Introduction

Do voters retrospectively punish politicians responsible for bad institutions? Considering a plethora of evidence that incumbents serve at the mercy of factors partially or wholly out of their control – “from the state of the market to the weather, the performance of sports teams, and shark attacks (Achen and Bartels Reference Achen and Bartels2013 [but cf. Fowler and Hall Reference Fowler and Hall2018]; Healy et al. Reference Healy, Malhotra and Mo2010; Gasper and Reeves Reference Gasper and Reeves2011; Miller Reference Miller2013)” – it stands to reason that they should also be evaluated on the actual performance of the governments they run, and the institutions whose quality they are tasked with upholding.

Nevertheless, existing research has thus far only provided limited answers to this critical question. Apart from the literature on economic voting, which indirectly deals with institutional performance (Kramer Reference Kramer1983; see Healy and Malhotra Reference Healy and Malhotra2013 for a review), the most approximate body of evidence comes from an emerging literature showing that political corruption scandals moderately and contingently diminish politicians’ electoral prospects (Welch and Hibbing, Reference Welch and Hibbing1997; Fackler and Lin, Reference Fackler and Lin1995; Ferraz and Finan, Reference Ferraz and Finan2008; Chang et al., Reference Chang, Golden and Hill2010; Costas-Pérez et al., Reference Costas-Pérez, Solé-Ollé and Sorribas-Navarro2012; Bägenholm, Reference Bågenholm2013; De Vries and Solaz, Reference De Vries and Solaz2017; Klašnja, Reference Klašnja2017). Political corruption is, however, only one of several salient dimensions of institutional quality, a list that not only includes other types of corruption but also issues like bureaucratic ineffectiveness, partial exercise of power, and lack of transparency (Adserá et al., Reference Adserà, Boix and Payne2003; Langbein and Knack, Reference Langbein and Knack2010; Agnafors, Reference Agnafors2013; Rothstein and Varraich, Reference Rothstein and Varraich2017). To this end, I follow a smaller body of work that implicitly or explicitly (Boyne et al., Reference Boyne, James, John and Petrovsky2009; Burlacu, Reference Burlacu2014) studies voters’ reaction to institutional quality in the aggregate, a complementary but important concept for investigations into electoral accountability.

To test the salience of such institutional performance voting, I employ unique and hard data of formal critique launched through performance audit reports in Swedish municipalities between 2003 and 2014 as a proxy for institutional dysfunction. From the perspective of institutional quality, Sweden is a high-performing setting (Transparency International, 2017; World Bank Group, 2018), a stark contrast to the bulk of single country studies in the field of corruption voting (e.g., Ferraz and Finan Reference Ferraz and Finan2008; Chang et al. Reference Chang, Golden and Hill2010; Costas-Pérez et al. Reference Costas-Pérez, Solé-Ollé and Sorribas-Navarro2012; Chong et al. Reference Chong, De La O, Karlan and Wantchekon2015; Klašnja Reference Klašnja2015).

The results point to a presence of institutional performance voting, both among voters and politicians. Audit critique is associated with a statistically significant but substantively moderate electoral loss of about a percentage point for mayoral parties. It is simultaneously associated with a 14 percent decrease in incumbent probability of reelection. Almost half of this decreased reelection probability (6 percent) remains even after voting is accounted for. This latter finding in part reflects the competitive nature of Swedish municipal politics, where a small vote differential may have substantive real-world effects, and in part the fact that maintaining power in a multiparty system involves convincing both voters and junior coalition partners – who in contrast do not noticeably lose votes from critique – that the top parties should be given the confidence to continue governing.

Institutional quality and electoral punishment for poor performance

A simultaneously precise and universally accepted definition of institutional quality does not exist, and given its conceptual breadth, is unlikely to ever calcify. Indicative of the concept’s scope, it tends to go under many names, commonly through combining ‘good’ or ‘quality’ with ‘institutions,’ ‘governance,’ or ‘government.’ A set of lowest common denominators does, however, exist within the literature, as both abstract (Agnafors, Reference Agnafors2013; Rothstein and Teorell, Reference Rothstein and Teorell2008) and more concrete (Adserà et al., Reference Adserà, Boix and Payne2003) definitions claim a certain set of properties to be foundational for the institutions of a polity to be considered “good,” principally, an absence of corruption, the effective realisation of policies, impartial conduct toward citizens, protection of property rights, as well as a measure of transparency. As an empirical illustrative, one may consider the oft-cited World Bank’s governance Indicators (2018), which apart from corruption control also include five other dimensions of governance: Voice and accountability, regulatory quality, political stability and absence of violence, rule of law, and government effectiveness.

A growing literature attests to the importance of good institutions for many facets of human welfare; politicians and public servants operating in a competent, honest, and effective manner within a political and administrative framework that supports these virtues has proven essential, not only for ascertaining that public goods are appropriately delivered to the citizenry (Helliwell and Huang, Reference Helliwell and Huang2008; Holmberg and Nasiritousi, Reference Holmberg, Rothstein and Nasiritousi2009; Ott, Reference Ott2010) but also through bolstering the type of macroeconomic indicators that often form the focus of the economic voting literature (Chong and Calderon, Reference Chong and Calderon2000; Acemoglu et al., Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2001; Rodrik et al., Reference Rodrik, Subramanian and Trebbi2004; Sobel, Reference Sobel2008; Nistotskaya et al., Reference Nistotskaya, Charron and Lapuente2014).

Considering its considerable real-world importance, voters in a democracy should accordingly be highly incentivized to sanction low institutional quality and reward it when it is high. In light of this assumption, there is a relative dearth of evidence in the relevant literature on retrospective voting for the assumption that democratically elected politicians and parties who fail to ascertain good institutions are punished at the polls. This light footprint can partially be explained by difficulties in isolating both institutional quality and politicans’ performance from the greater political, economic, and social context. Two interrelated subfields have, however, advanced our state of knowledge about the matter, respectively, focusing on the economy and corruption.

Economic voting

The most common strand of retrospective voting models employs indicators to capture incumbent performance by leveraging the state of the economy (Fiorina, Reference Fiorina1981; Powell and Whitten, Reference Powell and Whitten1993; Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier, Reference Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier2000; Healy and Malhotra, Reference Healy and Malhotra2013; Healy et al., Reference Healy, Persson and Snowberg2017). Indeed, any government seeking reelection is incentivized to direct considerable efforts toward the economy; in the words of Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier (Reference Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier2000, 183), “good times keep parties in office, bad times cast them out.”

Although unquestionably a salient factor to voters’ decision-making process, these strictly economy-centered models generally stop short of capturing a large part of what actual performance of politicians entails, including the administrative framework over which they preside and the public goods they are in charge of providing. Albeit an important aspect, governing well involves much more than keeping stock markets high, inflation low, and people at work. Furthermore, although the state of the economy is central to any government’s job description, incumbent politicians generally only wield partial influence over macroeconomic performance and individuals’ economic welfare (see Kramer Reference Kramer1983, Dynes and Holbein Reference Dynes and Holbein2020), a circumstance accentuated by increasing globalisation (Hellwig and Samuels, Reference Hellwig and Samuels2007). Although these realizations are at least indirectly considered in recent works on political budget cycles (Alesina and Paradisi, Reference Alesina and Paradisi2017; Prichard, Reference Prichard2018; Repetto, Reference Repetto2018), this macroeconomic bias in the retrospective voting literature can at least in part, as Maravall and Sànchez-Cuenca (Reference Maravall and Sànchez-Cuenca2008, 5; see also Clark Reference Clark2009) argue, be explained “mainly because economic performance is an easy variable to assess.”

