Introduction

The homelessness crisis in Canada affects a heterogeneous group of individuals, including persons of varying ages (Liu & Hwang, Reference Liu and Hwang2021; Piat et al., Reference Piat, Polvere, Kirst, Voronka, Zabkiewicz and Plante2015). Population aging compounded by other socio-economic issues, such as the lack of affordable housing, is expected to contribute to more older adults over the age of 50 facing homelessness in Canada and globally (Culhane et al., Reference Culhane, Treglia, Byrne, Metraux, Kuhn and Doran2019; Edmonston & Fong, Reference Edmonston and Fong2011; Rowland & Hamilton, Reference Rowland and Hamilton2016). Within the Canadian context, some research has focused specifically on older homeless persons who encounter particular health and social challenges (Barken & Grenier, Reference Barken and Grenier2014; Grenier et al., Reference Grenier, Barken, Sussman, Rothwell, Bourgeois-Guérin and Lavoie2016a; Reynolds et al., Reference Reynolds, Isaak, DeBoer, Medved, Distasio and Katz2016). Recent studies have also recognized the complex and diverse pathways into homelessness that exist amongst this group of older adults. Growing numbers of individuals are experiencing homelessness for the first time later in life (Burns & Sussman, Reference Burns and Sussman2019; Petersen & Parsell, Reference Petersen and Parsell2015), though ethnographic work by Grenier (Reference Grenier2021) provides an understanding of late-life homelessness because of disadvantages experienced over a lifetime caused by a series of system failures.

Homeless individuals in their fifties usually begin exhibiting age-related health impairments that occur a decade later in the general population, thus “older” homeless adults are considered to include persons who are 50 years of age and over (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Hemati, Riley, Lee, Ponath and Tieu2017; Hahn, Kushel, Bangsberg, Riley, & Moss, Reference Hahn, Kushel, Bangsberg, Riley and Moss2006; McDonald, Dergal, & Cleghorn, Reference McDonald, Dergal and Cleghorn2007). Many older homeless adults have a variety of chronic conditions and complex care needs (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Hemati, Riley, Lee, Ponath and Tieu2017; Garibaldi, Conde-Martel, & O’Toole, Reference Garibaldi, Conde-Martel and O’Toole2005; Hahn et al., Reference Hahn, Kushel, Bangsberg, Riley and Moss2006; Håkanson & Öhlén, Reference Håkanson and Öhlén2016). Geriatric syndromes connected to higher rates of mortality, disability, and utilization of acute care services are also common (Brown, Kiely, Bharel, & Mitchell, Reference Brown, Kiely, Bharel and Mitchell2012; Tschanz et al., Reference Tschanz, Corcoran, Skoog, Khachaturian, Herrick and Hayden2004). Older homeless individuals are confronted with barriers accessing health services, including mistrust and fear of health care professionals, fear of their illness and/or not recognizing its severity, not possessing a health insurance card, and being unable to pay for medications (Daily Bread Food Bank, 2001; McDonald et al., Reference McDonald, Dergal and Cleghorn2007; McDonald, Dergal, & Cleghorn, Reference McDonald, Dergal and Cleghorn2004).

Older homeless adults face unique social circumstances, including smaller social networks with fewer intimate ties to family than the general population, and thus experience more social isolation (Grenier et al., Reference Grenier, Sussman, Barken, Bourgeois-Guérin and Rothwell2016b; McDonald et al., Reference McDonald, Dergal and Cleghorn2004). Older adults are also more susceptible to violence and threats to their safety on the streets and in shelters, which are typically inaccessible and/or not adequately equipped to meet the needs of older individuals (Burns, Reference Burns2016; Lee & Schreck, Reference Lee and Schreck2005; Serge & Gnaedinger, Reference Serge and Gnaedinger2003).

Within the limited body of literature on homelessness in older adults, there is a need for additional research on the perspectives of service and health care providers supporting this population. Since older homeless adults may be less likely to receive support from family, frontline providers often form a key component of their reduced social support networks (McDonald et al., Reference McDonald, Dergal and Cleghorn2004). By working closely with their clients, they also witness firsthand the health and social challenges faced by this subpopulation. Gaining a better understanding of providers’ perspectives working with older homeless adults could inform strategies on how to further support providers in their work and, in turn, ultimately improve services and programs for their clients. While service providers’ perspectives have been included in some research centred on homelessness in older adults (Canham et al., Reference Canham, Davidson, Custodio, Mauboules, Good and Wister2019; Gonyea, Mills-Dick, & Bachman, Reference Gonyea, Mills-Dick and Bachman2010; Kaplan et al., Reference Kaplan, Sudore, Arellano Cuervo, Bainto, Olsen and Kushel2020; McDonald et al., Reference McDonald, Dergal and Cleghorn2004; Sussman, Barken, & Grenier, Reference Sussman, Barken and Grenier2020; Watson, Reference Watson2010), these studies suggest that a more holistic understanding of health care providers’ perspectives working with this population is warranted, specifically in outreach settings where individuals experiencing long-term homelessness frequently access care.

