The 2017 election of president Trump in the US may be considered as the final step in the mainstreaming of populist radical right parties and politicians in western democracies. The recent electoral successes of populist parties in countries such as Austria, Switzerland, Denmark, Belgium, Italy and Germany has intensified an already lively scholarly debate on the political preferences of these parties, their politicians and their electorate (see for instance Afonso, Reference Afonso2015; Reference MuddeMudde, 2007, Reference Mudde2013; Reference StockemerStockemer, 2017). Without doubt, the nationalist and anti-immigrationist stands are the most prominent items on the agendas of the populist parties (see Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, & Bornschier, Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal and Bornschier2008). However, following the presumed mixed composure of their electorate, the positions of these parties on social-economic issues are less clear. Afonso (Reference Afonso2015, p. 277) even argues that these parties are ‘keen on blurring their positions in order to appeal to different categories of voters with conflicting economic preferences’ (see also Rovny, Reference Rovny2013). In addition, some other authors have pointed out the seemingly contradictory positions of populist radical right parties within the socio-economic domain (see Reference OeschOesch, 2008). This article sets out to identify the positions of populist radical right parties on social policies in six different countries.

Focusing on the last decade, we could argue that the social policy agenda in many western countries has been characterised by three to some extent contradictory trends. First, a prolongation of austerity measures in and during the aftermath of the Great Recession, with a variety of measures including increasing the pension age, tightening eligibility and increasing conditionality (see for instance Taylor-Gooby, Reference Taylor-Gooby2013). Second, an agenda of realigning social policies with the new social risks of the post-industrial society (see Reference BonoliBonoli, 2005; Reference Pierson and PiersonPierson, 2001a). Here, measures include promoting gender equality, allowing access to social protection for precarious workers and accommodating the influx of migrants. This calls for modernising the role of government in social policies. Finally, a growing popularity of the ideas of social investment in many welfare states, with pleas for investment in human capital, research and development and equal opportunities for children (see Reference HemerijckHemerijck, 2015; Reference Morel, Palier, Palme, Morel, Palier and PalmeMorel, Palier, & Palme, 2012). In contrast with the austerity agenda, the social investment agenda calls for an increasing role of government in social policies.

There has been only limited research on the attitudes of these populist radical right parties towards the welfare state is, and the research that has been done suggests a lack of coherence both within parties and between parties (Reference AfonsoAfonso, 2015; Reference Ennser-JedenastikEnnser-Jedenastik, 2018; Röth, Afonso, & Spies, Reference Röth, Afonso and Spies2017). But populist radical right parties are considered important political players either through their direct participation in government or through their indirect effects on the position of other parties Bale, Reference Bale2003; Aichholzer, Kritzinger, Wagner, & Zeglovits, Reference Aichholzer, Kritzinger, Wagner and Zeglovits2014; Reference Arzheimer and RydrenArzheimer, 2013; Schumacher & Van Kersbergen, Reference Schumacher and Van Kersbergen2016). By offering a systematic and comparative analysis of the social agenda of populist radical right parties, this article contributes to our understanding of the future development if the welfare state in an era in which populist radical right parties are directly or indirectly co-determining the social agenda of their countries.

This article is structured as follows. The next section summarises the available literature on populist radical right parties (PRRPs) and their social agendas. Then, I provide an update of the more recent social challenges that may be included in PRRPs’ social agendas. After outlining the methodology of the analysis, the article presents an overview of the social policy agendas of populist radical right parties in six countries: France, Sweden, Germany, the US, Belgium and the Netherlands. This overview is based on a content analysis of party manifestos and selected speeches of the parties and their leaders. The article concludes with a reflection on the main findings both for the development of welfare states in the era of political fragmentation and for social policy scholarship.

PRRP's and their social agendas

According to Mudde (Reference Mudde2007), populist radical right parties (PRRPs) share three common characteristics: they are nativists, authoritarian and populist. Nativist refers to the ideology that states should be inhabited exclusively by members of the native group and that non-natives are threatening to the homogenous nation state (Reference MuddeMudde, 2007, p. 19). Authoritarianism refers the strong preferences for law and order of radical right parties. With populist, Mudde refers to the anti-establishment and anti-elite attitudes of radical right parties. Despite these common characteristics there are also differences between these parties, for instance with regards to regional separationist standpoints or the attitudes towards homosexuality (see Reference RooduijnRooduijn, 2015).

Considering the social preferences of PRRPs, three different positions in scholarship can be distinguished. The first position is the classical position. It states that radical right parties pursue a neo-liberal social agenda. For instance, one of the classic sources in this field of study is Betz (Reference Betz1993). He considered the ‘pronounced neo-liberal programme’ as the main characteristic of radical right parties, in addition to their militant attacks on immigrants (Reference BetzBetz, 1993, p. 417). According to Betz, radical right populist parties

have tended to hold strong anti-statist positions. (…) The resulting programme marks a revival of radical liberalism. It calls for a reduction of some taxes and the abolition of others, a drastic curtailing of the role of the state in the economy and large-scale privatisation of the public sector (idem: 418).

With regard to the welfare state, Betz (Reference Betz1993, p. 421) argues that ‘[r]ather than seeking to return to the comprehensive corporatist and welfare-state-oriented policies of the past, they (PRRPs [mf]) embrace social individualisation and fragmentation as a basis for their political programmes’. In short, we may call this position the neo-liberal position.