Corruption voting

A more recent strand of research on retrospective voting that more closely engages with institutional quality focuses on the specific issue of political corruption scandals. This literature has found modest negative effects from accusations of, and evidence for, incumbents’ corruption on their subsequent electoral success, with such punishment often found contingent on factors like media coverage (Fackler and Lin, Reference Fackler and Lin1995; Welch and Hibbing, Reference Welch and Hibbing1997; Ferraz and Finan, Reference Ferraz and Finan2008; Chang et al., Reference Chang, Golden and Hill2010; Costas-Pérez et al., Reference Costas-Pérez, Solé-Ollé and Sorribas-Navarro2012; Klašnja, Reference Klašnja2017), economic conditions (Klašnja and Tucker, Reference Klašnja and Tucker2013), and ideologically proximate alternatives (Charron and Bågenholm, Reference Charron and Bågenholm2016). This scandal-focused literature has undoubtedly advanced the state of knowledge of how actual institutional dysfunction is – and is not – translated into vote loss.

Indeed, political corruption is morally reprehensible, (usually) illegal, and should reasonably be a salient factor for voters when deciding whether to vote for actors engaging in such activities. Nevertheless, while political corruption scandals in undoubtedly antithetical to institutional quality, it is – as noted above – only one of several aspects of the concept (Agnafors, Reference Agnafors2013; Rothstein and Varraich, Reference Rothstein and Varraich2017).

Crucially, the specific issue of political corruption scandals is not seldom of lesser direct relevance to individual voters compared to many other cases of institutional dysfunction, like when an entire government apparatus fails to provide citizens with public services or does so in a discriminatory and partial manner. In addition, by its tendency to focus on politicians, often at high levels of government, the corruption voting literature is arguably more centred around grand- than small-scale corruption (Schwindt-Bayer and Tavits Reference Schwindt-Bayer and Tavits2016; De Vries and Solaz Reference De Vries and Solaz2017, 5). From a voter-welfare perspective, this approach risks incurring a problematic elite bias, considering that voters are at least as likely to suffer from petty types of corruption generally associated with bureaucratic and administrative misconduct at lower levels of government (Rose-Ackerman and Palifka, Reference Rose-Ackerman and Palifka2016, 11). Suggestive of the potential gains in looking beyond grand corruption, Winters and Weitz-Shapiro (Reference Winters and Weitz-Shapiro2016) provide evidence pointing towards the electoral importance of bureaucratic corruption, finding that voters’ punishment of mayors is only marginally smaller when corruption involves subordinate bureaucrats than the mayors themselves.

Moreover, although political corruption wields a negative impact on the welfare of the electorate in general, for example, when politicians embezzle public funds for private gain, real-life instances of corruption are frequently more complex. For instance, these can involve actions that, albeit legally and morally illicit, under certain conditions may even be “welfare enhancing” and bring the electorate benefits, at least over the short-term (see Fernández-Vázquez et al. Reference Fernàndez-Vàzquez, Barberà and Rivero2016; Ferrer Reference Ferrer2020), thereby creating unclear or even negative incentives for electoral punishment.

Rather, a more universal electoral function of political corruption scandals is most likely in terms of a signal of other undesirable traits of politicians’ moral character and their devotion and ability to perform on matters that in turn are of greater relevance to voters’ own well-being. Of course, complicating this signalling function is the clandestine nature of corruption, which inherently makes voters’ ability to acquire information of such instances difficult (De Vries and Solaz, Reference De Vries and Solaz2017). Further, even when available, it is not obvious that such a signal will be found credible by its recipients (see Weitz-Shapiro and Winters Reference Weitz-Shapiro and Winters2016).

To summarise, although both economic conditions and corruption scandals are plausible factors to consider for understanding performance-based retrospective voting, each perspective is limited in its own way: The former focuses on factors at least in part outside of politicians’ scope of influence and often only indirectly relate to government performance in itself. The latter is conceptualized more narrowly than the now considerable literature on institutional quality would prescribe as important to citizens and voters. As neither of these literatures claim, or even aim, to identify every relevant way in which incumbent performance can or should be measured, they leave plenty of room in accounting for its full breadth, and also capture other things in the process. Just as dire economic straits do not automatically make incumbents ‘rascals’ (Stokes, Reference Stokes1963, 373), simply abstaining from corruption (or, at least, not getting caught) are insufficient grounds to conclude that they are not worthy of being thrown out.

Institutional performance voting

Considering these difficulties in discerning variation in incumbent performance, employing variation in institutional quality in the aggregate is arguably a highly valuable contribution to a retrospective voting literature that thus far has shown little interest in the concept. This is perhaps best illustrated by Ferraz and Finan’s (Reference Ferraz and Finan2008, 710) seminal work on corruption and local incumbents’ electoral performance in Brazil, which leaves available indicators on poor administration outside their analysis. A few notable exceptions do, however, exist: Studies focusing on public service provision (Boyne et al., Reference Boyne, James, John and Petrovsky2009) and valence (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Sanders, Stewart and Whiteley2009) indirectly employ the framework of institutional quality to explain voter behaviour. Most notably, Burlacu (Reference Burlacu2014) makes the institutional quality concept explicit, finding that improvements on this factor are significantly associated with increased incumbent support, although only in countries with lower levels of economic development.

Undoubtedly, this notion of institutional performance voting closely relates to corruption voting – after all, the the latter concept is an important part of the former. There are, however, a number of advantages to studying the full range of institutional quality dimensions for which incumbents are responsible, complementing the narrower focus on political corruption:

First, self-interested voters will plausibly have greater incentives to vote against failures of institutional performance than they do to punish scandal-ridden politicians. As noted in the previous section, while scandals serve as a salient but indirect signal of problems with the availability and quality of public goods provision, institutional quality affects these matters directly and in a more consistently negative direction, not only by petty bureaucratic corruption, but low effectiveness and lack of fairness in public service delivery (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Sanders, Stewart and Whiteley2009), the presence of unnecessary red tape, or even pure “government blunders” (Jennings et al., Reference Jennings, Lodge and Ryan2018), etc.

Furthermore, as also argued by Burlacu (Reference Burlacu2014), considering the noted difficulties of information acquisition in relation to political corruption (De Vries and Solaz, Reference De Vries and Solaz2017), which is generally heavily dependent upon media scrutiny, many dimensions of institutional quality are felt and thereby observable to voters through a larger number of channels, including media coverage but also personal experiences with the type of issues listed in the previous paragraph that citizens encounter in their daily lives.

Finally, while incumbents may attempt to hide or otherwise “spin” problems with institutional quality, they are less likely able to keep such systemic issues secret from voters compared to many instances of political corruption. Consider, for example, an act of bribery, which may entail no more than two actors, both of whom incentivized to keep quiet about the transaction.

In conclusion, institutional quality, considered in the aggregate, provides a mostly untapped but plausibly salient source for evaluating incumbents’ performance. The concept relates not only to corruption scandals but also directly concerns citizens’ experience with the public sector and the way in which they receive public goods. Framed in the parlance of the classical voting behaviour literature, while both political corruption and the broader notion of institutional quality squarely fit within conventional definitions of a valence issue (Stokes Reference Stokes1963; Fiorina Reference Fiorina1981; Clark Reference Clark2009; Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, Sanders, Stewart and Whiteley2009; Green and Jennings Reference Green and Jennings2017, 306), institutional quality occupies a considerably larger share of this space. In fact, building on Clark’s (Reference Clark2009) deconstruction of valence issues into policy- and non-policy-related dimensions, it is reasonable to argue that, like the economy can be considered the principal factor in the policy dimension of valence, institutional quality merits a corresponding position in the non-policy category. Building on Stokes Reference Stokes1963 foundational framework, Clark (Reference Clark2009, 111) highlights as non-policy valence dimensions “honesty, trustworthiness, unity,” and “competence.” With the exception of political unity, these characteristics fit well into any mainstream conceptualization of institutional quality.

