Introduction

Wage theft – or employer non-compliance with minimum wage laws – has emerged as a major problem for Australian labour market regulation. Recent media reports, government inquiries and academic studies have illuminated this problem, exposing the vulnerabilities of groups of workers to underpayment, particularly temporary migrants on working holidaymaker and international student visas. While underpayment of temporary migrant workers has been a feature of other advanced economies, it is relatively new in Australia, where long-standing preference for permanent immigration and an effective system of labour standards enforcement minimised employers’ capacity to exploit migrants during much of the 20th century (Reference Lever-Tracy and QuinlanLever-Tracy and Quinlan, 1988).

There is growing evidence that underpayment of temporary migrant workers is systematic and widespread and becoming an embedded characteristic of the Australian labour market. While the government’s labour inspectorate, the Fair Work Ombudsman (FWO), has acknowledged the extent of this problem, the response from the Australian government itself has been limited. In this respect, the situation in Australia is not exceptional. Recent inquiries and reports in the United States and the United Kingdom have also drawn attention to widespread non-compliance with wage standards (e.g. Reference Ram, Edwards and MeardiRam et al., 2017; Reference WeilWeil, 2018).

In this article, we focus on two questions: Why has there been recent growth in reported cases of underpayment particularly of temporary migrant workers in Australia? Why has the state failed to implement an adequate strategy to address this problem? We answer these questions with reference to employment relations, migration studies and political science scholarship to draw attention to the fragmented nature of labour market regulation and visa categories constraining worker agency which, combined with widening avenues for temporary migration, have contributed to the problem of underpayment. The conflicting imperatives of the state, the influence of employer organisations in the policy process and weak political incentives to address underpayment are also examined.

Our main conclusion is that addressing underpayment would require major structural reform of Australia’s labour regulation and immigration systems and, by implication, of its wider political economy. The significance of these changes is so great, and likely to provoke such reaction among employers, that they are unlikely to occur in the absence of major political-economic crisis.

Underpayment of temporary migrant workers and state tolerance

Existing scholarship provides various explanations for why wage theft may occur, particularly among susceptible groups such as temporary migrants, and why states may tolerate this situation. Such outcomes potentially flow from policies that favour employers’ interests, disproportionately resulting in workers assuming greater risk. Employment relations scholars emphasise the need for labour market policies to balance efficiency and equity considerations if they are to prove sustainable and fulfil the mutual interests of business and labour (Reference Befort and BuddBefort and Budd, 2009; Reference Buchanan and CallusBuchanan and Callus, 1993). One way that policymakers have traditionally ensured that employment systems are equitable is through ‘inclusive’ regulation to ensure that all workers have access to collective protections, regardless of whether they are union members (Reference GallieGallie, 2007). A key element of ensuring these protections are enforced is through the state mandating a prominent role for unions in their regulation, for instance, through collective rights to enter workplaces, inspect employer records and take industrial action to enforce compliance (Reference EwingEwing, 2005; Reference Quinlan and SheldonQuinlan and Sheldon, 2011). However, with governments in many countries placing greater emphasis on labour market efficiency, marginalisation of unions in recent decades – including their role enforcing labour standards – has accompanied a push towards more ‘exclusive’ regulation, where only union members and/or workers covered by collective bargaining have access to effective employment protection. This has contributed to underpayment, particularly among workers not covered by collective protections (Reference Gunderson, Stone and ArthursGunderson, 2013). With unions marginalised from labour standards regulation in many countries, especially liberal market economies including Australia where neoliberal assumptions have driven policy change (Reference Cooper and EllemCooper and Ellem, 2008), governments have assumed more prominent roles by creating statutory minimum wages and individual employment rights (Reference Colvin and DarbishireColvin and Darbishire, 2013). However, government labour inspectorates often lack the resources to enforce these statutory protections (Reference WeilWeil, 2014).

In the context of more exclusive wage regulation systems, ‘regulatory layering’ (Reference Bray and WaringBray and Waring, 2005) – namely, different regulatory mechanisms of varying strength and effectiveness – tends to produce uneven protections for workers across different organisations and industries (Reference Bray and UnderhillBray and Underhill, 2009). For instance, wage theft appears less likely in larger organisations and industries with greater union representation and bargaining coverage (Reference Brown, Deakin and NashBrown et al., 2000; Reference Gautié and SchmittGautié and Schmitt, 2010). Intermediaries such as labour hire companies, subcontractors and franchised businesses, which are more common in industries excluded from collective protections, can also affect labour standards compliance by obscuring responsibility for workers’ conditions (Reference Johnstone, McCrystal and NossarJohnstone et al., 2012). ‘Strategic enforcement’ initiatives, involving targeting large commercially sensitive firms whose aversion to reputational damage provides incentive to improve labour standards among intermediaries and small firms in their supply chains, have been advanced to deal with underpayment in the context of poorly resourced state regulation (Reference WeilWeil, 2014), including in Australia (Reference Hardy and HoweHardy and Howe, 2015).

Scholarship identifies various reasons why migrant workers might be particularly vulnerable to underpayment. Migrant labour is often – though not always (Reference BauderBauder, 2006) – associated with low-paid and lower-skilled work (Reference PiorePiore, 1979; Reference Waldinger and LichterWaldinger and Lichter, 2003), particularly in labour markets with structural barriers to collective representation which can hinder workers’ assertion of rights (Reference HolgateHolgate, 2005). Temporary migrants are more vulnerable due to limited rights and employment opportunities (Reference FudgeFudge, 2014; Reference RuhsRuhs, 2013) and visa rules that ‘institutionalise’ dependence on employers (Reference AndersonAnderson, 2010; Reference Campbell, Boese and ThamCampbell et al., 2016). For instance, visa rules can constrain the mobility of migrants to switch employers (Reference Wright, Groutsis and van den BroekWright et al., 2017; Reference ZouZou, 2015) or require migrants to gain employer verification to extend their residency rights (Reference ReillyReilly, 2015; Reference RobertsonRobertson, 2014). Moreover, overzealous border security initiatives by governments to enforce migrant workers’ (if not employers’) adherence to these rules and apply punitive penalties, even for minor breaches, can heighten temporary migrants’ vulnerability to unscrupulous employers (Reference ClibbornClibborn, 2015). These structural factors can potentially explain the difficulties of migrants recovering unpaid wages and reporting employers to authorities (Reference Howe and OwensHowe and Owens, 2016).