The second position may be referred to as the ‘welfare chauvinism’ position. The concept welfare state chauvinism was coined by Andersen and Bjørklund (Reference Andersen and Bjørklund1990). Traditionally, it reflects an anti-immigration attitude towards social policy (see for instance Schumacher & Van Kersbergen, Reference Schumacher and Van Kersbergen2016). Briefly put, welfare chauvinism reflects the opinion that social benefits should be restricted to ‘nationals’ (Reference OeschOesch, 2008, p. 352) or ‘our own’ (Andersen & Bjørklund, Reference Andersen and Bjørklund1990, p. 212). From an analysis of the electorate of PRRPs, Afonso (Reference Afonso2015, p. 275) states that the PRRP-electorate

tends to be constituted by social groups who are typically protected by classical social insurance schemes in Bismarckian welfare systems, and who may be afraid to extend these rights to outsider groups, such as immigrants and women. The “welfare chauvinist” attitude is probably the most characteristic expression of this (…). As a whole, this electorate can be expected to defend the welfare status quo.

In this article, I use the term ‘welfare chauvinism’ to refer to an anti-immigration, nativist perspective on social policies.

A third perspective is what I label the ‘welfare nostalgia’ perspective. This perspective is inspired by Häusermann, Picot, and Geering (Reference Häusermann, Picot and Geering2012), who stretch the meaning of the concept ‘welfare chauvinism’ to the exclusion from social benefits of a broader group of outsiders of the labour market: not only migrants, but also women and perhaps even other non-traditional workers like self-employed and temp workers. The electoral preferences that are associated with ‘welfare nostalgia’ are not necessarily racist or xenophobic, but need to be interpreted in a wider perspective of ‘modernisation losers’ (see for instance Minkenberg, Reference Minkenberg2003; Reference RydgrenRydgren, 2007) and traditional gender roles (see Reference AkkermanAkkerman, 2015a; Spiering, Zaslove, Mügge, & De Lange, Reference Spiering, Zaslove, Mügge and De Lange2015). Following Bezt (Reference Bezt1994), the modernisation losers can be understood as

those who are unable to cope with the ‘acceleration of economic, social and cultural modernisation’ and/or are stuck in full or partial unemployment, run the risk of falling into the new underclass and of becoming ‘superfluous and useless’ for society (Reference RydgrenRydgren, 2007, p. 248; quotes from Bezt Reference Bezt1994, p. 32).

Recently, there has been a growing attention for the role of gender in PRRPs. Akkerman (Reference Akkerman2015a, p. 56) shows that ‘almost all parties are conservative when they address issues related to the family, such as opportunities for women on the labour market, childcare, abortion or the status of marriage’. Therefore in this article, welfare nostalgia refers to policy positions that are aimed at securing or reinforcing the social position of the modernisation losers based on traditional economic and family patterns. This perspective differs from the welfare chauvinism perspective as its core is not the exclusion of foreigners, but the restoration of ‘traditional’ labour relations and social rights.

PRPPs and trends in social policies

In the previous section we have identified three theoretical expectations about the social policy preferences of PRRPs. But these parties do not develop their social policy positions in a static vacuum. They are confronted with a dynamic environment in which welfare states are challenged by numerous economic, demographic, social and cultural developments. These challenges lead to a widely-felt need to reform these welfare states (see for instance Pierson, Reference Pierson and Pierson2001a). In the scholarly literature on welfare state development, three main routes for reform can be distinguished: austerity, modernisation and social investment (see for instance Hemerijck, Reference Hemerijck2013; Reference Taylor-GoobyTaylor-Gooby, 2013; Van Kersbergen, Vis, & Hemerijck, Reference Van Kersbergen, Vis and Hemerijck2014). As these three types of reform can be identified in the political programmes of traditional political parties and in the policy reforms that are implemented in current welfare states (see Taylor-Gooby, Reference Taylor-Gooby2013; Van Kersbergen et al., Reference Van Kersbergen, Vis and Hemerijck2014). PRRPs will need to relate their policy positions to these three trends. In this section I first briefly elaborate on these types of reform, and then relate the theoretical expectations about PRRP's social policy positions from the previous section to these reform types.

The first type of reform is austerity. As a consequence of the Great Recession, many countries have been forced to radically cut in their social programmes. The concept of austerity includes two different strategies to do so: cost containment and retrenchment. Cost containment is, not surprisingly, aimed at reducing the costs of social programmes without reforming them, for example by not adjusting benefit levels to inflation rates. Retrenchment is aimed at cutting costs by reforming social programmes, for instance through changing the entitlement conditions or limiting duration of the programme (Van Kersbergen et al., Reference Van Kersbergen, Vis and Hemerijck2014; see also Pierson, Reference Pierson and Pierson2001b).

A second type of reform stems from the transition from industrial to post-industrial society (see Reference Pierson and PiersonPierson, 2001a). In a very influential article, Bonoli (Reference Bonoli2005) has argued that this transition also implies a transition from ‘old’ to ‘new’ social risks. The ‘old’ social risks are the risks to which the post-World War II welfare state was supposed to be an answer: the risks of loss on income through unemployment, old age, sickness or becoming widowed. The new social risks refer to the risks that are the consequences of the recent developments in the post-industrial societies. Bonoli (Reference Bonoli2005) identifies five types of new social risks: (1) reconciling work and family; (2) single parenthood; (3) having a frail relative; (4) possessing low or obsolete skills; and (5) insufficient social security coverage. In response to the transformation of these risks, reforms have been proposed and implemented in various countries and in various policy domains to contribute to accommodate the transformation from old to new social risks (see for instance Jenson, Reference Jenson2008).

