During the last commodity boom, in the 2000s, the number of people moving into small-scale and artisanal gold mining—an independent and informal activity that relies on rustic extractive techniques (Veiga Reference Veiga1997)—dramatically increased in the Andean region. Currently, estimates say that between 350,000 and 500,000 citizens in Bolivia and Peru are dependent on the activity (ASM 2017). This uncontrolled expansion exemplifies a challenge common to resource-dependent economies: fast-rising demand for a number of internationally traded commodities has boosted their rapid growth while also exacerbating existing resource governance challenges, such as the empowerment of informal groups that vie with the state and big business for the control of key resources.Footnote 1

The case of informal gold miners in Bolivia and Peru is emblematic in this sense, as miners in both countries were able to influence the formulation and implementation of national resource policy. In Bolivia, miners blocked most of the regulatory reforms and persuaded the state to increase the budget devoted to microcredit and training; in Peru, the government was forced to derogate punitive decrees, and ultimately agreed to negotiate legal changes to facilitate formalization.

This similarity in outcomes is particularly puzzling given the striking cross-country difference in miners’ political empowerment and the institutional tools at their disposal. While this divergence has deep historical roots, this trend has been reinforced over the last 20 years, since Bolivia adopted a sociopolitically inclusionary approach (Anria Reference Anria2018), leading to the political incorporation of several organized groups, including informal miners, by the Movement Toward Socialism (MAS) government. On the other hand, lack of representation and marginalization of social demands have characterized the Peruvian political scene during the same period (Cameron Reference Cameron, Levitsky and Roberts2011). In this context, Peru has recognized informal mining as illegal and has opted for a coercive strategy against it.

These different trajectories suggest that the capacity of informal miners in Bolivia to influence policy outcomes is to some extent to be expected, while the same cannot be said about their Peruvian counterparts, who, despite their exclusion, managed to force the central state to the negotiating table. Why and how were informal miners able to influence national resource policies? If different patterns of state-society relations fail to explain miners’ ability to shape policy outcomes, the explanation must be sought somewhere else.

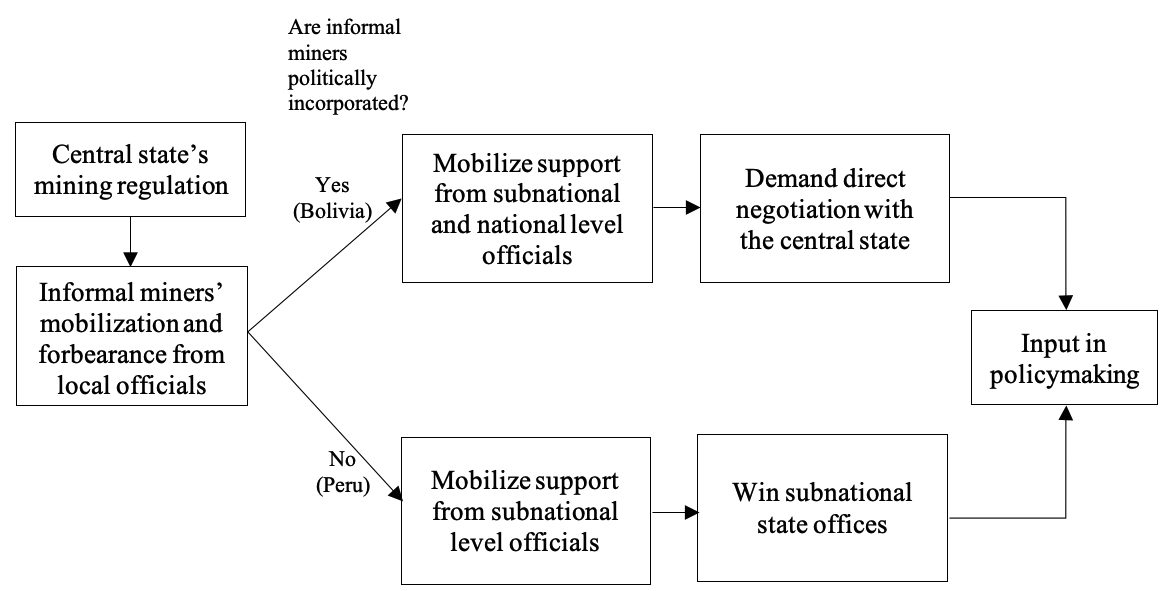

This study argues that informal groups, such as gold miners, have developed different strategies to gain influence over policymaking, contingent on the opportunities that each institutional context provides them. This article puts forward a comparative sequential study of bottom-up policy change. At first, miners engage in social mobilizations and use local elected officials’ forbearance to preserve their productive activity as a minimum goal.Footnote 2 Encouraged by the local economy’s dependence on gold mining, local state-miner alliances consolidate and form informal pressure groups to defend the benefits of the activity against national regulations. As the central state’s attempts at regulation intensify, miners are forced to take a more proactive posture, which varies according to their degree of political incorporation.

Where they have representation, as in Bolivia, miners mobilize the support of national-level officials and eventually use their endorsement to demand direct negotiation with the central state. By contrast, where miners lack representation, as in Peru, they strengthen their ties with regional and local elected officials, who become open representatives of miners’ interests. Often miners themselves run for office and get elected, gaining access to a direct channel of communication with the central state. In both cases, massive mobilizations and public exposition of the state’s internal contradictions legitimize miners’ demands and force the central state to back down and directly negotiate with them.

