1 Introduction

‘[O]nce one acknowledges that the law does not exist as a preformed set of rules which judges simply discover and apply to the facts at hand, and that on occasions the judge must form her or his own view as to what should happen, it follows that who the judge is matters.’ (Rackley, Reference Rackley2013, p. 132, emphasis in original)

Many arguments for judicial diversity have centred on demographic difference and the importance of a bench that reflects the population it serves (Rackley, Reference Rackley2008; Reference Rackley2013; Hunter, Reference Hunter2015; Richardson-Oakes and Davies, Reference Richardson-Oakes and Davies2016; Levin and Alkoby, Reference Levin and Alkoby2019). Evidence of judicial diversity is testimony to equality of opportunity in the legal profession and provides inspiration to traditionally underrepresented populations to pursue professional and public-service careers (Goldman and Saronson, Reference Goldman and Saronson1994; Hale, Reference Hale2001; Davis and Williams, Reference Davis and Williams2003; Lawrence, Reference Lawrence, Dodeck and Sossin2010). There is also an increasing body of literature examining how diversity may have an impact on legal process and decision-making, including how legal issues are analysed and judgments are written (Hunter, Reference Hunter2015; Boyd, Reference Boyd2016; Douglas and Bartlett, 2016; Roach Anleu and Mack, Reference Roach Anleu and Mack2017). These arguments in favour of judicial diversity have frequently focused on easily quantifiable demographic variables, such as gender and ethnicity (Hale, Reference Hale2001; Douglas and Bartlett, 2016).

Studies continue to raise the question of whether demographic variables can, or should, be considered a proxy for decisional difference (Hunter, Reference Hunter2008; Rackley, Reference Rackley2009; Baines, Reference Baines, Schultz and Shaw2013; Sommerlad, Reference Sommerlad, Schultz and Shaw2013; Cahill-O'Callaghan, Reference Cahill-O'Callaghan2015; Hunter et al., Reference Hunter2016). Indeed, at the heart of Rackley's argument that the identity of the judge matters (quoted above) is the premise that what matters is the combination of the individual's values, preferences, perspectives and priorities (Rackley, Reference Rackley2013). This inclusive perspective is supported by a growing body of psychological literature that notes the many facets of personality that influence decisions (Finegan, Reference Finegan1994; Sagiv and Schwartz, Reference Sagiv and Schwartz1995; Judge, Reference Judge2002; Caprara, Reference Caprara2006; Hackett, Reference Hackett2014; Hall, Reference Hall2018).

Despite the clarity of arguments supporting judicial diversity, however it is conceived, the appointments processes to apex courts in many countries remain firmly entrenched in a conception of merit that has yet to include recognition of the importance of diversity (Malleson, Reference Malleson2006; Reference Malleson2018; Malleson and Russell, Reference Malleson and Russell2006). Indeed, ‘merit’ has been the dominant government rhetoric around High Court appointments in Australia, as illustrated by the then Attorney General's welcome speech to High Court Justice Geoffrey Nettle: ‘Your selection was based upon one criterion and one criterion alone, your outstanding ability as a lawyer and as a Judge’ (Nettle, Reference Nettle2015).

However, it has long been understood that the nebulous concept of merit perpetuates the dominant characteristics of those making the appointments. Many critiques argue that masculinist understandings of merit serve to exclude women from judicial appointment (Malleson, Reference Malleson2006; Thornton, Reference Thornton2007; Rackley, Reference Rackley2013; McLoughlin, Reference McLoughlin2017; Lynch, Reference Lynch, Gee and Rackley2017). But less is known about how a merit-based appointment process impacts on the other facets of diversity. This paper begins to explore this, through an analysis of High Court swearing-in speeches.

The seven judges of the High Court's bench are appointed by the Commonwealth executive government, whose power of appointment is limited by only three minimal requirements: a requirement to ‘consult’ with the state Attorneys General (High Court of Australia Act 1979 (Cth), s. 6); the mandatory retirement age of seventy (Constitution, s. 72); and a minimum professional experience of five years of legal practice or a prior judicial appointment in a superior court (High Court of Australia Act 1979 (Cth), s. 7). Beyond this, the appointment process is a secret, closed, ‘tap on the shoulder’ (Mack and Roach Anleu, Reference Mack and Roach2012).

The High Court has remained staunchly immune from attempts to introduce publicly available selection criteria like those implemented in a number of Australian courts (Handsley and Lynch, Reference Handsley and Lynch2015; AIJA, 2015). The opaque nature of High Court appointments extends to the limited release of information about the new judge. Government announcements may offer a cursory CV and Court websitesFootnote 1 will be updated after the swearing-in with career highlights. The media may fill further gaps, including a short note about the appointee's gender, age and experience (Lawson, Reference Lawson2002; Blenkin, Reference Blenkin2012). However, this information is not collated into a publicly accessible dataset. Consequently, judicial workplace diversity data are both sparse and patchy (Mack and Anleu, Reference Mack and Roach2012; Bartlett and Douglas, Reference Bartlett and Douglas2018; AIJA, 2020; Opeskin, Reference Opeskin, Appleby and Lynch2012). Recent increases in judicial (auto)biography, interviews and intellectual histories have offered some insights into individual judges, but these are published at the end of a judicial career (Josev, Reference Josev2017).

Against this background, judicial swearing-in ceremonies are the rare occasions on which the executive must publicly defend an appointment (Roberts, Reference Roberts2017) and the legal community endorses a judge's suitability for office. This occurs through a series of welcome speeches and is followed by the judge's inaugural speech. It is the judge's inaugural speech, and the insight it can provide into judicial identity, that this paper explores.

Judges’ swearing-in speeches are unusual narratives. They are made from the bench but have no judicial force. They are ritualised and constrained by conventions regarding appropriate judicial speech, but the judge alone selects its theme and how much detail to reveal about themselves (including family, socio-economic and educational background, personal beliefs and non-law interests) (Moran, Reference Moran, Schultz and Shaw2013; Roberts, Reference Roberts2014; Reference Roberts2017; Thornton and Roberts, Reference Thornton and Roberts2017). One speech can never be regarded as conveying a complete insight into an individual. However, justices in these speeches do provide a glimpse of how they see themselves and how they wish to be seen in these moments (Roberts, Reference Roberts and Baines2012b; Thornton and Roberts, Reference Thornton and Roberts2017). As such, judicial swearing-in speeches provide a novel and useful insight into the individuals appointed and the characteristics that the appointments process amplifies.