Previous studies thus indicate wage theft is more likely within organisations and labour markets not covered by collective regulation and among workers, such as temporary migrants, facing structural barriers to collective representation and state enforcement. This suggests the task of addressing non-compliance should, in theory, be relatively straightforward by targeting organisations and industries most likely to evade obligations and workforce groups most likely to be underpaid. However, governments have various, often competing, imperatives that may serve to prevent this. Core government imperatives such as maintaining economic prosperity, national security and protecting fairness can come into conflict in certain policy areas, including labour immigration (Reference BoswellBoswell, 2007). For instance, increasing migrant labour supply can deliver net economic benefits, but if temporary migrants’ rights are restricted, this can make them a more attractive source of recruitment thereby degrading employment opportunities and working conditions for citizens and permanent residents (Reference RuhsRuhs, 2013). To resolve such conflicts, governments often send ‘control signals’ – for instance, by implementing policies that restrict entry for highly visible groups of migrant workers to placate populist sentiments – while continuing to maintain liberal entry controls for other groups, particularly those perceived as beneficial to economic performance or to the interests of governing parties’ political supporters (Reference WrightWright, 2014).

Employers in labour markets characterised by weak regulation may benefit disproportionately from policies expanding temporary migrant labour supply. This gives these employers incentive to lobby for creation of such policies or to resist attempts to address mistreatment of migrant workers (Reference FreemanFreeman, 1995). While such policies may not benefit the broader workforce, therefore potentially generating resistance, close party–political relationships and ideological affinities between business and the governing parties can also explain why governments, including Australian governments, have adopted or maintained employer-friendly labour immigration policies (Reference WrightWright, 2017). However, in some circumstances, employer organisations may support measures strengthening labour standards regulation including among temporary migrant workers. These include creating a level playing field to minimise unfair competition (Reference HowellHowell, 2005), compensatory trade-offs through business-friendly policies in other areas (Reference CastlesCastles, 1988), or to complement broader policy objectives such as innovation and skills development (Reference CulpepperCulpepper, 2011). Business and government support for stronger regulation to minimise wage theft is more likely if political salience is heightened. That is, if public opinion is exercised sufficiently by the issue to influence electoral outcomes, policy change is more likely than if voters perceive the issue to be marginally important and therefore unlikely to affect their voting decisions (Reference CulpepperCulpepper, 2011; Reference Givens and LuedtkeGivens and Luedtke, 2005).

The following sections examine reasons for the recent rise in reports of employer underpayment of temporary migrant workers, including fragmentation of labour market regulation and employer-driven expansion of temporary migration. The Australian government’s recent measures to address the problem, why those measures are inadequate and why the government is unlikely to rectify this are then explained.

Patterns of underpayment in the Australian labour market

Cases involving prominent brands have dominated recent mainstream media coverage of wage theft in Australia. However, non-compliance with minimum wage laws appears to be widespread, particularly in industries such as hospitality, retail and horticulture and mainly impacting temporary migrant workers. While there have been past instances of employer non-compliance with minimum wage laws in Australia, such practices appear to have increased markedly in recent years.

In August 2015, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s (ABC’s) Four Corners, current affairs television programme, broadcasted a story exposing non-compliance in 7-Eleven franchises (ABC, 2015a). The programme presented evidence that the stores’ workers, comprising mainly international student visa holders, were underpaid in breach of national minimum wage laws. Many of these workers received threats to report them to the Department of Immigration and Border Protection (now called Department of Home Affairs) for working in excess of hours allowed under their visas. This expose, together with another Four Corners report examining similar issues in horticulture (ABC, 2015b), brought to the public’s attention the problem of underpayment of migrant workers and increased the salience of this issue.

