I. Introduction

Recent years saw an ‘explosion of scholarship’ in the business and human rights (BHR) field.Footnote 2 This development makes it relevant to engage not only in a production of scholarly work on human rights implications of business activities, but also in a continuous assessment of, and reflection about, the state of the field.Footnote 3 Such assessment helps shape the research agenda and makes visible possible biases or limitations – and thus is essential in an effort to ensure the field evolves in a manner inclusive of different perspectives. Furthermore, the expansion of scholarly interest into previously unexplored topics, interlinkages and patterns as BHR matures as a field, brought about a growing specification of research and an opening of new areas of inquiry.

One such trend, to which this special issue is a testimony, is the growing interest in regional approaches to BHR. As this issue further highlights, Latin America in particular has been both of great interest to BHR scholars as a subject of research and a source of contributions to the discussion of the most pressing challenges in the field.Footnote 4 However, it has also been pointed out that there is a need to give ‘greater visibility to scholars from the Global South’ in this field that has been traditionally driven by perspectives from the Global North.Footnote 5 This is particularly relevant considering that, as Roberts has argued, the ideas and practices that characterize international law vary widely across the world’s countries.Footnote 6 They are shaped by their history, particular characteristics, and ways of understanding and practising international law.

This article, which presents the results of a systematic review of BHR literature in the Latin American context (hereinafter referred to as BHR-LA literature), seeks to add to the field by providing a baseline assessment of these contributions. Based on an analysis of the original database of BHR works that are either focused on the region as a subject, or contributed by Latin American authors, spanning 20 years from 2000 until March 2020, this study seeks to provide a ‘bird’s-eye’ overview of the ground covered in the subfield to date, the gaps that remain, the main trends, and the most pressing directions for further research. The article is structured as follows. First, the scope of the research and the methodology are discussed in Sections II and III. Subsequently, Section IV presents summary findings and Section V then outlines a few main contributions of Latin American subjects and scholars to the BHR field and suggests a research agenda based on the gaps identified, followed by conclusions.

II. Scope of the Research

The review covers articles in English, Spanish and Portuguese published between January 2000 and March 2020 (when the searches were conducted).Footnote 7

The focus of this review is on works that take an explicitly regional dimension, that is, contributions that deal with issues that go beyond the national sphere and seek to engage in the broader regional conversation on BHR. This approach prioritizes the transversal issues and contributions more likely to be shaped by the region’s shared history or its robust regional debates, and thus can be identified as regional discussions,Footnote 8 rather than scholarship addressing issues concerning exclusively individual countries. This focus guided our methodological choices (see ‘Search Strategy and Search Strings’ in Section III). Limitations of this approach are discussed in ‘Limitations’ in Section III.

In determining whether a work was about Latin America as a subject, we required that the region, a specific country within the region, or a specific case from the region, be a focus of the work. Out of concern for the manageability of the study, we considered the region to encompass all recognized countries in the Americas the official language of which is Spanish or Portuguese, with the exception of the Caribbean.Footnote 9 We included works that compared a Latin American case with a non-Latin American one, but excluded works that only made a mention of the region or a case without it being the main focus of the research. An author was considered to be Latin American if they had completed at least their first-level degree in a Latin American state. It has to be noted that this inevitably – like any method for ascertaining what a specific socio-cultural perspective in academic discourse means – is an imperfect proxy, and one open to contestation. How individual authors identify and whether they perceive themselves as part of Latin American academia is naturally beyond the scope of our inquiry. The proxy chosen – initial academic formation in the region – is helpful, however, in allowing us to avoid essentializing ‘Latin American’ as a nationality-based category. It is also suitable to an understanding of ‘Latin American’ as encompassing not only perspectives but also baseline access to resources – academic and other – that is likely to shape an individual’s participation in academic discourse.

The review was limited to works that engaged with, rather than merely mentioned, BHR approaches, concepts and institutions. Not included, therefore, were corporate social responsibility (CSR)Footnote 10 or business ethics approaches, unless their role in the text is limited to a juxtaposition with BHR.

That said, works in any discipline and using any methodology were taken into account, as long as they engaged with BHR approaches, concepts or institutions. While the field of BHR has emerged in the sphere of legal studies, our adoption of an interdisciplinary approach to the discussion was aimed at developing a review that is holistic and inclusive and that reflects the growing interest in searching interlinkages with other relevant fields.Footnote 11

As the article seeks to assess the role of Latin America in the BHR scholarship, beyond its scope are also political positions of Latin American states and legal, policy or institutional documents regarding BHR produced by international and regional intergovernmental organizations. While the role of Latin American contributions in multilateral political spaces is an important area of inquiry, it is a question analytically different from that being asked in the present article – about the role of the region in shaping the academic field of BHR.

For the purpose of the study, academic was taken to encompass works written by scholars, researchers and fellows affiliated with academic institutions, researchers working in the non-profit sector, and practitioners publishing the findings from their research or practice. This scoping, more inclusive than limiting the review to works published in peer-reviewed journals only, was adopted to reflect more accurately the de facto landscape of academic discussion on BHR, and ensure that we do not exclude authors who may have uneven access to publishing channels considered state-of-the-art in the Global North.Footnote 12 Therefore, we included all works published in academic journals, books, book sections, NGO reports, working papers and similar formats, as well as PhD theses.

III. Methodology

The database of BHR-LA works was drawn from both systematic literature searches and relevant additions identified by the authors. For the former, the systematic review methodology was used, which consisted of four steps: (1) design of the research protocol (research questions, scope, search strategy, selection criteria); (2) collection of data by conducting searches in academic databases using specific sets of keywords; (3) filtering of the data through specific inclusion and exclusion criteria; and (4) analysis of the data collected. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) was followed, where applicable.Footnote 13 Each of the steps is described in more detail in turn.

Selection Criteria

Our inclusion and rejection of works found through the search process followed a set of selection criteria defined based on the scope outlined above (Section II). Each work needed to meet all three inclusion criteria, and those that met at least one of the exclusion criteria were discarded. While quality appraisal is often a part of systematic reviews in some disciplines, the lack of focus on replicating quantitative analyses in our case and the nature of our research question (a diagnostic of the current state of the field), has rendered that step redundant. See Table 1 for a summary of the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Search Strategy and Search Strings

Data – works to be included in the review – were collected by searching three academic databases: Google Scholar (Google S), Scopus, and Web of Science (WoS).Footnote 14 First, preliminary searches were conducted using various combinations of keywords, of which these strings were selected that were most suitable, that is, specific enough to produce focused enough results, inclusive enough to include all potentially relevant results, and aware of the variability in terminology (see Table 2).

Table 2. Search strings

Subsequently, searches into the three databases were conducted using the six selected search strings. Following the first exclusion criterion (EC1), filters were applied in the search engines to limit the search to works published between January 2000 and March 2020. The total number of search results was 61,782. To further ensure manageability and focus of the study, in searches that yielded over 1000 results (all in Google S), the first 1000 ‘most relevant’ results were included.Footnote 15 This yielded 4862 results; Table 3 presents a breakdown by language and source.

Table 3. Systematic search results

Data Selection

Search results were subsequently screened for compliance with inclusion and exclusion criteria, first on the basis of the title and keywords, and subsequently through a full-text revision. After the removal of duplicates, we determined that 210 works met the criteria for the analysis, of which access could be obtained to 207 (see the discussion on access below). In order to counter the possible limitations of the results obtained from these databases, we conducted additional searches in the following sources: specialized journals, works published by members of the Academia Latinoamericana de Derechos Humanos y Empresas – a regional branch of the Global Business and Human Rights Scholars Association, and publications on BHR and Latin America cited in the data collected. The same inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied, and 102 records were added as a result of the supplementary search. See Fig. 1 for a summary of the data collection process.

