“It really isn't important whether oppression occurs in America or Russia. In both places it must be resisted and fought. As the worst oppression now is taking place in Russia, we haven't the right to do the Pilate act and say it isn't our business […].”

“After all, in the end, mountains are moved by faith. I think in order to really help those Russian politicals, we must feel first of all with them and for them, burn with the fire of indignation for their sufferings and martyrdoms, believe in them.”

Henry G. Alsberg to Roger Nash Baldwin, 9 June 1924 and 26 September 1924.Footnote 1

Introduction

Two broad general statements can be made about how the emergence of transnational political prisoner advocacy is understood within the by-now robust scholarly corpus on the history of human rights. First, this emergence played a critical, if not the critical role in the so-called great breakthrough of human rights in the 1970s; and second, both Amnesty International and localized dissident groups under authoritarian regimes arose sui generis, almost without precedent.Footnote 2 Padraic Kenney's groundbreaking recent study of political prisoners provides one of the few exceptions to the latter assumption, locating antecedents of national advocacy groups before World War I and, in some cases, back into the nineteenth century, while placing the origins of embryonic transnational organizations in the 1920s.Footnote 3 The two chief pioneers here were the Soviet-sponsored International Organization to Aid Fighters for the Revolution, better known as “International Red Aid” or by its Russian acronym, MOPR, and the US-based non-governmental International Committee for Political Prisoners (ICPP). While MOPR, an official Soviet institution, which, via the Comintern, had substantial affiliates in several Western countries, has been the subject of significant scholarly attention,Footnote 4 the more ephemeral and fragile ICPP has received only scattered mention and has not itself been the central focal point of any scholarship whatsoever.Footnote 5

The current study examines the genesis of the International Committee for Political Prisoners as the first ever fully non-governmental transnational political amnesty organization. In so doing, it establishes that the ICPP's formation occurred not primarily out of abstract notions of how political imprisonment violated universalized human rights, although in its public advocacy it developed various ways of articulating these lofty goals. The point of origin of this pioneering group may be found, rather, in a concatenation of circumstances, at the nexus of almost half-century-old Russian oppositional practices of political prisoner aid and nascent Western domestic civil liberties activism emerging during and after World War I. It was made possible by a burgeoning transnational actor network of socialists, radicals, and liberals, who, under the leadership of American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) founder Roger N. Baldwin, coalesced briefly around exposing the mistreatment of political prisoners and exiles. The specific catalyst for the creation of the ICPP was the publication and publicization of a documentary volume in 1925 entitled Letters from Russian Prisons, containing an astonishing 300-plus pages of carefully vetted, harrowing accounts of life in Soviet prisons, camps, and exile.Footnote 6 To vouch for the credibility of this extraordinary evidence, Baldwin and his collaborators, including the journalist and relief worker Henry Alsberg and the Russian-born American journalist Isaac Don Levine, also solicited “Introductory Letters by Twenty-Two Well-Known European and American Authors”, such as Albert Einstein, Sinclair Lewis, Bertrand Russell, Romain Rolland, and Thomas Mann, expressing varying degrees of consternation with the voluminous firsthand accounts of oppression and suffering.

The story of the disputatious process of this book's compilation and production, the solicitation of support from these “intellectual celebrities”, and the controversy that greeted its issuance is, improbably, also the story of the formation of the ICPP itself. It emerged at the confluence of an interlocking set of transnational political and intellectual networks of liberals and socialists, writers and scientists, journalists and labor activists, many of whom, as a rule, were reluctant to criticize the Soviet Union lest they provide ammunition to its enemies.Footnote 7 This reticence was a marked change from the frank critiques of the supposedly uniquely repressive tsarist regime by pre-revolutionary émigrés and their Western sympathizers, who, in intermittent collaborations stretching back decades, decried the barbaric cruelty of prison and Siberian exile while extolling the bravery and heroism of its victims. As discussed below, these earlier ad hoc efforts laid the groundwork for the ICPP in several ways: in the development of evanescent but generative transnational actor networks; in the appropriation of the rhetoric of humanitarian intervention on behalf of political prisoners; and in the use of personal accounts and other documentary evidence to both substantiate claims of abuse and arouse empathy.Footnote 8

Paradoxically, it was the very fact that Western liberals and socialists were far more reluctant to cast aspersions on the new Soviet order that transformed the Letters project from another effort to cast light on difficult conditions in Russia into the jumping off point for something broader and more holistic. Baldwin and his collaborators, in particular Levine, solicited endorsement from well-known and well-respected actors precisely because of the hesitancy of left-leaning intellectuals to criticize the Soviets. Alsberg persuaded Baldwin that the moral imperative of publicizing repression was at least as great when it emerged from a country with whose government one sympathized; and the latter stuck to his “right to criticize his friends”, even when Letters faced sharp criticism from Communists and their supporters.Footnote 9 At the same time, Baldwin was sensitive to the barrage of reproach over the project's apparently singling out the Soviet Union for its treatment of political prisoners. As he and his colleagues at the ACLU were determined to confine its activity to purely domestic matters, the International Committee for Political Prisoners was thus birthed as an institutional base under whose auspices it could be pre-emptively asserted that Russia was not its sole or main focus. To that end, projects were kickstarted highlighting abuses under right-wing governments, and a hastily compiled pamphlet briefly surveyed conditions in a dozen countries even before Letters was issued in late 1925.Footnote 10 Those reluctant to endorse Letters from Russian Prisons or a proposed appeal to the Soviet government might, Baldwin and his associates hoped, be willing to belong to the broader organization with its more ecumenical aims.

In discussing the interplay that led first to the Russian Prisons project and directly from this to the emergence of the Committee, this article will foreground the complexity of international liberal and leftist networks. They were comprised of several overlapping groups, including: (1) Western activists, journalists, writers, and other intellectuals; (2) Russian-born but Westernized activists who played a key interstitial role, in particular the well-known anarchists Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman; (3) recently exiled Russian émigré socialists and anarchists, who helped Berkman compile the letters; and (4) their comrades and other public figures remaining in Soviet Russia. There were unsurprisingly significant differences among and within these groups in motivations and goals for bringing public scrutiny to the conditions of Soviet political prisoners.

Berkman, and to a lesser degree Goldman, played central intermediary roles. They were close to both Baldwin, who had defended them before their deportation from America, and to Alsberg, who had traveled with them in Soviet Russia and witnessed some of the same things that led to Goldman and Berkman's great disillusionment. For them, as well as for recent Russian socialist émigrés who aided in gathering source material for Letters, the project was part of a persistent effort to expose Bolshevik repression against their comrades and, more generally, to disabuse the Western left and center-left of what they saw as a maddening susceptibility to Communist disinformation. They tried to push the ICPP, with limited success, toward more unequivocal condemnation of Soviet injustices. Those working on behalf of political prisoners on the ground in Russia, by contrast, could not both condemn the government and continue their humanitarian efforts. Thus, Ekaterina Peshkova, the head of the so-called Political Red Cross in Moscow, while welcoming the publicity and small monetary assistance offered by the ICPP, eschewed any open critique of the regime. Among the Western liberals and leftists who became involved in the project, there were diverse understandings as to how to present, contextualize, and validate the information, or even whether publishing the material was a good idea at all. These disparate reactions, discussed in detail below, reveal fundamental dilemmas of humanitarian action and the defense of rights: should efforts be aimed narrowly at ameliorating the lot of prisoners and exiles; more broadly at raising international public outrage; still more ambitiously at pushing the Soviet government toward a full amnesty for political prisoners; or, if one believed the terror inherent in the foundations of Bolshevik rule, at condemning it wholesale? Alternatively, was it either advisable or morally justified to expose Soviet misdeeds, and if so, to do so without doing the same for other states?

