Travelling by ferry across the bay of Cienfuegos, I had the sense of being in a strangely global and historical place. I was approaching a once colonial city, later the epicentre of the Cuban Revolution's visions for national development. To the west towered the distillation columns of a Soviet-built oil refinery, now funded by Venezuela, and the chimneys of a Czechoslovak electricity plant. To the south-east lay the remains of a never-completed Soviet nuclear submarine base. Behind me, where the bay met the sea, rose a mighty concrete structure that in the 1980s was due to become the Revolution's greatest achievement. This, the containment building of Cuba's first nuclear reactor, now appeared a hollow shell. As a place, Cienfuegos seemed the product of complex socio-ecological relations that at one time or another had converged in this exact location.

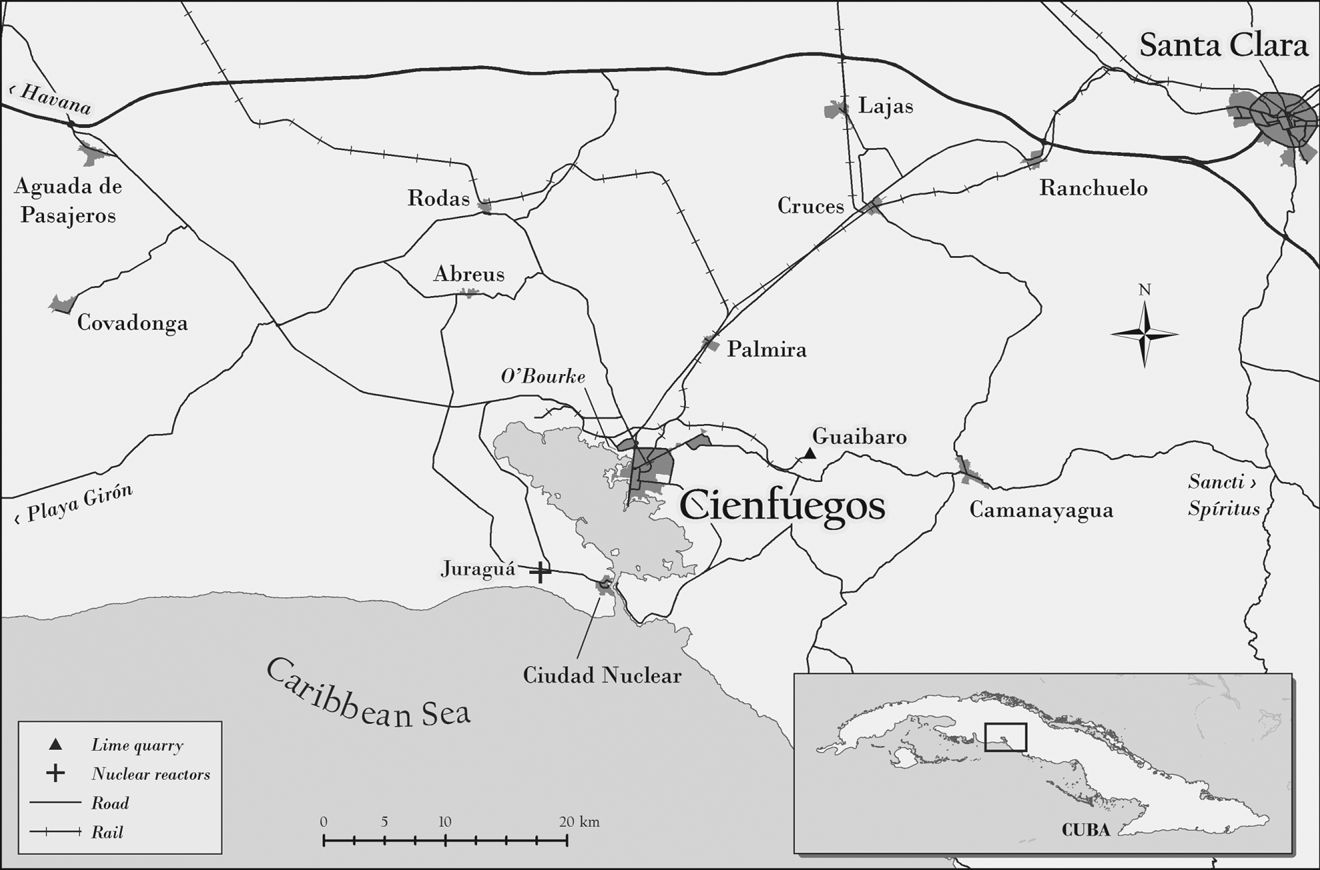

The revolutionary government turned its attention to Cienfuegos in the 1960s in order to develop the country's industrial capacity away from the Cuban capital. The Havana Declarations of 1960 and 1962 asserted Cuba's independence from the neo-colonial world order, but the injustices of dependency could be remedied only by industrialising and urbanising the deprived regions.Footnote 1 As architectural historian Roberto Segre argues, the revolutionary leadership chose to neglect Havana and, instead, to create a homogenous urban fabric across the island.Footnote 2 In Fidel Castro's words, there would be ‘a minimum of urbanism and a maximum of ruralism’ when the Revolution transformed the country in its entirety.Footnote 3 On Cuba's southern shores (Map 1), Cienfuegos became a key node in an international network that would allow the country to develop under historically fair conditions.

Map 1. Cienfuegos, Cuba

Alongside Cuba's spatial transformation, the revolutionary government developed a distinct mode of energy infrastructure in Cienfuegos. Echoing Lenin's maxim that ‘Communism is equal to Soviet power plus electrification of the whole country’,Footnote 4 it invested heavily in a unified national electricity system, powered in the first instance by Soviet fuel oil. In the Cuban Marxist–Leninist reading of history, oil-based electricity was a material precondition for the nation's transition to communism. As Cuba reached higher levels of social development, however, oil would give way to nuclear energy, epitomising the Revolution's ability to transform the techno-material base of the national economy. While Cuba established a nuclear programme in 1976, starting work on a first reactor in 1983, nuclear development at the same time took on a new urban form across the bay of Cienfuegos in Ciudad Nuclear (Nuclear City).

