I Introduction and overview

The rise of online platforms, such as Airbnb, has increased the number of residential properties switched to part-time use as peer-to-peer short-term rentals (“short-term lets”) in the UK and Ireland. There are both problems and benefits associated with this. Here I analyse one of the problems, and the legal instrument chosen to regulate the activity in London: the “90-nights” rule of the town planning system.

Peer-to-peer short-term letting is a disruptive innovation in so far as it does not fit with established forms of regulation. In the traditional hospitality sector, business models are very different, and in the case of residential leases these are, by law in the UK and Ireland, regulated by statute. Peer-to-peer short-term letting matches neither model. It is not possible to grant a secure or assured tenancy over a room, or a property, for a period of only a few days. It is also not appropriate to apply the forms of regulation found in the hospitality sector to such lettings, as these are designed for properties which are let continuously on a long-term basis.Footnote 1 The conclusion in this paper is that the spill-overs which materialise in the case of short-term letting are not unfamiliar to the legal systems in the UK and Ireland. These problems arise regularly between neighbouring residential properties which are not short-term lets. Covenants and nuisance claims, with court enforcement, are aptly used to regulate them. Where legislators intervene, by enacting a statute with general and not specific application, inefficient outcomes can result.

The problem I focus on here is spill-over effects which diminish the residential amenityFootnote 2 (“amenity effects”) of properties (“neighbouring properties”) in the neighbourhood of the property which is the subject of the short-term let (the “let property”). The 90-nights rule effectively states that in London a public grant of prior approval – “planning permission” – will be required whenever a property is let for any longer period in a calendar year. I undertake a comparative economic analysis between this rule and alternative private law systems which could internalise the externality: the use of covenants and nuisance. Because an injunction generally follows from a successful claim in nuisance, injunctions are therefore considered too.Footnote 3 My analysis is limited to social efficiency: the minimisation of the sum of the amenity costs, prevention costs and administration + transaction costs (as per Ellickson, 1973).Footnote 4

Whilst Ellickson believed that the transaction costs associated with private bargainingFootnote 5 were high, I argue in this paper that in the specific case of short-term lets they are likely to be low. This is primarily because amenity effects are likely most often to arise in cases where covenants can be used at low transaction cost. To explain this further: it is argued that these effects are more likely to arise in cases where the let property is a part of a multi-unit apartment block, or a building scheme. This conclusion is based, below, on a review of the publicly reported planning decisions which have been issued in the UK and Ireland. These sources show that the amenity effects generally arise as a result of shared facilities between the let property and neighbouring properties, which include: shared entrances, communal corridors and shared walls. It is argued that in “older neighbourhoods”Footnote 6 where residential properties are independent of each other, amenity effects are less likely to arise. Whereas in the case of older neighbourhoods, bargaining between neighbours over covenants to restrict short-term letting involves high transaction costs (Ellickson 1973), in the case of multi-unit apartment blocks and development schemes these transaction costs are likely to be much lower. The reason is that these developments are designed and constructed by a single entity which then drafts and executes head-leases over the individual units. The developer is incentivised to include, in those head-leases, covenants restricting short-term letting,Footnote 7 as this raises the value of all properties within the development. Insertion of these covenants is as simple as copying and pasting a standard form clause into the head-leases, and does not involve costly bargaining between neighbours. In the case of older neighbourhoods, transaction costs are likely to remain high. It is argued here, however, that where amenity effects materialise, claims in nuisance are capable of bringing about internalisation, subject to some reforms to the doctrine.

A subsidiary conclusion is that the problem of nonconvexitiesFootnote 8 is the major justification for the use of prior approval through the 90-nights rule. Nonconvexities arise due to the propensity for local optima to materialise which are inferior to a global optimum in land use patterns.Footnote 9 Put simply, if left to the private market then several small clusters of a given use of land (such as short-term letting) may arise throughout a city. By contrast, in a global optimum in which all of these clusters are located in one area of the city, the amenity effects are minimised. The local optima arise because private parties are unable to see the “bigger picture” when bargaining. Town planners, devising a development plan for the city, will plan for a global optimum which will maximise aggregate land values.

I proceed in Part II by outlining the economic justifications provided for town planning, and by describing the analysis of Ellickson. In Part III I provide some background detail on the English town planning system and briefly explain the public and private interest analyses of this. In Part IV, I examine the amenity effects using legal sources from the UK and Ireland. In Part V I analyse the 90-nights rule by comparison to the private law systems. In Part VI I conclude.

