Studies of linguistic change in progress over the past five decades have told us more and more about the mechanism of change as it occurs across generations. The chief link between the history of a language and its use in everyday life is the faithful transmission of the vernacular from parents to children in successive generations (Labov, Reference Labov2007). Changes from below, which spread within the local community, are acquired by children in adolescence (Labov, Reference Labov2001). This process has been documented in a variety of urban and rural communities (New York City: Labov, Reference Labov1966 [2006]; Panama City: Cedergren, Reference Cedergren1973; Cairo: Haeri, Reference Haeri1996; Martha's Vineyard: Labov, Reference Labov1963; Philadelphia: Labov, Rosenfelder, & Fruehwald, Reference Labov, Rosenfelder and Fruehwald2013). On the other hand, the larger-scale history of many languages shows a number of changes from above that spread across local communities in a process of diffusion, where the new forms are adopted first by adults with varying degrees of precision. Recent studies of change in progress have included a number of examples of such diffusion in the broader history of languages, as for example, the spread of consonantal /r/ across the r-less dialects in the Atlas of North American English (Labov, Ash, & Boberg, Reference Labov, Ash and Boberg2006:ch. 7); Trudgill's (Reference Trudgill1974) study of the lowering of short a across the Brunlanes peninsula in Norway; Friedman's (Reference Friedman2014) study of the diffusion of the Northern Cities Shift in the St. Louis corridor.

To understand this process, we have to know more about the people who transfer and communicate the new forms to their community: where they are located; what makes them eligible for such a role; and how the older system changes with their input. The change from above to be examined here is the adoption of the new quotative be like as the dominant form for reporting speech acts, a change that began in the late 1970s and has developed in Philadelphia in a pattern very similar to that found in the rest of the English-speaking world (Blyth, Recktenwald, & Wang, Reference Blyth, Recktenwald and Wang1990; Buchstaller, Reference Buchstaller2014; Charity & Sanchez, Reference Charity and Sanchez1999; Cukor-Avila, Reference Cukor-Avila2002; D'Arcy, Reference D'Arcy2012; Ferrara & Bell, Reference Ferrara and Bell1995; Rickford, Buchstaller, Wasow, & Zwicky, Reference Rickford, Buchstaller, Wasow and Zwicky2007; Romaine & Lange, Reference Romaine and Lange1991; Singler, Reference Singler2001; Tagliamonte & D'Arcy, Reference Tagliamonte and D'Arcy2007, Reference Tagliamonte and D'Arcy2009; Tagliamonte, D'Arcy, & Rodríguez Louro, Reference Tagliamonte, D'Arcy and Rodríguez Louro2016; Tagliamonte & Hudson, Reference Tagliamonte and Hudson1999).

CHANGE FROM ABOVE: THE NEW VERB OF QUOTATION

The change from above that we will examine is the replacement of a very small part of the English language. The primary device for introducing reported speech, using forms of the verb say, has been replaced by inflected be plus like.

(1) He said, “Who are you? → He was like, “Who are you?”

The change is salient, frequent in everyday conversation and is dominant in every part of the English-speaking world that has been investigated. Table 1 lists some of the linguistic reports of this variable over the past two decades.

Table 1. Studies of be like

Given the speed and extent of the shift, it offers an opportunity for convergence of the observations of many linguists engaged in the search for a better understanding of linguistic change.Footnote 1 Moreover, it leads to a new understanding of the differences between transmission and diffusion. Labov (Reference Labov2007) portrayed transmission across generations as the primary mechanism of linguistic change, in which children first acquire and then increment their parents’ forms. But for this and other large-scale changes, we see that for most speech communities, the initial event is diffusion of the new forms into the community by adults who have acquired it from elsewhere, followed by transmission and incrementation in the next generation.

It is generally agreed that the new quotative must have originated in some part of the United States, as yet unknown.Footnote 2 Many of the published reports address the question of the mechanism of diffusion by which the new verb of quotation has spread from one city to another. Tagliamonte et al. (Reference Tagliamonte, D'Arcy and Rodríguez Louro2016) considered an explanation based on the emergence of the youth culture and travel tourism in the 1960s, but ultimately rejected such an accounting. They concluded that the new verb of quotation is a linguistic “Black Swan” (Taleb, Reference Taleb2010): “Its simultaneous, instantaneous, parallel development, in multiple urban locations, at the same time, from a novel collocation within a coherent system, could not have been predicted” (Tagliamonte et al., Reference Tagliamonte, D'Arcy and Rodríguez Louro2016:842).

The unpredictable character of the new verb of quotation will not be the focus of this discussion, but I will rather attempt to trace the path of innovation across speech communities. Be like will be seen as a linguistically minor event but indicative of the sociolinguistic forces that shape the future of the language. I will take advantage of a unique series of recordings of Philadelphia speech, across many neighborhoods, extending year by year before and after the change began, as a contribution to the understanding of how this change was initiated and how the dominant form be like fits into the transmission of information in everyday life.

THE PHILADELPHIA NEIGHBORHOOD CORPUS

We will trace the diffusion of the new quotative with the help of the Philadelphia Neighborhood Corpus (PNC), which provides a closer view of this process than we have had so far. The PNC was generated by a series of 90 neighborhood studies by groups of students at the University of Pennsylvania in LING560, The Study of the Speech Community, yearly from 1973 to 1990, and biyearly from 1992 to 2012. In these studies, students entered the neighborhoods, observed the settings in which conversation takes place, made contacts with neighborhood residents, and interviewed members of the various social networks that they found in the neighborhood (Labov, Reference Labov, Baugh and Sherzer1984). From the total of 977 recorded, the PNC contains transcriptions of 365 interviews for the years 1973 to 2012. To complete a representative sample of neighborhoods by social class and ethnicity, 35 interviews were added from the study of the leaders of linguistic change in Philadelphia in 1973 to 1975 (Labov, Reference Labov2001), and 13 interviews from the study of African American speakers in Philadelphia in 1980 to 1981 (Labov & Harris, Reference Labov, Harris and Sankoff1986). Vowel systems were analyzed by FAVE (Rosenfelder, Fruehwald, Evanini, & Yuan, Reference Rosenfelder, Fruehwald, Evanini and Yuan2016).