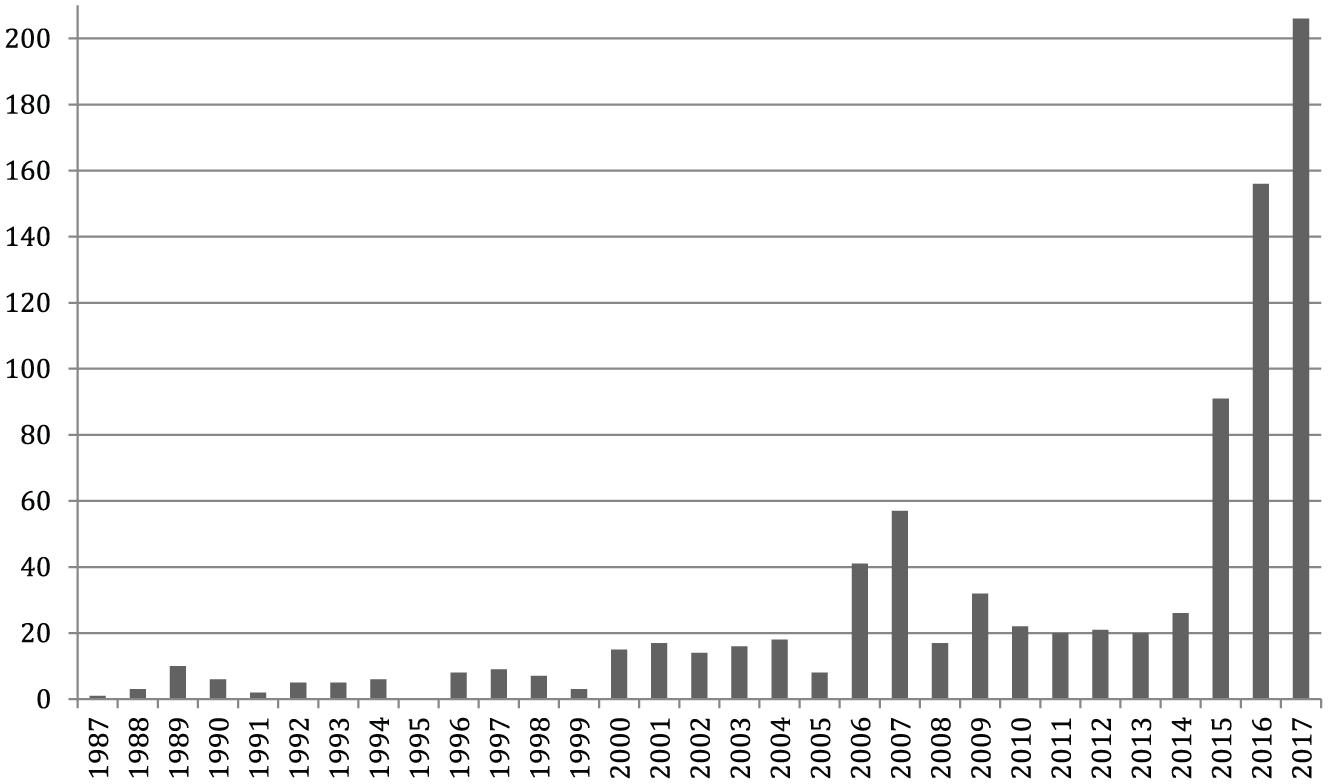

Many subsequent reports in diverse mainstream media outlets further highlighted the extent of wage theft in Australia, yet there remained strong focus in media coverage on prominent franchise brands. To illustrate this, we conducted a search, using the Factiva database, of occurrence of the word ‘underpayment’ in articles published between 1987 and 2017 in major Australian newspapers: The Australian, The Australian Financial Review, The Sydney Morning Herald and The Daily Telegraph (see Figure 1). While some articles reported widespread underpayment of wages in retail, hospitality and horticulture (e.g. Reference BagshawBagshaw, 2016; Reference PattyPatty, 2016), prominent franchise businesses such 7-Eleven and Domino’s Pizza dominated news coverage.

Figure 1. Number of reports containing the term ‘underpayment’ in the coverage of major daily Australian newspapers, January 1987 to December 2017.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data generated from Factiva.com of reports in The Australian, The Australian Financial Review, The Sydney Morning Herald and The Daily Telegraph (Sydney).

Importantly, Figure 1 indicates that wage theft as reported in the media was virtually a non-issue prior to 2015. The lone exception was a spate of reports in 2006–2007 over mistreatment of workers on temporary skilled visas, particularly by employers in regional areas who at the time were exempt from various wage and salary regulations. These cases involved non-payment of overtime and allowances and employers charging workers unfairly for their immigration processing, housing and transportation costs (e.g. Reference LaurieLaurie, 2006). The incidence of media reports of underpayment increased ten-fold from 2013 to 2017.

It is important to emphasise the legacy of employer wage theft in Australia. Reference Goodwin and MaconachieGoodwin and Maconachie (2007) argued that unpaid wages recovered by Australia’s federal labour inspectorate of AUD0.4–AUD6.9 million per year from 1972 to 1996 evidenced ‘significant, and sustained’ employer non-compliance (p. 542). They raised concern that such non-compliance in Australia’s then-centralised industrial relations system might foreshadow greater difficulties to resist underpayment in the context of a more decentralised system. Despite these precedents, a series of government inquiries over the past decade provide considerable evidence that wage theft has become much more widespread. This is particularly the case in low-wage, low-skill jobs in industries such as retail, hospitality and horticulture with certain structural characteristics, such as weak or absent unions, extensive casual employment and subcontracting, intense commercial competition, labour cost minimisation as a dominant business strategy, and other features associated with poor job quality (Reference Maconachie and GoodwinMaconachie and Goodwin, 2010; Reference Tham, Campbell, Boese, Howe and OwensTham et al., 2016). Although the precise structural characteristics of these industries vary, they nevertheless share the common feature of failing to deter employers from breaching their employment law obligations.

A 2008 inquiry into temporary skilled visas noted prevalent termination of employment and visa sponsorship if visa holders raised concerns about underpayment (Reference DeeganDeegan, 2008). In 2015, the Productivity Commission (2015) observed that, compared to Australian citizens, migrant workers were more susceptible to underpayment due to their ‘English language skills, limited knowledge about their workplace rights and entitlements, and dependence on their employer for their visa’ (p. 915). The Senate’s inquiry into the impact of Australia’s temporary work visa programmes found evidence of widespread underpayment (Senate, 2016). A subsequent inquiry by the same Senate committee into corporate avoidance of the Fair Work Act (Australia’s primary national employment legislation) stated that in some sectors, ‘the exploitation and abuse of workers on temporary visas appears to be so widespread it is becoming the norm’ (Senate, 2017). These reports were consistent with the FWO recovering AUD22.3–AUD30.6 million annually in unpaid wages on behalf of between 11,613 and 17,000 workers from 2013 to 2017. Temporary migrant workers were overrepresented in these figures, making up 6% of the Australian workforce but 18% of the disputes that the FWO (FWO and ROC, 2017a) assisted with and 49% of court cases commenced.

