1. Introduction

Various proposals have been made in the literature, arguing that bound pronouns are, in some sense, deficient.Footnote 1 Kratzer (Reference Kratzer, Strolovitch and Lawson1998) argues that bound pronouns are semantically deficient, lacking an index, and points out that this semantic deficiency may be reflected in morphological and syntactic deficiency, as outlined by Cardinaletti and Starke (Reference Cardinaletti, Starke and van Riemsdijk1999). Déchaine and Wiltschko (Reference Déchaine and Wiltschko2002), focusing on evidence from morphological subparts of pronouns, argue that syntactic deficiency is relevant for binding. DP pronominals, for example, may not be bound. When stripped of the morphology encoding the DP layer, however, the remaining pro-ϕPs may be bound. Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona (Reference Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona1999) argue that Malagasy pronouns also must be syntactically deficient in order to be bound, but that in Malagasy, the syntactically deficient pronouns lack not the outer DP layer but the inner NumP layer. Further, they show that the syntactically deficient pronouns behave differently from syntactically complete pronouns even in ways that have nothing to do with binding.

We examine the claims just mentioned in the context of the morphological and syntactic properties of pronouns in a variety of Malagasy that we call Malagasy2. This variety behaves differently from the one described by Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona, which we call Malagasy1. We reach two conclusions: the first is that there are no syntactically deficient pronouns in Malagasy2 and that syntactically complete pronouns may be bound. If this is true, then the correlation between bound pronouns and syntactic deficiency cannot be a universal prerequisite for binding. Our second conclusion is that these authors are nevertheless correct that the lack of NumP accounts for a cluster of properties. We found that in Malagasy2, where all pronouns share the same non-deficient syntax, none of the distinctions between pronouns that Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona catalogue appear.

This article is organized as follows. In section 2 we give the theoretical setting of our investigation and a view of the internal structure of Malagasy pronouns. In section 3 we present three tests outlined by Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona that demonstrate that the presence of NumP blocks binding, and then we show how their results differ from the data we have collected from Malagasy2. In section 4 we examine Malagasy1 and Malagasy2 in the context of two other tests for syntactic deficiency from Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona (Reference Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona1999). Our conclusions, summarized in section 5, are that (i) syntactically complete pronouns may be bound, as evidenced in Malagasy2, and (ii) since the distinctions that are present in Malagasy1 do not exist in Malagasy2, Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona's tests do detect differences in syntactic structure. In section 6 we conclude and lay out directions for future research.Footnote 2

2. Background

We begin with a brief introduction to the notion of deficient pronouns, starting with Kratzer's semantic analysis. We then show how the semantic notion of deficiency is deployed by Déchaine and Wiltschko (Reference Déchaine and Wiltschko2002) and correlated with the absence of syntactic structure. These discussions prepare the ground for an overview of Malagasy pronouns and their morphological complexity.

2.1 Kratzer 1998

Kratzer (Reference Kratzer, Strolovitch and Lawson1998) proposes that there are ‘zero pronouns’, which are pronouns that “start their syntactic life without ϕ features” (Kratzer Reference Kratzer, Strolovitch and Lawson1998: 94).Footnote 3 These zero pronouns, lacking ϕ features, must receive their index from an antecedent, and hence may only appear in bound environments. In (1), the sloppy reading is possible: apart from the speaker, no individual (or group of individuals) had the property of being an x such that x got a question x thought x could answer. We therefore have zero pronouns. In other words, under the sloppy reading, the second and third instances of the first person pronoun are interpreted as bound by a local subject.Footnote 4 This binding is only possible if the pronouns are in fact zero pronouns, as represented in (1b), and there is a local antecedent.

(1) Sloppy reading possible

a. Only I got a question that I thought I could answer.

b. Only I got a question that

$\emptyset$ thought

$\emptyset$ thought  $\emptyset$ could answer.

$\emptyset$ could answer.

In (2), however, a zero pronoun would be unable to receive an index since there is no local antecedent (there is an intervening non-coindexed subject, you), hence there is only a full pronoun and a strict reading (Kratzer Reference Kratzer, Strolovitch and Lawson1998: 94). Thus the representation in (2b) is ruled out.

(2) Sloppy reading not possible

a. Only I got a question that you thought I could answer.

b. Only I got a question that you thought #

$\emptyset$ could answer.

$\emptyset$ could answer.

While locality is crucial for a first or second person pronoun to be bound, it is not necessary for a third person pronoun, as shown in (3) where the pronoun's antecedent is not the closest subject. Kratzer argues that third person pronouns are not indexical and therefore may behave as variables without being zero pronouns.

(3) Sloppy reading possible

Only this man got a question that you thought he could answer.

While Kratzer focuses on the semantic aspects of pronoun deficiency, she cites Cardinaletti and Starke (Reference Cardinaletti, Starke, Thráinsson, Epstein and Peter1996, Reference Cardinaletti, Starke and van Riemsdijk1999) as showing that “zero pronouns seem to surface as the ‘weakest’ pronouns permissible in the position they find themselves in” (Kratzer Reference Kratzer, Strolovitch and Lawson1998: 97). She gives as an example the necessity of dropping a coindexed pronoun in Spanish, a pro-drop language.Footnote 5 In (4a), the presence of an overt pronoun leads to a strict reading. In (4b), however, the sloppy reading is possible due to pro-drop – clearly the weakest possible form.