Figure 1 shows the age and year of interview for the PNC speakers.

Figure 1. Age and year of interview for the PNC speakers.

DEFINITION OF THE LINGUISTIC VARIABLE

This discussion will define a quotative as a verbal introducer of direct speech, oral or silent, or a nonspeech sound produced by the vocal apparatus. The variable comprises three variants: say, go, and be like in all their inflected forms. Forms of be like with subject it are included but not like without a verb. Since the major constraint on the variable concerns whether the speech was produced orally, verbs that explicitly exclude oral delivery (think, figure) are not included, nor are those that specify oral form (ask, holler, yell, shout, call, scream). The quotative with all in place of like (Rickford et al., Reference Rickford, Buchstaller, Wasow and Zwicky2007) is found only once in the PNC. The form this is (NP) reported for London adolescents (Cheshire & Fox, Reference Cheshire and Fox2007) is not found in Philadelphia.

This new quotative has been found not only in the simple past, but in a wide variety of tense and aspect combinations. The irrealis formation with would be like is among the most common of these.

(2) I think t–yeah I think there's a—there would be a tendency towards things being more accepted. But I still think in certain areas they would be like “Oh my god what are you saying?”

Jake R., PHI-R-2, 18

So far, be like has not been reported for indirect speech, as in (3), nor in negatives, as in (4), nor in questions, as in (5).

(3) *He was like that he was coming.

(4) *I'm not like, “What do you mean?”

(5) *Was she like, “What do you mean?”

EARLIEST USE OF BE LIKE

Every discussion of be like must begin with the first citation in the literature. It is not clear who made the first observation: it is attributed to an otherwise unknown “D. A. Kalish” in an editor's note (6) by Ron Butters in American Speech in 1982.

(6) EDITOR'S NOTE: A related phenomenon has been pointed out to me by D. A. Kalish. Many speakers who use go also have a narrative use of to be (usually followed by like, where what is being uttered is an unuttered thought, as in “And he was like, and I was going to drown and I was (like), ‘Let me live, Lord!’”

In the same year, 1982, Frank Zappa wrote the new quotative into the lyrics for his daughter Moon to perform in Valley Girl:

(7) She's like, Oh my God, bag those toenails.

These lyrics include a good supply of other quotatives: goes, goes like, like goes, and it's like.

In the years following these early occurrences, be like spread widely across the English-speaking world as reported in the linguistic sources listed in Table 1.

THE ABSENCE OF DIALECT GEOGRAPHY

Seeing be like as a new option in the domain of English quotatives, one might expect to find other options springing up in other geographic areas, as we have coke and pop alternating with soda, pavement with sidewalk, hoagie and hero with sub. But such expected regional diversity does not appear. On the West Coast, an alternate be all did appear, but after a short period of time, it gave way to the national be like. The innovative London form this is __ was reported among inner city adolescents (Cheshire & Fox, Reference Cheshire and Fox2007), but with a frequency of only 2.8% as against 24.4% for be like.

We have seen that the new quotative has spread with astonishing speed and regularity and to this we can add that it does not tolerate competitors. Its identification with the general like may point to a future of permanent age grading. But we are not in a position to predict that future any more than we could have anticipated the entrance of this new form into the Philadelphia system in 1980.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF BE LIKE IN PHILADELPHIA

The yearly neighborhood studies in the PNC before and after 1982 allow us to locate with some precision the time at which be like first appeared in Philadelphia, as well as its development to become the majority form. Figure 2 tracks the frequency of say, go, and be like by decade of birth in the PNC.

Figure 2. Proportions of quotatives in the PNC by decade of birth.

The pattern is similar to those reported for other English speech communities. The crossover point in Philadelphia, where the frequency of be like is about to surpass the frequency of say, is compared with that of four other communities in (8):

(8) Be like–say crossover points in speakers’ dates of birth:

Ontario, Canada 1965

Victoria, Canada 1965

Perth, Australia 1970

Christchurch, New ZealandFootnote 3

Philadelphia 1970

The “origin” of the new quotative in Philadelphia means the temporal location of diffusion from elsewhere. The diffusion of change from without among adults precedes the incrementation of the new change from below by the children of those adults. This consideration must inform our investigation of the mechanism involved as we examine the social characteristics of the earliest users.

