Archaeological compliance is defined by federal and state legislation to protect cultural resources from destruction and the loss of information about our shared heritage. Unfortunately, the constrained, precise language in which these documents are written stems from Western (Eurocentric) legal and scientific traditions that often exclude communities that do not share this lexicon or perspective. Rules and policies operationalize the law and provide some flexibility in its interpretation and implementation. However, the use of what we refer to as “the language of compliance” may be perceived as disrespectful or offensive to some Native communities in the context of interpreting cultural heritage and caring for the remains and belongings of their ancestors. In this article, we advocate for using respectful language when communicating with tribes, both written (preparation of compliance documents) and oral (consultations), when ancestral human remains and protected cultural items are a focus of concern.

Our experience with the language of compliance and its impact on Native American (Native) communities in the United States is largely rooted in the legal responsibilities of the Arizona State Museum (ASM) at the University of Arizona (UA) in Tucson and our working relationships with Native communities in Arizona and surrounding states, particularly the O'odham tribes of southern Arizona (Ak-Chin Indian Community, Gila River Indian Community, Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community, and the Tohono O'odham Nation). These are the tribes (sovereign nations) and Native communities (people with a shared cultural heritage) we are referring to when we speak about tribes in the remainder of the article.

Arizona has 22 federally recognized tribes (Figure 1) and more tribal land than any other state in the US, comprising nearly 28% of the state's land base (Arizona Department of Environmental Quality 2021)—nearly three times more than any other state. Arizona has the third largest population of Native Americans and the largest number of Native American language speakers (Language Magazine Reference Magazine2021). It therefore exhibits considerable cultural diversity and rich heritage among Native communities within the state. ASM has a long and enduring relationship with these communities, and it strives to celebrate and share this diversity with Arizona's residents and visitors to the region.

FIGURE 1. Map of federally recognized Indian Tribes in Arizona. (Courtesy of the Arizona State Museum.)

ASM was established in 1893 by the territorial legislature as one of UA's (established in 1885) original research units, and it is the oldest and largest anthropological research museum in the US Southwest. ASM's mission is to preserve, create, and share knowledge about the peoples and cultures of Arizona and surrounding regions. In addition to research, teaching, public outreach, and managing collections documenting the long history of human occupation in the region, ASM serves as the state's official archaeological repository and as the permitting authority for archaeological activity on state, county, and municipal lands.

ASM has long been actively involved in repatriation based on open communication and partnership with Native communities. In the late 1980s, Raymond H. Thompson, ASM director from 1964 to 1997, represented the American Alliance of Museums (then, the American Association of Museums) when he testified to Congress about the importance of federal repatriation legislation. He further expressed that cooperation between Native Americans, museums, and archaeologists was critical to the future of museums in America. In 1990, Arizona passed state statutes regarding the discovery and disposition of human remains (A.R.S. § 41-844 and § 41-865) that mirrored federal legislation—the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA, PL 101-610; 25 U.S.C. 3001 et seq., 1990)—enacted later that year. Therefore, ASM actively complies with federal and manages state legislation dealing with ancestral human remains and classes of protected cultural items.

Although the foundational elements of the modern repatriation movement extend back nearly 50 years, the passage of NAGPRA on November 16, 1990, codified rights of Native communities regarding their ancestral human remains, associated funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony, as well as the legal responsibilities of professional organizations that recover and manage ancestral human remains and protected items (Colwell-Chanthaphonh and Ferguson Reference Colwell-Chanthaphonh, Ferguson, Colwell-Chanthaphonh and Ferguson2008). The State Burial Laws Project (Washington College of Law 2020) identifies 27 states in addition to Arizona that have enacted similar laws. This body of repatriation legislation facilitates the transfer of control over archaeological human remains and protected items to affiliated tribes and is based in an ethical rhetoric designed to recognize the humanistic right for Native communities to control elements of their own cultural heritage. Repatriation legislation strives to strike a balance between descendant communities’ needs and rights to claim ancestral remains and items and the scientific community's desire to protect and preserve the archaeological heritage of the country. The reality in practice, however, provides a disproportionate degree of power to museums in producing inventories, making determinations about cultural affiliations, and communicating with tribes (McKeown Reference McKeown2012).

