1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has generated a truly exogenous, uncertain, and global economic and financial crisis without precedent, which has once again put gender inequality in the spotlight. Understanding how the pandemic has impacted gendered inequalities is of vital importance given that gender equality—one of the European Union's (EU) fundamental values—plays a key role in a country's sustainable development, economic growth, prosperity, and overall quality of life [World Bank (2001), European Commission (2015)].

In this paper, we aim to disentangle the puzzle of whether the global COVID-19 pandemic has put a stop to the important progress made in gender equality in recent decades or, in contrast, has helped to promote certain aspects of gender equality. There is evidence suggesting that the impact of the pandemic on employment, including reductions of working hours, job losses, and furloughs have affected women more severely than men [Cowan (Reference Cowan2020), Kristal and Yaish (Reference Kristal and Yaish2020), Montenovo et al. (Reference Montenovo, Jiang, Lozano Rojas, Schmutte, Simon, Weinberg and Wing2020), Collins et al. (Reference Collins, Landivar, Ruppanner and Scarborough2021), Farré et al. (Reference Farré, Fawaz, González and Graves2021), Hupkau and Ruiz-Valenzuela (Reference Hupkau and Ruiz-Valenzuelain press), Adams-Prassl et al. (Reference Adams-Prassl, Teodora, Marta and Christopher2022)]. These unanticipated disruptions in the labor market are likely to adjust gender-role attitudes to accommodate changing family and employment circumstances. In particular, these shifts in working relations should be particularly impactful for working couples [Thompson and Walker (Reference Thompson and Walker1989)]. Although we are aware that the strongest impact in terms of gender-role attitudes would correspond to transitions from employment to unemployment or inactivity—changes on the extensive margin—the impact caused by changes in working hours—the intensive margin—might be non-negligible. More specifically, we analyze the impact of the pandemic on the within-household gender gap in the number of paid work hours, among full-time employed couples, across three stages: strict lockdown (second quarter of 2020), de-escalation (third quarter of 2020), and partial closures (fourth quarter of 2020).

The focus on Spain is based on two aspects. First, Spain is one of the European countries that has been hardest hit by the pandemic. Second, the country's convergence toward gender equality in employment rates has been one of the highest and fastest in Europe, with an increase in the relative female–male employment rate of 0.51 in 1995 (the lowest in the EU-15 countries) to 0.84 in 2020 as reported in Eurostat.

Various factors associated with the COVID-19 pandemic might have exacerbated existing gender inequalities in the labor market. First, several female-dominated industries (e.g., air travel, tourism, retail, accommodation, and food and beverage service activities) were among the hardest hit by lockdown measures. Second, school and daycare center closures during lockdown increased childcare needs, and the ability to outsource childcare through informal channels (e.g., grandparents) was greatly reduced. Thus, mothers and fathers were together confronted with the immediate need to simultaneously fulfill both work and childcare obligations, which has involved substantial changes to both partners' work arrangements. Although men have increased their contribution to housework, and even more so to childcare, in recent decades, they still fail to match the contribution of women. As women still perform most of the unpaid work and caregiving in the majority of EU countries [Sullivan (Reference Sullivan2006), García-Mainar et al. (Reference García-Mainar, Molina and Montuenga2011), Wall et al. (Reference Wall, Cunha, Atalaia, Rodrigues, Correia, Vladimira Correia and Rosa2017)], it is likely that they also take on a greater share of the new childcare and housework responsibilities derived from the situational demands of the pandemic. Consequently, many working mothers might have been forced to reduce their paid work hours, thus increasing the within-couple gender gap in work hours.

However, other counteracting forces might have promoted gender equality in the labor market, especially when returning to work in the so-called “new normality.” First, many sectors in the labor market are increasingly allowing their employees to work remotely [Hickman and Saad (Reference Hickman and Saad2020), EIGE (2021), Seiz (Reference Seiz2021)], which is likely to persist in the future, thus leading to more flexible work arrangements. Insofar as women very often take on the bulk of most chores, this increased workplace flexibility stands to favor female labor supply [Alon et al. (Reference Alon, Matthias, Olmstead-Rumsey and Tertilt2020)]. Second, the substantial shift toward remote working has forced men to stay at home, which might have changed traditional gendered behavior patterns as regards intra-couple strategies to reconcile work and family [Alon et al. (Reference Alon, Matthias, Olmstead-Rumsey and Tertilt2020), Hupkau and Petrongolo (Reference Hupkau and Petrongolo2020)]. The physical proximity of men to their homes may have led them to make greater contributions to housework and childcare, especially in families where women are employed in critical sectors (e.g., grocery stores, pharmacies, healthcare workers, etc.). In this respect, evidence in Spain suggests that families where both parents maintained their jobs by resorting to telework or flexibility during the state of emergency established a more co-responsible distribution of tasks than those who did not [Seiz (Reference Seiz2021)]. Lastly, the pandemic is increasing the demand for jobs in some female-dominated sectors such as health and social care, which appear to be the most stable sectors looking forward.

An important contribution to the growing literature that has looked primarily at the short-term effects of the COVID-19 crisis [Andrew et al. (Reference Andrew, Cattan, Costa Dias, Farquharson, Kraftman, Krutikova, Phimister and Sevilla2020), Del Boca et al. (Reference Del Boca, Oggero, Profeta and Rossi2020), Heggeness (Reference Heggeness2020), Sevilla and Smith (Reference Sevilla and Smith2020), Collins et al. (Reference Collins, Landivar, Ruppanner and Scarborough2021), Oreffice and Quintana-Domeque (Reference Oreffice and Quintana-Domeque2021), Adams-Prassl et al. (Reference Adams-Prassl, Teodora, Marta and Christopher2022), Farré et al. (Reference Farré, Fawaz, González and Graves2021), among others] is that our analysis—based on Spanish microdata—encompasses not only the strict lockdown period (the first state of emergency from March 14 to June 20), but also the subsequent stages of the pandemic up to the end of 2020. Although we are aware that this extension of the period of analysis does not fully cover the so-called period of “new normality,” it allows us to shed more light on the short-term and potential medium-term effects of the crisis on labor market gender inequality, particularly in terms of paid working hours. Moreover, we place special emphasis on the influence of children and their age, both partners' occupational status, and the essential or non-essential nature of the job performed, in the terms established by Royal Decree 463/2020 of March 14 (RD March 14, hereafter).

The interest of this paper is twofold. First, it contributes to the large body of literature that examines the impact of recessions on gender inequality. Evidence from past economic crises suggests that recessions often affect men and women's employment differently, with men historically being the biggest losers [Heathcote et al. (Reference Heathcote, Violante and Perri2010), Rubery and Rafferty (Reference Rubery and Rafferty2013), Addabbo et al. (Reference Addabbo, Rodríguez-Maroño and Gálvez2015)]. Indeed, the empirical evidence suggests the existence of an added worker effect during the 2008 financial crisis that provoked an increase in female work hours [Sahin et al. (Reference Sahin, Song and Hobijn2010), OECD (2012)]. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has turned things upside down. Whereas in most crises, the spotlight tends to be on the economy and paid employment, in this crisis the unpaid care work in the home has gained unprecedented visibility, particularly as it is performed alongside paid work and other commitments. Due to social norms, especially in the Mediterranean countries, it is assumed that women are more likely to shoulder most of the extra unpaid work generated by the pandemic [EIGE (2021)]. This might have widened the within-household gender gap in the number of paid work hours, thus rolling back women's economic gains of recent decades. This is not only important as concerns gender equality, but also regarding the ability of households to offset potential income losses caused by the economic recession.

