INTRODUCTION

Historians and feorm

How did early English kings get their food? Despite the many obscurities surrounding the emergence of kingdoms and kingship between the fifth and eighth centuries, this is a question for which historians have long had a ready answer. From the earliest times, kings are thought to have received renders of food, known in Old English as feorm, from the free peasants of their kingdoms. The consensus model was established by Frederic William Maitland in his 1897 work, Domesday Book and Beyond. Footnote 1 Frank Stenton summarized it as follows:

The king’s feorm or food-rent … is often mentioned, though rarely defined, in early documents. In its primitive form it consisted of a quantity of provisions sufficient to maintain a king and his retinue for twenty-four hours, due once a year from a particular group of villages. It was naturally rendered at a royal village within or near to the district from which it came, and it was applied to the king’s use by the reeve whom he had set in charge of this estate.Footnote 2

The burden of supplying the royal household in this way was meant to be equitably distributed, such that the feorm obligation of each free household depended on the size of its landholding. A family with a full hide of land owed twice as much, in theory, as a family with half a hide. Royal households are imagined to have toured their kingdoms constantly, at least in part because the food renders available to them in any one locality were finite. Once they had been eaten it was necessary to move on.Footnote 3

It is often assumed that these renders of feorm were royal households’ primary source of food, with kings’ own lands playing a minor supporting role at best. For the most part this negative assessment of the significance of royal demesne production is neither argued nor even asserted directly, but is a logical corollary of framings that assign a central role to food renders. It is, for instance, implicit in Thomas Charles-Edwards’ assertion that, when on circuit within their own kingdoms, royal households ‘must be maintained by food renders that were likely to have met all their main needs’.Footnote 4 Rosamond Faith is unusual in having confronted the issue directly, arguing that food renders remained the ‘basis of royal support’ into the eleventh century, and that their ready availability ‘may have ensured that many royal vills remained collecting centres rather than agrarian enterprises’.Footnote 5 This is not a subject to which archaeology can easily contribute. As Helena Hamerow has pointed out, aside from rare cases, most early medieval settlement sites have very few finds in general, let alone finds which could definitively establish their status.Footnote 6 Identifying possible ‘home farms’ from which the upper elite’s demesne lands were directly exploited is a necessarily uncertain endeavour, a matter of finding settlements with unusual features in proximity to known elite centres and looking for indications of a link between them. Duncan Wright has suggested three sites lying between 1.5 and 4 km from religious houses at Soham, Ely and Malmesbury as possible ‘home farms’ but he follows Faith in framing them as a distinctively ecclesiastical phenomenon, which developed because stationary ecclesiastical communities’ dietary needs could not be met through the traditional practices of itineration employed by kings. His hypothesis is that these ecclesiastical ‘home farms’ differed significantly from their unidentified royal equivalents, which did not experience the same pressure to provide year-round food supplies.Footnote 7

The idea that food renders were both economically central to royal households and rooted in the distant past has implications for our understanding of the origins of kingship itself, which have been worked through in detail by Robin Fleming.Footnote 8 Her model helpfully draws together a number of strands of scholarship on regiones – small territories that appear to have been the political building blocks from which kingdoms were constructed – and carries the implications of these ideas through to their logical conclusion. In common with many others, she understands regiones as tributary territories, characterized by systems of food renders that sustained central households.Footnote 9 She traces kings’ emergence back to an obscure point, probably in the early-sixth century, when the ambitious heads of wealthy households began to extort food supplies and other services from their neighbours, either creating these small regiones from scratch or redefining existing social and geographical units as tribute-rendering territories. ‘The easiest way for these would-be rulers to gather what was owed to them was to transform their residences into central places and use them as collection points for all the goods and services to which they were entitled’.Footnote 10 The more successful of these proto-kingly figures went on to seize control of many such central places, and found they were able to support larger households by travelling on a circuit to each of them, living ‘for a few weeks on the bounty that they found there’.Footnote 11 Thus the emergence of kingship itself is imagined to have been inextricably entwined with the establishment of the familiar system of itinerant royal households sustained by feorm.

However, royal food renders have gained the greatest historiographical prominence not for their central economic role in sustaining royal households, nor for what they imply about the origins of kingship as an institution, but because the right to receive feorm often passed into non-royal hands. As kingdoms grew, kings’ feorm entitlements exceeded what they needed to supply their households by ever greater margins, so it made sense to give them away to favoured nobles along with the right to receive other, much more obscure, ‘public’ dues. One of Maitland’s key insights was that this was what was happening in early charters, and that it led to an important conceptual slippage.

Whatever the origin of the king’s feorm … it becomes either a rent or a tax. We may call it the one or we may call it the other, for so long as the recipient of it is the king, the law of the seventh and eighth centuries will hardly be able to tell which it is. The king begins to give it away: in the hands of his donees, in the hands of the churches, it becomes a rent. … In some of the very earliest land-books that have come down to us what the king really gives, when he says that he is giving land, is far rather his kingly superiority over land and landowners than anything that we dare call ownership.Footnote 12

This interpretation of the rights conveyed in charters has much to recommend it and mainstream historiographical opinion rapidly coalesced around it. Twentieth-century scholarship included some dissenting voices, who argued that royal charters did in fact convey outright ownership over all the land transferred, but Maitland’s view that a combination of ‘superiority’ and ownership rights was usually involved has always dominated and it now appears to have won out.Footnote 13 In the terms Faith has made standard, kings are understood to have had full ownership over tracts of ‘inland’ as well as looser superiority over areas of ‘warland’, and to have transferred mixed bundles of these rights to others in both written and unwritten grants.Footnote 14 Monasteries are thus understood to have been endowed not just with areas of farmland to exploit as they wished, but with rights to receive feorm and other ‘public’ obligations from free peasants resident on tracts of formerly royal warland. Indeed, charters for religious houses are just the written and preserved tip of a much larger, perhaps mostly oral, iceberg of royal patronage. As Charles-Edwards has pointed out, kings were expected to endow the warriors who served in their households with land rights to reward them for their service; they also needed to allocate resources to ensure that the large households of queens and sub-kings, bishops and ealdormen, were adequately fed; and these great magnates also had military retinues which served in the expectation of landed reward.Footnote 15 As kingdoms expanded, feorm is imagined to have become much more than just a system for the supply of the king’s household. The right to receive royal food renders became central to the period’s land-based patronage politics. The feorm rendered by free peasant households did not just feed the king and his retainers; routinely redirected by royal grants, it sustained a broad chunk of the ruling elite.

This is where the conceptual slippage highlighted by Maitland becomes important. He theorized that in non-royal hands the ‘public’ nature of the obligation to provide food renders was easily forgotten, and the feorm land-owning peasants paid to lords and churches in time became impossible to distinguish from the rent paid by tenants to landlords. This hypothesized process lies at the core of most modern understandings of the centuries-long process of ‘manorialization’, which saw England’s land-owning early peasantry reduced to a state of rent-paying dependence. In the Marxist framing that has brought conceptual rigour to this subject, feorm was originally an obligation characteristic of the ‘peasant mode of production’: a relatively light render that fell universally on free land-owning households. Eventually, it seems, it became just another form of rent in a ‘feudal mode’ economy where virtually all peasants were tenants of lords.Footnote 16 Modern commentators have built on Maitland’s reasoning, hypothesizing that this fundamental economic shift was driven forward by lords and churches endowed with rights to the king’s feorm. Keen both to increase the scale of this obligation and to reframe the dues they received as forms of rent, over time they were able to exploit their structurally powerful positions and get their way. Our evidence does not allow us to track this dubious form of economic ‘progress’ with any precision. Few would dispute that a peasant mode economy existed in the sixth century and there can be no doubt that the feudal mode had triumphed by the twelfth, but opinions vary greatly as to when in the intervening period to place the shift. Whereas for Chris Wickham the process was ‘already relatively complete by 900 or so’, Fleming identifies the tenth and eleventh centuries as the crucial period of change, and Faith has recently argued that the crucial conceptual shift fits more plausibly in the wake of the radical change in elite culture – the emergence of new ‘feudal thinking’ – ushered in by the Norman conquest.Footnote 17

The question of how kings got their food is thus not the minor issue it may initially seem, an administrative technicality of interest only to myopic period specialists or broad-minded antiquarians. Much has been built on the long-standing consensus that free peasants were, by ancient custom, expected to supply their rulers’ households with food. These food renders have informed theories about the beginnings of English kingship in the era before it emerges in our written sources; they are central to our understanding of what was at stake in the land-based patronage politics that characterized kingdoms from the seventh century onwards; and they sit at the core of ongoing debates about long-term processes of social, economic and cultural change that resulted in the subjection of England’s once-free peasantry. Ever since Maitland, ideas about food renders have been woven through historical and archaeological interpretations of a number of subjects at a foundational level. Any significant rethinking of his vision of feorm is likely to have far-reaching implications.

