The excerpts below explore Azaare's motivation to embark on his lifelong project of preserving Gurensi history outside mainstream academic circles. The preface highlights his awareness of his own position as an autodidact within an unequal field of knowledge production about northern Ghanaian societies. The excerpts provide an account of Azaare's hybrid methodology, aims and challenges in the field, and aspirations for research impact. The full text of the manuscript is available with the supplementary materials published with this article at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0001972020000261>.

Preface

Admittedly though the Gurensi and Boosi, and for that matter the Frafras, living in the Bolgatanga and Bongo District Council Area have flourished for nearly over five hundred (500) years, their history and traditions have for these centuries laid almost buried and forgotten. Their history has in fact been relatively neglected by comparison with the period of the Mamprusi, Gonja, and Dagomba histories. The works of early researchers, ethnologists and so forth on the Gurene and Bone speaking peoples such as Allan Wolsey Cardinall (1921), R. S. Rattray (1932), T. E. Hilton (1956, 1959) and Dr Ludwig Rapp (1967) are devoid of the oral traditions and history of these people at the local level. In the case of R. S. Rattray and A. W. Cardinall, their works are not only brief, but they appear in a rather unusual sequence.

It must be said that the Gurensi and Boosi have their history, but it is mostly oral. This book, therefore, is the first of its kind dealing specifically with the legendary origins, genealogies, political, social and economic life of the Gurensi and Boosi peoples.

This book has taken me a little over twenty-nine years to complete. The reasons for the delay have been explained in the proceeding discussions. This book has been written for four main reasons. The first reason is that historians, anthropologists, ethnologists and other social researchers have not been able to write about the Gurensi and Boosi culture and history because of their inability to trace first the history of the individual communities or towns that make up the Gurensi and Boosi. It is also probably due to the intricate problem of the origin of these people.

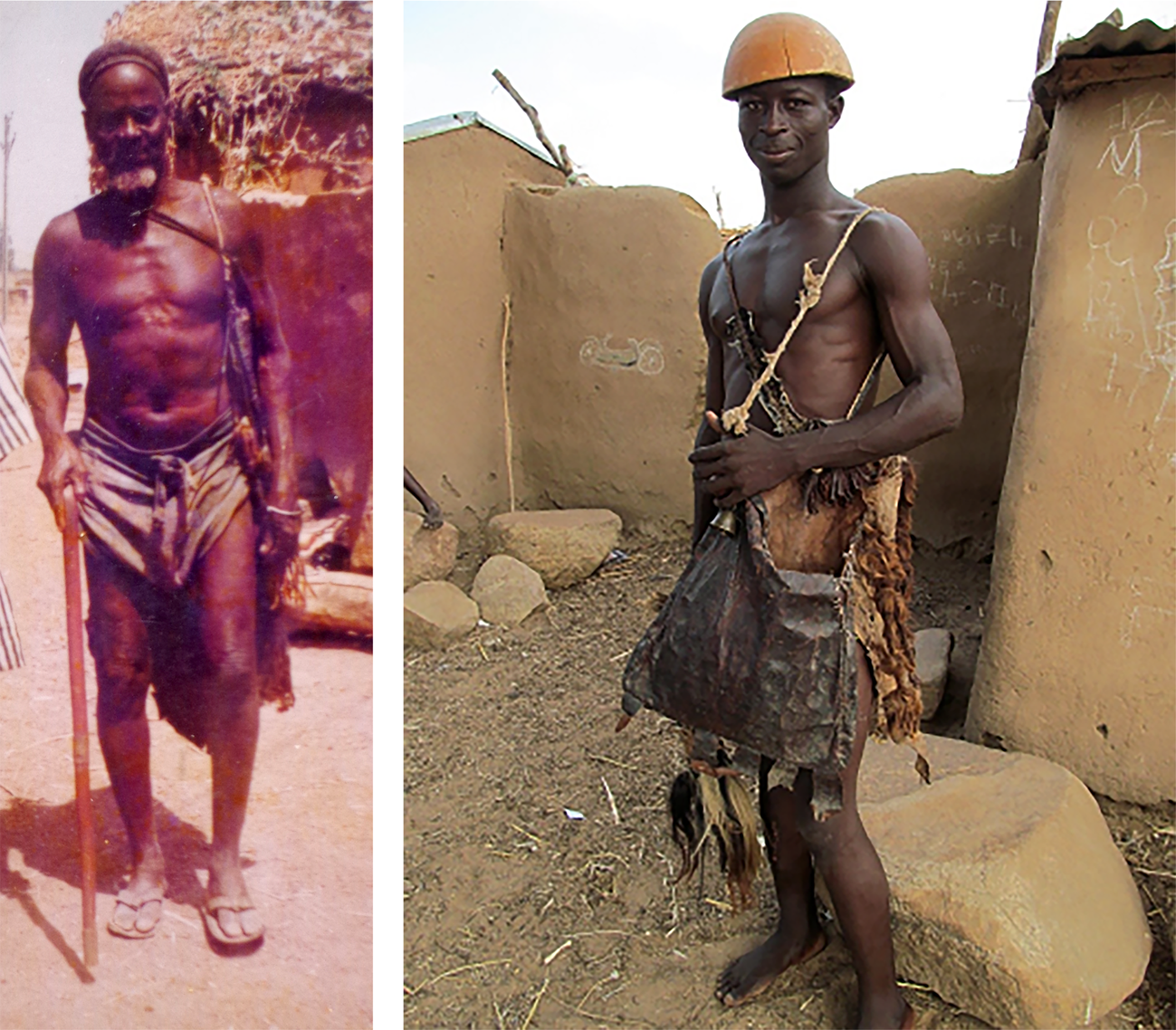

Figure 1A Tindaan Banga, Dapore-Tindongo (left). Figure 1B Zoko Kadare Tindaana (right).