The remainder of the article will leverage audit reports in Swedish municipalities in order to test the underlying notion of institutional performance voting that incumbent electoral performance is contingent upon their governments’ level of institutional quality.

Audit reports as indicators of institutional dysfunction

Empirical measurement of institutional quality is universally considered challenging, considering the concept’s breadth and often clandestine symptoms. In lieu of hard or comprehensive measures, comparative studies have extensively relied on expert assessments of partial components, such as perceived level of corruption, bureaucratic quality, and protection of property rights (Heritage Foundation, 2017; PRS Group, 2017; Transparency International, 2017; World Bank Group, 2018). Furthermore, critique regarding the whole-nation bias of such indicators emphasises the need to complement cross-country studies with subnational analysis (Charron et al., Reference Charron, Lapuente and Rothstein2013; Snyder, Reference Snyder2001), as well as to consider temporal dynamics (Bäck and Hadenius, Reference Bäck and Hadenius2008).

In order to meet these demands, my strategy for proxying institutional quality, Swedish municipal performance audit reports, employs simultaneously hard and holistic data, which both vary sub-nationally and over time; it is a strategy similar to that used by Ferraz and Finan (Reference Ferraz and Finan2008, 704), Boyne et al. (Reference Boyne, James, John and Petrovsky2009), and Chong et al. (Reference Chong, De La O, Karlan and Wantchekon2015). Arguably, the very purpose of such reports is to evaluate factors that closely approximate most conventional definitions of institutional quality, as outlined above. As Pollitt and co-authors (Reference Pollitt, Girre, Lonsdale, Mul, Summa and Waerness1999, i) note, the performance audit is devised as a crucial supervisor of a polity’s institutional performance, offering “a means by which the citizens of democratic states may be offered independent reassurance as to the economy, efficiency, effectiveness, and good management of the programmes pursued by their governments,” and recent evidence (Avis et al., Reference Avis, Ferraz and Finan2018) indicates that audits hold this potential under real-life conditions.

The match between the general goals of performance auditing and institutional quality is reflected in the case at hand: In Sweden, the performance of municipal governmentsFootnote 1 is annualy scrutinized by municipal audit committees. Deriving from chapter nine in the Swedish Local Government Act (Svensk Författningssamling, 1991, 900), and accompanying guidelines stipulated in the steering document Code of Audit Practice in Local Government, issued by the Swedish Association of Local Assemblies and Regions (2014), the audit committee in each municipality is tasked with evaluating whether the municipal executive board (roughly equivalent to the municipal executive branch, appointed by the directly elected municipal assembly) or the various committees serving below it has failed on one or several of eight distinct grounds:

-

(1) inadequate goal achievement, failure to observe the objectives and guidelines set by the assembly or in regulation;

-

(2) deficient management, follow-up, and control;

-

(3) damage to the public trust or other intangible injury;

-

(4) financial injury;

-

(5) unauthorised decisionmaking;

-

(6) operations not conforming to law, criminal conduct;

-

(7) insufficient preparation of decisions;

-

(8) deficient accounting.

Such failures result either in a formal remark (less severe) or in a dissuasion for the municipal assembly to grant discharge for the members of the criticised body (more severe). While it is not within the auditors’ purview to explicitly recommend voters to vote for or against an incumbent, there are few clearer signals of low institutional performance than when the agent whose law-mandated task it is to oversee government affairs gives that government a failing grade.

As indicators of institutional dysfunction, the audit reports – which are released the following year – make for relatively hard measures. Based on initiated experts’ (the auditors, who are nominated and chosen by the parties in the municipal assembly, and their assistant experts) assessments, the reports capture specific instances of institutional dysfunction, rather than general perceptions upon which mainstream measures tend to rely. Section A of the supplementary material, which describes the steps taken to construct the Swedish Municipal Audit Report database that covers audit remarks in Sweden’s 290 municipalities between 2002 and 2015, reports tests of the external validity of audit critique as a measure of institutional quality, as suggested herein. The results, showing that audit critique robustly correlates to three independent measures of institutional quality, are strongly supportive of this notion.

Mirroring the diversity inherent to the concept of institutional quality, this list contains a wide range of deficiencies relating to its principal subcomponents, including corruption, which is directly highlighted in (6) and indirectly through (4), (5), and (8), but also correspond well with other aspects: Low effectiveness is captured by (1), (2), and (7) and failures in transparent governance by (2) and (8). The conception of institutional quality that squares least obviously with the listed aspects is likely Rothstein and Teorell’s (Reference Rothstein and Teorell2008) notion of impartiality, although this is to a large degree a consequence of the concept’s relatively encompassing and abstract nature. At least indirectly, aspects (1), (5), (6), and (7) would all be telltale signs of partial exercise of power. This list clearly does not merely capture nebulous theoretical concepts, but many aspects of what a voter would likely consider to be bad institutions, for example, due to (2) deficient control mechanisms, (6) government agents engage in unlawful activities, wherein (4) public money disappears, and then (8) the agents cover up their transgressions.

Although it is conceivable that some instances of critique capture minor mistakes and formalities, a clear majority concerns real-world problems. Perhaps unsurprisingly considering its broad formulation, point (2) relating to management and control is by far the most common grounds for critique (included in 85 % of cases where critique is launched of instances in the sample period; the runner-up (1) relating to goal achievement is included in 28 % of cases). The canonical example of such issues involves uncontrolled budget overruns, either for day-to-day operations like social services or ambitious one-time construction projects like stadiums or water parks. Although instances of outright bribery and corruption are rarely placed point-and-centre, one example is when an executive board received a remark for failing to correct a bookkeeping system that allowed a municipal employee to embezzle several million Swedish kronor. A more common issue involving legal matters is the failure to comply with public procurement laws and assuring open competition.

Further emphasising its salience, once critique is launched, it is near-ubiquitously reported in the local press (as further demonstrated in Section B of the supplementary material). A selection of local newspaper headlines illustrates the language by which voters are likely to catch word of the issue: Auditor on politician’s mistake: “Hard to fathom” (Gothenburg 2015 [Pettersson Reference Pettersson2016]), Harsh critique against committee chair (Arvidsjaur 2012 [Sundkvist Reference Sundkvist2013]), Municipal executive board receives hearty berating (Båstad 2010 [Pettersson Reference Pettersson2010]), and, simply put, Audit critique: A remark is really serious (Lund 2013 [Ziegerer Reference Ziegerer2014]).

There are three potential threats to the credibility of audit critique as a valid indicator of institutional quality: The first derives from politicization and the fact that although audit committee chairs are normally nominated by the political opposition, there is a nontrivial minority of coalition-chaired audits. However, as demonstrated and discussed in greater detail in Section A of the supplementary material, there are neither signs of a lower propensity for majority-chaired audits to wield critique in the first place (but rather the opposite) nor does the opposition-/coalition-chair cleavage affect the focal relationship between critique and incumbents’ electoral performance. Further supported by previous works (Lundin, Reference Lundin2010) that point to near-universal unity among audit committee members across the ideological spectrum when deciding to launch critique, politicization does not therefore appear to pose a substantial problem for measurement. Second, like the bulk of previous studies about corruption and institutional quality drawing from audit data – as well as those focusing on corruption scandals – for capturing the institutional quality dimension in retrospective voting, the measure contains negativity bias; municipal auditors do not give out gold stars for high effectiveness or excellence in management. Interestingly, one exception to this rule, Boyne et al. (Reference Boyne, James, John and Petrovsky2009) who do have a more fine-grained audit measure at their disposal, nevertheless find evidence of a negativity bias in electoral response to audit scores. Noting this limitation, my results follow this line of research. Finally, aspect (3) in the list above, “damage to the public trust or other intangible injury” is potentially a problematic indicator for the present purpose of investigating the link between institutional quality and electoral performance, as it presumes loss of citizens’ confidence, thus risking endogenizing vote loss. However, this ground for critique is always accompanied by at least one other reason in the data used, eliminating the risk that this factor alone is the reason for audit critique.

