Most lawyers and judges thought it would be an easy choice. When the 9/11 victims and those who lost family members in the attacks were offered an alternative to complex, uncertain, multiyear litigation—a fast, guaranteed payment from the September 11 Victim Compensation Fund (VCF) comparable to what they might receive if they won in court—most expected them to accept the offer in droves. And while accept they did—fewer than 100 lawsuits were ultimately filed, while the VCF paid out some 5,500 claims with an average of $1.2 million each ($2 million for the people who lost a family member, $300,000 for the injured)—lawyers and judges were puzzled by one thing: nearly half the claims were filed in the last month of the two years the Fund was open for claims. Why did the families and victims delay so long in making what seemed like such a clear choice between cash and a trip to the courthouse? As Ken Feinberg, who served as Special Master for the VCF, put it: “[w]hy would a spouse, mother, father, or child choose not to complete an application form that would bring them a tax-free $2 million?” (Reference FeinbergFeinberg 2005:158).

Feinberg's interpretation of the perplexing delay (2005:159–60) speaks to an equation of litigation interests with monetary interests that is increasingly common in the legal profession. Feinberg explains the delay in terms of factors that might interfere with the rational calculus of settlement amounts: people were still traumatized by their loss; some were stalling in the hope that they would receive a higher amount, or at least a predetermined amount,Footnote 1 before waiving their right to pursue a lawsuit. “Unaccountable stragglers” were understood to be incapacitated or in denial. Feinberg saw the choice in the expected value terms that are standard in legal scholarship and widely used in the economic analysis of litigation (Reference Cooter and RubinfeldCooter & Rubinfeld 1989): the choice was, as Feinberg saw it, “a classic trade-off between administrative speed and efficiency and rolling the dice in court and going for the proverbial pot of gold” (Reference Henriques and BarstowHenriques & Barstow 2001: n.p.).

Similarly, most legal academic studies of the VCF evidence the focus on monetary interests found throughout the legal profession. A major study conducted by the RAND Institute on Civil Justice (Reference Dixon and SternDixon & Stern 2004), for example, presents a detailed assessment of the extent to which the amounts calculated by the VCF methodology accurately captured the dollar value of the losses associated with injury or death. Other studies (see, e.g., Reference LandsmanLandsman 2003; Reference PriestPriest 2003; Reference AlexanderAlexander 2003; Reference RabinRabin 2003; Reference ShapoShapo 2005; Reference ChamallasChamallas 2003; Reference CulhaneCulhane 2003; Reference MullenixMullenix 2004; Reference AckermanAckerman 2005) have also largely focused on the amounts awarded by the VCF as the criterion for assessing the fairness or success of the Fund as an alternative to tort litigation. Studies that focus on the process values associated with the Fund (Reference SchneiderSchneider 2003; Reference Tyler and ThorisdottirTyler & Thorisdottir 2003) largely address the procedures for determining the amounts awarded. Reference HenslerHensler (2003:427–31), although she discusses the nonmonetary goals potential plaintiffs might have had, including accountability, analyzes how commentators on the Fund's proposed regulations evaluated the distributive justice of the dollar amounts awarded.

The existing legal professional and academic analysis of the VCF thus presumes the answer to a question that law and society scholars have long seen as central and problematic: how do people (other than lawyers and legal scholars) frame a “legal” problem and the decision about whether to take legal action in response to the troubles they encounter? Beginning with the legal needs (Reference Mayhew and ReissMayhew & Reiss 1969; Reference CurranCurran 1977; Reference BaumgartnerBaumgartner 1985; Reference Genn, Zuckerman and CranstonGenn 1995) and dispute processing (Reference TrubekTrubek et al. 1983; Reference Miller and SaratMiller & Sarat 1980–81; Reference Mather and YngvessonMather & Yngvesson 1980–81) literatures, empirical scholars have looked at when and how people translate the difficulties they encounter in their everyday lives into legal categories and contacts. Reference FelstinerFelstiner and colleagues (1980–81) emphasize the process by which individuals transform their problems into legally cognizable disputes: first recognizing a problem as an injury (“naming”), then as a grievance with a person or entity seen as responsible for the injury (“blaming”), and ultimately articulating the grievance and seeking a remedy (“claiming”). Building on the recognition that this process is socially mediated not only by material factors but also by how law is understood and experienced (Reference MerryMerry 1986), the legal consciousness literature (see Reference SilbeySilbey 2005 for a review) explores how people understand the function and meaning of law and in particular the significance of transforming a private dispute into one that calls upon the public institutions of law such as courts, police, and lawyers. Against the backdrop of this literature, it is clearly inadequate to simply assume that the decision those injured or bereaved by the September 11 attacks had to make between accepting a cash payment from the VCF and entering the legal system by filing a lawsuit was a simple monetary calculation.

In this article, I present the results of a study of the VCF potential claimants intended to unpack the decision the claimants had to make between taking money from the Fund and going to court. Did they, like legal analysts and most lawyers, see the choice facing them as a question of comparing values, payout times, and probabilities, choosing between a sure thing and a lottery ticket? If not, how did they frame the choice between a payout from the Fund and going to court? Their answers demonstrate that for many potential claimants, the choice between accepting a payment from the Fund and going to court was not exclusively, or even primarily, framed as a financial calculation. It involved not an easy trade-off between a guaranteed dollar payment and a gamble on a “pot of gold,” but a deeply troubling trade-off between money and a host of nonmonetary values that respondents thought they might obtain from litigation. These values included information from otherwise inaccessible sources (the decision makers who determined airline and World Trade Center fire safety procedures, for example), accountability in the sense of public judgment about whether those on whom victims depended for their safety did their jobs, and responsive policy change—making sure that lessons were learned and heeded in the future.

Unlike most studies in the legal consciousness or dispute processing literature, this study did not focus on the everyday interpersonal difficulties that ordinary people encounter and ask what prompted them to decide that a “personal” problem—as the reluctance to “legalize” an issue (Reference FelstinerFelstiner et al. 1980–81; Reference Merry and SilbeyMerry & Silbey 1984) indicates many problems are perceived—should be transformed into an issue demanding the attention of public officials. The harms suffered by the respondents in this study clearly implicated public concerns and indeed, as the creation of the VCF indicated, the legal treatment of these harms were uniquely framed by public officials as a matter of public interest. The legal meaning of their circumstances was not the result of transformation within their personal frameworks for understanding law but rather was presented fully fashioned to them by public officials. The issue these potential plaintiffs thus pointedly faced was whether to resist the public characterization of their legal interests as private and monetary and to enter the public legal realm despite being strongly discouraged by public officials to do so. What emerges from this study is thus a distinctive perspective on courts and litigation that has by and large not been explored in the existing literature. The transformation challenge these litigants faced may be better characterized not as naming, blaming, and claiming but rather as naming, blaming, and framing.

Most strikingly, respondents in this study framed a decision to litigate not in terms of the pursuit of private ends within or against an external legal order (Reference Ewick and SilbeyEwick & Silbey 1998) but rather in terms of citizenship and community. Undoubtedly the national drama of September 11 heightened these elements in people's perceptions of the legal system, but as Reference Merry and SilbeyMerry and Silbey (1984) observe in less-dramatic settings, decisions about litigation may be routinely driven by “norms about integrity, self-image, self-respect and duty to others” (Reference Merry and SilbeyMerry & Silbey 1984:160). Important to note, Merry and Silbey's observations arose from their investigation of the question of why people, contrary to the expectations of the alternative dispute resolution (ADR) movement, show little interest in ADR once they have transformed a grievance into a dispute requiring third-party intervention. Similarly, in this article, I am looking at how people with potential legal claims responded to a sharply focused ADR effort to divert them out of litigation. Like Merry and Silbey (see also Reference Relis, Sarat and EwickRelis 2002; Reference Genn, Zuckerman and CranstonGenn 1995), I find that litigation represents more to some potential litigants than a means to satisfying private material ends; it represents principled participation in a process that is constitutive of a community.

