Introduction

Schizophrenia is a chronic, severe, and complex psychiatric disorder characterized by an array of neuropsychological symptoms affecting mood, behavior, perception, and cognition.Reference Nasrallah, Tandon and Keshavan 1 , 2 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), over 20 million people are suffering from schizophrenia worldwide, whose life expectancy is about 14.5 years shorter than that of the normal population. 2 , Reference Hjorthøj, Stürup, McGrath and Nordentoft 3 With the onset of symptoms between the second and the third decade,Reference Gureje 4 schizophrenia is also associated with considerable disability,Reference Ormel, Petukhova and Chatterji 5 worsened functioningReference Reichenberg, Feo, Prestia, Bowie, Patterson and Harvey 6 as well as deficits in educational and occupationalReference Brown 7 perfromance. 2 In order to achieve remission and essentially recovery,Reference Leucht and Lasser 8 optimized treatment strategies are needed that consider multiple factors when making therapeutic decisions.Reference Falloon, Held, Roncone, Coverdale and Laidlaw 9

One approach to do this is the clinical staging framework which, complementary to the classical diagnostic systems such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM), 10 provides an understanding of where the patient lies within the course of the disorder as well as promotes recovery in the early stages of the illness while preventing progression to the later ones.Reference McGorry, Nelson, Goldstone and Yung 11 , Reference Cosci and Fava 12 To date, there are many proposed models of clinical staging in schizophrenia utilizing different criteria for defining the distinct stages.Reference Cosci and Fava 12 One of the most influential concepts has been developed by McGorry et al who divided the course of schizophrenia into five main stages; stage 0—increased risk of psychotic disorder, stage 1—mild and moderate symptoms, stage 2—first psychotic episode, stage 3—incomplete remission and relapse(s), and stage 4—persistent and severe illness.Reference McGorry, Nelson, Goldstone and Yung 11 Recently, another model was proposed by Fountoulakis et al who systematically mapped the different symptoms of schizophrenia using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) in a large cohort of patients and came up with a clinical staging framework that also provides a timeline for when approximately these stages begin from the onset of psychosis.Reference Fountoulakis, Dragioti and Theofilidis 13 According to the results of this empirical research, schizophrenia is composed of four major stages starting with positive symptoms (stage 1, lasting 3 years), continuing with hostility (stage 2, lasting 9 years) and depressive symptoms (stage 3, lasting 13 years), and ending with cognitive symptoms (stage 4, lasting 55 years).Reference Fountoulakis, Dragioti and Theofilidis 13 Indeed, according to the general literature, the first episode of schizophrenia dominated by mainly psychotic or positive symptoms has been estimated to last about 2 to 5 years after onset,Reference Breitborde, Srihari and Woods 14 -Reference Costa, Massuda and Pedrini 16 while someone is considered to have chronic schizophrenia after experiencing different symptoms for more than 15 to 20 years.Reference Costa, Massuda and Pedrini 16

Cariprazine, a novel antipsychotic medication with potent dopamine D3-D2 and serotonin 5HT1A receptor partial agonism and preferential binding to the D3 receptors, has been approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for the treatment of adult schizophrenia patients (1.5-6.0 mg/day) and by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States for the treatment of bipolar I disorder (3.0-6.0 mg/day) and schizophrenia in adults (1.5-6.0 mg/day). The efficacy and safety of cariprazine in acute exacerbation of schizophrenia was assessed and demonstrated in three phase II/III clinical trials with a randomized, multicentered, double-blind and placebo-controlled design.Reference Durgam, Starace and Li 17 -Reference Kane, Zukin and Wang 19 Importantly, two of the clinical trials also included an active comparator arm, namely risperidone and aripiprazole.Reference Durgam, Starace and Li 17 , Reference Durgam, Cutler and Lu 18 When evaluating change from baseline to week 6 on the primary outcome measure, PANSS total score, cariprazine was found to be statistically significantly better in contrast to placebo in all three trials individually as well as pooled.Reference Durgam, Starace and Li 17 -Reference Marder, Fleischhacker and Earley 20

Objectives

To better understand the efficacy and safety of cariprazine in the different stages of schizophrenia, a post hoc analysis pooling data from three phase II/III trials was conducted in two subgroups of patients; patients with schizophrenia for less than 5 years (early stage) and for more than 15 years (late stage).

