Throughout the ages, wars have taken place in countries and between nations. Although there is no single reason why conflict should occur, 1 or several of the following reasons may constitute the cause of war: economic or territorial gain, religion, nationalism, revenge, internal disagreement (civil war), ideological diversities (revolutions), and finally, as part of a defensive plan. Reference Frankel1,Reference Levy2 Theoretically, the causes of war can be divided into 3 groups. First, power vs. sovereignty illustrates the sovereign states’ systematic, rational, and sometimes unintentional aim to strengthen their security, power, and wealth at the expense of other nations by regulating minor conflicts or enforcing agreements. These actions, even defensively motivated, are often perceived as threats, resulting in armed conflicts. The second group encompasses societal reasons, displayed by a distinction between democratic and non-democratic governments and their relationship with their citizens. Finally, a war can be caused by individual decision-makers who express their understandings of threat assessment, national interests, and the ways they achieve their goals and make decisions based on the information they receive, their personalities, and emotional states. Reference Levy2–Reference Ohlson4

Whatever the cause, the culture of warfighting has always been conventional or irregular, displaying 2 different mindsets and 2 different approaches to warfare. Conventional warfighting occurs between states’ regulated militaries or alliances. It intends to defeat the enemy’s armed forces, destroy its war-making capacity, or seize/retain its territory, forcing a change in the enemy’s government or policies. On the other hand, irregular warfare is defined as either guerrilla warfare (rebels, freedom fighters, and non-traditional warfighters vs. traditional armies) or terrorism, and is aimed at avoiding strength, striking weaknesses, and being unpredictable. Asymmetric warfare occurs when these 2 warfighting cultures collide. Reference Monaghan5–Reference Mattis and Hoffman7 The current characteristics of warfare are the result of advancement in both warfighting cultures. Conventional warfare has advanced from the linear tactics employed on the battlefields of the 17th century to the early 20th century’s massed firepower and speed, and the surprise and dislocation strategies used in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. On the other hand, the diverse irregular warfare has progressed from evasiveness, exhaustion strategies, and urban guerrilla warfare, and resulted, among others, in terrorism. These dynamic changes have altered the nature of conflicts from interstates to wars amongst the people and resulted in asymmetrical wars. Reference Monaghan5–Reference Razma8

In 2005, Mattis and Hoffman predicted that a combination of conventional and non-conventional strategies would be the main feature of future wars (Hybrid War = HW). Such warfare would consist of methods and tactics that, besides causing medical injuries, would also enhance other aspects of war, such as psychological and information-related methods that aim to paralyze the ordinary functions, organization, and structures of society. Reference Mattis and Hoffman7 This prediction was further approved by Western military theorists in 2008, following “Operation Desert Storm in 1991,” emphasizing that the Western military’s conventional battlefield power and technological dominance would be challenged by their adversaries using diverse and multimodal tactics to increase the complexity of battle. The ultimate danger was the use of religious groups, or ‘non-Trinitarian’ adversaries and non-state actors, who could target Western vulnerabilities without fear, knowing they cannot be defeated through a conventional military campaign in a battle. Reference Monaghan5,Reference Mattis and Hoffman7,Reference Kamusella9,Reference Lowe, Williamson and Mansoor10

Although the Soviet Union’s involvement with the Tuvan Army in 1944 is an early example of HW in Europe, most of the younger generation may recall a change in the paradigm of the war from the traditional conventional war to modern warfare in the 1970s with the Vietnam War, the battle between Israel and Arab countries on the Golan Heights, and in the Sinai desert. Reference Monaghan5–Reference Mattis and Hoffman7,Reference Lowe, Williamson and Mansoor10 With an increasing number of minor conflicts, social and public health emergencies, global poverty, natural resource scarcity, climate change, migration, and an apparent rise in the number of refugees, there is a need for revisiting the roots of causes to minimize the risk for their occurrence. The ongoing war in Ukraine justifies a review of the concept of HW, comparing its outcomes to conventional warfare, and its impacts on the victims’ humanitarian law and medical management.

