WOOL, SHEPHERDS, AND CAPITALIST FARMING

During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, wool from merino sheep was a vital commodity for the Cape Colony and South Africa. White settlers began to farm with merinos in response to the increasing demand for imported wool from British textile factories in the first half of the nineteenth century. As noted by Marx, wool farming in the British Empire initially expanded to Scotland, where people were “replaced” by sheep. But the merinos were better suited to the climate in colonial areas in the Cape, Australia, and New Zealand, which offered new possibilities for exporting wool to Britain. The establishment of wool farming incorporated the colonies into capitalist production in a peripheral setting in relation to the core in Britain. Philip McMichael clarifies this relationship when he notes, regarding Australia, that “metropolitan industrial capitalism and its growing world market framed British expansion and socioeconomic possibilities in the colonies”.Footnote 1 The Cape was no different from Australia in this regard. Farmers in the Cape sold wool on the world market and used the profits to accumulate capital, which they invested in production.

Merino sheep thrived in the arid Karoo region in the eastern parts of the Cape, which became a centre for wool farming. In the process of agrarian capitalist expansion, based on commodities such as wool, black and coloured peasants and pastoralists were increasingly dispossessed of their land and livelihood and transformed into shepherds and labourers on the farms of white settlers. But despite their important role in wool farming, shepherds and other labourers have been overlooked by historians, notwithstanding Robert Ross’s claim that relations on farms in the Cape were capitalist at a much earlier stage than in the rest of South Africa, mostly because of wool.Footnote 2 Goats and ostriches contributed to farmers’ income, but merino sheep and their wool were at the centre of the rural economy. Wool was the Colony’s main export product from the 1830s to the 1870s and, in terms of value, it was second only to gold in exports from the whole of South Africa between 1910 and 1950. William Beinart therefore argues that closer attention should be given to pastoralism than has previously been the case in explanations of agrarian capitalist development in South Africa.Footnote 3 This article does just that. It contextualizes wool farming within the framework of expanding agrarian capitalism and analyses both how the work of shepherds changed and, as a result, how their relationships with farmers were transformed.Footnote 4

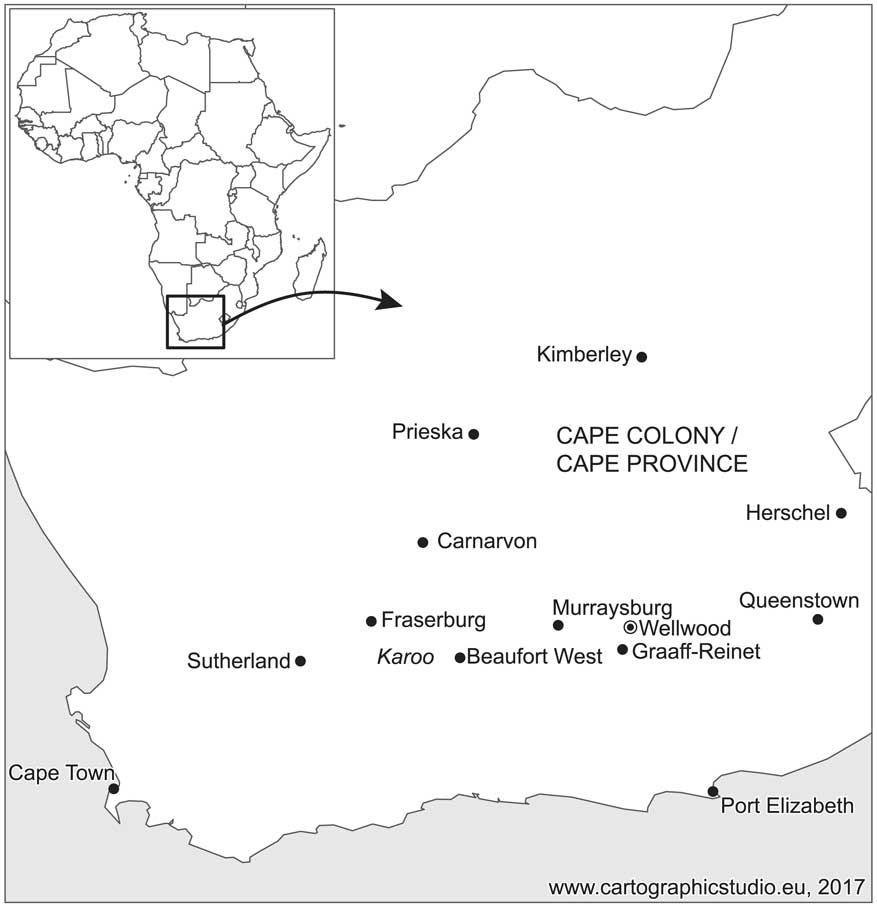

Figure 1 Sheep farming areas in the Western Cape.

In wool-farming areas of the Cape, labour relations – by which I mean relations between farmers and hired labour – were capitalist by the mid-nineteenth century on the “wealthier farms”, according to Clifton Crais. He notes that labourers were proletarians, but also argues, as have other scholars, that remunerative practices were characterized by a combination of cash wages, rations, and grazing rights, meaning that labourers were not entirely proletarianized.Footnote 5 This state of semi-proletarianization has been noted in various colonial contexts, and it suggests that, globally, the working class has not exclusively been comprised of “free” wage labourers.Footnote 6 There were similar arrangements in Argentina, where wool farming also expanded during the nineteenth century. The capitalist wool-farming units were dominated by wage labour, but, depending on how capital accumulation could best be secured, Argentinian farm owners also acquired labour through sharecropping arrangements and by exploiting the labour of the wives and children of tenants and shepherds.Footnote 7

Cape wool farming was initially based on shepherds tending sheep throughout the day and night. But in the late nineteenth century, technology such as fences and windmills for water was introduced. Lance van Sittert argues that fences had “transformative effects on social relations” in the countryside and contributed to increased profits for farmers. He also notes that fences expedited the process by which peasants were turned into labour migrants.Footnote 8 The fences thus contributed to proletarianization, but Van Sittert does not mention how they impacted the shepherds, the people most affected by this technology. In fact, we know very little about how fencing impacted shepherds. Colin Bundy notes only briefly that it reduced the demand for shepherds among farmers.Footnote 9 Sean Archer provides a slightly more detailed account when he argues that, due to fences and windmills, shepherding had been made redundant in “most areas” of the Karoo by the end of the 1920s.Footnote 10 So, we know that the role of herding was reduced, but not when this happened and at what rate. Furthermore, did the diminishing role of shepherds mean that wool farming was conducted without manual labour?