The second section sets out briefly some background about the VCF. The third section briefly explains the data collection process and reports on the characteristics of the sample studied. In the fourth section, I present both quantitative and qualitative results from the study, looking at the questions of how respondents thought about who was responsible for their losses (and who was thus a potential defendant), the factors they took into account in framing the choice they had to make between the Fund and litigation, and what those who filed with the Fund (the vast majority of potential claimants) felt they were giving up when they abandoned the option of litigation. Here I identify three themes in the way respondents thought about what litigation might give them: the opportunity to obtain information, force accountability, and prompt responsive change through litigation. The fifth section then draws out the idea that many respondents saw participation in litigation as an act of citizenship. The final section offers concluding remarks.

The Victim Compensation Fund

The VCF was created in the swirl of lawmaking that followed in the weeks after the September 11th attacks. On September 21, 2001, Congress debated and passed the Air Transportation Safety and System Stabilization Act(ATSSSA).Footnote 2 The act initially was perceived as an essential, emergency, response to the threat that airline carriers, initially grounded for safety reasons, would stay on the ground indefinitely because their insurers would refuse to continue their coverage and capital markets would refuse to provide funds to the airlines in the face of potentially “unlimited” liability.Footnote 3

The ATSSSA took several steps to address the financial risks facing the airlines, including limiting the liability of air carriers for all claims arising from the attacks to the limits of the insurance maintained by the air carrier ($1.5 billion per plane.) Ultimately, the rationale behind the act clearly went beyond protection for the airlines. Amendments in November 2001 extended the limitation of liability to those engaged in airline security, aircraft and aircraft parts manufacturers, airport owners and operators, anyone with a property interest in the World Trade Center, and New York City.

The limitations on liability in the ATSSSA created the potential that in the event entities were judged to have been negligent and to have contributed to the losses experienced by individuals, corporations, and property owners on September 11, there would not be sufficient funds available to pay all compensatory damages awarded by the courts. Ostensibly to address this, Congress created the VCF as a source of compensation for those physically injured by, or who lost family members in, the attacks. But it conditioned that compensation on a waiver of all rights to bring any claims for damages—against anyone, not merely those entities for which liability had been limited.

The ATSSSA provided few details for how the VCF was to operate. It specified that compensation was to be provided for both economic and noneconomic losses, and it prohibited any awards based on an assessment of punitive damages. It specified that only one claim could be made on behalf of any person killed or injured in the attacks, that claims had to be filed within two years of the date on which the Fund's Special Master issued regulations governing the Fund, that the Special Master had to determine an award within 120 days of the filing of a claim, and that there was to be no judicial review of the Special Master's determination of an award. No limits were otherwise placed on the amount that could be awarded, either individually or in the aggregate. Important to note, the VCF limited compensation—and the corresponding waiver of civil claims—to individuals who suffered physical injury or wrongful death. There was no effort to divert corporate claims for property damage, business disruption, or insurance subrogation claims out of the legal system.

Special Master Feinberg established several procedures for streamlining and simplifying the process of determining awards, which, under the ATSSSA, were to be determined based on the “individual circumstances of the claimant.” Feinberg developed a grid of presumed economic loss for decedents based on lost earnings or economic opportunities, age, number of dependents, and marital status. He also established a rule that noneconomic losses would be presumed to be $250,000 plus $100,000 per spouse and each dependent. No presumptions were made about losses suffered by those filing claims for physical injuries.

Ultimately, 97 percent of those eligible to file a claim on behalf of those killed in the attacks did so, a total of 2,880 claims (Reference FeinbergFeinberg 2004:1). Another 2,680 people filed claims for injuries sustained in the attacks. Total entitlement was calculated at $8.5 billion for death claims and $1.5 billion for injury claims; offsets (required by the act) for insurance payments reduced the total amount distributed by the VCF to $6.0 billion and $1 billion, respectively (Reference FeinbergFeinberg 2004:10). Total administrative costs for the Fund were $87 million (Reference FeinbergFeinberg 2004:114), the great bulk of which ($77 million) went to PriceWaterhouseCoopers, the firm selected to manage the claims processing and payment procedures (Reference FeinbergFeinberg 2004:75). The Special Master's office, which estimated it spent in excess of 19,000 hours valued at more than $7.2 million, provided all services free of charge (Reference FeinbergFeinberg 2004:114).

Data Collection and Sample Characteristics

This study began with a simple question: how did people who had suffered an injury or lost a family member think about the choice between collecting money from the VCF and pursuing civil litigation? I investigated this question in three ways. First, I conducted open-ended interviews in early 2004 with four individuals who had been publicly involved in efforts to reform the VCF or shape the public response to 9/11. Second, I constructed an online survey that consisted of both closed- and open-ended items. Respondents were recruited via an e-mail—distributed on my behalf by individuals (themselves people who had lost a family member) who maintained listservs providing information about 9/11 issues for people who had been injured or lost a family member. This e-mail was also distributed via these listservs to several 9/11 support organizations who then forwarded it on to their members. Survey responses were collected between October 2005 and June 2006. The survey could be completed anonymously. Respondents were, however, given an option to provide me with an e-mail address or phone number if they were willing to be contacted for a follow-up interview. Interviews averaged 30 minutes in length. These follow-up interviews, conducted in May and June 2006, constituted my third source of data.

After removing duplicates, there were a total of 155 useable survey responses. Of the 155 who completed the survey, 67 respondents provided a phone number or e-mail address, indicating they were willing to be interviewed. Of these 67, interviews were arranged and completed with 30. For purposes of reporting interview results, I have combined the 30 post-survey interviews with the four pre-survey interviews I conducted.

Because of the recruitment method for this online survey—which was selected in order to protect the privacy of 9/11 victims and their families and to ensure that any request to participate came from another family member and not from a researcher directly—it is not possible to determine what percentage this response level represents of those who may have seen the recruitment e-mail. I did not have direct access to the e-mail addresses of potential respondents in order to draw the survey sample and employ conventional survey methods that would have enabled me to report a response rate. The distributors of the listservs that relayed my recruitment e-mail were believed by their organizers to reach several thousand 9/11 victims and family members; the e-mail was in particular posted on a listserv that the family member managing the listserv indicated was the largest one in operation. While some lists were devoted to specific issues—such as support groups, financial help, burial and memorial planning, skyscraper safety, immigration and border security, the 9/11 Commission, and VCF information—the principal listservs relied upon were, to my understanding, general purpose lists that forwarded information on any and all topics of interest to those affected by 9/11. The recruitment e-mail should, therefore, have reached a large and, with the exception of factors influencing Internet access and participation in listservs, fairly representative segment of the total population of those who could have made VCF claims. Ultimately, however, the representativeness of the total pool to which the survey was distributed can only be seen through the window provided by the sample that ultimately responded.

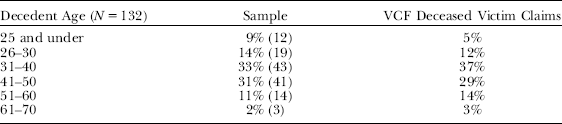

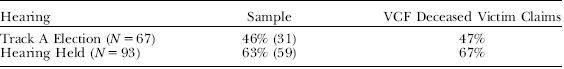

As detailed in the Appendix, the sample appears to be reasonably representative with respect to the nature of the claim (death or injury); age, gender, location, and rescue-worker status of victims; amounts paid out by the VCF; and preferences among claimants for hearings. It appears to somewhat overrepresent wealthier VCF claimants (perhaps reflecting differential Internet access and use): 38 percent of VCF claims were for individuals who earned more than $100,000 a year; 49 percent of survey respondents reported decedent income of over $100,000. Respondents report political beliefs at the time of the survey comparable to the general population (National Opinion Research Center 2006), with a median of 5.5 on a scale of 1 (extremely liberal) to 10 (extremely conservative). The sample also evidences substantial representation of both activists and nonactivists. Approximately 60 percent had engaged in efforts to organize meetings, publicize their views, lobby Congress, etc., with respect to the country's response to 9/11 generally or the VCF in particular. While this is high relative to the general population (Natoinal Opinion Research Center [2006] reports that approximately 30 percent of Americans have engaged in lobbying or efforts to influence the votes of others), it may not be high relative to the unique population of people at the epicenter of this major political debate.