II Economic justifications for town planning and the analysis of Ellickson

Town planning is the categorisation of similar land uses into “classes” and the segregation of those within an urban environment. Segregation obviates the problem of negative externalities, which in this case are the amenity effects. A Coasean approachFootnote 10 would suggest that, in the absence of transaction costs, the owner of the let property would be able to bargain with the owner of the neighbouring property, and that they would reach a solution in which the socially optimal levelFootnote 11 of the activity would take place.Footnote 12 In the presence of transaction costs, which is the case here, that outcome is likely to be suboptimal. It follows that the law should grant original entitlements to land use which seek to minimise the cost of bargaining between neighbours. The town planning system achieves this through segregation of uses. This avoids the need for costly bargaining, or internalisation of the amenity effects through taxes.Footnote 13 Town planning, however, does not fully allow for Coasean bargaining because planning permission cannot be granted by neighbours, only by the local planning authority.Footnote 14 As such, the town planning approach of segregation can be seen as an alternative to the Coasean approach.Footnote 15

Whilst segregation may be an effective response to amenity effects, it will not work in every case. David Mills has analysed the problemFootnote 16 by drawing a distinction between persistent amenity effects,Footnote 17 which extend beyond neighbouring properties, and non-persistent effects which do not.Footnote 18 An example of the former is air pollution caused by industrial use, which can be expected to affect a whole city and the wider area. An example of the latter is the disturbance to neighbours emanating from a short-term let. It is amenity effects of this latter type which I am concerned with in this paper.

Perfect segregation of classes is not possible, and the nature of uses found is often mixed both within buildings and between them.Footnote 19 That is the case with short-term lets, which cannot be zoned for exclusively and which involve mixed use as residential and commercial property. The insight that segregation “works” is also not based upon any comparative analysis between different systems of regulation. Indeed, legal intervention might not be warranted at all. Several have argued that in a laissez faire distribution, the market would bring forth a pattern more socially efficient than random.Footnote 20 Alternatively, Ellickson argues (elsewhere) that social normsFootnote 21 will lead to the internalisation of amenity effects without the need for law.

The most interesting comparisons, however, are to be drawn between the use of town planning and private law systems. In his 1973 paper, “Alternatives to Zoning: Covenants, Nuisance Rules, and Fines as Land Use Controls”,Footnote 22 Ellickson considered the regulation of land use generally. He undertook a comparative analysis between the social efficiency of the use of town planningFootnote 23 and private law bargaining in the form of, first, contractual covenants agreed between neighbours, and second, the alteration of properties rights through the legal doctrine of nuisance.Footnote 24

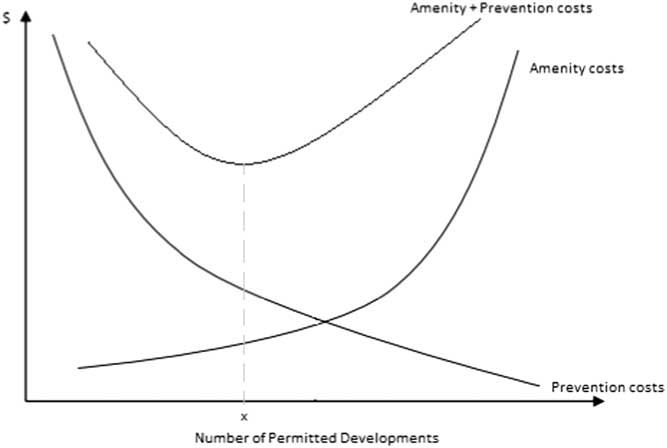

For this, Ellickson began by considering two costs:Footnote 25 (1) amenity costsFootnote 26 – those associated with the amenity effects upon neighbouring properties; and (2) prevention costs – the cost incurred by the owner of the let property in mitigating the amenity effects. Where the choice is a binary one (either permission for the development of a short-term let is granted or not) then the relevant prevention cost is the opportunity cost to the individual proposing to rent their property out on a short-term let, of not doing so. As the number of permitted developments increases, the prevention costs fall and the amenity costs rise. In principle, any system used should seek to set the number of permitted developments at the point which minimises the sum of these two costs, at point x as illustrated above in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Minimisation of sum of amenity and prevention costs

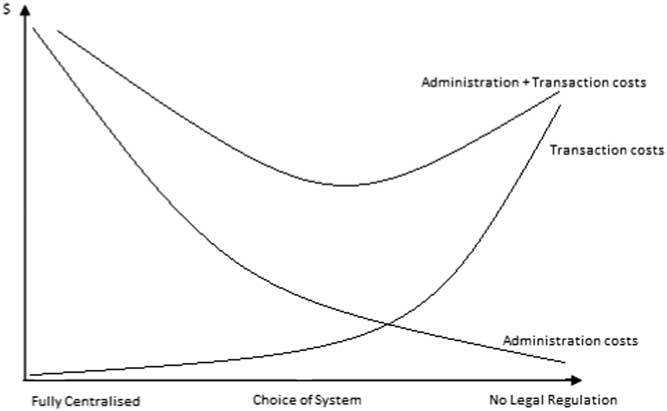

To this analysis, Ellickson added administration costs – the direct costs of running the system, and policing and enforcing the rules – and transaction costs. He implicitly discusses these costs together as: (3) administration + transaction costs. In general, administration costs are likely to be high in the case of a centralised system such as town planning, lower in the case of the decentralised private law systems, and very low in the case of no legal regulation. Transaction costs will be high in the case of no legal regulationFootnote 27 and low in the case of a fully centralised system because, in the latter, no private bargaining takes place. The precise shape of the curve in Figure 2, below, will thus depend upon the transaction costs associated with private bargaining under a system of covenants, which falls somewhere on the middle of the right hand side of the horizontal axis. Ellickson, analysing land use generally, considered these costs to be high. If, however, they are low, then the relationship between choice of system and administration + transaction costs is likely to be as shown in Figure 2. The town planning system falls towards the left of the horizontal axis.