Building on 120 semistructured interviews with policymakers, elected authorities, and mining leaders conducted between 2015 and 2017 in rural La Paz and Madre de Dios—the largest gold-mining communities in Bolivia and Peru, respectively—this article contributes to literature on state-society relations by showing the conditions and multiple pathways through which informal groups can gain influence over policy outcomes. I argue that the state might put forward different institutional and political arrangements, develop different enforcement strategies, and yet fail in the implementation if it does not take into account local dynamics. Through a disaggregated study of the state, I find that the fracture between its central and peripheral branches creates opportunities for state contesters to exert contention in alliance with local officials.

This argument also adds to resource politics by shedding light on the collective capacity of an overlooked, nonelite societal actor—informal miners— that contributes to the externalities of extractivism and whose participation in socioenvironmental conflicts in the region has not yet been fully mapped. Furthermore, this work speaks to literature on decentralization by showing how devolution processes aimed at increasing state control failed to fundamentally change intergovernmental relations and further deepened cleavages around resource governance.

The article is divided as follows. First, it outlines the conditions that created political opportunities for excluded groups to influence policy outcomes. It extends the work on forbearance by showing how this exposes the conflict of interests between central and peripheral state actors. It then discusses the empowerment of informal pressure groups. The theory explains why, despite facing different state strategies of control, informal groups are able to take over local representative institutions and use them first as a shield against central state regulation and then as a springboard to push their agenda. The study concludes by drawing theoretical implications for the findings and future lines of research.

BEYOND THE FOCUS ON NATIONAL-LEVEL FACTORS

Scholarship on commodity-driven economies in Latin America concurs that the pervasive effect of resource wealth on state development is contingent on the sociopolitical conditions before the commodity boom. Favorable economic contexts can trigger different behaviors from economic elites depending on the existence (or breakdown) of pacts between them and state officials (Karl Reference Karl1997; Kurtz Reference Kurtz2013; Saylor Reference Saylor2014). The underlying assumption in all these cases is that elites are the main social actor influencing resource governance in commodity-driven economies.

On the other hand, the participation of nonelite groups from society has been conventionally reduced to contesting the externalities of extractivism—either leading social movements that expose the socioenvironmental costs of extractive projects (Bebbington Reference Bebbington2012) or pushing for redistributive and participatory reforms (Arellano-Yanguas Reference Arellano-Yanguas2011; Arce Reference Arce2014). This is not, however, the only instance in which nonelite groups participate in resource governance. I extend my analysis to other actors that also raise competing claims over resource governance but who participate in extractive activities. This is the case with informal miners, who, despite their marginality, have the power of influence over policy outcomes from the bottom up. Yet very few studies have addressed their relationship with the state in comparative perspective.

Baraybar and Dargent (Reference Baraybar and Dargent2020) constitute an exception. They argue that while inaction was the state’s conventional response to informal mining, current variation in state responses to informal mining is explained by the degree of organization of societal actors. In Bolivia, the high degree of organization of mining cooperatives and their close ties with the government have resulted in limited state enforcement efforts. In Peru, where informal mining lacks preexisting organized political actors, the state chose to ignore the phenomenon until the pressure from different civil society groups pushed for law enforcement.

Although this argument advances in situating informal miners as political actors and state contesters of resource governance, the argument suffers from theory stretching; that is, it inappropriately applies national-level theories to other levels of analysis (Giraudy et al. Reference Giraudy, Moncada and Snyder2019), and it does not account for two related factors: local dynamics and miners’ strategies and demands. By limiting the analysis to national-level dynamics, the state looks like a monolith with no internal contradictions. This creates the illusion of a coherent state whose decisions are aligned with the interests of its representatives throughout the territory—which is rarely the case in the Andean context. Neither can we observe how subnational groups tackled by mining regulation respond politically to the central state.

By contrast, a bottom-up perspective shows us a more complex and dynamic picture of state-society relations, in which both state and nonelite societal actors mobilize formal and informal political resources (state institutional and noninstitutional assets), enabling them to make claims over decisionmaking processes and further their interests (Piven and Cloward Reference Piven, Cloward, Janoski, Alford, Hicks and Schwartz2005). This study looks at key moments of reform in Bolivia (2009) and Peru (2010), where new rules for informal mining were discussed with the aim of enhancing the state’s power of control. It disaggregates the state’s behavior at two levels—the national state (represented by central state authorities) and the subnational state (represented by regional and locally elected authorities)—to assess the degree of coordination between state officials and their positioning in regard to informal mining and new regulations. This allows for the study of how the conditions previous to the economic boom impacted subnational peripheral actors’ capacity for action and their response to central state mandates.

STATE FRAGMENTATION: AN OPPORTUNITY FOR BOTTOM-UP CHANGE

I argue that in unequal societies, the lack of coordination between the central state and the periphery provides an opportunity for those at the bottom of society to push for institutional changes. This is particularly true in the case of Andean states, which still struggle to provide basic services and establish control evenly all over the territory (Gray Molina Reference Gray Molina, Crabtree and Whitehead2008; Krupa and Nugent Reference Krupa and Nugent2015). The effects of this lack of coordination and abandonment are twofold. On the one hand, regulations are generally ineffective, as they lack both knowledge of the local context and resources to be enforced (O’Donnell Reference O’Donnell1993). Hence, forsaken peripheral actors enjoy a high level of autonomy. On the other hand, the local state struggles to separate its interests from local society’s, and as a consequence, the boundaries between the two are blurred (Gupta Reference Gupta1995).

