INTRODUCTION

The consequences of minor trauma involving a head injury (MT-HI) in independent older adults are largely unknown. Head injuries are a frequent reason for emergency department (ED) visits, representing about 50,000 visits annually in Canada. The great majority of these head injuries are qualified as minor or mild. 1 There is an increasing awareness regarding the long-term impact of minor trauma involving head injuries (MT-HI) in all age groups.Reference Andersson, Bedics and Falkmer 2 , Reference Katz, White and Alexander 3 Long-term impact is associated with functional and cognitive statusReference Kessler, Williams and Moustoukas 4 , both of which are reported to be directly linked to patient independenceReference Callaway and Wolfe 5 . However, there is a relative lack of data on long-term effect of this kind of trauma in the elderly population.Reference Callaway and Wolfe 5 This is of concern because the elderly population is aging and life expectancy is growing.Reference Marx, Hockberger and Walls 6 We are therefore likely to observe an increase in MT-HI in this population in the next few years.Reference Depreitere, Meyfroidt and Roosen 7

Data regarding MT-HI in the older population is scant. In a retrospective cohort study of 277 patients, Testa et al. studied the effects of age on recovery after a moderate or mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) compared to an orthopedic injury.Reference Testa, Malec and Moessner 8 Their results suggested that patients 50–89 years of age, particularly those with mTBI, were significantly more dependent compared to younger patients, as measured with the Independent Living Scale (ILS) at one year post-injury. More recently, Sirois et al. and the CETI (the Canadian Emergency Departments Team Initiative) evaluated functional decline in older patients after different types of minor trauma, including MT-HI,Reference Sirois, Emond and Ouellet 9 and found that approximately 18% of their population had a functional decline at six months.

Furthermore, older adults often sustain more than one injury in the same event.Reference Tintinalli and Stapczynski 10 Leong et al. studied the effect of a co-injury (injury to another part of the body) with a mTBI in young patients and found that their functional outcome was significantly worse than those without a co-injury.Reference Leong, Mazlan and Abd Rahim 11

To our knowledge, no prospective study has attempted to assess the long-term impact of a MT-HI on the functional outcome of independent elderly patients compared to those with a minor trauma not involving the head. We hypothesized that MT-HI may impact functional and cognitive status among older adults discharged from the ED and that a concomitant injury could cause a more important decline in MT-HI patients.

OBJECTIVE

The main objective of this study was to assess the functional status in patients over 65 years of age, six months after a minor trauma including a head injury. The secondary objectives were to assess: 1) the cognitive status in patients over 65 years of age, six months after a minor trauma including a head injury, and 2) the effects of a concomitant injury on the functional outcomes of patients who sustained a MT-HI.

METHODS

Population

This prospective cohort study was conducted in eight Canadian teaching hospitals by the CETI. Patients included in our study were recruited between May 2009 and January 2014. Patients were included if they were: 1) aged 65 years or older, 2) presenting to the ED with a chief complaint of a minor traumatic injury within two weeks of injury, 3) discharged from the ED within 48 hours, and 4) independent in their basic activities of daily living prior to the ED visit, which was defined as a score equal or greater than 27 on the Older Americans’ Resources and Services (OARS) scaleReference McCusker, Bellavance and Cardin 12 . Minor traumatic injuries were defined on the basis of the ED physician or research personnel evaluation as anatomical lesions which do not require hospitalization. The assessment and investigation of injury and the decision to hospitalize the patient were left to the discretion of the emergency physician in charge. Patients who occasionally used a walking aid and patients requiring outpatient surgeries after ED evaluation were also included.

Participants were excluded if they 1) had significant injuries leading to any surgical or medical in-patient intervention, 2) were living in nursing homes or retirement homes with extra services, 3) were unable to consent, to attend follow-ups, or to communicate in French or English.

All patients were divided into two groups:

-

∙ Patients with MT-HI, which was defined as any trauma to the head, including scalp hematoma, facial fracture, contusion and laceration, with or without mTBI, as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO). 13 , Reference Cancelliere, Cassidy and Li 14 In addition to their head injury, they could have sustained another injury elsewhere.

