The link between diet and health is well established( Reference Willett 1 , Reference Sofi, Cesari and Abbate 2 ), with nutrition recognised as a major modifiable determinant of chronic disease( 3 ). Despite this, the rates of non-communicable chronic diseases( 4 , Reference Beaglehole, Bonita and Horton 5 ), including overweight and obesity( 6 , Reference Ogden, Carroll and Curtin 7 ), are increasing globally. Although population awareness of the link between poor dietary practices and poor health outcomes exists( Reference Furst, Connors and Bisogni 8 , Reference Lake, Hyland and Rugg-Gunn 9 ), this is often not reflected in behaviour( Reference Lobstein and Davies 10 , Reference Backett 11 ). Research has reported that consumers face difficulty in translating their understanding of health into healthful food purchases( Reference Wiggins 12 – Reference Glanz and Mullis 14 ), with consumers facing trade-offs between different values each time they choose a food( Reference Ronteltap, Sijtsema and Dagevos 15 ). Food choice is influenced by a myriad of competing, accommodating and negotiating factors( Reference Bawa and Avijit 16 , Reference Connors, Bisogni and Sobal 17 ) involving individual ideals, social relationships and food contexts( Reference Furst, Connors and Bisogni 8 , Reference Story, Kaphingst and Robinson-O’Brien 18 ), all of which have been widely documented in the literature( Reference Turrell, Bentley and Thomas 19 – Reference Pollard, Kirk and Cade 22 ).

While health is frequently mentioned as a consideration in food choice behaviour, its impact and importance have been under-researched( Reference Givens 23 , Reference Roininen, Tuorila and Zandstra 24 ). Health has been described as having heterogeneous dimensions in personal food systems( Reference Connors, Bisogni and Sobal 17 ). In order to explore the role of health in consumer food choice, it is important to consider lay health theories( Reference Furnham 25 ) and the belief systems surrounding understandings of the meaning, motivations and importance of health to people( Reference Hughner and Kleine 26 , Reference Moorman and Matulich 27 ). Individual diversity regarding health has led to the identification of numerous themes defining health, from a ‘modern way of life’ to ‘a functional ability’( Reference Hughner and Kleine 28 ). Similarly, during the food decision-making process, the value of health differs between consumers( Reference Ronteltap, Sijtsema and Dagevos 15 ). Health consciousness( Reference Michaelidou and Hassan 29 – Reference Mai and Hoffmann 31 ), health involvement( Reference Pieniak, Verbeke and Scholderer 32 , Reference Olsen 33 ), health concern( Reference Schifferstein and Oude Ophuis 30 , Reference Sun 34 ) and nutrition self-efficacy( Reference Mai and Hoffmann 31 , Reference Anderson, Winett and Wojcik 35 , Reference Saarela, Lapveteläinen and Mykkänen 36 ) have all been shown to affect the purchase of healthy food items and the motives behind individuals’ behaviour. There is however limited research to date that explores the influence of health on food choice in a shopping context.

Grocery shopping is a basic element of consumer behaviour( Reference Bawa and Avijit 16 ), with food purchased in the supermarket contributing a large proportion to the household diet( Reference Ransley, Donnelly and Khara 37 ). Consequently, supermarkets have been proposed as a key setting for public health interventions( Reference Glanz and Yaroch 38 , Reference Ni Mhurchu, Blakely and Wall 39 ). It has been suggested that the local food environment can impact overweight and obesity through facilitating improved consumer choices and opportunities( Reference Story, Kaphingst and Robinson-O’Brien 18 , Reference Morland, Diez Roux and Wing 40 ). As gatekeeper of the food supply( Reference Hawkes 41 ) and an important contributor to neighbourhood nutrition( Reference Morland, Wing and Diez Roux 42 ), supermarkets are ideally placed to influence health( Reference Glanz, Bader and Iyer 43 ).

To date, consumer food behaviour in the supermarket has mainly been examined through the use of shopping lists( Reference Schmidt 44 ) and supermarket till receipts( Reference Ransley, Donnelly and Khara 37 , Reference Ransley, Donnelly and Botham 45 , Reference Rigby and Tommis 46 ) as an index of food consumption or as an estimate of nutrient intake. However, till receipt studies, for example, focus only on actual purchases and are unable to give any insight into the motives for, or justifications of, food choice behaviours. In order to influence people’s dietary behaviour, we need to understand what disposes consumers’ practice. Qualitative methods enable an in-depth appreciation of the role of health considerations in shaping food choices.