Figure 2 Relationship between choice of system and administration + transaction costs where transaction costs associated with private bargaining are low

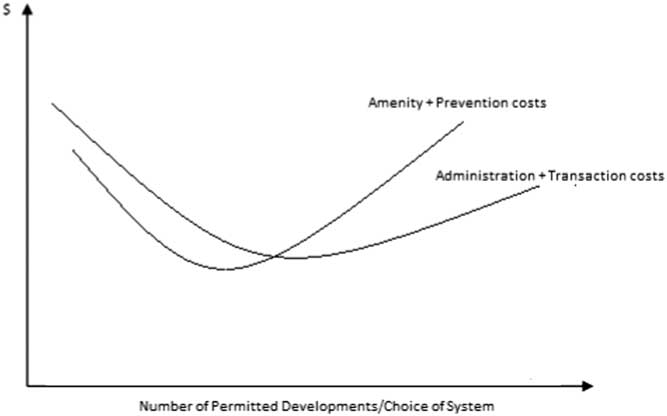

Parts of Figures 1 and 2 are combined in Figure 3, where the horizontal axis represents both choice of system and number of permitted developments (low to high). Assuming, as discussed further below, that fewer developments would be permitted the more centralised the system, and assuming that more developments will occur in a system with no legal regulation,Footnote 28 these two curves can be plotted on the same axes.

Figure 3 Amenity + prevention costs and administration + transaction costs

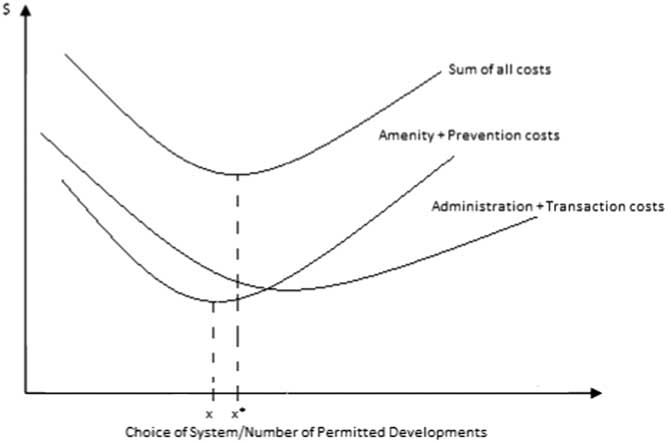

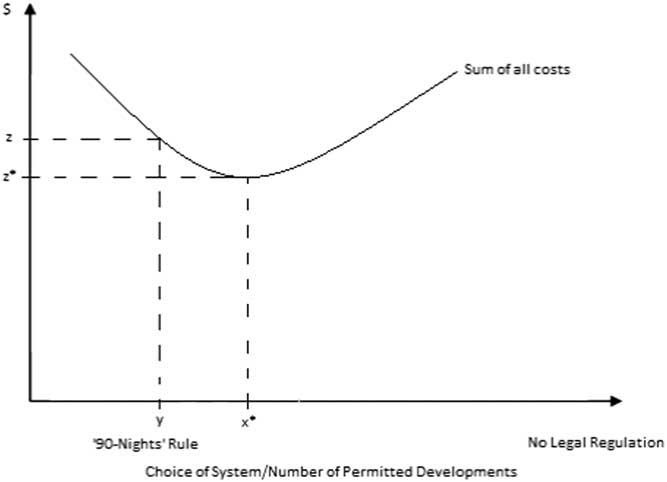

The preferred system in terms of social efficiency is that which sets the number of permitted developments at the level which minimises the sum of all four costs. That is shown below in Figure 4 at point x*. Note that point x* is likely to represent a less centralised system, with more developments permitted, than point x, at which was minimised the sum of (only) amenity and prevention costs.

Figure 4 Minimisation of sum of all costs

Ellickson’s conclusion that the transaction costs of private law systems are likely to be higher than those of centralised public law systemsFootnote 29 was due to his belief in the existence of high costs of private bargaining between neighbours over covenants. His view was that, whilst in the case of development schemes – where one developer may insert efficient covenants in the sub-leases of contiguous properties – those transaction costs would be low; in the case of older neighbourhoods,Footnote 30 the costs of bargaining and the problem of free-riding, would increase them. With regards to claims in nuisance, Ellickson suggested a reformulation of the doctrine which, amongst other things, would give the claimant a choice between receiving damages, or paying compensation to the owner of the let propertyFootnote 31 in consideration of receiving an injunction.Footnote 32 Such a solution would, he argued, be more socially efficient than town planning and capable of covering more cases than covenants alone.

Ellickson did not consider the “second-order transaction costs”Footnote 33 which are presented by the existence of nonconvexities. In this paper, these are considered separately, at the end of Part V below.

