Trying to understand the factors that play a role in democratization processes has been, and remains, one of the central concerns of the social sciences, and the modernization thesis has been, by and large, the dominant paradigm in this regard. According to this thesis, economic development positively correlates with the likelihood of a democratic regime.Footnote 1 The limitations of this thesis, which regards democratization as a direct function of economic modernization, have been recently exposed by the case of China, the growth of populist rhetoric in Europe and the United States, and the proliferation of anti-racist protest movements worldwide. As a result, democratization studies tend today to incorporate slower and less obvious factors of change, such as culture, in the analysis of the complex processes that foster or hamper transitions towards/away from democracy.Footnote 2

In Spain, the institutional framing of democracy after Franco's death in 1975 was based on a pact between the Francoist reformist elite and opposition parties. In recent years, however, research has begun to question the hegemonic narrative about this process. This narrative presents the transition as a seamless process, conducted with intelligence and responsibility by a group of politicians who determined (from above) the pace, stages, and milestones in the hazardous road to democracy. This version of the transition excluded other key actors of change (from below) from the political arena: feminist and local activism; labour and student protest; and, more broadly, any expression produced and disseminated outside the channels of ‘official culture’.Footnote 3

In line with this new trend, this article explores how music was used to express ways to imagine democracy and participate, more generally, in the social mobilization for liberty and equality in the final years of the dictatorship and its immediate aftermath. I shall analyse two case studies: a large-scale experimental art festival held in the streets of Pamplona in 1972 and a grassroots musical collective created in 1973 on the initiative of the composer Llorenç Barber. These examples will illustrate the role of musicians as producers of models of democracy in 1970s Spain. In the words of Robert Adlington and Esteban Buch:

democracy doesn't pre-exist its myriad invented forms, but rather is imagined, equally by politicians, public, and actors in the public domain … In turning to democratic analogies for their practice, [musicians] become participants in this process of imagining: their work makes claims for the virtues of particular models … As such, [they] participate directly in the political debate, as much as politicians do when they lay claim to the ‘true’ values of democracy, or when members of the public contest those assertions with definitions of their own.Footnote 4

The transition to democracy in Spain exemplified these debates, for it was characterized by a complex struggle for the very definition of ‘democracia’.Footnote 5 According to the Francoist politician Tomás Garicano Goñi in 1976: ‘It is pretty much unanimous opinion that we must democratise our politics, but I am not so sure that we all agree on the meaning of “democracy”’.Footnote 6

A laboratory for democracy?

Between 26 June and 3 July 1972, barely a few days before the world-famous festival of San Fermín, the capital of Navarre held the Encuentros de Pamplona, an experimental art festival that attracted over 350 artists from Spain and abroad. They operated in such fields as conceptual art, happening, video art, sound poetry, and aleatory, electroacoustic, and minimalist music. All these were aesthetic trends with few followers in 1970s Spain, and they had never been displayed together in such a scale. Focusing on music, we may note the participation of a remarkable roster of prestigious international artists including John Cage, Sylvano Bussotti, David Tudor, Luc Ferrari, and Steve Reich.Footnote 7 The festival was organized by the plastic artist José Luis de Alexanco and the composer Luis de Pablo, founder of Alea, the first studio for electroacoustic music in Spain. Both artists had the economic support of Juan Huarte, member of a powerful family that owned an industrial conglomerate formed by over thirty companies. Huarte was a major sponsor of contemporary art initiatives – including de Pablo's electroacoustic studio – and this earned his family the nickname ‘Medicis of Navarre’. In fact, according to Huarte, the Encuentros were conceived as a personal gift to the city of his birth.Footnote 8 In consequence, the events were free of charge and were mostly celebrated in the street (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Composers Francisco Guerrero, Antonio Agúndez, and Carlos Cruz de Castro in an improvised performance at the Encuentros de Pamplona. © Eduardo Momeñe. Reproduced with kind permission of the author.

The objective of this appropriation of public space was to find new ways to interact with the audience. The text that presented the festival claimed:

[we would like] one of the main features of the Encuentros … to be, on the one hand, for the so-called audience to be able – we are tempted to say compelled – to participate in the artistic action from much closer than is generally the case, inhabiting it differently; on the other, the logical consequence of the foregoing, to push the creator in front of an audience that is much less passive than usual.Footnote 9

The organizers went on to praise the ‘long civil traditions’ of the inhabitants of the city, something that was reflected, in their opinion, in the popular character of the San Fermín festival.

