem. In doing so, it defines the inside and outside of the ecosystem's governance, as well as who is included and who is excluded therein. As I show, this coordination allows for Amazon adjacent states to gatekeep the participation of non-adjacent actors in the global governance of the region and to retain the ability to represent the region.

The binding and bounding of the Amazon region

Ecosystemic politics and the making of the Amazon as a region

The contemporary existence of the Amazon as a region in world politics is strongly tied to its definition as an ecosystem. Ecosystems can be defined in multiple ways, but they usually refer to ‘relatively large units of land containing a distinct assemblage of natural communities and species’.Footnote 58 In the case of the Amazon, this ecosystemic spatiality is anchored in the rainforest and river basin after which the region is named. Although this link can seem intuitive, the ways in which this space is politicised as territoriality is a much more contentious matter. For the indigenous peoples inhabiting this ecosystem, the Amazon River and rainforest are ontologically productive of their world, containing an intricate assemblage of territorialities.Footnote 59 In contrast, for states whose sovereignty overlays this ecosystem, the Amazon has long been the frontier of their world, a space to be territorialised.Footnote 60 For extra-regional actors in global governance, the Amazon has gained shape through the natural scientific boundaries of its ecosystem, given the services it provides the whole world through the biodiversity it harbours and its role in mitigating climate change.Footnote 61

As with any geopolitical space, these multiple latent territorialities are always in tension when it comes to delineating regional boundaries. Through the theoretical lenses presented in the current article, we can better understand the interplay between these territorialities and how one logic has come to subordinate the others. Specifically, it helps us understand how Amazon regionalism is a product of what Elana Wilson Rowe calls ecosystemic politics; that is, it is a consequence of anchoring political cooperation in the transboundary physical geography of an ecosystem.Footnote 62 In the case of the Amazon, its natural scientific definition as an ecosystem providing services to the whole planet produces a territoriality that challenges state borders. The Amazon's emergence as a political region was a reaction to its definition as a globally significant ecosystem, remobilising this natural-scientific conception to fit the territorialities of Amazonian nation-states. As I shall show, this was a process driven by binding and bounding mechanisms that privilege these states in the governance of this ecosystem.

As with most contemporary political spaces, the current territorialisation of the Amazon is rooted in the dynamics of colonisation and modern state-building. This process was driven by the clashing territorialities of the national states governing from distant capitals, local and indigenous inhabitants, and external interested parties.Footnote 63 After formal independence, the territoriality of the states whose sovereignty extended over the Amazon – the one delimitated by their national borders – tended to prevail. Each Amazon state sought to extend its presence and control over the ecosystem, primarily through linking the region to their economic models of development.Footnote 64 Needless to say, these endeavours disregarded the border-traversing spatiality of the ecosystem itself and, even more so, the indigenous livelihoods that inhabit the forest.Footnote 65 In other words, the territorialities of the Amazon as the periphery of Amazon adjacent states were mobilised to the detriment of other shared territorialities within the ecosystem that could not be accommodated within the lines of national borders. The regionalisation of the Amazon as a whole, the interconnectivity among local populations, was progressively subordinated to these states.

To be more specific, before the late 1960s, regional cooperation among states was limited to treaties of river navigation as an effort to enhance control of the states over the border traversing character of the Amazon basin.Footnote 66 Efforts to conceive of the Amazon as an integral territoriality were only marginally raised by early conservationists and some indigenous human rights advocacy groups.Footnote 67 These initiatives had a low capacity to shape outcomes, particularly because of concerted action among the states.Footnote 68 Standing out among these endeavours was UNESCO's International Institute of the Hylean Amazon, which aimed at scientific exploration of the natural resources of the rainforest surrounding the Amazon River basin. After an initial good reception by local states, the institute ended up being refused by the Brazilian Congress, and the initiative sunk.Footnote 69 Instead, a few years later, Brazil would create its own National Research Institute of the Amazon emulating the mandate of the failed UNESCO initiative.Footnote 70 This episode is relevant because it shows one of the first international attempts to govern the Amazon as a totality, one grounded on the region's underlying ecosystem. The border-traversing nature of the project including extra-regional powers was the main cause of Brazil's reaction. Brazil's military establishment saw the UNESCO initiative as manifesting foreign ‘desires of interference’ and threatening national security and sovereignty over its most vulnerable frontier.Footnote 71

Still, the Brazilian response took in this natural-scientific conception of the Amazon and domesticated it within the bounds of its sovereignty. This tension is representative of what has, since then, driven the constitution of the Amazon as a region. The more global efforts to conceive and govern the Amazon as an ecosystem increased, the more Amazon-adjacent states would strive to harness the norm of sovereignty to preclude any form of territoriality to bound and bind the Amazon other than the one delimited by their national borders.

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, environmental awareness and conservationist concerns were gaining space in international politics, and the Amazon was progressively defined by its ecosystem, which was something to be preserved. The global salience of the environmental agenda would rise with the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm in 1972.Footnote 72 This agenda was incompatible with the territorialisation strategy that Amazonian states had for the region. This was particularly the case in Brazil, whose projects of national integration and colonisation of the Amazon region was based on enviromentally degrating economic activities.Footnote 73 Championed by Brazil, ecosystem-anchored regionalism would provide an answer for these states to preserve their territorialisation strategies in the Amazon.

