At a Community Security Council (Conselho Comunitário de Segurança, CONSEG) meeting in a low-income, majority-Black district of São Paulo, a man thanked the Council for its assistance with closing an alley that had been a hotbed for crime. He praised the CONSEG for providing an opportunity to bring this demand directly to municipal and police authorities, who resolved a concern that had long plagued his residents’ association. “Come to the CONSEG, because you’ll get things done” (vai no CONSEG, que você consegue), the man assured attendees before thanking the CONSEG again for “helping the community.”Footnote 1

However, not everyone viewed the district’s CONSEG as a site for democratic voice and responsiveness. The leader of a cultural organization for Black youth recalled attending CONSEG meetings to address the police’s repressive treatment of youth with the commander, to no avail. “That place is repugnant, [it] should be exterminated. The CONSEG brings together everything that’s bad, prejudiced. It’s the police together with society, with authorized repression.”Footnote 2

These accounts highlight a fundamental paradox between democratic participation and policing. For some, formal spaces for participation in policing can expand their citizenship rights by providing access to the state and fomenting government responsiveness—a perspective consistent with democratic theorists who hail the potential of citizen participation to deepen democracy (Dryzek Reference Dryzek2000; Fung and Wright Reference Fung and Wright2003; Landemore Reference Landemore2020; Pateman Reference Pateman1970). Yet for marginalized groups, expanded opportunities for citizen participation in policing often generate demands for their repression, thereby contracting their citizenship rights. We contend that democratic participation in policing often engenders these contradictions, producing asymmetric citizenship: when expanding rights for some citizens is achieved through contracting others’ citizenship rights.

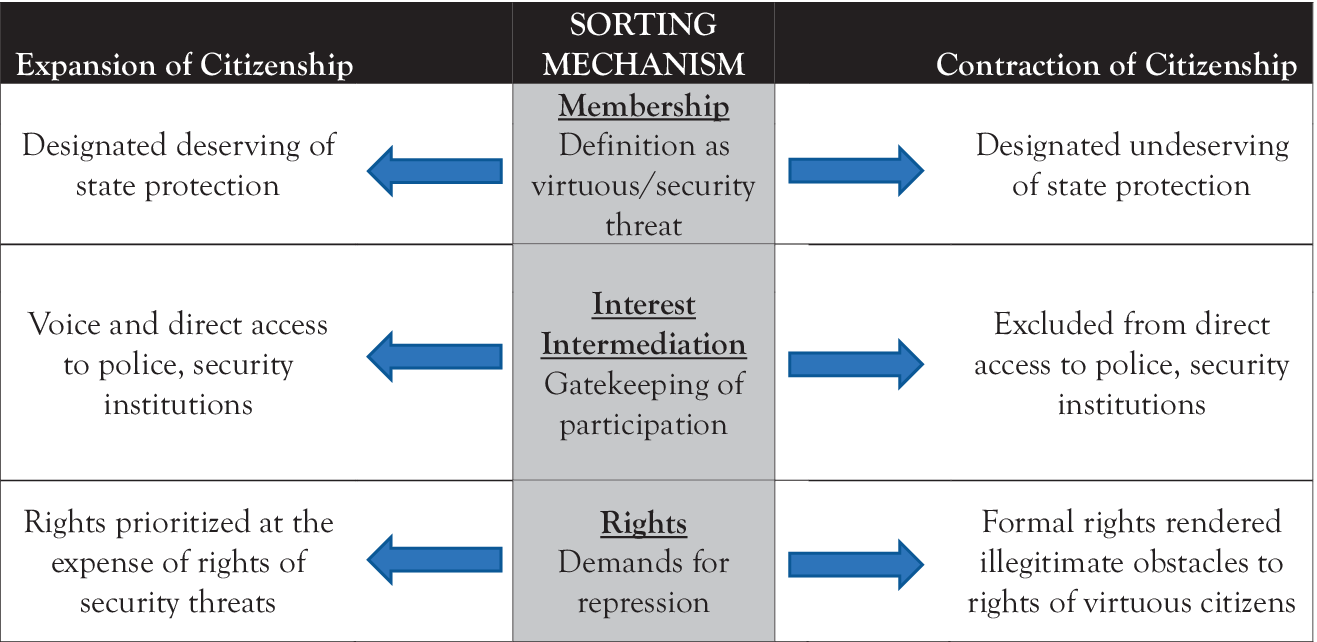

Following widespread protest in response to police violence—including the United States, Nigeria, Colombia, and Chile—scholars, advocates, and ordinary citizens are questioning the relationship between police and inequality in democracy. We add to these debates by elucidating mechanisms through which democratic participation can reproduce rather than ameliorate unequal policing. Through qualitative analysis of São Paulo’s Community Security Councils, we propose three mechanisms by which participatory security institutions—formal spaces for citizen participation in policing (González Reference González2016)—produce asymmetric citizenship: (1) by defining advantaged groups as virtuous citizens while labeling marginalized groups as security threats; (2) by acting as gatekeeper, amplifying the voice of virtuous citizens and silencing those labeled security threats; and (3) by articulating demands for police repression of “security threats” to protect the rights of “virtuous citizens.”

Our framework makes three contributions to the literature on policing, inequality and democracy, and participatory institutions. First, we elaborate mechanisms for explaining the contradictory persistence of police violence against marginalized populations in democracy, a common finding in scholarship on policing and democracy (Ahnen Reference Ahnen2007; Bonner et al. Reference Bonner, Seri, Kubal and Kempa2018; Caldeira Reference Caldeira2002; Mitchell and Wood Reference Mitchell and Wood1999) but whose causal processes remain opaque. Recent scholarship demonstrates the detrimental effects of policing on democratic citizenship, including political participation (Laniyonu Reference Laniyonu2018; Weaver and Lerman Reference Weaver and Lerman2010) and sense of belonging (Herring Reference Herring2019; Prowse, Weaver, and Meares Reference Prowse, Weaver and Meares2019) among those who directly experience punitive contacts with police.Footnote 3 This article elucidates how democratic processes sustain this persistent outcome. Moreover, although this literature demonstrates how policing undermines citizenship for marginalized groups, it overlooks how policing can simultaneously expand citizenship rights for others. We highlight the role of participatory security institutions in expanding the citizenship rights of participants, enhancing access to the state and responsiveness from police institutions to their demands. Yet, paradoxically, this deepened democratic citizenship is achieved by contracting the rights of marginalized groups. Our findings urge caution among advocates seeking to reduce police violence, signaling that increased citizen participation may reproduce abuses against marginalized groups.

Second, we contribute to scholarship on democracy and inequality, highlighting how policing reinforces inequality under democracy. Rather than focusing on inequality in traditional representative institutions (Gilens and Page Reference Gilens and Page2014; Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2010), we shift the level of analysis to the experience of democracy on the ground by citizens. We emphasize how democracy creates forms of privilege and exclusion in a political arena where people have daily contact with the state but that the literature on inequality and democracy rarely examines: policing. Yet our framework has broader implications for democracy beyond policing. Policing is an example of a broader set of policies that entails the imposition of bodily harm against some to protect the safety of others. We show that democratic participation in such policy areas—including environmental protection—may reproduce inequalities by expanding the citizenship rights of some citizens through the contraction of the rights of others. Our paper introduces the threat of bodily harm against some for the safety of others as an overlooked example of the distribution of risk along lines of social stratification in unequal democracies, with important implications for citizenship.