Owing to this participatory dimension, the Encuentros de Pamplona festival has recently been celebrated as a laboratory of the upcoming democracy, certainly a useful perspective when locating this event within the sociopolitical context of the late Franco era.Footnote 10 However, this interpretation pays insufficient attention to the strong tensions that arose during the Encuentros. Indeed, the festival was an extremely turbulent event. Political movements, on both the left and the right, opposed it. The far-right distributed pamphlets in the street, threatening to assault the artists, something that, as far as I know, did not actually happen. The Left, organized around the Spanish Communist Party – the Francoist clandestine movement par excellence – attacked the festival as a political manoeuvre of the elite and regarded its celebration as politically counter-productive.Footnote 11 There is little doubt that the involvement of the Huarte family was one of the main reasons behind the Left's opposition. The ‘Medicis of Navarre’ were not politically neutral. Throughout their career, these industrialists had kept close links with the regime, being awarded numerous contracts for the construction of public buildings, which turned them into Navarre's main economic powerhouse and one of the leading industrial groups in Spain. One of these projects, which is highly symbolic of the complicity of the Huartes with Francoism, was the construction of the gigantic cross that presides over the Valle de los Caídos, the monument that Franco had built to glorify the Francoist dead during the Civil War; the monument was built by political prisoners kept in inhuman conditions, and from 1975 to 2019 it was also Franco's mausoleum.

The most hostile reaction, however, was that of armed Basque nationalist and separatist group ETA, which tried to sabotage the celebration of the Encuentros by exploding two bombs – one by the monument to General Sanjurjo, one of the officers involved in the July 1936 coup that triggered the Civil War, which was situated barely a few metres from a hotel where some of the festival participants were hosted; the other under a vehicle parked outside the Civil Governor's office. Although the festival went ahead, it was gravely affected by these events, which had created a widespread atmosphere of mistrust and anxiety (on the second day, the police stormed the morning screening of experimental cinema after a false bomb threat).Footnote 12 ETA distributed pamphlets in the streets during the event and issued a statement to argue that the festival was an expression of bourgeois elitism and the dominant class, who concealed themselves behind the veil of avant-garde art.Footnote 13 They also argued that the event was funded with the money of the workers exploited in the Huarte factories and, to hammer the point home, they recalled the tense negotiations through which the workers of Imenasa – one of the Huartes’ many companies – were at the time pushing for a pay rise. These negotiations eventually ended with a 45-day strike and one of the main episodes of mobilization in the so-called ‘Navarre's hot autumn’ (in reference to events in Italy in 1969).Footnote 14 In addition, ETA claimed that the inclusion of the exhibit ‘Arte Vasco Actual’ in the Encuentros – the exhibit presented a broad panorama of Basque art with works by artists belonging to three different generations – was hypocritical:

After totally oppressing our culture, now the Repressive State loudly proclaims the excellence of Basque culture and how nice the Basque people are. The oligarchy and its tool, the Spanish State, aware of the danger that our culture poses for them, tries now to turn it into a wheel in their machinery, turning it into a harmless toy at their service and depriving it of all revolutionary content.Footnote 15

In this way, ETA labelled the organizers as ‘lackeys of Power’ and the Basque artists taking part in the exhibit as ‘puppets in the hands of the State’, especially those that regarded themselves as revolutionaries, because, according to ETA, they only tried to deceive the people, rendering the bourgeois strategy more effective.

However, despite ETA's criticism, the artists who participated in the exhibit were not devoid of critical thought. They were the first to publicly state their reservations, as they were concerned that the regime might try to take over the event for propaganda purposes, as had happened with the international biennale that had brought the plastic artists Chillida, Oteiza, and Tàpies to prominence.Footnote 16 In a meeting held three months before the Encuentros, some of these Basque artists discussed the possible instrumentalization of the festival, of the event being used to present a front of cultural diversity and tolerance and thus conceal the true authoritarian character of the regime. They also lamented that the programme, which had been published in English, French, German, and Spanish, was not available in the Basque language.Footnote 17 Finally, the artists expressed their misgivings about the aesthetics chosen by the organizers: ‘In the hands of exalted elitism, the term research has acquired a magic, fetishist and mystifying tone. Along with “Avant-garde”, it has become the abode of snobbism and a step-ladder for upstarts.’Footnote 18 Despite these reservations, the Basque artists invited to the exhibit decided to take part in the festival with the aim, in the words of the painter and sculptor Agustín Ibarrola, of ‘turning the Encuentros into a sort of democratic assembly’.Footnote 19 Rather than the institutional expression of democratic practices, there is little doubt that Ibarrola was referring to moral values and ideas generally attached to democracy, such as freedom of speech, acknowledgement of differences, and self-determination of the people. In this way, Ibarrola invoked the first part of John Dewey's distinction between ‘democracy as a social idea and political democracy as a system of government’,Footnote 20 a not uncommon attitude among musicians, according to Robert Adlington and Esteban Buch:

Musical practice invites comparison with democracy by virtue of the central position it gives to such social values as expression, listening, collaboration, negotiation, compromise, trust, sympathy and solidarity. Here we should remind ourselves that while political science is undoubtedly valuable when it comes to discussing democracy in music, many musicians’ conceptualizing of the democratic aspects of their activities have relied on common-sense definitions, rather than the distinctions and nuances that have preoccupied theorists.Footnote 21