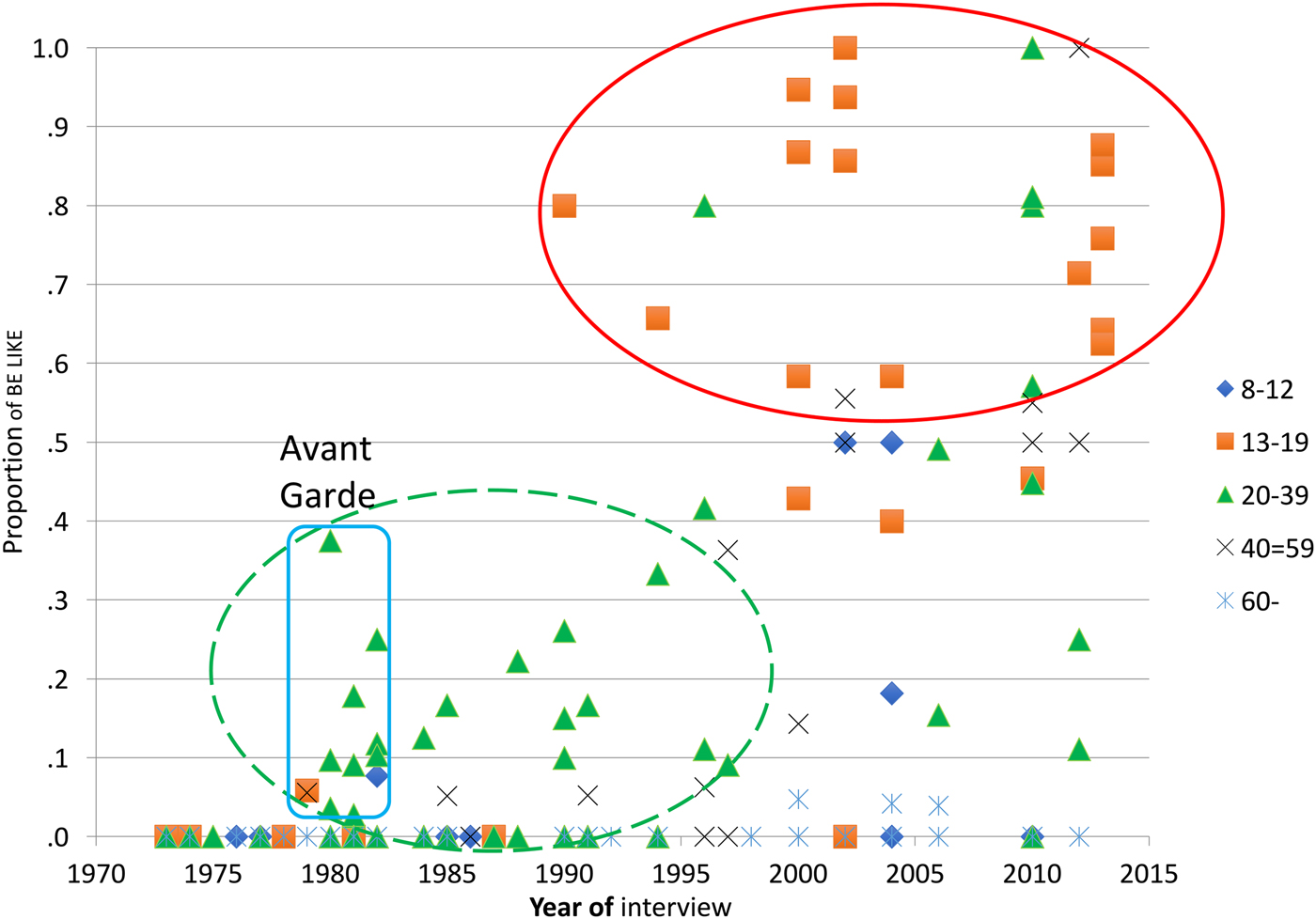

The history of be like in the PNC can be read immediately from Figure 3. We see two nonoverlapping age groups in the use of the new quotative: young adults (triangles) on the lower left, showing the early use of be like at a low frequency, and adolescents 13 to 19 years old (squares) dominating the upper right with frequencies close to 100%. The large ellipses show the successive domination of these two age groups in the importation of be like into Philadelphia.

Figure 3. Proportion of be like of all quotatives by year of interview and age of speakers in PNC.

No other age group plays an important role in the development of be like. The barred-X symbols representing speakers over 60 years old are clustered close to the 0% line throughout. Adults 40 to 59 years old (X) abstain equally from the use of the new quotative except for five who have made it to the 50% level in recent years. Three of the preadolescents aged 8 to 12 years are also found in the 50% area in recent decades, but most remain at the minimal level, indicating that they have not yet emerged from the influence of their parents.

