INTRODUCTION

Whether defined as a kind of moral principle, political ideal, cultural predisposition, or social practice, cosmopolitanism is often characterised by an openness towards differences, a readiness to engage with new cultural experiences, and an orientation towards the world beyond geopolitical and sociocultural borders (see inter alia Hannerz Reference Hannerz1990; Beck Reference Beck2002; Appiah Reference Appiah2006; Nussbaum Reference Nussbaum2019). This ‘citizen of the world’ figure also embodies most sociolinguistic research on cosmopolitanism, which has tended to focus on hybrid and fluid linguistic practices involving the use of global or non-local language and language variety in spoken discourses (e.g. Block Reference Block2003; Zhang Reference Zhang2005; Canagarajah Reference Canagarajah2013; De Costa Reference De Costa2014) as well as in linguistic landscapes (e.g. Seargeant Reference Seargeant and Seargeant2011; Baudinette Reference Baudinette2018; Abas Reference Abas2019), signalling an orientation away from the local.

Yet, as both Curtin (Reference Curtin2014) and Blackwood & Tufi (Reference Blackwood and Tufi2015) have convincingly demonstrated in their respective studies on the linguistic landscapes of Taiwan and the Mediterranean, there are multiple forms of cosmopolitanism, from the elite to the grassroots, from the authoritative to the transgressive, and from the distinctive to the quotidian. Furthermore, each type of cosmopolitanism is shaped by the complex interactions between global, national, regional, and local processes, and in turn, contributes to the production of locality (Appadurai Reference Appadurai and Fardon1995), ‘a location from which one views and experiences a world that one participates in crafting imaginatively’ (Rofel Reference Rofel2007:114).

Embracing this multifaceted and situated view of cosmopolitanism, this article examines the interaction between semiotic landscape and place-identity in the context of contemporary Shanghai. With a population of twenty-nine million as of 2023, Shanghai is the third most populous city in the world and often regarded as the most cosmopolitan city in China, thanks to both its semicolonial century as a Treaty Port from the 1840s as well as its ambition to become ‘an excellent global city and a modern socialist international metropolis with world influence’ (Shanghai Municipal People's Government 2018:21). Since China's market reform and entry into global economy in the late 1970s, rapid globalisation and mass migration have not only reconstructed the material and semiotic landscapes of the city (Li & Yang Reference Li and Yang2021) but also challenged the traditional language and status of Shanghainese residents and given rise to a New Shanghainese identity (Xu Reference Xu2020, Reference Xu2021). At the same time, the marketisation of economy has also shaped a post-socialist, neoliberal subjectivity characterised by material, sexual, and affective desires (Farrer Reference Farrer1998; Rofel Reference Rofel2007) and a revived cosmopolitan culture reminiscent of the Republican era (Farrer & Field Reference Farrer and Field2015).

This article examines how these changing landscapes and identities are discursively constructed and negotiated in research interviews from a larger ethnographic project conducted by the first author in Shanghai during 2018 and 2019. Drawing on interactional approaches to linguistic and semiotic landscapes (e.g. Garvin Reference Garvin, Shohamy, Ben-Rafael and Barni2010; Lou Reference Lou2016; Hayik Reference Hayik2017) and conversation analysis of place talk (e.g. Schegloff Reference Schegloff and Sudnow1972; Myers Reference Myers2006), we first identify two major competing semiotic landscapes of Shanghai: ‘Shanghai Modern’, indexing the city's semicolonial history; and ‘Global Shanghai’, indexing its contemporary development. We then examine the affective, epistemic, and relational stances (cf. Du Bois Reference Du Bois and Englebretson2007) the participants take towards these two landscapes during research interviews, which further index their divergent relationships to the city, that is, their place-identities (Proshansky, Fabian, & Kaminoff Reference Proshansky, Fabian and Kaminoff1983).

In the following section, we review recent literature on cosmopolitanism, especially in sociolinguistics, followed by a brief discussion of place talk as an interactional approach to semiotic landscape. We then present the historical and social contexts of Shanghai before the analysis of stances in the interviews. We conclude with a summary of the findings and reflect on the implications of the study considering recent challenges the city faced during the Covid-19 pandemic.