III Town planning in England: background and public/private interest analyses

The English town planning system has four major stages: (1) the creation of development plans; (2) the consideration of applications for permission and grant or refusal; (3) appeals to the planning inspectorateFootnote 34 against refusal or to the High Court against permissionFootnote 35 plus onward appeals; and finally (4) enforcement of planning control including the issuing of enforcement notices to unpermitted developments and prosecution in the criminal courts for failure to comply. The system is operated and funded by the relevant local government authority. At stages (1), (2) and (3) the authority is obliged to take into account the views of incumbent local residents,Footnote 36 for whom it is free to submit objections. At the permission stage, the authority must also take into account both the development plan and any other material consideration. At the application and/or the appeal stage “planning conditions” may be attached to a grant of permission, which may seek to limit the use of the land.

Anthony Ogus arguesFootnote 37 that there is a strong prima facie economic justification for the English town planning system. Both he and Ellickson point to the bargaining costs and free riding problem that exist in the case of the private bargaining. Ogus also points to the fact that in the paradigmatic case of newly constructed development, the costs associated with reversal of an unpermitted development justify a system of prior approval in order to avoid socially inefficient outcomes.

In considering the private interest implications of the town planning system,Footnote 38 he points out that a balance usually exists. On the side of the incumbent residents, ie owners of neighbouring properties, is the tendency of the (democratically elected) authority to maximise its vote share by designing its policy package to appeal to the median voter.Footnote 39 As a result, the policies of those parties are likely to converge.Footnote 40 Ogus argues that in residential areas the median voter is always more likely to be an incumbent resident.Footnote 41 Prospective developers, on the other hand, are normally large and well-organised commercial interests, which have the propensity to capture the authority and which are better equipped than incumbent residents to make use of the procedures of the system. Whilst Ogus was discussing land use regulation generally, in the specific case of short-term lets, I believe that the first part of this analysis remains correct. Given that short-term lets are, by definition, to be found in residential areas, it makes sense that the median voter in a local government borough where short-term lets are proposed is also most likely to be an existing resident. As such, theory dictates that the incumbent governing party is usually more likely to be opposed to a grant of planning permission for change of use to short-term letting.

IV Short-term lets: spill-over effects and loss of residential amenity

In this paper, the focus is primarily upon peer-to-peer short term letting, of the kind facilitated by platforms such as Airbnb. These business models are a part of what is known as the “sharing economy” which facilitates the more efficient use of assets by enabling individuals to share excess capacity in those they own – in this case, residential properties.Footnote 42 This often takes advantage of so-called “network effects”. The firms provide a platform in which individual A and individual B (in this case someone offering and someone seeking a short-term let, respectively) can connect. In such a situation, the addition of one more participant to the network brings a benefit to all users in the network. After a certain number of users have joined the network, it becomes self-sustaining. Importantly, this means that firms such as Airbnb have an incentive to expand the network up until this point, however, the firm is disincentivised from taking an active role in regulating the activity itself. In the case of some online platforms, a peer-to-peer review system is used, whereby both the offeror of the short-term let, and the user, can comment upon their counterpart. Such systems do not allow the occupiers of neighbouring properties to play any role in the review process, and handling the concerns of neighbours is seen as the task of the civil authorities. The conclusion to be drawn from this is that, in relation to amenity effects, these business models are unlikely to regulate themselves. A public law solution, or a private law solution between the occupiers of neighbouring properties and those of the let properties, are thus the default options. In the model presented below, I evaluate the choice to be made between them by comparatively analysing the systems in terms of social welfare.

For the sake of precision, a short-term let is defined here as the case where the whole or part of a residential property, formerly used by the owner as a private residence, is rented out for a fee as visitor accommodation for a period between one night and six monthsFootnote 43 without the use of any written tenancy agreement.Footnote 44 Short-term lets have been the subject of controversy in many cities worldwide.Footnote 45 In the British IslesFootnote 46 the records of parliamentary debates and committee hearings reveal concerns ranging from amenity effects, to concerns over the protection of residential housing stockFootnote 47 and concerns over non-payment of tax including income tax and business rates.Footnote 48 My focus here is limited to the amenity effects.

1 Amenity effects: research

Residential amenity forms a part of the utility derived by the occupiers of residential properties from their occupation. Parliamentary records and planning appeal decisions from the UK and Ireland indicate that amenity effects are considered to be a serious problemFootnote 49 in the case of short-term lets. As a foundation for the analysis in Part V, I first discuss the results of my research into the nature of the amenity effects. My research covered 12 planning appeal decision letters – from England, Scotland and IrelandFootnote 50 – and three court cases. It also encompassed debates on the subject held in the UK, Scottish and Irish Parliaments, as well as committee reports and government publications from the three jurisdictions. The planning reports include all those which were publicly availableFootnote 51 from the UK and Ireland at the time of writing. The purpose of examining the legal sources here is not to undertake a formal empirical analysis, but rather to set the scene for the theoretical discussion which follows. In particular, the legal sources provide some prima facie evidence of two things. First, that residential amenity effects are considered a serious problem in the jurisdictions discussed. Second, that these amenity effects are considered serious enough to warrant a planning enquiry mainly in cases where there exist shared facilities such as communal entrances, shared spaces and common walls.

a Town planning context: development, material change of use, and the 90-nights rule

