Increasing training opportunities in mental health research has been identified as a necessity for the UK to lead research into mental illness. Reference Sahakian, Malloch and Kennard1 However, as a result of the increasingly demanding criteria for funding of academic units in medical schools, the medical academic workforce has been reduced substantially. Reference Garralda2 This reduction has particularly been observed in lecturer posts, with a 40% reduction in the number of psychiatry lecturers in the UK between 2000 and 2006. Reference Margerison and Morley3 Subsequently there were moves to streamline the academic postgraduate training of doctors in line with Modernising Medical Careers and the Walport report outlined the development of integrated academic training pathways. 4 In England and Northern Ireland this resulted in academic clinical fellowship (ACF) posts being created that allowed selected trainees to spend a quarter of their training time over 3 years engaged in research. It was expected that these posts would allow a proportion to be successful in obtaining a research training fellowship (such as those funded by the Wellcome Trust, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and the Medical Research Council) to support research towards the award of a PhD. It was anticipated that approximately two-thirds of trainees would not be awarded this funding for a higher degree and so a smaller number of academic clinical lecturer (ACL) posts were established with half-time clinical activity and half-time postdoctoral research. The situation is somewhat different in Scotland and Wales. In Scotland, reforms to clinical academic training are led by the Scottish Clinical Research Excellence Development Scheme (SCREDS) and there are a range of pre-doctoral academic schemes similar to ACF posts and postdoctoral positions are referred to as SCREDS lectureships instead of ACLs. In Wales, the Welsh Clinical Academic Training (WCAT) scheme provides run-through training for aspiring clinical academics. An early assessment of the ACF scheme identified that although four out of five ACFs intended to apply for a training fellowship, programme leads expressed concern for the careers of those who did not achieve PhD funding and emphasised that ACFs should not become the only route into academic medicine. 5

The ACF and ACL posts came into force in 2007 and by the end of 2009 the Royal College of Psychiatrists expressed concern that ‘the recent changes have been particularly disruptive to career paths in academic psychiatry’. 6 Their report emphasised that academic psychiatry was an area that requires a great deal of flexibility to recruit high-quality trainees and develop them to a high standard of both clinical and academic expertise. It further pointed out that psychiatric trainees typically move into research later than trainees in many other disciplines, which meant that the new system disadvantaged psychiatry. A lack of flexibility in the new integrated academic training system and difficulties matching clinical training in psychiatric specialties with academic training structures have impeded quality of training and led to concerns as to whether we are training enough academic psychiatrists for the future. Reference Garralda2 Trainees have also expressed concerns that changes to the structure of training following Modernising Medical Careers have made it more difficult for trainees to undertake research. Reference Jauhar7

There is a perception that there is insufficient provision of academic training opportunities in psychiatry and this shortage may be particularly acute in specialties outside general adult psychiatry. Reference Garralda2 There is currently little information available about the psychiatric trainees undertaking academic training and the nature of any issues relating to academic training in psychiatry. Therefore, the Executive Committee of the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Faculty of Academic Psychiatry sought to obtain more detailed information about the current position of academic training in psychiatry.

Method

The aim of these surveys was to obtain an overview of the academic posts in university departments of psychiatry and establish the number of psychiatric trainees in academic training in the UK, in order to help find ways to better support academic training in psychiatry. The first survey was sent by email to all heads of department of psychiatry in the UK. This asked questions about the number of trainees and senior academics in the department and whether there were any current vacancies and recently advertised jobs, and also requested a summary of any issues or difficulties surrounding trainees undertaking academic training in psychiatry. The second survey was then distributed by email to ACF and ACL trainees by the NIHR, and to all psychiatric trainees registered with the Royal College of Psychiatrists so that trainees pursuing academic training other than ACF/ACL posts could be included. The email that was sent by NIHR and the Royal College of Psychiatrists contained a link to an online survey that did not contain any identifiers to ensure that trainees’ responses were anonymous. The questions related to current position, any difficulties experienced and their wish to pursue an academic career.

The information about the number of academic trainees obtained from the first survey of heads of departments was used to estimate the total number of academic trainees, which enabled the response rate to the second survey to be estimated. Data were analysed using SPSS version 18 on Windows. The chi-squared test was used to compare binary outcomes and the Mann-Whitney U-test was used to analyse differences between two groups for the ordinal data. The free-text comments provided by respondents were independently assessed by two authors who assigned them to groups based on their content. The resultant groups were then compared and final groups jointly agreed before re-examining the comments to assign them to these groups.

