Land-grant colleges and universities have long been lauded for democratizing higher education. The Morrill Land-Grant College Act of 1862, also called the Morrill Act (and the successor Morrill Act of 1890), made public land available to states to sell, with the profits going toward establishing and supporting public colleges and universities. The Morrill Act specifically set out to provide education in the areas of agriculture and applied science and therefore was seen as a move away from “elite” liberal arts education. Because of this, in the nineteenth century, the land-grant institutions were commonly referred to as “democracy's colleges.”Footnote 1

The 150th anniversary of the land grants occurred in 2012, and while the celebration was laudatory, historians also took the opportunity to rethink the narrative about the Land-Grant Acts and the meaning, purposes, and impacts of the colleges and universities. Revisions to the historical narrative have focused on the extent to which “the people” actually wanted access to higher education; the extent to which applied sciences and technology really replaced the liberal arts in these institutions; and the extent to which land-grant colleges democratized education, given that they did not fully include women, and the Morrill Act of 1890 also provided a structure that supported continued segregation of African Americans in the South.Footnote 2

These are important revisions to the story, but they do not directly address the question of the land itself. Land-grant institutions depended on the federal government selling land. What land was sold? How did the US government have claim to that land? To what extent are land-grant colleges founded on dispossessing American Indians from their land? This article sets out to answer these questions. Scholar Sharon Stein laid some of the conceptual groundwork for understanding the links between the existence of land-grant colleges and the processes of colonization and of accumulation of land and capital.Footnote 3 This article builds on that work by finding out which parcels of land were sold under the Morrill Act, tracing those parcels back to the tribes that earlier were dispossessed from the land, and then connecting the sales to the specific land-grant institutions that benefited.

In recent years, some colleges and universities have begun to address their complicity in the institution of slavery. An important historical assessment of this complicity is Craig Steven Wilder's Ebony and Ivy: Race, Slavery, and the Troubled History of America's Universities.Footnote 4 Wilder argues that we all know that the colleges of the colonial and early national periods benefited from slavery, but that reality is mostly talked about in general terms: yes, there was racism, but that was an aside from the grand purposes of those colleges. Wilder contends that racism was not an aside; the colonial colleges were funded directly and indirectly by the slave trade, sometimes literally built by slave labor, and kept afloat by trustees, donors, and administrators who actively engaged in the slave trade. In the aftermath of Wilder's (and others’) research, eastern colleges have begun to acknowledge their histories. Some institutions, as in the case of Georgetown University, are making reparations to the descendants of enslaved people who were sold to support the institution. Other institutions, for instance, Yale University, have changed the names of buildings so as not to honor slavery apologists.Footnote 5

Similarly, in the history of land-grant colleges and universities, Indian dispossession is often talked about as an aside, if it is talked about at all: yes, dispossession happened, but the importance of land-grant institutions is their promotion of higher education and the rise of applied science. But dispossession was fundamental to the existence of these institutions. The Morrill Act was part and parcel of the federal government's quest to settle the continent with (mostly) white people. With that as a goal, establishing colleges and universities was the aside, not the Indian dispossession.Footnote 6 Certainly, proponents of the Morrill Act had other goals in addition to conquering the West, such as using education as a means to catapult the nation into global prominence as an industrial leader.Footnote 7

This article begins with a brief historiography of the land-grant colleges and then provides a theoretical framework—that of settler colonialism—as a way of understanding these institutions. Next is an explanation of the history of public land law, essential for understanding how the Land-Grant Act worked. Finally, the article addresses two strong links between land-grant colleges and Indian dispossession. The first is that some of those colleges were built on land that had been occupied by American Indians prior to the act; these land-grant colleges were founded on appropriated land, and the history of that land is relatively easy to trace. The second link is that all of the land-grant colleges, even those that existed before the act, were funded with proceeds from the sale of formerly Native land. This funding came to designated land-grant colleges no matter where they existed, and without any relationship to the land sold. That is, the land-grant college in the state of New York might receive the proceeds of public land sold in Montana. These land-grant colleges were funded by the sale of appropriated land. This process is more difficult to trace.

As important as land-grant colleges were and continue to be, they must also be seen as part of the process of settler colonialism. The land-grant colleges were both founded on appropriated land and funded by the sale of appropriated land and, therefore, encouraged westward migration and settlement. The college boosters emphasized agricultural and scientific education that would help foster capitalism, industrialization, and nation-state building. The land-grant policy and the growth of the colleges also further erased Native American rights and history. In all these ways, the land-grant colleges can be seen as a central element of settler colonialism. Congress passed the Morrill Land-Grant College Act the same year as the Homestead Act and acts granting huge swaths of land to railroad companies, revealing that the sale of public land to support higher education was almost an aside to the more pronounced purpose of settling the West. Further, although Congress passed these acts with the intention of encouraging family farms and (mostly white Protestant) settlements, more land was bought by speculators and large-scale agribusinesses than by individual farmers. Praise of the federal government's forward-thinking and largesse in funding more higher education, then, is incomplete. The Morrill Act may have succeeded in democratizing higher education in some ways, but it did so at the expense of Native Americans and to the benefit of land speculators and agribusiness.

Currently, over one hundred land-grant colleges and universities exist, along with an additional fifty agricultural research centers that were created by the Hatch Act in 1887. These institutions were funded in part by the sale of upwards of ten million acres of land throughout the West. Most of these millions of acres were sold in parcels of 160 acres and sometimes in parcels of forty or eighty acres. This makes the task of tracing the sale of these parcels quite formidable. Therefore, the scope here is limited in two ways. For the investigation of land that current institutions inhabit, this article looks only at institutions west of the Mississippi that were founded after the Land-Grant Act and before the Hatch Act, or between 1863 and 1887. For the investigation of land sold to benefit institutions anywhere, this article examines two states immediately west of the Mississippi: Arkansas and Missouri. This article uses the terms American Indian, Indian, Native American, and Native interchangeably, as is the norm for many contemporary U.S. scholars.Footnote 8