With respect to the specific questions the survey explored about how respondents evaluated the VCF relative to civil litigation alternatives, it is not possible to say whether the sample is representative. Respondents were recruited to “share [their] experiences with the VCF and the legal system after the losses [they] suffered on September 11.” This recruitment may have selected for people who were more concerned about the VCF and its design, particularly the waiver of legal rights, although it does not appear to have overrepresented those who felt that the payment they received from the VCF was less than expected (30 percent reported the amount was as expected, and 20 percent reported it was higher than expected). A small preponderance felt the procedures were unfair or very unfair (59 percent).

Although it is fair to conclude that the sample is not idiosyncratic, whether the sample is fully representative of the population of those eligible to file a claim with the VCF is not determinative of the relevance of my findings. My goal is, first, to provide quantitative and qualitative evidence that interests beyond monetary interests exist in at least a meaningful subgroup of those who contemplate whether to accept money not to pursue litigation—those who were sufficiently focused on 9/11 and the VCF four years after the attacks to take the time to share their views with a researcher. Even if this subgroup is unusually motivated or oriented to the nonmonetary interest in litigation, it is clear that the group is not idiosyncratic on many demographic criteria and, moreover, that the motivations of this subgroup play a unique role in the vibrancy of political institutions much like the one played by the subgroup members who choose to become active in community groups or other forms of political action. Second, I hope to provide, particularly through the narrative evidence, greater insight to support our theorizing about the function of courts and to demonstrate the failure of the heavy focus on monetary considerations and the instrumental functions of courts to capture what is potentially at stake in litigation and access to courts.

Choosing Between the Fund and the Courts: Experiences of VCF Claimants Blaming

Why are we here? It was the terrorists who did this.

(statement attributed to then-Mayor Rudolph Giuliani by a survey respondent)

Seen through the lens of the naming-blaming-claiming framework (Reference FelstinerFelstiner et al. 1980–81), it seems clear that those injured or bereaved on September 11, 2001, had no difficulty recognizing (naming) their losses. It was far more complex to determine whom could they blame. To many, it makes no sense to extend blame for the devastation wrought by September 11 beyond the terrorists who financed and piloted the planes that slammed into the World Trade Center, the Pentagon, and a field in Pennsylvania. Indeed, there is something perhaps dangerous in doing so—shifting attention from the criminality of foreign terrorists to the shortcomings and missteps of our own people, failing to recognize that the attacks were directed at the American people as a whole, and undermining our commonality. Senator John McCain, arguing in favor of passage of the ATSSSA, spoke of the risk that “the unity that this terrorist attack has wrought will devolve in the courts to massive legal wrangling and assignment of blame among our corporate citizens” (147 Cong. Rec. S9589-01, 2001 WL 1703925). The Trial Lawyers Association characterized lawsuits as “finger-pointing among our own people,” inappropriate at a time when “we must enter a period of national unity … [when] we, as a nation, must speak with a single voice” (Reference PeckPeck 2003:215). The 9/11 Commission Report disavowed at the outset any assignment of individual blame among Americans and set the context of its study of the events that led to the attacks as a continuation of a unified response to a hostile enemy: “That September day, we came together as a nation. The test before us is to sustain that unity of purpose and meet the challenges now confronting us” (National Commission Upon Terrorist Attacks on the U.S. 2004: xiv).

Some survey respondents did indeed share the view (which I believe to be widespread in the general public) that the terrorists, and the terrorists alone, bore responsibility for the attacks, making litigation an illegitimate blame-shifting exercise (and, in the opinion of some respondents as well as a large share of the general public, the VCF an inappropriate response to the attacks):

I didn't think it was appropriate to sue. It was an act of violence and terror. It was not appropriate to blame this on others.

There is no reason to blame anyone or entity other than the terrorists who engaged in this mass murder …. It is important that I state my total opposition to the Victim Compensation Fund. As tragic as the losses are, I do not believe it proper for the government to buy off the victims' legal next of kin. This was a tragic event but not one that the taxpayers of the country should be responsible for …. Further, I do not think there should be a litigious approach to every event that occurs.

Even those who stated that they did not believe there was anyone else to blame struggled with that view, however. One father who lost his son in the World Trade Center—and who was in the towers himself at the time of both the September 11 attacks and the 1993 bombing—spoke about the complexity of the issue of responsibility:

We didn't see fault beyond the terrorists. The Port Authority, the City, the Airlines—they were in a criminal situation, it was unpredictable. Maybe I didn't want to think anyone else was responsible. It hurts more than thinking it was just terrorists that were responsible.

But while the view that the terrorists alone were responsible for the attacks was evident in the sample, it was a minority view. The majority of respondents allocated significant responsibility to people and entities other than the terrorists. The survey investigated this issue using a novel survey item developed for this study. I asked respondents to allocate 100 points among 14 people and entities based on their perception of who shared responsibility for the losses they suffered. This survey item was chosen over alternative approaches to determine the relative importance of different factors such as a Likert scale (ranging, for example, from “no responsibility” to “complete responsibility”) in order to require respondents to engage in relative valuation of the role played by different people or entities and to allow comparison across respondents. The list of 14 possible responsible entities or people was generated from open-ended interviewing of individuals who were injured or lost a family member on 9/11. The instructions for the survey item were as follows:

Who do you feel shares responsibility for the loss you suffered? Please rate the following by dividing up 100 points among those you feel are responsible based on the share of responsibility you think they bear. Enter a zero for anyone you think is not responsible at all. For example, if you think four people or entities share responsibility, you might give the first 40 points, the second and third 25 points and the last 10 points. You can divide up the points in any way you want but your total points must add to 100.

The requirement that totals add to 100 was enforced by the online survey mechanism. Respondents were also given an opportunity in an open-ended item that followed this item to identify any other entities or people they felt bore responsibility that were not included in this list and to indicate how many points they would have given this response if it was available.

There is some risk that presenting respondents with a long list of those potentially responsible could bias responses by leading people to attribute fault to every entity or person on the list, even if they would not have volunteered these entities or people in response to an open-ended question. I attempted to diminish the risk of biasing responses in this way by placing this question near the end of the survey, after respondents had answered many questions about the VCF-litigation tradeoff and thus had already reflected on what litigation (and hence the defendant pool) might have looked like for them. A review of the responses (see Table 1) indicates that respondents indeed had little difficulty selecting from this list a significantly smaller list of those whom they felt shared responsibility for their losses: many answers were given a zero weighting by significant percentages of respondents. In addition, although the ordering of possibly responsible entities was not randomized, there was no significant rank correlation between the ordering presented and the mean weighting respondents assigned.Footnote 4 This suggests that responses were not biased by the order in which answers were presented. There is also evidence that this item had good internal reliability: in a later item (see Table 5 later in article) I asked respondents whether they felt it was appropriate to limit the liability of various entities, including some of those appearing in the “who bears responsibility” item. The rank ordering of the frequency with which respondents indicated that it was inappropriate to limit liability was perfectly correlated with the mean share of responsibility accorded each of the entities in the “who bears responsibility” item. This suggests that respondents, in the aggregate at least, were adjusting their allocation of responsibility points in line with their sense of how important it was to attribute responsibility in a legal sense (liability). Finally, this item asked respondents to perform an evaluation that is standard for juries called upon to allocate fault in a tort case involving multiple defendants. In that setting, the jury's determination is treated as a reliable indicator of the relative share of damages a defendant should bear. While more extensive testing of the reliability and validity of this item would be necessary for more careful statistics, for my purposes, which are largely descriptive and interpretive, the item (and similar items I report on) appears to be a useful tool for understanding how respondents thought about blame.

