6.1 Introduction

Danish development cooperation has changed significantly since the 1990s. Both in terms of quantity, character, and organization, Danish foreign aid has been altered so thoroughly that it is difficult to recognize today. Alongside sudden dramatic cuts to aid in other countries,Footnote 1 this demonstrates the peculiar nature of the policy field of development cooperation, whose stakeholders are either absent, as in beneficiaries in countries far away, few as in those earning their living from the “aid industry,” or disinterested, as in voters with only marginal interests in the field. This chapter analyzes the changes that have taken place in Danish aid over the past decades and seeks to provide some explanations of these changes and their drivers.

In the literature, there is a long-standing discussion of how to understand and explain development cooperation. Multi-country economic regressions have been used to determine the motivations behind aid allocations (Maizels and Nissanke Reference Maizels and Nissanke1984; Alesina and Dollar Reference Alesina and Dollar2000; Hoeffler and Outram Reference Hoeffler and Outram2011), and multi-country qualitative studies have sought to establish causal factors and mechanisms explaining the organization of foreign aid (Stokke Reference Stokke and Stokke1989; Lancaster Reference Lancaster2007; van der Veen Reference van der Veen2011; Lundsgaarde Reference Lundsgaarde2013). While the first tend to link development cooperation to foreign policies, the latter have been preoccupied by domestic factors. Moreover, the studies with one notable exception (Lancaster Reference Lancaster2007) tend to focus on a single explanatory variable rather than the interaction of several different factors (Engberg-Pedersen Reference Engberg-Pedersen2016). Our contribution is to emphasize that both domestic and international elements are important for the understanding of changes of development cooperation. We do so by emphasizing the historical development of Danish foreign aid which, although today substantially different from the 1990s, builds on earlier experience and practices (Engberg-Pedersen and Fejerskov Reference Engberg-Pedersen, Fejerskov, Fischer and Mouritzen2018).

Furthermore, this chapter discusses two particular questions raised in this book and relates them to Danish aid, namely Scandinavian exceptionalism and the end of aid. With respect to the first, it is tempting to ask: Is Denmark an exception to Scandinavian exceptionalism? Whereas Sweden has had several powerful idealists and internationalists as leading political figures (Olaf Palme, Dag Hammarskjöld), and Norway has long pursued a role as a peacemaker in conflicts all over the world, the Danish approach has been much more characterized by pragmatism, mercantilism, and subservience to international trends. It appears neither altruistic, idealist, nor driven by exceptional motives of humanitarianism, though it is sometimes presented as such. While aid professionals have sought to put together a professional and responsive development cooperation, politicians have never assigned aid a significant role in Danish foreign policy in ways similar to Sweden and Norway.

On the second question, numerous observers and authors have declared the end of aid (Gill Reference Gill2019), and there are definitely signs of disarray and decay. Danish development cooperation could be seen as an example of that trend, and the global tendencies toward increased nationalism are another indication that the days of international development cooperation may be over. Nevertheless, total Official Development Assistance (ODA) is not decreasing, and most middle-income countries seem to be construing their own development cooperation (see Fejerskov, Lundsgaarde, and Cold-Ravnkilde Reference Fejerskov, Lundsgaarde and Cold-Ravnkilde2017), from Brazil to South Africa to Turkey. Foreign aid thus still widely appears to be perceived as an instrument of influence and cooperation, though it is used for all sorts of purposes, many of whom do not necessarily have development itself or support to poor people as primary objectives. Development cooperation accordingly seems to be in a process of reconceptualization and transformation, away from a focus on poverty reduction and aid effectiveness, rather than experiencing a withering away altogether.

Apart from documenting the changes of Danish development cooperation, this chapter’s main argument is that these changes are the results of interactions between Denmark’s particular history, international changes, and contingent political events. Thus, Danish aid is less a reflection of a political ambition to brand Denmark internationally as a humanitarian frontrunner, and more a by-product of unfolding domestic political priorities influenced by international events and changes. While Danish politicians regularly boast about how the country’s development cooperation comes out at the top of international assessments of foreign aid, this is a concern which is easily trumped by other interests, as we will show. Only during a brief period in the 1990s did developments coalesce so that long-term poverty reduction seemed to be the real, and not only the official, objective.

This chapter is organized as follows. The next part highlights a set of features that have characterized Danish development cooperation since its beginning. In the second and major part, we turn towards the significant changes that have taken place over the last decade, including cutbacks, reorientation, and a general transformation of aid. Here, we focus specifically on five issues and show how changes in each have been driven by contingent events and domestic politics more so than ambitions of Scandinavian exceptionalism or the position as a humanitarian great power. We end by concluding on the nature of the changes taking place over the past decades, and the drivers of those changes.

