Worldwide, 10 % of the population over 25 years of age suffers from type 2 diabetes( 1 ). Considering that type 2 diabetes is an important cause of mortality, morbidity and lower quality of life, and it negatively affects health-care system and social costs, strategies to prevent this disease are urgently needed( 2 – Reference Wandell 4 ). Such strategies need to be implemented early in life, since the risk factors for type 2 diabetes (e.g. unhealthy lifestyle, overweight/obesity, etc.) are developed in childhood and track into adulthood, thus increasing the risk for this disease prospectively( Reference Baird, Jacob and Barker 5 ).

There is a disproportionately higher prevalence of type 2 diabetes and its risk factors among certain vulnerable population groups. Low socio-economic status has been associated with higher prevalence of type 2 diabetes, overweight/obesity and unhealthy energy balance-related behaviours (EBRB)( 6 – Reference Weinstein, Sesso and Lee 12 ). In particular, 80 % of deaths from non-communicable diseases, including type 2 diabetes, occur in low- and middle-income countries( 13 ), whereas in high-income countries low education level and high percentage of unemployment have been associated with a 45 and 31 % increased risk of type 2 diabetes, respectively( Reference Agardh, Allebeck and Hallqvist 14 ). Given the variation in the prevalence of type 2 diabetes mentioned above, a large segment of the population in low- and middle-income countries as well as certain ethnic groups, immigrants and low socio-economic groups in high-income countries could be at higher risk for developing type 2 diabetes; any initiative should therefore focus primarily on those population groups.

Modifiable risk factors related to type 2 diabetes include overweight/obesity and physical inactivity, high levels of sedentary behaviour and unhealthy dietary habits( 6 – Reference Weinstein, Sesso and Lee 12 ). The family environment, the community and the school environment play an important role in the determination of family lifestyle habits and health indices. Family members have a common genetic background, but also share a common environment, attitudes and beliefs regarding health issues, with older family members serving as children’s role models too( Reference Dwyer, Higgs and Hardy 15 , Reference Sarti 16 ). Furthermore, the community environment may be either a facilitator or a barrier with respect to a healthy lifestyle. Road and personal insecurity, limited access to community facilities (e.g. sports halls, parks, pedestrian areas), lower social support and community resources lead to poor adherence to dietary and physical activity recommendations( Reference Brown, Ettner and Piette 17 – Reference Taylor, Cottrell and Chatterton 20 ). School environment, as an integral part of the community, can influence children’s and families’ health-related behaviours via healthy food availability, physical education, class curricula or health education programmes( Reference Foster, Linder and Baranowski 21 ).

The effectiveness of any school-based initiative is greater when combined with the active involvement of the family and the community, given the strong interaction among child, family, school and neighbourhood environment( Reference Gonzalez-Suarez, Grimmer-Somers and Dones 22 , Reference Saraf, Nongkynrih and Pandav 23 ). Although previous studies have highlighted that type 2 diabetes can be prevented via lifestyle changes achieved through counselling sessions with high-risk subjects, there is limited evidence about the effects of a school- and community- based intervention and lifestyle counselling for the prevention of this disease( Reference Tuomilehto, Lindström and Eriksson 24 ).

The EU-funded Feel4Diabetes-study focused on the development, implementation and evaluation of a school- and community-based intervention to prevent type 2 diabetes in vulnerable families across Europe. The Feel4Diabetes-intervention promoted healthy eating and active lifestyle through the provision of a more supportive social and physical environment at home, school and municipality level, as well as lifestyle counselling to the parents with increased type 2 diabetes risk. The aim of the current paper is to describe the design of the Feel4Diabetes-intervention and provide some preliminary data on the recruited cohorts.