This article examines the place of Cienfuegos and Ciudad Nuclear in the ideational world of the revolutionary leadership and explores how the city developed through industrial investments as part of the international socialist political economy. I draw on geographer Doreen Massey's work to argue that cities should be understood relationally, as places that form through actions and processes extending beyond them in space and time.Footnote 5 Cienfuegos then serves as a prism for understanding the socio-political significance of urban change and energy development as a single simultaneous process in the Cuban Cold War period. The focus on Cienfuegos contributes to an understanding of the Cold War, where Cuba's national history is seen neither as ‘an extension of empire’ nor through the primary lens of bipolar conflict.Footnote 6 Cienfuegos also prompts us to look beyond the region's major cities, the significance of which is frequently overemphasised in urban and Latin American studies in view of their history as symbols of European power and dominance.Footnote 7 The city further brings alternative circulations of knowledge to light in social science research on energy, a field that has mainly emerged from research on a small set of countries in Western Europe and North America.Footnote 8 Cuba's joint urban and energy development demonstrates how leaders and planners attempted to enact social change through a radical spatio-infrastructural transformation, aiming not only to break with the colonial past, but also to bring nuclear modernity to the Caribbean. The effects of this transformation today raise questions about the links between urban form, energy infrastructure and political economy in Cuba's Cold War and after.

From Urban Dependency to Urban Revolution

In the eighteenth century, Havana developed into Cuba's all-dominating urban centre. The capital city constituted a key node in the Spanish imperial economy. In particular, control over Havana gave access to the transatlantic route along the westerlies, allowing ships to sail from the Americas to Europe.Footnote 9 When Spain ceded Cuba to the United States in 1898, Havana retained its status as an outward-looking colonial hub. Beyond its harbour, the city provided spaces for political and economic administration over resource extraction in the sugar-producing hinterlands. Within Cuba, the seasonal rhythm of the sugar industry meant that work was abundant in the hinterlands during the labour-intense zafra (harvest). The dreaded period between harvests, usually lasting from June to December, was known as the tiempo muerto (dead period) and, to escape it, rural dwellers migrated to Havana in search of jobs.Footnote 10

To the revolutionary leadership, the tiempo muerto, urbanisation and Havana's primacy resulted from Cuba's incorporation into the colonial world economy. ‘Do you think that if we had had the possibility of starting to plan the entirety of this country, we would have overindulged ourselves with a city as big as Havana?’, Fidel Castro notably asked a crowd in Oriente Province in 1966. ‘Those enormous urban concentrations are anti-economic’, he argued; ‘they are unaffordable; they are enormous human concentrations’.Footnote 11 In the metropoles, whether in Europe or North America, urbanisation had been the product of industrialisation. In Latin America and the Caribbean, by contrast, urbanisation resulted from colonial resource extraction serving the metropole's industrial development. Without domestic industrialisation, Havana was draining Cuba's rural areas of resources while large parts of the urban population remained in poverty without employment.Footnote 12 Among Latin American dependency theorists more widely, this analysis gave rise to notions of ‘urban inflation’ and ‘overurbanisation’ whereby the ‘surplus of unproductive population’ was destined to live in slums and work in the informal economy.Footnote 13

Fidel Castro's rebel army entered Havana in January 1959, and his new government soon set up a Department of Physical Planning to oversee Cuba's urban and regional development. According to its first director, Felipe Préstamo, the intention at this point was to focus on regions away from Havana.Footnote 14 On the one hand, the government sought to reduce the primacy of the capital in terms of economic activity and population growth. By turning away from it, the dependency relation between Havana and its hinterlands would be broken, allowing the deprived regions to develop. Addressing the International Organisation of Journalists in 1971, Carlos Rafael Rodríguez, one of Cuba's most senior government and Communist Party officials, argued that Havana had been ‘the developed capital of an underdeveloped country’. By the early 1970s, however, the government's neglect of the capital, counteracting the legacy of colonialism, was showing results: ‘That Havana no longer exists and will never exist again. Our capital today is the stagnant capital of a country in development.’Footnote 15 Indeed, the government even attempted to ‘ruralise’ Havana. In the late 1960s, Fidel Castro urged the habanero population to farm the Cordón de La Habana, a green belt around the capital, while the government created large green urban spaces in Parque Lenin, the National Botanical Gardens and the National Zoo, blurring the boundary between city and countryside. Fidel also exhorted the urban populations to work in the cane fields to achieve a record ‘10-Million Tonne Zafra’ in 1970, which, despite great efforts, failed to reach its target.Footnote 16 As Josef Gugler later concluded, the government's intention to counteract the urban growth of Havana reflected the view that it ‘represented the evils of old society’.Footnote 17

On the other hand, the government would create an integrated network of larger and smaller urban areas, creating an evenly urbanised fabric across Cuba. Urban centres would be linked in terms of economic planning and coordination, political representation, cultural norms and, crucially, nation-spanning infrastructure. Paul Susman argues that the goal of ‘urbanising the countryside’ meant that the state would provide the population with services and other use values ‘consonant with the social goals of improved service provision and enhanced equality’.Footnote 18 In urban areas, Cubans would have access to centralised electricity and water supplies, sewage treatment and telephone lines, hospitals and schools. While these were aspects of revolutionary development that Fidel Castro had identified in his manifesto, the Moncada Programme, he frequently reiterated that only national infrastructure and urbanisation of the country's interior could resolve the problems facing Havana, breaking the spatiality of dependent urbanisation.Footnote 19

Infrastructurally, the construction of the state rationing system distinguished Cuba's socialist urbanisation process from those in other countries. The government devised the rationing system in 1962 to ensure distributional equality. Each household received a ration card (libreta) and was entitled to a basket of foodstuffs and consumer goods to be collected from an integrated system of ration shops (bodegas). As infrastructural spaces for centralised redistribution, the bodegas constituted moments not only in the production of urban space but also in the nationally-integrated socialist state. With urban infrastructures, the state extended its power to logistically implement political decisions, aiming to transform living conditions throughout the country.Footnote 20 As Sunila Kale has shown in the case of electrification in independent India, electricity – on a par with the bodega – was ‘both object of and mechanism for’ the formation of the socialist state in that it simultaneously symbolised and enabled socialist urban practice.Footnote 21 Hardly by accident, the Cuban census definition of urban areas came to be based as much on population density as on the accessibility of urban infrastructures – socio-technically integrating and coordinating the socialist state.Footnote 22