Even in light of temporary migrant workers accounting disproportionately for the FWO’s work, the Senate observed ‘chronic underreporting of exploitation’ to the FWO. It noted that international students were reluctant to approach the FWO for fear of deportation due to breaching their visas by working more hours than allowed (Senate, 2017: 67). The FWO commissioned a study to examine this problem of underreporting which found that international students underreported for various reasons, including incomplete knowledge about workplace rights and fear of consequences (Reference Reilly, Howe and BergReilly et al., 2017). In addition, in just over 2 years since the Four Corners story, 7-Eleven (2017) determined claims totalling over AUD150 million for over 3600 of its workers at an average of AUD41,196.66 per worker. If one franchise organisation underpaid its workers by this much, it would appear that the FWO is merely scratching the surface of wage theft.

Recent scholarly research has also quantified extensive non-compliance with Australia’s minimum wage laws. Reference Underhill and RimmerUnderhill and Rimmer’s (2016) survey of 278 horticulture workers, the majority of whom held working holidaymaker visas, found mean hourly wages well below applicable minima. In Reference Howe, Reilly and van den BroekHowe et al.’s (2017: 35) survey of 332 employers of horticulture workers, the majority of whom were temporary migrants, 17% of employers admitted to paying under minimum weekday wage rates and 74% to paying under minimum weekend wage rates. Nyland et al. interviewed 200 international students, 62 of whom reported their hourly pay. About 58% earned AUD7–AUD15 per hour, which the authors assessed as below the applicable minimum wages (Reference Nyland, Forbes-Mewett and MarginsonNyland et al., 2009). In Clibborn’s 2016 survey of 1433 international students, of those working at the time of the survey, 35% were paid AUD12 per hour or less (well under the minimum legal wage) and 100% of those working as waiters and shop assistants were paid under the prevailing minimum legal weekend wage rates (Reference ClibbornClibborn, 2016, 2018). Most recently, this level of underpayment was confirmed in a survey of 4065 temporary migrant workers asked to nominate their hourly pay in their worst paying job, finding that 30% had been paid AUD12 per hour or less (Reference Berg and FarbenblumBerg and Farbenblum, 2017). It is clear that underpayment of temporary migrant workers is a widespread problem in Australia to a greater extent than identified by Goodwin and Maconachie’s historical study (2007). We now turn to the reasons for its recent rise, before considering what the government has done to address it.

Fragmenting of labour market regulation

Fundamental changes to labour standards regulation in recent decades can help partly to explain growing incidence of underpayment. The once-prominent role of unions in enforcing a largely ‘inclusive’ regulatory system has diminished and been partially supplemented by an under-resourced government inspectorate policing an ‘exclusive’ system (Reference HardyHardy, 2011; Reference Hardy and HoweHardy and Howe, 2009; Reference Maconachie and GoodwinMaconachie and Goodwin, 2011). For most of the 20th Century, Australian unions held a central role in setting and enforcing minimum standards through the conciliation and arbitration system. Under that system, unions enjoyed legal status as parties to awards, while high union density and relatively free right to enter workplaces provided them with knowledge of employer non-compliance and opportunity to address it. This also deterred employers from breaching employment standards given the risk of detection.

Unions now have little role as enforcers of Australia’s employment standards, no longer having any formal function as joint regulators with the state. This has resulted partly from union membership decline but is also due to their active marginalisation in the context of ‘neoliberalisation’ of labour market regulation (Reference Cooper and EllemCooper and Ellem, 2008). While unions never attained universal coverage and have always been weak in industries with structural barriers to effective regulation (Reference Maconachie and GoodwinMaconachie and Goodwin, 2010; Reference Tham, Campbell, Boese, Howe and OwensTham et al., 2016), union density has dropped from its height of 65% in 1948 (Reference BowdenBowden, 2011) to 16% of full-time workers overall and only 9% in the private sector in 2016 (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016a). Having fewer members in workplaces reduces unions’ awareness of employment law violations as well as their capacity to represent individual members seeking to recover unpaid wages. In addition, the legislative changes of the Howard Liberal-National ‘Coalition’ government – most notably the Workplace Relations Act 1996 (Cth) and the 2005 ‘WorkChoices’ amendments to that Act – directly reduced the rights and roles of unions.

These developments have resulted in an increasingly ‘exclusive’ system of labour standards characterised by ‘regulatory layering’. While 78% of workers had their wages set by awards (industrial instruments setting minimum standards across industries) in 1990 (Reference Bray, Waring and CooperBray et al., 2014: 256), only 59% of workers had their wages set by either awards (23%) or collective agreements (36%) in 2016 (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016b). Although workers in large organisations and certain mainly public sector–related industries have greater access to collective protections, those working in smaller businesses and industries with low union density, such as agriculture and hospitality, are much more susceptible to employer non-compliance. This is particularly so in industries characterised by complex supply chains, the presence of intermediaries and fragmented business models, such as franchise operations, in which commercial pressures can produce conditions of non-compliance and obscure responsibility over labour standards (Reference Johnstone, McCrystal and NossarJohnstone et al., 2012).

This same programme of legislative reform nationalised Australia’s previously largely federalised industrial relations system and placed the responsibility of enforcing minimum standards on one under-resourced state inspectorate. From 2005, the minimum wage standards of almost all employees of private enterprises were set and monitored in the national system. The previously ‘responsive’ system of conciliation, arbitration and joint-enforcement was replaced with a ‘command and control’ system of minimum standards (Reference Cooney, Howe and MurrayCooney et al., 2006) backed up by a state enforcement agency, currently known as the FWO. The FWO has never been sufficiently resourced to replace the roles played by the enforcers of employment standards under the previous system. The FWO has maximised its limited resources through strategic enforcement (Reference Hardy and HoweHardy and Howe, 2015). However, with only about 250 inspectors for over 2 million workplaces (Reference ClibbornClibborn, 2015) and legal staffing sufficient to litigate only 50-55 cases annually (FWO and ROC, 2017a), the FWO has limited prospects of achieving its stated goal of ‘[ensuring] compliance with Australian workplace laws’ (FWO, n.d.).

