How far do the workings of the state impinge on our daily lives? We can certainly interpret the presence of the state by evaluating the grand vision and rhetoric of the regime, gauging the impact of its policy on our well-being, or reflecting on the implications of its legislation on individual freedom. State-ness is, however, also a matter of encounters in everyday life, as argued by Rudolf and Jacobsen.Footnote 1 State authority is mostly experienced at grassroots level where agents of the state interact intimately with the citizenry. Legitimacy of the state thus appears, as Luigi Tomba argues, “as the consequence of one's assessment of the acceptability of everyday governing practices and of the moral discourses that justify such practices under a variety of material conditions.”Footnote 2 This grassroots perspective is quintessential for students of Chinese politics as it reminds us of the basic fact that ordinary people see these local officials, not only as part of the state or cadres but also as neighbours, kin and friends.Footnote 3 The state boundary is thus blurred and fluid and its authority is very much perceived and evaluated on the basis of its agents’ success in adapting to changes in local socio-economic landscapes and addressing local concerns. This is particularly the case for rural China, where local cadres, as depicted in the authoritative work of Vivienne Shue, are “far from serving as robotic maidens of central domination”Footnote 4 but are more vulnerable to the pressure of the moral community in a local setting. Traditional authority over rural society, as argued by Pransenjit Duara in his seminal work, must be embedded in the local cultural nexus that is expressed in norms and symbols encoding indigenous “religious beliefs, feeling of reciprocity, kinship bonds and similar sentiments that are often deeply held by, and often deeply hold, the people participating in the organizations (of authority).”Footnote 5 Positions of local authority devoid of this symbolic capital can be hollow and precarious and “state involution” – the concomitant developments of expansion of state size and proliferation of local disorder, is thus possible.Footnote 6 Local morality, however, is malleable and elastic and can, for example, be reshaped by a transformation of the physical world. The residential pattern, in particular, is instrumental in shaping a new code of social ethics. James Scott sees housing arrangements in pre-reform China as having been deliberately intended to serve as a “social condenser” under the socialist regime – a means to create a new form of social relationships, akin to its ideal, through spatial design.Footnote 7 Communal living was designed to supersede the bourgeois family pattern; and the shared facilities, such as kitchen, laundry and childcare services, were promoted to facilitate the production of proletariat subjects and to destroy traditional social relationships. Mao's danwei 单位 compounds were, in short, not simply results of the economic shortage and austerity campaign of the new People's Republic in its early years; these housing projects were, according to David Bray, also attempts “to symbolize and reproduce in miniature the order of the socialist state and to promote a socialist collectivized lifestyle among its resident members.”Footnote 8

A no less seismic change in the residential pattern is emerging in rural China today: the rise of peasant apartments. Chinese peasants have been abruptly uprooted from their customary residence and ways of life. Traditional rural houses have been quickly erased from the face of the countryside with large numbers of peasants being relocated to modern high-rise buildings. In fact, the number of rural villages has been steadily decreasing, from 594,658 in 2010 to 585,451 in 2014. Meanwhile, the number of sub-districts (jiedao banshichu 街道办事处) under township administration has rapidly increased from 6,923 in 2010 to 8,105 in 2016.Footnote 9 There is undeniably a reconfiguration of spatial and administrative order in rural China today. Based on our fieldwork, we argue that the process of “peasant elevation” has had a monumental impact on rural China. The process of relocating peasants redefines the terms of entitlement to land use by the rural citizenry and negotiations for a new regime of property rights concerning land administration, while, most importantly, it could have potential impact in undermining the position of the local state in rural China, whose authority is an aggregation of three distinctive elements: coercive power inherent in the state apparatus, control over economic resources, and resonance with local morality. Whereas the backing of the central state has by and large remained intact, the last two sources of power have been significantly weakened by the moral disorientation of affected peasants and fragmentation of local authority inherent in the relocation process, and the consequent tardiness in the formation of new community identity.

The following discussion is based on findings from our fieldwork in Chongqing重庆, Nantong 南通 in Jiangsu province and Dezhou 德州 in Shandong province conducted between August and September 2014. While we are content with the humble objective of shedding light on important changes in the political and socio-economic landscape in rural China triggered by the phenomenon of peasant elevation, and are particularly conscious of the danger of over-generalization from a limited number of cases, the three cities were carefully chosen on the basis of several key considerations. First, steady implementation of the relocation policy is evident in the three locations for at least two years before our visit and thus the impact of spatial change is more discernible. Second, as the existence of a vibrant non-agricultural economy is imperative to the implementation of the relocation scheme, the cases must demonstrate strong economic performance: all three economies had witnessed 9 to 10 per cent growth rate in GDP, predominant secondary and tertiary sectors (85 per cent or above) and an above-national average of per capita GDP by 2014.Footnote 10 Third, for practical considerations, personal connections with local officials are essential for maintaining maximum flexibility and freedom in carrying out our fieldwork.