Methods

Study design

Data from three phase II/III 6-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials with similar design in patients with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia were pooled (NCT00694707 [placebo, cariprazine 1.5, 3.0, or 4.5 mg/day, and risperidone 4.0 mg/day], NCT01104766 [placebo, cariprazine 3.0 or 6.0 mg/day, and aripiprazole 10 mg/day], and NCT01104779 [placebo and cariprazine 3.0-6.0 or 6.0-9.0 mg/day]).Reference Durgam, Starace and Li 17 -Reference Kane, Zukin and Wang 19 Each trial consisted of a 1-week wash-out period, followed by a 6-week double-blind treatment, and a 2-week safety follow-up.Reference Durgam, Starace and Li 17 -Reference Kane, Zukin and Wang 19 The primary efficacy endpoint was change from baseline to week 6 in the PANSS total score, and the secondary was the same in the Clinical Global Impressions-Severity of Illness scale (CGI-S).Reference Durgam, Starace and Li 17 -Reference Kane, Zukin and Wang 19 Safety measures included adverse events, laboratory tests, vital signs, electrocardiography, and extrapyramidal symptom scales.Reference Durgam, Starace and Li 17 -Reference Kane, Zukin and Wang 19

Patients

According to the inclusion criteria, patients aged 18 to 60 with a diagnosis of schizophrenia according to the DSM 4th edition who were currently experiencing an acute episode for less than 2 weeks were eligible to take part in the studies. Additionally, subjects had to have a minimum score of 4 on the CGI-S, between 80 and 120 on the PANSS, including a score of at least 4 on more than two of the PANSS positive symptom items. Those who were suffering from another psychotic disorder or substance abuse within 3 months of the study, had their first episode of psychosis, were treatment resistant or exhibited risk for suicide were excluded. Concomitant medications except for drugs alleviating agitation, irritability, hostility, and restlessness (lorazepam, oxazepam, or diazepam), managing insomnia (eszopiclone, zolpidem, zolpidem extended release, chloral hydrate, or zaleplon), or treating extrapyramidal symptoms (diphenhydramine, benztropine or equivalent, or propranolol) were prohibited.