Employees in all industries still have de jure access to minimum standards set by relevant awards, although these remain incomplete in their coverage of industries and occupations. However, weakness of unions and negligible collective bargaining coverage in industries such as agriculture and hospitality, combined with the FWO’s lack of resources, grants significant discretion to employers over whether to comply with these standards, particularly for workers vulnerable to underpayment.

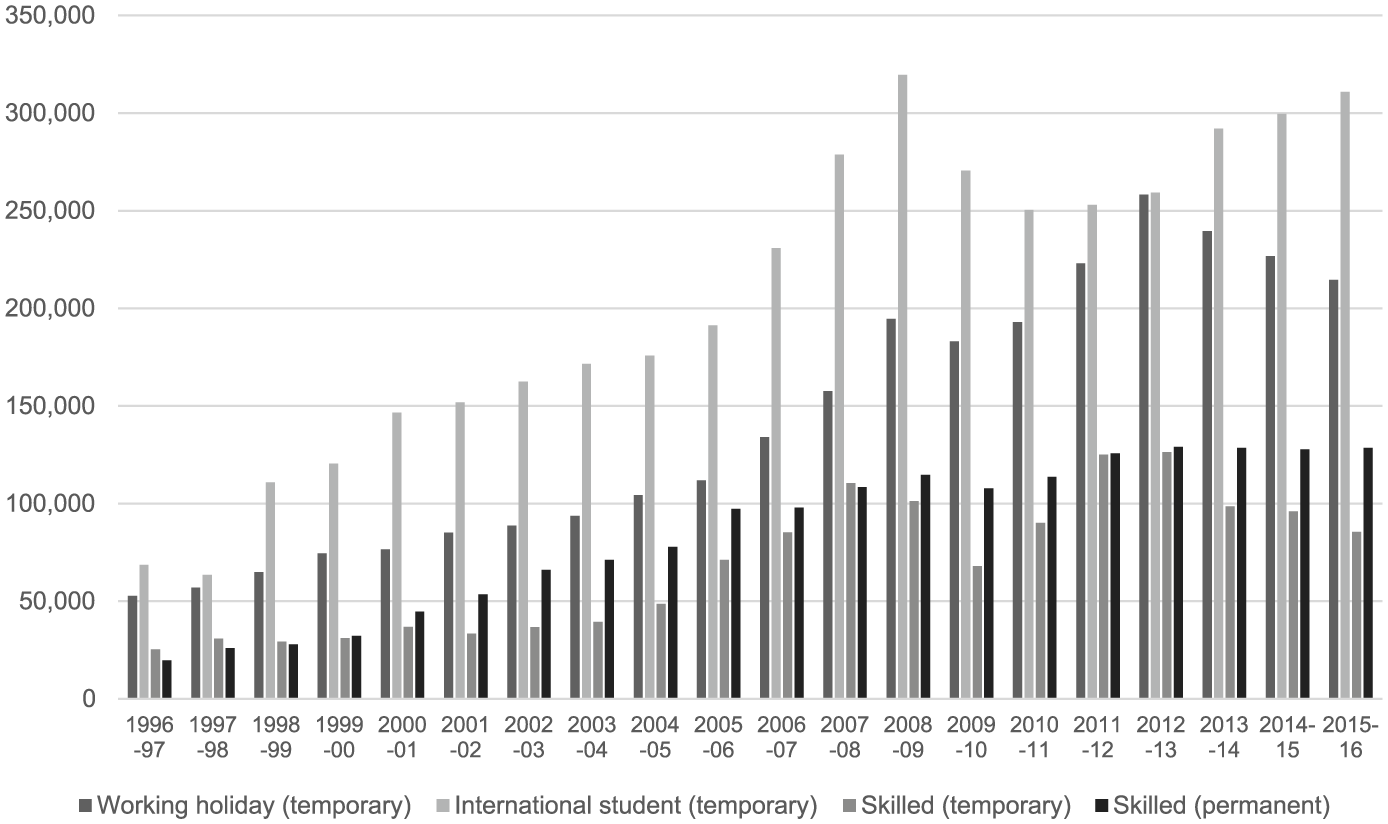

Growth of temporary migration

Coinciding with – and partly contributing to – the fragmentation of Australia’s employment regulation framework and weakened enforcement capability has been a large increase in low-skilled labour supply. Immigration policy changed dramatically from the late 1990s, with a general shift towards higher intakes of temporary forms of ‘economic’ immigration, which have vastly outnumbered permanent visas that Australian immigration policy had exclusively prioritised since the early 20th century (Reference Markus, Jupp and McDonaldMarkus et al., 2009; Reference WrightWright, 2015; Reference Wright, Clibborn and PiperWright et al., 2016). While the stated objective of this shift was to fill skills needs and assist the growth of export industries such as education and resources, the emergence of ‘side doors’ and ‘back doors’ – namely, the expansion of schemes designed for purposes other than labour immigration – has increased the supply of temporary migrants in low-skilled work (Reference Wright and ClibbornWright and Clibborn, 2017). As Figure 2 indicates, the vast majority of this increase has been in international students and working holidaymakers, both of whom have rights to work in Australia, yet without all of the protections associated with unfettered work and social rights afforded to citizens and permanent residents. While the workforce has always included relatively marginalised groups, such as Indigenous Australians and women, the considerable increase in supply of workers susceptible to mistreatment has contributed to underpayment. As well as being concentrated in low-skilled work where migrant workers’ bargaining power is already limited (Reference BauderBauder, 2006), regulation of these visas imposes barriers to these workers exercising voice or mobility in the event of mistreatment (Reference HoweHowe, 2013). These visa regulations are part of a broader government objective to orient immigration policies towards employers’ labour market demands (Reference WrightWright, 2017). Despite long-standing public attention to the mistreatment of those entering under the Temporary Skill Shortage visa (previously known as the subclass 457 visa), wage theft appears to be more common among the employers of working holidaymakers and international students (Reference Tham, Campbell, Boese, Howe and OwensTham et al., 2016). Underpayment of the latter groups of workers has received less scrutiny by comparison, including by researchers, despite accounting for much larger proportions of Australia’s immigration intake.