6.2 Pragmatism vs Political Priorities: Poverty Focus vs Commercial Interests

In its early days, Danish foreign aid focused on project assistance and technology transfer with a large involvement in integrated rural development in Bangladesh in the late 1970s and the early 1980s. In 1978, some years later than Sweden and Norway, Danish aid reached the quantitative target of constituting 0.7 percent of GNI, established by the UN, and in 1985 a majority in parliament decided that Denmark’s development assistance should increase to 1.0 percent of GNI by 1992 where it stayed throughout the 1990s.

Noninterference in political processes in decolonized societies was a significant priority in the first many years of Danish development cooperation (Bach et al. Reference Bach, Olesen, Kaur-Pedersen and Pedersen2008), and a partnership approach has been a major discursive reality in discussions of foreign aid. Pragmatic partnerships were, albeit with different interpretations, important notions all the way up to the adoption of the Paris Declaration in 2005 with its focus on ownership and alignment, and all major strategies have had a separate chapter on how the cooperation should be based on partners’ priorities.

Despite this emphasis on cooperation, political priorities began to be established in the second half of the 1980s. The first general policy drafted by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs was published in 1988 (Danida 1988) identifying six qualitative goals. In 1994, a comprehensive policy, A World in Development, came out making poverty reduction the overall objective, with gender equality, environment, and democratization three cross-cutting concerns (Danida 1994). A number of changes took place during these years. In 1989 it was decided that Danish bilateral aid should be concentrated on twenty so-called co-operation countries. The idea was that Danish aid had little impact because it was too thinly spread. This has had some effects, as foreign aid of most other Western and “like-minded” countries exhibits significantly more proliferation across recipient countries compared to Denmark (Acharya, Fuzzo de Lima, and Moore Reference Acharya, Fuzzo de Lima and Moore2006). Moreover, the 1994 policy announced a change from project aid to sector-wide approaches. Underlying this new orientation were two rationales: firstly, that projects tended to become “development islands” with few sustainable long-term effects and, secondly, that effective sector institutions are crucial conditions for development. Moreover, the change corresponded nicely with the view that sustainable development cannot be created by outsiders. These ideas were repeated six years later in a new general development policy, Partnership 2000 (Danida 2000). Moreover, a significantly strengthened focus on environmental issues emerged in the late 1980s, particularly as a consequence of the UN Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. It was agreed in parliament to create a separate fund for aid to the environment and to catastrophes. The plan was that this fund should grow to 0.5 percent of GNI by 2002 in addition to the ODA now constituting 1.0 percent of GNI.

Thus, the relationship between pragmatic partnerships and political priorities gradually changed around 1990 in favor of the latter without eliminating the former. This change mirrors largely international trends before and after the end of the Cold War. Institutional development, democratization, and macro-economic responsibility were central notions in the wake of the economically catastrophic decade of the 1980s particularly in Africa. Moreover, the increasing amounts of money set aside for ODA were difficult to justify without referring to Danish political priorities.

Another long-standing concern in Danish development cooperation is a focus on poverty reduction which sometimes has played an important role and sometimes not. It is the overall goal of all laws and strategies for Danish development cooperation, and even though other priorities have often dominated the agenda, poverty reduction is always a potentially important argument. Against this worthy ambition stand short-term interests of which a significant one is commercial. The “percentage of return,” signifying the proportion of aid going to Danish companies and jobs, was a dominant issue in Danish foreign aid until the first years of the new millennium. As much as 70 percent of bilateral assistance was tied to Danish products, firms, and experts until around 1989 (Bach et al. Reference Bach, Olesen, Kaur-Pedersen and Pedersen2008: 488). Despite criticism from OECD’s Development Assistance Committee it was only in 2004 that Denmark began using EU procurement rules in this field (Bach et al. Reference Bach, Olesen, Kaur-Pedersen and Pedersen2008: 488). Moreover, various programs to stimulate cooperation between Danish firms and enterprises in developing countries have been in existence since the early 1990s. The focus on poverty reduction and the concern with commercial interests have generally existed quietly alongside each other as a kind of political compromise between left-wing and right-wing parties. Although the support of commercial activities was supposed to contribute to poverty reduction, this was never organized in a thorough manner.

Around the turn of the millennium, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (presented as “Danida” when it comes to development cooperation, yet there is no organizational distinction between the ministry and Danida) was characterized by two developments: one was an attempt to significantly strengthen and streamline aid management, primarily by developing a set of aid management guidelines, setting up a unit for quality assurance in the ministry, and undertaking regular performance reviews of embassies. The other was the decentralization of substantial aid management powers to the embassies which were henceforth responsible for developing new support programs (Engberg-Pedersen Reference Engberg-Pedersen2014). This constituted a relative emphasis on pragmatic cooperation and poverty reduction, and, in retrospect, the 1990s could be characterized as the heydays of Danish foreign aid. It was backed by the government, the budget was large and constant, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs developed an “active multilateralism,” and a professional and long-term commitment to program support increasingly characterized bilateral cooperation. During the 1990s and the early 2000s, Danida formed Danish development cooperation largely in agreement with international norms as they emerged in OECD’s Development Assistance Committee.