In recent times, the ‘ceremonial archives’ of courts (Roberts, Reference Roberts2014) have been used to illustrate changing views about the role of judges (Roberts, Reference Roberts and Baines2012b), sexuality (Moran, Reference Moran2006; Reference Moran2011; Reference Moran, Schultz and Shaw2013), class (Moran, Reference Moran, Milner Davis and Roach Anleu2018), judicial emotion and humour (Moran, Reference Moran, Milner Davis and Roach Anleu2018) and gender in the legal system (Roberts, Reference Roberts2012a; Reference Roberts and Baines2012b; Reference Roberts2014; McLoughlin, Reference McLoughlin2017; McLoughlin and Strenstom, Reference McLoughlin and Stenstrom2020). This paper takes this scholarship in a new direction, by exploring how a judge's swearing-in speech sheds light on facets of judicial identity.

Our study explores the swearing-in speeches of justices who sat on the ‘French High Court’ (September 2008 to December 2016): Chief Justice Robert French and Justices William Gummow, Michael Kirby, Kenneth Hayne, Dyson Heydon, Susan Crennan, Susan Kiefel (as puisne justice, not later as chief justice replacing French), Virginia Bell, Stephen Gageler, Patrick Keane, Geoffrey Nettle and Michelle Gordon. This period was selected because of the significant debates around this time that highlighted the importance of judicial identity – debates that were prompted by Heydon's criticism of judicial ‘bullies’ on the bench (e.g. Heydon, Reference Heydon2013; Gageler, Reference Gageler2014; Kiefel, Reference Kiefel2014; Keane, Reference Keane2014; Lynch, Reference Moran2015). We explore how points of similarity and difference – in demographic identifiers, personality traits and values – are manifest in the judges’ swearing-in speeches. We review what the justices say about themselves and the characteristics they chose to amplify in this public ceremony. This data provide a reflection of the individual and an insight into the individual characteristics that the institution promotes through the appointment system. Welcome speeches at a judicial swearing-in ceremony are also made by the Attorneys General and presidents of representative legal bodies (such as the Bar Associations or Law Council of Australia). These speeches also provide insights into the demographic profile of judges, particularly their educational and professional backgrounds. We draw on some of these data for elements of the demographic analysis, particularly where these welcome speeches reinforce content choices made by the individual judges in crafting their narratives. However, we have chosen to limit our analysis of values and personality to the judges’ speeches alone, for it is through what the justices choose to say about themselves that we gain an insight into the individual justice.

The transcripts of the twelve justices’ swearing-in speeches were collated in the qualitative data analysis software package NVivo and analysed using three different frameworks. In section 2, we present content and narrative analysis that centres on demographic difference amongst the justices. Section 3 presents a content analysis of the speeches grounded in psychological models of personality and values that is used to explore personality traits and values expressed by the justices on these occasions. Our study highlights how the use of different frames of analysis can present insights into multiple layers of individual judicial identity. In doing so, we seek to offer a new perspective on judicial identity – one that has previously been overlooked in discussions of diversity framed around demographics.

2 Demographic discussions

‘It is my firm conviction that the Australian judiciary is, as a matter of social history, a truer reflection of our people and their values and aspirations than has been the case with judges in previous times and in other places. … the suggestions that one occasionally sees in the media to the effect that our judges are some sort of remote elite are quite wrong.’ (Justice Patrick Keane, swearing-in speech, Reference Keane2013)

Traditional discussions of judicial identity emphasise demographic characteristics, such as race and gender, as well as wider factors such as geographic background, age, socio-economic background and professional experience (e.g. Handsley and Lynch, Reference Handsley and Lynch2015; Nguyen and Tang, Reference Nguyen and Tang2017). We employed textual analysis, utilising the NVivo software package, to augment our readings of the transcripts to capture the ways in which the justices engage with these characteristics in their speeches. This analysis revealed that educational and professional experience, geographic origins, socio-economic background, and marital and family status all featured strongly in the justices’ speeches. Other characteristics, such as age and ethnicity, were rarely or only implicitly raised.

2.1 Recognising demographic identifiers: geography, marital status, socio-economic background and personal experience

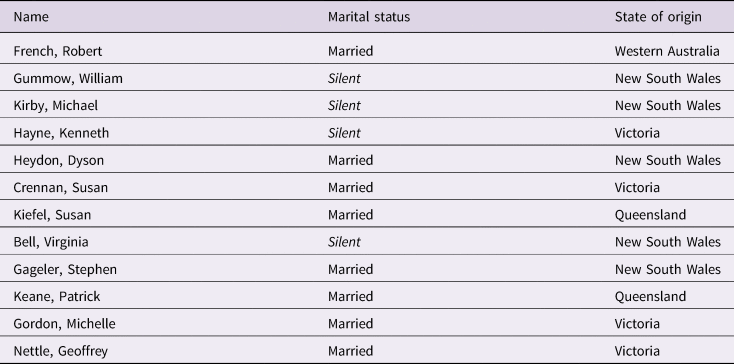

Table 1 indicates the states of origin of the justices and their marital status. Every justice acknowledged their geographic heritage in crafting their speech. As the highest court in Australia's federal system, the bench's geographic diversity has been long debated (The Argus, 1903). A speaker observed of Victorian Justice Hayne, for example, that ‘it is a happy coincidence, indeed, when a diversity of geographical origins can be maintained without compromise to the criterion of excellence’ (quoted in Hayne, Reference Hayne1997).

Table 1. Demographic attributes the justices chose to identify in their speeches (marital status and origin)

In our study, the majority of justices lived and worked principally in Australia's two most heavily populated states: New South Wales (Gummow, Kirby, Heydon, Bell, Gageler) and Victoria (Crennan, Hayne, Nettle, Gordon). Over 50 per cent of the Australian population resides in these two states. Chief Justice French is Western Australian and two justices came from Queensland (Kiefel and Keane). This pattern is broadly representative of the High Court's geographic diversity across its history (Evans, Reference Evans and Blackshield2001). Only Gageler was raised outside a capital city and so what geographic diversity is present on the bench has not extended to mirror Australia's rural and regional communities, even though one-third of Australia's population resides outside capital cities.Footnote 2

Eight of these justices also referred to their marital partners by name or status (Table 1). Same-sex marriage had not been legalised in Australia during our case-study and so the justices implicitly also claimed a sex identity (as husband or wife) through these statements. In four justices’ ceremonies, however, neither the justice nor any other speaker referred to the justice's spouse. Kirby, who came out as a gay man after his appointment to the Court, later explained his silence. He indicated that had he been open about his sexuality, the ‘reality of the world’ in 1996 was such that he ‘would probability not’ have been appointed (Kirby, Reference Kirby2011, p. 108; see also Kirby, Reference Kirby2009; cf. Kirby, Reference Kirby1996). Kirby's statement evidences the social and institutional pressures that silence homosexual judges in their swearing-in speeches. Some justices of lower courts have, more recently, acknowledged their gay and lesbian partners in their speeches (discussed in Roberts, Reference Roberts2014; Thornton and Roberts, Reference Thornton and Roberts2017). This has yet to occur in the High Court of Australia.

While marital status receives consistent, but only limited, discussion in the speeches, the justices devote greater attention to their educational and career backgrounds. This emphasis is not surprising given that the ceremony is designed to attest to their educational and professional attributes.