Independent variable

The principal treatment used for the empirical analysis, Audit critique, is a binary variable indicating whether the audit committee of a Swedish municipality has launched formal critique during a given term period. The audit data are available for three full term periods: 2003–06, 2007–10, and 2011–14. This results in 870 full municipal term periods. Since the position of mayor was found to have shifted between parties mid-term 39 times during this time frame, the resulting sample consists of 909 observations.Footnote 2 As the critique measure includes election-year critique, which is not formally released until after a given election is held, the potential influence of this factor is discussed in detail below, as well as in Section B in the supplementary material.

Critique occurred in 9 % of municipal-years during the 2003–2014 period (321 instances), resulting in 27 % of municipal term periods having critique being launched in one or several years (244 instances). This propensity has increased somewhat during the period under study, with the annual probability increasing from 6 % for the 2003–06 term to around 10 % in the 2007–10 and 2011–14 terms.Footnote 3 As Figure 1 shows, there is no discernible bias in terms of which party is on the receiving end, in terms of being the mayoral party.

Figure 1. Probability of audit critique is orthogonal to who rules. Note. Reported frequencies of municipal-term periods of rule, by mayoral party. S = Social Democrats; M = Moderates; C = Centre Party; CD = Christian Democrats; L = Liberals; Other=Other, local, party; LP = Left Party; GP = Green Party. No mayoral party has a significantly distinguishable probability of audit critique from any other party or the sample mean. Municipal term-periods with the Left Party (6 instances of rule) and Green Party (1 instance) as mayoral party received no audit critique during the sample period. Results from logistic regression with standard errors clustered by municipality. Capped lines display 95 % confidence intervals.

Empirical strategy

To estimate the relationship between institutional dysfunction and incumbents’ electoral performance, I depart from a change model, and the equation

where

i

indicates municipality and

t

term period. The primary dependent variable,

![]() $\Delta $

Mayoral party vote share, is calculated as the percentage-point difference in vote share between term period

t

and

$\Delta $

Mayoral party vote share, is calculated as the percentage-point difference in vote share between term period

t

and

![]() $_{t + 1}$

for the party that holds the position of mayor in

t

.Footnote

4

Information on the party of mayors was initially provided by a SALAR staff member and crosschecked with information on mayors collected by Dr. David Karlsson, as well as local media reports and Swedish official statistical yearbooks.Footnote

5

$_{t + 1}$

for the party that holds the position of mayor in

t

.Footnote

4

Information on the party of mayors was initially provided by a SALAR staff member and crosschecked with information on mayors collected by Dr. David Karlsson, as well as local media reports and Swedish official statistical yearbooks.Footnote

5

To further zoom in on the municipal component of electoral support, the analysis also considers

![]() $\Delta $

Municipal-parliament vote share differential for mayoral party as a secondary measure. Calculated by subtracting municipal-level vote share at the concurrent parliamentary elections from vote share in the municipal-level contest (see Andersen et al. Reference Andersen, Fiva and Natvik2014 for a similar approach), this variable thereby only considers how much better (worse) a mayoral party fares in the election for municipal assembly compared to the same party’s performance in the same municipality for the parliamentary election taking place at the same time. The principal benefit of this approach is that it removes the influence of potential omitted variables concerning general fluctuations in party support that would be otherwise difficult to measure. On the other hand, as the variable lends parliamentary performance baseline status, operationalising the variable for measuring municipal-level support broadly means assuming zero spill-over effects from the municipal- to the parliamentary arena of politics. Although it is uncontroversial to consider parliamentary elections in Sweden as being of the first-order and municipal elections of the second, this is likely an overly strong assumption. Consider, for example, a scandal involving a sitting mayor. In this case, the municipal-parliamentary differential only captures punishment by supporters who decide to vote for another party in the next municipal election but still remain faithful to the party at the national level. Punishment by supporters so disillusioned with the party by the scandal that they abandon it altogether are not captured. Despite this likely underestimation of changes in support at a more general (and, arguably, substantively meaningful) level, the differential-measure is reported alongside the raw measure in order to present the fullest possible picture.

$\Delta $

Municipal-parliament vote share differential for mayoral party as a secondary measure. Calculated by subtracting municipal-level vote share at the concurrent parliamentary elections from vote share in the municipal-level contest (see Andersen et al. Reference Andersen, Fiva and Natvik2014 for a similar approach), this variable thereby only considers how much better (worse) a mayoral party fares in the election for municipal assembly compared to the same party’s performance in the same municipality for the parliamentary election taking place at the same time. The principal benefit of this approach is that it removes the influence of potential omitted variables concerning general fluctuations in party support that would be otherwise difficult to measure. On the other hand, as the variable lends parliamentary performance baseline status, operationalising the variable for measuring municipal-level support broadly means assuming zero spill-over effects from the municipal- to the parliamentary arena of politics. Although it is uncontroversial to consider parliamentary elections in Sweden as being of the first-order and municipal elections of the second, this is likely an overly strong assumption. Consider, for example, a scandal involving a sitting mayor. In this case, the municipal-parliamentary differential only captures punishment by supporters who decide to vote for another party in the next municipal election but still remain faithful to the party at the national level. Punishment by supporters so disillusioned with the party by the scandal that they abandon it altogether are not captured. Despite this likely underestimation of changes in support at a more general (and, arguably, substantively meaningful) level, the differential-measure is reported alongside the raw measure in order to present the fullest possible picture.

![]() ${\beta _1}$

represents the main coefficient of interest, whether audit critique has been launched during term t.

${\beta _1}$

represents the main coefficient of interest, whether audit critique has been launched during term t.

![]() $\lambda $

is a vector of variables accounting for other economic, political, and structural factors that may influence incumbents’ electoral performance and institutional quality. Since I estimate voters’ response to institutional dysfunction, it is especially necessary to account for broader economic factors, considering the observed importance of these for both vote choices and institutional quality.Footnote

6

In lieu of a suitable variable that corresponds to the conventional GDP per capita measure on a municipal level (Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier, Reference Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier2000, 188–189), the model considers the “are-you-better-off-than-four-years-ago?”-factor by including the average annual difference in mean income between the final years of term periods

$\lambda $

is a vector of variables accounting for other economic, political, and structural factors that may influence incumbents’ electoral performance and institutional quality. Since I estimate voters’ response to institutional dysfunction, it is especially necessary to account for broader economic factors, considering the observed importance of these for both vote choices and institutional quality.Footnote

6

In lieu of a suitable variable that corresponds to the conventional GDP per capita measure on a municipal level (Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier, Reference Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier2000, 188–189), the model considers the “are-you-better-off-than-four-years-ago?”-factor by including the average annual difference in mean income between the final years of term periods

![]() ${t - 1}$

and t to account for general fluctuations in the private economy of voters. Incumbents are also at least partially responsible for Unemployment rates, which I include as average annual change in open unemployment for the 20- to 64-year-old population (see Barreiro Reference Barreiro2008, 30; Helgason and Mérola Reference Helgason and Mérola2017). Two economic factors more directly relating to government undertakings (Kramer, Reference Kramer1983) are included: Change in municipal tax rate (see Mörk and Nordin Reference Mörk and Nordin2020; Brautigam et al. Reference Brautigam, Fjeldstad and Moore2008) and municipalities’ Fiscal result. The latter is operationalised through total municipal fiscal results (1000 SEK per capita during period t, and is also included in squared form. Here, the logic could go two ways: on the one hand, municipal governments may spend aggressively to provide generous public goods as a short-term strategy to secure reelection; on the other hand, such a strategy may lead voters fearing deficits to opt for new and more fiscally responsible leadership.