Post hoc analysis

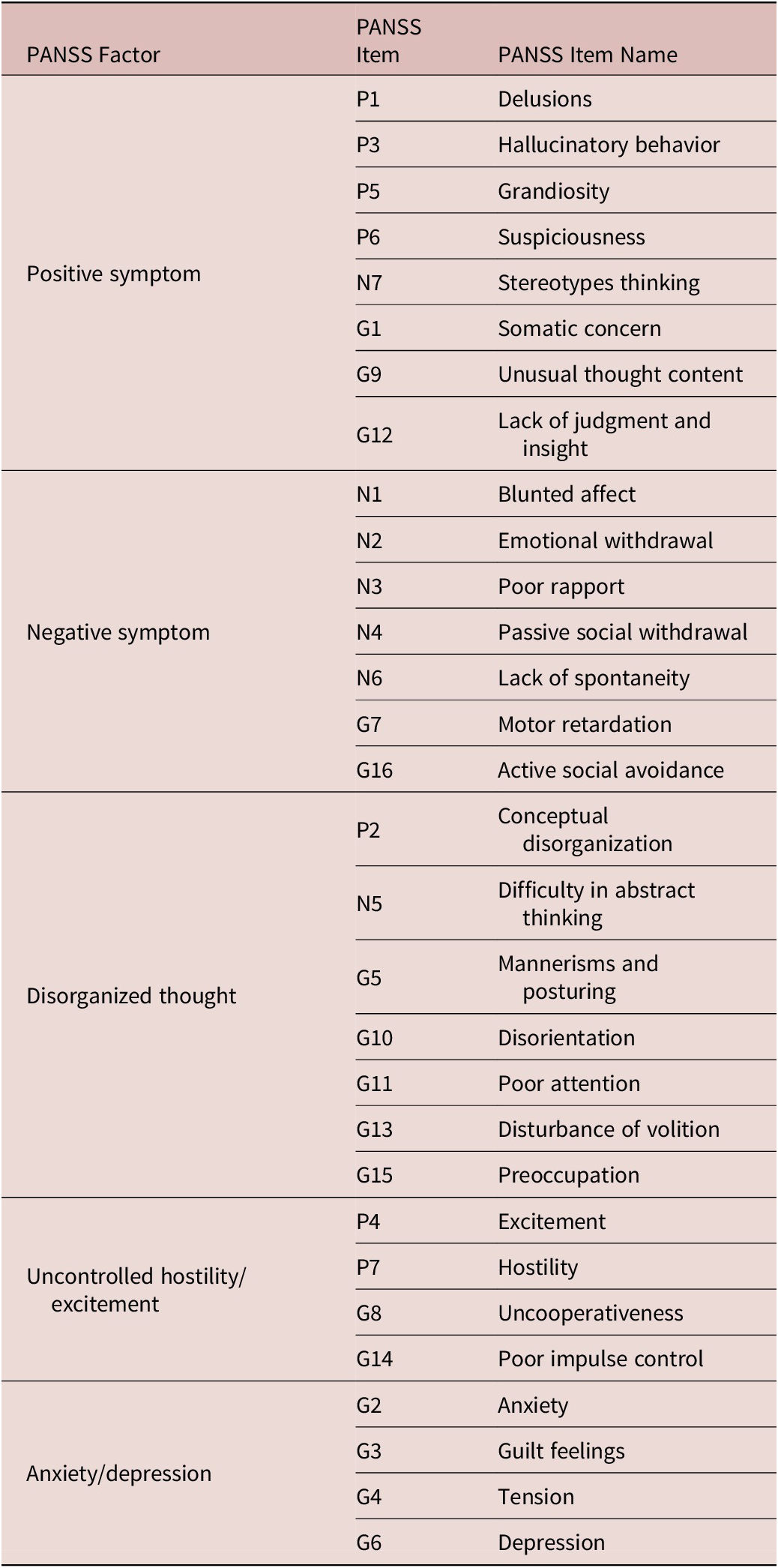

To understand the efficacy and safety of cariprazine in the early and late stage of schizophrenia, two subgroups of patients were identified; patients whose duration of schizophrenia was less than 5 years (early stage) and those who were suffering from the disorder for equal to or greater than 15 years (late stage). Given the fact that patients in the different stages are likely to exhibit distinct symptom profiles (ie, patients in the early stages are more likely to have positive and hostility-like symptoms whereas depressive and cognitive symptoms are more prevalent later in the course of the disorder),Reference Fountoulakis, Dragioti and Theofilidis 13 not only the PANSS total but the Marder PANSS factor scores for positive, negative, disorganized thought, uncontrolled hostility/excitement and anxiety/depression symptoms were also evaluated (Table 1).Reference Marder, Davis and Chouinard 21 In case of the efficacy measures, data from the intention-to-treat (ITT) population, and in case of the safety measures, data from the safety population (those patients who received at least one dose of cariprazine) of the three phase II/III trials were pooled. To analyze data, a mixed-effects model for repeated measures (MMRM) approach was applied and least square (LS) mean changes from baseline to week 6 for cariprazine and placebo and LS mean differences between cariprazine vs placebo on the PANSS total and PANSS-derived factor scores were reported. Safety analyses included treatment emergent adverse events (TEAEs) and discontinuation rates, summarized in percentages. Concomitant medication use of benzodiazepines, defined as taking a benzodiazepine for five consecutive days, was also analyzed in percentages for both cariprazine and placebo groups in total as well as in the early and late stages. Duration of benzodiazepine intake was calculated in medians. Differences between responders (defined as at least 30% change in the PANSS score) and nonresponders in the light of benzodiazepine intake was also addressed and summarized in percentages. Mean doses given the variety of prescriptions were not possible to calculate.