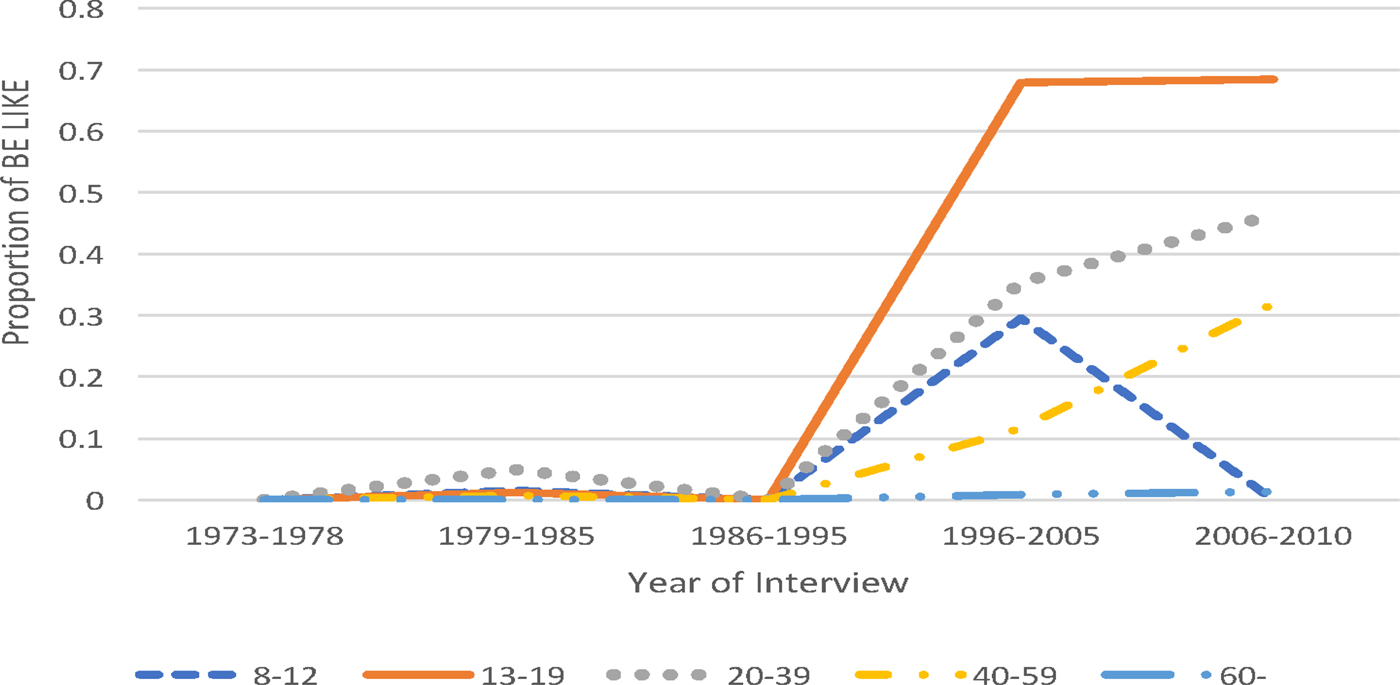

Figure 4 sums up these trends by dividing time into five periods. In the earliest, the late 1970s, be like is imported by young adults at low frequencies, while no other age group is noticeably different from 0. Once the new quotative has entered the community, it is developed to consistent use by the next generation of adolescents, while the new group of preadolescents are at a much lower level, following the pattern of their parents.

Figure 4. Proportion of be like of all quotatives by year of interview and age of speaker.

THE AVANT GARDE

For the new verb of quotation to become part of the Philadelphia speech economy, it must be through the agency of speakers who are in contact with the broader community in which be like is widespread. They are the 11 speakers within the area of 1979–1982 in Figure 3, users of be like from 4% to 40%. All but two are young adults. I will call this group the Avant Garde.

The 11 members of the Avant Garde produced 18 tokens of the new quotative. These are small numbers. Yet the distribution of semantic and grammatical features in their speech reflects the patterns that they observed in contact with outsiders is at the same time a sample of the input to the Philadelphia system as it has stabilized today.

EARLIEST USES OF BE LIKE

Only a moderate number—5 of the 18—reported a thought or inner speech, much discussed as a feature of the new verb of quotation. Of the 13 that referred to speech that was heard, only three designated a single speech act. The largest number—10—were used to designate an exemplar of the kinds of things that people say. The first use of the new quotative recorded in Philadelphia was in 1979, three years before the starting point of 1982 in an interview. It occurred in an interview with 54-year-old Victor S., the only Avant Garde member over 40. It is worth quoting in its full context, not only because it is the first of its kind, but also because it illustrates how a single use of the new quotative plays a crucial role in the resolving a tense social situation.

(9) We used to have a Club on King Street. …

We were just kids … we used to pay a dollar a week for dues.

And we had a bar back there, … but we didn't sell beer,

we used to give parties and drink 'em all ourselves. …

This one time, … uh, two guys walked in.

They said, … “well you serve uh booze here, huh?”

“Yeah” I said,

“ … I'm just gonna have a drink and I'm just gonna give you a drink,” …

And uh I gave him a drink

and the guy just nonchalantly throws a half a buck on the bar.

You know, starts walking away and I call him back

“Whoa whoa come here,” you know.

And I'm like “Alright if I put that half a dollar in my pocket”

You know, it was a speakeasy then, you know what I mean?

As soon as that money turns over, you know?

No, “I said,” … I told you we don't sell it.”

But uh, you know, I—we had this club and

Then we used to have uh cards printed

and we used to go to different dances all over the city

like Northeast, Germantown.

And girls used to come from all over,

Oh sure—as soon as you charge, it becomes a business.

Victor S., PH79-4-5, 54, Italian

The actual events involved here took place around 1960, but that does not mean that be like was used in 1960. Sometime in the late 1970s, Victor acquired the ability to use this form in rehearsing the events of that earlier time.

Be like is used in (9) to represent a single speech act, heard and responded to by the man who got the beer. A negative response would have meant trouble. The narrative shows Victor as a knowledgeable and capable participant in the social structure, and as someone who participates in the web of social communication that transmits the new quotative across neighborhoods.

A second use of be like to resolve a beer situation was recorded in 1979 in the Manayunk neighborhood from 15-year-old Lisa G.

(10) Somebody brought beer to one of my parties before.

My father smacked my face.

I was like you know in shock.

and everybody, “Are you alright? Are you alright?”

I was like, “oh just get the beer outta here”

Yeah I was so embarrassed

Lisa G., PH79-4-9, 15, Irish

There is again no doubt that the question “Are you alright?” was spoken aloud, but the subject everybody makes it plain that it was spoken by many speakers in variable forms. It is an exemplar. More than one may have actually said the words as reported, but this use of be like is consistent with a variety of social interventions with the same pragmatic impact. The larger social setting reflects a social tension of considerable weight between father and daughter.

In many such cases, it is not clear whether the sentence was spoken or not, as in (11).

(11) People'd come over and they say,

“Nance, when we come over and you just, you know, you just keep our attention, you're like a good novel, you know?”

And I'm like, “Gee I'm glad I don't get boring.”

Nancy J., PH82-1-9, 20. Hispanic

This ambiguity is an essential aspect of the pragmatics of be like and contrasts sharply with the opposition of think versus say. Thus, if the last line of (11) were to begin, “And I said,” we would clearly understand that it was an oral response to what the neighbors said.

Among these early users of be like is Ellen C., a 20-year-old woman from Second Street, a section most remote from (and hostile to) the African American neighborhoods of Philadelphia. Her interview registers five uses of be like. These include this paradigmatic example of internal thought from a discussion of the first time she tried smoking pot.

(12) I think people that—have—never tried it are more against it. Because, before, I didn't try it, I was like “What's this gonna do to me?” Y'know.

Ellen C., PH82-1-5, 20, Irish, 1982

Ellen is a hairdresser who works in a shop with 27 operators. Her profession ranks quite high among those that tap into widespread communication networks.

(13) There's all kinds of people in my work. There is. You meet all kinds of people through that job too. I mean, the people that come in, you know? Especially when you're shampooin' their hair, you know. They're relaxed, they're layin’ back there. Especially the older ladies, you know? I mean if you say hello and start asking you know, “How's the weather?” You know, you can tell if they want to talk. Some people are like, they don't even want to say nothin', you know, they're so—snobbish but some people, they tell you like, a lot of their husbands, you know. For these ladies, it's like a day out.