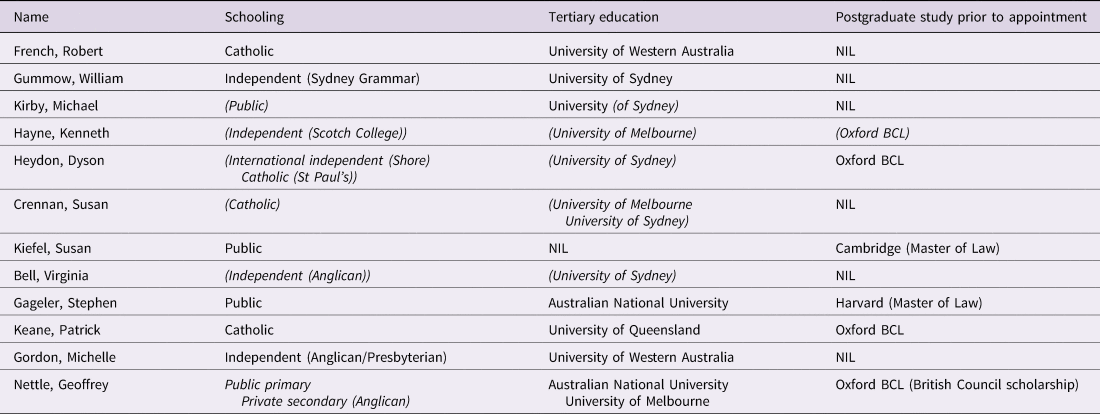

An extensive 2018 study of the career trajectories of Australian supreme- and district-court judges revealed that the majority of judges had attended independent and Catholic schools for their pre-tertiary education, followed by university education at the oldest and most prestigious universities in Australia (Bartlett and Douglas, Reference Bartlett and Douglas2018). The High Court justices in our study also followed those pathways (Table 2).

Table 2. Educational indicators of the justices

The information presented in plain font was identified by the justices in their swearing-in speeches. The data itemised in italics and brackets were noted in the welcome speakers’ remarks that preceded the judge's speech at the ceremony but are not contained in the justice's speech itself.

Table 2 indicates that justices perceived only parts of their educational background sufficiently relevant or important to identify in their swearing-in speech (represented by information in plain text in Table 2). In contrast, the full litany of a judge's educational attributes was referenced by welcome speakers at the ceremony as part of those speakers’ credentialing the justice.

All but three of the justices (Kirby, Kiefel, Gageler) were educated in independent or Catholic schools. This is the inverse of Australia's national average, as two-thirds of the Australian population were educated in government schools (e.g. ABS, 2016; Bartlett and Douglas, Reference Bartlett and Douglas2018). Gageler's educational experience differed in two ways from those of his fellow judges: he received his primary education at a one-room school with ‘effectively just one teacher’ and he received his postgraduate education at a US institution (LLM Harvard). Both experiences were acknowledged by Gageler as formative experiences in his speech. The other High Court justices with postgraduate education studied at Oxford and Cambridge (Hayne, Heydon, Kiefel, Keane, Nettle).

Justices Crennan and Kiefel (two of the four women in this study) were the only justices not to attend university full-time in order to gain their entry-level legal qualifications. Crennan was initially qualified as a trademark attorney, before working as a teacher and studying law part-time. A welcome speaker, but not the judge herself, suggested that Crennan pursued this path because she was the mother of small children. Kiefel left high school before graduation and then worked as a legal secretary. She obtained her legal qualifications through the Bar Accreditation course. These pathways are unusual within our case-study but are not atypical for pioneer women judges in Australia (Thornton, Reference Thornton1996). Indeed, Kiefel remarked in her speech that she had been surprised by the amount of attention paid to her background.

Bartlett and Douglas's study also confirmed that the majority of superior-court justices had consistent career trajectories, proceeding through the private Bar to take silk (known in some Australian states as Queen's Counsel, in others as Senior Counsel). Only Gummow and French had spent significant time as solicitors. In his speech, Gummow highlighted the advantage that this presented him with in his judicial role, as it brought an awareness of the ‘particular challenges and burdens faced by each component of the profession’ (Gummow, Reference Gummow1995). This is the only example in our study of a justice acknowledging that their lived experience offered a different, and advantageous, perspective in fulfilling their role.

Gageler is the only justice to come to the High Court without prior judicial experience. This is an unusual pathway to the Court. Since 1981, only two out of nineteen judges have been appointed straight from the Bar. Of the eleven justices appointed from a lower court, the majority had federal-court experience: a recognition of that court's significant role in the Australian judicial system. In our case-study, there is no appreciable gender difference between the length of time spent at the Bar or prior judicial experience between the male and female justices. Each of these eleven justices reflected in their speeches, to varying extents, on how their time on the bench had influenced their views on the judicial role.

Most of the French Court justices had predominantly constitutional, corporate and civil practice experience at the private Bar. In contrast, Kirby and Bell spent a significant proportion of their careers working in the fields of law reform and social justice. Kirby had been president of the Australian Law Reform Commission before serving on the New South Wales Court of Appeal; Bell had worked for the Redfern Legal Centre and had considerable experience as a defence lawyer in criminal cases before joining the bench. Interestingly, the similarities between Kirby and Bell's careers had led to media suggestions that Bell would display similar intellectual tendencies to those of her predecessor (Roberts, Reference Roberts and Baines2012b). It may have been to distance herself from comparisons between their careers, and intellectual philosophies, that Bell stated in her speech that she might not ‘as some people have suggested I should, fill the shoes of the Honourable Michael Kirby’ (Bell, Reference Bell2009). This distancing may also have been influenced by the fact that Bell, a lesbian judge, was replacing a gay judge on the bench (Roberts, Reference Roberts and Baines2012b), although, as noted in Table 1, each justice chose to remain silent on their relationship status in their speeches.

