Historians know surprisingly little about the patterns of cattle trade in China. Before the Communist Revolution of 1949 set China on the path to a planned economy, there had been few attempts to estimate livestock populations and little recorded attention to how, how many, or to whom animals were sold.Footnote 1 Absent centralized sources, historians are forced to rely on speculation and episodic evidence.

Yet the importance of cattle to an overwhelmingly agrarian economy like early twentieth century China cannot be overstated. Cattle labor was vital to farming and transport; slaughtered animals produced beef and hides. The conflicting value of living and dead animals created conflict. Aiming to protect agrarian resources, successive Chinese dynasties outlawed cattle slaughter, and castigated the consumption of beef as immoral. During the early twentieth century, reformers began attributing China's endemic rural poverty to the draw off of work cattle to the new and lucrative beef export industry.Footnote 2 In their view, China's “cattle problem” was the result of imperialist predation that allowed stronger neighbors to consume China's productive resources in the most literal sense. Yet, then as now, there were few data to prove or disprove the claim, or to sketch even the basic outlines of China's cattle trade: how animals were dispersed, how large the trade was, how foreign exports actually affected domestic resources, and whether China was a single market for cattle or many overlapping ones.

This article examines why China's pre-1949 cattle trade has for so long remained unseen, explores how it can be studied, and asks what the resulting picture means to Chinese and business history. It does so in five parts. The first argues that the reliance on archives has narrowly defined business history around the firm, rendering invisible other forms of trade, particularly complex systems that lack a dominant central actor. The second shows how the “bottom-up” research tools of social history can be adapted to the purpose of examining China's cattle trade. The third narrows in on the oral testimony of trade intermediaries as the key to understanding the customs, patterns, and interaction of multiple cattle trade systems. Parts four and five divide this complex cattle trade into three types, and from there return to consider the importance of this research to Chinese and business history.

Archive blindness and invisible trades

The field of business history has of late called fresh attention to the interaction of research methods and disciplinary narratives.Footnote 3 It is hardly alone in facing this challenge. Any established area of research creates a loop between preferred sources of information and mainstream lines of inquiry, standardizing internal narratives and blinding itself to new sources and questions. In business history, a preference for government or firm archives both derives from and reinforces a tendency to define the field around top–down, institutional perspectives, writing its way into an implicit or explicit narrative of what constitutes business history, and further what counts as business in a global evolutionary sense.Footnote 4 The challenge, eloquently levied by Austin, Dávila and Jones for scholars to extend their view to the indigenous business histories of Latin America, Africa, and Asia is much more than simply a call for inclusion for its own sake, but rather one to broaden the conceptual scope of business history by taking seriously sources, practices, and narratives that a Western-centered discipline would overlook.Footnote 5

A distinct but related set of issues binds the field of Chinese business history to the problems of modernity. Even taking into account the rich scholarship on Ming and Qing merchant culture and financial practices, the study of Chinese business history is still heavily centered on the politically tumultuous nineteenth and twentieth centuries, often honing in on the emergence of modern institutions and hybrid practices. David Faure focuses on the establishment of China's first joint stock company.Footnote 6 Other studies have examined the new forms that emerged from the meeting of Chinese native financial houses and Western banks,Footnote 7 the development of industry and railways,Footnote 8 and the transformative role of recognizable firms such as Swire & Sons or Jardine Matheson.Footnote 9 The preoccupation with global institutional norms is more than just presentism, but rather follows the tone of the sources, twentieth-century China's own obsession with nationalist modernization, here defined here as the need for China to adopt Western tools and practices under its own power and ownership, rather than as external impositions.

What then is overlooked? Madeline Zelin's excellent study of early-industrial salt production in nineteenth-century Sichuan is a good example of what can be achieved when the written sources of an industry-leading institution, in this case a guild of merchants, are preserved intact, but it also raises the question of how much economic activity is overlooked simply because sources do not exist.Footnote 10 We are not speaking of the post-hoc sterilization of archival sources, but rather the effective invisibility of industries that were too small or too diffuse to leave the sort of records that historians prize.Footnote 11 In other words, the existence of certain archives only serves to highlight the absence of others. Grain prices and sales were recorded because these data were politically significant.Footnote 12 Trade in horses was regulated and thus documented for reasons of military security. Production of books or porcelains left behind account ledgers because these industries were geographically concentrated (in Sibao and Jingdezhen, respectively).Footnote 13 Yet these were likely the exception that proves the rule. While Sichuan's salt makers might be seen as uniquely modern or enterprising, what really sets them apart is that they are visible. Myriad other industries of equal or greater economic importance are harder to find because they were not subject to political surveillance or conducive to centralized record keeping.