Ibarrola's project, however, could not come to fruition. The setup of the exhibition ‘Arte Vasco Actual’ was very different to the rest of the Encuentros. In terms of contents, it involved a traditional exhibition, displaying painting and sculpture, whereas the rest of the events in the festival were action-based and tried to escape classic genres, including through the use of new technologies such as video and computers. These differences were made even more apparent with the choice of venue for the Basque exhibition, the Museum of Navarre, which was situated far from the other events, both physically and symbolically. In addition, the exhibition was the victim of official censorship, when the day after the inauguration Dionisio Blanco's painting El Proceso de Burgos was taken off the wall. The title refers to a court martial held against sixteen members of ETA in Burgos in December 1970: the court sentenced six of the defendants to the death penalty – which were eventually commuted into prison sentences – leading to the protest of national and international personalities and institutions, as well as triggering a widespread process of public contestation. Dionisio Blanco's painting depicts six faceless persons behind bars in the lower area, the faceless head and hands of another person in front of two microphones in the top centre, and around it the silhouette and empty banners of a street protest alongside police forces violently repressing the demonstration (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Dionisio Blanco, El Proceso de Burgos, 1970–1. Oil painting, Artium de Álava, Vitoria-Gasteiz.

The exhibition's curator, Santiago Amón, explained that this act of censorship was due to the work's explicitly political nature, claiming that the painting had been removed to prevent the authorities from intervening and Dionisio Blanco from being punished. In solidarity with Blanco and in protest against this decision, Agustín Ibarrola, Martín Callejo ‘Arri’, and Fernando Mirantes decided to withdraw their own works.

This was not, however, the only act of censorship affecting the Encuentros. On the fourth day of the festival, in the giant pneumatic dome designed by the architect José Miguel Prada Poole and used as a venue for some of the events, an impromptu debate began. Forming a circle (Figure 3), over 250 people sat on the ground and, with the aid of a carboard megaphone, spoke for an hour about such notions as the concept of art, its social dimensions and its links with the ruling classes and authoritarianism.Footnote 22 The event fell outside the official programme of talks programmed by the organizers, in which a lecture was generally followed by a discussion with the artist in question.

Figure 3 Impromptu debate inside the pneumatic dome designed by the architect José Miguel Prada Poole. © Francisco Zubieta Vidaurre. Reproduced with kind permission of the Archivo Municipal de Pamplona / Iruñeko Udal Artxiboa.

The improvised debate was interrupted by the sudden arrival of Juan Huarte, who turned up at the dome and told those present that the meeting was not authorized and must be disbanded. In order to bring the debate to an end, Huarte ordered electronic music to be played inside the dome at top volume, so that the participants had no other option but leave.Footnote 23 After hearing about these events, the author of the musical piece, Josep Maria Mestres Quadreny, a key figure in the Spanish musical avant-garde and a participant in the Encuentros, declared himself appalled by the fact that his music had been used to ‘prevent a debate inside the dome’.Footnote 24 The composer and other participants signed a statement to express their disagreement with the way the festival was unfolding and the coercive measures deployed by Huarte. According to the signatories, Huarte's attitude betrayed a ‘purpose to manipulate’ the festival, which undermined the event's value as an innovative cultural event. The avant-garde art being presented had lost its authenticity and had been turned into an ‘empty shell’, a ‘decorative superstructure’ to be politically instrumentalized ‘like almost every time in the past when art happened under the protection of a sponsor’.Footnote 25

Soon after the Encuentros, Huarte claimed in an interview that his decision to stop the improvised meeting at the dome was intended to prevent it from becoming a ‘political rally’.Footnote 26 Concerning the criticism and the acts of boycott, he said: ‘I find that sabotaging this [event], knowing that it will attract so much attention, is anti-intellectual, anti-democratic and anti-everything. Because real politics is about organizing events like this one.’Footnote 27 He admitted that the festival aimed to reject the ‘political idea that says that no Encuentros can be had because the regime does not let important things happen’.Footnote 28 In the context of late Francoism, it was not unexpected that someone like Huarte, close to the regime and against freedom of speech and assembly – as his authoritarian reaction to the above-mentioned impromptu debate demonstrates – should present himself as a ‘democrat’. In fact, the regime regularly used the word ‘democracy’ to refer to changes introduced during the period of economic growth of the 1960s. By coining the expression ‘organic democracy’, the regime tried to portray itself as a participatory system, a political model in which popular representation was not achieved through individual voting, but through ‘natural’ relationships, such as the family, the municipality, and the trade union.Footnote 29 Using a language that was in principle foreign to it, the Francoist political class adopted a notion of ‘democracy’ that was devoid of its universally accepted features: popular sovereignty, representative institutions, freedom.

The regime did not hesitate to use the concept of freedom in its propaganda about the Encuentros. The narrator of the TV show Galería presented, with ill-concealed pride, the American composer John Cage as we walked through Pamplona with the sentence: ‘This is John Cage, freely walking the streets of Pamplona.’Footnote 30 Cage was one of the most prominent attractions of the Encuentros, and the organizers even claimed that the festival in its entirety was a tribute to him, on his 60th birthday (Figure 4).