A second reason is that so much is changing rapidly in the towns and villages of the Gurensi (Frafra) Area and the country as a whole. Therefore, it is proper that past events are recorded before the records get lost through fires and rainstorms, Westernization, schooling, etc.

Third, the Gurensi history and life have been misunderstood, distorted or exaggerated by early Western scholars. According to the Black American scholar, Prof. Jacob Carruthers, ‘World history has been written from an European perspective. There have been a lot of distortions and exaggerations. For a start the role of ancient Egypt in civilization has been underplayed in relation to Greece. We need to put Africa in the proper place. The goal is within black peoples’ reach.’Footnote 1 Therefore, taking cue from Prof. Jacob Carruthers, I want to put the Gurensi and Boosi (Frafra) history and culture in their proper place.

Fourth, we all know that no country, town or village can progress if it neglects her history. This research is therefore intended to compel the present generation and those to come to have the likeness for their own history because that will help them become wiser and help them to progress. It is easier to understand other fields if you know history.

Last but not least, it is clear that since the introduction of Western type of education, foreign history and culture has been emphasized, thus relegating the local history to the background. The effect of this is that both the elderly and the young are unable to trace their origins, migrations and let alone their family genealogies. Many of the old and young people do not even know their nearest ancestors and ancestresses. The few old men who can trace their ancestors do so up to three or four generations back. Whenever I met a cross-section of the literate folk, I posed such questions like:

1. Who was the first authentic chief of Bolgatanga?

2. Who was the founding father of the Boosi?

Many of the respondents, in fact, evaded my questions under the pretense that they were busy. By comparison, when the same respondents (the literate folk) were asked the following questions on foreign history they gave perfect answers:

1. Who was the founder of Rome?

2. Who was the first king of Asante?

This gave me the impression that the youth of today are not interested in their own histories and culture. At this point I should quote Ross S. Leith to support my claim: ‘The young men are content to have no past so long as they have a future.’Footnote 2

My concern was to record the skills, technologies, social life and wisdom of the old men which are fast disappearing. One would realize that both Western and missionary education has taught us a great deal about who they are, where they came from and why they are here. Our situation is quite disheartened because we cannot tell who we are, what we are, where we came from, etc. In fact, we cannot claim to be ignorant of the fact that we are losing things that are so dear and valuable to us in exchange of what is alien to us, losing treasuries that are priceless to our lives in exchange of wealth that can be measured in monetary terms, losing our Earthgod priests (tindaanas) to acquire a Catholic priest or a pastor, replacing our medicine men with conventional doctors, losing our rivers in exchanges for piped water. We have, in fact, lost much and gained little. We have lost our dances, our rituals and values, our material culture and medicines, and our languages. We have lost our land together with its sacredness. We must all be concerned with this great loss and act decisively to prevent further degeneration of our indigenous knowledge and traditions. Contrary to the views of the young men, some of the old men and chiefs who met me congratulated me on my efforts to maintain the originality of their customs and history. At Yikene and Sumbrungu the old men expressed similar sentiments especially about their genealogies. Asona from Sumbrungu said ‘If we had such inquisitive people like your type during our days we should not be having problems of tracing our genealogies. Your work will make the White man also fear us.’

II. Methodology

Before undertaking the project, I would travel to these old men and women who occasionally met around some bonfire in the evening, chattered and exchanged views concerning their histories, culture and religion. I would also sit among them and ask some questions which they claim some of them were inciting. Before making my enquiries, I will present them with kola, tobacco and drinks and then proceed to narrate the rationale behind the research. I will then ask them for their co-operation and even promise them their anonymity. Interviews were almost invariably carried out in a Ghanaian language, and mostly in Gurene. The Gurensi have it in their proverb that gareseko nde bogro. This literally means ‘detail enquiries are soothsaying’. This has in it the idea that he who gets into the bottom of a matter by detailed questioning is like the one who has consulted a soothsayer. This is so because I would ask a series of questions about their origin, migrations, chieftaincy, social, economic and ethnic relations. I would ask questions about their indigenous political system and how this system came to be superimposed by the Mamprusi and the British systems of government. I also probed into the families that contest for chieftaincy in a town and village, the order of succession of the chiefs, the surnames, personal appellations, names and skin names of their chiefs, the enskinning authorities and the rites, and the ceremonies associated with the enskinment of a chief and a tindaana. I also went further and made enquiries as to the animals, birds and reptiles which they do not eat or cause harm to. A lot was also asked about their sacred places. The Gurensi presupposes that an old man should not talk lies; those old men I interviewed presumably gave me frank and honest answers. There were some old men and women who would give long and winding answers and in conclusion will remark: ‘This is what I personally saw, and this is what I heard from my grandparents and so on.’ I had the patience to listen to all the narrations which my respondents gave me. This was to enable me to extract the correct answers out of them. I was rather careful in the reliability of some of the facts since the Gurensi have a saying that one does not point his left finger in the direction of one's mother's natal village. Another saying goes that no one would dare add sand to his own millet grains. Both sayings suggest that no one would ever dare or want to tell bad things about himself and for that matter his family or clan. Taking cognizance of the above saying, whatever information or answers were given by any old man in any village was cross-checked in collaboration from another lineage or clan elders. It was then noticed that when narrations were compared with others, there was a great similarity amongst them which I believe testified to their veracity.