6.3 Falling from the Heights

The change of government in 2001 not only brought about a cut in the overall aid budget (see Figure 6.1), but also clearly downgraded aid and development cooperation from its earlier significant position in Denmark’s international engagement, in favor of security concerns and military intervention. Danish troops had been deployed to the Balkans during the late 1990s and the new government began to prioritize “hard” instead of “soft” solutions to security challenges and went on to engage in the Iraq war in 2003, with very narrow parliamentary support. The main concern in this process was to comply with the wishes of the US government (Mariager and Wivel Reference Mariager and Wivel2019). Moreover, the government adopted a tougher stance toward Danish development NGOs and initiated a quick phasing out of bilateral support to Eritrea, Malawi, and Zimbabwe. The linking of security and development came to dominate foreign aid, and funds were increasingly channeled toward fragile states, notably Afghanistan, Iraq, and Somalia (the Danish support for these three countries rose almost twenty-four times from 2001 to 2009).

The purpose of the fund for aid to the environment and to catastrophes was in 1999 enlarged to support peace and stabilization, in response to the conflicts in the Balkans. Some politicians argued that ODA should not be channeled to the Balkans, used to receive Kosovo-Albanian refugees, or allocated as relief to sudden catastrophes, as this would jeopardize the scope for planning development activities in Africa (Bach et al. Reference Bach, Olesen, Kaur-Pedersen and Pedersen2008: 411–412). All major political parties supported this agreement, but with the change of government two years later the fund was shut down and resources for relief, stabilization, and environment had to be found within the reduced aid budget.

The decentralization of aid management was strongly influenced by cuts in administrative resources in the early years of the new millennium. The new liberal-conservative government wanted to make the public sector more effective, and “more bang for the buck” became an important slogan. Between 2001 and 2004, the administrative resources of Danida were reduced by 25 percent, which prompted a DAC peer review to note: “This decreasing trend in administrative resources raises the question of how far Danida can reduce its resources without negatively affecting quality and its ability to adapt to new aid modalities” (OECD/DAC 2007: 16).

Focusing on the last ten years, five issues stand out in Danish foreign aid as areas of change: (i) the proliferation of general policy papers and high-level political changes with respect to aid; (ii) the reduction of foreign aid; (iii) the use of development assistance for asylum seekers in Denmark; (iv) the attempts to mobilize the private sector for development purposes; and (v) the focus on fragile situations, refugees, relief, and development. The subsequent analysis explores the degree of change in these different areas and discusses the interaction between humanitarian ambitions and contingent, pragmatic, or instrumentalizing drivers.

6.4 General Policy Papers and the Law

After a reshuffling of government, a well-known, rather ideological politician, Søren Pind, was appointed development minister on February 23, 2010. This ended a period of relative quietness regarding Danish foreign aid. Søren Pind baptized his department the Ministry of Freedom, invited the private property proponent Hernando de Sotos to Copenhagen, and presented the first new general policy paper in ten years, called Freedom from Poverty, Freedom to Change (Danida 2010). Apart from introducing a strong focus on freedom, the paper did not contain many surprises compared to Partnership 2000. Poverty reduction continued to be a stated objective, the partnership approach was reiterated, and the five priorities included the three earlier cross-cutting concerns (gender equality, democratization, and climate/environment) while supplementing them with economic growth and stability in fragile situations. To some extent, the paper was not much more than a policy update couched in a liberal ideology. On one point the paper did, however, reflect a new approach to development cooperation. Hitherto, the primary issue influencing the choice of new cooperation countries had been their level of poverty, but this was changed into three principles (development need, relevance, impact and results) where “Danish interests” were specifically mentioned (Danida 2010: 11). As the three principles were equally ranked, the policy introduced the possibility of selecting countries other than low-income countries as partners and this was new. The paper was met with a lot of opposition in parliament, but not for its content and clear-cut liberal messaging.Footnote 2 The government announced a nominal freezing of foreign aid together with the draft policy paper, provoking the opposition to vote against the policy. Such a narrow adoption of a general policy paper on development cooperation was unusual and it reduced the legitimacy of the policy.

After the elections in September 2011, a government led by the social democrats came to power. The new development minister, Christian Friis Bach, had a background in civil society and research. Given that the new government had voted against Søren Pind’s development policy, a different policy paper had to be prepared. As the law framing Danish development cooperation dated back to 1971, Christian Friis Bach decided to change both in one go. The law establishes a broad set of objectives for Danish foreign aid, including poverty reduction, human rights, democracy, sustainable development, peace, and stability. In addition, it refers to the importance of policy coherence for development which was a relatively new phenomenon in a Danish context.