A final type of social policy reforms in recent years is the so-called social investment paradigm. According to Hemerijck (Reference Hemerijck2013, Reference Hemerijck2015) the social investment paradigm is replacing other traditional ideals of the welfare state. The social investment state aims to increase social inclusion and minimise the intergenerational cycle of poverty in order to protect its population from the increasing insecurity (flexibilisation) of the labour market. Two principles are central in the social investment perspective. The first principle is based on the equality of opportunity, and thereby following the liberal notion of equality. By creating equal opportunities through investment the intergenerational cycle of poverty should be broken. Therefore, the social investment paradigm highlights the importance of education and the prominent position it takes through one's life. The second principle rests on the premise that promoting social inclusion by investing in individuals and thereby expanding the active and civil society is beneficiary for the collective good (Jenson & Saint Martin, Reference Jenson and Saint Martin2006). The key element of social investment is that social policies should ‘prepare’ individuals, families and societies for new risks, rather than ‘repair’ old risks.

Following from our earlier exploration of PRRPs social policy preferences, we may now predict the positions of PRRPs in relation to these types of reforms. In a welfare chauvinism perspective, all socio-economic preferences are related to the PRRPs core issues of nativism, populism and authoritarianism. This implies that there is no general support or opposition for each of the three types of reforms, but that it depends primarily from the design of the reforms. As long as reforms safeguard the position of deserving groups and or undermine the rights of non-deserving groups, there may be support for these measures. Deserving citizens in this perspective are native, obedient, common citizens (see Ennser-Jedenastik, Reference Ennser-Jedenastik2016). As indicated in the precious section, the welfare nostalgia perspective as interpreted in this article is less nativist than the welfare chauvinism perspective. From this perspective, we therefore expect little support for the reform measures that have been discussed in the section. Protecting the losers of modernisation implies a return to the golden age of the welfare state in this perspective, with preferably undoing many of the earlier reforms. And as PRRPs in this perspective also tend to have a strong preference for traditional family values, social investment measures that challenge these values will receive little support or even outright opposition. Finally, from the neo-liberal perspective we might expect support for all measures that cut back on the welfare state and all the regulation involved with it. So if PRRPs’ ideologies indeed depend on the neo-liberal agenda, there will be support for austerity measures, for modernisation measures that are aimed at deregulation, for instance in the area of dismissal laws and labour conditions regulations. Moreover, from this perspective we can expect very limited support for social investment measures, as these tend to increase the role of government in the economy. These expectations are tested in the remainder of this article.

Methodology

To explore the social policy agenda of radical right parties and politicians, six different countries were selected: the US, Sweden, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium and France. These mix of countries represents the three traditional Esping- Andersen (Reference Esping- Andersen1990) welfare regimes and the data in these countries are accessible rather easily. Moreover, in each of these countries, populist radical right parties or politicians have gained a considerable amount of votes at the recent elections, even though in the case of the US, it is questionable to what extent Trump can be considered as a populist radical right politician. One of the leading scholars in the field of populist radical right parties, Mudde, gives a clear argument for including Trump in this study:

Trumpismo can be seen as a functional equivalent of the European populist radical right, but it is a very American equivalent. Trump himself doesn't hold a populist radical right ideology, but his political campaign clearly caters to populist radical right attitudes, and his supporter base is almost identical to the core electorate of populist radical right parties in (Western) Europe (Reference MuddeMudde, 2015).

The article uses content analysis of speeches and party manifestos as its main method of data analysis.

The parties that are included in this analysis are the Republican Party in the US, the Dutch Partij voor de Vrijheid (PVV), Sweden Democrats, Alternatives for Germany (AfD), the French Front National, and the Flemish Vlaams Belang. For some parties, specifically in the Netherlands and the US, the relation between the populist radical right party and its leader differs from the traditional forms of representation. In the case of Trump this is obvious; we can hardly call the Republican Party a populist radical right party, whereas various scholars and commentators agree that Trump can be considered as a populist radical right politician (see for instance Greven, Reference Greven2016; Reference Hogan and HaltinnerHogan & Haltinner, 2015; Reference MuddeMudde, 2015). Therefore, we will refer to ‘Trump’ rather than to the Republican Party in the remainder of this article. In the Netherlands, the Freedom Party lacks the traditional party structure. Therefore, the personal views of its leader Geert Wilders determine the party positions.

To perform the analysis, three speeches of the leaders of the parties have been selected from the period between 2010 and 2017. This time frame has been selected to allow the inclusion of different themes, as speeches within a relative short time frame tend to revolve around similar themes. As a trade-off, the economic context between 2010 and 2017 has significantly changed but there are no indications that this has affected the party positions on specific themes. Whenever possible, speeches were selected that were given at important occasions and had the intention to highlight the position of the party and its leader on a number of policy issues. Examples of such occasions are acceptance of the nomination for leadership of the presentation of a party manifesto. In addition, the content analysis also included the most recent party manifesto of the parties. For Donald Trump, no proper party manifesto was available. As Trump's speeches tend to focus on a small set of topics, additional comments have been used that clarify Trump's position on a number of items (see on-line appendix for the full details of speeches, manifestos and additional sources that have been used in the analysis).

In this article, I use a rather open conceptualisation of social policies, based on Marshall's (Reference Marshall1967, p. 7) classical definition:

(…) the policy of governments with regard to action having a direct impact on the welfare of the citizens, by providing them with services or income. The central core consists, therefore, of social insurance, public (or national) assistance, the health and welfare services, housing policy.