Center-periphery fragmentation in countries such as Bolivia and Peru was intensified by processes of decentralization and an immigration wave in the mid-1990s that brought up new political actors from the rural world (Tanaka Reference Tanaka2002; Kohl Reference Kohl2003). The central state, despite pushing forward the reform, was not able to use devolution processes to reform intragovernmental relations. Decentralization granted regional and municipal authorities more power—it increased their political and economic autonomy—but the central state did not engage in significant efforts to integrate their feedback on governance. The state continued to maintain its distance from the periphery, and the most important decisions were still made unilaterally by the central state (Toranzo Roca Reference Toranzo Roca2006).

Traditional national political parties in both countries were also unable to adapt to the new sociopolitical reconfigurations. Due to their centralist structures, national parties failed to recruit local leaders and adapt their agendas to the new local demands (Vergara Reference Vergara2016). This led to a process of delegitimization of the political establishment, which ultimately resulted in the collapse of the party system in Bolivia and Peru (Mainwaring Reference Mainwaring2006).

Without clear strategies of articulation of intrastate institutions and no leader-ship from national political parties, regional agendas further detached from national ones. Motivated by the political vacuum and the new powers of subnational state offices, independent coalitions and members of urban and rural associations acquired a more prominent role in local politics (Postero Reference Postero2007; Tanaka Reference Tanaka2007).

Thus, decentralization in Bolivia did not help to facilitate the state’s penetration of the hinterland, but on the contrary, it led to “the ruralization of politics”—where the new political spaces served to empower actors from the rural world (Zuazo Reference Zuazo2008). New political groups, such as MAS—a coalition of peasant and indigenous movements—emerged and won office, bringing about a new national-level political agenda targeting rural sectors. Yet these groups never fully committed to abandoning their autonomy, which meant that top-down compliance continued to be a challenge in Bolivia (Mayorga Reference Mayorga2009). In Peru, where civil society is less organized, processes of devolution also created incentives to strengthen regional identities and loyalties. New independent forces emerged in every region, with political programs distant from those of national political parties (Zavaleta Reference Zavaleta2014), though none of them achieved the success of MAS.

The new political spaces exposed important cleavages around resource governance. Decentralization provided local authorities with more powers over resource management and revenue distribution. These structural changes generated incentives for the political mobilization of new actors with claims on resource management and profit redistribution. As in other commodity-dependent economies in the Global South (Verbrugge Reference Verbrugge2015), decentralization in the Andes, instead of contributing to reaffirming the state’s authority, deepened long-term institutional uncertainty and exacerbated conflicts about who had legitimate decision power over local governance.

PERIPHERAL PRESSURE GROUPS AND THEIR CHALLENGE TO THE CENTRAL STATE

The persistence of center-periphery fragmentation posits a dilemma of authority to local officials about whom they should respond to—the central state or the local population. Although earlier studies assessed the inability of central states to enforce laws evenly as a sign of institutional weakness (Helmke and Levitsky Reference Helmke and Levitsky2004), scholarship focusing on the agency of officials provides a different view. There are instances in which unevenness can be explained as the result of selective enforcement, given bureaucrats’ disagreement with the law (Mahoney and Thelen Reference Mahoney and Thelen2010), their reinterpretation or adaptation of the law (Tsai Reference Tsai2006), or the prioritization of certain policies over others in light of limited resources (O’Brien and Li Reference O’Brien and Li1999). In this latter strand of literature, the concept of forbearance—the intentional nonenforcement of the law—stands out, as it highlights the willingness of authorities to be lenient toward infractions if it brings redistributive benefits that they themselves are unable to provide (Holland Reference Holland2017). What distinguishes forbearance from other cases of nonenforcement is the political intent to cater to the demands of the poorest sectors in the absence of welfare provision.

The concept of forbearance is useful because it illustrates the sociopolitical consequences of how local officials decide to resolve authority dilemmas: having to deal with inadequate social policies from the central state, they choose to accommodate citizens’ claims as they can. I use forbearance as a point of departure to investigate peripheral political interests that are incompatible with the central state’s goals. Since natural resources constitute a key source of revenue for developing nations, forbearance on mining regulation is particularly costly for the state. Yet during a commodity boom, local officials tend to collaborate with informal resource groups because effective regulation exceeds their enforcement capacities. Moreover, leniency toward informal activities legitimizes officials’ authority in the face of a highly influential sector of the population and is electorally profitable.

However, in contexts of exclusionary resource governance policies, I contend that leniency toward informal activities is only one of the (in)actions signaling the rise of alternative means of interest articulation. Given that local informal actors often participate in semilegal or illegal practices, the continuity of their activity still depends on their relationship with the authorities. Thus, they will actively seek to get officials to comply with their demands by hiring intermediaries (Hummel Reference Hummel2018), supporting political campaigns (Gingerich Reference Gingerich2013), and, as described here, mobilizing popular support. Constant engagement and cooperation over time consolidates loyalties and commitments between informal actors and officials.

The relationship between local officials and informal groups cannot be reduced to pork barrel politics. Neither is this a case of warlord politics (Migdal Reference Migdal1988), where coercion becomes the driver of compliance. Quite differently, the main source of local loyalties against central state regulation is the great level of economic dependence on informal networks, which can absorb the unskilled labor force in areas where there are no productive alternatives or state support (Canaviri Reference Canaviri2015; Toledo Orozco and Veiga Reference Toledo Orozco and Veiga2018). The continuity over time of these informal networks has contributed, in turn, to the creation of informal extractive regimes that claim a share in the benefits of exploitable resources, directly benefit local communities and officials, and as a consequence, ensure stability at the local level (Snyder Reference Snyder2006). Given their unique benefits to both informal actors and authorities, these regimes will then be strongly defended through the formation of pressure groups. These are small groups that, in the face of positive or negative incentives—such as securing economic gains or state sanctions—mobilize in favor of the interests of a larger group (Olson Reference Olson1971).