The policy paper, The Right to a Better Life (Danida 2012), stands out in four different ways. First and foremost, it introduced a human rights-based approach, which created some unease in Danida. Although the ministry was used to handling policy dialogues with public authorities in developing countries, advocating the roles of duty bearers and rights holders seemed rather intrusive and in opposition to the historical emphasis on partnerships in development cooperation. Secondly, green growth was promoted vigorously. In Danish foreign aid, economic growth has always constituted a condition for poverty reduction, but the policy paper elevated it to one of four priorities and the minister states in the introduction that “[p]overty must be fought with human rights and economic growth” (Danida 2012). The government had established the position of Minister of Trade and Investments in an attempt to strengthen commercial relations abroad, and the policy paper refers to the use of “public-private partnerships and innovative financing modalities as catalysts for green growth through enhanced cooperation on technological development and energy and emission-reduction interventions in developing countries” (Danida 2012: 22). This was the first visible step toward later efforts to mobilize private capital, particularly for energy investments. Thirdly, gender equality and the environment were downplayed as independent priorities and integrated into other issues. Fourthly, policy coherence for development was underlined, partly in response to the increasing complexity of global development.

A new change of government preceded the most recent paper on development policy, The World 2030, published in January 2017 (Danida 2017). This paper differs from all earlier development policies by being the product of a political agreement in parliament with the support of all political parties, bar one. It is, accordingly, more binding politically than earlier papers. Still, it is phrased in broad terms and does not exclude specific activities. Just as the liberal-conservative government of the 2000s lived happily with Partnership 2000 although it had been developed by the earlier social democratic government, it seems that the policy papers constitute a platform more for signaling policy priorities than for negotiating agreements that can constrain Danish development cooperation.

The paper was drafted in the wake of the refugee crisis when Syrian refugees marched along Danish roads to reach Sweden. This is clearly reflected in the policy, as two of four main priorities deal with reducing the number of foreigners coming to Denmark. One addresses security and development and focusses on supporting refugees and host communities in areas neighboring crisis and conflict. The other deals with migration and development and specifically seeks to counter “irregular economic migration and … address … the root causes of migration” (Danida 2017: 5). As such, migration is perceived as something to prevent. The two other priorities are well-known concerns: (i) inclusive, sustainable growth, and freedom, and (ii) democracy, human rights, and gender equality. From a relatively apolitical and devalued position under social protection in The Right to a Better Life, gender equality is again an important issue on a par with other basic values.

In addition to the focus on refugees and migrants, the new policy features three other points. First, the paper emphasizes the need to integrate humanitarian relief and development cooperation. While this is not new, the issue is here presented in close relation to the priority of supporting refugees and host communities neighboring conflict areas and is based on the well-documented observation that displaced people often cannot return to their homes in the short or medium term. In a world where climate change is likely to induce substantial numbers of people to move, the policy change is, however, fundamental as climate change risks jeopardizing long-term efforts to bring about significant progress. With an increasing allocation of resources to ever-changing locations of natural disasters and social conflicts, the accumulation of experience and trust gained through long-term partnerships with authorities and organizations in particular areas becomes difficult. This undermines the effectiveness of development cooperation though it may increase the sustainability of humanitarian relief.

Secondly, the policy wants to move “from charity to investment.” The priority on inclusive, sustainable growth does not primarily concern support to better economic policies or strengthened institutions creating an enabling economic environment in poor countries which, internationally, has constituted the main approach to growth since the late 1980s. Instead, it is argued:

Denmark will invest in inclusive, sustainable growth and development in the developing countries, focusing on energy, water, agriculture, food and other areas where Denmark has special knowledge, resources and interests. This will contribute to creating sustainable societies with economic freedom, opportunities and jobs – especially for young people. It will also benefit the Danish economy, trade and investments.

Despite later discussions of the importance of an enabling business climate (Danida 2017: 28), there is an evident focus on mobilizing private capital and on creating opportunities for Danish companies.

Thirdly, the policy sets out three categories of cooperation countries: poor, fragile countries and regions; poor, stable countries; and transition and growth economies. It states that these categories have been elaborated “to create convergence between the need for support in the developing countries and the representation of Danish interests” (Danida 2017: 8). Moreover, cooperation with transition and growth economies is intended to stimulate sustainable development with poverty reduction only as a derived effect. This categorization seems to use the SDGs and the notion of sustainable development to support the move of Danish aid away from a strict focus on low-income countries.