RETERRITORIALISING COSMOPOLITANISM

Tracing the development of cosmopolitanism from Diogenes the Cynic in Ancient Greece to Adam Smith, Nussbaum (Reference Nussbaum2019) writes that its focus on our common humanity beyond ethnic, national, gender, and class divisions is one of the most profound insights of Western philosophy and is still immensely relevant today. Indeed, as reviewed in Vertovec & Cohen (Reference Vertovec, Cohen, Vertovec and Cohen2002), there has been a resurgence of interest in cosmopolitanism in social and political thoughts, in response to processes and conditions such as globalisation, transnational migration, feminist movements, and climate change. However, as they note, during this cosmopolitan revival, its meaning has also become pluralised, encompassing a wide range of ideas from moral philosophy (Appiah Reference Appiah2006) and principle of democratic governance (Gilroy Reference Gilroy2005) to individual attitudes and dispositions (Hannerz Reference Hannerz1990) and sociocultural practices (Urry Reference Urry1995). While earlier studies on the topic have been critiqued for their elitist bias associated with middle- and upper-class individuals with resources for transnational migration and travels (Featherstone Reference Featherstone2002), a cosmopolitan outlook can also be fostered by what Beck (Reference Beck2002) refers to as ‘internal globalisation’ or ‘cosmopolitanisation’, that is, the construction of multiple lifeworlds within the borders of nation states. This makes it possible to account for ordinary citizens’ everyday experienced cultural ‘border-crossing’ in globalised, and often urban, milieus. This more egalitarian view has led researchers to coin terms such as ‘corner-shop cosmopolitanism’ (Wessendorf Reference Wessendorf2010), to include an evolving repertoire of intercultural competences that are cultivated during daily experiences of commonplace diversity.

At the core of these diverse conceptualisations is the shared understanding of cosmopolitanism as the opposite of nationalism and localism (Roudometof Reference Roudometof2005). In sociolinguistic research, cosmopolitanism is often indexed by the learning and use of English and its global varieties in the context of language learning and literacy development (Block Reference Block2003; Canagarajah Reference Canagarajah2013; De Costa Reference De Costa2014) or creative multilingualism in the linguistic and semiotic landscapes (Seargeant Reference Seargeant and Seargeant2011; Baudinette Reference Baudinette2018; Abas Reference Abas2019). Cosmopolitan identities can also be indexed by non-local language varieties other than English. In Zhang's (Reference Zhang2005) study of Chinese yuppies in Beijing, for instance, she identifies a supralocal variety of Mandarin which does not index any specific place but the transnational spread of popular culture from Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Singapore. Similarly, Kozminska (Reference Kozminska2020) describes a particular group of Polish migrants in the UK as ‘cosmopolitan Poles’, who typically display a distinct set of sociophonetic features diverging from ‘native’ norms.

While in these studies, cosmopolitan language practices are in general characterised by detachment from specific locales and fluidity across national, cultural, and linguistic boundaries; a few studies on cosmopolitanism in linguistic landscape, particularly Curtin (Reference Curtin2014) and Blackwood & Tufi (Reference Blackwood and Tufi2015), have called for the attention to ‘situated’ cosmopolitanism. Based on a diachronic ethnographic study in Taipei, Curtin (Reference Curtin2014) maps three types of cosmopolitanism onto its linguistic landscape: presumptive, distinctive, and transgressive, each indexed by a different set of locally salient linguistic and semiotic resources, such as pinyin romanisation of Traditional Mandarin, non-Chinese scripts, and graffiti. Furthermore, each cosmopolitan landscape also exhibits tensions between socioeconomic class, ethnopolitical allegiance, and cultural consumption. This kaleidoscopic and situated nature of cosmopolitanism is also observed by Blackwood & Tufi (Reference Blackwood and Tufi2015) in their comparative analysis of English in Italian and French cities on the Mediterranean coast.

We can thus map sociolinguistic research on cosmopolitanism briefly reviewed above onto a continuum suggested by Roudometof (Reference Roudometof2005), where cosmopolitanism and localism are not binary opposites but marked by variable degrees of attachment to place. In this article, we are particularly interested in redressing the imbalance between deterritorialisation and reterritorialisation by localising cosmopolitanism in place talk.

