Introduction

Individual choice of insurance is used in several health systems as a means to empower citizens. This is based on the assumption that the insurers will act strategically on behalf of their clients to meet their needs and preferences and ensure access to high quality services, or else risk losing them to a competing insurer. Competition among insurance funds is expected to lead to improved health system efficiency, higher satisfaction with insurer services for clients (such as timely provision of information, easy administration, low waiting times, waiting list mediation, etc.). There is also an expectation that insurance competition will lead to improved care quality and could stimulate the development of more person-centred services.

The degree of choice and competition between insurers varies between health systems that have introduced this approach, as do the expectations that policy-makers in individual settings associate with choice and competition. Related policies range from those that only allow choice of insurance fund or company (with the ability to switch between insurers within defined periods) to those that expect (and incentivize) insurers to compete on quality and cost of their purchased care. Insurers may be given additional instruments to do so, including the possibility to offer different insurance premiums (while ensuring the same benefits) to attract more customers; others involve selective contracting, that is, insurers only contract with providers that are expected to deliver better value services in terms of cost and quality.

A number of countries have introduced (various degrees of) insurance choice and competition. In Europe, these are Belgium, the Czech Republic, Germany, the Netherlands, Slovakia and Switzerland. Other examples include Israel and the United States of America (USA). These countries have systems or subsystems in place that allow people to choose among a (varying) number of health insurance funds and they may switch between funds on a periodic basis. Such schemes are typically highly regulated to ensure that they are affordable, minimize risk selection and do not undermine health care coverage.

This chapter discusses insurance choice and competition models in six countries: Germany, Israel, the Netherlands, Slovakia, Switzerland and the USA. We selected these countries because they represent varying degrees of insurance choice and competition. More importantly perhaps, these countries have explicitly pursued choice and competition in health care more broadly (Reference SmatanaSmatana et al., 2016; Reference KronemanKroneman et al., 2016; Reference Rosen, Waitzberg and MerkurRosen, Waitzberg & Merkur, 2015; Reference RiceRice et al., 2013), compared to, for example, Belgium and the Czech Republic (Alexa et al., 2014; Reference Gerkens and MerkurGerkens & Merkur, 2010). We begin by briefly discussing the theoretical framework underpinning insurance choice and competition. We then describe the systems of insurance choice in place in the six countries, along with the types of choice available to the population and the tools to support choice. Subsequent sections explore the evidence about the degree to which people exercise choice of insurance and their use of available support tools; the underlying motivations for exercising choices; the nature of the choices made (that is, whether people make choices that are in their best interest); and the frequency with which people change insurers. We then explore the impact of choice policies on care quality and satisfaction, and on the development of more person-centred care arrangements. We conclude by providing lessons for countries that may be contemplating introducing insurance choice into their system.

Insurance choice and competition: theoretical considerations

The conceptual basis for introducing competition between insurance companies is often attributed to the American economist Alain Reference EnthovenEnthoven (1978; Reference Enthoven1993). Originally Enthoven referred to consumer-choice health plans, emphasizing the role of consumer choice in driving efficiency, but subsequently described the concept as ‘managed competition’. This underlines the key role ascribed to a regulatory framework to ensure that insurer competition achieves socially desirable outcomes, namely improved quality and economic efficiency and minimizes ‘cream skimming’, that is, selection of low-cost customers. Regulation is also necessary to help ensure that the system provides equitable access to coverage and care. This is usually achieved through risk adjustment (see below), the explicit definition of an essential basket of benefits, and, where necessary, subsidies for customers to purchase insurance who would otherwise not be able to do so because of, for example, low income.

Insurance competition relies on the interplay between three sets of stakeholders: consumers, providers, and insurers (Reference Van Ginneken and SwartzVan Ginneken & Swartz, 2012). Insurers are assumed to compete for customers based on the quality of the care (arrangements) they purchase and the customer services they provide, as well as the premiums they charge. In such a market, providers in turn are assumed to compete with other providers for contracts with insurers by offering quality services at reasonable cost. People are expected to choose insurers and providers based on the quality and convenience of the services offered. They may also select an insurer based on the quality of their purchased care. As noted above, a risk adjustment mechanism would define compensation payments for different ‘insurance risks’ so that insurers that have a high proportion of high-cost customers are not disadvantaged, reducing incentives for insurers to enrol low-cost customers only (Reference Van de Ven, van Kleef and van VlietVan de Ven, van Kleef & van Vliet, 2015). Each of these elements forms a critical part of the theory, but in practice countries that are considering a system of competing health insurers may choose not to use some of these elements. For example, a country might introduce a system of competing insurers, but competition would be permitted on the basis of quality only (and not price) or they may not be allowed to selectively contract with particular providers.

In this chapter, we focus on the relationship between customers and insurers. This relationship is a strong driver for insurance competition because, in theory, competing insurers would be expected to lose customers if they do not ensure good quality care and services at acceptable cost. This theory then assumes that customers are informed about differences in quality and costs and that they are willing to act (switch insurer) based on this information. The following sections illustrate the degree to which these assumptions are realized, or indeed are realizable, in practice by looking at the experiences in six multiple-insurer systems that introduced choice and competition.

Insurer choice and competition in Europe, Israel and the USA

Germany, Israel, the Netherlands, Slovakia and Switzerland, all countries with multiple insurers, have to varying degrees introduced choice and competition among insurers in their health systems from the 1990s onwards. This has also included providing insurers with more tools to purchase care (Table 9.1). It was hoped this move would stimulate improved efficiency in health care and better respond to people’s preferences. The USA has seen a somewhat different trajectory in that choice and competition formed the central tenets of the private health insurance market, which is characterized by less regulation than that in other countries, and which covered 49% of the population in 2016 (Kaiser Family Reference FoundationFoundation, 2018). However, similar to the European settings reviewed here, choice and competition were also successively introduced into public schemes such as Medicaid and Medicare from the 1990s onwards.