As a general rule of town planning, all “development” of land first requires planning permission from the local authority:Footnote 52 this is the case in England, Scotland and Ireland. The definition of “development” covers both structural alterations and any material change of use.Footnote 53 The latter will usually involve a movement between use “classes”. A residential property that commences use part-time as a short-term let comes within the definition of development if the change of use is considered “material”. The 90-nights rule effectively states that the change of use from residential to short-term letting will be material, and will require planning permission, when the period of short-term letting exceeds 90 nights in a calendar year.Footnote 54

b General comments

The facilitation of short-term letting is hailed in all three jurisdictions as a good thing, which brings a variety of benefits.Footnote 55 One theme, which characterises my findings, is the difficulty in identifying the materiality threshold and in determining to which use class the property has moved.Footnote 56 This has necessitated a case-by-case approachFootnote 57 in each country, which, I suggest, has increased the likelihood of appeal by the source property owner in the case of refusal of permission, and/or a judicial review challenge by neighbouring residents in the case of grant. Another observation is that any structural alteration to a residential property is likely to be covered by a permission requirement separate to that arising from change of use. As such, in the analysis in Part V below, I assume that the conversion to short-term letting takes place without structural alteration nor thus any significant reversal costs.

Enforcement of planning control is considered a problem. The parliamentary records emphasise that the authority in question lacks information concerning both whether a property is used as a short-term let, and for what duration each year.Footnote 58 Arguably, if the chosen system is town planning but there is no 90-nights rule in place, then enforcement is less costly. That is because online platforms are publicly accessible and detection simple. In addition, neighbouring residents are likely to report the activity. It should be noted, however, that the cost to the local government authority of gathering sufficient evidence to successfully pursue a criminal conviction for breach of planning control is still high. Moreover, given the limited enforcement resources available to the authority, and the incentives in place for neighbouring residents to report a short-term let even in cases where the externalities are negligible, the authority is likely to be inundated with reports and unable to prioritise enforcement to those cases where the externalities are truly problematic.

Under the 90-nights rule, the process of detection is undoubtedly more costly.Footnote 59 The authority not only has to detect properties being used a short-term lets, but also must identify those used for more than 90 nights in a calendar year. A search of the online platforms will not necessarily reveal this information. Reliance upon the reports of neighbouring residents is also problematic for the reasons already given. It should be noted that some major platforms have now agreed to cooperate with the planning authorities in the UK and elsewhere to remove a listing automatically after it has been let for 90 nights.Footnote 60 It was seen, however, that this mechanism is ineffective as an aid to enforcement, as users can simply switch between platforms once being removed.Footnote 61

c Nature of the amenity effects

In assessing this, it is important to distinguish between those effects which are covered by legal remedies outside of the town planning system, and those which are not. Here, it is assumed that the 90-nights rule, where levelled at amenity effects, has been introduced to target those not already covered by other legal remedies.

Turning to these, from my research I have identified four categories: (1) annoyance caused by general disturbance; (2) fears over security; (3) negative feelings regarding the nature of activities taking place at the let property; and (4) negative feelings regarding a lack of community cohesion in neighbourhoods. These effects are highly fact-sensitive to specific cases. Clearly, to make an optimal decision on a planning permission application will require both solid evidence of the nature and extent of these amenity effects and of the values attached by individual neighbouring residents to their loss of amenity. Concerning annoyance caused by general disturbance, my research indicates that the times of activities are key.Footnote 62 The effect seems to be related to differences between the daily routines of neighbouring residents, and those of the users of short-term lets, as well as those who attend to service the let properties (where relevant).Footnote 63 Late night arrivals are considered particularly troublesome, as is the buzzing of doorbells.Footnote 64 The frequency of arrivals and departures is objected to,Footnote 65 reflecting the tension between the daily routines of permanent residents and visitors. In relation to security fears, I do not refer to actual criminal activity or antisocial behaviour (as these are covered by other remedies), but rather fear of the same. It seems to arise from neighbouring residents being unsure of what type of people are staying at the let property, and whether they represent a security threat.Footnote 66 A lack of security checks on users is mentioned as a concern which raises fear of criminal activity.Footnote 67 There is also often concern that the repeated use of communal entrances raises the risk of entry by burglars, and thus presumably the fear of becoming a victim of crime.Footnote 68 Negative feelings regarding the nature of activities taking place at the let property seems to come from a sense of disapproval which neighbours have regarding those activities. “Party activities”,Footnote 69 “party-type activities”Footnote 70 and “stag and hen parties”Footnote 71 are mentioned on multiple occasions, often with reference to drunkenness.Footnote 72 In one case, the use of the source property for “video shoots” is mentioned.Footnote 73 Finally, in relation to negative feelings regarding a lack of community cohesion: one dimension of this is that neighbouring residents have little or no opportunity to engage in social interaction with the users of the short-term lets.Footnote 74 Another related dimension is a fear over a lack of good manners from users of the let property. A “possible lack of consideration” for neighbouring residents is mentioned more than once in the planning appeals.Footnote 75

The first point to note is that many of the amenity effects identified cannot be controlled through the use of planning conditions, as to prohibit them would either serve no planning purpose (ie a purpose concerning the use of the land itself)Footnote 76 or are likely to be considered manifestly unreasonable.Footnote 77 Second, the amenity effects are localised in nature, and affect only a small number of people. Assuming we consider only one short-term letting unit, these affect only the immediate neighbours of that unit. Third, of course, the nature of the amenity effects is such that problems are much more likely to arise in a development scheme or multi-unit apartment block, where entrances and communal areas are shared between neighbouring residents.