Figure 1. Diagram of the data collection process

Coding Protocol and Analytical Criteria

A systematic qualitative analysis of all 309 works was conducted using NVivo, a computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software program.Footnote 16 An initial set of concrete analytical criteria was developed in order to scope and systematize the analysis. The first category of criteria encompasses metadata of the works: in what publications, where, and when they were published, how they are made accessible to the scholarly community, what disciplinary or methodological approaches are adopted, and who they were authored by (in terms of nationality, academic affiliation and gender). The second category encompasses qualities regarding the substantive content of the works: main themes, sectors, economic regimes, specific rights or social groups affected, and whether the work was grounded in a specific country context. A coding protocol according to the above-mentioned criteria was elaborated. See Table 4 for a summary of the analytical criteria.

Table 4. Analytical criteria

Limitations

Databases and Search Strings Constraints

A primary limitation of the study is that the dataset’s content has inevitably been limited by the boundaries of the three academic search engines used. In particular, one concern based on the breakdown of search results presented above is that works by Latin American authors may be significantly less visible in some of the most widely used engines.Footnote 17 While our search strategy was in line with the aims of the research, in that it is only works that are readily visible to international audiences through commonly used academic indexing services that can shape the broader BHR field,Footnote 18 it is a concern that merits mentioning.

As noted, the search strings selected, in particular, the term ‘Latin America’, might also orient the results to the exclusion of works referring exclusively to subregions or specific countries within the region. While this choice was deliberate, and in the interest of the manageability of the study, there is a risk that this approach privileges works that recognize a certain case explicitly as emblematic of Latin America – and which are more likely to be written from a perspective of a scholar looking outwards from the region and engaging in a conversation with an international audience and likely to privilege themes and approaches that are more transnational than local in nature. This perspective, while useful, misses a wealth of contributions produced by scholars across the region that are nationally and locally oriented. It is important to find ways to make such contributions a subject of further analyses, to learn from them, and to make them more visible to wider audiences.Footnote 19

It is also possible that our search strategy failed to capture works that engage with BHR concepts, problems or institutions but do not use the common terminology adopted in the field. Framing can often be an expression of access: scholars who on account of paywalls or linguistic barriers have limited access to recent literature are likely to try to articulate issues on their own, rather than rely on the vocabularies and theoretical frameworks that may already exist.Footnote 20 In the context of a study like ours, this might amplify the under-representation of scholars from certain parts of the region or socioeconomic backgrounds.

While we attempted to, at least partially, address these limitations through the targeted supplementary searches, it is important to note that our findings do not claim to be statistically representative of all BHR-LA scholarship published, nor was this the aim of this study. Despite its limitations, the systematic approach used for the data collection is considered the more accurate and reliable way of assessing the state of a given field.Footnote 21

Accessibility

Further, an important consideration was the accessibility of the full texts of the works included in the dataset. Of the 312 works originally selected, 230 were open (free) access, for 54 access was obtained via institutional subscription, and to 28 neither author had access. Five works were successfully suggested for purchase by the authors’ respective institutional libraries. Two of the texts were obtained by requesting access from the authors via ResearchGate and for the remainder, the respective authors were contacted by email to request access, which was received for 20 works. Finally, three records had to be excluded due to the lack of access. A total of 309 works was considered in this review.

IV. Findings

Metadata

Who publishes the research generated in the field, where it is published, and in what form, keeping in mind variables such as country of origin or language of publication, can be a potent window into the dynamics of the scholarly conversations taking place in a field. Considering the implications these characteristics may have for the BHR-LA academic discussions, in this subsection we address the key metadata statistics revealed through the database, concerning publication data, distribution over time, author origin and affiliation, author gender, and discipline and methodology. Where a book was an edited volume, we considered each chapter individually, whereas a book by a single author was considered as a whole.

Publication Types, Channels and Places

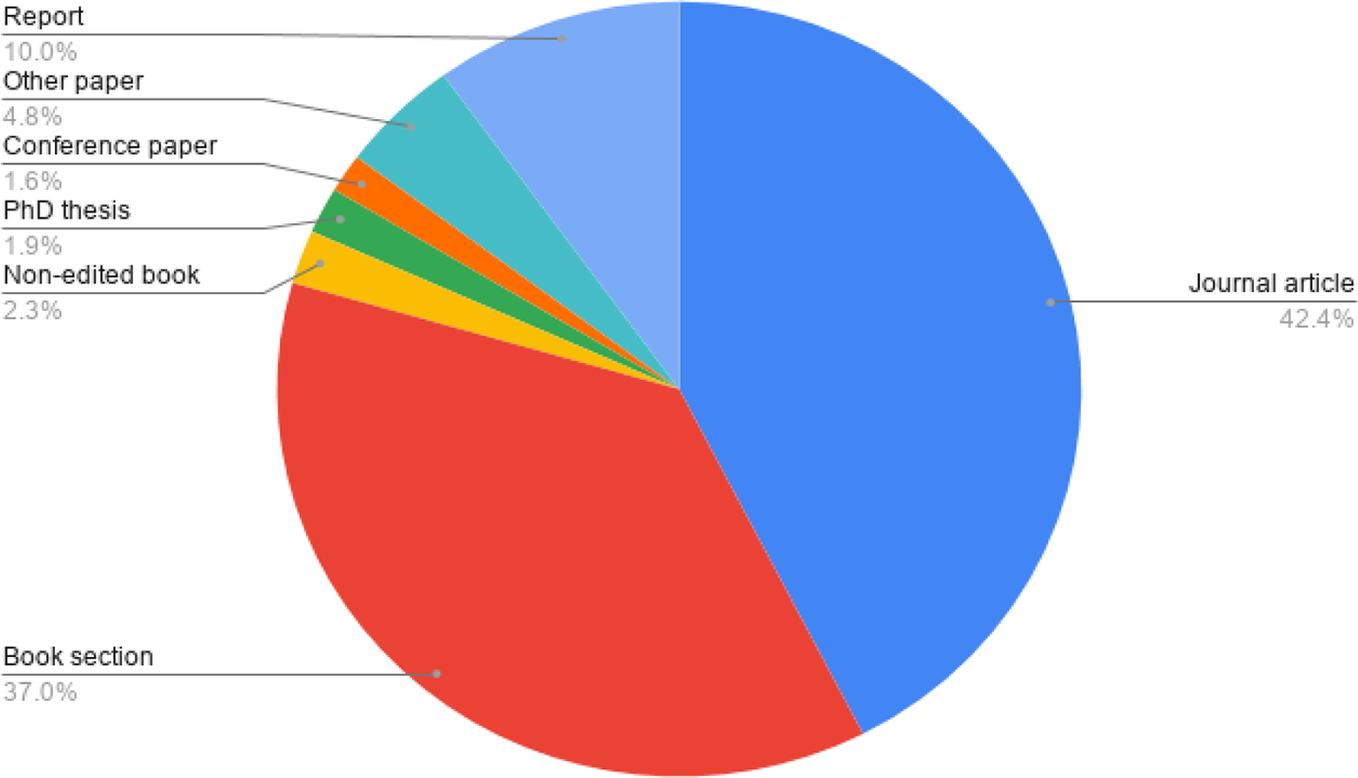

Of the 309 works identified for analysis, the vast majority fell into the category of either articles published in academic journals (132) or chapters in edited volumes (115) (see Fig. 2). The journals were almost uniformly double-blind peer-reviewed. Among the books, collective edited volumes were generally more prevalent than non-edited books on the subject. Both such edited volumes and special BHR-focused journal issues were typically oriented around ‘BHR’ in general, with a thematically and geographically diverse set of contributions rather than a strict thematic focus.

Figure 2. Publication types

While the English and Portuguese subsets traced closely the distribution described above, works published in Spanish were much more likely to be published as book chapters, rather than in journals.Footnote 22 A report published by an NGO or an academic department was also more common, with 19 out of all 30 such reports in the dataset published in Spanish. Differences could also be observed in the breakdown by author’s origin: nearly half of records by only Latin American authors were book chapters, a proportion well above these in the particularly non-Latin American and, to a lesser extent, mixed authorship categories. The comparison further provides insight on the nature of collaboration between authors from inside and outside the region, which disproportionately resulted in NGO reports, rather than co-authored contributions to peer-reviewed journals or books.