Even the two chief American collaborators, Baldwin and Alsberg, saw the project quite differently. For Alsberg, who had been in Russia recently, the dissonance between fellow-traveler hopes for the Soviet Union and what he had come to realize were its grim realities led him to a position not too far from his friends Berkman and Goldman. Baldwin, on the other hand, while explicitly acknowledging that it was important for those like himself who sympathized with the Soviet experiment to criticize its shortcomings, proceeded with a caution that exasperated his anarchist friends. His goal was to attract as many prominent Western liberal and leftist intellectuals to the cause as possible in order to enhance its credibility more broadly. Thus, he and Alsberg assured those prominent persons whom they approached to join and thus further legitimize the project that Letters was but the first of a broader campaign to expose the conditions of political prisoners. As noted above, given that the ACLU was designed as an organization devoted to domestic matters, the ICPP was conceived as a separate entity, with the intention that it be “international” both in its membership and in the scope of its attention. Baldwin's attempt to strike a middle ground – pushing back against those who said it was premature to criticize the Soviet experiment while refusing to condemn it openly as the anarchists and émigré socialists may have wished – then manifested in the organization's pivot to the (somewhat less comprehensive) exposes of other countries that then followed.

Prologue: Transnational Sympathy for Political Prisoners

Both the organization of aid for political prisoners and the cultivation of international concern on their behalf had a history dating back almost half a century before the advent of the International Committee for Political Prisoners. Indeed, transnational campaigns on behalf of political prisoners in particular causes célèbres go back at least to William Gladstone's campaign on behalf of southern Italian political prisoners in the 1850s.Footnote 11 More sustained efforts by Russian revolutionary émigré activists to draw European attention and sympathies to the plight of their comrades in prison and Siberian exile began several decades later; while they met with decidedly mixed success, there were several watershed moments in reaching a broader international audience. In ascertaining the preconditions for the ICPP's emergence, a brief overview of these previous efforts shows how patterns of interaction, fragile but persistent transnational networks, and rhetorical strategies had been established.

As increasing numbers of Russian revolutionary populists were arrested and exiled in the late 1870s, their émigré comrades strove to foment sympathy for them abroad. Shortly after the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in March 1881, an underground “Red Cross of the People's Will” emerged to aid prisoners and exiles, but operating domestically amidst the post-regicide repression proved extremely daunting. The venerable populist Peter Lavrov and celebrated terrorist Vera Zasulich were thus recruited to run an émigré branch, turning to the European public for support.Footnote 12 Bulletins in French-, English-, German-, and Italian-language newspapers catalogued tsarist atrocities against those who “had fought for human rights and for freedom”,Footnote 13 while begging for assistance to help alleviate “the cruel sufferings of the condemned”.Footnote 14 While the “Red Cross of the People's Will” and its successors – later known collectively as the “political red cross” – did not and could not have formal ties to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) or its official national societies, they provocatively claimed an analogous role. This assumption of a “Red Cross” humanitarian mission on behalf of political detainees represented a key component in appeals both to fellow countrymen and sympathetic foreigners while posing a multivalent challenge to the tsarist state. Not surprisingly, the official Russian Red Cross, led by members of the royal family, bitterly opposed even the most tentative proposals for the ICRC to extend its work from aiding prisoners of war to prisoners of internal conflicts.Footnote 15

It thus fell to revolutionary émigrés, in particular those well known to the Western public, like Lavrov, Zasulich, and the famed anarchist Pëtr Kropotkin, to lead the charge in soliciting sympathy and support. While monetary help was initially hard to come by, skilled propagandists like Sergei Stepniak-Kravchinsky, whose Underground Russia (1883) included vivid details of prison and exile and was translated into all the major European languages, built up a reserve of sympathy for their martyred comrades.Footnote 16 The personal relationships forged by Stepniak and others soon led to the formation of the “Society for the Friends of Russian Freedom”, first in London in the late 1880s, followed by a US affiliate. But it was the simultaneous appearance of the American explorer George Kennan's wildly popular Siberia and the Exile System (1891), highlighting the terrible conditions that those who fought “tyranny” in “Darkest Russia” faced, which galvanized Western opinion most of all.Footnote 17 A shrewd publicist, Kennan delivered dramatic public lectures to rapt audiences and helped enshrine the image of the suffering Siberian exile as a heroic martyr in the Western imagination.

Thus, transnational support for Russian political prisoners had a decades-long legacy before 1917, and monetary support was accompanied by efforts to pressure the tsarist state. It is noteworthy that some of those involved would carry their experience into the post-revolutionary period. When the recently released venerable populist Catherine Breshkovskaia played the role of traveling revolutionary celebrity in America during the revolution of 1905, a young Emma Goldman introduced “Babushka” to Jane Addams (whose endorsement Baldwin also sought twenty years later) and other progressive activists.Footnote 18 By the final decade of tsarist rule, the network linking internal aid groups with: (1) comrades temporarily abroad; (2) assimilated immigrants and the children of émigrés; and (3) Western sympathizers was complex and vigorous. In England, the widely admired Kropotkin's wife Sofia helped lead the robust “Committee for the Relief of Russian Exiles in Northern Russia and Siberia”, a joint effort of émigrés and prominent British political figures, including several MPs. Here also, Russian-born but assimilated intermediaries played a key role, in particular the Anglican pastor's wife Sonia Howe.Footnote 19 Kropotkin's account of tsarist oppression, The Terror in Russia: An Appeal to the British Nation, issued by the self-styled “Parliamentary Russian Committee” went through six editions in two months.Footnote 20 Sonia Howe and other activists now confidently addressed parliament and openly lobbied for full amnesty for Russian political prisoners.

It was the “People's Will” veteran leader Vera Figner who would come to lead the most significant prerevolutionary transnational political prisoner advocacy effort. Venerated in the West for her several decades of suffering in the notorious Shlisellburg fortress prison, Figner went abroad shortly after her release in the mid-1900s. While in England giving well-attended lectures on prison conditions,Footnote 21 she was deeply impressed with Sofia Kropotkin's aid efforts and, on returning to Paris, founded the Committee to Aid Penal Laborers [katorzhniki].Footnote 22 A central element of this burgeoning prewar advocacy was collecting and publicizing the documentary evidence of cruelty and suffering: in addition to Kropotkin's Terror in Russia, Figner gave a series of public lectures to rapt audiences, out of which was published Les Prisons russes, which went through multiple editions in at least five languages.Footnote 23 At some of her appearances, she was introduced by Francis de Pressensé, the president of the French Ligue des droits de l'homme Footnote 24 and an active member of the Société des amis du peuple russe, a French analogue to the “Friends of Russian Freedom” formed in 1905. Pressensé not only actively supported her prisoner aid efforts, but one of his own talks was also published in multiple languages as Atrocities in Russian Prisons.Footnote 25 Along with Kropotkin's Terror, these formed a surfeit of evidence, supplemented by the even more substantial Tortures of Political Prisoners in Russia (1913), issued by the Krakow Union of Help to Political Prisoners in Russia, second in scope only to Figner's in what was now an extended network of groups in Europe and North America.Footnote 26