The progression of policy papers documents a change of policy toward satisfying Danish commercial interests through development cooperation. Foreign aid is no longer directed only toward poor countries, growth is to be stimulated through investment, and Danish capacities will form the basis of the thematic and sectoral orientation of Danish aid. Together with the strong focus on stimulating refugees and irregular migrants to stay away from Denmark, the move toward satisfying short-term, non-development interests through development cooperation shapes the policy papers, not altruistic motives of long-term poverty reduction. This change is strongly related to the economic crisis from 2008 onward and the increasing number of asylum seekers around 2015. In this sense, international events significantly influence Danish development cooperation, but domestic politics and contingent occurrences (the personality of development ministers, refugees marching on the highways) have been crucial in shaping recent policy papers. Notably the 2017 policy is much less in agreement with international trends than the development policies of the 1990s. Its superficial references to the SDGs and to climate change suggest that these significant international concerns are perceived as secondary in Danish development cooperation.

6.5 Changing Economic Support for Development CooperationFootnote 3

Entering the 2010s, Danish foreign aid amounted to 0.83 percent of GNI and the liberal government of the time decided to lock the nominal amount at DKK 15.2 billion, implying a slowly decreasing percentage of GNI, which began to speed up after the financial crisis. With the change of government in September 2011, the allocations were increased to maintain aid at 0.83 percent of GNI. While in opposition, the liberal party, Venstre, announced in September 2013 that Danish aid should be cut to 0.7 percent of GNI to save money and because this is the level recommended by the UN. When this party came to power in June 2015, the cuts were quickly made. This implied a reduction of the number of priority countries from 21 to 14 and a phasing out of Danish aid to Bolivia, Central America, Indonesia, Pakistan, Nepal, Vietnam, Mozambique, and Zimbabwe. Since then, Danish official development assistance has continued to amount to 0.7 percent of GNI, and in February 2018 the Social Democrats announced that they do not see any scope for raising foreign aid again if they form a government in the future. While in power (2012–2015) their intention had officially been to raise aid to 1.0 percent of GNI, but they never took initiative to do so.

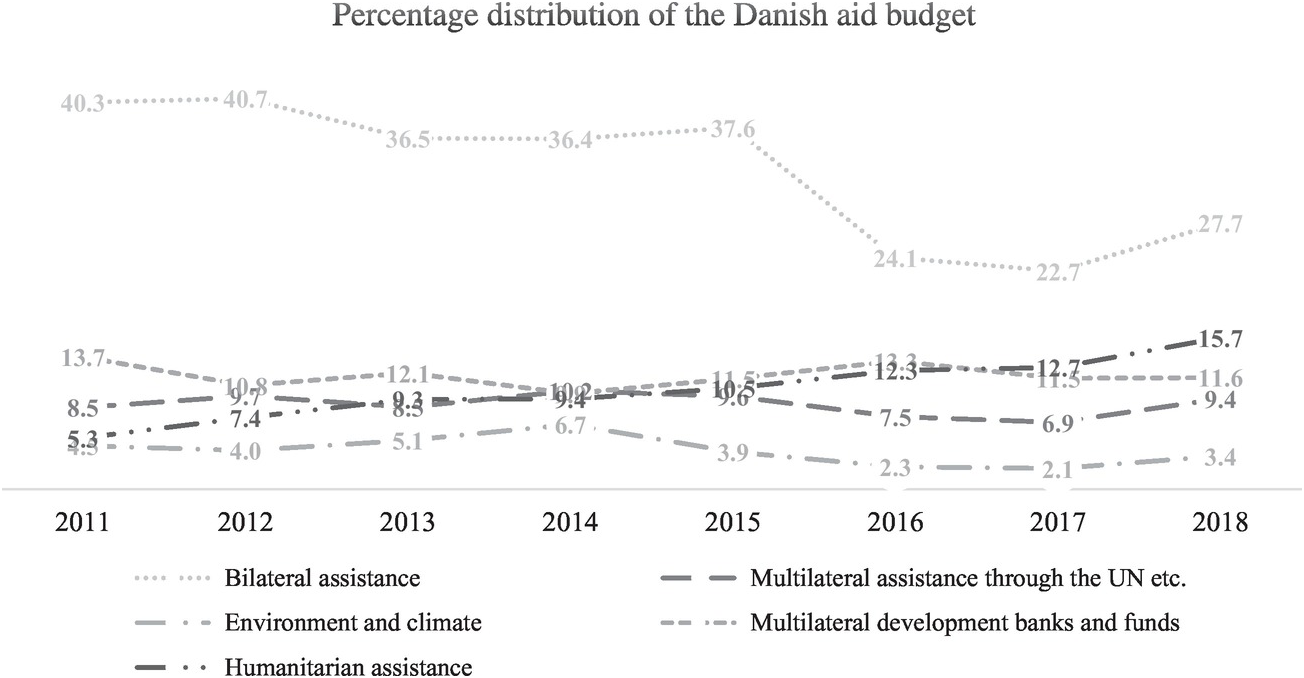

In terms of the distribution of the aid budget for different purposes, changes have also taken place. Figure 6.2 gives an indication of the distribution of aid between bilateral assistance, environmental and climate support, humanitarian relief, multilateral assistance through the UN system, and assistance through multilateral development banks and funds.