Turning to four more generalised points which come out of the research; the first is that the effects identified are neither irreversible nor catastrophic. They are considered harmful because of the probability that, without prohibition, they will continue indefinitely. The loss of residential amenity would eventually be manifested in some reduction to the market value of the neighbouring properties. That reduction in value only exists for so long as the amenity effects continue and thus, if enjoined, the value of the land recovers. Second, in the planning appeals which I have researched, a lack of available evidence regarding the nature and extent of the amenity effects is evident. This follows from the fact that the change of use must be permitted before it can proceed. In some cases, the authority seeking to uphold its refusal of permission must rely upon evidence of the experience of neighbouring residents at other properties where short-term lets have taken place,Footnote 78 a solution which is unsatisfactory given the fact-specific and subject-specific nature of the spill-over effects.

V Comparative analysis

I now turn to analyse the 90-nights rule according to the framework adopted by Ellickson. Here, amenity costs are ultimately reflected in a reduction to the market value of the neighbouring properties. Given that the only major prevention strategy available to the neighbours is to sell their properties and move, I include this in the amenity costs (reduction in value of land). The prevention cost to the owner of the let property is the income he forgoes as a result of the short-term let being prohibited, either at the prior approval stage or later. This prevention cost is also reflected in a loss of some of the market value of the source property due to its loss of utility. These also include the cost of reversal, where the use as a short-term let was ongoing. The administration + transaction costs include: the direct cost to the authority of running the town planning system, including as passed on in part to the let property owner in fees to use the system. They also include the costs to the authority of policing planning control as well as enforcing it. The transaction costs are the costs of private bargaining between neighbours in the case of the private law systems.

I consider the case of a short-term let of more than 90 nights’ duration in a calendar year under four scenarios in which that use may be enjoined: (1) a requirement to obtain planning permission according to the 90-nights rule which, for the sake of brevity, I analyse in the case that the application is refused; (2) the use of covenants to prohibit the use; (3) the use of nuisance to prohibit the use where the only remedy is an injunction; and finally (4) the use of nuisance where the claim is successful and there is a choice for the claimant between damages and a compensated injunction.

In practice, these systems are not mutually exclusive. Systems (3) and (4) are obviously alternatives; however, covenants and nuisance (in either form) can and, it is argued below, should sit side by side as private law mechanisms to tackle the amenity effects. In terms of the compatibility of nuisance with town planning, a grant of planning permission does not excuse a nuisance in English law; however, it may affect the question of liability by virtue of having changed the nature and character of the locality.Footnote 79 Nuisance and planning permission may therefore operate concurrently. As between town planning and covenants, where planning permission is required but not obtained, this lack of permission cannot be circumvented through private agreements between neighbours. On the other hand, where permission has been granted then neighbours can still seek agreement to a covenant – from the permission holder (the owner of the let property) – not to use their property as a short-term let. In the analysis below, covenants are analysed with an awareness that claims in nuisance are also possible (and vice versa) but the 90-nights rule is assumed to operate alone.

1 Amenity + prevention costs

In a system where planning permission is required according to the 90-nights rule, the amenity costs will be zero where permission is refused. The prevention costs upon refusal would be high to the let property owner who would forgo the substantial income from short-term letting, and he can expect some loss of property value. There is no reversal cost.

Where covenants are used to prohibit the use ex ante, there will be a reduction in the value of the property which would otherwise have become a let property.Footnote 80 This, however, will have been reflected in the purchase price of the “would-be” let property and thus does not represent a prevention cost to a subsequent purchaser. There is no reversal cost. Where a covenant is entered into after short-term letting has already commenced, there may be some minor amenity costs to the neighbouring resident caused by the initial period of short-term letting, but there is ultimately no reduction in the market value of the neighbouring properties because the use is prohibited forthwith. The covenantor is compensated for the loss of value to his property through payment of the agreed price. There are potential reversal costs but these are likely to be minimal.

In the case of a successful nuisance claim where the only available remedy is an injunction, the amenity costs up to the point of the injunction being granted are low and there is no reduction to the value of the neighbouring properties in the long term. The prevention cost to the let property owner is high once the injunction is granted, and there is a concomitant reduction in the market value of the let property. There are potential reversal costs here but, as above, these are likely to be zero.

In the case of a nuisance claim with a choice of remedies, I assume the claim is successful and the court is able to determine objectively the loss of market value of the neighbouring property based upon the claimant’s evidence. In this case, the court would set the price at which the injunction could be purchased and the claimant would choose the remedy which accorded with her subjective valuation of her loss of amenity. If set accurately, then this would produce an outcome more socially efficient than if the claimant had only the option of an injunction. Moreover, in the shadow of publicly reported nuisance judgments, parties in other cases could bargain between themselves over the price of covenants to restrict use of properties for short-term lets. They would use the objective valuations, and the threat of court action as a backup, to reach an outcome between them which minimised the sum of amenity and prevention costs. There are potential reversal costs but again, these are likely to be zero.