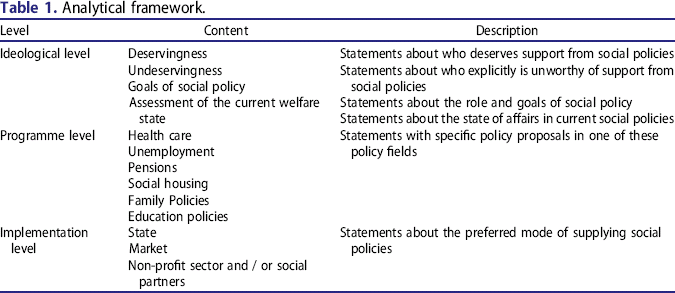

Based on a preliminary scan of the policy domains the prevailed in the speeches and manifestos, I focus on the fields of health care, pensions, unemployment, education and family policies. The technique that was chosen for the content analysis is semi open coding. Synthesising the work of Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith (Reference Sabatier, Jenkins Smith and Sabatier1999) on the one hand and Gilbert and Specht's (Reference Gilbert and Specht1993) on the other hand, I have distinguished three levels of welfare state preferences of PRRPs.

The first level is the ideological level. This level includes what Sabatier calls the ‘deep core beliefs’. Deep core beliefs refer to the normative and fundamental assumptions that span multiple fields of social policies. These preferences define who is deserving and undeserving of social support, what the goals of social policy in general are and how the current policy system should be assessed from the normative and fundamental assumptions. This may be compared to Gilbert and Specht's ‘allocation’ level. For the ideological level, we are primarily interested in the definition and redefinition of deservingness (see Van Oorschot, Reference Van Oorschot2000).

The second level is the programme level. I take this level to include Sabatier's so-called policy core level, which reflects the normative and empirical assumptions on the level of specific policy programmes. This shows some familiarity with Gilbert and Specht's ‘provision’ level. The programme level builds upon the work of Van Kersbergen et al. (Reference Van Kersbergen, Vis and Hemerijck2014). These authors make a distinction between compensation strategies, cost containment strategies, retrenchment strategies and social investment strategies.

The final level is what I call the implementation level. Sabatier here uses the term ‘secondary aspects’ and refers to primarily to the policy tools that are implemented to reach the policy goals. In my interpretation for this paper, I choose to follow Gilbert and Specht's idea of ‘delivery’, and focus on the preferred way of implementing social policy. The implementation level analyses what the favourite means of administering and implementing social policies are (see Reference Fenger, Henman and FengerFenger, 2006). Each statement about social policy has been coded into one of these levels. This leads to the analytical framework that guides the data analysis as presented in Table 1.

Analysis of social policy preferences of PRRPs

The ideological level

On the ideological level, ‘welfare chauvinism’ seems to be the dominant position for the populist parties in all six countries, even though there are considerable differences between the parties in the ways they approach the position of immigrants. As for the issue of deservingness, there are three groups that are explicitly mentioned in the speeches or party manifestos: veterans, elderly, and ‘ordinary citizens’. On various occasions, Trump has highlighted the deservingness of veterans, for instance at his acceptance speech of the Republican nomination: ‘We will take care of our great Veterans like they have never been taken care of before’. Veterans are the only deserving group that Trump mentioned in the speeches that have been analysed. The elderly are a group that are highlighted by the Freedom Party in the Netherlands, the Sweden Democrats and the Front National in France. For instance the Sweden Democrats state: ‘The elderly in Sweden deserve access to the world's best care for the elderly’, whereas Marine le Pen used the phrase of the ‘courageous’ elderly who started working at the age of 14 and should not suffer from poverty in their old age. Finally, both the Party for Freedom and Flemish Interest explicitly highlight ‘the ordinary citizen’ as a group that deserves support. To quote Wilders: ‘We choose for “Henk” and “Ingrid”.Footnote 1 Ordinary citizens that work hard and are worried’. In similar fashion, Flemish Interest claims to stand up for ‘the scared, white man or woman’. Less outspoken, the Sweden Democrats plea for the necessity of a ‘common identity’ as a prerequisite for solidarity.

On the issue of who is not deserving of support from the welfare states, the parties’ opinions seem to converge even more. There is a wide consensus in all countries except Sweden that immigrants are not deserving of social support or even are a threat to the welfare state. The most extreme positions here are taken by the Dutch Freedom Party and the Flemish Vlaams Belang. To quote Wilders: ‘The welfare state no longer is a shield for the weak, but a withdrawal counter for lazy immigrants, for “Ali” and “Fatima”’.Footnote 2 Or according to the Flemish Interest Party: the welfare state is not intended ‘for “hammock immigrants” that seek a better future here for themselves and their children at the expense of the Flemish tax payers’. Trump and AfD do not address the unspecified group of immigrants but specifically focus on illegal immigrants (Trump) or asylum seekers (AfD) and do so in a more moderate voice.