Figure 1 summarizes the sequential process and situates the two country cases. I argue that when facing a continuous threat to their informal activities, the strengthening of local ties between informal actors and local authorities will translate into stronger pressure against the central state. Thus, officials go from being lenient toward informal groups to actively defending their cause. Where informal actors have been politically incorporated, they will also demand the support of their national-level representatives. This is the case for Bolivia, where miners can openly participate in politics; they have access to authorities working both at the local and national level. But not for Peru, where informal miners have restrictions on participating in national politics, as their activities are considered illegal, and therefore they cannot have open political representation.

Figure 1. Sequential Process of Bottom-up Policy Change

Local officials will demonstrate their support by voicing the concerns of the informal groups to the central state, participating in protests, conceding a more prominent role in lawmaking debates to these groups, publicly defying national law, and pointing at bureaucratic mistakes and loopholes. This will give informal pressure groups an opportunity not only to defend their interests but also to expose the loyalty of state officials to their local constituency above the goals of the state. As contention with the central state builds up, it becomes more and more difficult to draw a clear line between the state and society at the local level.

I find that informal groups gain not only from the support of officials but also from stripping the state of any semblance of internal coherence. They challenge the state’s legitimacy to impose rules by exposing the central state’s lack of popular support at the local level and its weak organizational capacity to implement policies. Informal groups have motivations to expose such vulnerabilities, knowing that when institutions are perceived as unstable and rules as difficult to enforce, they are less likely to be respected or to endure (Levitsky and Murillo 2009).

The delegitimization of state institutions helps both politically incorporated and excluded informal groups to gain ground. At this point, informal groups are not only trying to avoid regulation; they are also mobilizing to push their own agenda. Depending on the institutional tools at their disposal, they will do so in opposite ways. The exposure of the state’s fragmentation and incoherence will serve politically included groups to demand that the central state engage in direct negotiation with them without intermediaries (i.e., local officials) to strike a compromise on regulatory regimes. On the other hand, the same condition will generate incentives for politically excluded groups to run for local state offices in order to gain access to a platform from which to voice their demands to the central state. This allows them to advance from informal veto players to active participants in policy drafting.

METHODS

I undertook a comparative sequential study of Bolivia and Peru. Sequential analysis is suitable for this study as it incorporates cross-case analysis and within-case analysis simultaneously (Falleti and Mahoney Reference Falleti, Mahoney and Thelen2015; Falleti and Riofrancos Reference Falleti and Riofrancos2017). I inductively traced the key events in the formation of pressure groups to identify what kind of dynamics were particular to each country and what could be generalized. At the same time, the comparative nature of this study allowed me to explain why, despite different state feedback, the same outcome was observed in both cases.

I have also drawn inspiration from the work of Giraudy et al. (Reference Giraudy, Moncada and Snyder2019) on cross-country subnational research. By working with a multilevel perspective, my study aims to focus on the interactions between national and subnational factors that could provide a refined understanding of policy outcomes. To this end, I have made multiple visits to the capital cities of Bolivia and Peru to interview representatives from the Ministry of Mines, the Ministry of the Environment, vice ministries, and parliamentary members working on small-scale and artisanal gold-mining legislation. The information provided was contrasted with the findings from interviews of leaders of gold-mining federations. I also reviewed law drafts, executive decrees, and mining laws in each country.

Locally, my fieldwork focused on the trajectory of gold-mining associations and cooperatives that appeared with the last commodity boom in the 2000s, as these were the main targets of the policies. I interviewed governors, mayors, and former mayors, as well as leaders of associations and cooperatives in La Paz and Madre de Dios, the regions in Bolivia and Peru, respectively, with the highest number of informal gold-mining workers and gold production in each country. La Paz concentrates more than 90 percent of the total number of informal gold-mining cooperatives in Bolivia: approximately 1,100, with about 5,100 members (Viceministerio de Cooperativas 2016) and a greater number of assistants. In Madre de Dios there are between 30,000 to 100,000 miners, including assistants, producing about 70 percent of the total informal gold mined in Peru (SPDA 2015).

The period of study starts at the end of the first decade of the 2000s, when gold prices rose from US$279.17 in 2000 to $1,225.29 per troy ounce in 2010 (ASM 2017), the number of miners peaked, and Bolivia and Peru drafted laws to regulate informal mining. The period under analysis ends with law changes in favor of informal mining in 2014 and 2015, respectively.

THE ORIGINS OF INFORMAL MINERS’ PRESSURE GROUPS

The popular takeover of institutions by informal miners is possible in regions that are both forsaken by the central state and lacking in productive alternatives capable of absorbing the local working class. La Paz and Madre de Dios share both these conditions. Although the region of La Paz in Bolivia is also home to the administrative capital of the country, rural areas—where mining proliferates—have been historically neglected. Rural La Paz shows the highest levels of poverty in the country (Arias and Robles Reference Arias, Robles, Bedi, Coudouel and Simier2007). Likewise, Madre de Dios, like all Amazonian territories in Peru, has never been part of national development projects (Damonte Reference Damonte2018). The region has consistently performed below the average rates of development, and before the commodity boom, only half the population had access to health and education (INEI 2001).