Of the 309 works, 171 were published in Latin America, 131 outside of the region – primarily in the US, UK and Spain – and seven could not be attributed.Footnote 23 The majority of the publishing activity in the region was focused within two countries: Brazil with 83 records and Colombia with 38. In only eight of the 17 Latin American countries in our study was at least one work published. In addition to this disparity in publication activity across the region, another trend merits mentioning. The majority of the works by authors from the region (147 out of 205) were published by Latin American publishers; an even larger majority of works by non-Latin American authors (55 out of 66) were published in the Global North. This suggests two inter-related trends: on the one hand, the fairly rigid publishing tendencies suggest that the scholarly exchange between Latin American and non-Latin American authors focusing on BHR topics in the region is not as fluid as it could be. For a subfield with both a regional focus and strong links to ongoing global conversations in the wider BHR field, that is a worrying statistic. On the other hand, there is a clear tendency for Latin American scholars to contribute disproportionately more to Global North outlets than is the case in reverse.

Worth noting, moreover, are the differences in academic publishing trends between Latin America and the countries from the Global North in which works in our dataset were published. While Latin American publications are typically produced by individual university departments, in many of the key publishing countries from outside of the region, the publishing industry is dominated by large commercial publishing conglomerates. This model of scholarship dissemination contributes to the disparity in accessibility and affordability of scholarship.Footnote 24

The degree to which given works are accessible (and to whom they are accessible) is a necessary consideration in discussing the dynamics of scholarship creation and exchange in the field. As explained in ‘Limitations’ in Section III, the authors were able to obtain free access to a majority (74 per cent) of all works in the final dataset, we relied on institutional subscription for access to 18 per cent and were able to successfully contact respective authors for access in 8 per cent of cases. That said, the degree of access differed notably by language in which the work was published: 50 per cent for English, compared with 94 per cent for Spanish, and 84 per cent for Portuguese. Institutional access was not required for virtually any of the works in Spanish or Portuguese, while 40 per cent of those in English were paywall-protected. A similar difference between works by Latin American and non-Latin American scholars was, while present, less pronounced, suggesting that the accessibility is instead related to the kind of outlet in which it is published (Global North vs Latin American). This difference, naturally, is not without effect on the BHR field in the region. This is particularly as regards the degree of access that Latin America-based scholars and students have to the conversation on the subject taking place globally, and especially to the arguments and analyses produced by Global North academics, who are more likely to publish in these English-language channels, as observed earlier. Furthermore, while many journals and books published in Latin America were tri-lingual (that is, one publication either contained a mix of contributions in English, Spanish and Portuguese, or had each contribution translated into all three), similar efforts were not found in Global North publications, even if they focused on the region in substance.Footnote 25

Distribution Over Time

While some works began to appear on BHR in the Latin American context from the beginning of the development of the field in the early 2000s, it was not until 2010, and then 2012, that rapid growth of this sub-field was observed, suggesting that the conceptualization of the UN Framework and the adoption of the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) has given impetus to focus on the subject in the region. Whereas these earliest, pre-2011 works were written almost exclusively by authors from outside the region and in English, in the late 2000s first records in Spanish (by Colombian authors), and then in 2011 in Portuguese, appear. The twofold increase from the year 2014 to 2015 can be attributed to the beginning of a ‘boom’ in Brazilian BHR scholarship, which has accounted for the large proportion of the publication numbers since. Notably, the representation of different parts of the region (discussed in more detail below in the ‘Geographical Metadata’ subsection), seems to be also on an upward trend: nearly all works by authors from countries for which there were seven or less records were published just in the last three years (2018–2020). See Fig. 3 for a summary of volume of publications over time.Footnote 26

Figure 3. Volume of publications over time

Geographical Metadata – Authors’ Origins, Affiliations and Gender

Of the 309 positions in our database, 205 were works by one or more authors from Latin America, 66 by one or more authors from outside of Latin America, and 31 were co-authored by a Latin American author(s) and a non-Latin American author(s). Among Latin American authors, including co-authored works, apparent is the high concentration of scholarship in a handful of countries in the region, as displayed in Fig. 4. Central America as a sub-region has been particularly under-represented in this regard.

Figure 4. Authors’ country of origin and institutional affiliation

Most Latin American authors (182 out of 246 works), were affiliated with an institution based in their country of origin; this was particularly the case for Brazil. Further, 52 were affiliated with an academic institution outside of the region (all in the Global North countries), 11 with one in another Latin American country, and four with an international or regional organization. On the other hand, the vast majority of authors from outside of Latin America who produced scholarship about the region were not based in a Latin American country (only four authors, responsible for nine works, were an exception).

Some thematic trends appear to be associated with specific countries of origin or affiliation. For instance, children’s rights in the context of BHR has been a topic of great interest and a subject of robust scholarly debate in the Brazilian academia, yet virtually absent elsewhere. Similarly, some recognizable trends in BHR-LA literature can be traced primarily to the work of academics in (or about) a single country. Such is the case with the study of BHR in the conflict setting (Colombia), and BHR and Transitional Justice (TJ) (Argentina and Chile). As regards the breakdown of authorship by gender, 41.7 per cent of works were authored by women, 35.9 per cent by men, 21.4 per cent by both women and men, and 1 per cent could not be attributed.Footnote 27

Discipline

The findings from our database suggest that BHR-LA is, much like the broader BHR field, largely dominated by legal approaches (227 of the 309 works).Footnote 28 Of the remainder, 17 were in the social sciences,Footnote 29 31 interdisciplinary, eight in other fields, and in 26 cases a clearly defined disciplinary approach could not be identified. The interdisciplinary works, for the most part, supplemented a legal approach with another discipline, predominantly social sciences or public policy, but individual contributions from law and bioethics, business management, and theology were also found. The works in the ‘others’ category centred business-management and administration approaches; one contribution was in the field of critical pedagogy. In all three categories of non-legal works, non-Latin American authors were predominant.

Methodology

Of the 309 works, only 130 made at least a brief mention of the methodology used. This suggests, as further results seem to confirm, that the legal origins of the field continue to shape not only the theoretical approaches but also how the knowledge is produced in the BHR-LA scholarshipFootnote 30 – and what kinds of knowledge are produced as a result; 175 of the works were either purely or primarily conceptual in nature, relying on legal analysis or making a theoretical or policy argument about already-known empirical realities. Documentary analysis – including analysis or close reading of legal or policy documents and judicial decisions – was further relied on in 108 works, a review of secondary literature in 72 works, and other qualitative methods, such as interviews, ethnographic research, and observation, in 56 works. In addition, two texts involved participative research with members of affected communities, and 11 made a broad reference to ‘field work’ or a ‘research visit’, suggesting a qualitative approach but not providing details about methods used. There seems to be a clear tendency for authors to use in-depth case studies (65 works). Frequently, authors employed a mix of methodological approaches, for instance supporting a conceptual insight with an analysis of primary legal documents. Quantitative and empirical approaches were few. Quantitative methodology was used in seven works, of which five were written by an overlapping set of authors; in all but one instance, the method used was descriptive statistics based on a largely qualitative dataset. Six empirical works could be identified, of which three overlapped with the above.

Substantive

The analysis of our database further provided insights on the substantive qualities of the works analysed. We coded all texts for recurring themes, instruments, specific rights, specific affected groups, sectors, and country contexts focused on.

Thematic Focus

A few insights are worth highlighting regarding the thematic trends in the BHR-LA literature. First of all, a significant proportion of texts (86) focused on the UNGPs, either describing or discussing their content, or using them as an analytical tool applied to specific cases or contexts. When mentions are included, the number reaches an overwhelming 239 out of the 309 works. The ongoing debate around a potential BHR treaty has been the subject of 32 works, some evaluating drafting developments and describing ongoing negotiations, some addressing the matter conceptually, and some arguing for the necessity of a binding instrument on the basis of a case study. Finally, the Inter-American Human Rights System standards, which have traditionally played a crucial role in the advancement of human rights in the region, were frequently referred to in the literature and were the primary subject of 39 texts. See Fig. 5 for a summary of instruments.