Table 9.1 Overview of insurance choice in Germany, Israel, the Netherlands, Slovakia, Switzerland and the USA (2017)

| Funding source | Number of insurers | Market concentration | Selective contracting allowed? | Insurers negotiate prices | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germany* | Income-dependent contributions | 113 statutory health insurance (SHI) funds | Five largest SHI funds hold 50% of statutory insurance market | Yes (for integrated care programmes) | Only pharmaceuticals |

| Israel | Taxes and income-dependent contributions | Four health plans | Largest insurer holds about 54% of the market | Yes | Yes |

| Netherlands | Income-dependent contributions (employers), community rated premiums (citizens) | 26 health insurers | Four health insurers hold about 90% of the market | Yes | Most hospital care |

| Slovakia | Income-dependent contributions | Three health insurers | Largest insurer holds about 63% of the market | Yes | Yes |

| Switzerland | Community rated premiums | 58 health insurers | Four insurers hold about 56% of the market | Yes (for managed care plans) | Yes (managed care insurance plans) |

| USA** | Premiums/ contributions | 1300 health insurance companies | Varies according to type of insurance (e.g. Medicare, private) | Yes | Yes |

Note: * only statutory insurance schemes, **total market for private insurance

In Germany, choice of insurer (statutory health insurance (SHI) fund) was introduced by the 1993 health reform. From 1996 people who were previously assigned an SHI fund based on their profession or region of residence were able to freely choose an SHI fund of their choice. At the time there were considerable differences in contribution rates between different SHI funds, ranging between 9% and 18% of gross monthly salary (Reference BusseBusse et al., 2017). Therefore, a risk-equalization mechanism (RSA scheme) was introduced simultaneously to ensure that SHI funds that covered a larger share of older people were not disadvantaged because of the higher costs of their customer base. The RSA scheme was further refined in 2009 to also incorporate morbidity into the reallocation formula. All SHI funds are required to offer a minimum benefits package, and the insured population has, in principle, free choice of hospitals and office-based physicians in ambulatory care. The number of SHI funds has fallen considerably since the mid-1990s, from some 960 funds in 1995 to 113 in 2017, because of mergers, mostly within groups of SHI funds (e.g. regional funds). In 2016 the five largest funds insured almost 50% of the population (Statista, 2017a). Prices of most services are determined by nationally agreed fee schedules, but insurers can negotiate lower prices for pharmaceuticals, and larger funds have greater leverage in these negotiations. Provisions for selective contracting were introduced in the early 2000s and were initially , although this stipulation was broadened with the 2015 health reform which introduced other forms of selective contracting to strengthen care coordination in the system.

In Israel, the health insurance system emerged from originally four non-profit health insurers (Health Plans, HPs) that were established between 1920 and 1940 by political parties or trade unions and that insured their members and provided medical services. The planning, regulation and supervision of the HPs was subsequently (1948) taken on by the Ministry of Health, which also began to provide selected health services and operate hospitals. Although health insurance was still voluntary, by 1995 almost all citizens (96%) had insurance, with the insurer Clalit holding a 62% share of the market. At that time HPs could define the range of benefits offered, as well as premiums; they were also able to select applicants (Brammli-Greenberg, Waitzberg & Gross, forthcoming). This changed with the 1995 national health insurance (NHI) law, which provided for universal coverage and sought to combine progressive financing (through taxes) and competition in an equitable and sustainable manner. The NHI law established health (and health insurance) as a right for all citizens and permanent residents and guaranteed full freedom of choice among the four HPs (Reference Rosen, Waitzberg and MerkurRosen, Waitzberg & Merkur, 2015). Since then, the four competing HPs are responsible for providing and managing a broad benefits package specified by government. Within the public system, HPs provide care (as listed in the NHI benefits package) in the community and they may purchase selectively inpatient and outpatient care from hospitals. Residents are not able to opt out of the NHI system. HPs do not compete on the level of price but on the basis of quality of care and service quality, as well as on a co-payments rate (which must be approved by the Ministry of Health) and voluntary health insurance (VHI) packages.

The Netherlands moved in 2006 from a social health insurance system that covered about two-thirds of the population, and in which people with incomes above a certain threshold purchased private health insurance, to one of managed competition. This move aimed to reduce the emphasis on government regulation of health care supply, increase efficiency through strategic purchasing and, ultimately, offer more affordable and more patient-driven health care (Reference ThomsonThomson et al., 2013). Health insurance covers a comprehensive set of benefits for acute care. All residents are required to purchase statutory health insurance from private insurers, and insurers must enrol all applicants. Insurers compete on price for insurance policies, which cover a comprehensive set of benefits for acute care. Insurers can offer lower premiums for basic health insurance in exchange for charging higher voluntary deductibles; the level of these deductibles is set by government and they are in addition to the mandatory deductible all adults have to pay. The 2006 health reform also considerably increased the possibilities for health insurers to selectively contract with health care providers and so offer restricted or preferred provider insurance packages at a lower cost. The role of this type of policy is increasing but it remains small in terms of uptake. Some insurers waive the cost of the mandatory deductible if preferred providers are chosen. Furthermore, those with lower incomes are eligible to receive tax subsidies. The introduction of insurer competition led to a wave of mergers and acquisitions of insurance funds and by 2016 just four insurers held about 90% of the market (Vektis Reference ZorgthermometerZorgthermometer, 2016).