Labor opportunities are scarce in both places, too. Mining communities in rural La Paz, such as Sud Yungas, Abel Iturralde, and Larecaja, lack proper infrastructure and economic development plans, which has impeded the expansion of agriculture in the few areas where coffee and fruit plantations are possible. Lack of opportunities in these communities has pushed younger generations to migrate. On average, over the last 20 years, 40 percent of the population of La Paz has migrated from rural areas to the urban capital of the region (UDAPE and INE 2018).

The picture is not that different for the communities in Tambopata, rural Madre de Dios. Aside from brief colonizing episodes when the Amazon witnessed rubber and gold booms in the late 1800s and the 1960s, labor opportunities have been either very limited, not suitable for everybody—such as logging or drug trafficking—or incipient—such as chestnut production or ecotourism (SPDA 2015). Before the mining boom, annual emigration from Madre de Dios to other regions reached on average 13 percent (Yamada Reference Yamada, Garavito and Muñoz2012).

The rapid rise of gold prices in the last two decades set in motion a transformative process for rural communities with gold deposits (Poveda et al. Reference Poveda, Nogales and Calla Ortega2015). In both regions, informal mining became the most—if not the only—profitable activity for small local economies. Informal gold mining represents 29.5 percent of the regional gross domestic product (GDP) in La Paz, peaking at almost 40 percent in 2015, and is the third-most employment-generating activity (INE 2018). In Madre de Dios, informal mining represents 41 percent of the regional GDP, and 70 percent of the local economy is linked to activities associated with gold extraction (El Comercio 2018). This has created a high level of dependence between the region’s growth and gold production; when gold production is high, it positively reflects on the GDP of Madre de Dios, and vice versa.

Exclusion and lack of local productive alternatives has generated the same outcome of political activation in other areas, such as Oruro in Bolivia or Northern Puno in Peru, where miners have become the main political actor. The case is not atypical in the region, either. During the gold rush of 1979, the contribution of garimpeiros (informal miners) to extremely poor local economies in Brazil allowed them to transform the towns and become highly influential decisionmakers (Cleary Reference Cleary1990). By contrast, in regions with other productive activities capable of absorbing the local labor force, the boom increased the number of miners, but it did not lead to their political activation. This is the case of Cochabamba in Bolivia or La Libertad and Piura in Peru, where agriculture or fisheries are prominent.

MINERS’ POLITICAL ACTIVATION AND FORBEARANCE FROM LOCAL OFFICIALS

By the end of the first decade of the 2000s, the governments of Bolivia and Peru faced dilemmas related to their core constituencies and their electoral promises. In Bolivia, the MAS, under the leadership of Evo Morales, was committed to supporting social organizations, such as mining cooperatives, which were key to its electoral success. At the same time, to expand the tax base and regain control over land distribution, in 2007 the government stated its interest in increasing its share from extractive activities and declared all the national territory as mining fiscal reserve— which grants the state the power to exploit all the mining resources and renegotiate the terms of mining concessions that were still pending approval (Supreme Decree 29117). This change was part of the MAS agenda oriented toward enhancing state powers, and it came to replace austerity reforms from 1985 limiting state intervention and leaving the administration of resources to market forces. Although President Morales delayed the execution of the decree, the mining sector’s crucial contribution to the economy and the financing of social programs made the reform of the mining law inevitable by 2009.

The decisions quickly generated a response at the local level. Membership in unions, such as the National Federation of Mining Cooperatives in Bolivia (FENCOMIN), and especially regional federations, such as the Federation of Mining Cooperatives of La Paz (FEDECOMIN), was boosted.Footnote 3 “The fear of our mining brothers was that the interests of private mining companies or other actors would predominate in the law reform,” explained Simón Condori, leader of FENCOMIN (Interview, La Paz, October 8, 2017). Along with a rise in membership, multiple mining towns started protesting and went on strike. Whereas federations were in charge of coordinating activities and strengthening channel of communication with local authorities, popular mobilizations served to raise awareness about the many different social groups that would be affected by the reform.

To avoid partaking in the conflict, local authorities in La Paz and Madre de Dios refrained from participating in the national efforts to change the law. In rural La Paz, local authorities often stated that they were going to respect the will of the people. In the words of a local representative, “Our decisions as authorities cannot hurt our people, the local economy and the people who work hard to provide for their families” (Interview, La Paz, October 6, 2017). In the successive roundtables organized by the central state to reform the law in Bolivia, local authorities of mining towns remained silent, signaling their support for mining federations. “It was not going to be a legitimate document without their [local officials’] participation, so we encouraged them to talk but we had no success,” said Héctor Córdova, vice minister of the Productive Development Ministry at the time and a member of the committee in charge of drafting the law (Interview, La Paz, September 29, 2017). The absence of cooperation and the multiple protests of the mining federations constituted an obstacle to the drafting process.

Similarly, the Nationalist Party in Peru had a commitment to poor and informal sectors and won in almost all rural areas, including Madre de Dios and other mining areas. However, in the runoff, soon-to-be-president Ollanta Humala was compelled by elites to sign a “roadmap” to moderate his promises in favor of large-scale investment. Once he was in office, the pressure continued, and elites (predominantly from the large-scale mining sector) and environmentalist groups demanded that Humala take a heavy-handed (mano dura) approach against informality. In 2011, the government began its actions to limit informal mining expansion. Humala’s administration looked to enforce the mining legislation (Decree of Urgency 012-2010, Supreme Decree 029-2011) passed by the previous government of Alan García at the end of his term. Humala also passed new supreme decrees (003 and 004-2012) and legislative decrees authorizing police interventions to confiscate mining instruments in mining towns.