From the government's point of view, the urban restructuring of Cuba would accompany a transformation of the nation's economic structure. After the Revolution, urbanisation would be coincident with industrialisation. The territorial extension of networked electricity infrastructure was essential to this task, as we shall see, and the effects of industrialisation would be as much spatial as socio-economic. When the state opened factories and educated the workforce, the nation's productive forces would develop, and workers would cluster in urban areas. Factories would also generate work for deprived urban populations. In the countryside, Fidel Castro urged small-scale farmers to move towards ‘superior forms of production’ – shorthand for collectivisation and mechanisation.Footnote 23 Entering successively larger social units, pooling mechanised resources, peasants would become agricultural workers. Ultimately, the peasantry – regarded as an archaic social class from ‘antes’, the epoch before the Revolution – would wither away as the rural population became proletarians working for the state and, hence, themselves as a national collective. At the same time, peasants would live in successively denser, more urban areas, moving from chozas and bohíos (huts and shacks) to modern, infrastructurally-integrated housing.Footnote 24

To this end, two principal actions were taken. First, the government nationalised all urban land, passing the Urban Reform Law in 1960. Nationalisation would allow the state to plan urban land-use rationally instead of relying on the haphazard law of value (i.e. market forces) for this historically essential task.Footnote 25 At the same time, the Urban Reform Law would reduce class-based urban differentiation, decreeing that one nuclear family could own only one property and putting a cap on rents.Footnote 26 Second, the government gathered data to draw up plans for cities away from Havana. Notably, they delegated to the Department of Physical Planning the preparation of development plans for seven of Cuba's secondary cities. From east to west these were: Santiago de Cuba, Holguín, Camagüey, Santa Clara, Cienfuegos, Matanzas and Pinar del Río.Footnote 27

Susman argues that the new regional focus was successful in as much as migration to Havana slowed during the 1960s.Footnote 28 Susan Eckstein also confirms this fact, noting that Havana had the lowest growth rate of any Cuban city in terms of population in the late 1960s, even though the growth rate had already started to decline in the decade prior.Footnote 29 With restricted economic resources, however, it proved difficult to replicate in other parts of the country the infrastructural and industrial development that existed in the capital. ‘[T]he legacy of an “over-urbanized” past continued to haunt the new regime’, Susman suggests.Footnote 30 Though it had eradicated class exploitation, Fidel Castro argued, the Revolution still suffered from the legacy of dependent urbanisation:

If you analyse it, there is a very unequal distribution of resources in the nation, because with man's exploitation of man having disappeared or being in the process of totally disappearing in the sense of existing proprietary classes and dispossessed classes, we find ourselves with a sub-product of capitalist exploitation, which is the exploitation of the countryside by the city.Footnote 31

In 1969, as a result, Fidel Castro announced that his government would focus most of its attention on three major regions with pre-existing infrastructure.Footnote 32 New industrialisation projects would be allocated to the provinces of Havana, Oriente and Las Villas. Cienfuegos was the regional centre in Las Villas.

Industrialisation in Cienfuegos

Despite Havana's primacy, Cienfuegos had developed into a regional economic centre over the past century. The city was established by a group of French émigrés from Louisiana in 1819 on the site of a former Taíno settlement. Following the Haitian Revolution of 1791, the Caribbean saw a wave of white migration from the formerly French colony east of Cuba. Louis Pérez Jr estimates that up to 30,000 French settlers arrived in Cuba in the 1790s. Haiti (then Saint Domingue) had been the world's leading sugar colony for much of the eighteenth century, so the French migrants brought with them capital and experience in sugar and coffee farming. When Napoleon sold Louisiana to the United States in 1803 a second wave of French migrants, in turn, set sail for Cuba. At this time, the Cuban sugar industry was expanding fast, thriving in the calcareous clay soils of Las Villas in particular.Footnote 33

Cienfuegos, sited as it was by a deep-water bay, provided a protected space for sugar shipments into the Caribbean Sea. When Las Villas’ largest town, Santa Clara, was connected to Cienfuegos by rail in 1850, Cienfuegos turned into a regional hub in the colonial export economy.Footnote 34 The urban form of Cienfuegos still reflects its historical role in the colonial political economy: the harbour constitutes the city's western perimeter, and the city pivots around a central plaza, the Parque José Martí (prior to 1902, the Plaza de Armas), with a cathedral dedicated to the Virgin Mary and the former offices of the colonial ayuntamiento (city council) and merchant corporations (Figure 1). A pedestrian walkway, the Paseo de Prado, extends north to south, forming a spine in a perfect orthogonal city grid. When the town centre was nominated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2005, the application file argued that ‘[t]he city's elegant and perfect neo-classical design, with the shape of a chessboard which extends along its urban perimeter, constitutes an exceptional exponent of the Cuban and the Caribbean 19th Century’.Footnote 35

Figure 1. Parque José Martí, Cienfuegos

In the 1960s, Cienfuegos retained its role as a regional economic centre. Initially, the revolutionary government had attempted to diversify the national economy, identifying sugar monoculture as the source of Cuban underdevelopment. A return to sugar, however, provided an immediate source of export revenue for the financially-strained government.Footnote 36 To blame a crop for the country's underdevelopment was also from a Marxist point of view to fetishise it, attributing agency to a thing rather than to the social relations it embodied. Before long, the harbour in Cienfuegos again constituted an essential outward-looking node in a global network revolving around cane sugar. But now a radically different set of social relations were seen to meet in this node, facilitating regional industrialisation and urbanisation. Cuban sugar shipments were no longer destined for Spain or the United States but for the Soviet Union and the member states of the Council of Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA).Footnote 37

The Cuban government struck its first trade deal with the Soviet Union in February 1960, including 900,000 tonnes of oil, which were estimated to save Cuba US$ 24 million in one year. Facing US discontent, the Cuban government argued that it was its right as a sovereign nation to trade with whomever they liked, stressing that even US-aligned Brazil was trading with the Soviet Union.Footnote 38 Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev was pursuing an export-oriented strategy at this time, making use of the Soviet Union's vast oil and gas resources to increase Soviet influence in Asia, Africa and Latin America. While approaching Cuba, the Soviets also offered generous trade deals to a range of countries in the Third World, including Ceylon, India, Ghana, Argentina and Brazil.Footnote 39