Table 1. Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) FactorsReference Marder, Davis and Chouinard 21.

Results

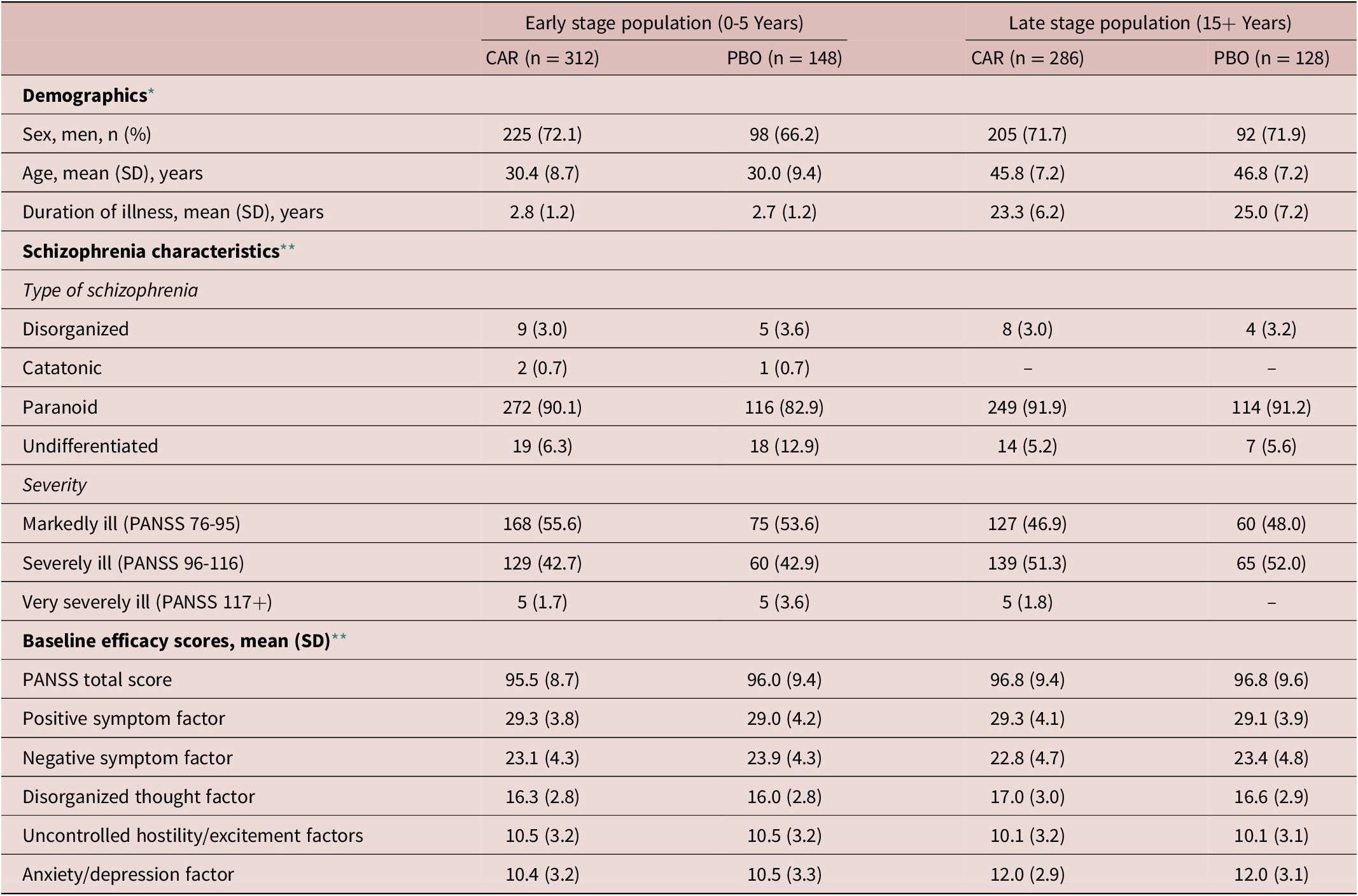

Overall, 460 patients were identified as having schizophrenia for less than 5 years (early stage), while this number was 414 in the case of patients who suffer from schizophrenia for more than 15 years (late stage) (Table 2). The majority of patients (about 70%) in both groups were male. The average age of the early stage subpopulation was around 30 years with a mean duration of schizophrenia for more than two and a half years, which can be explained by the fact that first episode patients were excluded from the trials. In the case of the late stage subpopulation, the mean age was around 46 years and the average duration of schizophrenia was around 25 years. In both subpopulations, most patients (about 90%) were diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. More patients in the early stage group were markedly ill (54%) (PANSS total score 76-95) than severely ill (43%) (PANSS total score 96-116), while this pattern was the opposite in the late stage patients (47% and 51%, respectively). The total PANSS scores were slightly higher in the late stage subpopulation, while the positive and negative factor scores were about the same. Slight baseline differences were detected in the disorganized thought factor score, with higher scores in the late stage group and in the uncontrolled hostility/excitement factors factor score, with increased scores in the early stage group. The greatest difference was found in the anxiety/depression factor scores, where the late stage subpopulation scored higher baseline values.

Table 2. Patient Demographic and Baseline Characteristics.

Abbreviations: CAR, cariprazine 1.5-6.0 mg/day; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impressions-Severity; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; PBO, placebo; SD, standard deviation.

* Safety population.