${t - 1}$

and t to account for general fluctuations in the private economy of voters. Incumbents are also at least partially responsible for Unemployment rates, which I include as average annual change in open unemployment for the 20- to 64-year-old population (see Barreiro Reference Barreiro2008, 30; Helgason and Mérola Reference Helgason and Mérola2017). Two economic factors more directly relating to government undertakings (Kramer, Reference Kramer1983) are included: Change in municipal tax rate (see Mörk and Nordin Reference Mörk and Nordin2020; Brautigam et al. Reference Brautigam, Fjeldstad and Moore2008) and municipalities’ Fiscal result. The latter is operationalised through total municipal fiscal results (1000 SEK per capita during period t, and is also included in squared form. Here, the logic could go two ways: on the one hand, municipal governments may spend aggressively to provide generous public goods as a short-term strategy to secure reelection; on the other hand, such a strategy may lead voters fearing deficits to opt for new and more fiscally responsible leadership.

![]() $\omega $

represents a set of dummy variables indicating Identity of the mayoral party. Although there are no strong theoretical expectations as to why a certain party would affect the quality of municipal government (a notion bolstered by the absence of systematic inter-party differences in the probability of critique demonstrated in Figure 1) pick up unmeasured socioeconomic and demographic variation, which in turn may affect both institutions and vote choice. Finally, to account for country-wide electoral trends and shocks, I include term period-fixed effects,

$\omega $

represents a set of dummy variables indicating Identity of the mayoral party. Although there are no strong theoretical expectations as to why a certain party would affect the quality of municipal government (a notion bolstered by the absence of systematic inter-party differences in the probability of critique demonstrated in Figure 1) pick up unmeasured socioeconomic and demographic variation, which in turn may affect both institutions and vote choice. Finally, to account for country-wide electoral trends and shocks, I include term period-fixed effects,

![]() $\gamma $

. Standard errors,

$\gamma $

. Standard errors,

![]() $\varepsilon $

, are clustered by municipality. Tables in Section C of the supplementary material display the descriptive statistics for all included variables.

$\varepsilon $

, are clustered by municipality. Tables in Section C of the supplementary material display the descriptive statistics for all included variables.

To ascertain that any results are independent upon the particular modelling strategy taken, I also apply a FE-model, which predicts within-unit variation in the dependent variable by including

![]() $\theta $

, municipal fixed effects, in an otherwise identical model as (1):

$\theta $

, municipal fixed effects, in an otherwise identical model as (1):

Next, being a PR system, the link between electoral performance and retaining power in Swedish electoral politics is non-trivial. The fact that 87 % of the sample’s governments are coalitions, attests to post-election bargaining around coalition formation being a ubiquitous factor. The role of institutional quality for this dynamic is not a priori obvious. On one hand, existing and potential coalition partners may be less willing to let a party responsible for previous institutional dysfunction retain the top position of mayor, regardless of how it fared at the polls. On the other hand, empirical analysis on European governments implicated in corruption scandals (Bågenholm, Reference Bågenholm2013) shows no significant evidence for actual change in government, despite an observed electoral cost. This finding implicitly hints at the possibility that parties responsible for low institutional quality make up for such weaknesses by strong negotiating skills or a proclivity for choosing coalition partners less sensitive to these matters.

To capture this all important aspects of political competition, I therefore also estimate the probability of mayoral party re-election as a function of audit critique by logistic regression. The model,

mirrors equation (1) by including the same set of covariates and clustering standard errors by municipality. Parallell to the fixed effects approach of equation (2), I additionally employ conditional, fixed effects, logistic regression, by which reelection probabilities for incumbents that have received critique are compared with probabilities for uncriticized counterparts within the same municipality.Footnote 7

Finally, I explicitly investigate the different steps of the post-election bargain by introducing Mayoral party vote share

![]() $_{t + 1}$

– the outcome of interest in the first step – as an additional covariate to equation (3). By controlling for this factor, I seek to explicitly parse out the extent to which institutional dysfunction affects incumbents’ reelection prospects through the vote shares they receive and through post-election bargaining. Since this this approach clearly relies on introducing a variable measure post-treatment, as well as the assumption of sequential ignorability by which unmeasured confounding variables affecting the critique-vote share, the critique-reelection, or the vote share-reelection links are absent – both of which are problematic assertions (Montgomery et al., Reference Montgomery, Nyhan and Torres2018) – I complement this approach with mediation sensitivity analyses, as developed by Imai et al. (Reference Imai, Keele and Tingley2010, Reference Imai, Keele, Tingley and Yamamoto2011).

$_{t + 1}$

– the outcome of interest in the first step – as an additional covariate to equation (3). By controlling for this factor, I seek to explicitly parse out the extent to which institutional dysfunction affects incumbents’ reelection prospects through the vote shares they receive and through post-election bargaining. Since this this approach clearly relies on introducing a variable measure post-treatment, as well as the assumption of sequential ignorability by which unmeasured confounding variables affecting the critique-vote share, the critique-reelection, or the vote share-reelection links are absent – both of which are problematic assertions (Montgomery et al., Reference Montgomery, Nyhan and Torres2018) – I complement this approach with mediation sensitivity analyses, as developed by Imai et al. (Reference Imai, Keele and Tingley2010, Reference Imai, Keele, Tingley and Yamamoto2011).

Audit critique and Incumbents’ electoral performance

The empirical models described above are devised to provide the answer to two interrelated questions: First, is low institutional quality, as captured by audit critique, linked to incumbent vote loss in Swedish municipalities? Second, is the same phenomenon related to a diminished probability of incumbent reelection? In brief, the answer to both questions is in the affirmative; in the former instance by a little, and in the latter by a substantial amount.

Beginning with estimating incumbents’ electoral support as a function of critique, Table 1 presents the bivariate and fully controlled models with mayoral party vote shares, followed by a fully controlled model predicting the municipal-parliamentary vote differential, using both change- (columns 1-3) and FE-models (4-6).

Table 1. Mayoral party vote share and audit critique

Note. In columns 1, 2, 4, and 5, vote share is calculated in terms of mayoral party’s share of valid votes in the election for municipal assembly. In columns 3 and 6, vote share is calculated in terms of percentage-point difference between elections in municipal assembly and parliament for a given municipality. Standard errors, clustered by municipality, in parentheses. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

Column 1, which displays the bivariate coefficient regressing

![]() $\Delta $

Mayoral party vote share on audit critique, shows the latter associated with vote loss to the magnitude of just above a percentage point (

$\Delta $

Mayoral party vote share on audit critique, shows the latter associated with vote loss to the magnitude of just above a percentage point (

![]() $\beta $

-1.14; p < 0.01). Adding the covariates of column 2, using the preferred specification in equation (1), results in a coefficient just below one percentage point (

$\beta $

-1.14; p < 0.01). Adding the covariates of column 2, using the preferred specification in equation (1), results in a coefficient just below one percentage point (

![]() $\beta $

= –0.87; p < 0.05). When the municipal-parliamentary differential is estimated in column 3, the size of the relationship is reduced by half and significance disappears (

$\beta $

= –0.87; p < 0.05). When the municipal-parliamentary differential is estimated in column 3, the size of the relationship is reduced by half and significance disappears (

![]() $\beta $

= –0.42; p = 0.24). The FE-model consistently garners considerably larger coefficients for the corresponding models,

$\beta $

= –0.42; p = 0.24). The FE-model consistently garners considerably larger coefficients for the corresponding models,

![]() $\beta $

= –2.60 in the bivariate model (column 4) and

$\beta $

= –2.60 in the bivariate model (column 4) and

![]() $\beta $

= –1.38 in the fully controlled model (column 5). Although dropping below the percentage point (

$\beta $

= –1.38 in the fully controlled model (column 5). Although dropping below the percentage point (

![]() $\beta $

= –0.95), critique remains significant at the p < 0.05-level also when predicting the municipal-parliamentary differential (column 6).