Third, we add to the literature on participatory institutions, which largely overlooks policing and security. Most scholarship on participatory institutions studies policy areas that distribute public goods and benefits such as health, social assistance, and public works (Falleti and Cunial Reference Falleti and Cunial2018; Mayka Reference Mayka2019a; Wampler Reference Wampler2015). As critics note, participatory institutions in these areas may not fulfill their emancipatory potential by excluding disadvantaged sectors from receiving benefits (McNulty Reference McNulty2013; Parthasarathy, Rao, and Palaniswamy Reference Parthasarathy, Rao and Palaniswamy2019). In contrast, we argue that participatory institutions in policing do not merely distribute benefits inequitably; they create a new form of structural inequality by threatening bodily harm against marginalized groups to protect privileged groups. We show how this asymmetric citizenship emerges from informal processes rather than formal institutional design.

DEMOCRACY AND POLICING: CHALLENGES TO EQUAL CITIZENSHIP

Political science scholarship has long demonstrated that democratic institutions can yield systematically unequal outcomes that are biased toward more powerful groups (Bachrach and Baratz Reference Bachrach and Baratz1962; Schattschneider Reference Schattschneider1960). Scholars have examined how democratic processes exacerbate societal inequalities by facilitating greater participation and access by advantaged citizens (Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995) and granting greater policy influence to the powerful (Gilens and Page Reference Gilens and Page2014). Such disparities in engagement, access, and influence over political processes are highly consequential, resulting in increased economic inequality in the United States (Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2010).

Although these scholars reveal how democracy reproduces inequality, they seldom consider the role of police in these processes. However, a parallel literature demonstrates how policing can exacerbate inequalities. Recent studies show that Black Americans are three times more likely to be killed by police than are their white counterparts (Streeter Reference Streeter2019). Scholars of Latin America similarly highlight race and class as important determinants of police violence (Brinks Reference Brinks2008), particularly in Brazil (Alves Reference Alves2014; Mitchell and Wood Reference Mitchell and Wood1999). Scholars show that aggressive and discriminatory policing strategies have detrimental effects on the educational outcomes (Legewie and Fagan Reference Legewie and Fagan2019) and mental health (Geller et al. Reference Geller, Fagan, Tyler and Link2014) of Black youth in the US and deprive people experiencing homelessness of “medical and economic means of survival” (Herring Reference Herring2019, 774). Others examine how police reinforce patterns of social inequality through the selective distribution of protection and repression (González Reference González2017; Prowse, Weaver, and Meares Reference Prowse, Weaver and Meares2019).

Police’s contribution to “the substantial gap between the formal principles and the actual practices of democracy” (Mitchell and Wood Reference Mitchell and Wood1999, 1015) make policing essential for understanding how enduring inequalities translate into unequal experiences of citizenship. As Marshall (Reference Marshall1950) explained, formal citizenship rights do not guarantee substantive rights in practice. Citizenship is not a fixed state but “a fluid status that is produced through everyday practices and struggles” (Glenn Reference Glenn2011, 1). Social and political inequalities shape who has the “right to have rights” (Arendt Reference Arendt1976, 298): who belongs to the polity and who does not, and which rights matter and which are only on paper (da Matta Reference da Matta, Wirth, Nunes and Bogenschild1987). As “the most conspicuous presence of the state’s power for both good and bad” (Bittner Reference Bittner1990, 19), police play an outsized role in shaping access to rights and the state along markers of inequality, reinforcing what González (Reference González2017, 495) calls “stratified citizenship.”

Contrary to the promise of democracy to constrain police’s coercive authority and protect human rights (Bayley Reference Bayley2006, 19), recent scholarship reveals how democratic processes and institutions impede efforts to constrain police abuses (Davis Reference Davis2006; González Reference González2020). Politicians often have strong incentives to frame punitive and repressive “tough-on-crime” policies as the solution to insecurity (Krause Reference Krause2014, 111). Many portray human rights as an illegitimate obstacle (Bonner Reference Bonner2019; Smith Reference Smith2019) or use rights language to justify police repression (Mayka Reference Mayka2021). Police violence may have considerable public support (Caldeira Reference Caldeira2002), reinforced through democratic elections (Ahnen Reference Ahnen2007). When societal preferences over policing diverge along cleavages like race and class, representative institutions prioritize demands for repression from more powerful societal sectors (González Reference González2020) and selectively sideline the demands of marginalized groups, yielding repressive criminal-justice policies (Eckhouse Reference Eckhouse2019; Miller Reference Miller2016).

Given these shortcomings of representative institutions, new institutional venues for citizen participation and oversight offer a promising route for reducing unequal policing. Proponents laud participatory institutions—state-sponsored venues that engage citizens directly in policy-making processes—for overcoming the deficiencies of traditional representative institutions (Avritzer Reference Avritzer2009; Fung and Wright Reference Fung and Wright2003). Scholars argue that participatory institutions create new openings for civic engagement among poor and marginalized groups who typically lack access and resources needed for effective interest representation (Coelho Reference Coelho2006; Wampler Reference Wampler2015). In practice, some participatory institutions struggle to fulfill their egalitarian promises by replicating clientelist dynamics in contexts of weak civil society (Baiocchi, Heller, and Silva Reference Baiocchi, Heller and Silva2011; Montambeault Reference Montambeault2015), lacking sufficient authority to deliver benefits (Mayka Reference Mayka2019b; Wampler Reference Wampler2007) or disproportionately including male or middle-class participants (McNulty Reference McNulty2013; Parthasarathy, Rao, and Palaniswamy Reference Parthasarathy, Rao and Palaniswamy2019). Despite these challenges, a growing literature reveals that participatory institutions can indeed produce policy changes that reduce inequality in health care and housing (Donaghy Reference Donaghy2011; Touchton, Sugiyama, and Wampler Reference Touchton, Sugiyama and Wampler2017) and promote equitable distribution of security resources (Hong and Cho Reference Hong and Shine Cho2018).

Could participatory institutions reduce the inequalities in citizenship reproduced by policing? With growing global protests over policing practices, some entities—including Chicago’s Police Accountability Task Force (2016, 17) and the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing (2015, 41)—recommend expanding institutions for community participation in policing. But scholars show participatory security institutions yield mixed results. Some caution that these institutions can promote punitive and repressive demands, as with São Paulo’s CONSEGs (Alves Reference Alves2018; Cruz Reference Ana Paula Galdeano2009) and San Francisco’s community-police meetings (Herring Reference Herring2019, 781–2), or constitute “perfunctory policing” spaces where citizen complaints are ignored, as in Chicago’s Police Board meetings (Cheng Reference Cheng2020). Yet, others highlight their ability to increase responsiveness to the community on security-related concerns, as with Chicago’s beat meetings (Fung Reference Fung2004; Skogan and Hartnett Reference Skogan and Hartnett1999) and Bogotá’s Local Security Fronts (Moncada Reference Moncada2009). This paper reconciles these contradictory findings, specifying mechanisms by which participatory security institutions simultaneously increase responsiveness for some groups while promoting repression against others.

ARGUMENT: POLICING, PARTICIPATORY INSTITUTIONS AND THE PRODUCTION OF ASYMMETRIC CITIZENSHIP

As Lowi (Reference Lowi1964) and others have argued, the structures of different policy areas yield distinct logics of demand making and distributions of power among societal groups. We consider a policy area, policing, in which one group gains protection by demanding state coercion against another group—as evidenced by the high proportion of police killings resulting from “citizen-initiated service calls” (Streeter Reference Streeter2019, 1130). This substantial threat of bodily harm against one group to protect the safety of another—rather than the gain or loss of material benefits—distinguishes policing from other kinds of policies. Distributive policies apportion scarce resources, and those who do not receive resources lose out. Redistributive policies reallocate resources from one losing group to benefit another group. However, with policing the losing groups are not simply deprived of a scarce resource; along with receiving less protection, they are subjected to an additional harm—repression.