Methods

Feel4Diabetes-study background

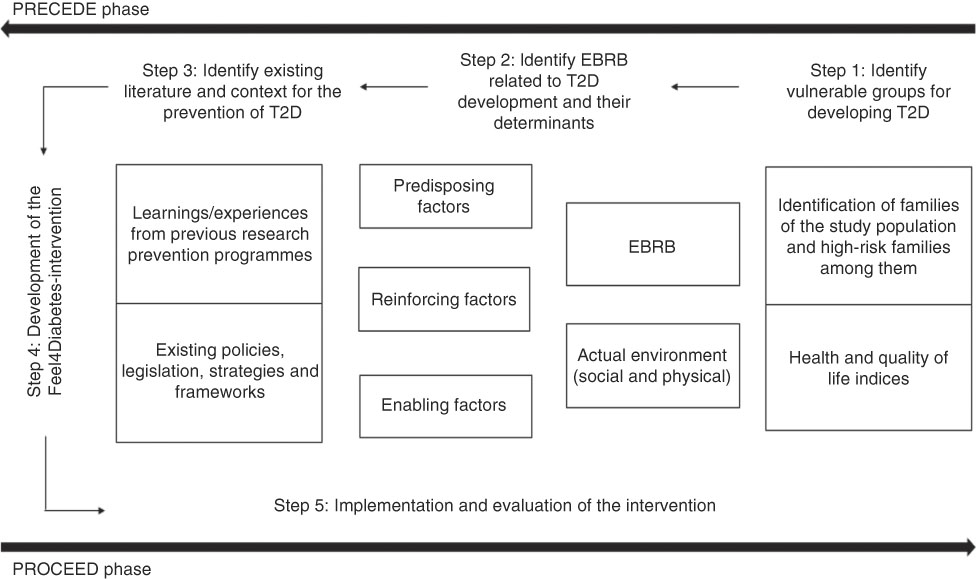

To develop, implement and evaluate the Feel4Diabetes-intervention, the Feel4Diabetes-study followed a theoretical framework based on the PRECEDE–PROCEED model (Fig. 1)( Reference Green and Kreuter 25 ).

Fig. 1 The contextual framework of the Feel4Diabetes-study (T2D, type 2 diabetes; EBRB, energy balance-related behaviour)

PRECEDE phase

Within this preparatory phase the following sub-studies were conducted:

1. Systematic literature review to identify the target population (i.e. the groups that are vulnerable regarding type 2 diabetes development).

2. Systematic literature review to identify the most important EBRB and sub-behaviours related to the risk factors for developing type 2 diabetes in vulnerable groups. Moreover, focus groups with parents and grandparents (at high risk and low risk for type 2 diabetes), as well as teachers and health-care professionals, were conducted to identify the relevant predisposing, reinforcing and enabling factors.

3. Systematic narrative literature reviews: (i) to identify research programmes that have been implemented in the school setting and focused on the promotion of healthy eating and physical activity, with emphasis on socio-economic position and vulnerable groups; and (ii) to summarize lifestyle intervention theories, methods, modes and targets that have been successfully applied in earlier diabetes prevention studies, with special emphasis on vulnerable population groups. Furthermore, survey (‘European Diabetes Survey’) and systematic comparative analysis to identify the existing policies, legislation, strategies and frameworks related to type 2 diabetes prevention that are available in the six countries participating in the Feel4Diabetes-intervention.

PROCEED phase

This phase included the following steps:

4. The insights gained in the PRECEDE phase (i.e. from the literature reviews, the focus groups and the survey and systematic comparative analysis) and the ‘Health Action Process Approach’ (HAPA) were used to develop and implement the Feel4Diabetes-intervention, while key learnings and expertise from previous European and national projects have been also incorporated( Reference Schwarzer 26 ).

5. The Feel4Diabetes-intervention will be evaluated regarding its process, impact and outcome, based on measurable objectives. Its cost-effectiveness and scalability will be also evaluated( Reference Annemans 27 , Reference Milat, King and Bauman 28 ).