This systematic review summarizes the core characteristics of the HW and its humanitarian and medical impact, differentiating between conventional wars and HWs, and revealing the disturbing face of HW’s components in today’s war in Ukraine and elsewhere.

Methods and material

Systematic review

A systematic review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Reference Page, McKenzie and Bossuyt11 The searching process resulted in many articles based on the selected keywords in the first step. In the next step, duplicates and non-relevant articles were removed, and the authors independently studied the remaining studies’ abstracts to ensure eligibility and relevance.

A qualitative thematic analysis of the included literature based on an inductive approach was applied, aiming to study all included articles, and focusing on similarities and differences in the findings to present the tentative results. Reference Graneheim and Lundman12 Finally, each eligible study was thoroughly reviewed, and the data, including the year of publication, author’s name(s), the title of the study, and its scope, were registered. Additional articles on the reference list of included studies with relevancy for this study were added at the final stage.

The scientific evidence of each selected article was assessed using the Health Evidence Quality Assessment Tool (Appendix 1) as Strong, Medium, or Weak. 13 The initially designed electronic search model used PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Gothenburg University’s search engines to create a list of available literature in English, using the following search string: Hybrid War; Humanitarian Law; Human Rights; and Lawfare; alone or in combination.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria: Original studies in English, based on the search keywords above, from 2000 to 2022.

Exclusion criteria: Conference papers, only abstracts, unofficial reports, non-scientific publications, and publications dealing with other topics than the main aim of this study.

Study ethics

The material used in this paper was collected online from available publications.

Statistics

No statistical analysis was conducted.