This paper focuses on health care providers’ perspectives based on working with older homeless adults in outreach settings within a mid-sized metropolitan area located in southern ON, Canada. Provider perspectives were captured by looking at how they work in their roles with older homeless adults, as well as the challenges and rewards encountered in their work. This small exploratory study aimed to fill some of the knowledge gaps discussed above, as well as provide some preliminary recommendations for policy, practice, and future research.

Methods

Research Design

We conducted a qualitative investigation and thematic analysis of health care providers’ perspectives working with older homeless adults in outreach settings. Our work was informed by an interpretive descriptive approach, which emphasized the generation of knowledge that can be applied within practice and clinical contexts (Thorne, Reference Thorne2008; Thorne, Kirkham, & MacDonald-Emes, Reference Thorne, Kirkham and MacDonald-Emes1997).

Study Setting

This study took place within a mid-sized metropolitan area in southern ON, Canada. Similar to other Canadian mid-sized cities, chronic homelessness is growing in the region where our study was conducted, and this issue has been further exacerbated by the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Within this mid-sized city, outreach services for individuals facing homelessness were offered through community organizations and agencies that often partnered together to reach marginalized residents. For example, the local community health centre partnered with shelters and a soup kitchen to offer primary care on-site through weekly drop-in clinics. While the region offered outreach services and programs tailored to youth, this was not the case for older adults experiencing homelessness. More broadly, homeless services in the region were constructed for the general adult population and did not offer specialized services for older adults.

Recruitment

Between December 2019 and August 2020, health care providers who work with older homeless adults in outreach settings were recruited to participate in individual interviews. Purposeful sampling was used to identify health care providers who could share their firsthand experiences (Palinkas et al., Reference Palinkas, Horwitz, Green, Wisdom, Duan and Hoagwood2015). We aimed to recruit a diverse sample of health care providers who work with homeless individuals in differing capacities with varying years of experience working in their roles. Due to the relatively small pool of potential participants in the region (approximately 40 providers), a snowball approach was used to recruit providers from participants’ professional networks (Patrick, Pruchno, & Rose, Reference Patrick, Pruchno and Rose1998). Before data collection began, the interview guide was piloted with a nurse practitioner who worked on an outreach primary care team. The Director of Housing for a shelter in the region was provided with study materials, which were used to contact providers in their professional network.

Data Collection

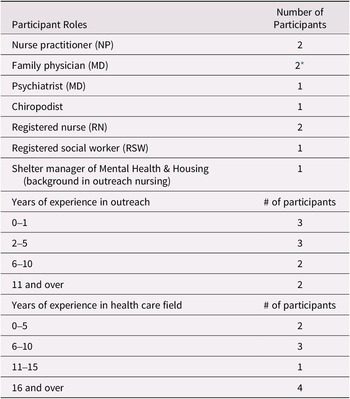

Interested health care providers who met the study criteria were invited to schedule in-person or telephone interviews with the primary researcher, a female graduate student with qualitative methodological training. Ten (n = 10) individual interviews were conducted in-person (n = 8) and by telephone (n = 2) with health care providers working in outreach settings in various roles. See Table 1 for a summary of participant characteristics. Participants included: four nurses, two family physicians, one psychiatrist, one chiropodist, one social worker, and one shelter manager with a background in outreach nursing.

Table 1. Participant characteristics

* One of the family physicians was retired.

Participants included health care professionals working for different community organizations and agencies, serving individuals facing homelessness. Three participants (n = 3) worked for a local community health centre and were part of an interprofessional primary care team that partnered with community agencies to provide services at several outreach sites, such as shelters and drop-in clinics. Two participants (n = 2) were a part of a family health team, and as a part of their role worked on an interprofessional team that offered care to medically and socially complex clients, using an outreach-informed approach. Two participants (n = 2) worked exclusively at a primary care clinic that supported individuals accessing services at the on-site soup kitchen, and one participant (n = 1) worked as a consultant for this clinic alongside their hospital-based role. The remaining two participants (n = 2) worked on specialized mobile outreach teams and met clients where they were in the community.

Interviews were audio-recorded, and in-person interviews were conducted in a private room at the participants’ workplace or in a public setting. While most interviews were 30-45 minutes in duration, two participants who had worked extensively in outreach provided 90-minute interviews. Prior to the interview, the study’s letter of information was reviewed, and consent was obtained. Health care providers were first asked some general background information questions pertaining to their position, as well as experience in current and previous roles. Next, participants were asked a series of open-ended questions, such as: In your role, how do you work with older homeless adults in the community?; Can you tell me more about the challenging experiences that you encounter working with older homeless adults?; and Can you tell me more about the rewarding experiences you encounter working with older homeless adults? In line with the underlying principles of semi-structured interviews, probes were used to follow up on participants’ responses (Roulston, Reference Roulston2010). Supplementary field notes recorded in a journal were taken during and after the interviews. At the end of each interview, health care providers received modest compensation through a gift card and were asked whether they would like to participate in a follow-up discussion to provide feedback on preliminary findings.