Within our study, the number of women on the High Court reached its historical high point. In 2009, Virginia Bell joined Susan Crennan and Susan Kiefel on the seven-member bench. At this time, the High Court of Australia almost reflected the gender profile of the Australian population (50.4 per cent women; ABS, 2016). The Australian legal profession has typically been populated what Thornton described as the ‘Benchmark Men’: male, married, Anglo-Saxon, able-bodied (Thornton, Reference Thornton1996). However, the women judges in our case-study did not allude to their gender, or gender discrimination, in their speeches (cf. Kiefel's later swearing-in speech, Reference Kiefel2007). While welcome speakers, and the media, have devoted considerable attention to coding the female justices as women lawyers and women (e.g. Roberts, Reference Roberts and Baines2012b; Thornton and Roberts, Reference Thornton and Roberts2017), Keane was the only justice who overtly referenced his gender. He did so as part of his tribute to his wife, when noting that:

‘the younger members of my family [must get] … dressed in uncomfortable clothes and taken to uncomfortable places where oddly dressed people say ridiculously kind things about the “old fella” when all the time they know that the only court of appeal in our lives that matters is the wise and just Shelley.’ (Keane, Reference Keane2013)

Keane was also the only justice to reflect directly upon the socio-economic diversity of the Australian judiciary. In the passage quoted at the commencement of this section, Keane disclaimed any suggestion that the Australian judiciary was sourced from an ‘out-of-touch’ elite. As our discussion of the career backgrounds of the justices would indicate, however, High Court justices were appointed from amongst Australia's legal elite, and accordingly Australia's highest personal-income tax bracket. In our pilot study, however, the justices’ education and work backgrounds in their formative teens and twenties suggest that they came from a broader socio-economic group. For example, not all justices attended independent and Catholic schools, education at such schools often being regarded as a proxy for high socio-economic status (Thornton, Reference Thornton1996). In addition, some justices attended private schools on scholarships for economically disadvantaged students (e.g. Gummow) and Kiefel did not complete high school. Moran has also demonstrated that reference to non-legal work experience in a swearing-in ceremony (such as factory work) can also allude to the class backgrounds of judges (Moran, Reference Moran, Milner Davis and Roach Anleu2018). In this context, Kiefel's journey is illustrative of a non-elite background, as is that of Crennan, for both were in full-time employment while completing their legal training. As such, although Keane was the only justice to overtly refer to class diversity in his speech, glimpses of this dimension of judicial identity, and diversity, emerge in the speeches.

2.2 Silences in the ceremonies: age and ethnicity

It is a constitutional requirement that High Court justices retire at the age of seventy (Constitution, s. 72). The age of the judges in our study at their appointment ranged from fifty-one to sixty-four (the average being fifty-seven). At sixty-four, Geoffrey Nettle is the oldest ever appointment to the High Court. Nettle was alone in our study in expressly referencing his age:

‘to invoke one of the Pythons’ more illustrious injunctions, “always look on the bright side”. The selectors may have backed a wild card, as the press put it, but, … the selectors have also capped the risk. Given … that I am now three score years and four, any damage I might do in the time which remains available is bound to be relatively limited.’ (Nettle, Reference Nettle2015)

Despite the importance of age as a demographic identifier, age was never publicly stated in a swearing-in ceremony, other than that of Nettle. Instead, the judges provide elliptical allusions to their ages by reference to historic or legal events that occurred during their journeys to the bench. Such references further reinforce the assumed knowledge of the audience at a ceremony – one can draw on shared experiences including legal idioms and allusions to give meaning to the speeches (Moran, Reference Moran, Schultz and Shaw2013).

The ceremonial archive also offers only limited and oblique glimpses into the ethnic backgrounds of the High Court justices. The names of each of the justices are read, in full, at the outset of the ceremony and suggest an Anglo-Saxon heritage. Only Heydon was born outside Australia, but this was not something that Heydon himself chose to acknowledge. In contrast, the 2016 Australian census indicated that 26 per cent of Australia's population were born overseas (ABS, 2016; Bartlett and Douglas, Reference Bartlett and Douglas2018; AALA, 2015). In other Australian courts, when a judge is appointed from a non-Anglo background, great attention has been paid to this in the ceremonies. In this context, silence in the High Court reinforces the perception of a lack of ethnic diversity on the bench.

This section has highlighted the demographic information that the judges chose to identify in their speeches and the importance of these different elements of identity. These speeches demonstrate a considerable homogeneity in the justices’ educational and career pathways, with geographic origin representing the largest point of difference. The following section examines facets of the individual judge that are not captured by traditional demographic identifiers.

3 Beneath demographics: personality and values in swearing-in ceremonies

The NVivo word analysis of the swearing-in speeches identified individual characteristics of the judges that were not captured by demographics. It has long been recognised that language can provide an insight into an individual's identity. These attributes, which include expertise, leadership, wisdom, kindness and respect, are encompassed within two facets of psychological constructs of identity – personality and values. To identify and quantify an individual's personality traits and values requires an individual judge to undertake psychometric testing. This is something that has not been attempted in this paper. As such, we do not make the claim that the traits and values that we identify below reflect core facets of the identity of the justices studied in this paper. Rather, the analysis that follows highlights the personality traits and values that the justices elected to affirm at the moment they introduced themselves to the public in their speeches. Further, although personality traits and values identified in text have been related to decision-making in the US and UK (Hall, Reference Hall2018; Cahill-O'Callaghan, Reference Cahill-O'Callaghan2020), this paper does not make this claim. Rather, the aim of this paper is to highlight how swearing-in speeches can be analysed to shed light on the personality traits and values expressed, and illuminate differences and similarities not generally considered in explorations of judicial diversity.

