Introduction

Worldwide, female workers are significantly underpaid compared to their male counterparts.Footnote 1 Some governments are taking action to address this issue.Footnote 2. For example, in June 2017, Iceland became the first country to mandate a “Pay Equality Certificate” for employers, which requires proof of equal pay for men and women.Footnote 3 Compared with legislative efforts like this, the United States is falling behind other countries that are actively trying to reduce gender pay gaps.Footnote 4 In the United States, female workers earn on average $0.82 for every $1.00 earned by a man, which has been relatively consistent since 2004.Footnote 5 Experts anticipate that the gender pay gap will widen as the economy emerges from the COVID-19 pandemic because of its disproportionate impacts on women—particularly on women of color.Footnote 6

For decades, US federal legislation has attempted to address this issue. “Of all the significant unresolved gender equality issues, equal pay is one of the most vulnerable to the ebbs and flows of political will.”Footnote 7 Both the Equal Pay Act in 1963 and the Civil Rights Act in 1964Footnote 8 legislated equal pay. In 2009, the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act provided additional protection for female workers, primarily through clarifications of laws and judicial rulings already in place. In 2010, President Obama established the National Equal Pay Task force; in 2014, he signed two orders meant to reinforce equal pay for federal contractors.Footnote 9 Unfortunately, such legislative progress is inconsistent, as it largely depends on which political party is in charge in Washington. For example, the Paycheck Fairness Act, which aims to address loopholes in the Equal Pay Act, has never passed through Congress despite initially being introduced in 1997. President Biden recently announced that his administration will prioritize its passage. Though the House passed the bill in April 2020 for a second time,Footnote 10 the bill failed to pass the Senate.Footnote 11 Recent congressional trends have not been encouraging for those working to address the pay gap in the United States.

At the current rate of progress, equal pay will not be a reality for women in the United States until 2059.Footnote 12 Though governments play a role in advancing the economic status of women, buy-in by the public, which includes employers, is essential. Unfortunately, business owners are often hostile to policies regarding equal pay. For instance, a coalition of 27 business organizations recently lobbied to overturn an EEOC reporting rule targeting discriminatory pay practices.Footnote 13 Individual organizations also challenge efforts to address the pay gap. For example, US Soccer hired lobbyists to fight the US Women's National Team's claims that they are underpaid.Footnote 14 Such examples suggest that change will not be driven through organizational policy.

In short, attempts to address the issue of gender pay inequity appear to have stagnated across the political and public spheres in the United States. While policy change is often required for longstanding sociostructural changes, it is not always sufficient to cause social change.Footnote 15 The basis of the political will and public will (PPW) approach to analysis and actionFootnote 16 is that achieving long-term change around complex social issues—like gender pay inequity—requires complementary efforts by citizens and government. Key stakeholders must be willing to recognize the problem, understand the problem similarly, and agree on solutions.

Determining how to discuss gender pay inequity in ways that are meaningful to all stakeholders is crucial. The first challenge is framing an issue so that influential stakeholders are willing to engage in discussion.Footnote 17 To explore acceptable frames, this article opens with a discussion of the PPW approach and then focuses on work related to framing before detailing studies on perceptions of frames related to gender pay inequity.

Political will and public will approach

The PPW approachFootnote 18 pulls together multiple perspectives on the social change process to provide a flexible meta-framework for identifying shortcomings in political will and public will. This framework can be used to facilitate the application of appropriate tactics to build PPW.

• Political will exists when “a sufficient set of decision makers with a common understanding of a particular problem on the formal agenda is committed to supporting a commonly perceived, potentially effective policy solution.Footnote 19”

• Public will exists when “a social system has a shared recognition of a particular problem and resolves to address the situation in a particular way through sustained collective action.”Footnote 20

These definitions are meant to provide targets for assessment that can then be used to shift political will and public will.

Political will and public will are interdependent.Footnote 21 For example, legislation in the 1960s was not sufficient to eliminate the pay gap, likely because legislation (i.e., an indicator of political will) is not necessarily sufficient to effect change in opposition to public will. “The contention that gender pay equality is more likely to be achieved in more inclusive labour markets and societies implies that there are strong interactions across policy domains and mechanisms; action on one front may not be successful if it is not supported by complementary policies and reinforcing mechanisms.”Footnote 22 In the context of the PPW approach, a lack of shared understanding and problem recognition about equal pay in the larger social system (including employers and employees) may prevent the implementation of programs and policies that address gender pay inequity. Indeed, public opinion data suggests that many people in the United States do not believe a pay gap exists between men and women,Footnote 23 despite consistent data demonstrating that gender pay inequity exists in the United States and around the world. It is unlikely that the problem will be solved without a commonly held understanding of the issue.