Figure 4 (Colour online) Poster for the concert by John Cage and David Tudor at the Encuentros de Pamplona. © José Luis de Alexanco. Reproduced with kind permission of the author.

Cage was the subject of numerous articles, in which he was presented as the leading figure in experimental music; these articles highlighted his artistic freedom, social commitment, and love for nature.Footnote 31 However, in an interview carried out during the Encuentros, the composer did not seem particularly concerned about the Spanish sociopolitical context, in which so many basic freedoms were still being curtailed. When the journalist asked whether he was comfortable performing under Franco's regime, Cage responded: ‘an artist who lives in Nixon's America … why could he not work in Franco's Spain?’Footnote 32 In this instance, Cage played part of his 62 Mesostics re Merce Cunningham, while David Tudor simultaneously interpreted a piece of electronic music. In his interviews with the local press, Cage declared:

Previous times that I have been to Spain with David Tudor, he came to interpret my music. Now we come as independent authors. We shall both interpret our own music, but simultaneously. The idea is express the practicability of anarchy, because none says what the other must do …

On the one hand, … we have many people worried about power and money; on the other, young people (you can see that), which have realised that if we carry on like this, we shall destroy ourselves and even nature itself. These young people know that a major change is on its way, and it will itself bring it about… The reason for this, is that when world superpopulation increases, most of the population will be young. It is likely that one day most of the population will be under fifteen …

This will be the moment of the revolution.Footnote 33

Asked his opinion about the Encuentros, he said: ‘I like it that all events were free, that everyone could attend. I know that problems have occurred, but I am not interested in politics or protest. I am interested in society, and I would like social change, but I do not want to commit to a protest action.’Footnote 34 Cage's words show that in late Francoist Spain it was possible for a renowned foreign artist to celebrate anarchy and speak of revolution, as long as they did not get involved in politics. For any sceptical observer, Cage's visit to Spain ran counter to the myth of emancipation with which his music was often associated.Footnote 35 The freedom inherent in his music was either compatible with Francoism or totally empty of political meaning. In all fairness, a third possibility exists: that these gestures concealed an act of resistance too subtle to be perceived. However, in the absence of objective evidence to support it, adopting this interpretation requires a leap of faith.

But not everything that happened in the Encuentros was under Juan Huarte's close gaze. The artists of Equipo Crónica, a leading group in Spanish pop-art, made one hundred life-size papier-mâché spectators for the cinema theatre, which were called ‘Spectator of spectators’ and which could not fail to recall the Brigada Político Social, Franco's secret police and main agent of urban repression (Figure 5).Footnote 36 The idea was for these dummies to be present for the duration of the festival. Although not initially planned, the members of the Equipo Crónica decided to feature the ‘Spectator of spectators’ by placing them among the audience of Luc Ferrari and Jean Serge Breton's multimedia show Allo! Ici la Terre. The work consisted of a concert of electroacoustic music accompanied by an instrumental ensemble and a play of lights and projections of images related, generically, to the planet earth. During the show, the artists encouraged the audience to participate in the event, inviting them to join the stage and turn their bodies into a screen for the projections. However, during the performance, the ‘Spectators of spectators’ became victims of the audience's anger: ‘The furious audience beat them, one had their throat slit. One was hung, almost all of them lost their heads … In short, they were beaten up, kicked, tossed, walked around, kissed and finally piled up by the caretakers, who rescued them one by one.’Footnote 37 The audience engaged with Luc Ferrari and Jean Serge Breton's work by indulging in a cathartic act of destruction, which could be a reflection of the hunger for freedom of a society that had been for too long under dictatorship (Figure 6).

Figure 5 (Colour online) The ‘Spectator of spectators’.

Figure 6 Luc Ferrari and Jean Serge Breton's multimedia show Allo! Ici la Terre at the Encuentros de Pamplona. © Demetrio Enrique Brisset. Reproduced with kind permission of the author.

The members of Equipo Crónica were delighted with the audience's reaction. They may even have been surprised by it. A month earlier, in a conversation about the festival and its critics with Pere Portabella – a member of the Communist Party and a key figure in Catalonian alternative cinema, who had publicly declined the invitation to take part in the Encuentros for political reasons – they admitted that ‘some of our early enthusiasm is gone. Now we cannot see this cultural expression having major political or ideological consequences’.Footnote 38

Equipo Crónica's fears seemed to have been confirmed. The restrictions imposed by Juan Huarte undermined the event's emancipatory potential. For this reason, rather than a laboratory in which to experiment artistically with the idea of democracy, the Encuentros became a battlefield in which opposing and incompatible concepts of democracy were pitched against one another. It is perhaps of little surprise then that, although originally conceived as a biennale, the festival was celebrated only once.