Historiography of Land-Grant Colleges

Historians generally speak of land-grant colleges with praise. As historian Roger L. Williams writes, the motives of the founders of the land-grant movement “involve the democratization of higher education; the development of an educational system deliberately planned to meet utilitarian ends, through research and public service as well as instruction; and a desire to emphasize the emerging applied sciences, particularly agricultural science and engineering.”Footnote 9 The first histories of the land-grant colleges have titles that broadcast the authors’ support: The Magnificent Charter: The Origin and Role of the Morrill Land-Grant Colleges and Universities; The State Universities and Democracy; Colleges for Our Land and Time: The Land-Grant Idea in American Education; and Democracy's College: The Land-Grant Movement in the Formative Stage.Footnote 10 Early histories put the land-grant college in the context of antebellum colleges and argue that antebellum colleges were elitist and prepared students for law and business but not much else. In this view, the land-grant colleges, with their emphasis on applied sciences, agriculture, and engineering, were truly democratic. Williams broadens the context for the land-grant movement by looking at the cultural factors of “an expanding democracy; a utilitarian impulse …; the ascending influence of science …; an emboldened agrarianism …; [and] an emerging industrial economy.”Footnote 11

More recent work challenges many of the conclusions drawn in these early accounts, including the simplistic notion that land-grant colleges supplanted classical and liberal arts colleges with an emphasis on agriculture and applied science. The Morrill Act did not produce a single type of institution, nor did it intend to do away with the liberal arts. Land-grant colleges took a variety of forms, and the act specified support for classical education as well as science, agriculture, and engineering. The idea of agricultural colleges was not new when Morrill proposed his bill, and state support for scientific work had existed for decades.Footnote 12 As much as the land grants have been touted as opening up education for those outside of the elite, some evidence suggests that most students actually came from families with “considerable financial means and social standing.”Footnote 13

Even with these revisions, land-grant institutions are commonly depicted as an important piece of the increasing democratization of higher education. As historians Roger Geiger and Nathan Sorber write, “The higher education community looks with nostalgia” on the formation of the land-grant colleges, and still “harken to the Morrill Act's egalitarian past.”Footnote 14 South Dakota State University proudly notes its “land-grant heritage,” proclaiming that the Morrill Act “embodied a revolutionary idea in higher education.”Footnote 15 Iowa State University's website declares that the act “introduced a radical idea—that higher education should be practical and available to the masses, not just the wealthy [emphasis in original].”Footnote 16 The University of California celebrated the “revolutionary” idea of “educating citizens from all walks of life,” made possible by “donating land left over from the building of the Transcontinental Railroad to fund the creation of institutions of higher learning.”Footnote 17 Despite revisions to the historiography, many institutions continue to repeat earlier narratives about their origins.

What few accounts of land-grant colleges do is place the colleges in the context of federal policy to remove the native inhabitants of the land. Most accounts take for granted that land was available and praise the generosity of the federal government for making the profit from the sale of some of that land available to fund higher education. In this way, these accounts fit neatly into an ideology of settler colonialism. Political theorist Adam Dahl writes that “dominant narratives of American democracy … emphasize the formative role of colonial settlement while neglecting colonial dispossession.”Footnote 18 This is also true of the land-grant colleges, where the predominant narratives concentrate on the expansion of education and neglect the Indian dispossession that made the colleges possible.

Theoretical Framework of Settler Colonialism

As a major world power, Britain colonized in numerous ways. In some places, such as India, it engaged in exploitative colonialism, sometimes referred to as classic colonialism.Footnote 19 That is, Britain exploited India for its natural resources and labor. In North America, Britain engaged in settler colonialism, in which British people moved to North America with the intention of staying permanently, bringing with them British social, cultural, and political systems. Settler colonialism results in societies where the settlers’ “descendants have remained politically dominant over indigenous peoples.” To achieve this state, settler colonies necessitated “elaborate political and economic infrastructures.”Footnote 20

Settler colonialism needs settlements, and settlements need land. As historian Patrick Wolfe points out, “Territoriality is settler colonialism's specific, irreducible element.”Footnote 21 The object in settler colonialism is “to acquire land and gain control of resources.”Footnote 22 Early on, British colonists saw land as a way to assure social stability: with the land divided into small estates, no feudal system could gain hold; every free white male could own some land and be self-sufficient; and no landless class would end up in poverty and foment rebellion. This system depended on the accessibility of vast quantities of land, land that the British settlers felt they had a right to under the principle of international law known as the Doctrine of Discovery. This fifteenth-century papal decree asserted that any land not inhabited by Christians “was available to be ‘discovered,’” and claimed by Christians.Footnote 23 Both the Spanish and the British used this doctrine to justify their actions in the New World.

Of course, the land was inhabited, and conflicts repeatedly broke out. By 1763, tired of funding one war after another, Britain decreed that all land west of the Appalachians was off-limits to settlers. This was to be tribal, not white settler, land. Since Britain had an interest in keeping trade routes open, however, it maintained a series of heavily armed forts, which it demanded colonists pay for with the infamous stamp tax. This, then, was the root of the American Revolution: liberty, yes, but liberty for the colonists to self-govern in a way that allowed them the freedom to continue pushing west and to continue the regime of dispossessing and eradicating Native Americans. As historian Bethel Saler puts it, this settler society possessed “an ambivalent double history as both colonized and colonizer…. Political independence, then, liberated settler nations to claim their domestic colonies for themselves alone.”Footnote 24 The federal government moved the line west from the Appalachians with the Indian Trade and Intercourse Act of 1834, which designated most land west of the Mississippi River as “Indian country” (other than what had already been formed into US states or territories, such as Louisiana and Arkansas).Footnote 25 This border, too, would quickly be pushed farther west and its inhabitants either forcibly removed or obliterated. At the same time, the US Supreme Court, basing its decision on the Doctrine of Discovery, established that American Indians had no right to legal title of the land they occupied.Footnote 26

Both the settlers and the federal government followed a “logic of elimination” to guarantee removal of the Native populations. As historian Margaret D. Jacobs writes, this pervasive “logic” created a “set of commonplace notions” that many settler colonialists simply accepted.Footnote 27 Eradication of Native peoples could be through armed conflict, warfare, and murder.Footnote 28 It could also entail other processes of erasure. As early as the 1780s, George Washington wrote that using “force of arms” to drive American Indians “out of their Country” was less effective than “the gradual extension of our Settlements,” which would cause “the Savage as the Wolf to retire.”Footnote 29 Similarly, according to historian William E. Unrau, Lewis Cass, then superintendent of the Michigan Territory (and later secretary of war), wrote in 1818 that “before Indians would feel obliged to move they would have to be almost completely surrounded by white settlements.”Footnote 30 The very process of white settlement—and its concomitant establishment of white Protestant civilization—would lead to the demise of American Indian culture, if not of the American Indian people themselves.