Figure 6.2 Percentage distribution of the Danish aid budget 2011–2018.

Note: The different categories are based on the organization of the financial bill. As there are other budget items (e.g. costs of receiving asylum seekers), these five items do not add up to 100 percent.

Four points can be highlighted based on Figure 6.2. Firstly, the role of bilateral assistance has declined significantly. This is partly because this budget item can be cut relatively easily, partly because Danida looks for others to implement the assistance, to some extent due to the continued cuts of the administration. Secondly, the share of humanitarian relief has grown substantially, reflecting the increasing needs, but also the changed political priorities. Thirdly, the share of resources for climate change adaptation and mitigation has declined, and fourthly, the share allocated to multilateral institutions has been relatively stable, albeit with a fluctuating balance of resources going to the UN system and to the development banks. Actually, multilateral institutions and arrangements may have increased their share of Danish aid as these institutions are used under other budget items, notably humanitarian relief.

Comparing the 2010s to the 1990s, the political support for development assistance has clearly waned. In the 1990s, the ambition was to spend altogether 1.5 percent of GNI on development, relief, stabilization, and the environment abroad whereas this ambition has been reduced to less than half of it now. This is even more noteworthy given that GNI per capita has risen from approximately PPP $20,000 in 1993 to $51,000 in 2016. Thus, the political consensus holds that Denmark can only use a smaller share of a much larger economy on development assistance. This is probably related both to the increased focus on “hard” means in foreign policy from 2001 onward, and a generally declining political interest in Denmark’s international activities,Footnote 4 with the largest political parties on both sides of the aisle now subscribing to an aid percentage of 0.7. The lukewarm political support is also reflected in the composition of the aid budget where bilateral assistance, which was strongly defended 10–20 years ago, has lost a considerable part of its budget share without strong political reactions.

6.6 Development Aid Used for Asylum Seekers

Over a period of 15 months from August 2014 to November 2015, the budget for development assistance changed dramatically. This was related to the arrival of asylum seekers, primarily from Syria, the number of whom peaked at 5,094 in November 2015. In August 2014, DKK 980.1 million (5.8 percent of the total budgeted aid) was set aside for costs related to receiving asylum seekers in 2015. By November 2015 this amount had grown to DKK 4,436.9 million (30.0 percent of the total budgeted aid) for 2016. Obviously, this had a tremendous impact on other parts of the aid budget (see Table 6.1 and Figure 6.2). Bilateral assistance, support to climate change mitigation and adaptation, and multilateral aid channeled through the UN system were all halved. Given that Denmark was obliged to meet commitments to development banks and the EU and given that there was a political interest in maintaining the amount allocated to humanitarian relief, the cuts elsewhere in the budget had to be proportionally even deeper. The political willingness to use as much as possible from development assistance to cover the costs of asylum seekers without jeopardizing the OECD/DAC definition of ODA was very clear. In the November 19, 2015 agreement between the then government and three political parties together constituting a majority in parliament it is written: “The parties to the agreement concur that the possibilities for this [using official development assistance to cover the costs of asylum seekers] should be exploited fully – including if it becomes evident that asylum costs go up further during 2016 than has been budgeted for in the Finance Act for 2016” (Regeringen 2015: 19, authors’ translation).

Table 6.1 Shifts in the Danish development aid budget 2015–2016

| Main budget items | Danish development policy | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 (million DKK)a | 2016 (million DKK)b | Change (%) | |

| Bilateral assistance | 6,354.3 | 2,893.9 | −54.5 |

| Assistance through NGOs | 1,103.0 | 744.0 | −32.5 |

| Climate change | 652.0 | 301.0 | −53.8 |

| Multilateral assistance through UN | 1,629.1 | 824.6 | −49.4 |

| Development banks and EU funds | 1,941.6 | 1,968.5 | 1.4 |

| Humanitarian relief | 1,775.0 | 1,825.0 | 2.8 |

| EU assistance | 1,044.1 | 1,352.6 | 29.5 |

| Asylum seekers in Denmark | 980.1 | 4,436.9 | 352.7 |

| Total Danish aid | 16,893.0 | 14,777.7 | −12.5 |

a The budget for 2015 published in August 2014.

b The budget for 2016 published in November 2015.

Although other countries were discussing whether a cap should be put on the share of ODA to be spent on receiving asylum seekers, this was not considered by the political majority.