China's cattle trade is an example of an industry that is overlooked because it was not recorded in a way that historians can easily access. Combining large and small-scale activity, cattle husbandry in China defies any clear sense of geographic productive advantage. Unlike cattle trade in early modern Europe, the movement of animals across China's landscape was not recorded by local tolls or taxation authorities.Footnote 14 Animals raised throughout the country were traded to different markets whether for labor or for slaughter. The difficulty of seeing cattle slaughter was intentional; cattle slaughter was either taxed or banned altogether, giving producers and merchants all the more reason to keep transactions a secret.Footnote 15 Following disastrous floods across southern provinces during the 1920s, cattle dealers found to be serving the Shanghai beef markets were vilified as “traitorous merchants,” and took to trading at night so as to escape scrutiny.Footnote 16

In the absence of systematic data, basic questions about the importance of cattle as work animals or as food remain unanswered. Many established assumptions derive from episodic evidence, such as the casual observation by an eighteenth-century missionary that the pressures from intensive farming had crowded out livestock, leaving “no manure for the fields, no meat on the tables, no horses for battle.”Footnote 17 Placing the blame on overpopulation rather than resource expropriation reverses the logic of the “cattle problem” but echoes the same untested assumption that China had far fewer cattle than it needed. Studies of animal labor in Chinese rural underdevelopment rely on ethnographic data of a handful of villages that may or may not have been typical.Footnote 18 Even economist John Lossing Buck's massive statistical study (conducted in 1929–1933) of sixteen thousand Chinese farms had surprisingly little to say about livestock populations, except a brief note that “there are few animals per farm, chiefly because the farms are small.”Footnote 19

Social history and intermediation

Given how little is known, we began by seeking to answer the basic questions of the cattle trade: how was livestock husbandry distributed across the land and farmscape? Was it a single trade system or many overlapping ones? How were patterns of cattle trade affected by geography or competition? And, finally, how did cattle trade affect lives and livelihoods? With no centralized sources able to provide a top–down view, we instead started our search from the other direction, using the bottom-up ethnographic tools of social history. This included two components. The first was to broaden our search for written sources outside of industry or state archives and focus instead on compositing episodic glimpses of the trade on the ground in different locations across the country. Comparable to the “cultural turn” away from the sources and narratives of political history, this strategy was more than just a matter of finding a way around the lack of more ideal sources, but rather a “bricolage” technique of assembling large numbers of local sources to logically integrate a wider variety of experiences and perspectives from within the same system. This new strategy did not disappoint. A search of early twentieth century newspapers, local histories, government documents, and ethnographies revealed over one hundred fifty references to cattle trade from all across the country, concentrated in coastal provinces and especially the city of Shanghai.

The second component was to conduct our own oral histories of the trade as it operated in the 1930s and 40s. Interviews are an increasingly important source in business history but, reflecting the emphasis on the firm, they often consist of oral testimony of business founders and leaders.Footnote 20 We spoke instead to a key figure in cattle trade: the go-between who facilitated transactions. Our logic for focusing on brokering comes from the extensive and growing literature on intermediation as a key to understanding complex and multi-step trade systems, by knowing at what points there had been a need for such services as financing, repackaging, warehousing, or personal connections.Footnote 21

Trade intermediation has a long history in China. Commercial functionaries known as zǎng are mentioned as early as the first century BCE. As early the Tang dynasty (618–907), figures known as “in-betweens” (hulang) served as brokers, mediating between buyer and seller, providing commercial information, and acting as contract guarantors, among many other functions.Footnote 22 As China's economy grew increasingly complex, subsequent dynasties eventually came to accept a variety of brokers and to depend on them for such commercial tasks as ensuring tax collection.Footnote 23

Actual intermediation practices varied significantly both by commodity and by local custom. The lucrative coastal tea trade involved a complex chain of functionaries to source the tea, convey it to the coast, purchase it at auction, repack it in barrels, and prepare it for a months-long ocean voyage to Europe.Footnote 24 In her study of the timber trade in mid-Qing Guizhou, Meng Zhang shows intermediaries acting as information brokers, a role that reflected both the high value of the item being traded and the difficulty of communicating across the extensive, complex, and multi-ethnic network that sourced it.Footnote 25 In Tibetan commercial centers like Dartsedo (Kangding), trading houses known as guozhuang mediated between buyers and sellers, oversaw trades, and provided such services as translation.Footnote 26 Spice trade with the Maluku Islands relied on local buyers to bridge language and culture.Footnote 27 In all cases, the role of intermediaries was strictly dictated by custom. Merchant communities in different cities along China's inland Grand Canal had highly individuated customs that shaped how deals were made and how intermediaries interacted with sellers and buyers. More than a matter of mere politeness, adherence to custom marked the intermediary as an insider, one deserving of trust.Footnote 28