On the eve of the Great War, these voices raised against tsarist oppression coalesced into transnational action and organization, most notably in the form of several mass petitions to the Russian government, a tactic that the ICPP would revive a decade later. The prominent salon hostess Aline Ménard-Dorian, like Pressensé a leading figure in both the Ligue des droits de l'homme and the Société des amis du peuple russe, drafted a petition to the tsarist regime in 1911 that garnered over 200 signatures. To galvanize support for the suffering political prisoners and exiles in Russia, Ménard-Dorian evoked earlier humanitarian interventionist causes back to Gladstone, and she proposed an international federation of societies of Friends of the Russian People.Footnote 27 Though this did not materialize, interest in the cause continued to spread. In 1913, the Social Democrat Karl Liebknecht, German translator of Kropotkin's Terror in Russia, organized another appeal that soon had 500 signatories, several of whom – Gerhardt Hauptmann, H.G. Wells, Romain Rolland, Bertrand Russell – would write “Introductory Letters” for Letters from Russian Prisons a decade later. Drawing a line from Kennan's Siberian Exile to Kropotkin's Terror to the recent publications of the Ligue, Liebknecht argued that the time had come for “all friends of justice and humanity” to denounce the dreadful conditions.Footnote 28 From this emerged the brief-lived Deutsche Hilfsverein für die politischen Gefangenen und Verbannten Russlands,Footnote 29 while an additional international gathering in Amsterdam in late 1913 directed donations to Figner's Committee.Footnote 30

The outset of hostilities the following year shattered pan-European calls in the name of a common humanity, and the twin traditions of collective appeal and atrocity propaganda in the name of suffering humanity were both repurposed for national goals during the war. The activities of the well-established network of Russian émigré and domestic political prisoner aid communities nevertheless continued uninterrupted and robustly through the war. While none of the specific transnational efforts survived into the postwar and post-revolutionary period, a robust set of practices based on the novel notion that political detainees in one country ought to be the subject of concern for another nation's citizens had developed and were available for further adaptation. But how could this be done when the offending government was one not generally roundly condemned, but rather the subject of much interest and even sympathy on the part of the liberal and radical intellectual international community? It was one thing to mobilize and sign petitions chiding the tsarist autocracy, concerning whose reactionary, oppressive nature there was little disagreement among Western intellectuals. It was quite a different thing, after the October Revolution in 1917 – even among those who were not entirely blind to the shortcomings of the new order – to be willing to lend one's name and moral support when the subject of reproach was the world's only socialist state.Footnote 31

Political Prisoners under the Dictatorship of the Proletariat

After the October Revolution, political prisoner aid did not immediately resume internationally. Within Soviet Russia, the “Political Red Cross” was reconstituted in Moscow in early 1918, and for the next four years operated as a legal voluntary organization, albeit one already under significant constraints. Among its initial members were figures well-experienced in the tsarist-era political aid groups, including leading figures in the moderate socialist parties: the Marxist Mensheviks (Social Democrats) and the populist Socialist Revolutionaries (known as the SRs). For the first several years, the prominent political defense attorney Nikolai Muraviev served as chair; his deputy, Ekaterina Peshkova, would go on to lead it from 1922 until it was finally shut down in 1938. The venerable Figner served as honorary chairwoman and was initially actively involved. During these first several years, the organization not only sought to improve the conditions of political prisoners and exiles, but also openly criticized the government on certain matters. For this, among other reasons, this initial incarnation of the Political Red Cross was liquidated in mid-1922 and allowed to reopen in December in a very different form, as a personalized lobbying effort officially called “E.P. Peshkova: Aid to Political Prisoners”, although it continued to be informally known by its old name.Footnote 32 As discussed below, Peshkova, now operating with her close associate Mikhail Vinaver and a small staff, well understood that their aid efforts now depended on avoiding any hint of politicization.

During the chaotic years of the Russian Civil War, from 1918 to early 1921, there would have been little opportunity for international humanitarian intervention of the sort that had emerged in the prewar period. One notable exception to this, albeit a relatively brief one, was the tentative efforts of the International Committee of the Red Cross to expand its now vast work in repatriating prisoners of war to also include civil wars and revolutionary situations. But just as the tsarist government had rejected any notion of ICRC intervention into domestic affairs a decade earlier, this affirmation ran into the firm resistance of the Soviet government. While ICRC representatives in Moscow achieved some limited early results lobbying for improved access and establishing contact with Peshkova, the strong resistance of the Soviet government ultimately cut these efforts short.Footnote 33 Ultimately, the international Red Cross movement's commitment to “neutrality” made it ill-suited for political prisoner advocacy.

As repressive measures against moderate socialists continued after the end of the Civil War, some of those who had been active in the Moscow Political Red Cross fled into the substantial emigration in Western and Central Europe, where they re-established foreign-based branches that could operate more openly than at home. The largest branches operated in Paris, Berlin, and Prague, including leading Mensheviks, SRs, “nonparty socialists”, and even some center-left liberals. More than a few of those involved had direct ties with Peshkova, which made possible the direct exchange of information and aid from and to Soviet Russia.Footnote 34 Divisions within the fractious leftist émigré community complicated the organization and provision of aid and also, as we shall see, hindered cooperation in supplying material for the ICPP. The more radical groups, including the anarchists and the “Left SRs”, who had splintered from the main party in 1917, distrusted the moderates and preferred to rely on their own aid organizations.Footnote 35

When Goldman and Berkman left Soviet Russia in late 1921, deeply disenchanted and horrified at the treatment of their comrades,Footnote 36 Berkman immediately took the lead in establishing standing anarchist aid efforts abroad. Unlike some of his comrades, he was willing to look beyond factional divisions and helped form a “Joint Committee for the Defense of Revolutionists Imprisoned in Russia”, linking the efforts of anarchists and Left SRs for the next several years.Footnote 37 Via this Joint Committee, he served as the primary liaison with Baldwin and Alsberg to provide much of the material for Letters from Russian Prisons, as discussed below. Moreover, despite greater ideological differences, Berkman also coordinated with the more moderate Mensheviks and SRs in the Berlin and Paris “Political Red Cross” affiliates for this. Together with the simultaneous efforts of Isaac Don Levine, a remarkable abundance of documentary evidence on the conditions of Soviet political prisoners was gathered. The question was how to engage a Western intellectual audience far less inclined to outrage against the young socialist government than they had been against the “tyrannical” old regime.

Raising the Alarm in the West

Russian émigré activists, including Russian-Americans like Berkman and Goldman, recognized early on that it fell to them to draw the attention of Western publics to the fate of socialist political prisoners in the USSR. While there were pockets where they did find an audience – such as within the leadership of the Labour and Socialist International (LSI), where Mensheviks exerted influenceFootnote 38 – as a whole, they experienced a significant reluctance among the broader liberal and radical publics to criticize the Soviet state.Footnote 39 While there were distinct moments like the 1922 SR show trial that drew international approbation,Footnote 40 on the whole, rallying support abroad remained challenging. In their repeated efforts to bring the attention of a broad transnational audience to the suffering of their imprisoned and exiled comrades, socialists and anarchists deployed the rhetoric of humanitarian emergency familiar from pre-revolutionary appeals. As one 1923 entreaty from the Berlin “Political Red Cross” committee declaimed:

There are neither colors nor words with which to portray the incredibly grave situation of political prisoners and exiles in Soviet Russia. Consigned to be victims of epidemics, hunger, and cold, forced to insist on their human dignity by means of murderously exhausting hunger strikes – political prisoners wait long months and years in prisons without charge or a formal trial […] in strict isolation, under a prison regimen persevered inviolate from the old regime.Footnote 41

While these appeals found direct resonance within the large Russian émigré community, reaching Western audiences turned out to be an extraordinarily difficult task.