Second, this paper is also of interest as it focuses on Spain, a country that has seen Europe's worst job loss figures in the first half of 2021 (nearly three times higher than other European countries). Moreover, Spain already had a relatively more vulnerable labor market compared to other European countries due to its infamously high involuntary temporary employment figures. Notwithstanding, the furlough scheme (known by its acronym “ERTE” in Spanish) and other measures introduced by the Spanish government have significantly helped to contain the number of job losses. However, once this state-funded job protection program ends, the real impact of the pandemic on employment will come to light. Lastly, women in Spain suffer one of the highest motherhood penalties in Europe [Castaño et al. (Reference Castaño, Martín, Vázquez and Martínez2010), Hupkau and Ruiz-Valenzuela (in press)]. As a consequence, the pandemic might have exacerbated the already precarious labor market situation of working mothers in the country.

In our analysis, we use the Coarsened Exact Matching (CEM, [Iacus et al. (Reference Iacus, King and Porro2009), (Reference Iacus, King and Porro2012)]) algorithm based on attaching each household from the Covid period with its “twin” household in the pre-Covid period. A primary challenge to evaluating the outcome of non-randomized interventions is self-selection bias. Thus, the underlying idea behind CEM is to replicate what would be a random experiment where the treatment and the control group have the same covariate distributions to ensure that they are comparable [Stuart (Reference Stuart2010)]. Another source of selection bias could be caused by selection into full-time employment. Thus, to correct for selection bias, we followed Heckman's (Reference Heckman1979) two-step statistical approach, one for the selection mechanism (probability of both partners being employed full-time) and the other one for the outcome variable (the within-household gender gap in paid work hours). Finally, to identify the causal effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the outcome variable, we used the difference-in-differences (DiD) method, one of the most popular research designs to evaluate causal effects of policy interventions.

Our main results suggest that during the strict lockdown period there has been a tendency to fall back on traditional family gendered patterns to manage the work–life balance, especially when young children are present in male-headed households. However, this regression toward a less egalitarian-gendered division of paid and unpaid work appears to be a short-term consequence of the pandemic. The nature of sector of activity (essential or non-essential) has also played a key role in shaping the within-household gender gap in paid work hours among full-time employed couples in Spain. More precisely, our results reveal that during the period of partial recovery amid partial closures (2020.Q4), the gender gap has increased in male-headed households with female partners employed in non-essential sectors.

The paper is organized as follows. In the next section, we summarize the related research and the institutional context in Spain. The data set and main variables are presented in section 3, while section 4 describes the econometric approach. The main results are presented in section 5. Finally, we provide a discussion together with some policy suggestions and the main conclusions in section 6.

2. The Spanish labor market and the COVID-19 pandemic

There is a rapidly growing body of research aimed at analyzing the role the COVID-19 pandemic has played and may continue to play in widening social and labor inequalities.

A large number of studies have focused on different facets of gender inequality: from those that examine the role of the pandemic in mental health [Adams-Prassl et al. (Reference Adams-Prassl, Teodora, Marta and Christopher2020), Béland et al. (Reference Béland, Brodeur, Mikola and Wright2020), Etheridge and Spantig (Reference Etheridge and Spantig2020)], subjective well-being [Brodeur et al. (Reference Brodeur, Clark, Flèche and Powdthavee2021)], social interactions [Alfaro et al. (Reference Alfaro, Ester, Lamersdorf and Saidi2020)], and domestic violence [Brülhart and Lalive (Reference Brülhart and Lalive2020), Béland et al. (Reference Béland, Brodeur, Haddad and Mikola2021)] to those that examine the impact of the pandemic in terms of time use, division of labor, and labor market prospects [Alon et al. (Reference Alon, Matthias, Olmstead-Rumsey and Tertilt2020), Galasso and Foucault (Reference Galasso and Foucault2020), Hupkau and Petrongolo (Reference Hupkau and Petrongolo2020), Farré et al. (Reference Farré, Fawaz, González and Graves2021)]. This paper aims to contribute to this last stream of literature by focusing specifically on the within-household gender gap in paid work hours in Spain.

Recent empirical evidence suggests that lockdown measures have had a significant impact on employment, including reductions in working hours, furloughs, and work-from-home arrangements [Coibion et al. (Reference Coibion, Gorodnichenko and Weber2020), Gupta et al. (Reference Gupta, Montenovo, Nguyen, Lozano Rojas, Schmutte, Simon, Weinberg and Wing2020), Brodeur et al. (Reference Brodeur, Clark, Flèche and Powdthavee2021)]. Amid this unprecedented uncertainty, many companies have been forced to close or reduce their employees' number of working hours. Emerging evidence suggests that women have been affected more severely by these developments [Adams-Prassl et al. (Reference Adams-Prassl, Teodora, Marta and Christopher2020), Cowan (Reference Cowan2020), Kristal and Yaish (Reference Kristal and Yaish2020), Montenovo et al. (Reference Montenovo, Jiang, Lozano Rojas, Schmutte, Simon, Weinberg and Wing2020), Collins et al. (Reference Collins, Landivar, Ruppanner and Scarborough2021), Farré et al. (Reference Farré, Fawaz, González and Graves2021)]. However, the economic downturn caused by the global public health crisis goes beyond the economic effects of the lockdown period. One year after the initial outbreak, the consequences of the pandemic are still unfolding. As regards its impact on gender equality in the labor market, there is still no clear evidence of whether the pandemic has served as an exogenous equalizer by reshaping traditional household gender relations and the division of labor, or whether it has contributed to widening existing patterns of gender inequality.

Spain was hit early and hard by the pandemic, leading it to become one of the countries with the strictest lockdown measures in Europe. Faced with the gravity of the situation, the Spanish government declared a state of emergency on March 14, 2020 and, among other measures, imposed restrictions on the free movement of people and declared the closure of schools, shops, and other establishments, except for essential services. On March 30, the government ordered a further toughening of the lockdown measures and ordered all non-essential activities such as construction to cease until April 9. Overall, from March 15 through to early May, Spain remained under the strictest lockdown in Europe, with the nationwide lockdown lasting until midnight on June 20, 2020. The impact of this complete shutdown of certain sectors and the increase in family responsibilities caused by the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic are likely to have looked very different for mothers and fathers.

By the end of summer 2020, the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic had already caused an unprecedented shock to the Spanish economy, which entered a technical recession in the second quarter of 2020 after recording a 17.9% fall in gross domestic product (GDP) in the first quarter of 2020.Footnote 1 Moreover, the weaknesses of the Spanish labor market were brought to light once again. According to the Spanish Labor Force Survey (EPA), nearly 1.1 million jobs were lost in the second quarter of 2020,Footnote 2 and the number of Spanish households with all active members out of work rose to 1.14 million,Footnote 3 up from 992,000 in the same period in 2019. Two factors might be largely to blame for these figures. First, lockdown was much stricter in Spain than in other European countries, as evidenced by Google's mobility reports. And second, the fact that the Spanish economy is more heavily dependent than other EU economies on the tourism sector, which has been hardest hit by the restrictions.

In October 2020, the Spanish government declared a new nationwide state of emergency—which expired on May 9, 2021—and introduced a national curfew to counter the resurgence of coronavirus cases. Local authorities also imposed travel restrictions across various regions. Amid this new state of emergency, the Spanish labor market exhibited a slight recovery in the fourth quarter of 2020, with a rise in employment of 167,400 according to the EPA. However, after this modest recovery, the restrictions imposed in the third wave of the pandemic again took their toll on Spain's labor market, which lead to an increase in registered unemployment of 44,436 in February 2021. In summary, after more than a year battling the COVID-19 pandemic, Spain's labor market is still feeling the strain with 401,000 more people out of work since the first restrictions were introduced in March 2020. Moreover, in March 2021 nearly 750,000 people were still on the government's ERTE furlough scheme, and unemployment steadily rose to over 4 million for the first time in 5 years.