Our interviews focused on two types of intermediary: those that bought cattle to resell at a profit, and those that brokered transactions without taking possession of the animal. Both sorts of intermediaries were known variously as jingji, niufanzi, or yaren among other names, and there was no hard boundary between the two sorts of activity. We began by conducting long-form conversational interviews of former intermediaries in Henan and Sichuan and on that basis concluded that intermediation in cattle sales was widely practiced, and thus a viable route for understanding trade as a whole. Upscaling interviews presented a number of logistic difficulties. Our initial conversations had come about as a result of personal introductions, but locating more examples of this very specific persona – former intermediaries, over 75 years old, generally located in rural areas and poorly literate – proved daunting. Even without the impediment of the Covid-19 lockdown, traveling around China to conduct dozens of in-person interviews would have been nearly impossible. Additionally, the initial format of exploratory conversation would need to be pared down into a list of questions that better allowed for analysis and comparison across space.

Our solution was to instead outsource interviews to volunteer research assistants, initially drawn from among our own students and snowballing outward as word of the project spread. We gained access to over eighty former intermediaries, who were interviewed in their own homes and regional dialects, often by a close relative who was also a native of the area. To ensure that our interviewers understood the task, we held numerous online briefings, both to explain the research goals of the project and to teach the craft and pitfalls of oral history. Interviewers were given a set list of questions (Appendix 1, questionnaire), but rather than simply recording answers verbatim, volunteers were instructed to spend at least an hour in conversation, allowing memories to reemerge naturally, and then summarize the key points in their own words. Part of this training aimed to ensure that the interviewee was able to redirect the conversation if the set questions did not match his experience.Footnote 29 Volunteers were able to interact with the project organizers in real time using social media, and each successful interview was awarded a token gratuity of 100 yuan, roughly 12 US dollars.

Combining these two methods, we arrived at over two hundred data points, including 80 remotely-conducted interviews (Appendix 2, interviews), each source presenting a highly localized snapshot of the trade. Combined, the two types of data covered much of the country (Figure 1). Written sources ranged from brief newspaper account of prices or policies to detailed ethnographies of rural markets, an oral history of the one of the main import firms, and Japanese economic intelligence collected in Manchuria and Mongolia.Footnote 30 Our own interviews were more uniformly informative, some volunteering rich detail about the conduct of the trade, cattle prices, and preferences of different types of livestock buyers.

Figure 1. Distribution of text and interview sources.

Three types of trade

Our method for interpreting the data was purely qualitative, approaching each source not simply as a data point but rather as an individuated and potentially unique story. Charting the geography of trade on a map helped us to identify patterns and to visualize the flow of animals across the landscape. Rather than a single direction or pattern, we saw many overlapping ones, corresponding to distinct markets and uses for the animals. We divided these patterns into three types.

Export-driven (persistent supply)

The first trade pattern is the export of grazing animals out of areas of persistent supply. High-altitude pasture in Qinghai and Mongolia were rich with livestock; a report from 1922 estimated 930,000 head of cattle in Mongolia alone. On the grassland, the herds were worth little, a calculation that is reflected in high rates of animal mortality.Footnote 31 Unable to provide fodder or shelter over the harsh winter, herdsmen regularly allowed annual die-offs of animals that could not be brought to market. These routine losses were punctuated by such major mortalities as the decimation of stocks from cold and disease in northern Inner Mongolia in the early 1910s, or the estimated one million cattle lost to rinderpest in Qinghai and Tibet in 1932.Footnote 32

The value of livestock depended on transporting them to market, a complex task that presented high entry barriers of capital and expertise and logistic challenges at the point of purchase, passage, and sale. Importers came from China's agrarian heartland (later joined by Russian and Japanese export buyers) to buy animals at annual or biannual livestock markets, such as the large Ganjuur temple market held each fall in the northern pastures of Hulunbuir.Footnote 33 Buying required significant expertise about the location and timing of markets, the quality of the animals, as well as local languages and customs. Buyers who exchanged livestock for items like cloth, medicine, and tea also needed to understand what sort of products would trade well at any particular market, to source the particular merchandises that pastoralists preferred and respond to changes in supply, such as when the caravan trade of tea through Mongolia was replaced by a sea route through Vladivostok.Footnote 34 Chinese traders active in Tibetan- or Mongolian-speaking areas were generally both bilingual and bicultural, often marrying locally, or keeping dual households. In Mongolia, traders also needed personal connections to estate-holding lamas.Footnote 35

Transporting livestock from northern pastures to markets inside China required experienced operators, logistic support, and significant material resources. Oral histories conducted in the 1960s recall the immense complexity of the Shanxi-based Dashengkui's annual sheep-buying expedition to Uliastai in the northwest of Outer Mongolia. Starting out in Hohhot, this route traversed over a thousand kilometers in each direction and required dozens of men and over a hundred camels laden with trade goods and two months of provisions. Some pastoral trade routes stopped at large clearing markets in Hohhot, Xi’an, Lanzhou, Zhangjiakou, and Shenyang, but large dealers like Dashengkui made their highest profit conveying Mongolian livestock along the “golden road” directly to Beijing, where they had information about market conditions as well as resources to locally graze thousands of animals for months to wait for the best retail price.Footnote 36