The purpose of this article is therefore to explain how the role of shepherds was transformed and how production was conducted on wool farms in the Cape between 1865 and 1950. The period begins well before fencing became widespread and ends a few decades after the supposed disappearance of shepherds. By focusing on this longer period, it is possible to take account of all relevant transformations in labour relations.

We can estimate the impact of new technology by comparing the Cape with other wool-producing peripheries. In Australia, too, wool farming was initially conducted with shepherds. After a few decades, however, it was difficult to find labour, partly because shepherding was “unattractive” compared with other forms of labour.Footnote 11 The cost of labour thus increased, creating an incentive for farmers to fence their farms. In the Cape, this process was much slower and farmers relied on shepherds instead of technology for a considerably longer period of time. Archer argues that this was partly due to the “lower cost of Karoo farm labour relative to Australian”.Footnote 12 However, he does not further analyse how farmers acquired labour and how that affected farming. In Argentina, fencing was introduced in the 1850s, but it was intensified in the 1870s – about the same time as in the Cape. Farmers in Argentina also complained about high labour costs. Although it is unclear if that was the only reason for fencing, the new technology reduced labour demands by as much as fifty per cent.Footnote 13 In that regard, it was advantageous to fence. However, in the Cape, where labour costs were lower than in both Australia and Argentina, we must instead focus on how farmers acquired labour and to what extent that impacted their use of technology. But it is also important to include farmers’ responses to competition for labour from the mining industry, which were behind many of the changes in farming on the highveld.Footnote 14 We can presume that mining also had an impact on Cape wool farming.

The main source of labour for both farmers and mining in South Africa were black and coloured peasants, who could not sustain their families on their plots of land. An analysis of the racial composition of the labour force is vital to our understanding of labour relations, but it is insufficient on its own. We must also consider the generational perspective. Whereas shepherds in both Australia and Argentina were mainly adult immigrants from Europe, their counterparts in southern Africa were often children or youths from black and coloured families. Beinart and Charles van Onselen have described how white farmers made arrangements with black tenants and labourers to hire their children for herding duties.Footnote 15 The hiring of children for this task was not something that farmers invented. They simply exploited existing generational divisions of labour within the families they hired. In pre-colonial societies in southern Africa, the role of young boys was to herd livestock.Footnote 16 Children could, however, use wages from farm labour to free themselves from generational ties, as Beverly Grier has shown in colonial Zimbabwe.Footnote 17 In the case of Cape wool farming, it is therefore important to analyse such familial relations among the labour force in connection with new technology, since the introduction of fences and windmills implies that the herding work carried out by children was disappearing.

Herding existed in southern Africa before there was capitalist wool farming, but the task itself was neither capitalist, nor pre-capitalist. Instead, it is more accurate to say that the generational ties, which were exploited by farmers, were pre-capitalist. To avoid confusion, it is important to define these various forms of labour. Capitalist labour relations are those that involve a labour force hired by a farmer and paid in cash or in kind. Pre-capitalist relations refer mainly to family-based production, where all family members are expected to contribute. Such relations were found among the black and coloured peasants and pastoralists who sought work on white farms. The farmers’ willingness to exploit the generational ties shows how capitalist production can incorporate certain pre-capitalist relations. Rosa Luxemburg emphasized that pre-capitalist relations were crucial to capitalist production, but argued that they would invariably be consumed by capitalism. However, that these can co-exist has been shown in the South African context. For example, Harold Wolpe stressed the importance of the mainly pre-capitalist reserve areas for the country’s capitalist development, and Mike Morris notes that the labour tenancy arrangements on the highveld were intricate parts of capitalist production.Footnote 18 In a pastoral region such as the Karoo, access to land for grazing the livestock of labourers and tenants should also be considered as a commodity as important as any other. This, then, implies that capitalist farming might also include non-proletarian labour.

The Rubidges on the Wellwood farm in Graaff-Reinet were one of the farming families that benefited from wool. This article uses the farm diary, which has been kept since the 1830s, to illustrate how transformations in farming impacted labour relations. Wellwood’s representativeness and usefulness as a source has been discussed by Van Sittert and Beinart.Footnote 19 It must be pointed out that the Rubidges have been at the forefront of innovations such as fencing and that the farm has been very successful. Wellwood is thus not entirely representative of Cape wool farms. I would like to stress, however, that, together with select committee reports and census material, the farm diary’s detailed account over a long period of time enables an accurate analysis of wool farming in the Cape.

KRAALING AND TREKKING

Wool farming in the mid-nineteenth century was based on a practice called kraaling and trekking. The term kraaling referred to the place where sheep slept at night, the kraal, while trekking referred to the walks back and forth to grazing pastures. This meant that the shepherd was responsible for the sheep all day in the veld, or field. However, there were control mechanisms, which farmers could use, for example when the shepherd brought the flock home to the kraal in the evening. As John Noble noted in 1875, it gave “full opportunity to the owners to count them, look to their health, and other matters of management, as well as to check depredation both human and brute”.Footnote 20 By counting the sheep and checking their health, the farmers could maintain control over farming operations, but clearly also over the shepherds. Despite the crucial role of shepherds, their wages were approximately equal to those of general farm labourers. In the 1860s, few shepherds earned more than £7 per year in cash, although grazing rights and rations supplemented their salaries.Footnote 21

As with most forms of farm labour in South Africa, shepherding was conducted by black and coloured people. Almost all “pastoral servants” in the 1875 census, and almost all “shepherds and herds” in the 1891 census, were either black or coloured. This racial composition was the same in the twentieth century.Footnote 22 However, in the nineteenth century some farmers also employed white shepherds, called superintendents, who were foremen and lived in the veld on stations close to watering places.Footnote 23

We cannot be sure of the exact numbers, but in 1891 there were 38,869 “shepherds or herds” in the Cape.Footnote 24 The reference to “shepherds or herds” in the census indicates that people who herded goats and cattle were also included in this category. It was not unusual for Cape wool farmers to combine sheep with goats and ostriches. Some of the “shepherds or herds” thus worked with animals other than sheep or with a combination, which was possible in cases where farmers had both sheep and goats. However, in most census years, sheep numbers by far exceeded the number of other livestock, and we should assume that an absolute majority of “shepherds or herds” worked with sheep.Footnote 25

It is also difficult to estimate the average number of shepherds on a farm during the late nineteenth century. Their number was determined by the number of sheep and a farmer’s ability and willingness to pay wages or allow grazing rights. The 1872 Select Committee on Fences estimated that a shepherd oversaw approximately 500 sheep. Some farmers, such as John Molteno and his partners in Beaufort West, had 35,000 sheep; another farmer in that district had around 20,000 sheep. The number of sheep ranged from these high figures down to about 1,500, according to Noble.Footnote 26 But many farmers likely had even fewer sheep. If the recommendations of the Select Committee on Fences were followed, Molteno would have had about seventy shepherds. That was not the case for most farmers. Judging from the evidence given by farmers to the Commission on Native Affairs in 1865, the average number of labourers on farms in twelve districts in the Eastern Cape ranged from seven in Victoria East to twenty-three in Murraysburg.Footnote 27 These represented the entire labour force, both shepherds and general farm labourers.