A survey of rural households was implemented in eight counties and districts in these three cities.Footnote 11 A total of 882 questionnaires were completed, and interviews with 53 peasants and 14 local cadres were also conducted during this period. All questionnaires were completed on a face-to-face basis by members of our research team. The peasants chosen for interviews were of different ages, family size, economic status and income level.

Peasant Elevation: Policy, Rationale and Implementation

The phenomenon of peasant elevation, or as Chinese scholars call it, “peasants going upstairs” (nongmin shanglou 农民上楼) is primarily the result of the local governments’ hunger for revenue in rural China. There is general consensus that local finances have been severely hit by fiscal reforms since 1994 and most county and rural administrations in particular have been struggling to locate extra revenue to balance the books.Footnote 12 Rural land turns out to be the most accessible and valuable resource for this purpose. Meg Rithmire argues that this is a result of “the bargaining” between central and local government, with the former deliberately delegating power over land and access to land-related revenue downwards, thus providing local administrations with an alternative source of fiscal resources following the heightened control over investment and tax collection by the central government since the mid-1990s.Footnote 13 Feizhou Zhou and Shaochen Wang have identified three possible approaches in this regard. First, revenues can be obtained from the sale of land or in the form of tax payments by leasing the plots to investors. Second, land can also be used as collateral for bank loans whereby this injection of capital can hopefully provide more economic impetus and generate revenue for local administrations.Footnote 14

The third approach of generating revenue from peasant elevation is, however, much more sophisticated and innovative. Central to this approach is the transfer of construction land quotas (jianshe yongdi zhibiao 建设用地指标). The construction land quota system was introduced in 1998. The motivational factors behind this policy are to maintain the national government's macro-control over land usage in the country and, more importantly, to arrest the trend of the decrease in farmland due to the rampaging process of urbanization during the reform era. Under the quota system, each province is assigned a maximum area of land for construction usage for a specific period of time, which in effect exerts a brake on the pace at which the urban boundary of each local jurisdiction can expand. Nevertheless, the quotas were quickly consumed by the insatiable demand for space in urban areas, and in most cases illegal construction works on farmland and other forms of violation were prevalent. Guangzhou, for example, had used up 95 per cent of its designated quota of 1,772 hectares of construction land for the period of 2010 to 2020 by the end of 2013.Footnote 15 The central government, however, found itself in a predicament. While it was keen to maintain regulatory control over national spatial development, the danger of governments becoming bankrupt was genuine if they were to be completely deprived of land supply for urban construction. As a compromise, a compensation scheme was devised to help alleviate the tension between the need for local development and national control. Eventually formalized as the “linkage of quota usage scheme” (zengjian guagou 增减挂钩), the idea is that, if savings in construction land use can be achieved in a rural area, construction on a plot of the same size in an urban area is permitted. In 2005, seven provinces and a municipality directly under the central government were chosen as test areas for experimenting with this scheme. Another batch of 19 provinces were included in 2008. The national government's four-trillion yuan economic stimulus package triggered by the global financial crisis in 2008 simply added extra fuel to the craze for development projects across the countryside. In order to benefit from the windfall of financial subsidies, local governments were desperate to secure space for infrastructure and property development. Savings in construction land usage in the countryside hold the key to success in this scramble for funding.Footnote 16

So, how can “savings” be achieved? Here, the relevance of the peasant apartment comes into play. Under the household contract system, each rural household is guaranteed a 30-year lease of a plot for farming activities as well as a piece of land for residential use.Footnote 17 However, the residential plot (zhaijidi 宅基地) is classified as construction land under the official categorization system. Thus, if the local administration can find a way to remove the family from their current residence and convert the plot into farmland, a saving in the construction land quota can be generated. The newly created quota of construction land can then be used to justify a new construction project occupying the same amount of space in the urban area, where the land value is much higher. The provision of peasant apartments is therefore instrumental in the implementation of this scheme. Just imagine you are trying to create new quota from a village where there are 20 rural households. Let us say that the average size of each farmhouse is 100 square metres and thus the total construction land consumption before relocation is 2,000 square metres. If you build a 20-storey building with an apartment on each floor 100 square metres in area and move the 20 households into these units, you can immediately create a saving of 1,900 square metres of construction land usage after all the residential plots have been transformed into farmland. Peasant elevation is thus the key to the new developmental strategy of local government. Simply by stacking up rural houses, the opportunity for development and revenue is unleashed.