III. What some of the people did not like

During my field trips to the communities I observed that certain people did not like it to be said about their family, clan or community that they are descendants of sister's sons, slave people or migrants from unknown origin. Some did not want to accept the fact that their forefathers had at one time been subjugated by another; there were some people who did not agree that their grandparents never contested for chieftaincy. But the facts are facts, and these are the very ones that have been recorded in this book. To quote Fortes: ‘If a sister's child is buried at our place his house will become many and ours will die out.’Footnote 3 In other words, be careful not to let a sister's child or a bought person forget his stranger origin.

IX. Expectation

The expectation from this research is that:

1. Once a register of skin makers and lineage or families entitled to each skin are documented, chieftaincy disputes will be greatly minimized.

2. The documentation of the history of the Gurensi and Boosi would expose their cultural and religious concepts to a wider audience outside the peoples’ own localities.

3. People will correct the anomalies as misrepresented by most researchers on the Gurensi and Boosi.

4. The information will help change the people's negative attitude and dislike for their own history.

6. It will serve as lessons to be taught in schools (both formal and non-formal institutions).

7. People will be able to trace their origins and reasons for migrations.

8. People would be able to know their kinship groups.

9. People will maintain their original names in contrast to what they have been called.

Chapter 10: Origin, migrations and history of the Bolga people

The selections from Chapters 10 and 11 below are reproduced from Part IV of Azaare's manuscript, which is dedicated to the genealogies of tindaama (earth priests) clans in the Bolgatanga and Bongo traditional areas. The excerpts from Chapter 10 focus on the contested origin, migrations and history of the pioneer clans of Bolgatanga, the capital of the Upper East Region of Ghana. They illustrate Azaare's endogenous methodology at work, which has enabled him to highlight competing perspectives of elders that are not available in other academic sources. For instance, Azaare's categorization of tindaanaship, which he develops in Chapter 2 and can be accessed in the full-length online version of the manuscript, allows him to trace the foundation of Bolgatanga to a tindaanaship of the sister's son type, and possibly to a pioneer female tindaana of Tindonmolego. Here, Azaare renders visible a ‘subjugated’ version of Bolgatanga's history that remains largely silenced today among the competing accounts of first-comer settlement advanced by opinion leaders and land claimants.

