The dire experience of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Canada, has brought about a dramatic public shift in health debates. After the 2015 federal election, the question of adding coverage for outpatient prescription drugs (the policy option known as ‘pharmacare’) to the federal−provincial framework of universal coverage for physician and hospital services (long known as ‘medicare’ in Canada) had leapt to the top of the health policy agenda. But as the COVID-19 pandemic ravaged Canada's long-term care facilities, which accounted for more than 80% of COVID-19 deaths, Canada's patchwork arrangements for long-term care (Allin et al., Reference Allin, Fitzpatrick and Marchildon2020; Hsu et al., Reference Hsu, Lane, Sinha, Dunning, Dhuper, Kahiel and Sveistrup2020) became the cynosure of public attention while pharmacare was essentially driven from view. Historically, both of these sectors, along with others (such as dental and eye care) that fall outside the almost exclusively publicly funded medicare framework, can be considered the step-children of the Canadian health care state – relegated to an uncoordinated realm of mixed private and public finance with coverage provisions that vary widely across provinces, and in which the federal government plays virtually no role (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Miller, Quesnel-Vallée, Caron, Vissandjée and Marchildon2018). As pharmacare and long-term care vie for a place on the policy agenda, with long-term care currently dominating, it is worth considering what implementation options are available to federal and provincial governments in the current context.

Although an outstanding issue among health care policy experts since medicare was established over a half century ago, national pharmacare – the phrase most often used in the media – has only rarely attracted public interest. Long struck by the fact that outpatient pharmaceuticals had been excluded from Canadian medicare unlike the majority of UHC systems in the world, health policy scholars often argued in favour of adding prescription drugs to medicare (Boothe, Reference Boothe2013). However, public finance economists as well as policy advisors within governments argued in favour of far more incremental changes that could address the needs of a minority of Canadians without incurring the political and fiscal costs involved in national pharmacare (Adams and Smith, Reference Adams and Smith2017).