Reframing feorm

In this article, we set out the core case in favour of such a rethink, offering a different interpretation of the king’s feorm. There is a great deal to suggest that the word feorm in this context, and virtually all related contexts, referred to a feast and not to render of general-purpose food supplies (‘feast’, of course, is a well-attested sense of the word feorm).Footnote 18 Free peasant households appear not to have been obliged to provide early kings with food to support their ordinary diets, but it seems they were expected to host visiting kings at lavish communal banquets. These feasts are likely to have involved several hundred people eating prodigious amounts of food; anyone with the fortitude to consume double an ordinary day’s calorie intake would easily have been able to do so. The implied numbers are larger than we would expect for just a royal household and a few noble guests, and would fit well with the theory that the peasants who provided the food traditionally attended these feasts as hosts. And, crucially, the food available was heavily skewed towards animal products. As this essay’s companion article shows, there is little in the bioarchaeological record for this period consistent with the regular consumption of such enormous quantities of animal protein, even among the elite. Unless further data changes the archaeological picture, the inference must be that these lavish feasts were infrequent occurrences. We have no grounds for imagining that kings spent their years flitting from one locality’s feast to the next, eating vast quantities of mutton and beef. Rather, we ought to envision them spending most of their days eating a cereal-based diet similar to that of the peasantry, presumably sourced primarily from their own landholdings. The food and drink at these occasional grand feasts may have been something of a treat for royal households, but it is unlikely that kings attended them because they had a pressing economic need for large quantities of food. It is more probable that these feasts were important in political and symbolic terms; they were special occasions on which a king’s legitimacy was publicly recognized and his authority accepted.

This article makes the case for this interpretation in three steps. It begins with a quantitative analysis of the food list that appears in chapter 70.1 of the laws of King Ine of Wessex (henceforth Ine 70.1). This allows us to establish the proportions of the meals envisaged, and also the probable size of each individual portion: these features of the food list strongly suggest it was conceived as a list of supplies for a feast, not as a render of general-purpose food supplies. The second stage is to extend this quantitative analysis and confirm this finding, by demonstrating that Ine 70.1’s characteristic features – the large portion sizes and the relative proportions of bread, ale and animal products – align remarkably closely with a wider corpus of food lists from early medieval England. The final step is to set these findings in their broader context, reviewing the wider body of documentary references to both feorm and its Latin near-equivalent, pastus. It is not feasible to provide a comprehensive treatment of these terms’ usages here, but a brief survey is sufficient to make the point that there is much in this wider body of evidence that is suggestive of a context of feasting.

A lot of historiographical digestion will be required before the wider ramifications of reframing feorm along these lines are fully apparent. Replacing food renders with local feasts makes it much more difficult to imagine early regiones, the political building blocks of kingdoms, as territories defined by tributary relationships; it demands that we think again about what kings were giving away when they transferred their rights over vast land-units in charters; and in questioning the plausibility of the conceptual slippage identified by Maitland (the obligation to provide a feast being readily distinguishable from an obligation to pay rent), it suggests that the dominant model of manorialization requires revision. Each of these is far too involved a topic to address comprehensively here, but the article concludes with an attempt to survey the likely historiographical implications of reframing ‘food renders’ as feasts, seeking to highlight not only potentially fertile avenues for further research and reinterpretation, but also points at which such a reframing serves to provide additional support to existing lines of argument.

A QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS OF INE 70.1

The problems of quantification

We begin, then, with the Laws of Ine. This text survives as part of King Alfred’s Domboc, a late-ninth-century work in which an extensive preface based on the Book of Exodus is followed by Alfred’s own laws, with a compilation of legislative edicts attributed to Ine following as an appendix. There are no indications that the Alfredian compiler amended this text when creating the Domboc, so it is generally accepted as deriving from Ine’s reign (c. 688–726).Footnote 19 The relevant passage is clause 70.1:Footnote 20

From ten hides as fostre: ten fata of honey, 300 loaves, twelve ambra of Welsh ale, thirty of clear ale, two full-grown cattle or ten wethers, ten geese, twenty hens, ten cheeses, an amber full of butter, five salmon, twenty pundwæge of fodder and 100 eels.Footnote 21

Though it is not made explicit, the fact that this passage appears in a compilation of royal legislative decrees strongly implies that the right to fostre, or ‘sustenance’,Footnote 22 being asserted here is a royal right, as virtually all commentators have supposed.Footnote 23

A second foundational observation, and a highly significant one in the present context, is that the list includes several elements that imply a context of rapid consumption. The salmon and eels would of course have perished very quickly, perhaps the butter too, but the most telling indicator is that bread and ale are requested rather than malt and meal, or raw grain. Small round buns may have remained edible, in a dry and hardened form, for weeks or months after baking, but it is improbable that bread in this condition would have been acceptable in elite households. Even if its life was extended through the use of hops, which may not have been a universal practice, the ale would have soured in matter of days.Footnote 24 Quick consumption is also consistent with wethers (adult male sheep) being requested when ewes would have been the obvious choice for both dairying and breeding purposes, and with the specification that the cattle be full grown. There are good prima facie grounds, then, for thinking that the king is asserting his right to be provided with food to be eaten, as Debby Banham has long maintained.Footnote 25 The alternative, that the framers of this edict understood the foodstuffs listed to be destined for royal storehouses, the livestock for royal herds, would be difficult to reconcile with these aspects of the text. If this were what the author of Ine 70.1 had in mind, we would expect to see a list more like the one King Offa of Mercia took the unusual step of reserving in 793 × 796, when he granted a sixty-hide land-unit at Westbury-on-Trym, Gloucestershire, to the church of Worcester.Footnote 26 This list (discussed in more detail below) is our only other direct evidence for the content of the king’s feorm. It contains no butter or fish, and its cereal-based content is overwhelmingly raw grain rather than ale or bread. These features suggest that it was framed with the practicalities of storage in mind. The contrast with Ine 70.1 is telling.

Close analysis of the content of Ine 70.1 significantly reinforces this impression. To get a sense of how much food was demanded we need to make some interpretative assumptions. These are set out in full in Appendix 1, alongside those relevant to the other food lists analysed in this article. The crucial point to stress here is that though we are well placed to estimate the size of some components of the list, others are more obscure. These figures therefore vary in their reliability.