Distance trades like the Dashengkui buying expeditions left a record because they were complex and costly. Our oral histories reveal smaller-scale versions of these same patterns. These include conveyance of animals along less-challenging routes like the crossing from Tongliao to Shenyang, from Siping to Yushu, or from Yibin into Yunnan.Footnote 37 Moving at about 45 li (15 miles) per day, these shorter trips took weeks rather than months but still required supplies and drovers who knew the best route, the location of grass and water along the way, and the best market to end the journey.Footnote 38 Herders in Duolun, located on the edge of the Xilingol grassland about two weeks from Beijing, made this trip themselves or hired out the task to low-wage drovers called gazha. Unlike the large-scale annual drives from further away, this fairly easy trip could be undertaken several times per year, each time selling off only a small number of animals.

Oral histories also reveal the importance of husbandry on marginal land throughout China. Places like the sparsely populated mountains of Gansu and Sichuan were inhospitable to agriculture but ideal for grazing and within a few days walk of markets. Others, like the dry hills around Ji’nan and the marshy Yellow River flood plains near Zhengzhou, sat in the middle of farmland. Raising cattle or sheep on marginal land offered a boost to the income of a farming household. Importantly, small-scale husbandry required little resource input besides labor. Many reports confirmed that the relatively easy task of watching the herds was given to children or the elderly. Farmers near the far southwestern city of Dali raised cattle collectively, entrusting mixed herds to an older villager who went off to graze the animals for weeks at a time among the nearby foothills of Cangshan. Proximity to market made selling the animals easier. Farmers in central Shandong supplemented their income by raising sheep and cattle in nearby hills, walking the animals to nearby markets in Tai’an and Linyi and simply taking home any that were not sold. Requiring few resources and bringing in an important sideline income, this sort of small-scale husbandry was found almost everywhere.

Import-driven (persistent market)

The second pattern is the inverse of the first: trade systems that were driven by focused, and often very specific demand. Qing-era Beijing was one such source of demand. Live cattle were driven daily into the city. A significant number of animals were required for sacrifices in the city's temples, but most were sold for meat. Although the Qing court itself did not eat beef, the populace of Beijing certainly did.Footnote 39 One 1926 survey shows Beijing families purchasing about 6.4 jin (3.2 kg) of meat each month, about one-quarter of which was beef.Footnote 40 Multiplied by the city's two million residents, that small figure quickly adds up to at least forty thousand cattle per year. The business of buying and butchering cattle was controlled almost solely by Beijing's Muslim population, centered on the city's aptly-named Cattle Street where, as an early Qing source described it, “hundreds of cattle and sheep [were] slaughtered each afternoon.”Footnote 41

The emergence of overseas markets during the early twentieth century introduced demand for high-quality beef cattle. Compared to domestic markets, lucrative new export markets in Hong Kong, Russia, and Japan paid significantly more for Chinese beef cattle, but these markets also demanded investment in higher quality animals. For example, cattle from Shandong were initially shipped through Yantai to Siberia. After the Great War, the center of export shifted decisively to Qingdao.Footnote 42 Destined for the Japan market, cattle slaughtered in Japanese-occupied Qingdao had been crossbred with imported Simmental and fattened on local farms, and as a result were twice the price and size of those slaughtered in interior cities like Changsha and Nanning (Table 1).Footnote 43 By the 1920s, Qingdao slaughterhouses were sending between 50 and 60 thousand head of these high-end beef cattle per year to Japan.Footnote 44 Even as other cities began to compete for market share, as late as 1949, 75% of Qingdao beef was being shipped to Japan.Footnote 45

Table 1. Cattle price and size in seven cities, 1933–1934

Source: Shiyebu Reference Shiyebu1933–1934.

This highly specialized chain relied on a coterie of expert buyers to source high-quality cattle from local markets. Buying at this end of the market was an expert task; it required a discerning eye for the quality and health of the animal, as well as experience in knowing which feeders were reliable and which markets would provide a regular supply. Buyers had to know the signs of disease. Modern slaughterhouses had high sanitary requirements, and incoming animals were checked by veterinarians on site. Buying an infected animal could result in a loss not only of the cost of the animal itself but potentially of other animals penned with it.