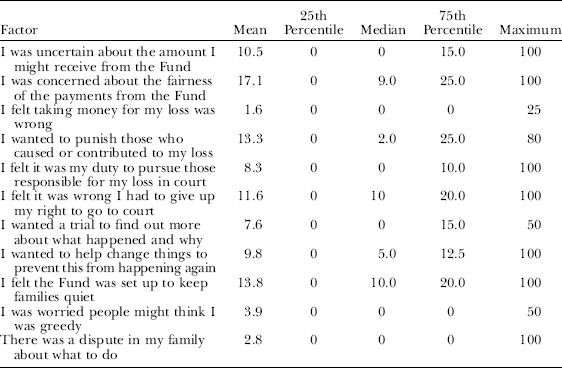

Table 1. Share of Responsibility for Losses (N=113)

Table 1 reports the mean and twenty-fifth, fiftieth, and seventy-fifth percentile scores for each of the possibly responsible people or entities. The results tell several stories. First, most strikingly, the average share of responsibility allocated to the terrorists is barely greater than a third. The distribution of responses indicates that this is not the result of highly skewed evaluations. Fifty percent of respondents assigned 30 points or less to the terrorists; only 25 percent felt the terrorists bore more than half of the responsibility for the attacks, that is, more than U.S. entities and officials. Interestingly, this is roughly the same share of responsibility—one-third—ultimately attributed to the terrorists who bombed the World Trade Center in 1993 by the jury that held the Port Authority (which owned and managed the World Trade Center) two-thirds liable for failing to take steps to prevent the attack.

Second, Table 1 indicates that there was substantial agreement among respondents that airline security firms, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), the intelligence agencies, and the Immigration and Naturalization Service bore significant responsibility for the injuries by not “doing their job” to prevent such attacks. Many respondents expressed this view in their narrative answers:

Our government let us down. The terrorists were doing their job. It's our own country that wasn't doing their job … what about the aviation schools? It could have stopped right there!

It is similar to the question of who is responsible for a shooting, the gunmaker or person who pulled the trigger? Clearly the terrorists are responsible, but the airlines enabled them by focusing on the bottom line rather than security.

The relatively broad support for the claim that security firms and intelligence agencies bore a significant share of responsibility for the losses suffered on September 11 (reflected in the higher mean share and the comparability of the mean and the median in Table 1) reflects the fact that the events that led to the death or injury of those harmed by the attacks on September 11 began in a common sequence. Every one of those deaths or injuries began with the sequence of events investigated by the 9/11 Commission: the al Qaeda planning and financing of the attacks, the U.S.-based flight training of the hijackers, the immigration and intelligence procedures that allowed the hijackers into the country, the airport security procedures that allowed the hijackers onto the planes, the airline security protocols that allowed the hijackers into the cockpits, the FAA responses that failed to detect or intercept the hijackings until the planes crashed. For those killed on the planes or at the point of impact, the sequence ends there. But many who ultimately died in the World Trade Center or the Pentagon survived the initial impacts. For these victims and for the injured, the cause of injury or death depends on where the victim was at the time of impact and what happened after impact. And for these victims, the answer to the question of who bears responsibility for the loss extends beyond the terrorists and those who bore responsibility for preventing the terrorists from succeeding in their plan. In a form of analysis that is commonplace to tort law, the answer extends to those whose actions entered the chain of proximate cause. For individual victims, this chain of events diverged, removing them from the common chain of events that led to the attacks.

I was struck repeatedly during interviews with the family members of those killed by the detailed reconstruction of how individual deaths occurred. These reconstructions show care and specificity in how most respondents thought through the issue of who was responsible for the particular harm they suffered. A woman whose husband worked in the second tower on one of the floors above the impact zone, for example, spoke of how her husband (to whom she spoke following the impact) spent his last 45 minutes trying to reach the roof for a rooftop evacuation, not knowing that the doors to the rooftop were kept locked and there was no provision for rooftop rescue in the event of a fire. In her mind, had her husband been told of the procedures for evacuation in the event of a fire, he could have attempted a descent, as there was still one stairwell open; others took that route and survived. A mother of a firefighter recounted how her son died because he failed to get the order to evacuate the second tower: his Motorola radio did not work inside the building, a fact known since the 1993 bombing of the towers. The narrative responses provide clear evidence that the process of thinking through the question of who was to blame was informed by the unique circumstances of each death or injury.

She was within 10 feet of the wing. She was dead within three-tenths of a second. I'm a pilot; I did the calculations.

My husband's company told him to stay on the job …. He worked in technology. They had a disaster plan for the data, procedures for going offsite to back up files. They were instructed to stay to figure out what to do with data. My husband was told to stay to discuss the recovery plan.

He was in the first tower, in Windows on the World. Others in the second tower, the Port Authority should have told them to evacuate. But he had no chance—there is nothing that anyone could have done.

My husband called 911. I think 911 operators are wonderful, but the 911 operator told people to go up to the roof. Giuliani knew that was not an option that day. Giuliani asked for helicopters to go to the roof but the Fire Chief knew that was not possible.

As it happened, my father was right next to the last survivor of WTC [name omitted], both before and after the North tower collapsed. She could hear him for a good hour after the collapse.

In each of these stories is a different understanding of what might have gone differently. For those at the point of impact, all that could have gone differently was for the attacks, which affected everyone in the country, not to occur in the first place. But for those who survived the impact, many things might have gone differently and individual deaths and injuries would have required sometimes individually different counterfactuals. Different radios might have been issued to firefighters; better fireproofing might have been installed in the towers; rooftop evacuation procedures for people above a fire could have been developed; 911 operators could have been instructed to advise people to descend if possible; public address announcements and company executives could have told people to evacuate rather than to remain in the building. These individual stories imply, understandably, different beliefs among those who suffered losses about who bears responsibility for the deaths and injuries on 9/11.

Framing

This is a classic trade-off between administrative speed and efficiency and rolling the dice in court and going for the proverbial pot of gold.

(Ken Feinberg, as reported in “A Nation Challenged: Compensation: Victims' Fund Likely to Pay Average of $1.6 Million,”New York Times, 21 Dec. 2001)

In the naming-blaming-claiming framework of Reference FelstinerFelstiner and colleagues (1980–81), having identified their losses and assigned responsibility for them, potential 9/11 litigants would be expected to face a decision about whether or not to transform the injury into a claim, to “voice [the grievance] to the person or entity believed to be responsible and ask for a remedy” (1980:635). This is the stage in the transformation of injuries into disputes that has attracted the attention of legal consciousness theorists (see Reference SilbeySilbey 2005), who study the process of determining not just to voice a grievance but to specifically frame a grievance as one that is properly brought under the rubric of “law.” What does it mean to say that a grievance is one that the law should, or must, address?

It is this framing that is illuminated sharply by the choice the 9/11 victims and families faced when they were required by the waiver provisions of the VCF to choose between accepting a cash payment and filing a lawsuit. Unlike the ordinary everyday troubles that have been studied by the legal consciousness literature, where the framing challenge often requires a shift from seeing a grievance as a purely personal matter to something that is appropriately brought to the attention of public officials, there was nothing ordinary or everyday about the suffering caused by the 9/11 attacks. And rather than being seen as an effort to make a private affair a public concern, a decision to pursue litigation was characterized by many in the public domain as an inappropriate personalizing of what was a national tragedy, shared by all. Conservative commentator Ann Coulter, for example, was a particularly hostile critic of the 9/11 families and specifically the “Jersey girls” who played a visible role as activists in demanding the creation of the 9/11 Commission and criticizing the VCF: according to Coulter, these “self-obsessed women”“weren't interested in national honor, they were interested in a lawsuit” and in “getting their payments jacked up”; they “seemed genuinely unaware that 9/11 was an attack on our nation and acted as if the terrorist attacks happened only to them” (Reference CoulterCoulter 2006:103).