Likewise, the threat of interdictions and the destruction of mining camps activated the formation and strengthening of informal mining associations in Madre de Dios and other regions in Peru, such as the Mining Federation of Madre de Dios (FEDEMIN), the Nacional Confederation of Artisanal and Small Miners (CONAMI), the National Federation of Artisanal Miners in Peru (FENAMARPE), and the National Society of Small-scale Mining (SONA-MIPE). These organizations—led by miners from Madre de Dios—organized regional and national mobilizations from 2010 on (PRONATURALEZA and SER 2011). In 2011, Madre de Dios had several strikes, lasting up to 14 days (El Comercio 2014). The presence of miners’ families and dependents showed Peruvians for the first time how widespread the activity was. Moreover, the shutdown of local businesses in solidarity with the strikers’ cause demonstrated the degree of local support that informal mining had gained over the years.

To the question of what local authorities did about the implementation of national decrees, a Peruvian miner said, “They did the best they could do to support us: they did nothing” (Interview, Huepetuhe, June 3, 2015). In Madre de Dios, regional authorities were also reluctant to collaborate on implementing the decrees. They joined the roundtables led by the central state to create regional monitoring committees and followed the instructions from the central state to pass bylaws for the creation of a Regional Environmental Commission to monitor informal mining activities (Regional Bylaw 011-2010). However, in practice, they refrained from taking action to stop informal mining activities. “For one thing, we did not have the resources to fight against miners … also, would you do that to your own people? To their own businesses? What will you feed them later on?” argued a local authority who participated in the roundtables (Interview, Puerto Maldonado, July 8, 2015). Local officials’ lack of cooperation, as well as massive protests, delayed the execution of the decrees twice, in April 2010 and February 2011 (PRONATURALEZA and SER 2011).

MOBILIZING SUPPORT FROM STATE OFFICIALS

Mobilizations and local authorities’ forbearance were useful to delay the drafting and implementation of decrees, but insufficient to fully guarantee the continuity of informal mining activities. As miners felt the threat was latent, they requested public endorsement from supportive officials as a form of binding commitment. Given the overlapping interests—and often identities—between miners and local elected representatives, getting their support beyond forbearance was far from challenging. Miners were able to gain access—directly or indirectly—to policymaking or implementation strategies, thus projecting their power beyond regional politics and directly contesting the central state’s authority. At this stage, the trajectories of the cases bifurcate. Miners’ political action varied according to their political status and the forms of representation available to them.

Miners in Bolivia contacted former peers working as officials in the MAS government and other local-level unionists who worked as state officials to defend their interests when discussing the new law. FENCOMIN met with two different ministers of mines, first Luis Alberto Echazú and later José Pimentel, both miners and unionists. This led to the organization of roundtables with the participation of mining federations to discuss the reform.

We were there [at the negotiation table] and it was supposed to be a place where each of us had only one representative, but the cooperativists seemed to have their leaders, local authorities, and state members on their side! I really could not tell if they [the authorities] were defending the state or whom. (Interview with a representative of the medium- and large-scale mining sector, La Paz, November 1, 2017)

The overrepresentation and support of mining cooperatives was so evident that other groups invited to the roundtables, such as the Unified Syndical Confederation of Rural Workers of Bolivia (CSUTCB), abandoned the meetings early, feeling ignored. Leaders of indigenous groups also left the room, as they thought only one group was dominating the conversation (Interview with representative present at the law drafting, La Paz, November 2, 2017). The level of support of the mining cooperatives at the roundtables and the ambiguity of the local authorities’ position indicated the contradictory interests of different state branches on informal mining.

The drafts written by the two ministers considerably favored cooperatives’ interests. They reduced bureaucratic procedures to register cooperatives and conveniently omitted monitoring policies to regulate mining activities and labor regimes. However, miners still opposed the drafts in 2010, as the documents signaled limitations to the permitted mining working areas and contract arrangements (Okada Reference Okada2016). Miners organized more strikes to demand the resignation of the two ministers. The contention further delayed the new drafting process. FENCOMIN and local officials publicly accused MAS and President Morales of unwillingness to negotiate with the cooperativist sector, further challenging the legitimacy of the process (La Patria 2011a). The dismissal of the drafts made clear that miners did not want to be only spectators but active participants in the making of the new rules.

In Peru, miners began pressuring local and regional officials in Madre de Dios to publicly endorse their cause. Though with less power than national-level authorities, the association between state institutional “latent” capacities and the power of miners’ social mobilization became highly functional for the miners’ interests.Footnote 4 Each attempt to implement the decrees limiting informal mining areas was followed by massive mobilizations; the most radical one in 2012 lasted 23 days (El Comercio 2014). Mayors from mining towns and district and regional governors at the time— first Gilbert Galindo and then Jorge Aldazábal—joined the protests and cosigned a document outlining miners’ demands to the state. Additionally, most of local authorities boycotted the initiatives coming from the executive. Peruvian newspapers summarized the political scenario:

Double-crossing. While president Ollanta Humala stated that his government was going to have a firm attitude against illegal mining … his regional governor in Madre de Dios, Gilbert Galindo Maytahuari granted permits and authorizations to the fuel carriers that were heading to the gold extraction areas … CHALLENGING THE STATE … representatives from the National Supervisory Board for Investment in Energy and Mining received a document from the Regional Governor stating that he would continue granting those permits, despite the control imposed by the Central state to stop illegal and informal mining. (Peru21 2012)

Aside from forbearing on miners, local authorities also maintained contact with central state authorities and acted as informal spokespeople for the miners. They attempted to enlighten the central state on the contribution of the miners to the local economy. They likewise denounced problems in the formalization law that impeded meeting the requirements, such as the lack of distinction among productive units, the arbitrary selection of mining areas to confiscate machinery, and the high bureaucratic costs of formalization (Interview with leader of SONAMIPE, Lima, November 12, 2015). Additionally, local officials were in charge of voicing the ineffectiveness of the central state’s strategy to achieve formalization. Until that point, less than 1 percent of the miners had formalized their activities (El Comercio 2014).