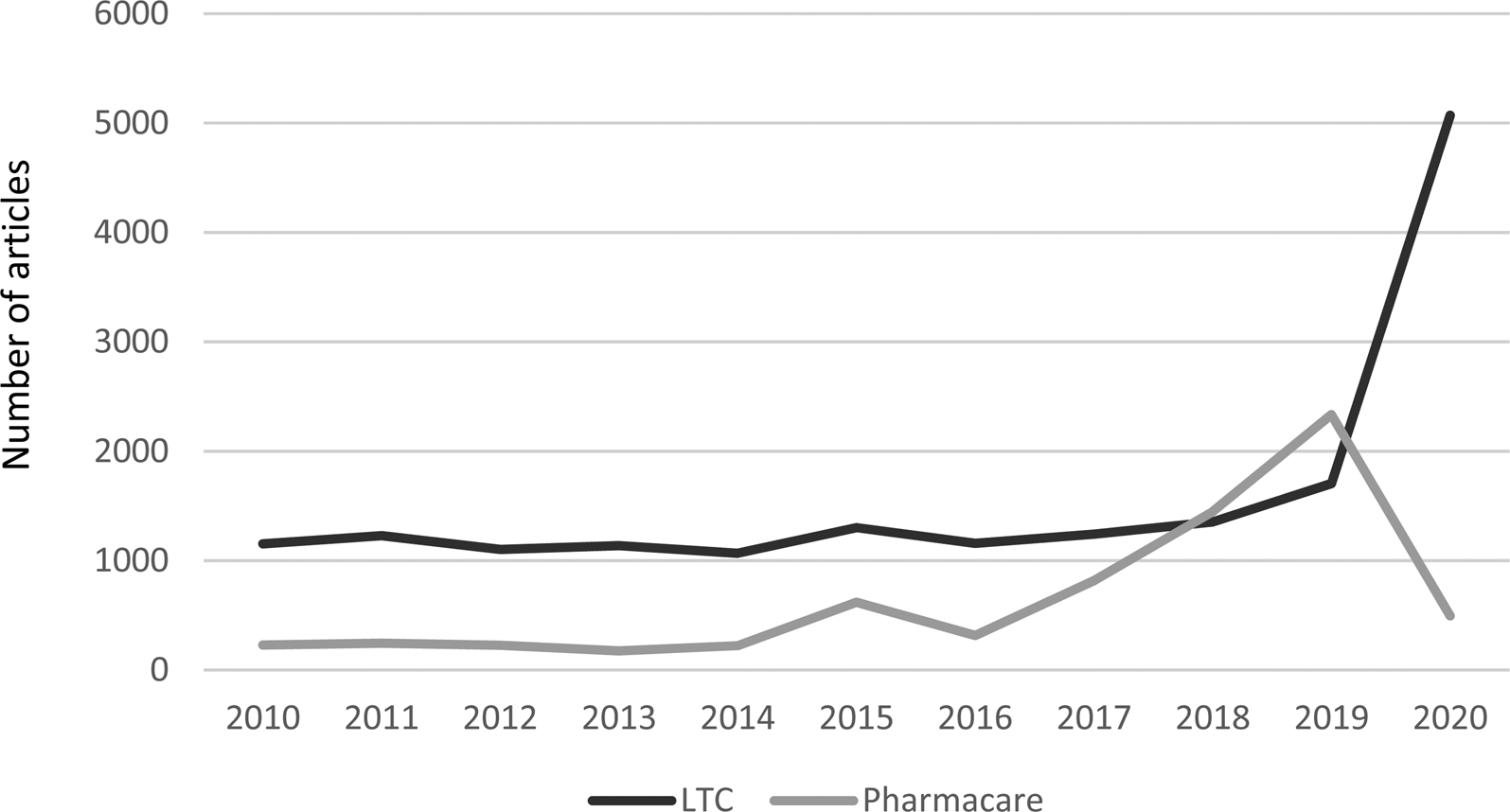

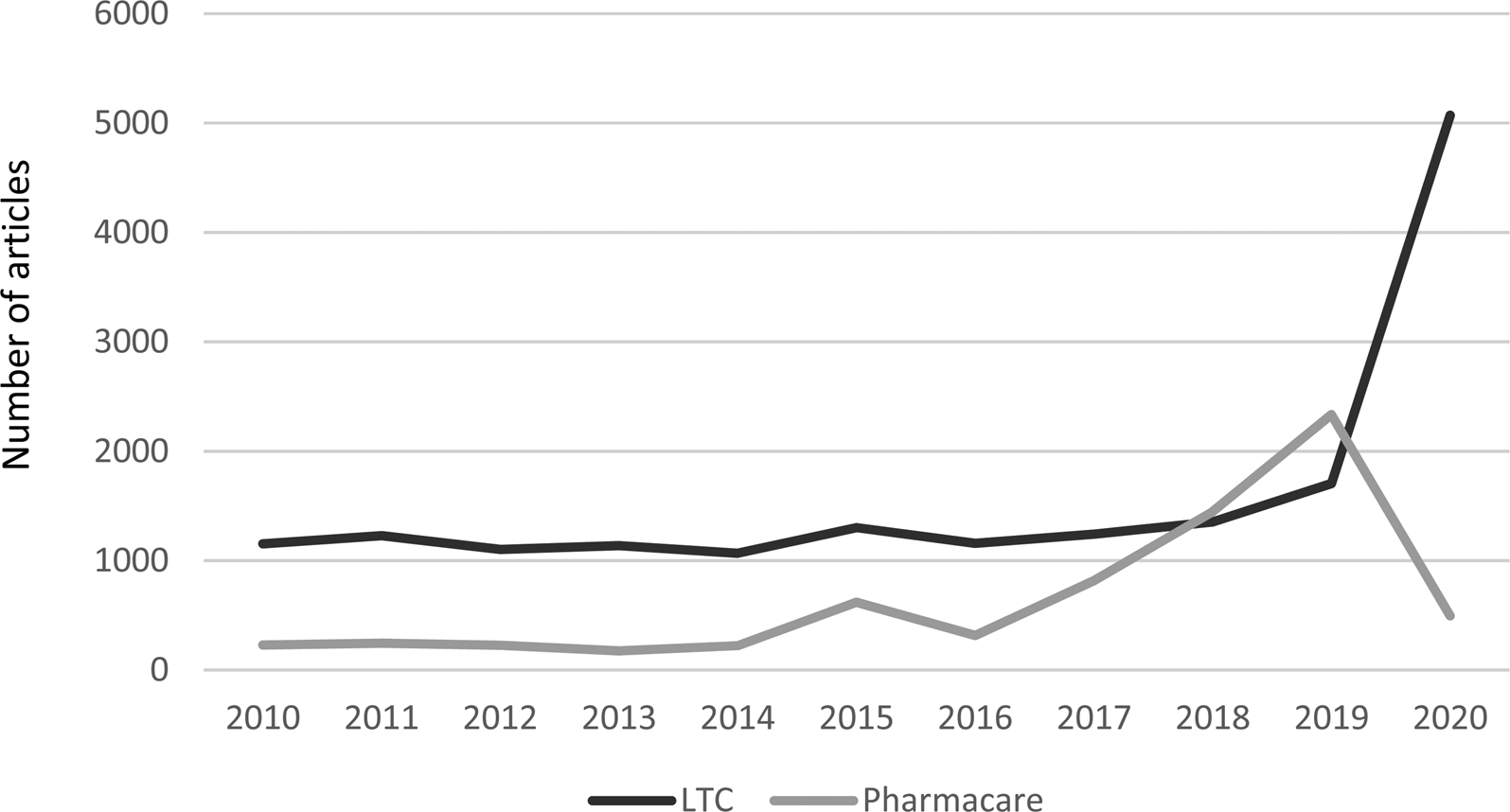

This debate was almost entirely confined to experts and insiders. Most middle-class Canadians received prescription drug coverage through employment-based benefit schemes while the very poor (defined as those receiving social assistance from provincial governments) and those past retirement age were covered in provincial safety net drug programmes (Boothe, Reference Boothe2018). Meanwhile, long-term care has had greater salience for the public. There are few public opinion polls that pit pharmacare against long-term care as a priority for public policy, but those that do give long-term care an edge (see e.g. Soroka, Reference Soroka2007: 34, 38). What can be demonstrated more consistently is media attention to the two. Figure 1 shows the number of articles in Canadian daily newspapers with weekly circulation of at least 40,000 over the past decade referring to long-term care together with ‘government’ vs pharmacare – the term used for universal drug coverage in Canada. Only in 2018 and 2019 did pharmacare overtake long-term care in media attention, as the federal Liberal government under Prime Minister Justin Trudeau wrestled with how (and even whether) to deliver on a plank from its 2015 election platform to address the pharmacare issue in response to public pressure from a few citizens' groups and a vocal expert group known as Pharmacare 2020 (Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Martin, Gagnon, Minzes, Daw and Lexchin2015).

Figure 1. Media coverage of LTC/government* and pharmacare**, Canadian newspapers,*** 2000-2020****. Source: Canadian Newsstream database. *Counts only mention of LTC together with government. **Counts mention of either pharmacare or ‘universal drug coverage’. **Daily newspapers in Canada, in English, with weekly circulation >40,000, with continuous coverage in Canadian Newsstream database. ***To 20 September 2020.