Cuban–Soviet commerce was established as a countertrade of oil and consumer goods for sugar. Both parties argued that this agreement undermined the ‘unequal exchange’ relations that otherwise existed between developed and underdeveloped nations in the capitalist world economy. Unequal exchange entailed international wage differences allowing industrialised countries to import a surplus of ‘value’, representing labour time embodied in traded commodities. While this surplus enhanced their development, agrarian nations were drained of value, which perpetuated their underdevelopment.Footnote 40 In the interest of advancing socialism globally, Cuba and the Soviet Union would break this unjust market logic, establishing equal-exchange relations through politically-defined terms of trade. Symptomatically, the first major development in Cienfuegos after the Revolution was a new harbour terminal, where raw sugar could be loaded in bulk to facilitate trade with the socialist bloc. The ‘Tricontinental’ bulk sugar terminal opened in 1967 in an area known as O'Bourke, northwest of Cienfuegos’ historical centre. The terminal's name celebrated the Tricontinental conference that was held in Havana the year before and posited the Cuban Revolution as a model for national liberation and development across Asia, Africa and Latin America.Footnote 41

The revolutionary government increasingly identified sugar as a vehicle for industrialisation of the agrarian economy. Unusually for a crop, sugarcane lends itself well to centralised production. Production requires a large mill (aptly known as a ‘central’ in Spanish) where cane stalks are crushed quickly to avoid fermentation.Footnote 42 In Cuba, Roberto Segre argues, the centrales were ‘true “factories” situated in rural areas’.Footnote 43 Around them, company towns known as bateyes provided spaces for business management and worker accommodation. Thus, the centrales – carrying urban form through their bateyes – were a means to overcome the contradiction between city and countryside.

While increasing the country's export capacity, the ‘Tricontinental’ was also key to the mechanisation of the sugar sector. In 1978, Fidel Castro inaugurated a similar terminal in Las Tunas Province and explained that the ‘Tricontinental’ had served the Cuban people in two ways. On the one hand, it had saved the country hard currency as bulk loading removed the need for sugar sacks, which had to be imported from abroad. Over the past decade, more than 10 million tonnes of sugar had been loaded in Cienfuegos; Fidel Castro estimated that this equalled around 50 million unspent pesos in hard currency on sack purchases.Footnote 44 On the other hand, the mechanisation of sugar loading had saved Cuban workers hundreds of thousands of hours of hard labour. Sugar sacks had to be carried, but bulk loading was automatic. In a capitalist society, Fidel argued, mechanisation would have taken labour time away from the worker, the machine competing with the worker for labour. But in socialist Cuba, the machines in the ‘Tricontinental’ had instead liberated Cuban harbour workers from hard labour as the machines were put to use in the workers’ own interest. ‘That is what socialism entails’, Fidel explained; ‘that when a technology is introduced it is not to enslave the worker, it is not to exploit the worker, it is not to make the worker redundant, but to help him. And so, the technology liberates thousands of our harbour workers from that hard labour.’Footnote 45 Indeed, in the ideational world of the revolutionary leadership, more advanced productive forces generated ‘development’ by freeing the Cuban population from the need to work through mechanisation and automation.

Still, the ‘Tricontinental’ was only one of many industrial facilities that opened in and around Cienfuegos between the late 1960s and the late 1980s. While the colonial economy had converged on Havana, Cienfuegos and southern Las Villas were now at the centre of the revolutionary economy. Two features characterised the new investments. First, several facilities increased the economy's dependence on sugarcane. A torula factory in Covadonga and a fertiliser plant in O'Bourke provide telling examples. Covadonga is a batey approximately 50 km west of Cienfuegos; torula is a protein-rich yeast that would be used as feed in the chicken runs around Cienfuegos. The torula factory opened in 1977 and, at its inauguration, Fidel Castro reported that the plant would employ 111 workers and produce 40 tonnes of yeast per day.Footnote 46 They had located the factory at the site of a large central, the ‘Antonio Sánchez’. To grow torula, workers would allow bacteria to ferment cane syrup (miel) deriving from the mill. Production also required water, ammonium phosphate and urea, the two latter products deriving from the fertiliser plant in O'Bourke, which was of British origin.Footnote 47 In a chronicle of Cienfuegos’ industrial history, the Cuban media outlet Radio Rebelde relates how the fertiliser plant discharged ‘yellow smoke into the air’ for the first time in 1974.Footnote 48 Before long, however, the machinery broke down. Fidel asserted that ‘all the defects and … all the botched jobs [chapucerías] of the English in that plant’ were to blame.Footnote 49 Production resumed only in 1978, and by then, both the torula and the fertiliser plant were tied into an economy that overwhelmingly relied on sugar exports. Usefully, torula was a domestic source of edible proteins via poultry farming, but it relied on a continuous supply of cane syrup, thereby increasing Cuba's reliance on sugar monoculture.

Second, the new industries strengthened Cuba's relations with the CMEA. As exemplified in the fertiliser case, many factories were imported from abroad to establish domestic industrial capacity. In 1984, the Cuban leader noted that ‘52 industrial developments [obras] … such as sand washers, stone crushers, tile and concrete block factories, electricity substations’ had been assembled in Cienfuegos Province since the Revolution.Footnote 50 Radio Rebelde recorded that these ranged from a dairy plant in Cumanayagua and the torula plant in Covadonga to facilities for wheat milling, mineral-water bottling and floor-tile production.Footnote 51 Most of the industrial units came from fellow socialist countries. One of the largest of these factories – the ‘Carlos Marx’ – would produce cement. Situated by a large limestone formation in Guaibaro, just outside Cienfuegos, the ‘Carlos Marx’ was imported from the German Democratic Republic and, to this end, its government reportedly provided Cuba with a 60-million-peso credit, to be repaid over ten years at 2 per cent interest. Cuba had to start repaying the credit as soon as the first of three production lines became active.Footnote 52 The cement would primarily be used for housing construction in Cuba to meet the demand for urban accommodation.Footnote 53

East German leader Erich Honecker visited Cienfuegos for the inauguration of the ‘Carlos Marx’ cement factory, during which Fidel Castro stressed how favourable a deal the factory was for the Cuban population: ‘See for yourselves what magnificent terms of credit, what magnificent financial conditions for building this factory.’Footnote 54 If Cuba had imported the plant from a capitalist country, as in the case of the fertiliser plant, it would have suffered from unequal exchange. In the revolutionary understanding of international political economy, Cuba no longer had to suffer from unequal exchange when it integrated its economy with the CMEA countries. According to Fidel, trade on preferable terms with already industrialised countries in the socialist bloc, such as Honecker's East Germany, allowed Cuba to develop its economy under historically fair conditions: ‘The development of these relations gives more solidity to our economy, it makes it less dependent on the Western markets, on the highs and lows and on the crises of this market; it makes it much less dependent on the unequal exchange that we have with the capitalist world.’Footnote 55 The Revolution therefore made Cuba an exceptional country in Latin America, having escaped the yoke of unequal exchange. The ‘Carlos Marx’ cement factory in Cienfuegos testified to this historical feat.