In Slovakia, insurance competition was gradually introduced between 2002 and 2006. A controversial reform, it established private insurers as purchasers of health care services and made them responsible for ensuring health care to their insured population. The reform aimed at more effective utilization of resources, to improve fairness and financial sustainability, as well as transfer responsibility for the health system from the state to the individual, health insurers and providers (Reference SmatanaSmatana et al., 2016). Ownership regulation allowed both the state and the private sector to be shareholders of health insurance companies. Changes in the insurance market led to increased consolidation through mergers, from seven health insurance companies to three in 2017: the state-owned Všeobecná ZP (General health insurance company), and two privately owned insurers (Dôvera and Union). Insurers do not compete on price and, as the benefits basket is quite comprehensive, there is also limited scope for insurers to compete for patients through, for example, offering additional benefits. Purchasing is based on selective contracting and health insurers can develop their own payment methods and set up their own pricing policy towards contracted providers (Reference SmatanaSmatana et al., 2016).

In Switzerland, the 1996 health reform sought to enhance equity of access to health insurance, to strengthen solidarity and to create incentives for organizational innovation and expenditure control (Reference ThomsonThomson et al., 2013). The 1996 reform stipulated that all Swiss residents must purchase basic health insurance, which covers a comprehensive basket of goods and services defined at the federal level. The insurance market is not as concentrated as it is in the Netherlands as noted above, and in 2016 four insurers held 56.3% of the market (Statista, 2017b). Insurers can offer several ‘basic’ policies with standardized benefits; premiums are lower for insurance policies with higher deductibles and those that only cover managed care. All insurers are private; they must be non-profit-making (although they can make profits from selling complimentary and supplementary policies) and they must accept all applicants for membership during specified open-enrolment periods. The cantons (states) provide income-dependent tax subsidies to compensate those on low incomes (Reference De PietroDe Pietro et al., 2015; OECD/WHO, 2011; Reference Van Ginneken, Swartz and Van der WeesVan Ginneken, Swartz & Van der Wees, 2013). Similar to Germany, collective contracting remains the dominant approach to purchasing care, and competition between providers for contracts with insurers is limited. However, there is a possibility for selective contracting within managed care arrangements, the number of which is increasing rapidly. Thus, in 2014 about 24% of the insured population were enrolled in some form of managed care plan, involving some 75 physician networks or health maintenance organizations (HMOs), up from about 8% in 2008 (Ärztenetzerhebung, 2014). There are also network health insurance plans in which insurers determine a list of physicians that patients can consult, while Telmed models require patients to have a telephone consultation with a medical call centre first before they may arrange an appointment with a medical doctor in ambulatory care. In total, these ‘alternative’ forms of contracts accounted for 63% of all contracts in 2014 (BAG, 2016c).

In the USA, the largely unregulated private insurance market for employer-based insurance mainly includes three categories of private insurer, namely health maintenance organizations, preferred provider organizations, and high-deductible health insurance plans (Reference RiceRice et al., 2014). As noted, in 2016 some 49% of the population were covered through their employer by a private health insurance. In addition, Medicare, the public insurance programme for people aged 65 years and older and for disabled persons, covered 14% of the population, while Medicaid, which covers those under a certain income threshold, covered 19% (Kaiser Family Reference FoundationFoundation, 2018). The 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA) introduced major insurance coverage expansions from 2014, and this has increased the share of the population with insurance. Provisions included the requirement that most Americans purchase health insurance (subsequently repealed, effective as of January 2019); the introduction of health insurance market-places, or exchanges, which offer premium subsidies to people with lower and middle incomes; and the expansion of Medicaid in many states, which involved raising the income threshold for eligibility to increase coverage for low-income adults. The state-based exchanges can be seen as a first attempt to establish managed competition in the individual insurance market in that all health plans sold through this marketplace must meet minimum standards (‘essential health benefits’). Their structure and supporting regulation resemble the Dutch and Swiss regulated insurance models (Reference Van Ginneken and SwartzVan Ginneken & Swartz, 2012; Reference RiceRice et al., 2014). The Medicaid expansion and the exchanges (along with other provisions) together are colloquially referred to as Obamacare. Insurers negotiate prices with provider groups for services provided by in-network providers. There is a large number of insurers in the USA who offer an even larger number of insurance policies. Generally, there is an open enrolment period once a year, and people can switch insurer during that period. With a few notable exceptions (i.e. state-based health insurance exchanges), private health insurance policies are rarely standardized.

Type of choice and tools to support choice

Table 9.2 provides an overview of the types of choice offered in the reviewed countries. Slovakia offers the least choice, such that people can choose the insurer only. The Netherlands and Switzerland offer a greater level of choice, in that people may choose the insurer, the premium level and predefined levels of deductibles (and so pay a lower premium overall). Insurers in these countries also offer various (risk-rated) VHI policies, which they can use, in theory, to attract people to (or deter them from choosing) the basic insurance package they have to offer. Furthermore, as noted above, both countries allow limited network (preferred provider-type) health insurance policies, which offer restricted provider choice for a lower premium. In Germany, people have somewhat greater choice among SHI funds, with insurers permitted to charge a supplementary (income-dependent) premium above the legally set contribution rate (14.6% of gross monthly salary from 2015, shared equally between employers and employees), although in reality the differences in rates are comparatively small, ranging from 14.9% to 16.3% in 2018 (Krankenkassen Reference DeutschlandDeutschland, 2018). SHI funds may also offer benefits in addition to the statutory benefits package. Furthermore, people can choose optional insurance policies, for example covering disease management programmes, optional deductibles in exchange for a bonus, or no-claims policies. In 2016 about 25% of people with statutory insurance had opted for one of these optional policies (GBE, 2017).

