I. INTRODUCTION

The concept of ‘coloniality’Footnote 1 is an infrequently addressed conceptual frame in mainstream academia,Footnote 2 though it undoubtedly remains a pertinent consideration for developing countriesFootnote 3 who are increasingly becoming incensed by the asymmetrical manifestations of the international investment regime. As these countries have begun to seriously reflect on the disproportionately large number of vague and intrusive obligations that bind them under this regime,Footnote 4 and the impact of the many arbitral claims brought against them on an annual basis by foreign investors from primarily capital exporting countries,Footnote 5 there is a growing sense of urgency to find solutions to international investment law's perceived legitimacy crisis.Footnote 6 Among the countries which have recently joined their counterparts in giving serious contemplation to the coloniality of the international investment regime are Caribbean countries,Footnote 7 most of whom, though relatively new to this regime, nonetheless have over the last 30 years collectively negotiated and concluded over 80 International Investment Agreements (IIAs).

‘Coloniality’ is a conceptual frame first advanced by Quijano,Footnote 8 which has since been developed in the international investment law context by Canadian scholar, Professor Schneiderman.Footnote 9 In his 2022 book, Investment Law's Alibis: Colonialism, Imperialism, Debt and Development, Schneiderman, building on the works of Fanon,Footnote 10 BedjaouiFootnote 11 and Memmi,Footnote 12 interrogates the justifications, techniques and legal forms—‘the matrix of practices’—that arose in the past and that resonate today.Footnote 13 More particularly, Schneiderman unveils the rationales, tropes and methods arising in the past which endure in investment law's domains.Footnote 14

Although colonialism and imperialism are typically used interchangeably, for the purposes of his book, Schneiderman treats the two concepts as distinct, but related phenomena. He defines colonialism as being characterized by ‘foreigners settling in colonies while living in close proximity to, and governing colonial subjects’.Footnote 15 In the contemporary international investment law context, he observes that it is the ‘geographic proximity of investors to host states and their citizens that suggests affinities to colonialism’.Footnote 16 By contrast, he defines imperialism as a system of rule in which metropolitan centres rule at a distance, instructing colonists on how to govern even as their rules do not always fit well with the conditions on the ground.Footnote 17 He observes that imperialism may or may not accompany forms of colonialism, but there is no colonialism without imperialism.Footnote 18

Schneiderman's central argument is that international investment law perpetuates relations of domination and subordination reminiscent of historic colonialism. In his view, ‘colonialism is premised upon the idea that the vast majority of the world's peoples, lands and resources are candidates to be conscripted for the purpose of satisfying the needs of the metropole’.Footnote 19 Given the existence of discursive threads between historic colonialism and the contemporary regime of international investment law—profitability and privilege, a discourse of economic improvement, distrust of local self-rule and the construction of legal enclaves—Schneiderman argues that the ‘relationship between hegemonic capital-exporting States in the Global North and those in the Global South continues to be one of “colonial domination”’.Footnote 20 In short, for Schneiderman, this relationship unveils an ‘embedded logic that enforces control, domination and exploitation disguised in the language of salvation, progress, modernization, and being good for everyone’. In the final analysis, Schneiderman rejects Dolzer and Schreuer's claim that the past is ‘anachronistic and obsolete’Footnote 21 and has little to do with contemporary investment law.Footnote 22

Schneiderman is not alone in interrogating the discursive threads between colonialism and contemporary international law, including International Economic Law. Anghie has argued that colonialism:

far from being peripheral to the discipline of international law, is central to its formation. It was only because of colonialism that international law became universal; and the dynamic of difference, the civilising mission, that produced this result, continues into the present.Footnote 23

Anghie, like Schneiderman, highlights several of the ‘enduring effects’ of colonialism on contemporary International Economic Law, such as foreigners not being governed by the law of the ‘non-European state’, and the rate of compensation payable upon nationalization being the Hull formula.Footnote 24 He contends that these approaches to international law were expressly devised for the very purpose of suppressing the Third World, and expresses great sadness that they continue to animate contemporary international law:

The end of formal colonialism, while extremely significant, did not result in the end of colonial relations. Rather, in the view of Third World societies, colonialism was replaced by neo-colonialism; Third world states continued to play a subordinate role in the international system because they were economically dependent on the West, and the rules of international economic law continued to ensure that this would be the case.Footnote 25

Anghie's criticism of the colonial nature of international economic law, and, in particular, international investment law, resonates with Sornarajah, who sees ‘continuity from the decolonization period through contract-based protection and then to treaty-based investment arbitration’.Footnote 26 In his view, although the use of force and gunboat diplomacy, which were characteristic of the colonial period, are no longer resorted to in contemporary societies, the law has become:

a substitute for the use of force. Gun-boat diplomacy comes to be replaced by arbitration. Yet the rules of the new system may bring about the results desired by power through power-based laws that are sustained by the mechanism of arbitration.Footnote 27

While extolling the virtues of the failed New International Economic Order (NIEO),Footnote 28 Sornarajah expresses concern that ‘the modern international law on foreign investment continues disparities between the developed and developing States, has little ethical merit and cloaks many injustices through rules that promote foreign investments to the detriment of other interests, such as human rights or the environment.’Footnote 29 This view is endorsed in The Misery of International Law, an insightful book in which Sornarajah, Linarelli and Salomon make the compelling argument that international investment law plays an instrumental role in ‘developing biased rules and maintaining asymmetrical regimes through its legitimating function’.Footnote 30 The authors contend that international investment law ‘privileges the rich over the poor (…) promotes human greed over human need (and) is based on domination or coercion’,Footnote 31 which is reminiscent of colonialism. In their view, at the very root of international investment law is ‘coercion in the form of imposition through power, a feature of injustice’,Footnote 32 which existed under colonialism but is ‘now supported through a substantial positive law of treaties’.Footnote 33 For Sornarajah, Linarelli and Salomon, ‘the present system is not maintained through the force of arms but through the sophistry of the law and legal arguments that the system of power provides’.Footnote 34

Meanwhile, Miles endorses the sentiments expressed by Anghie and Sornarajah regarding the discursive threads between colonialism and contemporary international investment law. She argues that the substantive principles and institutional frameworks that underpin international investment law are, in essence, drawn from the colonial period, and continue to this day to reflect those origins.Footnote 35 In calling for a ‘re-evaluation of the modern manifestation of international investment law and its contemporary tensions’,Footnote 36 Miles accepts that the ‘colonial encounter’ is reflected in modern international investment law, which she argues protects only the interests of capital-exporting States and their investors, while excluding host States from the protective sphere of investment rules.Footnote 37 In her view, because the colonial origins of international investment law continue to be manifested in the ‘modern principles, structures, agreements, and dispute resolution systems’,Footnote 38 host States are in a ‘permanent condition of otherness’.Footnote 39 She argues that this is best illustrated by reference to the law's:

sole focus on investor protection, its lack of responsiveness to the impact of investor activity on the local communities and environment of the host state, the alignment of home state interests with those of the investor, the categorisation of public welfare regulation as a treaty violation, and the commodification of the environment in host states for the use of foreign entities.Footnote 40

Like Schneiderman, Miles identifies unequal treaties, extensive concessions, and regulatory chill as key challenges confronting the international investment regime, which necessarily require recalibration.

Building on the conceptions of coloniality discussed above, and, in part Schneiderman's recent monograph, this article seeks to evaluate the experience of Caribbean States through the conceptual frame of coloniality. It argues that, having regard to the provisions of international investment agreements signed by Caribbean States to date, various arbitral awards, State practice and broader prevailing economic and social conditions, there is overwhelming evidence to support Schneiderman's view that the international investment regime is colonial in its nature, content, and practical operation. Due to the relative dearth of international investment arbitration jurisprudence involving Caribbean countries, extra-regional cases are from time to time mentioned to buttress the arguments advanced by the article. These cases serve to illustrate global trends in international investment arbitration which may have implications for Caribbean countries.