It is also important to highlight that unlike the Great Recession of 2008, where male-dominated industries such as construction and manufacturing were the most severely affected, this dangerously unique COVID-19 economic crisis might have had a harsher impact on female workers. Sectors overexposed to the collapse in economic activity (hospitality, personal services, leisure activities, etc.) absorb a sizeable share of female employment [Adams-Prassl et al. (Reference Adams-Prassl, Teodora, Marta and Christopher2020), Alon et al. (Reference Alon, Matthias, Olmstead-Rumsey and Tertilt2020)]. Consequently, women's employment is likely to be hit more severely than men's by the current crisis.

Like other Mediterranean countries, Spain accounts for higher shares of employment in female-dominated sectors that have been heavily hit by the lockdown. According to a recent study based on the EPA, 29% of women work in locked-down sectors, compared to 21% of men.Footnote 4 Thus, the more restrictive lockdown measures adopted in Spain, together with the country's employment and economic reliance on such specialized sectors, might have exacerbated the negative consequences of the pandemic on female labor market prospects. Moreover, the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic introduced an unprecedented context characterized by the lack of both formal and informal childcare provision. Unlike other European countries, such as the UK and Germany where childcare facilities and schools remained open during lockdown for workers employed in essential services, this was not an option in Spain. Given that women bear the brunt of the extra childcare and housework originated by the lockdown, it is likely that the pandemic has had devastating long-term effects on their labor market prospects.

However, the shift toward more flexible work arrangements favored by the pandemic could have enhanced gender equality if men have increased the time they devote to child-rearing and chores. As both men and women have been forced to work at home during the pandemic, fathers are now more exposed to the scale and scope of housework and childcare. This situation might have reshaped how families divide paid work and unpaid household responsibilities toward a more equitable division of domestic work, thus reducing gender gaps in paid work hours.

Recent evidence shows that men who work from home participate more in domestic labor on an equal footing [Carlson et al. (Reference Carlson, Petts and Pepin2021)]. Farré et al. (Reference Farré, Fawaz, González and Graves2021) estimated the impact of the lockdown period on the household distribution of childcare and housework by gender in Spain. They found that although the sharing of household chores increased during lockdown, the burden of the work still increased for women during the period and remained higher than that of men.Footnote 5 If such a redistribution of duties within the household has persistent effects on gender roles and the division of labor, then it is likely that this change in social norms will contribute to reducing the gender gap in paid work hours. In this respect, previous evidence suggests that fathers who take on more household responsibilities (such as childcare) for a limited period of time may also take on a greater share in the longer term.Footnote 6

Another important factor that might have reduced the gender gap in paid work hours is the increased demand for jobs in female-dominated sectors, such as healthcare and professional and scientific activities, not only during the lockdown period but also in subsequent months. Indeed, looking to the future, these sectors currently appear to be the most stable.Footnote 7

3. Data set and main variables

3.1 Data set: the Spanish Labor Force Survey (EPA)

Data for this study are drawn from the Spanish Labor Force Survey (EPA), which constitutes the Spanish sample of the European Union Labor Force Survey. This quarterly survey is the most important statistical database for the analysis of labor participation in Spain. It is conducted on a sample of around 60,000 households per quarter and involves approximately 180,000 individuals. The survey contains highly comprehensive information on the personal and labor characteristics of each household member.

The availability of data up to the end of 2020 enables us to significantly contribute to the emerging literature on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on gender inequalities in the labor market. More precisely, we make use of the last three quarters of 2019 and 2020 in order to distinguish between two periods: pre-Covid (from 2019.Q2 to 2019.Q4) and Covid (from 2020.Q2 to 2020.Q4).Footnote 8 Thus, the Covid period covers three distinct stages: the early stage that primarily covers the lockdown period, or state of emergency (2020.Q2); the de-escalation period, also called the “new normality” (2020.Q3); and the partial economic recovery amid partial lockdowns and closures, travel restrictions, and enforcement measures (2020.Q4).

Our initial sample comprises adults aged 24–64 cohabiting in heterosexual-couple households (married or not) from both the pre-Covid and Covid periods. For identification purposes we take into consideration the potential imbalance in the characteristics of individuals from both periods. Thus, to account for these potential estimation biases, we follow a methodological strategy based on attaching each household from the Covid period with its “twin” household in the pre-Covid period. The underlying idea is to replicate what would be a random experiment where the treatment and the control group have the same covariate distributions to ensure that they are comparable [Stuart (Reference Stuart2010)].

More specifically, we used the CEM algorithm proposed by Iacus et al. (Reference Iacus, King and Porro2009, Reference Iacus, King and Porro2012) and Blackwell et al. (Reference Blackwell, Iacus, King and Porro2009). CEM is a matching method designed to improve causal inference by reducing imbalance between the treated and control groups in relation to a set of pre-treatment control variables and by grouping observations into categories. Unlike propensity score matching, the CEM method ensures that there are no differences in relevant variables between the treatment and control units. There is evidence that CEM has a greater capacity than more commonly used matching methods in terms of its ability to reduce imbalance, model dependence, estimation error, bias, variance, mean square error, and other criteria [see Blackwell et al. (Reference Blackwell, Iacus, King and Porro2009), Iacus et al. (Reference Iacus, King and Porro2009, Reference Iacus, King and Porro2012), King and Nielsen (Reference King and Nielsen2019)].Footnote 9

A key issue is to achieve a balance that enables the definition of the control group to be refined as much as possible while obtaining a sufficient percentage of households who meet the required characteristics. The greater the number of variables used to define the strata, as well as the greater the number of subcategories within each variable, the more precise the definition of the control group will be. However, this implies greater difficulty in finding a sufficient sample of units (households) from both periods (pre-Covid and Covid) who belong to the same stratum. In particular, we consider the gender of the household reference personFootnote 10 (hereafter referred to as household head or household responsible person) and the average age of household partners.Footnote 11 In addition, we include a variable to capture the presence of children and the age of the youngest child (no children, 0–3 years, 4–6 years, 7–12 years, 13–15 years, and over 16). We also consider different household categories according to the level of education of both partners, distinguishing between lower secondary or less, upper secondary, and tertiary education, which results in nine different types of households by level of education. Finally, we consider the possible immigrant status of the household head and the NUTS-2 region of residence.Footnote 12 This combination of variables enables us to identify 5,743 matched strata and obtain a matching rate of 79% of total households in the sample, resulting in a total of 61,352 matching households in each period.Footnote 13 Around 42% of the households comprise full-time employed couples. In 13.8% of the sample, both partners are employed but at least one of them has a part-time job. Finally, the remaining 44.2% of the sample comprises households where at least one of the partners is unemployed or out of the labor force.

Starting with this initial sample (pooled data for pre-Covid and Covid periods), we focused our analysis on households where both partners are employed full-time, given that full-time workers are those who may have experienced the greatest difficulties in reconciling work with family during the pandemic.Footnote 14 However, in order to partially account for the fact that the pandemic might have increased transitions from full-time employment to unemployment/inactivity or part-time employment that might have had an impact on the probability of being in full-time employment in the Covid period with respect to the pre-Covid period, we control for sample selection into full-time employment (see more details in section 4). Although we are aware that this does not fully capture the pandemic's impact in terms of employment relations on the extensive margin, we partially overcome this problem by using this sample selection approach. If the pandemic has increased employment-to-unemployment transitions, for instance, we would expect this effect to be partially captured in our selection equation.