Two important distinctions are made here. First, third person pronouns are not indexical and therefore are able to be bound in positions where first and second person pronouns cannot be bound, and second, in contexts where pronouns are bound, a weaker form of the pronoun is chosen if possible. In (4) we saw a case where a bound pronoun is dropped entirely, but Cardinaletti and Starke (Reference Cardinaletti, Starke and van Riemsdijk1999) provide other environments where weak and strong pronouns behave differently. We will see another example in the discussion of Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona (Reference Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona1999) in section 4.1, but here we give only one such environment to make a slightly different point.

Cardinaletti and Starke (Reference Cardinaletti, Starke and van Riemsdijk1999) observe that strong but not weak pronouns may appear in conjoined structures. Below we see the weak Slovak pronoun ho may not appear in a conjoined structure (see 5b), while its strong counterpart jeho may (see 5c).

What is important to note is that ho is a subpart of jeho, suggesting that the extra morphology in the strong form points to extra syntactic structure. Cardinaletti and Starke argue that the weaker form is missing the top layer of the pronominal projection, which, for them, is the nominal counterpart of the complementizer layer. This tight link between syntactic complexity and morphological complexity will be a recurrent theme as we continue.

2.2 Déchaine and Wiltschko (Reference Déchaine and Wiltschko2002)

Déchaine and Wiltschko (Reference Déchaine and Wiltschko2002) propose that there are three types of pronouns: pro-DPs, pro-ϕPs and pro-NPs. Their properties are summed up in Table 1.

Table 1: Nominal proform typology (Déchaine and Wiltschko Reference Déchaine and Wiltschko2002: 410)

The part of this table that will be important to us is the distinction between Pro-DPs and Pro-ϕPs in terms of their status with respect to binding. Pro-DPs are assumed to be R-expressions and therefore unable to be bound, while Pro-ϕPs may act as variables. These differences parallel Kratzer's distinction between pronouns with an index and those without. Déchaine and Wiltschko also link this semantic distinction to a difference in morphological structure – which for them correlates to a difference in syntactic structure – similar to that proposed by Cardinaletti and Starke (Reference Cardinaletti, Starke and van Riemsdijk1999).Footnote 6

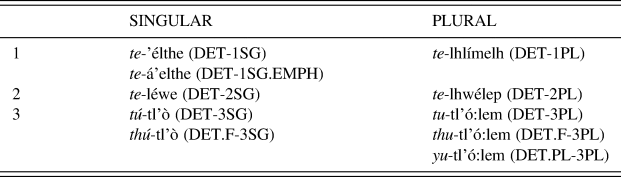

Déchaine and Wiltschko illustrate the morphological, and hence syntactic, complexity of a DP pronominal with data from Halkomelem independent pronouns. We see in Table 2 the Halkomelem pronominal paradigm, with the D part of the pronoun in italics. Wiltschko (Reference Wiltschko, Caldecott, Gessner and Kim1998, Reference Wiltschko2002) proposes the structure in (6) to capture this morphological complexity.

(6) Pro-DP structure (DET-3SG)

Table 2: Halkomelem independent pronouns Déchaine and Wiltschko (Reference Déchaine and Wiltschko2002: 412)

To support this analysis, Déchaine and Wiltschko present the data in (7), showing that the same D and ϕ morphology may be used with an overt N in Halkomelem.

Further, using the data in (8), they argue that the use of tl’ò alone in a cleft construction shows that a pro-ϕP, without an overt N, can be used on its own as a predicate.

Having seen that the subparts of these Halkomelem pronouns may be used separately, we turn to their data involving pronominal binding constructions. Déchaine and Wiltschko's system predicts that the full DP pronouns in Halkomelem should not be able to be bound. They show that this is indeed the case, using the data given in (9) and (10), from Déchaine and Wiltschko (Reference Déchaine and Wiltschko2002: 414).Footnote 7

We turn now to the pronominal system in Malagasy. As in Halkomelem, pronouns are built from bits of morphology that we argue, following the work of others, indicate the existence of specific syntactic heads.

2.3 Malagasy pronouns

Malagasy is an Austronesian language spoken in Madagascar by over 25 million people. The unmarked word order is VOS, as seen in (11). The example in (11a) illustrates ActorTopic (AT) voice, where the agent ianao ‘you (sg)’ is the subject, while (11b) illustrates ThemeTopic (TT) voice, where the theme ny alika ‘the dog’ is the subject. The pronominal agent in (11b) appears as a suffix on the verb.Footnote 8

There is much debate about the nature of the clause-final ‘subject’ position and the voice system, but we set this aside here (see Pearson Reference Pearson2005 for a discussion), instead focusing on the pronominal system.Footnote 9 The variety of Malagasy discussed in this article, which we are calling Malagasy2, is Merina, spoken in the highlands of Madagascar.