Only three parties explicitly phrase their goals for the future of the welfare state. Trump's vision is characterised by the well-known one -liner ‘We will bring back our jobs’. This is a goal that Trump shares with Marine LePen for France: ‘To relocate our businesses and therefore our jobs’. Whereas Trump leaves it at that, Le Pen also reflects on wider goals of the welfare state: ‘To create a welfare state that guarantees equal opportunities for everyone and a favourable economic climate’. The Sweden Democrats are even more ambitions in their goals: ‘each citizen is guaranteed a high level of physical, economic and social security’. The parties are much clearer about what's wrong with the current welfare state, and all of them except Trump represent a firm welfare chauvinist position here: ‘Immigration is what's wrong with the current welfare state’. For instance, Geert Wilders states ‘The welfare state, our pride where Dutch people have paid for with conviction for decades, that welfare state has become a magnet for fortune-seekers’. In other, more moderate phrases, most other parties also highlight the threat that immigration is to the sustainability of the welfare state. For instance AfD states: ‘A country can have a well-advanced social system. And a country can have open borders. But a country cannot have a well-advanced social system and open borders’. The only outlier on this issue is Donald Trump, who claims that poverty as a consequence of loss of jobs caused by globalisation is the most important problem of the welfare state.

Table 2 provides a brief overview of the positions on all dimensions as far these could be retrieved from the sample of speeches and manifestos that have been analysed. Even though we have not been able to assess all dimensions for all parties, it is clear from this analysis that social policy preferences of the PRRPs in most countries on the ideological level can be addressed as ‘welfare chauvinist’. The only exception is Donald Trump. His focus on bringing back employment to the US also does not fit with the neo-liberal position, as it requires a firm intervention of the state in the economy. Therefore, I use the term ‘economic chauvinism’ for the Trump social agenda. Within the other countries, we can distinguish two groups. The Dutch Freedom Party and the Flemish Interest Party take a rude and hostile position against immigrants, whereas the other parties are much more moderate in their welfare chauvinist positions.

The programme level

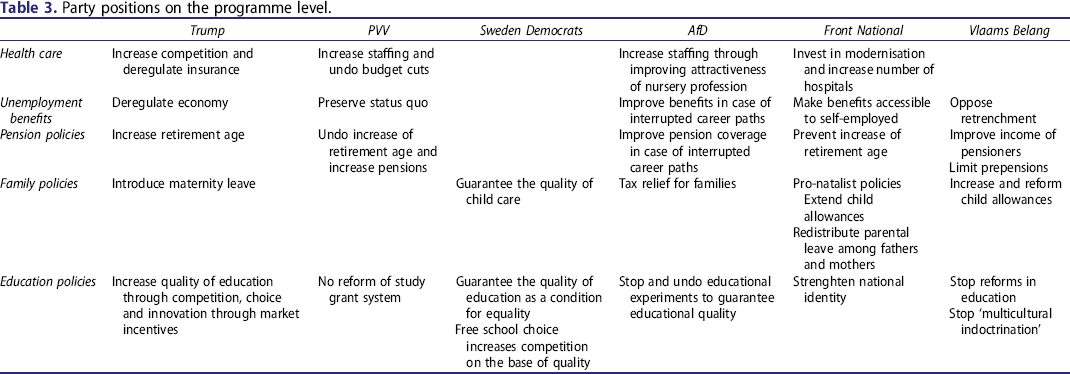

The programme level focuses on ‘our’ parties’ goals, proposals and assessments in specific social policy domains. Just like in the previous section, there is no full set of statements for each party on each domain. However, as we will see, this does not hinder in the systematic analysis of each parties’ position on the programme level.

In the domain of health care, both AfD and PVV highlight the understaffing in hospitals and nursery homes. For Wilders’ PVV, the understaffing is a direct consequence of the policy of the governing coalition. To quote Wilder: ‘In the Netherlands of prime-minister Rutte, our elderly are starving and dehydrating in loneliness because there are not enough nurses. In the Netherlands of prime-minister Rutte, health care was demolished’. Therefore, Wilders claims that he will be ‘happy to get his wallet out’ to invest in additional staff. AfD seeks the solution in improving payment and consequentially standing of the nursery profession. The Front National also proposes to invest in health care to increase the number of hospitals and to modernise the French health care system. For instance, LePen proposes to ‘support French start-ups to modernise the health system’. Finally, it has been hard to ignore that the revocation of Obamacare was on the top of Trump's agenda. According to Trump, the mandatory character of Obamacare limits competition and leads to the increase of costs at the individual and national level.

In the area of unemployment protection, Trump is not very outspoken, but seems to promote deregulation as the most important way out of unemployment. PVV and Vlaams Belang both take a firm anti-austerity position. ‘Simply reducing the duration of unemployment benefits to contain costs is asocial’, according to the latter. Finally, both AfD and Front National have proposals that can be considered as updating the benefit system to the demands of the current labour market. In the case of Front National, this is aimed at self-employed, as they propose to ‘Create a social shield for the self-employed by offering them the choice to join the general scheme or to retain the specificity of their scheme’. AfD want to restore the unjust consequences that ‘different occupational biographies’ have for benefit coverage.

With regard to pension policies, Trump again is the outsider, as he is the only one proposing to – carefully – increase the pension age: ‘Without disadvantaging present retirees or those nearing retirement, set a more realistic age for eligibility in light of today's longer life span’. In contrast, Front National, Vlaams Belang and PVV do not wish to increase the pension age or, in the case of PVV, even propose to undo the recent increase. In addition, Vlaams Belang and PVV also have proposals to improve the position of retirees. PVV does so by proposing to increase second pillar pensions to correct for inflation, Vlaams Belang has various tax proposals in order to reach this goal. Vlaams Belang seems to be aware of the rising life expectance that challenges the sustainability of the pension scheme, but considers ‘increasing the duration of actual careers’, for instance through limiting pre-pensions schemes, as a sufficient solution.