Data Analysis

A thematic analysis of the data followed an inductive approach, consisting of working with the data to derive concepts, explanations, or themes related to the phenomena (Thomas, Reference Thomas2006; Thorne, Reference Thorne2008). Immersion in the data began during and following each interview by means of written field notes and journaling. The audio recordings were transcribed verbatim; this allowed for greater engagement with the data and supported the creation of brief interview synopses (Thorne, Reference Thorne2008). To ensure that the idiosyncratic elements of each participant’s narrative were maintained, synopses were continuously referred to throughout the analytic process. All transcriptions were uploaded and managed in NVivo 12.

Next, the primary researcher and co-authors created a preliminary broad-based coding scheme. Rather than focusing on precision within codes, data with similar properties were grouped together and linkages to other groupings were considered (Thorne, Reference Thorne2008). Engaging with the data holistically facilitated an understanding of the larger picture and fostered a more comprehensible analytic framework (Hunt, Reference Hunt2009; Thorne, Reference Thorne2008) – alongside coding, memoing captured ideas on early patterns, lingering questions, and how excerpts related to other participants’ transcripts.

Since data collection and analysis occurred concurrently, preliminary codes were adjusted as interviews and immersion in the data continued (Thorne, Reference Thorne2008). The analysis was also driven by constant comparison, which involved juxtaposing data to search for similarities and differences that existed across and between participants’ perspectives (Thorne, Reference Thorne2008). A journal was used to document analytic thinking throughout the project, served as an audit trail, and supported reflexive practices such as jotting down personal assumptions (Birks, Chapman, & Francis, Reference Birks, Chapman and Francis2008; Guillemin & Gillam, Reference Guillemin and Gillam2004; Lincoln & Guba, Reference Lincoln and Guba1985; Thorne, Reference Thorne2008). Prior to finalizing the analysis, participants were invited to provide feedback on the evolving conceptualizations and themes in the data. Feedback was provided informally through e-mail by two study participants and served to refine the analytic process and enhance rigour (Thorne et al., Reference Thorne, Kirkham and MacDonald-Emes1997). Participants felt that the four main themes accurately captured the essence of working with older homeless adults from the perspective of a health care provider. Recommendations centred around further discussing the role of harm reduction approaches in their work and expanding upon system-level challenges.

Ethics

Ethics clearance for this project was obtained from the University of Waterloo Office of Research Ethics (ORE# 41210). Participant confidentiality was ensured by anonymizing interview quotations.

Findings

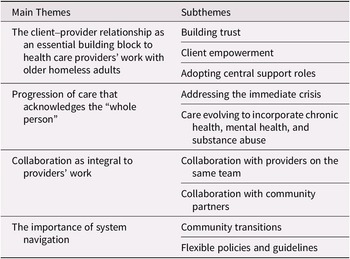

After reviewing and analysing the data, four key themes emerged from the analysis: (a) the client-provider relationship as an essential building block to health care providers’ work with older homeless adults; (b) progression of care that acknowledges the whole person; (c) collaboration as integral to providers’ work; and (d) the importance of system navigation. Table 2 outlines the central themes and associated subthemes. Participants also discussed both challenges and rewards that relate to each theme identified above, which are expanded upon below with supporting quotations.

Table 2. Overview of themes and subthemes

The Client–Provider Relationship as an Essential Building Block to Health Care Providers’ Work with Homeless Older Adults

All participants stressed the importance of relationship-building in their work with homeless older adults. The client–provider relationship was based upon building trust, client empowerment, and providers adopting central support roles.

Subtheme 1: Building trust

Some providers discussed how their initial visits with new older adult clients revolved primarily around establishing trust:

So I think a lot of it just in the beginning is trying to get people to trust you…because they won’t come back if they don’t feel like they can trust you or understand you if you’re not validating their experiences. So, I think that’s a large part of it with older adults, is trying to validate what they’ve been through, letting them be heard. (P01, Nurse Practitioner)

As mentioned in the excerpt above, validating the lived experiences of older clients was a mechanism used by health care providers to build trust. For older adults facing homelessness, lack of trust can act as a deterrent to seeking care. Meanwhile, fostering a trusting and open relationship with a client may allow the provider to maintain ongoing rapport with the older adult and eventually begin addressing other health and social needs. This concept is highlighted by the following participant:

It’s more just always remaining really non-judgmental and just listening to their stories and all the challenges that they’ve had in their life. And, once that openness and that safe space is created, and they can share more things that have happened for them, then I feel like I can kind of start to do the counseling piece. (P07, Registered Social Worker)

While all providers pointed to the role that building trust plays in their day-to-day work with clients, they also recognized that forming trusting client-provider relationships requires significant time. Providers emphasized that gaining trust with older adult clients is especially time demanding because of their accumulated negative health care experiences. For health care workers, engaging in trusting client-provider relationships with older homeless adults revolved around approaching their work through a trauma-informed lens, reflecting the traumatic nature of the experience of homelessness. Providers affirmed that building relationships with any homeless population and delivering care require an understanding of the interconnectedness of trauma, mental health, and addiction. Some providers, such as the following nurse practitioner, expanded on this concept:

But, that’s the other thing with this population is there’s a big trauma component or whether their addiction…circles back to some mental health generally, something traumatic has happened to them. (P04, Nurse Practitioner)

Subtheme 2: Client empowerment

A recurring sentiment expressed amongst providers was promoting a relationship where older clients felt a sense of personal control and responsibility over their own health. Enabling older homeless adults to lead their own health care decisions functioned to instill agency within individuals often lacking control in other areas of their lives and to encourage them to work toward the issues they found most meaningful:

I like to give them control because then a lot of times what we see is they don’t have a lot of control over certain aspects of their life. So, if they can at least make some healthcare decisions, it gives them some responsibility, some accountability. It makes them feel good and that that’s a sense of control that they have, and it also makes my job easier because if they’re saying, yeah, this is really important, they will also be more motivated to work towards it. (P04, Nurse Practitioner)

Phrases such as, I have a tendency to always take my cue from the clients (P01, Nurse Practitioner) and It’s all just geared on what that person finds to be most important to them (P04, Nurse Practitioner) reflect that health care providers in outreach settings prioritize older homeless adults’ goals.

Subtheme 3: Adopting central support roles

A common thread spanning multiple interviews was the isolation and overall lack of support faced by older homeless adults. As a result, health care providers working with this population often assume central support roles for their clients. However, the nature of these supporting roles varies between providers, with some participants describing how they fill in for missing family members:

I know I become this person’s niece or granddaughter or little sister or older sister, depending on who you’re working with. There is a bond that forms, while you maintain your professionalism. I would say that relationship, it has boundaries. But that’s very joyful. Knowing that somewhere this person has a family, but they can’t be together and it’s sacred to be a stand-in for a family member. (P05, Registered Nurse)

Providers also took charge of tasks, which are often the responsibility of family members or caregivers, such as helping clients keep track of appointments, arranging transportation to appointments, and managing medications. Even after an older homeless adult died, providers said they had at times acted in place of family members, such as being documented as next of kin and/or attending memorial services.

Other health care workers offered more indirect social support by linking older clients with providers, such as outreach workers, who could then provide more individualized social support. Health care providers conceded that a key element of supporting older adults was connecting them to the community to regain “that sense of purpose,” thus linking older clients to outreach workers who could better facilitate these connections was seen as vital.

Challenges and rewards

Providers discussed the challenges and rewards associated with building trusting relationships that promoted client choice and taking on central support roles with older homeless adults. The most significant challenge mentioned by health care providers was how emotionally demanding their roles could be, including listening to clients’ painful life stories:

What’s hard is listening to their stories, of course, because it’s years of intergenerational trauma, and complex trauma, and some pretty horrific things that people have endured (P07, Registered Social Worker). Providers developed strategies to look after their own mental health and achieve work-life balance through hobbies, as well as remain connected to their family and friends.

Although coping with the emotionally demanding nature of their work was a prevalent challenge for providers, participants stated that witnessing older homeless adults’ strength and resilience was a rewarding component of their work. They also appreciated hearing about their clients’ journeys:

I loved just sitting down with people and hearing their story, because everybody’s got a story. And some older gentlemen walked around our parking lot, wasn’t always an old guy walking in the parking lot. He was a schoolteacher, he was married… So, I love hearing these stories of how did he get here? How can we get you back to where you want to be? (P09, Shelter Manager of Mental Health & Housing)

Learning about older adults’ life experiences also offered health care providers the opportunity to reflect on their own lives and, in some cases, supported healing for providers with difficult pasts. The following participant spoke about personal healing and witnessing the process in colleagues:

It’s a place of healing our own stuff, I think. A lot of people that work in this environment have come from a struggle, some kind of a struggle, usually as a child. And that’s across the board you find that. But whereas a child you had anger that you had to live that life, as an adult, when you think you can’t do it, it heals all those wounds. It’s fascinating to watch that. (P06, Registered Nurse)

Progression of Care that Acknowledges the “Whole Person”

When supporting older homeless adults in outreach settings, health care providers approached their work holistically. This approach began with addressing the immediate crisis with care and then evolved to incorporate chronic conditions, mental health, and addiction.

Subtheme 1: Addressing the immediate crisis

In their first interactions with older homeless adults, health care providers often needed to focus on immediate needs for health care and basic necessities such as food. When asked how she supports and provides care to older adults, a registered nurse simply asserted, We have to start very basic … with food (P05, Registered Nurse). One participant outlined what providers’ initial encounters with older clients look like:

I would say often individuals first get connected to the primary care clinic for physical health needs. So, sometimes it’s because someone has a bad cough or an infection of some kind, or maybe they have a wound that they want looked at. (P08, Psychiatrist)

It was evident through interviews with providers that their work with older homeless adults requires more than offering “traditional” clinical services. As explained by a health care provider, The medical history almost takes a back burner because you have all these other things that you’re trying to accomplish first (P04, Nurse Practitioner). This provider indicated that in a care setting where people’s basic needs are not being appropriately met, the boundaries of providers’ roles and responsibilities are expanded: So when we look at even like the Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, your number one thing is looking at their housing, their finances, social supports. So, that’s our go to right then and there. As illustrated through this quote, addressing social determinants of health was intertwined with health care providers’ work with older clients in outreach.

