Australian English is a regional dialect of English which shares its phonemic inventory with Southern British English through the historical connection with the dialects of the British Isles (in particular London) in the late 18th and early 19th centuries (Cochrane Reference Cochrane, Collins and Blair1989, Yallop Reference Yallop2003, Leitner Reference Leitner2004). Speakers of present-day Australian English are typically those who are born in Australia or who immigrate at an early age when peer influence is maximal.Footnote 1 Such speakers fall into three major dialect subgroups: Standard Australian English, Aboriginal English and Ethnocultural Australian English varieties. Standard Australian English (SAusE) is the dominant dialect and is used by the vast majority of speakers. It is a salient marker of national identity, and is used in broadcasting and in public life. The Aboriginal and Ethnocultural varieties are minority dialects allowing speakers to express their cultural identity within the multicultural Australian context (Cox & Palethorpe Reference Cox, Palethorpe and Cupples2006, Clyne, Eisikovits & Tollfree Reference Tollfree, Blair and Collins2001).

The purpose of this paper is to provide a description of the main features of SAusE. Like all spoken dialects, sociodemographically and stylistically significant accent variation is present in the community. Such variation is chiefly associated with vowel realisation, however, connected speech processes and suprasegmental characteristics also play an extremely important role (see for instance, Ingram Reference Ingram, Bradley, Sussex and Scott1989, Tollfree Reference Tollfree, Blair and Collins2001). The specific detail of these sociostylistic variations present in the dialect will not be offered here as much more work is still required before a solid empirical picture of such variation can be presented. The accent variation that is present amongst speakers of SAusE has traditionally been described with reference to a continuum of broadness, ranging from the most overtly local form (Broad) through to that which bears some resemblance to Received Pronunciation of British English (Cultivated) (Mitchell & Delbridge Reference Mitchell and Delbridge1965). Over the past 40 years, there has been a gradual movement of speakers away from the extremities of this broadness continuum (Horvath Reference Horvath1985) reflecting recent sociocultural change in Australia including post-colonial independence and sociopolitical maturity. The majority of younger speakers today prefer to select speech patterns from the central or General part of the broadness continuum (Harrington, Cox & Evans Reference Harrington, Cox and Evans1997).

By global standards, SAusE displays relative regional homogeneity which may be the result of quite recent white settlement but may also reflect national identity as a stronger psychosocial influence than regional affiliation (Blair Reference Blair and Schultz1993). Recent analyses have, however, revealed some minor regionally distributed contextual variation such as the probabilistic occurrence of vocalised /l/, pre-lateral and pre-nasal vowel modifications, and certain other vowel characteristics (see, for instance, Oasa Reference Oasa, Collins and Blair1989; Cox & Palethorpe Reference Cox and Palethorpe1998, Reference Cox, Palethorpe and Moskovsky2004; Horvath & Horvath Reference Horvath and Horvath2002; Palethorpe & Cox Reference Palethorpe and Cox2003; Butcher Reference Butcher2006). The speaker on the accompanying recorded example which forms the basis of the transcription below is a 31-year-old male who was born in Victoria but now lives in Sydney.