The estimates for animals are the most certain. The main challenge is the fact that modern farm animals are the products of long processes of selective breeding and therefore unreliable guides to what would have been available in our period. For poultry we have simply taken ‘small’ modern birds as our guide but for the larger animals that make up the bulk of the meat in our food lists it is less straightforward. The heights of early medieval livestock can be determined from the zooarchaeological record, yet how these heights relate to weight is uncertain. Even modern ‘heritage breeds’, old-fashioned today, are products of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century agricultural innovation and likely to be bulkier than early medieval livestock. The issue is compounded by the ‘dressing percentages’ used to estimate the expected meat yield of a carcass of a specific weight. Modern dressing percentages reflect animals bred to put on fat and muscle; they must be too high but it is hard to guess by how much. Though we initially attempted to come to estimates of meat yields by applying the proportions derived from smaller modern animals to zoorachaeological height data, we ultimately concluded that there was a significant risk this method would lead to overestimates.Footnote 27 Instead, we have opted for proxies. For beef and mutton, we have adopted A. J. S. Gibson’s closely reasoned estimates of the weight and calorie content of Scottish sheep and cattle, prior to the eighteenth-century advent of ‘improved’ breeds.Footnote 28 These numbers, based on early modern textual sources, are significantly lower than those produced by our efforts to apply ‘heritage breed’ proportions to early medieval skeletons. Indeed, it is possible that they are underestimates, reflecting more challenging climatic conditions than those which obtained in early medieval England. But a possible underestimate is exactly what we need in the context of the argument pursued here, which stresses the very large amounts of meat involved in food lists. To establish this point safely we need conservative estimates for meat yields.

Determining the size of loaves and cheeses is more difficult. We are particularly short of information on what constituted ‘a cheese’. We have taken a 3 kg Manchego (a hard sheep’s cheese) as our guide, but this barely qualifies as an educated guess; it would be unwise to make it bear much interpretative weight.Footnote 29 For the bread we have assumed a ‘loaf’ represents an individual portion. Much depends on this so it is fortunate that there are several good reasons to think it correct. The most important is the context of production. Banham has observed that even in the eleventh century it may have been rare for non-urban households to have access to an oven, and hearth-baking is likely to have produced loaves that were ‘shallowly risen (unless baked under a pot), quite small by our standards, and almost certainly round’.Footnote 30 She points out that this is consistent both with monastic sign-language, which suggests that the loaves silently passed along refectory tables were small and round, and with our one relevant archaeological find: some badly charred round buns found in the remains of an eleventh-century house fire in Ipswich, which are unlikely to have measured more than about fifteen centimetres in diameter before the fire.Footnote 31 To Banham’s points we can add that the Liber Eliensis implies that each monk received his own individual loaf (or possibly multiple small loaves) at meal times when it explains that gifts of gold and silver to Ely were divided equally between the brothers and ‘set beside everyone’s loaves in the refectory’.Footnote 32 All the same, because our assumptions need to be conservative in the context of an argument that stresses the surprisingly small quantities of bread in many contemporary food lists, we have tried to err on the side of generosity and assumed a loaf at the upper end of what is plausible. We estimate a loaf weighed 300 grams, equivalent to approximately six slices of modern British ‘thick-sliced’ supermarket bread.

The most problematic area of haziness is measures of volume. Ine 70.1 refers to ‘ambers’ (ambra) of ale and butter, and ‘vats’ (fæta) of honey, and we encounter several other uncertain measures across other texts. Though it is tempting to read back from later medieval evidence in this context, it is unsafe to assume that measures of weight and volume remained basically stable across the centuries.Footnote 33 Jean-Pierre Devroey gives the example of the Roman muid of twenty pounds, which became the eighth-century Frankish muid of sixty-four pounds, expanded to ninety-six pounds after reform in 792–793, only to emerge in the thirteenth century at a staggering 3600 pounds – 180 times its original size!Footnote 34 Fortunately, broadly contemporary medical texts provide a more reliable way of approaching the most important of our units, the ‘amber’. They reveal ambers rather smaller than the 145-litre barrels implied by thirteenth-century evidence.Footnote 35 An amber of ale is small enough to be lifted for an invalid to drink from until he vomits; at one point a ‘ten-amber’ kettle is called for; another recipe asks for two ambers of bullock’s urine.Footnote 36 This is something more like a bucket than a barrel. We can also infer something from the implicit hierarchy of units. In Bald’s Leechbook the amber appears to be the unit of volume above a ‘sester’, which is defined as fifteen pounds: approximately five litres of water.Footnote 37 A ten- to twenty-litre bucket seems plausible for the next step up from this, the sort of container that a single person could carry over a distance while full. We have assumed fifteen litres. This figure can be tested against King Æthelstan’s order that destitute Englishmen be provided every month with an amber of meal and either a shank of bacon or a ram worth four pence.Footnote 38 Fifteen litres of wholemeal flour contain approximately 28,940 kcal, or 965 kcal per day over thirty days. With the meat from a ram added, the destitute Englishman would have close to 1,600 kcal of food per day. Our fifteen-litre amber thus looks like it is of roughly the right order of magnitude; we may have underestimated slightly, but probably not by a very significant margin. Ine’s ‘vat’ (fæt) of honey is much less certain. The word itself seems to be a non-specific term applicable to containers of a range of sizes, meaning something like ‘vessel’, and does not occur in any of the other food lists analysed here.Footnote 39 Our guess of 4.2 litres is based on the ratio of ale to honey in an early ninth-century Kentish list of feast supplies (quoted below), but this should not be relied upon; the inference is defensible only if one assumes that the purpose of the honey was to sweeten the ale, which is not certain.Footnote 40

Ine 70.1 as a feast

Table 1 and Table 2 set out the results of applying these assumptions to Ine 70.1. The text offers two alternatives for livestock, permitting ten wethers to be substituted for two oxen. Rather than give separate figures for these two options, our calculations assume a middle-ground scenario in which one ox and five wethers are provided. This results in food supplies totalling 1.24 million kcal.Footnote 41

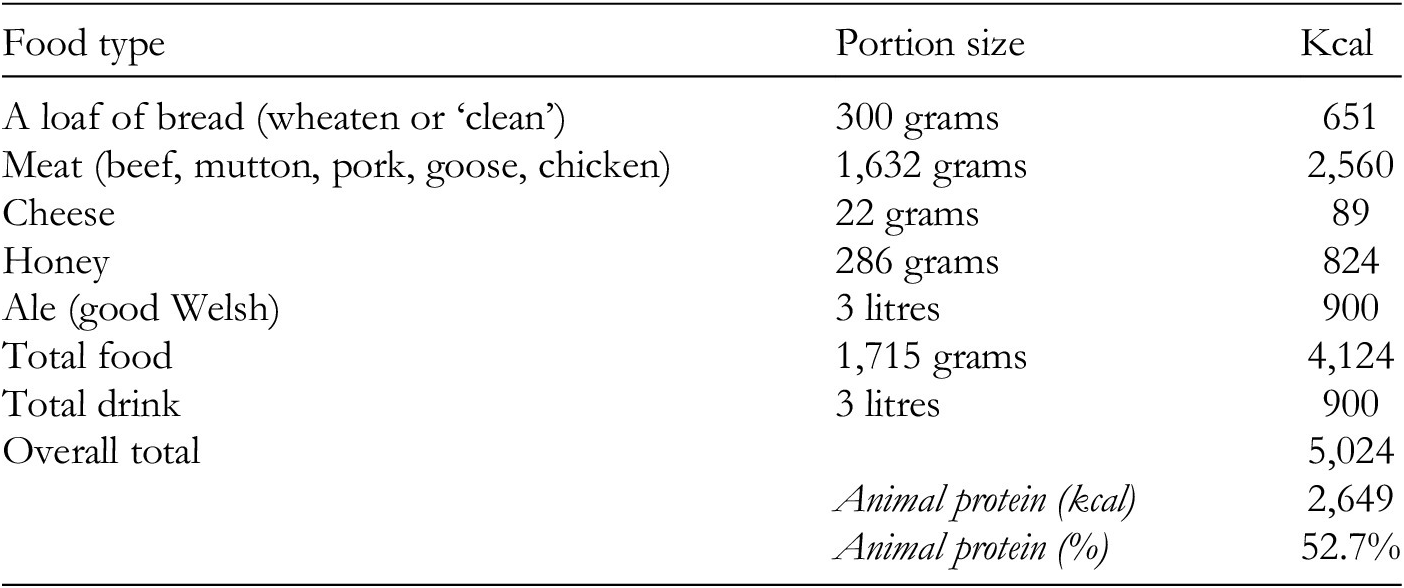

Table 1: The content of the food list in Ine 70.1.

Table 2: The individual meal implied by Ine 70.1, assuming one loaf per diner.