3.1 Judicial personality traits

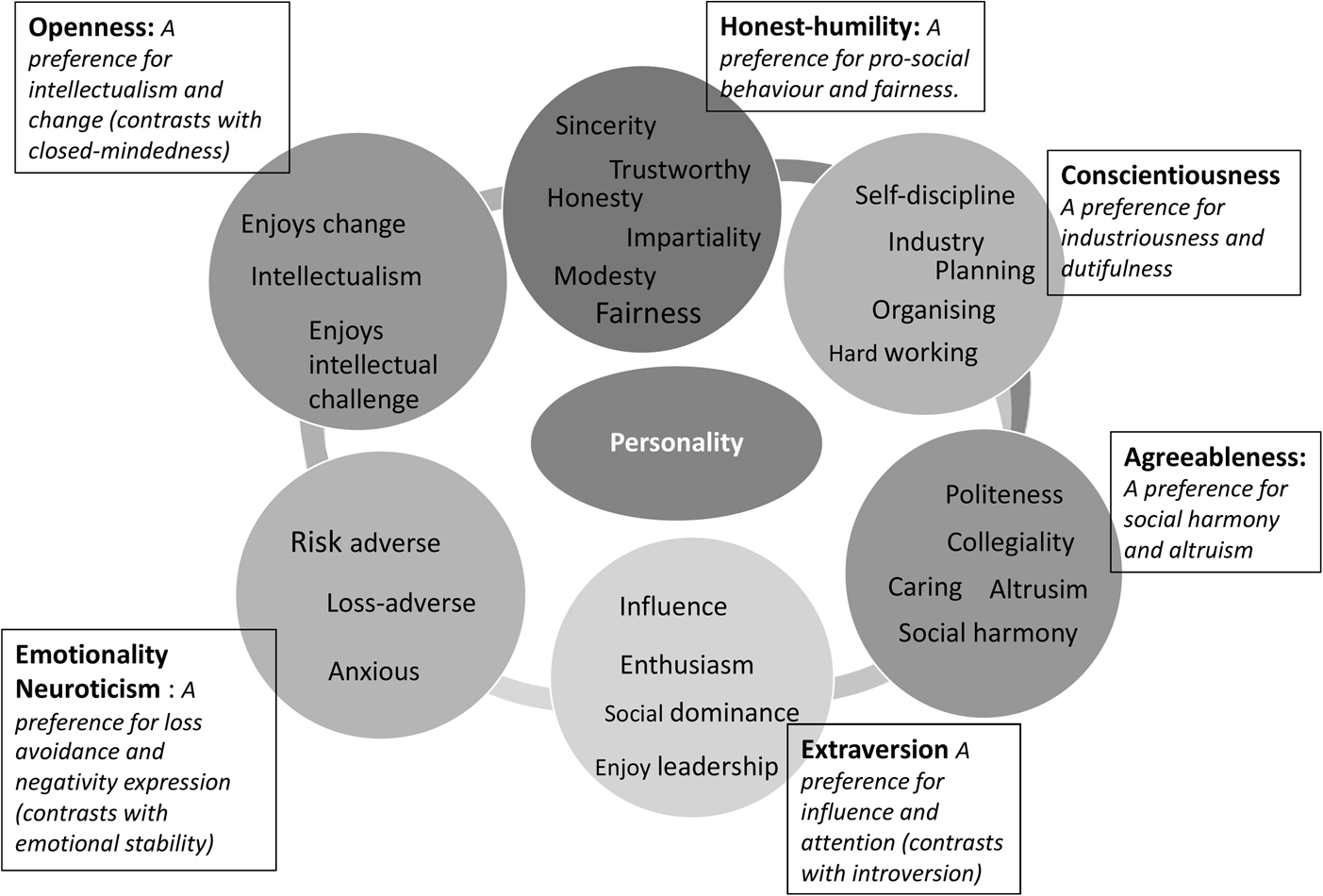

Personality traits are dimensions that categorise people according to the degree to which they manifest a particular characteristic (McCrae and Costa, Reference McCrae and Costa1994; Matthews et al., Reference Matthews, Deary and Whiteman2003; Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Walton and Viechtbauer2006; Reference Roberts2007). They are enduring dispositions that underpin consistent patterns of thoughts, feelings and actions. Figure 1 sets out the HEXACO model of personality: Honest-humility; Emotionality; Extraversion; Agreeableness; Conscientiousness; and Openness to experience. The model clusters characteristics of the individual into six traits that structure personality (for a review, see Ashton and Lee, Reference Ashton and Lee2007). Each trait represents a continuum along which an individual is placed. Those who are characterised as having intellectual curiosity and a willingness to consider others’ ideas, for example, would rate highly on openness. In contrast, those who do not score highly on these characteristics would be characterised as conventional. Each trait has dominant characteristics and these are represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Graphic representation of the HEXACO model of personality.

The HEXACO model provides a structure to understand the personality traits displayed by the justices through the text of their swearing-in speeches. We applied a coding framework in which we related the HEXACO personality trait to characteristics of the judicial personality derived from the literature (Tate, Reference Tate1959; Clark and Trubek, Reference Clark and Trubek1961; Gibson, Reference Gibson1981; Goldman, Reference Goldman1982; Solum, Reference Solum1987; Ray, Reference Ray2002; Posner, Reference Posner2006; Boudin, Reference Boudin2010; Handsley and Lynch, Reference Handsley and Lynch2015; Hall, Reference Hall2018). Table 3 summarises the most dominant personality traits found in the speeches and the justices who identified those traits.

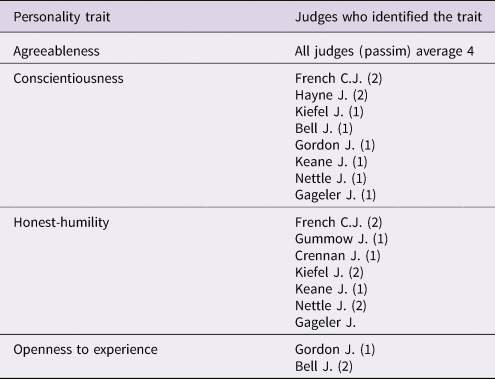

Table 3. Summary of traits affirmed by justices

The number of references is included in brackets after the justice. There is no suggestion that this is a quantitative study, rather that these traits are reflected in the speeches.

Four personality traits were evident in the speeches (agreeableness, conscientiousness, honest-humility and openness). It is no surprise that agreeableness, which includes friendship, collegiality and kindness, was espoused by every justice for the swearing-in speech has traditionally been deployed by judges to express appreciation to colleagues, family and mentors.

Eight judges in our study noted facets of personality encompassed within conscientiousness. Conscientiousness reflects characteristics such as self-restraint, self-discipline, hard work, thoroughness of legal research and power of logical analysis. It is associated with educational and employment success, as well as describing a degree of self-discipline and control (Barrick and Mount, Reference Barrick and Mount1991). Justice Bell, for example, explicitly referred to the ‘conscientiousness of judges’ in her speech (Bell, Reference Bell2009). Kiefel, like French and Bell, highlighted the importance of the judicial office and the responsibilities attached to the role in terms that encompassed conscientiousness:

‘I have been given this rare opportunity to serve on this Court and to take part in judicial decision making at its highest level. I feel deeply honoured by the appointment to this office and conscious of its responsibilities and burdens.’ (Kiefel, Reference Kiefel2007)

A further facet of conscientiousness is the trait of logical and critical analysis. Kiefel identified this trait when noting that judges have the ‘most difficult and demanding role, one requiring considerable powers of analysis’. Gageler, who, in contrast to Kiefel, came to the High Court without prior judicial experience, also emphasised conscientiousness when stressing the importance of a judge's critical analytical skills: ‘[M]y essential conception of the law, not as a mere collection of rules but as a reasoned approached to the resolution of contemporary controversies [is] informed by principled analysis of collective experience’ (Gageler, Reference Gageler2012).

Interestingly, although Heydon did not highlight the importance of conscientiousness in his swearing-in speech, Keane (Heydon's successor) described the trait as key to Heydon's character: ‘Justice Heydon set a standard of erudition and rigour in the pursuit of justice which is an example to all Australian judges, even if it is an example that none of us could hope to emulate’ (Keane, Reference Keane2013).

A further dominant personality trait, espoused by seven justices, was honest-humility. This trait emphasises trustworthiness, honesty, integrity, impartiality and modesty, and represents a tendency to be fair and genuine when dealing with others. Honesty was a foundational trait that Gageler expressed: ‘I start with my parents. Their early example of honesty and hard work gave me a moral compass’ (Gageler, Reference Gageler2012).

Within the judicial swearing-in speeches, impartiality in judicial adjudication is also, not surprisingly, a recurring theme. For example, Crennan emphasised impartiality (encompassed within honest-humility) in the following terms: ‘I have referred to a judiciary which transfuses fresh blood into our polity and of the law as a living instrument conjure up human qualities needed for the impartial dispensation of justice according to the law’ (Crennan, Reference Crennan2005).