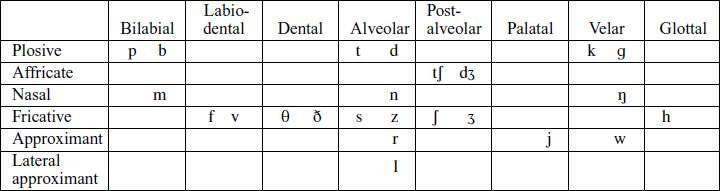

Consonants

Consonantal features have been studied far less rigorously than vowel features (but see Ingram Reference Ingram, Bradley, Sussex and Scott1989 and Tollfree Reference Tollfree, Blair and Collins2001). This is because the consonants display many of the same variations present in other major dialects of English. There are voicing distinctions between stops, affricates and fricatives (except /h/). Syllable-initial voiceless stops are aspirated before vowels in stressed syllables. Voiceless stops are unaspirated when following /s/ in the same syllable. In unstressed and in coda contexts, voiceless stops are usually only weakly aspirated and phase-final codas are often unreleased (Ingram Reference Ingram, Bradley, Sussex and Scott1989). However, there is variation in the degree of aspiration with some speakers inclined to quite strongly aspirate voiceless stops in these contexts, and spirantisation with little closure may also occur, particularly in formal style (Tollfree Reference Tollfree, Blair and Collins2001). Nasal and lateral release of stops preceding homorganic nasals and laterals within or across word boundaries is usual. Syllable-final /t/ preceding an obstruent is typically unreleased. Flapping and glottal reinforcementFootnote

2

of alveolar stops occur variably according to stylistic requirements or speaker-specific idiosyncratic patterns and are not usually obligatory (Ingram Reference Ingram, Bradley, Sussex and Scott1989). Flapping of /t/ and /d/ is tolerated in intervocalic position word-internally preceding weak vowels (as in butter [bɐɾə], water [woːɾə], ladder [læɾə]) and across word boundaries (as in get out [ɡeɾæɔṭ], ride on [ɹɑeɾɔn]) (Evans Reference Evans2003). Flaps may also occur for /t/ before syllabic /l/ and /m/ (as in cattle [khæɾ![]() ], bottle [bɔɾ

], bottle [bɔɾ![]() ], bottom [bɔɾ

], bottom [bɔɾ![]() ]) and before unstressed vowels following /n/ (Tollfree Reference Tollfree, Blair and Collins2001). Glottal stops may function as allophones of /t/ (glottalling) in syllable-final position before syllabic /n/ and other non-syllabic sonorants (for example, button [bɐʔ

]) and before unstressed vowels following /n/ (Tollfree Reference Tollfree, Blair and Collins2001). Glottal stops may function as allophones of /t/ (glottalling) in syllable-final position before syllabic /n/ and other non-syllabic sonorants (for example, button [bɐʔ![]() ], cotton [k

h

ɔʔ

], cotton [k

h

ɔʔ![]() ], butler [bɐʔlə], light rain [lɑeʔɹæɪn] or not now [nɔʔnæɔ]) (Tollfree Reference Tollfree, Blair and Collins2001). It is very unusual for glottal stops to replace /t/ intervocalically, before syllabic /l/ or /m/, or in pre-pausal position. Glottal reinforcement (glottalisation) of voiceless stops is, however, often found, particularly in syllable-final non-pre-vocalic environments, and is commonly accompanied by laryngealisation (Tollfree Reference Tollfree, Blair and Collins2001). For unreleased phrase-final stops, voicing is determined primarily by preceding vowel duration because voiced stops do not typically display periodicity during closure except in intervocalic environments. When final stops are released, the separate closure and burst durations of voiceless stops are greater than for voiced stops (Cox & Palethorpe Reference Cox, Palethorpe and Cupples2006).

], butler [bɐʔlə], light rain [lɑeʔɹæɪn] or not now [nɔʔnæɔ]) (Tollfree Reference Tollfree, Blair and Collins2001). It is very unusual for glottal stops to replace /t/ intervocalically, before syllabic /l/ or /m/, or in pre-pausal position. Glottal reinforcement (glottalisation) of voiceless stops is, however, often found, particularly in syllable-final non-pre-vocalic environments, and is commonly accompanied by laryngealisation (Tollfree Reference Tollfree, Blair and Collins2001). For unreleased phrase-final stops, voicing is determined primarily by preceding vowel duration because voiced stops do not typically display periodicity during closure except in intervocalic environments. When final stops are released, the separate closure and burst durations of voiceless stops are greater than for voiced stops (Cox & Palethorpe Reference Cox, Palethorpe and Cupples2006).