Figure 5. Instruments

Possibilities for corporate accountability for human rights abuses and access to justice appear to be a central feature of the BHR-LA literature. As regards the type of accountability focused on, or advocated, by authors, a similar number of works focused on judicial recourse in the country where abuses had been committed (these most often analysed specific cases) and on judicial accountability in the company’s home state (see Fig. 6). In connection with the latter, the question of extraterritorial obligations of corporations’ home states has been highly discussed (mentioned in 47 works), a debate that has also received significant attention by BHR doctrine in general. The common law doctrine of forum non conveniens was frequently addressed (36 texts) and referred to as one of the most significant obstacles in the access to judicial resources in home States. A clear split can be observed on the matter between Latin American and non-Latin American authors. While authors from the region tended to focus on judicial accountability before host state courts or the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACtHR), non-Latin American authors typically advocated solutions in the home state – generally, in the country where the given author was based.

Figure 6. Type of accountability focused on or advocated

With regard to the type of legal responsibility discussed, regardless of the type of venue, we identified 23 papers addressing issues related to criminal responsibility, of which nine focused on international criminal responsibility, and 34 discussed civil liability, including one that deals with its implication in the sphere of international private law. Non-judicial state-based remedies attracted much less attention to date.

In the realm of conceptual debates (see Fig. 7), 42 works were dedicated to discussions of the possibility for direct corporate human rights obligations under international law; 23 works in turn focused on state responsibility for corporate violations on their territory and 18 on extraterritorial responsibility. Due diligence and the concept of the sphere of influence were discussed in 27 and three works, respectively. Twenty-eight, particularly earlier, works posited BHR approaches in relation to CSR (typically advocating the former as a more effective ‘step forward’).

Figure 7. Concept-oriented works

A few further interesting themes specific to the Latin American context emerged from the analysis. The problematizing of BHR issues in the context of internal armed conflict (Colombia, Guatemala), an economically liberal dictatorship (Argentina, Chile), or transitional justice processes (Argentina, Chile, Colombia) has been an important subject in the scholarly debate in the region and the main focus of 24 texts. In the past couple of years, another region-specific theme has begun to gain ground in the scholarship – the idea of a Latin American ius constitutionale commune in human rights (ICCAL) as a potential avenue to safeguard rights from business-related violations has been a focus of three works in 2019.

Sectors and Economic Regimes

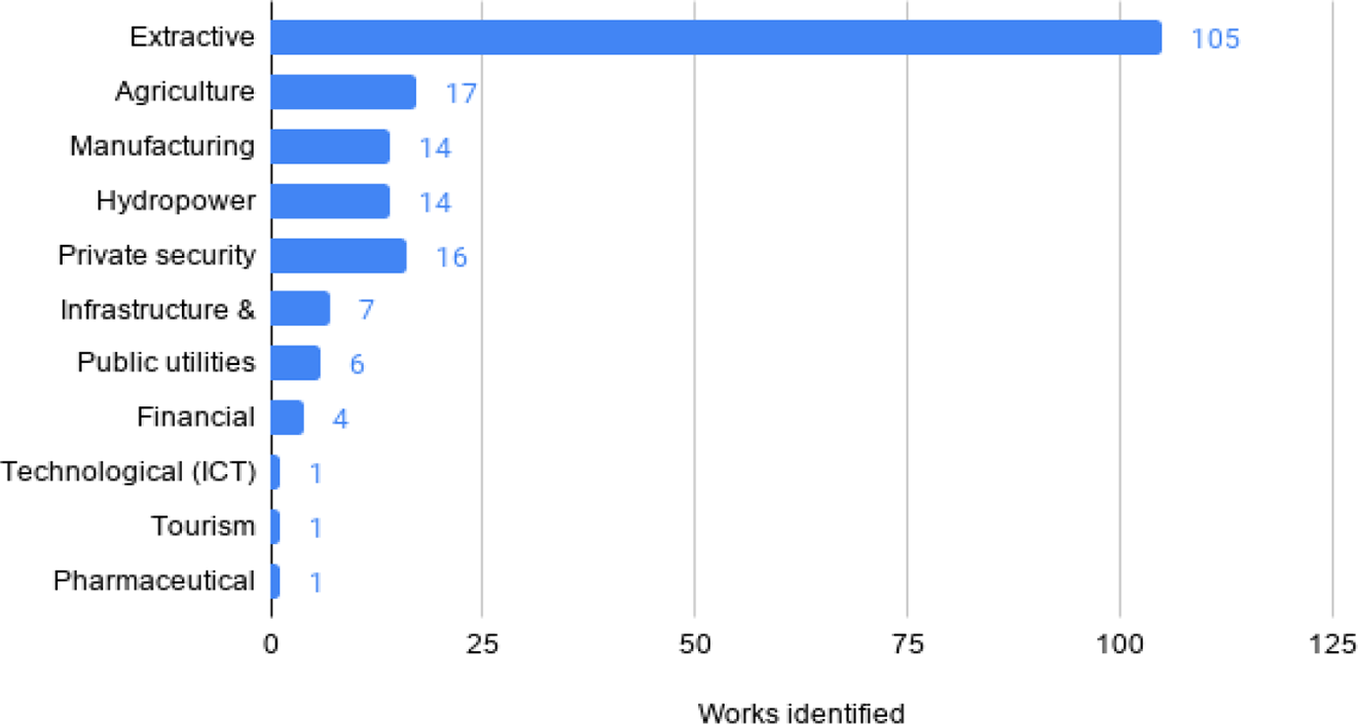

The centrality of the extractive sector in the regional debates on BHR in Latin America is reflected in the data collected (see Fig. 8); it is the focus of 105 out of 309, or over one-third of texts in our database. Of these, 21 per cent address the presence or impact of extractive activities from a human rights perspective in the region generally, 6 per cent focus on the sector’s impact on Indigenous peoples’ rights, and 6 per cent address the relation between extractive and another sector, for example, private security. The remainder (56 per cent) of this subset of texts focuses on a specific project or a specific country context. Further, 17 records focused on the agricultural sector, including animal farming (of which five focused on agrochemicals), 16 on private security, 14 on hydropower, 14 on manufacturing (including the textile sector), seven on infrastructure and construction, six on public utilities, and four on the financial sector (mostly in relation to financial complicity with the Argentine dictatorship). Individual records further focused on technology, tourism and pharmaceutical industries.

Figure 8. Sectors

A portion of the works in our database focused on the role of specific economic regimes governing international investment and trade in facilitating, preventing or shaping the remedy possibilities for human rights abuses by business. Seventeen records focused on, or substantially engaged with, the topic of international investment and investment arbitration, of which six were conceptual discussions of the interaction between international investment law and international human rights law, and four assessed the arbitral resolution in a specific case study. Of the 14 works on international trade, nine discussed the human rights dimensions of a specific Free-Trade Agreement (two records each about the Canada–Colombia, European Union–Mercosur, and European Union–Mexico Free Trade Agreements (FTAs), and one each about the United States–Colombia Trade Promotion Agreement, the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement, and the North American FTA), and one focused on the World Trade Organization (WTO) Dispute Settlement procedure. Interestingly, the international investment regime and investor-state arbitration has been a topic of interest particularly to Latin American authors, while international trade has been treated primarily by non-Latin American scholars.

Rights Categories and Affected Rights-Holders

Our data further demonstrate which specific rights are of greatest interest in the BHR-LA literature. Here, a large number of the records (66) had as their main focus the rights of Indigenous populations (all but a few on consultation and consent rights). In the case of a few rights categories, the volume of mentions of specific rights violations was incommensurate with the degree of scholarly focus on these rights. For instance, only six records focused on the right to life violations and none on physical integrity violations, but many more dealt with cases that involved killings and physical integrity violations without applying to them a specific rights framework. Similarly, while state criminalization of dissent in the context of the so-called development projects has been a consistently recurring theme in the literature, only 10 texts explicitly addressed related civil and political rights such as access to information and political participation (8) and the right to protest (2). This was also the case for environmental rights – while 42 texts had environmental concerns at their core, of these only 13 considered them using a human rights logic. No text addressed explicitly the right not to be displaced, despite 50 texts focusing on situations where displacement has been named as one of the dominant impacts on the affected population. See Fig. 9 for a summary of rights.