As discussed above, there are good reasons to hypothesize that the 300 loaves demanded imply that these supplies were intended to provide 300 individual meals. If that is the case, each of these meals involved 4,140 kcal. This is a lot of food, far too much for the idea that this represents an ordinary meal to be credible. It is, however, a believable amount to lay on for a feast on a special occasion, with the expectation that everyone would arrive hungry, eat their fill, and still leave leftovers to spare.Footnote 42 Divided equally, each participant would get their loaf and a varied selection of meat, fish and dairy products, all washed down with 2.1 litres of ale (possibly sweetened with the honey). The proportions are just about plausible, which is an encouraging sign for our assumptions, though the amount of meat and fish is prodigious. Each loaf was accompanied by over 500 grams of mutton and beef, plus another 500 grams in salmon, eel and poultry. The only way to reduce the scale of these seemingly gargantuan meals is to assume that an individual diner would take two or more sittings to eat their way through a single loaf of bread, which is an unlikely hypothesis given the many indications that loaves were small.

But regardless of the scale of the individual meals implied by Ine 70.1, the implications of this food list’s proportions are inescapable. If these were the general food supplies that sustained Ine’s household, as the literature has long assumed, his retainers and servants would have been accustomed to eating servings of meat and fish that weighed three to four times as much as the bread they accompanied. As we show in this article’s companion piece, this is more than just an implausible hypothesis, it is actively contradicted by the evidence of stable isotope analysis, which suggests that nobody in this period ate an ordinary diet so skewed towards animal products. The implication is that Ine 70.1 is a list of supplies for a special occasion rather than everyday consumption.Footnote 43 We are evidently dealing with a feast, and the sort of feast easily capable of defeating 300 avid appetites. We should probably imagine leftover meat being used for stewing in the days that followed.

OTHER LISTS OF FEAST SUPPLIES

But what about the possibility that there is some error in the text, or that we are misunderstanding its context? Could it be, for instance, that Ine 70.1 seems oddly proportioned because its figures have been distorted by a copyist, or because we have failed to appreciate that these supplies were augmented by another 2,000 loaves from another source, or because everyone understood that some of the cattle and wethers were for adding to the king’s herds and not for immediate eating?Footnote 44 Could it be a mistake even to analyse it as a practical measure? Ryan Lavelle has detected biblical inspiration in the parallel between this list and the daily food supplies said to have been brought to King Solomon by the many peoples he ruled, and other aspects of Ine’s list suggest a degree of idealization too: there must have been many places in Wessex where one hundred eels were not readily available.Footnote 45 Could Ine 70.1 simply be an ill-thought-through fantasy? Fortunately, we can safely dismiss all such doubts, because the seemingly odd features of the supplies listed in Ine 70.1 are far from unique. We have several comparable lists of food supplies for feasts, and they all look broadly similar: not much bread, a huge amount of meat, a good but not excessive quantity of ale. Ine’s list probably does represent an idealized vision of what every ten hides ought to be able to provide for the king, but whoever came up with it was not just plucking numbers out of the air. It is evident that this person’s ideas about the types of food and drink a king required from ten hides conformed closely to broader societal understandings of what was appropriate at a grand feast.

Two definite lists of feast supplies

The most straightforward of these other feast-supply lists appears in an endorsement to a charter, dated 795 × 805, in which Ealdorman Oswulf and his wife Beornthryth grant a twenty-sulung land-unit at Stanhamstede to Christ Church, Canterbury. In the endorsement, Archbishop Wulfred addresses the practicalities of how the community will commemorate these generous benefactors.

Now I Wulfred, by God’s grace archbishop, confirm these aforesaid words and ordain that the anniversary of them both shall be that celebrated every year on one day, on Oswulf’s anniversary, both with religious offices and with almsgiving and also with a feast of the community. Now I ask that these things be donated every year from Lympne, to which the aforesaid land belongs, from that land at Stanhamstede: 120 wheaten loaves and thirty ‘clean’ loaves, and one full-grown ox, and four sheep, and two flitches, and five geese, and ten hens, and ten pounds of cheese if it be a meat-eating day (but if it be a fast-day they are to be given a wey of cheese, and of fish, butter and eggs as much as they can get), and thirty ambers of good Welsh ale (which amounts to fifteen mittan), and a mitta full of honey or two of wine, whatever they can get at the time.Footnote 46

The crucial point here is that there can be no doubt that this food was to be consumed in a commemorative feast held on a single day, the anniversary of Oswulf’s death. Wulfred’s specification that the content of the render was to depend on whether Oswulf’s anniversary fell on a meat-eating day or a fast day puts this beyond doubt. Fortunately, the text mostly uses the same units as Ine 70.1, giving volumes in ambers and expressing bread in terms of loaves, which allows for direct comparison. All we need to add is an estimate for the amount of pork yielded by a flitch, or half a pig, which does pose some difficulties but is unlikely to have a significant effect on the overall picture.Footnote 47 The contents of Wulfred’s meat-eating-day feast (assuming honey rather than wine) are analysed in Table 3 and Table 4. The archbishop envisaged a smaller occasion than the drafter of Ine 70.1, with 150 loaves instead of 300, but the individual portions were even more lavish. For each loaf there is just over three litres of ale and an astonishing 1.6 kg of meat. In total, if 150 loaves meant 150 diners, each individual meal was 5,024 kcal. Again, we probably need to be imagining ample leftovers being eaten up in the days that followed Oswulf’s anniversary. Wulfred made separate arrangements for almsgiving, ordering that 120 gesufl loaves (loaves with some sort of accompaniment) be prepared from the community’s provisions and distributed to the poor; it is possible that he anticipated leftovers being distributed in a similar way, but perhaps more likely that he envisaged them going home with guests or being absorbed by Christ Church’s kitchens. However, he also ordered that the provost (regolwarde) was to receive all the food supplies and ‘distribute them as may be most beneficial for the community and best for their [Oswulf’s and Beornthryth’s] souls’, which perhaps this implies that gifts of food were sometimes sent to important lay and ecclesiastical figures who were unable to attend in person.Footnote 48

Table 3: The content of the food list in S 1188.

Table 4: The individual meal implied by S 1188, assuming one loaf per diner.

A second clear example comes in another Christ Church text, this time dated 941 × 958. It concerns a landholding at Ickham, Kent, held by a certain Æthelweard but seemingly also claimed by Christ Church. The document records an agreement apparently intended to resolve this underlying dispute. Its terms involved Christ Church and Archbishop Oda recognising Æthelweard’s legitimate possession of Ickham; in return he bequeathed it indirectly to Christ Church, stipulating that it revert to the community after being held for a single lifetime by one of two potential heirs. That heir was to pay five pounds on inheriting the land and provide a one-day feast (ane dæg feorm) for the community every year at Michaelmas. This annual feast was to consist of ‘forty sesters of ale, sixty loaves, a wether, a flitch and an ox’s haunch, two cheeses, four hens and five pence for the table’.Footnote 49 Table 5 and Table 6 set out the results of applying our interpretative assumptions to this text. The sixty loaves imply a much smaller gathering than either the 150 at Wulfred’s feast for Oswulf and Beornthryth or the 300 specified by Ine 70.1, but the proportions are remarkably similar. There are 1.2 kg of meat and 3.3 litres of ale to go with each loaf. Assuming each loaf represents a diner, it works out at 3,905 kcal per head. Given these quantities and proportions, there can be no question that the phrase ane dæg feorm refers to a single day of feasting, not an ordinary day’s rations.

Table 5: The content of the food list in S 1506.

Table 6: The individual meal implied by S 1506, assuming one loaf per diner.