Framing the issue of gender pay inequity

Identifying language with neutral or positive associations is crucial for success in addressing social problems as key stakeholders might not recognize a need for change until the problem is labeled in a certain wayFootnote 24 This requires framing the issue.Footnote 25 Numerous definitions of framing exist in the literature.Footnote 26 Framing broadly refers to “persistent patterns of cognition, interpretation, and presentation, or selection, emphasis, and exclusion, by which symbol handlers routinely organize discourse.”Footnote 27 Specifically, this study's approach focuses on frames in communication, or “the words, images, phrases, and presentation styles that a speaker uses when relaying information.”Footnote 28 Frames in communication can use emphasis framing. Emphasis frames are sometimes referred to as issue frames or value frames.Footnote 29 Though some scholarsFootnote 30 have cautioned against focusing on emphasis framing in favor of equivalency framing, the results of a recent meta-analysis suggest that the distinction between equivalency framing and emphasis framing does not necessarily lead to different impacts.Footnote 31 Though emphasis framing does not allow experimenters to isolate effects,Footnote 32 experimentally isolated effects are not the aim of this study. To understand how reactions to frames differ based on individual or group characteristics, competing frames should be presented to understand relationships between different frames and different effects.Footnote 33 Indeed, frame competition studies offer conditions more realistic to crowded information environments.Footnote 34

How an issue is framed in communication (i.e., labeled or discussed) can lead to framing effects, which are “behavioral or attitudinal outcomes that are not due to differences in what is being communicated, but rather to variations in how a given piece of information is being presented (or framed) in public discourse.”Footnote 35 Emphasis framing effects occur when individuals focus on a subset of potentially relevant considerations in forming their opinions in response to a speaker's emphasis of that subset of considerations.Footnote 36 Framing effects may move political will and/or public will on a topic like gender pay inequity, but the direction and degree of change depends on who is being addressed and their interpretations of the framing.

Viewing an issue as problematic is largely a result of social construction.Footnote 37 Therefore, how an issue like gender pay inequity is framed can affect people's perceptions of the issue.Footnote 38 Understanding interpretations of existing frames can inform one process for reframing social issues—breaking the old frame and amplifying a new frame.Footnote 39 Such counterframing can be difficult, and its effectiveness depends on a number of factors.Footnote 40 Choosing a frame with neutral or positive connotations can be an effective way to move forward on stagnant or controversial issues.Footnote 41 Such a frame will meet the sufficiency principle,Footnote 42 reducing debate about the rightness or wrongness of equal pay, thus providing a way to achieve pay goals while bypassing other issues.

Gathering data on perceptions of different ways of labeling a social issue can help identify frames that arouse emotional responses versus frames with neutral connotations. In the PPW approach, the goal of issue framing is to create shared recognition of the problem or issue. If a term is likely to invoke a negative emotional response from certain participants, choosing a different term might be a way to bring everyone to the table and have a productive conversation.Footnote 43 Individual and group characteristics help determine people's reactions to different frames; it is important to understand the relationships among these characteristics, frames, and effects.Footnote 44

Social bases can affect how individuals interpret and react to frames. Social-bases research considers how our background and experiences affect perceptions of social issues. Social bases are typically operationalized using demographic factors such as age, gender, ethnicity, education, and income as well as values indicators (e.g., political views).Footnote 45 Sex, age, education;Footnote 46 partisan motivated reasoning;Footnote 47 values;Footnote 48 and knowledge of an issueFootnote 49 relate to frame interpretation. Previous research on gender pay inequity suggests that a person's sex, Footnote 50marital status,Footnote 51 and parental statusFootnote 52 are associated with different perspectives on the importance of equal pay. Political affiliation and/or orientation also have demonstrable effects on stakeholders’ perceptions of pay equity.Footnote 53 Thus, identifying which social bases affect perceptions of frames for this issue is a necessary first step.

Based on the literature, our guiding research question was, “Do certain frames frequently used in public and policy discourse around the issue of gender pay inequity lead to different perceptions associated with social bases?” To answer this question, we completed two studies to identify, categorize, and test commonly used frames. Our pilot study enabled us to categorize and narrow down these frames. The main study tested these frames with a national sample. In the following sections, we explain these studies and discuss the results.