Figure 9. Rights

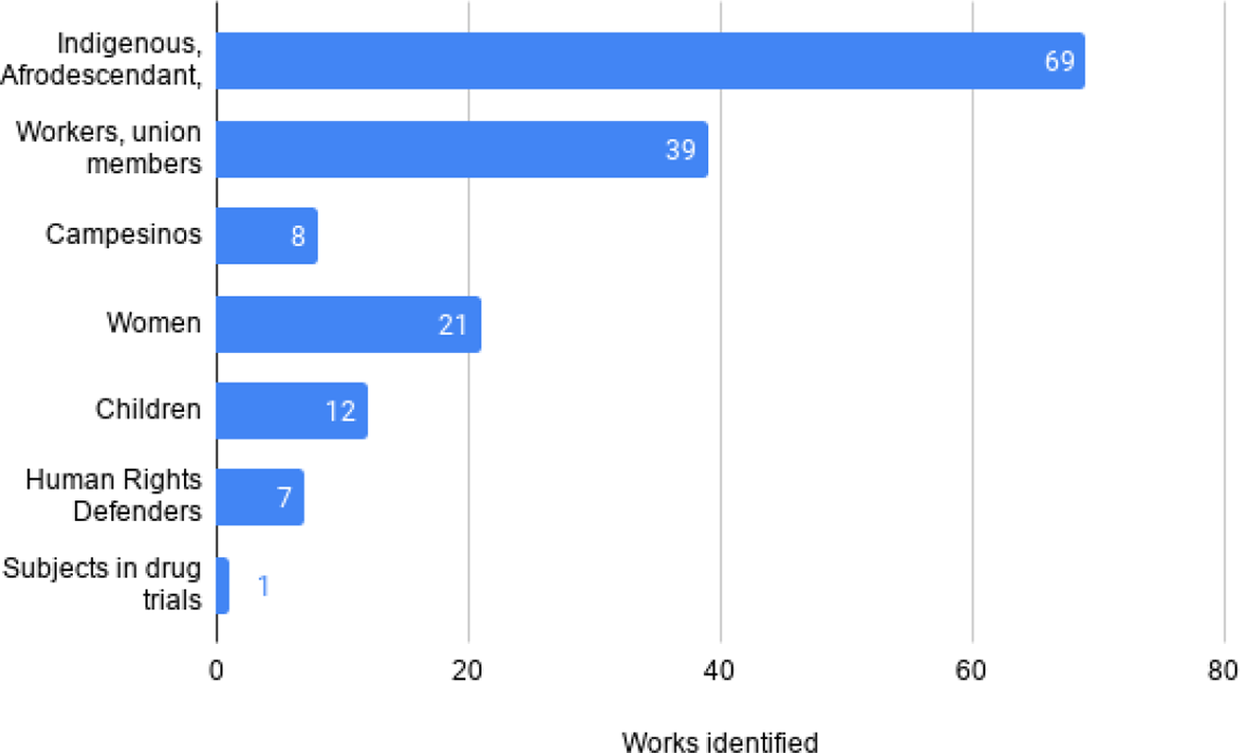

In addition, mentions of specific social groups affected by the violations studied were coded (see Fig. 10). Most written about (69) were cases involving Indigenous, Afro-descendant or other non-European-descendent ethnic groups. Our data also suggest a nascent interest in the gendered impacts of rights violations linked to business activities: 21 records explicitly named women as an affected population in the case studied, and 33 involved mentions of sexual violence.

Figure 10. Affected rights-holders

Geographical Focus

We further coded and analysed the database for the geographical distribution of case studies and country contexts described (see Table 5). In general, the data reveal the tendency of the BHR-LA literature to concentrate predominantly on a few countries in the region: Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, Guatemala, Argentina and Chile. Four of the 17 countries included in the analysis were not addressed in a single work, and five were addressed in only a single work each; 76 of the 309 works adopted a general regional approach, discussing an issue in the broader context of the Latin American region.

Table 5. Geographical focus

Regarding home states, Canada – and in particular Canadian mining investments in Indigenous peoples’ lands in Latin America – has received significant attention in the literature (27 works). A further 32 records name the US as a home state, and 31 focus on different European states. While both US and European companies appeared in the literature as violators marginally more frequently than Canadian companies, only in Canadian scholarship did there seem to be a more robust, sustained discussion on the impacts of these companies and the possibilities for keeping them accountable under home state legislation. With some exceptions, there seems to be less interest in the subject in US and European scholarly debates. While the rise in Chinese investment in the region is mentioned frequently across the literature, our review did not yield a single work focused on China as a home state.

V. Discussion

Latin American Contributions to the BHR Field

When mentioned in passing in the general BHR literature, this region is typically portrayed as a non-descript site of abuse, a place where human rights abuses committed by or associated with businesses occur. As such, it functions as a source of evidence to argue for the necessity of preventing those abuses and ensuring justice for victims. However, a closer analysis of the region’s place and role in the BHR scholarship, as was the goal of this study, paints a more nuanced picture.

On the one hand, specific features of the Latin American regional context have provided grounds to push the BHR field into new directions thematically. On the other hand, reflections about these new subjects, or more broadly reflections on BHR by Latin American authors have contributed significantly to the ways in which certain concepts in the BHR field are understood, and they have also served as a basis for arguing for the need for advancing specific modes of regulation and mechanisms related to business and human rights.Footnote 31 Four main domains appear as central in discussions in the BHR-LA literature: the impact of extractive activities on Indigenous rights, BHR in the context of transitions following armed conflict or dictatorship, the emphasis on judicial accountability, and the role of the Inter-American System.Footnote 32

Extractive Activities and Indigenous People

The implications of extractive activities for the rights of Indigenous and Afro-descendant people has been one of the most frequently addressed human rights issues in the regional BHR literature. The continent’s cultural diversity, a large share of Indigenous populations in the Latin American societies,Footnote 33 and the existence of legal frameworks recognizing their collective rights, along with the dependency of much of the region on foreign direct investment in the extractive and raw materials sector, have converged to produce common scenarios of asymmetric relations between the private sector and these communities.Footnote 34 These scenarios have in turn paved the way for rich literature in the wider BHR field on the business impacts on Indigenous rights, particularly with regard to the tensions between preserving Indigenous territories and lands, and large-scale extractive or development projects. It is worth noting that in conceptualizing the business impacts on Indigenous rights even pre-UNGPs, Ruggie relied almost exclusively on Latin American examples.Footnote 35

To date, much of the literature examined as part of our project focused on the right to free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) as it relates to BHR. Indeed, in Latin America few rights recognized in international and regional instruments have received as much attention as the FPIC. In a region characterized by its cultural diversity and high levels of social conflicts regarding extractive and development projects, FPIC has been frequently understood by State authorities, private companies and academia, as a tool for conflict prevention and resolution:Footnote 36 its content, development, and its breaches in said scenarios of asymmetric relations,Footnote 37 of which several contributions focus on assessing the state of play in a specific country context.Footnote 38 Likewise, the FPIC has been at the core of the struggles and strategies of Indigenous organizations for resisting such initiatives and halting their overwhelming impacts over traditional lands.