Table 9.2 Type of choice in basic insurance in Germany, Israel, the Netherlands, Slovakia, Switzerland and the USA

| Insurer | Insurance premium/contribution level | Fixed or minimum benefit package | Cost-sharing requirements | Basic insurance providers also offer VHI | Limited network (preferred provider) policies available | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germany | Yes | Yes | Minimum | Bonus plans (e.g. deductible in exchange for bonus) | Yes | No |

| Israel | Yes | Not applicable | Minimum | Co-payment rates | Yes | No |

| Netherlands | Yes | Yes | Fixed | Deductible level (in exchange for lower premium) | Yes | Yes (budget policies) |

| Slovakia | Yes | No | Fixed | No | No | No |

| Switzerland | Yes | Yes | Fixed* | Deductible level (in exchange for lower premium) | Yes | Yes (managed care insurance plans) |

| USA | Yes | Yes | Varies | Varies | Yes* | Yes |

Note: *Mainly Medicare (Medigap)

In Israel, residents have a choice of insurer, additional benefits, cost-sharing levels and (community rated) VHI policies. For example, health plans may offer services or cover drugs that go above and beyond the legally mandated benefits package that all health plans have to offer, although individuals may not be aware about the differences between the ‘voluntary’ benefits offered by insurers. Individuals can also choose among different co-payment rates offered by health plans. There are slight differences among insurers, but here too individuals may not be very aware of them.

Among the countries reviewed here insurance choice is greatest in the USA. With a few notable exceptions, insurance benefits covered by private insurance policies vary considerably and people are therefore required to trade-off price (premium level), cost-sharing requirements (deductibles, co-payments, co-insurance), benefits and prescription drugs covered, as well as breadth and quality of provider networks covered by the individual plan. The public insurance scheme Medicaid is a jointly administrated state–federal programme and insurance choice options (if any) may vary from state to state, with some but not all offering Medicaid beneficiaries a choice of insurer as part of managed care plans that restrict choice of providers within their networks. In the public Medicare programme, beneficiaries may choose between private sector Medicare (Medicare Advantage) or traditional Medicare (federal government-administered). Medicare beneficiaries also have the option to purchase supplementary VHI policies (known as Medigap plans) to cover costs not covered under the regular (original) Medicare, and these offer varying benefits, co-payments and deductibles (Reference RiceRice et al., 2013).

The reviewed countries have introduced a range of tools both to support consumers in making informed choices and to avoid market failures due to information asymmetries. For example, in 2014 the Israel Ministry of Health launched a website, Call-Habriut, which provides independent, open and up-to-date information about insurance options, including VHI (benefits, eligibility conditions, co-payments set by HPs and VHI, etc.). There are plans to also include information about for-profit VHI, and to offer this information in additional languages such as Arabic and Russian. The launch of the website was accompanied by an advertising campaign for the public. The aim is to enhance people’s knowledge of and awareness about their rights and eligibility to benefits, and so enable them to demand these from insurers; if refused, they can refer the case to the Ministry of Health.

In Germany, the Netherlands and Switzerland, webportals operated by private non-profit or for-profit organizations are the most important sources for comparative information about health insurers. They provide tailored information on insurance options, including benefits covered, contribution rates and VHI options. In the Netherlands, the government-operated portal KiesBeter.nl (‘Choose better’), set up in 2005 to assist service users to choose between different health care providers, previously also provided independent information on health insurance policies but this was discontinued from 2013, based on the argument that there was a sufficient number of alternative, independent webportals available providing these data. This move was followed by some debate, with newspaper reports on widely differing recommendations for health insurance policies by different webportals using the same service user profile, highlighting that people may not be able to judge the degree to which these portals are indeed independent (Reference Van Ginneken, Wismar, Greer and FiguerasVan Ginneken, 2016). In Switzerland, the government’s online portal also provides general information on health insurance, but a more widely used source is comparis.ch, a leading commercial Swiss online portal providing comparative information on a range of services, including health insurance. Comparative information is freely accessible; health insurers pay a commission in the range of CHF 40–50 (€37–46) for every request for a quote through the comparis portal (Comparis, 2017). In Germany, there are various webportals hosted by different organizations, including those providing general service comparisons (e.g. check24 and verivox), as well as portals providing comparative information on health insurance specifically (e.g. krankenkassen.de and krankenkassenvergleich.de).

In the USA, there is a range of webportals providing comparative information on employer-based insurance policies (especially for large employers) and Medicare; these portals also provide some data on patient satisfaction. Employers often act as agents for their employees by providing information about provider quality on a webportal and they may coordinate with insurers to encourage employees to utilize recommended preventive care. Many of the aforementioned state-based health insurance exchanges that were established under the ACA also provide webportals and tools to support consumer choice. The quality of navigation tools, particularly those offered by employers, varies greatly. Both Medicare and the health insurance exchanges provide extensive tools to compare both the cost and the quality of insurance options. For example, the Medicare Part D Plan Finder, used by beneficiaries to choose prescription drug coverage, arrays plan choices from lowest to highest total estimated annual costs, and provides quality measures through a star rating system based on a number of measures grouped into five categories: staying healthy through screening tests and vaccines, managing chronic conditions, member experience with the health plan, member complaints and customer service (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2016). The insurance exchanges, which target a more vulnerable population, use so-called navigators to help consumers as well as small businesses and their employees in their search for health insurance policies. They also assist in completing eligibility and enrolment forms; the information and support tools are required to be unbiased and free to consumers.

Slovakia is the only country among those reviewed where a dedicated website to help people choose health insurance has not been established. This is perhaps due to the limited scope of choice. The Health Care Surveillance Authority, which among other things is responsible for supervising public health insurance in Slovakia, publishes data on waiting times for all specialties and individual insurers that people may use to make their decision.

Do people use available tools to support choice and do they exercise choice?

Much of the literature on how people exercise choice of health insurer originates from the USA, but there is also increasing evidence from the Netherlands and Switzerland. An important consideration is understanding whether people know how to exercise choice in the first place and how to move (switch) between insurers in practice. This requires knowing where to find relevant information, which, given that webportals are the prime source for information as noted above, may be especially challenging for people who do not have access to the internet or who are not able to use it (Reference Sinaiko, Eastman and RosenthalSinaiko, Eastman & Rosenthal, 2012). Evidence further suggests that webportals should offer simple options, because too many options may be overwhelming and lead to confusion and inertia (staying with the same insurer), as has, for example, been documented for Switzerland (Reference Frank and LamiraudFrank & Lamiraud 2009) and the USA (Reference HanochHanoch et al., 2011; Reference BarnesBarnes et al., 2012; Reference Zhou and ZhangZhou & Zhang, 2012; Reference Abaluck and GruberAbaluck & Gruber, 2013).