PLACE TALK AND INTERACTIONAL APPROACH TO SEMIOTIC LANDSCAPE

As Canagarajah (Reference Canagarajah2013:194) has demonstrated in his seminal book, linguists have much to contribute to research on cosmopolitanism, as ‘conversation is not just a useful metaphor, it is a practice’. This dialogical view treats cosmopolitanism ‘as a process, achieved and co-constructed through mutually responsive practices’ (Canagarajah Reference Canagarajah2013:195). Attending to the micro-level social interactions constituting cosmopolitan relationships also underscores their ‘rootedness’. Instead of detaching itself from the local entirely, rooted or vernacular cosmopolitanism reconfigures local spaces (Ackerman Reference Ackerman1994), creating fluid contexts in which linguistic resources take on new indexical meanings (Canagarajah Reference Canagarajah2013).

A conversational genre of particular relevance to this article is a type of discourse called place talk, namely conversations about place. It was first identified by Schegloff (Reference Schegloff and Sudnow1972:80) as ‘a set of terms each of which, by a correspondence test, is a correct way to refer to it (location)’. These conventional place formulations and reformulations were selected in relation to the location and topic of the conversation, the identities of the interlocutors, and the task-at-hand (Kitzinger, Lerner, Zinken, Wilkinson, Kevoe-Feldman, & Ellis Reference Kitzinger, Lerner, Zinken, Wilkinson, Kevoe-Feldman and Ellis2013). Place talk then provides us with an ideal empirical lens to examine individuals’ attachment to place, that is, place-identity (Proshansky et al. Reference Proshansky, Fabian and Kaminoff1983; Housley & Smith Reference Housley and Smith2011; Ilbury Reference Ilbury2022).

Place talk abounds in interactional approaches to linguistic and semiotic landscape, including walking tours (e.g. Garvin Reference Garvin, Shohamy, Ben-Rafael and Barni2010), interviews (e.g. Bock & Stroud Reference Bock, Stroud, Peck, Stroud and Willaims2018), community meetings (e.g. Lou Reference Lou2016), and photovoice projects (e.g. Hayik Reference Hayik2017). Although not always explicitly stated as such, in these studies, linguistic and semiotic landscape has essentially become a stance object (Du Bois Reference Du Bois and Englebretson2007; see also the analysis of stance and indexicality in urban planning policies in Lou Reference Lou and Pascale2013) as we demonstrate in the following analysis, but first it is necessary to present a brief historical and sociological background on the revival of cosmopolitanism in contemporary Shanghai.

SHANGHAI: THE REVIVAL OF A COSMOPOLITAN CITY

Located on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, Shanghai (lit. ‘on the sea’), a fishing village since antiquity, became a market town in 1074 and then was incorporated as a county under Songjiang Prefecture in 1292 (Danielson Reference Danielson2010). In November 1843, following the ratification of the Treaty of Nanjing after the first Opium War, it became one of the five treaty ports for its convenient trading location, which marks the beginning of the city's ‘treaty port century’ (Wasserstrom Reference Wasserstrom2008). In 1845, the local administration issued the ‘Shanghai Land Regulation’, establishing foreign settlements and concessions within the city. Shanghai was then divided into three administrative areas: the International Settlement, the French Concession, and the Chinese Section until the end of Second World War (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. International Settlement, French Concession, and Nanshi (Durand Reference Durand2009).

During the treaty port century, Shanghai developed into the most populous and modern city in China with the rapid adoption of modern modes of production, technologies, management, urban governance, and lifestyle, and it officially became a municipality in 1927. One guidebook of Shanghai published in 1934 describes the city in the following passage.

… Shanghai, the Paris of the East! Shanghai, the New York of the West! Shanghai, the most cosmopolitan city in the world, the fishing village on a mudflat which almost literally overnight became a great metropolis. Inevitable meeting place of world travellers, the habitat of people of forty-eight different nationalities, of the Orient yet Occidental, the city of glamorous night life and throbbing with activity, Shanghai offers the full composite allurement of the Far East. (Anonymous 1934:1)

With the introduction of modern facilities and infrastructure such as banks, tree-lined boulevards, gaslights, electricity, telephone, running water, automobiles and public transportations, the material living environment in foreign concessions has contributed toward Shanghai's rapid modernisation and urbanisation (Xiong Reference Xiong1999). This material matrix also fostered the flowering of a new urban culture influenced by western lifestyles such as cinemas, department stores, coffee houses, dancing halls, public parks, racing clubs, which Lee (Reference Lee1999) refers to as ‘Shanghai Modern’. From 1930 to 1945, ‘Shanghai Modern’ represents a historical period during which Western commodities, cultures, values, and languages, particularly English and French, were absorbed into every aspect of everyday life, giving rise to a particular brand of cosmopolitanism, known as haipai (lit. ‘Shanghai style’; see Shen Reference Shen2009).