Even seeming allies were often reluctant to openly criticize the Soviets. When, in December 1923, six socialist prisoners were killed during protests at the notorious Solovki Island prison camp in the far north, the Menshevik leaders Rafael Abramovich and Fëdor Dan insistently lobbied leading figures within the LSI and the British Labour Party to speak up. Leaders of the latter were an especially tough nut to crack, determined to avoid any criticism of the Soviet Union, while even Friedrich Adler and other LSI allies took some convincing that things were, indeed, as bad as they seemed at Solovki.Footnote 42 To Abramovich and Dan's relief, an appeal to both Western public opinion and the Soviet government was at last issued in fall 1924 by German social democrats, liberals, and other radicals, some of them veterans of the Liebknecht petition a decade earlier.Footnote 43

Already at a structural disadvantage, the émigré socialist and anarchist appeals unsurprisingly faced relentless Communist counterpropaganda. The slowness of Western socialists to speak up on Solovki had resulted, in significant part, from their credulity to Soviet claims that the prisoners there were treated well and even generously. In addition, MOPR, formed at the end of 1922 to take back control of the international moral narrative on political prisoners, and International Red Aid national affiliates, were established under the Comintern's aegis to focus on the plight of “class war” prisoners in capitalist states.Footnote 44 Vastly outgunned and all too acutely aware of the foreign left's predisposition to give credence to official Soviet sources, émigré activists continued to insist that the Western public know the singularity of their comrades’ plight. “There is a general belief that [Soviet] persecutions are of the same nature as those to which communists are subject now and again in Western European countries”, Abramovich argued in Bolshevik Terror against Socialists, a compendium issued under the LSI's auspices. “This, however, is altogether wrong. The terror system in Russia has no parallel in any other land. Nothing similar has been known in the history of Western Europe, not even in prerevolutionary Russia.”Footnote 45 The claim that Soviet oppression was worse even than that of the reviled tsarist regime was an intentional provocation, one already becoming a staple of the genre.

Garnering broader foreign attention, however, required the involvement of several American left-liberals, who had become concerned that their general sympathies for the socialist experiment not lead them to ignore its faults. The most important of these figures was the self-described “philosophical anarchist” Henry Alsberg, who later led Roosevelt's Federal Writers’ Project. He became the central Western catalyst of the efforts that led to Letters, and, arguably, thus deserves credit for the formation of the ICPP itself.Footnote 46 A legally trained journalist, then active in the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC), Alsberg had befriended Goldman and Berkman during a six-week journey through Russia in 1920, during which he, like they, became disillusioned with what he saw. He was in Petrograd during the March 1921 Kronstadt uprising and, in 1922, spent eight months helping direct the JDC's famine relief efforts in Russia.Footnote 47 Although it was not his primary concern initially, the lot of socialist and anarchist prisoners came to haunt him to the point of obsession. “I have been very much swallowed up by this business of the ‘Russian Politicals’”, Alsberg wrote a JDC colleague. “I wish I were a rich man so that I could devote all my time in straightening this one little thing out in the right way.”Footnote 48

Convinced that something must be done and looking for well-placed allies, he turned, in summer 1923, to Bertrand Russell, whom he had also met in Russia, and who had also expressed disappointment with Soviet rule. Noting he had “seen misery beyond belief” in the prisons there, Alsberg asked for help circulating an appeal to Soviet authorities among prominent European intellectuals like Anatole France, Romain Rolland, Georg Brandes, and Gerhardt Hauptmann (several of whom, like Russell, had signed Liebknecht's petition a decade earlier).Footnote 49 “I should be most happy to do anything possible for the prisoners in Russia”, Russell replied, but thought it more useful if he lobbied British Labour Party officials.Footnote 50 When the persistent Alsberg sent a lengthy list of socialist and anarchists imprisoned by the Soviets, however, proposing they form an “international committee” to coordinate, Russell himself took on the task of editing Alsberg's appeal demanding amnesty for all political prisoners.Footnote 51 “The Soviet Government has now been in power for six years, and appears to be the most stable in Europe”, the revised appeal remarked. “Nevertheless it still finds it necessary to impose prison and exile upon large numbers of its political opponents, solely on account of their political opinions.”Footnote 52 Berkman's comrade Alexander Schapiro was tasked with securing signatures in France; but having “started on my pilgrimage” to the famous figures, he found more expressions of sympathy and solidarity than actual autographs. “To approach these ‘great men’ is a tough job!” he grumbled to Alsberg, due to the pervasive trepidation with criticizing the Soviets.Footnote 53

Here, of course, is ready evidence of how dramatically matters had changed since hundreds of esteemed scholars, writers, and political figures had been willing to sign the petitions regarding tsarist repression a decade earlier. While we know little of what they told Schapiro directly, the snippets he reported back to Alsberg are revealing. Two of those he spoke with, the pacifist poet Georges Pioch and his close friend, the esteemed Dreyfusard, feminist writer, and pacifist Séverine (Caroline Remy), had both recently left the French Communist Party after the Comintern had demanded that they choose between it and the Ligue des Droits de l'homme, in which both were active.Footnote 54 In Pioch, whose help he sought in obtaining the signature of Anatole France, he found a willing partner. While France had joined other European intellectuals rallied by Gorky to protest the SR show trial a year earlier, Pioch, who was very close with the venerable writer, was not optimistic in getting him to sign the petition. This, he explained to Schapiro was due to “the great sensitiveness of A.F. towards Soviet Russia, as he still considers that the Russian Revolution and the Russian bolshevists are synonymous”. The reaction of Madame Séverine was still more directly frustrating. “She was deeply interested and touched”, Schapiro told Alsberg, “but […] she was afraid that anything she might say would harm the Russian Revolution. She too considers any opposition to Soviet Russia, even on humanitarian grounds, as playing in the hands of the bourgeoisie”. On the other hand, while loathe to sign a petition, Séverine was not entirely unsympathetic and proposed to Schapiro that he and his colleagues consider publishing the annotated list of political prisoners he had shown her in pamphlet form. Thus, we can see a space emerging, even amidst the great reluctance of those approached to sign a petition against the Soviet government, for receptivity to the publication of documentary evidence.Footnote 55

Schapiro also turned to the Ligue's President, Ferdinand Buisson, who was receptive to the extent that he promised that the Ligue would consider putting out its own, separate statement concerning Soviet political prisoners.Footnote 56 In addition, Buisson indicated that he would seek a resolution “on the question of persecutions” from the newly formed International Federation of the Leagues of Rights of Man (FIDH), whose secretary general was Vera Figner's ally from the previous decade, Aline Ménard-Dorian.Footnote 57 Indeed, Nicholas Avksent'ev and Boris Mirkin-Getsevich, leaders of the International Federation's Russian émigré affiliate, which had close associational links to the émigré “Political Red Cross” branches, consistently brought attention to the Solovki incident and other abuses of Soviet political prisoners. The French Ligue did put forth its own appeals to Soviet leadership: first in spring 1924 on Solovki, then another, a year later, in more general terms, followed by a resolution of the FIDH “protesting against the regime of terror” in Soviet Russia.Footnote 58

In the meantime, needing more allies and perhaps a different approach, Alsberg turned to his own side of the Atlantic, specifically to Roger Baldwin, who had experience in this area dating back to his work with the ACLU's wartime predecessor, the National Civil Liberties Bureau, defending the rights of draft resistors. In 1918, he also joined the League for Amnesty for Political Prisoners; Goldman was not only among this group's founders, but also, on her and Berkman's arrest just after its formation, among the initial subjects of its efforts.Footnote 59 The ACLU itself emerged after the notorious 1919 Palmer Raids, during which Goldman, Berkman, and other foreign-born radicals were rounded up for deportation; in the years following, amnesty for political prisoners remained one of its signature causes.Footnote 60 It was thus with the hope that the ACLU might take up the gauntlet that Alsberg forwarded the appeal and documents on Soviet political prisoners to Baldwin in February 1924. Sorry that “the whole affair has hung in the doldrums”, and evermore convinced of the moral imperative of collective action, Alsberg again proposed “the formation of an international committee, which should in a spirit of conciliation approach the Soviet government on behalf of these prisoners”.Footnote 61 When he did not hear back for a month, he all but accused Baldwin and the ACLU of cowardice.