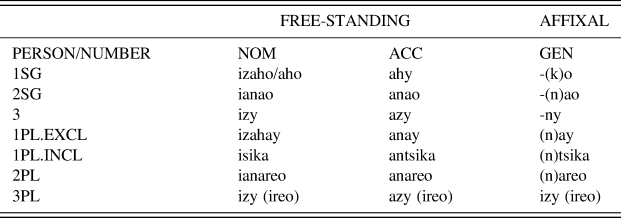

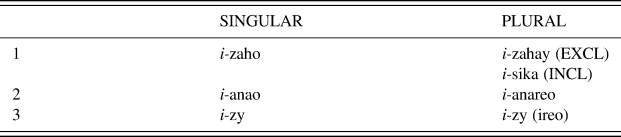

Malagasy is typically described as having two types of pronouns: free-standing and affixal (see Table 3).Footnote 10 The free-standing pronouns are further divided into the ‘nominative’ and ‘accusative’ series. We will call the affixal pronouns ‘genitive’, as this form of the pronoun is also used for possessors (see Keenan and Polinsky Reference Keenan, Polinsky, Zwicky and Spencer2001: 577 for more details about the genitive pronominal forms). We note in passing that these labels (nominative, accusative, genitive) are also subject to debate, but we set that debate aside as it is not relevant for the purposes of this article.

Table 3: Malagasy pronominal system

One of the issues that we will be discussing is the realization of number on third person pronouns. For present purposes, we adopt the standard description in the literature, which states that the third person pronoun is unmarked for number (number-neutral) but can optionally be explicitly marked as plural via the addition of the plural demonstrative ireo (Keenan and Polinsky Reference Keenan, Polinsky, Zwicky and Spencer2001).Footnote 11 There is yet another third person plural variant, ry zareo, which we set aside here. We return to a more in-depth discussion of number in section 3.

Our first goal is to show that Malagasy pronouns are morphologically complex and contain a Determiner morpheme (as we have seen in Table 2 for Halkomelem), as well as a Number morpheme. The discussion will start with locatives, however, since the internal structure of pronouns is built on the internal structure of demonstratives, which in turn is built on the internal structure of locatives.

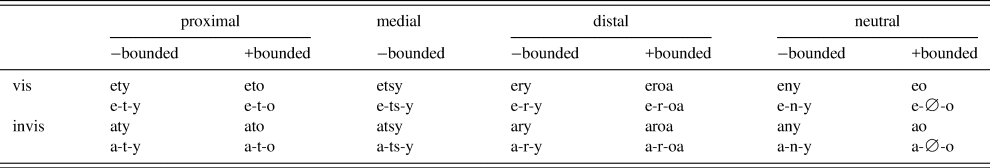

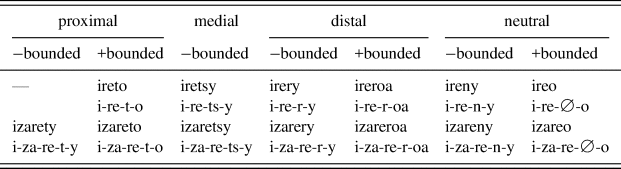

The locative system has sometimes been described as encoding six or seven degrees of distance (Anderson and Keenan Reference Anderson, Keenan and Shopen1985), but as argued by Rajaona (Reference Rajaona1972) and Imai (Reference Imai2003), there are only three relevant distances: proximal, medial, distal, as well as a set of neutral locatives, which can be used for a wide range of distances for the most part overlapping with the other locatives. Other variables that are morphologically marked involve visibility and boundedness (see Table 4 and Imai Reference Imai2003 for details). Below we give a minimal pair from Imai (Reference Imai2003: 108). Where the proximal visible location being referred to is in a confined specific area, the visible proximal bounded demonstrative eto is used, as in (12a). Where the proximal visible location being referred to is in a vague unconfined area, the visible proximal unbounded demonstrative ety is used, as in (12b).

Table 4: Locatives

Rajaona (Reference Rajaona1972) proposes the following morphological decomposition: the initial vowel encodes visibility (e vs. a), the medial consonant encodes distance (t vs. ts vs. r vs. ![]() $\emptyset$/n) and the final vowel encodes boundedness (y vs. o).Footnote 12 For the purposes of this article we simply adopt Rajaona's analysis.

$\emptyset$/n) and the final vowel encodes boundedness (y vs. o).Footnote 12 For the purposes of this article we simply adopt Rajaona's analysis.

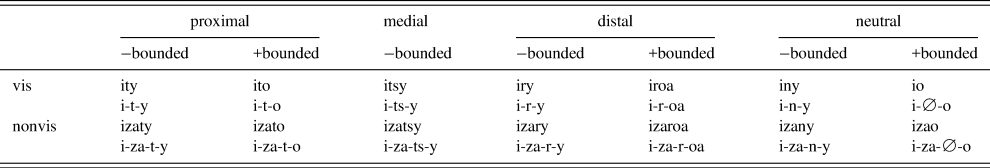

Rajaona compares the locative paradigm to the demonstrative paradigm and proposes that demonstratives are derived by adding the i- morpheme (which he calls a definite marker) to locatives (see Table 5). We can see in (13) how such demonstratives are used.Footnote 13

Table 5: Demonstratives

As can be seen in the bottom rows of Table 5, there is a /z/ that appears between the i- prefix and the visibility marker a.Footnote 14 In what follows, we build on Rajaona's analogy between locatives and demonstratives.