II. COLONIAL HISTORY AND INVESTMENT TREATY PRACTICE

History has it that the Caribbean was ‘discovered’ by Christopher Columbus in 1492, albeit that contemporary Caribbean historians have established from historical records the presence of a large Indigenous Indian population in the Caribbean long before Columbus arrived.Footnote 41 In his quest to find a route to the East Indies by sailing West, Columbus made a chance stop on the island of San Salvador, present day The Bahamas.Footnote 42 Columbus claimed the region for Spain and established the first Spanish settlement in the region in the following year in the present day Dominican Republic. It was not long thereafter that other Europeans desired to own their portion of the ‘newfound’ territory.Footnote 43 The Portuguese followed,Footnote 44 and then the English, Dutch and French.Footnote 45 Although Spain claimed the entire Caribbean, the Spanish had chosen to settle only on the larger islands of Hispaniola (1493), Puerto Rico (1508), Jamaica (1509), Cuba (1511) and Trinidad (1530).Footnote 46 Significant amounts of gold were found in the jewellery and ornaments of the Indigenous peoples of these islands which enticed the Spanish to search for precious stones. In their search for wealth to supplement Amerindian labour which had begun to dwindle due to European diseases and overwork, the Spanish began importing slave labour from West Africa.Footnote 47

From the 1620s onwards, other European privateers, traders and settlers established permanent colonies in the territories which Spain had neglected.Footnote 48 By the 17th century, the Caribbean was divided among several European powers. The region's climatic conditions were deemed favourable for agriculture by the European metropole. This saw the early development of the region's agricultural sector, which required a large workforce of manual labourers.Footnote 49 In this context, once indigenous labour was no longer a viable option due to large-scale death caused by diseases brought by European settlers, European superpowers began importing millions of slaves from Africa to support the plantation system which would eventually take hold throughout the Caribbean, producing crops such as sugar and tobacco.Footnote 50

African slaves were brought to the Caribbean from the early 16th century until the end of the 19th century.Footnote 51 By the 19th century, the industrial revolution in Europe was well underway and countries such as France, The Netherlands and the UK required raw materials to sustain this industrial revolution.Footnote 52 Caribbean colonies found their place in this dynamic as designated suppliers of sugar, rum and tobacco products.Footnote 53 These colonies would remain merely suppliers of agricultural produce for their colonial masters until decolonization in the 1960s and beyond, when, due to their favourable climate, they sought to establish themselves as holiday destinations for tourists from Europe and North America.Footnote 54 Today, most of these former colonies are middle income economies, whose economies are inferior to that of their former colonial mastersFootnote 55 and extremely vulnerable to external shocks. This accounts for why these countries are constantly in a frantic search to attract foreign capital.Footnote 56

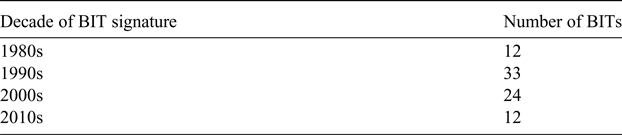

The twelve independent countries that comprise the Commonwealth CaribbeanFootnote 57 have to date signed on to four Regional Trade AgreementsFootnote 58 with Investment Chapters and 81 BITs,Footnote 59 albeit that only 53 of them are currently in force. As indicated in Table 1 below, the majority of these BITs were signed in the 1990s and 2000s. The earliest BIT was signed on 30 April 1982 between Belize and the United Kingdom, while the latest BIT was signed in 2018 between Guyana and Brazil.

Table 1: Decades during which BITs were entered into by Commonwealth Caribbean States

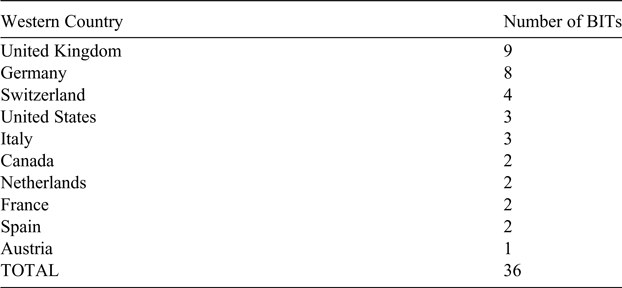

Of the 81 BITs signed by Commonwealth Caribbean countries to date, about half of these were concluded with Western countries. As indicated in Table 2 below, the majority of these BITs were concluded with the United Kingdom and Germany. Surprisingly, notwithstanding its close geographic location and strong trade and foreign policy relations with the USA, the US has only concluded 3 such BITs with Commonwealth Caribbean countries, namely Grenada, Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago.

Table 2: Total Number of BITs between Commonwealth Caribbean countries and Western countries.

Most of the 81 BITs concluded by Commonwealth Caribbean countries to date are older generation BITs, which were negotiated either as part of UNCTAD's mass ‘BITs facilitation events’Footnote 60 or at the behest of Western countries, in particular the United States. For Schneiderman, the ‘negotiations’ that led to the conclusion of these BITs reflect ‘an inequality in bargaining power, conjoined with an institutional incapacity to be heard in international arenas’,Footnote 61 which ‘rendered the voices of poorer States barely heard by wealthier ones’.Footnote 62 Caribbean countries and their Third World counterparts were subject to ‘imposed bilateralism’,Footnote 63 argues Schneiderman. In this regard, the BITs entered into by the Caribbean, ‘though premised on a semblance of equality of bargaining power, barely hid the flagrant inequalities of the relationships expressed in these leonine treaties’.Footnote 64 Vandevelde had earlier shared this view, when he recalled that:

Discussions leading to the conclusion of the Grenada BIT had commenced two years after the August 1983 invasion of Grenada and the restoration of democracy. The Grenada BIT was concluded in a single, hour-long negotiating session that resulted in a treaty identical to the 1984 model negotiating text.Footnote 65

Meanwhile, Alvarez, building on Vandevelde's scholarship, similarly argues that the circumstances surrounding the signing of BITs by Latin American and Caribbean countries, especially in the 1980s and 1990s, were coercive in nature:

For many, a BIT relationship is hardly a voluntary, uncoerced transaction. They feel that they must enter into the arrangement, or that they would be foolish not to, since they have already made the internal adjustments required for BIT participation in order to comply with demands made by, for example, the IMF.Footnote 66

Apart from the coercive circumstances surrounding the ‘negotiation’ of BITs in the 1990s, Alvarez was also concerned about the asymmetrical manner in which many of these BITs were drafted. In this regard, he expressed scepticism as to whether these BITs would operate to advance the interests of developing countries, including Latin American and Caribbean States:

It remains to be seen, however, what will happen in the 1990s and beyond if the investments fail to come or if they come but heavy economic development does not result or if the investors cause more problems (environmental, labor, political) than the investment is worth. Countries are now turning to BITs in hope of economic benefits; if the benefits fail to materialize, there is the danger of a potent backlash.Footnote 67

Alvarez's fear about the potential backlash of the system of bilateral investment treaty regime appears to have, in some respects, materialized three decades later,Footnote 68 as will be discussed below. Section III of this article identifies the rationales, tropes and methods of the contemporary international investment regime which share striking similarities with colonialism.

II. COLONIALITY IN CARIBBEAN INVESTMENT TREATY PRACTICE

A critical examination of investment law through the framework of coloniality reveals that this regime protects investors similarly to how colonial regimes protected Europeans during the colonial era. Caribbean countries have not escaped the contemporary manifestations of colonialism evident in various aspects of international investment law. In this section, the Caribbean's experience in the sphere of international investment law is situated into the enduring features of colonialism as advanced by Schneiderman, namely (a) profitability and privilege; (b) a discourse of improvement; (c) distrust of local self-rule; and (d) construction of legal enclaves. It is argued that each of these features of colonial rule, from a Caribbean perspective, is inscribed in the discourse and practices of the international investment law regime applicable to the Commonwealth Caribbean.