Summing up, Table 6.1 demonstrates a substantial change of aid policy priorities taking place at a very rapid pace, due to what can largely be described as contingent events. The political willingness to use aid within Denmark is considerable and the share of aid reaching developing countries seems to be of secondary importance. However, with the reduced number of asylum seekers reaching Denmark the last couple of years this share has gone up again.

6.7 Mobilizing the Private Sector

Danida has, for a long time, sought to engage Danish companies in cooperation with companies in developing countries to establish long-term, commercially viable partnerships contributing to economic growth, social development, and poverty reduction. A recent evaluation concluded, however, that one of these programs, the Business-to-Business Program, had succeeded in the field of technology transfer, but failed with respect to broader development objectives (NCG and DevFin Advisors AB 2014). This prompted Danida to close the program and to rethink its cooperation with the private sector.

Given the political interest in integrating private companies into development cooperation and sustained by the obvious point that the SDGs cannot be achieved through foreign aid alone, but require an immense mobilization of private capital, a variety of instruments have been proposed or developed. Some of these are variations of the earlier programs in the sense that they try to get Danish companies to exploit business opportunities in developing countries. In addition, three other major instruments have been strengthened or developed in the field of development finance. First, the contributions to the Danish Development Finance Institution, Investment Fund for Developing Countries (IFU), have grown in recent years, and IFU has established a number of special purpose funds (the Danish Climate Investment Fund in 2014, the Danish Agri-Business Fund in 2016, and the SDG Investment Fund in 2018) partly based on capital from Danish pension funds. The SDG Investment Fund is planned to consist of DKK 3 billion from IFU and the state plus another DKK 3 billion from pension funds. This amount is expected to generate investments of around DKK 30 billion in SDG-related projects in developing countries in the period 2018–2021. Although IFU has been formally untied from cooperating with Danish companies, it is still the expectation that most projects will have strong Danish components. Secondly, Danida Business Finance, which aims at helping finance large public infrastructure projects that would not otherwise obtain financing, is planned to grow in the coming years to DKK 400 million in 2019 (from DKK 350 million in 2010 and DKK 200 million in 2016). It provides soft, but tied aid. Thirdly, Denmark is a co-founder of, and investor in, the African Guarantee Fund which has provided guarantees for loans to small and medium-sized enterprises in Africa since 2012. The fund is viewed as a success as it has facilitated USD 800 million in loan disbursements to almost 8,000 enterprises in 38 African countries.

Although the results of these initiatives still have to materialize, they raise three questions in relation to the form and potential exceptionalism of Danish foreign aid. First, it is not clear how the new as well as existing business-related instruments will respond to the concern expressed in the above-mentioned evaluation, namely that partnerships and development finance may succeed in commercial terms but fail with respect to poverty reduction and other development objectives. Secondly, the formal (Danida Business Finance) and informal (IFU) tying of aid to Danish suppliers has not been challenged. On the contrary, it appears that tying of aid is not perceived to be a problem given that more money is expected to be channeled through these instruments. Thirdly, in terms of the share of aid allocated to low- versus middle-income countries, several of the instruments allow for activities in lower middle-income countries and some, including up to 50 percent of the SDG Investment Fund, can be implemented in all countries on the DAC list of ODA-eligible countries (the upper limit being GNI per capita of USD 12,235 in 2016). Together with the creation of a category of growth and transition economies in the latest general policy paper, it seems likely that an increasingly smaller share of Danish aid will go to low-income and least developed countries.

6.8 Fragile Situations, Migration, Relief, and Development

Alongside the interest in the private sector and commercial opportunities, security, migration, and refugees have been growing concerns since the late 1990s. Until the deployment of troops in Iraq and Afghanistan from 2003 onward, Danish cooperation countries were selected among poor but stable countries, partly because the sector-wide approach that was a cornerstone of Danish aid required a reasonably strong state in control of its territory. This changed, however, and Denmark began to provide development assistance to fragile states, particularly to Afghanistan and Somalia. The choice of Afghanistan was conditioned by the perceived security threat and the military intervention whereas the burden piracy was placing on Danish shipping companies explains the interest in Somalia. While Danida adopted a sector approach to education in Afghanistan, the support to Somalia has been channeled primarily through international organizations and NGOs with a foothold in different parts of the country. However, much emphasis has been put on getting Danish authorities better coordinated in relation to fragile situations. A policy on Denmark’s integrated stabilization efforts was published in 2013 (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of Defence, and Ministry of Justice 2013) emphasizing cooperation between diplomacy, aid, and the military/police. Moreover, a Peace and Stabilization Fund was established in 2010.