-

∙ Patients without head injury, which included patients with the following isolated injuries: simple extremity fractures, contusions, lacerations, and abrasions of any body part, except the head. The types of injury are described in Table 1.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of participants (n=926)

MT-HI=minor trauma involving head injury.; ED=emergency department

Finally, patients included in the MT-HI group could have sustained other types of minor injuries (co-injury). To evaluate the effect of concomitant injury on functional decline, this group was divided into two subgroups: patients without any other injury and patients with one or several co-injuries.

Data collection

ED physicians screened all potential participants 24 hours a day and seven days a week. After a physical examination of patient injuries, physicians determined a patient’s eligibility for inclusion in the study. Trained research assistants were onsite to conduct patient interviews and data collection using standardized data collection tools. Participants underwent a baseline evaluation and a follow-up evaluation at six months post-injury. The assessment of their functional status was done either in person (20%) or by phone (80%). Perceived pain level was also measured on a verbal scale from 0 to 10. Sociodemographic and clinical data, such as age, sex, mechanism of injury, medication use, comorbidities, falls in the last three months, and social status were collected during the interview. As well, the Identification of Seniors at Risk (ISAR) score, a screening tool which has been developed to predict clinical outcomes in acute clinical settings, was performed. All injuries were coded by trained professionals using the Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS-2005), a validated diagnosis classification of injuries.Reference Joosse, de Jongh and van Delft-Schreurs 15 , Reference Lopes and Whitaker 16

The protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Review Board of the CHU de Québec and the ethics boards at each of the participating hospitals. Written or verbal consent was obtained for all participants.

Outcomes measures

The primary outcome was functional decline, which was measured by the OARS scale at baseline and six-months post-injury. This validated and reliable multidimensional functional assessment tool involves a 28-point scale that evaluates the ability to perform seven general activities (i.e., eating, grooming, dressing, transferring, walking, bathing, and continence) and seven activities of daily living (i.e., meal preparation, homemaking, shopping, using transportation, using the phone, managing medication, and managing money).Reference McCusker, Bellavance and Cardin 12 , Reference Fillenbaum and Smyer 17 Functional decline was defined as a loss of two points or more on the OARS scale, which is considered significant according to previous studies.Reference Sirois, Emond and Ouellet 9 , Reference Hebert, Bravo and Korner-Bitensky 18 This loss of two points may reflect a complete loss of one activity or a loss of one point in two different activities.

Cognitive function was measured using either the MoCA (Montreal Cognitive Assessment) or the TICS-m (modified Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status) at baseline and six months post-injury. If the research assistant was available in the ED, the MoCA was used. Otherwise, the evaluation was done by phone with the TICS-m. The MoCA is a validated 30-point tool that evaluates superior cerebral functions (i.e., executive function, naming, memory, attention, language, orientation, and abstraction) and has a Cronbach alpha of 0.83,Reference Fujiwara, Suzuki and Yasunaga 19 suggesting a high reliability. The TICS-m is also a validated and standardized test that aims to evaluate the superior cerebral functions, and has a Cronbach alpha of 0.98.Reference Beeri, Werner and Davidson 20 According to the literature, a MoCA score of <26/30 or a TICS-m result of <31/50 would indicate a mild cognitive impairment.Reference Fujiwara, Suzuki and Yasunaga 19 , Reference Knopman, Roberts and Geda 21

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as proportions and measures of central tendency, mean or median, and dispersion (standard deviation or inter-quartile range). An exploratory analysis of the socio-demographic characteristics was conducted to determine if there were significant independent predictors of functional decline. Multivariate analyses were used to estimate the relative risk of functional decline in the MT-HI group with a 95% confidence interval (CI). A log binomial model was used with adjustment for age, sex, and comorbidities.

Sensitivity analyses were done for sites as the recruitment occurred in eight different centers. Sensitivity analyses were performed to evaluate different cut-offs of the OARS scale and to evaluate the cognitive and functional decline of the mTBI population. We also compared mTBI (as defined by the WHO criteria 13 , Reference Cancelliere, Cassidy and Li 14 ) to patients with injuries other than mTBI.