It is possible to provide a more detailed account of the labour force on Wellwood in Graaff-Reinet. According to a list of employees created for the census in 1875, there were four people reported to have been hired as shepherds out of a total of forty-four black and coloured people on the farm.Footnote 28 Wool farming consequently included categories of labourers other than shepherds, and the majority were general farm labourers. In addition to the permanent labour force, people were hired for occasional work, for example during shearing time. There were about 2,500 sheep and more than 700 goats on the farm at that time. Given those numbers, each shepherd was responsible for flocks of 800 small stock. Compared with the estimate of 500 sheep per herder, the ratio on Wellwood was fairly high. However, a closer analysis of the diaries on Wellwood indicates that there were actually more people working as shepherds than was reported in the list of employees. In 1875, there appear to have been six people on the farm performing the duties of a shepherd.Footnote 29 Under those conditions, the average number of sheep per shepherd was about 530, a figure in line with the estimates of the Select Committee on Fencing in 1872.

The estimate of about 500 sheep per shepherd in the Cape differs considerably from the Argentinian case, where, in the nineteenth century, a shepherd was responsible for between 1,500 and 3,000 sheep. The difference is easier to comprehend if we consider that the Argentinian shepherd did not work alone, but had help, either from family members or from hired hands. Sabato alludes to the landlord-tenant relationship that many shepherds worked under.Footnote 30 That relationship implied that family members were expected to work. Similar arrangements were seen in the Cape. Shepherding was conducted not only by the individuals who were formally hired – often male heads of families – but also by their family members. Children worked in various farming sectors in southern Africa and were particularly important during harvests.Footnote 31 However, children worked as shepherds in wool farming, and so were also involved in daily operations. There are no figures revealing the ages of shepherds during the nineteenth century, but the census of 1904 provides a detailed account. By then, there were 34,093 “shepherds or herds” in the Cape. It was obvious that shepherding was considered work for the young. Children and youths under the age of twenty made up forty-five per cent of the people in that category. As many as twenty-eight per cent were children under the age of fifteen.Footnote 32 Clearly, children were crucial to the wool-farming economy and to their families, since they earned cash wages, stock, and grazing rights.

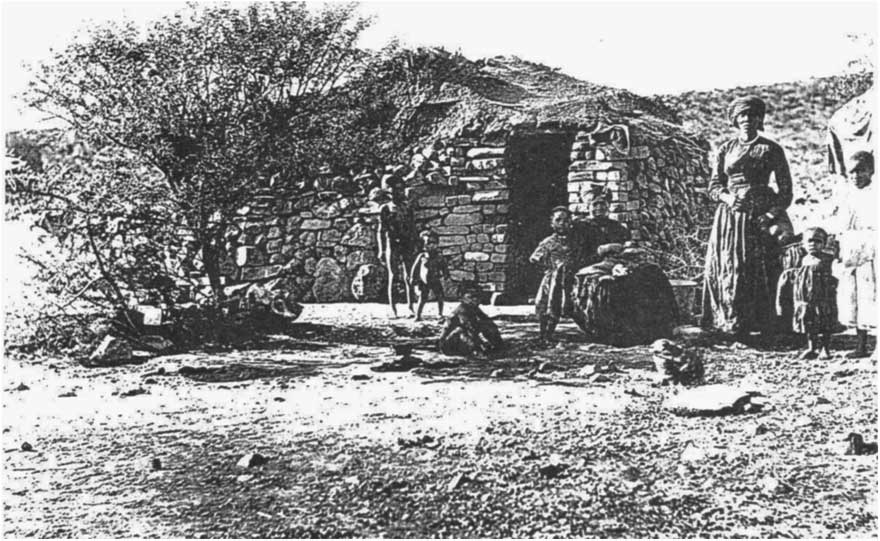

Figure 2 Shepherd’s hut on a Beaufort West farm, probably 1890s. Cape Town Archives Repository. Jeffrey’s Collection. J1651. Used by permission.

The importance of children is evident in the records of Wellwood in the mid-1870s. According to the list of employees in 1875, there was one boy called Mentor, aged thirteen, who was employed as a shepherd. Mentor was the son of the shepherd Cobus, who had another son, or at least a dependant, called August, who was twelve years old. August also worked on the farm, perhaps as a shepherd.Footnote 33 Although Mentor was the son of Cobus, he was apparently hired in his own right and enumerated as an employee on the farm. He was, however, not mentioned in the diaries as being responsible for a flock of sheep, which indicates that he worked with his father. Nevertheless, both Mentor and August earned individual wages. They were paid two goats each after six months and an additional two shillings per month.Footnote 34 Even young shepherds could thus receive animals as payment, even though it was most likely that the father, Cobus, would accumulate the stock, since stock ownership within families was usually limited to fathers. The boys thereby helped to earn the stock that they would later receive from their fathers for lobola, or bride price, when marrying.

PRIVATIZATION, ENCLOSURES, AND CREATION OF VALUE

The incorporation of the Cape into capitalist wool production required the privatization of land, i.e. land being turned into a commodity, on which wool could be produced.Footnote 35 That commodity was not one large production area, however. Some areas were better for grazing than others, which can be seen in the practice of kraaling and trekking sheep. During the end of the nineteenth century, the practice of kraaling and trekking was criticized by experts. The arguments centred on the destructive impact of these practices on both the land and the animals. The long walks destroyed the veld and contributed to soil erosion, but they also damaged the sheep and the quality of the wool.Footnote 36 If farmers wanted to increase profits by improving their sheep and the resulting wool, they had to abandon the old practices of kraaling and trekking and instead put the sheep in fenced camps, where they could run free throughout the day and night. Investments in fences would generate returns for the farmer. According to P. Watermeyer in Richmond, a fenced farm “trebled and quadrupled in value”.Footnote 37 But it was a fairly expensive approach, apparently costing £75 per mile.Footnote 38 A farm of 3,000 morgen would consequently cost £1,000 to enclose.Footnote 39 That was a substantial investment for most farmers, indicating that the early capitalization of farming contributed to a stratification of farmers into those who could and those who could not afford fencing. Wire for fencing had to be imported. In the nineteenth century, it was bought mainly from Britain, which further bound Cape farmers to the imperial power.Footnote 40 Progressive farmers were, however, aided by the introduction in 1883 of a Fencing Act, which enabled them to force their neighbours to share costs of fencing borders. Van Sittert notes that the Act, together with reduced import duties on wire after 1890, quickened the pace of enclosure. As is Australia and Argentina, fencing in the Cape contributed to increasing sheep numbers and better-quality wool.Footnote 41 It was thus a highly profitable investment from the viewpoint of the colonial economy.