This was also a theme that French embraced when he emphasised the importance of fairness:

‘It requires us to examine and re-examine the way in which we do things and to look for ways of doing them better. The courts are human institutions… the fundamentals of our system of justice require decision making that is lawful, fair, and rational.’ (French, Reference French Hon.2008)

Like French and Crennan, Gummow also expressed traits of honest-humility through the lens of judicial impartiality. However, Gummow's approach was to refer to United States Supreme Court Justice Learned Hand as the epitome of judicial virtue, by observing:

‘[L]earning, impartiality, an awareness of the limitations implicit in the special authority of the judicial branch of government in our federation. … an intellectual detachment and a belief that the road to the result can only be along the quiet path of reason and reflection.’ (Gummow, Reference Gummow1995)

It is perhaps unsurprising that the justices chose to emphasise the personality traits encompassed within honest-humility. These traits align so closely with the values of the legal system. While these personality traits were consistently emphasised, only two justices affirmed openness to experience. For example, Gordon explicitly emphasised innovation: ‘The Federal Court had, and continues to have, a collection of judges marked by intellectual rigour, innovation and excellence’ (Gordon, Reference Gordon2015).

Openness to experience was the only personality trait in our limited dataset that may be related to a traditional demographic identifier – gender – as both Justices Bell and Gordon are female. No other demographic identifier is reflective of the dominant personality traits evidenced in Table 4.

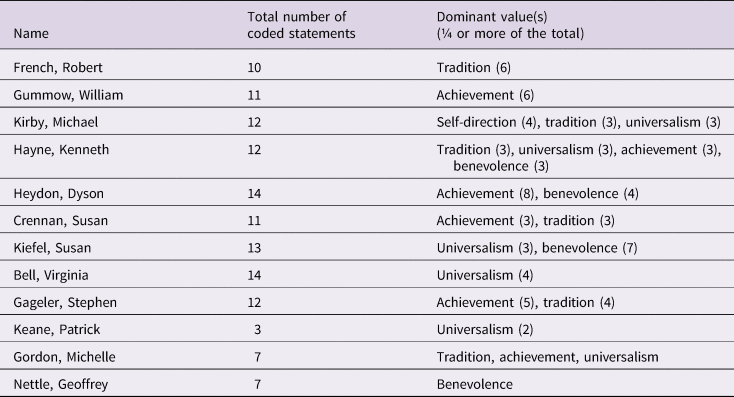

Table 4. Summary of dominant values in the speeches of the judge

The dominant values that reflect more than a quarter of the values expressed in the speeches are presented in the table. The number of coded sections is included to indicate the extent to which these values are expressed rather than to suggest that this is a quantitative study. The presence of dominant values suggests that, in this short speech, the justice chose to amplify specific values.

Overall, the fact that many of the High Court justices affirmed elements of conscientiousness as central to the judicial role is not surprising, as these shared personality traits are associated with success across a wide range of professions. Conscientiousness, however, is also associated with task-orientated leadership and less risk-taking, while honest-humility is associated with fairness and sincerity, prosocial behaviour and ethical leadership.

The similarity in the personality traits that the High Court justices chose to prioritise in their speeches may suggest a shared understanding of what it means to be, and to speak as, a judge of the High Court of Australia. In this way, the swearing-in speeches reflect both similar life experiences within the profession and institutional understandings of judging to which the new justice believes that he or she must conform.

3.2 Personal values and judicial swearing-in speeches

Personal values have been demonstrated to be central to decision-making in a wide variety of contexts (Finegan, Reference Finegan1994; Sagiv and Schwartz, Reference Sagiv and Schwartz1995; Hemingway and Maclagan, Reference Hemingway and Maclagan2004; Piurko et al., Reference Piurko, Schwartz and Davidov2011; Hackett, Reference Hackett2014). Defined as ‘an enduring belief that a specific mode of conduct or end-state is personally or socially preferable to an opposite or converse mode of conduct or end-state existence’ (Rokeach, Reference Rokeach1973), personal values serve as the basis from which attitudes and behaviours are created and are central to identity. This is particularly true of the more cognitively based traits including honest-humility, openness to experience and agreeableness (Parks-Leduc et al., Reference Parks-Leduc, Feldman and Bardi2015). Psychometric studies have also revealed a relationship between values and other facets of personality, including political ideology (Feather, Reference Feather1979), role-orientation (Spini and Doise, Reference Spini and Doise1998) and moral outlook (Schwartz, Reference Schwartz2007).