In the 1970s, the postworld war wave of interstate regionalism was very much at its apex around the world, particularly in Latin America.Footnote 74 In this context, intergovernmental organisations were the main tool for achieving regional cooperation, and Brazilian diplomacy sought to stay well positioned in this growing patchwork of overlapping initiatives.Footnote 75 By the mid-1970s, the Amazon was a clear blind spot in that strategy, particularly given the emergence of the Community of Andean Nations, which included four of the biggest Amazon countries (Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia, and Peru) but not Brazil. Brazil's geopolitical concerns with the lack of coordination with northern neighbours and their shared particular concern with international pressure over their development plans for their slices of the Amazon are the main reason for the quick emergence of Amazon regionalism through the late 1970s.Footnote 76 These states’ common goal of preserving sovereignty over the Amazon would produce the ecosystem as a region in world politics. Between 1975 and 1978, Brazil would concomitantly sign bilateral cooperation agreements with other Amazon states and start negotiations for a multilateral treaty encompassing the entirety of countries whose Amazon ecosystems fell into its sovereignty.Footnote 77 The Amazon Cooperation Treaty (ACT) was signed in 1978 by all Amazon states: Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Peru, Suriname, and Venezuela.Footnote 78

Amazon regionalism was thus born as a form of defensive regionalism;Footnote 79 a way for these states to block external influence and retain their capacity to control which actors would be able to influence the governance of the ecosystem under their sovereignty. The treaty was about policy coordination but mostly about bounding the region, territorialising it according to their national borders, and retaining sovereign control over their shares of the ecosystem. Article 4 in ACT makes this point very clear:

The Contracting Parties declare that the exclusive use and utilization of natural resources within their respective territories is a right inherent in the sovereignty of each state and that the exercise of this right shall not be subject to any restrictions other than those arising from International Law.Footnote 80

The aim was for them to collectively control the boundaries of their ecosystem and act as the sole representatives of the region vis-à-vis the world. Safeguarding sovereign rights against international pressures would be the main function of the treaty in its first decade of existence.Footnote 81

By the late 1980s, the bounding force of Amazon regionalism had been put to the test. Environmental degradation of the Amazon, particularly in Brazil, was becoming more evident, increasing the conflictual territorialities within the Amazon.Footnote 82 More and more, indigenous populations started to have the territoriality of their world shattered by the incursion of miners and settlers from elsewhere in the countries.Footnote 83 The Amazon would be prominent in the worldwide rise of global networks of indigenous peoples, whose struggle centred on defending their territorial rights.Footnote 84 In Brazil, extractive communities that have lived in the rainforest for decades, such as rubber-tappers, also started to see their livelihoods threatened by growing activities such as logging and cattle raising.Footnote 85 The death of environmental activist Chico Mendes brought even greater international pressure on governments to take action to preserve not only the Amazon environment, but also its inhabitants, who were seen as part of the same ecosystem.Footnote 86

This growing pressure was faced with growing coordination among Amazon states. The coordination was primarily aimed at achieving collective action to preserve their joint role as the sole representatives and gatekeepers of the region. This strategy found resonance in the notions of sustainable development and ‘common but differentiated responsibilities’, with their growing relevance in the aftermath of the Brundtland Commission and in the preparations of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. The Amazon states would subscribe to the idea of being stewards of international demands for sustainable development and demand financial assistance from the interested international stakeholders. The joint Amazon declaration of 1989, the first signed by the chiefs of state from all ACT signatories since its creation, reflects this spirit. It manifested commitment to ‘the rational utilization of natural resources of the region’ but reaffirmed their ‘sovereign right to freely administrate those resources’.Footnote 87 More importantly, it claimed that the ‘developed countries’ concern with conservation of the Amazon environment needs to be translated to financial and technological cooperation’ and demanded ‘new flows of resources for environmental protection’.Footnote 88

Amazon cooperation would grow stronger in the years to follow. The Amazon Treaty was converted into a formal organisation (ACTO) in 2002, acquiring a permanent secretariat and strategic plans of action.Footnote 89 This created additional spaces for policy coordination among countries. Still, the ACTO is often seen as a very limited organisation.Footnote 90 The policy coordination it produces is very loose in its constraining effects over domestic governance. This would lead the ACTO to be considered ineffective in integrating the governance of the region.Footnote 91 However, assuming the organisation's lack of supranationalism and its limitation in spurring greater cross-boundary ties among non-state actors as a failure misreads its goal. Instead, I would argue the ACTO has been quite successful in its goal of coordinating the Amazon states’ efforts at preserving their national boundaries as the main sources of territorialisation of the Amazon.

In this sense, though not producing cross-boundary integration, the ACTO is central to the production of the Amazon as a region, binding and bounding its existence in world politics in important ways. Primarily, it bolstered the ability of Amazon states to act collectively to gatekeep external interest and funding, as well as their ability to retain the main representation of the ecosystem vis-à-vis external actors.Footnote 92 While being able to attract funding and action to itself, the ACTO still defers to member-states regarding the destination of its resources.Footnote 93 Additionally, its structure subordinates the presence of local non-state actors to the national state's control.Footnote 94 Therefore, it binds and bounds the Amazon region as a club of states that retain their position as the main stakeholders in the governance of the Amazon.

Of course, this is not to claim a homogenous interest across time in all states and all their internal agencies involved in the Amazon cooperation. Instead, what I claim is that Amazon regionalism – and the prominence of states in it – allows these states to retain greater control over which domestic and international actors can be included in the governance of the ecosystem and how. This has been crucial to render effective the efforts of several Amazon states to strengthen local and global participation in the governance of the ecosystem, but it also makes it very vulnerable to changes in domestic power struggles.Footnote 95

To make sense of this claim, I propose that we should not focus on the internal integration of the Amazon but instead on the manifestation of its bounding and binding effects in global governance. The idea is that the dynamics of binding and bounding discussed here should be fundamentally manifested in the coordination of Amazon states in environmental negotiations concerning the ecosystem. This section concludes by empirically examining these dynamics.