Purchasers often worked within a sourcing catchment, buying animals at large markets served by railways. Qingdao buyers bought from feeders at markets along the railway and especially at the large cattle market near Ji’nan, to which animals were driven in, sometimes hundreds at a time, from neighboring Hebei, Henan, and Jiangsu provinces.Footnote 46 Animals that were not sold to Qingdao found their way to other nearby markets.Footnote 47 Ji’nan was also supplied by professional dealers who fanned out across smaller markets buying up 20–30 animals at a time to resell for a profit. In local usage, these buyers (niufanzi), were terminologically distinct from the cattle brokers (jingji) who facilitated transactions between individuals.Footnote 48

Interviews from Shandong depict the purchase process in detail.

You would sell as far as Ji’nan. Before 1937, you would sell [cattle] to the Japanese; this was called “earning the foreigner's money.” The Japanese paid a lot more; you could get ten times the profit. They would take the animals away and vaccinate them.Footnote 49

I was still young when the Japanese were here. They were here for eight years, and they had a railway line. At that time, the Japanese came here to buy beef and to buy cattle. It was all Japanese currency; that's what people earned and spent …. Nobody wanted the Guomindang [Chinese regime] currency; they wanted Japanese currency.… They didn't need a broker; all the trade was done right here. The Japanese would buy the cattle and load them onto trains.Footnote 50

I recall two or three years that the Japanese were here. They came to Ji’nan to buy cattle and ship them off to Japan. Shipped by rail to Qingdao and then loaded onto ships. They had Chinese buyers buy up big cattle and then take them back for slaughter. The Japanese were buying cattle for more than seventy years.… They used Chinese brokers to buy; they set a price per pound and bought cattle live. I forget how much they paid, but we all used their currency. Everyone sold cattle to the Japanese, and they paid well. If they didn't pay, who would sell to them? It was a public business, not theft, and it was Chinese people who ran it.Footnote 51

Other beef markets had distinct catchments and standards (Figure 2). The slaughterhouses in Harbin, which supplied cities such as Vladivostok, bought beef cattle at Qing’an and Lanxi north of the city, as well as at markets like Qiqihar along the China Eastern Railway. Domestic markets were less discerning. Even Shanghai and Guangzhou, both wealthy cities and major consumers of beef, slaughtered relatively small and lean animals. Situated between Qingdao and Shanghai, the city of Xuzhou fed into both markets, the higher quality animals going to the former, and the second quality to the latter.Footnote 52 The Shanghai market was also more politically complex. Unlike Japanese-controlled Qingdao, the area around Shanghai was under the control of Chinese officials who were able to force the closure of cattle markets feeding into the city. Such measures could slow commerce but not stop it. Cattle still reached Shanghai, including animals bought from famine-stricken farmers in Jiangsu and Zhejiang.Footnote 53 Further south, possibly because the relative value of livestock trade was more pronounced, cattle driven into Guangdong from nearby provinces were often accompanied by armed guards.Footnote 54

Figure 2. Map of trade routes as described by sources. This map is a simplified composite of the long-distance trade routes described in interviews and textual sources. Locations described as trade markets turned over live cattle, urban markets were generally for beef consumption or export.

A different sort of specialized cattle market arose from the demand for fighting animals. This market was served by expert buyers who fanned out across central China looking for promising animals to ship to the mountainous southern provinces of Guangxi and Yunnan, where bullfighting was (and remains) a local custom.Footnote 55 This network of specialized buyers reached as far as Hunan, Zhejiang, and Jiangsu.Footnote 56

What about draft animals? Many of the animals that eventually ended up being used on farms were raised in nearby marginal land, particularly mountains. This model of exchange was reported between Wan'an and Jiangxi,Footnote 57 and from Wuping to Guangdong.Footnote 58 The lush Sichuan basin imported work cattle from its surrounding highlands, as well as from nearby Yunnan and Guizhou.Footnote 59 In contrast, it seems that pastoral cattle did not end up on farms. Two reports conveyed the opinion that animals raised on pastures did not adapt well to work life. Mongolian cattle were neither as strong nor as well-tempered as those locally raised. Moreover, cattle raised on the lye grass of the pastures could not eat straw without becoming ill and weak.Footnote 60 This is perhaps our first clue that specialized sourcing was not restricted to exotic demand but was in fact the norm across China's cattle market.

Circulatory

The first two trade systems describe prevailing conditions, either the push of excess supply or the pull of a specific sort of demand. On the large or small scale, these trades were run by professionals. But in numeric terms, the bulk of cattle trade undoubtedly consisted of work animals circulating within agricultural regions and among farming households. For farmers, buying or selling individual cattle was a way of balancing needs and resources, adding a new animal to replace lost labor, selling a weaned calf, or sending off an old work animal for slaughter. Other than buying an animal outright, farmers could borrow a bull to stud, rent a team of oxen for the spring plowing, or purchase a work animal in the spring and then sell it after the autumn harvest, incurring a loss but still saving the cost of caring for the animal over the winter.Footnote 61 The difference between directional and circulatory trade is evident in the sources. Whereas our written sources often depict trade moving stably in one direction, out of areas of specialized production or into sites of industrial draw off, interviews of intermediaries generally describe the geography of cattle trade either as two-way exchange or in terms of a sphere (quanzi) of activity. In densely populated areas like the North China Plain or the Sichuan Basin, interviewees estimated this sphere as ten to twenty kilometers from home. In the mountains of Gansu, Guizhou or Western Sichuan, it was one-hundred to one-hundred and fifty kilometers.