However, after the founding of People's Republic of China, the cosmopolitan culture of ‘Shanghai Modern’ was subsumed under nationalist ideologies and socialist discourses, until the economic reforms in 1978, and more remarkably the development of Pudong in the 1990s with its soaring skyline reawakening this ‘once lively and then for a time dormant metropolis’ (Huang Reference Huang2004, cited in Wasserstrom Reference Wasserstrom2008:6). As the pioneer and the ‘showpiece’ of the economic reform, Shanghai has once again become the international hub of trade and finance, and the economy and business centre of the country. This reconfiguration in relation to the post-socialist world also propelled the shift of people's subjectivity ‘from sacrifice to desire’ (Rofel Reference Rofel2007), in which a new kind of world citizenship is imagined and practiced in the neoliberal market economy. Intercultural communications and exchanges remerge with influx of foreign ideas and lifestyles, reviving the city's cosmopolitan urban culture first cultivated during the treaty port century, exemplified by Shanghai's celebrated night scenes where spaces of intercultural sociability as well as inequality and friction are (re)created (Farrer & Field Reference Farrer and Field2015).

This re-emergence of a cosmopolitan Shanghai took place in tandem with seismic shifts in the language, identity, and geography of the city. According to Xu (Reference Xu2021), the vernacular character of Shanghai has been marginalized both geographically and linguistically in the urbanisation process led by the state. As millions of its native population were displaced by large-scale infrastructure projects and millions of labourers and professionals migrated to the city from other parts of the country, the Shanghainese dialect has been quickly replaced by Putonghua as the most used language in public space. Meanwhile, as Xu (Reference Xu2020) observes, the sociogeographical distinction between Puxi ‘west bank’ and Pudong ‘east bank’, and between the upper corner (areas largely overlapping with the former French concession) and the lower corner administered by imperial and Chinese authorities since the mid-nineteenth century still hold sway in the social geography of the city to the present day and has ironically become a resource for displaced Shanghainese to assert their right to urban space.

The three-way tension between the global, the national, and the local in this reincarnated metropolis then presents Shanghai as the ideal research site to investigate the relationship between language, landscape, and cosmopolitanism.

RESEARCH INTERVIEWS AS PLACE TALK

Data under analysis in this article were research interviews from a larger ethnographic project on language, space, and cosmopolitanism in Shanghai, including five months of fieldwork, thirteen in-depth interviews with fourteen participants of varied age, gender, and regional backgrounds, linguistic landscape analysis of their activity spaces in the city, and analysis of public texts such as news, websites, social media, government policies, and historical references.

This article focuses on interviews with three participants, Liang (male, twenties), Chu (female, twenties), and Ming (female, late thirties), who all self-identify as native Shanghainese despite different family histories and personal trajectories. The interviews were conducted in Mandarin Chinese, but Shanghainese and English were also used occasionally depending on the expressive needs of the participants and the interviewer. One particularly relevant issue is the translation of the concept ‘cosmopolitan’ in Chinese. According to the Cambridge English-Chinese Dictionary, the word ‘cosmopolitan’ can be translated as laizi shijie gedi ‘from all over the world’, guoji da duhui ‘international metropolis’, shijiexing ‘worldly’, and guojihua ‘international’ (‘Cosmopolitan’ 2023). In academic discourse, it is usually translated as shijie zhuyi (lit. ‘world-ism’). In these interviews, the researcher primarily used guojihua to refer to ‘cosmopolitan’, because it is a more familiar usage in everyday language. Nevertheless, participants, especially those with a good command of English, were also invited to share how they understood the original term, which unexpectedly elicited much talk. In this sense, we suggest that the very meaning of ‘cosmopolitan’ was interactively co-constructed between the participants and the interviewer (see also Stockburger Reference Stockburger2015). The interpretations and analysis of the interview data were also informed by the participant observation, linguistic landscape analysis, and the examination of public discourses.