The ‘makings’ of the Amazon in environmental negotiations

I have argued that the production of the Amazon as a region in world politics has been intimately tied to the emergence of global concerns about it as a threatened ecosystem. Regional cooperation has been most effective at coordinating responses to global pressures and preserving the Amazon states’ centrality in the governance of the ecosystem. To probe this claim, I investigate the patterns of interactions among both state and non-state actors in environmental negotiations at United Nations forums that mention the Amazon. Using network analysis, I map these interactions through the reports of the Earth Negotiations Bulletin (ENB) produced by the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD). These reports describe the proceedings of each day of negotiation across 49 distinct negotiations from 1992 to the present moment, based on a standardised style guide that minimises biases from reporters.Footnote 96 This ensures that the interactions among actors can be easily identifiable. ENB reports can be seen as a reliable digital trace of diplomatic interactions and have already been used by previous scholarship on environmental politics.Footnote 97 Thus, this gives insights, albeit partial and limited, into interaction networks that could otherwise only be accessible through fieldworkFootnote 98 – a strategy not possible for past negotiations and something that has been severely limited by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The empirical strategy for mapping this network proceeded as follows: Negotiations were considered relevant for the analysis if they either mentioned the Amazon region as an object of debate or if an interacting part was named after the region, including IGOs, advocacy groups, and diplomatic coalitions. This allowed for mapping interactions about and on behalf of the Amazon by multiple states and an array of non-state actors. Instances of these interactions were identified by combining a simple protocol of text mining and systematic manual coding. The text analysis comprised three steps. First, I identified reports mentioning the word ‘Amazon’ within the ENB online repository (a total of 395) and extracted their content with a web scraping application in R statistic software. Second, these corpora were divided into paragraphs, and only paragraphs that contained the word Amazon were maintained, along with their meta-data. Third, an automated search extracted the names of the participants cited together in any given sentence of these paragraphs as an indication of potential interactions. These three steps ensured that all potential interactions in the corpus could be identified. This selection of potential interactions was then coded manually.

This final selection kept only the interactions fitting one of the following types: signalling of institutional cooperation, joint support for a negotiating position, joint opposition to a negotiating position, manifestation of praise, or neutral mentions. Indications of cooperation were coded from mentions of a cooperative initiative between two actors, such as the following: ‘the [ITTO] Secretariat outlined the completed pre-projects on the economic valuation of production forests and agroforestry system in the Peruvian Amazon and on assessing the feasibility of, and support for, a tropical timber promotion campaign.’Footnote 99 Joint support and opposition interactions were coded when reports listed countries as sharing a common position regarding a proposition, as in the following reactions to the Chair's summary of the second session of the UN Commission on Sustainable Development in 1994:

Brazil, Bolivia, Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador and Peru thought that the summary paragraph on forests did not reflect the fact that the CSD should be the central body for the discussion of all aspects of implementing Agenda 21 on this issue. … Others, including India, Greece on behalf of the EU, Malaysia, the US and Norway, supported the Chair's summary.Footnote 100

Mentions of praise were coded when laudatory words were used in reference to another actor, as when the president of a UK-based NGO said the Brazilian Amazon Fund was a ‘model of good governance and open participatory structure’.Footnote 101 Other mentions were coded from more neutral references such as when Brazil suggested including ACTO experience with Sustainable Forest Management indicators in a CBD document.Footnote 102

Each interaction can include one or more actors. The analysis spans from 1992, the first year available, up to 2018, the last year before the disruptions of the Bolsonaro administration. Table 1 shows the number of interactions of each type and the number of ties they produced for the entire period of analysis.

Table 1. Interactions and ties in environmental negotiations involving the Amazon.