Indeed, in Switzerland in 2013 there were 58 insurers offering about 287 000 different insurance policies, with options varying by region (canton), the type of policy (e.g. managed care or combined accident insurance), and price, including the level of the (voluntary) deductible or whether it offers a no-claims bonus (BAG, 2016a; BAG, 2016b). In the Netherlands, the 26 health insurers (2014) offer 71 policies, which increases to 5940 insurance combinations when also considering VHI policies and deductible options (NZA, 2016). The Medicare Advantage programme in the USA varies by geographic area, averaging 19 insurers in 2016 (Kaiser Family Reference FoundationFoundation, 2018) but as benefits are not standardized above a legally defined minimum benefits basket it is difficult to compare the relative value of the resultant variable insurance policies on offer. The state-based insurance exchanges offer various choices, ranging from a single insurer in five states to 15 insurers in Wisconsin in 2015 (with typically 67 insurance policies from which people can choose) (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2016). Conversely, in Slovakia and Israel people can only choose between three and four insurers, respectively.

Information on whether people exercise choice of insurer can be inferred from the rate of switching between insurers. Generally, the evidence suggests that switching rates range between a low of under 2% of the insured population in Israel (Ministry of Health, 2016b) to about 5–10% in Switzerland (FOPH, 2014). Switching rates tend to be high directly following the introduction of choice policies creating a (temporarily) volatile market, such as observed in Israel during 1995–97 subsequent to the 1995 NHI law and in the Netherlands after the 2006 health reform. However, usually switching rates fluctuate only within a limited range. For example, in the Netherlands from 2011 switching rates varied between 5.5% and 8.2% (Vektis Reference ZorgthermometerZorgthermometer, 2016), although it should be noted that the majority of people in the Netherlands switch as part of a collective group, that is, not as a result of their individual choice but rather that of their employer. Thus, at individual level rates have fluctuated between only 1.6% and 2.6% during the same period. In Slovakia, switching rates have been below 5% since 2007 (Reference SmatanaSmatana et al., 2016), while in the USA, switching between Medicare Advantage insurers appears to be within a similar range as those seen in Switzerland (Reference RiceRice et al., 2014). In Germany, official data on switching between SHI funds are not available. A survey of just over 2000 insured people in 2015 found that only 3.2% had switched their SHI fund in the preceding year, with another 3% seriously considering doing so (Zok, 2016). However, it is important to note that some 40% of respondents reported to have switched their SHI fund in the past.

Interpreting switching rates remains challenging. Low rates could be taken to mean that insurance competition is not effective in achieving the goal of improved quality and cost of care. At the same time, high rates could imply increased transaction costs and prices, and, more importantly perhaps, they might discourage investment by insurers in health promotion and prevention, or the development of care programmes. Yet from the insurers’ perspective, the prospect of even a small proportion of people switching to another insurer could trigger action to counteract people leaving. It is therefore important to understand which factors matter to people when they decide to switch insurer and whether switching rates impact on care quality and cost.

Who switches insurance policy and what are their motivations for doing so?

Empirical evidence from Germany, the Netherlands, Switzerland and the USA shows that people who switch insurers are mostly likely to be young, male, healthy and well-educated (Reference Boonen, Laske-Aldershof and SchutBoonen, Laske-Aldershof & Schut, 2016; Reference ThomsonThomson et al., 2013; Reference Rooijen, de Jong and RijkenRooijen, de Joong & Rijken, 2011; Reference Lako, Rosenau and DawLako, Rosenau & Daw, 2011), although there are exceptions as the experience from Israel demonstrates (Box 9.1).