Pilot study

We began by identifying phrases commonly used to describe gender pay inequity and developing a questionnaire to measure reactions to those frames in communication. First, we conducted an extensive search of communication, marketing, management, sociology, and economics literatures as well as popular press to identify common terminology related to the topic. We identified terms by utilizing a comprehensive search tool that included articles from databases such as ScienceDirect Journals, Web of Science, Business Source Complete, Taylor & Francis Social Science and Humanities Library, Sage Journals Premier, Wiley Online Library, JSTOR Archive Collection, EconLit, and PscycARTICLES. To identify terminology used in popular press, we utilized the Google search engine. For both searches, we employed a range of pay terms until we found that subsequent searches produced no new terms. This effort yielded a list of 26 phrases.Footnote 54 Table 1 displays the list of 26 frames we initially identified.

Table 1: Twenty-six potential frames with descriptive statistics (pilot study).

s Frame selected for further testing.

Asking research participants to evaluate all 26 frames was untenable. Thus, an initial test was used to select a reduced set for further examination. Registered users of Amazon's Mechanical Turk (mTurk) from the United States read an IRB-approved description of the study before providing consent to continue and received $1.00 in exchange for completing a short (approximately 5-minute) survey. Participants (n = 406) were randomly presented with 10 words or phrases out of the possible 26; the number of participant responses per frame ranged from 141 to 184. Participants read frames one at a time and rated each in terms of discussing employee pay, on a scale of 0 (“strongly negative”) to 100 (“strongly positive”).