Ephemeral communities

Asked about the Encuentros soon after they were over, composer Josep Maria Mestres Quadreny responded:

About Encuentros [literally, ‘meetings’], first we must say that the name was ill-chosen. What we have witnessed is encontronazos [i.e. clashes]. Those of us who have met have done so by chance; that is, people I already knew I have bumped into; those I did not know, I have not met. I thought at first that this would be interesting for participants, but owing to restrictions to communication it was not so.Footnote 39

Music as a medium to facilitate encounters was part of Mestres Quadreny's compositional ideology. In 1973, he wrote Self-Service, for recorder and small percussion, ad libitum in duration and for any type of interpreter. The score adopts four large fragments of Barcelona's city map, conceived for different instrumental ensembles. The streets are subdivided into randomly allocated squares, in whose interior a number designates the duration (in seconds) and intensity (based on font size) of sound. Other signs mark such parameters as note changes, type of percussion, and holding up of sounds. Each interpreter can choose their path across the score, as though it was a virtual and sonorous walk through the streets of Barcelona (Figure 7).

Figure 7 Excerpt from Mestres Quadreny's Self-Service.

The work was premiered on 22 May 1973 in the exhibition hall of the Colegio de Arquitectos de Barcelona. The building is strategically located in the cathedral square, and was built, according to its author, Xavier Busquets, to revitalize this sector of the city. The composer gave the audience approximately 30 instruments – recorders and a variety of small percussion instruments – in four groups, to use as they pleased, just as the title of the work suggests.Footnote 40 The action began with the entrance of the first audience-interpreter, and ended when the last left.Footnote 41 The sources disagree concerning the number of participants and the duration of the event. Lluís Gàsser claims that over a thousand people passed through in a constant stream in the course of three hours and that the organizers, in order to bring the event to an end, switched the hall's lights off, despite which the participants carried on playing in the dark for another ten minutes.Footnote 42 Xavier Montsalvatge writes that he had to leave ‘in the middle of the maremagnum, which I believe went on for over an hour’.Footnote 43 Mestres Quadreny himself gives different figures: in one text he writes about 2,000 people or so, playing for two hours,Footnote 44 and in another about 1,000 people and three hours.Footnote 45 The profile of participants was, according to El Correo Catalán, ‘pre-eminently young and enthusiastic’, and they participated in the creation of a ‘disquieting, obsessive sonorous world’.Footnote 46 Montsalvatge described the participants as ‘young, unconventional, rebellious and well-meaning’.Footnote 47

This apparent need to present the participants of the event in moral terms was perhaps due to the fact that Self-Service was premiered under police supervision. On the ground, however, the efficiency of this disciplinary and surveillance dispositf (to borrow a Foucaldian term) was compromised by the public overflow that presided the event.Footnote 48 The large windows of the exhibit hall channelled the communication between the inside of the hall and the street, leading to a heterogenous continuum of hard-to-pin-down individuals, blurring the boundaries between the private and the public sphere, and making police surveillance much harder. In addition, the collective performance and the multiplicity of musical foci created a new sonorous space, directionless and of unknown duration, generated by audience-interpreters linked in a non-hierarchical relationship. The fact that no consensus exists concerning the event's attendance numbers and duration is illustrative of the breaking down of the dispositif, which, according to Foucault, endeavours to enforce norms through docility and obedience, in the name of utility; time and space are functionally and hierarchically arranged, under the power-bestowed label of efficiency. Perhaps this premiere helped Mestres Quadreny to erase the bad memory of the Encuentros de Pamplona.

Public space was a disputed asset during the years of transition to democracy, including in the years immediately following Franco's death. Despite the restrictions imposed by Interior Minister Manuel Fraga Iribarne, his famous sentence ‘the streets are mine’ – uttered in 1976 after the trade unions and left-wing opposition parties tried to celebrate 1 May – and violent police repression, which caused nearly 200 deaths,Footnote 49 civil society claimed their right to take to the streets. Publications such as Ajoblanco, a counter-cultural magazine that did an outstanding job of pushing the limits of the gradually expanding freedoms, vindicated collective public expressions and argued that ‘a state that curtails or channels discussion in its squares is a state that silences its people and wants to stand on the mute words of the holders of power’.Footnote 50

In line with this demand, musical creations conceived for the public space began proliferating. Like Quadreny's Self-Service, many also enrolled in the participation of the audience and the context. One example of this is Sambori (1978), written by the Valencian composer Llorenç Barber, in which musicians turned random and everyday actions (e.g., the passing of pedestrians, cars and animals) within a ‘playing field’ marked with chalk into sound. When the work was performed in an enclosed space, it was the audience, coming in and out of the playing field, deliberately or not, that guided the musicians. The composer's instructions were as follows:

Z.- In an open (street, square, park, beach, etc.) or closed space (station, market, metro station, hall, etc.) draw (with chalk or something like that) an area divided into more or less equal areas, which are numbered.

Y.- The enclosed area becomes a ‘playing field’. It works like a pentagram in which random (passing of pedestrians, cars, animals, bicycles, etc.) or deliberate (games, mimes, dance, gymnastics, theatre, etc.) events are drawn.