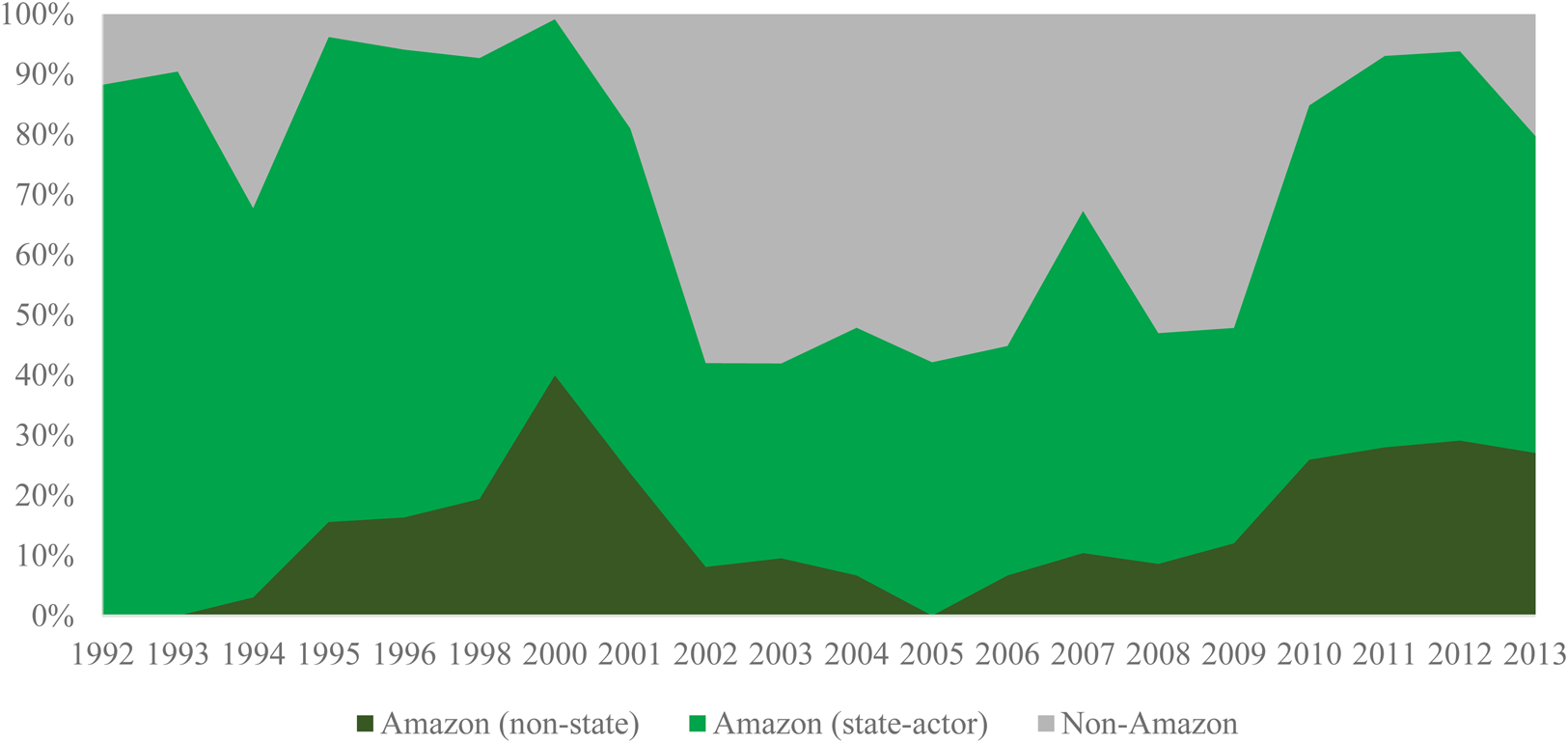

The interactions shown in Table 1 can be understood as a relational system, a structure that can be examined with the methodological tools of social network analysis. Figure 4 shows the network formed with all the interactions on behalf and about the Amazon at UN-level environmental negotiations from 1992 to 2018. Nodes whose names are in green are those considered to be Amazon actors. These include the eight Amazon states, the ACTO, informal groupings named after the region, local indigenous organisations, and other non-state actors based within the region. Table A1 in the supplementary material details the names of all the nodes. Ties reflect an interaction between a pair of actors, and the thickness of these ties reflects the volume of the interactions.

Figure 4. Network of interactions at UN-level environmental negotiations (1992–2018).

Note: Nodes in green are Amazon state and non-state actors. Nodes in grey are extra-regional actors. Size of nodes is proportional to the distribution of degree centrality. The thickness of ties reflects the number of interactions.

The most salient feature of the Figure 4 is the centrality and clustering of the Amazon states and the ACTO. These states concentrate most interactions with the rest of the network and are even more intensely connected among themselves. The thickness of the ties among these states reveals a greater volume of interactions compared with most other ties. The only other dense cluster of ties in the network is the one among other states, mostly from Global North, although their thinner ties reveal less frequent interactions. This cluster includes the Amazon group, which is how the coalition of Amazon countries is referred to in some ENB reports. I kept these groups as distinct from instances in which the Amazon states or ACTO were named individually to empirically capture whether these actors would interact cooperatively outside this coalition. This distinction shows that Amazon actors tend to coalesce in both circumstances, when negotiating individually and when appearing as a unified actor. It is also interesting that the Amazon group is in-between the cluster of Amazon states and that of other states, reflecting the joint action of this group when interacting with other states. This is a similar position to that of the ACTO, which is part of the cluster of interactions among the Amazon states and seems to bridge interactions with several other intergovernmental organisations.

The other Amazon actors are more sparsely distributed in the network. Most non-governmental organisations have only one tie. The main exception is the indigenous organisations, two of which stand out. One is the Coordinator of the Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon River Basin (COICA), an institution that represents indigenous groups from the entire region. Although peripheral to the overall network structure, COICA has interactions with multiple other actors, most of them being international governmental organisations. The second node that stands out is Amazon indigenous groups, which captures references to indigenous populations where no specific organisation is specified. It is interesting to note that these references are mostly used to describe interactions with organisations from civil society or with the Amazon states themselves, where the latter links the first to the overall network structure. In this sense, the Amazon states seem to gatekeep the interactions between indigenous groups and several other local actors from the Amazon with other actors in this network.

In this sense, the main cluster of Amazon states plus the ACTO seems to concentrate the interactions in the network, while keeping denser ties among themselves than with other actors. In other words, the interactions among most actors in these negotiations are mediated by this club of states with sovereignty over the Amazon ecosystem. This illustrates the coupled mechanisms of binding and bounding, through which regions influence world politics.

To grasp these in more detail, we can look at four network statistics. The first two metrics are the distribution of betweenness and degree centrality in the network. Betweenness centrality captures the frequency in which a node is in the shortest path between any two other nodes in a network, hence indicating a position of mediation or brokerage. Degree centrality reflects the number of ties possessed by an actor, its overall activity in the network. Actors with high scores in both measures may suggest particularly powerful brokers that link many actors and even many clusters.Footnote 103 Figure 5 shows the distributions of centrality across these two measures as a proportion of the highest score in the network. Here, Brazil has by far the highest scores in both measures, doubling that of almost all the other nodes. Also, combining high degree and betweenness are Colombia and the ACTO. Given the topography described above, this suggests that these nodes exert greater boundary control over the interactions between the inside and outside of the central cluster of the network. The node of Amazon indigenous groups presents an even higher betweenness centrality, reflecting its position between the cluster of Amazon states and a range of actors from civil society that solely interact with them in this network.