** Intention-to-treat population.

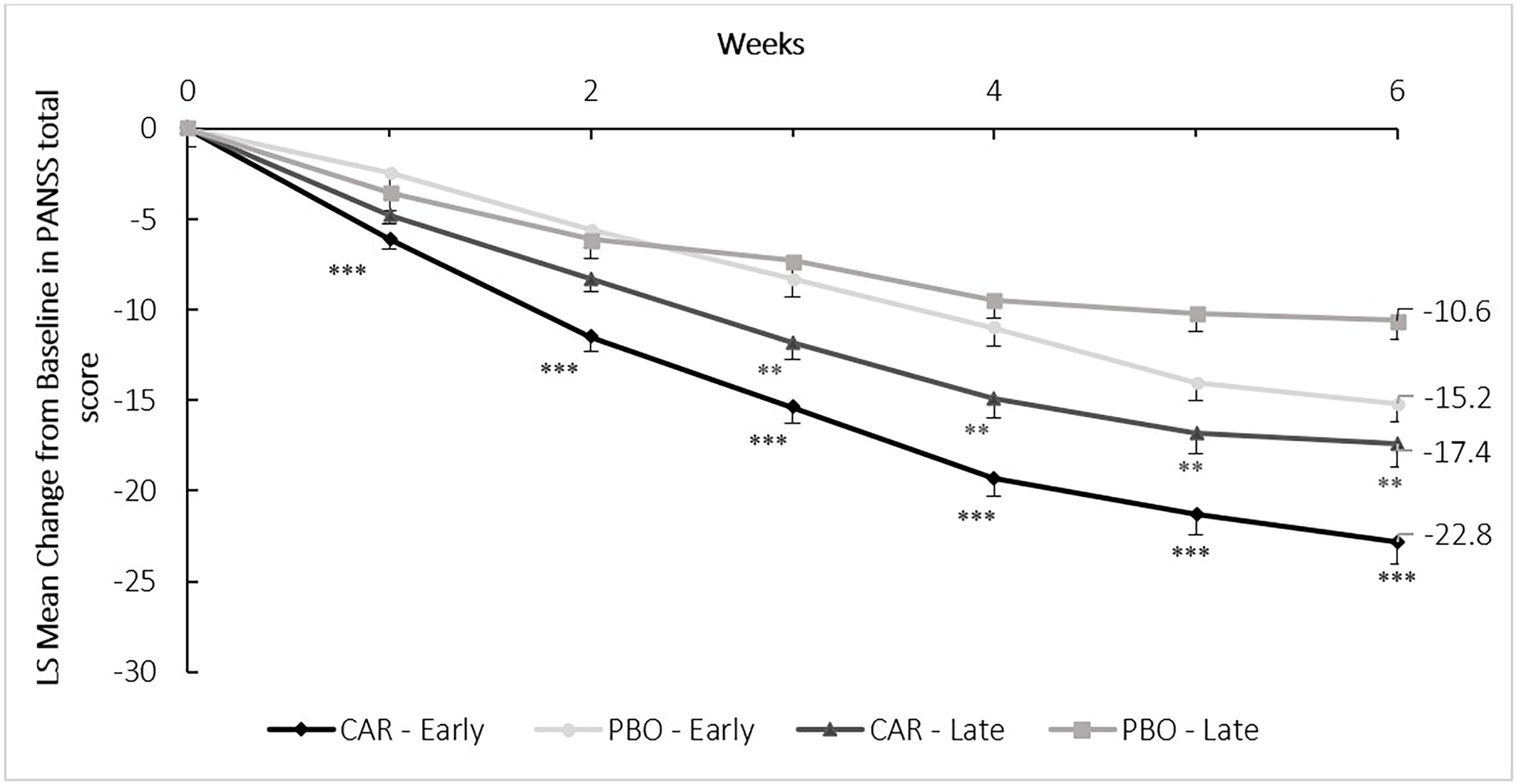

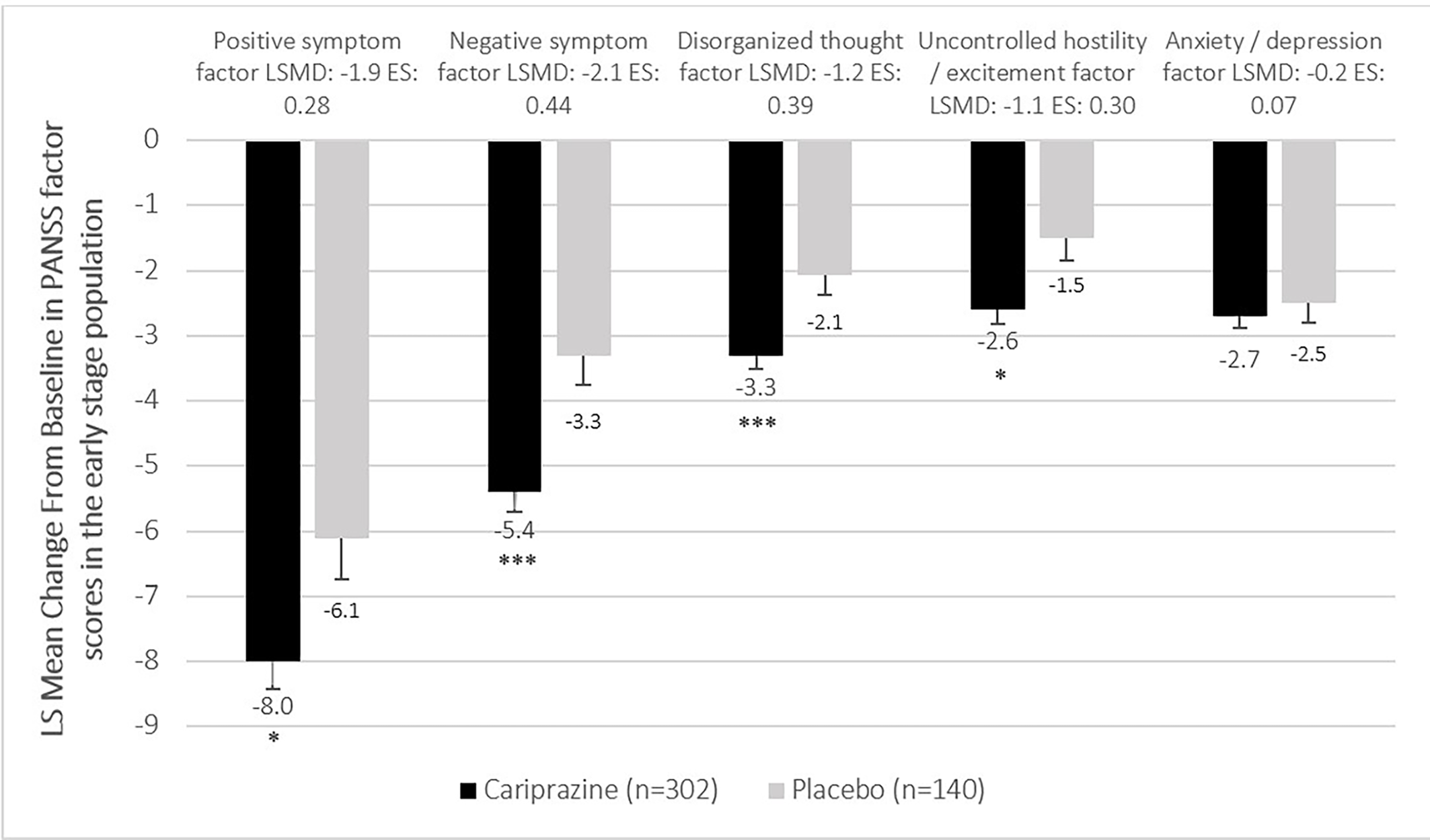

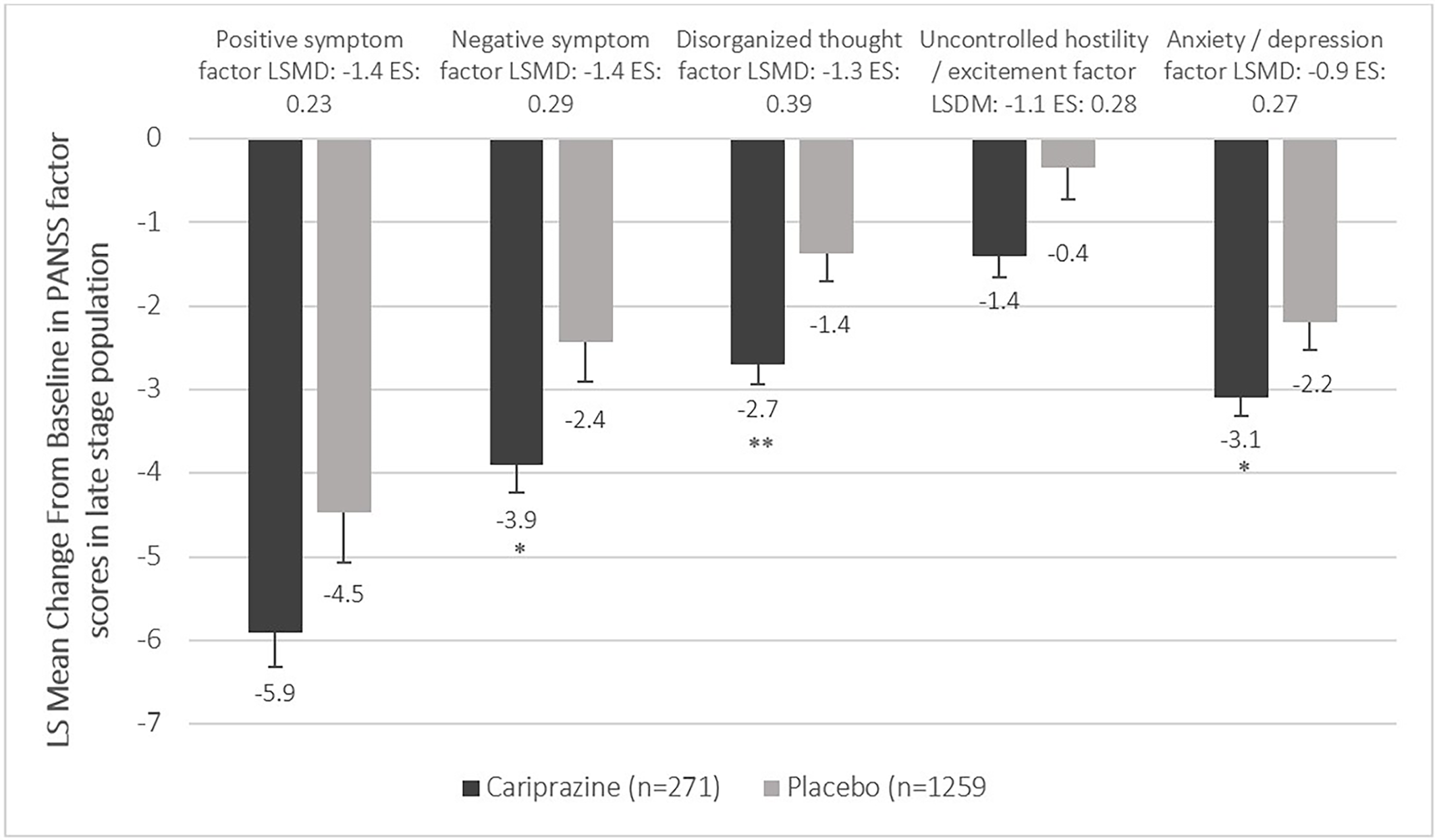

When comparing cariprazine (CAR) to placebo (PBO), the pooled analysis evaluating mean change from baseline to week 6 in the PANSS total score indicated statistically significant difference in favor of cariprazine in both the early (LS mean difference [LSMD] −7.5, P < .001) and late stage (LSMD −6.7, P < .01) subpopulation (Figure 1). In terms of the PANSS factor scores, statistically significant difference between cariprazine and placebo was detected in four out of the five factors in