The present study formed part of a larger project examining the way in which health is depicted in the context of food shopping by consumers with varying levels of health consciousness across the island of Ireland. Further analysis was conducted to gain an understanding of and insight into how shoppers conceptualise health during a grocery shop by examining use of the word ‘health’ and/or its derivatives within each shopper’s discourse. To do this, the think-aloud technique was employed to gain insight into shoppers’ thought processes, motivation and ultimate decision making in a ‘real life’ setting in a supermarket, while conducting their normal weekly food shop. Few studies have explored the concept of health within a shopping context using a qualitative approach. The current research provides observation into a previously under-examined yet important dimension of food choice behaviour.

Methods

Study participants and recruitment

Participants were main household shoppers aged 18 years and over, and were recruited through a market research company. Efforts were made to ensure the diversity of the profile of participants based on a number of key demographic characteristics such as age, gender, socio-economic status and household size. In addition, participants’ self-reported health consciousness was calculated using a general health interest scale( Reference Roininen, Lahteenmaki and Tuorila 47 ).

Fifty participants were recruited, n 30 from the Republic of Ireland (ROI), in Dublin and n 20 from Northern Ireland (NI), in Belfast. The study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by Queens University Belfast Research Ethics Committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. All participants received a study information letter to facilitate informed consent and consulted the researchers if they required additional instruction or clarification. Participants were offered monetary compensation in recognition of their participation. Characteristics of the participants can be found in Table 1.

Table 1 Characteristics of the participants (n 50) aged over 18 years and who represented the main household shopper, Dublin, Republic of Ireland and Belfast, Northern Ireland

Study design

The study was conducted using the think-aloud technique, a verbal analysis protocol( Reference Ericsson 48 ) previously used for analysing consumer behaviour( Reference Saarela, Kantanen and Lapveteläinen 49 , Reference Barnett, Muncer and Leftwich 50 ). This is a process-tracing method( Reference Reicks, Smith and Henry 51 ), used in the current study to trace the process of food choices made in conducting a supermarket shop. The think-aloud technique was used within an accompanied shop. This involved researchers accompanying participants to the supermarket where they generally carried out their weekly shop( Reference Reicks, Smith and Henry 51 ). Permission to conduct research in-store was gained from the retail chains of each of the stores in which participants shopped. Prior to commencing the task, participants were trained in the think-aloud methodology( Reference Barnett, Muncer and Leftwich 50 , Reference Ericsson and Simon 52 , Reference Payne 53 ). Two products were displayed on flash cards; participants were asked to choose between the products and explain the reasoning behind their choice. Following this, participants proceeded to carry out their normal weekly shop. They were instructed to think aloud at all times concerning their shop and to talk about the items they were looking at and registering mentally in addition to anything they were doing. They were encouraged to verbalise what information, if any, they were attending to or searching for on different products. The rationale underpinning the use of the think-aloud methodology was to examine participants’ reasoning behind their decision making and product choice in the context of their normal food shop.

Throughout the task, participants were observed by the researcher and if they became silent were reminded to think aloud with a structured series of prompts such as ‘What are you looking at?’, ‘Where are you now?’ and ‘What are you thinking?’. Save for this interaction, researchers did not enter into conversation with participants during the accompanied shop; they acted only as a shadow companion for participants and as a ‘listener’ to their discourse. It should be noted that when recruited to the study, participants were told only that they were taking part in a shopping study and at no stage was it suggested that the study related to health.

When the participants had completed their shopping they went to the checkout to pay, at which point the task was concluded and the recording finished. Participants were recorded during the task using a discreet dictaphone attached to their outer clothing. The resulting recording was fully transcribed for analysis. All information that could lead to participant identification was removed or modified from the resulting transcripts. All data were collected concurrently in the ROI and NI, between February and March 2011. Accompanied shops lasted between 15 and 90 min.