The application of repatriation legislation varies by state, but it is universally applicable under NAGPRA to federal agencies and institutions that have received federal funding. As part of the management of large collections, ASM has been repatriating human remains and funerary objects to claimant groups in the region since the 1930s (“Indian Cave Yields Fabrics of 934 A.D.,” New York Times, April 15, 1934). Our approach has evolved considerably over the years, and details continue to be malleable based on case-specific circumstances, but generally, we move through a five-step process that attempts to reduce error and ensure that all human remains and protected items are repatriated upon request (Watson et al. Reference Watson, McClelland and Pitezel2013). These steps include (1) extensive background research and reconciling records with existing holdings; (2) thorough documentation of remains and funerary items, including assessing all faunal material from the site(s) under claim to identify and remove previously unidentified human remains (up to 10% of the bone in these collections is human); (3) consultation with potential claimant communities; (4) publication of notices in the Federal Register; and (5) repatriation (final transfer of custody).

In Arizona, two state statutes (A.R.S. §41-844 and §41-865) provide for the protection and respectful treatment of human remains and specific classes of cultural items (funerary objects, sacred ceremonial objects, and objects of national or tribal patrimony) and require the notification of ASM and appropriate tribes when remains or protected items are encountered on state or private land. Upon notification, ASM initiates consultation with potentially affiliated tribes to determine the appropriate treatment of the remains and cultural items. Not reporting archaeological finds, or disturbing human remains without approval by ASM's director, is a Class 2 misdemeanor. Unlike existing collections curated by ASM that fall under NAGPRA, these statutes largely address new “discoveries” or disturbances, but they similarly center on the same approaches of consultation and repatriation.

To aid in the process of reporting disturbances of human remains and qualified items under the state statutes, ASM developed prenegotiated procedural documents—termed Burial Discovery Agreements (BDAs)—in consultation with tribes. BDAs specify the appropriate treatment and disposition for encountered remains meeting the conditions of A.R.S. § 41-844 and § 41-865, and they ensure that remains and protected classes of items are treated with respect and dignity at all times. When there is a reasonable likelihood that ground-disturbing activities may encounter human remains, the ASM Repatriation Office recommends obtaining a BDA prior to initiation of activity. Knowing these processes prior to disturbances reduces the potential for delay in projects and fosters greater cultural awareness and culturally respectful behavior.

More specifically, the use of a BDA can facilitate the response to an encounter with ancestral human remains by establishing clear notification protocols for the tribes and ASM, outlining appropriate procedures for the treatment of remains and protected cultural items for the tribes involved, providing a process and timeline for repatriation, and specifying the reporting requirements as defined by the statutes. Our perspectives—and the recommendations that follow—are therefore directly informed by long-standing partnerships, open communication, and consultations mandated by laws and regulations at the federal level (tied mainly to NAGPRA and Section 106) and state level with tribes related to the discovery, treatment, and disposition of ancestral remains, their associated belongings, and other ceremonial and sacred activities and locations.

COMPLIANCE AND THE TRIBAL NEXUS

In discussions surrounding compliance and its role in managing archaeological resources across land jurisdictions, it is important to remember that many cultural resource laws most significantly impact the cultural heritage of Native people, who control a small percentage of their ancestral homelands. Today, “reserved” land for tribes from their previous landholdings constitutes 2.3% of total US land. Most ancestral lands now rest in the hands of state, federal, or private ownership, with decisions impacting discovered cultural resources being made by agencies and individuals largely represented by non-Natives. This dramatic imbalance in the distribution of land and decision-making power creates a considerable hurdle for tribes that desire to participate in managing their heritage on those lands. For the vast areas not in their control, tribes are tasked with overseeing myriad archaeological investigations, acting when needed to prevent the potential destruction of their cultural heritage, and ensuring the security and repatriation of their ancestors’ remains. Furthermore, tribes must do all of this within the confines of a legal structure and language established by non-Native policymakers whose ideas of cultural significance and protection are frequently not aligned with their own. Despite these hurdles, tribes often seek opportunities within established cultural resource laws to advocate for their interests.