Enticing Peasants to Move

However, this perfect scenario hinges upon one thing: peasants’ consent to relocation. Given the numerous reports of violent resistance to the loss of land in rural China, how can we expect a different response to the prospect of “elevation” from the Chinese peasantry? There are several major incentives for accepting the relocation offer. Of greatest attraction is the opportunity to live in a modern apartment in a newly constructed high-rise building. The general arrangement is a “flat-for-flat” compensation scheme that allows a rural household to move into a new unit at a highly subsidized price. Most peasants find the prospect of moving into the new residence alluring as the comfort provided by the new apartments is appealing. In most cases, they are equipped with a steady supply of heating, electricity and gas. The tile-covered floor in the apartment and the garbage collection service in the new community also guarantee a better state of general hygiene when compared with the old habitat. The price of the new apartment is also attractive. Depending on the size and specific condition (for example, floor location and view) of the new unit, the affected household usually does not have to pay much cash as the value of their residential plot mostly covers the price of the new apartment. One relocated peasant in Nanchuan district 南川区 in Chongqing exclaimed:

The price of commodity property (shangpingfang 商品房) is 2,700 to 2,800 yuan per sq. metre in nearby areas and we are only charged 1,700 yuan for the new apartment. This is a very big discount!Footnote 18

Even more importantly, some relocated peasants are entitled to buy more than one unit, so the extra apartment can, in theory, be sold on the market in the future. For example, in Banan district 巴南区 in Chongqing, if a household is compensated on the basis that each member of the family is entitled to buy 30 square metres of space at a subsidized price, a household of five members is entitled to buy a new unit of 150 square metres. They can either buy a big flat of this size, or two smaller ones. In many cases, particularly those families with small children, the latter option is preferred as they can lease out the extra unit for rental income and hold on to the second unit until the policy on re-sale is finalized.Footnote 19 Relocation thus enables the transformation of an entitlement to an idle asset into a steady stream of income or a one-off fortune. The feeling of satisfaction, however, is not only confined to the material aspect or improvement in living conditions; it also relates to the sense of pride of living like an urban resident (chengliren 城里人). “Our life may not be 100 per cent the same as the one enjoyed by the urban people but I think it should be 60–70 per cent,” a peasant in Chongqing enthusiastically responded when asked about the change in the quality of life after moving into a new apartment.Footnote 20

In order to expedite the process, local administrations usually offer urban hukou 户口 and its attached entitlement to social security benefits for the surrender of land leases (gengdi huan shebao 耕地换社保). For example, in the Tongzhou district 通州区 of Nantong, members of rural households are offered compensation for the loss of farmland according to their age and gender as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Benefits Offered as Compensation for Farmland Scheme in Nantong

Source:

Authors’ interview, Nantong, 12 September 2014.

The prospect of off-farm employment is another important consideration in relocation. Unleashing new space through peasant elevation always entails a concomitant injection of capital into the rural area. In most cases, builders assigned the task of constructing new houses for the relocated peasants are also given a lease of land for other commercial purposes in the area. This is a common form of leverage used by local administrations when negotiating the construction cost of peasant apartments. Resorts, hostels and other hospitality businesses are the most popular projects set up by these investors and, in turn, these ventures require local labour for their operation. Alternatively, peasants may take on waged labour in newly set-up agribusinesses in the neighbourhood. These income opportunities are particularly attractive for older peasants as they may find job-seeking in cities too challenging a task.

The decision to move out is not always entirely voluntary though. Persistent pressure and even coercion by local cadres are not uncommon. The minority who are reluctant to relinquish their farmhouses are eventually left with little choice but to accept the offer. Local cadres can resort to all kinds of underhand measures to make the life of the few stubborn householders untenable, for example, cutting off the supply of electricity, blocking village roads or pouring unpleasant substances into wells and streams. In short, Chinese peasants are rapidly pushed and pulled out of their traditional farmhouses and relocated to modern apartments in newly constructed high-rise buildings.

Strengthening of Market Logic

The change in residential pattern in the countryside does, however, have major implications for the moral dimension of rural life in China. In short, the process has a tremendous effect on three aspects of peasants’ integration into a capitalist market economy: production, consumption and pattern of social exchange, which in turn have aggravated the sense of vulnerability in the local community and affected its relationship with local cadres.

Production and consumption

Our findings show that the surrender of residential plots and the abandonment of farming are intertwined in the relocation process. The average size of land farmed by rural households before the relocation was 4.66 mu 亩; this figure dropped to 2.36 mu after householders had moved into the apartments.Footnote 21 Farmland has been either sublet to outsiders or left idle. We visited the Banan district of Chongqing where the company X that had obtained the construction contract for new apartments in the community had also secured a lease of 2,000 mu of farmland from the relocated peasants for their flower business. The annual rental fee was fixed at 750 yuan per mu. “These business people just use these flowers as decoys,” a local cadre told us.Footnote 22 “They will turn this land into a hotel or property development business once the attention from higher up wanes,” he explained. Regardless of the fate of the farmland, most peasants turn to waged labour as migrant workers or become entrepreneurs, or they simply rely on rental income for subsistence. These three sources of income contribute more than 60 per cent of the rural household incomes of our respondents.Footnote 23 Their well-being is now more dependent on the availability of jobs, profit or income opportunities interconnected with the cyclical fluctuation of the market economy instead of the rhythm of nature and weather.