$\beta $

= –0.95), critique remains significant at the p < 0.05-level also when predicting the municipal-parliamentary differential (column 6).

Judging from these results, audit critique does not mean the end for an incumbent party; the roughly percentage-point penalty amounts to around a seventh of a standard deviation in the dependent variable for the change model and an eighth of a within-unit standard deviation in the FE-model. Indeed, critique is unlikely to amount to a landslide defeat.

On the other hand, putting vote loss related to audit critique in comparison with another potentially relevant predictors like tax increases, critique is tantamount to an increase of between two-thirds and three-quarters of a percentage point, a relatively rare event, occurring between 60 and 80 times during the sample period.

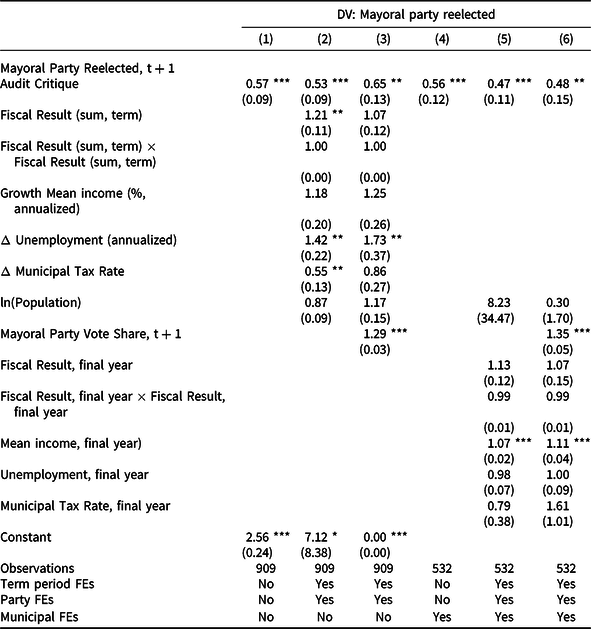

Further, in the relatively competitive Swedish municipal political landscape, over a fifth of governments in the sample reside within a percentage point of a majority. As such, for the clearest indication of the electoral relevance of institutional dysfunction and audit critique, we must turn to the analysis of mayoral party reelection. Table 2 reveals that, regardless of choice of model (pooled logit results are reported in columns 1–3, corresponding results for the conditional fixed effects model in columns 4–6), audit critique is highly significantly (p < 0.01) associated with lower reelection probabilities, estimated bivariately (columns 1 and 4) and with covariates included (2 and 5). Furthermore, the critique-coefficient remains significant (p < 0.05) also when incumbent vote share – that is, voters’ punishment – in

![]() $_{t + 1}$

is accounted for (columns 3 and 6).

$_{t + 1}$

is accounted for (columns 3 and 6).

Table 2. Mayoral party reelection and audit critique

Note. Columns 1–3: OLS. Columns 4–6: FE regression. Coefficients indicate odds ratios. Standard errors, clustered by municipality, in parentheses. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

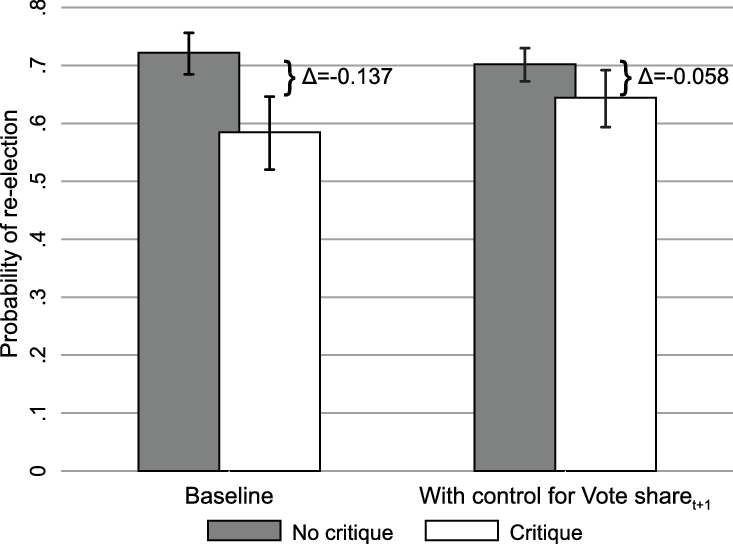

To translate these results into substantive interpretation, Figure 2 displays the predicted re-election probabilities by audit critique derived from the estimations in columns 2 and 3, the former without and the latter with voters’ judgement considered. The left side reveals a relatively dramatic 14-point drop in reelection probability, from 72 to 58 %. Even with the vote share measure included, a statistically significant gap of nearly 6 percentage points remains. This indicates that critique incurs additional behind-the-scenes damage during post-election inter-party negotiations. Mediation analysis (Tingley et al. (Reference Tingley, Yamamoto, Hirose, Keele and Imai2014)) confirms this view, showing that just over half (55 %) of the total effect of audit critique is mediated through vote share

![]() $t + 1$

, and that both the average direct effect (ADE) and average causal mediated effect (ACME) are robust to violations of the assumption of sequential ignorability (see Section D1 in the supplementary material for more details).

$t + 1$

, and that both the average direct effect (ADE) and average causal mediated effect (ACME) are robust to violations of the assumption of sequential ignorability (see Section D1 in the supplementary material for more details).

Figure 2. The probability of mayoral party reelection diminishes with audit critique, even after the votes are in Results from logistic regression with standard errors clustered by municipality. Capped lines display 95 % confidence intervals.

Sensitivity analyses, the results of which are reported in Section D in the supplementary material, confirm that the observed relationship for audit critique and vote loss is highly stable to a number of different alterations to the preferred choices of modelling and estimation technique, as described above. First, I took the route of related works like Boyne et al. (Reference Boyne, James, John and Petrovsky2009) and Burlacu (Reference Burlacu2014) by including lagged vote share for mayoral parties into the original set of calculations reported in Equations (1) and (2). This change generally increases size and significance of the critique coefficient, also rendering it significant at the p < 0.1 level (

![]() $\beta $

=-0.65) when predicting the municipal-parliamentary differential using the change model (results in Table D2 in the supplemental material). Second, I excluded influential cases, calculated in terms of Cook’s Distance-scores. The result is again a uniformly significant critique-coefficient, at the p < 0.05 level or higher (Table D3). Third, employing the approach favoured by Karlsson and Gilljam Reference Karlsson and Gilljam2016), I exchanged the original dependent variable for a measure calculated as mayoral party vote share in

$\beta $

=-0.65) when predicting the municipal-parliamentary differential using the change model (results in Table D2 in the supplemental material). Second, I excluded influential cases, calculated in terms of Cook’s Distance-scores. The result is again a uniformly significant critique-coefficient, at the p < 0.05 level or higher (Table D3). Third, employing the approach favoured by Karlsson and Gilljam Reference Karlsson and Gilljam2016), I exchanged the original dependent variable for a measure calculated as mayoral party vote share in