A High Commissioner for the Formalization, Interdiction and Environmental Remedy of Illegal Miners … visited Madre de Dios at the request of the regional governor, Jorge Aldazábal, to see in situ the problems of mining. “We know that there are a lot of Peruvians working there [in mining] because they have necessities, we cannot use only the instrument of interdictions with coercion, but we also need to generate the development of other activities,” stated the regional governor. (Actualidad Ambiental 2013)

“What happened weeks ago [the interdictions] should never happen again,” stated Jorge Aldazábal, regional president of Madre de Dios in a meeting with 5,000 artisanal miners. Aldazábal indicated that they will ask the Executive to give regional governments the power to lead a new formalization process “only in this way we can move forward with the current laws, miners cannot formalize.” (Inforegión 2013)

Contention both from inside the state and from civil society was successful: the central state extended the deadlines to complete the formalization process several times. Also, the Ministry of Mines developed new guidelines for resource management and monitoring informal mining. More important, for the first time, the central state decided to sit down with the mining associations to discuss the law (Red Muqui 2013).

DIRECT NEGOTIATION WITH THE CENTRAL STATE AND POLICYMAKING INPUT

The capacity to oppose and dismiss law reforms, to point at state mistakes, and to stop the execution of decrees, with great support from the local populations and authorities, gave miners momentum. Every time the government in Bolivia had to postpone the presentation of the law draft to the Assembly, or every time the government in Peru had to extend the deadline to complete the process of formalization due to the lack of stakeholder participation, it signaled a victory for the informal pressure group over the central state. The exposure of the fragmentation of the state increased the burden for the executive to meet and negotiate directly with the pressure group. The miners used this, in turn, to compel the central state to compromise and to legally incorporate part of the miners’ agenda.

In Bolivia, given that miners refused to work with the Ministry of Mines, the government appointed the minister of labor, Félix Rojas, to be in charge of drafting the law (La Patria 2011b). New committees were created in 2011 and 2012 where miners, now without middlemen, negotiated every clause in the working document. Miners changed from acting informal veto players to editors of the law themselves (Okada Reference Okada2016). In 2013, miners obtained a favorable distribution of concessions; the creation of a new institution to regulate such distribution, the Jurisdictional Mining Administrative Authority (AJAM); and more land available to mining cooperatives, among other successes. The share of mining revenues assigned to the mining municipalities increased (Página Siete 2014a). Furthermore, the government committed to increasing the budget of the Fund to Finance Mining (FOFIM) to aid miners with credit and training. Additional regulations were valid only for new miners. FENCOMIN later negotiated the taxation regime to 1 percent (Francescone and Díaz 2012).

Following the revisions by the Ministry of Mines and the Assembly, some changes applied to the negotiated law draft, particularly with regard to the taxation regimen, environmental regulation, and the restriction on cooperatives—which by definition are nonprofit—from contracting with private actors (La Razón 2014). Facing the risk of changes, miners decided to strike and threatened to end their support of MAS. Media editorials at the time spoke about the state’s weakness and inability to set strong rules and assert its autonomy from cooperativist interests (Página Siete 2014b). In response, President Morales promised to speed up the process of making land available for mining cooperatives as an incentive for them to reenter the negotiations. This concession did not stop the protests, however. In one of the strikes, two miners died in Sayari, Cochabamba. The magnitude of the problem prompted the president to intervene once again. FENCOMIN negotiated directly with President Morales and everything the federation asked was agreed on, except the right to partner with private actors. The new mining law, co-edited by the miners, passed on May 28, 2014 (La Razón 2014).

In Peru, miners won local and regional electoral offices, the most important one being the regional government of Madre de Dios with Luis Otsuka, head of the local mining federation, FEDEMIN. By running for office, miners had direct access to negotiations with national authorities, including the president, without middlemen. Otsuka’s role was to push for alternative strategies of regulation. He publicly denounced the failure of the formalization process and its punitive measures. Interdictions were costly (USD$300,000 on average), did not encourage formalization, and worse, led to the clandestine proliferation of illegal gold mines. Otsuka asked for the derogation of the punitive decrees. He insisted on making the distinction between informal miners (those working without permits or in the process of legalizing their activities) from illegal miners (those who work in forbidden areas) and demanded that regional political powers autonomously regulate informal mining (Ojo Público 2016).Footnote 5

Not only did he boycott mining formalization as a leader, but he has now the power as an authority to speak in front of us and question state’s policies. He should make explicit who it is that he is defending, the state or them [the miners]. (Interview with an official from the Ministry of the Environment on Otsuka’s behavior, Lima, July 8, 2015)

After Otsuka, all the candidates and elected officials in the region of Madre de Dios were directly or indirectly participating in informal gold mining (Ojo Público 2018). Facing this informal mining bulwark, the Peruvian government created a high commission for mining formalization, and once again, tried to organize regional committees for mining control, without significant results. Unlike Bolivia, where the ruling party, MAS, had institutional channels of communication with societal groups, in Peru the absence of these channels impeded the development of peaceful negotiations. Thus, in an episode that evidenced the state’s impotence, the government resorted again to interdictions (Decree 003-2014). In response, more than twenty thousand miners went on strike in five regions, and four thousand went to Congress in Lima asking for the derogation of the laws (El Comercio 2014).