Industrialisation also brought with it urban change. Fidel Castro argued that construction workers played a crucial role in Cuba's transformation as ‘they have transformed the physiognomy of the country’.Footnote 56 Alongside Cienfuegos’ factories, construction workers were building aqueducts and sewers; they were putting up houses and shops, libraries, hospitals and schools. Urban change was most clearly to be seen in the regional cities. Many of these had seemed like small villages (aldeas) before the Revolution, Fidel explained. To speak of construction at that time was ‘to speak about the fifth wheel of the car’ (i.e. an optional extra). The politicians of the pre-revolutionary era had invested in a few small construction works during the tiempo muerto, when the people begged them for employment. But now, with the triumph of the Revolution, and ‘the necessity to develop all the land’, the country had finally established a modern construction industry with thousands of construction workers.Footnote 57 Indeed, in the mid-1980s, the growth of Cienfuegos was ‘a reflection of the Revolution in the entire country’, generating development away from the parasitical capital. And yet, while Cienfuegos could pride itself on its great industrial development, there were still many things that Cienfuegos lacked in comparison to other cities. The pre-revolutionary past made itself felt as capitalism and colonialism had left ‘a situation of great inequality, not only social inequality, but inequality between regions’.Footnote 58

The urbanisation process was also visible in the statistical yearbooks. According to the Cuban censuses of 1970, 1981 and 2002, the proportion of urban dwellers in Cienfuegos Province increased from 27.2 to 31.5 to 35.6 per cent between censuses.Footnote 59 Arianna Rodríguez García, too, concludes from Cuban demographic data that the provincial population living in urban settlements of more than 200 inhabitants increased from 8.85 to 32.3 per cent between 1981 and 2002.Footnote 60 In Cuba overall, the urban population grew only marginally from 1960 to 1970 – from 58.4 to 60.3 per cent – but then increased markedly, with 68.1 per cent estimated to live in urban areas in 1980 and 73.4 per cent in 1990.Footnote 61

The Nuclear Revolution

In the 1980s, Cienfuegos was the scene of the largest industrial project the country had witnessed thus far: the construction of a nuclear power plant in Juraguá at the mouth of Cienfuegos bay. Framed as ‘La Obra del Siglo’ (‘The Project of the Century’), the Juraguá plant would have four reactor generator units, each with a capacity of 417 MW. In the first instance, the government proceeded to build two reactors, construction starting on the first in 1983 and the second in 1985. The power plant was part of a larger nuclear programme according to which four more reactors would eventually operate in Holguín Province and another four in Pinar del Río. One day, Cuba would rely on nuclear fission alone for electricity generation.Footnote 62 Electrification, in turn, was critical to the successful infrastructural integration of Cuba. With a centrally-controlled national grid, industrial production would not be geographically limited to places with energy resources on site but could be ‘rationally’ developed by the socialist government without concern for limited energy supplies.

The reactors’ design was the Soviet VVER-440. ‘VVER’ was the Russian acronym for water–water energy reactor, meaning that pressurised water would be used to cool and moderate the reactor core. The ‘440’ implied that the reactors would have an electrical capacity of 440 MW. Cuba nonetheless opted for a plant with several non-standard features for the reactor type. Model V-318 would have containment buildings to prevent radioactive fallout in the case of a meltdown. The buildings would also be resistant to the shockwave from a direct aircraft hit. As Cienfuegos was located in a seismically active area, moreover, the reactors were designed to withstand earthquakes. The plant was sited at only 17 metres above sea-level, which would ensure that, even in the event of a tsunami, it would have a continuous supply of cooling water.Footnote 63 The likelihood of a tsunami forming in the Caribbean Sea was one in 10,000 years, according to Fidel Castro, and, in government discourse, the precautions taken even in this regard attested to the high level of safety characterising the project.Footnote 64 As a result of these features, the reactors would have a lower electrical output than the standard Soviet model.

Nuclear power again resonated with the belief in technology as a liberating force, which would bring socialist development to Cuba. The nuclear plant would develop the country's productive forces in one leap, thrusting Cuba on to a higher stage of techno-material development. Fidel Castro had already suggested in the Moncada Programme that nuclear energy would allow a progressive government to electrify the entire country, ‘given that the application of nuclear energy is now a reality in this branch of industry’.Footnote 65 In 1984, he boasted that the first reactor then under construction in Juraguá would have a greater capacity on its own than that of the whole combined electrical industry prior to the Revolution.Footnote 66 In all of Latin America, only Argentina and Brazil had successfully developed nuclear capacity with their Atucha, Embalse and Angra plants.Footnote 67 Thus, the nuclear reactors in Juraguá testified to the progress the Revolution brought not only to Cuba, but also to Central America and the Caribbean.Footnote 68

It is important to remember that the modernisation process essentially had the same material characteristics when Cuba followed the Soviet development model as when it followed the US example in the early twentieth century. As Paul Josephson reminds us, engineers and politicians in the Soviet Union and the United States frequently looked to each other to make sure they were on the right ‘development’ track.Footnote 69 From the Marxist-Leninist point of view, the difference between capitalist and socialist development was that modern technology entered into qualitatively different social relations in the two Cold War blocs. Under capitalist relations of production, more advanced productive forces increased the exploitation of the working class; under socialism, they contributed to the liberation of the proletariat. Materially, however, mechanisation, electrification and automation were neutral features of an imminent nuclear modernity.Footnote 70