At its root, cultural resource management is defined by Western values that view the archaeological record and cultures of the past as a commodifiable substance that—as part of a responsible protection plan—should be extracted, studied, and preserved in perpetuity for the benefit of all (Colwell Reference Colwell2015; Nicholas and Hollowell Reference Nicholas, Hollowell, Hamilakis and Duke2007). However, cultural resources encompass a broad range of concepts beyond the material record, and the best mode of preservation for these objects may be counterintuitive to non-Native communities.

Archaeologists are trained to think of cultural resources as the features and artifacts associated with an archaeological site. For this reason, there is a common misconception in cultural resource management that highly developed areas no longer contain intact archaeological remains. However, this is constantly demonstrated by tribes to be false. As defined in relevant legislation, archaeological features and sites are not the only assets regarded as cultural resources. Several types of cultural resources important to Native communities are frequently unrecognized due to lack of cultural awareness, and they are therefore poorly protected by cultural resource managers. Traditional Cultural Properties (National Park Service 1992), sacred waterways, traditional activity sites, traditional gathering sites, sacred plant and animal habitats, creation places and homes of deities, astronomical occurrences and calendrical features, homes of ancestors, burial sites, and shrines are examples of cultural resources commonly omitted from protection plans by non-Native archaeologists. The ability to identify these resources requires cultural knowledge that one can only obtain by being a participant in that culture or by having someone of that culture share knowledge with you. However, a lack of Native representation in the management process threatens the protection and preservation of these resources. For Native communities, this means that they must be active participants in the process to ensure the education of resource managers, policymakers, developers, and others.

Consultation as an Apparatus for Change

The disturbance, excavation, and collection of Native American ancestral remains and material culture is woven into the development of American archaeology and the foundation of museum collections (Kakaliouras Reference Kakaliouras2014, Reference Kakaliouras2017; Rose et al. Reference Rose, Green and Green1996; Thomas Reference Thomas2000). The passage of repatriation legislation gave descendant Native communities the right to determine how ancestral human remains and funerary objects are treated. Consultation between tribes and museums became a requirement in the repatriation process and should be a fundamental element of archaeological compliance.

Consultation is an important mechanism for tribes to clarify the breadth of cultural resources that may be potentially impacted by impending development projects. However, consultations have often been problematic for tribes because of a lack of understanding and communication between the parties involved (i.e., tribes, agencies, landowners, developers, and archaeological contractors). Some tribal representatives experience a general feeling from participating consulting parties that Native American concerns are “an annoyance that must be tolerated.” Frequently, consulting parties participate in consultation meetings as an act of conciliation to move past the required procedural step. These meetings, which are key to determining the fate of Native American cultural heritage, are made more frustrating by the fact that many non-Native participants arrive to the process with predetermined outcomes that leave little to no room for creating a mutually beneficial solution or compromise with the impacted communities.

Further complications arise in the consultation process when there is concern over the perceived ownership of land, resources, objects, and ancestral remains. When consulting parties enter into discussions with antagonistic views, tensions can develop and limit the space for productive discussion and positive change. Fear is another significant factor that impedes consultation between tribes and agencies. Agencies often fear that tribes will impede operations, slow progress, or incur additional costs. In some cases, tribes fear what impact the work might have on cultural resources: What will be destroyed? What will be lost forever? What pain will the community potentially experience because of this work?

Cultivating Respectful Working Relationships

Some tribes have identified friction in the process of cultural resource management through a perceived lack of mutual respect and cultural sensitivity on the part of agencies and managers. Tribes often want agencies to understand their motivations in consultation and the importance of the consultation process to Native communities and cultural heritage. In addition, they want agencies to understand that a successful consultation, from their perspective, means meaningful communication, consultation in advance of a project or problem, resource avoidance when possible, and mutually beneficial development. These desired outcomes are sometimes dismissed in favor of the agency's own version of successful consultation, which includes completing the process of consultation (fulfilling an obligation), staying within project timelines, and completing a project with the least financial expenditure.