In Australia, fencing seems to have been initiated to reduce labour costs and was regarded as “the long-term solution” to the so-called labour problem.Footnote 42 In the Cape, however, there were five different reasons why farmers fenced, according to Van Sittert: to improve the veld, improve the health of the stock, enable farmers to manage increasing stock numbers, and to keep jackals and stock thieves out. He further notes that fences had a disciplinary function regarding “respect for private property” among the “colonial underclass”,Footnote 43 to which we must count shepherds. No doubt, all of these reasons were important, but the progressive farmers in the Cape appear to have started fencing because they wanted to improve their farms and thereby produce better sheep and wool. The innovator on Wellwood, Charles Rubidge, was one of the first farmers in the Graaff-Reinet area to implement enclosures on his farm, beginning in 1853, and possibly even earlier. In 1862, he introduced wire fencing for the first time, and was “one of the first in E. Province” to do so. For him, and other farmers, fencing the boundary was not as important as fencing camps inside the farm, where the sheep could run free. Therefore, despite the early start with fencing, Wellwood farm as a whole was not enclosed until 1890.Footnote 44

The fencing of camps also followed a strategy, namely to fence the best and most productive grazing land first. That is why the mountain area on Wellwood was the last grazing land to be enclosed. The focus was instead on the lower areas on the farm that were better for grazing. But the fenced camps also received investments in the form of the planting of, for example, prickly pear and lucerne.Footnote 45 These plants were used as fodder and also prevented soil erosion, as a result of which the camps became even more valuable.

COMBINATION OF FARMING PRACTICES

Archer and Van Sittert both note that fencing meant that farmers could abandon kraaling, although Archer argues that herding continued in an “attenuated version” since farms were only boundary fenced, not subdivided into camps, and because of the threat from jackals.Footnote 46 We have, however, seen that farmers did not initially fence the boundary, but focused on creating camps. It was therefore not the lack of camps that caused farmers to continue to hire shepherds. The existence of jackals is a more likely explanation. John Frost, a farmer from Queenstown, explained in 1889 that the advantages of fencing were great, but not “quite so great as they would be if we could destroy all the vermin”.Footnote 47 The worst vermin was the jackal. Due to the “destruction by wild animals”, Frost noted that during the past years he had been “compelled for the first time since I have been living in the Queenstown division to kraal my ewes and lambs constantly”.Footnote 48 The jackals could not be kept out of the camps by using wires, which they easily dodged. Instead, netting fences, or jackal-proof fences as they were also called, were promoted by experts. However, these fences were not common in the nineteenth century. Jackal hunting was therefore the only solution available, an activity that was often the responsibility of shepherds and their families.Footnote 49 This was yet another task for shepherds in the Cape.

In Argentina, fencing reduced the demand for shepherds, but Sabato suggests that old practices of herding sheep were widespread, even after it had been introduced.Footnote 50 Even in the Cape, then, there may have been a period of transition from old to new practices. However, if we view the statistics, we can see that herding did not continue in an “attenuated version”, but rather it was intensified after the introduction of fencing. By the early twentieth century, it was clear that fences had not reduced the demand for shepherds – quite the contrary. The number of “shepherds or herds” increased during the last decades of the nineteenth century and reached 38,869 in 1891. Thereafter, the figure decreased to 34,093 in 1904, but again increased until 1911, when it totalled 42,582. To some extent, the number of “shepherds or herds” followed sheep numbers. But the ratio between them changed, so that in 1875 there was one herder for every 633 sheep, in 1891 one for every 430 sheep, in 1904 one for every 346 sheep, and in 1911 one for every 402 sheep.Footnote 51 The number of sheep per shepherd was slightly higher than indicated in these figures since censuses probably included herders of goats and cattle. Still, the trend was towards more shepherds, not fewer, being required to take care of the sheep.

The continued dependence on shepherds was also seen on Wellwood, where fencing activities were intensified in the 1870s. In 1880, there were at least six camps in use.Footnote 52 Despite the creation of camps, the old practices of kraaling and trekking did not end. In fact, new kraals were built or repaired in the late 1870s.Footnote 53 The number of shepherds on the farm consequently appears to have remained relatively constant, at about six, during the last decades of the nineteenth century, although in some years only three shepherds were mentioned.Footnote 54 During this period, the number of sheep on the farm was probably fairly static at 2,500, meaning that the number of shepherds cannot be explained by increasing sheep numbers or other stock. Explanations must therefore be related to the actual work carried out by the shepherds.

The work of the shepherds was not only to bring the sheep to and from the kraal at night and to guard them against vermin such as jackals. They also had to bring the sheep to water. While the sheep could graze in the camps and also spend nights there if they were jackal-proof, it was more difficult to bring the water to the sheep. In 1891, there were, for example, only 671 artesian wells and 508 wind pumps in the entire Cape.Footnote 55 Thus, the continued use of shepherds was also related to the lack of water resources in the dry Karoo and Eastern Cape.

Wellwood is an example of a very dry farm where there is no running water. In the late nineteenth century, water was provided mainly by dams, but there were a few windmills that pumped water. It was no coincidence that one of these areas, the “windmill corner”, was one of the first areas to be enclosed with jackal-proof fencing in 1896.Footnote 56 The areas with a mechanical water supply were highly prioritized by the Rubidges. Compared with dams, which were spread out in camps, the windmills created centralized drinking spots for sheep and probably supplied several camps with water. This attracted jackals. Therefore, investments in windmills would not be profitable unless they were also accompanied by investments in jackal-proof fencing.