A wider comparison

To these two texts we can add another eight broadly comparable lists of food, the key characteristics of which are set out in Table 7.Footnote 50 Except for one clear outlier, to which we will come shortly, the overall picture is remarkably coherent. These food lists all tend to derive around fifty-five per cent of their total calories from animal products (the range is from forty-four per cent to sixty-two per cent). This works out as an average of 2.8 litres of ale to wash down each loaf of bread and 0.7–1.6 kg of meat, fish and dairy. Everything included, a full loaf’s ration amounts to between 3,000 and 5,700 calories. It is not just that Ine 70.1 looks remarkably like both Archbishop Wulfred’s commemorative feast and the ane dæg feorm from Ickham, all three of these texts fit a wider pattern. The most likely reason for that is that all these texts in some way represent lists of supplies for feasts. For some, like these three, it seems clear that this was their literal purpose. For others, particularly where the supplies are requested in forms more consistent with storage, it is harder to discount the hypothesis that we are dealing with feast-supply obligations where it was understood that the feasts concerned would not actually be held. However we interpret these lists, there can be little doubt that their proportions are those of feasts rather than ordinary meals.

Table 7: Comparison of eleven food lists.

Even so, it is important to sound some notes of caution. It is possible that some of the coherence of this picture is a mirage. These eight additional lists introduce three new units of volume (the mitta, cumb, and tunne) and one of weight (the wæge), none of which can be interpreted with any great certainty. Our assumptions on these are detailed in Appendix 1. Given the lack of information to go on, our estimates are unlikely to be very accurate but they were arrived at independently of our conclusions so if they are conspiring to create a false sense of coherence that is just bad luck. A significantly more problematic interpretative issue arises from the fact that many of these lists request not ale but the malt from which it could be brewed. The ale-per-loaf figures marked with an asterisk in Table 7 assume that ‘an amber of malt’ is a shorthand for ‘an amber’s worth of malt’: that is, ‘enough malt to make an amber of ale’. This is a plausible enough theory (later Welsh texts may do something similar with honey and mead)Footnote 51 but the only strong reason to think it accurate is that it yields a coherent result. Interpreted this way, the amounts of ale per loaf of bread implied by the texts that specify malt are broadly in line with the amounts in lists where it appears in its brewed form.

However, the alternative interpretation, that an amber of malt is literally an amber of malt, deserves to be considered seriously. The only obstacle to accepting this more straightforward interpretative assumption is that it produces much larger ale-per-loaf values in lists that specify malt. If we were to assume an amber of malt actually meant fifteen litres of malt, enough to make (very approximately) thirty-six litres of ale, our most ale-heavy food lists (mid-ninth-century Kentish grants concerning lands at Mongeham and Nackington) would be allowing nine to eleven litres of ale to go with each loaf.Footnote 52 In stark contrast, lists which ask for ready-brewed ale imply quantities per loaf ranging from 1.5 to 3.3 litres. The fact that these food lists are broadly similar in all other respects, and mostly emerge from the same ninth-century Kentish context, is reason enough to suspect that they were conceived as supplies for similar events, so it is a distinct possibility that this wide variance is an illusion and we are actually dealing with the shorthand suggested here. But there is an alternative explanation. It is possible that our texts reveal the emergence of a standard rate of commutation, in which farmers customarily rendered an equivalent amount of malt to the quantity of ale that was in fact required. This might make sense as a mutually beneficial trade off. The people providing the food were spared the labour of brewing large quantities of ale in return for rendering more malt, while the recipients got the raw materials for larger quantities of ale at the cost of having to brew it themselves. If this was a convenient arrangement all round, and becoming standard, it would explain the pattern we see in these texts. We could then wonder whether the minsters that received malt in lieu of ale chose to brew all of it and throw feasts with larger amounts of ale than had hitherto been customary, or whether they opted to reserve some of what they received for internal consumption.Footnote 53 The hypothesis that some of the lists that specify malt reflect a broader orientation towards storage, and therefore represent supplies rendered in lieu of a traditional feast, also needs to be considered.Footnote 54 It is possible to imagine situations in which neither the people with feast-provision obligations nor the religious houses endowed with feast-taking rights were interested in literally holding a feast, and it made most sense for the customary feast provisions to be used as general-purpose food supplies.

As the issues surrounding malt make clear, interpreting the texts in Table 7 is a complex business. Some hint strongly at a context of commemorative feasting similar to that underlying Archbishop Wulfred’s arrangements for celebrating Ealdorman Oswulf’s anniversary.Footnote 55 But as a general rule, as we shall see shortly, testators who sought to endow annual commemorative feasts at monasteries seem to have trusted their heirs and the religious houses to work out the details. There is therefore reason to think that some unusual and possibly complex circumstance lies behind our cluster of Kentish texts in which specific supplies are listed. Of course, each of these texts needs to be analysed in detail on its own terms, which is not possible here. For present purposes, what matters is the pattern running through these food lists. In each case, the proportions of bread, ale and animal products show that they were conceived as feast supplies. The question of how they were used in practice may be open to debate – some of the malt renders are perhaps open to being read as ‘supplies rendered in lieu of a customary feast’ – but it is clear that these food lists are shaped by a shared set of catering assumptions specific to feasts, which differed markedly from ordinary meals. The vast scale and animal-protein-heavy proportions of the food list in Ine 70.1 are thus not as outlandish as they may seem at first sight. These features are exactly what we would expect in a list of feast supplies. Indeed, the only way in which Ine 70.1 stands out is in its inclusion of fish and eel, which are absent elsewhere except when religious dietary restrictions are explicitly at issue; this should probably be taken as evidence of ecclesiastical involvement in its drafting.Footnote 56

THE LANGUAGE OF FEORM AND PASTUS

Commemorative feasting in minsters

This leaves the issue of Ine 70.1’s representativeness. Establishing its identity as a feast-supply list is one thing; demonstrating that our many other references to kings receiving feorm or pastus likewise refer to feasts is a bigger task. Yet evidence supporting this wider contention comes thick and fast as soon as one starts looking for it. They can refer to sustenance in an everyday sense, consistent with their interpretation as allusions to routine ‘food rents’, but they can also refer specifically to feasting.Footnote 57 So when a will or charter specifies that a feorm be delivered to a religious house, we can legitimately interrogate whether a feast is at issue. This is not something that translators have hitherto tended to do, presumably because the idea that feorm represents a render of general-purpose food supplies has been such an integral part of established interpretative frameworks. It seems only to be when a ‘food rent’ translation is self-evidently nonsensical that the alternative of ‘feast’ has been considered.

For example, in a 934 charter we find King Æthelstan giving fifty hides to the monks of Winchester’s Old Minster and asking that they gefeormian themselves for three days every year at All Saints’ for his sake.Footnote 58 This has long been recognized as a reference to an annual feast rather than a bizarre demand that the monks somehow pay themselves a ‘food rent’, but this makes it an exception.Footnote 59 A more typical example of the way references to feorm in such contexts have been read is the 1015 will of Æthelstan Ætheling, which establishes ane dægfeorm for the community at Ely on the feast-day of St Æthelthryth.Footnote 60 Dorothy Whitelock translated this as ‘one day’s food rent’, explaining in her notes that ‘a day’s feorm was the gift of food considered sufficient for the community for one day’.Footnote 61 A celebratory day-long feast is a more credible interpretation, given the context. And we have already seen, of course, that ane dæg feorm in our Ickham text refers to a day of feasting.

Indeed, there is a strong pattern of testators asking their heirs to use some of the fruits of their inheritance to provide annual feorme to religious houses. The voluntary nature of some of these makes it plain that these feorme are feasts, not generic food rents. The will of Wulfwaru, probably dating 984 × 1001, asks that her various heirs ‘all together provide ane feorme at Bath each year forever, as good as ever they can afford, at such season as it seems to all of them that they may accomplish it best and most fittingly’.Footnote 62 Similarly, in his mid-ninth-century will, Badanoth Beotting asked his family to gefeormian the community at Christ Church on his anniversary ‘as best they can afford’ (sƿæ hie soelest ðurhtion megen), and he requested after their deaths ‘that the person to whom the community bestows the land shall fulfil the same condition for providing a feast on my anniversary’.Footnote 63 It is probable that all the annual feorme we find being newly established in documents where no food-list is provided refer to commemorative feasts of this sort, and not to the general-purpose ‘food rents’ that have traditionally been supposed. The consistent lack of specificity about what was to be rendered makes very little sense in documents establishing new rents, but fits well with a scenario in which testators were asking their heirs to provide commemorative feasts and felt they could rely on them to decide what was fitting.Footnote 64

The established assumption that the reverse is true appears to derive from a back-projection of monastic administrative documents from the eleventh century and beyond, in which responsibility for delivering a community’s annual food supplies is divided among its landholdings, with individual vills assigned ‘farms’ defined by fixed time periods.Footnote 65 The twelfth-century Liber Eliensis attributes the establishment of Ely’s system of farms to Abbot Leofsige (1029–?1044).