Results

Literature review

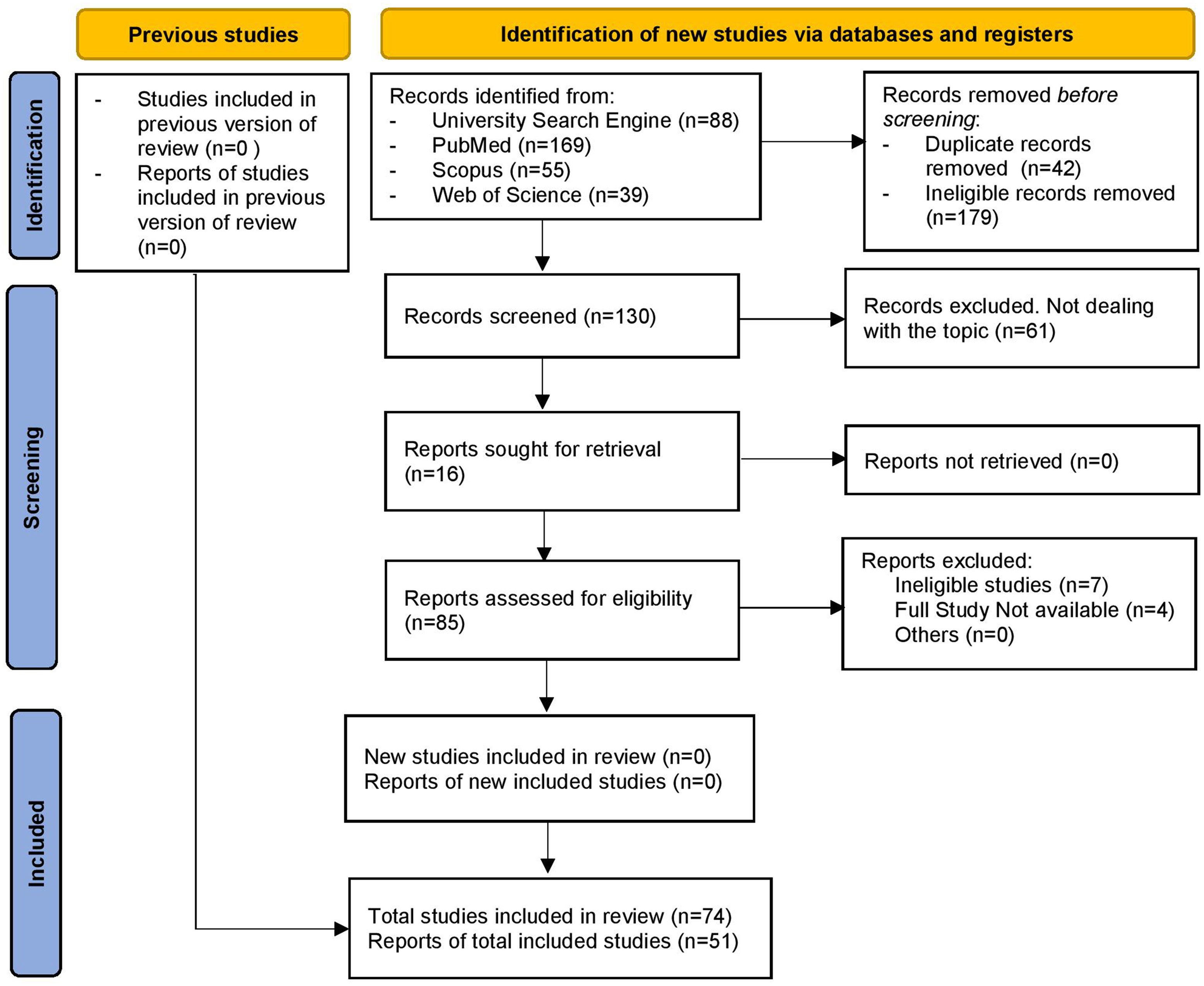

Using Hybrid War, many hits were obtained in all databases. Adding new keywords reduced the number of hits stepwise to achieve a manageable number of studies (Table 1). Figure 1 shows the process of search according to PRISMA.

Table 1. Searching strategies and outcomes of the search in scientific databases

Note: The search in Gothenburg University search engine could be refined by adding new keywords and 88 papers were included. The term ‘Medical outcomes’ did not add any new literature. Other search engines returned 169, 55, and 39 papers, which were included. Additional keywords did not add any further study. The bold numbers indicate the number of included studies in this paper.

Figure 1 Illustration of the searching process according to PRISMA.

A sum of 351 papers was included in the initial stage (88 from the university search engine, 169 from PubMed, 55 from Scopus, and 39 from Web of Science) (Table 1), of which 179 were found to be ineligible, and 42 papers were duplicate records. Out of the remaining 130 papers screened, 35 studies were irrelevant and excluded. From the final 95 studies, 10 studies were repetitive or incomplete. The remaining selected studies were all included.

At the final stage, 74 studies were included, of which 18 were official internet pages, and 5 were book chapters. A total of 51 papers were thoroughly reviewed for this paper and were included in Table 2. Content analysis resulted in several keywords grouped into 2 main topics: humanitarian (legal and policy) and medical impacts of conventional and hybrid warfare (Table 2).

Table 2. The outcomes of the literature review according to PRISMA

Findings

In contrast to conventional wars, modern warfighting strategy utilizes multi-domain operations, asymmetry, and a hybrid approach to create difficulties in predicting the means and processes associated with an armed conflict. Reference Khorram-Manesh14–Reference Spagat, Mack, Cooper and Kreutz18 This process spreads the war to the masses, using conventional assaulting methods, riots, disinformation, and infected social media. It also targets military staff, resources, civilians, and civilian infrastructure to create political instability. Reference Khorram-Manesh, Burkle, Goniewicz and Robinson17,Reference Spagat, Mack, Cooper and Kreutz18 Consequently, it may result in more civilian casualties than conventional wars, making estimation difficult for resource assessment and planning before the conflict, and creating clear concerns regarding the respect for International Human Law (IHL) and Geneva Convention (GC). Reference Khorram-Manesh, Burkle, Goniewicz and Robinson17