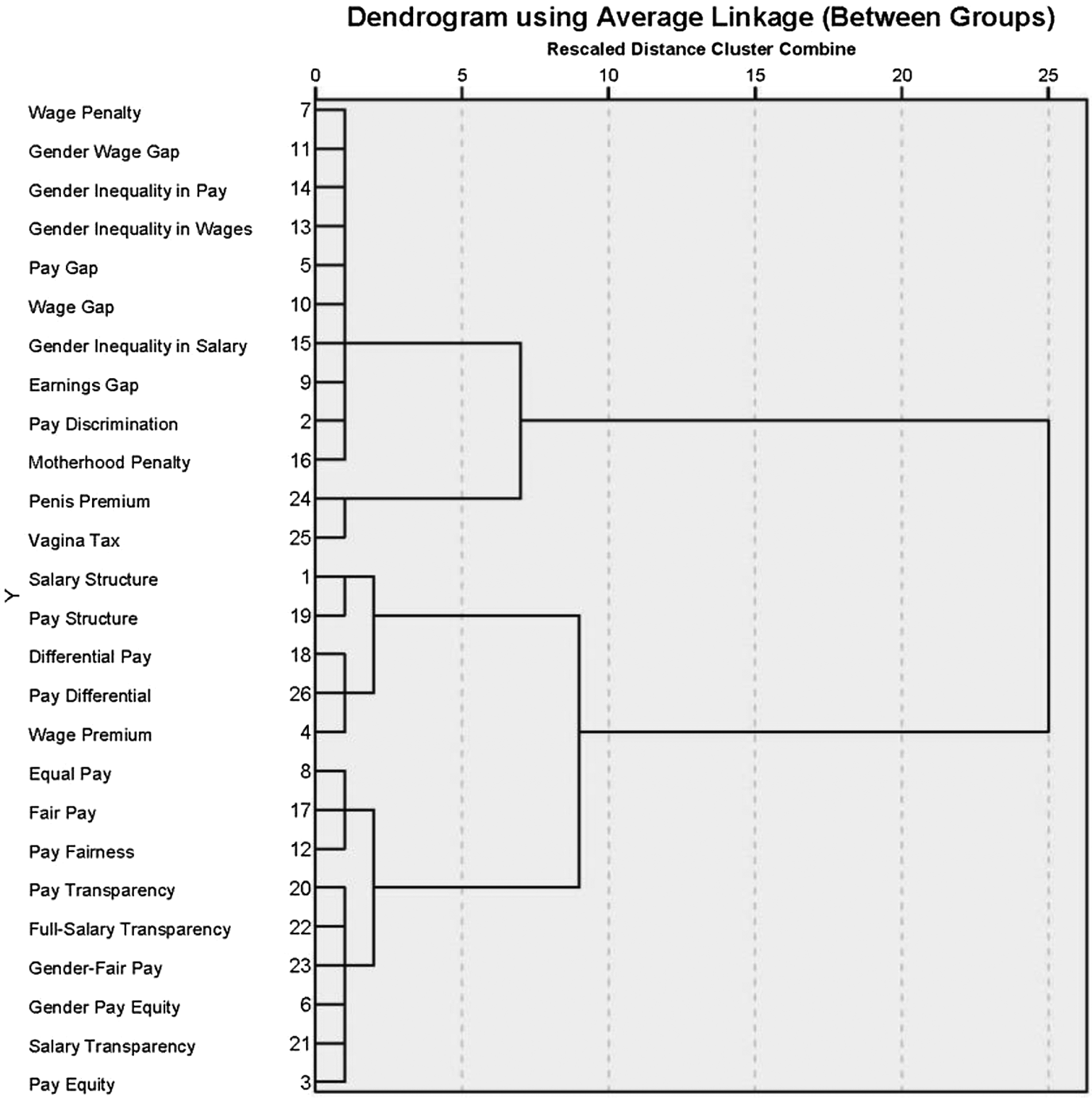

Table 1 displays number of responses, minimum, maximum, mean, and standard deviation for each frame. Mean ratings for each frame were used to conduct cluster analysis to group our frames in the interest of providing a more manageable list of frames for participant evaluation in our main study. The results of the analysis, which used Ward's method for cluster analysis and the Euclidean distance as a measure of distance between clusters (see Figure 1), suggested four clusters or larger groupings of frames. We labeled these clusters as deficit frames (e.g., pay gap), incendiary frames (e.g., penis premium), neutral frames (e.g., pay structure), and fairness frames (e.g., equal pay). Based on the cluster analysis, we selected 12 frames (marked in Table 1) for testing. These were selected to maintain a range of potential frames that included commonly used terms (e.g., equal pay) but also varied in words used, average rating, and cluster representation. We selected five terms from each of the two largest clusters (i.e., deficit frames and fairness frames) and one term from each of the two remaining clusters (i.e., incendiary frames and neutral frames).

Figure 1: Results of cluster analysis on potential frames.

Having identified frames for pilot testing, we next put them into competition with each otherFootnote 55 to learn whether framing effects existed across the frames and varied based on social bases. We selected variables shown to affect perceptions of frames generally and the issue of gender pay inequity more specifically. Sex, age, education, partisanship and values, and knowledge of an issue have been identified as affecting framing effects. We measured political ideology to capture partisanship and values. As proxies for likely knowledge of an issue, we asked about work experience, income, and marital status. Specific to gender pay inequity, previous research suggests that a person's marital and child-rearing status,Footnote 56 sex, and political affiliationFootnote 57 are associated with variance in their perspectives on the problem. Further, gender pay inequity is objectively linked with ethnicityFootnote 58 Thus, we collected this data to answer our pilot study research question: “Do social bases affect perceived acceptability of different frames used to discuss gender pay inequity?”

Pilot study method

We constructed a survey to measure sentiment reactions to 12 frames identified in our initial testing. Respondents were registered users of mTurk living in rural western states who read an IRB-approved description of the study before providing consent to continue and received $1.00 in exchange for completing the short (approximately 5-minute) survey. In addition to the sentiment evaluation, we included social bases/demographic measures (sex, age, education, employment status, ethnicity, marital status, number of children, household income, and political ideology). Participants read frames one at a time and rated each in terms of discussing employee pay, on a scale of 0 (“strongly negative”) to 100 (“strongly positive”).

Pilot study results and discussion

The initial sample size was 108 participants. After excluding responses from participants who signaled inattention or failed to complete the survey, the final sample size was 92. Participants were 54% female; 70% were 22–44 years old; 48% had a bachelor's degree or higher; 20% were employed for salary and 36% were employed for hourly wages; 56% earned $40,000 or more annually; 92% were Caucasian; 43% were married; 64% had no children; 28% of respondents identified as Democrats, and 25% identified as Republicans. Participants were, on average, at the middle of the political ideology spectrum (M = 4.61, with 1 as strongly conservative and 7 as strongly liberal; SD = 1.78). Descriptive statistics for all frames are provided in Table 2.

Table 2: Descriptive statistics for frames (pilot study).

Next, multivariate multiple regression analysis was performed. The ability to analyze individual characteristics associated with different frames was limited due to the small sample; however, the regression analysis of ratings across social bases yielded some differences. Though participants rated two commonly used frames (equal pay, fair pay) comparatively highly, these ratings were significantly associated with political ideology (see Table 3). Those who rated themselves as more liberal were more likely to view these terms favorably.