Figure 2. Annual immigration intakes for main work-related visa categories, Australia.

Source: Department of Immigration and Border Protection (various sources).

The number of people entering Australia annually on international student visas increased from 68,611 in 1996–1997 to 310,845 in 2015–2016. While driven primarily by a desire to increase tertiary education revenue, the rights of international students to work up to 40 hours in any fortnight during semester and unlimited hours outside of semester has meant that they contribute an important share of the workforce, particularly to industries such as retail and hospitality. The expansion of the working holidaymaker temporary visa programme, comprising the subclass 417 Working Holiday visa and subclass 462 Work and Holiday visa, has also benefitted low-wage industries, particularly horticulture. While the scheme is formally aimed at promoting cultural exchange, growth in working holidaymaker visas issued, from 52,700 in 1996–1997 to 214,583 in 2015–2016, has been driven mainly by industry pressure (Reference Wright and ClibbornWright and Clibborn, 2017). The scheme allows an unlimited number of people aged 18–30 years from select countries to visit Australia for up to 1 year during which they may perform any work, with the only restriction being a maximum of 6 months of work with each employer. In 2005, the Australian government introduced a major change to the programme, allowing subclass 417 visa holders to extend to a second year if they worked for least 88 days in a designated regional area during the first year of their visa. This incentive was introduced to meet apparent labour shortages in regional areas, particularly in horticulture (Commonwealth Parliament, 2005). It successfully encouraged significant increased supply to meet fruit and vegetable farmers’ seasonal demand for low-skilled labour. While the Seasonal Worker Programme has also been created to serve the labour needs of horticulture, this scheme is primarily an international aid programme supporting Pacific Island nations and accounts for a small number of the temporary migrants working in the industry (4772 in 2015–2016).

Thus, two main factors have led to the recent growth in reported cases of underpayment, particularly of temporary migrant workers in Australia: The fragmenting of labour standards enforcement and policy changes that produced an increase of a vulnerable workforce. These factors are interrelated, operating together to pressure already marginalised workers to accept wages below the legal minimum. The lack of an effective enforcement regime allows employers to calculate the minimal chance of being caught breaching employment laws against the considerable savings available through underpayment.

Attempts by the state to address wage theft

The Australian government has recently taken steps to address employer wage theft. However, in light of the findings of recent multiple government inquiries and academic research, those steps are inadequate to properly address the nature and scale of the problem. They are inadequate because the policy measures are targeted at a very narrow group of highly visible organisations without systematically addressing the causes and prevalence of underpayment of temporary migrants. There are several incentives for the government to maintain the status quo as well as barriers to effectively ensuring compliance among employers.

In one such step, working holidaymakers seeking to extend their visas to a second year by working for 88 days of specified work in a regional area were required to show proof that they were paid in compliance with minimum wage laws for any work performed after 1 December 2015 (Australian Government, n.d.). In announcing this new requirement, the then-Assistant Minister for Immigration and Border Protection, Senator Michaelia Cash, noted that existing arrangements created ‘a perverse incentive for visa holders to agree to less than acceptable conditions in order to secure another visa’ and introduced the change to ‘prevent exploitation and ensure public confidence in the system is upheld’ (Reference CashCash, 2015). However, the change places the onus on vulnerable temporary migrant workers to produce proof of payment and imposes a penalty on them if they fail to do so. This creates the perverse outcome where a worker suffering underpayment will additionally fail in an application for a second year visa. This was illustrated in a 2017 Administrative Appeals Tribunal of Australia decisionFootnote 1 in which a temporary migrant failed to extend his working holidaymaker visa to a second year despite working the requisite 88 days, as his wages were lower than legally required for the hours worked.

In May 2016, citing underpayment in 7-Eleven stores, the Turnbull Coalition government released a policy to protect vulnerable workers. Observing that ‘in many cases there is no perceived risk of [non-compliant employers] being caught’, the policy promised an extra AUD20 million in funding for the FWO (Liberal Party and National Party Coalition, 2016). However, the FWO did not receive the additional funding. The promise of an extra AUD20 million came in the same month as the federal budget for 2016–2017 cut AUD17 million from the FWO’s (2016: 125) funding. In the 2017–2018 budget, the FWO’s funding was increased by AUD14 million but, by then, it included resourcing for the new Registered Organisations Commission (ROC)Footnote 2 (FWO and ROC, 2017b: 136). This meant that in 2017–2018, the combined budgets of the state agency responsible for policing minimum wage compliance (the FWO) and the state agency responsible for policing union activities (the ROC) was less than the budget for the FWO alone in 2015–2016. Forward projections for the 2017–2018 federal budget anticipated additional cuts to the FWO (Australian Government, 2017: 6–41).

The Coalition government also introduced legislative measures aimed at protecting temporary migrant workers. The Fair Work Amendment (Protecting Vulnerable Workers) Bill was introduced to federal parliament in May 2017 and became law, in amended form, in August 2017. The Amendment Act sought to bolster protections for vulnerable workers in several ways. Maximum penalties for non-compliance with minimum wage laws were increased 10-fold in cases of ‘serious contravention’ (s.557A). Potential liability for underpayment was extended beyond direct employers to franchisors, holding companies and their officers (s.558B). In addition, the FWO was granted enhanced evidence-gathering powers (Division 3, Subdivision DB) and, via an amendment introduced by the Labor opposition, the onus of proof was reversed for claims relating to underpaid wages where the employer fails to produce pay slips (s.557 C).