There are very few people that can muster up the nerve to tell their own gang that they are wrong and narrow and prejudiced. Christ being crucified by the Romans was one thing, but Christ being crucified by his own disciples would have been quite another. […] Meanwhile, unfortunately, the best souls and brains of Russia are being exterminated in Russian prison camps and jails, or in Siberian exile.Footnote 62

But Baldwin was already hard at work, rustling up American intellectuals like Upton Sinclair, ACLU co-founder Rev. John Haynes Holmes, and others to sign the appeal. He encountered the same prevailing reluctance that Alexander Schapiro had in Europe, and even the few signatures Baldwin did secure required promising further revising the appeal. The journalist Norman Hapgood expressed a not uncommon sentiment, explaining that while “the form of the protest is excellent, and I think that it is a good thing to send”, he presumed he personally could have more influence with the Soviets by abstaining from signing. The demurral of Hapgood, a distinguished establishment liberal who had been editor of Collier's and Harper's, and had briefly served as Woodrow Wilson's ambassador to Denmark in 1919, is indicative of the challenges faced, since he was, as he reminded Baldwin, “continually jeering at their excesses in my public writings”. It was, he suggested, partly because of this fact that he was leery of joining in on the petition.Footnote 63

Baldwin proposed sending the petition to Russia with current ACLU chair Rev. Harry F. Ward, who could survey the conditions of prisoners firsthand.Footnote 64 Alsberg worried that the non-Russian speaking Ward would be an easy mark; the Bolsheviks would “bamboozle him, show him a few nice cells in a few nice jails, etc.”.Footnote 65 While he was able to convince Baldwin to hold off on submitting the petition until they had added European signatories in addition to the American names they had secured, Baldwin trusted Ward and saw his trip as part of authenticating the documentary material. Alsberg reluctantly came to see the value of this process of verification, which would also include acquiring affidavits for certain documents. “It is very difficult”, he told Baldwin, “for one, like myself, who has spoken with the politicals who have suffered and who has been in the Soviet jails to inspect them […] to think that the facts require much proving. But your letter convinces me that they do”.Footnote 66 In fact, it was precisely via the authentication process that the project expanded from supporting the petition to compiling an extensive volume for publication, and even of establishing an organizational base for this work.

The anarchists were still more frustrated. Goldman was furious with Baldwin, and the deeply insulted Berkman declared it a “first-class joke” that Ward, who did not speak the language and knew nothing of the country, was trusted more than long-standing revolutionists.Footnote 67 It took some effort by Alsberg to prevail upon him that, to see the project to completion, they needed to not only secure affidavits for the documents, but also procure official Soviet laws and regulations for balance.Footnote 68 A complex chain of recrimination and doubt thus unfolded, based on the degree to which those involved believed that helping political prisoners required either criticizing or not criticizing the Soviet state. Previously, Alsberg had been annoyed with Baldwin for his hesitation and seeming lack of fortitude; now, Goldman and Berkman became irritated with their American friends – not only Baldwin, but also Alsberg, for what they saw as faintheartedness. Soon, as detailed below, it would be Baldwin responding defensively (but also defiantly) to those who questioned the entire affair of even mildly critiquing Soviet rule.

In the meantime, Ward's trip report confirmed Alsberg's suspicions that he would be too easily swayed by official propaganda and too overconfident in his own limited observations. The two men had very different takes on what Peshkova had relayed to each of them about her group's efforts.Footnote 69 Alsberg griped that, in proposing they simply help fund her, Ward showed a disturbing naiveté at her delicate position. Acutely aware that her modest, personalized office was allowed to operate only insofar as it said almost nothing publicly about its activities, she had let Alsberg know that they avoided appealing for foreign funds for fear of being shut down again.Footnote 70 Ward, however, was savvier than Alsberg credited, noting to Baldwin that Peshkova had encouraged the ICPP's activities. “Her opinion on foreign protests”, Ward wrote, “is that superficially and temporarily it hurts their cause but finally helps it”, based on her observation that international protest of the 1922 SR show trial had initially exacerbated but then ameliorated the defendants’ sentencing. Ward added that she approved their draft petition to the Soviet authorities but had cautioned him that, to be most effective, their efforts should focus narrowly on appealing for amnesty, “rather than public attack”.Footnote 71

With Peshkova's latter point Baldwin was very much in accord. He had already experienced pushback to the draft petition, which Soviet leaders had obtained through backchannels,Footnote 72 and wished not to exacerbate the challenges he correctly foresaw ahead. His anarchist friends were irate: Goldman forcefully insisted that the abuse of political prisoners was a core feature of Bolshevik rule, not some minor flaw.Footnote 73 This obstinately principled stance, however, complicated Goldman's efforts to form an ICPP analogue in Britain, as did her exclusive focus on Russia. The esteem English liberals and radicals had for her did not mitigate the discomfort they felt on hearing her strident denunciations of Soviet tyranny at a series of dinners and lectures. “When she rose to speak,” Russell recalled of one fall 1924 gathering, “she was welcomed enthusiastically; but when she sat down there was dead silence. This was because almost the whole of her speech was against the Bolsheviks”.Footnote 74 The writer Rebecca West was one of the few local acquaintances to stand with her steadfastly, while others she had looked to as allies, such as H.G. Wells and the Labour Party leader and economist Harold Laski, distanced themselves from her efforts.Footnote 75 Even Russell, while still “prepared to sign definite letters of protest to the Soviet government” (evidenced in his not only writing a blurb for Letters, but also inducing the hesitant Wells to do so), demurred from joining Goldman's “movement”, as he was “not prepared to advocate any alternative government in Russia”.Footnote 76 Her short-lived “British Committee for the Defence of Political Prisoners in Russia” thus failed to gain traction and proved a grave disappointment. While it arranged her lecture tour, demanded amnesty for Soviet political prisoners, and issued Goldman's rebuke of a British Trade Union delegation report for whitewashing Soviet repression, the Committee's fundraising efforts were miniscule, and it attracted few if any newcomers to the cause.Footnote 77

Even Baldwin's cautious approach did not forestall attacks by Soviet allies, and when Workers’ Party hecklers came out in force to a boisterous March 1925 Town Hall meeting, he proved less “weak-kneed” than Goldman presumed. While ICPP co-founder B. Charney Vladeck, who had spent time in tsarist prisons as a Bundist and now managed the New York Daily Forward, was prevented from speaking entirely, Baldwin managed to persevere through multiple interruptions. “I decline to accept the communist notion that you must be 100% with the Soviet government or 100% against it”, he defiantly declared. “I reserve the right to criticize my friends just as I do my opponents.” He rejected the notion that “persecuting opponents merely for their opinions” was justified even under the dictatorship of the proletariat; in any case, “the excuse for it in Russia has long since passed”.Footnote 78 Undeterred, Communist activists continued to disrupt the campaign, targeting a concurrent North American lecture tour by the Menshevik Abramovich, who had assisted Berkman with obtaining materials and affidavits, and who now strove to raise awareness and funds for political prisoners in conjunction with the ICPP.Footnote 79 Baldwin, who wished to build bridges to the Soviet-run MOPR for planned efforts elsewhere, was dismayed at the extent to which its affiliates joined in the hostility. As he dejectedly noted, International Red Aid “refuses official cooperation with any group that recognizes political prisoners in Soviet Russia”.Footnote 80 While this remained their public stance, however, they were later willing to collaborate surreptitiously to aid imprisoned Communists in other countries.Footnote 81