Humanitarian and medical consequences of HW

-

1. Humanitarian impacts of conventional and hybrid wars: Lawfare - International Humanitarian Law, Human Rights, and Geneva Convention

Traditional wars symbolize an armed conflict between 2 or several countries. However, they usually follow the IHL and GC. IHL is a (cf.) “set of rules, which seek humanitarian reasons, to limit the suffering, losses, and other effects of armed conflict by restricting the means and methods of warfare to protect individuals who are not or are no longer participating in the hostilities.” The Geneva Convention is a (cf.) “series of treaties on the treatment of civilians, prisoners of war, and soldiers who are otherwise rendered outside the fight or incapable of fighting.” Reference Khorram-Manesh, Burkle, Goniewicz and Robinson17–21 According to IHL, “A State” is responsible for all attributable violations of IHL committed by its organs (including its armed forces) and persons or entities it empowered to exercise elements of governmental authority. 21,22 It is also responsible for the deeds of those acting in fact on its instructions, or under its direction or control, and by private persons or groups, which it acknowledges and adopts as its conduct. Reference Arakelian, Bekhrus and Yarova20–22 In contrast to conventional wars, there is constant negligence of IHL and GC implementation in modern armed conflicts since the objectives of the wars have changed, and it is more critical to achieve the tactical and strategical goals in a battle than to save civilian lives. Reference Burkle15,21

The responsibility for implementing the principles of IHL lies on the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement (IFRC) and the International Institute of Humanitarian Law (IIHL). The International Committee of Red Cross (ICRC) is the operational institution responsible for protecting victims of conflicts within a country and across boundaries. 21,22 According to IHL, ICRC has the mandate to gain insights into an ongoing battle and, as an impartial, neutral, and independent organization, protect the lives and dignity of victims of war and internal violence by assisting the affected population directly, coordinating the international relief activities, promoting the importance of IHL, and drawing attention to universal humanitarian principles. 22,Reference Burkle23 Additionally, they also have mandates to visit prisons, organize relief operations, reunite separated families, meet the needs of internally displaced persons, raise public awareness of the dangers of mines and explosive remnants of war, and trace people who have gone missing in conflicts. Reference Burkle23 These tasks allow ICRC to track war activities and present an accurate picture of casualties and deaths. In contrast to conventional wars, modern armed conflicts involve networks of state and non-state actors with various means of military and militia influences and strategies, which creates difficulties in implementing, controlling, and evaluating IHL’s “A State responsibility” principle and does not allow international organizations to gain insight into an armed conflict. Reference Khorram-Manesh14,Reference Burkle15,Reference Arakelian, Bekhrus and Yarova20

Of significance in both the current Ukrainian war and similar HWs is the emergence of Lawfare, which according to Dunlap, is ‘the strategy of using (or misusing) law as a substitute for traditional military means to achieve an operational objective.’ Reference Dunlap24–Reference Pfanner26 An immediate outcome of Lawfare is its impact on the international law and judicial processes, weakening the International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights Law, which may become entirely inapplicable. Reference Khorram-Manesh, Burkle, Goniewicz and Robinson17,Reference Khorram-Manesh, Goniewicz, Burkle and Robinson27,Reference Canyon and Burkle28 From an HW perspective, there is an increase in war crimes, social chaos, and internal criminality in the invaded nation by unconventional actors who can operate beyond the control of states by bypassing interstate and international borders’ norms and agreements. The clash and confrontation with these actors, whether they belong to global terrorist networks or criminal elements, aims to destabilize society and would lead to a collision beyond the physical aspects of the conflict in which media manipulation, the use of the internet, and the integration of information operations with strategic communication programs are as necessary as weapon systems on the battlefield. Reference Ciobanu29