The correlation between the locative and the demonstrative paradigms is very clear, and we propose to extend this parallelism to the pronominal paradigm. We will see, however, that the match is not as clear, because the pronominal paradigm is much less regular. Our first step is to argue that the i- prefix found on demonstratives is also found in the pronominal paradigm, and to offer additional support for the Det status of the prefix i-.

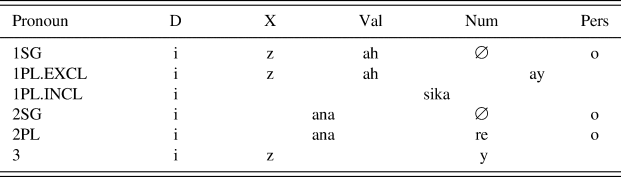

Nominative pronouns can be distinguished from the accusative and genitive (affixal) pronouns by the prefix i-, as shown in Table 3. In Table 6 we replicate the nominative part of the paradigm.Footnote 15

Table 6: Complexity of Malagasy pronouns (first approximation)

We follow Rajaona in assuming that i- represents the definite marker, which we place in D. This makes the analysis of Malagasy pronouns similar to Déchaine and Wiltschko's (Reference Déchaine and Wiltschko2002) analysis of Halkomelem pronouns. Another argument for treating i- as a determiner comes from its use with certain proper names (there are other proper name determiners, such as Ra; see Rajemisa-Raolison (Reference Rajemisa-Raolison1971: 24) for a description and Paul (Reference Paul, Gentile, Lamontagne, Paul, Kalin and Klok2018) for discussion). Some examples are given below that show that i- (i) appears with proper names, as in (14a), (ii) is used to form place names as in (14b), and (iii) is used to name animal characters, as in (14c) (from Paul Reference Paul, Gentile, Lamontagne, Paul, Kalin and Klok2018: 326).

Having made the connection between the initial prefix i- in nominative pronouns and demonstratives, and then having related this to the D head, we now turn to the existence of NumP, which will be crucial to our discussion of Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona (Reference Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona1999) in section 3.Footnote 16 To do this, we include a look at plural demonstratives.

Malagasy rarely shows number distinctions, but there are two clear areas where number is marked – in the demonstrative system and the pronominal system. The plural demonstratives are shown in Table 7.Footnote 17 What is important to note is where the plural morpheme re- appears – after the marker of visibility and before the marker of distance (e.g., i-za-re-t-o).

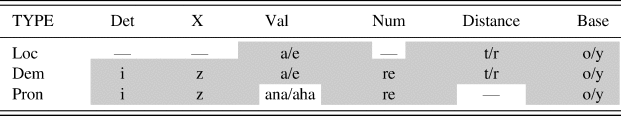

With this information in mind, we now turn to pronouns. Beyond the appearance of the i- prefix, the most obvious other similarity between demonstratives and pronouns is the use of re- to form the 2PL pronoun from the singular one (2SG: ianao; 2PL: ianareo). This suggests that the breakdown of the 2PL pronoun is i-ana-re-o. To push the comparison of pronouns to demonstratives further, this morphological breakdown suggests that the ana- in the 2PL pronoun is in a position parallel to the visibility morpheme in a form such as i-za-re-o. Further, the z that appears before the visibility morpheme a in the demonstrative system could be matched with the z that appears in the pronominal forms izaho: 1SG and izahay: 1PL.EXCL (making izaho morphologically similar to the demonstrative izato). Table 8 outlines a speculative correlation of the morphemes found in the pronominal system as compared to the morphemes in the locative and demonstrative systems. There are areas that need further examination, such as the status of z, which we have simply labelled X, and an analysis of ana/aha, which occupy a position parallel to the visibility morpheme in the demonstrative system.Footnote 18 Here we label this position with the vague term Value, for lack of a better choice. Clearly, the correlation between the locatives and the demonstratives is more solid than that between demonstratives and pronouns, but we hold that, at the very least, the determiner i- prefix and the use of the plural re- point to a similarity in the internal morpho-syntactic structure of demonstratives and pronouns.

Table 7: Plural demonstratives

Table 8: Locatives/Demonstratives/Pronouns

Another reason to conclude that demonstratives and pronouns are closely related comes from their syntactic distribution. We see similarities between pronouns and demonstratives particularly in terms of their position within the DP. As we saw in (13), demonstratives generally frame the DP in Malagasy, such that the same demonstrative appears on both sides of the DP, as shown in (15).

While certain demonstratives can appear on their own in initial position (ity), others cannot (io).

What is uniformly excluded is a single post-nominal demonstrative.

Strikingly, the initial demonstrative may be replaced by a pronoun, as in (18). In these examples, a pronoun appears in initial position, followed by a noun and then a demonstrative.Footnote 19 For example, in (18a) the first-person singular pronoun izaho is in initial position, followed by the noun vehivavy ‘woman’ and the demonstrative ity. In (18b), we see a similar example with the first-person exclusive plural accusative pronoun anay. The example in (18c) illustrates that framing is also possible with the genitive series (in this case -nay (1st person plural exclusive)), despite their affixal status.

The framing construction highlights the connection between pronouns and demonstratives, to the exclusion of determiners. The definite determiner ny, for example, does not participate in framing, as shown in (19).