Figure 5. Distribution of betweenness and degree centrality (as proportion of maximum value).

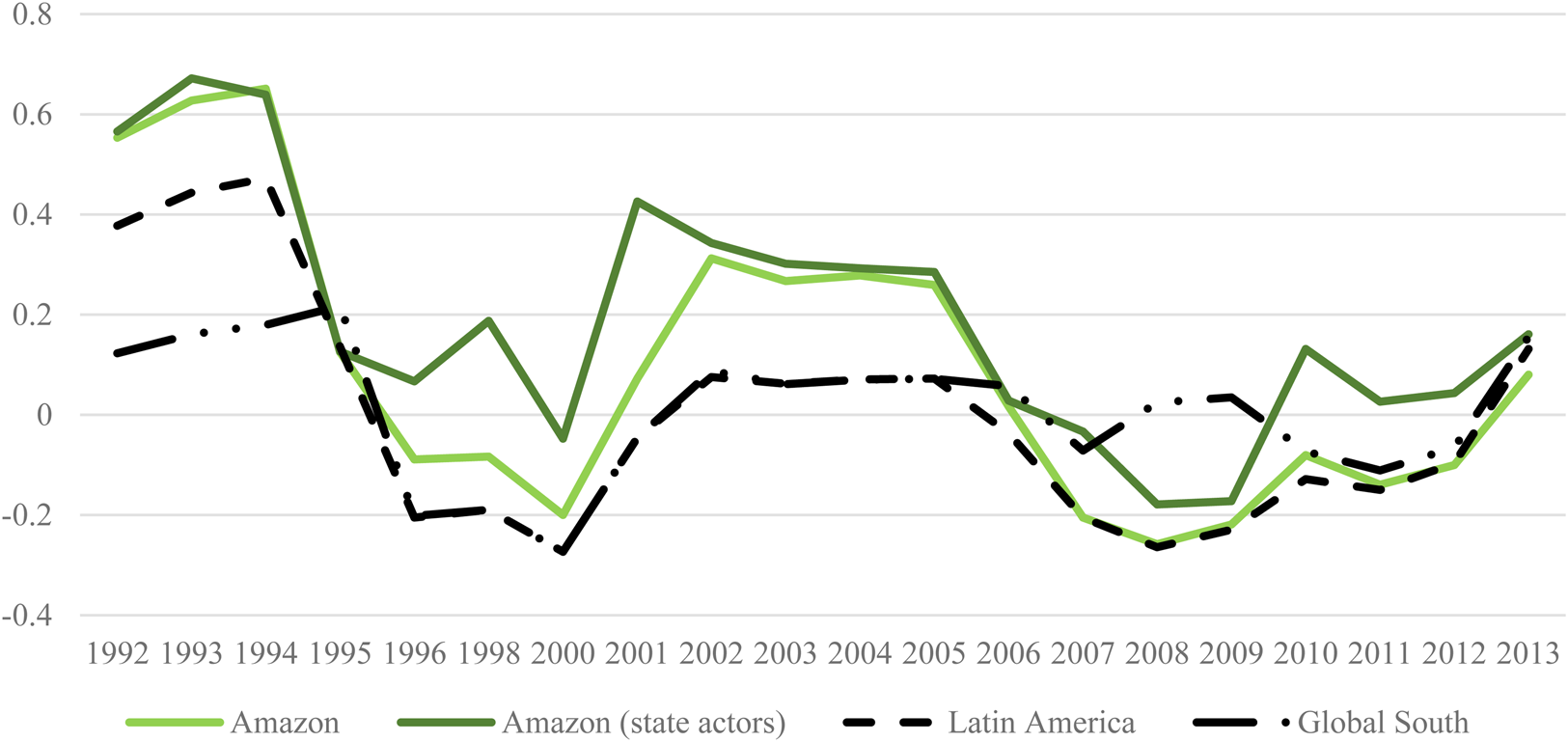

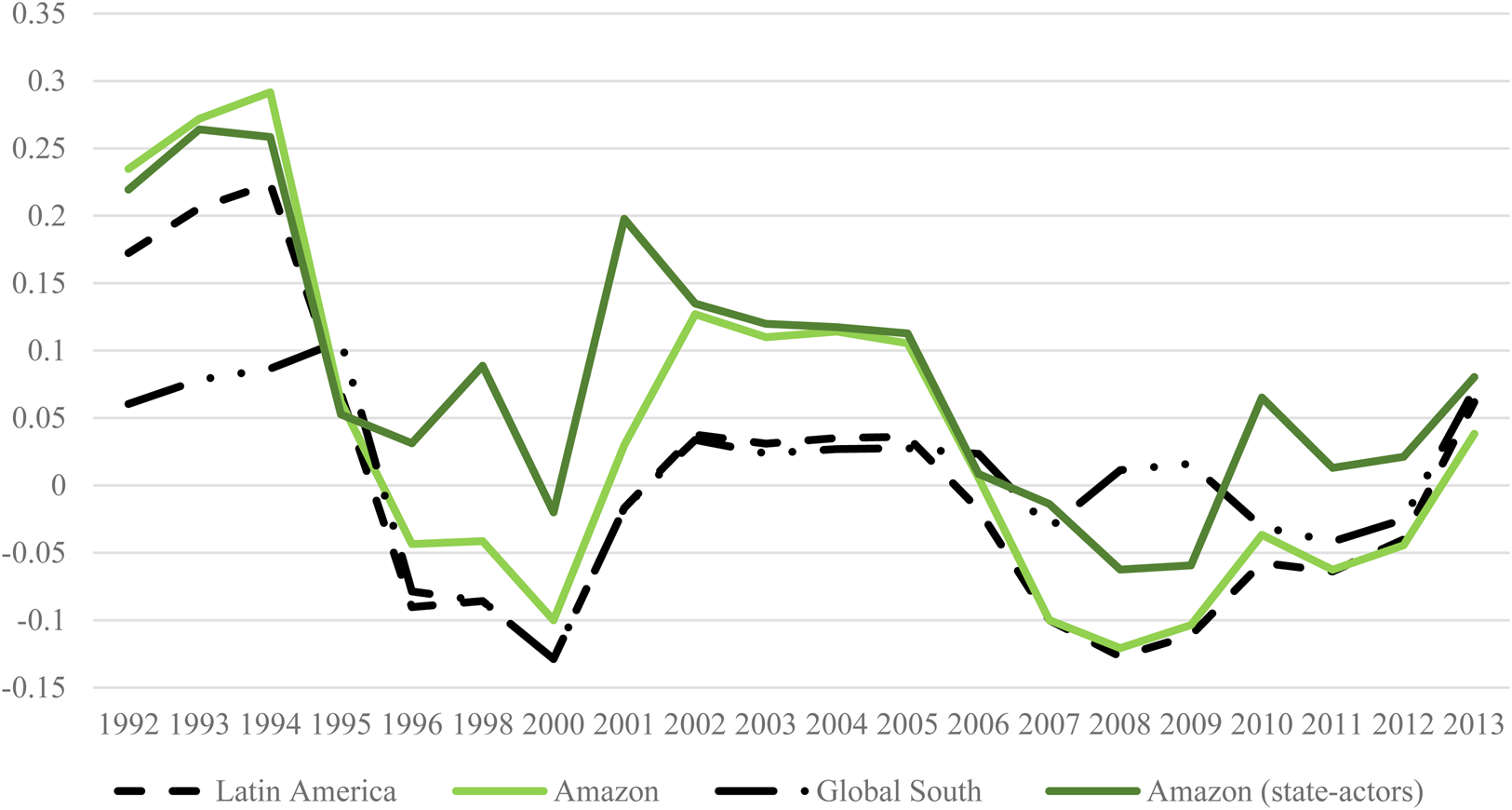

Two other metrics help in understanding the binding effects of the Amazon that produce it as a bounded entity in environmental negotiations. These measures allow for comparing the level of clustering of Amazon as a group to alternative groupings of which Amazon state could have been part. The first metric, called assortativity, measures the tendency of nodes to form ties with other nodes in their same group.Footnote 104 Positive values of assortativity indicate this tendency. Table 2 displays the assortativity of Amazon actors in general, and Amazon state actors (including the ACTO) in particular, in contrast with two other groupings: Latin America and Global South, to which Amazon actors are often associated with coalition-building in international environmental negotiations.Footnote 105 As the first row of Table 2 shows, assortativity is positive among Amazon actors as a whole and among Amazon states – and at greater levels than other divisions. These figures show that Amazon states tend to interact more among themselves than with actors of these other broader groups.

Table 2. Assortativity and modularity by categorical group.

A parallel metric of groupings within networks is modularity. Modularity calculates the probability of ties falling inside a partition of a network rather than at random.Footnote 106 The identification of clusters in a network structure often relies on algorithms that estimate a partition that maximises modularity.Footnote 107 Running two distinct modularity maximisation algorithms, all eight Amazon states and the ACTO are placed together in the same community, while the other Amazon non-state actors are spread in other clusters. Much like assortativity, modularity can indicate if a given group corresponds to a cluster in the network. The second row of Table 2 shows the positive values of modularity for Amazon actors, confirming its structural character as a delineated cluster. These results show that the probability of an Amazon actor having an interaction with another Amazon actor is higher than the one between Latin-American states or Global South countries – both of which are groupings with which the Amazon states often coalesce in environmental negotiations. More than a part of the traditional Latin-American or Global South coalitions, Amazon states worked as a group on their own.