A. Profitability and Privilege

The foreign investment regime in the Caribbean is reinforced by investors’ from primarily capital-exporting countries’ relentless pursuit of profitability. This pursuit of profitability is cloaked in the ubiquitous concept of ‘internationalization’, and is shrouded in lofty ideals around infrastructure development, technology transfer, balance of payments equilibrium and improved economic prospects.Footnote 69 While foreign investors from capital-exporting countries, in the words of the tribunal in Peter Allard v Barbados,Footnote 70 ‘present as person[s] of philanthropic intentions and of enthusiasms’,Footnote 71 it is submitted that such a characterization does no more than obfuscate their true modus operandi. Indeed, for most foreign investors, the Caribbean is merely a ‘voyage to an easier life’,Footnote 72 a life characterized by loose tax regulations; weak environmental, labour, and corporate enforcement capabilities; limited competition between firms; and eager and unsuspecting governments who are prepared to offer them an astonishing range of concessions.

The colonial underpinnings of international investment law are not only evident in regional IIAs, but also in national investment laws. Antigua and Barbuda's Investment Authority Act,Footnote 73 for example, makes the following standing offer of concessionary benefits to foreign investors who make a capital investment of no less than US $3,000,000 and who employ a minimum of five persons who are citizens of, or lawfully resident in Antigua and Barbuda, and who have at least one director or owner lawfully resident in Antigua and Barbuda:

(i) exemption from or reduction of payment of duty under the Customs Duty Act, 1993, the Revenue Recovery Charge Act, 2010 and the Antigua and Barbuda Sales Tax Act, 2006 on the importation or purchase of raw materials, building materials, furniture, furnishings, fixtures, fittings, appliances, tools, spare parts, plant machinery and equipment for use in the construction and operation of the business;

(ii) exemption from or reduction of payment of duty under the Customs Duty Act, 1993, the Revenue Recovery Charge Act, 2010 and the Antigua and Barbuda Sales Tax Act, 2006 on the importation or purchase of vehicles for use in the operation of the business;

(iii) exemption from or reduction of payment of income tax under section 5 of the Income Tax Act, Cap. 212, on the income of the business, for a period of up to 2 years from the grant of the concessions with an ability in respect of that period to carry forward losses for periods of 1 year for each tax year;

(iv) reduction of stamp duty under the Non-citizens Land Holding Regulation Act, Cap. 293, and of stamp duty payable by the purchaser or transferee, and by the vendor or transferor, under the heading “CONVEYANCE or TRANSFER ON SALE of any property” in the Schedule to the Stamp Act, Cap 410, of up to 20% in respect of land and buildings (other than residential premises) used in the operation of the business; and

(v) Exemption from or reduction of payment of tax under section 40 of the Income Tax Act, Cap. 212, for a period of up to two (2) years from the grant of the concession.Footnote 74

In the words of Schneiderman, citing Memmi,Footnote 75 the foregoing ‘astounding privileges’ and ‘host of advantages’Footnote 76 only serve to boost the profits of investors, who seldom allow such profit to find its dynamic in local economies as investors generally expatriate such profits back to their home country or to some offshore jurisdiction with an even looser tax regime.

The Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) has taken note of the ‘very generous’ nature of these concessions, noting that:

Many Caribbean countries provide complete tax holiday for investors in export-oriented activities. The BPO industry is practically exempted from any income tax. Even the extractive industries, which in most other countries are subject to stricter tax regulations often including royalties, are benefiting from incentives in the Caribbean. Bauxite mining in Jamaica is benefiting from tax advantages. Guyana levies a modest royalty (5 per cent) on gold mining and none on bauxite. The only important exception is the oil industry in Trinidad and Tobago, in which private companies (mostly foreign) enter into sharing contracts with the Government, which are negotiated case by case and which provides the Government with substantive revenue. Beyond the generous tax exemptions formalized in the law, Governments add discretionary waivers to individual companies.Footnote 77

(…)

It is clear that the incentives made available in the region are very generous, which is made worse by the fact that conditions for qualifying for these incentives are often not strict (…) Many governments do state their “preferences” with regards to foreign investment, but these are not necessarily hard requirements.Footnote 78

So extensive are these concessions that they can easily be mistaken for those offered in the colonial period. In this connection, Miles’ historical account is instructive:

The rights obtained by concessionaires were often extensive, involving jurisdictional control of substantial areas of land and significant natural resources for lengthy terms in return for payment of royalties. The scope of individual agreements varied, and, although this type of arrangement often concerned only an isolated enterprise, it still effectively involved the transfer of sovereign rights held by the state to the holder of the concession. These agreements were often exploitative, occurring pursuant to unequal treaties or within protectorates, and frequently involved the exertion of pressure from Western states to grant favourable concessions to their nationals.Footnote 79

Insights into the extensive privileges typically afforded foreign investors by Caribbean governments may be gleaned from the case of British Caribbean Bank Limited (Turks & Caicos) v Belize,Footnote 80 which involved a successful claim for expropriation brought against Belize by a British investor, Lord Ashcroft. This case arose under a BIT between the UK and Belize. The Government of Belize compulsorily acquired the claimant's interest in certain loan and security agreements concluded with Belize Telemedia, a telecommunications company registered in Belize, and Sunshine Holdings Limited, a company that held shares in Telemedia. The claimant provided Sunshine with US$10,000,000; it also extended to Sunshine a facility of US$1,000,000. However, before Sunshine and Belize Telemedia Limited repaid the claimant, the Minister responsible for Telecommunications issued an Order compulsorily taking control of the telecommunications sector, including Sunshine and Belize Telemedia Limited. The Order noted that the public purpose was ‘the stabilisation and improvement of the telecommunications industry and the provision of reliable telecommunications services to the public at affordable prices in a harmonious and non-contentious environment’. The claimant wrote to Telemedia and Sunshine, indicating that it considered the loan facility to be in default. A Notice of Acquisition was later issued by the Ministry of Finance requesting that ‘all interested persons who may have claims to compensation for the acquisition of any property specified in the Schedule’ submit claims to the Ministry of Finance. The claimant submitted an initial claim for compensation to the Ministry of Finance, followed by a second claim, but no compensation was provided by the State to the claimant.

The claimant argued that their investment was unlawfully expropriated. In response, the State argued that between 1998 and 2005, the investor's profits were 20 cents for every dollar invested; the claimant was also guaranteed a minimum rate of return of 15 per cent on their investment; and no business tax, customs duties, nor interest of any kind were imposed. In addition, the investor's agreement with the then government stipulated that the State could not regulate the investor's rates, leaving consumers at their mercy. Moreover, all other existing telecoms licenses (except Speednet's) were revoked, and Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP), which would in principle have given consumers the cheapest option, was outlawed. The State also took issue with the fact that the claimant was also able to refuse interconnection to anyone, including internet service providers.

When a new government came to office, they sought to renege on these extensive concessions, arguing that they were reminiscent of the colonial period, and operated to the disadvantage of Belizeans. Belize's then Prime Minister's sentiments are instructive in this regard:

That an agreement so patently illegal, so patently immoral, so patently anti-Belize, should continue to torture us, to bleed us, to subject us to this death by a thousand cuts, cannot for one second more be countenanced. This is our House, this is our country. Here we are masters, here we are sovereign. And with the full weight of that sovereignty, we must now put an end to this disrespect, to this chance taking, to this new age slavery.Footnote 81

The State, after acquiring the claimant's shares, was, however, hauled before an Arbitral Tribunal to defend a claim of expropriation, which it lost on account of its failure to provide adequate compensation.

In the same vein, in Grenada Private Power Limited and WRB Enterprises Inc. v Grenada,Footnote 82 Grenada granted the investor significant import duty and tax concessions, believing that this would incentivize it to develop Grenada's fledgling renewable energy sector. Instead, the investor paid significant sums in special dividends to its shareholders. Interestingly, the ICSID Tribunal countenanced the view of the investor, finding that their ‘investment was intended to make money for the shareholders or investors and they acted accordingly’.Footnote 83 The tribunal also ruled that the dividend policy, even though admittedly not in keeping with their corporate social responsibility, was nonetheless lawful.