During conventional wars, soldiers were always the primary target, and civilians were always allowed to leave the conflict area to protect themselves from deaths and injuries. Reference Burkle15 On the other hand, hybrid wars bring the battlefields into the civilians’ backyards, making them vulnerable and involved in fights. Reference Khorram-Manesh14 The outcomes have been many; however, the increase in civilian fatalities from 5% at the turn of the 19th century to 15% during World War I (WWI), 65% by the end of World War II (WWII), and to more than 90% in the wars during the 1990s, is without a doubt 1 of the most significant outcomes of HWs, Reference Khorram-Manesh, Burkle, Goniewicz and Robinson17 stating the clear objective of HW, focusing on local populations, infrastructure, and communities, where civilians can be found. Reference Razma8,Reference Burkle15,Reference Phelan16 The aim justifies the means and becomes the background and the motto for each intervention. The goal is to influence the achievement of significant geostrategic goals which promote their impact and ideology and increase their reputation globally. Reference Ciobanu29

HWs generate millions of displaced persons, which overwhelms healthcare and relief organizations’ working capacity. Reference Khorram-Manesh and Burkle30–Reference Ri, Blair, Kim and Haar34 It increases the vulnerability of protective authorities, consumes legal and healthcare systems, paralyzes the national government, and finally may dissolve national unity. Reference Razma8,Reference Khorram-Manesh, Burkle, Goniewicz and Robinson17,Reference Ri, Blair, Kim and Haar34–Reference Konaev43 A state of ‘no authority and no legal forces,’ enhances the violation of IHL, HR (human rights), and equality with no punishment. These scenarios endanger the mandated work of international organizations to supervise and regulate the rules of the war. It also disables receiving the correct information and enhances the possibility of belligerents and terrorists hampering a democracy. New military strategies, remote warfare, drones, proxy fighters, and hybrid warfare present the face of modern and unconventional war, which threatens and takes civilian lives and raises new ethical and moral concerns when violating IHL and GC. Reference Burkle15,Reference Khorram-Manesh, Burkle, Goniewicz and Robinson17,Reference Arakelian, Bekhrus and Yarova20

-

2. Medical consequences of HW

The medical consequences of HW depend on several factors, such as the duration of the war, the place it occurs, and the population density. HW aims at attacking the infrastructure of a community by using several tools. Healthcare usually needs a capacity surge, which relies on the 4 vital elements of the surge capacity, i.e., ‘staff, stuff, space, and systems’ (guidelines and instructions). There are apparent differences between conventional wars and HW in their medical outcomes regarding the 4 elements of surge capacity and 3 decisive factors in conflict, i.e., war duration, combat field, and population involvement. Reference Khorram-Manesh, Goniewicz, Burkle and Robinson27,Reference Reiter44,Reference Khorram-Manesh45

-

a. Duration of the war

The duration of a conflict is a very significant factor in the medical management of victims. Short wars may result in a high number of casualties, but in the long term, the healthcare system may be able to recover quicker than in a long and devastating conflict. Reference Reiter44 More extended conflicts are associated with a lack of staff, stuff, and spaces to facilitate medical care. Conventional wars consume military service members in different positions with little impact on the civilian population who are usually not involved on the battlefield. Reference Khorram-Manesh45 HW involves military and civilian populations, targeting both sides’ resources, including medical facilities and staff. Therefore, in contrast to conventional war, HW impacts the entire list of diseases and emergencies. Whereas war creates emergency cases of trauma and combat-like injuries, the longer duration of HW conflicts normally consumes all medical resources leading to the population’s difficulty to obtain equal and available care. Overwhelmed hospitals may not assess and treat people with chronic diseases, worsening people’s medical conditions while waiting to access healthcare. Reference Khorram-Manesh, Goniewicz, Burkle and Robinson27,Reference Hägerdahl41–Reference Khorram-Manesh45