Besides investigating this network as a whole, it is possible to assess its evolution over time by grouping ties into smaller time spans. The figures below show the same metrics discussed previously, here applied to five-year cuts of the network starting each year from 1992–6 to 2014–18. Figure 6 shows snapshots of these structures.Footnote 108 As with Figure 4, Amazon actors have their names in green and other actors have their names in dark grey. Prima facie, it suggests that Amazon states tend to remain the most central cluster across time, connecting other clusters and mediating interactions between IGOs and other states with Amazon non-state actors. More importantly, this is the case even as the network gets denser and includes a greater number of actors. As more actors engage in negotiations about Amazon, the Amazon states and the ACTO retain their brokerage roles reproducing the region through its binding and bounding effects.

Figure 6. Evolution of networks of interactions at UN-level environmental negotiations.

Note: Nodes in green are Amazon state and non-state actors. Nodes in grey are extra-regional actors. Size of nodes is proportional to the distribution of degree centrality. The thickness of ties reflects the number of interactions.

The main exceptions are the periods between 1996 and 2002, and 2006 and 2010. In both, we see a smaller number of Amazon states in the network. In the first case, this seems to be a product of a generally sparser network, reflecting a smaller number of mentions to Amazon in negotiations reported by the ENB. This follows a previous period of greater activity in the UNCED and at the UN Commission on Sustainable Development, in which Amazon states started already coordinating efforts globally and working jointly as discussed in the previous section and illustrated by the first network snapshot of Figure 6.