Settler colonialism is tied to agriculture. Wolfe notes that agriculture is geographically fixed (not moving from place to place) and permanent, it propels colonialism's reproduction, it generates capital to keep colonialism going, and it feeds a lot of nonagricultural people.Footnote 31 Early American identity was connected to farming; John Hector St. John de Crèvecœur's 1782 Letters from an American Farmer calls Americans “a race of cultivators” and asks, “What should we American farmers be without the distinct possession of that soil?”Footnote 32 Wolfe argues that not only does agriculture provide materially and economically, it also is a “potent symbol of settler-colonial identity.”Footnote 33 Wolfe notes, “In settler colonial terms, this enables a population to be expanded by continuing immigration at the expense of native lands and livelihoods.”Footnote 34

Settler colonialism needs more than agriculture. It also requires labor, transportation, a banking system, and political stability. Land-grant colleges had the potential to help with all of these things. As Sorber argues, the Morrill Act was in keeping with the Whig platform of support for internal improvements. In this case, “these improvements were tailored for scientific, technological, industrial, and human capital development. To these ends, federal support of higher education could advance economic activity through promoting agricultural science, disseminating useful knowledge, producing skilled free laborers, and elevating the competitiveness of America's farms and factories.”Footnote 35 Even when land-grant colleges taught more than agriculture, then, these institutions can be seen as being in service to the larger project of settler colonialism. Students trained in these colleges and universities helped build infrastructure, launch large-scale bureaucracies, and support the growth of the nation-state.Footnote 36

Not only does settler colonialism describe a process of wresting land away from those who inhabited it, it also casts a cloak of invisibility over that process. As Dahl describes, in addition to the often violent process of dispossession, the settlers also engaged in an active disavowal of the presence of Indigenous peoples. It is, writes Dahl, “an active refusal to historically and ethically grapple with the presence and political claims of indigenous peoples as well as the colonial violence that paved the way for the emergence of modern American democracy.”Footnote 37 More than mere amnesia or forgetting, “disavowal implies the active and interpretive production of indigenous absence.”Footnote 38

Although conquest was a critical aspect of westward expansion, the ideology of settler colonialism required obscuring the reality that the land was already inhabited. One means of doing that was by discursively establishing the land as empty or unused. For example, in 1834 Secretary of War Cass repeatedly referred to sections of land in the newly designated “Indian Country” as “vacant,” even though the land was inhabited by multiple tribes.Footnote 39 Another means was through narratives of “the vanishing Indian,” in which Native populations are depicted as disappearing or in decay and therefore not in need of the land.Footnote 40 Jacobs writes that “with a wistful sigh, popular accounts of westward expansion mourn the passing of the Indians as a (perhaps) tragic but unavoidable result of progress.”Footnote 41 Historian Jean M. O'Brien analyzed the ways that nineteenth-century New England authors utilized a “discourse of disappearance” of the Native population that situated the non-Native settlers as “‘first’ to bring ‘civilization’ and authentic history to the region.”Footnote 42 O'Brien also notes that the repeated language about American Indian “extinction” became linked to land rights.Footnote 43

Dahl argues that manifest destiny has not been analyzed as a distinct aspect of settler colonization.Footnote 44 Likewise, the Morrill Act also has not been thoroughly analyzed as an instrument of settler colonialism.Footnote 45 Some scholars have pointed out the link between the public school system and Indian dispossession. When the federal government in the 1780s set aside plots of land for common schools, it created a system in which white settler children received education because of the government wresting land from Native control. As historian Nancy Beadie et al. phrase it, the “very same benefit and entitlement that ensured white settlers access to publicly supported education … also dispossessed Indians of land and divested them of benefits and power.”Footnote 46 This line of analysis needs to be applied to the land-grant system of funding higher education as well.

The lens of settler colonialism is a way to think about the reason for any federal land policy, including the Morrill Act, which reflects the ideology of settler colonialism in several ways. The sale of cheap land stimulated western migration and settlement. The act promoted education, which is a means of reproducing dominant values, and it specifically encouraged practical and agricultural education. The purpose of the land-grant colleges, as set out by Justin Morrill anyway, was to teach farmers to be better farmers, to farm scientifically. Beyond producing better farmers, the land-grant colleges were part of a bigger project of establishing international strength. According to Sorber, promoters saw higher education “as a means to expand the economic and political influence of the United States.”Footnote 47 While it is also true that the growth of public colleges and universities in the West made higher education accessible to people who otherwise might not have been able to obtain an education, that is not its only legacy. The Morrill Act can be seen as one state-sponsored mechanism of both literally and symbolically establishing settler colonialism.

Public Land Law and the Morrill Act

After the original thirteen colonies were established as states and the new country began moving west, members of Congress recognized a need to establish policy regarding control of land. In 1780, Thomas Paine published a pamphlet entitled Public Good: Being An Examination into the Claims of Virginia to the Vacant Western Territory. The title of the pamphlet alone highlights several issues. First, “public good” refers to Paine's (and others’) argument that so-called “vacant” land should be a “national fund for the benefit of all.”Footnote 48 This position guided some of the federal government's policy, which sought to make land available according to republican principles in order to prevent a new form of feudalism, or putting too much property, and therefore wealth, into the hands of a church.Footnote 49 The Morrill Act, when it passed sixty years later, reflected this argument that public land should benefit all and not just a few. Second, Paine's pamphlet referred to western land as “vacant”—an example of the way that settler colonialism rendered Indigenous people invisible.

The federal government first sent surveyors out to divide territories into a grid pattern, using a township and range system. This meant marking out an east-west baseline and a north-south meridian line and then dividing that section into townships six miles square; those townships were again divided into thirty-six numbered sections of one square mile each (640 acres). Later, those sections were again subdivided into half sections of 320 acres, quarter sections of 160 acres, half of a quarter or eighty acres, and half of that again, or forty acres. Once the grid was marked out and the townships and sections numbered, a federal land office could open and the land would be available for sale, first in a public auction; whatever was left was sold at the land office.Footnote 50 As methodical as this sounds, the reality was messy and the laws related to land were prolific. Between 1789 and 1834 alone, Congress passed 375 different land laws regarding everything from the minimum purchase price at auction (a price that fluctuated over the years) and whether land could be bought on credit, to grants of land to fund common schools, railroads, canals, roads, and for draining swamplands.Footnote 51