The 9/11 victims and families were presented, only weeks after the attacks, with a prepackaged legal context for their losses: the creation of the VCF and an overt framing of a litigation option as an essentially financial matter for which a check could substitute. Ken Feinberg, the lead spokesperson in this regard, essentially took it as his mission to persuade as many people facing this decision as possible that what was at stake was a financial calculation, weighing a certain payment today against a gamble on a later “pot of gold.”“I remain convinced that they made a mistake in choosing not to join the fund. As a lawyer, I consider their chance of winning their lawsuits quite slim” (Reference FeinbergFeinberg 2005:165). In purely economic terms, it was certainly true that the expected present value of damages that might actually be collected in a lawsuit were not clearly any greater than the amounts offered by the Fund and, framed as a financial decision, the choice was clear.

In light of this overt public framing of respondents' losses as a legal matter for which money was a good, and appropriate, substitute, how did they in fact understand the meaning of transforming blame into legal action? I investigated this with a combination of quantitative survey items and qualitative open-ended survey items and interview questions.

Choosing Law, Foregoing Money

Perhaps largely in response to the dogged and sincere efforts of Special Master Feinberg, only 100 of the thousands of potential plaintiffs ultimately filed a lawsuit rather than entering the VCF. My sample included 10 of these plaintiffs, too small a number to analyze statistically. These respondents, however, were highly articulate about the role money played in how they understood what it meant to see their claim as one that warranted legal action. The survey asked these respondents to allocate 100 points across a set of potential factors in their decision to litigate; none put any weight on the potential for obtaining a higher payout from the court than from the Fund. The factors these respondents did identify as contributing to their decision included: “I felt taking money from the Fund for my loss was wrong,”“I wanted to punish those who caused or contributed to my loss,”“I felt it was my duty to pursue those responsible for my loss in court,”“I wanted a trial to find out more about what happened and whether people had failed to do their job to keep us safe,” and “I wanted to help change things to prevent this from happening again.”

It is probable that there are some, not in my sample, for whom the choice to litigate was influenced by the potential for a higher payout from court or a settlement; when I spoke with attorneys representing some of the plaintiffs, they indicated that this was the case, although plaintiff attorneys, like others in the legal system, are likely to see financial considerations as primary and are not necessarily reliable reporters of their clients' motivations (Reference RelisRelis 2007). Some respondents in this sample also indicated that they thought there were litigants who were motivated by the potential for a higher payment from litigation. One can certainly be cynical about the disavowal of financial motive. But to do so requires significant work to discount the thoughtful articulation of nonfinancial values by these respondents, evident from their narrative responses.

In open-ended survey responses, litigating respondents framed the money from the Fund as “hush money.”

People were being paid off not to go to court. How would I feel taking taxpayers' money in order for me not to be able to ask questions, hold people accountable?

The purpose of the VCF was to protect the companies involved. It was corrupt and dishonest from its inception. This is not an appropriate use of tax dollars.

I did not want the government to whitewash the entire event. My sister's murder will not be swept under the rug of patriotism.

I thought it was immoral to take the Fund.

For these respondents, to litigate meant to refuse “ex post facto taxpayer-financed blackmail” intended to keep people from pursuing what litigation offered.

What did they believe litigation offered? Three themes were clear. First, litigants wanted information:

I felt that I had to find the facts. Seventy to 80% of my decision was based on having the parties have to come to the table and we have to tell you what we did or didn't do. They're [airlines, security services] going to have to go to deposition—I get joy out of that …. I want to hear, “You had information since 1974 that this was a problem.” I want them to own that.

It's not about money to me. All I want is discovery. I don't care if the jury award is $1 …. It will be very upsetting to me if this turns out to not produce information. If I can't get information, why not take the money?

Second, they wanted accountability and authoritative public judgments about wrongdoing:

[Litigation] is one way of saying no, it wasn't just the terrorists. There was a lot of ordinary negligence that led to people's deaths …. It's not just about the facts; there is a need to bring those facts to accountability …. It's not about winning; …. It's about shining a very bright light on the facts …. I just want that to be a historical conclusion: more people could have been saved, there was truth.

What I'm looking for is justice—someone held accountable for the murder. There are people who did not do their job. No one has been fired, demoted.

And third, they wanted to do something to promote change:

I've discovered the system doesn't work. I'm outraged. Not just that my husband was murdered, but that three years later, nothing has been done …. What 9/11 represented was a massive example of how things don't work. We have to be willing to stand up and fix this.

It was clear that for these respondents, litigation was not about pursuing a pot of gold. They recognized that caps on liability and the uncertainties of litigation made it unlikely that the lawsuit would produce substantial sums. Rather, the choice as they saw it was it was about relinquishing gold in favor of something they saw as more important. Even though they knew it would be “hard, risky,” the decision to litigate was a strongly principled one to reject being bought off from the obligation to find out what happened, hold people responsible, and see things change, to “stand up and fix this”:

Once I realized what it was I didn't want anything to do with it, from very early on. There was no guarantee, but it's what I needed to do for my husband …. Once I heard about the limitations on the VCF—going with the Fund meant I gave up my right to legal recourse, there would be no attention to accountability issues—no other course of action was possible for me.

Choosing Cash, Foregoing the Courthouse

The nonmonetary considerations—gaining information, prompting accountability, and seeking change—that motivated the litigants I interviewed were also plainly evident in how many who chose the Fund over a lawsuit framed their decision. Indeed, what distinguishes the litigants from those who chose to go with the Fund in this sample may be not a fundamental difference in how litigation was framed, but rather in the capacity or willingness to take on the “hard, risky” path of what all anticipated would be a long, emotionally painful, and potentially deeply dissatisfying process. Choosing money over law was not necessarily the easy choice many thought it would be. As one of the litigating plaintiffs saw it,

We had the luxury of filing a lawsuit; my sister did not have a family …. Even though I feel so strongly about not going with the Fund, I was just lucky enough not to have to. I think there's a lot who wish they didn't have to go with the Fund.

Fifty-seven percent of respondents who explained their decision to go into the Fund indicated that the decision was “somewhat” or “very” hard. Some were in fact heartbroken and ashamed by their decision not to litigate. One mother was in tears, swearing me to secrecy, about having finally “given up” and filed with the Fund on December 22, 2003, the day the Fund closed. Ten percent of respondents (14) answered yes in response to a survey item that asked if they now regretted their decision to go with the Fund and wished they had filed a claim in court instead; another 25 percent indicated that they were unsure whether they made the right choice in filing with the VCF. Approximately 30 percent of the respondents who filed claims with the VCF and responded to questions elsewhere about their decisionmaking expressed a wish or desire that they could have pursued litigation, or cited obstacles to litigation as part of their reason for ultimately going with the Fund.

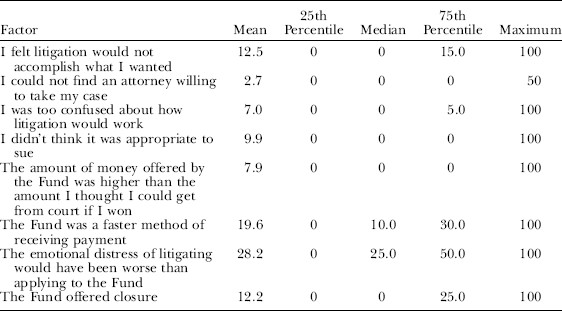

Table 2 shows the weightings attributed to a set of possible factors by respondents who said they found the decision to file with the Fund “somewhat” or “very” hard. (The options presented were generated from initial interviews and pretesting.)