1. Asymmetrical dispute settlement regime

The extant international investment dispute settlement regime applicable to the Caribbean also, in the words of Schneiderman, protects investors’ profitability by, at an elementary level, affording investors, and not States, the right to initiate dispute settlement proceedings before tribunals, while permitting only in very rare cases counterclaims brought by host States.Footnote 84 Similar sentiments were expressed in the Caribbean ICSID case of Michael Lee-Chin v The Dominican Republic,Footnote 85 wherein the tribunal accepted the international investment regime's asymmetrical nature in the Caribbean, noting that:

there is only one way to institute investor-State arbitration. Specifically, States have offered their consent in Article XIII, and that consent is perfected when an investor accepts the offer by instituting an arbitration proceeding. This is widely known as anticipated consent or offer of consent to arbitrate. The opposite way is not possible—at least, regarding arbitration—as the investor is clearly not a Contracting Party to the Treaty.Footnote 86

The fact that the tribunal in Michael Lee-Chin felt compelled to question ‘the equality of the parties’Footnote 87 suggests that the asymmetrical nature of the regime impressed upon the panel members’ minds, though evidently not in a significant enough way as to influence the outcome of the proceedings.

Orford's recent monograph, International Law and the Politics of History,Footnote 88 offers an insightful critique of the legitimacy crisis associated with the asymmetrical nature of the system of ISDS. Orford is especially critical of the fact that even where host States successfully defend ISDS claims, there are still staggering costs associated with the arbitral process which operate to the disadvantage of ordinary citizens, who indirectly bear these costs:

Part of the investment law regime's legitimacy crisis flowed from the asymmetrical nature of the system, in which only investors could trigger the dispute settlement process while the costs of the resulting arbitration were borne by both parties. This meant that the ISDS regime was a one-way street, in which the best outcome for a State sued by an investor would be that the government would be held not to have breached its investment protection obligations but still find itself paying millions of dollars to cover the costs of the arbitration. While many States have been willing to gamble on the resulting system, perhaps in the hope that their investors would win against other States often enough to make the overall deal worthwhile, the payoff is less clear for those whose citizens are largely not in the foreign investing class. The net effect of the system is to transfer wealth from States to private actors as the price of regulating in a broad range of areas.Footnote 89

Orford is also critical of the fact that in supplanting domestic judicial processes under the guise of depoliticized international arbitration, the national interests of host States are not always properly accounted for:

The privileging of international adjudication over domestic political processes for resolving conflicts between the protection of property rights and competing values of public health, environmental protection, or survival has inevitably embroiled judges and arbitrators in ideological controversies and political struggles.Footnote 90

That in British Caribbean Bank Limited v Belize, judges at the level of the Supreme Court, Court of Appeal and Caribbean Court of Justice, as well as the London Court of International Arbitration (LCIA), and the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) arbitrators took strikingly different positions on the legality of Belize's alleged expropriatory conduct is illustrative of how the asymmetrical system of ISDS results in costly ideological controversies and political struggles.

2. The guarantee of transfer of returns

Aside from the asymmetrical nature of the dispute settlement regime, the profitability and privilege referred to by Schneiderman which underlies the colonial underpinning of the investment regime is reinforced by various provisions of IIAs, including investor protection standards. For example, Article 8 of the Trinidad and Tobago–United Kingdom BIT, which is mirrored by other Caribbean BITs, provides for the unrestrained transfer out of the host State of returns on their investment:

Each Contracting Party shall in respect of investments guarantee to nationals or companies of the other Contracting Party the unrestricted transfer of their returns and the proceeds from a total or partial sale or liquidation of an investment. Transfers shall be effected without delay in the convertible currency in which the capital was originally invested or in any other convertible currency agreed by the national or company and the Contracting Party concerned. Unless otherwise agreed by the national or company transfers shall be made at the rate of exchange applicable on the date of transfer pursuant to the exchange regulations in force.

While it is clear that returnsFootnote 91 on investments duly belong to investors and that they should, accordingly, not be unreasonably deprived of these returns, it is curious that no such emphasis is placed on investors’ use of at least some of their returns to support the developmental needs of the predominantly vulnerable host States in which they obtain many benefits. In addition, unlimited provisions on returns, especially in older BITs, do not carve out exceptions or reservations to account for situations where a host State has adopted temporary restrictive measures in respect of payments or transfers for current account transactions in the event of difficulties in balance of payments and external financial difficulties or threat thereof, nor where, in exceptional circumstances, payments or transfer from capital movements generate or threaten to generate difficulties for that State's macroeconomic management.

3. The National Treatment standard

The National Treatment (NT) standard also serves, in the words of Schneiderman, to protect profitability and privilege. This standard is premised on the view that if foreign investors are in like circumstances then they should both be treated equally by the host State.Footnote 92 The standard, unless reservations have been carved out, works to buttress the profitability of foreign investors by precluding the host State from taking measures that may advertently or inadvertently support local industries, as seen in Cargill v Mexico.Footnote 93

While it is understood that the NT standard is intended to militate against protectionism,Footnote 94 it also has the (un)intended effect of unfairly placing domestic firms with limited resources in competition with their larger, more resourced foreign counterparts, while proverbially tying the host State's hands by preventing it, on the pain of penalty, from responding in ways that could offer a lifeline to these struggling domestic firms, resulting in ‘regulatory chill’. Indeed, as Linarelli, Salomon and Sornarajah have noted, the violation of rules like the NT standard results in State liability, significant awards of damages, and in turn regulatory chill:

The violation of the rules will create state liability. Often, the damages that are imposed are staggering. As a result, states become constrained by the rules. They act in accordance with the neoliberal prescriptions even where such restraint is not in the public interest. A regulatory chill comes about. The system created is one which can readily further investment protection to the detriment of the public. Thus, the state is pressed to avoid taking measures that are needed to prevent poverty and encourage sustainable social development through distributive methods of taxation, environmental measures, and observance of human rights standards where those might impact on the foreign investors’ profits.Footnote 95

Arguably, then, the NT standard is another colonial tool used to conscript the host State's efforts to protect its local firms, ultimately to the benefit of foreigners.Footnote 96

4. The prohibition of performance requirements

The prohibition of performance requirementsFootnote 97 similarly works to restrict host States’ efforts to protect their local industries. This prohibition, while based on the seemingly noble premise of militating against protectionism, is principally directed at investors obtaining, within host States, unbridled profits. Among other things, the prohibition may preclude a host State from imposing restrictions on the transfer of profits out of the jurisdiction. More than this, even where, objectively speaking, post-admission performance requirements seek to achieve noble causes, namely investors’ corporate social responsibility, investors’ relentless pursuit of profits has generally afforded a privileged position in arbitral practice. In Mobil Investments Canada Inc. v Canada,Footnote 98 for example, the relevant guidelines in question required that a percentage of the investor's revenue derived from oil produced be spent on research and development activities and education and training in the Province. Notwithstanding the seemingly laudable aim that may have been served by the requirement in question, the tribunal ruled against the host State, ultimately finding that such a requirement fell within the scope of Article 1106(1) of NAFTA. This again evidences the coloniality of the investment law regime in that investors’ profit-making is unabashedly countenanced and enforced by the international investment regime, even at the cost of important public interest considerations.

5. Umbrella clauses

The operation of umbrella clauses serves to further illustrate Schneiderman's view that the international investment regime protects profitability and privilege. Indeed, nearly half of Caribbean BITs contain umbrella clauses.Footnote 99 These clauses require host States to comply with any undertaking which they have entered into with the investor,Footnote 100 and afford, as some tribunals have held, investors unparalleled access to international dispute settlement processes if the State is alleged to have breached such undertakings, irrespective of whether these undertakings are purely commercial in nature, and therefore not effected in the State's sovereign capacity.