Under high inequality, policing protects favored groups by threatening bodily harm against marginalized groups including low-income, racialized, and otherwise excluded populations. Meanwhile, marginalized groups not only face deficient protection; they also endure disproportionate police repression. Such “distorted responsiveness” (Prowse, Weaver, and Meares Reference Prowse, Weaver and Meares2019, 1423) characterizes police treatment of various marginalized groups including racialized and low-income communities throughout the US (Soss and Weaver Reference Soss and Weaver2017) and Brazil (Alves Reference Alves2018; Mitchell and Wood Reference Mitchell and Wood1999), people experiencing homelessness (Herring Reference Herring2019; Mayka Reference Mayka2021; Stuart Reference Stuart2016), and undocumented immigrants (Armenta Reference Armenta2017). Not only do “some persons feel the sting of police scrutiny merely because of their station in life” (Bittner Reference Bittner1990, 100)—the disproportionate repression experienced by these groups emerges from privileged groups’ demands for protection.

We argue that, in highly unequal settings, increasing citizen engagement in policing produces asymmetric citizenship by amplifying one group’s demands for protection through the imposition or threat of bodily harm against another group. Participatory security institutions deepen privileged participants’ experience of citizenship by validating their right to protection and creating avenues for them to shape the state’s exercise of coercion. Yet expanding citizenship for these participants occurs by demanding the repression of marginalized groups, contracting those groups’ citizenship rights. This outcome contradicts participatory democracy’s goal of ameliorating inequalities.

We elaborate three mechanisms by which participatory security institutions produce asymmetric citizenship, which map onto three dimensions of citizenship conceptualized by Yashar (Reference Yashar, Sznajder, Roniger and Forment2013, 432–3). First, defining groups as virtuous citizens or security threats shapes membership, or who belongs as a citizen. Community participants and state actors engaged in participatory security institutions use discourses that designate privileged citizens as belonging and deserving protection while defining disadvantaged “others” as security threats who do not belong. Second, gatekeeping limits interest intermediation, which entails the terms of participation and accountability connecting citizens to the state. Participatory security institutions generate gatekeeping processes that grant “virtuous citizens” direct access to state security officials while excluding “security threats” from these venues. Third, demands for repression shape the rights extended to members. Participatory security institutions present repression against “security threats” as essential to protecting the rights of “virtuous citizens.”

These three mechanisms are jointly necessary, sequential, and mutually reinforcing in the production of asymmetric citizenship (Figure 1). Sorting citizens into virtuous citizens and security threats facilitates their inclusion and exclusion from participation, respectively, which in turn enables demands for repression.

Figure 1. Asymmetric Citizenship: Sorting Mechanisms of Participatory Security Institutions

Definition as Virtuous Citizens or Security Threats

Participatory security institutions sort citizens through the joint social construction of opposing target populations (Schneider and Ingram Reference Schneider and Ingram1993, 335), defining privileged groups as virtuous citizens deserving of protection and marginalized groups as security threats. Virtuous citizens are those who uphold dominant social norms: individuals who are seen by state and societal actors as law-abiding, upstanding contributors to society—someone who is “a good worker, family provider, and honest person” (Holston Reference Holston2008, 256). In contrast, individuals defined as security threats are seen as defying social norms and morally deviant, representing “the threat not only of crime but also of social decay” (Caldeira Reference Caldeira2000, 32). The process of sorting citizens into virtuous or security threats is relational, with groups struggling to gain recognition as virtuous citizens relative to their more marginalized counterparts. Thus, even in poor communities, the comparatively privileged will seek to define themselves as virtuous (Holston Reference Holston2008, 253–60).

The definition of some groups as virtuous and others as security threats occurs in many spaces, including the media (e.g., Gilliam and Iyengar Reference Gilliam and Iyengar2000), public policy implementation (e.g., Soss Reference Soss1999), and electoral campaigns (e.g., Bonner Reference Bonner2019). Participatory security institutions do not originate these social categorizations but rather reproduce them through discursive practices emerging from iterative grassroots participation.

This mechanism shapes a primary dimension of citizenship—membership—defining who belongs and thus on whose behalf, and against whom, police are authorized to use force. “Ordinary” residents and public officials involved in participatory security institutions routinely frame marginalized groups—including poor and racialized populations and people experiencing homelessness, among others—as threatening the security of upstanding community members, not as fellow citizens in need of support.

As the policy-feedback literature demonstrates, such messages shape citizens’ relationship to the state and understanding of their rights (Soss Reference Soss1999; Soss and Weaver Reference Soss and Weaver2017; Weaver and Lerman Reference Weaver and Lerman2010). Groups sorted into the category of virtuous citizens deserving of protection experience an expansion of citizenship rights. Protection from crime and violence is an essential component of democratic citizenship (Brysk Reference Brysk, Sznajder, Roniger and Forment2012), shaping whether citizens feel sufficiently safe to participate in essential political, economic, and community activities (González Reference González2017). Being designated as deserving protection endows these groups with a broader sense of belonging and inclusion in the polity. Conversely, discourses defining certain groups as undeserving of protection and as security threats promote the contraction of their democratic citizenship.

Gatekeeping of Participation

The second sorting mechanism is gatekeeping to determine inclusion or exclusion from the participatory institution, which is a site of engagement with the state. As Schneider and Ingram argue, the social construction of target populations sends differing messages about participation: groups deemed deserving receive “messages that encourage them to combat policies detrimental to them through various avenues of political participation,” whereas those deemed undeserving receive messages “that encourage withdrawal or passivity” (Reference Schneider and Ingram1993, 334). Participatory security institutions employ informal practices—such as narratives about social groups and the roots of crime (Cruz Reference Ana Paula Galdeano2009) and silences in response to certain groups’ demands (Cheng Reference Cheng2020)—that encourage participation by those deemed worthy of protection while indicating to “security threats” that their perspectives are unwelcome. The iterative nature of participatory security institutions reinforces these messages over time, enabling these informal practices to function as gatekeeping.

Through gatekeeping, participatory security institutions shape the interest-intermediation component of citizenship, delineating who is entitled to express their demands to state actors responsible for security. Participatory security institutions represent, at least in theory, an opportunity for accountability over an otherwise-inaccessible state institution that routinely violates human rights. For “virtuous citizens” whose participation is encouraged, participatory security expands their rights, providing important channels for interest intermediation. Meanwhile, the marginalized groups most likely to face police abuses are excluded from these spaces, losing a channel for voice and accountability over policing.

Demands for Repression

The final sorting mechanism entails the articulation of demands for repression against groups deemed security threats. We define repression as the actual or threatened use of coercion against individuals to deter activities seen as challenging social order through constraints on rights such as freedom to circulate and due process (Davenport Reference Davenport2007, 2; Goldstein Reference Goldstein1978, xxvii). Participatory security institutions often generate demands to deploy repression against populations seen as violating social order. Participants may ask police to arrest individuals defined as security threats, even if they have not committed a crime (Herring Reference Herring2019, 781). The exclusion of “security threats” from engagement in the participatory institution further reinforces demands for police repression against these populations, as they lack institutional access to challenge the police.