LABOUR SUPPLY, INVESTMENTS, AND COMPETITION

Except for the disruption to farming during the Second Anglo-Boer War 1899–1902, wool exports increased around the turn of the century and reached one hundred million pounds in 1909. Most of the wool was exported to Britain, but other countries, such as Germany, also bought large quantities. However, despite the success with exports, wool farming was characterized by a stratification of farmers, which was seen in their ability to find labour. The state clearly sided with white farmers in their relations with black and coloured labourers. For example, the Masters and Servants Ordinance of 1841 and the Masters and Servants Act of 1856 criminalized disobedience and defiance and limited the mobility of the labour force.Footnote 57 The supply of labour was also something the state aided. Various Location Acts, which limited the number of black people permitted to stay on a farm without being employed, were implemented during the late nineteenth century to increase the supply of available labour. Further steps to increase the supply of labour were taken with the introduction of the Glen Grey Act of 1894, which aimed at dispossessing black peasants through restrictions on land ownership, although Richard Bouch argues that the process that forced peasants into wage labour was more or less completed by the 1890s.Footnote 58 Witnesses to the Select Committee on Farm Labour Supply in 1907, however, noted the importance of legislation for farmers. Arthur Fuller in Stutterheim explained that black people, “who have no land under the Glen Grey Act may be induced to come [as shepherds]”. But farmers would have to offer land for cultivation for the shepherd and his family and allow him to “run a certain number of stock”.Footnote 59 Family relations were therefore important and farmers could not find labour unless they also provided for the families of their adult male employees.

The supply of labour was not something that all farmers could exploit, however. After the discovery of gold in the 1880s, the mining industry attracted large numbers of peasants and farm labourers as migrant labour. In some districts, such as Queenstown, thousands of people left for the mines. These rural migrants were not always going to the Witwatersrand, though, mainly because of poor working conditions at that site. They instead favoured mines in Kimberly or South-West Africa.Footnote 60 While it was difficult for farmers to compete with mine owners for labour, they could utilize their livestock, which was as valuable as cash. The Resident Magistrate in King William’s Town noted in 1909 that the wages earned by labourers in mining were used to buy cattle.Footnote 61 By paying labourers in livestock, farmers could therefore attract labour in times of harsh competition. This explains the continued use of grazing rights and payment in livestock in the farming industry even long after the introduction of cash wages. Labourers wanted livestock, which could be used during marriage arrangements and to establish a homestead, and farmers were able to offer it. Sabato makes similar observations in relation to sharecropping in Argentina. She notes that sharecropping agreements were often preferred to cash wage labour since they meant access to a means of production in the form of sheep, offering independence and an opportunity to become established as a farmer if access to land could be found.Footnote 62 In pastoral regions, cash was therefore not always required in order to reach an elevated social position.

In the midst of competition for labour, investments in wool farming continued and even increased around the turn of the century. It made sense to invest, since windmills and fences were intended to replace labour. Investments in fencing clearly improved productivity in wool farming.Footnote 63 Between 1891 and 1904, the number of artesian wells increased from 617 to 2,168 throughout the Cape. During the following seven years, that number increased even further to 7,513. The number of wind pumps also increased, from 508 in 1891 to 2,516 in 1904 and to 4,671 in 1911.Footnote 64 Boreholes and pumps were most frequently seen in the Eastern Cape and the Karoo, where they were crucial to capitalist wool farming. Fencing also increased in the Cape, from 12 million morgen in 1904 to more than 19 million morgen in 1911. But the rate of fencing was slowing down. This was seen both in the Cape as a whole and, for example, in Graaff-Reinet, where 637,972 morgen was fenced in 1911, compared with 521,268 morgen in 1904 and only 190,276 morgen in 1891. However, this form of capital was unevenly distributed throughout the Cape. In wool-farming areas such as Carnarvon in the northern Cape, the amount of fencing more than doubled between 1904 and 1911, but reached 66,000 morgen only in 1911; this was one-tenth of the amount of fencing in Graaff-Reinet. The difference between the two districts is even more striking if we consider that in 1911 the total grazing area in Carnarvon was 1.6 million morgen, compared with 800,000 morgen in Graaff-Reinet.Footnote 65 By 1911, the central wool-producing areas had largely been fenced up. In more remote districts such as Carnarvon, farmers had apparently not been able to use profits from wool sales to invest in their farms, which consequently remained less profitable.

The ability to accumulate capital had an impact on the ability to attract labour. In 1909, the Magistrate in Carnarvon reported that the “poorer class of European farmers” had problems finding labour. The “more advanced farmers” had no such problems. The Magistrate suggested that the difficulties in finding labour were due to the fact that many black people had left Carnarvon. They had migrated to work in asbestos mines in Prieska, but the district had also been “drained of labourers to a considerable extent by farmers in the Fraserburg and Sutherland district, where it is reported they receive higher wages”.Footnote 66 So, migrant labourers did not favour mining per se, only the corresponding higher wages. As such, the so-called labour problems did not affect all farmers equally.

There were also examples of this stratification of farmers in Fraserburg. The wages paid to shepherds were between ten and fifteen shillings per month. There was a “constant demand for shepherds at that rate; in fact, labour is so scarce that Europeans are compelled to employ their little sons and daughters to herd the sheep”. Some suffered more than others. In the racialized language of the day, it was reported that it was an “exception, rather than the rule, to see a Native on the smaller farms”.Footnote 67 Apparently, then, the poorer farmers, who often resided on the smaller farms, were not able to exploit the labour of children of black shepherds and therefore had to resort to exploiting the labour of their own children.

On those farms whose owners invested in fencing, relations between farmers and labourers started to change. A Fencing Act, which facilitated the joint purchasing of fences, was introduced in 1912. The Act did not include netting fences, though, only ordinary fences, indicating that it was aimed at those farmers who had not yet fenced their farms. Progressive farmers such as the Rubidges were, however, creating more and more camps enclosed with jackal-proof fences. These had an impact on relations on the farm. By 1913, the number of flocks being herded on Wellwood was reduced to two, compared with about six in the late nineteenth century. One of the grazing areas where sheep were herded was located on “the mountain”, where fencing had begun to be installed in 1913. The mountain area was also the location of the stock belonging to labourers. Not even the foreman, Billy Hartzenberg, could negotiate to allow his stock to run free in the fenced camps.Footnote 68 The grazing rights of labourers were thereby limited, as they were in other places in the Eastern Cape. W.R. Warren in Stutterheim explained that “as sheep farmers or stock farmers it does not pay us to have natives mixed up among us because we know that they make depredations on our stock”.Footnote 69 Wool farmers were not interested in the produce of tenants and labourers, since the wool from their sheep was inferior to that from the sheep of white farmers.

INSIDE THE ENCLOSED FARM

By the second decade of the twentieth century, the Cape farms were increasingly being fenced in. In 1918, about forty-eight per cent of farms in the Cape were “wholly fenced” and ten per cent were “not fenced” at all.Footnote 70 Not all farms were enclosed with jackal-proof netting fences, however. The Fencing Act was amended in 1922 to include the joint purchase of netting. This signalled the government’s desire to help a large majority of farmers to introduce netting fences. We cannot measure with accuracy, however, the spread of netting fences in the 1920s. Netting fences were not enumerated separately until 1927, which, of course, is an indication of their spread by that point. By 1927, as many as 3,983 farms in the Cape were netted, compared with only 279 farms in the rest of the country.Footnote 71 Those 3,983 farms represented about eleven per cent of the farms in the Cape. A fairly small proportion of farms was consequently fenced with netting, but the rate was increasing.