Data analysis

NVivo 9 qualitative software was used to assist with the analysis of the data. For the purpose of the present study, accompanied shop transcripts were analysed to examine how health, if at all, was invoked as a motive for people’s food choice decisions. In order to examine how the concept of health was articulated during the grocery shop, transcripts were studied for references or inferences to health. All mentions of health (defined by the terms ‘health’, ‘healthy’, ‘healthier’ or ‘healthiest’) were identified. Further to this, the researchers (M.C.O.B. and L.E.H.) selected alternative phrases implying health, such as those noting or suggesting the nutritional composition of a food, the perceived beneficial health properties of a food or reasons why a particular food was purchased or avoided without directly addressing the terms ‘health’, ‘healthy’, ‘healthier’ and ‘healthiest’ within the transcripts, e.g. ‘It’s good for you’, ‘It’s low in fat’. All accompanied shop transcripts were reviewed to generate a table of participant quotes. Following this a thematic analysis was conducted. Themes were derived through inductive analysis( Reference Boyatzis 54 ) whereby two researchers (M.C.O.B. and L.E.H.) coded the table of quotes. To address the issue of inter-coder agreement, a book of codes and definitions was developed based on the first three pages of participant quotes and applied for subsequent analysis. The process of coding was iterative and reflective; new codes and any discrepancies were discussed and consented by the researchers( Reference Fereday and Muir-Cochrane 55 ). Themes were identified by analysing and grouping the codes together and using quotations to illustrate the concepts found within the data( Reference Braun and Clarke 56 ). Verbatim quotes are displayed below, with participant number, gender of the participant (F, female; M, male) and the location in which the participant resides, respectively, following in parentheses. Items or actions perceived as ‘healthy’ or ‘unhealthy’ by participants are based on their own beliefs and may not be considered as such by health professionals.

Results

The nature of shoppers’ talk about health while food shopping

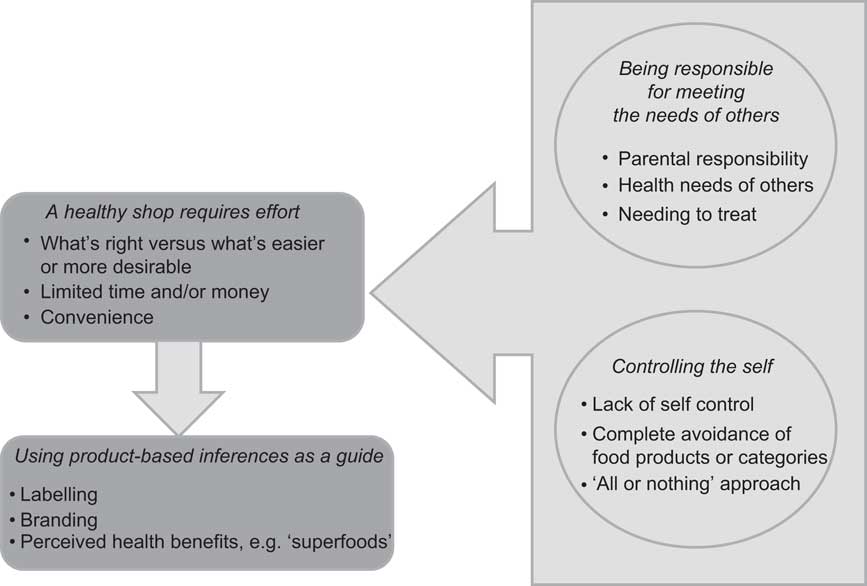

Through thematic analysis of the interview transcripts, a number of themes representing how shoppers talked about health in relation to their purchase decisions were identified (see Fig. 1). Responsibility for others and the need to exercise self-control to avoid unhealthy food choices were found to underpin the purchasing decisions of shoppers. Many purchase decisions, where health was considered, related to the requirements or preferences of others in the household, where shoppers felt responsible for making the ‘healthy’ choice. At the same time, the analysis revealed that shoppers believed avoidance of unhealthy foods required self-control, often resulting in avoidance of whole aisles in the supermarket. Perhaps in light of this, shoppers felt it was difficult to shop healthily and to avoid unhealthy choices, meaning that the experience of healthy shopping or purchase decisions was viewed as effortful. The analysis also revealed that participants tended to refer to cues to healthiness that were provided by the product and its packaging, using this as a strategy to ensure the ‘healthy’ choice.

Fig. 1 Schematic illustration of how health is represented in consumers’ food purchasing decisions. While shopping, participants, as gatekeepers, considered health in relation to meeting the needs of others, while at the same time identifying the need for self-control in relation to avoiding ‘unhealthy’ food choices. As a result, making healthy food choices and avoiding unhealthy choices was seen as something that required effort or was difficult to do. Shoppers often relied on product-based cues or inferences to help them to make the healthier choice

Being responsible for meeting the needs of others

Health was frequently spoken about through making choices based on the requirements or requests of family or other household members. Responsibility and concern for the well-being of others was dominant as many shoppers seemed to adopt the role of gatekeeper or caregiver within the household. Although these were individuals making choices, their selection related to others and was constrained by the likes, dislikes, needs and wants that came with that:

‘I need some bread. I’ll get something small, I’m off bread, but the rest of them aren’t, they’ll eat it, small [name of brand] wholemeal pan.’ (P27, F, ROI)