![]() $_{t + 1}$

as a proportion of its vote share in t, with results similar to the original specification (Table D4). Fourth, I reran the original estimations but ignored intra-term power shifts by including only one observation (the final mayoral party) per municipal term period. The results are near identical to the original results (Table D5). Fifth, in an alternative way of capturing national-level trends and shocks, I exchanged term dummies for a covariate explicitly measuring the national-level (parliamentary) results for the mayoral parties (calculated as between-term change in the change model and as levels in the FE-model). Again, the procedure leaves the critique coefficient equal or stronger than originally reported (Table D6). Sixth, in light of Healy and Lenz’s (Reference Healy and Lenz2014) finding that voters tend to respond disproportionately to election-year economies, I make a series of adjustments in the temporality of the battery of covariates. Recall that, while the covariates used in the original FE-model are already measured for election years (or the most recent alternative), the change model compares developments over the entire term period t. Following the emerging theme, replacing the original covariates with corresponding measures focusing on the election year, expressed both in terms of levels and annual changes, leaves the critique- coefficient untouched or marginally strengthened (Table D7). In sum, the general impression from these sensitivity tests is that the conclusions drawn from the original model are highly stable to deviations from the preferred strategies.

$_{t + 1}$

as a proportion of its vote share in t, with results similar to the original specification (Table D4). Fourth, I reran the original estimations but ignored intra-term power shifts by including only one observation (the final mayoral party) per municipal term period. The results are near identical to the original results (Table D5). Fifth, in an alternative way of capturing national-level trends and shocks, I exchanged term dummies for a covariate explicitly measuring the national-level (parliamentary) results for the mayoral parties (calculated as between-term change in the change model and as levels in the FE-model). Again, the procedure leaves the critique coefficient equal or stronger than originally reported (Table D6). Sixth, in light of Healy and Lenz’s (Reference Healy and Lenz2014) finding that voters tend to respond disproportionately to election-year economies, I make a series of adjustments in the temporality of the battery of covariates. Recall that, while the covariates used in the original FE-model are already measured for election years (or the most recent alternative), the change model compares developments over the entire term period t. Following the emerging theme, replacing the original covariates with corresponding measures focusing on the election year, expressed both in terms of levels and annual changes, leaves the critique- coefficient untouched or marginally strengthened (Table D7). In sum, the general impression from these sensitivity tests is that the conclusions drawn from the original model are highly stable to deviations from the preferred strategies.

Next, I explore the robustness of the main results to more substantive alterations in the empirical sample used. Specifically, in order to check whether any single term is driving the results, or any discernible trends are present, I introduced to the original models interaction terms between the critique coefficient and each of the three term period dummies. Although coefficient sizes (and significance levels) vary between terms and models, the critique coefficient is negative in every term using both the change and FE-models, indicating a consistently negative relationship (figure D5).

Finally, to further press the notion that the observed dynamic of audit critique and electoral punishment really is connected to the greater concept of institutional quality and not some other idiosyncratic and unmeasured aspects of audit critique, I exchanged the critique measure for three alternate indices of institutional quality (see Section A in the supplementary material): (a) a survey item about the Quality of application of laws and rules, derived from an annual survey of local businesspeople by the Confederation of Swedish Enterprise (2017),Footnote 8 (b) a Quality of Government-index (Dahlström and Sundell, Reference Dahlström and Sundell2013; Karlsson and Gilljam, Reference Karlsson and Gilljam2014) capturing municipal politicians’ perceptions of the extent of bribery, partiality, and meritocratic recruitment in their respective govenments, and (c) a composite index of top municipal politicians’ and bureaucrats’ perceptions of Corruption in seven administrative spheres drawn from a 2011 survey by the Swedish Agency for Public Management (2012). The first measure is available on an annual basis for the entire sample period, allowing for the same panel framework as used in the main analysis. Since the latter two variables are only measured in 2012 and 2011, respectively, analysis with these variables is restricted to a cross-sectional framework. While the coefficients for both Application of Laws & Regulations (Table D8) and the QoG-index (Table D9) surpass the original critique-coefficient in both strength and consistency of significance, corresponding results for the corruption index fail to reach significance in any model (Table D10). While the single-shot measurement of the latter two relationships provide weak fodder for broader substantive conclusions, and the QoG-index also contains items relating to corruption, the results of the alternative specifications are collectively at least indicative that, in a high-performing, low-corrupt context like Sweden, other aspects of institutional quality than corruption seem to occupy voters’ minds.

Extensions

Having presented robust evidence that incumbents pay an electoral price for faltering institutional quality, we can further nuance this picture by, in turn, widening the object of analysis to include a broader notion of incumbency, applying the empirical analysis to more specified measurement of critique, and, finally, investigate the important steps of information dissemination and acquisition. As for the robustness checks, the full results underpinning these analyses are available in Section E in the supplementary material, and summarised below.

Coalition rule and clarity of responsibility

Switching focus from mayoral parties to governments at large and, in the common case of coalition rule, their supporting members, I ran regressions otherwise identical to the main analyses reported in Table 1 to estimate the audit critique-electoral performance-link for these entities. This garners considerably weaker results compared to those for mayoral parties: Although the critique-coefficient is negative and significant (p

![]() $ \lt $

0.1) for whole-government vote share in the bivariate version of the change model as well as the FE-model predicting the municipal-parliamentary vote differential, the relationship is null, if consistently negative in direction in the other specifications (Table E1 in the supplementary material). Considering the original finding that criticized mayoral parties do lose votes, this is potentially welcome news for supporting parties in criticized coalitions; indeed, critique coefficients for supporting parties’ vote share are consistently positive, although equally consistently insignificant (Table E2). Taken together, these results indicate that, while Swedish municipal voters do attribute blame for dysfunctional institutions, the burden is for the top to bear more or less alone.

$ \lt $

0.1) for whole-government vote share in the bivariate version of the change model as well as the FE-model predicting the municipal-parliamentary vote differential, the relationship is null, if consistently negative in direction in the other specifications (Table E1 in the supplementary material). Considering the original finding that criticized mayoral parties do lose votes, this is potentially welcome news for supporting parties in criticized coalitions; indeed, critique coefficients for supporting parties’ vote share are consistently positive, although equally consistently insignificant (Table E2). Taken together, these results indicate that, while Swedish municipal voters do attribute blame for dysfunctional institutions, the burden is for the top to bear more or less alone.

By extension, these modest results raise additional questions about clarity of responsibility (CoR), a concept both the twin literatures on economic and corruption voting regularly employ to identify institutional and political factors that condition responsibility attribution (Powell et al., Reference Powell and Whitten1993; Tavits, Reference Tavits2007; Hobolt et al., Reference Hobolt, Tilley and Banducci2013; Schwindt-Bayer and Tavits, Reference Schwindt-Bayer and Tavits2016). Performance voting, this view holds, is only likely when voters can be certain of whom to blame or thank. While the single-country setting naturally keeps institutional aspects of CoR constant, I borrow from Hobolt et al. (Reference Hobolt, Tilley and Banducci2013) and introduce an index of government CoR as an interaction term to investigate how it conditions punishment for mayoral parties, whole-of-governments, and supporting parties, respectively.Footnote

9

For whole-governments, CoR’s role in conditioning audit critique is insignificant and inconsistent in direction depending on specification (Table E3). At face value, this may be taken as a sign that CoR does not play a role in the present context. However, similar analyses estimating mayoral and supporting parties paint a more complex picture: For mayoral parties, higher CoR is closer to ameliorating than worsening the electoral ramifications of critique (the interaction term is significant (p

![]() $ \lt $

0.1) once controls are included but not for the municipal-parliamentary differential; Table E4). On the other hand, for supporting parties, the same interaction is negative, if only significant in the change model for the municipal-parliamentary differential (Table E5).