Box 9.1 Observed health insurance switching patterns in Israel

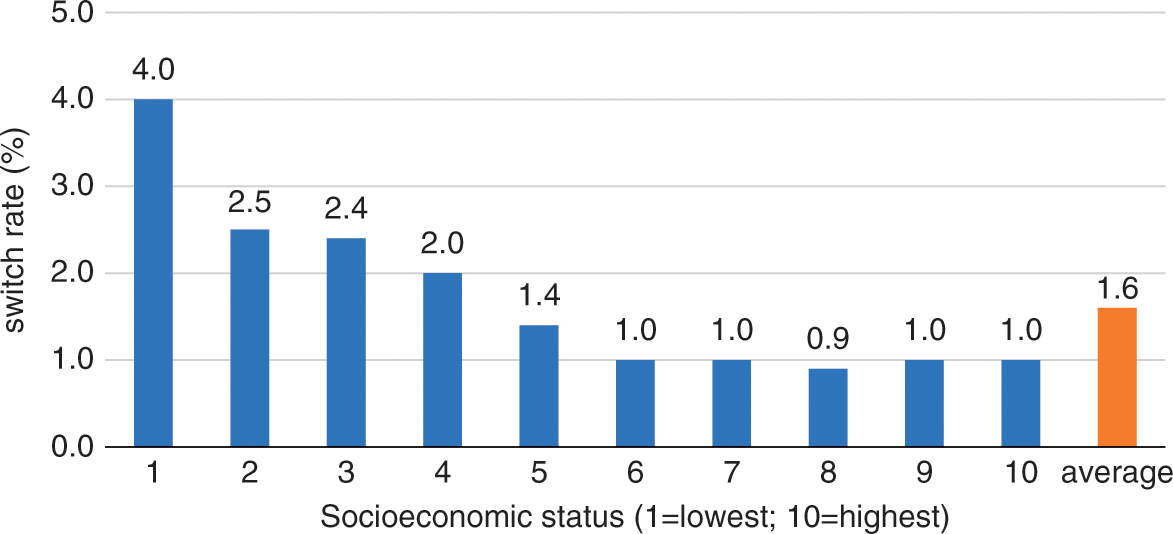

In Israel, data from the Ministry of Health show that unlike in other countries, switching between insurers is relatively more common among lower-income individuals (Figure 9.1). This was first observed by Reference Shmueli, Bendelac and AchdutShmueli, Bendelac & Achdut (2007) who found that in 2005–06 young people were more likely to switch insurer, as well as people on lower incomes, and those receiving income maintenance or unemployment benefits (controlling for age and gender). Switching rates were also found to be higher for persons who had a greater number of children under the age of 18 years. The authors explained these observations by implicit risk-selection strategies inherent in the risk-adjustment system, in which children represent a “predictable profit” under the formula which overcompensates for this age group.

Figure 9. 1 Switch rates in Israel by socioeconomic status (SES) of place of residence, 2015 (1 = lowest SES, 10 = highest SES)

Available evidence suggests that where people do exercise choice by switching between insurers, this appears to be rarely motivated on the basis of quality of contracted care (providers). Table 9.3 summarizes the findings of a range of studies carried out in Israel, Germany and the Netherlands that have sought to understand the reasons for switching insurers among the eligible population. Thus, the main reasons included dissatisfaction with the services provided by the current insurer, the range of benefits covered, and price. Data from 2016 from Israel also provide insights into reasons for staying with the current insurer. Some 13% of respondents to a national survey (aged 22 years and over) indicated that they had considered switching insurers in the preceding year but ultimately remained in the health plan. The main reasons for not switching included: administration (switching procedure and loss of rights) (52%); thought that all health plans are the same (11%); wanting to remain with their physician (9%); proximity to health plan’s clinic (7%); satisfaction with staff and services (6%); wanting to remain in the same health plan as their family (5%); waiting times for specialists (5%); uncertainty about the continuity of benefits/eligibility and the price of supplemental VHI offered by other health plans (4%); and about the value of switching (2%) (Brammli-Greenberg, Medina-Artom & Yaarj, 2017).

Table 9.3 Reasons for switching insurer

| Country | Reasons for switching (% of respondents, where applicable) |

|---|---|

| Israel (2016)a |

|

| Germany (2015)b |

|

| Netherlands (various years)c |

|

There is only limited evidence from Slovakia, with some suggestion that waiting times for selected procedures can potentially influence choice. However, many people choose the state-owned General health insurance company as it is perceived to be the least likely to ‘skimp’ on the quality of reimbursed care (Reference SmatanaSmatana et al., 2016).

In the USA, a small number of studies examined the role of quality information included in health care report cards on choice of insurer and of provider. They found that report cards most commonly impact on the quality of services provided by health insurers but not necessarily on the quality of care delivered by contracted providers. Impacts are not large, however, and any effects will be limited to those who make use of the information presented in report cards (Reference Rice and UnruhRice & Unruh, 2015).

As indicated by the data from Israel reported above, one important consideration for the decision to switch insurer involves arrangements for (supplementary) VHI on offer, an issue of concern for people in the Netherlands and Switzerland also. In Israel, although VHI policies are community rated, individuals may refrain from switching insurers to avoid losing access to covered services, because this generally involves a waiting period of up to 12 months after purchasing VHI. The latter has recently been rectified in that insurers allow for enrolment in VHI without restricting access to benefits by means of a waiting period. In the Netherlands and Switzerland people with VHI may be reluctant to switch insurer out of concerns that they will not be able to access similar VHI benefits from another insurer of a comparable price and comprehensiveness (Reference Dormont, Geoffard and LamiraudDormant, Geoffard & Lamiraud, 2009; Duijmelinck & van de Ven, 2014).

Do people make ‘good’ choices?

Several studies have examined the degree to which people make choices of insurer that serve their own interest with regard to price and care quality. However, as noted earlier, in most settings exercising informed choice requires a good understanding of a myriad of insurance terms such as deductibles, co-payments, out-of-pocket maximum, and managed care, along with the range of benefits covered (health insurance ‘literacy’).

Studies set in the USA showed only low to moderate levels of health insurance literacy among the adult population (Reference LoewensteinLoewenstein et al., 2013; Reference McCormackMcCormack et al., 2009). For example, a survey of adults aged 25–64 years found that only 11% of respondents could correctly answer an open-ended question about out-of-pocket liability from a hypothetical four-day hospital stay; respondents were provided with an overview table of benefits and the authors deemed the question to be “relatively simple” compared to other questions (Reference LoewensteinLoewenstein et al., 2013). In Israel, a national cross-sectional survey of a random sample of the Jewish and Arab population found that knowledge about supplementary VHI contents and terms was generally low (Reference GreenGreen et al., 2017).

As noted above, quality of contracted care seems to play a minor role when individuals make insurance choices and studies investigating whether people that use care quality information make insurance choices to their advantage are lacking. Although cost appears to play a greater role, the literature suggests that people do not always appear to make optimal choices on the basis of price, and they may choose a more expensive insurance policy than needed. Moreover, people tend to pay more attention to the level of insurance premiums instead of trading this against cost-sharing requirements. While it may be the case that some people knowingly choose to pay higher premiums at the price of a lower deductible, it is likely that most do not act in their best interest (Reference Bhargava, Loewenstein and SydnorBhargava, Loewenstein & Sydnor, 2015; Reference Gaynor, Ho and TownGaynor, Ho & Town, 2015; Reference Zhou and ZhangZhou & Zhang, 2012). For example, Reference Van Winssen, van Kleef and van de VenVan Winssen, van Kleef & van de Ven (2015) estimated that nearly half of the Dutch population would be financially better off if they had chosen a voluntary deductible (on top of the mandatory deductible), but in 2014 only 11% had done so. Cost considerations and trade-offs will be of less concern in Israel and Slovakia, where insurance policy options do not involve large financial incentives.