In conjunction with providing acute care, assisting older adults in finding stable housing was prioritized due to the intrinsic links between housing and health. They noted that without stable housing, it would be very difficult for clients to attain better health outcomes or make progress in other areas:

I think housing is the biggest thing for people because if you don’t have housing, you don’t have health. And people are in itinerant housing and shelters and homeless and living on the street. I mean their health outcomes are totally different from health outcomes of people who do have housing because you’re not going to sit and talk to somebody about smoking cessation, even if they have COPD, if they’re living on a park bench; it’s just not appropriate. (P02, Physician)

Besides housing, providers assisted older adult clients with obtaining IDs, finances, and income support. A few participants spoke about connecting older homeless adults without proper identification to an identification worker, which was imperative in accessing medication and other medical services in the community.

Subtheme 2: Care evolving to incorporate chronic health, mental health, and substance abuse

After “addressing the immediate crisis” and creating a rapport with an older adult client, health care providers spoke about integrating other aspects of care into their work with the individual. Most health workers mentioned that prioritizing tasks was vital in preventing an older adult from feeling overwhelmed:

Blood work, x-rays, go fill a prescription, referral to a specialist, that becomes very overwhelming but if I can break it into small parts and say, ‘You know what, let’s get your foot fixed up. I’m worried about it. Come back and see me tomorrow so I can see it again and then maybe we can talk about the fact that you’re not sleeping well or the fact that you’re feeling more anxious or that you’re feeling more depressed or you’re worried about your substance use.’ (P01, Nurse Practitioner)

The provider above also indicated that her work with older homeless adults has a tendency to evolve into more chronic disease management, support around mental health and addiction. Health care providers witnessed accelerated aging processes in this population, with chronic conditions emerging in clients’ forties and fifties. Within this context, providers heavily supported older adults in managing chronic physical and mental health conditions. For some older adults facing homelessness, progression of care also included addiction management. While older clients for the most part were not IV drug users as were many of their younger counterparts, providers still supported this group with substance abuse issues, specifically related to alcohol. Harm reduction techniques were underlined as “the only useful way” that providers could assist clients in managing their substance abuse disorders.

Challenges and rewards

Health care workers spoke about challenges and rewards associated with providing holistic care to older homeless adults that encompassed a variety of health and social needs. Providers found it difficult to address older adults’ accumulated health conditions that were usually severe by the time the client sought care after years of their health going unchecked. One provider described this predicament:

And it’s challenging because if you would’ve seen them maybe 15 years ago, you could have maybe helped them with an orthotic or referred to physio or OT, but they just have powered through it and it becomes a chronic problem and you can only do so much at that stage. (P03, Chiropodist)

Maintaining continuity of care for clients and seeing consistent results was challenging due to the barriers older adults experience that impact their ability to follow treatment plans or continue accessing services.

Most health care workers expressed the significance of being able to make even small improvements in older adults’ health and well-being: the small wins. One of the most rewarding small wins was when a client decided to reconnect with a provider and continue seeking care. The health care provider stated:

To me, the most rewarding thing is when people come back, where I’ve never met them before, they meet me in the shelter, they meet me at [name of agency], whatever and they come back to see me the following week or two weeks later. (PO1, Nurse Practitioner)

On many occasions, providers working in outreach were the first point of contact for older homeless adults within the broader system. Health care workers found this aspect of their work rewarding because as the first point of contact, they were able to connect older adults to other health and social supports in the community.

Collaboration as Integral to Providers’ Work

A persistent theme underpinning interviews with providers was the necessity of ongoing collaboration with providers on the same team and with community partners.

Subtheme 1: Collaboration with providers on the same team

Within the collaborative care model described by providers, allied health professionals and outreach workers were well-integrated and played an important role in bridging persisting social and health gaps that interfered with care. For instance, two physicians explained:

I probably wouldn’t be able to do this job if I didn’t have a social worker and patient support worker because it would be just too much to do sort of primary care stuff and identify… sort of ongoing health issues and also support people because it’s getting them to appointments, getting them to get blood work done, getting their medications, all those pieces…If you didn’t have that support, then I think it probably would be pretty useless what you’re doing. (P02, Family Physician)

If the outreach workers weren’t available, the people that we need to help would have no one else to assist them in getting around to get to appointments or helping apply for housing somewhere. (P10, Retired Family Physician)

Working cohesively as a team allowed for more efficient resource coordination and the opportunity to collaborate with colleagues when navigating unfamiliar territory; this also ensured that older clients were being appropriately linked to providers. Health care providers also worked as a team to support one another and communicate any safety concerns:

So if I have any concerns, like I might practice with the door open, I might give a heads up to one of the other colleagues, ‘Hey, this person is really agitated, I’m going to see them, but just know that we might need to deescalate the situation.’ (P03, Chiropodist)

Subtheme 2: Collaboration with community partners

Due to older homeless adults’ distinct health and social service needs, fostering productive community partnerships with agencies, organizations, and consultants formed a particularly critical aspect of providers’ work with this population. One health care provider discussed this aspect of collaboration in their work:

90% of what we do is networking… I think most of what we do is call in somebody who knows. So, I don’t ever profess to know all the answers. I would rather get involved with an agency who does. (P09, Shelter Manager of Mental Health & Housing)

When providers had the opportunity to work with community partners, they felt better equipped to help their clients more smoothly navigate available services and resources.