Design of the Feel4Diabetes-intervention

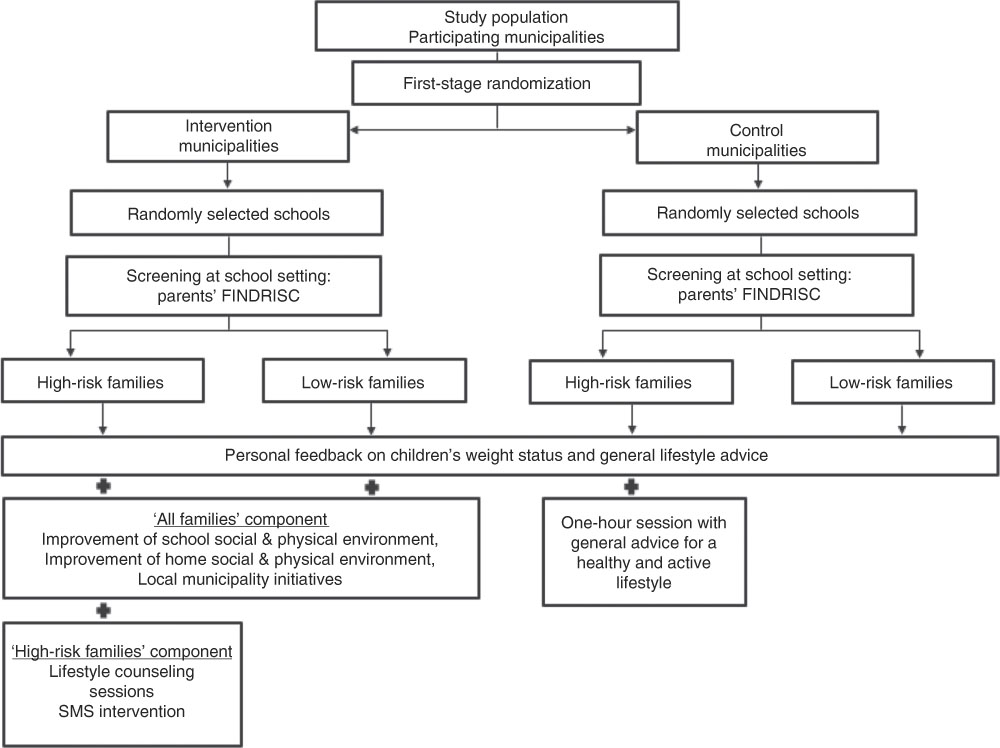

The Feel4Diabetes-intervention was registered at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ (registration number: NCT02393872). It had a cluster-randomized design and consisted of two components: (i) the ‘all families’ component, which was delivered at schools, home and the local municipalities; and (ii) the ‘high-risk families’ component, which was delivered out of the school setting, in families found to be at increased risk for type 2 diabetes (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Overview of the Feel4Diabetes-intervention (FINDRISC, Finnish Diabetes Risk Score; SMS, text messaging)

The development of both components was guided by the outcomes of the earlier phases of the Feel4Diabetes-study. Specifically, the behaviours which were found to be associated with risk for developing type 2 diabetes were targeted in the Feel4Diabetes-intervention. Moreover, the identified barriers and facilitators of these behaviours were targeted, while information about existing legislation and policies, available human resources and infrastructure for both implementing the intervention as well as providing easy access to facilities for leisure-time physical activity, active commuting, etc. was considered when developing the intervention.

Newly identified individuals with diabetes were directed to the local health-care system for further evaluation and treatment, but they could join their families in the intervention, if they wished so.

The ‘all families’ component

The ‘all families’ component was delivered by the school teachers. It focused on changes in the school, home and local municipality social and physical environment to assist the family to reach the recommendations for a healthy and active lifestyle. The goals of the ‘all families’ intervention, as identified in the PRECEDE phase, were the following: increase water consumption (instead of sugary drinks); increase consumption of fruits and vegetables; consumption of healthy and balanced breakfast and/or morning snack; increase physical activity; and decrease/interruption of prolonged sedentary time.

The teachers participated in one training session at the beginning of every school year, during which the intervention material was presented and information on how to implement the intervention was provided. Teachers’ training was conducted based on a standardized protocol and training module across all centres. For those teachers who were not able to participate in the training sessions, the materials were delivered, and additional training visits to schools were arranged. To avoid contamination between the intervention and control groups, no access to the material or training was provided to the control group and control schools were asked to continue with the standard curriculum.

At school level, trained teachers aimed to create a more supportive social and physical environment promoting a healthy and active lifestyle for the children during school hours, such as providing opportunities and acting as role models for healthy behaviours. The activities at school were complemented with simple and easy-to-read newsletters, aiming to inform and actively engage the families in the intervention. The newsletters were culturally adapted and aimed to motivate, improve self-efficacy to apply environmental changes at home, and provide practical tips to adopt a healthier and more active lifestyle.

At local municipality level, available infrastructure and human resources to support the lifestyle and behavioural changes of the families were identified and promoted. For example, access to sports halls and parks or school-setting playgrounds after school hours or active commuting, etc. These opportunities for increasing families’ healthy and active lifestyle were identified by the local research groups in collaboration with the local municipality authorities and then communicated to the parents via newsletters distributed to them by the teachers and other means of communication.

The ‘high-risk families’ component

The ‘high-risk families’ component was delivered by trained health professionals. It was implemented in addition to the ‘all families’ component to further support and encourage high-risk families to achieve and adhere to the recommendations for a healthy and active lifestyle. The specific additional intervention targets, as identified in the PRECEDE phase, were: increase intakes of whole grains, nuts, low-fat dairy, and olive or rapeseed oil; decrease intakes of sweet and savoury snacks and fast foods, red and processed meat; reduce body weight by 5% (if overweight); and family meal at least once per day.