Circular cattle exchange required the services of a broker. For most farm households, buying or selling a draft animal was an important but infrequent event, one that represented a significant investment and significant risk. The buyer needed to be sure that an animal for sale was as young, healthy, and docile as promised, that the price was appropriate, and that the animal had not been stolen. While experienced professional buyers could make such judgments on sight, a farmer conducting the same transaction (either buying or selling) was at a significant disadvantage and relied on the experience of a third party as a go-between. Our oral histories confirm that in cattle sales in local markets across China, some sort of intermediary was almost always present to help negotiate the price and to guarantee the quality and provenance of the animal being sold. In return for this service, the intermediary would receive a small payment.

Within this framework, there was some customary variation in how brokers were known and how they worked. Across north China, most respondents called them yaren and jingji, but others reported terms including niufanzi (a term already seen, but with a different meaning), niubianer, hang laoban, and lashou. Customs surrounding the activities of the broker varied slightly from place to place. A former broker described the process in southwest Henan: the seller brought the animal to a village market and left it tied to a post with a written price. The broker would bring a buyer and serve as a go-between to negotiate the price to a mutually acceptable figure. In this process, buyer and seller did not meet. The broker negotiated with each one in secret, out of earshot of any third party. Intermediation grew more important as the radius of trade activity grew larger and less personal. Intermediaries kept appraised of prices in nearby markets and maintained a local information network that allowed them to match sellers with the specific needs of buyers. In the Sichuan Yibin market, cattle trade was conducted inside the tea house, where the broker was on hand to match buyers and sellers. With an introduction, the buyer would meet the broker at the market to negotiate the final price. In a similar way, the role of the intermediary was one of human relations. One former broker from Tai’an described the role of the broker in the process of courting the two sides:

There were baozi [steamed buns] and tea stalls in the market. The broker would bring the buyer to one of these places to eat and drink and then go and carry out the trade on his behalf. The broker dealt individually with the buyer and seller, quoting a lower price to the seller, and a higher one to the buyer. The broker was then able to keep the difference.Footnote 62

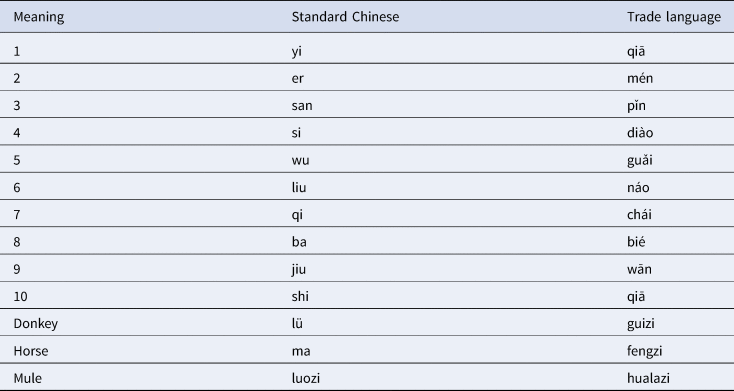

Intermediaries found ways to make themselves indispensable to the process of trade. Respondents often said that brokers would “wear long sleeves,” a reference to the language of hidden hand signals that two parties used to negotiate prices inside a sleeve or under the cover of a cloth. In addition to this silent hand language, there was also a rhyming language (jiangga) that was used only between professional livestock dealers. This trade language (shown in Table 2) was designed to be unintelligible to outsiders. One former broker described it: “You go to set a price, ‘how much is this cow?’ ‘bieziga, you want it or not?’ A broker knows that language and understands what that means. Then he’ll take out a piece of cloth to cover their hands, and they'll work out a price.”Footnote 63

Table 2. Sample of trade language (jiangga) used by Shandong livestock dealers

Source: Report 5, Report 27.

Almost every report emphasized that private cattle sales effectively had to pass through the hands of the middleman, or at least that using a broker made the process much easier. Using the local term for brokers, one 86-year-old former trader from Anhui remembered: “The laoban set the price; without him it was not possible to trade.”Footnote 64 Claiming that most of his trade consisted of “low-life ruffians,” another former broker volunteered more detail about how the intermediary could make himself indispensable:

Some people didn't want to use a broker. But then during the sale the broker would appear and “discover” that the animal had some defects, that it wouldn't do farm work, or that it refused to eat. These were all just to frighten the buyer.… Even if the two parties came to an agreement on their own, the broker would still come and take a cut. In the marketplace, buyers could not simply make their own deals.Footnote 65

Besides brokering a price, intermediaries offered other services. Buyers rarely carried large amounts of cash to market and would often pay a deposit and rely on the intermediary to advance or guarantee the remainder.Footnote 66 Some also brought their own animals to market, showing that the line between cattle broker and merchant was not absolute.