With consent and approval of the king himself, he also instituted a system of designating sources of firma which would be sufficient throughout the year for the supplying of food for the church, and, for preference, sources of firma chosen from among the villages and lands which, by their more than usually abundant sweetness and exceptionally rich turf, are recognized as productive of crops.Footnote 66

The text then assigns farms to thirty-four of the abbey’s holdings, mostly in units of one or two weeks, though in one case a single week’s firma was split into separate three- and four-day units. It is easy to see how familiarity with the three-day firma owed by Ely’s holding at Swaffham Prior in Cambridgeshire, where general-purpose food supplies are clearly at issue, could have encouraged the idea that references to feorm in units of one to three days are allusions to similar supply systems. But firma in this context is evidently not being used in the same sense as feorm and feormian in the examples from charters and wills just surveyed. To establish that this distinction holds in all cases we would need to look at each text in turn, which is not practical here, but there is also a basic issue of plausibility. A few days of ordinary rations would be a remarkably meagre gift for a noble benefactor to bestow on a monastery. Though this is a viable interpretation of references to feorm in texts describing religious houses’ internal administrative arrangements, in gift-giving contexts there is a strong prima facie case for three-day feorme meaning three-day feasts.

Feasts in recognition of authority

Recognizing this, of course, has knock-on effects for our reading of the smaller corpus of references to the king’s right to ‘one night’s feorm’, for which a parallel argument can be made. Deep-rooted historiographical tradition notwithstanding, is it really plausible to imagine that it made administrative sense to divide the royal household’s food supplies into twenty-four-hour units? The monastic evidence suggests that blocks of months and weeks were the natural basis of general-purpose food-supply systems.Footnote 67 Given that ane dæg feorm refers to a day of feasting in a wide range of aristocratic wills, is it not likely that the king’s feorm of one night originally referred to a night of lavish feasting, rather than a single day’s ordinary food supplies?

The usage of the Latin term pastus in earlier texts offers support to this reading, though the term itself is a little more ambiguous. It is likely to be a Latin rendering of feorm, but only in the general sense of sustenance or hospitality; it is not a word that can directly be translated as ‘feast’. For the most part, charters that mention pastus do so only in passing, in the context of exempting their beneficiaries from having to provide it, and these offer few clues as to its meaning, though they do suggest that it was claimed not just by kings but also bishops and ealdormen. Nonetheless, when Offa of Mercia, in the context of a dispute settlement, remitted three years of the pastiones to which he was entitled from the church of Worcester in 781, his charter explained that this amounted to six convivia, ‘feasts’.Footnote 68 A charter of 904 helpfully fleshes out the ancillary obligations of hospitality associated with this duty. As well as providing the king with pastus unius noctis, the minster at Taunton had, prior to its liberation in this charter, been obliged to provide pastus for eight dogs and their keeper, and nine nights of pastus for the king’s falconers.Footnote 69 The word pastus is conveying different things in these contexts. The king’s one night of pastus at Taunton is, presumably, the equivalent of one of the six convivia that made up the king’s three years’ pastus at Worcester. It is reasonable to suppose that pastus (‘sustenance’) in this context maps onto the foster (‘sustenance’), in the form of a feast, that Ine 70.1 specified from ten hides. But the nine nights’ pastus to which the king’s falconers were entitled, and the pastus received by the king’s kennelman and his eight dogs, must be sustenance in the sense of ordinary food and lodging, as these relatively lowly figures cannot have expected convivia to be held for them every night.

It is conceivable that the two senses are more closely associated than they first appear, if feasts were associated with hunting trips and various royal servants needed to arrive well in advance to prepare for the main event.Footnote 70 Yet an allowance of nine nights seems excessive for this practical context, and the precision about timings is redolent of a series of ninth-century Mercian charters which suggest that kings had grown used to stretching the limits of their entitlement to hospitality by lodging their huntsmen, falconers, dog-keepers and various hangers-on in religious houses for sustained periods. These documents are particularly keen to establish exemption from the importunities of ‘those who in English we call fæstingmen’ (perhaps a general term denoting men kings committed to others’ hospitality) and to set precise limits on hospitality obligations to foreign travellers and emissaries. The pastus of these charters is probably a rendering of the Old English term cumfeorm, ‘visitor-hospitality’, used in one of them, and only tangentially related to the obligation to provide pastus directly to kings in the form of a convivium or feorm. Footnote 71 This is a term that could encompass quite distinct forms of ‘hospitality’ or ‘sustenance’ that can only be disentangled with particularly close attention to the contexts in which we find it.

The list of foods Offa reserved from Westbury-on-Trym, Gloucestershire, in the 793 × 796 charter noted earlier, may be helpful here (its contents are analysed alongside the feast-supply lists in Table 7). This is the relevant section:

We enjoin in the name of the supreme God that it is to be released from all compulsion of kings and ealdormen and their subordinates except these taxes; that is, of the tribute at Westbury, two tunnan full of pure ale and a cumb full of mild ale and a cumb full of Welsh ale, and seven cattle and six wethers and forty cheeses and six long þeru and thirty ambers of unground corn and four ambers of meal, to the royal estate.Footnote 72

The striking thing about this list is that it cannot represent just one feast. Though there is some ale that would have needed drinking quickly and some meal ready for baking, the bulk of the cereal portion of the list is raw grain. These numbers are rough – we have little to go on when estimating the capacity of the cumb or tunne and have had to omit the impenetrably obscure ‘long þeru’ – but the probable implication is that somewhere in the region of 300 litres of ale and 178 loaves of bread would form the basis of an immediate feast, along with some of the cheeses and livestock.Footnote 73 Meanwhile, the thirty ambers of raw grain and the remaining cheese would be stored, and the uneaten livestock would be allowed to graze until the time came for them to be slaughtered.

We cannot know whether Offa intended this surplus food to supplement his household’s ordinary diet or if he envisaged using it to hold further feasts. But we can say that the overall proportions of this food list suggest that however the food was ultimately used it was originally conceptualized as a list of feast supplies. Approximately fifty-seven per cent of its total calories derive from animal products, a figure that fits a feasting context perfectly but, as the isotopic data shows, does not correspond to the make-up of any early medieval household’s ordinary food consumption.Footnote 74 It is probably safe to infer that this list approximates what would have been eaten at some of the convivia which the free households of the sixty hides at Westbury were obliged to provide for the king. Unfortunately, we can only speculate as to how many convivia Offa was reserving, or how much food a single convivium required. The meal and ale listed in the charter give us a rough sense of the size of the feast that was planned for the point when the food was delivered to the royal tun, but it is not safe to assume that this event equates to a single convivium held at Westbury before its alienation. Moreover, it is unlikely that the supplies Offa reserved represent the entirety of his entitlement from these sixty hides.Footnote 75 The point of the document was probably to transfer some of the king’s pastus rights to Worcester while retaining what Offa felt he needed. If the farmers of Westbury theoretically owed six convivia each year, one for each set of ten hides, Offa may well have decided to split them equally, reserving three for himself while granting the remaining three to Worcester (this would account for the fact that Offa’s render amounts to approximately 52,000 kcal per hide, under half the 124,000 kcal that Ine 70.1 was demanding from West Saxon hides). We know that Mercian kings of this era sometimes divided their feorm entitlements in this way because of an 883 charter in which Ealdorman Æthelred of Mercia granted Berkeley Abbey, also in Gloucestershire, ‘remission forever of the tribute which they are still obliged to pay to the king, namely that portion of the king’s feorm which was still left unexempted, in clear ale, and in beer, in honey, bullocks, swine and sheep’.Footnote 76