The adult members of the ‘high-risk families’ were invited to the local community centre (e.g. university, health promotion centre or any other available community centre) within the municipality to undergo a more detailed assessment. The ‘high-risk families’ component included seven lifestyle counselling sessions spread over the academic year 2016–2017, including two sessions delivered separately to each ‘high-risk’ family (‘family sessions’) and five group sessions (Table 1). The first six counselling sessions were completed by March 2017, whereas the seventh counselling session was implemented in September 2017 to provide the results of each family’s first follow-up medical check-up; set specific, measurable, attainable, realistic and timely (SMART) goals for the second year of the intervention; and introduce them to the text-messaging (SMS) intervention (in the case of Finland, all sessions were completed by January 2017). If the participants were not able or willing to physically attend the sessions, they were offered an opportunity for counselling over the telephone or by email. During the second year the participants received motivational guidance via SMS sent to their mobile phones. The counselling sessions included behavioural techniques aiming to increase motivation and self-efficacy of ‘high-risk families’, improve their self-regulation and set SMART goals to reach the targeted lifestyle recommendations. In each of the counselling sessions, the ‘high-risk families’ received material (e.g. newsletters) and activities which were conducted either during the session or at home. The control group for this component received only general advice for a healthy and active lifestyle during a one-hour session.

Table 1 Structure of counselling sessions in the ‘high-risk families’ component: the Feel4Diabetes-intervention

G, group session; F, individual (family) session; T2D, type 2 diabetes; SMART, specific, measurable, attainable, realistic and timely; SMS, text messaging.

* This was not conducted in the case of Finland, since the results of medical check-up were not available for the counsellors due to ethical reasons.

Timeline

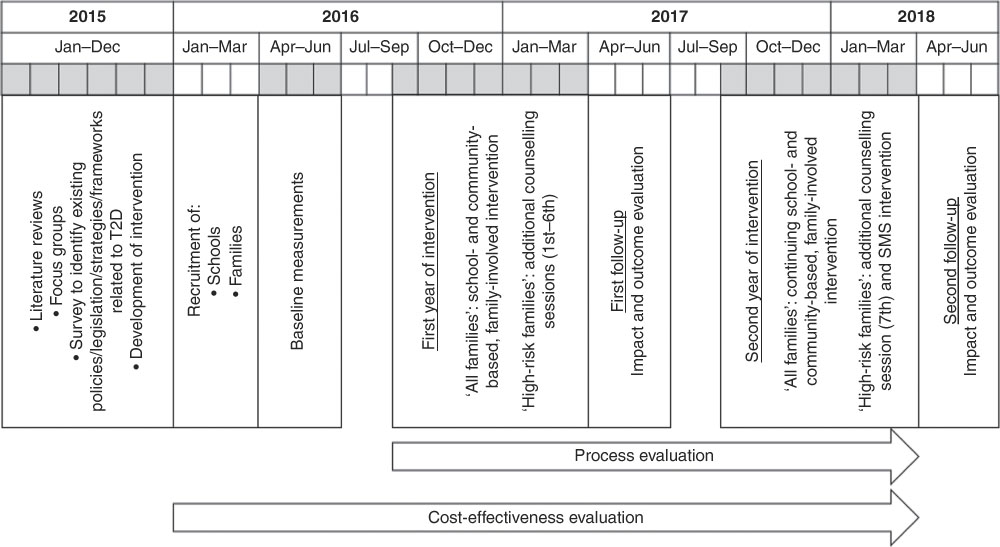

The duration of the Feel4Diabetes-study (i.e. development, implementation and evaluation of the Feel4Diabetes-intervention) was four years (2015–2019). A detailed description of the Feel4Diabetes-study timeline is presented in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3 Timeline of the Feel4Diabetes-study (T2D, type 2 diabetes; SMS, text messaging)

The time plan of the Feel4Diabetes-intervention was designed to account for country-specific differences with respect to the opening and closing dates of schools and the duration and timing of national holidays. Recruitment of children attending the first three grades of primary school and their families (parents and grandparents) started in January 2016; baseline measurements were conducted between April and June 2016 and for three countries (i.e. Finland, Hungary and Bulgaria) were extended during August–September 2016. The intervention was implemented over two school years, i.e. the school years 2016–2017 and 2017–2018. The follow-up 1 and follow-up 2 measurements were performed in the same months as at baseline, in 2017 and 2018, respectively. To account for seasonal variations, follow-up measurements were conducted as close to the date of the baseline measurements as possible. Process evaluation and assessment of cost-effectiveness were conducted during the implementation phase of the intervention.