/l/ is realised as [ɫ] in pre-pausal and pre-consonantal positions and is often dark before a morpheme boundary preceding a vowel. There is some suggestion that AusE onset /l/ is more dorsal (i.e. darker) than other varieties of English (Wells Reference Wells1982) although this is yet to be empirically tested. /l/ vocalisation may occur for some speakers in pre-consonantal, syllable-final, and syllabic contexts in words like milk [mɪʊk], hurl [hɜːʊ] and noodle [nʉːdʊ] (Borowsky & Horvarth Reference Borowsky, Horvath, Hinskens, van Hout and Wetzels1997, Borowsky Reference Borowsky, Blair and Collins2001). Vocalisation has the effect of reducing the contrast between certain V and VC syllables such that howl [hæɔɫ] and how [hæɔ] may become homophonous (Palethorpe & Cox Reference Palethorpe and Cox2003). There is also a regionally distributed pattern for this variant with proportionately more speakers from South Australia using vocalised /l/ (Ingram Reference Ingram, Bradley, Sussex and Scott1989, Horvath & Horvath Reference Horvath and Horvath2002).

The palatal approximant /j/ is present after coronals before /ʉː/ (as in new [njʉː]) and when /j/ occurs in alveolar stop or fricatives clusters, yod coalescence typically results such that tune [t![]()

![]() ːn] → [tʃ

ːn] → [tʃ![]() ːn], dune [d

ːn], dune [d![]()

![]() ːn] → [dʒ

ːn] → [dʒ![]() ːn] and assume [əs

ːn] and assume [əs![]()

![]() ːm] → [əʃ

ːm] → [əʃ![]() ːm]. Palatalisation may vary stylistically for some speakers and may also act as a social marker (Horvath Reference Horvath1985).

ːm]. Palatalisation may vary stylistically for some speakers and may also act as a social marker (Horvath Reference Horvath1985).

/r/ is realised as an alveolar approximant [ɹ] with a voiceless allophone occurring in clusters initiated by a stop or fricative. Approximants are generally devoiced following voiceless stops and fricatives but devoicing does not occur when stops are preceded by /s/ (for instance, prey [p![]() æe], but spray [spɹæe]). /tr/ and /dr/ clusters are typically affricated. SAusE is non-rhotic as it does not contain pre-pausal or pre-consonantal /r/. However, in connected speech, linking /r/ (far out [fɐː æɔt] → [fɐːɹæɔt]) is typical, both within words and across word boundaries. Intrusive/epenthetic /r/ (draw it [dɹoː ət] → [dɹoːɹət], draw [dɹoː] → drawing [dɹoːɹ

æe], but spray [spɹæe]). /tr/ and /dr/ clusters are typically affricated. SAusE is non-rhotic as it does not contain pre-pausal or pre-consonantal /r/. However, in connected speech, linking /r/ (far out [fɐː æɔt] → [fɐːɹæɔt]) is typical, both within words and across word boundaries. Intrusive/epenthetic /r/ (draw it [dɹoː ət] → [dɹoːɹət], draw [dɹoː] → drawing [dɹoːɹ![]() ŋ]) is also commonly found. There may be a recent change in progress towards repressing /r/ sandhi as part of a more generalised development affecting the liaison rules that have typically been used for hiatus-breaking of two separate adjacent vowels. Such repression of sandhi involves the substitution of a glottal stop for previously common liaison elements. For example, the egg [ðiː(j)eɡ] → [ðəʔeɡ], to eat [tʉː(w)iːt] → [təʔiːt]. No empirical investigation of this phenomenon in SAusE has occurred to date.

ŋ]) is also commonly found. There may be a recent change in progress towards repressing /r/ sandhi as part of a more generalised development affecting the liaison rules that have typically been used for hiatus-breaking of two separate adjacent vowels. Such repression of sandhi involves the substitution of a glottal stop for previously common liaison elements. For example, the egg [ðiː(j)eɡ] → [ðəʔeɡ], to eat [tʉː(w)iːt] → [təʔiːt]. No empirical investigation of this phenomenon in SAusE has occurred to date.