When we consider the particular Avant Garde speakers in Figure 5, we find evidence that they are broadly connected within the city and travel widely outside of it. Beyond her view of Philadelphia, Ellen C. has absorbed a remarkably vivid view of other American dialects.

(14) I've been to different parts of the United States.

Florida. where they kinda [kæ:nə] talk [tɐ:k] like you know

Like “Oh, it's real sunny [sɤ:ni] out.”

You know? And I've been to North Carolina [kæ:lɤnə]

where they really talk like that, you know?

And then I've been to New York where it's like

Um, How can I say? Like the water [wɑɾə].

You know, the water [wɑɾə].

Figure 5. Quotatives other than say and go in the PNC for younger speakers under age 37 years by year of interview. Digits indicate that number of the following variant. Symbols (red) between Age 27 and 30, Year 1980 and 1982, are African American. b = be like; i = it's like; f = feel like; g = go like; k = y'know like; l = like say; q = (unframed) like; s = say like.

A 30-year-old Avant Garde speaker from the African American neighborhood of Frankford shows the same interest in regional variation as she travels to the South.

(15) They do it all over the country. We went—when—when Jennifer and I went to Florida, to Disney World in seventy-seven, she met some little white kids down there from, I don't know, they were country, Virginia, one of them Southern states, anyway. But her and a little girl got to doin' one of them little games you know, like, and it was the same, except the little girl was like, “no well we do ours this way.” But, the same thing. I said, now the kids must—I don't see how it travels, you know, like from one city to the other city to be all the way across the country like that, but I said, “damn they—they all do the same thing.”

Vanessa J., PH83-1-3, 30, African American

A 20-year old Avant Garde speaker from the same area uses the conditional with the new quotative, clearly indicating that the quoted sentence was an exemplar of many.

(16) She would like … She was the one, “I don't feel like going to school today.” I'd be like, “Oh Karen we–”

Well she was bad as I was.

Nancy J., PH82-1-9, 20, Hispanic

Another Avant Garde speaker marked for connections outside of the city is Steve P., an African American jazz artist, who travels widely in his profession throughout the United States and abroad. At the time of the recording, he was studying German in preparation for a tour abroad.

We have noted that three of the eight Avant Garde speakers in Figure 5 are African Americans 28 to 30 years old. The interpretation of this surprising fact—a first suggestion that be like is favored by African Americans—must take into account the distribution of African American speakers in the PNC database. Thirteen of the 45 African American subjects are drawn from the UMLC study of the extended social networks of Wendell Harris in 1980 to 1981. Three of those identified as Avant Garde are drawn from that study. Two of the three were members of a subset with a high degree of interaction with whites: musicians, political activists, confidence men.Footnote 4

The integration of be like into African American Vernacular English speech is shown in the following quote from Steve P.:

(17) I coulda stayed there. You know? But I didn't wanna stay there when she was in bed with another, while she's in the other room. Man, I just I be thinking, I'm like “God damn, he's in there with the goodness. Ah!”

Steve P., PH81-0-10, 28, African American

The use of be thinking before I'm like is evidence that this early use is a favored instance of internal speech. The habitual be in (17) reminds us that this grammatical form of African American Vernacular English has also spread rapidly across the United States (Bailey, Wikle, Tillery, & Sand, Reference Bailey, Wikle, Tillery and Sand1993) and that networks for the diffusion of new linguistic forms across the United States have been operative in the black community.

Another of the African American speakers in the Avant Garde group was explicitly committed to reducing the difference between black and white forms of speech. We also note the occurrence of it's like, though it is not strictly included in our definition of the variable.

(18) It’s like um really as my parents keep saying,

it’s like, “We’re really pleased you wanna get into government”

Jerome L., PH82-2-2, 20, African American

Jerome L. was interviewed in the integrated neighborhood of Mount Airy along with his best friend Burt C. Jerome's speech in (18) was markedly different from Burt's in the use of the vowel shifts characteristic of white Philadelphia, particularly fronted /ow/. He is very much aware of this difference and takes a firm ideological position on racial differentiation in language, consistent with his status in the Avant Garde.

(19) One of the biggest comments I get is, “You sound like a white boy.”

… I'm not tryin' to be white but I'm not tryin' to be black either. I've talked about this a lot, you know, with both black and white people, pro and con. … To me, I think Black English is pathetic.

You can't really have a white America and you can't have a black America. You have to have an America.

Not every member of the Avant Garde can be so clearly categorized. But we can recognize this collection of open-minded individuals as an essential component of the process of linguistic diffusion.

At this point, we should recognize the competing verb of quotation talmbout, specific to African American English (Jones, Reference Jones2016).

(20) I heard she was lookin' for me, she come lookin' for me in my class.

Talmbout, “Why is you trying to take my boyfriend away from me?”

Jackie C., PH81-12-1, 16, African American

talmbout is used to introduce indirect as well as direct discourse, in a manner consistent with its historical origin from talking about. It represents a distinct pattern of diffusion in the African American community, characteristic of a camouflage construction (Spears, Reference Spears1982), quite distinct from the path of be like.

EARLY RELATIVES OF THE BE LIKE QUOTATIVE

Studying the early stages of the be like quotative in a given speech community may help to isolate the linguistic and semantic factors that lead to this development. Students of quotatives have been generally alert to the fact that direct quotation makes only a limited claim to reproducing the form of the speech reported: rarely for voice quality, intonation, and phonetic features; usually not for lexical and grammatical structure; and most often for semantic and pragmatic impact, which dictates the form of the speech act that follows in response. Thus, it appears that the most common form of quotative across the languages of the world is a word of the type ‘like’, which carries in other constructions the meaning of ‘comparison’ or ‘approximation’, as opposed to demonstratives, quantifiers, and verbs of motion (Buchstaller, Reference Buchstaller2014:20–21). In the early developments of Philadelphia, we observe along with the inflected forms of be like a number of other quotative forms involving like. Figure 5 displays all forms of quotatives used by younger speakers in Philadelphia (age 36 years and younger) in the years 1973 to 1996. These may reflect variation indigenous to Philadelphia, the community being studied, or variation diffusing from other dialects of English along with the new quotative. The most common form preceding the emergence of be like is the absence of a verb, with “unframed” like. Other than the inflected forms of be, we observe like preceded by it's, y'know, feel, and think. Like is less often combined with its chief competitor, as in say like.Footnote 5

We observe at the at the lower left of Figure 5 some six years before the first occurrences of be like, a number of q symbols for unframed like, as well as like say and say like. But the symbol b for be like is the only one that gains strength as the years go by.