Table 2. Factors Making Choice of VCF Difficult (N=53)

These results show that those who found the decision difficult did so because of both monetary and nonmonetary considerations, but that nonmonetary considerations dominated. Concerns about the “fairness” of Fund payments and uncertainty about the size of the payment received a combined mean weighting of 27.6. Nonmonetary considerations—a desire to punish, a desire for a trial to find out more or to promote change, the duty to pursue those responsible, a sense that it was wrong to be asked to give up the right to go to court or that the Fund was set up to keep families quiet—received a combined mean weighting of more than twice that: 64.4. The means, however, are misleading in the sense that Table 2 also makes it clear that the individual respondents varied significantly in terms of the subset of factors that mattered to them: even for factors that received significant weight on average, half of the respondents placed little or no weight on that factor. Not everyone, for example, found the desire to punish, with a relatively high mean weighting of 13.3, significant: half accorded this factor a weighting of 2 or less. Twenty-five percent placed a weighting of 20 or more on the desire for a trial to find out more about what happened, but no one put a weight of more than 50 on this factor; 25 percent put a weight of 10 or more on the duty to pursue those responsible, and for some this was the sole deciding factor, as was, for others, the desire to prompt change.

Even including those who did not find the choice difficult, however, it is clear that monetary considerations were not dominant in how respondents who filed with the Fund ultimately chose. Table 3 shows the allocation of weights across a set of eight possible factors. In terms of the mean combined weights, monetary considerations—how much the Fund would pay and how fast—received significantly lower weight (27.5) than nonmonetary considerations (72.5). Again, however, the means mask substantial differences among respondents. Less than one-quarter (22 percent) placed any weight at all on the idea that the amount of money offered by the Fund was higher than what might be obtained in court, and the weighting on this factor in the combined means comes from a minority for whom this was a decisive factor. Narrative answers indicate that some of those who indicated that the amount of money available in court was not a factor were worried about the possibility that there would be no recovery in court; interpreting these answers generously, however, still leaves us with 70 percent who placed no weight on the “lottery” trade-off between a certain Fund payment and an uncertain court award. The prospect of receiving money quickly rather than having to wait for litigation to conclude was a more widespread concern, with half of the respondents giving this factor a weight of at least 10. Overall, however, the greatest agreement was with respect to emotional considerations: half placed a weight of at least 25 points on the idea that “the emotional distress of litigating would have been worse than applying to the Fund.”

Table 3. Factors in VCF Choice (N=93)

The fact that nearly all (97 percent) of the potential 9/11 litigants ultimately chose the Fund over litigation is often taken to mean that, whatever nonmonetary values might have been associated with litigation, people put to the choice in the end go with the money. Tables 2 and 3 indicate that this interpretation of the choice as a revealed preference between monetary and nonmonetary values, however, is misguided.

The decision to go with the Fund was clearly for many a negative one, driven by a capitulation to reality and brute facts. For some, particularly women with children, the poor, and the injured, reality was dominated by immediate financial need:

I was going to be left homeless. I was way behind in my bills. My son was my major means of support for both me and his two younger brothers. Without his income we would have been left to apply for food stamps and welfare and would have lost our home.

My only income as a stay-at-home mom for 21 years was to take the money.

Having been disabled, I was worried about losing my house. I did not have the ability to pay for long-term therapy and medical costs and I would not receive enough from my disability pension or insurance coverage.

As evidenced by the fact that as against the total economic loss calculated by the Fund ($7.8 billionFootnote 5) offsets for insurance received by claimants totaled only $2.5 billion, few families had the insurance coverage that could replace what the Fund ultimately calculated as the financial hole left by disabling injury or the loss of a spouse, parent, or child who supported them.

For others who reluctantly went into the Fund, reality was dominated by age: litigation was widely expected to take 15 to 20 years to resolve.

Time was the biggest factor …. I didn't think I'd live long enough to ever see this case go to court and/or ever be resolved.

I was told by an attorney that at my age (60) I would have to wait for possibly 20 years to recover any money from litigation.

For many, litigation—however desirable in theory to achieve principled goals—was perceived as unlikely to achieve these goals in practice.

I felt that litigation would go on for so many years, we would not get any answers.

Litigation would absolutely have created incentives to take better security steps. They would buy their way out of this mess …. [But] the VCF law gave blanket immunity to those who were really responsible.

From what I experienced, the Fund was shut-up money. I knew that there was a cap on amounts. That was suggesting to me that there wouldn't be an interest from lawyers, they wouldn't be fighting enough, getting information and answers.

And indeed, the perception that litigation would be ineffective was well-grounded. Congress explicitly created the VCF to divert people from litigation, and it imposed damage and liability caps as well as litigation burdens, such as the requirement that all suits be filed in federal district court in Manhattan, which undermined the capacity to fund litigation. Moreover, the message from the legal profession was clear:

The attorney that represented my case was an expert on former lawsuits against airlines, etc. He felt the way to be compensated was through the Fund.

I was told by my advisors that I really had no choice. My husband had no life insurance and I had four children, ages 8, 6, 2, and 10 months. I was told the compensation fund legislation basically took away my right to sue.

It was hard to find someone to take my case. One guy in a large personal injury firm told me, “I guess I'd take it if you pay for the investigation.”

At one point I asked an attorney about bringing a lawsuit against the government and was told that would be a no-win situation.

When you went to see an attorney you were told to go into the Fund …. I met with five attorneys. You don't have a case. You have a case but can't win it. It's unwinnable. You can't prove it. It's too costly. Go into the Fund … attorneys were getting 10 percent to do nothing. If the Fund hadn't been there they would have taken the cases.

I thought about a lawsuit. Another family member whose husband was in the same working group tried and was turned down [by attorneys].

Even judges imposed obstacles to litigation. One woman who wanted to pursue litigation in response to the death of her husband was challenged in court by the mothers of her husband's children from previous relationships; they wanted her to go into the Fund. Threatened by the judge with removal as the personal representative of her husband's estate, she capitulated and filed with the Fund:

I, to this day, can see both sides. Here's a widow who wants to hold someone accountable. Here's children who won't be compensated at all …. I felt like I had a smoking gun to my head: “Choose the money and be quiet or you can have your answers and be kicked off the estate.”

The widespread choice to file with the Fund should thus not be read as a widespread endorsement of money over litigation or an ultimate acceding to the financial frame offered by Congress, VCF personnel, and the legal profession. Several wished they had never been faced with the “choice” in the first place. Many felt that they had been bought off, induced to forego litigation in order to protect the government, the airlines, or other corporate entities.

We didn't get money for a mistake. We got money because they didn't want us to sue. A civil suit with subpoena power would have exposed stuff that they didn't want exposed. A lawyer smelling money will not be stopped in investigation.

I really loved my son. I miss my son—they could give me $20 billion. Damn them and their goddamn money … give me my son back. It would have been better if there hadn't been a fund. We would have sued and come to the truth.

The only thing I regret is that it was even a choice. Everyone was allowed off the hook, no one was held accountable …. There was compensation to families in a reasonable amount of time but the government was able to drop the ball. It was like hush money. It was not a good thing.

It truly seemed like hush money and blood money. It was not easy to do this and accept the money. I felt “dirty” after taking the money.

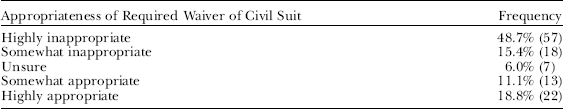

A significant majority of respondents felt that it was wrong that the VCF design required them to waive their right to pursue civil litigation as a condition of receiving money through the VCF. In a sample of 117, almost half found this requirement “highly inappropriate” and another 15 percent found it “somewhat inappropriate” (Table 4).