Has insurance choice led to novel person-centred care arrangements (and for which group of people)?

The question about whether insurance choice has encouraged insurers to invest in more person-centred services can be answered at two levels: first, whether insurers have tailored their customer services and health insurance policies to (certain) population groups and in what way, and second, whether insurers have organized and purchased new care arrangements for (defined) population groups.

In response to the first point, available evidence shows that in all reviewed countries, insurers have sought to tailor their services and (additional) benefits to attract certain groups of people, through, for example, offering special membership rates for diabetes patient groups. Risk-adjustment schemes play a key role in making certain population groups more attractive to insurers and thus increasing the likelihood of a tailored policy and care arrangements. For example, the risk-adjustment scheme in place in Israel only considers age, gender and place of residence and, as we have noted earlier, the capitation formula overcompensates people with a greater number of children and older men, and undercompensates older women (Reference Brammli-Greenberg, Waitzberg and GlazerBrammli-Greenberg, Waitzberg & Glazer, 2017). As a consequence, insurers in Israel compete for children and men, and they have developed and enhanced their offers of specific services for children, such as developmental tests and treatments, and mental health services. Moreover, insurers advertise to attract large young families in particular (Reference ShmueliShmueli, 2015). Conversely, the risk-adjustment systems disincentivizes attracting older women while possibly incentivizing ‘skimping behaviour’, meaning that they reimburse fewer services, although until now there is no hard evidence that such behaviour is realized in practice.

In the Netherlands, where a more sophisticated risk adjustment system has been implemented (Reference Van Ginneken, Swartz and Van der WeesVan de Ven et al., 2013), several strategies are being used to attract certain population groups. For example, while previously insurers could negotiate collective group contracts with employers only, the 2006 health reform introduced the possibility to also negotiate collective contracts with any group of individuals directly (following successful lobbying by the Dutch Patients Federation). By the end of 2007, two years after the implementation of the health reform, patient groups had negotiated around 40 collective contracts (Reference Van Ginneken, Busse and GerickeVan Ginneken, Busse & Gericke, 2008), and this number had risen to 155 in 2015 (NZA, 2016). However, some (often smaller) chronic disease patient groups did not manage to secure a collective contract. This means that the risk adjustment scheme only inadequately compensates for these groups of patients to make them sufficiently attractive for insurers. It has been estimated that in 2014 insurers were undercompensated by an average of €331 per person per year for the 31% of the population who reported at least one chronic condition (Reference Van de Ven, van Kleef and van VlietVan de Ven, van Kleef & van Vliet, 2015).

In Slovakia, the two privately owned insurers also focus their marketing efforts on the young and healthy (Reference SmatanaSmatana et al., 2016). They have also introduced policies covering prevention and maternity care in an attempt to attract women specifically and to encourage them to register their newborn babies with them. These initiatives are, however, quite limited and not rolled out nationally.

Evidence in support of the question of whether insurance choice has led to the organization and purchasing of more person-centred care arrangements is difficult to assess. In Switzerland, the emergence and strong growth of managed care insurance policies (including HMOs and physician networks) could be seen as the result of insurance choice. Yet it is equally plausible that the risk-adjustment system in place does not sufficiently take account of the risk of ill health in the Swiss population since insurers are able to offer cheaper managed care type insurance policies to the young and healthy, while people at higher risk of ill health tend to remain covered by traditional health insurance policies (Reference BeckBeck et al., 2010). In the Netherlands, an evaluation found that insurers are reluctant to invest in more appropriate care models for high-cost (mostly chronic) patients (KPMG, 2015), yet it is this group that is most likely to benefit from more integrated care arrangements. In general, lack of investment in appropriate care models for high-cost patient groups is difficult to prove as it is unknown whether insurers would act differently if the incentive system was structured in favour of ‘high risks’ (Reference Van de Ven, van Kleef and van VlietVan de Ven, van Kleef & van Vliet, 2015).

In Slovakia, the private insurer Dovera implemented the MediPartner project that virtually integrated general practitioners (GPs) with the rest of the network of providers, and gave GPs a virtual budget to manage patients along the care pathway. The project was piloted in certain regions in the eastern part of Slovakia and although it achieved significant cost savings, these were often allegedly associated with under-provision of care; for example, GPs received a bonus if they did not refer patients upwards.

Most reviewed countries are increasingly experimenting with disease management programmes, managed care arrangements and integrated care initiatives more broadly, with the goal of providing more person-centred care, but these experiments are not necessarily linked to, nor indeed emerged as a result of, insurance choice. For example, in Germany the introduction of disease management programmes in 2002 was mandated by law as a means to improve the quality of care for people with chronic disease, in particular the prevention of long-term consequences and complications, and to ultimately reduce the costs of care (Reference Nolte and KnaiNolte, Knai & Saltman, 2014). Elsewhere, relevant approaches also typically had improvement of quality of care at their core, while frequently also aiming to enhance efficiency and, in some instances, reduce utilization and costs. The USA has seen an increase in accountable care organizations, encouraged by provisions in the 2010 Affordable Care Act. Accountable care organizations are consortia of providers who agree to work together to coordinate care for patients across health systems and settings. While initially implemented in the context of Medicare, they are becoming increasingly common in the private insurance sector as well (Reference BarnesBarnes et al., 2014).

Does insurer choice or competition lead to improved patient satisfaction or better care quality?