One of the most painful events Native communities can experience is the disturbance, desecration, and destruction of their ancestors’ remains, and this is a principal reason that consultation is a priority. Interments of ancestral remains are important and sacred to descendant communities, and their disturbance is a grievous injury that should be avoided if possible. If avoidance is not a viable option, then consultation can provide the most respectful procedures to follow. McClelland and Cerezo-Román (Reference McClelland, Cerezo-Román, Williams and Giles2016) argue that this process, from disturbance to reburial, is intimately linked to reconstructing identities, which involves characterizing and transforming the identities of the deceased. They argue that this means creating new identities of the deceased for different audiences and constitutes a reembodiment of the person (McClelland and Cerezo-Román Reference McClelland, Cerezo-Román, Williams and Giles2016:39). However, we argue that reembodiment or simply coming to terms with the identity of the deceased is largely facilitated by non-Native agency and cultural resource personnel, and it reflects differences between Western and non-Western concepts of identity. Western identity is traditionally recognized as egocentric, individualistic, differentiated, and independent, and it contrasts with non-Western identity, which is often sociocentric, interdependent, less individuated, and relational (Conklin and Morgan Reference Conklin and Morgan1996; Glaskin Reference Glaskin2012). In this vein, Native communities often view their ancestors’ remains as part of the (contemporary) community, outside of the bounded Western temporal perspective. Therefore, tribes are often not involved in an active renegotiation of deceased identities because such identities (e.g., “ancestor”) are largely considered inclusive and static.

The humanist perspective that many Native communities apply to ancestral human remains recognizes that all human beings are equal both in life and death and deserve to be treated with dignity and respect. More importantly, tribes reserve the right to decide what constitutes respectful and dignified treatment of their ancestors’ remains and belongings. These decisions include the words and actions people employ throughout the recovery and documentation process, the treatment and care afforded to the remains from the time of their disturbance to their repatriation and allowing the space for tribal representatives to perform traditional religious activities. Respectful and dignified treatment of ancestral remains includes protection from viewing, from contact with nonnatural materials, and from destruction due to inconsiderate handling or documentation. Respectful and dignified treatment also includes housing the ancestors in a private area away from activity and other collections until repatriation occurs. Collaboration with tribes has identified several other protocols that are used when caring for ancestral remains—such as limiting visitation—including protecting remains from activity when recovery work is not happening, limiting individuals near remains to essential recovery staff, and prohibiting such activities as eating, drinking, or using cellular phones in the vicinity of human remains. Following established recovery and documentation protocols, which include prohibiting photography, videography, and other recording methods; using natural materials in recovery and housing; maintaining security; and following culturally appropriate and respectful procedures throughout the process are all critical to respectful treatment of ancestral remains.

Most importantly, many tribes would like the archaeological community and those working with them to think of ancestral remains as living humans who should be treated with the same dignity and respect. One of the ways that compliance professionals can reinforce proper respect, behavior, and treatment is through the use of language when referring to and dealing with ancestral remains and their belongings. Some tribes have specific language they prefer when contractors are reporting information about individuals and protected cultural items. Often, the terms used by the cultural resource management community are offensive to Native communities in that they lack humanity. As a general guideline for what is respectful or appropriate, consider if what is being asked or stated would be said about a living human. For example, would it be appropriate for a person to say that they are storing their mother when she visits? Or that their uncle will be securely locked in a cabinet for his protection? If a statement or action would not be appropriate for a living person, then it is not appropriate for the ancestral human remains for whom we provide temporary care. The bottom line is that, as trained specialists, it is our professional imperative to ensure that human remains and protected cultural items are treated with respect and dignity at all times, which includes the language we use.

LANGUAGE AND CONSTRUCTED REALITY

Both the term and underlying concept of “cultural resources” are problematic in what they represent and how we interpret the subject. Concepts of cultural resources and their requisite protection are laden in Western scientific and academic traditions that view culture (i.e., the physical bodies and material production of culture groups) as a commodifiable substance that must be studied and preserved for the benefit of all. In this tradition, the practice of a preservation ethic often differentially focuses on past Native American cultural materials and facilitates the “othering” of Native communities by largely disconnecting the past and present. Documents that emanate from this tradition, whether compliance-related documents or academic publications, therefore project these traditional academic values and remove the agency and power Native communities have over their own cultural heritage (Thomas Reference Thomas2000; Wodak Reference Wodak2012). Language continuously reinforces the divide between compliance entities, such as museums, and the tribes with whom they are intended to partner.