The sharp divisions among American radicals and liberals on the propriety of exposing Bolshevik transgressions also spilled out into the open in the pages of The Nation, whose editors were among those Baldwin recruited to the ICPP, even with its relatively sympathetic coverage of the USSR. In early March, it published brief excerpts from the Committee's materials on the Solovki camp, juxtaposing damning accounts by socialist and anarchist prisoners with an official Soviet report providing a diametrically opposed version of events. Also printed were part of Ward's restrained report, which did allow that “friends” of the Soviet state “may properly urge […] that the time has come to grant a general amnesty to political offenders”, followed by an inflammatory apologia by The Nation's then openly pro-Soviet Moscow correspondent, Louis Fischer.Footnote 82 This satisfied no one. Wrathful rebuttals to Fischer by Alsberg, Berkman, Vladeck, and others came in the following weeks, while Communist sympathizers chided the editors for giving the matter any credence at all.Footnote 83 For the ICPP, this controversy was not all bad, Alsberg assured Goldman, since it had helped amplify press coverage: “It made a terrific stir.”Footnote 84

Letters from Russian Prisons: Preparation and Publication

In the meantime, Berkman and his comrades doggedly gathered, translated, and authenticated the documents despite their great irritation with Baldwin's “cold-blooded” insistence on further “proof”.Footnote 85 Having experienced the challenges of promoting the Joint Committee, Berkman understood well the potential value of the platform that Baldwin and his associates offered. “The American liberal's psychology,” he explained to the Mensheviks and SRs in seeking their help with the distasteful task, “requires proof of a ‘legal value’, such as affidavits and certified documents of similar nature in order to become convinced”.Footnote 86 He entreated his anarchist comrades to overcome their aversion with all official processes: these were the same kind of people who had helped “Babushka” (i.e. Breshkovskaia), and they could be of enormous help again.Footnote 87 His strong sense of the historical connection to previous moments when foreign sympathy had crescendoed led Berkman, with uncharacteristic optimism, to invoke repeatedly the possibility that the book might be a “bombshell” as impactful as George Kennan's famous exposé of “Darkest Russia” decades earlier.Footnote 88 The materials they ended up sending to Alsberg in New York in February 1925 vastly outstripped what was originally anticipated.

The burgeoning collection of authenticated documents was supplemented with items compiled by Isaac Don Levine, another Russian-Jewish born American journalist, after his boasts of having independently lined up English, French, and German publishers for a volume called “Letters from Bolshevist Prison and Exile” proved untrue.Footnote 89 While Berkman and Alsberg viewed Levine as a bombastic self-promoter, Goldman admired his energetic “American news paper [sic] knack, he knows how to get results and boost things”.Footnote 90 This skill turned out to be of great use, as it was Levine who had taken upon himself the task of re-approaching celebrated writers and intellectuals, this time to solicit responses that could serve to endorse the book.Footnote 91 Here again, one sees the shifting nature of the project: the original protest petition to the Soviets, initially intended for prominent European signatures, had become an American affair; so, too, for the most part with the membership of the “International Committee” itself. In soliciting the blurbs, however, Levine reached out to a wide array of European eminences, and the remarks from those who responded helped give Letters from Russian Prisons a more international resonance.

The question of how to present the volume served further to develop the ICPP's broader outreach. If Goldman had hoped the “scandal” of the Town Hall meeting would lead Baldwin to see the futility of moderation in the face of Communist zealotry,Footnote 92 it in fact furthered his resolve to portray the Russia book as merely one step in a comprehensive worldwide campaign. While Alsberg spent the summer editing and preparing the volume, Baldwin insisted that the Committee first issue a more general overview to set the table. In less than fifty pages, this hastily compiled set of reprints from the Nation and elsewhere surveyed Political Persecution Today in a dozen countries, from Italy, Germany, and Poland to India, Japan, and Venezuela. Russia, very intentionally placed last, was covered by excerpts of Ward's report. Baldwin introduced the ICPP's program, which, in addition to gathering facts for publication, would help disseminate “relief in the form of money, books, periodicals, food and clothing”. Readers were informed that channels were already available to direct donations to eight of the twelve countries covered in the pamphlet.Footnote 93