The other exception is also a product of fewer Amazon states being referred to in negotiations but in a very different context. One can see that the Amazon group acquires there a central position. This group was created as part of the UNFF negotiations on a non-legally binding instrument on forest governance.Footnote 109 Its emergence thus follows an increased articulation among Amazon states in global governance in negotiations with central relevance for preserving their sovereignty as the sole territoriality demarcating the governance of the region. It is thus a good illustration of the interweaving of binding and bounding mechanisms through brokerage dynamics. While clustering among Amazon states is less salient in the period, the emergence and centrality of the Amazon group suggest a period in which these states acted as one – as if the region itself acted.

Figure 7 shows the distribution of betweenness centrality scores across these twenty networks. There we can see the predominance of Amazon actors in general – and Amazon state actors in particular. The years in which the overall centrality of Amazon actors drops coincide with the periods when the sheer number of actors in the network surges, as one can see in Figure 6. Still, these figures are nevertheless remarkable considering that Amazon actors were always a minority among the nodes in the network.

Figure 7. Distribution of betweenness centrality by period.

The measures of clustering of the Amazon actors can also be analysed over time. Figures 8 and 9 show the measures of assortativity and modularity for four groupings where Amazon states could belong, as in Table 2. As Figure 8 illustrates, for most periods, Amazon actors in general and Amazon states in particular display a greater tendency to have ties among themselves than with other actors. Assortativity is positive for Amazon states in 16 out of 20 of the network snapshots. When non-state actors are included in the group, the assortativity is positive in 11 out of 20 periods. Figure 9 shows the results of modularity for the same groupings across time, indicating a very similar tendency. Amazon states are more likely to have ties among themselves than elsewhere in the network in 16 out of 20 periods, while the Amazon actors in general are also more likely to have ties among themselves in 11 out of 20 periods. The exceptions are exactly the periods previously discussed in which fewer Amazon states’ interventions were reported. While the first period, in the late 1990s, refers to a period of less salience of the region in the negotiations as a whole, the second period in the late 2000s refers to the consolidation of Amazon bounding and binding, by acting as one ‘Amazon Group’ in forest negotiations.

Figure 8. Assortativity by categorical grouping by period.

Figure 9. Modularity by categorical grouping by period.