There were exceptions. Some reports noted that a broker was not needed for sales between friends or neighbors in the same village.Footnote 67 Brokers were not used in far northern locations like Tongliao or Jilin, where cattle were plentiful, and even farming households knew well how to judge the health and worth of an animal. In these areas, niufanzi acted as buyers, not intermediaries. In the Jilin city of Yushu, niufanzi went house to house buying cattle to sell for a profit at the local market.Footnote 68

The main exception to the rule of intermediated trade was when animals were being sold for slaughter. Here, we are speaking not about value-added export chains, but rather the routine sale of old or injured work animals to a village or market slaughtering grounds. Reports were divided on whether brokers were used at this stage. The slaughterers themselves had no expectations about the age or good temper of the animal and knew well how to visually judge an animal for weight and overall health – the only things that mattered at that stage. In some cases, dealers might travel to less-accessible villages collecting cattle to deliver for slaughter, but most said that when the time came, farmers simply brought their own animals directly to the meat seller.Footnote 69 In places where the ban on cattle slaughter was strictly enforced, a broker might be called in to certify that the animal had not been stolen and that it was in fact too old or otherwise unsuitable for farm work.Footnote 70

Reports also confirmed that slaughter was the most common end to the lives of domestic cattle. While a few locations near mountains or open grassland reported the custom of rewarding old work animals by returning them to the wild, most of our answers confirmed that cattle who had no labor value were destined for slaughter. This fact attests to another way that a lack of written sources obscures an important facet of cattle in rural China – their value as food. China's annual cattle slaughter during the 1930s has elsewhere been estimated at about 14.5 million head.Footnote 71 This number dwarfs the statistics kept by the new urban slaughterhouses. According to the 1934 slaughterhouse survey, cattle slaughter in the three largest cattle cities, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Qingdao (Beijing was not included in the data), together account for just under a hundred and fifty thousand head, less than one percent of this figure. The overwhelming majority were slaughtered in informal and untaxed markets – “cow sheds” and village squares. Just as with the cattle trade itself, the historical record of animal slaughter shows only the tiniest fraction of actual activity.

Use of intermediation

Returning to the question of sources, we ask what unique perspective our ground-up social history of intermediation might add either to the sort of firm archives favored by business history, or the quantitative approach favored by economic historians. At first glance, the absence of a single firm that dominated the trade, or of any records comparable to the toll tallies that Blanchard used to track cattle drives across early modern Europe appears as a significant disadvantage, and indeed in the absence of on-the-ground testimony to the contrary, it would be all too easy to interpret the absence of these sorts of easily accessible data as proof of the lack of trade activity.Footnote 72

Initially brought to bear simply as a way to circumvent the lack of traditional sources, the unique advantages of ethnographic and social history methods soon became clear. First, the use of local sources and interviews expanded our geographic base from center to periphery. Like any centralized source, firm archives necessarily draw our attention to the perspective of the people making decisions, and the places where those decisions are made. Without stretching the analogy too far, firm records mirror colonial archives in the sense that they portray a world as refracted through a geographically centered set of needs and perspectives.Footnote 73 Localized sources, particularly when collected on a wide scale, physically decenter the accretion of knowledge, in this case to include the remote regions where pastoralism was a way of life, rather than focusing solely on locations like Qingdao or Shanghai, where commercial activity was most visibly concentrated.

Second, the bottom-up viewpoint of social history reveals perspectives from across the entire production system rather than focusing just on the buying firms. Interviews place the cattle trade in the context of a large and complex agrarian economy, showing how ownership of draft animals was meticulously tuned to the needs of individual farms. Farmers could hire an animal by the day or season, or own one jointly with neighbors. Many emphasized that ownership was common and that all or nearly all families kept a cow (specifically a female, since these were more docile).Footnote 74 Others placed the rate of ownership at 40 or 60 percent.Footnote 75 Those who did not own an animal could buy and raise one collectively, three or four families each putting in for one “leg” of the animal, and claiming rights to a corresponding amount of labor.Footnote 76 Beyond the cost of purchase, other reports emphasized that the constraining factor on ownership was the labor needed to feed and care for the animal.Footnote 77 Poor families might agree to “fen kan,” raising a neighbor's calf and using the animal's labor for a time and splitting the proceeds when it came time to sell.Footnote 78 Renting and borrowing animal labor was also common. The cost of hiring a team of oxen could be figured by day, or by area of land worked. In other cases, one day of animal labor could be traded for three days of human labor. Still, cattle weren't used everywhere. In the smaller fields surrounding Ji’nan, horses and nimble donkeys were preferred. Water buffalo are much better suited than dry land cattle to working in flooded rice fields. In rice-growing villages such as Qidong near Shanghai, cattle were used not for agriculture, but for transport.