For instance, participants with families frequently based their decision to purchase healthy foods around their children or partner. They took control in making the healthy choice and in taking responsibility for others they endeavoured to ensure a healthy, wholesome diet. Often, participants chose healthier products than those desired or preferred by other members of the household, guarding against unhealthy choices:

‘I have two step-kids and they come to visit every other weekend and they’re coming this weekend, so I always like to have more, because if they’re hungry, I would say, look, would you like to have scrambled eggs, you know, rather than lifting chocolates and crisps all the time, give them a snack.’ (P84, F, NI)

Several participants mentioned the nutritional composition of food items and the importance of attempting to make their child eat certain foods noted for their health benefits. Many parents considered the risk/benefit paradigm of choosing perceived overall less healthy food products fortified with wholesome grains, vitamins and minerals to ensure consumption of these vital food groups and nutrients. In one instance a participant remarked at the assumed levels of sugar in a type of flavoured milk. None the less, it was felt that the risk v. benefit to her child was positive due to the fact that her children would ultimately be consuming milk as a result. Another remarked:

‘I’m trying to trick the kids into eating some healthy bread, they love the white bread there’s some of these 50/50s… take it out of the freezer make the kids’ sandwiches, they’re thinking they’re getting white bread but fingers crossed they get a bit of wholegrain in it.’ (P20, M, ROI)

It was also interesting to note the purchase of multiple varieties of the same food item for different family members in response to a nutritional need, preference or condition. This was often related to health reasons, for example full-fat milk for a baby ‘because the baby has to drink the full-fat stuff’ (P09, F, ROI) or skimmed milk for somebody watching their weight.

Being responsible and showing consideration for household members’ dietary requirements due to food intolerance or adherence to a dietary plan were evident:

‘...my wife’s on the [name of brand] diet so she’s asked me to get the [name of brand] yoghurts, so I’ll try and look for them.’ (P14, M, ROI)

In contrast, shoppers also made reference to health in relation to the purchase of treat items for other members of the household. This finding runs counter to their perceived responsibility to make healthy food choices for others. A responsibility to treat was evident. Often as a display of care or to fulfil an agreement, less healthy foods or ‘treat’ items were chosen:

‘I always think it’s nice for the kids to have a wee treat, because they’re very very healthy kids and a treat would be like a [name of brand] or a chocolate chip cookie for their supper, so I’m just looking to see which ones, so I’m looking for [name of brand], there they are.’ (P84, F, NI)

In addition to considering the needs of household members, shoppers were also mindful of guests to their house. Shoppers felt a duty to choose treat items such as cakes and desserts or luxury foods for dinner, for their visitors. This was rarely an opportunity to be healthy as these occasions were perceived as singular events where a diet or habitual eating behaviour could be overlooked for the opportunity to indulge:

‘...if I had people planned to come over for an evening meal or a Sunday lunch or whatever, then obviously I would be buying other little items. The luxury items, the cakes, and the biscuits and the desserts….’ (P01, F, ROI)

Controlling the self

This theme was defined by participants’ need to ‘control’ the self in order to make the healthy choice. Avoiding products perceived to be unhealthy was repeatedly observed during the accompanied shop. Participants cited a lack of self-control as the reason to avoid certain food groups or entire aisles, explaining that they needed to avert their attention away from seeing particular items; seeing them served as provocation. In most cases, participants felt that if they didn’t avoid these foods and/or aisles altogether they would binge or overindulge; therefore refraining in the first instance was the favoured strategy:

‘I tend not to look down there, that’s where all the beer is and I get tempted.’ (P20, M, ROI)

‘I’m thinking about those cakes but I’m not going to get them because if I get them I’ll eat them.’ (P98, F, NI)

Product avoidance was directly linked with temptation as participants remarked that they ‘have to walk on by’ items such as cakes, biscuits, crisps and sweets to prevent selection and subsequent consumption. Temptations, however, were sometimes justified as a contradictory and celebratory approach to avoidance. Many shoppers allowed these foods if they were a ‘treat’ item. During their shop numerous participants purchased ‘treat’ items with the rationale that they felt deserving of a food that was not considered healthy. It was difficult to be ‘good’ all the time and so it was standard practice to permit these ‘bad’ items as participants perceived them as allowable ‘for weekend eating’, ‘as I’m usually very healthy’ or ‘because I need a boost’:

‘Now I’m heading down to the ham, ham is my concession for my little fat.’ (P16, M, ROI)

‘We’ll be naughty and have a little treat [bar of chocolate].’ (P01, F, ROI)