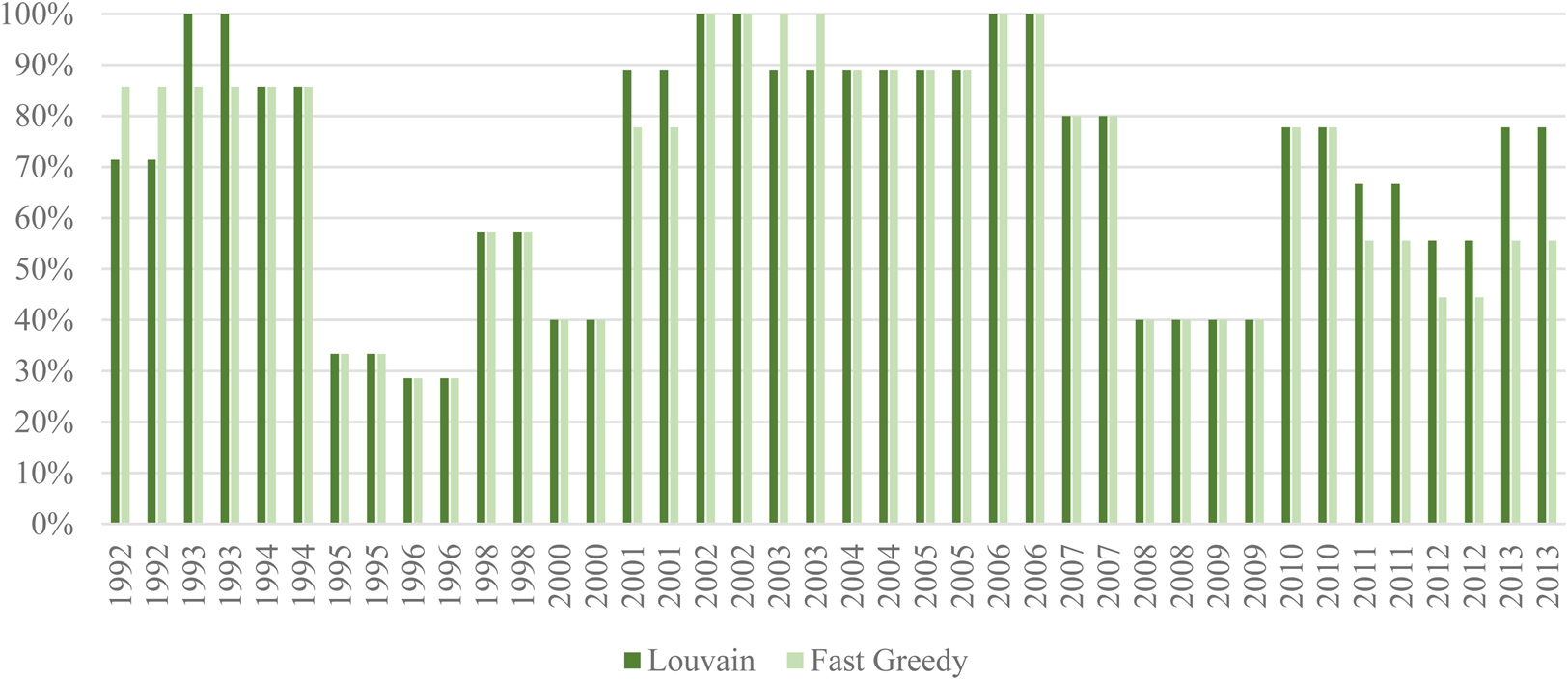

These results suggest that the group of Amazon states, including the ACTO, have worked as a defined cluster in environmental negotiations for a considerable part of the period under analysis, corroborating what was illustrated in Figure 4. Furthermore, this temporal disaggregation calls attention to the greater consistency of the Amazon state actors – compared with non-state actors and other groupings they could be part of – as a cohesive group in environmental negotiations. To further gauge this finding, Figure 10 shows the proportion of Amazon state actors that have been part of the same cluster when measured by two distinct modularity maximisation algorithms. For most periods, apart from the exceptions discussed, the majority of states and the ACTO fell within the same cluster based on the partitions algorithmically produced.

Figure 10. Percentage of Amazon state actors within the same algorithmically detected cluster by period.

Overall, the analysis of this network of interactions in the environmental negotiations involving the Amazon helps illustrate the effects of the region on world politics. The binding of the Amazon's adjacent states allows for defining and preserving the boundaries of the region in global governance. The region is constructed through the coordination of its states in negotiations against pressures from non-local actors and the intermediation of interactions with other non-state actors in the Amazon. The Amazon states and ACTO seem to work successfully as a collective actor in these negotiations. The ACTO, the Amazon group, and major states like Brazil control interactions with other actors on behalf of the Amazon states as a whole. At the same time, their entire cluster lies in-between distinct segments of the network, particularly between local non-state actors in the Amazon and other states and intergovernmental organisations. Amazon regionalism affects environmental negotiations through the binding of its states, allowing them to preserve their club status as main stakeholders in the governance of the region, and through their boundary control of the interactions between the inside and outside of its clusters, as well as across segments in the network.

Conclusion

The current article has proposed a processual–relational view of the making and makings of regions in world politics. I argued that regions are produced and affect the political world by sustaining territorial boundaries that do not fit the exact borders of states and that retain social interactions that are denser inside these boundaries than outside. Regions are both networks and territories; they are networked territorialities.

This processual–relational view of regions allows us to go beyond the traditional views of regionalisation, which have centred on cross-border flows, as well as those of regionalism, which have focused on identity formation and institution building. Regions can produce network territorialities that effectively bound and bind social relations, even if their institutions are weak, shared identities are thin, and supranational integration is timid. This is the case in the making and makings of the Amazon as a region in world politics.

The Amazon has emerged as a response of adjacent states to growing global concerns with the ecosystem comprised of the river basin and rainforest under its name. Its central corporate actor, the ACTO, was openly created as a means for states with sovereignty over the Amazon to jointly address international pressures for environmental stewardship of the ecosystem while retaining autonomy to shape this process. As a result, the main success of Amazon regionalism has been to reproduce the centrality of Amazon state actors in the global governance of the ecosystem as both the main representatives of the region to the world and gatekeepers of flows from the world to the region. That is not to say that the interests within and across states over Amazon governance have been homogenous or static through time. Amazon states promoted the inclusion of indigenous communities and other non-state local voices in global governance and incentivised cooperation with global actors.Footnote 110 Yet their very position as the brokers of these relations is the main boundary that Amazon regionalism produces. I have unpacked this claim by analysing network interactions among state and non-state actors at UN-level environmental negotiations involving the Amazon. The analysis shows the centrality of Amazon state actors in these negotiations, their tendency to form denser relations among themselves than with other actors, and their position as intermediates between other interactions in the network.

I would further suggest that this pattern may not be a feature of the Amazon alone but of ecosystem-based regionalism more broadly. Cross-border ecosystems, such as the one encompassing the Amazon river basin and rainforest, challenge the territoriality of states and may pull them together into a state of cooperation, something that deserves greater attention.Footnote 111 On the one hand, they are often areas where state presence is sparse and borders are porous. On the other hand, global concerns over these ecosystems put them forth as cohesive entities with natural scientific boundaries that cut across those of states. In the Amazon case, this conflicting duality allows us to understand its regionalism, which has been more successful on preserving sovereignty than on producing integration. The ways in which states respond to the global production cross-border ecosystems territorialities – whether they double-down on their sovereignty rights or who they include and exclude in the process – is an avenue for future research that may benefit from the framework proposed here.

In this sense, the processual–relational perspective presented in the current article expands our understanding of regions. It allows us to go beyond the traditional views of regionalism and regionalisation centred on institutional and socioeconomic integration, along with their often-Eurocentric benchmarks. In turn, it shifts our attention towards studying the making of regions through their effects on world politics: the patterns of relations it produces and the boundaries it raises. Furthermore, it offers a methodology to empirically study these relations in process. Therefore, it opens the way for studying consequential aspects in the making and makings of regions that could have otherwise gone unnoticed, as I hope the case of the Amazon in ecosystemic politics has illustrated.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers, the editor Matthew Paterson, and the RIS editorial team for their very constructive engagement with this article. I'm also very grateful for the comments and advice received from Elana Wilson Rowe, Cristiana Maglia, Kristin Fjæsted, Paul Beaumont, Jaakko Heiskanen, Ayşe Zarakol, Adam B. Lerner, Marie Prum, as well as the participants of the panel ‘Rethinking Complex Theories and Network Analysis’ at ISA 2021. This publication was funded by a grant from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement No. 803335, ‘The Lorax Project: Understanding Ecosystemic Politics’).

Supplementary material

To view the online supplementary material, please visit: {https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210522000249}