10.1 Founders and foundation of Bolga town

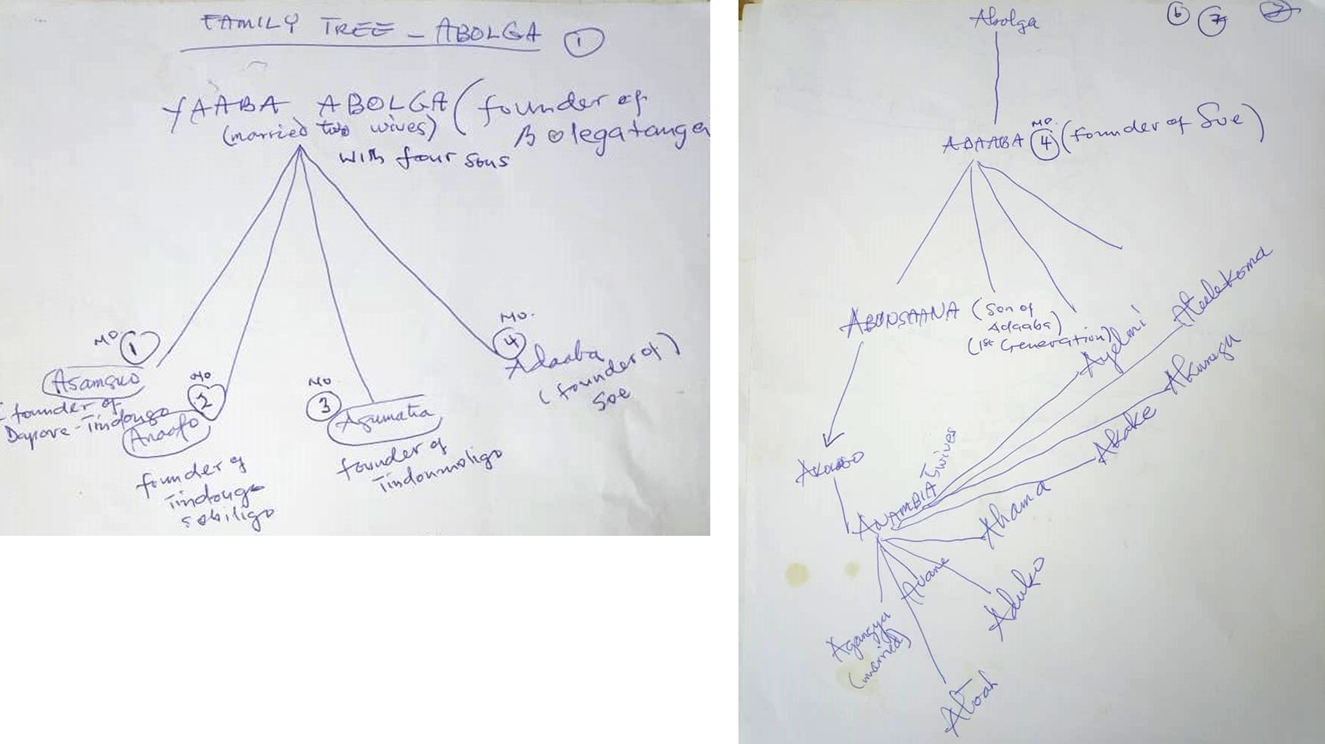

Bolga town is inhabited by two social groups. They are the Tindaambisi (pioneer settlers’ children) and Nabissi (chief's children/offspring). Both these social groups trace their origin to Yua. The only difference is that one of the groups came from Yua (in the Kasena-Nankana District) and the other group came from Yua (in the French country of Burkina Faso). Research has, however, shown that those who claim their origin from Yua (in the Kasena-Nankana area) just stayed in the place for two or three generations, having left the following towns in the Yatenga Province of Burkina Faso: Gourcy, Oula and Xiebele (also spelt Chibelle) near Ouihigouya. It would be wrong for people to assume that the origin of the Bolga people lies in Yua only. Nonetheless, it would interest the reader to note that those groups that came from Yua in both the Kasena-Nankana area and the French country of Burkina Faso dominate Bolga town today. For instance, the Atulbabisi (Apɔɔrebisi, Anafobisi, Awarɛbisi, Akunlibebisi in Tanzui), Zorbisi, Sokabisi, Dagmeo, Dapore-Tindongo, Tindonsobiligo, Tindonmoligo, Pologo, Bukere and Pobaga are migrants from Yua. The Tindaambisi (comprising of Tindonmoligo, Tindonsobiligo and Dapore-Tindongo) are believed to have migrated from Yua in the French country of Burkina Faso. The date of their migrations cannot be determined from their genealogies, which goes back eighteen to twenty generations back. That means that the Tindaambisi in Bolga may have been living in their new homes about 450–500 years ago. The founding father of the autochthonous clans (tindaama) was Atandagere and popularly called Abolga. According to oral history, a fight ensued among Abolga and his brothers in Yua over who was to succeed to their father's skin.Footnote 4 As a result of the family skirmishes, Abolga/Atandagere withdrew from Yua with his family and a few followers such as Asorebaseya and Agutinga to build in the area of Amirigu (in Yikene).Footnote 5 According to the story, Abolga married two wives. One of them gave birth to Asamsoo and Anafo. The other wife gave birth to Azagsibaga and Adaaba. It is related that Adaaba (alias Tindanbia) and Azagsibaga (alias Tindonmoligo) were of one mother while Asamsoo and Tindonsobiligo (Anafo) were of the same mother. However, according to sources, Tindonmoligo (Red) and Tindonsobiligo (Black) were twin brothersFootnote 6 and the former was senior. There is controversy among the families of Abolga as to which of his sons was senior and who was junior. And it is even doubtful whether Tindonsobiligo (Anafo) and Tindonmoligo (Azagsibaga) were truly twins.Footnote 7 It is even believed by other descendants of Abolga that Tindonmoligo (Red) was a female.Footnote 8 And therefore, her descendants are sister's sons (pɔka kɔɔma). In view of these controversies, one needs to probe into the relationship of Abolga's sons and daughters to each other much further. Abolga lived and died in Amirigu and was buried there. He was survived by five or so sons who were later to become the founders of Tindonmoligo, Tindonsobiligo, Dapore-Tindongo and Soe, which form the four patriclans of Abolga's descendants within the territorial boundary of Bolgatanga. Yikene – the original home of Abolga – is undoubtedly the oldest settlement in the region of Bolgatanga. On the question of who is the most senior tindaana of Abolga's descendants, the majority would say the Tindonmoligo tindaana. Currently the god of Abolga (founder of Bolga) which was originally kept under some rock in Amirigu is in the care of the Tindonmoligo tindaana. The god symbolizes the perpetuity, identity and common ancestry of the tindaama. The early genealogy of Abolga is shown in Figure 2 below.

Figures 2A and 2B Azaare's fieldnotes on the early genealogy of Abolga's descendants.

According to oral tradition, some generations after Abolga and his companions had lived in Amirigu, a group of Moosi led by Anabila arrived in Yikene (Amirigu) to join Abolga. Anabila came with Asa-amgongo, Asoka, etc. and this group is said to have arrived in Yikene/Amirigu from Aliya-Tanga near Ouihigouya (the capital town of the Moosi state of Yatenga) through Yua. It was Abolga who gave Anabila and his companions some land at Amirigu to build and to farm. Abolga made Anabila chief and he remained himself the tindaana of the community. Anabila was therefore the founder of the Nabissi clan in Bolgatanga today. The dispersion of the descendants of the founders of the two major social groups in Bolgatanga – the Tindaama and Nabissi clans – from their old homes in Yikene would receive attention in due course.

The people of Bolga town, however, assert that there is remote connection among them and especially the pioneer settlers (Tindaambisi) and the royal clan (Nabissi). This relationship is borne out of the fact that they all believed themselves to have migrated from Yua (in both the Kasena-Nankana and Burkina Faso) and lived together in Yikene. The connection between the two main social groups (Tindaama and Nabissi) in the Bolga town is sometimes denied but it appears to be obvious. The relationship between these two groups would be much appreciated if we trace their origins and history. A distinction is made between these two groups: only the Tindaambisi provide the Earthgod priest (tindaana) and the Nabissi provide the chief (Naba). A tindaana is always needed in the major rituals of the community such as land, harvest, and murder rites. The Nabissi (literally: chiefs’ offspring/children), unlike the tindaambisi, have exclusive rights to possess nam (chieftaincy). That means they have the power to rule or govern the people.