Ethical approvals and consent forms

The Feel4Diabetes-study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and the conventions of the Council of Europe on human rights and biomedicine. Prior to initiating the intervention, all participating countries obtained ethical clearance from the relevant ethical committees and local authorities. More specifically, in Belgium the study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Ghent University Hospital; in Bulgaria, by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Varna and the Municipalities of Sofia and Varna, as well as the Ministry of Education and Science local representatives; in Finland, by the hospital district of Southwest Finland ethical committee; in Greece, by the Bioethics Committee of Harokopio University and the Greek Ministry of Education; in Hungary, by the National Committee for Scientific Research in Medicine; and in Spain, the study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee and the Department of Consumers’ Health of the Government of Aragón. All parents/caregivers provided a signed consent form before being enrolled in the study.

Recruitment of participants

Recruitment was conducted within the provinces of Oost-Vlaanderen and West-Vlaanderen (Belgium), Varna and Sofia (Bulgaria), Satakunta (Finland), Attica (Greece), Debrecen and its county (Hungary) and Zaragoza (Spain). In Bulgaria and Hungary, all areas within the selected provinces were considered ‘vulnerable’ and eligible to participate in Feel4Diabetes. In Greece, Spain, Finland and Belgium, the municipalities/school districts/other equivalent units in the selected provinces were grouped in tertiles according to socio-economic indices retrieved from official resources and authorities (e.g. in Greece information was retrieved from the Hellenic Statistical Authority) and ‘vulnerable’ areas were randomly selected only from the tertile with the lowest education level or the highest unemployment rate. In the case of Finland, areas were ordered based on the mean values of the selected socio-economic index and ‘vulnerable’ areas were selected from the lower mean.

In all countries, after taking the necessary approval(s) from local authorities (ethical committees, ministries, municipalities, etc.), lists of all primary schools within the randomly selected ‘vulnerable’ areas were created and primary schools were randomly selected and recruited from each area until the recruitment goal was met. Children attending the first three grades of compulsory education and their families (i.e. ‘all families’) were recruited to the study from these primary schools. Of these recruited families, the ‘high-risk families’ were identified based on type 2 diabetes risk estimation using the Finnish Diabetes Risk Score (FINDRISC)( Reference Lindström and Tuomilehto 29 ). To be regarded as a ‘high-risk family’, at least one parent in the family had to fulfil the country-specific cut-off point.

Regarding the ‘all families’ component of the intervention, a sample of 600 ‘all families’ per treatment arm was required to achieve statistical power greater than 80 % (at a two-sided 5 % significance level) for reducing screen time by 0·2 h/d in children within 8 months. Regarding the ‘high-risk families’ component of the intervention, a minimum sample of 150 ‘high-risk families’ per treatment arm was required to achieve statistical power greater than 80 % (at a two-sided 5 % significance level) for reducing BMI by 0·7 kg/m2 in adults within a year. Therefore, a minimum sample of 1200 ‘all families’ and of these 300 ‘high-risk families’ per country, resulting in a total sample of 7200 ‘all families’ and 1440 ‘high-risk families’, was initially targeted. However, to account for an estimated dropout rate of about 20 %, a total number of about 9000 ‘all families’ and 2160 ‘high-risk families’ were aimed to be recruited in the six participating countries.

The randomization to the intervention and control group was conducted at a municipality level (1:1 ratio) after the completion of baseline measurements. Therefore, the schools and the families (i.e. ‘all families’ and ‘high-risk families’) within each municipality were automatically allocated to the intervention or control group.

Measurements

To evaluate the outcome of the Feel4Diabetes-intervention, children’s and adult family members’ (parents’ and/or grandparents’) anthropometric indices, as well as adult family members’ blood indices and blood pressure indices, were measured by rigorously trained research assistants, using standardized protocols and equipment that was calibrated before the start of the measurements (in each time period). Regarding the anthropometric indices, three measurements of children’s weight and height and adults’ weight, height and waist circumference were taken. Participants were asked to remove heavy clothing and stand still in an erect position during the measurements. Portable equipment was used (digital scales for weight; telescopic stadiometers for height; non-elastic waist tape for waist circumference). Regarding the blood indices, blood samples were drawn in the first morning hours after overnight fasting. On the previous day the research assistants reminded the adults via a telephone call to remain fasted until the time of the measurement, to ensure compliance with fasting. The collected blood samples were centrifuged and then analysed in accredited laboratories to obtain measurements of total, HDL and LDL cholesterol, triacylglycerols, glucose and insulin. Regarding blood pressure, three measurements of systolic and diastolic blood pressure were taken with commercially available electronic sphygmomanometers and cuffs appropriate for each participant’s arm size. Participants were asked to sit quietly for at least 5 min before each measurement.