We do not provide an analysis of the framing construction here, but only note the similarity in function between the demonstrative system and the pronominal system.Footnote 20 In Table 9, we flesh out how pronominal morphology might fit into the demonstrative template.

Table 9: Pronominal morphemes

Summing up, we have shown that pronouns in Malagasy have internal demonstrative morphology and that they also share their distribution with demonstratives. We leave a development of this comparison for future work and now turn to the work of Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona and the relationship between pronominal structure and binding.Footnote 21

3. Malagasy and Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona (Reference Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona1999)

Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona (Reference Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona1999) present an in-depth study of the internal structure and external distribution of Malagasy pronouns. Their goal is to test the ideas of Cardinaletti and Starke (Reference Cardinaletti, Starke and van Riemsdijk1999) who, like Déchaine and Wiltschko (Reference Déchaine and Wiltschko2002), propose that pronouns come in different sizes. Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona come to several important conclusions. One is that deficiency can be syntactic, morphological, or phonological. Crucial for our purposes, they provide evidence that morphological deficiency does not entail syntactic deficiency. That is, affixal (genitive) pronouns are not necessarily syntactically deficient. A second conclusion is that syntactic deficiency in Malagasy occurs not when the top-most layer of the nominal projection is missing, but rather when the Number projection is missing. At this point in our discussion we concentrate on this view of syntactic deficiency.

Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona propose a variety of tests for the absence of NumP. In section 3.2, we introduce three of them, setting up the interaction of syntactic deficiency and pronominal binding. In section 3.3, we will see that the variety of Malagasy spoken by our consultants (Malagasy2) differs from that described by Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona (Malagasy1) with respect to all three of these tests. In Malagasy1, third person pronouns that are unspecified for number behave differently from first and second person pronouns, as well as from third person pronouns with number marked overtly. In Malagasy2 however, there is no distinction in the behaviour of pronouns, suggesting that they all contain NumP. We show further that syntactically complete pronouns may be bound. In section 4, we return to the remaining two tests with similar results: while the data in Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona (Reference Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona1999) show a split between those pronouns with overt number and those without, no such split appears in Malagasy2 – an expected result if all pronouns in Malagasy2 are structurally the same. This result confirms that in Malagasy1, this cluster of properties is indeed sensitive to the presence of NumP, as proposed by Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona.Footnote 22

We begin by showing first that our speakers obligatorily mark number on third person pronouns (izy/azy/-ny for 3SG and izy ireo/azy ireo for 3PL). We then show that not only can these overtly third person plural pronouns be bound, but all pronominal forms may be bound, including first and second person forms.

3.1 Number and Malagasy DPs

The three tests to be discussed are: (i) number interpretation, (ii) pronominal binding by a non-quantified DP, and (iii) pronominal binding by a quantified DP. Before turning to the tests, we introduce more generally the role of number in Malagasy.

As noted earlier, number is generally underspecified in Malagasy DPs. When using the default determiner ny as in (20a), the interpretation of the nominal can be either singular or plural. However, determiners that appear with proper names, what Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona call nominal articles, show a distinction in number, as in (20b) vs. (20c), and we saw in Table 7 that demonstratives have a singular (20d) and a plural (20e) form.

Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona propose that underspecified number indicates the absence of the NumP within the DP.Footnote 23 The structure in (21), where Number is encoded in the form of the determiner, represents a non-deficient DP, while (22) represents a syntactically deficient DP, one that is missing NumP. In this case, it is a DP with a default determiner, which is underspecified for number.

3.2 Binding in Malagasy1

We turn now to the distribution of NumP in pronouns.Footnote 24 Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona argue that first and second person pronouns in Malagasy have a NumP, while third person does not. The first test looks at the correlation between the morphological realization of number and the semantic interpretation.

Test 1: Number interpretation We have already seen (Table 3) one reason to posit that the head Num is morphologically encoded: first and second person pronouns have distinct forms for singular and plural, while third person only optionally appears with a plural demonstrative form. Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona show, however, that the appearance of this marking in Malagasy1 depends on the construction. In fact, the third person, when not explicitly marked for plural, must generally be interpreted as singular. We see this in (23) below, where the simple form izy in (23a) must be interpreted as singular; it can only receive a plural interpretation if Number is expressed overtly with the plural demonstrative, ireo, as in (23b).

We do have situations, though, where overt marking is not only unnecessary but is actually prohibited. Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona (1999: 198) show that, under certain conditions, the third person form that is unspecified for number may be interpreted as either singular, as in (24a), or plural, as in (24b).

Crucially, these interpretations depend on whether or not the pronoun is semantically bound, where we understand semantic binding to mean c-command and coindexation leading to a variable interpretation, not just simple coreference. In (23) the pronouns are not bound, while in (24) they are. Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona argue that semantically bound pronouns, as in (24), do not contain a NumP and that their number interpretation is provided by the DP which binds them. When a pronoun is not semantically bound, as in (23), it must contain a NumP. This use of semantic binding to supply number features to a deficient pronoun leads us to the issue of semantic binding and syntactic deficiency more generally, and to Test 2 and Test 3.