Table 4. Appropriateness of Waiver (N=117)

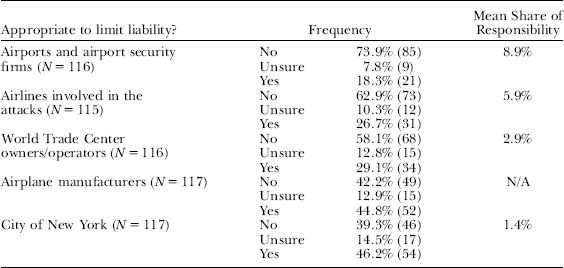

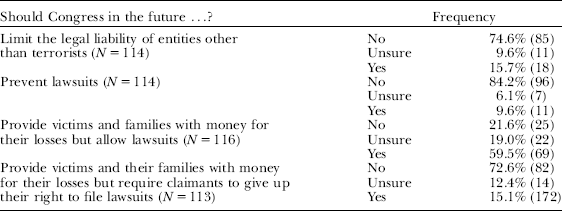

Respondents were also asked whether they felt it was appropriate to limit the liability of different entities, and their responses indicate that their views on this are tailored to the perception of responsibility for the deaths and injuries caused by the attacks. Table 5 shows these responses, arranged in descending order according to the degree to which respondents disagreed with the limitation of liability, together with the mean share of responsibility accorded each entity (from Table 1). Clearly, respondents were not simply expressing the view that limitation of any deep-pocketed defendants was wrong; rather, as a group, their views about whether it was appropriate to limit liability were perfectly rank-correlated with their views about the extent to which an entity shared responsibility for the harms inflicted.

Table 5. Appropriateness of Liability Limitations

The great majority of respondents felt that the limitation of liability, the effort to prevent lawsuits, and the requirement that victims and their families choose between money and lawsuits were steps no future Congress should take (see Table 6). What if they had not faced this choice? A number of respondents volunteered that they would trade the money from the Fund for the goals of uncovering what happened and holding people accountable.

I would give all my money for the truth to get out.

The families would give their money back if we could have a valid day in court.

Table 6. Opinions on Limiting Litigation

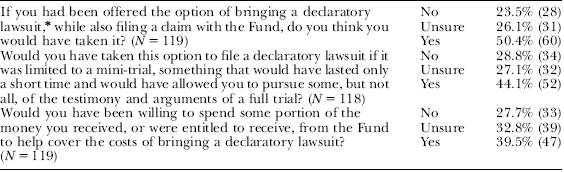

Systematically, respondents were asked whether they would have taken an option to separate out their financial needs from the nonmonetary goals associated with pursuing litigation. Their answers, shown in Table 7, indicate that a majority would have taken the option to pursue a declaratory judgment, with no damages, if allowed in conjunction with a Fund filing, and 40 percent indicated they would be willing to pay for this option with a share of the proceeds from the Fund. Less than a quarter indicated they would reject this option, and just slightly more than a quarter indicated they would be unwilling to pay for it.

Table 7. Declaratory Lawsuits

Note: Respondents were given the following definition: “A declaratory lawsuit allows you to ask a judge or jury to announce a judgment after a trial deciding whether a particular person or entity is responsible for a harm you suffered, but does not award any money.”

Reflecting an interest in a full accounting, as well as public judgment, fewer respondents were interested in a declaratory action when it was limited to a “mini-trial,” described as allowing some but not all of the testimony and arguments of a full trial, and (not shown in the table) of the 39.5 percent who were willing to pay for a no-damages declaratory trial, a majority (53 percent) indicated they would only be willing to pay if it was a full trial. Only 15 percent indicated that they would only be willing to pay if it was a mini-trial; the remainder (32 percent) was willing to pay whether it was a full trial or a mini-trial.

Information, Accountability, and Responsive Change: Framing Civil Litigation as Citizenship

It is clear that many people who ultimately chose to file a claim with the VCF, like the handful who rejected the Fund and filed a lawsuit, struggled with the choice, seeing litigation as something more than a means to increase payment for their losses. Whether forced to the decision by financial necessity, the need for emotional closure, or a perception (reinforced by the legal community) that litigation would be futile, many respondents framed the decision to file as one requiring the abandonment of important values. Like those who had the “luxury” of pursuing litigation, these respondents saw litigation as a means by which they could gain information, seek accountability, and prompt responsive change:

I wanted a day in court to face the people responsible—the people who allowed the planes to take off.

I didn't like the idea [of choosing the Fund] …. It's not about being compensated, or getting people back who died. It's that nothing gets fixed, no changes are made.

I was quite keen on getting the truth …. I wanted to find out more about various parties with accountability; from a safety perspective, what building evacuation and safety measures there were …. I wouldn't just want my day in court. I would really want that to be productive …. I feel I do not have in my hands what I hoped for—very definite answers to questions and perhaps steps for the future.

In the aftermath of Pearl Harbor, you had a government that sought to lay blame for the tragedy. The feeling was “punishment is the order of the day.” That didn't happen with 9/11. No one was fired, no one was blamed for the security lapses. That was wrong.

I'm not a person who would have sued before, or been suspicious. This has changed my views of courts. Before 9/11 I would have thought the Fund was a good thing, giving people money. But now I question why the VCF was created. It changed my view of the purpose of litigation …. If I had litigated, I would have felt like I did something. I took a stand. I helped to change things. If actual changes got made, if that came from litigation—it would mean I had done something in response to 9/11, [my husband's] death would have meant something.

I do not mean to suggest that everyone, even in this particular survey sample—much less in the entire 9/11 victim population—saw litigation in these ways. But it is clear that many did, and their framing of the decision to litigate or not speaks, I believe, to beliefs about fundamental ways in which civil litigation, at least in its ideal form, is seen to serve important functions beyond monetary compensation. Moreover, the framing articulated by these respondents was significantly political in nature. Respondents did not (only) seek information, accountability, and responsive change to serve their personal interests; they clearly articulated these values as shared, public, civic values.

Many, for example, clearly spoke as a member of the broader community, in terms of the American public as a whole, in expressing what “we” did not know about the attacks, how “we” failed, and what “we” must do in response.

We can blame it on them, but we know what they're doing, that they're trying to hurt us. We know they have plans. Where are the people responsible for infiltrating things and stopping them? It's like the terrorists were doing their jobs and they were successful, and we weren't successful at our job.

We are idiots. As humans we are careless unless something serious happens. It is a cycle. If nothing happens for another few years, we will let down our guard. There will be another Compensation Fund and another. I wish I had had the courage to sue.

It is our fault as Americans. We are fools. We allow people to take flying lessons without knowing who they are. Why is it so easy to get into the cockpit? We let people on the planes with knives.

If we don't learn from 9/11, that would be the shame.

Many emphasized that the information and accountability functions of litigation had to occur in a public forum:

I am worried that the facts will never be made public and nothing will change.

The process of litigation gives rise to both exposure of wrongdoing and financial penalties. It provides sunshine that the government and regulators are not providing …. As flawed as the process is, if it exposes negligence to the light of day, that's when a change can happen.

Outsiders don't see the justice denied, the accountability and responsibility denied; the cover-up by the city and the fire department …. I want the public to know what is going on. Everything is better in the light.

Some spoke specifically of pursuing litigation in terms of an obligation to their fellow citizens and the country:

I feel like I betrayed somebody—maybe the rest of the country—by not pursuing answers …. I wonder what the fallout is—who got away with murder? What changes were made?

How would I feel taking taxpayers' money in order for me not to be able to ask questions, hold people accountable?

Some appealed directly to the Constitution and their understanding, explicitly, of the role of litigation in American democracy:

The poor founding fathers, they would be turning in their graves …. People should have taken better care of communication equipment and skyscraper safety. Those who are suing are saying “no, this can't happen.” This is what the founding fathers intended.

It was wrong for the government to dictate who you can sue and who you can't sue. “If you want this money, you can't sue the airline.” That is not American to me. America is based on certain rights and we have the right to bring a lawsuit against anyone.

The last blow was that you had to give up the right the Constitution provides for all citizens. We had to go into the Fund blind, poor, and with no recourse.

It thus seems clear that for many, litigation represented not merely a means of obtaining monetary compensation but also—more important—a means of acting as a responsible citizen. To see in the search for disclosures about “what happened,” public judgments of accountability, and responsive change only a search for psychological release or personal satisfaction misreads, I believe, the integrity of the public-spirited thinking about litigation in which many of these respondents engaged.