To evaluate the impact of the Feel4Diabetes-intervention, children’s and adults’ behavioural indices on drinking, eating, physical activity and sedentary behaviours, as well as their determinants, were self-reported by the parents via standardized questionnaires and physical activity monitors (either pedometers or accelerometers).

Regarding the process evaluation, the degree and fidelity of implementation of the intervention at schools and counselling sessions were assessed via standardized, self-reported questionnaires, which were completed by the school teachers and the research assistants, respectively. Regarding cost-effectiveness, all costs related to the Feel4Diabetes-intervention were recorded by the research assistants and the teachers. Health economic modelling will be used to estimate the cost-effectiveness of the Feel4Diabetes-intervention.

Moreover, data related to the socio-economic status of the families (e.g. paternal and maternal years of education and age) participating in the Feel4Diabetes-intervention were collected.

Multi-level analyses (four levels: ‘time’, ‘family’, ‘primary school’ and ‘municipality’) will be performed to examine the impact and outcome evaluation of the Feel4Diabetes-intervention, taking clustering of two measurements (baseline and follow-up) of families in primary schools in municipalities into account.

Results

The mean participation rate of ‘all families’ in the total study sample was 43·8 %. In total, 20 442 families were screened with the FINDRISC questionnaire. The study sample at baseline comprised 12 193 ‘all families’ and 2230 ‘high-risk families’, which provided complete data (Table 2). Overall, the Feel4Diabetes-intervention reached 30 309 families via the participating primary schools (i.e. families that received the ‘all families’ intervention component, regardless of whether they participated in the baseline measurements).

Table 2 Number of ‘all families’ (AF) and ‘high-risk families’ (HRF) by country at baseline: the Feel4Diabetes-intervention

Table 3 presents the descriptive characteristics of the ‘all families’ at baseline. In brief, children’s mean age was 8·2 years, with 50·7 % of the sample being females. Regarding the anthropometric data, children’s mean weight and height were 29·84 kg and 130·67 cm, respectively. In the overall sample, 90·4 % of the mothers and 77·6 % of the fathers were younger than 45 years old.

Table 3 Sociodemographic characteristics of ‘all families’ (n 12 193) by country at baseline: the Feel4Diabetes-intervention

P < 0·05 for differences among countries: asignificantly different from the rest of the countries; bsignificantly different from Belgium; csignificantly different from Bulgaria; dsignificantly different from Finland; esignificantly different from Greece; fsignificantly different from Hungary; gsignificantly different from Spain.

Table 4 presents the descriptive characteristics of the ‘high-risk families’ at baseline. In total, data were collected from 3268 parents. Overall, 89·7 % of the ‘high-risk’ adults were Caucasian, 91·5 % were married or cohabiting, 4·8 % were unemployed, 75·9 % were under the age of 45 years and 65·4 % were mothers (female gender).

Table 4 Sociodemographic characteristics of ‘high-risk families’ (n 2230) by country at baseline: the Feel4Diabetes-intervention

Data on parental ethnicity were not available for Finland.

P < 0·05 for differences among countries: asignificantly different from the rest of the countries; bsignificantly different from Belgium; csignificantly different from Bulgaria; dsignificantly different from Finland; esignificantly different from Greece; fsignificantly different from Hungary; gsignificantly different from Spain.

Discussion

The Feel4Diabetes-study aimed to develop a school- and community-based intervention to promote healthy lifestyle and tackle obesity and obesity-related metabolic risk factors for the prevention of type 2 diabetes among families in low/middle-income countries and in vulnerable groups in high-income countries and countries under austerity measures in Europe. Previous studies have shown that lifestyle intervention may be an effective approach to tackle the rising prevalence of type 2 diabetes( 30 , Reference Lindstrom, Peltonen and Eriksson 31 ).