LIKE I SAID

It has been pointed out that the diffusion of new linguistic elements is in the hands of adults, who are past their peak of language learning skills (Labov, Reference Labov2007). A striking example of this limitation of adult learning is seen in the Philadelphian development of Like I said. This early competitor of be like is not actually a quotative, as shown in its use by Victor, the very first use of be like as cited in (9).

Like I said introduces information as something already known to the listener through earlier elements in the conversation, but not spoken in the social context of that tense marker. Thus in (21), Victor the very first user of be like, uses a token of like I said at 20 minutes, 22 seconds into the interview.

(21) We didn't like him. I mean, by me like I said I was a kid and—and the other fellas were grown up.

If we ask when did Victor say that he was a kid, the answer is found some 20 minutes earlier, near the beginning of the interview.

(22) I drive—I drove when I was sixteen, I'm talkin' when I was a kid, you know? We'd play sports constantly, and we used to play a lot of games like kick the can [time 1:46].

Of the 347 instances of like I said in the corpus, only one actually emerges as a verb of quotation, again spoken by Victor S. in (23).

(23) Like you're goin' to play any game, whether you play marbles or anything you want to lose it like I said, “Ah okay I want to bet you ten match covers.” You know what I'm sayin'? [time 17:39]

The normal use of like I said is to claim that the information about to be presented can be located in previous communications of the speaker, that is, ‘this is similar to what I have already said’. Although like I said is not a true quotative, it is hard to escape the implication of the fact that it combines the two competing quotatives, like and said. Its implications appear to be motivated by the same factors that led to the diffusion of be like into Philadelphia and its rise throughout the city. Since it does not appear to be a member of the closed set of verbs of quotation, we can only track that rise in terms of its density. Figure 6 traces the rise (and fall) of like I said by decade of the interview in density per 10,000 words as compared to the true quotative I'm like.

Figure 6. Rise and fall of pseudo-quotative like I said by year of interview per 10,000 words as compared with quotative I'm like.

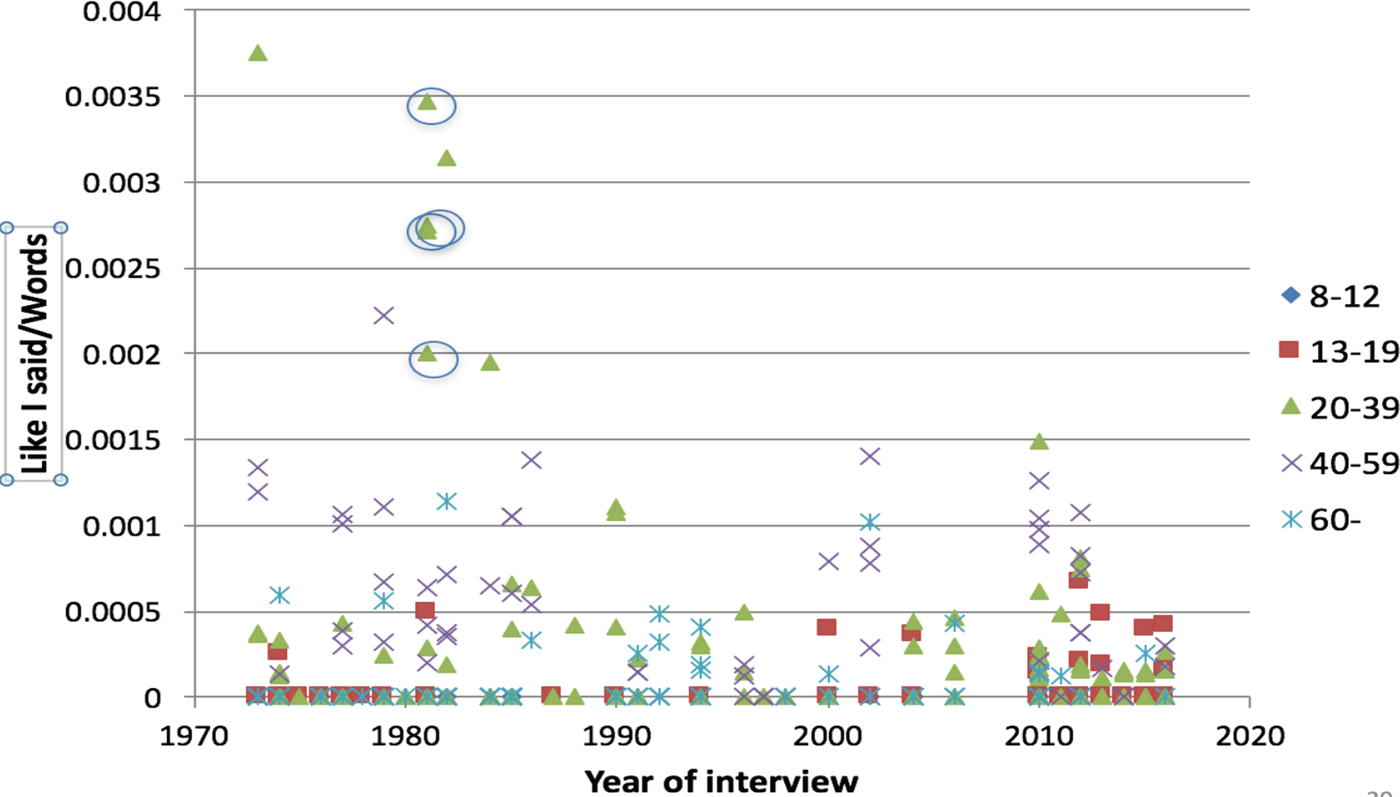

A more detailed display of the use of like I said is provided in Figure 7. The promotion of like I said by the Avant Garde is plainly shown around 1979 to 1982, parallel to the increased use of be like. The four African American speakers in the Avant Garde group are circled. After this initial expansion are the most prominent users of like I said, with a frequency of 1 to 12 per 1000 words.