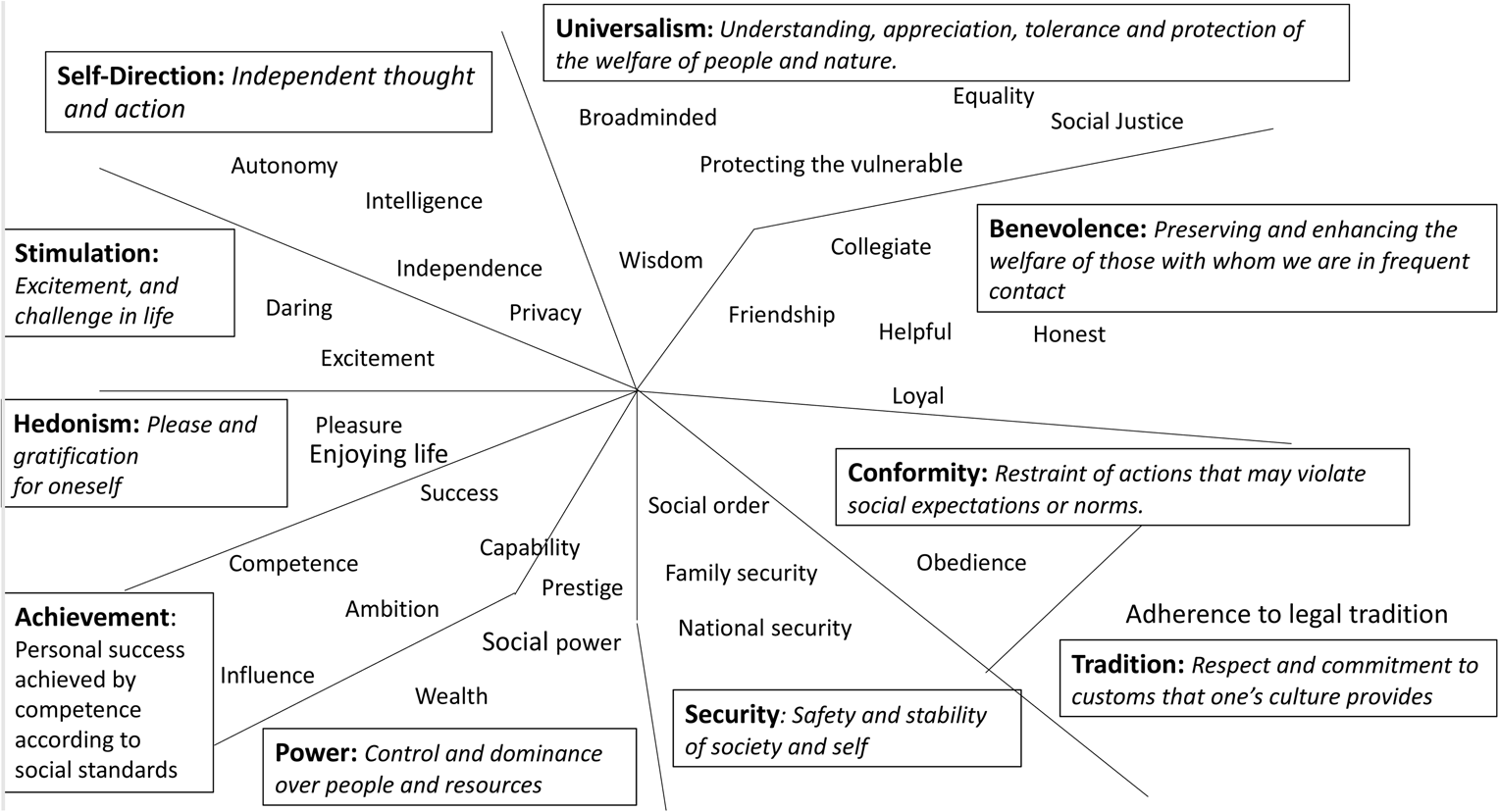

This paper draws on a model of personal values developed by Schwartz (Reference Schwartz1992; Schwartz et al., Reference Schwartz2001; Reference Schwartz2012), who found that highly conserved values could be grouped into ten value types: self-direction, stimulation, hedonism, achievement, power, security, conformity, tradition, benevolence and universalism (Figure 2). Although there is a relationship between extroversion and achievement/stimulation and between conscientiousness and achievement/conformity, values are empirically and conceptually distinct from personality traits and represent a different facet of identity (Roccas, Reference Roccas2002). Each value type is categorised by the motivation that underpins it. For example, the defining goal of self-direction is independent thought and action. In contrast, the defining goal of conformity is the restraint of actions, impulses or inclinations that upset or harm others or violate social norms. Figure 2 represents the ten values and their associated motivations.

Figure 2. A graphic representation of the Schwartz model of values and coding framework. The overarching motivation of the value is presented in the box. The associated segment sets out the values associated with the motivation. This graphic is a modified version of the graphic representation (Schwartz, Reference Schwartz1992; Reference Schwartz2012).

To explore the justices’ values as expressed in the swearing-in speeches, we applied the coding framework and methodology used by Cahill-O'Callaghan (Reference Cahill-O'Callaghan2013; 2019; Reference Cahill-O'Callaghan, Appleby and Lynch2021) in her analysis of the judgments of the UK Supreme Court. Values were coded by associating text with an overarching motivation of a value defined by Schwartz. For example, a justice might affirm security directly by stating: ‘I had the benefit of a very happy and secure childhood’ (Bell, Reference Bell2009). Justices also affirmed a value by referencing the overarching motivation of the value, when Bell endorsed independent thought and personal autonomy, which is associated with self-direction, when stating: ‘Generations of Justices of this Court in their faithful exposition of the common law have ensured that in respect of personal liberties, we do well on this measure of civilisation’ (Bell, Reference Bell2009).

Each speech was systematically coded using this scheme to reveal similarities and differences in value expression.

Table 4 summarises the coding results and illustrates the number of value statements and the dominant values expressed in the speeches. We note that the low number of value statements identified in each speech is consistent with Cahill-O'Callaghan's finding that judgments and extra-curial speeches by UK Supreme Court justices similarly evinced limited numbers of values statements (Cahill-O'Callaghan, Reference Cahill-O'Callaghan2013; Reference Cahill-O'Callaghan2020). Table 4 also demonstrates – by its silence – the values that were absent from the speeches: hedonism, stimulation and security. While the absence of hedonism and stimulation might be expected in a ceremony designed to speak to the institutional values of the judiciary, the values of security can be seen in judicial narratives in other contexts; for example, references to the importance of national security are often identified in judgments of the UK Supreme Court (Cahill-O'Callaghan, Reference Cahill-O'Callaghan2020). The absence from our dataset again may reflect the small dataset and/or the choices made by the justices to prioritise particular themes in their inaugural speeches. Table 4 also demonstrates that the most commonly expressed values in the speeches were tradition, benevolence, universalism and achievement.

Tradition encompasses both affirmations of legal tradition and wider societal traditions. French identified both aspects of tradition in his speech, which contained seven tradition-coded statements. For example, he stated:

‘The history of Australia's indigenous people dwarfs, in its temporal sweep, the history that gave rise to the Constitution under which this Court was created. Our awareness and recognition of that history is becoming, if it has not already become, part of our national identity.’ (French, Reference French Hon.2008)

This passage from French, and our coding of it as tradition, provides an opportunity to explain further our coding framework. Qualitative research is grounded in choices. For example, one reading of the above passage would suggest that it should be coded as universalism, as French reflects upon the inherent value of minority voices and history (that is, Indigenous perspectives and history) within the majoritarian authority structures. Such a coding would, however, rely upon the broader historical context of the Australian legal system, knowledge that Indigenous Australians were an oppressed minority group and that, by his statement, French offered an unusual recognition of the importance of Indigenous Australian history framing Australian identity. Instead, the systematic coding structure utilised in this paper was purposefully designed to maximise intercoder reliability – that is, the capacity for readers to reach identical coding decisions independently of each other and without assumed knowledge of history and context. To generate our coding results in this paper, two researchers independently reviewed the text and these results were then reviewed by a third member of the coding team. The text was coded without context or interpretation and so knowledge of the Australian legal system, or the history and tradition of Australian swearing-in ceremonies and their themes, was not drawn upon. Applying this methodology, the above passage has been coded as tradition because, in its language, it affirms the importance of history.

Humility is also encompassed within the value of tradition and this facet of tradition was also affirmed by French, Kiefel and Hayne. The majority (nine out of twelve) of High Court justices espoused the values encompassed in benevolence and it was one of the dominant values in four of the speeches. Benevolence has the defining goal of preserving and enhancing the welfare of individuals with whom there is frequent personal contact. Benevolence values derive from the basic requirement for smooth group functioning and promotes co-operative and supportive social relations (Kluckhohn, Reference Kluckhohn, Parsons and Shils1951). Justice Kiefel affirmed this value when she referred to the kindness and helpfulness of members of the Bar: ‘The outstanding characteristic of the Bar was as a society, in the support and assistance members gave to each other despite the fact that tomorrow they may be adversaries’ (Kiefel, Reference Kiefel2007).