3.2 Gender gap and main explanatory variables

Our dependent variable is the within-household gender gap in actual (paid) working hours (Gap), calculated as the difference between men and women's actual number of hours worked in the survey reference week. More specifically, we used the following question in the survey: “In the reference week, how many hours did you work in this job? (do not include time for lunch).” Two aspects must be highlighted here. First, we only included hours worked in the individual's main job considering both paid and unpaid overtime.Footnote 15 Second, the actual number of hours worked could be different than the “usual weekly hours of work.” Around 4% of the individuals in our sample work more hours than usual and 12% work less.Footnote 16

The analysis based on the actual, instead of usual, number of weekly hours of work enables us to study the influence that an exogenous shock like the pandemic may have on individuals' labor supply and, consequently, on the within-household gender gap in paid work hours. It should be noted that the “actual weekly hours worked” is only observed for those who worked during the survey reference week. On average, the main reasons for not having worked during the reference week are holidays (around 47%), illness (around 25%), or being on a furlough scheme (around 20%). Once we eliminated couples where at least one partner did not work during the reference week, the end result was a pooled sample of 36,516 heterosexual couples with both partners working full-time during the reference week (12,060 in Q2; 10,930 in Q3; and 13,526 in Q4 of 2019 and 2020).

The average within-household gender gap for this final sample is around 2.7 h (see Table 1). No significant differences are observed by period. Only a slight reduction can be observed in the gap during the strict lockdown period (2020.Q2), which is driven by a greater reduction in men's compared to women's hours worked. Moreover, the average gender gap is very similar in both male-headed (who account for 64% of the sample) and female-headed households.

Table 1. Average within-household gender gap in weekly actual work hours

Note: Own calculations based on EPA microdata (2019.Q2–2019.Q4 and 2020.Q2–2020.Q4). Sample: “twin” heterosexual-couple households with adults aged 24–64 (married or not) with both partners working full-time. Military occupations and the cities of Ceuta and Melilla are excluded.

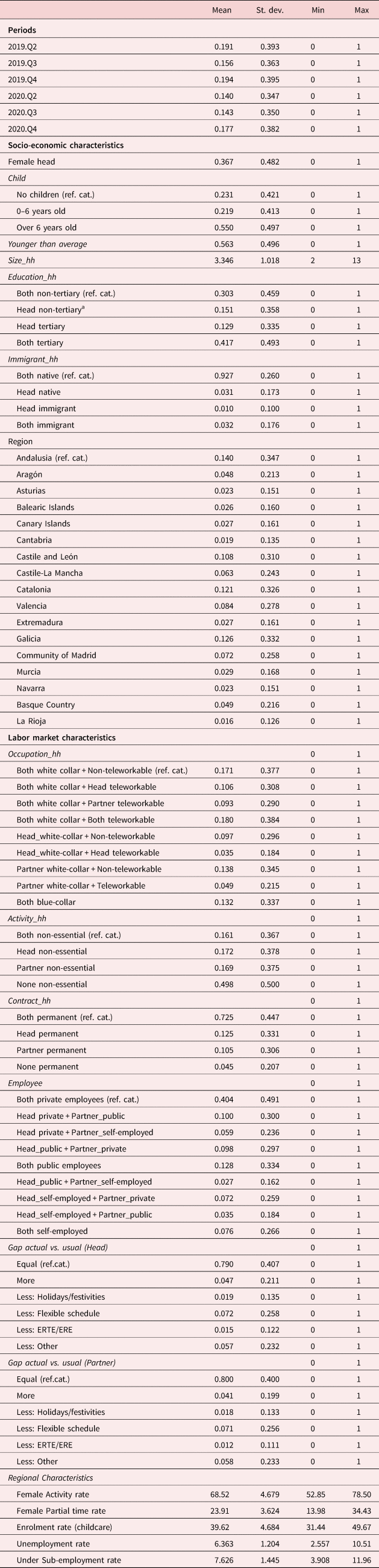

As regards the explanatory variables, we consider the most common variables used in the related literature to account for the individual and household socio-economic determinants of the within-household gender gap in paid work hours. See Table 2 for the main descriptive statistics.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of covariates

a Head refers to the person responsible for the household.

Note: Own calculations based on EPA microdata (2019.Q2–2019.Q4 and 2020.Q2–2020.Q4). Sample: “twin” heterosexual-couple households with adults aged 24–64 (married or not) with both partners working full-time. Military occupations and the cities of Ceuta and Melilla are excluded.

In particular, we include presence and age of children, average age of the household partners, and level of education.Footnote 17 For children in the household (Child), we consider a three-value variable that captures households without children, those in which the youngest child is under 6 years old, and those in which the youngest child is over 6 years old. A total of 23.1% of the sample do not have children, and in 55.03% of households the youngest child is over 6 years old. We opted for this classification instead of number of children to capture the fact that young children (those with non-compulsory education) are more time intensive. We also included the household size (Size_hh), which is 3.35 individuals on average. To control for the mean age of the household partners, we included a binary variable (Younger than average) to capture the fact that the average age of the partners is below the sample average (47 years old in the total sample). Education of both partners may also be an important determinant of gender differences in paid work hours. In this respect, we categorized households (Education_hh) according to the level of education including higher and lower than tertiary education, which resulted in four groups. In 30.3% of the total sample, both partners in the couple have lower than tertiary education, while in 41.73% of couples both have tertiary education. Additionally, we classify households into four different groups according to the nationality (native or immigrant) of both partners (Immigrant_hh). A total of 92.7% of the households comprise two native partners, while immigrant couples amount to just 3.2% of the total sample.

We also account for both partners' labor market characteristics in terms of their occupation considering two dimensions: (i) white-collar or blue-collar occupationFootnote 18; and (ii) teleworkable or non-teleworkable occupation as described in Dingel and Neiman (Reference Dingel and Neiman2021).Footnote 19 It is found that among blue-collar occupation there is no one with a teleworkable occupation. Then, we just consider white-collar occupations either teleworkable or not. The variable (Occupation_hh) thus comprises combinations of head and partner with white-collar teleworkable occupations, with white-collar non-teleworkable and blue-collar occupation (nine categories of households). In our total sample, 54.39% of households are composed of two white-collar workers, with 17.1% being in non-teleworkable occupations and 18.0% in teleworkable occupations. Only 13.2% comprise two blue-collar workers.

Likewise, we categorize households into four types (Activity_hh) according to the household head's and partner's activity (essential or non-essential).Footnote 20 In 49.7% of households, both partners work in an essential activity, while couples where both partners perform non-essential jobs comprise only 16% of the sample. The type of contract of both partners is also likely to condition the within-household gender gap in work hours. Thus, we classify households into four types (Contract_hh) based on the type of contract—either permanent or temporary—of both partners. Of the total sample, 72.5% comprises households where both the household head and the partner have permanent contracts, while households where both partners have a temporary contract amount to just 4.5%. Finally, we consider a three-value variable (Employee) to capture whether both partners are either private or public sector employees, or self-employed workers. In this case, the most frequent household category is where both partners are private sector employees (40.4%). In 12.8% of households both partners are employed in the public sector, while in 7.7% both are self-employed.

Moreover, to avoid ad-hoc high or low gender gaps due to inconsistencies in the number of actual hours worked during the reference week, we constructed the variables [Diff. w. usual (Head) and Diff. w. usual (Partner)]. These variables capture whether the head or their partner actually worked less, the same, or more hours than usual and the main reason for doing so. The most prevalent category is where the number of actual work hours equals the number of usual work hours (around 80%), followed by the category in which one of the partners in the couple (head or partner) works less hours than usual (around 16%). Having a flexible schedule is the main reason for working less hours. Finally, we consider region fixed effects and control for the specific activity of both partners.Footnote 21

3.3 Heterogeneous gender gap by household characteristics

In this section, we examine whether the gender gap and its evolution during the Covid period with respect to the pre-Covid period exhibit heterogeneous patterns according to household characteristics.

As highlighted in the Introduction, we focus our attention on the presence of children and the children's age, as well as two characteristics of each partner's employment situation: occupation and activity. The reasons behind this choice are as follows. First, having children is time-consuming, especially when children are very young. Hence the presence of children and children's age are likely to condition parents' labor supply and consequently the within-household gender gap in paid work. Second, sector of activity has been shown to be relevant especially during the strict lockdown and partial closures, insofar as some activities suffered total/partial lockdowns, while others were deemed essential. Finally, opportunities for teleworking in some specific occupations, especially during lockdown, also played a key role in determining the number of actual paid work hours.