2 Administration + transaction costs

Considering the 90-nights rule, there are the direct costs of operating the system, incurred potentially at all four stages, in the form of employee salaries and other overheads. The first two stages are mandatory and at the third stage which, it is noted, is more likely to be necessitated given the difficulties in determining such applications, there are the considerable costs to the authority of defending the decision at a planning appeal and/or in court proceedings. The cost of the second and third stages is increased because of the fact that, as the short-term letting has not yet commenced, the authority lacks information and evidence regarding even what the amenity effects will be.Footnote 81 Meanwhile, neighbouring residents have an incentive to object at these stages where it is free for them to do so. This factor is likely to lead to an increase in refusals at the second stage, which are upheld at the third, increasing the likelihood of High Court challenges. Whilst the overall costs to the authority of the four stages may benefit from scale economies, I explain below my belief that these economies are probably insufficient to render the direct costs of the planning system lower than the direct costs of the court system in the private law scenarios, although I accept that this is ultimately an empirical question. Particularly costly is the fourth stage, the policing and enforcement of planning control.Footnote 82 Without assistance, authorities lack the necessary information to determine: (1) when and where an unpermitted short-term let is taking place; (2) whether this short-term let exceeds a period of 90 nights in a calendar year; and (3) the nature and extent of the amenity effects. Authorities are reliant upon information from neighbours in the form of complaints. As explained above, this is likely to lead to over-enforcement. For those neighbouring residents, the town planning system is free at the point of use.Footnote 83 Given the benefit to neighbouring residents of short-term letting being enjoined,Footnote 84 this provides incentives to exaggerate the extent of the amenity effects. The likely result is that many enforcement notices are issued in cases where the neighbouring residents would not have brought a nuisance claim or had sufficient willingness to pay for a covenant. This is likely to lead to a greater volume of enforcement action overall than when the private law systems are employed.

Transaction costs are not considered for the 90-nights rule as there is no private bargaining involved.

Under the covenants scenario, there are no direct costs flowing from the court system if the covenants are adhered to. Of course, if the covenants are breached then these costs materialise in use of the courts to enforce. Clearly, court enforcement will be an administration cost of this system. It would be for an empirical analysis to determine whether these administration costs are likely to outstrip those of the town planning system. My argument is that they are unlikely to. This is because only a small subset of short-term let cases where covenants provide for the problem will ever require enforcement through the courts. Most let property owners would abide by the covenants. The potential for rational apathy and the free rider problem to distort incentives to enforce covenantsFootnote 85 is overcome by two factors: (1) only small numbers are likely to be involved and the harm is localised, as such free riding is unlikely; (2) in English law an award of costs from the other side follows from a successful claim, thus rational apathy is unlikely. It is also unlikely that there will be over-enforcement given that claimants have to pay fees to use the court system upfront, before they will be reimbursed in a costs award. The cost of monitoring compliance with the covenant is low given that neighbouring residents possess low cost information on whether a breach has occurred.

As to transaction costs, whilst bargaining costs and the free-rider problem are given as justifications for preferring town planning over private law systems, it follows from the small numbers involved in these cases, and the localised nature of the harm, that these costs are unlikely to be severe. Admittedly, there are some bargaining costs involved in creating covenants, and in terminating them once they have become inefficient. However, because these amenity effects are more likely to arise in development schemes and multi-unit apartment blocks, where developers are able to insert efficient covenants into head-leases, and are in a position to facilitate termination at a later date, these transaction costs are likely to be low overall.Footnote 86 In older neighbourhoods too, the small numbers involved plus the effect of publicised nuisance judgments, are likely to facilitate private bargaining at low transaction cost.

Under the scenario using the doctrine of nuisance where only an injunction is available, there are no bargaining costs as the system operates ex post. Monitoring costs are low. The same points made above regarding optimal levels of enforcement hold true for nuisance as they do for covenants. As it is envisaged that covenants would cover short-term lets in development schemes and multi-unit apartment blocks, and that, in light of publicised nuisance judgments, parties in older neighbourhoods would be able to bargain for covenants in at least some cases, it is likely that only a small subset of cases would require resort to the courts. In a scenario where nuisance is used but there is a choice between damages and a compensated injunction, the same analysis applies, save that an even smaller number of cases would require court involvement. This is because bargaining for covenants would be facilitated by the existence of publicised judgments, which set objective values at which injunctions can be “bought”.

3 Summary: comparative social efficiency

Before considering the issue of nonconvexities, and looking only at the sum of amenity, prevention and transaction + administration costs, it is clear that the 90-nights rule will provide a less socially efficient solution than the private law systems. It is likely that too few short-term lets will be permitted, and total costs will not be minimised. This is shown in Figure 5 below. The social losses are determined by z-z*.