By the 1920s, it was clear that some farmers had managed to follow the advice of experts and begun to graze their sheep in jackal-proof camps. Still, the implementation of fences was no guarantee that practices on a farm would change. D.H.R. Featherstone from Aberdeen explained: “There, inside his enclosed farm, the farmer still has his stock herded and the old work of loosening the soil, for the wind to blow and the rain to wash away, goes on just the same.”Footnote 72 So, there was a combination of farming practices, which caused damage not only to the wool, but also to the soil, because of the trekking of flocks back and forth to grazing pastures. But it was not only the distance to grazing pastures that caused problems for farmers. The water-supply issue was also an obstacle that had to be overcome by farmers wanting to expand their wool production and increase profits. The Drought Commission of 1923 explained that “the farmer loses much of the benefit of having abandoned kraaling, if his stock have still long distances to travel to water”.Footnote 73 According to the Commission, a lack of water supplies was particularly common in the North-Western Cape.Footnote 74

The mountain camp on Wellwood was enclosed in 1914, thus stabilizing the lower demand for shepherds. This did not mean that operations were carried out without labour, however. Once the mountain camp had been completely fenced in 1914, Sidney Rubidge employed a new type of labourer: “[h]ired single man Jacob for a months [sic] trial to live in hut in mountain camp & walk the fences every day”.Footnote 75 Jacob was the first so-called camp walker on Wellwood. This was a new position, which may explain why Rubidge treated it as provisional. Unlike the shepherds, who controlled animals, the camp walker controlled technology in the form of fences. The skills required by a camp walker were very different from those required from a shepherd, whose skills had been learnt through generations.

The same category of labourer appeared alongside the implementation of fencing in Australia. There, they were called boundary riders. McMichael notes that they had a much better economic position on farms than shepherds.Footnote 76 A similar pattern was seen on Wellwood. A man called Hermaans was hired as a camp walker on Wellwood in 1918. He had ninety goats and eleven donkeys when he and his seven family members arrived at the farm, which was a fairly large stock compared with most other labourers. Hermaans was hired at £3 per month, a higher wage than others were paid. But, in return for the higher wage, Sidney Rubidge demanded that Hermaans reduce his goats to thirty and that his donkeys would only be allowed to graze in the “outside veldt”.Footnote 77 For Hermaans, the agreement consequently meant that he lost two thirds of his stock and could graze his donkeys only in the “outside veldt”, a grazing area of lower quality than the camps. As such, in the Cape wool-farming areas, grazing rights did not change because farmers were in crisis, as Morris argues for agricultural farmers on the highveld.Footnote 78 The case on Wellwood exemplifies how farmers such as the Rubidges transformed production and sought to minimize labourers’ use of productive grazing land, instead restricting it to their own stock.

While the Rubidges were clearly in a capitalization process, Hermaans’ family was in a related process of proletarianization.Footnote 79 When he arrived at the farm, Hermaans agreed to let two of his daughters work for the Rubidges for cash wages and rations. That agreement was later renegotiated so that three of his daughters would work, for cash wages and no rations, demonstrating how the relations of exploitation changed from wages in kind to wages in cash. Presumably, the daughters were paid higher cash wages than the sum originally agreed, so the cash could be used to buy food, indicating how proletarianization impacted familial relations. But it also shows how the heads of families were forced to exploit the labour of their family more intensely when their stock was reduced and grazing was strictly limited.

The Rubidges were not the only farmers who hired people to attend fences. For example, Claude Orpen in Barkly East had “boundary riders to see that my fences are kept in order”; this was carried out on roughly a monthly basis. Alfred Sephton, also in Barkly East, similarly employed a man to control the fences, but this was conducted more frequently: “he walks this fence every day along the whole of the border”.Footnote 80 While the progressive farmers used boundary riders or camp walkers, it is unlikely that they were commonly utilized throughout the Cape, since jackal-proof fences were still unusual. According to Orpen, all farmers had camp walkers or boundary riders, but that probably reflects the situation in his district and not the Cape in general. Farmers who hired camp walkers or boundary riders also still hired shepherds. Sephton had 9,000 sheep and “I have a herd for every 800”,Footnote 81 i.e. about eleven shepherds. Most of Orpen’s sheep, however, ran free in netted camps, and consequently he had only a few shepherds.

ADRIJAN REID – THE LAST SHEPHERD ON WELLWOOD

The entire farm boundary on Wellwood was jackal-proof by 1920, as were probably most of the camps. Netting fences were efficient: it was to be another twenty-six years before a jackal was again shot on Wellwood. The demand for shepherds was further reduced due to the completion of jackal-proof fencing. There were two shepherds in 1918, but some time before 1923 one of them left. The one who remained was called Adrijan Reid, and when he left the farm in 1927 no shepherd was employed to replace him. He was therefore the last shepherd on Wellwood. The circumstances of his departure, however, reveal much about the character of the relationship between farmer and shepherd.

There were nine “main camps” on Wellwood in 1927. They were presumably all netted. There were also arrangements to provide water in these camps. One day in February, Adrijan Reid was found drunk by Sidney Rubidge and given notice to leave the farm. Reid had lost thirty-nine sheep while drunk. Of those, he found thirty the following day, but that did not change Rubidge’s decision. Reid was not forced to leave the farm at once, however. He left about three weeks later, and most likely worked during that time, which means that the decision to fire him was not taken due to concern for the well-being of the sheep. Other shepherds had previously lost sheep. For example, one shepherd lost 255 sheep on four separate occasions in 1895, but he had been allowed to stay.Footnote 82 Some labourers had also been found drunk and been allowed to stay. The difference between the situation in 1927 and those before was that the work of shepherds was no longer as necessary. In 1927, there were also investments in water supplies, further reducing the demand for shepherds.