It may be that Mercian kings were keen to retain their rights to receive at least some feasts from the lands they ruled, particularly in frontier regions like Gloucestershire, because these events were vested with symbolic significance. In non-royal contexts, pastus seems to refer to a form of hospitality that signified recognition of the legitimate claims of a higher authority. In 803, the bishop of Worcester successfully claimed two disputed minsters by demonstrating that they had provided pastus to his predecessors, and by asserting that money he himself had received from his adversary, the bishop of Hereford, had been paid in lieu of pastus. Footnote 77 A decade or so earlier, the abbot of Peterborough granted land to an ealdorman on an indefinite, heritable lease, on the condition that he and his heirs annually recognize the abbey’s rights with unius noctis pastus or, again, with a monetary payment in lieu.Footnote 78 This is exactly how the term feorm is used in some later documents. The one-day feast (ane dæg feorm) Archbishop Oda secured at Ickham when he resolved Christ Church’s dispute with Æthelweard in the mid-tenth century should perhaps be understood as the equivalent of this earlier unius noctis pastus, an annual recognition of the monastery’s lordship.Footnote 79 A similar situation is discernible a generation later, when a series of religious bequests by a Kentish nobleman named Ælfheah were challenged by his disgruntled kinsmen. It seems they asserted he did not own the lands he had bequeathed and relied on the fact that he had not ‘taken feorm’ from the lands in question to back up this contention. Our Rochester source tells us that this was technically true for two of three landholdings (conveniently, Ælfheah had in fact taken feorm from the one destined for Rochester) but insists that the argument was refuted by Archbishop Dunstan. It was explained that the fact Ælfheah had not taken feorm from all of them was of no significance. He had recently resumed possession of these formerly leased lands and had of course intended to take feorm from them, but had fallen ill and died before he got round to visiting all three.Footnote 80 Helpfully, this demonstrates that in late tenth-century Kent ‘taking feorm’ was something that was done in person, which suggests a feast rather than a ‘food rent’, just as the Ickham text demonstrates that ane dæg feorm was supplies for a day of feasting rather than a day’s ordinary fare. These texts all seem to be pointing towards a culture in which it was conventional for people with rights over land occupied by others to assert these rights performatively by receiving a symbolically significant meal, a one-day feast whenever we get details.Footnote 81

POSSIBLE IMPLICATIONS

On close inspection, then, our textual evidence – both the lists of food and the references to feorm and pastus – offers surprisingly little support to the traditional vision of a system of food renders. Free peasants do seem to have been obliged to give their kings food, but we should not imagine that it was traditional for them to render up the general-purpose food supplies on which royal households subsisted. What they customarily provided seems to have been a night of feasting, at which the food served was radically different from ordinary fare in both quantity and type. Estimates of quantity depend on the idea that the ‘loaves’ in our supply lists are, as all the evidence suggests, small round buns, and that the people organizing the catering for feasts tended to allow one such bun for each person they expected. If this is right, our supply lists show that in both royal and ecclesiastical contexts early medieval caterers believed a total of around 4,000 kcal of food and drink was an appropriate per capita allowance for a feast. But even if this assumption is faulty, it is still clear that the people who framed our supply lists tended to allow roughly a kilogram of meat for each small round bun they requested.

As we have shown in this article’s companion piece, these proportions stand in stark contrast to what royal households are likely to have eaten every day. The isotopic data suggest that ordinary diets involved only low to moderate amounts of meat, fish and dairy, and they also show that early medieval elites did not seek to distinguish themselves from their social inferiors by consuming more animal protein than the norm. Across the social spectrum, normal meals were cereal-based meals. We should imagine people livening up loaves of bread with small quantities of meat and cheese, or eating them alongside pottages which contained some animal products but were bulked out with leeks (seemingly the period’s staple vegetable) and whole grains.Footnote 82 These feasts, by contrast, involved oxen being roasted in pits.Footnote 83 Indeed, meat was in such plentiful supply that everyone present could have decided to shun bread entirely and still be left uncomfortably full. These were not just events at which everyone ate a great deal, they involved an ostentatious inversion of the normal relationship between animal- and plant-based foods.

This difference reflected these feasts’ status as symbolically significant occasions, at which legal and political claims were formally registered and recognized. A big part of what made them special would, presumably, have been the large numbers of people present. The 300 loaves of Ine 70.1 suggest 300 attendees, and our tentative figure of 178 loaves for Offa’s initial Westbury feast is probably a significant underestimate.Footnote 84 These high numbers align well with those implied by later feast-supply lists but seem implausibly large for early royal households, and probably imply that many of the people who attended these events were drawn from the local area. The presence of large numbers is likely to have been a major part of what gave these events their symbolic weight, public acts of recognition ideally needing to be performed before large groups of people. The corollary of this is that such feasts must have been interspersed with many days on which royal households ate less acutely symbolic meals in relative privacy. This daily fare must mostly have come not from free peasant levies but from the king’s own farms.Footnote 85

This finding carries implications for our understanding of royal ‘inlands’ and ‘home farms’, but they are not as great as one might assume. The idea that royal households primarily ate food produced on the king’s own lands does not require us to imagine particularly vast royal landholdings. The king owned twelve per cent of Domesday England’s land by value in 1066.Footnote 86 Even if King Ine owned outright just one per cent of early eighth-century Wessex’s approximately 17,000 hides he would not have struggled to feed even a huge, 200-person household from his own landholdings.Footnote 87 Assuming a single hide can support a family of four to six people, feeding 200 people would have required thirty-three to fifty hides. These royally owned hides would have needed to support their labour forces (perhaps primarily slaves and the reeves who oversaw them) as well as the king’s household, so we need to allow considerably more than this, but probably not as much as 170 hides. To put it another way, if we assume that each of the 200 people in this hypothetical and implausibly large royal household ate two loaves of bread a day, the king would require 146,000 loaves per year, which works out as approximately 36,600 litres of wheat. In later medieval units, this is about 1,040 bushels: roughly the amount of wheat a thirteenth-century lord could expect to reap from 114 acres of demesne arable.Footnote 88 Seventh-century arable yields per acre could have been lower, and this figure does not account for the significant chunk of the harvest it would have been necessary to set aside as seed corn, but these calculations at least serve to make the point that it is easy to overestimate the scale of the agricultural operations necessary to meet the dietary needs of large elite households.Footnote 89

The implications for engrained historiographical assumptions about the existence of a cultural gulf between the upper elite and the peasantry are probably rather more significant. Reimagined along the lines proposed here, royal household life has a surprisingly down-to-earth flavour. Rather than a distant elite engaged in a constant round of carousing at the expense of the peasantry – le festin permanent, as Alban Gautier puts it – we are given an image of royal households mostly eating a similar cereal-based diet to everyone else, but occasionally attending feasts for hundreds of people where they mingled with local free farmers, who sought to honour them by culling and roasting their elderly wethers and plough-oxen.Footnote 90 This is not to say that kings only ever ate to excess on such grand public occasions. Smaller, elite-only feasting was probably a part of royal household life too, though the isotopic evidence suggests lavish meat-consumption remained an occasional treat even in such elevated social circles.Footnote 91