At the same time, the debates on the implementation of this right have largely taken place in Latin America, considering that 14 out of the 23 State parties of the ILO 169 Convention (the only conventional instrument in this regard) are countries from that region.Footnote 39 Moreover, the detailed standards developed by the Inter-American Human Rights System have been of strong influence in the understanding of this right, and might be considered one of its most valuable contributions to the international human rights law in general.Footnote 40 The importance of this regional human rights system is also apparent in our research as several works are focused on the Inter-American standards on the right to FPIC.Footnote 41

Furthermore, among the recent contributions, several works attempt to go beyond this traditional consultation paradigm in literature. Del Castillo, for instance, highlights the contributions by Indigenous Peoples to the establishment of the framework for the protection of their collective rights, thus emphasizing the often overlooked aspect of victim agency,Footnote 42 while León Moreta analyses the impact of using a benefit sharing scheme as compensation for damages caused in Indigenous territory.Footnote 43 It is finally worth noting that the rich literature on the subject in the Latin American context has invited discussions of broader relevance to the field beyond Indigenous rights, such as on environmental rights and the standards for FPIC of communities affected by development projects more broadly.Footnote 44

BHR in the Context of Conflict, Dictatorial Regimes and Transitional Justice

The second area concerns accountability for corporate human rights abuses in contexts of dictatorships and internal armed conflicts, which were marked in the region particularly between 1970 and 1990.Footnote 45 While business involvement in conflict-related rights violations, particularly in the minerals sector, has been highlighted in the BHR field since the beginning, a uniquely Latin American contribution is a focus on possibilities for post facto accountability for such violations as well as their inclusion in broader transitional justice (TJ) processes. Discussions related to the role of economic actors in these contexts have led to pioneer discussions on corporate complicity and transitional justice, in which, as has been pointed out, ‘Latin America has taken the lead’.Footnote 46 An empirical study on the inclusion of corporate accountability in TJ processes to date further finds a ‘clear Latin American protagonism’, as 60% of all legal actions concerning economic actors in TJ globally were brought in the region, and the largest number of truth commissions to include economic actors have taken place in Latin America.Footnote 47

The reasons for this protagonism go beyond Latin America’s well-documented role in the advances in TJ in general.Footnote 48 Payne, Pereira and Bernal-Bermúdez point out that the region’s recent history was marked by collaboration between political elites and economic actors that ‘violently consolidated and reproduced socioeconomic inequalities during authoritarian governments and armed conflicts’; in these contexts, economic actors played a prominent role in state repression both in terms of ideological convergence and in ‘financing, instigating, committing, perpetuating, and knowingly profiting from, the violence’.Footnote 49

It is […] part of the argument about the rise of repressive bureaucratic authoritarian states of Latin America in the 1970s and 1980s, an approach subsequently applied to other world regions. Guillermo O’Donnell emphasized the alliance among the military, technocrats, and business that produced those violent regimes. During the Cold War, and at a key developmental phase in the most economically advanced countries of the Global South, businesses and technocrats perceived authoritarian systems as the best way to advance and protect ‘capitalist deepening’ projects. Successive coups, and the national security regimes they implanted, aimed at stemming the tide of Communism and strengthening capitalism through wage repression and violence against those labeled ‘subversives’. Nonetheless, business support provided an important degree of legitimacy, funding, and collaboration that sustained these regimes and their violence. Footnote 50

The role of these convergences between macroeconomic policy and repression in generating conceptual advancements in the BHR field is particularly pronounced with regard to the scholarship on the role of economic actors in the dictatorships of the Southern Cone,Footnote 51 generally Argentina and Chile. In the case of both regimes, a unique and defining feature was the central role that economic policy played in their goals and survival, including the orientation towards foreign investments and large influxes of financial aid provided by the US and foreign and international financial institutions.Footnote 52 These economic scenarios and their intimate relationship with violations of civil and political rights by the regime provided fertile ground, and indeed an impetus, for the theorization of the concept of financial complicity in state-sponsored repression. The so-called Cassesse Report, a 260-page report by Professor Antonio Cassesse appointed in 1977 by the UN Commission on Human Rights as a Special Rapporteur to assess the link between the financial aid received by the Pinochet regime and the human rights violations it perpetrated, in developing a sophisticated methodology to empirically evaluate the impact of financial aid on human rights conductFootnote 53 has become seminal. Similarly, subsequent scholarship, including that in our database,Footnote 54 has relied on case studies of the Southern Cone to produce both new empirical analyses of the impact of financial support in facilitating abuses and to nourish the conceptualization of financial complicity. It is worth noting that this is not merely a theoretical exercise, but one that can open the door to greater scrutiny – and eventually accountability – around the role of Global North-based financial actors and governments in facilitating human rights abuses by repressive regimes in the Global South.

The other dominant strand of literature has grown out of the Colombian experience with the role of economic actors in its decades-long civil armed conflict. As the authors of the Corporate Accountability and Transitional Justice database (CATJ) show, Colombia is a virtually uncontested leader in terms of the number of judicial actions initiated against economic actors as part of its TJ process.Footnote 55 Further, the information on involvement of hundreds of economic actors in abuses perpetrated by paramilitary groups, collected as part of the Justice and Peace process initiated in 2005,Footnote 56 has provided an unprecedented volume of material to analyse the dynamics of such involvement. Other aspects of the Colombian experience may also be of relevance to scholars elsewhere: Bernal Bermúdez, for instance, studies the outcome of the tension between pressures for prosecution and a dependence on the revenue streams from large business in post-conflict states,Footnote 57 while Payne and Pereira point to Colombian cases for insights on how prosecutors can overcome barriers to accountability in post-conflict contexts.Footnote 58

Finally, authors in this vein of literature have also engaged with, and contributed to, the ongoing debate around the efficacy and role of different BHR instruments, with Payne and colleagues considering how a BHR treaty could advance the rights to truth, justice and reparations.Footnote 59

Judicial Accountability

The necessity for binding, judicially enforceable approaches to corporate accountability has been a central feature of the BHR-LA scholarship. In contrast with the frequently relied-on discourse of ‘sustainable development’ and the normative power of non-binding UN solutions for corporate behaviour, authors in our database focused extensively on specific possibilities for legal recourse (as seen in ‘Thematic Focus’ in Section IV), their viability, and obstacles present. If the emphasis on judicial accountability is evident from the thematic orientation of the works, it is also often explicitly argued for: for instance, in cautioning against over-reliance on NAPs and other non-binding policy instruments.Footnote 60

A significant number of academic efforts in this area have also dealt with questions related to the pursuit of legal recourse by victims in light of obstacles and widespread situations of impunity. Some of the region’s most emblematic cases such as the Texaco-Chevron case in EcuadorFootnote 61 have provided fertile ground for assessing, in the context of a single case, the challenges of accessing justice before several different types of judicial venues. Martin-Chenut and Perruso, for example, trace the ‘politico-jurisdictional saga’ of victims’ attempts to access remedy in the Texaco-Chevron case as one in which challenges they encountered over the course of decades before different jurisdictions are not only emblematic of the respective venues but also interlink in ways that makes access to justice for corporate abuses in transnational context near-impossible. Specifically, the authors point to the determination of forum non conveniens in a US court illustrating the existence of legal tools that disfavour a determination of liability in the home state, followed by a positive decision before an Ecuadorian court that was nevertheless marred in due process concerns, and finally the impossibility to execute the judgement in Ecuador due to the company not holding enough assets in the country and the subsequent unsuccessful struggle to execute the judgement against its assets in the US – a struggle somewhat kafkaesquean as it hinged on the perceived lack of validity of the decision made by the court in Ecuador and thus the very venue that had implicitly been deemed adequate in the first US case.Footnote 62

Other authors have built on such analyses to push the field in new directions. Guamán Hernández, for instance, relies on the Texaco-Chevron case as a paradigm of the current impossibility of justice across available venues to argue a necessity of adopting a binding BHR treaty.Footnote 63 Woods, similarly, points to the Peruvian state’s failures to adequately act in the Minas Conga case to highlight the flawed incentives that states pursuing a neoliberal development model may need to navigate and, consequently, to propose an introduction of direct binding human rights obligations on companies as necessary to protect human rights in contexts where states cannot uphold their duty to protect from transnational businesses’ human rights transgressions.Footnote 64