With 926 patients, an alpha error of 5%, and a power of 80%, it was possible to detect an 8% difference of functional decline between the two groups. All analyses were completed using the Statistical Analysis System software (SAS Institute Cary, NC, USA, version 9.4).

RESULTS

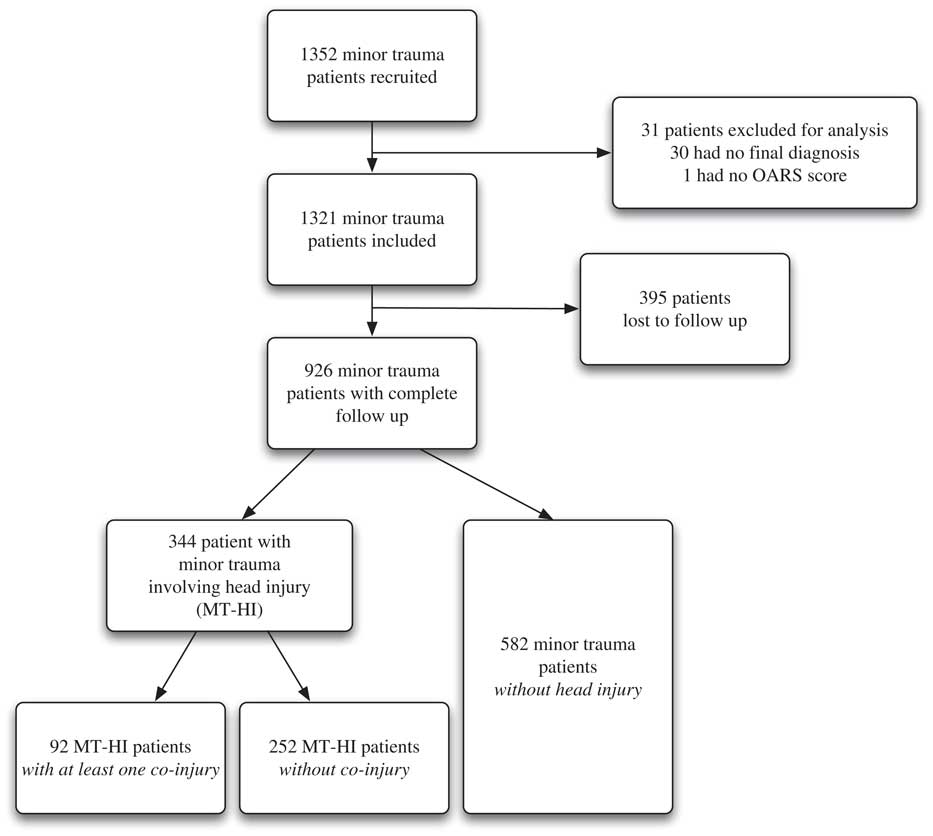

A total of 926 patients were included in the analyses, 344 in the MT-HI group and 582 in the without head injury group (Figure 1). Although 395 of the 1,321 eligible patients did not complete the six-month follow-up, patients lost to follow-up were comparable to patients included in our analyses in terms of age, sex, comorbidities, type of injury, and mechanism of injury (Appendix 1).

Figure 1 Flowchart of the study population.

Table 1 describes the characteristics of the participants and highlights some differences between the two groups. Patients with MT-HI were older than those without head injury. Also, falls from their own height was the leading cause of trauma in both groups but a greater proportion was found in the MT-HI group. A greater proportion of patients with a pain level > 7/10 was identified in the without head injury group. Two important differences were found: patients from the without head injury group needed more help after their injury and they also had a greater proportion of consultation delays (time between injury and presentation at the ED) of 48 hours and more.