In the traditional Gurensi society a chief can only exercise the function of a tindaana if he was ritually initiated into the office. A distinction is made between the tindaana and naba with the expression ‘Naba suɔ la a nɛriba, tindaana suɔ la a tiŋa’ (literally spoken as ‘the chief is for the people, the tindaana is for the land’).Footnote 9

10.2 Facts about Bolgatanga

There are two or more schools of thought on how Bolgatanga derived her name. According to the first school of thought, on the first coming of the White men to this part of the country they met some women sitting at the Aliya-Tanga and enquired about the place, to which they replied ‘Boleŋa-Tanga.’ Boleŋa-Tanga was corrupted to Bolgatanga.Footnote 10 This may be understood in this way: what is called today as Bolgatanga was originally called Aliya-Tanga. This is the area where the most influential Earthgod or shrine of the Dapore-Tindaama, the Aliya, stands. This is in the nature of an ebony tree standing in between rocks (ta'ansi (plural)/tanga (singular)). Aliya-Tanga was a resting place for women who used to shuttle between Dapore-Tindongo and Kumbangren and Tindonsobiligo (on the main Bolga–Tamale trunk road) to collect soft soil (in Gurenɛ ‘bole’). The area where bole is collected is boleŋa. And so boleŋa-tanga – rocks on which women carrying soft/top soil take their rest or sit to share information. According to the second school of thought, Bolgatanga is a derivation of Abolga under rock.Footnote 11 In the area of Amirigu (in Yikene) there was a special rock dedicated to the spirit of the historical founder of the town, Abolga. So that under the rock was the god of Abolga: Abolga-Tanga (i.e. Abolga's rock/Abolga under a rock). Yikene could be described as the original Bolega-Tanga because it was here the god of Abolga was hidden under rocks. The area now erroneously called Bolgatanga was originally Aliya-Tanga.

Figure 3 Tindonmoligo Tindaana Ayeta Ayinbire Atuuna (enskinned on 17 November 2015).

Chapter 11: Dispersion of the Tindaambisi (Abolga sons)

The excerpts below are reproduced from Chapter 11, which builds on Chapter 10 by tracing the dispersion of Abolga's sons, the founders of the four major tindaama clans in Bolgatanga. The selections focus on Asamsɔɔ and Dapore-Tindongo, a prominent section of Bolgatanga that includes a large part of the town's centre and has a contentious history of tindaanaship succession. The chapter offers insight into the depth of Azaare's genealogical research and his idiosyncratic mode of assembling and systematizing oral and archival material into extensive family trees and succession lists. It also provides understanding of local variations in the procedures for nomination and installation of tindaanas in Bolgatanga, as well as in the regalia, rites and taboos associated with the institution. For Azaare's generalized typology of these procedures, rites and taboos, see Chapters 1 and 6 in the full-length online version of the manuscript. The supplementary materials also include scans of some of Azaare's fieldnotes, which illustrate his process used to generate the narrative and family trees in Chapters 10 and 11.