The purchase of perceived healthier alternatives while avoiding their unhealthy counterparts was another established technique participants utilised in order to control their purchase of unhealthy foods. Through this approach shoppers felt they were undertaking healthy behaviours by avoiding unhealthy products while simultaneously purchasing a surrogate item so as not to feel deprived of enjoyment:

‘I never go for the likes of chocolate biscuits or crisps or anything, the only crisps is you know the wee... I don’t know if they have them here so I will go round to see light bites, [name of brand] light bites or something you call them, chilli infuse….’ (P100, F, NI)

Often self-control over food purchase was aligned to self-control over diet and restraint regarding food consumption. Dieting to lose weight or being weight conscious was mentioned periodically and food items were often chosen to reflect this:

‘…I might get some Jaffa cakes. I’m very weight conscious when it comes to certain

things and they’re not high in calories, they’re low….’ (P17, F, ROI)

Healthy choices require effort

Making ‘healthy’ food choices did not come naturally; in fact the opposite was found to be true – healthy choices were presented as requiring effort. Participants presented a clear picture that effort was required to resist temptation and to try to do the ‘right thing’ in relation to the food choices they made. Making healthy choices was generally believed to be difficult, given a range of external and internal pressures including time and money. Consequently, shopping frequently resulted in perceived unhealthy food purchases.

Time constraint was mentioned as a reason for making the selection of healthy foods more difficult, motivating the purchase of ‘unhealthy’ products in-store. It was remarked that processed foods such as pizzas and jars of sauces were believed to be handy for quick meals that required little preparation and cooking. Choosing such items also meant less pressure when it came to dinner time; items conducive to an ‘easier’ lifestyle were popular with participants:

‘It’s dried pasta, with a herby sauce on it and again it’s good with sausages or something. It wouldn’t be the healthiest, but it’s quick sometimes.’ (P90, F, NI

)

‘I’ll grab some [name of brand] because they’re on offer too, they’re only £1, it’s easy enough. All the bad things.’ (P83, M, NI)

Resisting the temptation of unhealthy food choices required discipline on the part of shoppers. They noted that unhealthy or treat foods were consistently on promotion, tempting them to select foods they would rather not consume. A money-saving item regardless of its (perceived) nutritional composition was hard to pass up. It was easier to select the item than resist the purchase; therefore effort was required on the part of the shopper to avoid the easy option. The choice of a healthful food item required a more analytical, in-depth decision-making process:

‘The only thing is, sometimes I would buy these here little biscuits and they’re not on my list because they’re not healthy, but because they’re on offer.’ (P84, F, NI)

‘I’m looking for value and steak mince. They normally have two for 5 Euros but don’t think it’s steak mince, there is a difference when you go to make it, so I’m actually prepared to pay a bit more than 5 Euros and I’ll go for 800 grams of steak mince instead of two packets for a fiver for a normal mince, I suppose, make a few dinners out of it and keep for the next day.’ (P22, M, ROI)

Some shoppers remarked that they ‘should’ purchase a certain food as it was perceived as ‘healthy’. This feeling they should ‘do the right thing’ meant more effort was required in making their food choice decisions. However, although shoppers recognised that they ’should’ make the healthy choice, there was an accompanying admission that the corresponding behaviour was often different:

‘I don’t want oranges, I couldn’t be in the mood to eat fruit at the moment, but I know I should but I don’t feel like it.’ (P02, F, ROI)

‘I would usually buy a packet of peanuts and put them in the press, suppose I should be eating different kind of nuts but just to keep my sanity I get large packet of [name of brand] every week. That’s them isn’t it? Yeah that’s the big bag original salted [name of brand].’ (P20, M, ROI)

Participants suggested that internal trade-offs occurred regularly during the food shop. These took the form of lack of time v. health, lack of money v. health and apathetic behaviour v. health (or a combination of all). To do a healthy shop was depicted as a mental battle that was frequently lost to other factors. It was proposed that these factors made making healthy purchases an ordeal which led them to selecting unhealthy food items; doing the ‘right thing’ took too much effort.

Using product-based inferences as a guide

In order to make responsible purchases for others and to exercise self-control we have seen that healthy purchases were effortful purchases. In this final theme we see that participants noted the cues to healthiness that were provided by the product and its packaging.

Participants regularly used their knowledge of foods to help them while shopping. They relied on their experience, familiarity and understanding of foods as a guide to healthy choices. During the shop, health was frequently talked about directly or indirectly using product-based inferences such as food composition, disease-fighting properties, nutrition labelling and brands. These intrinsic and extrinsic factors offered guidance for making healthy choices. For example, noting the nutritional benefits of foods, participants would usually acknowledge nutrition in terms of the energy (calorie), fat or nutrient content of a product.