While the practical impact of these amendments will become apparent over time, some potential limitations are evident. The new maximum fine is only applicable when an employer ‘knowingly’ and ‘systematically’ underpays (s.557A(1)), likely requiring an employer to be caught by the FWO for multiple contraventions over a long period. The increased liability of franchisors applies only to a ‘responsible franchise entity’, defined as a person who ‘has a significant degree of influence or control over the franchisee entity’s affairs’ (s.558A(2)). In addition, it applies only to franchisors and holding companies who ‘knew or could reasonably be expected to have known that the contravention [by the franchisee or subsidiary] would occur’ (s.558B(1)(d) re franchisors and s.558(2)(c) re holding companies). Franchisors and holding companies may also escape liability if they are able to show that they took ‘reasonable steps to prevent a contravention by the franchisee entity or subsidiary’ (s.558(b)(3)). Thus, the amended law applies more narrowly than to franchisors and holding companies at large and, as argued by Maurice Blackburn Lawyers in their submission to the Senate Committee’s inquiry into the Bill, presents opportunities for those parties to avoid liability (Maurice Blackburn, 2017). This would appear to be an example of the government responding to heightened political salience following the 7-Eleven and similar scandals by being seen to address a perceived problem with franchises without overly restricting other businesses.

A significant omission from the Fair Work Act amendments is any attempt to regulate minimum wage compliance in either supply chains or labour hire arrangements, particularly in light of the prevalence of non-compliance in such arrangements (Reference ForsythForsyth, 2016; Senate, 2016). Twelve years after Australia’s previously state-based private sector employment law systems were nationalised, and in lieu of federal government action, three states sought to address underpayment of workers engaged by labour hire operators. In 2017, the Victorian, Queensland and South Australian state parliaments introduced legislation requiring labour hire contractors to hold a licence and, in order to gain a licence, to demonstrate compliance with workplace laws among other requirements. At the time of writing, the Queensland and South Australian legislation had passed and were due to commence in early 2018.

Barriers to eradicating employer wage theft

Implementing these legislative changes may help to give individual workers stronger recourse to employment protections and create greater deterrent effects for certain non-compliant employers, particularly those in franchise arrangements. However, their impact is likely to be limited in the absence of widespread changes in Australia’s employment and immigration policies. In the context of increasingly ‘fissured’ workplaces (Reference Hardy and HoweHardy and Howe, 2015; Reference WeilWeil, 2018), it appears necessary to impose greater obligations to improve compliance on lead firms at the top of supply chains, such as supermarkets, whose commercial pressures are often an impetus for non-compliance among suppliers, labour hire companies and small businesses with minimal aversion to reputational damage. Moreover, by keeping unions marginalised and failing to address the structural barriers in immigration regulation that can prevent temporary migrants from seeking redress, existing employment and immigration policies only serve to exacerbate underpayment. By persisting with its ‘command and control’ system of employment regulation policed by an under-resourced labour inspectorate, the government is failing to heed the benefits of responsive joint regulation that can better address temporary migrant workers’ vulnerabilities to underpayment, such as fear of deportation, general distrust of government, and lack of reliable information about rights and enforcement.

Business influence over public policy in Australia appears to be a significant barrier to introducing these measures to systematically eradicate wage theft. Employers in agriculture and hospitality have shifted their business models in response to the expansion of temporary migrant labour. Both of these industries are characterised by absence of unions, low wages and poor job quality (Reference Knox, Warhurst and NicksonKnox et al., 2015; Reference Underhill and RimmerUnderhill and Rimmer, 2016). Weakness of organised labour in particular has diminished any pressure for employers to address their labour supply challenges through ‘high road’ solutions such as investing in workforce training and technology. Attempts by unions to improve wages and conditions – for instance, by establishing collective agreements among larger firms – have been fiercely resisted in these industries (e.g. Reference SchneidersSchneiders, 2017). Pressure from industry associations has been the catalyst for policy changes encouraging temporary migrant workers into these industries, notably the 2005 decision to allow working holidaymaker visa holders to gain a second year if they worked for least 88 days in a regional industry (Reference Wright and ClibbornWright and Clibborn, 2017). Reliance on these mechanisms of labour supply is a central component of the low wage business models dominant within these industries, which employers and industry associations are very reluctant to give up.

Peak employer associations are also likely to resist any attempt to reverse neoliberal employment and immigration policies to address underpayment. The Business Council of Australia and the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry are closely associated with the shift towards a more decentralised and individualised system of employment relations (Reference Cooper and EllemCooper and Ellem, 2008; Reference Sheldon and ThornthwaiteSheldon and Thornthwaite, 1999). Their commitment to this system is evident in their policy agendas which continue to focus on more flexible and employer-friendly regulations (Reference Barry and YouBarry and You, 2017). Similarly, policy advocacy by these peak associations was a central reason for the regulatory changes that precipitated expansion of skilled and temporary visas, the rationale for which was to improve the responsiveness of immigration policy to employer demand (Reference WrightWright, 2017). More recently, employer associations such as the Franchise Council of Australia have lobbied actively to ensure that changes to the Fair Work Act in support of vulnerable workers would not negatively impact their membership (Reference FergusonFerguson, 2017; Reference GartrellGartrell, 2017).

Governments of different political orientations have demonstrated their commitment to existing policies that have underpinned employer non-compliance. Close political connections between the Coalition parties and employer associations served to deliver many of the neoliberal employment and immigration reforms described above, particularly under the Howard government (Reference Cooper and EllemCooper and Ellem, 2008; Reference WrightWright, 2015). Labor governments may be less committed to these policies; however, the reforms of the Rudd and Gillard governments did not fundamentally challenge the decentralised and individualised nature of employment regulation in which the role of union activity remained legally confined (Reference CooperCooper, 2010). Aside from marginally strengthening individual workers’ rights, these Labor governments also failed to reverse the Howard government’s demand-driven immigration policies aimed primarily at meeting employers’ short-term needs (Reference HoweHowe, 2013).