Table 1 Number and position of academic trainees as reported by the heads of departments of psychiatry

| Training post | n | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Academic clinical fellow | 51 | Based at 12 universities; 36 posts in core training and 15 in advanced training |

| Clinical training fellow | 34 | Based at 9 universities |

| University lecturer | 34 | Based at 14 universities |

| Academic clinical lecturer | 13 | Based at 6 universities |

| Other | 33 | Includes teaching fellows, preparatory research fellows and those on other funded projects |

Results

Heads of departments of psychiatry survey

A total of 25 of the 28 university heads of department responded to the survey, a response rate of 89%. The information they provided indicated that the current senior academic workforce in psychiatry in the UK consists of 102 senior lecturers/readers and 121 professors. There were 4 departments with vacancies, with 8 senior posts having been advertised in the past 2 years and 15 senior posts likely to be advertised in the next 2 years. The number of trainees based in their departments is summarised in Table 1. Four universities reported having no academic trainees in psychiatry.

Three themes emerged from the free-text answers about difficulties facing trainees undertaking academic training in psychiatry: balance of clinical and academic training; concerns about obtaining funding; and a lack of infrastructure. In relation to balance and ACF posts, one respondent said:

‘It is difficult for them to find the time during CT1-3 [core trainee years 1-3] to do enough research to get a training fellowship.’

Another emphasised the challenge to clinical work of being an ACF:

‘Although these trainees are without question our best trainees, expecting them to complete a 3-year core programme in 75% of 3 years is a huge task.’

A lack of funding was often cited as a barrier to encouraging trainees into an academic career, with several respondents emphasising that clinical training fellowships are very hard to obtain, particularly outside the larger departments. Comments relating to a lack of the necessary infrastructure included:

‘Lack of critical mass!’

Academic trainees’ survey

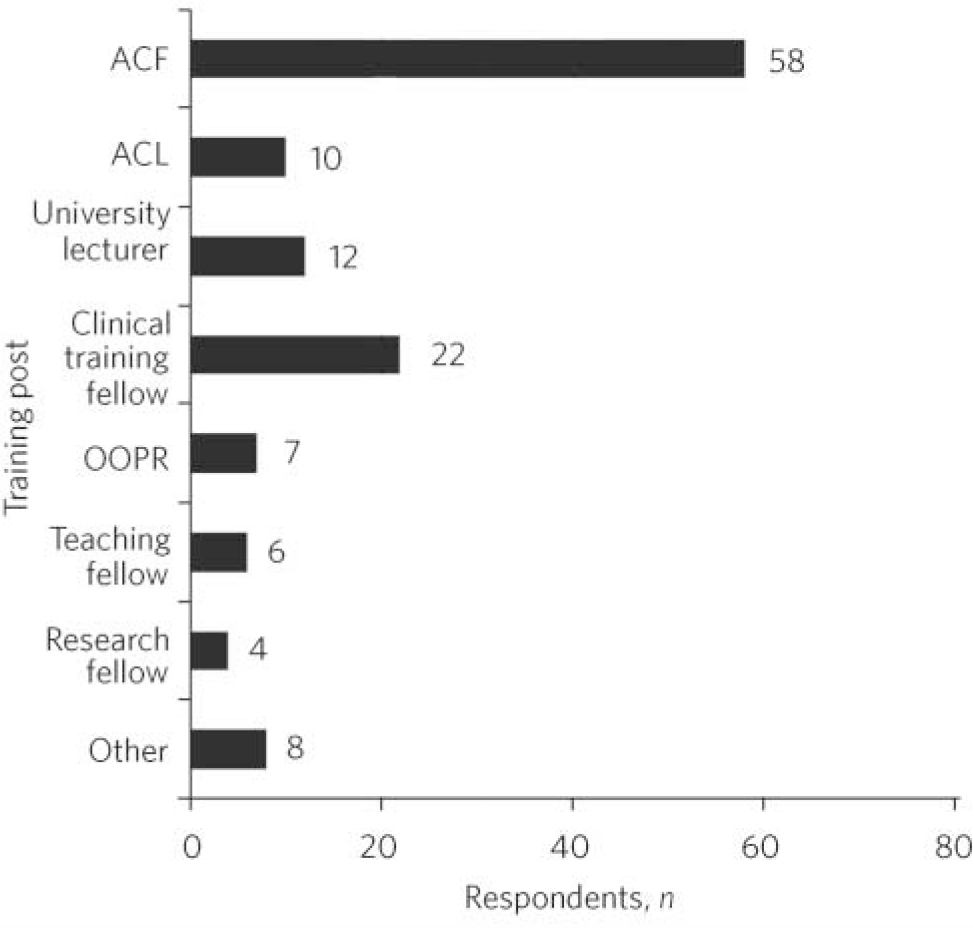

The trainees’ survey received 127 responses and information gathered from the heads of department above gave an estimate of the total number of academic trainees of 165, therefore giving an estimated response rate of 77% for the trainees’ survey. Responses were received from 70 females and 57 males, who were working in a range of academic training positions, as shown in Fig. 1. A total of 82 of the 127 respondents had graduated from a UK medical school. Of the trainees, 7 had a PhD and 5 held an MD, with 41 trainees currently registered for a higher research degree. As shown in Table 2, 68 trainees (60%) considered their specialty to be general adult psychiatry. Of the 107 trainees who gave details of their university affiliation, 83 (78%) were based at just 9 universities, with the largest group (26%) being based at the Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London.

