In the tablets of the Sulpicii there are 76 instances of apices (Table 38).Footnote 1 27 of them are on personal names. In the TPSulp. tablets, as at Vindolanda, apices feature particularly in parts of the tablets written by the scribes (Reference CamodecaCamodeca 1999: 39): out of 76 instances of apices, 74 are found in scribal parts, with the remaining two coming from the chirographum of A. Castricius (deductá 81, repraesentátum 81). This divide between scribes, who use apices, and individual writers, who mostly do not, suggests a difference in education for the purpose of writing, as at Vindolanda.

Table 38 Apices in the tablets of the Sulpicii

| Apex | Text (TPSulp.) | Writer |

|---|---|---|

| Hósidio | 1 | Scribe |

| 1bis | Scribe |

| Faustó | 2 | Scribe |

| 3 | Scribe |

| 16 | Scribe |

| 18 | Scribe |

| noná | 19 | Scribe |

| 27 | Scribe |

| 32 | Scribe |

| Áug(–) | 33 | Scribe |

| 34 | Scribe |

| chalcidicó | 35 | Scribe |

| 40 | Scribe |

| 45 | Scribe |

| 47 | Scribe |

| 50 | Scribe |

| 51 | Scribe |

| Galló | 55 | Scribe |

| mé | 57 | Scribe |

| Alexándrì | 58 | Scribe |

| Áfro | 68 | Scribe |

| [Q]uártìónis | 77 | Scribe |

| 81 | A. Castricius |

| 82 | Scribe |

| Márius | 84 | Scribe |

| Tróphi | 110 | Scribe |

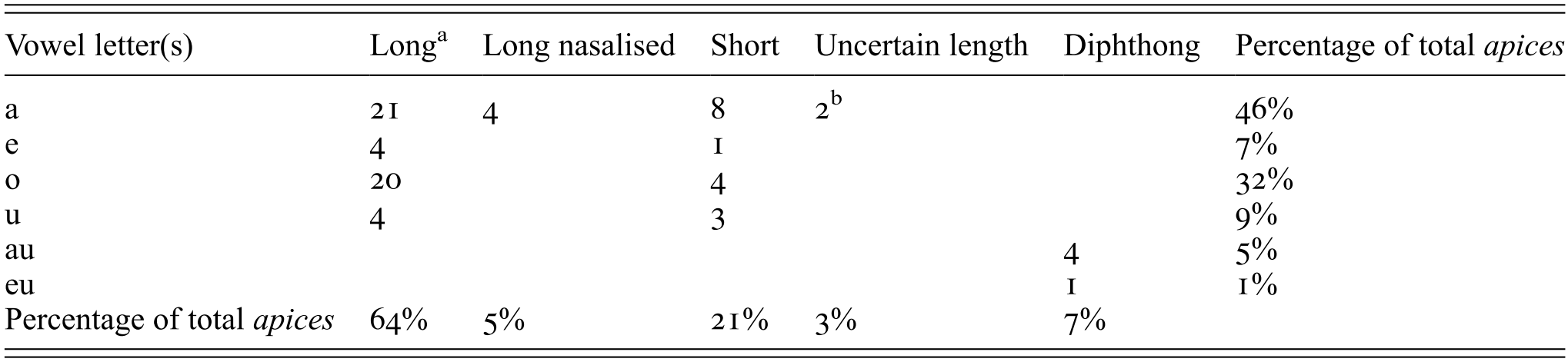

In the tablets of the Sulpicii, as at Vindolanda, a and o also make up a large percentage of all letters with apices (78%), as observed by Reference CamodecaCamodeca (1999: 39). But e and u make up a greater percentage of cases than at Vindolanda, and au and eu are also found with apices, unlike at Vindolanda (see Table 39).