A typical Caribbean umbrella clause reads as follows:

Each Contracting Party shall observe any obligation it may have entered into with regard to investments of nationals or companies of the other Party.Footnote 101

The coloniality of international investment law, in this connection, is best illustrated by reference to the negative externalities associated with a broad construction of the umbrella clause. In Hamester v Ghana,Footnote 102 for example, the tribunal cautioned that ‘the consequence of an automatic and wholesale elevation of any and all contract claims into treaty claims risks undermining the distinction between national legal orders and international law’.Footnote 103 In other words, for developing countries like those in the Caribbean, the invocation of the umbrella clause by a foreign investor may have a chilling effect on their regulatory landscape, as it has the potential to transform breaches of general or ordinary contractual obligations (purely domestic matters) into breaches of international obligations.

Nevertheless, several tribunals have been inclined to adopt a liberal construction of umbrella clauses. For example, in SGS v Paraguay,Footnote 104 the tribunal, in assessing the umbrella clause found in Article 11 of the Paraguay–Switzerland BIT, considered that there was no rule that governments would only fail to observe their commitments if they abuse their sovereign authority. According to the tribunal, if the host State fails to observe any of its contractual commitments, it breaches the umbrella clause, and no further examination of whether its actions are properly characterized as ‘sovereign’ or ‘commercial’ in nature is necessary. Furthermore, the tribunal deemed as inconsequential the fact that the investor's claims under the umbrella clause could have been resolved by the local courts as provided for in the agreement, instead of arbitration proceedings.Footnote 105

Other decisions also take a liberal approach to the interpretation of umbrella clauses, which may have adverse implications for Caribbean countries in future investment disputes. For example, in Micula v Romania,Footnote 106 the tribunal considered that the umbrella clause in the Romania–Sweden BIT covered obligations of any nature, regardless of their source, whether contractual or non-contractual. Similarly, the tribunal in Khan Resources v Mongolia Footnote 107 noted that the umbrella clause in issue, which required the Contracting States to observe ‘any obligations’, covered statutory obligations of the host State, and, more specifically, Mongolia's obligations laid down in its Foreign Investment Law. In the tribunal's view, a breach by Mongolia of any provision of the Foreign Investment Law would constitute a breach of the applicable umbrella clause. Meanwhile, the tribunal in Greentech and NovEnergia v Italy,Footnote 108 when considering whether the reduction of incentive tariffs breached the applicable umbrella clause, held in the affirmative because, in its view, the umbrella clause was sufficiently broad to encompass both legislative and regulatory instruments.

Given that Antigua and Barbuda, Grenada, Guyana, and Trinidad and Tobago all have National Investment laws on their books that make a standing offer of concessions to investors, and in light of the possible far-reaching implications of the broad construction ascribed by tribunals to umbrella clauses on the already limited regulatory space of these countries, it would not be far-fetched to argue that these clauses form an integral part of the coloniality of international investment law, as observed by Schneiderman.

6. The definition of who is an ‘investor’

Having regard to the loose manner in which an ‘investor’ is defined in several Caribbean BITs, it is arguable that international investment law mainly seeks to protect the profitability of investors. Indeed, barring a few exceptions, most Caribbean BITs merely require foreign corporations to satisfy a simple ‘incorporation’ test.Footnote 109 This liberal approach has posed serious challenges for developing host States, who understandably would wish to resist tribunals’ jurisdiction on the basis that the alleged investor is controlled by third country nationals, or even foreign governments,Footnote 110 or simply does not undertake any substantial business activities in the home State. Despite these objections, however, as many tribunals have held, unless the BIT is specific enough as to the requisite criteria to be satisfied, tribunals will generally apply a simple test of incorporation in determining whether an entity is an investor.Footnote 111 One of the implications of this approach is the near-ubiquitous protection of foreign investors’ profitability and privilege.

In Gambrinus Corporation v Venezuela,Footnote 112 the tribunal countenanced a claim brought by a shell company whose place of incorporation was Barbados. The tribunal rejected the respondent's argument that the applicant had no substantial business activities in Barbados, and was therefore merely seeking to opportunistically benefit from the protections afforded under the relevant BIT. The tribunal ultimately found that, according to the BIT in issue, incorporation in Barbados was sufficient to establish the nationality of a company. Therefore, only in exceptional circumstances, such as fraud or malfeasance, would the tribunal have been prepared to pierce the corporate veil to determine its substantive connection to Barbados. The tribunal, in implicitly recognizing the coloniality of international investment law, pointed out that it is not wrong for a prudent investor ‘to organise its investment in a way that affords maximum protection under existing treaties, usually by establishing a company in a State that … accepts incorporation as a basis for corporate nationality’.Footnote 113 The tribunal's sentiment leaves no doubt that the international investment regime caters to and protects the interests of the ‘prudent investor’ even when their goal is to tacitly circumvent the treaty system to gain ‘maximum protection’, even though their relationship to the host State is nothing more than tenuous. Admittedly, however, Gambrinus complicates the argument around coloniality of investment law, as it involves an investor from a developing country (Barbados) seeking to exploit the system of ISDS against another developing country (Venezuela). Rather than delegitimizing the argument about the coloniality of international law, however, Gambrinus illustrates how the colonial underpinnings of international investment law are so systemic that they even have peripheral effects on South-to-South relations.

Separately, while denial of benefits clauses are found in a few Caribbean BITs, it is, however, instructive to note that recent arbitral practice seems to suggest that a host State cannot rely upon such a provision after arbitration proceedings have commenced. The view appears to be gaining some momentum internationally.Footnote 114 It is submitted that from a Caribbean perspective, this only has the effect of further embedding the privileged status of foreign investors.

Meanwhile, recent arbitral practice on the question of who satisfies the definition of an ‘investor’ seems to reinforce the point that international investment law is principally concerned with protecting profitability and privilege, as argued by Schneiderman. Indeed, not only are direct investors in host States protected by investment law, but so too, as some tribunals have recognized, are indirect investors, whose objective is nothing more than to exploit the regime for profits while maintaining a high degree of remoteness from the host State. In Michael Anthony Lee-Chin v The Dominican Republic,Footnote 115 for example, the majority of the panel found that the claimant was an indirect investor, and therefore could sue the Dominican Republic. In this regard, Schneiderman's assessment of the coloniality of the international investment regime appears plausible, in that the majority of the tribunal in Lee-Chin was principally concerned with protecting the profitability and privilege of the claimant, an indirect investor, even though they recognized legitimate concerns over ‘how that investment was conceived and managed’.Footnote 116

7. The definition of what constitutes an ‘investment’

As intimated earlier, the primary reason foreign investors continue to take the ‘voyage’ to the Caribbean, is to invest in ventures which will generate substantial profits. This unmistakable modus operandi of foreign investors is protected and privileged by international investment law through the very way it defines what constitutes an ‘investment’.

It is now widely accepted that for an investor's investment to gain protection, it must satisfy the definition of an ‘investment’ as contained in the relevant BIT, as well as Article 25(1) of the ICSID Convention, at least in ICSID proceedings.Footnote 117 It is to be noted, however, that Article 25 of the Convention, in imposing jurisdictional requirements, does not specifically define an ‘investment’. For this reason, tribunals have, over the years, sought to rely upon criteria, espoused in Salini v Morocco,Footnote 118 to identify a lawful investment, and distinguish said foreign direct investments from portfolio investments.

Most regional BITs adopt the traditional approach to the definition of ‘investments’, whereby ‘every asset’ is afforded protection. This non-exhaustive definition, as illustrated by Article 1 of the St Lucia-Germany BIT tends to read as follows:

For the purpose of the present Treaty:

1. The term ‘‘investments’’ shall comprise every kind of asset, in particular:

(a) Movable and immovable property as well as any other property rights such as mortgages, liens and pledges;

(b) Shares of companies and other kinds of interest;

(c) Claims to money which has been used to create an economic value or claims to any performance under contract having an economic value;

(d) Copyrights, industrial property rights, technical processes, trade-marks, trade-names, know-how, and good will;

(e) Business concessions under public law, including concessions to search for, extract and exploit natural resources; any alteration of the form in which assets are invested shall not affect their classification as investment.