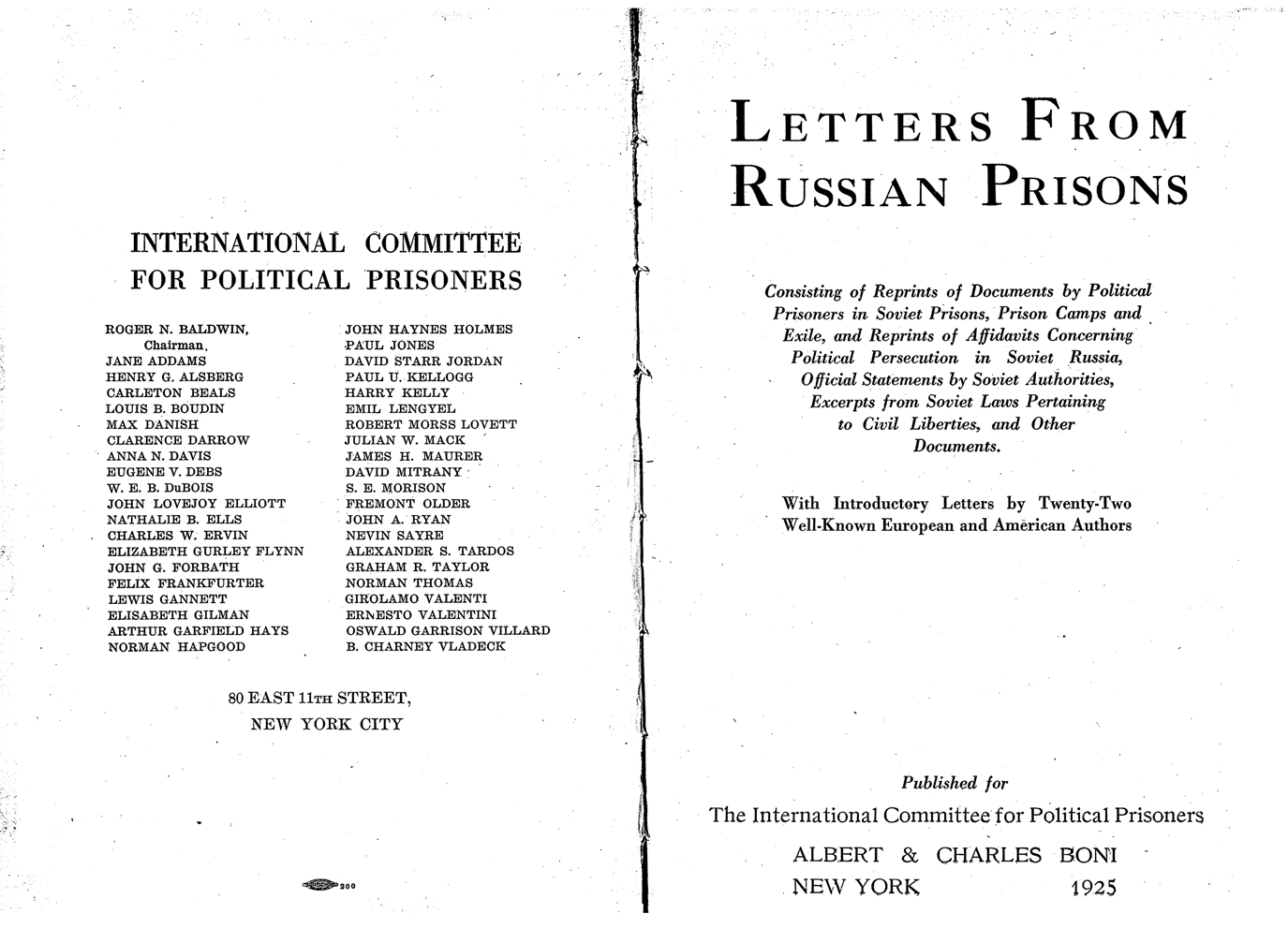

The contrast of this thin overview with Letters from Russian Prisons, when it at last appeared several months later, was stark. Letters had ballooned into a substantial tome of over 300 pages of primary sources, primarily firsthand testimony from current or former prisoners, with a note in the table of contents that more than ninety other documents had been omitted due to lack of space. It was handsomely published by Albert & Charles Boni in New York, with an identical British edition issued by C.W. Daniel several months later; there were several dozen illustrations scattered throughout, primarily facsimiles of the documents and pictures of prisoners and exiles. Baldwin had directed Alberg to convey the impression that this was documentary evidence dispassionately presented, initially proposing that it be entitled simply “Political Prisoners in Russia”.Footnote 94 While the actual title represents a compromise between this and Levine's, it was agreed not to identify the editors; it was felt Berkman's known anti-Bolshevism would skew reaction, and even Alsberg's name was avoided. Instead, Baldwin wanted to give the sense that the book was being collectively presented by the International Committee for Political Prisoners, and so a list of current members, totaling forty names, was printed on the left-hand facing title page (Figure 1). This, as will be discussed below, caused consternation among some of those whose names appeared, who feared that it implied their endorsement.

Figure 1. Title page of Letters from Russian Prisons. The verso page lists the members of the ICPP.

Of the book's main collaborators, this list of committee members represented the only appearance of Alsberg's name in the volume, while Berkman showed up only as the co-author of a single document toward the end of the volume: an appeal he, Goldman, and their comrades had made to Lenin back in 1921 protesting oppression of Anarchists.Footnote 95 Baldwin, on the other hand, was identified as authoring the introduction, albeit “for the committee”. This undersold the extent to which it was a subject of some debate and controversy among ICPP members when circulated shortly before the book's publication, despite Baldwin's usual efforts to provide balanced remarks and to stress the rigor with which the documents had been authenticated. On the one hand, he echoed the remarks he had made at the Town Hall in March, asserting that Soviet justifications for political persecution rang hollow and worrying that the “period of transition as defined by the Bolsheviks may last fifty years, and that it may continue indefinitely to be used as the excuse for political tyranny”. On the other hand, he tried to soften the matter by acknowledging that “many of the members of the Committee as individuals regard the Russian Revolution as the greatest and most daring experiment yet to recreate society”.Footnote 96

The brief “introductory letters from celebrated intellectuals” – not to be confused with the much more voluminous letters from actual prisoners that comprised the bulk of the volume – followed Baldwin's introduction. Somewhat surprisingly, given the desire to avoid associating the book with anyone who could be accused of anti-Soviet bias, these letters were printed exactly as written, even as many identified Isaac Don Levine as addressee. A footnote about this compounded the matter by explaining that Levine had “aided in collecting the material”, a fact seized upon by Soviet allies in their initial ripostes to the volume.Footnote 97 While the ICPP members were overwhelmingly Americans, most of the twenty-two introductory letters were from Europeans. Levine had succeeded in cajoling even some of those Brits uneasy with Goldman, such as Wells, H. N Brailsford, and Harold Laski, along with an impressive list of eminences like Russell, Albert Einstein, Thomas Mann, and Karl Capek. The letters written by Rebecca West, Georg Brandes, Sinclair Lewis, and the Danish novelist Karin Michaelis (a friend of Goldman and Berkman's) express shock at the prisoners’ firsthand accounts and endorse the exposure of Soviet repression. But even letters voicing less than full-throated support, such as Upton Sinclair's reluctant response, were printed as is. Most peculiar was the inclusion of the famous leftist writer Romain Rolland's reply, clearly not intended for publication. While recognizing that the persecution documented was disturbing, he told Levine that, “I will not write the introduction which you ask of me. It would become a weapon against one party in the hands of other parties who are neither better nor worse.”Footnote 98

The mass of documentary material that followed had been divided by Alsberg into six sections: (1) Exile; (2) Stories from Prison; (3) The Northern Camps; (4) Documents Concerning Civil Liberties and Administration of Justice and Prisons; (5) Questionnaires; and (6) Excerpts from Laws and Regulations. While Baldwin had wanted to put the official regulations first, Alsberg protested, arguing that the laws were mostly “very involved and stupid” and that “the reader will get terribly weary and get a wrong idea of the book”.Footnote 99 Each of the sections begins with an explanatory note, almost certainly written by Alsberg, while some of the documents are annotated as well.Footnote 100 It is no wonder that the sheer weight of the relentless descriptions of the horrid conditions and desperate struggles that anarchist and socialist prisoners faced made a profound impression on readers, nor that the Communist response was deeply hostile. If Baldwin wished to avoid implicating the Soviet system, not only does the story that the documents collectively tell work against this, but, unsurprisingly, many of the prison letters are unambiguously condemnatory. “Russia of today is a great prison”, declared the anarchist Mollie Steimer, and its “prisons and concentration camps […] are filled with revolutionaries who do not agree with the tyrannical regime enforced by the Bolsheviks”. The Soviet penal regime for political prisoners, added a group of socialist workers, enforced measures that, “surpass, by their Asiatic cruelty and refined tyranny, all that had to be gone through by a Russian revolutionist in the vilest Czarist prison”.Footnote 101 The imprisoned SR leader Abram Gots, in lambasting a Dutch trade-unionist who downplayed Soviet prison conditions, spoke directly to Western fellow travelers: “Your name and your person,” he raged, “are used to cover up the worst kind of violence and despotism”. Why, he wondered, “did you […] put on so willingly the uniform of a Kremlin lackey?”Footnote 102

Reception and Aftermath

To consolidate publicity, the long-delayed ICPP petition to the Soviet government, with a dozen American signatures, was issued simultaneous to the book's appearance. The result was some favorable press coverage, but also considerable blowback in the form of sustained criticism from Soviet agents and irritation among some of those not please to be associated with it. The journalist Carlton Beals was furious at finding himself on the list of ICPP members on the book's facing title page, especially given that he had not seen the material nor even the draft introduction ahead of time. “Even if I had been consulted”, he angrily chided Baldwin, “I would have considered the publication of the book on Russia as a grave error and would not have permitted the use of my name as a direct sponsor of its publication and its contents”.Footnote 103 Upton Sinclair, while not listed as a Committee member, was incensed that his reply to Levine had been included among the “Introductory Letters”, even if his had stressed his greater concern for political prisoners in California.Footnote 104 He also had no recollection of having agreed to sign the petition eighteen months earlier, and he groused that the combination of the blurb and the petition made him seem to endorse claims he might not want to and say things he no longer felt expedient.Footnote 105 Others were similarly disquieted. W.E.B. Du Bois, though he had neither signed the petition nor written an “Introductory Letter”, also worried that his name on the facing title page implied endorsement of something he had hardly read. It was only after some effort that Baldwin convinced him to remain affiliated with the ICPP.Footnote 106