After having given Adrijan Reid notice to leave, Sidney Rubidge appears to have changed his mind or devised a new arrangement for Reid. On the day that Reid left, Rubidge stated that “[h]e now prefers to break up all this sooner than accept my offer (made subsequent to giving him notice) to stay on homestead & be under my direct control”.Footnote 83 Apparently, Rubidge wanted Reid to stay on the farm, but in a different position. He would not continue as a shepherd, and was probably offered a position as a general labourer. Reid refused this offer. Reid likely valued the relative freedom afforded a shepherd, a freedom that would be largely lost if he were under the direct control of the farmer. His decision to leave the farm was facilitated by his ownership of stock. He left with seven cattle, twenty goats, and thirty-three sheep, most of which were merinos. Rubidge and Reid also settled the balance of £14 for wool sold by Reid some years earlier.Footnote 84 Reid’s participation in a corner of capitalist wool production thus improved his chances of finding a new place to stay. The sheep could be sold to a farmer, or he could shear the wool and sell it and earn some additional income. The £14 was more than the average annual cash wage for a family in the Eastern Cape in the 1930s,Footnote 85 indicating the importance of stock ownership for labourers. Ownership of stock, even in comparatively small numbers, provided shepherds such as Reid access to a means of production, and they could thereby resist the proletarianization process, or at least postpone full proletarianization.

NEW TECHNOLOGY AND NEW RELATIONS

New technology in the form of fences and windmills enabled farmers to improve production, with a better quality of wool and veld, thereby increasing their profits. The development and implementation of productive forces consequently transformed wool farming and labour practices, including the advent of camp walkers who controlled fences. In Australia, the introduction of boundary riders resulted in a more settled labour force and “social stability”, according to McMichael.Footnote 86 This did not seem to be the case in the Cape, where new technology created fresh problems for farmers, problems that the farmers had not anticipated.

On Wellwood, one man named Pyott [?] was assigned to “camp walking” in 1927.Footnote 87 In 1930, he was given notice to leave the farm “after again proving his unbelievable deceptiveness”. His work had apparently not been inspected, explaining why Rubidge sent the other labourers to inspect “fences believed to have been inspected by Pyott [?] […]”.Footnote 88 Another camp walker was subsequently hired, but he was fired within a few weeks. Thereafter, a man called Speelman was hired and stayed for about five months before Rubidge decided to also fire him.Footnote 89 Camp walkers and farmers did not seem to agree on how the work should be done.

Camp walkers not only controlled fences, they also reported on rainfall, water levels in dams, and other events in the camps. As they were constantly in the veld, they had significant responsibility. In the 1940s, Sidney Rubidge appears to have handed over all responsibility for fences to camp walkers. When the jackals once again showed up at the farm in 1946, he naturally blamed the camp walkers: the “fences not attended to for at least 20 years in spite of camp-walkers assurances over this period […]”.Footnote 90

When several sheep went missing in 1948, Sidney Rubidge gave the camp walker, Kleinbooi, notice to leave. According to Rubidge, Kleinbooi was “as big a scoundrel as a previous Gert Rafferty – 18 ‘unaccounted’ for sheep in past 6 weeks”.Footnote 91 Rubidge obviously thought that Kleinbooi had taken at least some of the missing sheep. Three weeks after Kleinbooi left, Rubidge noted that not one sheep was missing, “unlike when a camp walker or human jackall [sic] is heavily paid to daily patrol camps”.Footnote 92 The return of the jackals gave labourers an opportunity to steal sheep again and blame the jackals, which is exactly what Rubidge believed had happened. But in the following months he was forced to reconsider, when further sheep were killed and two jackals were caught. Rubidge did not admit to wrongfully accusing Kleinbooi, however. Instead, he blamed the camp walkers collectively for not doing their work properly: “Heaven only knows how many [jackals] have bred & grown up in that area the while my previous ‘Camp Walkers’ slumbered in the shades”.Footnote 93 By 1948, there had been camp walkers on Wellwood for thirty-four years. It is strange that Rubidge failed to hire people who conducted the work properly and that he left the control of fences entirely to the camp walkers. In other matters, Rubidge was in control of events, particularly when it came to soil erosion and water supplies.

To some extent, the new position created new relations on the farm. The work of shepherds was not supervised from day to day, but there were control mechanisms. The work of camp walkers, on the other hand, appears not to have been supervised for thirty-four years, if we accept Sidney Rubidge’s statement. The fences had been repaired during that time, so he must have been aware of their condition, at least occasionally. But that control was highly irregular and probably only occurred when something was apparently wrong. Small holes in the fence, or even weak points in the fence, for example where the ground was uneven, would not be detected easily unless the camp walker knew exactly what to look for. The extent of fencing on Wellwood, twenty miles of boundary fencing and thirty-six miles of internal fencing, made the work of camp walkers difficult and the supervision of their work was seemingly not a priority.

The new position of camp walker also indicates how the changed valuation of land impacted labour relations. As the camps were fenced and jackal-proofed, they increased in value for the farmer, who could graze his sheep at that site. At the same time, the labourers lost access to that same land, since their sheep were not allowed to graze in the best grazing area. The relationship between the labour force and the land in the fenced camps was transformed from one where the shepherds had a stake in the farm to one where camp walkers had only a monetary relationship in the sense that they were paid wages to control the fences. They also lost contact with the primary capital asset on the farm, the sheep. Unlike shepherds, who had daily contact with the sheep and knew their health, camp walkers had contact mainly with technology in the form of fences. The transformation of wool farming thus also changed the relationship between labourers and the land on which they worked. They lost access to the means of production, but gained monetary compensation and thereby took definitive steps towards proletarianization and became entrenched in the developing class of labourers.

THE GENERATIONAL DIVISION OF LABOUR REVISITED

The transformation of wool farming in the Cape during the first few decades of the twentieth century reduced the demand for shepherds on farms such as Wellwood, where netted camps were used to guard the sheep. But shepherds were still in demand on other farms, either because those farms were not subdivided into camps, or because they were not jackal-proof. We can use the census figures to analyse how the demand for shepherds changed during the first half of the twentieth century. In 1911, there were 42,582 “shepherds or herds” in the Cape. In 1946, there were 24,210. This reduction was not caused by fewer sheep numbers, quite the contrary. Sheep numbers increased during these years, from 17.1 million to 20.7 million. The ratio of “shepherds or herds” to sheep therefore changed, so that in 1946 there were 855 sheep per herder, compared with 402 in 1911.Footnote 94 The extensive fencing implied that even where shepherds were used, their work was facilitated by fencing, meaning that they could take care of increasing numbers of sheep.

For the country as a whole, an opposite trend was, however, noticeable until the 1930s. Between 1911 and 1936, the number of “shepherds or herds” increased from 66,758 to 104,483. The 1936 census did not enumerate the individual provinces, so we cannot say with certainty if this trend was also seen in the Cape. However, in 1946, the number of “shepherds or herds” in the country was reduced to 58,527 and there were 526 sheep per shepherd.Footnote 95 These figures indicate that the Cape was ahead of other provinces regarding the transformation of production. But it also shows that those farmers who did not invest in fences and the subdivision of farms were forced to hire more shepherds to compete. In 1936, there were 33.3 million sheep in the country, which meant that there was one herder to every 319 sheep.