Test 2: Binding by a non-quantified DP The examples below show that pronouns specified for number may not be semantically bound. We start with third person pronouns because these are the only pronouns that may lack NumP. In (25) we see that the accusative third person pronoun azy is used. Since the interpretation of this pronoun will be singular, it could be that it is the deficient form, in which case it must be semantically bound by the matrix subject. Alternatively, it could be the complete form, in which case it may simply be coreferential with the matrix subject, that is, the pronoun does not behave like a bound variable. The former case gives rise to the sloppy reading, while the latter case gives rise to the strict reading (Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona Reference Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona1999: 198–199).Footnote 25

In (26), the matrix subject is overtly marked plural through a plural demonstrative. In one case, (26a), the accusative pronoun in the embedded clause is unmarked for number. In order to receive a plural reading, it must be bound by the matrix subject, resulting in an obligatory sloppy identity reading. In (26b), where the number has been specified on the object azy ireo, this object may be co-referential with the matrix subject, but as a complete DP, it cannot be a variable. This status is confirmed by the impossibility of a sloppy reading.

As expected, since first and second person pronouns are always specified for number, they may not be bound. Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona give the example below to show that the strict reading but not the sloppy reading is available for the second person singular pronoun, anao.

Test 3: Binding by a quantified DP Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona also discuss how binding works when the antecedent is a quantifier. The main differences in these cases are that simple coreference is not allowed, and that a coindexed third person plural pronoun must always be syntactically deficient. This has the effect of making the use of the plural demonstrative ungrammatical, as (28) shows.

Having looked at Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona's claims about the syntactic deficiency of third person pronouns in Malagasy and its relation to pronominal binding, we now turn to our own findings. We will see that the data we elicited were quite different from those reported by Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona. While our data might be seen as simply refuting the need for syntactic deficiency to allow variable binding, we find the overall results to lead to a more interesting conclusion. We argue that there is no syntactic deficiency in Malagasy2. Rather than disallowing semantic binding of non-deficient pronouns entirely, however, as we have seen for Halkomelem (see (9) and (10)), pronominal binding is available across the board, in other words, not only for both singular and (overtly) plural third person pronouns but also for first and second person pronouns.

3.3 Binding in Malagasy2

We start by looking at how number is realized on the third person pronoun for our two consultants. For these speakers, plural interpretation of the pronoun is only possible if the plural demonstrative ireo is included. Recall that this was the case for speakers of Malagasy1 when the pronoun was not semantically bound, as reported by Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona (see (23)). We see, however, that this remains the case for our consultants even when the pronoun is semantically bound. Compare (24b) above with (29) below. In (24b) the plural demonstrative was prohibited, while in (29) it is obligatory.

This example tells us two things and leaves us with a prediction. One observation is that, in terms of Test 1, Malagasy2 differs from Malagasy1. It appears that in Malagasy2, number is always encoded in the third person pronouns; they are never number neutral. The other observation is that pronouns with explicit number may be bound, at least in the case of third person. In other words, azy cannot vary its number interpretation when bound, explaining the necessity of including the plural demonstrative in (29). If this is the case, then all pronouns in Malagasy2 are syntactically complete, and further, syntactically complete pronouns are able to be bound. The availability of a sloppy identity reading demonstrates the availability of binding (Test 2). If the example in (29) is followed by Rasoa koa ‘Rasoa too’, the meaning can either be that Rasoa thinks that the children are pleased (strict reading) or that Rasoa thinks that she herself is pleased (sloppy reading).

Now we turn to the resulting prediction. Given that third person pronouns may be bound when they explicitly contain number, binding in Malagasy2 is not sensitive to the presence/absence of number and we predict that all pronouns in Malagasy2 may be bound. We see that this is the case in the following examples. Taking first the example we saw above in (27) from Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona (Reference Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona1999), we note that our consultants allowed both strict and sloppy readings of the second person pronoun anao – the former deriving from co-reference and the latter deriving from a bound pronoun construction.

The data above therefore show that Malagasy1 and Malagasy2 differ both in terms of Test 1, number interpretation, and Test 2, binding by a referential DP. Test 3 will show that the two varieties also differ in terms of binding by a quantificational DP. Again, we see in (31) two differences from Malagasy1. First, as seen above, the plural demonstrative is obligatory to express number in the pronoun. Second, with the addition of Rasoa koa ‘Rasoa too’ we get both strict and sloppy readings. The strict reading shows coreference (Rasoa thinks some teacher is criticizing the students) and the sloppy reading shows binding (Rasoa thinks some teacher is criticizing Rasoa).

To summarize, we have found, in the variety of Malagasy spoken by our consultants, that (i) plural number must be overtly realized (Test 1), and (ii) binding of syntactically complete pronouns is possible and therefore all pronouns may be bound, (iii) this is true for binding by both referential DPs (Test 2) and quantificational DPs (Test 3). Much of the previous discussion has relied on sloppy vs. strict identity to determine whether a pronoun is bound or simply co-referential. In this context, a reviewer questioned the reliability of the test itself. In the next section we therefore investigate the two other tests for syntactic deficiency used by Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona – local binding and human interpretation. They argue that all of these tests are sensitive to the presence or lack of NumP.