Conclusion

Reference BoyleBoyle (1998, Reference Boyle2000) has argued that cross-national differences in individualistic legal activity can be explained by differences in the political frames the citizens of different countries bring to bear on the process of transforming concerns into legal disputes. She claims that highly interpenetrated societies—ones with a lack of clear boundaries between the state and civil society—are ones in which individuals “have an obligation to act as agents for other individuals and for society as a whole.” In such societies, “the guiding ideology is that individuals are responsible for making a ‘good’ world. Lawsuits are brought under the noble principle: ‘If I don't do it, nobody will’ ” (Reference BoyleBoyle 2000:390–2). The 9/11 victims and family members who participated in this study provide a richly textured view of how the decision to litigate or not can be informed by a strong sense of the duty to act as an agent of the community to gain information about what happened, to hold people accountable, and to play a role in prompting responsive change. These potential plaintiffs framed the decision to litigate at least in part in terms of what it means to be a citizen, particularly a citizen in the United States at a time of crisis.

My emphasis on community and citizenship—and the extent to which respondents framed their litigation options in terms of their political responsibility as citizens to act—highlights the constitutive risks posed by the “anti-litigation” (Reference BurkeBurke 2002) and managerial judging (Reference ResnikResnik 1982; Reference Heydebrand and SeronHeydebrand & Seron 1990) efforts to limit the use of courts through ADR and settlement from the literature that have flourished in the past quarter-century in the United States and increasingly throughout the world. Criticism and concern about these efforts has been around for almost as long (Reference FissFiss 1984; Reference Nader and AvruchNader 1991; Reference LubanLuban 1995; Reference ResnikResnik 2000, Reference Resnik2006). These critiques, however, have largely emphasized the instrumental capacity of litigation to secure rights and entitlements. What emerges from this study—an emphasis on the process of litigation and the role of courts as a venue in which citizens participate in acts of governance—is a theme that, while implicit in the critiques that deplore the diminishing of public discourse, has not been analyzed as a political function of litigation distinct from the instrumental role that public litigation plays in securing legally mandated redistribution and rights.

Like the procedural justice literature in social psychology (Reference Lind and TylerLind & Tyler 1988; Reference TylerTyler 1990, Reference Tyler2005; Reference Tyler and HuoTyler & Huo 2002), this study clearly presents a view of litigation as a process that is important in and of itself to citizens' understanding of themselves as members of a political community. Tyler and others, however, focus on the importance of fair procedures to people's willingness to cooperate as objects of governance—to submit to the power exercised by others. In sharp contrast, the importance of process identified by this study is to people's understanding of themselves as agents of governance. Whereas Tyler's respondents are interested in their “day in court” in order to be heard and to experience some control over what happens to them, the respondents in my study are interested in their day in court in order to require others to speak, to be publicly judged, and to change their ways. The responses here suggest that the courthouse is perceived as a place where individual citizens as plaintiffs are able to exercise a particularly potent form of political participation, effectively stepping into the shoes of the state to require those who may have failed in their legal duties to disclose information about their conduct, to prompt authoritative determinations of accountability, and to set the stage for responsive change.

In this sense, this study connects the study of courts and perceptions about the legal process and the pressures on courts to the extensive literature on participatory democracy (Reference PatemanPateman 1970; Reference BarberBarber 1984). As Reference SkocpolSkocpol (2004) has articulated in a different context, large-scale institutions play a role in providing an overtly civic and structured framework in which individuals participate in the political process and exercise citizenship. It is not hard to read in the responses from those who struggled with the decision about whether to take a check in exchange for relinquishing their right to litigate in response to the enormity of the losses suffered on September 11—by them and by the country as a whole—a keen sense of the courts as just such an institution. The experiences of these 9/11 respondents throws into sharp relief a fundamental rift between the dominant way in which legal actors frame the goals of litigation and the way those who find themselves in a position of pursuing potential litigation in response to loss see the institution. Several respondents spoke specifically of the—to them surprising—divergence between what they saw as principled goals and what the lawyers and judges with whom they dealt saw as purely monetary concerns.

Many legal commentators, while acknowledging nonmonetary goals, discount them as unrealistic. Feinberg, for example, responds to the 9/11 victims' desire to sue to pursue information and accountability with his legal assessment that litigation would not produce these outcomes and that the 9/11 Commission was the appropriate avenue for pursuing these nonmonetary goals (Reference FeinbergFeinberg 2005:165). Schneider agrees that “for many potential claimants, getting the money is not enough” but observes that “compensation is all the government can provide” (2003:474–5). Shapo suggests that while “the process of unearthing information [in litigation] in itself could have symbolic importance” and “the exercise alone might be psychologically satisfying.” he agrees that the goal of “finding out what really happened” is not likely to be realized (2005:231). Reference GennGenn observes regretfully that financial compensation is “the only remedy that the legal system can deliver as a result of a negligence action” (1999:11).

It is clear, however, both from the values many respondents felt they had to forego in order to accept money from the VCF and from the explicit support (50 percent in this sample) for a purely declaratory lawsuit, that much of what litigation is perceived to accomplish is gained through the process of litigating and judgment itself: discovery of information and public assessments of accountability. While litigation is almost certain not to live up to any ideal process respondents might have had in mind—lots of information may never be forthcoming, for example—one does not have to look beyond even the extraordinary circumstances of terrorist attacks to find evidence of what civil litigation can accomplish. The tort litigation that has gone forward in the September 11 case, hearing the claims of numerous corporations that suffered business interruption and property losses, and the 100 personal injury and wrongful death plaintiffs who chose not to enter the VCF (of whom six had still not settled as of February 2008), has thus far resulted in an authoritative judgment about whether airlines and airline security firms owe duties of care to potential victims on the ground and whether the World Trade Center owner/operator owed duties to occupants of the buildings to take steps to prevent even those injuries caused by the deliberate crashing of hijacked airlines into buildings (answer: yes [In re September 11 Litigation 2003]). In the tort litigation over the 1993 World Trade Center bombing, discovery focused on the fact that the Port Authority (which then operated the World Trade Center) had obtained consultant reports in the 1980s identifying the towers as a possible terrorist target and the risk of car bombing posed by allowing public parking beneath the building; the jury verdict for the plaintiffs in the case reflected a public authoritative judgment that the Port Authority bore a share of responsibility (two-thirds) for the deaths, injuries, and damage incurred in the attack.

The focus in the legal profession and academic analysis on the monetary aspects of litigation is, of course, well founded. Achieving these results in the September 11 and World Trade Center bombing litigation cost a great deal of money. Indeed, the disillusionment with courts and litigation that pervades the legal profession and judiciary (Reference ResnikResnik 2000; Reference GalanterGalanter 2002; Reference BurkeBurke 2002) is at least in part in response to the explosive growth in the costs of litigation. However, most of our efforts to address the crisis entail efforts to divert matters out of litigation, rather than to find ways to achieve the goals of litigation in a more cost-effective way. Interestingly, the VCF itself is evidence of the willingness in the legal profession to streamline procedures and even entitlements in order to achieve the monetary goals of litigation in a more cost-effective way: limiting liability, granting extraordinary discretion to a single decision maker, using grids, and imposing time limits on hearings and claim determination. But we have yet in our legal reform efforts to put similar efforts into streamlining procedures and entitlements in order to achieve the nonmonetary, indeed democratic and political, goals of litigation: limiting discovery, imposing time limits, constraining the use of experts, and so on. Like the critique of ADR and public authority found in the attention to the framing of everyday troubles in the legal consciousness literature, the thoughtful and public-minded framing of these values by the 9/11 respondents in this study speaks to the cost of focusing only on how to get matters out of litigation and not how to afford access to the civic processes of litigation.

Appendix: Sample Characteristics