In his study of the Cuban nuclear programme, the US-based scholar Jonathan Benjamin-Alvarado suggests that the Cuban leadership pursued the project above all for the sake of international prestige.Footnote 71 However, the Executive Secretary of the Cuban Atomic Energy Commission (CEAC) argued that Cuba ought to be entitled to nuclear power as a sovereign nation.Footnote 72 Nuclear technology represented the most advanced material base of any developed nation, and nuclear power was a historical necessity for the development of Cuba's productive forces. The Executive Secretary referred to above was Cuba's leading nuclear physicist, Fidel Castro Díaz-Balart, who also happened to be the Cuban leader's eldest son. Fidelito, as he was known, was appointed to lead the development of both electrical nuclear capacity and radiochemical applications in the pharmaceutical and agricultural industries. Under the purview of the CEAC, Cuba would develop a standalone nuclear industry that would ultimately be independent of foreign technicians and advisers.Footnote 73 For the time being, however, the project was unthinkable without Soviet support. ‘Only within the framework of cooperation between the socialist countries is it possible for a country like Cuba to undertake this giant project’, a propaganda film from TeleNuclear, aired on Cuban television in the 1980s, made clear.Footnote 74

Besides the nuclear plant, the government was developing Cienfuegos into a hub in the energy sector. While Fidel Castro had identified nuclear energy as the definitive solution for electricity generation, electrification had proceeded based almost exclusively on fuel-oil combustion since 1959. Prior to the Revolution, the Florida-based Compañía Cubana de Electricidad had supplied electricity generated in oil-fired thermoelectric power plants, albeit primarily to white, affluent urban areas. At that time, three multinational companies – Standard Oil of New Jersey (Esso), Texaco and Royal Dutch Shell – delivered fuel oil to the Compañía via their refineries in Havana and Santiago de Cuba. In 1960, however, the Eisenhower administration urged the refineries to cease operations, following the Cuban leadership's trade deal with the Soviet Union for complementary oil imports.Footnote 75 As the conflict escalated into a US oil blockade, the revolutionary government nationalised the refineries along with the Compañía Cubana de Electricidad, the Cuban Telephone Company and 36 sugar mills on 30 August 1960. Soon, the United States’ blockade developed into the more general trade embargo against Cuba. Fortunately for the Cuban revolutionaries, the Soviet Union agreed to fill the supply gap left by the United States by exporting oil in exchange for sugar on terms that undermined unequal exchange.

Subsequently, the Cuban government invested heavily in thermoelectric generating technology to facilitate industrialisation and automation. In the late 1960s, new power plants opened in Mariel, Santiago de Cuba and Nuevitas with Soviet technology. In O'Bourke, the nationalised utility synchronised the ‘Carlos Manuel de Céspedes’ thermoelectric plant with Cuba's western grid in 1978. The plant's first two units – this time imported from Czechoslovakia – each had a capacity of 66 MW, and the plant was later expanded with two generators from Japan, each of which was rated at 169 MW.Footnote 76 A short distance from the power plant, the government also sited a new oil refinery to be built with Soviet support in the course of the 1980s. It was the largest industrial project in the region apart from the nuclear plant.Footnote 77 The refinery's bayside location would facilitate Cuban petroleum exports (resulting from the refining of Soviet crude oil), but the fuel oil coming out of it could conveniently be used in the ‘Carlos Manuel de Céspedes’ thermoelectric plant down the road.Footnote 78

Hence, in the energy sector too, Cienfuegos entered into in a network of socio-ecological relations with international reach: the Cuban Ministry of Sugar (MINAZ) exported sugar produced in the Las Villas area, in part via the ‘Tricontinental’ loading terminal in O'Bourke. In return, the Soviet Union sent crude oil to Cuba's refineries. When complete, the refinery in Cienfuegos would be a key node in this trade network. MINAZ then used oil products of various kinds in its mills, cane harvesters and lorries, while the nationalised electricity company burned fuel oil in its thermoelectric plants to provide electricity for industrial and residential use. Cuba's industrialisation in general, and Cienfuegos’ in particular, thus was ever more closely interwoven with sugar monoculture and Cuba's relations with the Soviet Union.

Here, however, the nuclear power plant would play a highly strategic role in the eyes of the revolutionary government. The propaganda film from TeleNuclear asserted that the plant would ‘represent a qualitative change in the national energy system’.Footnote 79 By substituting enriched uranium for oil, the nuclear reactors would reduce the need for oil imports significantly. With four reactors in Juraguá, Fidel Castro estimated that the plant would displace up to 2.4 million tonnes of fuel oil per year.Footnote 80 This would again transform the geometry of social and ecological relations converging in Cienfuegos. Reduced oil dependence would allow the Cuban government either to cut back its oil imports, diminishing its dependence on the Soviet Union, or to re-export Soviet oil for hard currency on the international markets.Footnote 81 Fidel reasoned that nuclear energy would thus enhance Cuba's development.Footnote 82 More widely, Sonja Schmid argues that the European CMEA states that also imported Soviet nuclear technology – notably East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria and Hungary – saw it as a means of reducing their dependence on oil and gas imports from the Soviet Union. The Soviet government, by contrast, regarded nuclear transfer as a way to ‘strengthen inner-bloc ties and to further demarcate their sphere of influence’.Footnote 83 Schmid suggests that this contradiction was resolved in the socialist countries’ shared belief in advanced nuclear technology as an essential material base for historical progress.

Cienfuegos in the Nuclear Cold War

Cienfuegos’ position as a nuclear city made it a centre of contestation in the bipolar Cold War. Given Cuba's geopolitical role following the Crisis de Octubre (the Cuban Missile Crisis), Cienfuegos developed what Gabrielle Hecht would call dangerous ‘nuclearity’ in the eyes of the United States. Nuclearity is a socially-contingent practice whereby a place or object is designated as ‘nuclear’, with political implications.Footnote 84 In this regard, the construction of the Juraguá plant was not the first project to confer nuclearity on Cienfuegos.

In August 1970, aerial photographs from a US reconnaissance mission indicated that Cuba was building a new naval facility on Cayo Alcatraz, a small island in the south of Cienfuegos bay. Next to a set of barracks, the photographs also showed a football field. To the CIA's analysts this constituted an inconsistency: Cubans played baseball, not football. Russians did, however. Previously, in July 1969 and again in May 1970, Soviet Foxtrot and Echo-II class submarines had called at Cienfuegos to be serviced by accompanying tenders. When two barges arrived with equipment to dispose of radioactive waste from submarines in September 1970, the United States raised the issue to a matter of top-level diplomacy.Footnote 85 Evidence suggested that the Soviet Union was building a base for missile-carrying nuclear submarines. On 25 September 1970, the Soviet Ambassador to Washington received a note from President Richard Nixon stating that the United States regarded Soviet actions as a possible breach of the ‘understanding’ reached after the 1962 Missile Crisis.Footnote 86 This understanding implied that the United States would refrain from invading Cuba, as long as the Soviet Union withdrew all offensive weapons from the island.