On the topic of family policies, AfD and Vlaams Belang focus on improving the financial position of families with children. Vlaams Belang does so by increasing the child allowance, AfD through tax relief for parents and continuation of unemployment benefits for unemployed parents. The National Front in France also proposes to extend child allowances, and, in addition, proposes a pro-natalist policy to increase fertility. Moreover, the Front National proposes to ‘restore the free distribution of parental leave between the two parents’. The Sweden Democrats emphasise much more the importance of good quality childcare:

Central to all forms of childcare is that the child groups should be as small as possible, parents should be offered a significant influence over the activities, the children's imagination and livelihood are best used and that stress and noise levels are reduced to a minimum.

Finally, and somewhat surprisingly, Trump is the first Republican president to propose paid maternity leave, as he stated that his administration wanted ‘to help ensure new parents have paid family leave’.

Finally, concerning education, almost all parties state to favour high-quality education. Geert Wilders is the less outspoken here, claiming only that he will not reform the system of study grants and free travel for students. Trump assesses the current education system as ‘an education system flush with cash, but which leaves our young and beautiful students deprived of all knowledge’. The solution is neo-liberalist: ‘We will rescue kids from failing schools by helping their parents send them to a safe school of their choice’, and ‘in order to encourage new modes of higher education delivery to enter the market, accreditation should be decoupled from federal financing’. The Sweden Democrats just highlight the importance of good quality education for equality: ‘The starting point is that all children regardless of family background, place of residence and parents’ income must have good prerequisites for success in life’. They share with Trump the idea that free choice of parents is a way to force school to deliver high quality education. The AfD is very critical of a few recent innovations in German education policy, including the so-called competence-oriented learning and the EU-wide harmonisation of university studies in the Bologna process. To quote: ‘For over decades now, our teachers and students have been tortured with new educational experiments. The permanent revolution in school and universities has seriously harmed’ the German education system, according to AfD. For Front National, the strengthening of the French identity through education is the key point. This is done through restoring ‘the authority and respect of the teacher and establish the wearing of a school uniform’, but most and for all, through teaching the commandment of ‘our beautiful French language’ and ‘the love for our culture’. Finally, Vlaams Belang shares with AfD a repulsion of the reform waves in education. Moreover, it states that ‘the multiculturalist indoctrination in education should immediately stopped’, taking again a firm chauvinist position.

Table 3 provides a brief overview of the positions of each of the parties on the programme level. Overall, we could state that Trump again and clearly represents the neo-liberal position, just as Vlaams Belang and PVV represent a ‘welfare nostalgia’ position, with – in the case of Vlaams Belang – a slight tendency towards a welfare chauvinist position. Despite the lack of data on some elements, the Sweden Democrats are clear in the social investment position. AfD and Front National are a bit harder to position, but show a clear tendency towards the modernisation agenda.

The implementation level

The final level is the implementation level. Even though this is less idea-driven than the other levels, we still can observe some differences in the preferences among the parties. Two dimensions have been distinguished here: the desired division of tasks between state, private, non-profit and corporatist actors and the desired division of tasks between the national, regional and local level.

Starting with the first dimension, it will come as no surprise that Trump starts from the individual responsibility. An example of this is given when he discusses the responsibility of parents: ‘Parents have a right to direct their children's education, care, and upbringing. We support a constitutional amendment to protect that right from interference by states, the federal government, or international bodies such as the United Nations’. Even though they are not always explicit about it, the PVV, seems to prefer a strong position of the state, which is somewhat in contrast with their anti-establishment character. As said, we only have circumstantial evidence for this. For instance in the case of the PVV, when Wilders states ‘Occupational pensions should be corrected for inflation’, he either chooses to ignore the fact that decision about the height of the benefit are taken by the boards of private pension funds, or he advocates state interference in pension governance. Both the Sweden Democrats and the AfD are proposing to allow private delivery in some cases. For instance, the Sweden Democrats state: ‘To improve the performance of welfare services alternative and private operating modes should be allowed’. Classical German is the proposal to increase the financial contribution of employers to long-term care and health insurance.

In relation to the division of tasks between the national level and the local level, Trump is clear in continuing to restrict the federal level: ‘We repeat our longstanding opposition to the imposition of national standards and assessments’. In Sweden, the Sweden Democrats are afraid of unrestricted local autonomy, and therefore plea for national guidelines in the areas of care and cure: ‘National quality care and care requirements must exist and may not undershot. The county council, municipality or district may not be decisive for what quality of care elderly, weak and sick shall receive’. AfD and Front National both are concerned about the availability of all kinds of social services in rural areas, and plea for national interference. Finally, Vlaams Belang shares with Trump a preference for the state – as opposed to the federal – level, but from a nationalistic perspective: ‘Social policy should be based on the mutual solidarity of Flemish people’.

Table 4 shows a brief summary of the positions of the parties on the implementation level. Even though there are data missing and there are slight differences between the countries, we can categorise the countries as follows. Trump pleas for a decentralised, private mode of implementing welfare services. The other parties seem to favour centralised, public systems of delivery with the exception of Vlaams Belang that stands for public, regional delivery.

Conclusions and discussion

In the previous sections, the positions of populist radical right parties on a number of social policy issues have been discussed in detail. Table 5 summarises these positions into a limited number of key concepts. The goal of this article was to identify and explain the similarities and differences in the social policy agenda of six populist radical right parties. In response to this goal, the following conclusions may be drawn (Table 5).