When land was sold at auction or through the land-grant office, who got the proceeds? Where did the money go? This was hotly contentious for decades. People in the established states argued that profit from national expansion should benefit the whole nation; people living in the eastern states should get a share of the sale of new lands. People in the newly formed states argued that states were like sovereign nations and should have all the benefit of the land sales themselves. Initially, the debate was fairly moot, as Congress decided that land-sale profits should all go toward paying off the large national debt left by the Revolutionary War. Once the debt was paid, though, Congress discussed many approaches for apportioning the profits in ways that felt fair to both easterners and westerners.Footnote 52

Many individuals and special interest groups proposed ideas for using public land in the West. One such group was the United States Agricultural Society, a group of scientists and other promoters of scientific farming. They proposed a plan, put forward by Morrill, a congressional representative (and later senator) from Vermont, in which the federal government would grant 20,000 acres for each congressional senator and representative of the new states. For established states, the plan also included scrip (a certificate entitling the holder to acquire a specified amount of public land) on the same basis for the purpose of creating new or supporting existing institutions for agricultural and mechanical arts. The newer states, in which these public lands existed, could build new institutions on the donated land, could sell the land and use the proceeds to build an institution on another site, or build on some land and sell the rest to support the institution. Older states could not use their scrip to acquire land; they had to sell the scrip and use the proceeds to support their existing institutions or build new institutions in the state.Footnote 53

This plan of supporting practical higher education through grants of western land was first proposed in 1851 and finally passed Congress in 1862 as the Morrill Land-Grant College Act. That same year, Congress also passed the Homestead Act and railroad land grants. Neither the Homestead Act nor the Morrill Act passed until the South seceded, as Southerners opposed both acts. The Homestead Act, in particular, was anathema to southerners, as it gave land in increments of 160 acres—a perfect size for the old Jeffersonian ideal of a yeoman farmer, but not a good size for large-scale plantations run on the labor of enslaved people.Footnote 54 Southerners, therefore, opposed all of these land policies, which northerners quickly put into place after secession. Northerners, with much higher population density, wanted to encourage people, including the millions of new immigrants, to leave the overrun, overburdened, poverty- and crime-ridden cities and head west as landowning farmers.Footnote 55

Not only did Congress want to reduce overpopulation in the East, it also wanted to establish white dominance in the West. Congress worked toward this goal by passing legislation that promoted westward migration. The Homestead Act encouraged people to move west by literally giving the land away: settlers only had to pay a small filing fee and live on and work the land for five years. If they didn't want to wait five years to gain title to the land, settlers could opt to farm the land for six months and then pay for the land outright at a low price.

Congress also gave huge tracts of land to the railroads, as the rapid improvement in transportation fostered new settlements. Historian Frederick Jackson Turner wrote that “the railways began their work as colonists” and created a “new form of colonization” that depended on banks for capital.Footnote 56 The Morrill Act must be seen in this context. Although it did earmark funds for public higher education, its real purpose was to encourage white settlement of the West. Indeed, when the act passed, the press wrote about it “more as a federal land policy than as an educational innovation.”Footnote 57 As historian Richard White explains, the Homestead Act, Morrill Act, and railroad grants served a “common vision of a prosperous, progressive, economically expansive, and harmonious West.”Footnote 58 That “harmonious West” was a white-dominated West, and the “common vision” depended on eradicating Native Americans from their homelands.

In its final form, the Morrill Act increased the amount of land per congressional representative to 30,000 acres from the 20,000 originally proposed. Because eastern states were more populous and therefore had more representatives in Congress, they received scrip for large amounts of land. New York received scrip for nearly a million acres (990,000) and Pennsylvania received scrip for 780,000 acres, while the newer states received roughly 90,000 acres each. Altogether, 7,830,000 acres in scrip was distributed to benefit land-grant institutions in the older states, in addition to 3,520,000 acres designated within the new states for the benefit of those states’ agricultural colleges.Footnote 59 This sounds like a lot—and it is—but to put this in perspective, Congress set aside 127,000,000 acres for railroads, and nearly 84,000,000 for the Homestead Act.Footnote 60 For further perspective, the Louisiana Purchase added 523,446,000 acres to the United States; the acquisition of Florida added over 43,000,000 acres; Texas 246,776,000 acres; Oregon territory (including Washington, Idaho, and part of Montana) over 180,000,000 acres; and the Mexican land from the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, including California, Arizona, and New Mexico, and parts of Colorado and Wyoming, over 334,000,000 acres.Footnote 61 So while land grants for higher education were a significant amount of land, they also represented a small part of the whole.

When the act passed, few states east of the Mississippi had any public land left (except for Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin). These states, because they could not purchase land outright in the West, used the sale of their scrip to fund the land-grant colleges in the eastern states. After scrip was issued to a state, the governor usually appointed a commissioner to administer the sale. Buyers bid on the scrip. Those buyers could be individuals looking to move West, or land companies or individuals who bought large tracts of land to resell.

Most states sold their shares to brokers, who sometimes acquired huge quantities. For instance, land broker Gleason F. Lewis bought all of Kentucky's scrip and more than half of Pennsylvania's.Footnote 62 Ohio received scrip for 630,000 acres, a majority of which (576,000 acres) was bought by just three people.Footnote 63 Some states sold their land quickly and cheaply—Pennsylvania averaging less than sixty cents per acre, and Brown University in Rhode Island averaging less than forty cents. Cornell University (New York) sold some of its scrip for eighty-five cents per acre for immediate use, and let Ezra Cornell buy the bulk of it. He held on to it for decades until the price increased enormously and then gave the proceeds to the university. Ultimately, Cornell received, on average, more than five dollars per acre, netting nearly $6 million in 1905.Footnote 64

Congress's decision to apportion western lands to support agricultural colleges in the East (along with agricultural colleges in the West) is one reason that tracing Indian dispossession is difficult. There is no obvious connection between, for instance, the University of Delaware and the removal of the Quapaw in Arkansas twelve hundred miles away. And yet that university did in fact benefit from a treaty that forced the Quapaw to give up their land. The federal government compelled the removal of Native peoples from huge tracts of land in the early nineteenth century, decades before the Morrill Act of 1862. Because decades passed between some of these removals and the passage of the act, and because the removals were never for the stated purpose of promoting the growth of higher education, the link between land-grant colleges and dispossession is not always readily apparent. However, without that earlier forced removal, the Land-Grant Act would not have been possible; without the earlier dispossession, there would have been no land to sell to support colleges and universities.