X.- An indeterminate number of interpreters will translate things happening inside the ‘playing field’ into music, following a set of norms to be established beforehand, so the space becomes the score.

W.- An example code: assign an area a note, rhythm, melody, a combination thereof, other things. Codes will be different for each interpreter of group of interpreters.

V.- The code will adapt to the space chosen (background noise, number of people, vehicles and animals, etc.) and instruments used (found, invented, conventional).

T.- Interpreters will read what happens in the ‘playing field’; if several things are happening at once, they can focus in one area, ignoring the others.

S.- When indoors, the ‘work’ will begin when the first ‘spectator-composer’ enters the ‘playing field’ and will end when the last leaves. The audience is the score.

R.- During the performance, it is not forbidden for an interpreter to enter the ‘playing field’ with their instrument (along with dancers and mimes that draw music in it, knowing the code or otherwise), and become part of the score for themselves and the other interpreters.Footnote 51

Inspired by English-speaking minimalists such as La Monte Young, Michael Nyman and Gavin Bryars, and the collective improvisation proposals put forth by Cornelius Cardew, as well as by the open universe of Cage and Zaj (considered the Spanish Fluxists),Footnote 52 Sambori illustrated Barber's interest in creating a participative form of art outside the typical venues used for classical music.Footnote 53 The work premiered in 1978 at the festival Music/Context, in London, organized by the London Musicians Collective. Two versions were performed: one for cars and another one for birds. Soon afterwards, the group Actum interpreted it in the philosophy faculty of the University of Valencia, and Galería Cànem, in Castellón.

The group Actum was founded by Barber and some conservatory classmates in Valencia in 1973; these included the brothers Emilio and Francisco Baró and Perfecto García Chornet (piano students at the conservatory); Salvador Porter and Liberto Benet (violinist and bassoonist, respectively, at the Valencia Symphonic Orchestra); and the philologist Antoni Tordera, among others.Footnote 54 As the Latin name indicates, the group's aim was to trigger action (actum can be translated as ‘acting’, ‘act’, ‘action’), in opposition to formalist conceptualizations of art. According to Barber:

For ACTUM, music is not a commodity to be sold, nor a form to impose ourselves, like Faustus, over the astonished audience. For ACTUM music is, simultaneously:

A. Act as a celebration of the body, self-pleasure vindicating pleasure for all, regardless of class, race or nation …

B. An act that vindicates life, an act that transcends the claustrophobic concert hall (sonorous pantheon of the bourgeoisie), leaps into the pit, takes the gag off the spectator and takes them for a walk through the city.Footnote 55

The group became the springboard for a theatre company (Actum-teatre) directed by Antoni Tordera; an instrumental ensemble (which, in addition to the group members, was occasionally joined by percussionists Juan García Iborra and Xavier Benet, composers Carles Santos and Juan Hidalgo, flute-player and composer Bárbara Held, and soprano Esperanza Abad, who specialized in contemporary music, as well as people related to plastic arts and the theatre); a laboratory of electronic music and synthesizers (one analytical and one synthetic), manufactured by Josep Lluís Berenguer; and an underground printing press that distributed photocopies – which were later bound in a characteristic rough brown paper – with the group's music, following word-of-mouth demand (Figure 8). The group was active between 1973 and 1983, and according to Alberto González Lapuente it was the ‘longest and most rewarding example of self-management’ among young musicians in post-Francoist Spain.Footnote 56

Figure 8 Actum's printing press logo (Llorenç Barber's private archive). Reproduced with kind permission of the owner.

One of the group's signs of identity was the association of artists from different areas, and of professionals and amateurs. According to Barber: ‘In terms of skill, there was a wide range, from zero to virtuosity.’Footnote 57 In their performances, they invited the audience, largely formed by artists and university students, to join the interpreters: ‘In this way, Actum grew, and sometimes there were up to 20 or 30 people on stage, playing together.’Footnote 58 Pursuing this end, many of Actum's musical proposals followed a minimalist aesthetic, using intentionally non-atonal and diatonic sounds. They were, for the most part, simple in terms of both composition and interpretation. To help musicians and non-musicians to share open and rich sonorous experiences, an intuitive, almost naïve musical graphism was adopted.Footnote 59 Sambori, described earlier, was a good example. Love Story for yu [sic] (1975), composed by Barber in cooperation with the pianist María Escribano, comprises forty-nine cells or squares that can be ‘traced’ following various routes, according to a detailed set of instructions; the musical material in each cell combines several notation systems, including conventional musical notation, drawings, onomatopoeias, and open signs, to express everyday sounds and gestures. Cómic by Josep Lluís Berenguer used drawings and designs to trigger an intuitive response from the performers (Figure 9).

Figure 9 (Colour online) Cómic by Josep Lluís Berenguer (Llorenç Barber's private archive). Reproduced with kind permission of the owner.