On the theoretical level, three conclusion can be drawn. First, from the exploration of available scholarly work, three distinctive perspectives on PRRPs’ social policy positions have been identified: the traditional neo-liberal perspective, the welfare chauvinism perspective and the welfare nostalgia perspective. The empirical analysis shows that with the exception of Trump, the neo-liberal explanation does not have much validity. Even though it was very prominent in the first wave of radical right scholarship, there is hardly any European populist radical right party that still embraces neo-liberalism. This also illustrates the very limited relation between Trump and European radical right leaders, even though some European leaders highlight their association with the Trump administration and its ideology. From this analysis, the answer to the question whether or not Trump should be considered as a PRRP-politician tends to be negative. The second conclusion on the theoretical level relates to the complex relation between welfare chauvinism and welfare nostalgia. Even though we have a limited number of cases in our analysis, it is remarkable that the parties with the fiercest anti-immigration perspectives are also the parties that show the least support for the reforms of austerity, post-industrial modernisation and social investment. There seems to be no welfare nostalgia without fierce welfare chauvinism, and opposite. Moreover, the “strong welfare chauvinism” position seems to go hand-in-hand with a rejection of the necessity to adjust the welfare state to new economic, demographic and social realities like an ageing population or growing single parenthood. A final theoretical conclusion is that from this analysis there seem to be two current modes of populist radical right politics: the PVV/Vlaams Belang variety with a fierce and hostile position against immigration, where the welfare chauvinist ideology indeed seems to dominate all other positions. However, there also seems to be a more pragmatic variety that can be found in Germany, Sweden and even in France. Here, the positions in relation to immigration are similar to these in other countries, but with more careful phrasing and – which is remarkable – more acceptance of the needs of reform in the welfare state. This distinction between the dogmatic and pragmatic radical right is worth exploring further in other countries and in relation to other issues and also in relation to other policy issues, for instance global warming.

An interesting and important empirical conclusion relates to the strong belief and trust in the ability of (central) government to govern society and solve societal problems. Whereas a lot of scholarly literature on public policy making highlights the limited capacity of governments and the necessity of co-production or even self-governance, most of the PRRPs that have been analysed in this article strongly reject these ideas. Instead of the radical liberalism that traditionally was attributed to populist parties, from this analysis it appears that all parties show a strong belief in the role of the central state as the key actor to resolve social issues and to reduce social risks. The initiative for social policies according to almost all parties should be with central government.

Building upon this, a final conclusions considers the differences between PRRPs, specifically on the programme level. On an abstract level, “welfare chauvinism” may seem like their uniting principle. And indeed, we find welfare chauvinism in the heart of the ideologies of all European populist radical right parties. But if we delve one layer deeper, there is rather a lot of variation on the programme level. I have classified the positions of the Party for Freedom and Vlaams Belang as welfare nostalgia on the programme level. According to the speeches and the party manifestos that have been analysed, these parties would like to return to the “golden age” of the welfare state. In contrast, AfD and Front National tend to embrace the post-industrial modernisation positions. Finally, on the programme level the Sweden Democrats’ position can be best characterised as social investment. Treating PRRPs as a single group in practical and scholarly publications obscures their mutual differences and – perhaps more importantly – obscures the underlying question how this can be explained. As discussed earlier, various authors attribute the different social policy positions of PRRPs to the characteristics of their electorate (see for instance Oesch, Reference Oesch2008; Reference RydgrenRydgren, 2007). However, the variation that can be observed on the programme level may also have other explanations. I will outline two possible explanations here.

The first explanation may be related to the characteristics of the political landscape in a country. As several authors have shown, there seems to be a relation between the position of mainstream parties and PRRPs. This is obvious in the area of immigration and multiculturalism, where the position of mainstream liberal parties has become increasingly strict (Reference AkkermanAkkerman, 2015b). According to Akkerman this can not only be explained by electoral competition nut also by the real-life policy experiences with immigration and multiculturalism. In the domain of social policies, specifically the strategy of mainstream left (labour) parties may be of importance for the political position of PRRPs. If labour parties embrace the need for austerity and reform of the welfare state, there may be electoral opportunities for PRRPs in defending the welfare state. Moreover, also the experiences with earlier policy reforms may affect PRRPs’ positions. For instance, the welfare nostalgia in the Netherlands and Belgium may be caused by the negative experiences, specifically for the electorate of populist radical right parties, with the rather radical reforms in these countries. On the other hand, the necessity to adapt the French labour market institutions to the demands of the globalised, post-industrial economy may be felt by all French political parties, including the Front National. So there seems to be a relationship between the political landscape and the policy positions of mainstream parties in a country, the characteristics and reform processes of the welfare state and the social policy agenda of populist parties which needs to be explored further.

Building upon the previous explanation, a second explanation may be found in the relationship between individual preferences of voters in different welfare regimes and the position of PRRPs. The relation between individual welfare state preferences and welfare regimes has been explored by different scholars, for instance by Larsen (Reference Larsen2008) and Roosma, Gelissen, and Van Oorschot (Reference Roosma, Gelissen and Van Oorschot2013). The main conclusion seems to be that voters in different welfare regimes have different attitudes towards the welfare state. Consequentially, this may affect the position of populist parties as well. To explore this relation further, a more in-depth analysis of the formation process of these opinions and positions is needed, including a close monitoring of the evolution of these positions. But one conclusion can be safely drawn from this article. Those who feared that the growing popularity of populist radical right parties may lead to a dismantling of the welfare state can be reassured: if anything, the social policy positions of populist radical right parties seem to be more inclined towards a revival than a dismantling of the welfare state.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Appendix

List of speeches used:

Donald Trump from the Republican Party

- Acceptance republican nomination

21-7-2016, Cleveland Ohio.