Further integration into the market system is reflected in the changing consumption pattern of the relocated peasants. “We can no longer grow our own food” is the most common complaint of those being “elevated.” It probably takes great perseverance and determination to maintain an involvement in farming after relocation. The cost of operating simply works against the idea. While, before relocation, most farms were adjacent or very close to the residence, the average distance between the new apartments and the retained farms is 3.69 km, according to our survey findings. In one extreme case, the distance is 48 km. For most communities where public transport services are few and far between, this is hardly a walkable distance, or it may entail a substantial cost in using private transport on a daily basis. For those who want to continue farming, the new spatial order also deprives them of space for storing tools and processing produce. One peasant in Chongqing voiced his frustration:

In the past, I could raise some animals and grow some vegetables to feed my family, but I don't have the conditions to do this now. I had 15 pigs before. Now I have none.Footnote 24

As a result, most relocated peasants have to buy food from a nearby market or local stores. In other words, the traditional self-sufficiency of the rural household is no longer maintained and the most basic needs now have to be met by cash. This translates into a rising cost of living for the rural household. Of our respondents, 73.5 per cent complain about the increase in the cost of food after relocation. Subsistence in rural neighbourhoods is thus no longer a matter of labour, fertility of one's plot and knowledge of the local habitat and weather conditions. Instead, access to food is now primarily determined by level of income and market supply, and can only be secured by consumption power mediated in the form of cash.

Social exchange

The most significant impact of marketization on rural life, however, is its effect on the pattern of social exchange. Yunxiang Yan and others have highlighted how social interactions – for example, pooling of resources and mutual help – have been replaced by monetarized exchange, thus undermining the moral bonding of the rural community.Footnote 25 The changing residential pattern resulting from the elevation process has simply exacerbated this trend. The new spatial order inherent in the relocation process has deprived the rural community of room for performing traditional rituals and social etiquette – acts that are crucial for maintaining moral bonding at the grass roots. The impact of the changes on the social fabric is best reflected in rituals such as funeral arrangements. Death ritual is a good illustration of social exchange and obligations in rural society. As Ellen Oxfeld contends, “a funeral is not only an event in which filiality is on stage, but also an event where a family's dealings with the community at large are paramount.”Footnote 26 Mutual assistance and the pooling of resources in helping relatives of the deceased during this emotional event used to be the norm in Chinese rural society. Traditionally, there are specific requirements with respect to the location of the coffin and duration of the ceremony. The spatial constraints inherent in the new living arrangements, however, render strict adherence to these rituals impossible. Instead of placing the coffin in a specific direction for an extended period (usually a week), an abridged version of the ceremony is now common practice. In most cases, the body of the deceased is kept in the basement of the building or in a temporary shed installed in the playground. Unlike the relatives who are probably highly tolerant of the inconvenience and disturbance related to the elaborate rituals and ceremonies, people are now conscious of the nuisance caused to their new neighbours. Consequently, these days, funerals in these new communities are mostly handled by hired professionals. The so-called “one dragon service” (yitiaolong fuwu 一条龙服务) – a full package of music recital, ritual performance, meals and other related services – is provided by funeral organizers rather than sympathetic relatives and friends. The ceremony is now a less elaborate business, devoid of much social content when compared with the traditional practice, which epitomized moral bonding and community solidarity. Social exchanges have been gradually replaced by commodified arrangements.Footnote 27

In short, under the new spatial order, market exchanges have steadily replaced the priorities of entitlements and social bonding, while the language of efficiency and competitiveness has prevailed over talk of rights and collective provisions.Footnote 28 This may imply opportunity for enrichment and prospects for social mobility, but it may also beget a sense of insecurity and helplessness. With the fallback option of farming and other land-related income source no longer available for most after relocation, the rural population concerned is fully exposed to the vacillation of market conditions and the peril of price fluctuation. This heightened sense of insecurity may prompt the local community to be more dependent on local cadres, whom they have seen as frontages of the state and are believed to be obligated to provide support for the local community in times of adversity. The question is, can they help?