Due to the all-encompassing definition hitherto outlined, almost any activity can constitute an ‘investment’ under the BIT. However, the Salini test attempts to narrow what can qualify as an investment for the purposes of international arbitration proceedings, requiring that the subject matter represents (1) a contribution of money or assets (2) a certain duration (3) a regularity of return of profit and an element of risk and (4) a contribution to the economic development of the host State. Although there is some dispute as to whether promissory notes may constitute valid investments,Footnote 119 most tribunals have recognized that ordinary commercial contracts for the one-off supply of goods or services are excluded.Footnote 120

The challenge for many developing countries, including Caribbean countries, however, is that some tribunals have been prepared to wholly ignore the Salini criteria or recognize some, but not all, of said criteria, omitting in particular the last requirement of significant contribution to the host State's development.Footnote 121 In RSM Production Corporation and others v Grenada,Footnote 122 for example, the Tribunal, when addressing an alleged breach by Grenada of a Petroleum exploration agreement, considered that flexibility is necessary when applying the Salini criteria, effectively countenancing duration, commitment, risk and regularity of return of profit, but showing scant regard for contribution to the host State's development. Similar views were expressed in Electrabel v Hungary,Footnote 123 where the tribunal held that while the economic development of the host State is one of the objectives of the ICSID Convention, ‘it [is] not necessarily an element of an investment’.Footnote 124

It is submitted that this seemingly pervasive approach in arbitral practice of ignoring investors’ contribution to the host State's economic development is of special concern to Caribbean States, in particular, who are heavily reliant on foreign direct investment for development purposes. That said, given that this criterion is increasingly being omitted from tribunals’ consideration, it is evident that a dangerously enabling environment is being created for investors to profit magnanimously, without the commensurate responsibility of, in accordance with the object and purpose of said BITs and the ICSID Convention, contributing to the economic prosperity of these States.Footnote 125 This should come as no surprise, however, as coloniality dictates that tribunals insist on the regularity of return of profit in the interest of the metropole, while simultaneously ignoring or treating with scant regard the requirement of contribution to the host State's economic development.

B. A Discourse of Improvement

The extant international investment regime applicable to the Caribbean is premised on the belief that investments made by foreign investors in host States inevitably result in sustained improvements in these States. While it is of course true that Caribbean countries have benefited tremendously over the last two decades from investment inflow in the construction, hospitality, tourism, finance, and telecommunications industries,Footnote 126 it is not axiomatic that this in and of itself has invariably resulted in a significant reduction in poverty and unemployment in the region. In fact, ECLAC has commented upon the ‘doubtful success’ of FDI on economic development in the region:

At this moment, there is little hard evidence about the impact of the generous incentives given by Caribbean governments on FDI and economic growth. (…) Goyal and Chai (2008) are among the few academics that have approached the question of tax incentives in the Caribbean. In this case, they analyzed the regime in place in the OECS states. According to the authors, countries forgo some 9½ to 16 per cent of annual GDP in tax incentives, without much noticeable impact. They [sic] authors believe that investors are in fact not very price sensitive at all, and that the removal of generous financial subsidies yields a potential revenue of 7–13 per cent of GDP.Footnote 127

(…)

At a time when many Caribbean countries are reducing fiscal deficits, the incentives awarded to foreign investors have to come from higher taxes to other constituencies. These raise costs of doing business in the economy and may even push many local companies into the informal economy. And the cost of incentives to local economies can go beyond fiscal accounts: the extensive use of import tax waivers for foreign investors has reduced the incentives for local sourcing, reducing the potential benefits to local companies from FDI.Footnote 128

This view of the doubtful success of foreign investment in developing countries is supported by Schneiderman who, citing Memmi, has pointed to the multitude of children in the streets greatly exceeding those in classrooms; the number of hospital beds being pitiful compared to the number of sick; and poverty remains endemic.Footnote 129

Even in those countries where there has been a slight increase in employment as a result of foreign direct investment inflows, an argument can nonetheless be made that foreign investors have created precarious working conditions that are both unsustainable and inimical to the interests of workers and their families. Indeed, because investors’ commitment to the host country is often correlated to the extent of their profit margins, where these margins are narrowed or extinguished, investors are happy to abruptly terminate operations in Caribbean host countries, thereby leaving these economies and the people previously employed by them in dire straits. By way of example, in 2020, operators of Cin Cin By The Sea, Primo Bar & Bistro and Hugo's Barbados abruptly announced the closure of the three restaurants, citing several factors, including rising operating costs, heavy taxes and declining revenue. Many of the workers previously employed with these three businesses did not receive notice nor were engaged to obtain their feedback prior to the closure of these businesses. Overnight, the livelihoods of a significant number of Barbadian workers came crashing down. The rationale? The principal owner invested ‘millions of dollars and none of the shareholders received any money from their investment’,Footnote 130 according to Chief Executive Officer, Joanne Pooler. While a seemingly reasonable explanation, one cannot help but question whether the supposed ‘improvement’ that this investor sought to bring to Barbados was really a farce.

A further argument can be made that, in as much as foreign investment inflows remain an important contributor to development in many parts of the region, these have in many ways been offset by the astonishing privileges afforded to these investors. Indeed, investors’ exemption from or reduction of payment of customs duty, sales tax, income tax, stamp duty and alien land holding duty are not negligible concessionary benefits that have over the years inured to be benefit of foreign investors in the region. In fact, ECLAC describes extensive offering of concessions across the region as ‘leading to a race-to-the-bottom, in which tax advantages offered by one jurisdiction are matched by other ones, in order to continue to be equally competitive’.Footnote 131 Regrettably, in circumstances where Caribbean host States are no longer inclined to honour these previously offered concessionary benefits, investors become incensed, and will pursue redress by any means necessary, even where awards rendered in their favour could have a crippling effect on the economy of these States.

A particularly apt illustration of the unacceptable state of affairs relative to the relentless pursuit of profits by foreign investors arose in Dunkeld International Investment Limited v The Government of Belize (I). Footnote 132 Here, the government of Belize had entered into an Accommodation Agreement with Telemedia. Under this agreement, Telemedia was guaranteed a minimum rate of return, and if the government failed to timely pay any shortfall when this minimum return was not met, the investor could set off this shortfall against taxes or other obligations owed to the government. The agreement also provided for a guarantee on Telemedia's tax rate, a prohibition on the use of VoIP except by license from Telemedia, and an exemption from paying import duties. There was a change in government in Belize, and the new government began aggressively seeking to collect business tax from the company. Telemedia had filed tax returns with the Government in which it had off-set its taxes against the shortfall amount, but the Government refused to accept the returns. The government then issued Telemedia with monthly tax assessment notices, including penalties and interest. Telemedia, in turn, refused to accept the tax assessment notices. In order to compel Telemedia to pay the assessed taxes, the Government issued judgment summonses in the Magistrate's Court. After Telemedia made the requisite tax payments, the National Assembly of Belize passed the Belize Telecommunications (Amendment) Act which sought to acquire for and on behalf of the Government Telemedia for ‘the stabilisation and improvement of the telecommunications industry and the provision of reliable telecommunications services to the public at affordable prices in a harmonious and non-contentious environment’.Footnote 133 The investor initiated claims before local courts as well as before a tribunal alleging unlawful expropriation.

The Government determined that a reasonable compensation for the acquisition of the investor shareholding in Telemedia was BZ$1.46 per share and insisted that the investor withdraw their claims for compensation, and discontinue all arbitral and other proceedings aimed at enforcing said claims. The investor, however, pointed out that the valuation of BZ$1.46 per share was not consistent with the price of BZ$5.00 per share, an offer which was refused by the government after its reacquisition of Telemedia in 2011. The tribunal held that the government did not afford the investor fair market value of the expropriated investment, and awarded damages in the sum of US$96,935,233, an undoubtedly significant amount when one considers that Belize's GDP is only US$1.88 billion.