The development, implementation and evaluation of the Feel4Diabetes-intervention was based on a systematic approach lasting four years. More specifically, the EBRB/sub-behaviours that were found in the early phases of the study to be associated with risk factors for developing type 2 diabetes, as well as their determinants, were targeted in the Feel4Diabetes-intervention. Moreover, learnings and experiences from previous interventions, as mapped through literature reviews conducted within the Feel4Diabetes-study, provided the basis for developing the Feel4Diabetes-intervention. Furthermore, schools, community infrastructure and health-care personnel which were available in the intervention areas were mapped in the six countries participating in the Feel4Diabetes-intervention. In parallel, the active involvement and engagement of the relevant stakeholders, including decision and policy makers, within the community was pursued from the beginning of the Feel4Diabetes-intervention. The synthesis of the evidence and lessons obtained during the PRECEDE phase of the project were compiled into practical directions which were used for the development and implementation of the Feel4Diabetes-intervention, using a behavioural approach (HAPA) that has been used in previous lifestyle interventions aiming to prevent type 2 diabetes( Reference Heideman, Nierkens and Stronks 32 , Reference Uutela, Absetz and Nissinen 33 ).

The recruitment of participants in Feel4Diabetes was based on a standardized, multistage sampling procedure, to ensure sufficient representativeness of vulnerable groups for developing type 2 diabetes in the participating regions in the six European countries. Moreover, using municipalities, school districts or other equivalent units as the cluster unit limited contamination among neighbouring schools and volunteers, and allowed the Feel4Diabetes-intervention to control for diversities among families’/children’s physical environment in the neighbourhood (e.g. playgrounds, restaurants) that may influence their lifestyle habits. On the other hand, the intervention was implemented at a school level, with the participation of the whole class, aiming to increase acceptability and avoid stigmatization since everyone received the same treatment, as well as to maximize universalization by reducing participant self-selection. Still, considering that not all families of the study population had a risk for type 2 diabetes of equal magnitude and since school-based interventions targeting the overall population cannot and should not target those high-risk families to avoid stigmatization, Feel4Diabetes implemented a screening procedure to identify these families and delivered an additional family intervention component out of school hours. This screening was based on a previously developed and validated tool to assess future diabetes risk, i.e. the FINDRISC, which has been used in several studies in this field( Reference Lindström and Tuomilehto 29 , Reference Lindstrom, Peltonen and Eriksson 31 ).

Across the Feel4Diabetes-intervention countries, standardized, country-adapted protocols, methods, tools and materials were used for the implementation of the intervention, as well as for the process, impact, outcome evaluation and the assessment of its cost-effectiveness, in line with other previous multicentre studies( Reference Androutsos, Katsarou and Payr 34 – Reference Pigeot, Baranowski and De Henauw 36 ). Regarding the implementation of the intervention, all study centres used common, country-adjusted protocols and manuals (i.e. for the school component: handbook for the teachers, newsletters for the parents and slides for teachers’ training; for the ‘high-risk families’ component: manual for the health-care professionals, slides, newsletters/activities/material for the counselling sessions and SMS intervention). Moreover, all researchers who trained the teachers and all health-care professionals who delivered the ‘high-risk families’ component (counselling sessions and SMS intervention) were trained centrally before the implementation of the intervention. The results of the Feel4Diabetes-intervention will be evaluated by assessing its process, impact, outcome and cost-effectiveness.

The Feel4Diabetes-intervention has certain strengths and limitations. First, experiences and learnings from previous programmes guided the development of the Feel4Diabetes-intervention. An additional strength is that the Feel4Diabetes-intervention did not follow a ‘one size fits all’ approach; rather, from a preselected list of targeted EBRB identified from the literature, the participating countries, schools and families could choose and prioritize the most relevant and appealing EBRB to them via the SMART goals approach. Furthermore, the intervention messages were tailored according to each country’s needs and reality. For example, in the ‘all families’ component, teachers were asked to prioritize the EBRB that were more relevant to their school and class needs, in case they could not focus on all EBRB at the same time, to increase compliance with the intervention. Similarly, in the ‘high-risk families’ component, the advice to the ‘high-risk families’ (in the counselling sessions and/or in the SMS intervention) for increasing their physical activity, which was an EBRB promoted in all centres, could be to walk in the forest in Finland or to visit the schoolyard which was open in the afternoon in Greece. Moreover, in line with the study of Endevelt et al., a mixture of individual and group sessions was used in the ‘high-risk families’ component aiming to increase effectiveness and cost-effectiveness( Reference Endevelt, Peled and Azrad 37 ). Regarding the evaluation of the intervention, the large study sample, the standardized protocols and procedures followed across all centres, and the objectively collected data (i.e. blood and anthropometric indices, blood pressure and physical activity level recorded via pedometers/accelerometers) safeguard the more objective and reliable assessment and increase the generalizability of findings. On the other hand, part of the collected data is self-reported and thus prone to recall bias and social desirability.