In terms of participants, this study focuses on young, professional individuals from the middle class. This reflects not only a limitation in the authors’ social networks, from which most participants were recruited, but also the autoethnographic aspect of this project, where both authors’ own relationships to the city and life experiences have informed the choice of research topic and the interpretation of data. More importantly, well-educated young consumers with high purchasing power have been noted to represent a significant force in the shaping of cosmopolitan urban culture in contemporary China (cf. Farrer Reference Farrer1998; Rofel Reference Rofel2007).

EVOKING ‘SHANGHAI MODERN’: COSMOPOLITANISM AS AFFECTIVE SEMIOTIC LANDSCAPE

Each research interview began with the question ‘Which areas in Shanghai do you think are cosmopolitan?’. This was originally intended as an icebreaker and to survey the areas for subsequent linguistic landscape analysis, but as mentioned above, the term ‘cosmopolitan’ has several Chinese translations, and thus the meaning of the word itself became a moot point. In the excerpts below, we see how participants define, negotiate, and debate cosmopolitanism by evoking a variety of semiotic landscapes.

The first excerpt came from the beginning of the interview with Liang and Chu, two master's students in their twenties at the time of fieldwork. Both were born and raised in Minhang, a district of Shanghai.

(1)

First, we can observe how the two participants converge in their epistemic stances (Du Bois Reference Du Bois and Englebretson2007) towards a semiotic landscape that is deemed to be ‘cosmopolitan’. In lines 5–10, Liang proposes an understanding of ‘cosmopolitanism’ as exhibiting the feel of xiaozi. Literally meaning ‘petite bourgeoise’, xiaozi in socialist discourse used to refer to the social class of semi-autonomous peasantry and small-scale merchants. However, the expression in post-socialist China has taken on a new meaning since the 1990s, referring to a consumerist taste and lifestyle perceived to be westernised. This diachronic semantic shift illustrates Rofel's (Reference Rofel2007) argument that ‘cosmopolitanism with Chinese characteristics’ is often accomplished through practices of consumption.

Liang's uses of hedges such as ‘in fact if we discuss it rationally’ and the question ‘do you think so?’ show that he is not quite confident in asserting this association at first, and hence he invites his interlocutor to share her view. Chu's stance is not assertive either, as detected in the rising intonation of ‘I think, yes?’ and the modal auxiliary ‘I can agree’ in line 10. Liang then latches on and specifies his use of xiaozi as in ‘xiaozi character’ (line 13), again with hedging strategies such as ‘has something to do with’ and ‘in my mind’ to speak for ‘me’ (lines 11–13). In line 14, Chu quickens her alignment with Liang's epistemic stance by repeating ‘I agree’ twice, expressing a stronger support for this interpretation. In so doing, she also aligns her relational stance with Liang.

The interviewer then asks them to elaborate on the meaning of xiaozi, which Liang defines as an ‘ambiance’, emphasizing the importance of the affective atmosphere when defining ‘cosmopolitanism’. As Anderson (Reference Anderson2014) argues, an atmosphere is more than an ensemble of objects and bodies; it is rather, ‘a kind of indeterminate affective excess through which intensive space-times are created and come to envelop specific bodies, sites, objects and people’ (Reference Anderson2014:160). Indeed, Liang's vague references to ‘surrounding buildings, that street, and people around there’ in lines 17–20 were then linked to ‘posh Shanghainese’ who frequent these places, corroborated by Chu in line 24. And when Liang jokingly evokes the song Ye Shanghai ‘Shanghai Nights’ in lines 30–32, the affective atmosphere of xiaozi and ‘cosmopolitan’ is again created by indexing a specific period of the city's history. Produced in the 1940s by the legendary Chinese singer Zhou Xuan, the song is arguably the most well-known shidaiqu (lit. ‘songs of the era’), a genre featuring the mix of Chinese folk music and American jazz. Describing night life in Shanghai, it has become a popular cultural symbol of the glamor and decadence of the ‘Shanghai Modern’ period discussed by Lee (Reference Lee1999) and still symbolises the hybridity of cultures which can be observed in the contemporary landscape of this bona fide cosmopolitan city (Farrer & Field Reference Farrer and Field2015).