Preoccupied by other policy priorities, the federal Liberal government temporized by encouraging an all-party Parliamentary Committee to work on the subject. When the Standing Committee on Health (2018) finally issued its majority report recommending the establishment of universal, single-payer pharmacare, the Trudeau government was still questioning the need for, and the fiscal cost of, single-payer universal pharmacare. As a consequence, it established its own Advisory Council on the Implementation of National Pharmacare chaired by Eric Hoskins, the former Ontario Minister of Health. The Hoskins Committee was asked to examine the costs and benefits of a single-payer, universal design as well as alternative approaches, including an alternative multi-payer design as well as a more modest ‘filling the gaps’ approach (Grignon et al., Reference Grignon, Longo, Marchildon and Officer2020). In its final report in June 2019, the Hoskins Committee firmly recommended the more ambitious single-payer design for national pharmacare (Government of Canada, 2019). Although the Liberals put a recommendation in favour of national pharmacare in its platform in the Fall election of 2019, it has since avoided the issue in the face of successive crises since the election as a weaker minority government.

Meanwhile, long-term care (LTC) has soared in salience. Although made evident in the pandemic, the weaknesses in LTC have existed for many years, including an increase in the average resident's level of physical and cognitive disability, the lack of a sustainable mechanism for the financing of LTC, the lack of integration of LTC across community care and acute care sectors, and the lack of fit between the appropriateness of facilities, the training of providers and the needs of residents with severe dementia and dementia-related conditions (Royal Society of Canada, 2020). Often seen as a backwater in provincial health ministries, LTC units in health ministries have spent their time largely focused on regulating and managing the status quo. Meanwhile, provincial governments have not invested in the building and maintenance of LTC facilities sufficiently to meet the growing demand, nor in properly educating, training or remunerating LTC staff, especially personal support workers, nor in enforcing standards in a sector in which care is provided by a mix of public, not-for-profit and for-profit providers. As a result, demand has outstripped supply, and the standard of care is highly uneven. In the current crisis, a disproportionate majority of COVID-19 deaths have occurred in private for-profit facilities (Grignon and Pollex, Reference Grignon and Pollex2020).

The federal Liberal parliamentary caucus, as well as the Liberal party's grass-roots organizations, have called for the government ‘to develop enforceable national standards for long-term care homes – and to provide provinces with the funding needed to meet those standards’ (Bryden, Reference Bryden2020). The government’s Fall Economic Statement established funding of up to $1 billion, to be allocated to provinces and territories on a per capita basis conditional on the submission of detained spending plans and follow-up reports. The Statement also made a number of targeted commitments including temporary funding for the training of personal support workers. Regarding national pharmacare, the government reiterated its commitment to work toward national universal pharmacare and outlined current steps toward developing a national formulary. The only funding announced, however, was for a national strategy for high-cost drugs for rare diseases. This funding would not begin until 2022-23, with the establishment of an ongoing stream of $500 million per year (Government of Canada, 2020).

1. Medicare has been stuck since late 1960s and the rapid displacement of pharmacare from the national agenda reflects how difficult it has been to expand universal health coverage

Canada's single-payer framework of universal coverage for physician and hospital services, established in provincial legislation under a federal legislative umbrella adopted in the 1960s, created a bilateral monopoly between the medical profession and government in each province as the central political axis of the health care state (Lazar et al., Reference Lazar, Lavis, Forest and Church2013; Marchildon, Reference Marchildon2016; Tuohy, Reference Tuohy2018, 142, 147). That axis has proved remarkably durable, despite periodic clashes over fee negotiations, and it underlies a regime of first-dollar comprehensive coverage that enjoys an iconic status in Canada similar to that of the NHS in the UK (Tuohy, Reference Tuohy2018: 124). The dominance of that axis, however, has left other health care sectors such as LTC and drugs outside the single-payer orbit. It has also reinforced the provincial level of government as the locus of effective decision making about the allocation of resources in health care. The similarity of provisions for coverage of physician and hospital services across provinces is fundamentally attributable to the commonality of the interests of organized medicine across provinces. The leverage of the federal government is limited to the conditions attached to its fiscal transfers to the provinces for health care, but those conditions take the form of broad principles (involving public administration, comprehensiveness, universality, portability and accessibility), not detailed prescriptions (Marchildon, Reference Marchildon, Marchildon and Bossert2018). Even the one specific provision – that any provinces allowing physicians and hospital to charge patients privately above the public benefit will be penalized by dollar-for-dollar reductions in the federal transfer – has resulted in only miniscule reductions over time relative to the size of the transfer (although on a few occasions it has triggered prolonged disputes). Similarly, accountability provisions under federal transfers for home care and waiting time reductions under the federal−provincial−territorial accords of the early 2000s were of very limited effect (Tuohy, Reference Tuohy2018: 413–16).