-

b. Field of combat

Conventional wars occur in militarized areas, with no involvement of civilians. HW, however, happens everywhere and destroys infrastructures that provide care, energy, logistics, and coordination. The most severe damages and injuries can be obtained when the invaders attack chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) facilities. Reference Padarev46,Reference Calder and Bland47 The outcome will undoubtedly be disastrous, involving the affected countries and even millions of people living around the conflict area. There is a high risk for the latter in an HW compared to a conventional war, requiring immediate medical response and practical support such as protective items, unaffected ambulances, and many others. Reference Calder and Bland47 The damage inflicted to the infrastructure, as 1 of the main goals of HW, would also prevent the ordinary population from receiving appropriate healthcare for their diseases, meaning that benign and malignant cases, such as cardiovascular diseases and various types of cancers, will not receive the treatments they need. Reference Kutikov, Weinberg and Edelman48

-

c. Population density

HW, intentionally or unintentionally, focuses on the populated areas within the invaded country. Therefore, it is logical to assume that the casualties would be much higher, and would consist of predominantly civilian populations. Earlier casualty estimation tools used in conventional war are incompatible with the current HWs and cannot be used. Consequently, the lack of knowledge and tools to assess the number and types of injuries creates particular difficulties for healthcare, whose tasks cannot be conducted without necessary resources. Reference Burkle15,Reference Khorram-Manesh, Burkle, Goniewicz and Robinson17,Reference Friesendorf35,Reference Vautravers37,Reference Cincotta, Engelman and Anastasion38 Previous publications have indicated that casualties and deaths are likely too high to plan properly. Therefore, the only measure for any contingency plan is to focus on what they may be able to do. In such a situation, other medical tools such as triage, must properly categorize victims that can be saved. This, in turn, calls for discussions regarding the moral and ethical perspectives of medicine and triage under extreme conditions. Reference Khorram-Manesh, Burkle, Goniewicz and Robinson17,Reference Hägerdahl41,Reference Khorram-Manesh49

Inflicted injuries and deaths in HW

The transformation of regular warfighting to HW indicates that injuries inflicted in HW might be a mix and match of the multi-domain characteristics of HW. That, in turn, means a variety of injuries should be considered depending on the occasions and specific domain used. In this perspective, injuries and deaths may occur during riots, demonstrations, and minor armed conflicts in various unplanned places. Criminal gangs may also conduct their part by using lighter and heavier weapons. Additional injuries and deaths may also occur due to disruption in Internet Technology (IT), loss of electricity, and the damage inflicted to this infrastructure. The target of these attacks is the local communities and civilians. Explosives and suicide bombings have been the primary means of terror in previous HW terror attacks, with a variation of mortality ranging from 3 to as high as 2996, injuries ranging from 49 to 6000, and a ratio of deaths/ total casualties of 8 to 51%. Reference Khorram-Manesh, Burkle, Goniewicz and Robinson17,50–Reference Williamson and Murphy57 An important denominator of these attacks is the chaos and overwhelming pressure they create for emergency services, particularly healthcare. A high number of injuries require both a multiagency approach and availability of healthcare in several hospitals and healthcare facilities, along with local preparedness at the community level for both adult and pediatric conditions and military-like injuries. The multi-level confrontations and assaults in HW result in resource scarcity, particularly within the healthcare systems over a more extended period, causing deaths and a need for critical non-traditional medical decision-making. Reference Cronin58,Reference Grant and Kaussler59