Low political salience of immigration and employment policies is another reason why governments are unlikely to address the systematic problems that have produced widespread underpayment. Put simply, reforming these policy areas is unlikely to win many votes. Public opinion data from the Australian Election Study indicates that while voters are increasingly wary of big business, almost 50% of voters in 2016 still believed that unions had too much power (Reference Cameron and McAllisterCameron and McAllister, 2016). This suggests some possible antipathy towards reforms to restore union rights and powers to enforce labour standards.

Although wage theft is most closely associated with temporary migrant labour, there appears to be minimal public agitation for policies reducing immigration. Existing immigration policies are failing temporary migrant workers who are often underpaid or mistreated and possibly deterring employers from investing in the skills of Australian citizens and permanent residents, particularly the young who are more likely to be unemployed or under-employed (Reference BoucherBoucher, 2016). The Turnbull government’s trumpeted changes to temporary skilled visas in 2016–2017 represented a ‘control signal’ designed to convince sceptical voters that it was addressing employer misuse of immigration policy (Reference PattyPatty, 2017). However, the incremental nature of these reforms mean their impact is likely to be minimal, particularly given they do not extend to the employment of working holidaymakers and international students where exploitative employer practices are more common (Reference Tham, Campbell, Boese, Howe and OwensTham et al., 2016). Nevertheless, data from the Australian Electoral Study suggest that public attitudes in Australia towards immigration, particularly economic immigration, have been consistently neutral and by some measures positive in recent years. Since 1998, a clear majority of survey respondents has consistently agreed that immigrants are generally good for the Australian economy, compared to fewer than one in five disagreeing. Over the same period, more respondents have generally disagreed than agreed that immigrants take jobs away from people born in Australia. Although more respondents have consistently favoured decreasing rather than increasing the size of the immigration intake, attitudes have remained remarkably steady given the large increase in immigration over the past two decades (Reference Cameron and McAllisterCameron and McAllister, 2016).

One potential solution to the problem of underpayment, in light of the inadequate influence of the state over labour law compliance and the positive impact of public attention on compliance in 7-Eleven, lies in mobilising consumer power. There has been growing emphasis within scholarship on the importance of ‘end users’ of products and services, be they individual customers or commercial clients, on industrial relations (Reference HeeryHeery, 1993). The impact of supply chain pressure from commercial clients or ‘lead firms’ on working conditions among their suppliers underscores the imperative for strategies that pressure end users, be they customers or lead firms. While campaigns by unions and labour activists against firms to improve labour standards compliance in their supply chains have become more common, these are likely to be effective only against large prominent brands and therefore have limitations (Reference Donaghey, Reinecke and NiforouDonaghey et al., 2014). Nonetheless, there is also scope for campaigns to influence individual customers to purchase products or services only from businesses that demonstrate labour law compliance. In this way, there is some potential in the United Voice union’s recently launched employer rating website, http://www.ratemyboss.org.au, to aid consumers in making such decisions.

Conclusion

We have argued that the two principal causes of the escalation in reported cases of underpayment are the dismantling of an effective system of employment regulation, and the expansion of temporary forms of migration with embedded barriers to employment rights and protections for visa holders. As with employment regulation more broadly (Reference Buchanan and CallusBuchanan and Callus, 1993), it is necessary for labour immigration regulation to strike a balance between ‘equity’ and ‘efficiency’. Prevailing policy arrangements have been effective in enabling greater labour market efficiency by matching the supply of immigrant workers with employers’ needs relatively quickly. However, there are seemingly significant equity problems in ensuring that temporary migrants are treated fairly and are not employed in ways that disadvantage them or other workers in the labour market. Weak employment and immigration regulations have failed to protect temporary migrants at work, equating the demands of employers too readily with the interests of the labour market as a whole.

The problem of employer underpayment of temporary migrant workers’ wages is one that the Australian government appears to be unwilling or unable to solve. The minor policy responses recently implemented are merely tinkering around the edges. These changes indicate the government’s inclination to treat the problem as it might any public relations challenge: doing just enough to placate the media and the public so as to quell any outrage that might result in lost votes. A case has been made for prioritising permanent forms of immigration, which have delivered clear benefits to Australia’s economy and society, over temporary forms of immigration where problems of wage theft are concentrated (Reference CollinsCollins, 2013). However, such a shift is arguably neither practical nor desirable and has the potential to cause upheaval, particularly for temporary migrants and compliant employers. This move alone would not systematically address the problem of underpayment, which would also require the reversal of 30 years of neoliberal changes to employment regulation. In the absence of a crisis, such reversal is unlikely to occur due to the resistance that would be provoked among employers and within government.

Therefore, we must look beyond the state for solutions to the wage theft problem. Notwithstanding the significant barriers to collectivism under the current regulatory framework, unions must find creative ways to represent workers and particularly temporary migrants. Legally, compliant businesses must recognise the threat to their level playing field and demand changes to their employer association representation. Consumers must demand legal treatment of the workers who serve them. Yet, there still remains an important role for the state. Given the volume of scholarship on the benefits of responsive, joint regulation, and in light of the obvious failings of Australia’s experiment with command and control employment regulation, enforcement partnerships between government and other stakeholders must be the way forward. If the problems of wage theft continue, they might yet build to a crisis significant to force an adequate strategy from the Australian government.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the two anonymous reviewers and to Joanna Howe for useful and constructive comments on earlier versions of this article, to Anne Junor and Michael Quinlan for their guidance, and to participants who provided feedback at the AIRAANZ Conference 2018.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.