4. Further tests for NumP

Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona provide two other distinctions that fall out from the deficiency of DPs in Malagasy1. We present them here and then show that the data from Malagasy1 as reported there once again differs from the data we elicited in Malagasy2. This has the nice result of confirming that these two properties can indeed be tied to the lack of NumP in certain pronouns in Malagasy1. In other words, some pronouns in Malagasy1 are deficient, leading to a split in how pronouns pattern in the language. However, in Malagasy2 no pronouns are deficient, and therefore we predict that all pronouns should pattern together.

4.1 Further tests in Malagasy1

Recall the core generalization from Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona: only deficient pronouns, those that lack NumP, can be bound. Importantly, the only context where we can be certain that a pronoun has no NumP is when it is bound.

Test 4: Local binding We first note that a third person pronoun in Malagasy1 with no NumP may be bound locally (within a clause). Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona (Reference Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona1999: 201) give data showing that the third person pronoun azy object may be bound by the subject.

Interestingly, there is a separate form, tena, that may be used to encode reflexivity, as shown in (33). We see, not surprisingly, that this reflexive form triggers sloppy readings. As we can see with the forced sloppy identity reading in (33) and (34), the pronoun azy is bound in the same way that the reflexive tena is bound.

Note that while Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona (Reference Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona1999: 201) do give an example of a construction using the form tena, as in (33), they suggest that this form is only used with certain verbs – “occurs in other lexical constructions” – suggesting that it is not as productive, and, more importantly, not required for local binding.

Test 5: Human restriction This test differs markedly from the previous four in that it addresses the question of whether the third person pronoun may have a non-human referent. It is hard to see why this property would follow from the lack of a number projection, and hence why it would be connected to cases of binding. Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona investigate this property due to the role it plays in the typology outlined by Cardinaletti and Starke (Reference Cardinaletti, Starke and van Riemsdijk1999), who show that strong pronouns in French (among other languages) may only refer to humans. In the data given below we see that the clitic le in (35b) may have a non-human referent (the film) or a human referent (Pierre). The strong pronoun lui in (35c), however, may only refer to Pierre.

Turning now to the Malagasy data presented by Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona, we see that the only time a third person pronoun may have a non-human referent is when it is bound. In (36b), where pragmatically the third person pronoun could refer back to the book, the child, or Rasoa as part of the discourse, only the humans referents are possible – the child or Rasoa.

In constructions where the third person pronoun is bound, however, it may have a non-human referent, as shown in (37).

Thus, the absence of NumP is also correlated with a lifting of the humanness constraint on pronouns.Footnote 26

4.2 Further tests in Malagasy2

As we have seen with binding, if no pronoun is syntactically deficient, as we claim is the case in Malagasy2, then a property that was once sensitive to deficiency is expected to lose that sensitivity. In the case of cross-clausal binding (Tests 2 and 3) we saw that the property of a few (bare third person pronouns) was extended across the board – all pronouns may be bound. We will see here a different outcome, but what remains the same is that the sensitivity apparent in Malagasy1 is lost. First, the possibility of local binding is lost entirely. Second, the possibility of having a non-human referent is extended to include all third person pronouns, but not to all pronouns for obvious semantic reasons (first and second person pronouns are conversational participants).

We start with Test 4, local binding. Both of our consultants found that coindexation of the pronoun with the subject was not possible in (38a) (compare with (32a) above). In order to get the interpretation of local binding, the reflexive ny tenany is used, as in (38b) (compare with (32b)) or tena as in (38c).Footnote 27

We note in passing that Paul (Reference Paul2002) argues that tena is a true reflexive pronoun (subject to Condition A), while ny tenany is not. There does appear to be some lexical and inter-speaker variation as to which verbs are compatible with tena and which allow ny tenany. We set this variation aside, as what is important for the current discussion is that speakers of Malagasy2 never allow a locally bound reading for the pronoun azy, unlike speakers of Malagasy1.

Turning now to the restriction of the use of unbound third person pronouns to human referents (Test 5), we see that this is also not the case in Malagasy2. While there is a tendency to assume that a human is being referred to, when the context is clear there is no difficulty in having an inanimate referent as shown in (39b). Further, as we see in (39c), even if the predicate does not impose animacy restrictions, speakers may allow either a human or an inanimate referent.Footnote 28

It turns out, then, that speakers of Malagasy2 consistently differ from speakers of Malagasy1 on these final two tests as well. All pronouns behave the same in terms of local binding of third person pronouns: it is never allowed. Further, third person pronouns show no restriction in terms of referring to non-human objects, even when not bound.

5. Summary and further thoughts

To sum up, we have explored pronominal binding in a variety of Malagasy that we have labelled Malagasy2 to distinguish it from Malagasy1, a variety presented by Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona (Reference Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona1999) Our goal was to determine whether or not pronouns in Malagasy2 showed signs of missing syntactic structure, a possibility suggested by the previous literature. We followed the model provided by Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona, who presented a variety of tests to show that syntactic deficiency in Malagasy1 involves a missing NumP. The results of these tests for Malagasy1 are given in Table 10.

Test 1 sets the stage. It is shown that the bound 3rd person pronoun azy is unrestricted with respect to number. According to Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona, this variability is due to the lack of NumP. Further, this syntactic deficiency is what allows azy to be bound both interclausally (Tests 2 and 3) and intraclausally (Test 4). In all tests, this pronoun behaves differently from all of the others.