Impact on Moral Order

Ordinary peasants experience the presence of the state mostly through their encounters with community officials at a grassroots level. Village cadres represent the face of state authority, through whom power is mediated, negotiated and contended. Their relationship with the local community is primarily defined by the exercise of three kinds of power: political, redistributive and moral. First, despite the low ranking of village cadres at the bottom of the state apparatus, they are backed up by state-sanctioned coercive power, and subservience and compliance with their instructions are expected, or else penalties will be inflicted. It is, however, very difficult for village cadres to command respect from, or be even relevant to, the local community if they fail to contribute to the material well-being or affect the income opportunities of individual peasants. Decollectivization and market reforms in the post-Mao years have certainly diminished their redistributive power. “No money, no service, no authority,” an account of local authority, vividly portrayed by An Chen, underlines how a shortage of funds and a reduction in the provision of public goods have contributed to the general decline of authority at the grassroots level.Footnote 29 Yet village cadres’ authority over land administration and collective assets can still enable them to shape the distribution of wealth and income on the local scene.

However, the redistributive power of village cadres does not automatically increase their authority if they cannot win the trust of their fellow villagers. The demarcation between state and society at the grassroots level is always amorphous, with the boundary best described as blurred and porous, argues Philip Oldenburg. “Those who are part of the state are, at the grass roots, often one's next-door-neighbour, a person who as often as not works for both the state and privately, often mixing the two,” he argues.Footnote 30 Ben Hillman also contends that local cadres’ ability to mobilize their local social networks is instrumental to the party-state resilience in the countryside, while astute leaders are keen to build on kinship ties, friendship, religion or any other form of community bonding to augment their authority in the village.Footnote 31 In short, in addition to the backing of the regime, the status of cadre as a member of the local community – someone who shares a common ethos, values and nostalgia with local folk, and who is accepted as sincere and committed to serving the interests of fellow villagers – is the most important basis of village authority in rural China. The elevation process, however, entails an unintended consequence of undermining the prospect of formation of cohesiveness in the newly created community.

In addition to the intensification of market logic in rural life and the consequent sense of vulnerability, the change in the residential pattern and spatial order turn out to have had a major impact on the bonding and identity of the relocated community as well. The spatial impacts are expressed in several major ways. First, the pattern of allocation of apartments has a major impact on the emergence of a common identity in the new neighbourhood. In most cases the intention to transfer the whole village en bloc to the new premises is compromised by administrative and logistical considerations. Most Chinese peasants populated the realm of a natural village (ziran cun 自然村) where they shared kinship linkages and collective memory for decades. Members of the same village, however, may have decided to move into the new apartments at different times, and some may take more persuasion than others. Differences in the preference for size, floor level or outlook of the units may also render the arrangement of putting the whole natural village into the same building impossible. In addition, the overall scale of the relocation project also matters here. In places like Nantong, where new housing complexes are usually intended to accommodate tens of thousands of affected peasants, administrative expediency and efficiency always prevail over social and emotional concerns of the residents. The merger of peasants from different villages on the same floor or in the same building are not uncommon. The new logic of organization based on a block or a floor may render formation of community identity in the relocated setting difficult. A cadre in the new neighbourhood recalled:

Many people still see themselves as members of the original community and confine themselves to their old friends and folks. We always tried to organize some social events during traditional festivals in order to strengthen the bonding in the new neighbourhood. We once asked everyone in the building to come down to the basketball ground for some celebration during Chinese New Year. In the end, only people from my village bothered to show up. For other residents who came from a different village, they didn't think this event was for them. They organized something else among their kin and friends instead.Footnote 32

In fact, after being abruptly thrust into new surroundings, it is quite common to see people still trying to hang around with their relatives and old friends. The bonding of the old ties seems to be more tenacious than expected. As seen in Table 2, relocated peasants in general have the tendency to socialize primarily with former neighbours only. Allegiance to the original community appears to have a lasting effect.

Table 2: “My major circle of socializing now is still the people from the village where I come from.”

Source:

Authors’ survey, 2014.

Second, the spatial reordering also entails destruction of symbolic space. The elevation process requires more than the demolition of farmhouses; traditional institutions like the temple and ancestral hall are also pulled down in many cases. Temples, according to Lily Tsai, are “encompassing and embedding institutions” that often play a role in the provision of public goods, serve as a hub of networks inside and outside the community, and promote norms of contributing to the good of the community.Footnote 33 During our fieldwork, it was common to find tiny rooms in new buildings reserved for ancestor worship, where tablets commemorating the deceased are kept, and where traditional rituals and religious ceremonies can be held. Yet, in traditional settings these were sacred spaces heavily embedded in memory and symbolic values where differences were contended and arbitrated, and folk knowledge of the common past were shared, where stories were transferred from the elderly to the younger generation, and common understanding of the obligations and rights of individual members of the community were conferred and consolidated through rituals and banquets. Important objects for referencing one's position in the community are thus gone with the demolition of the physical presence of traditional institutions.