The Land-Grant Colleges

Because eastern states benefited from this legislation, existing colleges had to be designated as the state's land-grant institution. Some of these were private colleges: Rutgers in New Jersey, Sheffield Scientific School at Yale in Connecticut, Brown in Rhode Island, and MIT in Massachusetts (but only the mechanical arts program; soon, though, MIT would have to share the funding with the new state agricultural college, which later became the University of Massachusetts at Amherst). Others were state colleges (the universities of Georgia, Tennessee, Delaware, Missouri, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Florida, Louisiana, and Vermont), and some were new state agricultural colleges (Michigan, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Iowa). These all existed in 1862 when the Morrill Act passed. Additional institutions were founded after 1862: the private college Cornell (New York), state universities in Massachusetts, Kentucky, Maine, New Hampshire, Illinois, California, West Virginia, Nebraska, Arkansas, Ohio, and Nevada; and new agricultural and mechanical arts colleges in Colorado, Mississippi, Kansas, Oregon, Indiana (Purdue), Texas, Alabama, and Virginia.Footnote 65

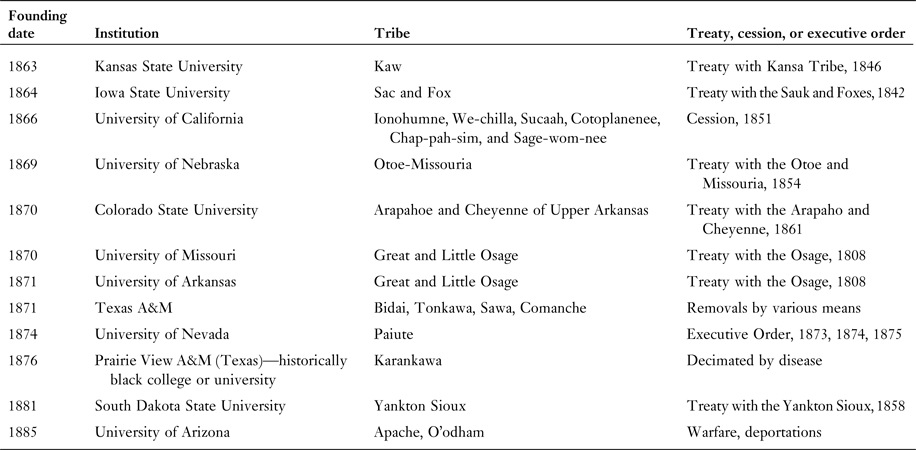

One way to link land-grant colleges with Native dispossession is to look at the land on which those land-grant institutions were built and determine the tribes that previously lived on that land. Because the goal here is to show that the Morrill Act is complicit in the process of westward expansion and Native dispossession, the scope of this investigation is limited to institutions founded west of the Mississippi in the decades after 1862. Table 1 lists this information for land-grant colleges established between 1863 and the Hatch Act of 1887, which funded agricultural experiment stations and expanded the scope of institutions that could receive land-grant revenues. Often, more than one tribe lived on or used land that later became associated with colleges or universities. Where multiple tribal affiliations are known, they are included in the table, which also shows how the federal government claimed the land.

Table 1. Land-grant universities founded between 1863 and 1887 and the tribes that previously lived on the land

Sources: Tribal affiliations from Invasion of America, eHistory.org, http://usg.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=eb6ca76e008543a89349ff2517db47e6. Treaty information from Charles J. Kappler, Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1975); and DeJong, American Indian Treaties.

Before 1871, the official means of acquiring Native land was sometimes by treaty. The use of treaties casts a veneer of respect and humanity over the removals, as tribal councils did negotiate, to some extent, the terms of the treaties. But, as historian David J. Wishart writes, “In the final analysis, it was a compulsory purchase … [and] it was the United States that set the conditions of the divestiture.”Footnote 66 Unofficially, with or without governmental sanction, settler attacks against American Indians forced their removal. After 1871, the federal government no longer entered into treaties with tribes, which assumed an independence and autonomy that the federal government no longer wanted to perpetuate. Instead, the government designated tribes as wards of the government with no authority to sign treaties.Footnote 67

The Otoe-Missouria and the University of Nebraska: One Case Study

New land-grant colleges and universities in the West were both built on and funded by land that the federal government had taken from various tribes. Each of these western institutions has its own story, and future research could develop each of these histories. One example is briefly discussed here: the Otoe and Missouria tribes, whose loss of land benefited the University of Nebraska.

The University of Nebraska was founded in 1869 in Lincoln, the capital of the new state (Nebraska became a state in 1867). The capital of the territory and then the state had been Omaha, but the capital was moved to Lancaster in 1867, at which time the city was renamed Lincoln.Footnote 68 Situated in the southeastern part of the state, the land had been inhabited by various tribes, including the Otoe and Missouria. The federal government first acquired a large section of Otoe-Missouria land east of Nebraska, in what is now Missouri, through the fourth Treaty of Prairie du Chien, in 1830. This treaty forced multiple tribes to stay west of the Missouri River, resulting in diminished resources, including game. The treaty was deceptive from the start. William Clark, who was a superintendent of Indian affairs for the region, encouraged the tribes to sign the treaty by telling them that “we don't purchase those lands with a view to settling the white people on them,” while simultaneously telling the Commissioner for Indian Affairs that we “will have a disposable country of the best lands on the Missouri.”Footnote 69 In return for this land, and for further land in Kansas in an 1833 treaty, the federal government promised to provide $2,500 a year for twenty years, $500 each year for education, $1,000 worth of cattle, and the help and advice of two farmers for five years, provided that all members of the tribe ceased hunting. The Otoe-Missouria had ceded one million acres of land, for which they received the equivalent of 4.1 cents an acre.Footnote 70

By the 1840s, thousands of people were migrating west through Nebraska—first to Oregon, and then to California in the gold rush. Those thousands of people had heavy footprints, as they chopped down trees for firewood, trampled the grass, and decimated what little game was left. Meanwhile, the Dakota Indians were moving into Nebraska from the north, with the federal government supplying them with arms. All of this left the Nebraska tribes in “a wretched condition” of starvation.Footnote 71