While the shepherds in the Cape became fewer during the first half of the twentieth century, they were also younger compared with the early twentieth century. Statistics revealing the ages of shepherds are available for 1904, when 37 per cent were aged between 10 and 19 years old, and 25 per cent were between the ages of 20 and 40. In 1946, for the whole of South Africa, 87 per cent were between 10 and 19 and 6 per cent were between 20 and 40 years old.Footnote 96 As such, there had been a generational shift, which meant that more young children and youths had assumed shepherding duties.

We can see some different strategies in the hiring of children and youths on various farms. On Wellwood, there were two “youngsters” hired in the 1920s and 1930s. Since there was practically no demand for herding on the farm in the 1920s, they were not employed as shepherds, but conducted general farm labour and were hired on a yearly basis. But there were also youths, for example Hendrik and Cornelus, who were employed as day labourers.Footnote 97 Farmers such as Sephton and Orpen in Barkly East did not entrust young children to herd the sheep, at least not on their own. Regarding his shepherds, Sephton noted that he only “occasionally” hired a man under twenty-one years of age. Instead, he hired older people to herd sheep, since he found them “more reliable”. On Sephton’s farm there were, however, young children, “piccanins”, who worked and were paid seven shillings per month, about half as much as the adults.Footnote 98 The “piccanins” could have been employed as general farm labourers, but since herding was a task given to young people, it is possible that some of them worked as shepherds along with adults. Likewise, on Orpen’s farm the young shepherds did not work on their own. He noted, “Piccanins are not entrusted with flocks.” However, this did not mean that they did not herd sheep, only that they did not work alone. When discussing their wages, Orpen indicated the category in which children were counted: “The herds get 15s., with the exception of the piccanins, who begin on 10s.”Footnote 99

In other parts of the Eastern Cape, the practice of hiring children as shepherds appears to have been commonplace. The Inspector of Police in the Eastern Districts of the Cape Province, Colin Baines, stated that in Herschel, “the farmers generally engage small boys and pay them 3s. per month”. According to Baines, the wages paid to “native shepherds” ranged from 3s. to 10s. per month.Footnote 100 Such low wages indicate that a large part of the shepherding labour force in Herschel were children or youths. They were certainly not adult men with families. Consequently, there were those farmers who did not trust “piccanins” to herd sheep on their own, and those farmers who could not afford to distrust them. During the Depression, the wool price dropped and farmers’ earnings were severely reduced.Footnote 101 There must have been an increase in the incentive to hire children during this time, and it was probably utilized as a survival strategy by some farmers.

The impact of the mining industry should be regarded as a crucial explanation for the reduction in the number of adults in the shepherding labour force. According to the Native Farm Labour Committee of 1937, the disappearance of young males from farms was one important reason why farmers had problems attracting labour at the wages they offered.Footnote 102 However, many of these migrant mine labourers had families on the farms and returned from time to time as mining contracts generally lasted about nine months.Footnote 103 Those who remained on the farms were thus the youngest and oldest male members of the families, along with females of all ages. Very few of the young girls and women were involved in herding, but instead found employment as general labourers or domestics on farms. As shepherding was a male occupation, it appears that young males were given greater responsibility for herding sheep when their fathers and older brothers were at the mines. Young adult males did not shun shepherding per se, only the lower wages. As such, the resistance among young adult males towards working as shepherds for low wages appears to have resulted in intensified exploitation of familial relations among farm labour families. This was a revolutionary phase of child labour in South African history. No other category of labour has been so dominated by children and youths. Obviously, then, those farmers who did not have jackal-proof fences were not only compelled to increase their use of shepherds to compete, they also hired younger children who were cheaper than adults.

CONCLUSIONS

Existing research on wool farming has focused mainly on the implementation of fencing and not on labour relations. As a result, deterministic conclusions have been drawn regarding how the role of shepherds changed during the twentieth century. This article shows that the role of shepherds increased along with fencing in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Shepherding continued until farmers could provide both jackal-proof camps and sufficient water supplies. On a progressive farm such as Wellwood, the last shepherd left the farm in 1927. But long before that, a new category of labourer had replaced shepherds: the camp walkers or boundary riders. This category of labourer was more proletarianized than the shepherds. They earned higher cash wages, their grazing rights were limited, and they had mainly a monetary relationship with the farmers. On farms where less investment had been made, shepherding continued well into the 1940s. The generational ties among labouring families were exploited to a greater degree by those farmers who had not been able to accumulate enough capital to invest in fences. To compete, those farmers increasingly hired young shepherds, both because they were cheaper and because they were available on farms, while young adults became labour migrants in the mines.

A comparison can be made with Australia, where increasing labour costs underpinned decisions to fence earlier than in the Cape. In the Cape, competition from the mining industry clearly increased the cost of adult labour, and farmers instead turned to younger children. However, the lower labour costs, which were partly related to the availability of children and youths on farms as a result of family relationships, can explain only why some farmers were late to install fencing. We have seen that progressive farmers such as the Rubidges began to fence their farms in the 1860s. They could clearly have continued to hire shepherds at low cost, but instead they chose to improve production in search of profits. Fences could generate that additional profit. However, the environment in the form of jackals and poor water supplies delayed the impact of fencing on labour relations. It is therefore a simplification to say that low labour costs delayed fencing in the Cape. Instead, we must acknowledge that new technology contributed to a stratification of farmers into at least two groups: those who could profit and accumulate capital by using new methods, and those who tried to keep up by using old methods such as shepherding.

Thus, to add to the discussion started by Luxemburg and continued by others in South Africa, we can argue that capitalist production can both discard and reinforce pre-capitalist relations. The generational ties among labouring families were discarded by some farmers, but were increasingly exploited by others. Farmers’ attitudes towards such relations depended on whether or not they used new methods and technology or old practices, and to what extent they could attract labour. Here, we might note that remunerative practices did not change in the same manner. Wool farming was clearly capitalist in the mid-nineteenth century, but labourers were semi-proletarian. In this regard, the Cape was no different from Argentina, where the most efficient methods to further capital accumulation were the ones pursued. Payment in livestock and grazing rights was profitable for Cape farmers, particularly since it meant that they could spend cash on investments in technology and wages for fencers. When technology was in place, payment in livestock and particularly grazing rights was instead a burden for farmers, and a hindrance to capital accumulation. Some farmers could, at that point, discard semi-proletarian labour, but only when it was profitable to do so and when they were able to deny labourers access to land. The ability to do so was in turn generated by their success in accumulating capital in the periphery of capitalist wool production.