Third, the formal delineation of private space also unexpectedly creates barriers for social exchange in the new setting, thus making the formation of common identity in the relocated community even more challenging. Visiting acquaintances (chuanmen 串门) is an important aspect of social life in rural China where most people spend a substantial part of their leisure time chatting and gossiping with their neighbours and relatives. These conversations are mostly casual and relaxed and yet help strengthen the social fabric of the local community in the way that they generate trust and social bonding among the local population. The open style of traditional residential arrangements is relevant here as most of these exchanges occurred in the courtyard in front of one's residence or on the muddy road separating clusters of houses. Many of the peasants we encountered in the fieldwork did, however, complain about the general reluctance to continue the casual dialogue. Doors are now mostly closed and secured in the new living arrangement, and residents’ low trust or concern with security is also reflected in the common arrangement of barred windows or balcony. They therefore feel obliged to pay more respect for one another's privacy and property and hesitate to “intrude.” Visiting has become “formal” and bothersome. As one resident recalled:

It is now too much trouble to visit your friends. In the past you could just do it at the doorstep or courtyard. Now, you have to go upstairs but you don't want to walk into someone's house with your shoes on. Because that will make their home very dirty. It is very inconvenient to take off and then put on your shoes, however.Footnote 34

The relocation process has, moreover, had severer impact on the moral underpinnings of the rural community. The question, “Who are we?” not only concerns community allegiance but is also a puzzle for many locals who are now officially transformed from peasants (cunmin 村民) to residents (jumin 居民). The majority of Chinese peasants have of course already been exposed to urban life as hundreds of millions are working in the cities as migrant workers. The changing status inherent in the relocation process, however, implies a fundamentally different experience. In a temporal sense, the change in economic activities is no longer seasonal or ad hoc but permanent and irreversible in that residents can no longer decide on the timing and duration of non-farm work as the option of agricultural activities is no longer available in most cases. In spatial terms, the relocation also represents a complete cut-off from land and, from this point onwards, most of them are now totally deprived of the defining entitlement of Chinese peasantry – the right to lease land. What makes this transition even more excruciating is that, for many of the relocated peasants, as Zhang and Tong described, it is a process of “passive urbanization.”Footnote 35 That is, they did not initiate the move to become urban population by choice, or may not have been given sufficient time to consider the opportunity bestowed upon them. This change of monumental proportions can be abrupt and unexpected, thus making the transition an agonizing and stressful experience. The attitude to land is testament to the consequent moral disorientation among the residents. As one cadre complained:

It is very frustrating to stop the residents’ farming effort after the relocation. They just love to plant something. They grow peppers, vegetables or fruit in front of the garage, outside our office or wherever they want. They think there must be some “green” in the habitat and most importantly, they just don't feel it is right to leave land idle. They believe they are in some way still entitled to the right to use land, even though they know they no longer own land.Footnote 36

The new spatial order has thus unleashed unintended effects of obstructing various social and moral practices that are crucial for nurturing and preserving community cohesion and solidarity. Adjusting to new residential and social settings also appears to be disorientating and confusing for many. All these concerns disrupt rather than facilitate the emergence of bonding and common identity in the new community. With the old community having been shaken up in the relocation process and the formation of bonding disrupted and hindered by the “hostile” spatial arrangement in the new apartment setting, it is a colossal task for the new local administration to claim connection with members of the newly formed community. And this certainly undermines the effectiveness of local cadres’ exercise of authority on the basis of resonance with local morality.

Danger of Fragmentation of Authority

A common strategy deployed by the relocated peasants to adjust to the moral confusion depicted above is to rely on the original support network; this is acutely expressed in the general expectations placed on the village cadres who had served in the original community. In many cases, they are still seen as the first line of defence against adversity in life. Even after moving into the new neighbourhood and being put under the purview of a new local authority, relocated peasants remain overwhelmingly dependent on the former village cadres when they need help. This is consistently the case among all age groups, as shown in Table 3. One former cadre who is no longer on the payroll of the local administration after relocation, complains about the nostalgia of the fellow residents in the new setting:

These people just refuse to adjust to the new life here. Although every household is now provided with a mailbox in front of their building, they still ask the postman to give all their mail to me. Because this was how it worked; in the past, village cadres just went door to door to deliver the letters. They don't care even that I am not a cadre anymore.Footnote 37

The attachment to village cadres is not just a matter of affection. Village cadres could in fact exert major influence on the interest of peasants during the relocation process. Central to their authority is their discretion first of all over the sequence of relocation and, even more importantly, the designation of village membership. The former decision has major implications for the relocated peasants’ welfare entitlement. Take Nantong, for example. As the speedy reclamation of a huge plot of connected farmlands was imperative for implementing the “10,000-hectare farmland project,” generous welfare entitlements were bestowed upon those who agreed to move out. However, the speed of evacuation was dependent on how quickly the new buildings could be constructed, and thus households were, in most cases, relocated in batches. The order of departure matters because of the variation in entitlements for different age groups. Table 4 summarizes the entitlement for relocation in Nantong. The commencement of benefits is linked to the date of the surrender of the land. For example, the entitlement terms for a household with two children aged 14 and 15 would be much improved if they were allowed to move out two years later. Similarly, a household would be better off if the relocation could be postponed until after the 61st birthday of the grandmother. The order of moving is by and large controlled by the village cadres. Their discretion in deciding the timing of relocation does have considerable impact on the income of households.