Discussion

Although the etiology of wars may vary, every country and group may define international laws and conflict rules differently. Clark et al. discuss the respect for laws of war in 3 different cases of ISIL (the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) in the USA and Russia. Reference Clark, Kaempf, Reus-Smit and Tannock60 ISIL has openly challenged all laws, order, and war regulations (rejectionist). Reference Mendelsohn61 In contrast, despite its efforts to implement the laws and rules into each layer of its military, the USA has, since the 9/11 terror attack, questioned the meanings and categories central to the body of law and has not achieved its goals (revisionist). Reference Hasian62 Russia, on the other hand, first presents itself as the guardian of international law, ready to be and to make other states accountable, but later, despite evidence to the contrary, has systematically denied the violations of those laws and invented a new reality about the conflict by employing a sophisticated public relations strategy (denialist). 63 With a decreasing number of conventional wars in favor of hybrid and asymmetric wars, civilian deaths have increased continuously from the turn of the 19th century to the World Wars and the conflicts in the 1990s. Reference Burkle15 During this period, there has also been a continuous blunder for the IHL and the GC in favor of: 1) tactical and strategical harvesting, 2) religious and political hatreds, 3) the collapse of State structures, 4) mastering the scarcity of natural resources, and 5) the vast availability of weapons, increased acts of terrorism and the spread of asymmetric conflicts. Reference Burkle15,33,64

Interstate conflicts are costly interventions that consume thousands of military service members, new technologically advanced weaponry, and military capabilities such as jets, helicopters, and tanks. Countries like Russia need to develop unconventional capabilities, a complex of activities with military and non-military means that will have the advantage over conventional means used by the USA and its alliances to achieve their political goals. Reference Reichborn-Kjennerud and Cullen65–Reference Hoffmann, Chochia, A and Hoffmann67 The term HW was initiated in Russia and first used by Western theorists during the Crimea conflict in 2014. For the Russians with a tendency to bypass and deny international rules and law, HW seems to be the preferred warfare course now and in the future, including the use of UAVs (Unmanned Aerial Vehicles). Reference Hoffmann, Chochia, A and Hoffmann67 Other nations closely associated with Russia seem to have adopted a similar strategy, which indicates the use of lawfare for misleading, exploitation of legal systems, and the use of technologically advanced techniques and devices. Some researchers believe that future conventional and hybrid scenarios may seek targeted killings to limit or escalate control, together with deniability of air operations. Reference Senn and Troy68,Reference Haas and Fischer69 The recent Russian experience in Georgia, Ukraine, and Syria is undeniable evidence of Russia’s continuous plan to develop unmanned combat capabilities. Reference Bendett70

Having an in-depth analysis of the global conflicts, such as the 1 in the Middle East and the South China Sea, the immediate danger to worldwide peace is the capability of HW for implementation in populated conflict zones, with the participation of the civilians, under the eyes of the international community. Reference Hoffmann, Chochia, A and Hoffmann67,Reference Senn and Troy68 Such an environment has no issue in incorporating HW’s concept into extremist groups and their ideology, fueled by poverty and significant economic and social problems, strives for a change. The idea, together with its actors, creates a system that could be structured on several levels such as political, diplomatic, social, economic, informational, military, psychological, and cultural levels of dissatisfaction and discontent, and result in various actions on the causes, effects, phenomenon, value systems, critical areas, vulnerable sites, and on the leaders. The outcome would be no human rights, no international humanitarian laws, and no respect for GC. Reference Marcuzzi6–Reference Lowe, Williamson and Mansoor10,Reference Hoffmann, Chochia, A and Hoffmann67–Reference Bendett70 The 90% increase in the global urban population in developing countries over the next 2 decades increases these nations’ vulnerability to political and social unrest, violent crimes, terrorism, disasters, and armed conflicts, and increases the opportunities for HWs. Reference Kaldor39,Reference Posen71 There is a need for flexibility and an increase in the implementation capacity of the IHL regulations to maximize the opportunity to observe and better control casualties and deaths, and minimize the number of deaths and injuries. It is necessary for the IHL to continuously keep up with the pace of new developments in modern wars and simultaneously be prepared for the unexpected and the unknown.