Challenges and rewards

Participants identified that information sharing was a challenge in collaborating with other providers. Although a few participants commented that access to medical records and information sharing in outreach has improved, there appears to be some enduring gaps. A common electronic medical record (EMR) system in the region facilitates information sharing between health care workers on the same team. However, health care providers were restricted in their ability to easily share information between different teams and organizations supporting homeless individuals in the community. Not having a streamlined approach for sharing information between providers in different community settings often resulted in health care workers dedicating a large portion of their time to following up with other providers and partners outside of their teams. Providers were optimistic about exploring new ways to connect providers and community members with one another to promote better client outcomes but noted that client privacy was a concern:

But the barriers there is we’re dealing with personal health information that you have to be very careful as to who has access to that. And it would be great if we could be more connected electronically. (P02, Family Physician)

Providers reflected on some of the rewarding aspects of working in a collaborative environment, such as being able to learn from different disciplines. As opposed to other health care settings where interprofessional collaboration may not be consistently adopted, providers worked alongside each other when making care decisions and felt a sense of comradery. This sentiment was described by a provider:

So, I think, it’s just having good people around you that you work with that are all trying to do the same thing, have the same goal. Yeah. It’s like just shared experience really.

(P07, Registered Social Worker)

Overall, there was a consensus amongst providers that collaboration is advantageous in reducing their workload and improving outcomes for clients.

Importance of System Navigation

The final theme emerging from conversations with providers was in helping clients navigate through various systems of health care services, community supports, and correctional services in their everyday work. This specifically related to community transitions and differing policies and guidelines.

Subtheme 1: Community transitions

Health care providers discussed supporting their older clients through multiple community transitions, including correctional facilities/hospitals into the community and community/hospitals into long-term care (LTC). Providers spoke about the complexity of these transitions; for instance, a nurse practitioner (P01) described transitions for clients from correctional facilities or hospitals into the community. She stated that while they may stabilize in the correctional facility or hospital, without adequate discharge planning and community supports in place, providers are starting all over from scratch. However, discharge meetings between community providers and institutions only happened under really fortunate circumstances. Insufficient discharge planning can entrap older homeless adults with chronic conditions and limited social support networks in an ongoing cycle:

So, the other gentleman…very mentally unwell that we are trying to house. He’s going through the cycle of going in the hospital, getting medicated, being well, coming out, landing in shelter, getting unwell, going back to hospital. (P09, Shelter Manager of Mental Health & Housing)

Health care workers were also involved in coordinating transitions from the community into LTC. A registered nurse (P06) explained that a major barrier to entering LTC was a history of substance abuse. However, even when an older adult was admitted to a LTC home, adjusting to a new environment was difficult, especially for older adults who had experienced chronic homelessness:

And if you’ve been homeless most of your life, how do you use a bed, and use a room, and go to the dining room, and eat at a table with three other people when you’ve been alone most of your life? So, some people fall into that, and some people struggle into that…So, they want to sleep outside, outside the front door… (P06, Registered Nurse)

During these transitions, providers advocated on behalf of their clients and combatted stigma, often educating staff working in institutions about the experiences and needs of homeless individuals.

Subtheme 2: Flexible policies and guidelines

When describing their work in outreach settings, providers commented on the flexibility surrounding policies and guidelines. Due to the flexibility within their roles, providers attempted to be as accommodating as possible with their clients. Weekly drop-in clinics that do not require appointments or health care cards to access services were offered in community spaces:

Just because nobody makes appointments- tends to be the last thing on somebody’s mind is getting to appointments. So, if they know I’m always there Tuesdays from 10 to 1, there’s a good chance that they’re going to keep coming back because they’re already there anyways for meals. (P03, Chiropodist)

Challenges and rewards

Providers stressed that navigating the system could be very frustrating and time-consuming, with so many hoops to jump through to get things for individuals (P01, Nurse Practitioner). A few providers spoke about having to complete large amounts of paperwork for clients, especially for financial support. Inadequate resources, ranging from limited housing options and treatment facilities to a need for more outreach workers, was another challenge. Altogether, providers’ ability to assist clients was largely limited by system constraints, as indicated by one participant:

The difficult part was accessing resources, that used to get us not only frustrated but angry and there are lots of barriers…the fact that many of the things we wanted to do for them couldn’t be done because there’s no funds to pull it off. (P10, Family Physician)

Navigating a system with different policies and guidelines also offered some rewarding aspects. Providers’ work environments in outreach were more unstructured than other care settings, which was advantageous for both clients and health workers. One health care provider explained, So I know that I can move my schedule myself to accommodate the needs that I’m finding on the street (P05, Registered Nurse). Working in unstructured settings allowed health care providers to tailor their schedules according to their clients’ needs, and providers generally liked this flexibility.