Retrieved from: [http://www.politico.com/story/2016/07/full-transcript-donald-trump-nomination-acceptance-speech-at-rnc-225974]

- Inauguration speech

20-1-2017, Washington Capitol building.

Retrieved from: [https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2017/01/20/donald-trumps-full-inauguration-speech-transcript-annotated/?utm_term = .5ab05bd18e46]

- Victory speech presidential selection

9- 11-2016, New York

Retrieved from: [http://edition.cnn.com/2016/11/09/politics/donald-trump-victory-speech/].

Marine Le Pen from National Front (Front national)

– Annual party gathering 2015

1-5-2015, Paris

Retrieved from: [http://www.frontnational.com/2015/05/discours-de-marine-le-pen-vendredi-1er-mai-2015/]

– Annual party gathering 2016

1-5-2016, Paris

Retrieved from: [http://www.frontnational.com/2016/05/1er-mai-2016-discours-de-marine-le-pen/]

– Presidential assessment 2017

5-2-2017, Lyon.

Retrieved from: [http://www.frontnational.com/videos/assises-presidentielles-de-lyon-discours-de-marine-le-pen/].

Geert Wilders from the party for Freedom (Partij voor de Vrijheid)

– European Populist Party congress 2017

21-01-2017, Koblenz

Retrieved from: [https://ejbron.wordpress.com/2017/01/21/video-speech-geert-wilders-op-enf-congres-in-koblenz-integrale-nl-vertaling/]

- General Political Considerations 2016 (Algemene Politieke Beschouwingen)

21-9-2016, The Hague

Retrieved from: [https://www.pvv.nl/36-fj-related/geert-wilders/9258-inbreng-geert-wilders-bij-de-algemene-politieke-beschouwingen-2016.html]

– Presenting candidates 2010

9-6-2010, The Hague

Retrieved from: [https://www.pvv.nl/index.php/component/content/article/12-spreekteksten/2856-speech-geert-wilders-pvv-presenteert-kandidaten].

Filip de Winter from Flemish Interest (Vlaams belang)

– Annual party gathering 2012

7-10-2012, Zuiderkroon

Retrieved from: [http://www.filipdewinter.be/tag/toespraak]

- End of the year speech 2014

5-2-2014, Hove

Retrieved from: [http://www.filipdewinter.be/category/toespraken]

– End of the year speech 2012

22-1-2012, Antwerp

Retrieved from: [http://www.filipdewinter.be/tag/toespraak]

Björn Höcke from Alternative for Germany (AfD)

- Demonstration in Erfurt 2015

16-9-2015, Erfurt

Retrieved from: [http://afd-thueringen.de/reden/]

- Demonstration in Jena 2016

20-1-2016, Jena

Retrieved from: [http://afd-thueringen.de/reden/]

– Gathering from Young Alternative in Dresden 2017

17-1-2017, Dresden

Retrieved from: [http://www.tagesspiegel.de/politik/hoecke-rede-im-wortlaut-gemuetszustand-eines-total-besiegten-volkes/19273518.html].

Jimmie Åkesson from Sweden democrats (Sverigedemokraterna)

- Annual party gathering 2011

10-7-2011, Almedalen

Retrieved from: [http://www.svt.se/nyheter/inrikes/las-hela-jimmie-akessons-almedalen-tal]

- Annual party gathering 2014

3-7-2014, Almedalen

Retrieved from: [https://sdkuriren.se/jimmie-akessons-tal-i-almedalen-2014/]

- Annual party gathering 2016

7-7-2016, Almedalen

Retrieved from: [http://www.mynewsdesk.com/se/sverigedemokraterna/pressreleases/talmanus-jimmie-aakessons-tal-i-almedalen-2016-1470279]

List of manifestos used:

-AfD: Manifesto for the national parliamentary elections 2017

Retrieved from: [http://www.afd-obb-sued.de/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/afd-programm-bundestagswahl-2017.pdf].

-PVV: Manifesto for the national parliamentary elections 2017–2021

Retrieved from: [https://www.pvv.nl/visie.html]

-National Front: Manifesto for the presidential elections 2017

Retrieved from: [https://www.marine2017.fr/2017/02/04/projet-presidentiel-marine-le-pen/]

-Sweden democrats: Manifesto 2011 (also used in the elections of 2014)

Retrieved from: [https://sd.se/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/principprogrammet2014_webb.pdf]

-Flemish Interest: Manifesto for the national parliamentary elections 2014

Retrieved from: [https://www.vlaamsbelang.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/20140318ProgrammaVerkiezingen2014.pdf].

-Trump

Republican platform 2016

Retrieved from: [https://www.gop.com/the-2016-republican-party-platform/]

BBC (2017). First 100 days: Where President Trump stands on key issues. Retrieved from: [http://www.bbc.com/news/election-us-2016-37468751].

Timm, J. C. (2017). The 141 Stances Donald Trump Took During His White House Bid. NCB news.

Retrieved from: [http://www.nbcnews.com/politics/2016-election/full-list-donald-trump-s-rapidly-changing-policy-positions-n547801].

Politiplatform (2017). Donald Trump's policies on All. Retrieved from: [https://www.politiplatform.com/trump].

Timm, J. C. (2017). Tracking President Trump's Flip-Flops. NCB news.

Retrieved from: [http://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/president-trumps-first-100-days/here-are-new-policy-stances-donald-trump-has-taken-election-n684946].