The situation worsened after Congress passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, officially opening up the area to white settlement. The federal government gave tribes one year to sell their land and move onto their designated reservations. The Otoe-Missouria sold their land, including the area that would become the University of Nebraska, and moved to a reservation near the Kansas border. The reservation system required that the tribes submit to the allotment system, in which each head of a family received one section of land to farm; after receiving their allotment, any leftover land was sold to white settlers. Any tribal members unwilling to become farmers on an allotment “would be deported further west until they changed their ways or perished.”Footnote 72 Perish, they did—in 1858 alone as many as forty tribal members (out of roughly seven hundred) died of starvation and illness. The federal government promised to provide annual payments that would decrease each year, with the idea that over time farming would sustain the tribes. The payments, even in the early years, were low, averaging roughly $18 per person in 1860, at a time when blankets cost $8 apiece and a bag of flour cost $15.Footnote 73

A drought in 1860 led to harvest failure, resulting in more starvation. White settlers were impacted by the drought too, but they had the right to leave the area, which many did. Confined to the reservation, the Otoe-Missouria could not.Footnote 74 In 1867, severe flooding, followed by another year of drought, led to horrible conditions. In the spring of 1869, forty-eight children died—one-quarter of all the Native children on the reservation. By 1870, the total population of Otoe-Missourians was down to 434.Footnote 75

White settlement in Nebraska increased dramatically after the Civil War, aided in part by the Morrill Act. In 1871, Governor David Butler pointed to the reservations as “some of the choicest agricultural lands in the state” and argued that the Indians be removed and the land opened up to settlers.Footnote 76 The commissioner of the Indian Office agreed, writing in 1872 that “the Westward course of population is neither to be denied or delayed for the sake of all the Indians that ever called this country home. They must yield or perish.”Footnote 77 The Otoe-Missouria finally moved to Indian Territory, in what is now Oklahoma, in two stages in 1876 and 1881. The soil on their new land was infertile, and both timber and water were scarce. The population dropped to 340 in the 1890s before recovering. Yet the group staunchly stayed, as much as possible, rooted in their “traditional” ways. Jesse Griest, a Quaker serving as an Indian Agent, reported in the 1870s that the Otoe-Missouria resolutely refused to become Americanized, remaining “wedded to the traditions of their ancestors,” refusing Western medicine and continuing to live in earth lodges and tipis, and “unwilling to give up the hope that they might return to the unrestrained life of the forefathers.”Footnote 78 Over time, however, as the federal government removed children from parents and sent them to boarding schools, “much of the language has been lost,” and today “the tribe is struggling to maintain what knowledge of the language still exists.”Footnote 79 The tribe currently has a population of about fifteen hundred in Oklahoma.Footnote 80

The founders of the University of Nebraska had none of this in mind, of course, when they built the first building. The Otoe-Missouria had relinquished that land under duress decades before the university broke ground. Yet the university could not exist without the tribes ceding their land. Other land-grant institutions could unearth similar histories as well. Clearly, newly formed land-grant institutions in the West following the Morrill Act were founded on land that had been appropriated from various tribes, whether that appropriation occurred shortly before the institution's founding or decades prior.

Funding for Eastern Land-Grant Colleges

However, this was not the major way that colleges and universities took advantage of appropriated land. The act designated public lands be sold to benefit certain types of higher education based on the number of congressional representatives each state had. With the vast majority of the population in the East, most congressional representatives therefore came from eastern states. The act had to offer something to eastern states, not just to new western states; without this, the act would not have gotten through Congress. As a result, older, established colleges in the East gained far more revenue from the sale of western lands than western colleges.

Tracking these sales requires using the extensive Bureau of Land Management database.Footnote 81 Sorting by type of sale (for instance, cash purchase, railroad allotment, veteran grant) allows us to see what parcels in each state were sold under the Agricultural College Land Grant, the designation given in the database for Morrill Act sales. Each deed of sale provides the purchaser's name and which state's college received the proceeds. The deed also identifies the county, making it possible to find out which tribes had previously lived on the land and what treaty or cession was used to remove them. What follows is a summary of this information for two states: Arkansas and Missouri.

Arkansas had seventeen parcels of land that were purchased with agricultural land-grant college scrip, in the following counties:

• Benton: Benton County is in the extreme northwest corner of Arkansas. The Wahzhazhe (Osage) tribe inhabited this area, and the land was part of the Great and Little Osage Treaty of 1825, formed for the purpose of “direct commercial and friendly intercourse” between the US and Mexico.Footnote 82 In particular, the US wanted to build a road from the western frontier of Missouri to New Mexico, and to do so they needed the agreement of the tribes living there. This first treaty was only for the space of the road, along with “a reasonable distance on either side” so that travelers could camp and find provisions on their way.Footnote 83 The tribes were to receive $500. Rights to roadways was not enough for long, and another treaty followed in 1839 in which the Wahzhazhe (Osage) ceded all of the land to the US and moved to a small reservation in what is now Oklahoma in exchange for cash, goods, a grist and saw mill, and other provisions.Footnote 84 One parcel of land eventually sold to benefit the land-grant college of Massachusetts came from this county.

• Clark, Garland, Howard, Pike, Saline, Sebastian, Sevier, and Yell: This is a large area surrounding and including Hot Springs, reaching south and west from the Arkansas River on which the Quapaw lived. In the first treaty, in 1818, the Quapaw agreed to “be under the protection of the United States,” and ceded all land to the US.Footnote 85 The treaty permitted the Quapaw to live, hunt, and farm there, but no individual tribe members owned any of it, and the tribe could not sell the land to any person or entity other than the US government.Footnote 86 The US stipulated that this agreement would hold as long as the Quapaw remained peaceful, or didn't injure or annoy any US citizens (“so long as they demean themselves peaceably, and offer no injury or annoyance to any of the citizens of the United States”) or until the US decided to give hunting permission to other “friendly Indians.” No US citizens were allowed to settle on or hunt on this land, but all were permitted to “travel and pass freely, without toll or exaction,” through the reservation, and the US had the right to build any roads they wanted. In return, the US would immediately provide $4,000 in goods and merchandise and $1,000 worth of goods annually.Footnote 87 This agreement did not last long. In 1824, a second treaty moved the Quapaw to an area already inhabited by the Caddo tribe. This area frequently flooded and apparently was unhealthy in other ways (“a very sickly country”), and one-fourth of the tribe died within a few years. A third treaty, signed in 1833, gave them new land between the Senecas and Shawnees—this time not to be shared.Footnote 88