Figure 7. Frequency of like I said per 10,000 words by year of interview and age group. The four African American speakers in the Avant Garde group are circled.

THE RELATION OF BE LIKE TO LIKE

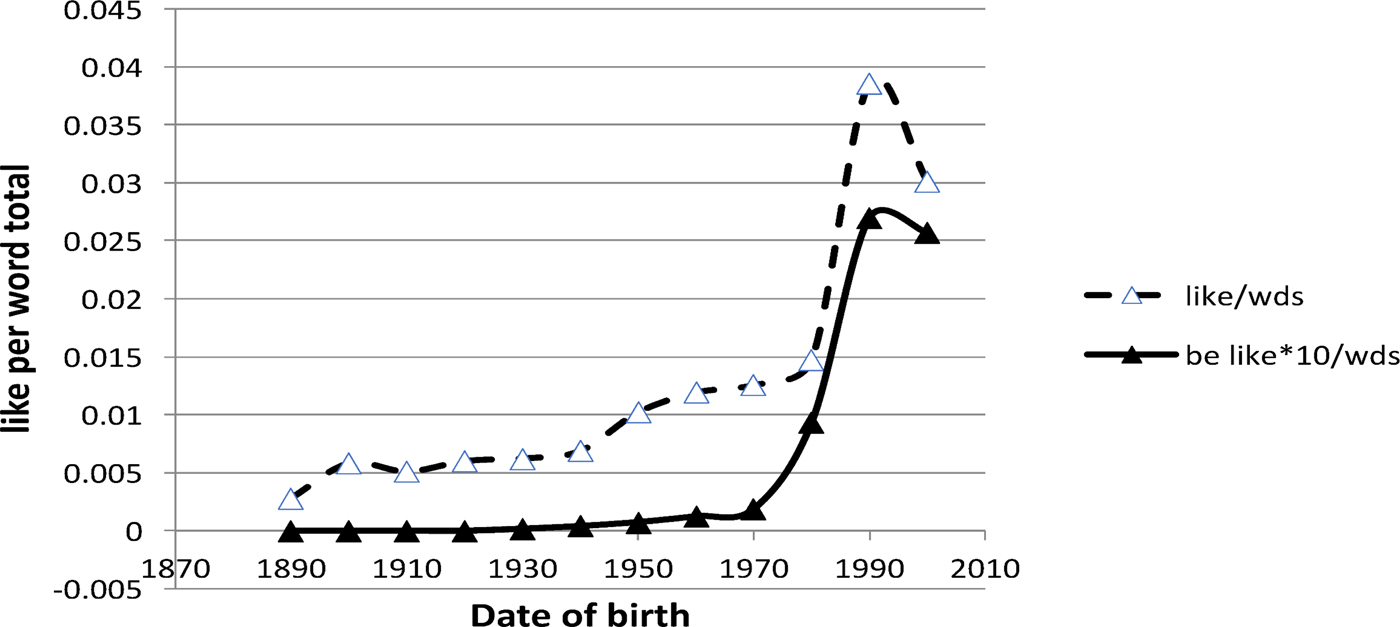

Students of be like are sensitive to the association of this new verb of quotation with other colloquial uses of like and especially the discourse marker that occurs with great frequency. The public view of the new verb of quotation associates it with a form that has no clear semantic content or grammatical function.Footnote 6 Linguistic analysis has no difficulty in discriminating the quotative from these other uses of like (D'Arcy, Reference D'Arcy2017; Dinkin, Reference Dinkin2016; Siegel, Reference Siegel2002). Nevertheless, there is a close association between the use of be like and like in general, as shown in Figure 8. The highest frequency of like in the PNC is that of a 14-year-old boy from a South Philadelphia neighborhood recorded in 2010. An excerpt from his interview is shown in Figure 9, with tokens of like highlighted.

Figure 8. Relation of be like to total use of like by date of birth.

Figure 9. Use of like by Michael C., 14, Irish, South Philadelphia. Words = 88. Like = 12. Overall like/words = .101.

LEARNING FROM SMALL NUMBERS

The view of be like in Figure 3 is based on a smaller number than the data on sound changes in Labov et al. (Reference Labov, Rosenfelder and Fruehwald2013). It rests on the proportions of be like for the 229 speakers who used more than four verbs of quotation in the interview. The data set of 4290 quotations is considerably smaller than the 56,747 tokens used to study the raising of /ey/ in Philadelphia (Labov et al., Reference Labov, Rosenfelder and Fruehwald2013). But this reduction in numbers is not accompanied by a loss of information. Figure 3 shows clearly that the new quotative was introduced in the speech of young adults in the late 1970s and carried to a higher level by adolescents in the 1990s. The radically distinct distributions of the young adults, adolescents, and older speakers makes this evident in a way that would not be demonstrated more clearly by further numerical analysis.

Still, the smaller numbers leave some uncertainty about the definition of the group. Adolescents are often defined as the age range 13 to 17 years; here the 18- to 19-year-old group of the “late adolescents” are included. Further studies may decide otherwise.