Justice Kiefel was also more likely than many of the other justices to affirm values encompassed within universalism, which is concerned with the welfare of those in the wider society. Indeed, of the thirteen coded value statements in her swearing-in speech, ten were encompassed within benevolence and universalism. Kiefel's expression of values encompassed within universalism and benevolence centred on her discussion of the protection of ‘trial judges’ – individuals who may be perceived as her in-group (i.e. a social group to which a person psychologically identifies). Justice Kiefel observed:

‘It may be that the time has come to reassess whether one person can continue to undertake some of the cases which have been litigated in recent times… without skilled trial judges the work of appellate courts would be intolerable.’ (Kiefel, Reference Kiefel2007)

Achievement was also the dominant value espoused by six of the twelve High Court justices. The motivational goal of achievement is personal success through demonstrating competence according to social standards. The formalities of the swearing-in ceremonies encourage recognition of achievement and success, and the majority of High Court justices affirmed the achievement of others. Justice Heydon, for example, referenced achievement through his tribute to Mary Gaudron, his predecessor on the bench, and five of his fourteen value-coded statements related to Gaudron. In addition to achievement, Heydon affirmed values encompassed as benevolence including friendship and loyalty (Heydon, Reference Heydon2003).

Notably, although each justice was assuming a position of power, only two justices affirmed the value power in their speeches. Crennan reflected that ‘[J]udicial power … is the final protector of the rights of citizens’ (Crennan, Reference Crennan2005). Through this statement, Crennan also identified the importance of power as a judicial virtue. Justice Heydon was the only other High Court justice to espouse power. He did so when discussing judicial influence (Heydon, Reference Heydon2003).

This analysis of values provides further insight into the individuals who populate the High Court bench. It is unsurprising that values encompassed in tradition and universalism are espoused in speeches. These values are also dominant in legal judgments and reflect central tenets of the legal system: the preservation of and adherence to legal tradition, and the affirmation of equality and protection of the vulnerable (Cahill-O'Callaghan, Reference Cahill-O'Callaghan2020). Although many of the judges espouse both values in their swearing-in speeches, it is notable that tradition was the dominant value expressed by French. It is possible the ceremonial expectations surrounding the speech of an incoming chief justice may have played a part in shaping this value profiles – a hypothesis to examine in a future study of chief justices’ swearing-in speeches.

Our analysis suggests, however, that there is not a clear relationship between the values expressed by the justices in their swearing-in speeches and key demographic identifiers. As Table 4 illustrates, for example, gender was not determinative of the values represented in the speeches, nor was geographic background. Justices who shared common values, such as the justices affirming tradition, represented different genders, geographic origins and educational backgrounds. The only tenuous relationship identified was that with the appointing government – a variable evinced by the identity of the Attorney General speaking at the ceremony and known to the audience but silent throughout all speeches. The value pattern expressed in one instance: the two judges to prioritise power – Crennan and Heydon – were both appointed by Conservative governments. Although the focus of this study was not on appointments, nor the political nature of these appointments, this finding warrants further investigation.

4 Conclusion

This paper starts with the advocation that who the judge is matters. Yet, very little is known about those who populate the High Court bench and the process of appointment that places them there. Like many common-law jurisdictions, the process of appointment to the highest court in Australia is not transparent and swearing-in speeches are the first opportunity to hear from the newly appointed judges. The characteristics that these individuals choose to amplify on this occasion reflect both the individual and the process that appointed them. This paper draws on the content of swearing-in speeches to gain fresh insights into the individuals who populate the bench. In doing so, it highlights the broader facets of diversity that are prioritised within Australia's appointments process.

It has long been recognised that the public biographies of High Court judges are incomplete. The analysis of the swearing-in speeches in this paper fills some of these gaps regarding demographic information, but also draws attention to continuing omissions. These inclusions and omissions in part reflect the culture in which the appointments were made and the characteristics of judges that are perceived as acceptable in this process. Historically ingrained silence around homosexuality, social niceties around discussions of age and class, and culturally scripted tensions between parenthood and public power all play a part in what is privileged and silenced in the ceremonial narratives (Roberts, Reference Roberts2014; Moran, Reference Moran, Schultz and Shaw2013). In this context, it is not surprising that calls for greater transparency in the High Court appointments process continue to be made (Lynch, Reference Lynch2020).

The analysis of personality traits espoused by the judges themselves in their speeches begins to explore another facet of judicial identity. Two personality traits, namely conscientiousness and honest-humility, are notable for their recurrence in our study. Within the range of personality traits, it is interesting that it is these two traits that are prioritised within the swearing-in speeches. These traits are associated both with success and with characteristics valued by the legal system, including fairness and impartiality. The consistency we have observed in the personality traits across the French Court swearing-in speeches may be a consequence of two distinct influences or a combination thereof: first, it may be that on this occasion the justices want to affirm traditional institutional norms; or, second, it may be that these personality traits of justices are prioritised by the appointment process, and by particular appointing governments, and thus dominate the judiciary.

The value analysis also starts to reveal a further component of judicial identity. The analysis of values starts to present shared value priorities. Values encompassed within tradition, universalism, benevolence and achievement dominate the speeches. It is notable that the expression of these values by individuals varied. French affirmed the values encompassed within tradition; in contrast, the values encompassed within universalism were espoused by Bell and Keane. As we have noted in this paper, our analysis relies upon a very small dataset of swearing-in speeches and accordingly the qualitative-coding decisions in each speech may have a significant impact. As a result, we recognise the need to be tentative in the conclusions that can be drawn from our qualitative coding. Further, we recognise that a single speech, in a highly formalised situation, should not be taken as sufficient evidence to suggest a difference in individual value priorities. However, the difference that we have observed in this study does warrant further investigation.

The three methods brought together in this paper highlight how the use of different frames of analysis can present layered insights into the multiple dimensions of individual judicial identity. The analysis reveals shared life experiences, as well as shared facets of judicial personality and values. These are new insights, using methods not previously employed when examining judicial diversity on the Australian bench. They provide promising lenses through which to explore a richer and more nuanced understanding of judicial diversity. Our study demonstrates that swearing-in speeches can be analysed to shed light on personality traits and values, and how the shared experience of the ceremonial ritual can illuminate similarity and difference between the justices that are not generally considered. Approached through these new methods, swearing-in speeches present insights into the diversity of the justices of the High Court and the qualities that are reinforced through the appointments processes that place them there. These facets of diversity should continue to be explored as we seek greater understanding of judicial identity and how judicial diversity can be achieved in our highest courts.

Conflicts of Interest

None

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers and Professors Gabrielle Appleby and Sharon Roach Anleu for their constructive comments on early drafts of this paper. Dr Rachel Cahill-O'Callaghan was supported by a Cardiff Research Leave award and an ANU Visiting Fellowship. Dr Heather Roberts is supported by an Australian Research Council DECRA Fellowship (DE 180101594).