$ \lt $

0.1) once controls are included but not for the municipal-parliamentary differential; Table E4). On the other hand, for supporting parties, the same interaction is negative, if only significant in the change model for the municipal-parliamentary differential (Table E5).

A comprehensive analysis of this seemingly puzzling trend falls outside of the scope of this study. However, when considered in combination with the observation above, one plausible if tentative interpretation from these findings stands out: In limited-information political environments of the second order, like the local governments studies herein, where only mayoral parties are electorally vulnerable to critique on a general level, the electoral dominance implied by high scores on the government CoR index may also bring an opportunity for such top-level actors to effectively deflect blame to other targets, justly or not.

Disaggregated critique

In an effort to provide a more detailed view of the ways in which different dimensions of critique relate to electoral performance, as described above, I disaggregate the original audit critique measure by severity (dissuasion of discharge versus remark; figure E1), target (executive board versus lower-level committees; figure E2), and the eight potential grounds for critique (figure E3), exchanging the original variable with these disaggregated measures and rerunning the original regressions. I also calculated critique by number of unique points of critique launched in a given term (figure E4). However, instead of providing a more meaningful picture of the critique-electoral performance dynamics, the overarching message from analyzing these specific dimensions separately is one of increased instability of results, while no individual dimension outperforms the general measure. On a theoretical level, the lack of additional understanding provided lends credence to the notion of voters reacting to institutional quality in the aggregate argued herein. From the perspective of empirical measurement, it is reminiscent of Langbein and Knack’s (Reference Langbein and Knack2010) finding that also the perhaps most commonly used indicators of institutional quality, the aforementioned World Bank’s governance indicators, best can be understood as capturing a single underlying concept, rather than the specific sub-indicators they purportedly measure.

Timing and acquisition of information

Finally, in their respective reviews of retrospective economic and corruption voting, both Healy and Malhotra (Reference Healy and Malhotra2013) and De Vries and Solaz (Reference De Vries and Solaz2017) emphasise the importance of voters actually acquiring relevant information in order to be able to exert accountability. Indeed, if voters are unaware of the actual audit critique on election day, but this factor is still related to vote loss, the information is likely to have spread in other ways.

To this end, analysis, which is further presented and discussed in Section B in the supplemental material, leverages an inherent temporal lag involved in the production and dissemination of audit reports. Specifically, since the report for year y must be published and presented to the municipal assembly before July 1st in year y+1, we can compare audit critique in reports released before and after elections. The results indicate that critique in years when the actual audit report is not yet launched by election day are just as salient to voters’ observed propensity to punish criticized mayoral parties as for other years. This finding lends further tentative support to the notion that critique, rather than primarily functioning as a direct signal to voters, reflects institutional dysfunction already perceived by the electorate, for example through personal experiences and social networks – especially in smaller settings (a finding that receives some support from further analysis in Section B in the supplementary material) – or continuous local media coverage of the issues that eventually lead to formal critique (a finding that receives mixed support). Supportive of such an interpretation, a survey carried out by the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (2012) finds that auditors in most municipalities continuously report the results of their findings during the year to the municipal assembly. Indeed, norms of best practice stipulate that auditors flag and explain the grounds for critique as soon as possible (Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions, 2014, 7.3.2), and a search in the Swedish Media Archive for news stories that in one way or another relate to the issues subsequently lifted in critical audit reports for election-years reveals that this is usually reported before the election (see Section B in the supplementary material). Thus, any signal of low institutional quality signalled through audits is likely to be dispersed in a piecemeal fashion well before the official report is publicly available.

Conclusion

This study has contributed to the state of knowledge on how two central concepts in modern political science, institutional quality and electoral accountability, interrelate. I departed by laying out the case for institutional performance voting, a concept that complements the economic focus still largely dominating the literature on retrospective voting, while arguably being more theoretically grounded and of higher and more consistent salience for voters than the comparatively narrow focus on political corruption scandals that has hitherto been the leading indicator when linking institutional quality to electoral accountability.

To test the relevance of institutional performance voting, I used municipal performance audit reports to capture institutional dysfunction in Swedish municipalities, a high-performing setting where dynamics of especially corruption voting have hitherto been largely unexplored. The results reveal that accountability mechanisms appear to work as desired on a general level: Audit critique is associated with vote loss of around a percentage point for mayoral parties, rivaling or surpassing the usual economic suspects. Furthermore, it is even more substantially related to diminished reelection prospect for the parties, which decreases by around 14 percentage points. Notably, parts of these deteriorated reelection prospects remain even after accounting for election results, indicating that critique also has negative impact on incumbents’ bargaining position vis-a-vis potential coalition partners.

Although categorisation of Sweden as a more or less fertile ground for institutional performance voting is limited by a large amount of conflicting arguments about whether voters will be more prone to punish low institutional quality and corruption in high-performing (De Sousa and Moriconi, Reference De Sousa and Moriconi2013; Klašnja and Tucker, Reference Klašnja and Tucker2013; Chong et al., Reference Chong, De La O, Karlan and Wantchekon2015) or low-performing (Ecker et al., Reference Ecker, Glinitzer and Meyer2016; Burlacu, Reference Burlacu2014) contexts,Footnote 10 the results herein effectively provide a contrasting case to a slew of previous research on corruption voting in mid- and low-performing contexts. Insofar, they bolster the notion of a universal, if often modest, electoral punishment for low institutional performance. On the other hand, the local context to which the analysis speaks rather follows a long line of research on corruption voting focusing on subnational levels of governance (e.g., Boyne et al. Reference Boyne, James, John and Petrovsky2009; Chong et al. Reference Chong, De La O, Karlan and Wantchekon2015; Costas-Pérez et al. Reference Costas-Pérez, Solé-Ollé and Sorribas-Navarro2012; Ferraz and Finan Reference Ferraz and Finan2008; Klaňnja Reference Klašnja2015), a curious but stark contrast to the literature on economic voting, which until recently has offered comparatively more scant evidence from local- and multilevel context (see Anderson Reference Anderson2006; de Benedictis-Kessner and Warshaw Reference de Benedictis-Kessner and Warshaw2020).

It should also be noted that these findings also demonstrate the limitations of electoral democracy, adherent to a long line of existing research on retrospective voting, not least studies dealing with corruption. Electoral punishment does not extend further down the political hierarchy than to the party that holds the position of mayor, as supporting coalition parties are closer to gaining than losing votes under such circumstances, despite the fact that they plausibly should carry at least partial responsibility.

In sum, the findings presented above both support and challenge the existing state of knowledge on retrospective voting. On one hand, they offer further evidence that voters are at least somewhat sensitive to low institutional performance. On the other hand, they further demonstrate the value of using other sources of information about performance than macroeconomic indicators or corruption scandals.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Andreas Bågenholm, Carl Dahlström, Mikael Gilljam, David Karlsson, Ann-Kristin Kölln, Mikael Persson, Jonathan Polk, Maria Solevid, and members of the Quality of Government Institute for support and helpful comments in the process of working on this study.

Conflict of Interest/Disclosures

The author declares none.

Competing interests

The author declares none.

Funding information

This study is part of the research project “Out of Control or Over Controlled? Incentives, Audits and New Public Management,” funded by Riksbankens jubileumsfond (SGO14–1147:1).

Data Availability Statement

Replication materials are available in the Journal of Public Policy Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/UINA0X (Broms, Reference Broms2021)

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X21000076.