Baldwin and his colleagues spent considerable energy on the defensive in the face of a swift, concerted effort to undermine both the book and petition, spearheaded by Kenneth Durant, head of the New York office of the Soviet telegraph agency. Durant quickly pestered both “introductory letter” writers and those listed as ICPP members to disassociate themselves from the book and the Committee.Footnote 107 Baldwin and his allies managed to limit the attrition to Sinclair and Beals, defending the integrity of the ICPP's actions and the authenticity of the Letters documents, while reiterating that their focus was already shifting to other ongoing projects.Footnote 108 Indeed, even as Alsberg had been buried in the final edits to Letters, Baldwin urged that they hasten work on Italy and Poland. For the latter, Alsberg turned again to Berkman and Schapiro, who, after some reluctance, were instrumental in procuring the documents for what became Political Prisoners in Poland, issued in early 1927.Footnote 109 The Italy book, comprising primarily reprints from The Nation and other similar items, appeared a year earlier.Footnote 110 While both volumes were less than a third the length of Letters from Russian Prisons, they established the ICPP's international purview, as did subsequent briefer pamphlets on Cuba, Venezuela, Portugal, and Peru.Footnote 111 Along the way, the ICPP worked with local activists, raising funds, protesting large-scale persecution, and pleading on behalf of specific persons directly to foreign governments, from Greece and Hungary to Cuba, China, and British India.Footnote 112 For a time, it also provided direct, if meager, financial support to Peshkova's “Aid to Political Prisoners”, until Baldwin admitted to her that to avoid the impression that they were favoring Soviet political prisoners, they were turning attention to other countries.Footnote 113

Baldwin himself remained conflicted about the best way to “criticize his friends”. Two years later, he took a trip to the Soviet Union to follow up with a full-length study, for which he would assert that Peshkova was one of his best sources of information, just as Harry Ward had in 1924. While, during the writing process, Baldwin checked his material with Berkman, Mollie Steimer, and other Bolshevik critics, the resultant Liberty under the Soviets rather uneasily acknowledged the continued repression while insisting there were greater “economic liberties” in the USSR than in the West.Footnote 114 Steimer sardonically replied to him that, “it looks strange that the same man who fights suppression of speech in one country, almost justifies it in another”.Footnote 115 Berkman, not surprisingly, was spitting mad at what he saw as Baldwin's folly, and yet the two remained on friendly terms, and the ICPP rushed to Berkman's aid in preventing his expulsion from France in 1930–1931.Footnote 116 And while Letters was the zenith of its public focus on Soviet prisoners, the ICPP periodically found ways to again fund Peshkova on the quiet – just as she preferred. An August 1931 report, for instance, noted that $500 had been raised so far that year for Russia, “used to provide food and clothing for political prisoners regardless of their affiliations”.Footnote 117 Alsberg, who had burned out from his intense early efforts and was no longer on the Committee's board, was still frequently the chief liaison for these efforts.Footnote 118

Baldwin's increasingly strained efforts to hold on to two utopias – civil liberties and Soviet socialism – eventually could no longer hold, but not before several more efforts to reconcile the irreconcilable; this included a last gasp attempt as late as fall 1934 in which he asserted in the propagandistic Soviet Russia Today that Soviet citizens possessed a “proletarian liberty” superior to civil liberties in the West.Footnote 119 These remarks reflected the continued obligation many Western intellectuals felt in the era of the Popular Front to find common cause with the Soviets during the rise of Nazism, and Baldwin later confessed to having erred, as a civil libertarian, in choosing between dictatorships.Footnote 120 While some, like the Nation's Louis Fischer, continued to defend Stalinism ferociously,Footnote 121 Baldwin's bravado belied mounting doubts. As the first wave of what became the great purges unfolded in winter 1934–1935, he composed a protest under the ICPP's aegis to the Soviet ambassador concerning the executions without trial of over one hundred persons accused of complicity in the assassination of Leningrad Party chief Sergei Kirov. Among those signing the letter were several who were key supporters of Letters ten years earlier, including Sinclair Lewis, the labor leader James H. Maurer, the writer and academic Robert Morss Lovett, and two of Baldwin's longtime ACLU colleagues, John Haynes Holmes and the civil liberties lawyer Arthur Garfield Hays.Footnote 122

The networks of Russian émigrés, Europeans, and American civil libertarians that produced the International Committee for Political Prisoners were not sufficiently integrated for it to develop into a more truly global organization. While the appeals of the Leagues of the Rights of Man also issued in the mid-1920s raised similar concerns about the treatment of Soviet political prisoners, they were issued separately, and only a handful of Europeans took active part in the ICPP moving forward. In many ways, the “Letters of Introduction” in Letters represented the highwater mark of transatlantic collaboration. The inability to leave partisanship behind also doomed the efforts of the Menshevik Abramovich and the anarchist Berkman, inspired by the international resonance their cause had briefly sparked, to unify émigré political prisoner aid efforts.Footnote 123 For Berkman's more militant anarchist comrades, the fact that the Mensheviks and SRs were engaged both in a similar campaign to expose Soviet repression and also in similar efforts to raise funds for their imprisoned comrades back in Russia was not enough to overcome their political differences. Even the collaboration with the Left SRs, who were more radical and thus closer to the anarchists, on the “Joint Committee for Imprisoned Revolutionists in Russia” lasted only from 1923 to 1926. After this point, the anarchist relief fund was run separately, while the moderate socialists maintained their joint émigré Political Red Cross branches, which coordinated with Peshkova well into the 1930s.

Despite this failure to unify such efforts, in comparing the various frames utilized in protesting injustices against political prisoners during the interwar period, we can begin to spot features of what would later be transformed into human rights discourse in the turn to universalist rhetoric resting on common principles. For the civil libertarian Baldwin, this was best expressed, at least in his cautious exposition of the situation in Soviet Russia, as defending freedom of expression, opinion, and association.Footnote 124 Several of the “Introductory Letter” writers, however, were more expansive. “If there is a single spot on earth where rights of men, regardless of whether they be criminals or ‘only’ political opponents, are spurned under foot”, opined the German novelist Bernard Kellerman, “then it is the duty of whosever still believes in justice and human dignity to point his finger at this spot continuously and emphatically until this spot disappears from the earth”.Footnote 125 Similar appeals to common principle, touching on both sentiment and law, may be found in the entreaties of the French Ligue and FIDH. Thus, the Ligue declared, “the feelings of humanity are not the prerogative of any party or of any people [but] remain the common heritage of civilized men”, while the International Federation denounced “the Soviet government's systematic and continuous violation of civil liberties in Russia, and the incessant persecution of citizens of all classes for crimes of opinion”.Footnote 126

Having helped bring “the horrors of Soviet prisons” to the attention of his European peers, Boris Mirkin-Getsevich soon turned to analyzing the question of “The Rights of Man in Soviet Russia”.Footnote 127 In so doing, he foregrounded “questions of conscience” and implicitly universalized the French Declarations of 1789 and 1793;Footnote 128 he was also a forceful supporter of his fellow émigré legal scholar Andrei Mandel'shtam's “Declaration of the International Rights of Man”. Adopted by the Institute of International Law in 1929 and endorsed by the FIDH two years later, this pioneering document explicitly demanded “recognition for the individual of rights preserved from all infringement on the part of the State”.Footnote 129 These various threads only truly coalesced later, starting with the formation of the International League for Human Rights in New York in 1942, just a year after the ICPP had finally ceased its continued efforts in various parts of the world. This organization originated in the desire of French refugees to preserve the legacy of the Ligues, led by the now twice-displaced Mirkin-Getsevich. Joining them was Roger Baldwin, who had given up entirely on considering himself a friendly critic of Soviet Communism and was looking to promote a more universalist utopia.Footnote 130