Discussion

Findings from this study offer insight into health care providers’ perspectives based on working with older homeless adults in outreach settings. Providers’ perspectives reflect the multifaceted nature of their roles working with older homeless adults in outreach settings. Providers gave extensive social support to their clients through relationship building, which involved establishing trust and client empowerment. Previous studies have broadly looked at trust building between homeless individuals and providers, emphasizing that establishing trust is a timely process but crucial when working with homeless populations (Bharel, Reference Bharel2015; Biederman & Nichols, Reference Biederman and Nichols2014; Salem, Kwon, & Ames, Reference Salem, Kwon and Ames2018). In this study, participants shared a similar perspective; they further revealed that developing trusting relationships between older clients and health care providers is imperative due to this population’s prior histories and adverse experiences. Focusing on trust building may become especially difficult for health care providers as their workloads increase with elevated rates of chronic homelessness further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, along with ongoing resource constraints. Guiding regulations and policies for health care providers working with older adults experiencing homelessness should reflect the importance and time-demanding nature of establishing trust with this population.

Providers stressed the importance of giving older adults control over their own care and involving them in decision-making processes, which is a tenet of person-centred care (The King’s Fund, 2012), and is supported by clinical recommendations and past studies on homelessness (Bonin et al., Reference Bonin, Brehove, Carlson, Downing, Hoeft and Kalinowski2010; Gaboardi et al., Reference Gaboardi, Lenzi, Disperati, Santinello, Vieno and Tinland2019). Participants expanded upon these concepts specifically related to older adults. Empowering clients to be in control of their care, especially individuals with many years of accumulated negative health care experiences and trauma, motivated them to work toward addressing more serious health issues. These aspects of the client-provider dynamic align with the guiding principles of therapeutic alliance (Bonin et al., Reference Bonin, Brehove, Carlson, Downing, Hoeft and Kalinowski2010; Salem et al., Reference Salem, Kwon and Ames2018; Tsai, Lapidos, Rosenheck, & Harpaz-Rotem, Reference Tsai, Lapidos, Rosenheck and Harpaz-Rotem2013). Providers engaging in therapeutic relationships with older adults also incorporated a trauma-informed approach to care. The premise of trauma-informed care is an assumption that “homelessness is a traumatic experience, which for many homeless people is compounded by serious medical and behavioral health problems and/or histories of abuse and neglect from which they still suffer” (Bonin et al., Reference Bonin, Brehove, Carlson, Downing, Hoeft and Kalinowski2010, p. 24). Trauma-informed care is vital within homeless populations, as they endure high levels of traumatic stress. Health care providers asserted that older homeless adults may be especially susceptible to traumatic stress, resulting from threats to their safety, complex health issues, and years of accumulated trauma (Hopper, Bassuk, & Olivet, Reference Hopper, Bassuk and Olivet2010).

Health care providers spoke about assuming central support roles for their older clients and, in some cases, even assumed family figure roles. With older homeless adults’ social networks often comprising predominantly providers and individuals from agencies, health care workers may be uniquely positioned to offer valuable assistance surrounding advance care planning and end-of-life decision making, such as through relevant discussions and documentation (Ko, Kwak, & Nelson-Becker, Reference Ko, Kwak and Nelson-Becker2015; Sudore et al., Reference Sudore, Cuervo, Tieu, Guzman, Kaplan and Kushel2018). Providers also offered health support through a harm reduction lens (Canadian Mental Health Association, 2023.; Thomas, Reference Thomas2005) that incorporated the full spectrum of physical, mental, and social determinants of health. Addressing the older clients’ most basic necessities was usually prioritized, followed by managing chronic diseases, mental health conditions, and substance abuse disorders.

While providers spoke about the prevalent physical and mental health conditions in older clients that align with findings from other studies (Garibaldi et al., Reference Garibaldi, Conde-Martel and O’Toole2005; Gonyea et al., Reference Gonyea, Mills-Dick and Bachman2010; McDonald et al., Reference McDonald, Dergal and Cleghorn2004), they emphasized that without stable and affordable housing options for older homeless adults, it is challenging for clients to achieve improved health outcomes. Consistent with the literature (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Thomas, Cutler and Hinderlie2013; McGhie, Barken, & Grenier, Reference McGhie, Barken and Grenier2013), health care providers raised the need for more housing options that specifically target the diverse needs of homeless older adults (i.e., subsidized housing that offers support services for older adults’ health and social needs).