The other counties within the region of the Quapaw Treaty were also affected by the 1820 treaty with the Choctaw (also known as the Treaty of Doak's Stand). This treaty took the Choctaw from Mississippi and moved them west of the Mississippi River into what later became Arkansas. By 1825, the United States changed its mind and forged a new treaty that, recognizing that white settlers had already moved onto Choctaw land, pushed the Choctaw west of the Arkansas River. The United States promised that any whites who had already settled west of the river would be moved east of it. The US would also pay the Choctaw Nation $6,000 per year “forever.” For the first twenty years, that money would go into a school fund, presumably to acculturate Choctaw into US customs, and also specifically to teach “mechanic and ordinary arts of life.”Footnote 89 Whatever the intent of the Choctaw school administrators, students used the education for their own purposes. As historian Christina Snyder shows, students did not simply abandon Indigenous knowledge and culture but rather “added or adapted new knowledge to their own deep intellectual traditions.”Footnote 90 Many alumni became intellectuals, taking on leadership roles, speaking for tribal interests, engaging in transatlantic and transhistorical conversations, and articulating “a more empowering narrative of both American and global history.”Footnote 91 Other tribes, too, including the Creek, experimented with forms of schooling, funded in part by treaties, as strategies to “shape their society and reinforce their identity in the postremoval nation.”Footnote 92 Under difficult conditions, Native peoples sought ways to retain their cultures.

Clark and Saline counties each had one parcel of land designated for land-grant colleges, one benefiting the state of Maine and the other the state of Virginia. Garland County had two parcels, one supporting the land-grant college in Alabama, the other supporting the college in West Virginia. In Howard County, two parcels of land were purchased with land-grant college scrip, benefiting Delaware and Connecticut. Single parcels each in Sebastian County benefited Mississippi, Sevier County benefited Connecticut, and Yell County benefited West Virginia. The remaining county in this region, Pike County, had six parcels sold for land-grant colleges, all of which benefited Connecticut. Arkansas's seventeen parcels of land, then, went to benefit the designated land-grant colleges in Alabama, Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Mississippi, Virginia, and West Virginia.

In Missouri, 1,255 parcels of land were bought using land-grant college scrip. For the most part, each parcel was 160 acres; sometimes the parcels were a bit more or less, depending on the parcel's topography. The 160-acre figure is used as an average to provide a good estimate of the amount of land involved. The 1,255 parcels roughly equal 200,800 acres of land. All of Missouri was involved in at least one treaty with tribes, and some counties were involved in more than one treaty, as the US government pushed tribes from one end of the state to the other. Not every county had land that was designated for land-grant colleges. The six counties that did not (Lincoln, Montgomery, Pike, Ralls, St. Charles, and Warren), in the region that includes and surrounds the state's major city, St. Louis, were all part of an 1804 treaty with the Sauk and Fox.Footnote 93

Andrew, Atchison, Buchanan, Holt, Nodaway, and Platte counties were part of an 1830 treaty with the Confederated Tribes of the Sauks and Foxes; the Medawah-Kanton, Wahpacoota, Wahpeton and Sissetong Bands of Sioux; and the Omahas, Ioways, Ottoes, and Missourias. This treaty gave huge tracts of land to the US government but preserved separate tracts for each tribe along with a swath of land that any of the tribes could use for hunting. In exchange, the US gave cash and offers of goods, along with an agreement to set aside $3,000 a year for ten years for children's education.Footnote 94 By 1837, that land was also taken away when President Martin Van Buren “extinguished” all Indian titles to northwestern Missouri.Footnote 95 The 1837 treaty forced the cession of 1,250,000 acres.Footnote 96 Twenty parcels of land, roughly 3,200 acres, from this part of the state were bought with scrip designated to benefit land-grant colleges.

Much of Missouri was part of the treaties with the Great and Little Osage of 1808 and/or 1825, described earlier. A substantial amount of land was bought with land-grant college scrip: 1,046 parcels, amounting to roughly 166,760 acres. Cedar, Lawrence, St. Clair, and Polk counties were part of the treaty with the Kickapoo on October 24, 1832. The Kickapoo gave up all their land in what is now Missouri and were relocated to what is now Kansas. The US government agreed to pay the tribe $18,000—the majority of which ($12,000) was “placed in the hands of the superintendent of Indian affairs at St. Louis.” The US also paid for the support of a blacksmith and some tools, the erection of a mill and a church, and $500 a year for ten years to support a school.Footnote 97 Thirty-seven parcels of land-grant college land, or 5,920 acres, came from here.

Barry, Christian, Greene, Stone, Taney, and Webster counties were part of a September 24, 1829, treaty with the Lenape (Delaware), who had already been forcibly moved from the mid-Atlantic to Ohio and then to Missouri. Now they were being moved to what is now Kansas. The treaty optimistically—and wrongly—promised that this new site would be Delaware land “forever, the quiet and peaceable possession and undisturbed enjoyment of the same, against the claims and assaults of all and every other people whatever.”Footnote 98 Within twenty years, the federal government once again removed the Lenape, this time to what is now Oklahoma.Footnote 99 Of this Lenape land in Missouri, 133 parcels, or over 21,000 acres, was bought with land-grant college scrip.

Douglas, Ozark, and Wright counties were part of a treaty with the Shaawanwaki, Sa'wano'ki, and Shaawanowi lenaweeki (Shawnee) tribes on November 7, 1825.Footnote 100 This group had already been pushed into Missouri from the eastern woodlands and were now being pushed into Kansas and eventually Oklahoma. One hundred and forty-eight parcels of this land (roughly 38,500 acres) were purchased with land-grant college scrip.

The beneficiaries of the sale of this 200,800 acres in Missouri were land-grant colleges in nineteen states east of the Mississippi. The primary recipient was West Virginia, which gained income from 479 parcels (76,640 acres). Other major beneficiaries included Pennsylvania (170 parcels, 27,200 acres), Maine (111 parcels, 17,760 acres), Ohio (108 parcels, 17,280 acres), and Kentucky (98 parcels, 15,680 acres). Table 2 lists all the parcels by state.

Table 2: Missouri land sold for land-grant colleges and universities by state that benefited

Conclusion

As Dahl notes, “Dispossession was not an unfortunate by-product of modern democracy…. Institutions and ideologies of conquest and colonization … were closely linked to the development of democratic ideals and institutions.”Footnote 101 Some of those institutions that existed not in spite of but because of dispossession were the land-grant colleges. Dahl argues that taking Native dispossession into account requires a complete rethinking of the foundations of democratic practice and of the “ethical and political basis of modern democracy.”Footnote 102 The same is true of our great land-grant colleges and universities. We cannot continue to see them as “democracy's colleges” without also continuing to ignore the systematic Indian dispossession that led to their founding. The land-grant colleges could not have existed without the settler colonial ideology that led to their existence and growth.