Figure 5 The social inefficiency of the “90-nights” rule

4 Private interests and the 90-nights rule

Some private interest elements have already been touched upon above. To these I add as follows, specifically in respect of short-term lets. First, in areas of a city where mixed residential and commercial accommodation uses are permitted, the proposed developer of a short-term let is likely to face opposition not only from incumbent residents, but also from the established commercial interests of the hospitality sector. The latter are likely to be well organised and capable of capturing the town planning system. Second, short-term lets are small operations, not well organised or resourced: they are unlikely to capture the system at any stage. Third, the fact that the town planning system is free at the point of use for incumbent residents provides incentives to oppose short-term lets at all four stages, and to exaggerate spill-over effects at the fourth stage.

A potential counterargument to all is that online platforms, which are well organised and well-resourced for lobbying, might restore balance. Whilst it is true that the platforms have the ability to lobby for legislative changes at the national level, in the case of planning decisions on specific cases made by local authorities, the platforms have little opportunity to influence proceedings. Moreover, as noted above, the platforms have little incentive to become involved in the regulation of amenity effects, as the platforms merely facilitate the connection of those seeking and offering short-term lets.

Thus, taking into account private interest factors, it appears likely that the proposed developers of short-term lets will face significant obstacles in obtaining permission.Footnote 87 This, in turn, makes it more likely that short-term lets will be prohibited, and that there will be allocative inefficiencies caused by the elimination of amenity costs, and consequent increase in prevention costs.

The question remains, which system or combination of systems is represented by point x* in Figure 5 above? The analysis in this part has strongly suggested that it will be a combination of covenants and nuisance with a choice for the claimant between damages and a compensated injunction.

5 Nonconvexities

The analysis above, however, does not incorporate the issue of nonconvexities, which represents the major remaining justification for town planning itself and thus the 90-nights rule. It has been explained above that private bargaining may lead to an outcome which fails to maximise aggregate land values. The question now is whether nonconvexities justify the full requirements of the town planning system and the 90-nights rule. My suggestion is that it justifies the use of development plans, but not prior approval and public enforcement. There is also little justification for the 90-nights time threshold. It might be the case that the segregation effects of development plans could be incorporated into the private law systems. For covenants, which will cover development schemes and multi-unit apartment blocks, the scheme as a whole will require planning permission and thus the development plan will be utilised. What is left, therefore, is the case of older neighbourhoods and the use of nuisance (with or without a choice of remedies). It is possible that local rather than global optima will materialise in such cases because judges deciding nuisance claims are not town planners.

Could the doctrine of nuisance take account of nonconvexities? Development plans may provide for an area or areas of the city which are suitable for short-term lets. It might be possible for these development plans to be used by courts when determining liability in nuisance claims in older neighbourhoods. It appears that the English courts do not count the terms of a development plan as a major factor in determining liability in nuisance cases,Footnote 88 in fact, a grant of planning permission itself will not excuse a nuisance. In my view, the doctrine of nuisance in English law could and should be reformed such that the local development plan could be referred to in court in order to determine the nature and character of the locality when determining liability. The full case for this reform would be the subject of another paper.

The analysis conducted here suggests that a reformulated nuisance doctrine, combined with the use of covenants, would be closer to point x* in Figure 5 above than the 90-nights rule, and in such a case that rule – and any requirement to obtain permission – should be abandoned.

VI Conclusions and limitations

It follows from the analysis in Part 5 that other reforms to the tort of nuisance would also be desirable if the combination of private law remedies were to be geared towards a socially optimal outcome. These changes would include: (1) the availability of a choice of remedies between damages and a compensated injunction; and (2) some means of tackling private interest influences in the creation of development plans.Footnote 89

There are further limitations to the analysis undertaken. Other problems with short-term lets are excluded here. In particular, the housing supply issue is central to the choice of system. It is, however, questionable whether prohibition of short-term lets is a long-term solution to this problem, rather than the allocation more land for newly built residential developments. Concerns over regulatory competition vis a vis the established hotel industry is an area in which proposed regulation through the town planning system is susceptible to manipulation by lobbying. As regards safety, tax and insurance issues, these may point to a prior approval approach in the form of registration or licensing. The latter need not, however, be as costly as the 90-nights rule. Another limitation is the omission of distributive considerations.

The conclusions here are also limited by the assumptions of the model. If it could be shown that amenity spill-overs occur more regularly in older neighbourhoods than in multi-unit apartment blocks and development schemes, or if it could be shown that the transaction costs of covenants inserted into head-leases is high compared with the transaction costs of bargaining between neighbours, then the theoretical conclusions would be incorrect. It is considered unlikely, however, that either of these propositions would be the case. A final limitation is that the analysis is undertaken only within the framework of the approach taken by Ellickson in his 1973 paper. It was believed that this was the most appropriate framework to use given the specific questions investigated here.

Despite these limitations, this analysis does provide some evidence that the use of the 90-nights rule to tackle the amenity effects is unlikely to be socially efficient as compared to the combination of private law systems outlined at the end of Part V above. As such, the conclusion supports the proposition that courts, properly availed of public information (the development plan) and private information (from litigants), are better placed to regulate amenity effects in the case of short term letting than legislators, and this must put in place a rule of general application.