It has been suggested that countries with social health insurance systems are more responsive to people’s expectations and show higher satisfaction levels when compared to countries with tax-funded systems (Reference Busse, Figueras and McKeeBusse et al., 2012). Clearly, this is not seen to be the result of the funding mechanisms or levels per se, but is based on the assumption that countries with social health insurance place more emphasis on consumer orientation, which includes choice of provider and purchaser, clearly defined entitlements and patient rights (Reference Busse, Figueras and McKeeBusse et al., 2012). It is not possible to say how much insurance choice contributes to this difference, and it may well be caused by other factors. These generalizations, therefore, should be made with great caution as considerable methodological issues remain with regard to the measurement and interpretation of satisfaction and lack of standardization of this term across countries, regions and even insurers.

The countries reviewed have a tradition of insurance choice and competition, which perhaps explains why no studies have looked at whether (increased) choice has led to improved patient satisfaction or care quality. Most insurers in most countries monitor satisfaction with their services, and satisfaction levels generally seem to be quite high (Reference BusseBusse et al., 2017; Reference De PietroDe Pietro et al., 2015; Reference KronemanKroneman et al., 2016; Reference RiceRice et al., 2013; Reference Rosen, Waitzberg and MerkurRosen, Waitzberg & Merkur, 2015; Reference SmatanaSmatana et al., 2016). Earlier sections of this chapter have shown that where choice is exercised, this is often not based on considerations of quality, which can lead to opting for insurance policies that are not necessarily in people’s best interest. Therefore, it is doubtful that the signals that are given by those switching will stimulate insurers to organize and purchase higher quality care. It could perhaps be argued that risk adjustment systems in place are more relevant in terms of ensuring that insurers contract for quality of care for certain groups than choice and competition. Indeed, systems could provide incentives for insurers to focus on specific population groups, although as a sole mechanism this is unlikely to automatically increase the quality of care.

Conclusions

Choice is valued by people and can contribute to ensuring that insurers offer better consumer services. But overall, there is little evidence that supports the notion that insurance choice has led to higher quality care or was a pivotal factor in the emergence of person-centred care arrangements in the six countries reviewed in this chapter. Available evidence points to the difficulty that people face in making informed insurance choices. Although switching rates are generally low, they should be sufficient to ‘nudge’ insurers in a certain direction if people exercise choice on the basis of the quality of the care covered by the insurance policy. This is not the case, however, given that the quality of contracted care as part of a given health insurance policy continues to play only a marginal role in the selection of insurer. This could change if more meaningful data on the quality of care became available and if they were presented in a transparent and easy-to-understand manner that would allow people to make better-informed choices. Even in terms of the cost of a given insurance policy, which is more often a factor in switching, evidence shows that people do not tend to select the highest value insurance plan. Indeed, the many insurance options and concepts in some countries require a level of health insurance literacy that may not be present. For these reasons, it is doubtful whether the signals given by the switchers are sufficient to motivate insurers to purchase better quality care.

At best, insurance choice may have led to increased satisfaction of patients with the services of their insurers and perhaps better-tailored health insurance policies in terms of benefits and services offered. It should be noted, however, that risk-adjustment plays a key role and the way the risk adjustment system compensates for certain population groups may be a more important factor in determining the range of policies offered by insurers, rather than insurance choice as such. Even in the Netherlands, which has one of the most sophisticated risk adjustment schemes (Reference Van de VenVan de Ven et al. 2013), there are identifiable population groups that remain less attractive for insurers because of the associated costs that are not sufficiently compensated for within the existing scheme. These are often people with (complex) chronic conditions who would benefit the most from more integrated care service arrangements. Therefore, risk selection still seems to be a much more profitable strategy than developing person-centred care arrangements for high-cost patients. Risk adjustment schemes that allow for improved risk sharing arrangements between insurer and regulators or involve overcompensating for certain risk combinations could potentially stimulate insurers investing in more advanced care arrangements for related population groups (Van Barneveld et al., 2001; Reference Van Barneveld, van Vliet and van de VenVan Barneveld, van Vliet & van der Ven, 2001; Reference Van de Ven, van Kleef and van VlietVan de Ven, van Kleef & van Vliet, 2015; Reference Van Kleef, van Vliet and van de VenVan Kleef, van Vliet & van de Ven, 2016).

The question of whether countries should use insurance choice as a means to achieve more person-centred care has no easy answers. Countries would be well advised not to overestimate its impact on person-centredness or ultimately the quality of care. They also should not underestimate the wider implications of insurance choice and competition for health systems. These include the limited negotiation power of multiple insurers vis-à-vis providers (especially when compared to a single payer), increased administrative burden, incentives that may undervalue public health, and a possible further fragmentation of the system, which is likely to undermine rather than promote more person-centred care. There may be more effective ways to improve patient centredness in a given system. One is to better involve consumer and patient groups in the governance, design, operation, learning and purchasing decisions of insurers. Moreover, a range of regulation and accountability mechanisms exist that may be more effective in encouraging the development and adoption of person-centred care models. There is also a need to better understand the degree to which the population understands and values insurance choice, with regular debates in the Netherlands, Slovakia, Switzerland and the USA about the possibility of switching to a single national health insurance fund, a topic that was subject to a referendum in the case of Switzerland in 2014 (Reference De PietroDe Pietro et al., 2015).

That said, countries contemplating the introduction of (more) insurer choice and competition should take the following lessons to heart. First, periodic choice should be structured, simple and individualized and perhaps narrowed to a smaller number of options. Second, there should be regular monitoring and presentation of information on satisfaction with insurance services, on the quality of care provided under health insurance policies, and on the benefits covered and prices. Third, webportals that provide information to support people in making choices should be independent and transparent, an issue that will be especially important in the case of for-profit providers. Fourth, people should be given the opportunity to purchase mandatory insurance separately from additional VHI arrangements, and this should be enforced and monitored closely. Although this is the case in the reviewed countries, people are not always aware of these options. Fifth, there is a need for regularly improving and updating the risk adjustment system to minimize gaming and optimize incentives for insurers for contracting person-centred services. Finally, the use of navigators to assist consumers in making their choice and enrolling with insurers may help people to exercise more informed choices.