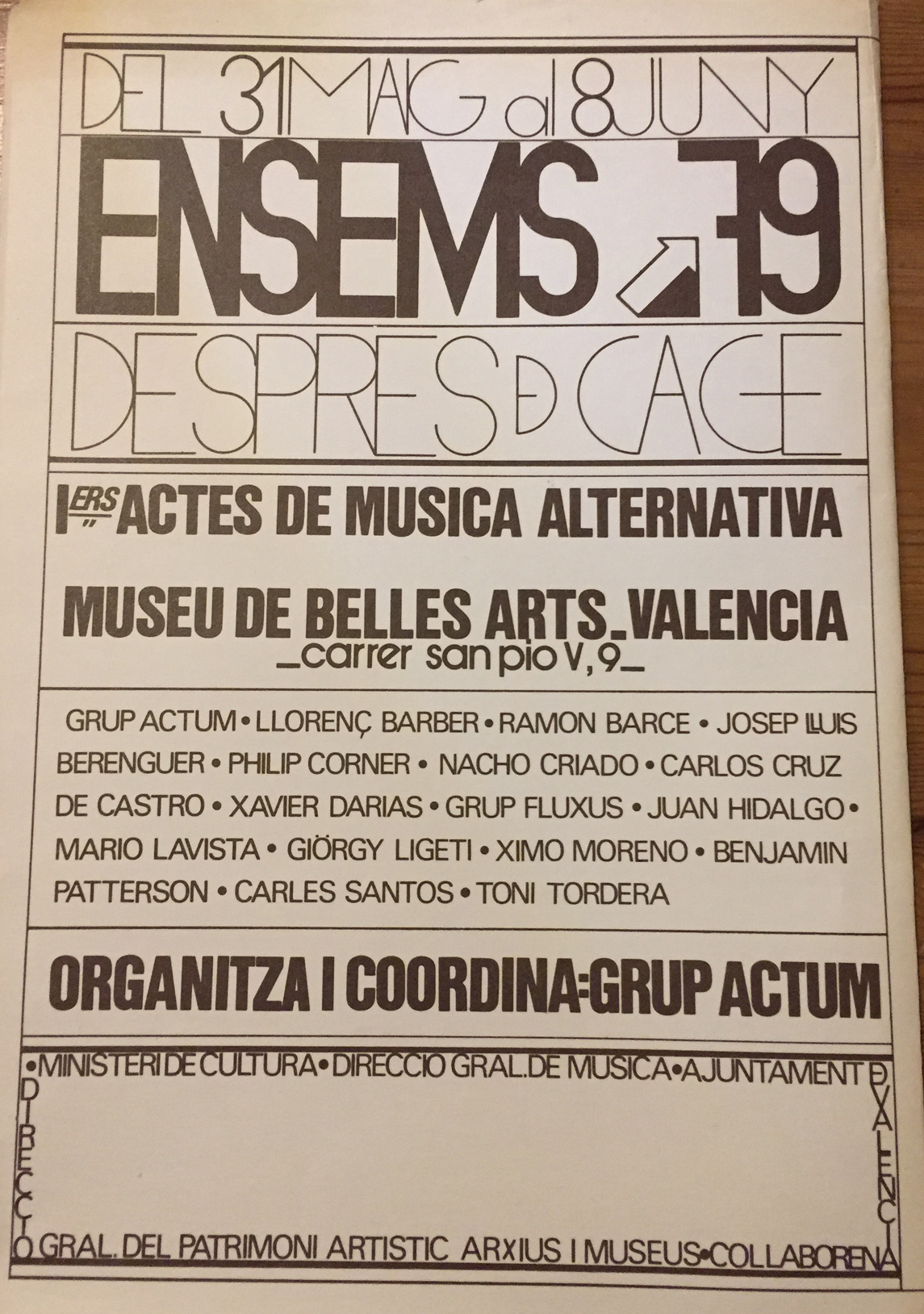

The participation of audiences also involved voting. In the first Festival Ensems, organized by Actum in 1979, the American artist Philip Corner (part of the Fluxus movement) interpreted the piece Democracy in Action, for all interpreters and a voting public (Figures 10 and 11). In this piece, Corner plays the same keys repeatedly, until the audience decides that he needs to stop. Every two minutes, the audience votes whether Corner should continue or not.

Figure 10 (Colour online) Poster of the first Ensems festival (Llorenç Barber's private archive). Reproduced with kind permission of the owner.

Figure 11 (Colour online) Outline of Philip Corner's performance (Llorenç Barber's private archive). Reproduced with kind permission of the owner.

Robert Adlington has noted the parallel between pieces that include a voting audience – such as the opera Votre Faust, written by Henri Pousseur in Paris in 1968 – and modern forms of electoral democracy: ‘In these instances … although the audience has the freedom to decide the piece's final shape, the fact is that it is only given a limited range of pre-established choices.’Footnote 60 Following Adlington's parallel, we should consider Corner's work in the context of the numerous elections held in Spain between Franco's death in 1975 and the celebration of Festival Ensems in 1979.