Articulating demands for repression is central in creating asymmetric citizenship rather than simply unequal citizenship. Rather than just one group participating more or obtaining more benefits than another group, asymmetric citizenship entails claiming one’s right to protection by threatening the bodily integrity of others. The rights of marginalized groups to be free from illegal detentions, coercion, and extrajudicial violence are rendered illegitimate obstacles that imperil the sacrosanct rights of virtuous citizens. Under asymmetric citizenship, expanding membership, interest intermediation, and rights for virtuous citizens requires contracting membership, interest intermediation, and rights for those deemed security threats.

Although participatory security institutions do not create social stratification patterns, our framework elucidates mechanisms by which these categories are reproduced, showing how democratic participation in policing can exacerbate societal inequalities. Rather than emerging solely from police discretion, we show that repressive police actions are often generated through demand making by ordinary citizens. The fact that such “complaint-oriented policing” (Herring Reference Herring2019, 771) arises from a democratic institution intended to expand citizen voice in policing underscores the effectiveness of the first two mechanisms—defining groups as security threats and gatekeeping of participation—in determining whose rights are prioritized and against whom coercion is used.

Scope Conditions

Because our framework centers on how inequality shapes demand making about policing, we expect asymmetric citizenship to emerge in highly unequal democracies whether in the Global North or South. Asymmetric citizenship can occur under governments across the ideological spectrum, as demands for repression emerge from grassroots participation rather than from elites promoting punitive approaches for electoral gain.

Asymmetric citizenship can also emerge in other kinds of institutions, with important limitations. Institutions that generate grassroots participation and are directly connected to the state—such as juries or town hall meetings—may engender asymmetric citizenship in unequal democracies. In contrast, elite-driven spaces, such as media organizations and electoral campaigns, that demand repression to protect favored groups do not produce asymmetric citizenship because they lack two conditions implicit in our framework. First, they are missing the iterative grassroots citizen engagement required to produce informal gatekeeping processes. Second, they lack the direct linkage to state actors or institutions necessary to affect citizenship rights. Likewise, civil-society organizations that call for police repression of marginalized groups do not alone produce asymmetric citizenship because they operate separately from the state.

Asymmetric citizenship may also emerge in policy areas beyond policing. Policing is an instance of a broader set of policies with the potential to protect the safety of one group by imposing or threatening bodily harm against another group. For policy areas such as environmental protection—including decisions about storing toxic waste or siting landfills—the health of those living near environmental contaminants is imperiled to protect others’ safety. Underlying social inequalities incentivize powerful groups to frame environmental dangers imposed on marginalized groups as necessary for their own right to health and safety, promoting asymmetric citizenship. For instance, decisions to site nuclear waste on indigenous land in the US were characterized by “discourse explicitly defin[ing] American Indians as subversive, inherently dangerous, oppositional, and always already guilty” and processes that “exclud[ed] American Indian voices from deliberation” (Endres Reference Endres2009, 46–7)—a pattern also found in decisions to site nuclear waste on tribal lands in Taiwan (Fan Reference Fan2006, 434). As with policing, these environmental decisions exclude a marginalized group from membership, interest intermediation, and the right to bodily safety while expanding the citizenship rights of groups deemed worthy of protection.

CASE SELECTION AND METHODOLOGY

São Paulo’s CONSEGs: A Most-Likely Case for Reducing Unequal Policing

Brazil, and São Paulo in particular, offer an ideal context in which to study whether democratic participation in policing reduces or exacerbates inequalities. Brazil’s constitution provides strong rights protections, and the country has robust participatory institutions across multiple policy areas that have reduced political and social inequality (Mayka Reference Mayka2019a, 92–3; Wampler Reference Wampler2015). Nevertheless, policing in Brazil yields stark racial and class disparities, particularly in São Paulo (Alves Reference Alves2018; Brinks Reference Brinks2008, 149–51; Caldeira Reference Caldeira2002). Per the 2010 Census, Black residents comprised approximately 37% of the city’s population, yet they were 65% of police killing victims; 76% of Black Paulistanos had completed only primary education (Mariano Reference Mariano2018, 26–7). Police killings in the state exceeded 800 victims annually in recent years (Fórum Brasileiro de Segurança Pública 2020, 84)—higher than the official count of victims killed under the 21-year military dictatorship (Caldeira Reference Caldeira2002) and on par with the approximately 1,000 police killings annually in the entire US,Footnote 4 whose population is six times greater. Racialized police violence also manifests as retaliatory chacinas (massacres) in São Paulo’s peripheries and militarized drug operations in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas, whose victims are largely young Black men.

Although participatory security institutions exist in most Brazilian states—with varied structures, composition, and durability—São Paulo’s CONSEGs stand out as a “most-likely case” (Gerring Reference Gerring2007, 120–1) for ameliorating inequalities in policing given their democratizing origins, low barriers to participation, and high levels of institutionalization.

The CONSEGs were created in 1985,Footnote 5 with the explicit intent of democratizing policing, as then-Secretary of Security of São Paulo State, Michel Temer, explained:

We were still in 1985 or 1984, under an authoritarian regime at the [federal] level … the idea when Governor Montoro sent me to [the secretariat of] security was to create security for a democratic state … that security wasn’t just repression, that it was also the possibility of the participation of the people in security issues.Footnote 6

The CONSEGs’ institutional design presents low barriers to participation. CONSEGs’ monthly meetings are open forums for neighborhood residents to bring demands, complaints, and questions for local police and municipal officials. CONSEGs meet in community spaces, making participation easy and convenient. Unlike other participatory institutions in São Paulo, participants need not belong to officially registered associations, reducing the concern that they only engage already-mobilized individuals (Mayka and Rich Reference Mayka, Rich, Kapiszewski, Levitsky and Yashar2021, 174). CONSEG meetings cannot take place in police stations, increasing access for citizens wary of entering a police building.Footnote 7 These low barriers to citizen participation should make the CONSEGs fruitful venues for resource-poor marginalized groups to voice concerns and demand accountability from the police.

Unlike other participatory security institutions in Latin America (González Reference González2016), the CONSEGs have endured for decades and are institutionalized: they are routinized—following regularized structure, practices, and responsibilities—and have infusion with value, meaning stakeholders view them as legitimate and important venues for citizen engagement with the state (Mayka Reference Mayka2019a, 41–6). These conditions make CONSEGs a potentially powerful site for citizens to seek remedies to unequal policing.

Our original dataset of CONSEGs in the city of São PauloFootnote 8 demonstrates their routinization. Most CONSEGs are active and meet regularly: in 2011, 85.1% of CONSEGs met at least six times; 63.2% met at least 10 times. Local commanders from the two police forces, the Military Police and the Civil Police,Footnote 9 and municipal officials comply with their mandate to attend CONSEG meetings. A Military Police official attended 92.7% of CONSEG meetings in 2011, with the local commander present at 73.9% of meetings. Likewise, a Civil Police official attended 69.2% of meetings, and local government officials were at 78.6% of meetings. The careful record keeping behind this dataset further demonstrates routinization: 93.6% of CONSEGs in the city of São Paulo kept meeting minutes on file at the CONSEG Coordinator’s Office.Footnote 10

The CONSEGs also score high on infusion with value. CONSEG meetings are well attended, signaling that community members consider participation worthwhile. CONSEG meetings had an average of 46.8 participants in 2011, and 86.4% of meetings had 25 or more attendees.Footnote 11 In interviews, both police commanders and community members described the CONSEGs as influential and respected venues. One Military Police Captain emphasized the CONSEGs’ appeal for politicians and police:

[CONSEGs] reached a level of maturity that has allowed them to have access to levels of government that the police don’t have. So, the CONSEG leaders built relationships with politicians representing their region and that’s how we got to having larger events. So, when you fill the auditorium of the Governor’s Palace with community leaders to award successful projects, the administration recognizes that this is important and that it really brings concrete benefits. And moreover, the police then adopts the discourse of working closely with community, the police references the CONSEG more, becomes more interested in the CONSEGs’ actions.Footnote 12

Police and politicians alike invest time and attention in the CONSEGs to gain community access and support. Direct access to police and other officials, in turn, makes the CONSEG a valuable site for citizen participation. The president of a low-income, majority-Black CONSEG explained, “Having direct access to those authorities is very important, because you maximize in various ways, bureaucratic issues fall by the wayside. So, having that direct contact has been fundamental.”Footnote 13 Even the CONSEGs’ critics describe them as consequential, as exemplified by a representative from a homelessness rights organization: “They have a lot of influence, yes. I’d even say this, ‘what is the CONSEG? The CONSEGs are the snitches of the city.’”Footnote 14

This institutionalization makes the CONSEGs a most-likely case for a participatory institution that could reduce inequities in policing. Many other participatory institutions only exist on paper, are implemented inconsistently, or lack authority to translate citizen participation into policy change (Mayka Reference Mayka2019a; McNulty Reference McNulty2019). In comparison, CONSEGs stand out as an effective site for citizen engagement in policing. As this paper demonstrates, however, the CONSEGs’ institutionalization also empowers them to amplify demands for police repression of marginalized groups, indicating the limits of institutional design in reducing inequities in policing.

Data and Methods

This paper draws on fieldwork conducted during 2010–2012 and 2017–2019 in São Paulo. Fieldwork during 2010–2012 included participant observation of 34 monthly meetings of 12 CONSEGs throughout the city and ethnographic observation in the CONSEG Coordinator’s office. We selected CONSEGs for observation across the north, south, eastern, western, and central zones of the city of São Paulo to capture variation in racial and class composition (see Appendix A). The city center and adjacent districts are higher-income regions with lower proportions of Black residents than São Paulo overall, whereas the northern, southern, and eastern peripheries have lower incomes and higher proportions of Black residents (Secretaria Municipal de Promoção da Igualdade Racial 2015, 5–6). Selecting CONSEGs that reflect this demographic variation allows us to assess whether the mechanisms that produce asymmetric citizenship emerge throughout the city. Because asymmetric citizenship is a function of inequality, not absolute poverty, we expect it to occur in wealthy, predominantly white neighborhoods and low-income and majority-Black neighborhoods alike. Even in low-income peripheries, the comparatively advantaged assert their greater deservingness over marginalized groups within their community. Across both fieldwork periods, we conducted 72 interviews with CONSEG community leaders, police officials, and representatives of marginalized groups.Footnote 15 To generalize findings from participant observation and interviews, we built an original dataset of 793 meeting minutes from 2011 for 87 CONSEGs in the city of São Paulo (González and Mayka Reference González and Mayka2022). We coded meeting minutes for measures of institutionalization and statements by participants or officials referring to marginalized groups including people experiencing homelessness, low-income youth, drug users, sex workers, street vendors, LGBTQ+ individuals, and waste pickers. Appendix A provides additional information on our data-collection strategy.

PRODUCING ASYMMETRIC CITIZENSHIP WITHIN SÃO PAULO’S COMMUNITY SECURITY COUNCILS

During a CONSEG meeting in a downtown district, a white-haired man in his 50s, the leader of a homelessness rights organization, addressed about two dozen residents along with local police commanders and municipal officials gathered in the large auditorium of a business association. He referenced repeated complaints at CONSEG meetings about people relieving themselves on public streets and explained the difficulty of finding bathrooms as a person experiencing homelessness. He invited attendees to the 4th Gathering for Culture and Citizenship for people experiencing homelessness at the historic Sé Square: “We’ll offer haircuts, documentation [IDs], photos, birth certificates; we’re going to be giving citizenship to people experiencing homelessness (nós vamos estar dando cidadania à população de rua).” Minutes before he spoke, another man in his 70s addressed the crowd, providing a starkly different vision of the kind of citizenship people experiencing homelessness deserve. He spoke of São Paulo’s famed Arches of São Francisco, complaining about “homeless people under the arches”: “There are certain places in the city that are sacred (solenes), as sacred as when we sing the national anthem. In addition to that sacredness, which increases patriotism, love for our country and our city, there is also the concern from an economic point of view because they’re places that tourists go to see… . They could be taken somewhere and prohibited from being exactly there where tourists go.”Footnote 16 Although both remarks were met with perfunctory “thank yous” from officials—a common occurrence in participatory security institutions (Cheng Reference Cheng2020)—a subsequent interview with the homelessness rights advocate indicated the latter man’s comment reflected a broader pattern: “The frequent complaints in CONSEGs [are] … ‘we’re not against homeless people, but he’s at my doorstep. I want to go out but I can’t … he’s making me uncomfortable. I’m going to have to call the city, call the police, to remove him from the street.’”Footnote 17 This activist hoped to use the CONSEGs to advocate for the rights of people experiencing homelessness, whereas another citizen argued instead that their removal would improve civic (and economic) life. As with other advocates for marginalized groups we interviewed, the homelessness rights advocate eventually abandoned these attempts and stopped attending CONSEG meetings.

CONSEGs are an important space for ordinary citizens to engage with local police commanders and other officials charged with guaranteeing their security—yet as the above account demonstrates, CONSEGs do not expand the experience of citizenship equally for all. Instead, CONSEGs produce asymmetric citizenship through three mechanisms: by generating discourses that sort citizens into “virtuous citizens” and “security threats,” by acting as gatekeepers to limit who engages in participatory spaces, and by articulating demands for repression against those defined as security threats.

Mechanism 1: Differentiating Virtuous Citizens versus Security Threats

CONSEGs reinforce the boundaries of citizenship, reproducing preexisting group categories that characterize social inequalities in Brazil. In both wealthy and low-income districts, participants assert that they are “virtuous citizens” (cidadãos de bem) who deserve police protection and are entitled to make demands while framing marginalized groups as inherently violent, criminal, or disorderly: security threats that endanger virtuous citizens.

Who is defined as belonging? Participants assert their status as virtuous citizens deserving protection because they are law-abiding, tax-paying contributors to society—a broader phenomenon among residents of both wealthy and poor communities in São Paulo (Caldeira Reference Caldeira2000; Holston Reference Holston2008). Across observations of multiple CONSEG meetings, participants invoked their status as deserving citizens in demanding the removal of security threats, justifying their demands by claiming “I pay my taxes.”Footnote 18 In a low-income district, one participant complained that having street vendors occupying the sidewalk was unacceptable because “we pay our taxes.”Footnote 19 A CONSEG participant in an affluent neighborhood railed against gay residents, telling the police commander, “I am a citizen, I pay my [taxes]. My son doesn’t need to see two men kissing at my front door.”Footnote 20

The marginalized groups analyzed in this study—including low-income youth, people experiencing homelessness, drug users, and sex workers—are framed during CONSEG meetings as security threats who imperil the rights of virtuous citizens. Referencing squatters in an abandoned building, one CONSEG participant explained that these groups are “people who do nothing for society.”Footnote 21

CONSEG participants frame members of marginalized groups as dangerous—often without evidence—such that their very presence is inherently menacing. In one CONSEG meeting in São Paulo’s low-income periphery, a woman expressed fear of begging children and asked for greater police protection. Another man added that loitering gangs from the local school made residents afraid to walk outside.Footnote 22 At a downtown CONSEG, a woman complained that a child was throwing rocks and harassing people, demanding his removal because he caused discomfort to elderly residents. The Military Police Captain countered that, though the child was causing a minor disturbance, he did not break any laws.Footnote 23 These community participants framed low-income youths’ presence as threatening to virtuous citizens who simply wanted to live and work in peace in their neighborhood.