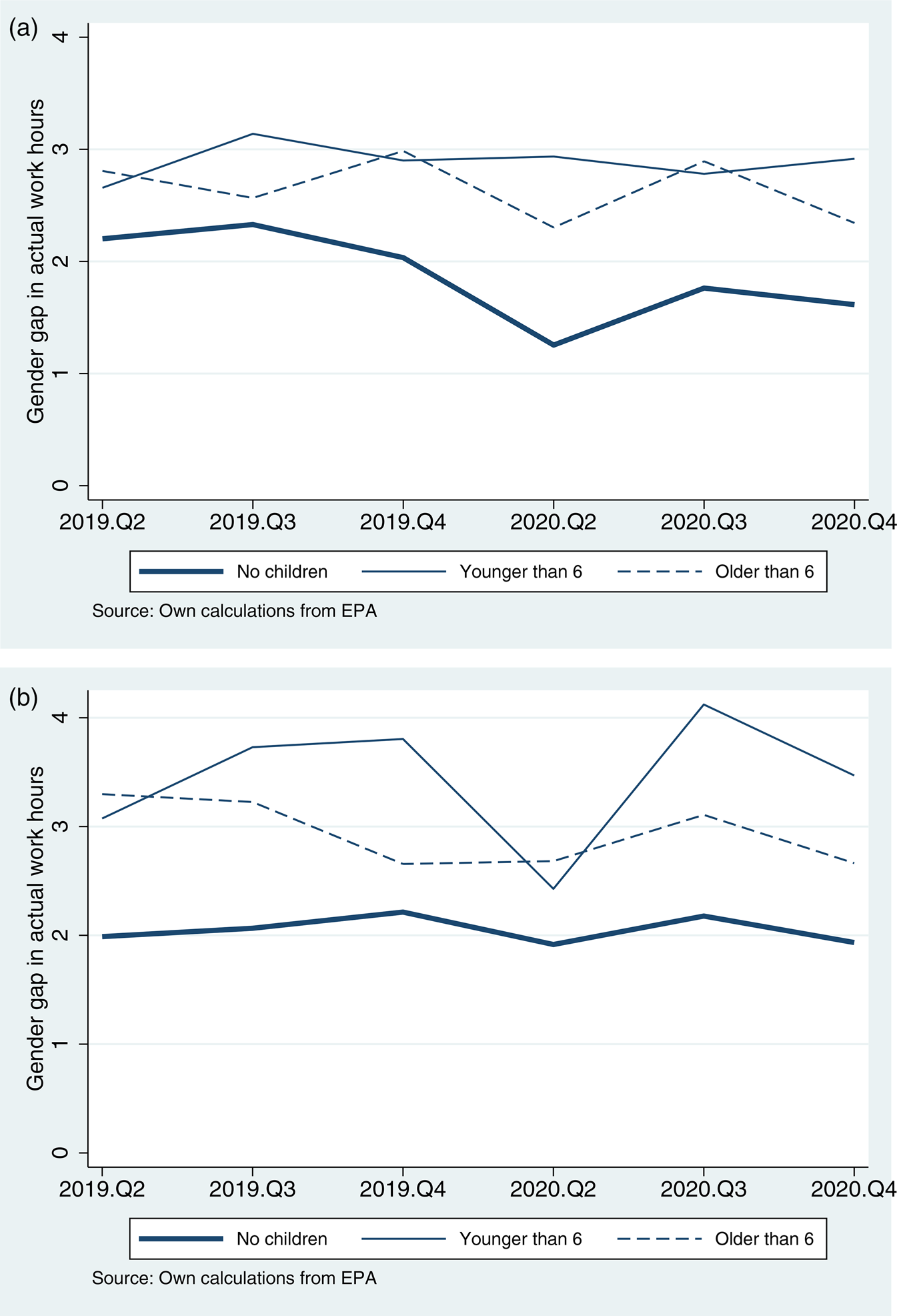

As observed in Figure 1, the gender gap is notably higher in households with children, especially in those where the youngest child is under 6 years old. Moreover, for the three types of households (without children, where the youngest child is under 6 years old, and where the youngest child is over 6 years old), the gender gap is higher in female-headed than in male-headed households. This result seems to suggest that when females are the responsible person of the household, their male partners try to compensate for this situation by working more hours.

Figure 1. Gender gap (actual work hours) by the presence of children and children's age.

Note: Households are classified as follows: no children (23.1%), with the youngest child under 6 years old (55.03%), with the youngest child over 6 years old. Specific numbers corresponding to these figures are available upon request.