It is thus unsurprising that the reference to the song also visually appears in the semiotic landscape of the city (see Zhao Reference Zhao and Lee2022). Figure 2 shows the neon sign of a Michelin-starred restaurant specialising in Shanghainese cuisine located in Xintiandi, a trendy area converted from traditional residential architecture known as shikumen. The song is not only the restaurant's namesake, but it also evokes this golden era through the material of neon light, reminiscent of the city's streetscapes in the 1930s and 40s, and through the visual design. Instead of traditional Chinese brush calligraphy which typically adorns the shop fronts of Chinese restaurants, the strokes of the Ye Shanghai sign are evidently written with a fountain pen, again symbolising the modernity of the era.

Figure 2. ‘Ye Shanghai’ sign of a restaurant located in Xintiandi (July 27, 2019).

Returning to the analysis of the first excerpt, we can observe two orders of indexicality (Silverstein Reference Silverstein2003) in operation here. The participants first index the ‘Shanghai Modern’ chronotope when Shanghai emerged as a cosmopolitan city by evoking a pop song from the era, which re-creates the city as an ‘experiential milieu’ where the ambiance of cosmopolitanism can be relived (cf. Degen Reference Degen2008). The evocation of this imaginary semiotic landscape further indexes the class identity of xiaozi at the second order. While converging in their epistemic evaluations of what a cosmopolitan semiotic landscape entails, the two participants are also aligning their relational stances with each other and with the collective ideology of native Shanghainese people.

Further down the interview, this nostalgic ambiance of ‘Shanghai Modern’ is contrasted with the contemporary semiotic landscape that has become an emblem of the global city (Li & Yang Reference Li and Yang2021) in excerpt (2).

(2)

The reason for Chu to mention Lujiazui at this point in the conversation can be interpreted as a challenge to the official as well as popular stance towards the area's elevated skyline dominated by the iconic Oriental Pearl TV tower and a number of Asia's tallest buildings (lines 15–17), which is also shared by some other participants as we discuss in the next section. After Chu asserts her epistemic stance towards this landscape that ‘Lujiazui can never become a cosmopolitan place’ in lines 1–3, Liang supports her argument by describing it as ‘modern, but not cosmopolitan’ (line 4) and explicitly comparing it with the semiotic landscape of the western bank of the river (lines 8–10). Over the subsequent lines, they continue their evaluations of both landscapes, underpinned by their understanding of cosmopolitanism as a colonial legacy. For Liang, the soaring skyscrapers of Pudong lack ‘cultural substance’ despite their height (lines 25–31), and this is because, according to Chu (lines 32–33), Pudong has not been colonized. At first, this might appear to be an uncritical and problematic reappraisal of the city's semicolonial history as a treaty port, but in the context of the interview, it could be read as another nostalgic reference to the Shanghai Modern era evoked earlier in the conversation (see excerpt (1); Figure 3 demonstrates the contrasted semiotic landscapes of Puxi and Pudong).

Figure 3. Semiotic landscapes: Puxi vs. Pudong (July 22, 2019).

It needs to be stressed here that history alone does not make a place cosmopolitan for our participants. Rather, it is the hybridity that characterizes Shanghai's urban culture in the 1930s and 40s that underpins their understanding of the term. These excerpts have also demonstrated how such shared epistemic and affective stances towards the semicolonial semiotic landscape also index class and prestige (xiaozi, to use our participants’ term). In the next section, we turn to examine how this evaluation of cosmopolitan Shanghai is also intertwined with how people position themselves and others in relation to the city.

IDENTIFYING ‘REAL SHANGHAINESE’: COSMOPOLITANISM AS CONTRASTIVE SEMIOTIC LANDSCAPE

As one of the participants, Liang, emphasizes in the interview (excerpt (1), lines 20–22), the opinion of local Shanghainese is a critical criterion in the evaluation of the cosmopolitan character of a place, implying that it might not be shared by outsiders including tourists as well as non-native residents of the city. This contrastive stance towards semiotic landscapes indeed emerges as a consistent theme throughout the research interviews.

(3)

Excerpt (3) is from the interview with Ming, a freelancer in her late thirties, born and raised in Shanghai. This part of the conversation occurred after our discussion about cosmopolitan spaces in Shanghai, in which she also pointed to the former concession areas. To move the interview onto the next question, the interviewer brought another participant, Young, into discussion in lines 4–9, inviting Ming to respond to Young's comment. During this move, the interviewer also projects her epistemic and relational stances in the constructed dialogue. The rising intonation in ‘Ay↑why Lujiazui?’ makes the question more of a doubt than a query of Young's epistemic stance towards Lujiazui, which also distances the interviewer from Young relationally. At the same time, it opens up the possibility for constructing a shared stance with the current participant—Ming (cf. Stockburger's Reference Stockburger2015 study on interviewer and participants’ joint construction of zine producer identities in their interview). This then created a space of solidarity in which Ming frankly shared her conceptual map of the city as a ‘real Shanghainese’.