Changing the language used when discussing indigenous cultures requires Native Americans to explain themselves within the dominant culture's discourse (Turner Reference Turner2006). Requiring Native peoples to explain themselves to the dominant culture necessitates those individuals acting as “word warriors.” A word “warrior” is an Indigenous person who “engages in the imposed legal and political discourse of the state guided by the belief that the knowledge and skills to be gained by engaging are necessary for the survival of all indigenous peoples” (Turner Reference Turner2006:92). Word warriors, therefore, engage in the legal process of repatriation for the return and control of their ancestors and cultural heritage. For word warriors to explain themselves, they must participate in constructing the type of language used in political and legal discourse. However, in order to do so, they first must be given the opportunity to participate and have their voices be heard and perceived as legitimate.

We refer to the constrained, jargon-laden vocabulary used in legal and academic documents as the “language of compliance” and identify several issues with its use in archaeological compliance and repatriation. First, the language surrounding research and compliance was established by non-Native communities, and it gives preference to Western traditions and ideals. Second, understandings of “appropriate” behavior in terms of cultural resources differ between communities, especially scientific and Native communities. Third, those most impacted by the handling of cultural resources must operate within the structure and language established by researchers and policymakers. Finally, the languages of science and compliance, which promote objectivity, often exclude a sense of humanity.

Archaeologists are largely trained within the positivist scientific tradition, which espouses (the illusion of) objectivity in research. The basic tenet of this tradition is that the application of a reproducible scientific process results in an objective perspective. Although it promotes an unbiased research effort, for archaeologists, it also effectively removes any element of human connection they might have with the remains or objects with which they interact. Consequently, the remains become objects of research that are reduced to being quantified in item counts and standardized measurements, assessed for materiality and design, and discussed in a codified language. As the language we use shapes our reality and perceptions, it is important that we acknowledge how the terminology of archaeological research and compliance influences our interactions with human remains and cultural materials.

There is considerable scholarship focused on the interaction between language and how we interpret our reality. As a foundational theory in linguistic anthropology, the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis holds that language determines thought and therefore constructs a reality, shared by members of a linguistic community (Sapir Reference Sapir1929; Whorf Reference Whorf1940). A form of “linguistic determinism” (Boroditsky Reference Boroditsky2001), it has long been set aside to acknowledge the speaker's agency and intentionality behind language and word choices. However, numerous experiments since Whorf's formalization of the concept have demonstrated that “one's native language appears to exert a strong influence over how one thinks about abstract domains” (Boroditsky Reference Boroditsky2001:18), such as gender (Sera et al. Reference Sera, Berge and del Castillo Pintado1994), color (Rosch Reference Rosch1975), spatial thinking (Bowerman Reference Bowerman, Gumperz and Levinson1996), and time (Boroditsky Reference Boroditsky2001). Language has also been shown to influence conceptual development (Waxman and Kosowski Reference Waxman and Kosowski1990). It confines emic experiences by making them “grammatically obligatory” and therefore biases speakers to encode distinctions unique to their lexicon (Boroditsky Reference Boroditsky2001:2). We would extend Boroditsky's “abstract domains” to include how individuals think about or “experience” death and concepts of the afterlife. Therefore, in addition to cross-linguistic differences in concepts of time, how individuals from Western linguistic traditions think about the deceased compared to any given Native American tradition may differ significantly.

At a basic level, however, language can be used to construct, reinforce, or alter perceptions. Deborah Cameron (Reference Cameron2009:12), in examining false perceptions of language differences between men and women, identifies that “the relationship between the sexes is not only about difference, but also about power.” The same is true with the use of the language of compliance, whereby people enculturated within a predominantly Western scientific tradition share a code that needs to be deciphered and regurgitated to warrant engagement and be afforded the respect of attention. This creates a power dynamic that disadvantages groups whose worldviews differ. The language of compliance, founded in both law and science (with their respective linguistic conventions), is as culturally constructed as any other linguistic tradition.