Wrapping either drugs or LTC or both under the single-payer umbrella would surely mean a substantial increase in federal spending, but it is doubtful that it would afford the federal government any greater leverage through its transfers than it enjoys in the physician/hospital sector. In fact, the federal government provided a separate unconditional per-capita grant to each province for ‘extended care’ for 20 years from 1977 to 1996, when it was folded into the general Canada Health and Social Transfer (later the Canada Health Transfer). No conditions were attached to the extended care transfer other than that each province publicly acknowledge federal support.

There are, however, modes of engagement other than cost-sharing that are open to the federal government in each area. The remainder of this paper sketches out some possibilities.

2. LTC reform through a social security mechanism

At first blush, LTC would appear to be akin to medical care, a sector in health care where the provincial governments hold near-exclusive jurisdiction deriving from the provincial power over property and civil rights as well as matters of a local nature in the province, an area made subject to federal principles under the Canada Health Act through the constitutional use of the federal spending power. It might therefore be argued that the federal government can similarly use its spending power to provide LTC funding conditional on provincial compliance with national standards. However, in the case of the Canada Health Transfer, federal standards on medical care relate to access. The problems in LTC exposed by the pandemic, in contrast, are principally about supply and standards of care, areas that are more firmly within the jurisdiction and control of PT governments. Nonetheless, there is scope for joint intergovernmental action in LTC by picking up instruments not yet considered, in two areas of concurrent jurisdiction: old age security (to provide both funding and harmonization of benefits) and immigration (to level-up standards for the qualifications and working conditions of caregivers). In this short piece we shall focus on only the first of these areas.

A programme of long-term care insurance (LTCI), linked to Canada's public pension arrangements, is much better suited to realizing the advantages of Canadian federalism than is the fiscal transfer model (Tuohy, Reference Tuohy2020). The Canada Pension Plan (CPP) is a public plan funded through employer and worker contributions and governed by a joint federal−provincial board, complemented by a universal layer of old age security (OAS) payments with an income-related guaranteed income supplement (GIS). Quebec operates its own Quebec pension plan (QPP) with parallel provisions. LTCI could be added to the CPP/QPP as a supplementary benefit, governed and administered through the established CPP/QPP infrastructure. Like the CPP/QPP, it would be funded through employer and employee contributions, but held in a segregated fund. An LTC benefit could also be added to OAS/GIS payments. Benefits would be paid in the form of a cash transfer to the beneficiary using a tiered schedule of flat-rate payments according to the beneficiary's level of assessed need for care. Payment would be triggered once the beneficiary's need has been assessed through existing provincial mechanisms but according to agreed-upon national standards; and could be used only for care from those continuing care organizations approved under the plan as ‘qualifying’ providers of institutional or home care in the provinces and territories. Establishing national standards for ‘qualifying’ providers would provide a mechanism for cross-provincial harmonization and learning.

There are several advantages to such a model. It builds on the long-established administrative structure of the CPP/QPP, and lies in an area of legitimate concurrent jurisdiction for federal and provincial governments (Béland and Weaver, Reference Béland and Weaver2019). On the CPP/QPP model, it could be designed to be self-sustaining so that contribution rates can be adjusted according to actuarial projections unless federal and provincial governments choose and agree to intervene. It would thus establish a dedicated LTC funding stream in perpetuity that would be sensitive to demographic change and would not have to be continually renegotiated through the budget process or in the federal−provincial arena, as is the case for the Canada Health Transfer and related transfers. Countries such as Germany, the Netherlands and Japan have demonstrated success with public LTCI and offer models from which Canada can learn (Peng, Reference Peng2020).