A number of participants felt they were aware of the reported health benefits of certain foods and purchased items with this in mind. ‘Superfoods’ were referenced as a group of foods distinguished by their superior health properties:

‘Broccoli we believe it is one of the super vegetables and at one stage my wife used to buy blueberries and because they help lower your cholesterol, but now she is on tablets which help out but she might still occasionally take them.’ (P16, M, ROI)

Understanding the nutritional composition of foods, or believing they understood it, and choosing products based on this information was common practice. Decisions to purchase were habitually determined through this approach. Moreover, food choices were frequently based on the amount of specific nutrients, for example low-fat or reduced-salt and -sugar items. The purchase of perceived healthier alternatives was often standard during the shop. Shoppers were making compromises in order to be healthy. For example, brown bread instead of white bread, fruit juice in place of fizzy drinks and extra lean rather than regular mince:

‘...they are horrifically high in calories which shocked me, per serving 233... I thought I wouldn’t do that, that’s a meal, that’s 230 calories in my rice and I’d eat the whole packet, so I’m not doing it, I’m not buying it and I’ve got the kids thinking that way as well.’ (P90, F, NI)

‘I would make them out of turkey because it’s healthier than making them out of red meat, although we do eat red meat, but I think it’s healthier to have the turkey mince rather than buying the steak ones.’ (P84, F, NI)

Almost all participants mentioned health in relation to branding at some point throughout their shop. The purchase of certain brands was routine for most, with specific brands perceived as healthier than others. In particular, products endorsed by a well-known weight management brand were repeatedly recognised as ones that were trusted to be low in calories and low in fat:

‘[name of brand] is usually okay and at least you know it’s not too much weight.’ (P02, F, ROI)

Food items labelled as ‘healthy’ were an important influence on decision to purchase. Many participants remarked that they had confidence in products that claimed to be low-fat, reduced-salt or -sugar or fortified with vitamins and minerals. One participant remarked that the sight of blue packaging with reduced-fat labelling encouraged a sale:

‘I don’t know maybe it’s something in your head when you see something in blue and it says reduced fat and you think it is, but if you really read it it’s probably not much difference you know, but I buy it anyway.’ (P88, M, NI)

However there was some ambiguity surrounding products marketed as ‘healthy’, and a number of participants mistrusted the claims. One participant commented that the positive advertising surrounding a healthy product was misleading as, on examining the label, the product was found to be high in calories:

‘...the likes of the [name of store] ones are an awful lot cheaper than the [name of brand], but again their baked bars are high, they advertise them as being these healthy things, but they’re not really, if you read.’ (P90, F, NI)

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to observe the nature of people’s discourse regarding health while supermarket shopping. The study provides an understanding of the influence of health during a food shop from a consumer’s viewpoint. Responsibility for others and the perceived need to illicit strict control to avoid ‘unhealthy’ choices played a dominant role in how health was talked about during the accompanied shop. Consequently healthy shopping was viewed as difficult and effort was required to make the healthy choice, with shoppers relating to product-based inferences to ensure the healthy choice.

Health is often one of the values considered as a reason to shop or to motivate the purchase of a specific product( Reference Furst, Connors and Bisogni 8 , Reference Story, Kaphingst and Robinson-O’Brien 18 ); however, the relationship between health orientation and shopping behaviour remains unclear. The current analysis provides further interpretation of the influence of health as a motivator for food choice in the context of food shopping as well as enabling further understanding of how health is manifested in consumers’ food choice decisions.

Although the study participants were not explicitly questioned about the role of health in their food choice decisions, the interpretations of these themes are similar to those reported in a comprehensive review of lay views of health( Reference Hughner and Kleine 28 ). Hughner and Kleine revealed themes such as ‘health is a moral responsibility’, ‘disparity between health beliefs and behaviours’, ‘health is maintained through internal monitoring’ and ‘health is constraint’( Reference Hughner and Kleine 28 ) that are comparable to the findings of the current study, such as ‘being responsible for the needs of others’, ‘knowing what foods are good for me but not buying them’, ‘controlling the self’ and ‘time and money constraints influencing the purchase of healthy foods’.