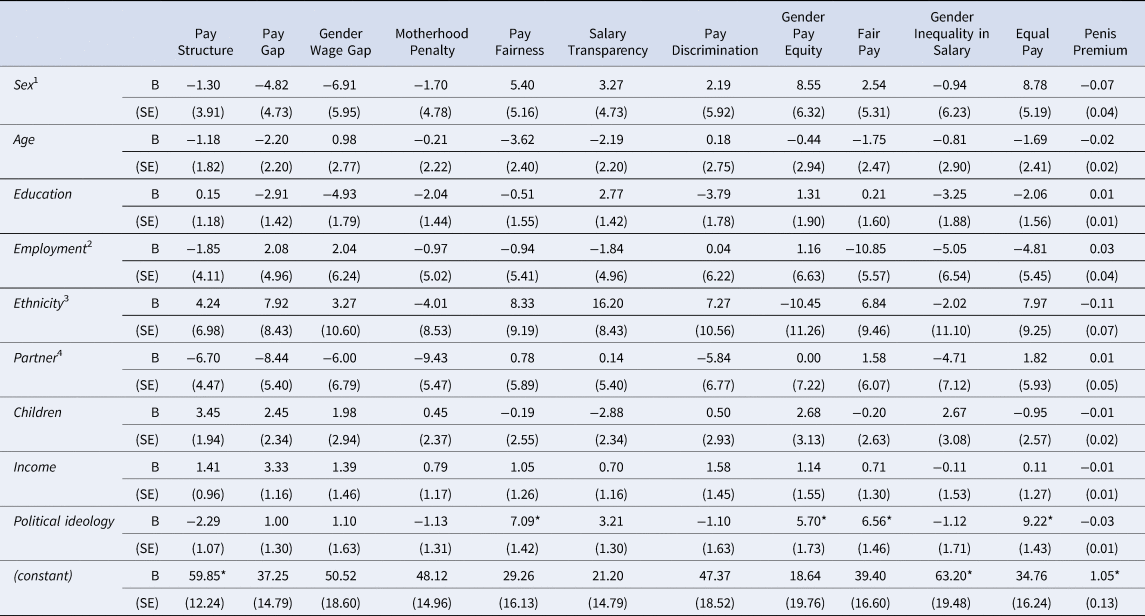

Table 3: Predictors of sentiment evaluations of frames (pilot study).

1 Sex was dummy coded into male (0) and female (1) for inclusion in regression analysis.

2 Employment was dummy coded as employed or not employed for regression analysis.

3 Ethnicity was dummy coded into two categories (white = 1, nonwhite = 0) for regression analysis.

4 This variable was dummy coded as partnered (married or living with significant other) or not for regression analysis.

* p < .001.

In the pilot study, political ideology was the only social bases variable consistently associated with differences in perceived acceptability of different frames and with the questions meant to evaluate the seriousness of gender pay inequity. These results suggest that commonly used frames in communication regarding the gender pay gap (equal pay and fair pay) are politicized. Thus, consideration of social bases—particularly related to political ideology—likely provides some insight into which phrases might provide an acceptable frame around which to build a public will campaign.

Main study

Our main study put terms used to discuss gender pay inequity into competition to examine how social bases relate to framing effects. Though our pilot study did not show significant effects for social bases other than those related to political ideology, the sample was relatively small. With a larger nationwide sample representing all 50 states, we evaluated the relationships between social bases and people's perceptions of frames and of gender pay inequity as a social problem. Our research questions asked:

Do (a) sex, (b) age, (c) education, (d) employment, (e) ethnicity, (h) marital status, (i) number of children, (j) income, and/or (k) income as percentage of household income affect (1) perceived acceptability of different frames describing gender pay inequity and (2) perceptions of the issue of gender pay inequity?

Based on the results of the pilot study, we hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 1: Political ideology affects (a) perceived acceptability of different frames describing gender pay inequity and (b) perceptions of the issue of gender pay inequity.