The Cienfuegos crisis was largely resolved through informal conversations between Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin and US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. Now-declassified memoranda from these exchanges show that an oral agreement was reached on 6 October to honour the understanding from 1962. Even so, the Soviet government insisted on its navy's right to periodically visit Cienfuegos, or any other port, in accordance with international maritime law. Kissinger admitted that this was a right the United States hardly could deny them.Footnote 87 Despite the agreement, the Soviet Union continued to tender submarines in Cienfuegos. In February 1971, they serviced a November-class nuclear attack submarine, and the conflict heated up again. At this point, Kissinger forwarded a new note from Nixon stating that submarine tenders had been in or around Cienfuegos for 125 of the past 166 days and that the United States saw this as a breach of their mutual understanding.Footnote 88 The Soviet Union then withdrew their nuclear submarines and tenders and Cienfuegos’ status as a place of nuclearity waned.

In April 1986, however, when construction had already started on the reactors in Juraguá, disaster struck at the ‘V. I. Lenin’ nuclear power plant in Chernobyl. Critics in the United States soon suggested that the Juraguá plant was a ‘Cuban Chernobyl’ in waiting. In the case of a reactor meltdown, they estimated that radioactive fallout would create ‘serious ecological damage as far north as Tampa, Florida’, not to mention in the Cuban archipelago.Footnote 89 Cubans who had been involved in the construction works, but emigrated in the 1990s, also reportedly claimed that essential welding jobs had been poorly carried out and constituted a safety threat.Footnote 90 By contrast, Fidel Castro Díaz-Balart insisted on the power plant's safety. On the one hand, the Chernobyl reactors had a completely different design from the Juraguá plant, as they used graphite rather than pressurised water to moderate the reactor core. The Cuban reactors would also have containment buildings. On the other hand, two plants with pressurised-water reactors were already operating at Turkey Point and Saint Lucie in Florida. In the southern states of Tennessee, the Carolinas, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia and Florida, 35 plants of a similar design were already in active use. Despite this, Fidelito argued, only Juraguá was – unfairly – being designated a possible nuclear hazard.Footnote 91

Ciudad Nuclear

While the nuclear programme epitomised Cuba's efforts at industrialisation, it also had specific urban form. Just east of the reactor construction site, the Cuban government developed a new housing zone as part of the project (Figure 2). Initially, construction workers, engineers and welders lived in Ciudad Nuclear. Once the reactors were operational, the ‘city’ would house power-plant workers. A workers’ town was of course no anomaly in the Cuban landscape but an integral dimension of the urbanisation process. Bateyes had been built alongside sugar mills since colonial times, and a purpose-built ‘university city’, Ciudad Universitaria José Antonio Echeverría (CUJAE), was constructed on the outskirts of Havana in the early 1960s to house students.Footnote 92 While building a nuclear power plant with Soviet support, it was also logical to create a workers’ town. Soviet state architects often developed new cities next to heavy-industrial extraction sites. The Stalinist steel city of Magnitogorsk is the most emblematic example;Footnote 93 Pripyat, overlooking the reactors in Chernobyl, the most notorious.

Figure 2. Workers’ Housing in Ciudad Nuclear

While the nuclear power plant would thrust Cuba on to a higher stage of technological development, Ciudad Nuclear also represented a break with the past. If Cienfuegos’ urban form represented a ‘colonial space’ in the dependency lexicon, Ciudad Nuclear constituted a space of and for the Revolution and its emerging nuclear modernity.Footnote 94 The city was set out along two parallel thoroughfares. Most buildings would have five floors and were built with the Yugoslav IMS construction technology. First, a prefabricated skeleton of reinforced concrete was set in place for each building; then slabs were hoisted into place to constitute interior walls and a façade, leaving space for prefabricated stairs, balconies and other design features. The Revolution's first major housing project, Ciudad Camilo Cienfuegos in Habana del Este, had been built largely with non-industrial techniques, but prefabrication was employed on a large scale to build the Distrito José Martí in Santiago de Cuba in the late 1960s. Prefabrication then became increasingly prevalent in the 1970s, when Cubans received paid leave to work in housing construction as part of the so-called Microbrigadas (worker collectives for the construction and communal distribution of housing).Footnote 95

The IMS system was named after the Institut za Ispitivanje Materijala (Institute for the Testing of Materials), where it was developed in the 1940s and 1950s. The IMS would facilitate the reconstruction of the newly socialist but war-torn Yugoslavia with industrial precision and efficiency and was notably used by the planners of New Belgrade (Novi Beograd) for housing construction. Again, the vision of modernity's materiality crossed the ideological divide of the Cold War. Rooted in the thought of Le Corbusier and the International Congresses of Modern Architecture (CIAM), New Belgrade engendered the same high-modernist planning ideals that were espoused by planners and politicians from Brasilia to Tashkent and Chandigarh.Footnote 96 In Yugoslavia, the IMS system was soon promoted as an export asset.Footnote 97 An IMS factory in Cienfuegos opened in 1978 with a reported capacity of 1,500 dwelling units per year. In Ciudad Nuclear, the revolutionary government planned for 4,500 units.Footnote 98

Compared to colonial Cienfuegos, Ciudad Nuclear had a qualitatively different city plan. The housing complexes congregated around a cultural centre, with a public library, bookshop and professional theatre company. As in all Cuban revolutionary cities, the centralised infrastructure of the socialist state would be present: not only public electric lighting, aqueducts and sewers, but also bodegas for the distribution of food rations, a polyclinic, a pharmacy, primary and secondary schools, a day-care centre and a post office. The CEAC also established the short-lived Juraguá Electronuclear Polytechnic University, which focused on nuclear physics and radiochemistry.Footnote 99 Thus, as in the Soviet steel city of Magnitogorsk, a socialist subjectivity and the embodied experience of an approaching, if fraught, modernity were fashioned in Ciudad Nuclear.Footnote 100 Representing the ideals of the Cuban Revolution, Ciudad Nuclear constituted a built environment for modern, educated socialist citizens. It was also an interpersonal meeting place seen to reinforce social relations between Cuba and the CMEA countries. In 1984, for example, Fidel Castro noted that 5,500 Cubans were living in Ciudad Nuclear alongside 188 Soviet and 82 Bulgarian engineers.Footnote 101 In the shadow of the materialising reactor domes, a qualitatively new urban society was emerging. At least, so it seemed in the grand narrative of the Cuban Revolution.