In the present study it was noted that provisioning for others – family, partners and friends – was at the heart of many health-related purchasing decisions in-store. Health was a consideration with regard to the needs and preferences of others. Research has shown that people’s shopping and behavioural decisions are influenced by their responsibility for others (e.g. references Reference Connors, Bisogni and Sobal17, Reference De Brun, McCarthy and McKenzie57–Reference Lake, Rugg-Gunn and Hyland59). Concern for significant others has been found to influence food shopping goals( Reference Ong 60 ). The concept of health became visible through discussions of responsibility, with consumers striving to buy healthy items for those they care for, a finding supported by previous research( Reference Nørgaard and Brunsø 61 ). Shoppers routinely played the role of gatekeeper for the household. It has been noted that parents often put the needs of their children first while endeavouring to apply the concept of balance to their eating habits( Reference Falk, Sobal and Bisogni 62 ). Encouraging children to eat more healthily was evident from the discourse of the present study. Family members have been shown to play a dominant role in influencing and acquiring foods which in turn support the nutritional needs of the household( Reference Ransley, Donnelly and Botham 45 , Reference Epstein, Gordy and Raynor 63 ). Those with children frequently based their purchase decision around their child’s wants and needs( Reference Lake, Rugg-Gunn and Hyland 59 , Reference Rossow and Rise 64 ). Correspondingly, research has found that parents agreed to purchase their children’s food requests 45–66 % of the time( Reference Carson and Reiboldt 65 ). Participants shopping for themselves and a partner exhibited comparable behaviour with some purchasing foods they were aware their partner liked, even if it was not to their own taste. Cohabitation can lead to altered or renegotiated consumption patterns resulting in positive changes to healthy eating behaviour( Reference Ristovski-Slijepcevic and Chapman 66 ). It has been reported among men that living with a woman was found to have a positive influence on their diet( Reference De Brun, McCarthy and McKenzie 57 , Reference Lake, Rugg-Gunn and Hyland 59 ). The existence and role of such responsibility and influence on consumer food choice should be considered by public health agencies in developing campaigns to encourage healthy eating.

Participants purchased foods selected specifically to address existing health conditions such as elevated blood cholesterol or to prevent illness and maintain health. This finding is consistent with data reported in other qualitative studies where participants’ and their families’ medical history influenced their food choice and healthy eating habits( Reference Falk, Sobal and Bisogni 62 ). An interesting tension within the current study, however, was the purchase of unhealthy food and a shopper’s perceived responsibility to treat others, be they family members, friends or guests. Self-licensing has been shown to increase hedonic consumption( Reference Witt Huberts, Evers and De Ridder 67 ). Actively relying on a reason or excuse to validate the purchase of a ‘vice over virtue’ was common( Reference Witt Huberts, Evers and De Ridder 67 ). On these occasions shoppers allowed ‘disallowed’ foods, through the selection of perceived ‘treats’, frequently at the weekend or because they were expecting visitors, a justification for consumption. Shoppers negotiated the value of foods in relation to the exercise of caring; sometimes caring meant buying healthy foods and at other times it meant providing treats. A health–pleasure trade-off with regard to family decision making and food choice has been reported elsewhere( Reference Nørgaard and Brunsø 61 ). A comparable association in the literature, where people attempted to proportion their food choice and consumption between preferences and values, found that these food choice values were often in conflict( Reference Connors, Bisogni and Sobal 17 ). Within the present study, it was also found that although parents selected treat foods for their children these were sometimes perceived as ‘healthier’ versions of original requests, while endeavouring to provide nutritious, wholesome foods to support health.

Deliberate purchase of foods that were designated as unhealthy was often conceptualised in terms of treating. This was a more common and a more acceptable strategy in terms of treating others. When controlling the self shoppers more commonly claimed to avoid foods they perceived as unhealthy, such as chocolate, cakes and biscuits. Unlike previous studies looking at interpretations of healthy and unhealthy eating (e.g. reference 68) or at decisions relating to food choice (e.g. reference 17), where a balanced diet was conceptualised as healthy eating and a practice of shoppers’ personal food system, throughout the current investigation, when speaking about or implying health while supermarket shopping, participants did not mention the term ‘balance’. In fact, there was no evidence that seeking balance was a consideration throughout the shop. Many health professionals and health campaigns focus on encouraging ‘a balanced diet’; however, the current research suggests that balance is not a concept consumers apply to their food purchasing decisions.

Furthermore, when faced with other priorities, temptations and pressures, these factors dominated. Constraints imposed by lack of time and money meant that shoppers frequently chose convenient, less healthy food options. Price in addition to sensory factors has been shown to influence purchase decisions( Reference Furst, Connors and Bisogni 8 , Reference Inglis, Ball and Crawford 69 ). Similarly, it has been reported that lack of time to prepare and cook foods resulted in smaller intakes of fruit and vegetables( Reference Lake, Rugg-Gunn and Hyland 59 ). A busy work life and subsequent altered meal patterns appear to influence the purchase of unhealthy foods( Reference Anderson, Winett and Wojcik 35 ). Ideals are a common influence on food choice( Reference Furst, Connors and Bisogni 8 , Reference Pollard, Kirk and Cade 22 ). Referring to what should be purchased or consumed was considered by a number of shoppers who spoke with an ‘I know I should’ mentality. Previous research has noted that sales promotions can encourage a change in consumers’ consumption patterns( Reference Hawkes 70 ).