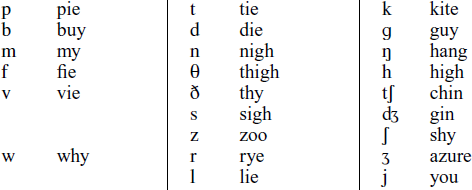

Vowels

The symbols in vowel-space figures and in the left-hand column of the vowel table are from Harrington et al. (Reference Harrington, Cox and Evans1997). This is a revised symbol set for SAusE which was developed to indicate phonetic properties of the vowels more accurately than the earlier system recommended by Mitchell (Reference Mitchell1946). The Mitchell (Reference Mitchell1946) transcription system for vowels more strongly reflects a British rather than an Australian standard due to its historical origins (Clark Reference Clark, Collins and Blair1989, Durie & Hajek Reference Durie and Hajek1994, Harrington et al. Reference Harrington, Cox and Evans1997, Ingram Reference Ingram1995). The revised symbol set adheres to the IPA principle of selecting symbols to represent phonemes that are closest to the corresponding cardinal vowels. It also allows for a more representative picture of SAusE vowel sounds and can provide a solid basis for a detailed phonetic transcription of the variations that are present in the speech community. No detail of the range of phonetic vowel variations present in SAusE is given as this is beyond the scope of the illustration; however, according to Harrington et al. (Reference Harrington, Cox and Evans1997), Broad speakers differ from General speakers primarily with respect to the first element of the diphthongs. In particular, Broad speakers have a more retracted first element of the /ɑe/ vowel (e.g. high) and a more fronted and raised first element of the /æɔ/ vowel (e.g. how). Another vowel that varies systematically with broadness is /iː/, as in heed. This vowel typically displays onglide (delayed target) in SAusE giving it a diphthongal quality [əiː], however the extent and duration of the glide varies considerably and is generally more pronounced amongst the broader speakers (Harrington et al. Reference Harrington, Cox and Evans1997). In SAusE, /iː/ occurs in word-final position in city [sɪtiː]/[sɪɾiː] and happy [hæpiː].

Short vowels are approximately 60% the length of long vowels and diphthongs in standard /hVd/ contexts (Cox Reference Cox2006). Length is explicitly indicated in the transcription system used above as it has contrastive status for some pairs of vowels (for example, /ɐː/ – /ɐ/ as in cart [khɐːt] versus cut [khɐt] and /iː/ – /ɪ/ as in bead [bəiː![]() ] versus bid [bɪ

] versus bid [bɪ![]() ], although this pair also has an additional onglide contrast present in /iː/ as discussed above). The loss of centring glide in many contexts for the centring diphthongs has also resulted in a length contrast between /eː/ – /e/ as in bared [beː

], although this pair also has an additional onglide contrast present in /iː/ as discussed above). The loss of centring glide in many contexts for the centring diphthongs has also resulted in a length contrast between /eː/ – /e/ as in bared [beː![]() ] versus bed [be

] versus bed [be![]() ] and /ɪ/ – /ɪə/ as in bid [bɪ

] and /ɪ/ – /ɪə/ as in bid [bɪ![]() ] versus beard [bɪə

] versus beard [bɪə![]() ]. /ɪə/ (hear [hɪə]) and /eː/ (hair [heː]) have starting points similar to /ɪ/ and /e/, respectively, and, for younger speakers, are often long monophthongs (particularly in closed syllables) or diphthongs with a variable centring glide. It is not uncommon for /ɪə/ and /eː/ in open syllables to be produced as a disyllabic sequence incorporating a full vowel and an unstressed second syllable which has variable realisation often approaching [ɐ], for instance in hear [hɪːɐ] (Harrington et al. Reference Harrington, Cox and Evans1997). The centring diphthong /ʊə/, previously occurring in pure and sure, is infrequently found in the speech of young people and has therefore not been included in the list of phonemes. Words such as pure are typically produced with a disyllabic structure [p