Reacting to Young's perception of Lujiazui (Pudong's central business district) as being cosmopolitan as reported by the interviewer, Ming immediately identifies Young as ‘not native Shanghainese’, which is confirmed by the interviewer. The divergent stance towards Pudong between native Shanghainese and non-locals echoes Xu's (Reference Xu2020) findings in her examination of emotional responses of displaced Shanghainese to newly developed urban space. Based on her interviews with both native and non-native Shanghainese, Xu argues that claims such as ‘Pudong is not my Shanghai’ are ways through which native Shanghainese strategically construct their identity of the city in resistance to the rhetoric and vision of the overall state and municipal urban planning. In contrast, the non-natives are more comfortable to include Pudong and its newly urbanized, globalised, and ‘non-place’ (Augé Reference Augé and Howe1995, reference in original) semiotic landscape as part of Shanghai.

Ming then extends her individual epistemic stance as a collective ideology of Shanghainese people by recalling a popular saying, ‘one would rather have a bed in Puxi than a house in Pudong’, which reflects an old geographic stereotype about the undesirability of living on the eastern side of the river. Though originated from the local vernacular, this idiom has been circulated widely in Mandarin, and almost every Chinese participant of the project has mentioned it in the interviews regardless of their origins and backgrounds. As a non-native resident herself, the interviewer latches on in line 17, displaying her insider knowledge. Leaping from this popular saying, Ming goes on to dismiss ‘all’ places on the eastern side as ‘not Shanghai’. She describes Pudong as a ‘village’ (rhotacized as cun'er in the Beijing dialect, adding to the rural flavour), and the original inhabitants of Pudong as the ‘indigenes’. This rural analogy serves to further position Pudong as the ‘Other’ vis-à-vis Puxi as the city.

In lines 27–33, Ming explains this analogy by alluding to the city's history. The ‘indigenes’ of Pudong or in her words the ‘real real Shanghainese’ refer to the original inhabitants of Pudong who have lived there for generations. Ironically, their historical habitation of the land did not make them ‘native Shanghainese’, which is quintessentially an urban identity, as Pudong remained largely farmlands until 1980s while Puxi developed into a cosmopolitan city during the treaty port century. In spite of bearing the postcard image of the Shanghai skyline, the rural history of Pudong still makes some people exclude the area from their urban imaginations, as Ming sneers in lines 41–42 ‘how could Pudong ever be Shanghai?’. Again, she does not qualify this as her individual opinion, but a view shared by ‘real Shanghainese’, who are defined not so much by the length of their inhabitations on the land but rather by their ideological allegiance towards either side of the river. In other words, if one acknowledges or even appreciates the semiotic landscape of Lujiazui as being cosmopolitan, they are not ‘native’ Shanghainese, because they do not share the hierarchical social-geographical ideology with locals. The epistemic stance towards cosmopolitan landscape then becomes a key discursive resource in place-identity.

The divergent native vs. non-native stance is also demonstrated in excerpt (4) extracted from the interview with Liang and Chu, when they debate about tourist spaces.

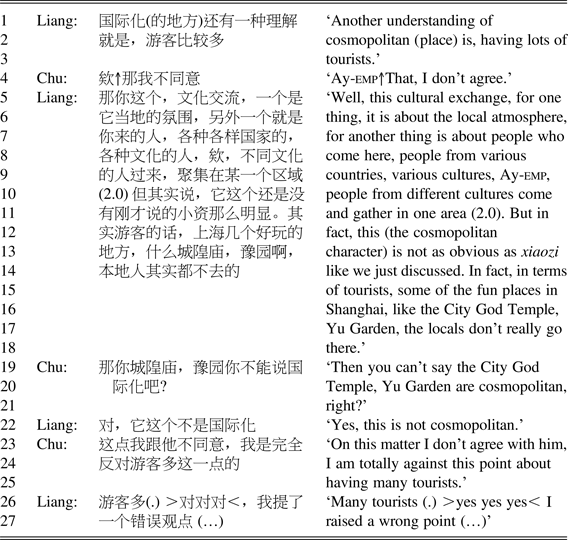

(4)