Main study method

We constructed another survey to measure sentiment reactions to 12 frames. Respondents were registered users of mTurk, who read an IRB-approved description of the study before providing consent to continue and each received $3.00 in exchange for completing the short (under 10-minute) survey. Using US Census Bureau data,Footnote 59 we gathered a sample that proportionally represented the population of each state by creating requirements in mTurk. In addition to the 12 frames, we included social bases measures (sex, age, education, employment and marital status, ethnicity, number of children, household income, and political ideology). Based on the pilot study results, discussions with business practitioners, and compensation textbooks and practitioner articles, we replaced penis premium (the incendiary frame) with strategic compensation practices, a frame that might appeal to a broader group. As in the previous data collections, participants read frames one at a time and rated each in terms of discussing employee pay, on a scale of 0 (“strongly negative”) to 100 (“strongly positive”). To understand participants’ views on the issue of gender pay inequity, we asked four additional questions. The first question measured estimates of the gender pay gap: “Using the slider scale, please indicate your answer (in US dollars) to the question below. If you believe men and women are paid exactly the same, choose 1.00. If you believe women are paid less than men, choose less than 1.00. If you believe women are paid more than men, choose more than 1.00.” Response options ranged from $0 to $2.00. The next three questions gauged perceptions of the importance of any gender pay differences; participants responded to these questions using a scale of 0 (“very unimportant”) to 100 (“very important”). “If a difference exists in pay between men and women (1) how important is this issue in US workplaces, (2) how important do you think it is to address this particular issue compared to other issues in the workplace, and (3) how important do you think it is to find a solution to eliminate pay discrepancies?” These three items measured perceptions of the importance of the problem compared to other workplace issues. Taken together, these items provided information on participant perceptions of the issue.

Main study results and discussion

The initial sample size was 1,747 participants. After excluding responses from participants who signaled inattention or failed to complete the survey, the final sample was 1,475. Participants were 52% female; 77% were 22–44 years old; 53% had a bachelor's degree or higher; 40% were employed for salary and 29% were employed for hourly wages; 46% earned $50,000 or more annually and were responsible for an average of 62% of household income; 75% were Caucasian; 39% were married; and 66% had no children. Participants were, on average, in the middle of the political ideology spectrum (M = 40.80, with 0 as strongly liberal and 100 as strongly conservative; SD = 28.45). Descriptive statistics for all dependent variables are provided in Table 4. We conducted both correlation and ANOVA preliminary analyses to look for relationships among variables and then performed multivariate multiple regression analysis. Regression results are provided in Tables 5 and 6.

Table 4: Descriptive statistics for frames and issue perceptions (main study).

Table 5: Regression results for frames and social bases (main study).

1Sex was dummy coded into male (0) and female (1) for inclusion in regression analysis.

2Employment was dummy coded as employed or not employed for regression analysis.

3Ethnicity was dummy coded into two categories (white = 1, nonwhite = 0) for regression analysis.

4This variable was dummy coded as partnered (married or living with significant other) or not for regression analysis.

* p < .001.

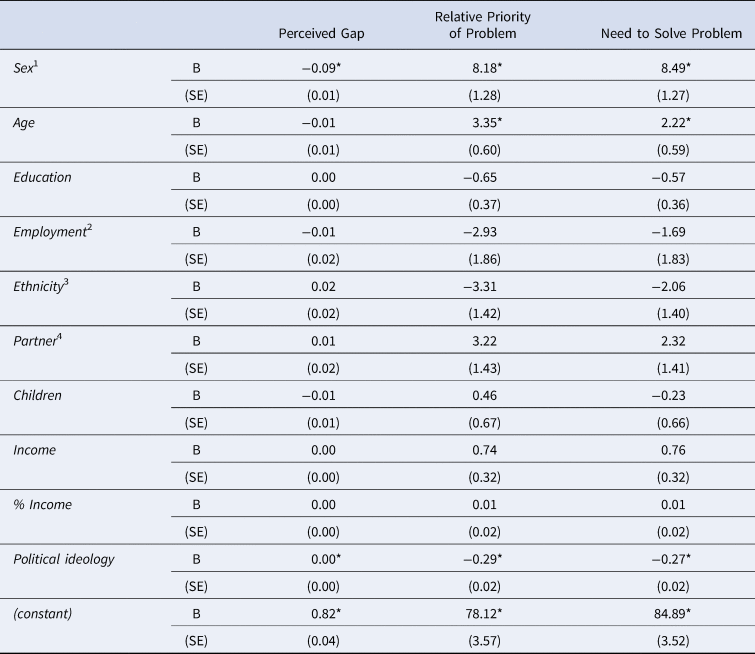

Table 6: Regression results for issue perceptions and social bases (main study).