]. /ɪə/ (hear [hɪə]) and /eː/ (hair [heː]) have starting points similar to /ɪ/ and /e/, respectively, and, for younger speakers, are often long monophthongs (particularly in closed syllables) or diphthongs with a variable centring glide. It is not uncommon for /ɪə/ and /eː/ in open syllables to be produced as a disyllabic sequence incorporating a full vowel and an unstressed second syllable which has variable realisation often approaching [ɐ], for instance in hear [hɪːɐ] (Harrington et al. Reference Harrington, Cox and Evans1997). The centring diphthong /ʊə/, previously occurring in pure and sure, is infrequently found in the speech of young people and has therefore not been included in the list of phonemes. Words such as pure are typically produced with a disyllabic structure [p![]() ʉːə], and /oː/ is used in words like sure [ʃoː] resulting in a homophone with shore [ʃoː]. There are some, mainly older speakers, who do continue to use /ʊə/.

ʉːə], and /oː/ is used in words like sure [ʃoː] resulting in a homophone with shore [ʃoː]. There are some, mainly older speakers, who do continue to use /ʊə/.

Schwa has not been indicated owing to its contextual phonetic variability. However, it occurs as the most common vowel in unstressed syllables and does not functionally contrast with /ɪ/ in this context. Words such as rabbit [ɹæbət], carrot [k

h

æɹət], roses [ɹəʉzə![]() ] and Rosa's [ɹəʉzə

] and Rosa's [ɹəʉzə![]() ] all include schwa in the second syllable.

] all include schwa in the second syllable.

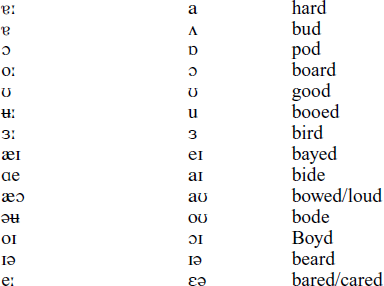

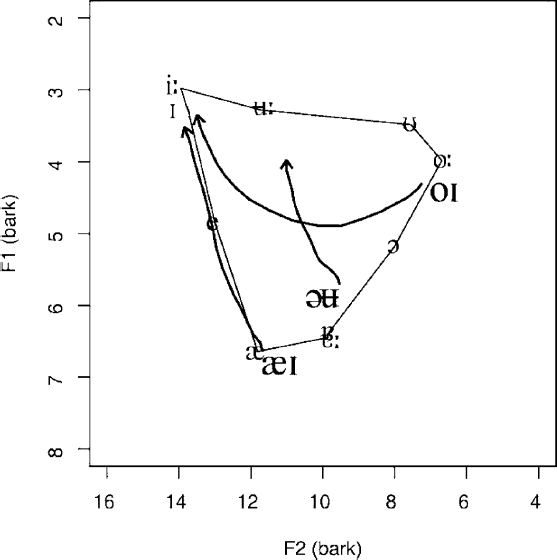

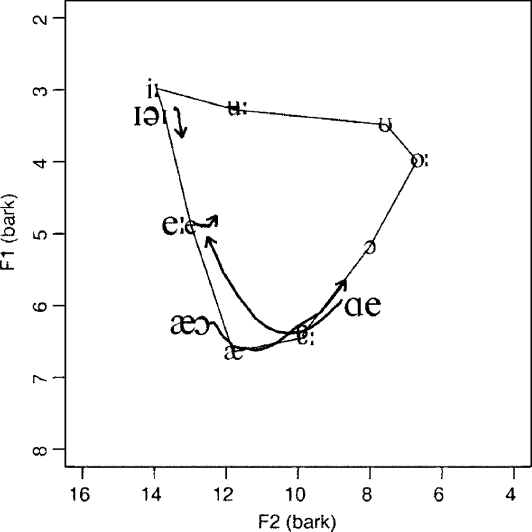

Vowel qualities displayed in the formant plots in figures 1–3 are based on observations of five young adult males from Sydney. The monophthong plot is from vowels in the /hVd/ context and the diphthong plots are from vowels in the /hV/ context. /hV/ has been used for diphthongs to prevent the potential coarticulatory effect of /d/ on the second target.