Table 3: “I still seek the help of the cadres in the village where I came from when I need help.”

Source:

Authors’ survey, 2014.

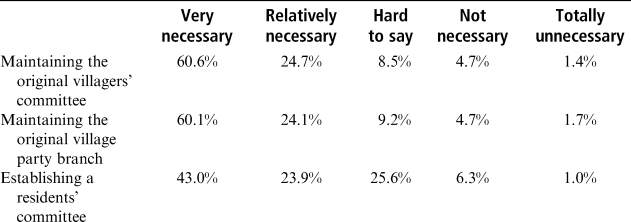

Consequently, as reflected in Table 5, there is general demand for maintaining the original villagers’ committee in the new community.

Table 5: Views on Local Authority Needs after Relocation

Source:

Authors’ survey, 2014.

There is, however, one pressing concern that makes some form of continuity of the original village authority in the new residential setting imperative: the management of collective assets. To start with, the original village authority is entitled to keep 30 per cent of any compensation for the surrender of farmland, which is, legally speaking, collectively owned. In addition, some villages may have other assets, such as factories, cash or other unused land. Although the original collective is now disbanded once the residents of the village have departed and become members of a new community, they are still entitled to any income generated by these assets.

Thus, it is common to see the coexistence of two institutions of local authority in the new community after relocation. On the one hand, there is the residents’ committee (jumin weiyuanhui 居民委员会) which is fully funded by the township administration and in charge of all aspects of administrative management of the new neighbourhood. It is supposed to be an autonomous body (zizhi zuzhi 自治组织) elected by all residents in the community. On the other hand, and running parallel to the residents’ committee, is the villagers’ committee whose only role is to handle the task of collective asset management. In a community that is formed by the merger of several villages, there may be more than one villagers’ committee, or there are clearly delineated subgroups within the villagers’ committee. The villagers’ committee is also an elected body, but the voters are residents in the new community who were members of the same village before relocation. In some locations, an alternative form of shareholding-company can be found. Under this arrangement, all former members of the old village are automatically transformed into shareholders of this newly created economic entity that holds all these inherited collective assets on their behalf. It is common to see either the villagers’ committee or shareholding-company mostly staffed by the former cadres of the original village. They decide on how these assets should be deployed as well as the amount of returns to be distributed to the shareholders each year. Thus, unlike the original villagers’ committee before relocation that enjoyed control over collective assets, the redistributive power of the new residents’ committee is significantly reduced as its role in economic management in the new setting is minimal.

There are attempts to co-opt these former cadres into the newly created residents’ committee.Footnote 38 There are cases of the same group of cadres wearing two hats (yige banzi liangge paizi 一个班子两个牌子). That is, former village cadres are fully co-opted into the newly created residents’ committee. This scenario of full overlapping of personnel between the two institutions is probably the ideal arrangement. Yet with increased personal mobility as a result of a change in hukou status and growing affluence, many former cadres may have already moved out of the community. In addition, the requirement for long working hours, as a result of living in close proximity to the residents, and for new skills and knowledge about estate management, have deterred many former cadres to serve. A former cadre commented:

It is very difficult to serve in local administration these days. You are literally living right next to your fellow residents and they can find you out very easily when they need help. It is now a 24-hour job. And in the past, throwing rubbish outside your home was nobody's business. Now, it will cause conflict and argument and you have to get involved all the time.Footnote 39

These former village cadres may simply choose not to work for the residents’ committee at all. After all, engaging in tedious and routine jobs in community management with limited access to economic resources does not sound very attractive. For many of them, confining themselves to the task of managing the inherited collective assets will almost certainly look more rewarding. The success of the residents’ committee in securing the support and cooperation of these former village cadres who now manage the collective assets and enjoy strong links with local residents is key to effective local governance in China in the long run.