Cornered by the miners and facing the pressure of public opinion that spoke about desgobierno (misrule), the government was forced to make changes. The Ministry of Mines changed its technical team and committed to reducing the number of steps in the formalization process. But this was not enough to appease contention. After 2015, the Ministry of Mines decided to meet with the mining federations, and all of the most important presidential candidates in the 2016 elections publicly supported the derogation of the entire formalization law to facilitate a new reform. After that, the legislature, in collaboration with the executive, passed Decree 1293 to restructure the process of formalization and delegate part of the responsibilities to regional offices.

Subsequent teams from the Ministry of Mines have worked toward designing friendlier strategies to formalize miners. They now engage with informal mining leaders in consultation processes when designing policies. Although there have been a couple of interdictions in the last couple of years, these are no longer the primary instrument used by the state to deal with informal mining. Moreover, policymakers stopped labeling all informal mining illegal. The state’s focus has now shifted toward incentivizing the creation of business associations among miners (Peru21 2018).

CONCLUSIONS

This study has shown that informal groups are able to influence policy outcomes, even in cases in which the resource at stake is crucial for the economy of the country, as mining is for Andean states. Although one could anticipate that groups with political representation could include their input in policies, as miners in Bolivia can, the same is true for cases in which informal groups have not been politically incorporated, as with informal gold miners in Peru. I have argued that in both cases the ample maneuvering space that informal groups hold in Bolivia and Peru is a direct consequence of the lack of coordination between the central state and its peripheral branches. State fracture has allowed miners to form pressure groups, in partnership with local elected officials, that challenge the central state’s authority on resource governance.

The cases studied open up a vast research agenda that touches on crucial topics for developing and highly inequal societies. First and foremost, the topic provides us with new evidence to assess different patterns of state-society relations, and at the same time, new resource-related conflict dynamics in Latin America. Although undertheorized, the peripheral state is, in several cases, pitted against the central state to defend alternative forms of resource administration developed in the absence of institutional support.

Elsewhere, I have described how Colombia’s coercion-intensive mining approach, similar to Peru’s, has also fostered alliances with local authorities and organized bottom-up contestation (Toledo Orozco Reference Toledo Orozco and Ellner2020). A future line of research might investigate, in comparative perspective, how national-level representation shapes the contestation strategies of gold miners in Brazil, Ecuador, Venezuela, and Mexico. Likewise, outside of mining, the partnership between informal groups and officials against the central state’s regulations is common currency in places such as Bolivia (Hummel Reference Hummel2018), India (Gupta Reference Gupta1995), and Zambia (Resnick Reference Resnick2013). Systematic work to map these groups’ repertoires of strategies is also needed to advance our knowledge of state-society relations in fragmented states.

A second research topic is that the case of informal miners adds to a growing literature on institutional weakness as an outcome of societal pressure (Soifer Reference Soifer2015; Holland Reference Holland2017; Amengual and Dargent 2020) by elaborating on the implications of subnational state-society dynamics. The support of local elected officials for informal groups’ agendas instead of the state’s exposes the conflict of loyalties between central and peripheral state institutions. This exposure, on the one hand, legitimizes the demands of the informal actors, and on the other hand, helps to consolidate a model of institutional feebleness. Where formal institutions are constantly defeated or exposed as weak, actors develop expectations of instability (Przeworski Reference Przeworski1991). In that sense, the success of informal groups in shaping policy outcomes confirms to other “forsaken” groups that it is worth investing in mobilization and the continuity of pressure groups to destabilize incoherent institutional structures and get the central state’s attention. This is a self-reinforcing model. Actors are also aware that the arrangements obtained are vulnerable to changes by the executive or external pressures. This is why, in Bolivia and Peru, miners have kept their local state alliances and activism during the successive governments of Jeanine Áñez and Martín Vizcarra.

Third, and related to the previous point, my findings have implications for

decentralization and democracy in developing societies. Institutional reforms and political arrangements need to be accompanied by a change in intergovernmental relations. When state institutions remain unarticulated throughout the territory they govern, the new subnational positions of power serve as incentives for the takeover and strengthening of state competitors. State institutions become the catalyst for resistance and contestation against centralized models of governance. The problem is aggravated in cases in which there is strong economic dependence on one commodity, as illustrated in the case of gold in the Andes but also in Southeast Asia (Verbrugge Reference Verbrugge2015; Peluso Reference Peluso2017), and other commodities, such as coca leaf (Farthing and Kohl Reference Farthing and Kohl2010).

While informal groups’ organizations posit a governance challenge, evidence suggests that the inclusion of those directly affected by policies and the strengthening of intergovernmental relations can improve policy outcomes (Ostrom Reference Ostrom1990). Informal actors can provide an everyday perspective based on their experience and can shed light on problems that technocrats alone might not be able to see, as shown in the Peruvian case. Policy innovations in Latin America that follow this principle have proven conducive to better results and deeper democracy (Van Cott 2008). Moreover, inclusion can favor self-regulation, increase transparency in the supply chain, eliminate speculators, combat criminal forces involved, and strengthen rule compliance.