1 Sex was dummy coded into male (0) and female (1) for inclusion in regression analysis.

2 Employment was dummy coded as employed or not employed for regression analysis.

3 Ethnicity was dummy coded into two categories (white = 1, nonwhite = 0) for regression analysis.

4 This variable was dummy coded as partnered (married or living with significant other) or not for regression analysis.

* p < .001.

In terms of our research question (RQ1), social bases (sex, age, education, employment, ethnicity, marital status, number of children, income, and/or income as percentage of household income) did not consistently predict the perceived acceptability of different frames describing gender pay inequity (see Table 5). Higher levels of education were associated with higher ratings of the frame salary transparency. Women rated the frame equal pay more positively. Higher incomes were associated with more positive ratings of the frame strategic compensation practices. Otherwise, these social bases were not significant predictors of acceptability of the frames.

Perceptions of the issue of gender pay inequity (RQ2) were associated with some social bases (see Table 6). Specifically, women perceived the gender pay gap as larger than men and rated the relative priority of the problem and the need to solve the problem as more important. Being older was also associated with perceptions of the priority of the problem and the need to address it. Otherwise, the measured social bases were not significant predictors of issue perceptions.

We predicted that political ideology (H1a) affects perceived acceptability of different frames describing gender pay inequity. Political ideology was a significant predictor of 7 of the 12 frames (see Table 5). Being more conservative was associated with rating the frames pay structure and strategic compensation practices more positively. Conversely, being more liberal was associated with rating the frames pay fairness, salary transparency, pay equity, fair pay, and equal pay more positively.

We predicted that political ideology (H1b) affects perceptions of the issue of gender pay inequity. Political ideology was a significant predictor of all three measured perceptions of the issues of gender pay inequity (see Table 6). Being more conservative was associated with the perception that the gender pay gap was smaller. Conversely, being more liberal was associated with believing that the problem was of higher relative priority overall and in higher need of solving overall.

Discussion

The overall highest-rated terms to describe the issue of gender pay inequity in both studies were fair pay and equal pay. However, evaluations of the acceptability of these terms varied. The biggest effects were consistently for political ideology. Fair pay and equal pay were preferred by those who self-rated as more liberal. In addition, political ideology significantly affected perceptions of the problem of gender pay inequity. Stronger liberal views were associated with perceiving the gap in pay between men and women as larger and perceiving addressing gender pay inequity and finding a solution as more important. More conservative participants tended to prefer frames from the neutral category, while more liberal participants tended to prefer frames from the fairness category. The results are consistent with our overarching prediction that both the issue of gender pay inequity and the commonly used frames discussing the issue are politicized.

Our results about the role political ideology can play in evaluating frames are consistent with previous findings. Though we labeled our larger category as “fairness” frames, many of these frames reference the concept of equality. Equality emphasis is perceived more favorably by liberals,Footnote 60 which is consistent with our findings. Partisan motivated reasoning is associated with views of frames as well.Footnote 61 Though we did not explore the partisan sources of the frames in communication we tested, further research could explore the influence of these frames when they are associated with specific partisan sources; partisan motivated reasoning theorizing suggests that this type of messaging might affect perceptions.Footnote 62 Given the strong association between political ideology and both the frames in communication studied and perceptions of the issue found in this research, exploring the link between partisan sources and views of both types of evaluations might be informative.

Other social bases did not emerge as comparably important in evaluations of frames or perceptions of the problem. Sex was not a significant factor in perceptions of frame acceptability. Perhaps not surprisingly, men estimated that discrepancy in pay is less than women did, and women see the issue as a higher priority in higher need of a solution. In terms of age, addressing the pay gap was viewed as a higher priority by older participants. Based on the results of the preliminary correlation analyses, frames from the deficit category were preferred by people who perceived the pay gap as smaller and the need to address the issue as lower; conversely, those who perceived the pay gap as larger and the need to address the issue as higher preferred frames from the fairness category. Taken together, these results suggest that those impacted more by gender pay inequity view it as a more significant issue.

The frames of strategic compensation practices and pay structure appear to be possible frames to engage members of the public who see the issue as less problematic and less important. In particular, strategic compensation practices was correlated with conservative political ideology but unassociated with perceptions of the issue of gender pay equity, which suggests that it might be a promising frame to engage people who have politicized views of the issue.