Another significant aspect of health care providers’ roles in outreach settings was collaboration. The benefits of interprofessional collaboration described by participants, such as improved client outcomes and efficient use of resources, are echoed within other health care settings (Bridges, Davidson, Soule Odegard, Maki, & Tomkowiak, Reference Bridges, Davidson, Soule Odegard, Maki and Tomkowiak2011; Sargeant, Loney, & Murphy, Reference Sargeant, Loney and Murphy2008). Due to the complexity of health and social circumstances faced by homeless individuals, especially older clientele, interprofessional collaboration that effectively engages different disciplines is necessary (Moskowitz et al., Reference Moskowitz, Glasco, Johnson and Wang2006). However, it was clear that information sharing between different teams and organizations was a prominent gap. These findings solidify the need for resources and/or tools that facilitate timely, safe, and confidential ways of sharing client information between different institutions and organizations, thus improving continuity of care for older homeless adults.

Health care providers were system navigators that supported and advocated for older clients’ needs during difficult community transitions. Insights from providers revealed the absence of standardized discharge protocols for homeless individuals leaving care settings, such as hospitals. This aligns with Canham et al.’s (Reference Canham, Davidson, Custodio, Mauboules, Good and Wister2019) study, which suggests the need for coordination between service systems, including hospitals and shelter/housing, to enhance transitions for homeless clients from hospital. In another study, Canham, Custodio, Mauboules, Good, and Bosma (Reference Canham, Custodio, Mauboules, Good and Bosma2020) also described the lack of appropriate housing options for older adults upon hospital discharge and the inadequate community support to assist older adults with complex and chronic conditions.

Health care providers also reflected on older homeless adults’ transitions into LTC homes, a theme that remains relatively unexplored. One qualitative study pointed to the need for more housing options for older homeless individuals with minor functional limitations to prevent premature relocation to LTC (Sussman et al., Reference Sussman, Barken and Grenier2020). The current study also corroborated other findings from Sussman et al.’s (Reference Sussman, Barken and Grenier2020) study, such as the need for harm reduction models in LTC homes and heightened flexibility around rules and regulations in LTC. Health care providers pointed out the alienation that some older homeless adults may feel when entering LTC, as they are usually significantly younger than other residents and may have vastly different life experiences. Additional research on how to foster a sense of community and belonging for older homeless adults in LTC is necessary. Building on Sussman et al.’s (Reference Sussman, Barken and Grenier2020) recommendations, addressing the LTC sector’s limited awareness of issues pertaining to homelessness and underlying prejudices through person-centred approaches should also be prioritized. This could involve staff sessions where a new resident’s story will be shared and strategies are provided on how to support quality of life for a person who has experienced homelessness.

Health care workers were most frustrated by system-level challenges (i.e., limited funding, coordinating care with different sectors, inadequate resources and supports tailored to an older homeless population, the cyclical nature of homelessness, and stigmatization) that imposed multiple barriers to delivering optimal care to their clients. A key takeaway from providers was that without beginning to address these deeply engrained system-level issues, it will be difficult to make huge strides in improving health outcomes for older homeless adults.

Health care providers described rewarding aspects of their roles that led to personal and professional fulfilment. Among the rewarding aspects of their work was bearing witness to the strength and resilience demonstrated by their clients. In a care setting where system constraints and structural inequities that reinforce homelessness can be demoralizing, health care providers focused on the seemingly small victories, like a client returning for a follow-up visit. Their roles also afforded them flexibility and significant collaboration with other providers, which providers appreciated and allowed them to better adapt their care for their clients’ specific needs.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this qualitative study include its emphasis on generating knowledge that is relevant and applicable to providers. This study’s findings addressed an identified need in the current literature for additional information on a broad range of health system perspectives of providers supporting older homeless adults and established a knowledge base for future studies in this area.

This study also has limitations. A small sample of diverse providers working in outreach settings situated within one mid-sized urban metropolitan area was recruited for this study, thus limiting the transferability of study findings to other jurisdictions. On the other hand, Thorne et al. (Reference Thorne2008) have argued for the usefulness of studies with smaller sample sizes, which can still produce important knowledge and identify areas that require further investigation. According to Morse (Reference Morse2015), qualitative samples must be adequate and appropriate to demonstrate rigour. Through this study, health care providers had substantial expertise working in their respective health fields and particularly in outreach. Participants’ cumulative experiences allowed for a rich understanding of their roles working in outreach settings with older homeless adults, as well as related challenges and rewards.

Conclusion

An in-depth exploration of health care providers’ perspectives supporting older homeless adults in outreach settings revealed that their roles were multidimensional and extended beyond delivering clinical services. Providers offered social and health support and acted as collaborators and system navigators. Within their roles, health care workers expressed the most frustration surrounding system-level challenges that limited their ability to make drastic and sustainable changes in their clients’ outcomes, such as inadequate services for an older population. Despite these difficulties, providers found their work personally and professionally rewarding. While this study contributes valuable insights to an underexplored area, namely health care providers’ perspectives gained from working with older homeless adults, further research is needed that integrates both provider and client perspectives.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the participants involved in this research.

Funding

This research was supported by an Ontario Graduate Scholarship and by a Canadian Frailty Network (CFN) Interdisciplinary Fellowship. CFN is supported by the Government of Canada through the Networks of Centres of Excellence (NCE) program.