Although conventional wars seem to be ‘good’ in comparison to the ‘bad’ HW, new military strategies, remote warfare, the use of drones, and proxy fighters among others, present the ‘Ugly’ face of modern and unconventional warfare, which not only threatens and takes civilian lives, but also raises new ethical and moral concerns when violating IHL and GC. Reference Burkle15,Reference Arakelian, Bekhrus and Yarova20,Reference Posen71 It is not a secret that qualified healthcare in harmony with equality and safety can only be offered when the society allows critical evaluation and follows democratic values. Reference Burkle25 There are clear signs of how scientific and technological progress, political, social, economic, environmental, and military factors, may influence the transformation of liberal-democratic regimes and the global order. Reference Rudyi, Makarchuk, Zamorska, Zdrenyk and Prodan72 In order to guarantee social liberty, human rights, and the right to enjoy proper healthcare in peace and war, there is a need to preserve a liberal-democratic state-legal regime as the most successful of all administrations offered to the public and future generations. This might be the only way to let nations invest more in education and healthcare than investing in military capacity to invade other countries.

Several reasons may have caused the current Ukrainian conflicts. A major reason is the desire for natural, human, territorial, financial, economic, information, humanitarian, and other Ukraine resources. Another reason is the ideological split. Undoubtedly, the ideological differences between people have been used by covert military operations and adversarial informational methods to achieve the current situation. Reference Pankevych and Slovska73 However, for the Ukrainian nation, the outcomes of this war are destroyed infrastructure, economy, and a large number of deaths and casualties that the unprepared healthcare cannot manage. Preparedness is a continuous process built upon a functional ordinary healthcare system. Such preparedness requires planning and the ability to observe the unforeseen future. Although many authors emphasize the nations’ vulnerability in economic, IT, and energy sectors, Reference Bachmann and Papithi74 there is little, if any, said regarding nations’ healthcare systems as a bottleneck in an HW. Violence disrupts trade and agricultural activities, forces people to migrate, and interrupts health and other social services. Such interruption necessitates extra measures, especially in countries where the healthcare system in war is not independent and requires collaboration between agencies, such as civilian and military collaboration. Reference Khorram-Manesh, Burkle and Phattharapornjaroen75,Reference Downes76

Overall, to minimize the risks associated with HW, there is a need for a multi-dimensional approach to its multi-domain characteristics. The supra-national dimension of HW requires legal and social measures which necessitate international collaboration. A single piece of legislation is neither feasible enough nor desirable. Another possibility is the integration of the 2 mindsets, creating a mixed leadership and a hybrid, agile organization, which can be very effective in an uncertain, complex context. Such integration will not happen without facing extreme challenges and struggles. Reference Lonardo77–Reference Johnson79 Nevertheless, it can be impossible for healthcare to estimate the number of casualties. The only way might be to accept an acceptable loss (acceptable damage or casualties), which refers to casualties or destruction inflicted by the enemy that is considered minor or tolerable. Reference Khorram-Manesh, Burkle, Goniewicz and Robinson17,Reference Spears80

Limitations

Inductive data analysis is often time-consuming, requiring in-depth reading and rereading of material with a certain number of assumptions, which takes skill and practice to effectively analyze without bringing in personal biases while producing valuable data that can lead to a hypothesis about the phenomenon. Furthermore, the studies included in this paper were all in English, possibly missing critical information in other languages.

Conclusion

There is little understanding of hybrid wars evident with the onset of the current war in Ukraine. The ideology of those conducting asymmetric and hybrid warfare overwrites the interests of individual nations and our universal values. The threats imposed by multi-domain actions should be met with multi-dimensional approaches and the “acceptable losses” doctrine. The current geopolitical security risk and their potential impacts on the security systems require a continuous adjustment of the operational and strategic goals to the security threats. Such adaptability to the changing security environment requires fast and well-founded decisions. Making decisive and difficult decisions requires timely and accurate information and constant strategic analysis, assessment, research, and new perspectives by competent leadership.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2022.96

Data availability statement

All available data are included in the article.

Authors contributions

Both authors contributed equally to the conceptualization, search, data analysis and interpretation, writing, and manuscript editing.

Conflicts of interest

AK is Deputy Editor at this journal but did not participate in any level of the evaluation process.