CONSEG participants also depict marginalized groups as tied to criminals, equating their presence with delinquency. During one meeting in São Paulo’s northern periphery, a local merchant complained of children panhandling, characterizing it as a “school for criminality” and accusing them of collaborating with thieves.Footnote 24 At a downtown CONSEG meeting, an older white man griped that street vendors sold information about the neighborhood to criminals, claiming that robberies and muggings increased when these vendors came around. He argued that their presence brought an “air of decay” to the neighborhood, inviting other “lowlifes” (marginais) to move in.Footnote 25

Other times, participants and officials take as a given that the presence of a particular marginalized group is bad for the neighborhood. During discussions about homelessness, participants often simply noted the locations frequented by people experiencing homelessness and demanded their removal.Footnote 26 During a downtown CONSEG’s discussion of drug use, the Military Police captain noted that, “From the number of drugs we are finding … there, the problem is the user. For now, we have not identified it as a trafficking problem.”Footnote 27 The presence of drug users was itself threatening, separate from the violence and criminal activity that accompanies drug trafficking. In another well-to-do region, the local police commander told CONSEG participants that “our neighborhood will improve” once police forcibly removed some 200 people squatting on private land.Footnote 28

Our analysis of CONSEG meeting minutes confirms insights from participant observations and interviews. In each of the 87 CONSEGs in our dataset, at least one marginalized group was framed as a security threat: criminal, violent, and/or disorderly. CONSEG participants frequently describe marginalized groups—especially low-income youth, drug users, and people experiencing homelessness—as security threats (Figure 2). These patterns hold throughout the city in both wealthy neighborhoods and the poorer periphery (see Appendix A).

Figure 2. CONSEGs Framing Marginalized Groups as Security Threats

Source: CONSEG meeting minutes dataset.

Mechanism 2: Gatekeeping of Participation

CONSEGs link citizens to the state in consequential ways, yet this institution is not open to all community members. On the one hand, CONSEGs create channels that amplify the voices of “virtuous citizens,” providing direct linkages to police commanders that enable greater responsiveness. On the other hand, CONSEGs exclude marginalized groups through informal gatekeeping mechanisms, closing off opportunities to seek redress for police abuses.

CONSEGs expand citizenship by linking participants to police and local officials—whose attendance is mandated by law—creating a sustained institutional space for citizen voice and police responsiveness. In an interview, one CONSEG president described his surprise when he first attended CONSEG meetings with police commanders: “I never imagined myself as a community member having that type of access.”Footnote 29 Participatory institutions in other policy areas in São Paulo, such as health or housing, are typically attended by mid-level bureaucrats, not top leadership. The State Coordinator of the CONSEGs explained,

When do you get to speak directly with someone who can resolve a health problem? When can you speak directly to someone who can resolve a problem of public sanitation? It’s not like that with security… . [In the CONSEG] the Military and Civil Police speak directly to you about their role, what they’re doing… . That’s the most important role of the CONSEG for the society, to demonstrate to [citizens] that they are speaking directly to those in charge.Footnote 30

The CONSEG’s access to “those in charge” is particularly striking given the police’s centrality in repression both during Brazil’s military dictatorship (Barcellos Reference Barcellos1992) and under democratic rule (Caldeira Reference Caldeira2002; González Reference González2020, 93–105). Access to and responsiveness from police can be especially meaningful for residents of São Paulo’s stigmatized periphery. One low-income CONSEG meeting participant said his treatment by police improved upon telling them that he participated in the CONSEG, reminding them “I know your Captain.”Footnote 31 Another CONSEG participant, a resident of a large favela, thanked the police for responding to an incident at the hospital where he works. He expressed appreciation for having a space where he can speak up and be treated as an equal, something he said rarely happens for residents of a poor community (comunidade carente).Footnote 32 Even in the low-income communities most likely to suffer police abuses, some residents depend on police protection (Bell Reference Bell2016).

However, increased access to the state is limited to “virtuous citizens.” Participant observation of 12 CONSEGs revealed that participants are disproportionately likely to be business owners, members of neighborhood associations, and comparatively well-off community members, even within poorer areas of the city. Human-rights officials from the state’s Public Defender Office remarked that CONSEGs narrowly represent “the community”: “The community is only understood as business owners, residents’ associations,”Footnote 33 and that “those security councils, they’re very reactionary. Usually, they are business owners with ties to police.”Footnote 34 Even in low-income communities, these groups are unlikely to experience police repression and seldom use CONSEGs to demand accountability for police abuses.

An account from the president of a mixed-income CONSEG reveals the access and responsiveness that CONSEGs provide, and for whom. After a contentious relationship with the district’s police commander, the CONSEG president met with the city’s top police commander, bringing along a “committee” of CONSEG members: “the Rotary Club leader, the butcher shop owner, the toy store owner, the hostel owner, the nursing home representative.”Footnote 35 This pressure was effective: the following month, the well-regarded commander of a downtown CONSEG notified dismayed participants of his transfer to that district.Footnote 36

During CONSEG meetings, “virtuous citizens” are repeatedly invited to voice their concerns and hold officials accountable. In one CONSEG meeting in an affluent district, a newly appointed police commander encouraged participants to contact him, even outside of CONSEG meetings.Footnote 37 One participant of this CONSEG reinforced the importance of participation: “when the people mobilize, it makes things work.” Public officials and CONSEG leaders consistently communicate to conseguianos—as state and municipal officials often call CONSEG participants—that CONSEG participation is an important civic action,Footnote 38 an “exercise of citizenship.”Footnote 39

Although marginalized groups are more likely to have negative interactions with police, participant observation revealed that poorer individuals, Black people, and other marginalized groups rarely attended CONSEG meetings, a pattern also found by other researchers (Alves Reference Alves2018; Cruz Reference Ana Paula Galdeano2009). During interviews with advocacy organizations for marginalized groups, no respondent described the CONSEG as a welcoming or productive space, although most had previously attempted to advocate for the rights of marginalized groups within CONSEGs. A representative of a sex workers’ organization explained: “I hate going to CONSEG meetings, I hate it! It’s horrible every time I go to those things because it’s those people with military training alongside a conservative population, you know how it ends up, right? When I speak about our work alongside women in prostitution, the only thing missing is for them to stone me.”Footnote 40

The CONSEG’s institutional design, with low formal barriers to participation, could facilitate engagement by marginalized groups. In practice, however, discursive practices within CONSEGs convey to members of marginalized groups that they are unwelcome, irrespective of formal rules. A Black woman who works for CEDECA (Centro de Defesa dos Direitos da Criança e do Adolescente), an organization that supports poor, largely Black youth, recalled attending a CONSEG meeting in the poor eastern periphery: “It’s police, along with business owners who ask for the police’s help … there’s no way to have a dialogue… . They would address me [imitates them speaking with contempt] ‘look, it’s the representative from the CE-DE-CA.’ No one from the CEDECA has gone back there.”Footnote 41 At times, enmity toward advocates or members of marginalized groups boils over. An official with the Public Defender’s Office recounted receiving reports of CONSEG participants threatening a priest who does homelessness ministry work.Footnote 42 The homelessness rights association leader cited earlier described an explosive exchange with a police commander: “the Military Police commander almost climbed over the table to strangle me, he almost attacked me … he said, ‘I know where you live’ and I said, ‘I know where to find you, too.’”Footnote 43

Even without outright hostility, those advancing nonrepressive policing approaches are rapidly dismissed. In one low-income, majority Black CONSEG, where a recurring complaint was “pancadão”—unauthorized street parties frequented by youth from São Paulo’s low-income, largely Black peripheries (Cardoso Reference Cardoso2019, 169)—an elderly Black man advocated for an alternative to police repression:

Even I’ve said, ‘they’re all lazy bums (vagabundos)’ but is that really the case? Youth want to have fun, it doesn’t matter where. If there’s no place, you go to the street. City Hall doesn’t care about [our community]. I’m appealing to the CONSEG, to [the police commander], to the community … the police will work our entire lives trying to resolve this pancadão problem. We have to build a space for shows, parties, for people to have fun… . I’m appealing to all the entities here, let’s do this together.