Latin American authors have in recent years also played an important role in bringing attention to domestic courts in countries in which abuses had taken place. For instance, Bernal-Bermudez uses data on judicial action in Colombia as a case study to explore patterns in the use and efficacy of judicial remedy mechanisms in addressing corporate involvement in human rights violations. In this study, the empirical analysis of data from Colombian courts served to help theorize factors influencing judicial outcomes in corporate accountability cases, with implications beyond the Colombian context, but also evidenced the need to question the ‘adequacy of continuing to rely on the state and the companies to implement the […] access to remedy’ in light of the ‘significant proportion of cases where the state and the company have colluded in the perpetration of the abuse’.Footnote 65 In another example, Cantú Rivera analyses the understanding of corporate responsibility to respect that emerges out of recent Mexican case law, highlighting that such ‘development of case law on the horizontal application of human rights to corporate activities […] directly contribute to the solidification of standards that are intrinsically compatible with the spirit of the UNGPs’. Footnote 66 As Cantú Rivera notes, Latin American cases have ‘paved the way for interesting judicial decisions that may at least partially reflect the position of developing countries in relation to the respect of human rights by economic actors’.Footnote 67

Regional Human Rights Governance and BHR: the Inter-American Human Rights System

The fourth domain is the prominence of the Inter-American System (IAHRS) in the regional discussions on BHR. From the pioneering texts in the field, the traditionally robust standards of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACtHR) seem to have provided more content and richness to the discussions beyond the non-binding UN instruments and the typically limited national legal frameworks. Given that both organs have dealt with cases concerning BHR aspects long before the adoption of the UNGPs in 2011, their decisions and jurisprudence have represented a starting point for analysing BHR-related issues in the region.

Some examples include general State duties in relation to non-state actors, extraterritorial obligations,Footnote 68 and the concept of due diligence,Footnote 69 as well as numerous cases on Indigenous peoples with express references to corporate conduct endangering rights.Footnote 70 Some authors, especially in the early years following the adoption of the UNGPs, focused on elaborating on the relevance of the Inter-American System’s engagement with BHR key concepts – the question of why. Building on the inter-American human rights system’s prior decisions, for instance, Woods argues that ‘not only is the promotion of the Guiding Principles squarely within the Inter-American Commission’s mandate, but also that the Commission is well-versed in issues of business and human rights’.Footnote 71 More recently, other authors have tried to conceptualize how to integrate BHR and IAHRS standards. De Casas, for example, has done so by bringing together the corporate responsibility to respect human rights and the Inter-American standards on the right to consultation. Based on that, he suggests ways in which the organs of the Inter-American system ‘can help to promote a direct corporate responsibility to respect FPIC’.Footnote 72

The enormous influence of the IAHRS is also seen in its centrality for the reflections of BHR regional perspectives, such as those related to an ius constitutionale commune (a concept of ‘common constitutional law’, ICCAL) in human rights in Latin America.Footnote 73 Danielle Pamplona, for instance, affirms that this doctrinal tradition can provide a common rationale to reduce the lack of coordination among Latin America countries in the BHR field. She further argues that ICCAL can serve ‘as a basis for the adoption of a new posture by global south countries regarding regulation of investors’ economic activities’.Footnote 74 Beyond Latin America, the unique position of the IAHRS in the region has provided a basis for a broader discussion on regional mechanisms and regionalization in BHR. Examples from our database include the work of Humberto Cantú Rivera in ‘defining a Latin American route to corporate responsibility’ through the analysis of the developments in the region on corporate responsibility, as well as of the positions of Latin American States in the Intergovernmental Working Group on the elaboration of a binding international instrument on human rights and transnational corporations.Footnote 75

The Present Situation of the Field: Between Expansion and Specification

While the specific trends in the literature to date will be evident from the findings in the ‘Substantive’ subsection of Section IV, two general patterns merit mentioning. Firstly, the expansion of the BHR field associated with the adoption of the UNGPs seems particularly apparent in the Latin American region. More than 90 per cent of all works were published just in the last ten years (i.e., after the UNGPs were adopted); in addition, nearly one-third of all works focus specifically on the UNGPs, exploring their potential to address BHR problems, particularly in specific cases. This suggests that for many scholars in the region addressing BHR issues has to some extent been equivalent to engaging with this instrument. This conceptualization might have the effect of narrowing the discussions to the frame of the UNGPs, leaving aside broader views on the human rights implications of business enterprises that are beyond the current UN framework.Footnote 76

Secondly, the subfield is currently experiencing a move from general to specific approaches. This specification of BHR research in Latin-America appears to be based on, at least, four thematic analytic variables that inter-relate with one another: (1) specific human rights and human rights-related problems; (2) industry or sector-based specification; (3) the need for special protection of individuals and groups historically discriminated against or in a particularly vulnerable situation; and (4) specific contexts (i.e., armed conflict, transitional justice or a specific home/host country). Expressions of these developments can also be seen to some extent in the broader BHR field. This process of specification in the region can be further shaped by specific characteristics of country contexts or the development of robust discussion circuits at the national level, which generate thematically unique contributions to the broader BHR debate. One case in point is the growing focus on children’s rights and BHR in Brazilian scholarship (see ‘Geographical Metadata’ in Section IV),Footnote 77 as it remains one of very few treatments of this topic in BHR literature generally.

Gaps and Directions for Further Research

Finally, the findings of the review suggest several key gaps in the BHR-LA literature, based on which this subsection proposes directions for further research in the field.

Intra-Regional Representation

The BHR field has over the past decade forged a robust scholarly community in Latin America. However, both research and publication activity, as well as the choice of subject matter, focus heavily within a few, generally the most economically prosperous, countries in the region.Footnote 78 As a result, the scholarship produced tends to represent only a sliver of the vast diversity of relevant contexts. This has implications beyond questions of representation itself – the thematic trends in the scholarship further suggest that the limited national diversity is impacting the scope of the discussion in the field. For instance, while tourism accounts for a fairly low share of the GDP in the region on average, it is key in the economies of Central American states,Footnote 79 which have been most under-represented in the regional debates to date. As a result, this sector of prime relevance has not received much scholarly attention. The same is true for the textile industry – while it was found to account for one of the largest numbers of violations in the region,Footnote 80 its treatment in the literature has thus far been scant, possibly due to the fact that manufacturing, and textile specifically, accounts for a generally lower share of the economy in the countries that are represented.Footnote 81 Therefore, not only is a limited set of perspectives heard in the BHR-LA scholarship, but the underlying inequalities – among countries in the region, but likely analogically within each of them – may hamper the scholarly understanding of the BHR problematics in certain contexts, to the detriment of the broader field.

Worth noting is that representation of different country contexts in Latin America is greater in substance than among the scholars who produce the scholarship. Emblematic here is the example of Guatemala, which has been a source of paradigmatic cases in the field and one of the most focused-on country contexts (particularly by non-Latin American authors) even as Guatemalan authors have been virtually absent from the conversation. This suggests that at the core of these under-representations is not a lack of relevance of BHR in a given context, but of limited and uneven access to the resources necessary to participate in a scholarly conversation across the region.

Methodology and Discipline

The range of methodological approaches used in a field is crucial to what kinds of knowledge are produced. To date, conceptual debates, particularly with regard to the place of BHR across different forms of responsibility under international law, have been at the forefront of the BHR-LA scholarship, as have close analyses of key documentary sources (international and national normative frameworks, judicial decisions, and stated company positions) and several landmark empirical cases such as the rights abuses generated by the Marlin Mine,Footnote 82 the Samarco disaster,Footnote 83 the Belo Monte dam,Footnote 84 or the Chevron-Ecuador caseFootnote 85 presented as emblematic to the challenges in the region.