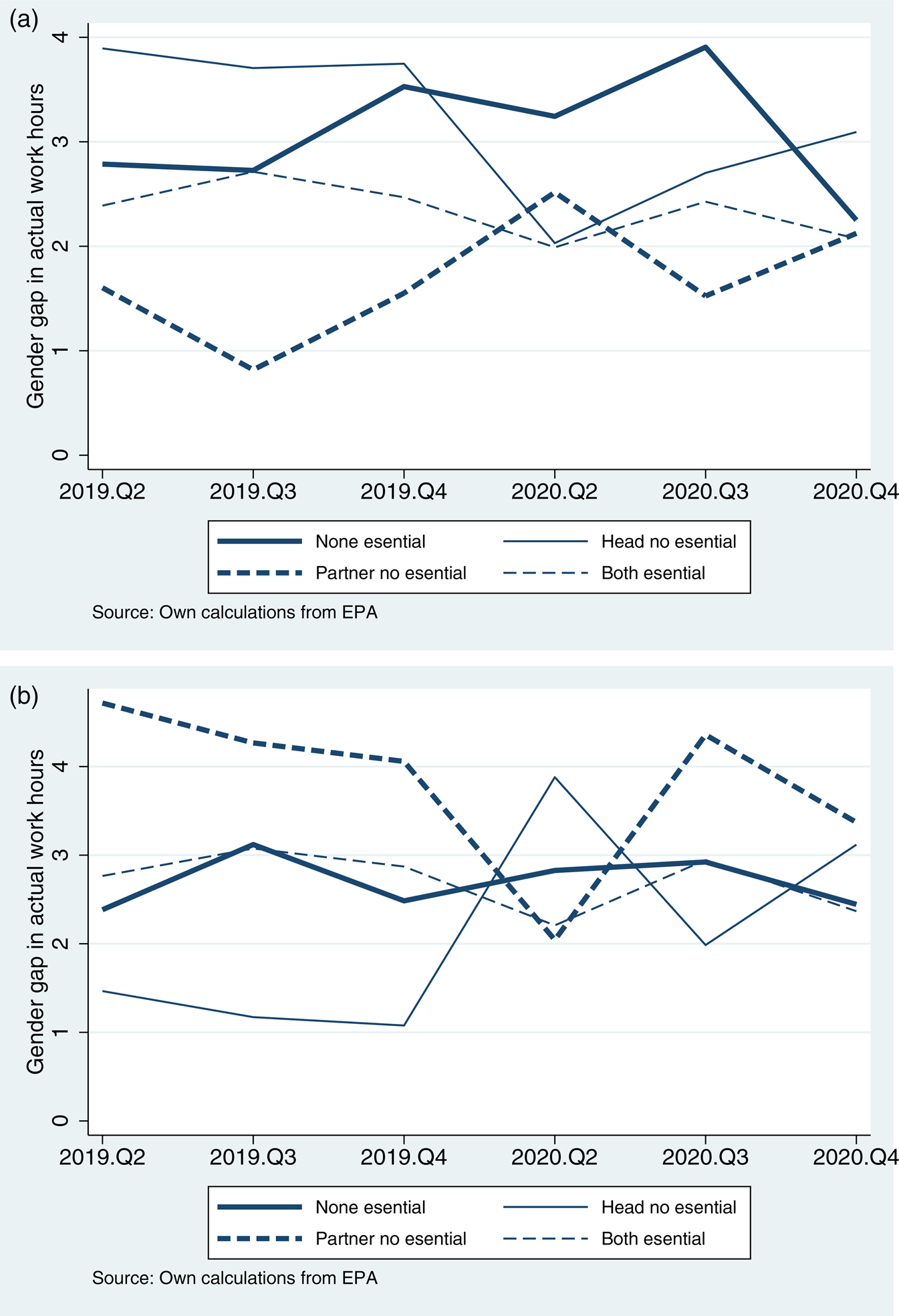

The evolution of the gender gap also displays different patterns according to the employment characteristics of both partners. As shown in Figure 2, during the strict lockdown period, the gender gap decreased in households where at least one of the partners worked in a white-collar occupation, regardless of the gender of the household head. In contrast, the gender gap increased in blue-collar households (where both male and female partners worked in this type of occupation), with women working less and men working more paid hours than in the corresponding pre-Covid period. A plausible explanation for this finding could be that white-collar occupations are more likely to be telecommuting-capable [Alon et al. (Reference Alon, Matthias, Olmstead-Rumsey and Tertilt2020), Anghel et al. (Reference Anghel, Cozzolino and Lacuesta2020), Collins et al. (Reference Collins, Landivar, Ruppanner and Scarborough2021)], which might have contributed to a more equitable distribution of paid and unpaid work within the household [Del Boca et al. (Reference Del Boca, Oggero, Profeta and Rossi2021)]. Conversely, in households where both partners are employed in blue-collar occupations, traditional work–family arrangements seem to predominate.

Figure 2. Gender gap (actual work hours) by occupation.

Note: Each partner in the couple is identified as a white-collar or a blue-collar worker. This information is combined by household. Specific numbers corresponding to these figures are available upon request.

Finally, Figure 3 exhibits differences in the gender gap according to the essential or non-essential character of the activity—as established in RD March 14—performed by both members of the couple. During the three stages of the Covid period (lockdown, de-escalation, and new partial closures), the gender gap decreased in those households where both partners worked in essential services.Footnote 22 It is worth noting that during the strict lockdown period, the gender gap decreased in male-headed households where the male partner was employed in a non-essential job and his female partner in an essential job. In contrast, the gender gap increased significantly during this same period in female-headed households where the female was employed in a non-essential activity and her male partner in an essential job. However, these effects are partially reverted in the de-escalation (2020.Q3) and partial closures (2020.Q4) phases.

Figure 3. Gender gap (actual work hours) by economic activity.

Note: Households are classified into categories according to household head and partner's activity (essential or non-essential). Specific numbers corresponding to these figures are available upon request.

In summary, the preliminary descriptive analysis suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic has reduced the within-household gender gap in relation to paid work hours. Nevertheless, the influence of the pandemic appears to be linked to family characteristics as well as to some job features. To account for the specific effects of these characteristics, we followed the econometric approach described in the following section.

4. Econometric approach

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are the gold standard method for evaluating the effects of COVID-19. However, observational studies are an alternative when an RCT is not feasible. A primary challenge to evaluating the outcome of non-randomized interventions is self-selection bias. Individuals who participated in the labor market during lockdown and the subsequent stages of de-escalation and partial closures may differ from those who participated before the onset of the pandemic. As we explained in the previous section, we applied CEM to improve causal inference by reducing imbalance between the treated (Covid) and the control (pre-Covid) groups in relation to a set of pre-treatment control variables.

Another source of selection bias could be caused by selection into full-time employment. Unobservable factors that affect the probability of both partners working full-time are likely to be correlated with the unobservable factors that affect the outcome variable (the within-household gender gap in paid work hours). Thus, to correct for selection bias, we followed Heckman's (Reference Heckman1979) two-step statistical approach. Hence, our model includes two equations: (1) the regression equation considering the mechanisms determining the outcome variable (the within-household gender gap in paid work hours); and (2) the selection equation considering the mechanisms determining the selection process (probability of both partners being employed full-time).Footnote 23, Footnote 24

Finally, to identify the causal effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the outcome variable, we used the DiD method, one of the most popular research designs to evaluate causal effects of policy interventions. Thus, the estimated model is as follows:

where $Gender\_gap_{ij}^{\rm \ast }$![]() is a latent endogenous outcome variable (within-household gender gap in paid work hours in household i at period j) with observed counterpart $Gender\_gap_{ij}$

is a latent endogenous outcome variable (within-household gender gap in paid work hours in household i at period j) with observed counterpart $Gender\_gap_{ij}$![]() (only observed when both partners work full-time). $Full\_time_{ij}^{}$

(only observed when both partners work full-time). $Full\_time_{ij}^{}$![]() is an indicator function reflecting whether both partners in household i work full-time at period j. Following the DiD methodology, we measured the potential causal structural break triggered by COVID-19 by including a dummy variable (2020.Qj). This is a binary variable that takes the value of 1 for the corresponding quarter Qj, j = 2, 3, 4 in 2020 and 0 for the same period in 2019. The periods comprise strict lockdown (j = 2, second quarter), de-escalation (j = 3, third quarter), and partial closures (j = 4, fourth quarter). Vectors ${\boldsymbol X}_{ij}^{}$

is an indicator function reflecting whether both partners in household i work full-time at period j. Following the DiD methodology, we measured the potential causal structural break triggered by COVID-19 by including a dummy variable (2020.Qj). This is a binary variable that takes the value of 1 for the corresponding quarter Qj, j = 2, 3, 4 in 2020 and 0 for the same period in 2019. The periods comprise strict lockdown (j = 2, second quarter), de-escalation (j = 3, third quarter), and partial closures (j = 4, fourth quarter). Vectors ${\boldsymbol X}_{ij}^{}$![]() and ${\boldsymbol Z}_{ij}^{}$

and ${\boldsymbol Z}_{ij}^{}$![]() contain the exogenous variables and ɛ ij and ν ij are zero mean error terms with E[ɛ ij|ν ij] = 0. As we will explain later in section 5, we conduct separate estimations by quarter.

contain the exogenous variables and ɛ ij and ν ij are zero mean error terms with E[ɛ ij|ν ij] = 0. As we will explain later in section 5, we conduct separate estimations by quarter.

For the purpose of this study, we are interested in parameter β, which measures the effect of the Covid period during each stage of the pandemic (strict lockdown, de-escalation, and partial closures) on the gender gap. We are also interested in different patterns arising from the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic across different types of households according to the presence of children and children's age, and each partner's occupation and activity. Thus, we also included interactions of these characteristics with the variable 2020.Qj.

To complete our identification strategy, we took into account the potential sample selection bias. It is likely that the samples of full-time employees in the corresponding quarters of 2019 and 2020 are not random if, for instance, the job destruction caused by lockdown measures in 2020 has hit some specific groups harder than others, such as young and less-educated workers, or if the impact of the pandemic has not been homogenous across regions. Apart from socio-demographic characteristics (age, education, household size, nationality, and presence of children) we include in the selection mechanism the following explanatory variables: female activity rate, female part-time rate, the enrolment rate in public childcare facilities for children under 6 years old, the unemployment rate, and the underemployment rate.Footnote 25 These variables capture characteristics at the regional levelFootnote 26 that may act as exogenous restrictions. In other words, they may affect the likelihood that both members of the couple work full-time, but do not influence the within-household gender gap in work hours.