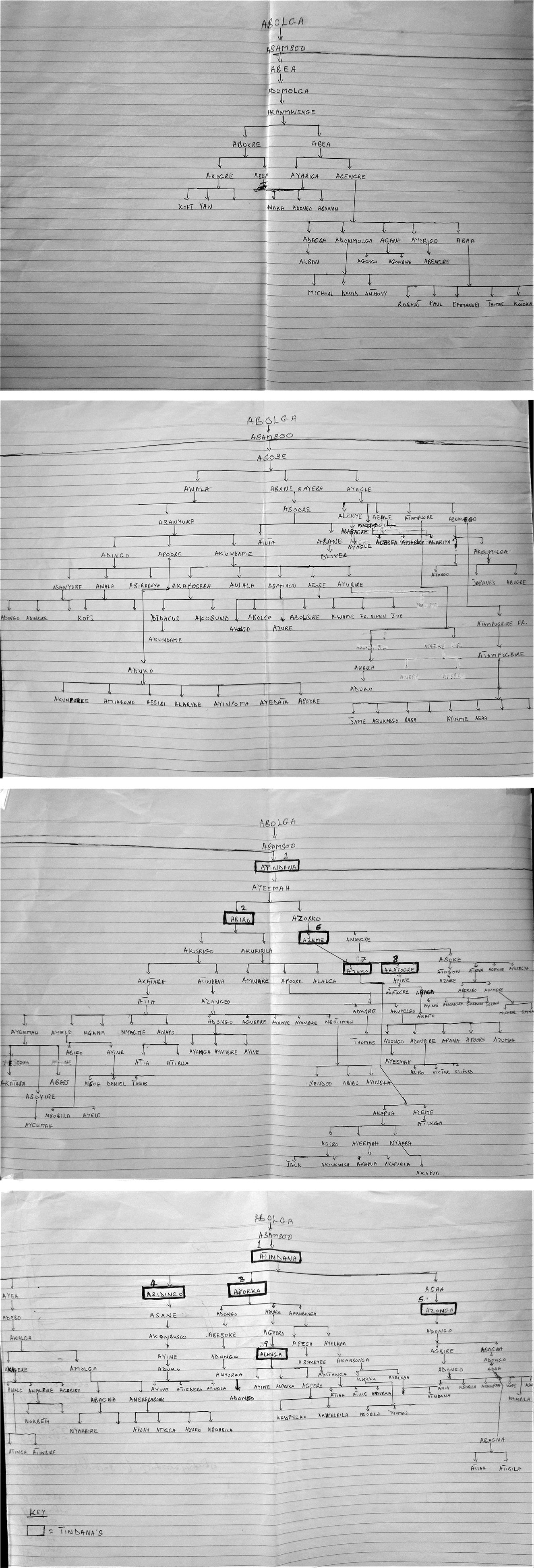

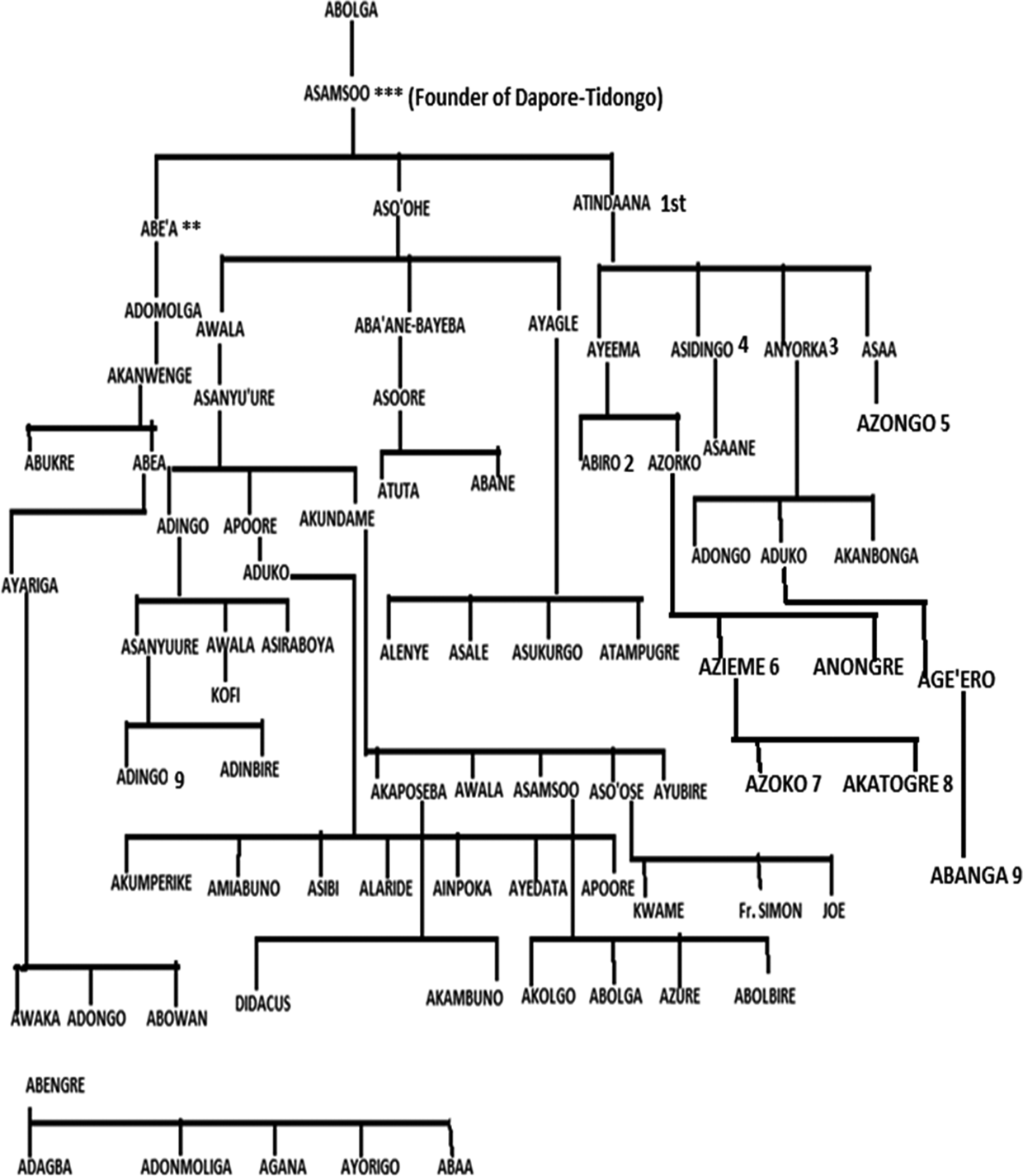

11.5 Migration of Asamsɔɔ and offsprings

According to oral tradition, after the death of Abolga his son Asamsɔɔ remained with his brother at Yikene/Zoobisi area for one or two generations. From Yikene, Asamsɔɔ and his family travelled to the east of Tindonsobiligo and Tindomoligo, where he found a suitable place and built his compound. The area Asamsɔɔ built was later called Dapore-Tindongo, a name which suggests ‘east of Tindongo’. Asamsɔɔ, the founder of Dapore-Tindongo, married two wives, who gave birth to a number of children. Asamsɔɔ's sons were Asohɛ (the most senior), Atindaana, Abiɛa, Awala, Akambunga and Asaale. Asohɛ and Atindaana were sons of Asamsɔɔ's senior wife. Abiɛa was the son of his junior wife. Abiɛa begot Adombire, Abengre, Ayarega, Amaleboba and Ababire. These, in turn, had children. Atindaana's sons were Atosuum, Azongo, Adongbagna, Aka-eere, Agamolega … Abiɛa and Atindaana and their descendants have founded some lineages in the area of Dapore-Tindongo. These are called Abiɛabisi and Atindaanabisi respectively. All the male descendants of Asohɛ in Dapore-Tindongo refer to their lineage as Asorɛ-Kundamnebisi. They are also known by Asoorebisi. Some of the offspring of Asamsɔɔ migrated to live in Yipala. There are some of the Asamsɔɔ's sister's children living in Dapore-Tindongo. The latter is the Tindonseo/Asanabisi clan.