At first, Liang proposes that cosmopolitan places are also characterized by a large number of tourists, an epistemic stance not shared by Chu, as indicated by her rising intonation of ‘Ay’ and the explicit statement of disagreement. This prompts Liang to justify his stance by interpreting cosmopolitanism as the coming-together of people from diverse cultural backgrounds as seen in tourist destinations. Then, after two seconds of silence and no contribution from Chu, he concedes that the cosmopolitan character of tourist destinations is not as obvious as xiaozi places as discussed previously (see excerpt (1)), acknowledging that these places were not visited by the locals. This compromise and ambivalence in Liang's epistemic stance encourage Chu to question his earlier assertation that places like City God Temple and Yu Garden were cosmopolitan. She then directly voices her disagreement in line 23, leading Liang to revise his epistemic stance in order to realign himself relationally with his interlocutor. This negotiation on cosmopolitan places of Shanghai suggests that, there is a discrepancy between what is commonly understood as ‘cosmopolitan’ (such as Liang's account in lines 8–11 about the agglomeration of people from different cultures) and ‘cosmopolitan’ as in ‘cosmopolitan Shanghai’. The latter also has to be a local space, but at the same time, it has to index a particular kind of cultural hybridity reminiscent of the republican era (cf. Lee Reference Lee1999; Farrer & Field Reference Farrer and Field2015).

CONCLUSIONS

In his introduction to a special issue on cosmopolis, Featherstone (Reference Featherstone2002:2) suggests that ‘we should endeavour to understand cosmopolitanism in the plural’. As demonstrated in his edited volume, this entails, first, examining the relationship of cosmopolites to cities, and second, learning about cosmopolitanism outside the West. Rofel (Reference Rofel2007), for example, has identified a type of ‘cosmopolitanism with Chinese characteristics’ which exhibits a paradox between global and domestic orientations, intertwined with the reconfigurations of class, gender, and consumer identities in post-socialistic China. Our article adds another layer to this multifaceted and rooted cosmopolitanism by examining the discursive production of place-identity in research interviews about the semiotic landscapes of the city. This version of cosmopolitanism is rooted in Shanghai's semicolonial past, and is celebrated and privileged over the version shaped by contemporary globalisation and nationalistic discourses, as reflected in the participants’ uneven valorisation of the two semiotic landscapes on either side of the river.

In so doing, this article also contributes to the small body of sociolinguistic work which has sought to reterritorialise cosmopolitanism (e.g. Curtin Reference Curtin2014; Blackwood & Tufi Reference Blackwood and Tufi2015). Approaching place talk as an independent genre of discourse with the potential to connect landscape and identity (Jaworski & Thurlow Reference Jaworski and Thurlow2010), we have examined how participants take stances towards the semiotic landscapes of the city and how these stances further index their place-identity. Talking about place may have been a ‘side product’ of research interviews in the past, but we have ventured to show here that it provides an invaluable, probably also indispensable window into how the meaning of landscape is dynamically constructed in talk and becomes indexical of larger social categories.

As we conclude this article, Shanghai is gradually recovering from a period of strict lockdown as part of China's ‘zero-Covid’ campaign, a crisis that challenges the identity of Shanghainese to the core. It is important to acknowledge that the findings presented in the article are based on ethnographic research conducted before the global pandemic, and it will be interesting to investigate how views of the participants have changed since then. This article is also limited in its focus on young, educated, and relatively affluent participants who self-identify as Shanghainese, albeit triangulated with interviews with non-local participants and researchers’ participant observations. Further research is needed to investigate to what extent this localised view is shared by individuals from different backgrounds in Shanghai and elsewhere, in order to truly understand cosmopolitanism ‘in the plural’.

Appendix: Transcription conventions

- (…)

intervening material has been omitted

- (.)

brief pause

- (1.0, 2.0, 3.0)

pause for seconds

- (haha)

laughter

- ()

information added for clarification

- [ ]

description of interactional details

- {

speakers overlap

- italics

code switching

- underline

emphatic stress

- emp

emphatic particles

- =

contiguous utterances

- ,

utterance signalling more to come

- ./。

utterance final intonation

- ↑

rising intonation

- !

exclamation

- > <

speed up