An Interrupted Nuclear Modernity

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, Cuba lost not only its closest political ally, but also its main trading partner. Boris Yeltsin's Russian government demanded renegotiation of the Soviet Union's bilateral agreements, including the contracts for the Juraguá plant. In September 1992, Fidel Castro announced that the nuclear programme would be suspended indefinitely.Footnote 102 Cuba, now suffering from unequal exchange, could no longer afford the Russian technology. At the same time, Russia required Cuba to purchase oil and sell sugar at world-market prices. Between 1989 and 1993, Cuba's imports of crude oil declined by 86 per cent, as Fidel Castro declared that the country had entered a ‘Special Period in Peacetime’.Footnote 103 The refinery in O'Bourke opened in 1991 but had to close again four years later due to a lack of crude supply. In and around Cuba's centrales, production ground to a halt. Las Villas’ sugar fields lay fallow, deprived of synthetic fertilisers and pesticides, and industrial machinery was lifeless without diesel, fuel and lubricant oils.Footnote 104

As work stopped on the nuclear reactors, construction of Ciudad Nuclear ended abruptly. While people still live in the urban enclave across the bay – both Cubans and a few remaining Russians – many buildings were never finished. Abandoned to the elements, some are today in danger of collapse. In defence of the nuclear programme, Fidel Castro Díaz-Balart noted that approximately 1,300 Cubans had graduated as nuclear physicists from the Juraguá Electronuclear Polytechnic and Soviet universities by 1992.Footnote 105 Yet there was no nuclear plant where they could put their knowledge to work. Their high-modern city, a long distance from the Cuban capital, was falling into decay. In large numbers, Cubans from Cienfuegos and provinces further east migrated to Havana during the Special Period in search of employment, ‘a process that mirrors migration flows in pre-revolutionary Cuba’, Alejandro de la Fuente notes. With 92,000 Cubans applying for residential status in Havana in the spring of 1997, the government banned all migration to the capital as unemployed newcomers often ended up living in ‘subhuman conditions’.Footnote 106

In the past decade, however, Cienfuegos has seen renewed investment. In 2007, Cuba's then-acting President Raúl Castro and Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez re-inaugurated the oil refinery following extensive retrofitting, making Cienfuegos a key node in PetroCaribe. PetroCaribe, a regional oil-trading bloc dominated by Venezuela and Cuba, was established in 2005 to overcome the challenges faced by the Caribbean's island-states, given their heavy oil-import dependence and low purchasing power on the world market – unequal exchange, in other words.Footnote 107 Cuban–Venezuelan joint venture Cuvenpetrol S.A. (founded in 2006) operated the refinery, which constituted the single largest project to integrate the Cuban and Venezuelan national economies since the mid-2000s. Furthermore, in 2007, Cuban families moved into a new residential area north of O'Bourke, named Reparto Simón Bolívar, where the Venezuelan government had donated prefabricated buildings as part of PetroCaribe's social programmes.Footnote 108 The process of socialist urbanisation found new material expression in Reparto Simón Bolívar, again tied to a historically-specific form of energy development. The houses here are petrocasas, so-called ‘oil homes’, made from the plastic polyvinyl chloride (PVC) produced by the Venezuelan petrochemical industry to derive social benefits from the country's oil wealth.Footnote 109

Despite this upswing, Cienfuegos’ place is shifting again in the geometry of wider political–economic relations. In August 2017, the Cuban government re-nationalised the refinery, reportedly responding to Venezuela's failure to pay for services incurred under the PetroCaribe agreement.Footnote 110 Cuba has also looked for new sources of oil as the Bolivarian Revolution in Venezuela has entered what may be a terminal state. In a process unfolding in parallel to PetroCaribe, then, Cienfuegos was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2005, to the benefit of the Cuban tourism industry, for the reasons noted above. While UNESCO states that the city constitutes an ‘outstanding example’ of modernist urban planning, this refers not to the concrete slabs of Ciudad Nuclear or the plastic walls of Reparto Simón Bolívar, but to the colonial modernity of Cienfuegos’ nineteenth-century town centre.Footnote 111 Cienfuegos is today an important way station on the circuit for Western tourists, whose purchasing power allows them to take advantage of Cuba's low-wage economy.

Conclusion

The rationale behind the policy for urban restructuring and centralised energy development emerged from a critique of the colonial political economy. Embedded in the pursuit of nuclear modernity, it also took on distinct urban form. Ciudad Nuclear represented an article of faith in infrastructural integration, centralised redistribution and automated technology powered by oil and nuclear energy as determinants of social progress. However, Cuba's spatio-infrastructural transformation was contingent on relations extending beyond its cities in space and time.Footnote 112 Ideationally, Cienfuegos’ Cold War development was a success as long as Cuba was taking part in qualitatively different, equal-exchange relations with the CMEA. The government's inability to sustain these relations after the collapse of the Soviet Union suggests that Cuba's nuclear modernity ultimately was a failure, a failure manifested in the decay of Ciudad Nuclear and the ruins of the reactors in Juraguá. Despite this, Cienfuegos’ vital position in the revolutionary economy invites us to look beyond Havana and Latin America's major cities if we want to understand the Cold War in the region. Cienfuegos brings circulations of knowledge to light that broaden the ‘geographies of theory’ in urban, energy and Latin American studies.Footnote 113 The city's history demonstrates the significance and difficulty of achieving alternative, possibly more equitable, urban forms in Cuba and beyond.

Acknowledgements

Part of this research was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (UK), grant ref. ES/S01067X/1. I thank Bridget Chesterton, Melixa Abad Izquierdo, Donald Kingsbury, Alex Loftus, Simone Vegliò, the editors and three anonymous reviewers for sharing their insights and commenting on previous drafts.