Despite the field’s immense potential for methodologically diverse and cross-disciplinary approaches, this range of methods used remains limited, however. Our data suggest that systematic approaches to methodology are generally scant; instead, works tend to be more descriptive and conceptual in nature. That is consistent with the tendency in the BHR field more generally and understandable given the field’s orientation towards legal scholarship, which tends to be based on rigorous conceptual analysis, rather than on systematic collection and analysis of data.Footnote 86 However, new approaches could help generate important insights relevant for making the conceptual and normative ideas in the literature better actionable. For instance, expanding a range of methodological approaches used to include more empirical research methods, quantitative analysis, and systematic studies could enhance the understanding of the empirical dynamics of business-related rights violations on the ground, as well as help assess the efficacy of different approaches to regulation or remedy. The first attempts to introduce systematic, including empirical, methodologies illustrate the value such diversification can bring to the field.Footnote 87

Expanding the range of methods used to study BHR in the Latin American context would also facilitate expanding the level of analysis. Currently, the methods predominantly used lend themselves best to the use of specific case studies, either in order to illustrate a conceptual point or for qualitative in-depth analysis. Expanding would make possible gathering insights from comprehensive studies at the regional, national or sub-national level, uncovering patterns in violations, remedy, and other variables on which little systematic data exist to date.Footnote 88 Overall, for reasons described above, there is ample potential for both expanding the range of methods used in legal scholarship (e.g., empirical legal studies), and for fruitful interdisciplinary cooperation in the field between legal BHR scholars and scholars working on BHR issues in other disciplines (such as public management, social sciences, anthropology, economics and economic policy).

Understanding of ‘Business Activity’

As in the broader BHR field,Footnote 89 large transnational and multinational corporations, primarily those domiciled in the Global North, have been of greatest interest in the BHR-LA subfield. Indeed, the violations by these companies tend to be the largest-scale and most visible, and have been of particular interest in regulatory debates due to the jurisdictional challenges that their activities pose. However, other forms of business activity common in the region, specifically informal labour, small and medium entrepreneurship, and large domestic entrepreneurship, have received little to no attention.Footnote 90 As Arévalo-Narváez and Carrillo-Santarelli point out: ‘some argue that transnational [companies] are more worrisome given their resources, yet investigations have shown how relatively unknown, local and small companies perpetrate many of the abuses around the world, reason why they indeed must be subject to international responsibilities as well’.Footnote 91 Expanding the range of business activities studied is an important direction for further research, particularly in the Latin American context.

Understudied and Emerging Issues, Actors and Sectors

Several themes of high relevance to the region have received incommensurate scholarly attention to date. Firstly, while environmental concerns have been recurrent in the literature and several authors have focused on environmental rights, relatively little attention has been paid to the intersections of climate change and BHR; that is to say, while individual works begin to crop up on the subject,Footnote 92 it is yet to become a mainstream approach to considering climate change impacts. That is despite the fact that Latin America is home to landmark efforts in rights-based climate litigation.Footnote 93

Secondly, while much is known about the gendered nature of differential impacts of business-related rights violations in the Latin American context, the implications of these remain relatively unexplored in the BHR field. Women are increasingly acknowledged as victims in the literature, yet to date little analysis has been dedicated to understanding how the specific ways in which they are affected should be addressed in BHR practice, despite the recent recognition in the UNWG-BHRFootnote 94 that the UNGPs must be viewed with a gender lens. The relatedFootnote 95 subject of sexual violence in the context of business violations is another gap. As there now exists a robust community of social science scholars focused on studying sexual violence as a form of political violence,Footnote 96 cross-field collaboration might offer interesting potential to bridge this gap. Finally, a few passing mentions in several recent works suggest a budding acknowledgement of the BHR impacts on LGBT populations,Footnote 97 another area worth exploring further.

Similarly, the role of International Financial Institutions (IFI) such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the Inter-American Development Bank, as facilitators of abuses has at once been amply acknowledged and not explored in detail. Across our database, 118 (or 38 per cent) of the works made a mention of at least one of the three institutions to contextualize the rights violations described. This is an aspect of particular salience to the Latin American context as IFI were key in the economic liberalization reforms in the 1980s that many of the texts refer to for background on the current state of BHR in the region. However, the review did not yield a single work focused exclusively on their role. Furthermore, relatively little attention has been paid to the WTO dispute resolution mechanism, even as the experiences of Latin American states before it have been subject to debate in other fields.Footnote 98

The fourth potent area of further research is an expansion of the geographical focus regarding home states. While the literature to date has covered extensively abuses associated with North American and European companies, as well as relevant legal frameworks and jurisprudence on extraterritoriality in these regions, the literature has thus far not focused on the emerging players in international investment. In the Latin American context, two directions appear relevant. On the one hand, very few works to date have focused on the human rights impacts of China’s investments in the region, despite the fact that since 2010 Chinese companies have invested, on average, about US$10 billion per year in Latin American countries.Footnote 99 On the other hand, the historically increasing foreign investment by companies from Latin America merits attention.Footnote 100 Despite the fact that the operations of Latin American companies in other countries, either within the region or beyond it, have the potential to generate similar human rights vulnerabilities and jurisdictional challenges, accounting for the impacts of such companies has not yet become part of the regional debate. As the BHR-LA subfield enters its second decade, these changing global dynamics of power are an essential development to take stock of in the future literature.

VI. Conclusions

The contribution of this article is twofold. Firstly, it is the first, to the authors’ knowledge, systematic identification, examination and analysis of the extant literature on BHR in Latin America. Our database, available on file, not only can be a helpful starting point to scholars wishing to examine further specific issues in this branch of literature but the systematic approach and specific methodology – based on PRISMA – used, can also be replicated to conduct similar geographically or thematically focused assessments. Secondly, our review provides a comprehensive overview of the state of the regional BHR-LA literature to date, including an assessment of main themes, conceptual debates, sectors, rights categories, affected populations, and methodological and disciplinary approaches, as well as metadata such as publishing trends, accessibility, and geographical distribution. These findings are further used to highlight some of the main contributions of Latin American cases and perspectives to the broader BHR field, show what has and has not been covered in the subfield, and suggest a research agenda based on gaps identified.

Latin America – as both a subject in works about the region and a source of perspectives on BHR through works by authors from the region – has played an important role in the thematic and conceptual development of the BHR scholarship. Our study has found that, among the key domains, determined and shaped by the region’s characteristics, through which this has taken place are the focus on Indigenous rights, discussions on corporate accountability in transitional justice contexts, the emphasis on judicial accountability, and the role of the Inter-American Human Rights System. More broadly, the review shows that it is the interactions with specific scenarios in which corporate human rights abuses are committed that the academic debate on BHR gains force – and from which it takes inspiration. This reinforces the importance of ensuring that a diversity of contexts is duly represented in the field.

From the vantage point of assessing the place of Latin America in the BHR scholarship as a region in the Global South, a few additional considerations need to be mentioned. Latin American contributions to this field are unique in a couple of ways. Firstly, the relatively high average standards of livingFootnote 101 and political stability position it comparatively well with regard to both funding and accessing research and educational resources.Footnote 102 As a result, while some of the regional characteristics described above are not unique to Latin America, but rather shared across other regions considered part of the Global South – for instance, recent experiences of armed conflict or the violations of rights of Indigenous populations – part of the reason why they are likely to be brought to light in BHR scholarship in a Latin American context may lie in questions of access.

Latin America is in a special position within the BHR field in one more regard: the shared language(s) of scholarly conversation facilitated a growth of robust scholarship that is regionally oriented.Footnote 103 On the one hand, this robust internal discussion provides a much-needed alternative to what are currently considered ‘mainstream’ Global North publishing outlets and somewhat rearranges and decentralizes the scholarly discussion in the field. On the other hand, however, it is unclear how fluid the exchange is between this (or these) regional discussion(s), and the wider field. This can have the unfortunate result of some important insights that could enrich the understanding of BHR beyond Latin America, as this section attempted to demonstrate has been the case, being ‘trapped’ to smaller pockets of scholarship.Footnote 104

The production of scholarship in the BHR field – in Latin America and elsewhere – does not take place in a vacuum. Rather, it is strongly determined by the limitations and problems in the ways in which law – and particularly international law – is studied, researched,and practised. The disparities in representation, publishing tendencies that emphasize certain outlets, and serious accessibility constraints that this systematic review evidences, offer insights that might be valuable for enhancing diversity in this growing academic community.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare none.