The keen accounting of marginal cost and utility that occurred within every farm household also explains why China's livestock production was not separated into the distinct pastoral and agrarian spheres that historians sometimes imagine. Even the richest farmland would still have small patches of hills or scrub that were better suited to grazing than growing crops, and these areas would in effect become miniature pasturelands, specializing in the production and sale of ruminant sheep and cattle. This dispersal of resources is why China's cattle trade had no clear Smithian geography of productive advantage, despite the presence of rich grazing land all along the northern frontier.

The oral histories of intermediation show how a diffuse trade can be bound together in the absence of a central actor. Lacking the organization of a trade guild, intermediaries nevertheless retained a network of information that kept them abreast of prices in nearby markets and opportunities for profit by arbitrage in more distant ones. They remained connected to clients through professional reputation and adherence to custom.

They also show internal differences, highlighting the distinct ways that services added functionality and value within a complex web of market ties. The starkest difference is that between two types of intermediation: The first sort is the expert services required by the distance import and export trades, the specialized systems that drove pastoral herds to Beijing or sourced fattened beef cattle for the Japanese slaughterhouses in Qingdao, as well as simpler and more local variations of these same trades. The second sort are the brokers that facilitated transactions in the circular trade of cattle between farming households. Our oral histories confirm that this latter sort of intermediation was extremely common. Of eighty interviews, only a handful said that cattle trade was possible without a broker. Apart from local custom, the reason is simple: Brokers lessened the risk inherent in cattle sales, which were infrequent, high-stakes transactions. Despite the occasional portrayal of intermediaries as “ruffians,” every broker relied on local reputation to make a living. As in any trade characterized by asymmetric information, hiring a broker was fundamentally a matter of outsourcing trust.

Finally, qualitative interviews, even abbreviated ones, provide a depth and richness for which no amount of quantification could substitute. Question 2.6, “How were old cattle disposed of?” was intended to track whether cattle were locally slaughtered for meat, on account of a strong cultural predilection against eating beef.Footnote 79 Phrasing this as a simple yes-or-no question about beef consumption would have produced clear and chartable data, but it would also have led us to miss out on vital substantive details about the morality of animal slaughter, the role of Muslims in the slaughter and sale of beef, and the different sorts of time and effort spent preparing beef cattle for foreign versus domestic markets.

Conclusion – cattle trade and China's business history

This study set out with two goals, one empirical and one methodological. Broadly, these speak to the concerns of China historians and business historians, respectively.

For the first, the goal was to sketch out and explain the significance of China's important but unseen cattle trade. Addressing long-standing questions about imperialism and capital investment in the rural economy, we show that China's “cattle problem” was unlikely to have been the result of the extractive export of beef cattle, and indeed perhaps was not such a problem at all. To the contrary, the many markets for cattle presented immense economic opportunities for pastoralists and exporters, as well as for farm families to make a side income by raising cattle using marginal resources. The circulatory trade of work animals that continued out of sight of regulators shows that draft animals were present and moreover that animal labor was used efficiently. This image runs counter to a prevailing understanding that underdevelopment in early twentieth century rural China was due to a fundamental lack of resources, regardless of whether driven by external expropriation or the excess supply of human labor that subverted improvement or capital accumulation.

For the second, we explored how business history can employ the tools and concepts of social history to widen its scope into other areas of commercial activity. Historians of Chinese business have fruitfully explored firms, institutions and industries, both before and after the moment of Western encounter, but by relying on the sort of political, firm or industry archives that define business history as a field, this sort of research runs the risk of finding what is already known, reducing Chinese business history to a search for protocapitalist analogs or a trajectory of increasing Westernization. Such bottom-up methods as oral history are not just a way to circumvent the problem of missing archives, but rather a glimpse into the world of economic activity that lies outside the firm. The more panoramic view explored here combines the individuated perspectives of pastoralists, farm households, beef sellers and consumers to reveal a trade system that operated efficiently as a web of small-scale actors. It did so by combining the perspectives and tools of social history, notably the collection of oral testimony, with an important insight from business history – the vital role of intermediation as the key to understanding a complex trade system.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1479591424000111.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Beijing Gaojingjian 高精尖 scholarship fund - Cultural heritage and cultural transmission project 00400-110631111. Authors extend their thanks to the former traders who shared their knowledge and to the student volunteers who helped us to collect and record it. Yin Rushuai and Adam Frost provided invaluable insight on earlier drafts.