Table 39 Distribution of apices by vowels and diphthongs in the tablets of the Sulpicii

| Vowel letter(s) | LongFootnote a | Long nasalised | Short | Uncertain length | Diphthong | Percentage of total apices |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | 21 | 4 | 8 | 2Footnote b | 46% | |

| e | 4 | 1 | 7% | |||

| o | 20 | 4 | 32% | |||

| u | 4 | 3 | 9% | |||

| au | 4 | 5% | ||||

| eu | 1 | 1% | ||||

| Percentage of total apices | 64% | 5% | 21% | 3% | 7% |

a Including [aː] by lengthening before coda /r/ in [Q]uártìónis.

b There are two cases where I do not know the vowel length: the first vowels of Páctu[m]eìám, Pátulci.

The proportion of apices on long vowels is surprisingly small. I assume that originally long final vowels have not been shortened and that lengthening has taken place before coda /r/. Not including the two vowels of uncertain length this means that only 49/74 = 66% apices are on long vowels, with a further 5 on diphthongs. However, there are 4 instances of an apex on an originally short vowel in the accusative singular ending (acceptám 27, arám 16, [Ho]rdionianám 40, Páctu[m]eìám 40). This is likely to have become [ãː] before the first century AD (Reference AdamsAdams 2013: 128–32), and the scribes may have therefore considered it a long vowel. This takes us to 72% (53 apices on long vowels out of 74).

The final syllable is a favoured site for the apex, with 35/71 (49%) of relevant apices on a final syllable (there are also two monosyllables, and three abbreviations).Footnote 2 Reference CamodecaCamodeca (1999: 39) links this concentration on final syllables to Adams’ explanation of the preference for final position at Vindolanda as reflecting shortening of word-final long vowels. However, of these 35, 26 are on original word-final long vowels, 4 are on final /ãː/ represented by <am>, 4 are on long or short vowels followed by /s/, and only 1 is on a short vowel, the ablative nominé (3.2.7). There are 10 instances of an apex on long word-final /aː/ (not including [ãː]), and none on word-final /a/. This suggests that the scribes were able to tell these sounds apart; there is practically no evidence for shortening of final long vowels, so it seems unlikely that the placement of apices on final syllables is to be explained in this way.

Outside final syllables, the picture is much more mixed. Omitting monosyllables, and abbreviated names, and the 2 instances where I do not know the vowel length, there are 36 cases of an apex on a non-final syllable, of which 11 are on a short vowel, 2 on a diphthong and 21 on a long vowel (including the vowel in the first syllable of [Q]uártìónis). It is possible that there is a correlation here between stress and position of the apex, and the numbers of examples are slightly greater than at Vindolanda, which provides a little more confidence.Footnote 3 The key evidence for such a correlation is in short vowels, which do not in themselves draw the accent, as long vowels and diphthongs do. For the short vowels, 9/11 = 82% instances of the apex fall on the stressed syllable (exceptions are chirográphum, Hósidio);Footnote 4 this is suggestive of a correlation between stress and apex placement, although not completely conclusive, especially since regardless of the length of the vowel, the (initial) apex cannot be on a stressed vowel in Páctu[m]eìám and Pátulci. Including diphthongs and long vowels gives us a total of 27/36 = 75% of apices on non-final syllables that fall on stressed syllables.

However, this correlation does not provide evidence for lengthening of vowels in open syllables at this period, a change which took place on the way into Romance, and which may have already occurred by the third century AD in at least some varieties of Latin, with perhaps some occasional evidence for its occurrence earlier (Reference LoporcaroLoporcaro 2015: 18–60; Reference AdamsAdams 2013: 43–51, note in particular footnote 11). This is because, of the short vowels with an apex under the accent, only 6/9 are in an open syllable (ágitur, chirógraphum, háberet, Márius, Tróphi, D]ióg[e]nis vs Alexándrì, ánte, tánt[am]). So it looks as though, if the correlation with the accent is correct, it is the position of the accent that is being marked, rather than stressed long vowels. Within the word, only about a third of the examples of an apex occur on a long vowel. This may be due to a tendency to mark with an apex vowels or diphthongs which were stressed, regardless of whether they were long or not.

In conclusion, the scribes in the tablets of the Sulpicii tended to use apices in two different ways which are unique to them: in final syllables they were usually placed on long vowels (including long nasalised vowels); in non-final syllables they tended to be placed on stressed syllables.