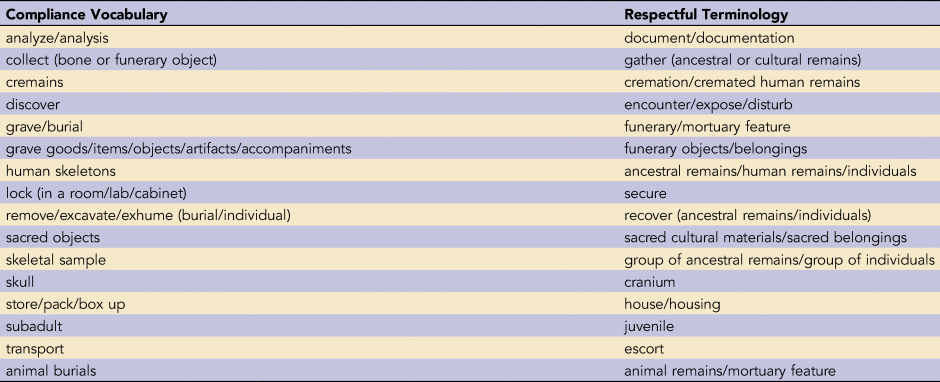

We argue that one of the ways compliance professionals can foster respectful behavior in their work is through the use of respectful language when referring to and interacting with ancestral remains and their belongings. The table below (Table 1) was developed in conjunction with tribal representatives, and it highlights some of the small but significant terminological changes we can make to redefine our interactions with ancestral remains and the Native communities with whom they are connected. We advocate for the use of this language when communicating with Native communities about human remains and protected cultural items. This includes both written communications, such as when preparing compliance documents or reporting an inadvertent discovery of remains, or oral communications, such as during formal NAGPRA consultations.

TABLE 1. Compliance Vocabulary and Suggested Respectful Terminology.

An example of a minor change in word choice that can have significant implications is by substituting “juvenile” for “subadult” to describe an individual who has yet to achieve skeletal maturity. Osteologists often apply the term “subadult” to individuals aged from three lunar months to 20 years (Buikstra and Ubelaker Reference Buikstra and Ubelaker1994); however, using this term to refer to individuals within this age category is problematic because the prefix “sub” qualifies something as “under, below, subordinate, secondary, or less than complete” (Merriam-Webster dictionary, www.merriam-webster.com). Consequently, attaching the prefix “sub” to the word “adult” implies that the individual is less than or below an adult. This tacit designation of an individual's inferior status is unsuitable because it assumes that this view is applicable across cultures, which is not the case. Each culture's understanding of what it means to be an adult, or some other phase of personhood, is dependent on its own beliefs. Understanding categorical values of age within a society's own norms—a culturally relativistic understanding—should be considered best practice in archaeological compliance work. We acknowledge that replacing “juvenile” for “subadult” may not directly contribute to the restoration of a community's agency and power over its ancestors, but we argue that it does contribute to restoring some of the humanity to deceased individuals by removing elements of value-laden language, and it ensures that we are respecting the cultures with which we work.

Most of the respectful terminology presented in Table 1 works toward this broader goal of restoring humanity to the remains of deceased individuals. Many of the words we identify as part of the larger lexicon of compliance can be additionally harmful to Native communities because they reflect and recall a period when their ancestral remains were regarded as scientific “property.” Words often used by archaeologists—such as “analysis,” “collect,” and “sample”—are terms associated with antiquated approaches to studying the past. The dehumanizing anthropological research of people such as Earnest Hooton and Samuel Morton actively focused on “collecting Indian skulls as samples for analysis to preserve in museum collections.” Morton's work directly contributed to racist, eugenic concepts about cognitive ability. He concluded that the “Indian brain” was deficient, that Native American populations could not be civilized, and that their minds were drastically different from those of the white man (Thomas Reference Thomas2000). Hooton's work on Native American crania from Pecos Pueblo focused on reinforcing racial stereotypes and Lamarckian concepts of inheritance (Cook Reference Cook, Buikstra and Beck2006). By changing some of the language used when communicating with cultural resources professionals and Native communities, we can move beyond these racist approaches that largely defined the beginning of anthropology as an academic discipline.