It has been reported that an interplay of shoppers’ influences, personal systems, value negotiations and strategies was found to affect their purchase-based decisions( Reference Furst, Connors and Bisogni 8 ). As previously mentioned, shoppers’ values were often in contrast to their food selection( Reference Connors, Bisogni and Sobal 17 , Reference Lappalainen, John and Gibney 71 ). The current research found that many shoppers believed healthy shopping required effort, and factors such as self-control and impulsivity influenced behaviour and were evident in shoppers’ leverage of food choice and health. As a result, it was felt that healthy choices were often difficult to make under supermarket conditions. Making a healthy food choice was found to require more mental effort( Reference Mai and Hoffmann 31 ). An assessment of the food is required if a shopper is to purchase and eat healthily( Reference Mai and Hoffmann 31 ). It is important therefore to consider that if a specific health behaviour is seen as an extension of ‘work’, it is likely to negatively affect engagement with change. To improve intervention design, a method incorporating a comprehensive knowledge of the behaviour to be changed should be applied( Reference Michie, van Stralen and West 72 ). This system should be adopted by health promoters trying to encourage healthy behaviour change while food shopping.

Health claims have been shown to create a favourable impression on shoppers( Reference Drichoutis, Lazaridas and Nayga 73 ). In particular, brands marketed as healthy were perceived to be healthier and were popular among shoppers. A migration towards the purchase of foods low in fat, high in fibre or those with a reduced sugar content was also observed as shoppers commented on their selection, with certain products and their healthy inferences a stimulus towards good health. This is consistent with findings which show that ‘healthfulness’ is one of the most important food characteristics for consumers( Reference Robinson and Smith 74 ). Within the present study, those aligned to a weight loss or heart healthy intention were especially prominent. Shoppers endeavoured to pick healthy, nutritious foods, as was evident from transcripts relating to an interest in and analysis of nutritional labelling and the selection of ‘superfoods’ with potential superior health properties. It has been reported that through the use of nutritional labelling shoppers undertake to avoid negative nutrients in foods( Reference Drichoutis, Lazaridas and Nayga 73 ). Little research has been undertaken to investigate consumers’ thinking while choosing foods in the supermarket setting, and the current research provides insightful, original evidence in this field. We have identified a number of opportunities that could be utilised by stakeholders such as health professionals, policy makers, industry and consumer organisations to help reduce the effort consumers feel is required to make healthy choices.

Limitations of the study

A number of limitations should be noted. The higher socio-economic classes (A, B, C1) are overrepresented in the sample, as are high health conscious individuals. With regard to the think-aloud method, it could be argued that participants only expressed conscious insights they could articulate, which may not reflect fully on their decision-making processes. However, this is a limitation for many methods examining views and beliefs, where it is often not possible to access subconscious thoughts. This think-aloud method has been shown to present valid expressions of thought processes( Reference Simon and Kaplan 75 ) and is an established qualitative analysis technique( Reference Barnett, Muncer and Leftwich 50 , Reference Reicks, Smith and Henry 51 ).

Conclusion

Through the medium of supermarket shopping it was possible to observe people’s food choice behaviour. By exploring the contextual meaning of health exclusively, the present study increases understanding of the role of health in food choice. Consumers’ responsibility to provide for others was at the heart of many shopping decisions regarding health, with shoppers assuming the position of gatekeeper in relation to others’ food choices. However, healthy food shopping was often seen as effortful, which may pose a significant barrier to engaging in healthy food choice behaviour. These study results suggest a number of opportunities that stakeholders such as public health agencies and the food industry could take advantage of to make healthy shopping less effortful and more pleasurable for consumers.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors wish to acknowledge Dr A. McGloin’s contribution to the project and her comments on the manuscript. Financial support: This research was funded by safefood Ireland as part of a large-scale study on shopping behaviour on the island of Ireland. safefood Ireland had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: M.D., A.M., J.B. and M.R. designed the research. M.C.O.B. and L.E.H. acquired and analysed the data. The research team met to interpret the results. M.C.O.B. and A.M. prepared the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: The study received approval from Queens University Belfast Research Ethics Committee.