In recent years, migrants and refugees have become a center of attention in foreign aid as discussed above. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs has appointed an ambassador responsible for the repatriation of rejected asylum seekers, and the Minister for Development Cooperation and the Minister for Immigration, Integration and Housing have visited Nigeria together to pave the way for the repatriation of Nigerians. Moreover, funds (DKK 125 million in 2018) have been set aside for facilitating measures in this context, sometimes described by the ministers as quid pro quo. In February 2018 the Social Democrats, then in opposition, published a proposal for a new immigration policy, Fair and Realistic, in which they propose a “comprehensive reform of Danish development assistance” (Socialdemokratiet 2018: 24). They suggest spending DKK 3.5 billion more in areas neighboring conflicts and natural disasters which roughly means a doubling of the funds currently allocated to these areas. It is proposed to take the funds from long-term development assistance. While there are good reasons to consider how relief and development can be better integrated and how to support areas with a sudden huge influx of refugees, the suggestion of a comprehensive reform of development assistance in an immigration policy partly funded by reallocating DKK 3.5 billion presently used for purposes of long-term development evidences how little importance this major party attaches to development cooperation.

6.9 Conclusion

This chapter set out to explore and explain marked changes in Danish development cooperation over the past decades, against a background of self-perceived exceptionalism. While shifting development policies, perhaps predictably, have moved back and forth between sets of similar priorities that have been continuously repackaged, reframed, and reprioritized in their relative importance, remarkable changes have nevertheless occurred since the 1990s, and particularly in the last ten years. At its core, we find that Danish foreign aid has moved from a combination of a set of values (human rights, democracy, good governance, sustainable environments, gender equality, etc.) and a concern with the ideas in the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness (ownership, alignment, harmonization, and mutual accountability), toward a strong focus on short-term Danish non-development interests. The policies increasingly seek to satisfy Danish commercial interests, and choices of partner countries, sectors, and multilateral development activities are no longer strongly related to perceived needs, but rather made on the basis of investment potential, security risk, migration concerns, and Danish (often commercial) interests. Over time, Danish aid has increasingly been expected to support military intervention, to combat radicalization, to facilitate commercial relations, to finance Danish municipalities’ costs of settling refugees, and to limit migration to Denmark.

How come? How is it possible to explain this relatively fundamental change? Firstly, it should be noted that commercial interests have a long history in Danish development cooperation so the change builds on a long-standing concern with Danish interests in foreign aid. Secondly, the change clearly diverges from recent discussions in the international development community to which Denmark adhered much more 20 years ago. However, one may argue that the change mirrors an increasing focus on commercial and security interests both in the North and the South. In this sense, the change is not in contradiction with trends in other countries. Thirdly, Danish politics has been characterized by a strong belief in military interventions and a parliamentary situation creating an immense interest in migrants and refugees the last couple of decades. Thus, foreign aid has been decoupled from foreign policy concerns and reoriented toward domestic political interests.

It is obvious that the overall change of Danish foreign aid does not reflect a position of Scandinavian exceptionalism or of a “humanitarian great power.” Rather, the overarching driver of changes in Danish aid seems to have been the shifting domestic political priorities that have greatly influenced, and, in some cases, subordinated development aims. These domestic policy shifts have largely been driven by contingent events, whether 9/11 and the subsequent decision to follow the US into war in Afghanistan and Iraq, or the surge of refugees finding their way to Northern Europe, or the personalities of particular strong development ministers. A strategic and persistent aid regime has given way to short-term interests that do not use development policy and aid only to promote Danish ideas about development, but allocate aid resources for purposes only distantly related to poverty reduction and sustainable development. Funds that could have otherwise made a difference in solving international issues, importantly also for the long-term benefit of Denmark, have been used to cover expenses under the auspices of domestic financial constraints. If a particular political culture has emerged in Denmark, as it concerns development cooperation, it is one driven by subordination, instrumentalization of development aims, and a will to shift priorities to fit domestic political concerns.

Does the (his)story of Danish development cooperation and its politically both vulnerable and volatile nature mirror or convey narratives of the end of aid? Not necessarily. While ODA has seen somewhat stable levels over the past decades or more, development cooperation itself has never really been in a static state of affairs. Fluctuations, changes, and sometimes tectonic shifts have been the rule more than the exception over the past half century, and development cooperation has always been in a simultaneous process of leaving past practices and approaches behind while adopting new ones, forming an incredible elastic policy field. More so than the end of aid, then, today is what we may call a new time of pragmatic ambiguity, interestingly drawing on “old” ideas, whether self-interest, tied aid, or political ambitions. Development cooperation will likely have to suffer a fate of subservience, instrumentalized by politicians to further other political concerns and priorities, which aid is so well suited for. This does not bode well for a future of aid characterized by objectives of poverty reduction or the elimination of global inequalities. But the resilience, elasticity, and ability to manage policy shifts of development cooperation and its accompanying community of professionals, from NGOs to civil servants, coupled with the continued needs of vulnerable and marginalized populations, makes it difficult to buy into narratives of death and obliteration.