Repatriation is about building relationships and acknowledging another party's legitimacy to determine the outcome of the exchange of items and knowledge (Killion Reference Killion and Killion2007), but ultimately, it is an act of sovereignty for tribes. Language is a critical component of how those relationships are constructed. The use of respectful terminology should not be limited to how Native American ancestral remains are written about but extended to how they are spoken about. At the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, human remains are housed in an area colloquially referred to as “the attic,” a term the museum is trying to phase out (Lippert Reference Lippert, Colwell-Chanthaphonh and Ferguson2008:124). It is harmful to think of how one's ancestors were not only forcibly removed from their intended final resting place without the consent of direct descendants but then housed in “The Nation's Attic.” A primary point of collaborating with Native communities to develop preferred terminology is to not only be respectful of their connections with their ancestors but also provide multivocality where historically there has only been the Western voice. The goal should not be to silence anyone's voice or stipulate how one expresses one's voice, whether from the agency or compliance perspective or from the perspectives of Native communities. Lippert (Reference Lippert, Colwell-Chanthaphonh and Ferguson2008) argues that parties involved in repatriations should not silence one another, ignore one another, or talk over each other. Instead, they should listen to one another and respect the different viewpoints being expressed. We argue that with a shared, respectful terminology, communication and understanding between voices will be strengthened and serve to benefit the compliance process for all parties involved.

Finally, our recommendations for respectful terminology focus around legal requirements at the federal (NAGPRA) and state level (Arizona burial laws) related to the discovery, treatment, and disposition of ancestral remains, their associated belongings, and other ceremonial and sacred activities and locations. The terminology we propose is neither exhaustive nor universally accepted, and the concept can certainly be applied more broadly in the discipline. Thinking about and questioning the (often discipline-specific) language used in archaeology to interpret, describe, and communicate about the cultural heritage associated with living descendant communities has the potential to not only improve relationships between practitioners and community members but also better inform the public. For example, the use of the term “ruins” is a common term applied to ancient Native American settlements. The connotation, however, is often perceived of as negative—it indicates that the site is used up, destroyed, and no longer has any meaning beyond its “scientific value.” This dismisses the deep connection experienced by some communities to the places where their ancestors resided and that these communities may continue to use for ritual or spiritual purposes.

CONCLUSIONS

Repatriation has changed the relationship between Native communities and institutions that house their ancestral remains and cultural belongings. NAGPRA helped elevate the voices of Native communities within a legal framework, and because of their input, museum and compliance professionals are required to adopt new behaviors through legally mandated consultations. Consultation defined in NAGPRA is the process of exchanging information through open discussions and joint deliberations concerning potential issues, changes, or actions by all interested parties (HR 101-877). However, institutions that emphasize collaboration over consultation have better relationships with tribes (Goff et al. Reference Goff, Chapoose, Cook and Voirol2019; Grant and Ganteaume Reference Grant, Ganteaume, Hays-Gilpin, Herr and Lyons2021). Collaborative repatriation programs are ones in which tribal representatives are involved in each aspect of repatriation, with goals jointly developed, and ones in which the voices and rights of tribes are genuinely heard and given priority.

In many cases—and for too long—archaeologists have failed to afford the proper respect and dignity to ancestral remains by denying them their humanity and continuing to harm Native communities through compliance work. Compliance legislation provides the legal framework for the preservation of cultural resources, but the majority of cultural resources disturbed are associated with Native Americans, and it can cause grievous injury when ancestral remains are disturbed. Consultation is critical and must be pursued with mutual respect and cultural sensitivity, including the use of respectful language. Acknowledging that language can shape our perceptions, ASM advocates the use of terminology that is respectful of the concerns of Native communities in compliance reporting and interactions regarding ancestral remains and their belongings.

It is also critical to appreciate the rich cultural diversity of the Native communities that institutions may interact with and recognize that what is appropriate for one tribe may not be appropriate for another. Open and respectful communication is both the first goal and the key to building successful relationships. The respectful terminology we are advocating here is founded in our experiences in building relationships between Arizona's Native communities and ASM. We therefore encourage the adoption of similar approaches elsewhere in the United States among institutions and agencies that are charged with cultural resources compliance and in consultations with local tribes to ascertain the terminology they feel most comfortable with and learn about terms that they find insensitive or objectionable.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all our colleagues and partners in institutional, cultural resources management, and tribal roles—particularly the O'odham tribes of southern Arizona (Ak-Chin Indian Community, Gila River Indian Community, Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community, and the Tohono O'odham Nation). We are grateful to the editor and two anonymous reviewers, whose comments made for an improved manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article because no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this article.