The impact of the elevation process on the local authority is thus tremendous. The danger of fragmentation of the local authority is genuine. Although the newly created residents’ committee is designated as the administrative unit and backed up by the coercive power of the national state to govern, it does not enjoy significant redistributive power. Compared with the villagers’ committee that served as the custodian of collective assets before relocation, its influence over the economic well-being of members of the community is rather limited in the new setting. In most cases, the economic authority is still in the hands of the same group of former village cadres, who may or may not be part of the residents’ committee that is supposed to be the centre of state authority in the new local setting. In addition, the coexistence of dual authorities has to be contextualized in the setting of divided identity. For the reasons mentioned above, the formation of community identity turns out to be a protracted matter. Worse still, the income stream related to the residual collective assets simply reinforces the residents’ allegiance to the original community, thus further obstructing the formation of the new community identity. Local administration, as we argue, only functions well if there is rapport with local morality and it is hard for it to consolidate its authority when members of the new community remain confused and torn between old and new allegiances reinforced by lingering affection and loyalty as well as tangible economic entitlements.

Conclusion

Andrew Kipnis’ work reminds us that the rural changes in post-Mao China are more of a process of “recombinant transformations” rather than historical ruptures as seen in “the simultaneous recycling of the old and the absorption of the new in the process.”Footnote 40 The socio-economic and moral changes unleashed by the elevation process described above are, however, distinct from previous trends in two important ways: the rapacious intensity and damage to local authority.

First, unlike the many cases of land-grabbing that are mostly driven by local financial concerns and a hunger for land by capitalists, the trajectory of the relocation process is also propelled by the strategic concerns of the regime. It is, in fact, a national economic priority to enhance domestic demand (kuoda neixu 扩大内需). This is China's response to the crisis of global capitalism and its related decline in the demand for China's products. The export-led industrialization strategy that was once regarded as the key to China's meteoric rise in the global economy is now seen as untenable.Footnote 41 The regime is understandably desperate for alternative outlets for the products of Chinese enterprise, and, thus, moving peasants to the cities is considered imperative to the enhancement of the general consumptive power of the Chinese population. The relocation projects are therefore deemed necessary for implementing the grand scheme of national economic development. The recent escalation of tension over trade disputes with the Trump administration has certainly reinforced this line of policy-thinking.

The high-level support for the trend is also reinforced by the moral connotation the elevation process implies. Accommodating peasants in modern apartments is integral to the Party's vision of achieving a harmonious society (hexie shehui 和谐社会) in China. “Socialist New Countryside Construction” (shehui zhuyi xin nongcun jianshe 社会主义新农村建设) is deemed a new formula for achieving social justice, as designated by the regime. It is essential for addressing the inequality between urban residents and the rural population, and mandatory for repaying the Chinese peasants for their sacrifices and contributions to the Maoist industrialization project in the pre-reform era.Footnote 42 Liberal scholars in China even argue that the further incorporation of rural society into the market system is a benevolent movement pushing Chinese peasants into a trajectory towards modernity.Footnote 43

This kind of seismic change in rural institutions is not unprecedented in China, however. The Chinese Communist Party has done that before in its grand Land Reform campaign (tudi gaige 土地改革) between the 1930s and 1950s. The moral universe and political landscape of traditional rural China were completely reconfigured by the audacious campaign of land redistribution. The old power structure mediated by lineage and economic inequality was destroyed by the policy of giving land to the peasants based on individual class designations and their political disposition. There is, however, one crucial difference distinguishing the Land Reform programme from the relocation project in the 21st century. Whereas the traditional system of authority demolished by the Land Reform programme was replaced by an even more elaborate party-state machinery, which supported its domination over the living prospects and mobility of the Chinese peasantry, this time the relocation process has accidentally unleashed challenges to the state authority at rural grass roots. As seen in the previous analysis, whereas local administration in the newly settled community still enjoys the backing of state coercive power, its moral and redistributive authority has been undermined. The lingering of village administration in the new community has enhanced the probability of fragmentation of authority. Grassroots authority, both old and new, also suffers from the moral disorientation inherent of the relocation process. The waning of moral bonding in association with the further integration of the household economy into the market system, the shock of passive urbanization and the slow progress of the development of allegiance to, and bonding with, the new community all obstruct the emergence of a new community identity. Rapport with indigenous morality, a cornerstone of local authority in rural China, is now under threat. The relocation strategy that has apparently offered a happy scenario for all concerned parties – national government, local administrations, capitalists and peasants – in the short run, may have triggered a wave of social and political tensions that may eventually turn out to be a major political challenge to the regime for years to come.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank City University of Hong Kong and Research Grant Council of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government for their generous research support. The paper is based on the findings of the project “Elevating the Peasants: Spatial Realignment, Property Right and Local Accountability in Rural China” (GRF Project 153412/9041843). The authors are also grateful for the comments of Feizhou Zhou, Julia Chuang, Jesper Zeuthen, Jessica Wilczak and Rene Trappel, and the assistance of Matt Lui.

Biographical notes

Ray YEP is a professor of politics and associate head of the Department of Public Policy, City University of Hong Kong.

Ying WU is an associate research fellow of the National Institute of Social Development, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.