Our findings suggest that different public perceptions of both the problem of gender pay inequity and potential terms to discuss it exist. Raile et al.Footnote 63 acknowledge that different “publics” exist around policy issues and can influence policy making in different ways. In other words, some publics might view equal pay as a social justice issue while others might view strategic compensation practices as necessary for strong businesses. If multiple publics work to address the problem of gender pay inequity for their own reasons, the problem will still be addressed. Our results show that those who view gender pay inequity as a problem already wish to resolve it. If using a more business-centric frame helps expand the number of people working to address the problem, reducing gender pay inequity will still be the result of those efforts, which benefits all. Regardless of whether we discuss equal pay or strategic compensation practices, the ways to reduce gender pay inequity are the same. Shifting the frame to work with those who currently do not see a pressing need to address the problem seems to be a way to “unstick” this public policy issue. By adopting terminology regarding the gender wage gap that stakeholders perceive to honest and helpful, businesses, policy makers, and members of the public can respond empathetically to each other when discussing the issue, effectively utilizing the PPW framework to generate constructive solutions.Footnote 64 One encouraging finding from this research is that such conversations seem to be possible, provided that the participants use language that frames the issue in an honest, positive way.

Limitations and future research

In general, the use of a relatively large sample of adults provided the basis for analysis that could address this applied research question. Characteristics of the sample and the type of data collected were the two primary limitations of the study. First, our use of mTurk has known limitations. Though we worked to get a representative sample by setting parameters within our mTurk sampling procedure, the nature of the sample was limited due to the characteristics of mTurk users, who tend to be younger with higher levels of education.Footnote 65 We also followed recommendations for using mTurk, including use of a pilot test, data screening, short study completion times, paying above minimum wage, and setting parameters for our desired sample.Footnote 66 Future research should move beyond mTurk users; broader public polling procedures would be a good next step. Second, due to the use of a survey to collect sentiment ratings, the analysis was somewhat limited. An experimental design could be used to test receptivity to different frames in future research and potentially test the influence of partisan sources on perceptions of these frames. This limitation generates directions for future research and did not prevent a preliminary understanding of whether different phrases describing gender pay inequity vary in perceived acceptability. Third, focusing on frames in competition limited the generalizability of our findings. Future studies should ask participants to evaluate the impacts of these different frames in context following the model of more traditional, experimental framing research; for example, future studies could ask participants to respond to news stories using some of the different frames identified in this research.

Applications to research and practice

This study was guided by the overarching framework identifying PPWFootnote 67 as tools to implement policy in response to social problems such as gender pay inequity. Because policy efforts such as those outlined in the introduction have not been effective in eliminating the gender pay gap in the United States, the framework suggests that public will to address the issue might be lacking. And because addressing complex social problems starts with a common understanding of the problem among decision makers within the social system,Footnote 68 a lack of shared understanding and problem recognition may be preventing the implementation of programs and policies aimed at addressing gender pay inequity.

To develop shared recognition of this problem, stakeholders need to use a “similar frame and terminology for problem” and “converge in statements and beliefs about the situation and its causes.”Footnote 69 The results of these studies provide a first step in identifying phrases with positive associations for public stakeholders. In particular, strategic compensation practices and pay structure were positively perceived across participants in this study; this was especially true for strategic compensation practices, which was relatively highly rated even for those who did not see gender pay inequity as a pressing social issue. If these phrases can be used to help key public stakeholders recognize a need for change, progress might be made in addressing the issue. Discussing how businesses can enact strategic compensation practices, for example, might be less politicized than talking about how they can address equal pay issues.

Perceptions are important, and complex issues like the gender wage gap can legitimately be perceived in different ways.Footnote 70 The use of terms with more neutral connotations might be a productive way to start a constructive public conversation on this topic.Footnote 71 Relabeling an existing problem with another term enables stakeholders to reengage with an issue without losing face by appearing to change their minds.Footnote 72 This research provides valuable information to those looking to expand the conversation around pay inequity to drive social change. The results suggest that a careful choice of terminology may result in a more productive discussion of gender pay inequity in the workplace to strategically construct shared understanding within organizations and across the United States. Adopting terminology regarding the gender wage gap that stakeholders perceive to honest and helpful is an important step in motivating business practitioners, policy makers, and members of the public to reengage in discussions of the issue and generate constructive solutions to address gender pay inequity.

Authors’ note

Data presented in this multistudy paper was previously presented at the annual American Marketing Association, Marketing & Public Policy Conference (2016), International Communication Association Conference (2018), National Communication Association Conference (2015), and Western Academy of Management Conference (2017, 2020).

Acknowledgment of financial support

Funding from Montana State University and the Women's Foundation of Montana supported this research.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.