5. Results

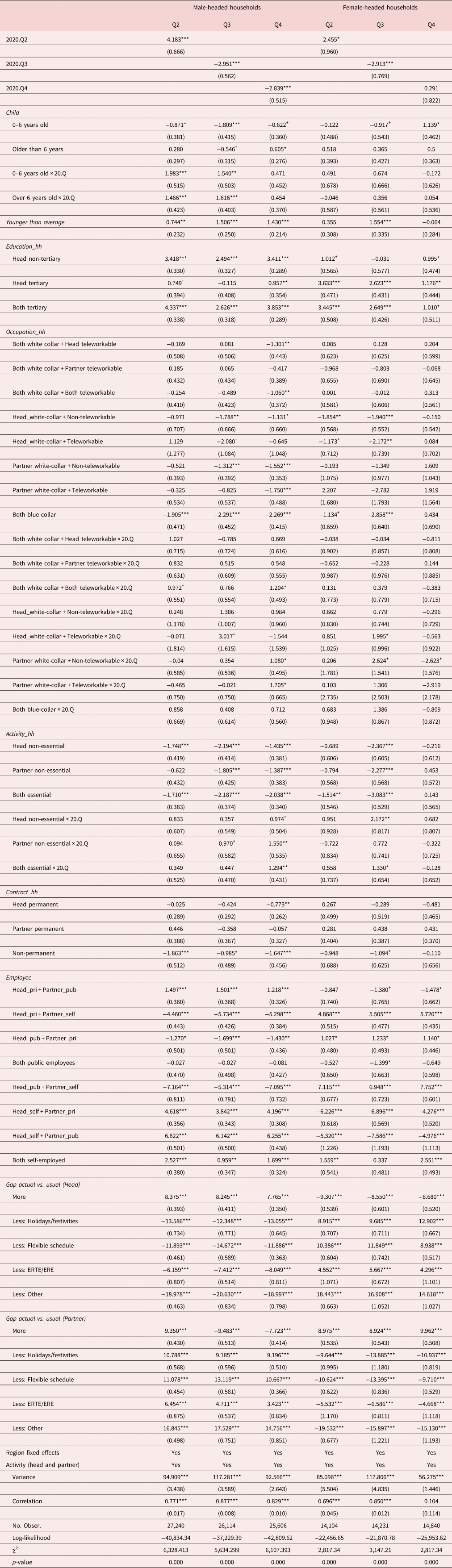

Table 3 shows the results corresponding to the outcome equation derived from the estimation of the model presented in equations (1) and (2).Footnote 27 We conducted separate estimations for quarters Q2, Q3, and Q4 using the corresponding quarters in 2019 as the reference category. This option offers the possibility to easily display the influence of socio-economic characteristics by quarter and, more importantly, to avoid the seasonality effectsFootnote 28 that may confound with pandemic effects. Nonetheless, we cannot test whether the different socio-economic characteristics had (statistically) different contributions to the gender gap in the different phases of COVID times. Moreover, insofar as the gender of the household head might condition the impact of the pandemic on gender differences in paid work hours, we performed separate estimations for male- and female-headed households.

Table 3. Estimation results (within-household gender gap in work hours)

+p < 0.1, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Robust standard error in parenthesis.

Note: Estimations with the Heckman model based on EPA microdata (2019.Q2–2019.Q4 and 2020.Q2–2020.Q4). Sample: “twin” heterosexual-couple households with adults aged 24–64 (married or not) with both partners working full-time. Military occupations and the cities of Ceuta and Melilla are excluded.

The first notable finding that should be highlighted is that the lockdown stage (2020.Q2) has significantly reduced the within-household gender gap in paid work hours with respect to the same quarter in 2019. This result seems to partially contradict the recent literature suggesting that the lockdown measures implemented with the onset of the pandemic increased gender inequality in the labor market [Adams-Prassl et al. (Reference Adams-Prassl, Teodora, Marta and Christopher2020), Andrew et al. (Reference Andrew, Cattan, Costa Dias, Farquharson, Kraftman, Krutikova, Phimister and Sevilla2020), Del Boca et al. (Reference Del Boca, Oggero, Profeta and Rossi2020), Heggeness (Reference Heggeness2020), Sevilla and Smith (Reference Sevilla and Smith2020), Collins et al. (Reference Collins, Landivar, Ruppanner and Scarborough2021), Oreffice and Quintana-Domeque (Reference Oreffice and Quintana-Domeque2021), Farré et al. (Reference Farré, Fawaz, González and Graves2021), among others]. However, we should keep in mind that our analysis focuses on a sample of full-time employed couples and that the estimation results are free of sample selection bias.Footnote 29 If selection into full-time employment was not accounted for (hereafter the exogenous modelFootnote 30), we would get the standard, but biased, result that the lockdown measures have increased within-household gender differences in paid work hours.

In terms of the size of the effect, note that the average gender gap in 2019 is around 2.66 h in male-headed households (see Table 1). However, the pandemic has offset and even reversed this figure. In particular, the period of strict lockdown led to a decrease in the gender gap of around 4.18 h, thus reverting the original situation in favor of females.Footnote 31 Moreover, our analysis reveals that the abovementioned decrease in the gender gap goes beyond the strict lockdown phase (both in 2020.Q3 and 2020.Q4) in male-headed households, while the gender gap in female-headed households has only gone toward the “new normality” period (2020.Q3).

Our estimation results reveal two important findings. First, the main determinants of the impact of the pandemic in terms of within-household gender gap in paid work hours are presence of children, and the essential or non-essential nature of the activities performed by both partners. However, once we controlled for sector of activity, occupational status did not seem to have influenced the effect of the pandemic on the gender gap. Second, the effects of the pandemic are heterogeneously distributed throughout the different stages: strict lockdown (2020.Q2), de-escalation period or “new normality” (2020.Q3), and the period of partial economic recovery amid partial closures (2020.Q4).

As regards the presence of children, a possible interpretation of our results is that the pandemic would has altered the strategies that full-time employed couples with children were using to manage work and family. Taking as a reference household with no children, the within-household gender gap in paid work hours is, in general, lower and significant in male-headed households where the youngest child is under 6 years old. However, during the strict lockdown period, the estimated effect of the presence of children under 6 in male-headed households turned positive, thus increasing the within-household gender gap in work hours.Footnote 32 Nonetheless, this appears to be a short-term effect as the effect is no longer significant in the fourth quarter of 2020. For the de-escalation and the recovery period, the gap in work hours is non-existent when children under 6 are present. This result might be partially explained by Government's decision of reopening schools after summer vacations. Although Spain experienced the strictest lockdown in Europe up to June 20th, 2020, primary and high schools stayed open from September 2020. Several factors contributed to this. First, the strict protocols imposed in schools to prevent contagion, such as the use of face masks for students over the age of six, social-distancing measures, and the preventive quarantine of classes when a positive case is detected in a class bubble. Second, milder weather conditions than in other countries, which have allowed the possibility to have windows opened. Third, the broad consensus on the importance of in-class learning. Finally, hygiene protocols as well as the low contagion rates among children have also kept the number of coronavirus cases in schools low.

In male-headed households with children over 6, which initially displayed similar patterns to households without children, the negative impact of the pandemic in terms of gender equality (i.e., an increased gender gap in paid work hours) still holds during the first two periods under consideration. Looking at the three stages of the pandemic, we observe that, irrespective of the age of children, the effect of COVID-19 disappears in the stage of new partial closures (2020.Q4). We did not find a specific pattern for female-headed households in terms of how the pandemic and the presence of children have altered work–family management strategies.