Fig 1 Grades of trainees responding to the survey (n = 127). ACF, academic clinical fellow; ACL, academic clinical lecturer; OOPR, out of programme research.

Respondents were asked to rate their experience of academic training to date as excellent, good, average or poor; only 4.6% of respondents rated their training as excellent, the most frequent response was of an average experience (49/109). All eight ACLs reported their experience as being average or poor. Difficulties with balancing research with clinical training was identified by the majority of respondents (73/110) as a primary difficulty in their academic training and difficulties with this balance were associated with a worse experience of academic training (z = –2.528, P = 0.011). There were no differences between trainees in different types of research post in terms of difficulties experienced or how they rated their experience of their academic training.

Table 2 Number of academic trainees working in each specialtyFootnote a

| Specialty | Academic trainees, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Child and adolescent | 16 (14) |

| Forensic | 6 (5) |

| General adult | 68 (60) |

| Learning disability | 3 (3) |

| Old age | 9 (8) |

| Psychotherapy | 2 (2) |

| Other | 10 (9) |

a. Missing data for 13 respondents.

In total, 60 respondents (55%) stated that they intended to pursue an academic career, although a significant number were also unsure (36/109, 33%). Factors associated with intending to pursue an academic career were:

-

• being in a more senior training position (z = –2.063, P = 0.039)

-

• having a greater number of publications (z = –2.281, P = 0.023)

-

• having a better experience of training (z = –2.636, P = 0.008)

-

• having a greater frequency of supervision (z = –2.683, P = 0.007)

-

• a lack of perceived difficulty in obtaining funding (z = –2.247, P = 0.025).

Having a better experience of training and a greater frequency of supervision remained statistically significant after correcting for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni method.

Overall, 82% of academic trainees were likely to recommend a career in academic psychiatry to a medical student. Reasons why respondents would not recommend an academic career in psychiatry to a medical student included:

‘It appears to be detached from clinical practice.’

‘More personally and financially rewarding to stay in clinical work.’

Trainees most likely to recommend a career in academic psychiatry to medical students were those who rated their own experience of academic training more highly (z = –4.709, P<0.0001) and those who wished to continue pursuing the career themselves (χ2(2) = 20.206, P<0.0001).

There was no significant difference between males and females in terms of difficulties they experienced with their training, how satisfied they were with their training or whether they wanted to pursue an academic career. However, there was a significantly higher proportion of men than women in more senior training roles (z = –2.158, P = 0.03).

The main issues that were raised in the academic trainees’ free-text comments included: the number of academic training posts available, difficulties managing clinical and research time, and the need for greater supervision and support. With regard to lack of suitable academic posts, this was experienced at various levels:

‘Limited opportunities to venture into academic training if not on the ACF/ACL programme.’

‘Difficult to find academic experience in areas which are likely to translate to a robust doctoral training fellowship application.’

Struggles balancing academic and clinical workload were also expressed, along with comments about the practical administration of academic training within clinical training:

‘Better communication between university and NHS.’

‘Assistance in informing Deaneries and Trusts of the importance in assisting trainees to follow academic careers - which appears to be very low on the training priorities.’

‘The process of getting clinical experience approved (if gained during a training fellowship) is bureaucratic and badly organised.’

Another concern included a lack of information and poor supervision; this led to the following improvements being suggested:

‘More structured supervision at the initial stages.’

‘Transparency as to what we are entitled to as ACFs and what is expected of us in return.’

‘Information about how to go about applying for funding opportunities and grant applications.’

Discussion

Challenges

Trainees and heads of departments of psychiatry responding to these surveys identified very similar challenges for academic training in psychiatry. Both trainees and senior academics highlighted the difficulty balancing clinical and research time and obtaining funding as key issues. A previous survey of junior doctors (in all specialties and both academic and clinical posts) suggests that obtaining funding has been a longstanding concern and also highlighted conflicts between academic and clinical work and concerns about a shortage of more senior academic posts. Reference Goldacre, Stear, Richards and Sidebottom8 Concerns regarding obtaining funding are mirrored in an early survey of all trainees appointed to the ACF scheme, which found that although 63% intended to eventually work in clinical academic posts, the factor most likely to dissuade them was difficulty obtaining research grants. Reference Goldacre, Lambert, Goldacre and Hoang9 A lack of infrastructure and the number of academic training posts available were also important issues for both trainees and their heads of department in these surveys. The majority of academic trainees were in just nine universities, creating particular challenges for trainees outside of these institutions trying to enter academic training.