The Feel4Diabetes-study has developed a multicomponent, school- and community-based intervention for improved lifestyle and the prevention of type 2 diabetes. More than 12 000 primary-school children and their families, including more than 2000 families at high risk for developing type 2 diabetes, from six European countries, participated in the Feel4Diabetes-intervention at baseline. The impact, outcome, process evaluation and cost-effectiveness of the Feel4Diabetes-intervention will be assessed to guide the design and scaling-up of affordable and potentially cost-effective population-based interventions for the prevention of type 2 diabetes.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank the members of the Feel4Diabetes-study Group. Financial support: The Feel4Diabetes-study has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement number 643708). The content of this article reflects only the authors’ views and the European Community is not liable for any use that may be made of the information contained herein. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: All authors participated in the conception and design of the study, contributed to writing and revising the manuscript, and approved the final version. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the ethics committees in all countries (in Belgium, by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Ghent University Hospital; in Bulgaria, by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Varna; in Finland, by the hospital district of Southwest Finland ethical committee; in Greece, by the Bioethics Committee of Harokopio University; in Hungary, by the National Committee for Scientific Research in Medicine; in Spain, by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Members of the Feel4Diabetes-study Group are as follows. Coordinator: Yannis Manios. Project Manager: Odysseas Androutsos. Steering Committee: Yannis Manios, Greet Cardon, Jaana Lindström, Peter Schwarz, Konstantinos Makrilakis, Lieven Annemans, Maria Stella de Sabata. Harokopio University (Greece): Yannis Manios, Meropi Kontogianni, Odysseas Androutsos, George Moschonis, Konstantina Tsoutsoulopoulou, Christina Mavrogianni, Christina Katsarou, Eva Karaglani, Eirini Efstathopoulou, Ioanna Kechribari, Konstantina Maragkopoulou, Effie Argyri, Athanasios Douligeris, Mary Nikolaou, Eleni-Anna Vampouli, Katerina Kouroupaki, Roula Koutsi, Elina Tzormpatzaki, Eirini Manou, Panagiota Mpinou, Alexandra Karachaliou, Christina Filippou, Amalia Filippou. National Institute for Health and Welfare (Finland): Jaana Lindström, Tiina Laatikainen, Katja Wikström, Jemina Kivelä, Päivi Valve, Esko Levälahti, Eeva Virtanen. Ghent University (Belgium): Greet Cardon, Julie Latomme, Vicky Van Stappen, Nele Huys (Department of Movement and Sports Sciences); Lieven Annemans, Lore Pil, Ruben Willems (Department of Public Health). Technische Universität Dresden (Germany): Peter Schwarz, Ivonne Panchyrz, Maxi Holland, Patrick Timpel. National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (Greece): Konstantinos Makrilakis, Stavros Liatis, George Dafoulas, Christina-Paulina Lambrinou, Angeliki Giannopoulou, Lydia Tsirigoti, Evi Fappa, Costas Anastasiou, Konstantina Zachari. International Diabetes Federation Europe (Belgium): Niti Pall, Maria Stella de Sabata, Lala Rabemananjara, Winne Ko. Universidad de Zaragoza (Spain): Luis Moreno, Fernando Civeira, Gloria Bueno, Pilar De Miguel-Etayo, Esther Mª Gonzalez-Gil, Maria I Mesana, Germán Vicente-Rodriguez, Gerardo Rodriguez, Lucia Baila-Rueda, Ana Cenarro, Estíbaliz Jarauta, Rocío Mateo-Gallego. Medical University of Varna (Bulgaria): Violeta Iotova, Tsvetalina Tankova, Natalia Usheva, Kaloyan Tsochev, Nevena Chakarova, Sonya Galcheva, Rumyana Dimova, Yana Bocheva, Zhaneta Radkova, Vanya Marinova. University of Debrecen (Hungary): Imre Rurik, Timea Ungvari, Zoltán Jancsó, Anna Nánási, László Kolozsvári. Extensive Life Oy (Finland): Remberto Martinez, Marcos Tong, Kaisla Joutsenniemi, Katrina Wendel-Mitoraj.