Even though our database does not have information about the time allocated to non-paid work, a feasible explication of the findings regarding the presence of children would suggest that the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic may have produced a change toward less egalitarian attitudes in the allocation of time between work and childcare. According to this idea, this result would be in line with some papers in the literature that find that women have carried a heavier load than men in the provision of childcare during the COVID-19 pandemic, and that these increased childcare responsibilities are associated with a reduction in working hours [Alon et al. (Reference Alon, Matthias, Olmstead-Rumsey and Tertilt2020), Del Boca et al. (Reference Del Boca, Oggero, Profeta and Rossi2020, Reference Del Boca, Oggero, Profeta and Rossi2021), Collins et al. (Reference Collins, Landivar, Ruppanner and Scarborough2021), Shockley et al. (Reference Shockley, Clark, Dodd and King2021), Zamarro and Prados (Reference Zamarro and Prados2021), among others]. This would suggest that the pandemic has caused a considerable setback in gender equality. However, this regressive effect on gender equality seems to be primarily a short-term effect, as suggested by the results for the fourth quarter.

Another important factor that could have potentially conditioned the impact of the pandemic on the within-household gender gap in paid work hours is the nature of economic activity (either essential or non-essential in the terms established by RD March 14) performed by both partners.Footnote 33 Taking households where both partners are employed in non-essential sectors as a reference, the within-household gender gap in paid work hours is, in general, lower in any other male-headed household category. The effect of both partners' sectors of activity did not suffer significant changes during the strict lockdown and de-escalation periods (2020, Q2 and Q3). However, during the stage of partial economic recovery amid partial closures (2020.Q4), an increase can be observed in the gender gap in all household categories with respect to the corresponding pre-Covid period. This increase offsets the initial situation, leading to an equal number of actual hours in all households except when both partners are essential workers.Footnote 34 For female-headed households, there is no tangible effect from the COVID-19 pandemic that alters the overall impact of the household categorization in terms of essential and non-essential jobs. The only exception is female-headed households where females are employed in non-essential jobs, which, during the “new normality” period (2020.Q3), have experienced an increase in the gender gap that completely offsets the initial negative gender gap.

In terms of both partners' occupational status, we did not observe any specific effect of how the pandemic might have altered the impact of job characteristics on the gender gap in work hours. This result is somewhat surprising as we would expect to find some differences across occupations depending on the feasibility of working remotely.Footnote 35 However, two things should be kept in mind. First, we already accounted for the essential or non-essential nature of the sector of activity. This classification is in fact highly correlated with the type of occupation. More specifically, it is likely that telecommuting-capable occupations predominate in non-essential sectors, since in most cases having worked in a non-essential activity—especially during the strict lockdown—was possible when workers could work from home.

Moreover, the effect of other characteristics of the partners considered potential explanatory factors of the within-household gender gap in paid work hours is noteworthy. In particular, the public sector appears to be an important determinant of gender inequalities. In male-headed households—taking households where both partners are employed in the private sector as a reference—the gender gap is significantly reduced when males are public sector employees and their female partners are either employed in the private sector or self-employed. In the latter case, the size of the effect amounts to around a 7-h decrease in the gender gap. In contrast, there is a significant increase in the gender gap when female household heads work in the public sector and their male partners are either private sector employees or self-employed (7 h in Q2 and Q3, and near 8 in Q4). The only situation in which the gender gap is not statistically different from when both spouses are employed in the private sector is when both work in the public sector. Lastly, the situation where we observed an increase in the gender gap with respect to the reference category, irrespective of the household head's gender, is when both partners are self-employed. In this case, the estimated within-household gender gap in paid work hours exceeds the reference category by approximately 2 h.

Another important determinant of the gender gap in paid work hours is the level of education of both partners. Overall, the gender gap is wider when a female head or partner has attained tertiary education. However, the effect in quantitative terms is especially high in male-headed households.

In summary, the presence of children and sector of activity of both partners have acted as significant drivers of the within-household gender gap in paid work hours during the pandemic. Overall, the results may suggest that the pandemic would have reverted the situation of some households toward a less equitable gendered division of paid and unpaid work, especially in male-headed households.

Finally, we analyzed the selection into full-time employment of both partners with respect to other possibilities (including part-time employment, unemployment, and inactivity).Footnote 36 The estimation results—reported separately by quarter and gender of household head—show that during 2020 it was less likely that both partners were occupied full-time. Second, the presence of young children seems to decrease the probability that both partners are occupied full-time. However, when the youngest child is over 6 years old, the probability that both work full-time increases with respect to households without children. This result is consistent with the fact that older children are more independent, thus permitting both parents who may be at a more advanced career stage to work full-time. Household size only seems to reduce the probability that both partners work full-time in male-headed households. Third, households where males and females have lower than tertiary education exhibit the lowest likelihood of both partners working full-time. Fourth, households where both partners are native are the most likely to work full-time. Finally, some regional employment characteristics (our exclusion restrictions) influence couples' labor supply decisions. For example, our results show that the higher the female part-time employment rate, the lower the probability that both partners are employed full-time. In contrast, living in regions with a higher female activity rate increases the likelihood of both partners working full-time, especially in male-headed households.

6. Discussion and conclusions

This paper provides evidence that the COVID-19 pandemic has had an impact on the within-household gender gap in paid work hours among full-time employed couples in Spain. More specifically, a possible interpretation of our results would be that during the strict lockdown period there has been a tendency to fall back on traditional family gendered patterns to manage work and family, especially in male-headed households with young children. However, this apparent regression toward a less egalitarian-gendered division of paid and unpaid work appears to be a short-term consequence of the pandemic. The nature of the sector of activity, essential or non-essential in the terms established by RD March 14, has also played a key role in shaping the within-household gender gap in paid work hours among full-time employed couples in Spain. More precisely, our results reveal that during the stage of partial recovery amid partial closures (2020.Q4), the gender gap increased in all male-headed household categories, except when both partners perform non-essential jobs. This increase was large enough to offset the initial situation, leading to an equal number of work hours for both partners, except in the case where both members were employed in essential jobs.

The results of this paper may help to design targeted policy measures intended to prevent ongoing job losses and the potential increase in labor market and social inequalities due to the pandemic. For specific cases where the COVID-19 pandemic has widened the within-household gender gap in paid work hours, it is essential that policymakers adopt well-designed measures to mitigate the potential risks of women, especially mothers, disengaging from the labor market. This would entail a number of policy measures, such as preserving employment ties, or promoting novel work–family management strategies that depart from the “neo-traditional” division of labor where women are the primary caretakers in order to encourage men to shoulder their fair share of the unpaid work in the home. Overarching areas for action might also include better recognition of the unpaid work for both men and women and a rebalancing of responsibilities between men and women, as well as closing the gender gap in digital inclusion.

The design of intervention policies should also take into consideration the changing nature of work due to the COVID-19 pandemic. On the one hand, the pandemic has produced a sharp increase in the demand for technical competencies in some sectors such as healthcare compared to the pre-crisis period. On the other hand, transversal skills, such as “communication skills” and “teamwork” seem to remain in strong demand in the topmost frequently advertised positions in the labor market. Thus, at least in the short term, government efforts to reduce the damaging effects of the pandemic and the potential increase in gender inequalities should also be aimed at supporting the acquisition of specific skills strongly associated with certain types of work that are in high demand in the labor market. Moreover, to ensure long-term recovery, retraining and upskilling policies should primarily be aimed at low-skilled and more vulnerable workers. Despite these policy suggestions, it is important to highlight that the long-term impact of the recession is still hard to predict at this stage. If restrictions on movement are imposed again, vaccines and other treatments are not fully effective, or disruptions to economic activity are maintained in some areas, then economic recovery could be delayed.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/dem.2022.15.

Data

In this paper, we made use of EPA data. This data set is available paying, but I cannot provide it due to the privacy clause I signed in the contract with Spanish Statistical Office. Computer programs to get the results from original data set are provided.

Financial support

Financial support from Spanish Government R&D&r Programmes through project PID2019-111765GB-I00 and the Andalucía Regional Government through project PY18-4115 is gratefully acknowledged.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare none.