11.6 Tindaanaship in Dapore-Tindongo

Asamsɔɔ (the founder of Dapore-Tindongo) was the originator of tindaanaship in his clan. This was also by virtue of his position as the head of the family and the fact that he exercised jurisdiction over all the Earthgods (tingana) in Dapore-Tindongo. He was responsible for the rites connected with the Earthgods in his area: Akupelego, Aliya, Atamkuregan, etc. He was also responsible for harvesting the locust bean (dawadawa) and shea fruits in the territorial boundary of Dapore-Tindongo.

Bolgatanga tradition has it that Asamsɔɔ possessed supernatural knowledge and as such he was regarded with great veneration. His common wear was a string cap (miisi zuvɔka). He used also to be identified with a skin bag which contained the substance for his fetish. He had medicine of different kinds, which he used for both offensive and defensive purposes. It protected him against obnoxious spirits and witchcraft. Asamsɔɔ possessed two types of fetishes. One was in the nature of a pot (duko) and another was in the form of a horn (dongo). The former contained several roots and leaves, some of which were mystic in character. The fetish which was in the nature of a pot was called ‘Baya-yoore’ (meaning sexton's pot). It was from this juju pot that many men were initiated into the mystery of sextons or grave-diggers. The ‘dongo’ contained several charms and substances that were capable of causing the death of fairies (kinkito) and especially children believed to bring misfortune to their parents.

According to custom, after Asamsɔɔ's death, his fetishes descended on to his most senior son, Asohe. Both the ‘baya-yoore’ and kinkir-dongo were passed on to Asohe. According to the old men, one day Abiɛa (one of the brothers of Asohe and Atindaana) was sitting in his house when the hut in which he was leaning on caught fire and burnt him.Footnote 12 The burns later caused his death. Contrary to native custom, instead of Asohe (the most senior son) inheriting the property of Asamsɔɔ, including land, it was rather bequeathed to his junior wife's son, Atindaana. During this period the office of tindaanaship and the art of medicine were sharply distinguished in Dapore-Tindongo. Asohe's family maintained their position as possessor of the baya-yoore and the kinkir-dongo. Atindaana maintained his position as the trustee of the land in Dapore-Tindongo. He was in a loose expression referred to as ‘tindaana’.

11.7 Dapore-Tindongo tindanduuma

According to the old men, Asamsɔɔ was the first occupant of the area but not the originator of Dapore-Tindongo tindaanaship. It was his son Atindana who created tindaanaship in Dapore-Tindongo.Footnote 13 Abiɛa was the next successor to Asa'amsɔɔ. But he died a mysterious death so he did not occupy the position of a tindaana. As mentioned earlier,

1. Tindaana-Atindaana (was installed through direct transfer of authority from father to son and therefore was the first of the tindaanas of Dapore-Tindongo). The order of succession of Dapore-Tindongo tindaanaship after Atindana was the following:

2. Tindaana-Biro, installed by Abambire (Soe-Daana).

3. Tindaana Ayoka.

4. Asidengo, installed by Atia.

5. Azongo, installed by Abaa-Dongo.

6. Azieme, installed by Akantaam.

7. Tindaana-Zorkor, installed by Ayeleyine. In collaboration with the then Bolga-naba Azanam, he gave land to the first Roman Catholic missionaries who arrived in the town in Feb. 5th 1925.

8. Tindaan-Barega/Akatogre, installed by Akpasenaba.

9. Tindaan-Banga Ageero, installed by Agongo. All these installing elders were believed to have come from Asanabisi. Tindaan Banga was forcefully removed from the skin in 1976 and was replaced by Tindaan-Yuere. According to some of the elders of Dapore-Tindongo, Tindaan-Banga's assumption to the tindaanaship of Bolga was not customary because he was installed by the Asaanabisi soothsayer without the authority and supervision of the Tindonmoligo and Soe tindanduuma. Tindaan-Banga died in 1994.

10. Tindaan-Yuere Adingo (Yusepa) was installed in 1976 by Tindonmoligo Tindaana and Tindonsobiligo Tindaana, a practice that was contrary to native custom. He died on 18 Feb. 1992 and was buried on 6 March 1992. Since the death of the two tindaanas of Dapore-Tindongo – Tindaan-Yuere and Tindaan-Banga – there has not been any substantive tindaana installed for the section (2020). At the time of publication of this book the conflict between the Atindaanabisi and Aso'osebisi (Akundaminebisi) remained unresolved.

Figures 4A–D Azaare's handwritten maps of the genealogical family trees of Asa'amsɔɔ descendants.

Figure 5 Genealogical family tree of Asa'amsɔɔ descendants and tindaanas in their order of succession. Note: Those marked by asterisks are counted among the tindaanas of Dapore-Tindongo.