The same tests, when applied to Malagasy2, produce different results, as shown in Table 11.

Table 10: Deficiency tests: Malagasy1

Table 11: Deficiency tests: Malagasy2

Starting again with number interpretation (Test 1), we see that third person no longer shows variability even when bound, suggesting that in this variety all pronouns contain NumP. Given that Malagasy2 has no deficient pronouns, we might not be surprised that all pronouns in Malagasy2 behave similarly when it comes to binding. In fact, this is what we see. But what is interesting is that intersentential binding (Tests 2 and 3) generalizes in a different fashion from intrasentential binding (Test 4). In the former case, the behaviour of the other pronouns is different from Malagasy1 and coincides with the behaviour of the third person bound pronoun: binding is possible across the board. In the latter case, it is the behaviour of the third person bound pronoun that differs from Malagasy1, and in Malagasy2 binding is impossible across the board. Finally, Malagasy2 differs from Malagasy1 in that both free and bound third pronouns can refer to non-humans, whereas reference to a non-human was only possible with bound third person pronouns in Malagasy2. One can think of this now, in some sense, applying across the board, restricted only by the fact that first and second person pronouns must refer to humans as conversational participants.

Stepping back, we take a look at the relation between deficiency and pronominal binding. What is the nature of the restriction on the binding of syntactically complete pronouns? As mentioned earlier, Kratzer (Reference Kratzer, Strolovitch and Lawson1998) points out that “zero pronouns seem to surface as the ‘weakest’ pronouns permissible in the position they find themselves in” (Kratzer Reference Kratzer, Strolovitch and Lawson1998: 97). But if there is no weak form available, can the strong form be bound? In the case of Halkomelem, argument positions do not allow ϕPs, so the DP form is the only permissible form. Still, this form cannot be bound. In Malagasy1, where there is no deficient form available for first and second person pronouns, no binding is possible. This suggests that the system is unforgiving – if the language has the means to supply a deficient form, either for that pronoun itself (as in Halkomelem) or for some other pronoun in the paradigm (as for Malagasy1), then binding is not possible for the non-deficient form. In Malagasy2, however, where no deficient forms exist anywhere in the paradigm, binding is now available to all forms. While it is tempting to conclude that only languages with no syntactically deficient forms in their pronominal paradigm may allow binding of syntactically complete DPs, we now look more closely at the binding of first and second person pronouns.

This article opened with a discussion of Kratzer's (Reference Kratzer, Strolovitch and Lawson1998) zero pronouns, and we now return to her analysis and the revised version published in Kratzer (Reference Kratzer2009). For Kratzer (Reference Kratzer, Strolovitch and Lawson1998) and Déchaine and Wiltschko (Reference Déchaine and Wiltschko2002), there is an important distinction between first and second person pronouns on the one hand, and third person pronouns on the other. Only the latter can be bound variables. Rullmann (Reference Rullmann2004), however, points out contexts where first and second person pronouns can, in fact, be bound variables. We were able to replicate Rullmann's findings in Malagasy2, as illustrated in (40) and (41).

The example in (40) shows ‘split binding’, where the first person plural pronoun izahay is bound by the third person quantifier ny vehivavy rehetra but also by the first person singular -ko. Here, the pronoun acts like a variable that ranges over pairs: the speaker and one of the women that the speaker married (see Rullmann Reference Rullmann2004 for discussion of the English data). Example (41) is modeled after (Partee (Reference Partee, Wiltshire, Graczyk and Music1989: note 3).

Rullmann's findings, among others, led to Kratzer's (Reference Kratzer2009) revised analysis, allowing variable binding of indexical pronouns. What is important for the present article is the shift in the empirical landscape. It is now recognized that while bound readings for first and second person pronouns are rare, careful data work has exposed cases where such binding is possible. We can therefore ask whether the same might hold true in Malagasy. That is, perhaps speakers of Malagasy1, given the right contexts, would accept bound variable readings of first and second pronouns, much as our speakers of Malagasy2 do. If that were the case, then the link between the presence of number and variable binding proposed by Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona (Reference Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona1999) would no longer hold. Speakers of Malagasy1 would still maintain a distinction between syntactically deficient pronouns (those lacking NumP) and syntactically complete pronouns, but this deficiency would only correlate with the restriction on human referents and the possibility of local (intra-clausal) binding. We leave this question for future research.

6. Conclusion

Malagasy pronouns are morphologically and syntactically rich, and appear ripe for a syntactic decomposition analysis. At the same time, we have argued that there are no syntactically deficient pronouns in one variety of Malagasy (Malagasy2). We have also shown that all pronouns in this variety can be bound variables, despite being syntactically complete. This raises the question of when syntactically complete pronouns may be bound – are there any universal restrictions? Our data suggest that if a language has deficient pronouns, these pronouns will be the ones used in bound variable contexts, but if a language lacks deficient pronouns, binding is unrestricted. This conclusion then raises the question of how to analyze binding. One helpful suggestion from Kratzer (Reference Kratzer, Strolovitch and Lawson1998: 190) is that context-shifting lambda-operators bind pronouns by shifting values for first and second person features, but we leave this task to the semanticists.