Six months after trauma, 10.8% of patients in the MT-HI group had a functional decline compared to 11.9% in the without head injury group (RR=0.79 [95% CI 0.55–1.14]), which was not statistically significant (Table 2). The proportion of participants who had mild cognitive impairment was similar in the two groups both at baseline (RR=1.01 [95% CI 0.84–1.30]) and at six months post-injury (RR=0.91 [0.71–1.18]). Surprisingly, at six months, the proportion of patients who had a cognitive impairment was lower than at baseline in both groups, 21.7% v. 35%, and 22.8% v. 33% respectively (p<0.001). The presence of a co-injury did not have a significant impact on functional decline in the MT-HI group (RR=1.35 [95% CI 0.70–2.59]) (Table 3).

Table 2 Relative risk of functional and cognitive decline 6 months after injury: comparison between patients with and without head injury

MT-HI=minor trauma involving head injury; OARS=Older Americans’ Resources and Services; MoCA=Montreal Cognitive Assessment scale; TICS=Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status.*Relative risk are obtained from a log-binomial model adjusted for age, gender, and number of comorbidities.

Table 3 Relative risk of functional decline 6 months post-injury in patients with minor trauma involving head injury (MT-HI): comparison between those with one co-injury or more to those without co-injury

OARS=Older Americans’ Resources and Services.

* Relative risk are obtained from a log-binomial model adjusted for age, gender, and number of comorbidities.

We performed a subgroup analysis comparing mTBI patients, as defined by the WHO criteria, to patients with injuries other than mTBI (Table 4). The proportion of patients who had a functional decline was 11.7% in the mTBI group v. 11.4% in the group without mTBI (RR=0.90 [95% CI 0.58–1.39]). We found no significant difference in cognitive outcomes at six months between these two subgroups (20.4% v. 22.9%, RR=0.82 [95% CI 0.59–1.13]). Sensitivity analyses with different cut-offs for the OARS scale did not show different results (data not shown).

Table 4 Relative risk o0066 functional and cognitive decline 6 months post-injury: comparison between patients with and without mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI)Footnote *

OARS=Older Americans’ Resources and Services; MoCA=Montreal Cognitive Assessment scale; TICS=Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status.

* As defined by the World Health Organisation (WHO); one or more of these criteria: 1) any loss of consciousness of up to 30 minutes, 2) any loss of memory of the events immediately before or after the accident for as much as 24 hours, 3) any alteration of mental state at the time of the accident, 4) transient focal neurologic deficit, 5) post traumatic amnesia persisting for less than 24 hours, 6) a score of 13–15 on the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) 30 minutes after trauma.

** Including 1) patients with minor trauma involving head injury (MT-HI) without mTBI, and 2) minor trauma patients without any head injury.

Relative Risk are obtained from a log-binomial model adjusted for age, gender, and number of comorbidities.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first prospective study aiming to compare the functional prognosis of older adults after a MT-HI with those who sustained a minor trauma without a head injury. Our study included elderly patients from a large Canadian multicenter cohort, and standardized validated scales were used to assess outcomes. Our results showed that functional and cognitive decline was similar in both groups. So we can expect a similar prognosis regardless of the nature of the injury.

Approximately 11% of our independent older adults did suffer from a functional decline after a minor trauma. This is of concern and raises many questions. Is a minor trauma a cause or a consequence of functional decline? Probably both. We assumed that a small fracture, an abrasion, or a MT-HI would be resolved after six months, but our results showed that the functional decline was persistent in an important proportion of patients.

Our initial hypothesis was that a minor trauma involving a head injury (MT-HI) could have a more significant impact on functional outcome than a minor trauma without a head injury. However there were no differences between the two groups six months after the trauma. Surprisingly, the cognitive status at six months improved relative to baseline for all patients, which correlates with results of a previous studyReference Ouellet, Sirois and Beaulieu-Bonneau 22 on this subject. A hypothesis that could explain this finding is that the tests were done after the actual injury and their results might not represent the real baseline cognitive status of participants before the trauma. In addition, it has been shown that a short visit to the ED has repercussions on the cognitive status (recognised as delirium) of elderly patients.Reference Ouellet, Sirois and Beaulieu-Bonneau 22 - Reference Kennedy, Enander and Tadiri 26 Another hypothesis is that the presence of a potential overestimation of their function by the patients who had follow-up by phone (80%) rather than face-to-face follow-up. However, this bias would be a non-differential bias, so it would not advantage one group more than the other regarding the outcomes.