Numerous design details would need to be considered in the process of policy development. The principal challenge would be how to integrate LTCI with existing provincial programmes of LTC in institutional and home settings. The current and projected need for substantially increased operating expenditure – estimated to require an additional $14 billion (in 2017 dollars) for new nursing home beds by 2035 (Gibbard, Reference Gibbard2017) – means that LTCI should be seen as adding to, not replacing, current provincial funding for LTC. However, the LTCI benefit could free up provincial funding currently allocated to LTC and home care subsidies to individuals, which could be redirected towards increasing the number of places in institutional and home care programmes.

3. Federal pharmacare programme with voluntary exit by provinces

If eclipsed by the pandemic at present, the issue of national pharmacare has not gone away, and is likely to be kept alive by a highly engaged set of advocates within the policy community. Largely through the work of those advocates, moreover, the policy menu has been prepared to a greater degree than is the case for LTC. Historically, provincial and territorial (PT) governments have been managing their own public pharmaceutical programmes since the 1970s, mainly to fill in the gaps left by employment-based private health insurance. Each PT government accordingly has its own drug formulary and programme design that would have to be changed in order to achieve national pharmacare. The Quebec government has already indicated that it does not support a national pharmacare and is opposed to changing the design of its current multi-payer drug plan.

Notwithstanding this resistance, there are at least three arguments for establishing national pharmacare through a federal programme rather than 13 PT pharmacare programmes under pan-Canadian standards (Marchildon and Jackson, Reference Marchildon and Jackson2019). First, the federal government already has a constitutional foothold with its authority to determine which pharmaceuticals are safe enough to be sold in Canada as well as to provide patent protection for brand name drugs and to regulate their prices through the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB). In cooperation with the provinces the PMPRB also monitors the price of generic drugs.

Second, federal legislation can create a national pharmaceutical formulary enforced through law-based powers and processes that go beyond what any intergovernmental body has the capacity to achieve through federal−PT consensus. It is important to note that intergovernmental bodies by necessity operate on a consensus basis with those governments which voluntarily participate and have no law-making capacity. Such control would also give the federal government considerable leverage in any negotiations with the pharmaceutical industry in price discounting.

Third, while PT governments would insist on maximum federal cash and minimal conditionality in any negotiation on a shared-cost programme, they have, in the past, shown some willingness to hand over the full fiscal burden and responsibility of drug programme management to Ottawa as occurred in the discussions leading up to the 2004 First Ministers' Meeting that produced the Ten-Year Plan to Strengthen Healthcare under Prime Minister Martin (Marchildon, Reference Marchildon2006). The one exception to this was, and remains, Quebec. If Quebec, or any other PT government for that matter, did not want to exit the business of running a drug plan, it could negotiate an arrangement that in return for operating a drug plan that met stated federal objectives, it would receive a contributory transfer to help with operating costs. This might mean making some changes to the design of its programme if these design features actively undermined the ability of the federal government to run a pan-Canadian programme in an efficacious manner. If the Government of Quebec, or any other PT government, chose to continue to run its own programme without regard to these national objectives, it would continue to do so at its own expense.

4. Conclusion

It is becoming commonplace to note that the COVID-19 pandemic has opened a window of opportunity for policy reform in areas previously neglected. In health care in Canada, an increase in the presence of the federal government beyond the single-payer physician/hospital sector is likely to be one result. The current debate suggests that long-term care will be the first area of focus. While the perennial issue of universal drug coverage may be deferred once again as a consequence, it will not disappear. Policymakers both in government and opposition would do well to keep their quivers loaded in both areas.