This revised understanding of life in royal households necessitates a shift in our approach to the institution that our sources term feorm and pastus. This institution has hitherto been understood in primarily economic terms as early kingdoms’ main fiscal mechanism and, in non-royal hands, the root from which a rent-seeking aristocracy grew its property rights. But when we appreciate that occasional feasting is at issue rather than regular transfers of resources it becomes apparent that feorm was less economically central than has often been assumed. And this serves to highlight that pastus and feorm had a cultural and symbolic significance that the historiography has barely begun to explore. Rosamond Faith and Thomas Charles-Edwards are exceptional in having given sustained attention to the honourable connotations of the language of hospitality with which contemporaries framed this institution, but efforts in this direction have inevitably been limited by exploitative economic realities of food renders, as traditionally understood. This imagined system clearly involved, as Faith puts it, ‘the expropriation of the poor to feed the powerful’, and if it had existed contemporaries would of course have been capable of seeing through the cosy metaphors used to legitimize it, recognising the institution for what it was.Footnote 92 It is understandable that historians working within the ‘food renders’ paradigm have been reluctant to attribute too much significance to this evidence of contemporary conceptualizations, tending to interpret it as a linguistic hangover from a more egalitarian past. But the problematic tension evaporates with the recognition that hospitality was not just a convenient metaphor but a living reality, in which land-owning peasants collectively played host to visiting royal households at grand feasts. All the points Charles-Edwards and Faith make about the social and political meaning of these gifts of food are thus greatly reinforced. But it also becomes apparent that their efforts have barely scratched the surface. We have a rich body of textual evidence for an enduring institution of large-scale symbolic feasting – our dozen or so food lists and a plethora of documents that refer to feorm and pastus – which has been construed in exclusively economic terms, as though it referred to ‘food rents’ that supported ordinary diets and had no more cultural significance than any other form of elite surplus extraction. As the brief discussion of this evidence here has shown, we can get a lot more out of these texts once we escape this framing. We glimpse a world in which annual feasts for hundreds of people were held both to commemorate the dead and to recognize lordship, well into the tenth century and indeed beyond.

The traditional model of food renders occupies such a foundational historiographical position that the implications of revising it in this way are likely to prove far reaching once this body of evidence has been worked through carefully. This is particularly clear for interpretations of regiones, the small territories that appear to have been the political building blocks from which kingdoms were constructed. Tributary arrangements are central to most framings of these early units. But if food renders did not exist in the way traditionally assumed in the seventh and eighth centuries, there is no reason to imagine they were a defining feature of fifth- and sixth-century regiones. This should push us to think through alternative ways of imagining these territories.Footnote 93 We might, for instance, wish to consider the possibility that the main locus of economic exploitation in the fifth and sixth centuries was the peasant household, and to recognize more fully that the heads of free households occupied a privileged social and economic position. As the owners of land, livestock and probably often slaves there can be no question that, as a group, free householders controlled the means of production. When we bear this in mind the image of free peasants hosting kings at feasts seems rather less surprising.

Is it possible that the concept of food renders has obstructed our view of the political and social realities of this early period, leading us to miscast this dominant class of free landowners as the exploited victims of emergent kings and a new sword-wielding elite? An alternative model, perhaps, would see the forerunners of later sixth-century kings as fifth-century political leaders who were able to assemble and hold together confederations of regiones, allowing the land-owning farmers of multiple territories to act collectively to defend and advance their common interests. Such a model would have the virtue of explaining the many signs that the Germanic-speaking settler societies of this era were able to undertake large-scale political action: not just the consistent emphasis on military confrontation in our written sources, but also the series of massive linear earthworks in Cambridgeshire that date to this period.Footnote 94 The currently dominant model, which imagines hundreds of tiny kingdoms emerging and jockeying for position with their immediate neighbours, has always been in tension with these indicators of a deep-rooted tradition of political cooperation on a scale far greater than that of the regio.

It will be even more complex to work through implications of replacing royal food renders with a practice of symbolically significant feasting in later periods. A central question is how kings sought to exploit their feasting rights across the centuries. Late eighth- and ninth-century Mercian charters, in particular, have much to tell us here, and by the late eleventh century it is apparent that the right to the ‘farm of one night’ had been monetized on an astonishing scale. In much of Wessex, a single ‘night’s farm’ was valued at approximately £100 in 1086. It is worth dwelling on this for a moment, as the sheer size of these sums deserves fuller recognition than it has hitherto received. £100 is 24,000 pence. In terms of livestock, this would have bought 800 bullocks at the usual price of thirty pence per head, or 4,800 sheep at five pence per head.Footnote 95 We have no reliable information on grain prices for this period but in the 1170s a ‘quarter’ of wheat, a unit of volume of roughly 280 litres, would on average have cost roughly two shillings, or twenty-four pence.Footnote 96 A century after Domesday Book – a century of population growth in which food prices are perhaps more likely to have inflated than deflated – £100 would have bought maybe 280,000 litres of grain, approximately 220 tons by weight. If it was spent solely on grain, the West Saxon ‘farm of one night’ of approximately £100 would theoretically have yielded 728 million kcal, enough to provide a daily ration of 2,000 kcal to 364,000 people. Spent on solely on beef, the equivalent figure is 68,000 people; for mutton, 44,000 people.

The massive scale of these ‘night’s farm’ payments must have been the product of a long development process. It will be difficult to unpick this but recognising that the feorm of one night began as a feast rather than a food render may prove helpful. Domesday values for ‘the farm of one night’ vary from shire to shire in a way that aligns suggestively with what we know about where kings spent most of their time.Footnote 97 This makes some sense if we understand these figures as resulting, at least in part, from an original right to receive feasts that was commuted in multiple stages. It would not be surprising if, in practice, the obligation to host a feast was commuted for a lot of money in places where royal households regularly turned up and claimed their rights, and for relatively little in places where this duty of feast-provision was a largely theoretical burden. Domesday patterns can help us theorize how this might have happened, while our scattering of textual references offer us opportunities to glimpse how far the processes of commutation had progressed in different times and places. There is a complex story to be told, in which kings continued to hold the right to receive literal feasts in some locations even in the eleventh century – the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle entry for 1006, of course, has King Æthelred travelling to Shrewsbury to ‘take feorm’Footnote 98 – even while they were commuting their feast rights for large sums of money in other areas.

The recognition that the king’s feorm was originally a feast also bears on debates about the progress of manorialization. Most obviously, it casts doubt on the hypothesis that lords who were given the right to receive the king’s feorm or pastus could easily intensify these obligations or reframe them as rents. As was noted above, this idea relies in part on Maitland’s observations about a possible conceptual slippage, by which public obligations in recognition of ‘superiority’ were, in private hands, readily conflated with rents. But the theory that feorm obligations were, in practice, difficult to distinguish from annual rents paid in kind is difficult to sustain if one understands the king’s right to feorm as the right to receive feasts. Maitland’s point about the conceptual slippage remains valuable, but we can now appreciate that confusion between feorm obligations and rents paid in kind was only likely to arise once the duty to provide food for a feast, should a king or lord turn up to claim one, had been commuted into a more convenient annual payment. Such commutations would perhaps have made good economic sense for all parties. If they were enforced regularly, feast-supply obligations would have constituted a significant burden for peasants, while providing only a minimal direct benefit to lords. Some farmers may have gladly committed to moderate cereal-based payments in return for the relief of the annual duty to slaughter livestock for a feast.Footnote 99 It is possible that such decisions had unforeseen consequences for subsequent generations, when lords began to insist that receipt of such customary payments signified ownership. Developments of this type can be shown to have happened in the wake of the Norman conquest and they may have taken place earlier, though they are impossible to track in the surviving evidence.Footnote 100

Where the recognition that feorm originally involved feasting may be particularly valuable is in highlighting the fact that the initial stage in the model just outlined, in which the obligation to provide a meat-heavy feast is commuted for an annual grain-based render, should not be taken for granted. Even in the tenth century it is possible to catch glimpses of lords receiving feorm in contexts that imply a literal feast is at issue. Ælfheah, the lord mentioned above who died before he got round to ‘taking feorm’ from his disputed landholdings, is a particularly clear example, and the dispute his death provoked seems to reflect an assumption that lordship over land needed to be recognized through feasting in late tenth-century Kent.Footnote 101 And in the first decade of the tenth century we can see something similar in Surrey. It appears that the residents of the sixty-hide landholding at Beddington were accustomed to holding an annual feast to recognize the lordship of the bishop of Winchester.Footnote 102