However, the man, was interrupted by the police commander, who urged attendees to report the locations of pancadões, and then by the CONSEG president, who hastily called on another participant.Footnote 44

These accounts reveal that marginalized groups do not miss out on interest intermediation within the CONSEGs simply because they fail to show up. Indeed, interviews with organizations advocating for marginalized groups indicate that most had attempted to participate in the CONSEGs yet faced such hostility that they gave up. One advocate for justice-involved youth noted, “we don’t even have time to work with the people who like us, imagine using that time to deal with people who don’t like us.”Footnote 45 A member of an activist collective combatting police violence in a skid-row zone known as “Cracolândia” (Crackland) described the CONSEG as only good to learn about impending threats: “[we went] from the perspective of gathering information, more to understand the terrain than trying to influence in some way or participate in the CONSEG. We never had the pretense of participating in the CONSEG.”Footnote 46 Despite activists’ efforts, the CONSEGs routinely push out the marginalized groups most likely to experience violence from both criminals and police. Our interviewees signaled that the CONSEGs failed to live up to their promise to democratize policing for marginalized communities. None of our interviewees expressed a vision for reforming the CONSEGs to capture this potential or an alternative democratic space in which to engage police.

Mechanism 3: Channeling Demands for Repression to Protect Citizenship Rights

Within CONSEGs, “virtuous citizens” and state officials develop discourses about the substance of citizenship: which rights are entailed in citizenship and which rights are illegitimate. CONSEG meeting participants often invoke their own rights while demanding police interventions that limit the rights of others. Participants emphasize their right to a peaceful, middle-class life, undisturbed by groups defined as security threats. For instance, a white woman complained about seeing waste from people experiencing homelessness in a city park while jogging, claiming, “I have the right to move about freely.”Footnote 47 Another woman expressed dismay about street vendors selling alcohol in a public park, which led to public drunkenness, arguing that “residents have the right to live peacefully.”Footnote 48

CONSEG participants use this space to reframe the civil liberties, procedural rights, and social rights of marginalized groups as unfair privileges that endanger virtuous citizens’ legitimate rights. Within CONSEGs, a common refrain is that criminals have more extensive rights than do law-abiding citizens. CONSEG participants routinely complained that “we pay our taxes … [yet] the working people, we are locked up inside our homes”Footnote 49 while “the criminal is free.”Footnote 50

CONSEG participants disparage due-process rights that protect individuals from state harm as particularly illegitimate obstacles to their safety and rights. During one downtown CONSEG meeting, a Military Police commander complained that if drug addicts have the right to roam the streets, what happens to a law-abiding citizen’s right to walk about freely?Footnote 51 In a CONSEG meeting in the southern periphery, a conservative congressman proposed undoing that right altogether, touting his bill permitting involuntary institutionalization (internação compulsória) of drug users, which was met with attendees’ approval.Footnote 52 In another meeting, participants complained that “Cracolândia is spreading, we now have more drug users,” and asked police to increase arrests. The Civil Police commander said his hands were tied because “the law is weak.” A participant responded incredulously that a new Supreme Court ruling ensured that “drug dealers can now be freed while awaiting trial.”Footnote 53 A Black human-rights lawyer working with Black youth in the city’s poor eastern zone recalled how such discourses led him to stop participating in CONSEG meetings: “The majority of participants are business owners, police people, so they have a discourse that’s very quick to clash, deconstruct human rights … the criticism is that we only support the criminals, that human rights are really criminals’ rights (direitos humanos é direito dos manos).”Footnote 54

CONSEG participants contest the validity of marginalized groups’ social rights by challenging whether the group is truly needy. During one CONSEG meeting in a middle-class neighborhood, a participant asserted that many homeless individuals actually had homes in the periphery and commuted into their neighborhood to panhandle because it was so lucrative. Meeting participants complained about those who give money or food to people experiencing homelessness, decrying a small team from the municipal health department dedicated to homeless families’ health.Footnote 55 CONSEG participants across the city asked police to remove people experiencing homelessness, leading police officials to push back that homelessness was “not only a police problem but a social problem.”Footnote 56

Other times, participants or officials suggest that social-policy approaches would simply aggravate security problems. One CONSEG president from a middle-class neighborhood explained that offering services to people experiencing homelessness ultimately causes greater disorder and crime: “Although you may be Catholic and have to help others, this is not the right way to help others. Because he eats your food, and he stays there on the block or threatening people or begging for money to drink cachaça.”Footnote 57 The leader of a group advancing the rights of homeless individuals and drug users recalled that participants in a downtown CONSEG rejected a proposal for a temporary public bathroom, saying, “We don’t want things that will keep people here; we don’t want bathrooms provided by public authorities to these people; we want police intervention to remove these people.”Footnote 58

Likewise, CONSEG participants faulted the expansive rights codified in Brazil’s child welfare system for increasing crime and disorder. The middle-class CONSEG president explained,

A child cannot be prosecuted in any way. This means that, if I catch a child committing the crime of murder and the parents come to get them, I have to release the child to them. The child cannot be taken to a police station, the most you can do is look for social inclusion [services] for the child… . We had a problem with children robbing stores in a small shopping center. We worked intensively … [and] resolved the problem of the children. How? We arrested their mothers for material abandonment.Footnote 59

This CONSEG president views the guaranteed rights of children as a source of crime that must be defanged to protect community safety. In a low-income CONSEG, a participant emphasized the need to change these laws, asking incredulously, “Why do minors have the right to steal?”Footnote 60 During another CONSEG meeting, a man complained about adolescents drinking in public—an issue that should trigger services from the child-protection system. The man scoffed at this approach, insisting that “a minor consuming alcohol is not a social problem, it’s a police problem, and the police have to act.”Footnote 61

CONSEG participants clearly communicate that the procedural, civil, and social rights of marginalized groups must be constrained to protect the rights of virtuous citizens, even if doing so necessitates bodily harm. A common theme in CONSEG meetings is the need for police repression to remove drug users, individuals experiencing homelessness, or street vendors while rejecting solutions to the root causes of underlying problems.Footnote 62 In one meeting in the city-center, a resident used dehumanizing language to criticize as insufficiently violent a police action to displace drug users: “The action in Nova Luz was wrong. It just threw water on the anthill. You have to kill the anthill or it just goes somewhere else; I think exterminating it would’ve been better.”Footnote 63 A leader of a homelessness rights association expressed frustration with the CONSEGs’ focus on displacement instead of social programs:

The business owner comes to the CONSEG and says, “Hey look, I have a lot of homeless people coming and disrupting my business.” And the Military Police is there, and is being asked to remove homeless people. But they don’t have the kind of perception of the Military Police to say, “So I’m going to remove them and take them where?” [Business owners] come and simply say, “Take that person from here—you have to go somewhere else because you can’t stay here.”Footnote 64

Likewise, a representative of an organization that works with informal street vendors described how local merchants use the CONSEGs to demand removal of vendors, instead of discussing services to help vendors gain formal status: “The business owners determine everything … they constantly provoke the police forces to take action against irregular commerce… . They never think of a more intelligent alternative to regularize, to regulate [it]. It’s a zero-sum logic.”Footnote 65

Sometimes, CONSEG participants openly promote extrajudicial violence by police against marginalized groups. Participants in a downtown CONSEG praised the police for the aforementioned violent removal of drug users from Cracolândia.Footnote 66 The advocate working with Black youth in eastern São Paulo recalled participants defending police killings: “They would say ‘that’s why so many of them disappear, he committed a robbery in such and such place.’” A similar scene occurred in a low-income, majority-Black CONSEG meeting when a woman reported that police killed her neighbor’s son “because he was stealing.” Other attendees responded “Amen” and that the officer “performed a service.”Footnote 67

Our analysis of CONSEG meeting minutes corroborates the frequency of demands for repression (Figure 3). Demands for repressive policing are particularly striking for low-income youth, drug users, and people experiencing homelessness. These patterns appear across diverse districts throughout São Paulo in affluent and low-income areas alike (see Appendix A).

Figure 3. CONSEGs Demanding Police Repression of Marginalized Groups

Source: CONSEG meeting minutes dataset.

Police commanders, in turn, reinforce citizen demands for repression. During CONSEG meetings, police discuss both future repressive operations and past actions against marginalized groups in response to citizen demands, as Figure 4 summarizes. In one low-income CONSEG, police discussed prior operations against pancadões that employed “tear gas bombs and rubber bullets” while multiple attendees thanked police for recent operations to shut down unauthorized street parties frequented by favela youth.Footnote 68 Thus, the emergence of discourses and demands for repression of marginalized groups is a relational process.

Figure 4. Police Statements Promoting Repression of Marginalized Groups

Source: CONSEG meeting minutes dataset.

In summary, demands within CONSEGs for violent removals and repression are presented as democratic—a way for citizens to advocate for their rights and to demand accountability from the state. However, this expansion of citizenship rights occurs through the contraction of rights for those defined as security threats, who are implicitly and explicitly cast out of CONSEGs and then characterized as justified targets of repression. This asymmetric citizenship is captured by the homelessness rights leader, who, as described above, attempted to access the CONSEG as a space for citizenship, only to face exclusion and threats:

I don’t think it’s wrong for someone to take advantage of a space where you have public authorities and for you to reclaim your rights… . Now, reclaiming your right while stepping on others, humiliating others, I don’t agree with that and that’s what happens in the CONSEGs.Footnote 69

Conclusion

On paper, the CONSEGs seem like a promising institutional venue for marginalized communities to hold police accountable. As the human-rights lawyer working in São Paulo’s eastern zone explained, “[The CONSEG] is a space that, if it worked, I think it could serve in the construction of something, better alternatives, [such as] how we could talk to the police about some of our cases or why the police is so violent here.”Footnote 70 However, our analysis demonstrates that democratizing policing through citizen participation may not yield more egalitarian policing for all and may instead generate new forms of inequality by producing asymmetric citizenship. These findings urge caution among reformers advocating increased community participation to counteract police violence. Expanding participation in policing can encourage and reproduce police abuses against marginalized groups, doing more to silence than to engage these voices.

Our analysis suggests why combatting police abuses can often prove challenging, even for democracies—or perhaps especially in democracies. Our work reveals an element of democratic responsiveness and legitimacy to police repression of marginalized groups ignored by much of the scholarly literature, media, and popular discourse. Rather than resulting solely from rogue or poorly trained officers, police repression can emerge in response to citizens’ demands for protection, achieved through contracting the rights and imposing or threatening bodily harm against others. Problems of policing seem intractable because changing policing may require dismantling entrenched patterns of inequality in society.

Moreover, we demonstrate that contestation and claims making over policing in unequal settings undermine the promise of a highly inclusive formal institutional design for participation. It is possible that an alternative design, such as one with guaranteed seats for representatives of marginalized groups and limited public comments, could more effectively include groups subject to police repression. Nevertheless, our analysis demonstrates that asymmetric citizenship results from informal exclusionary discourses and practices. It is unlikely that a different institutional design alone would fully prevent exclusionary discourses that sort people into virtuous citizens worthy of safety and security threats deserving bodily harm. Additionally, prior work suggests that police resistance makes participatory security institutions that challenge police authority unlikely to endure (González Reference González2016).

Our analysis of policing raises broader questions about how democratic participation shapes policy decisions about bodily safety and harm, whether it is police use of force or decisions about siting nuclear waste.Footnote 71 Existing research suggests that high inequality leads to the protection of more powerful groups at the expense of the bodily integrity of groups that are marginalized spatially, in terms of resources, and in terms of voice. Unlike policies that affect status or resource allocation, we know relatively little about demand making over policies that affect bodily safety and harm. More research is needed to determine how citizen demands in these high-stakes policy areas can be more equitably channeled by democratic processes.

Finally, this study offers insights into the roots of right-wing authoritarian populism, which often emphasizes protecting the safety of “deserving” citizens by repressing marginalized groups. Right-wing populists, including Donald Trump, Rodrigo Duterte, and Jair Bolsonaro rose to power by denigrating the rights of marginalized groups and calling for extrajudicial violence. Our analysis demonstrates how dehumanizing language can become normalized and legitimated as essential to democracy. Civil society plays a crucial role in constructing new conceptions of citizenship and crystallizing policy agendas at the grassroots level, which are then harnessed by populist leaders (Collins Reference Collins2014, 62). Citizen participation in the CONSEGs may sanitize state violence as not only crucial for public safety but also as a fundamental right for “real citizens”—laying the groundwork for the discursive divisions into good and evil at the heart of populist projects that undermine democracy.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055422000636. The supplementary materials include a narrative of our research process, including limitations on data availability (Appendix A), the CONSEG meeting minutes coding instrument (Appendix B), sample meeting minutes (Appendix C), and sample interview protocols (Appendix D).

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation supporting the findings of this study is openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ZCZ6SG.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful for feedback provided by Jessica Rich, participants in the Ash Democracy Seminar and Faculty Research Seminar at Harvard Kennedy School, and participants in the Canada Research Chair in Participation and Citizenship series. Carla Bezerra, Thaisa Ferreira, Luis González Kompalic, Felicia Huerta, Andrés Lovón Román, Tatiana Machulis, Brooke Moree, Carol Schlitter, and Duda Voldman provided invaluable research assistance.

FUNDING STATEMENT

This research was funded by Colby College Social Science Division Grant #01.2283.6100 Drugs, Security, and Democracy Fellowship (administered by Social Science Research Council and funded by Open Society Foundations); the Mamdouha S. Bobst Center for Peace and Justice at Princeton University; the Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies; the Princeton Program in Latin American Studies; and the Princeton Global Network on Inequality.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The authors declare the human subjects research in this article was reviewed and approved by Princeton University, University of Chicago, and Colby College, and evidence of approvals is found in Appendix A. The authors affirm that this article adheres to the APSA’s Principles and Guidance on Human Subject Research.