For the purposes of this discussion, Schneiderman's assessment of the ‘improvement’ rhetoric is particularly apt. While it is clear that the claimant contributed to the improvement of Belize's telecommunications infrastructure, this was arguably counterbalanced by the fact that the claimant in Dunkeld was guaranteed a monopolistic position in the market, and for over 20 years benefited from an astonishing number of concessions, which quantitatively ran into the millions. Indeed, for over 20 years, the investor managed to control 94 per cent of Belize Telemedia Limited (BTL) shares; earned 20 cents for every dollar invested; was allowed to declare in any given year that they had not met a minimum rate of return of 15 per cent, and in turn, simply not pay taxes (business tax and customs duties) until the shortfall had been recovered; required that all other existing telecoms licenses (except Speednet's) be revoked; outlawed VoIP, which allowed consumers the cheapest option; and required that each government department, agency, or associated body, use only Telemedia's services at onerous prearranged rates. These astonishing benefits cannot be justified in the context of the rhetoric on ‘improvement’, but must be critically interrogated for their colonial underpinnings.

Separately, far from ‘improvement’, foreigners, wishing to act as investors, nationals, and diplomats all at once, have forced Caribbean countries to become embroiled in unnecessary diplomatic rows. This arose in RSM Production Corporation v Grenada.Footnote 134 Here, RSM Production Corporation, a company organised under the laws of Texas in the United States, entered into a written agreement with Grenada whereby RSM could apply for an ‘Exploration Licence’ from Grenada for oil and gas. As a term of the agreement, in the event of commercial discovery of oil and gas, RSM was to apply for one or more ‘Development Licences’. RSM notified the Government of Grenada (on 18 July 1996) of the occurrence of a force majeure event; that is, a dispute as to the Government of Grenada's ownership of or control over the petroleum in a portion of the Agreement area. RSM's letter of 18 July 1996 concerning force majeure had the effect of suspending the time within which RSM had to apply for an exploration licence. In other words, RSM, because of the force majeure event, was excused from the performance of all of its obligations under the Agreement.

To facilitate a speedy resolution of the matter so that the agreement could once again become operative, Grenada appointed the Managing Director of RSM, Jack Grynberg, as special envoy, who participated in one preliminary meeting with Venezuelan officials over the maritime issues affecting Grenada. Following this meeting, Grynberg sought to negotiate with Venezuela unilaterally, without express authorization from Grenada. Fearing negative repercussions, internal correspondence between Grenadian officials indicated that such initiatives could not be condoned by Grenada and that Grynberg must function within the Grenadian team. Venezuela objected to his inclusion on the team, expressing concern that Grynberg was attempting to involve the US in the negotiation process. Because of the delicate nature of Venezuelan–US relations, a Grenadian Senator subsequently wrote to Grynberg, on more than one occasion, specifically requesting him not to involve himself or the US Government further in the Grenada–Venezuela maritime boundary negotiations. Grynberg did not comply with the Senator's requests. Instead, Grynberg again unilaterally attempted to resolve the Grenada–Venezuela maritime boundary, this time by negotiating directly with Petróleos De Venezuela (PDVSA), the Venezuelan State oil company. These negotiations were unauthorized and unsuccessful. Grynberg then unilaterally commenced a lawsuit against PDVSA in the US District Court for the District of Colorado in April 2003 in an attempt to pressure PDVSA and the Government of Venezuela into a maritime boundary settlement with Grenada.

When the suit was brought against Grenada by RSM, the ICSID tribunal considered that Grynberg's actions in relation to the Grenada–Venezuela maritime boundary negotiations constituted a breach of RSM's obligations under Article 24.2 of the Agreement. More pointedly, although the agreement mandated that RSM had to take all reasonable steps to remove the cause of the force majeure event and assist in resolving the State's maritime boundaries relevant to the Agreement, RSM, acting through Grynberg, did not act reasonably. Instead, Grynberg's actions substantially hindered Grenada's negotiations with Venezuela. In fact, his

unilateral attempts to negotiate with Venezuela, despite several express communications to the contrary by Grenada, together with his U.S. lawsuit against PDVSA, did not assist in the resolution of maritime boundaries between the two states. Rather, as evidenced by the express rejection by Venezuela of his involvement in the Grenadian negotiating team, Mr. Grynberg provoked outright hostility.Footnote 135

In short, Grynberg's actions provoked ‘embarrassment and diplomatic difficulties for Grenada’.Footnote 136

Meanwhile, Grynberg also participated in Grenada's maritime boundary negotiations with Trinidad and Tobago. As a first step, RSM appointed engineers to give specialist technical advice in relation to the boundary with Trinidad and Tobago. According to the ICSID tribunal, this ‘assistance’ was both counterproductive and amounted to a clear breach of RSM's Article 24.2 obligation.

Grynberg then wrote to the Prime Minister of Grenada stating that RSM intended to commence an ICSID arbitration against Trinidad and Tobago. RSM's intention in doing so was to pressure Trinidad and Tobago into resolving their maritime boundaries with Grenada.Footnote 137 In the light of such an aggressive approach, the Government of Grenada did not approve of RSM's initiatives in regard to ICSID arbitration proceedings against Trinidad and Tobago. RSM, without receiving any response from the Government, nonetheless filed an ICSID Statement of Claim on behalf of the Government of Grenada, RSM and Grynberg against Trinidad and Tobago and Petrotrin, but the claim was later withdrawn, since it was not registered by ICSID's Secretary-General given that RSM had received no authorization from Grenada to file any such a claim.

RSM then prepared a boundary resolution complaint with the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (‘ITLOS’) against Trinidad and Tobago. This claim also was not authorized by Grenada, although Grynberg swore in an affidavit filed with the ITLOS application that RSM was authorized to represent the Government of Grenada for the purpose of instituting proceedings. The claim was never registered with ITLOS. According to Grenadian authorities, all of these actions by RSM had the ‘foreseeable effect of hindering the Government's negotiations with Trinidad and Tobago’.Footnote 138

Having regard to the foregoing, the ICSID tribunal concluded that Grynberg's actions on behalf of RSM in relation to the Grenada–Trinidad and Tobago maritime boundary negotiations had breached RSM's obligation under Article 24.2 of the Agreement in that, although the agreement obliged RSM to take all reasonable steps to remove the cause of the force majeure and to assist in resolving the maritime boundaries, RSM's actions had instead substantially hindered such resolution.Footnote 139 More pointedly, RSM authorized false maps that purportedly favoured Trinidad and Tobago as part of this negotiating process; and RSM then suggested that the Agreement Area be enlarged deliberately to provoke Trinidad and Tobago, a friendly neighbouring State.Footnote 140 Grynberg also aggressively pursued unilateral legal proceedings before ICSID and ITLOS, even threatening Grenada in the process as it would not join him in this strategy. In fact, RSM wrote a threatening letter directly to the Prime Minister of Trinidad & Tobago, riddled with misleading statements, which was widely disseminated by RSM to foreign diplomatic and government officials causing significant embarrassment to Grenada.Footnote 141 In addition to threatening the traditionally friendly relations between Grenada and Trinidad and Tobago, the tribunal recalled that after Grenada had suffered severe hurricane damage only a few years previously, its neighbour, Trinidad and Tobago, had generously assisted Grenada's population with emergency and other substantial aid.Footnote 142 As such, according to the tribunal:

RSM's secretive, unilateral, unauthorised, crude “horse-trading” approach, backed up with wild threats and vexatious litigation if unsuccessful, contradicted the essential principles of maritime boundary negotiations between states. Even though the lack of success in boundary negotiations cannot be ascribed to RSM on the evidence before this Tribunal, the adverse risk to good foreign relations between Grenada and its neighbours caused by Mr. Grynberg's actions cannot by any stretch of the imagination fall under the category of taking “reasonable steps to remove the cause” of the force majeure under the Agreement. An indication of the level of annoyance caused by Mr. Grynberg is the fact that both Venezuela and Trinidad & Tobago expressly asked for him not to be involved in further inter-state negotiations. All of these actions amounted to breaches of RSM's contractual obligation under Article 24.2 of the Agreement.Footnote 143

What is clear from the foregoing is that, far from the investor's action resulting in ‘improvements’ in the host State, RSM's unilateral actions had a significant damaging impact on Grenada's diplomatic relations with its neighbours. Interestingly, also, RSM, through Grynberg, appeared to have usurped the sovereign status of Grenada. Indeed, as the tribunal in RSM itself noted, this usurpation is worrisome given that maritime boundary negotiations are held between sovereign States; such negotiations tend to be strictly confidential and formal in character; and they are conducted by high level diplomatic delegations and specialised negotiating teams. More pointedly, the tribunal explained that ‘any involvement by RSM in such processes, as a private party pursuing its own commercial interests, must be regarded as highly unusual by any ordinary State practice in boundary delimitation negotiations’.Footnote 144 It then went on to reaffirm that any negotiations related to territory or natural resources are of necessity negotiations concerning the vital sovereign interests of States, and that given that ‘territorial sovereignty is one of the most fundamental characteristics of statehood’,Footnote 145 RSM's actions were wholly inappropriate.

Grynberg's actions, which have the real potential to bring Caribbean States to their knees, have since continued, most recently against St Lucia, which once again demonstrates the coloniality of international investment law. In RSM Production Corporation v Saint Lucia,Footnote 146 RSM filed a request for arbitration with ICSID against St Lucia arguing that pursuant to an agreement entered into between the parties, the respondent granted the investor an exclusive oil exploration license in an area off the coast of St Lucia, initially for a period of four years. Subsequently, boundary disputes arose, affecting the exploration area, in particular in relation to Martinique, Barbados and St Vincent, which allegedly prevented the investor from initiating exploration.

Subsequently, the parties amended their agreement to the effect that it was acknowledged that a force majeure situation existed due to the boundary issues and that this situation excused performance of the investor's obligations under the Agreement. Additionally, the Parties extended the duration of the Agreement and the period allowed for performance by the period necessary to solve the boundary issues. In the course of ICSID proceedings, the investor requested an award declaring that the Agreement was still in force, thereby prohibiting the respondent from negotiating with or granting to third parties any exploration rights in the same area or, in the alternative, an award declaring that the respondent terminated the Agreement in breach of the same and obliging the respondent to reimburse all damages incurred in reliance upon the Agreement. St Lucia, in turn, requested an award dismissing the investor's claims and declaring that the Agreement had expired or was at least not enforceable and that the respondent had no obligations vis-à-vis the investor. Moreover, the respondent sought an order obliging the investor to post security for costs.

The Tribunal, by majority, found that the order of security for costs against RSM was necessary to protect a certain right and the urgency of the situation left no room for waiting for the final award. The tribunal was especially concerned by RSM's conduct in the Annulment Proceeding which it had earlier brought against Grenada. It was dilatory in meeting the initial request for advance payment which it was obliged to; of the US$ 150,000 requested, US$ 31,895 was not paid until more than four months after the request had been made. Additionally, RSM never complied with the additional call that it pay US$ 300,000. It did not even pay the US$ 100,000 that it had indicated it was prepared to pay, thereby leading to the discontinuance of the Annulment Proceeding. Moreover, because of the claimant's refusal to meet its regulatory obligations by paying requested advances, ICSID found that it could not even meet actual costs incurred in the Annulment Proceeding. It asked the investor to advance US$ 35,000 to allow recovery of costs actually incurred before the discontinuance, which the investor did not honour, thereby resulting in Grenada having to step in to pay ICSID US$ 31,424.74 to cover these outstanding fees and expenses. This payment was never recovered from RSM. Similarly, in earlier ICSID proceedings against Grenada, discussed earlier, RSM was ordered to reimburse Grenada the cost advances which Grenada had made to ICSID, in the amount of US$ 93,605.62.63, but it never did so.

The Tribunal accordingly concluded that RSM's conduct in the Annulment Proceeding and the Treaty Proceeding demonstrated that it was clearly unwilling or unable to pay the requested advances and, in the Treaty Proceeding, the opposing party's share of advances as awarded by the tribunal. Hence, absent a material change of circumstances, the Tribunal felt satisfied that also in the proceedings against St Lucia, there was a material risk that RSM would not reimburse St Lucia for its incurred costs, be it due to its unwillingness or its inability to comply with its payment obligations. In short, it had been established to the satisfaction of the Tribunal that RSM did not have sufficient financial resources, and its previously consistent procedural history in other ICSID and non-ICSID proceedings provided compelling grounds for granting St Lucia's request for security for costs. Moreover, the third-party funding received by RSM created a strong impression amongst a majority of the tribunal's members that RSM would not comply with a costs award rendered against it.

Another argument advanced by Schneiderman which resonates in the Caribbean context is the view that there is no clear correlation between signing BITs and attracting new FDI. Indeed, St Kitts and Nevis, which has to date not signed any BITs, is one of the region's fastest growing economies, fuelled by investments made principally in the hospitality and tourism industry by foreign investors.Footnote 147 Similarly, Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Grenada, St Lucia and St Vincent and the Grenadines, islands which have, collectively, signed no more than 12 BITs, continue to experience significant foreign investment inflows.Footnote 148 This should not come as a surprise, however, as contrary to the ongoing, unchallenged mantra that the means to achieving improved foreign direct investment is through signing BITs, empirical research has shown that this is tenuous. One researcher, for example, having surveyed a sample of 12 States, found that BITs do not attract ‘development-enhancing FDI’,Footnote 149 while a meta-analysis of existing empirical evidence found that the correlation between BIT ratification and attracting foreign direct investment is ‘economically negligible’.Footnote 150 Meanwhile, an OECD article confirms that ‘the vast majority of the existing studies do not offer a satisfying answer to the question whether IIAs influence capital allocation in treaty partners’.Footnote 151 More recently, Bonnitcha, Poulsen and Waibel concluded that ‘the literature suggests that investment treaties do have some impact on some investment decisions in some circumstances, but they are unlikely to have a large effect on the majority of investment decisions’.Footnote 152

A final point to note is that, far from improvement, FDI may very well result in environmental harm, something which Schneiderman, Miles, and Sornarajah have all cautioned against. In Jamaica, for example, there have been increasing concerns over the significant damage to the environment caused by US and Canadian investors in the bauxite industry. McCarthy's observations are worth noting in this regard:

In 1962, Jamaica gained its independence from Great Britain. But, like emancipation over a century before, this failed to transform the exploitative and stratified organization of Jamaican society. Due to a lack of political imagination, the young country's new leaders were faced with the dilemma of meeting social needs while maintaining positive economic growth. Because of the booming demand for aluminium, one of the first actions of the governing pro-market Jamaican Labour Party (JLP) was to allow heavy foreign investment in the country's resource sector, taking cues from Puerto Rico's ‘Operation Bootstrap.’ This came in the form of allowing five major multinational corporations to buy up nearly all of Jamaica's bauxite resources; four American, and one Canadian. Within five years, Jamaica was the world's largest supplier of the ore, producing 21% of global supply (…) Bauxite mining was hugely degrading for inland Jamaica, particularly in the eastern mountains (…) Clear-cutting a patch of forest and tearing up the earth beneath has completely destroyed whatever ecosystem once existed. But beyond denuding large tracts of rural Jamaica, the processing of the bauxite ore produces much pollution.Footnote 153

In the final analysis, then, to use the words of Schneiderman, BITs signed by Caribbean countries ‘have not brought the kind of investment, including technology transfers and gainful employment, promised by the regime's purveyors’.Footnote 154

C. Distrust of Local-Self Rule