11.8 Conflict over Dapore-Tindongo tindaanaship

In Dapore-Tindongo there is controversy over the tindaanaship. This has remained the bone of contention between the Asohe's offspring and that of Atindaana's family. According to the story, during the time of Tindaan-Banga, the offspring of Asohe put in resistance against the installation of Abanga as tindaana. They said that his installation was illegal and contrary to Dapore-Tindongo's custom. The conflict between the two sub-clans reached its highest expression in 1976. During this period the family of Asohe (i.e. the Asore-Kundamnebisi) led by Sgt. Rtd. Apohre Aduko and Micheal Atongo marched to the compound of Tindaan-Banga with some police officers and forced him to abdicate and to surrender all the regalia pertaining to the Dapore-Tindongo tindaanaship. Even though he never resisted, he was beaten and the regalia forcefully taken away from him. The tindaan-kuga, which contain the spirit of the Dapore-Tindongo community, were conveyed to Asohe's family. It was alleged that Tindaan-Banga's installation was illegal owing to the fact that he did so in connivance with the Asanabisi tindaana.Footnote 14 He also did so without the authority and supervision of Tindonmoligo and Soe tindaanduuma. Having collected the tindaan-kuga and the regalia from Tindaan-Banga, the people of Dapore-Tindongo proceeded to install a new tindaana for the community. Contrary to native custom and the practices of installation of a Bolga tindaana, the Tindonmoligo and Tindonsobiligo tindaanduuma and some elders of Dapore-Tindongo, i.e. Ayuure's family, met and installed Ayuere Adingo through soothsaying. Ayuere Adingo became the new tindaana of Dapore-Tindongo, usurping the position of Abanga. It is sad to learn that a serious fight nearly resulted between the two tindaama clans on the 10 April 1990 if it had not been the presence of the erstwhile PNDC Chairman, Flt. Lt. J. J. Rawlings. This was during the commissioning of the National Grid (VRA) in Bolgatanga. The dethroned Tindaan-Banga died in 1994. The usurper, Tindaan-Ayuere Adingo, the recognized Tindaana of Dapore-Tindongo, ruled from 1976 to 1992. He died two years earlier than Tindaan-Banga.

Despite the situation in Bolgatanga, there is a growing tendency for the Tindaama clans (Tindonmoligo, Tindonsobiligo, Soe and Dapore-Tindongo), excluding the Atindaanabisi, to form an association – the Tindaama association. The aim of this association is twofold:

• To come together and fight for benefits from the Government.

• To confront or restrain chiefs from selling out lands in their areas of jurisdiction.

11.9 Taboos and beliefs of the Dapore-Tindongo tindaana

A summary of taboos and beliefs connected with the Dapore-Tindongo tindaana are as follows:

• He is forbidden to possess juju (evil medicine).

• He is forbidden to wear the fez (red cap). This is because his ancestor was never initiated into the mystery of chieftaincy, which requires him to wear the red cap.

• He must not wear jewelry or metal rings on the fingers.

11.12 Procedure of nomination, selection and installation of a Bolga tindaana

A tindaana is elected by traditional methods, a practice which has persisted since prehistoric days to the present. There are, however, little local variations. Under Bolgatanga custom those entitled to be made tindaanduuma of the Tindaama clans are Adaaba, Azagsibaga, Asamsɔɔ and Anafo because their forefather Abolga established the tindaanaship in Bolga town. The procedure is that when death occurs in any of the Tindaama Areas, the elders of the Tindaama will meet and choose one of the Tindaana's sons or his brother to fill the vacancy. He takes charge of the tindaana's affairs until such time that the funeral of the deceased is performed. The tindaanaship is not hereditary. His selection is so mixed up with sorcery that it is difficult to clearly understand how the tindaanaship passes from one generation to the next. But the little I learnt from a few knowledgeable men is that whenever there is vacancy on the tindaanaship, the elders of the tindaama family will invite a soothsayer to an open space or the house of the deceased tindaana. The arrangement of the installation is in the following manner:

• If a Dapore-Tindongo Tindaana is to be installed, it is the Asa'anabisi elders who supply the soothsayer/diviner and do the consultation.

• If it is a Tindonsobiligo Tindaana who is to be installed, it is the Tindonmoligo Tindaana who supplies the soothsayer and does the consultation.

• If a Tindonmoligo Tindaana is to be installed, it is the Tindonsobiligo Tindaana who supplies the soothsayer and does the consultation.

• If a Soe Tindaana is to be installed, it is the Dapore-Tindongo Tindaana who supplies the soothsayer/diviner while the Tindonsobiligo Tindaana does the consultation.

Inevitably, the choice of a successor by the soothsayer must fall on one of the offspring of the deceased tindaana. It could be his brother, nephew or daughter's son. Neither the elders nor the general public have the right under custom to reject the choice of the soothsayer as directed by the soothsaying. The new tindaana is presented by the elders of the installation authority to the public.

The new tindaana then provides some animals, which are slaughtered by the elders to pacify the gods and seek blessings and protection for the tindaana-elect. The skins of the animals slaughtered are presented to the tindaana-elect by the elders to serve as his seat. He is also robed in a miisi-zuvoka. It is worth noting that tindaanaship in Bolgatanga, and the Frafras in general, is never obtained by wealth or bribery. No one can become a tindaana by virtue of his status, influence or personality. Tindaanaship is such that even if the community grows large and split into small units, it is circulated amongst the different family units who are genealogically related whether within or without the territorial boundary of the town.