Women are underrepresented in senior academic positions in psychiatry and various reasons for this have been proposed. Reference Howard10-Reference Killaspy, Johnson, Livingston, Hassiotis and Robertson12 Although this fact has again been highlighted in this study, it is somewhat encouraging that women did not differ in terms of any aspect of their experience of academic training. However, it may be that despite an apparent willingness and determination to pursue and promote academic psychiatry, women still struggle to reach more senior academic positions.

Academic provision in specialties within psychiatry other than general adult psychiatry has long been considered a particular challenge Reference Lindesay, Katona, Prettyman and Warner13 and this study has demonstrated that 60% of academic trainees are working within general adult psychiatry, with particularly small numbers in forensic psychiatry and intellectual disability (referred to as people with learning disability in the UK health services). As already highlighted, this could be as a result of the new training structure because ACFs may have limited exposure to specialties other than general adult psychiatry until after entering higher training. This may also lead to some trainees in other psychiatric specialties having a later entry into research (post-MRCPsych), with the resultant difficulty of trying to complete a higher research degree before achieving their Certificate of Completion of Training (CCT).

Workforce planning

The number of trainees identified in these surveys as being in academic training (165) is higher than might be expected. However, it is unclear how many academic trainees are needed to replenish the current senior academic workforce of approximately 220. This will be affected by retention of trainees through the academic career pathway to senior positions, which relies on trainees having the necessary support to progress with their career and them being of sufficiently high quality to compete successfully for training fellowships and grants. It is also relevant that very few trainees considered their academic training to be excellent and that all ACLs reported an average or poor experience. These matters raise concerns about how we can support trainees towards more senior positions.

Support and supervision

Indeed, the need for greater supervision and support was particularly identified by trainees. It is important that more frequent supervision was associated with wishing to pursue an academic career. Although it may be that more frequent supervision increases enthusiasm for pursuing an academic career, other possible explanations include that more motivated trainees seek out more supervision or that supervisors offer more time to those they believe are particularly capable of academic success. However, a significant number of difficulties experienced by academic trainees, including obtaining funding and managing the competing pressures of academic and clinical work, could potentially be resolved through more frequent and better quality supervision. This study therefore highlights the importance of having a strong supervision system in place during academic training. Particular consideration needs to be given to the support network for trainees outside the ACF/ACL structures, especially those in smaller institutions, with a focus both on mentoring and peer support.

Limitations

The primary limitation of this study is that it only provides a cross-sectional picture of the current situation. In the future it would be useful to utilise a longitudinal approach to follow the career outcomes of academic trainees, providing richer information about relevant issues and potential influencing factors. Also there are relevant comparator groups who have not been included in the current work, for example it may be beneficial to survey psychiatric trainees who are not in academic posts or make comparisons with academic trainees in other specialties of medicine.

It was also not possible in these surveys to address the issue of the quality of trainees being attracted into academic psychiatry. We are not able to determine how much of the difficulty highlighted in ACFs obtaining very competitive training fellowships is as a result of mentorship and training and how much is as a result of the nature of the individuals pursuing a career in academic psychiatry compared with those in other medical specialties.

Implications

The difficulties highlighted in these surveys point to a key message for improving academic training in psychiatry in the future: increasing flexibility. It has been highlighted that the integrated academic training pathway of ACF and ACL positions may not be ideally suited to the needs of psychiatry. The requirement to have submitted a PhD thesis prior to applying for an ACL post is a significant problem, particularly in psychiatry when clinical research necessitates a later entry into research and the time before the end of clinical training may be limited. The Tooke Report on Modernising Medical Careers recommended that in addition to ACF posts, opportunities should also be available for those wishing to pursue a research career after entry into higher training. Reference Tooke14

These surveys showed that there are a significant proportion of trainees who are not within the integrated academic training pathway of ACF and ACL positions. This may suggest that trainees are indeed taking a more flexible approach and attempting to create a training pathway that meets their needs or utilises what is available to them. In order to support trainees in achieving this flexibility it is necessary for there to be improved communication between universities and deaneries, supported by the Royal College of Psychiatrists. Ensuring that academic support to obtain research training fellowships is coordinated with timely support from deaneries for out-of-programme research periods is key. Innovative solutions and streams of funding should be sought for trainees who take alternative routes to academia, for example commencing a PhD late in training or having already obtained a PhD prior to training in psychiatry. In addition to attracting the brightest and the best into the specialty, maximising opportunities to pursue research and an academic career post-membership and enhancing flexibility in academic training will be crucial components of securing the future of academic psychiatry.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the National Institute for Health Research and the Royal College of Psychiatrists for distributing the trainees’ survey. We thank Professor Nick Craddock for his support of the project and all the trainees and heads of university departments of psychiatry who responded to the surveys. Professor Peter Woodruff kindly provided helpful comments on an earlier draft of this paper.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.