Various pre-nasal and pre-lateral vowel effects are common in SAusE. /əʉ/ as in coat [k h əʉt] becomes [ɔo] before velarised /l/ (coal [k h ɔoɫ]). Therefore, words like dole [dɔoɫ] and doll [dɔɫ] contrast primarily by vowel duration rather than quality (Palethorpe & Cox Reference Palethorpe and Cox2003). Retraction of /ʉː/ often occurs before [ɫ] so that pull [p h ʊɫ] and pool [p h uːɫ] become differentiated primarily by length whereas in non-lateral contexts such as who'd [hʉːd] and hood [hʊd] there is an additional fronting contrast. The retraction of /ʉː/ before /l/ is considered a regionally distributed feature in SAusE (Oasa Reference Oasa, Collins and Blair1989), but recent change in progress has seen an increased use of this variant among younger speakers generally, thereby reducing the strength of the variant as a regional marker.

There is a further regionally distributed effect for /e/ before [ɫ] which is lowered so that hell and Hal become homophonous for some speakers from Victoria (Cox & Palethorpe Reference Cox, Palethorpe and Moskovsky2004). Epenthetic schwa occurs when long high front vowels and front rising diphthongs occur before velarised or vocalised /l/, as in words like hile [hɑeəɫ] and heel [həiːəɫ] (Palethorpe & Cox Reference Palethorpe and Cox2003). In pre-nasal environments, variable raising of /æ/ (and the first element of /æɔ/) may occur such that can [![]() h

æːn] approaches Ken [

h

æːn] approaches Ken [![]() h

h

![]() ːn] but retains the length of the lower vowel (Cox, Palethorpe & Tsukada Reference Cox, Palethorpe and Tsukada2004).

ːn] but retains the length of the lower vowel (Cox, Palethorpe & Tsukada Reference Cox, Palethorpe and Tsukada2004).

Figure 1 Monophthong vowel formant plot based on citation form /hVd/ words from five male speakers.

Figure 2 Diphthong formant trajectory plot from target 1 to target 2 for the vowels /æɪ/, /əʉ/ and /oɪ/ superimposed onto the monophthong vowel space. Values are from citation form /hV/ words from five male speakers.

Figure 3 Diphthong formant trajectory plot from target 1 to target 2 for the vowels /æɔ/, /ɑe/, /ɪə/ and /eː/ superimposed onto the monophthong vowel space. Values are from citation form /hV/ words from five male speakers.

Suprasegmentals

There has been much interest in the increasing occurrence over the past 30 years of the intonational device known as the high rising terminal (HRT) or tune in Australian English. The HRT is considered a sociophonetically marked intonational pattern associated with declarative utterances which has a particular collaborative function in discourse structure. It may be present in the speech of both males and females (McGregor Reference McGregor2006) but it is important to recognise that HRT users also employ standard falling and fall-rise tunes (Fletcher & Harrington Reference Fletcher and Harrington2001, Fletcher, Stirling, Wales & Mushin Reference Fletcher, Stirling, Wales and Mushin2002, Fletcher, Grabe & Warren Reference Fletcher, Grabe, Warren and Sun-Ah2004).

Transcription of recorded passage

Broad phonemic and narrow phonetic transcriptions are provided. The broad transcription uses vowel symbols from the revised transcription system of Harrington et al. (Reference Harrington, Cox and Evans1997). The narrow transcription provides more detail of allophonic variation and connected speech processes that occur in Standard Australian English.

Broad transcription

Narrow transcription

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to JF for providing the voice for the illustration, to Chris Callaghan for recording the speech samples, to Helen Fraser for early discussions about this illustration and to John Ingram and Andy Butcher for their valuable comments and insights.