In regard to co-injuries, our results did not show a worse functional outcome among patients with a MT-HI and a co-injury, compared to a previous study by Leong et al.Reference Leong, Mazlan and Abd Rahim 11 However, the study populations were different in terms of age and injury severity.

Our study had several limitations. One limitation was the potential selection bias caused by the non-consecutive recruitment of patients. ED overcrowding and availability of the research assistants partially explains our recruitment design. Data on the missed cases due to scheduling were not available; however, no obvious selection bias occurred because patients were not recruited based on particular sociodemographic characteristics or based on specific injury type. Moreover, sensitivity analyses did not show differences between recruitment sites.

Another limitation introducing a potential selection bias was the number of participants lost to follow-up: 29% of our cohort was not reassessed on the main study outcomes at six months. This could be explained by the fact that our population was older and therefore it was more difficult for them to come back to the hospital for follow-up or to complete the entire questionnaire by phone. As previously mentioned, there were no differences in socio-demographic or clinical characteristics between the population lost to follow-up and our participants (Appendix 1). Therefore, we don’t think that a serious bias affected our results.

Although this is a large cohort, this study might not have enough power to show a statistically significant difference between the two groups for the main outcome. since the calculation of the sample size was based on a study with a higher prevalence (18%) of functional decline.Reference Sirois, Emond and Ouellet 9 However, we considered that the observed difference of functional decline between patients with or without MT-HI was not clinically important (1.1%). Finally, we were well aware that the standardized and validated tests used to measure cognitive outcomes might not be sensitive enough to detect a significant functional decline. Some authors have proposed a drop of three points instead of two as a cut-off on the OARS scale.Reference Abdulaziz, Brehaut and Taljaard 27 However, our sensitivity analyses using different cut-offs on the OARS scale did not show any difference in the results.

One of the strengths of this study was the definition we used for the MT-HI group: any trauma to the head, including scalp hematoma, facial fracture, contusion, and laceration, with or without mTBI. Indeed, the diagnosis of mTBI in older patients remains a challenge.Reference Callaway and Wolfe 5 Factors such as age-induced cerebral atrophy, and physiological response to a trauma can potentially hide typical symptoms of mTBI and undermine the reliability of the GCS.Reference Stiell, Clement and Rowe 28 These patients may not always present with the typical symptoms of mTBI but may nevertheless suffer significant consequences.Reference Bouida, Marghli and Souissi 29 , 30 An extensive review of the literature was conducted in order to find an appropriate definition of minor head trauma without brain injury. Some authors have suggested the term “minimal traumatic head injury” to define a head trauma with a GCS score of 15 without any brain injury (i.e. no altered state of consciousness).Reference Unden, Ingebrigtsen and Romner 31

Because the assessment of elderly patients presenting with head injury in the context of a minor trauma is challenging, the MT-HI definition was more inclusive than other definitions previously used for research on head trauma in older adults. Our conclusions therefore likely extend to all patients with a minor trauma involving a head injury, with or without mTBI.

Finally, emergency physicians often consider head trauma as a serious threat to functional prognosis in patients. This study reveals that minor trauma, with or without head injury, could significantly affect the functional outcome for older patients. These results can inform clinicians that the location of injury (head v. other) does not seem to affect the functional outcome. This information will help emergency physicians to correctly assess elderly patients with a minor trauma.

CONCLUSION

Older independent adults with a minor trauma involving a head injury do not seem to have worse functional or cognitive decline than those without head injury. In our MT-HI group, the presence of a concomitant injury did not seem to be associated with an increased risk of functional decline after six months. Although we observed a similar prognosis regardless of the nature of the injury, 11% of our cohort of independent older adults had a significant functional decline following their minor traumatic injury. Accordingly, further research should focus on finding a way to effectively screen for patients who are at higher risk of functional decline.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank all emergency physicians of the eight participating Canadian teaching hospitals. We would also like to thank Xavier Neveu and Brice Lionel Batomen Kuimi for their valuable assistance with statistical analysis.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/cem.2016.368