In 1976, a referendum was held to approve or reject Adolfo Suárez's bill of political reform, which had already been passed by parliament. The aim of the bill was to put an end to the dictatorship and turn Spain into a constitutional monarchy, with a parliamentary system based on representative democracy. The ‘yes’ to the bill was a personal victory for Suárez against those who defended a more radical rupture, led by the Socialist Party and the (still illegal) Communist Party, which asked voters to abstain. With the referenda held during Francoism, in which voting was mandatory and 95 per cent of votes cast were in support of the government's position, left-wing parties used abstention as a form of political representation, of resistance to the institutional representation model. In 1977, in the first democratic elections held in Spain since 1936, the political parties finally abandoned this tactic.Footnote 61

However, as pointed out by Germán Labrador in his analysis of Spanish counter-culture during the 1970s, abstention was never abandoned as a civil political practice. Inspired by anarchist and libertarian ideas, abstention was ideologized as a rejection of market democracy and of a representative structure shaped by Franco's institutional heirs.Footnote 62 Labrador illustrates many expressions of this rejection, including graffities, murals, and other traces of what Labrador refers to as ‘the citizen archive of the period’.Footnote 63 For instance, in a graffito that alluded to the 1976 referendum (Figure 12), a TV set broadcasts guidelines that the citizens follow to cast their votes in a toilet (‘please, flush after voting’). Those who do not comply are chased by police (the ‘guardians of democracy with a ballot box and a rifle, in a crusade against the infidel’).Footnote 64

Figure 12 (Colour online) Reproduced from Equipo Diorama, Pintadas del referéndum (Madrid Equipo Diorama, 1977).

It is worth recalling that one of the novelties introduced for the 1976 referendum was the massive use of the media to campaign for ‘yes’ to the bill. Adolfo Suárez, prime minister and main promoter of the Bill, had been the head of Radiotelevisión Española, and was very aware of the power of advertising in the mass media. Some slogans were used (‘Your vote is your voice’; ‘If you want democracy, vote’; ‘Be informed, and vote’), and the most successful of these, ‘Speak, people’, was used in a TV spot with the song ‘Habla, pueblo, habla’, by the band Vino Tinto, sounding in the background. This song has become one of the main musical emblems of the Spanish transition to democracy.Footnote 65

According to Labrador, the discrediting of the representative system that the graffiti expressed, and the introduction of representative ruptures within the system occurred in parallel with the exploration of the limits of democratic representation through the exercise of the rights to association, expression, and reunion. With Actum, however, these practices were presented as not entirely incompatible. Without reducing democracy to mere voting, works such as Philip Corner's Democracy in Action were one of a number of ways in which the members of the group experimented musically with democracy, alongside the experience of self-management, the encounter between professional and amateur musicians and performing in public spaces.

In exploring such specialized forms of collective action, music-making was presented as a broader model for the exercise of political sovereignty. John Dewey argues that democracy ‘is the idea of community life itself’:Footnote 66

Wherever there is conjoint activity whose consequences are appreciated as good by all singular persons who take part in it, and where the realization of the good is such as to effect an energetic desire and effort to sustain it in being just because it is a good shared by all, there is in so far a community. The clear consciousness of a communal life, in all its implications, constitutes the idea of democracy.Footnote 67

This conjoint activity, free and egalitarian, is a social and political ideal that features in many musical approaches to the ideal of democracy. And this ‘communal life’ might very well include the audience, seen on its own terms as an autonomous actor within music-making situations. With a crucial qualification, though: as Estelle Zhong Mengual has observed in her book on the British Participatory Art movement, Dewey never associates the notion of community with that of identity.Footnote 68 In that sense, he is very far from adhering to the identity politics of communitarianism, with its emphasis on stable ethnic, religious, or distinctive cultural traits. On the contrary, she argues, Dewey's community is itself a consequence of ‘conjoint activity’, one whose precarious identity arises solely from the very participation in the event. In the participatory works analysed by Zhong Mengual and in those carried out by Actum, the reactions of the public to the propositions by the artists are part of the works themselves, not just their reception. In those ephemeral communities, all participants are equally entitled to agency.

However, Actum's performances also illustrated the difficulties attached to fully realizing this utopian ideal, this sensus communis in which each individual recognizes their full dependence on everyone else within the demos. Although Actum's commitment to collective improvisation and the involvement of the audience was rhetorically presented as a symbol of a movement towards total participation, it also overlooked the group's own identity, forged through the individual and collective attachments of its members, which clearly informed its approach to ‘collectivity’; let us recall that, for the most part, their performances attracted artists and university students. Theoreticians of democracy have argued that every democratic arrangement reflects specific interests.Footnote 69 However, they also argue that these limitations are no reason to renounce the idea; what is important, in fact, is to be ever alert to the forms of exclusion and privilege created by these specific democratic covenants. Within this horizon, there is still room for emancipatory visions that challenge received conceptualizations of democracy, as some grassroots organizations tried to do through music in 1970s Spain.