While the ideology of settler colonialism shaped the laws and policies that led to the various land-grant acts, the reality was different. Although the goal of the Homestead Act and the Morrill Act had been to establish self-sufficient family farms, much of the scrip actually went to speculators. As noted earlier, the vast majority of Ohio's scrip (576,000 out of 630,000 acres)was bought by just three people.Footnote 103 Historian Walter Hart Blumenthal writes that the “fever of land speculation, apart from the push of settlement, motivated the ousting of the tribes and their confinement to reservations. Many clashes were not the result of frontier encroachment by hardy settlers, but were provoked in remote regions—areas sought for mercenary or political reasons.”Footnote 104 Blumenthal cites, for instance, the discovery of gold in the Black Hills and the development of the Santa Fe Trail as important for commerce rather than settlement. “The land goad for profit was the underlying dynamic,” argues Blumenthal, “with settlement as a subsidiary impulse.”Footnote 105 Historian Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz also argues that most land wrested from Indigenous peoples “ended up in the hands of land speculators and agribusiness operators.”Footnote 106 Similarly, Wishart writes that it “is no small irony” that the settlers who poured into Nebraska were not primarily farmers but “small- and large-scale speculators bent on exploiting the fluid frontier economies.”Footnote 107

This was certainly the case with the land-grant scrip used in Missouri and Arkansas. For instance, a team of speculators—Thomas Mason, George Satterlee, and William Dodge—bought up about forty scrip certificates, which they used to buy 6,520 acres of land in Arkansas and Missouri, some of which they held onto for decades before selling at a large profit.Footnote 108 Numerous buyers bought far more than the 160 acres that land-grant program architects intended. One particular person, Robert Mears, stands out for his acquisition of 26,780 acres of Missouri land. He may have purchased the largest amount, but he was hardly alone in buying in quantities that far exceeded 160 acres. John Gray bought 4,960 acres, Richard Melton 4,800 acres, David Wolf 1,600 acres, Andrew Sproule 3,520 acres, Thomas McCann 1,920 acres, and John Orr 960 acres. These are just a few examples of large purchases. It would be more notable to find the one or two buyers who bought a single parcel of 160 acres. Each of these people likely bought or acquired additional land, as well, through the Homestead Act or other types of sales; the research here accounts only for land bought with land-grant college scrip. If the Morrill Act was supposed to civilize the West through the establishment of yeoman farmers, it may have failed. Instead, large-scale farming businesses owned by a small group of people dominated the landscape.

Higher education is often spoken of as creating opportunities for social mobility, and for some people this has been true. Plentiful critiques of that view also demonstrate the limitations on access and outcomes for people based on race, gender, and class.Footnote 109 That inequalities exist comes as no surprise, especially given the number of studies demonstrating that higher education “from its genesis, has been a primary force in persistent inequities.”Footnote 110 Wilder's work shows the role of slavery in early colleges, documenting that racism was not merely incidental to the colleges but was instead foundational and formative.Footnote 111 Racism was also at the root of the founding of the land-grant colleges. The economic capital that funded those colleges simply would not have existed without the racist belief that Native peoples had no right to land or to self-determination. As Stein writes, “The U.S. federal government's vigorous efforts to accumulate indigenous lands in the nineteenth century provided the conditions of possibility for the Morrill Act.”Footnote 112

Jacobs writes that although “clearly a politically fraught task, confronting settler narratives is a crucial responsibility in coming to terms with our entangled pasts and mediating multiple interests in the places we now share and each call home.”Footnote 113 Coming to terms with the entangled pasts of some of our great educational institutions also needs to occur. As institutions are finding ways to make reparations to the descendants of enslaved people who made those colleges and universities possible, some land-grant institutions are coming to terms with their legacy.

One way to do this is through land acknowledgement statements. Such statements have been common in Canada for several decades, and recently some US institutions (art museums as well as colleges and universities) have adopted them, including land-grant universities. For instance, the University of Illinois System includes a statement on its website recognizing that the land had been home to

indigenous peoples who were forcibly removed and who have faced two centuries of struggle for survival and identity in the wake of dispossession. We hereby acknowledge the ground on which we stand so that all who come here know that we recognize our responsibilities to the peoples of that land and that we strive to address that history so that it guides our work in the present and the future.Footnote 114

Colorado State University uses its statement to recognize the special responsibility it has as a land-grant institution, noting “that our founding came at a dire cost to native nations and peoples whose land this university was built upon. This acknowledgement is the education and inclusion we must practice in recognizing our institutional history, responsibility, and commitment.”Footnote 115 Michigan State University's statement acknowledges that the university occupies the “ancestral, traditional, and contemporary lands of the Anishinaabeg,” and cites the 1819 Treaty of Saginaw that forced the cession of the land. The statement ends by saying, “By offering this Land Acknowledgement, we affirm Indigenous sovereignty and will work to hold Michigan State University more accountable to the needs of American Indian and Indigenous peoples.”Footnote 116

Land acknowledgement statements are a good first step but should not be the only step. As Rachel Mishenene, an Ojibwa educator, says, “A land acknowledgement without action is just a statement.”Footnote 117 In addition to a simple acknowledgement, universities might make themselves accountable, as the Michigan State University statement says, to the needs of local Native populations. Universities might foster strong relationships with tribal communities, offer support services for Native students, promote courses and programs that teach Native cultures and histories, and in other ways serve Native populations. Some colleges and universities, land-grant and not, are taking these steps.Footnote 118

Sociologists Pierre Bourdieu and Jean-Claude Passeron coined the term genesis amnesia to draw attention to processes by which societies cover up or erase the origins of policies or institutions in order to obfuscate the social constructions that underlie them.Footnote 119 It was genesis amnesia that allowed people to believe that colleges like Harvard, Princeton, and Georgetown had no meaningful connection to slavery, and it is genesis amnesia that allows us to believe that “democracy's colleges” were founded primarily to increase access to higher education. Their existence entirely depended on the forced removal of Indigenous peoples, the expropriation of Native land, and the erasure of that history. Educational institutions benefited and, as a result, higher education was more easily available and more affordable to more people than ever before. But the founding of the land-grant institutions came at a great cost. Perhaps it is time to replace that amnesia with genesis apperception: an introspective self-consciousness of the origins of our institutions.Footnote 120 From that awareness we can move toward the possibility of meaningful reconciliation and change.