EXCLAMATIONS AND SURPRISE

Further studies of be like in Philadelphia may consider the constraints on the act of quotation: inner thought versus speech acts, person, and tense. But before concluding the study of the Avant Garde, we may want to consider a feature of the content quoted that has not been a part of previous reports: the high frequency of exclamations before other material quoted. Here are some of the left edge discourse markers that are introduced by be like.

(24) Oh by the way Ah Now

Oh I don't know Alright What the hell

Oh Jesus Christ Boy Wow

Oh my god Doo dee doo Yeah

Oh my goodness Gee Yeah yeah

Oh no Good

Oh yeah Hey

Although other reports on be like have not considered exclamations as one of the variable parameters, examples used to introduce the new quotative are heavily weighted with them. These expressions indicate various degrees of surprise. Prototypical “Oh my god!” lets us know that the speaker has suddenly become aware of an event or an object that has a greater effect on them then they had expected, for better or for worse. Some such emphatic expressions are marked by transcribers with an exclamation point, as in (25), reacting to raised pitch and intensity. Others are transcribed without one, as in (26), indicating a less stressed vowel with no clear semantic or pragmatic content.

(25) but like to walk through that door was like “Oh my god!”

like you didn't wanna do it. You couldn't call here.

Sharon S., PH96-3-6, 30, Irish

(26) There aren't enough of us inner city kids there to just be like “Oh I live in this part of Philadelphia”

And I was like, “Oh I don't know.”

Albert P., PH75-1-1, 25

Table 2 is a comparison of the frequencies of these two exclamations for the three quotatives say, be like, and go. It adds to other indications discussed herein that the new verb of quotation is associated with an increase in total communication among participants in discourse (Buchstaller, Reference Buchstaller2014:72–73). Table 2 presents the use of “Oh” and “Oh my God” with verbs of quotation in PNC.

Table 2. Use of “Oh” and “Oh my God” with verbs of quotation in PNC

THE AVANT GARDE AS AGENTS OF CHANGE

The view of the Avant Garde presented so far is that of a group of people who are linked through their social networks to a wider community and permit new forms to flow by simple contact. But it is possible that members of the Avant Garde are agents of a more active type. The new verbs of quotation, as they are heard more often, may serve a community in which inner thoughts are more often verbalized. The members of the Avant Garde may themselves promote change, doing more often what is natural to do with the new tools at hand.

The young adult speakers recorded between 1980 and 1995 used the new verb of quotation 28 times. They began 15 of these quotations with exclamations as shown in (27).

(27) like “Ah!”

like “Oh no”

like “God damn he's in there”

like “Boy like hey man. You know”

like “Gee I'm glad I don't get”

like “Hey baby this could be”

like “Hey w- what?”

like “Hey you know hey baby”

like “Look if you want to be”

like “Man director man”

like “Oh.” He's like “Shut up”

like “Oh I was gonna go get it”

like “Oh Karen we”

like “Well forget it.”

like “Wow man! Where'd they go?”

We can conclude from this inventory that the members of the Avant Garde were not only alert to the new forms of quotation that they heard elsewhere, but they were also inclined to make use of it to extend their own expressive styles.

In the hands of a gifted narrator, the exclamatory form of be like achieves great force, as in (28), from the account of a 16-year-old girl of her affair with a 40-year-old father of three.

(28) But we broke up. We broke up.

He went to the FBI academy in Virginia.

But that's not why we broke up.

Because this number kept on coming up on his pager

when he was in his—

he had to drop off papers in Center City

so I was like checking his beeper.

I'm like “O K”. Came up once.

I'm like, “Alright.” Came up again two seconds later

and I'm like “Alright!”

And it came up five times total within ten minutes.

So I wrote the number down and called it.

And I said, you know, “How do you know Larry Roberts?”

And she's like, “Because uh he's my brother-in-law.”

She was like, “How do you know Larry?”

“You one of his sluts?”

And I was like, “Oh my god!”

Brigitte C., PH94-1-6, 16, African American/white

Here the internal character of the quotative assumes imperative force, intimately combined with the sense of alarm at the immediate consequences of the situation. In the final sentence of (28) the structural ambiguity of be like emerges with considerable force, foregrounding the reason not to make the words of surprise part of a conversation. Brigitte is not a member of the Avant Garde but a second-generation user; she appears in Figure 3 as one of the earliest of the adolescent majority be like speakers, with 65% in 1994.

THE NEW QUOTATIVE AS AN EVALUATIVE DEVICE

In studying the use of quotations in narratives of everyday speech, I find it useful to make contact with the narrative theory that originated in Labov and Waletzky (Reference Labov, Waletzky and Helm1968). We can recognize a narrative style, which delivers information on a sequence of events by narrative clauses separated by temporal juncture, and a rhetorical style, in which the speaker evaluates that information for the listener with a wide variety of linguistic devices. In narratives centering about reported speech, these devices include exemplars, exclamations, reported thoughts, and nonlinguistic noises.

We are then returned to the question raised by Lavandera (Reference Lavandera1978), how can we study variation above the level of phonology, where we may find covariation of both form and meaning? An overview of linguistic variation and change as a whole shows that this is not a general problem in the study of grammatical variation, but it has been fairly well confined to the domains of tense, mood, and aspect, where quotatives are intimately involved.

Thus Myhill (Reference Myhill1995) has shown that the English modals have changed over the course of the 19th century, disfavoring must and favoring got to, while at the same time people came to express necessity not so much as institutional but personal compulsion. We cannot rule out the possibility that the growth of the new quotative is parallel to the growth of a more expressive style, as children are encouraged to be in touch with their emotions and let significant others know how they feel about them. The general study of language change may involve change in what is most likely to be done with the new tools that the evolving language has to offer. As attractive as these issues may be for further research, they carry us beyond the closed sets of objective analysis.Footnote 7 The principle finding of this study flows from the social distribution of the new verb of quotation in Figure 3, displaying the path of linguistic diffusion with remarkable clarity.

The Avant Garde does not appear to be a social network or a community of practice. It is an uncollected collection of influentials, whose children inherit what they have done, and do more with it.