the early stage subpopulation (Figure 2). The greatest difference was found in the negative (LSMD −2.1, P < .001) and positive (LSMD −1.9, P < .05) symptom scores, both indicating the superiority of cariprazine. In the case of the late stage subpopulation, three out of the five factors were significantly different from that of the placebo group, namely the negative symptom (LSMD −1.4, P < .05), disorganized thought (LSMD −1.3, P < .01) and anxiety/depression (LSMD −0.9, P < .05) factor scores (Figure 3).

Figure 1. Mean change from baseline to week 6 in the PANSS total score (pooled intention-to-treat population).

P-values refer to level of significance compared to placebo **<.01 and ***<.001. CAR, cariprazine (1.5-6.0 mg/d); LS, least square; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; PBO, placebo.

Figure 2. Mean change from baseline to week 6 in the PANSS factor scores in the early stage population (pooled intention-to-treat population).

P-values refer to level of significance compared to placebo *<.05 and ***<.001.

Figure 3. Mean change from baseline to week 6 in the PANSS factor scores in the late stage population (pooled intention-to-treat population).

P-values refer to level of significance compared to placebo *<.05 and **<.01.

In terms of difference between the early and late stage groups, greater mean changes from baseline were detected in the early stage subpopulation in the positive (Early stage CAR: −8.0, PBO: −6.1; Late stage CAR: −5.9, PBO: −4.5), negative (Early stage CAR: −5.4, PBO: −3.3; Late stage CAR: −3.9, PBO: −2.4), and uncontrolled hostility/excitement factor scores (Early stage CAR: −2.6, PBO: −1.5; Late stage CAR: −1.4, PBO: −0.4). However, the mean changes from baseline in the disorganized thought (Early stage CAR: −3.3, PBO: −2.1; Late stage CAR: −2.7, PBO: −1.4) and anxiety/depression (Early stage CAR: −2.7, PBO: −2.5; Late stage CAR: −3.1, PBO: −2.2) factor scores were similar.

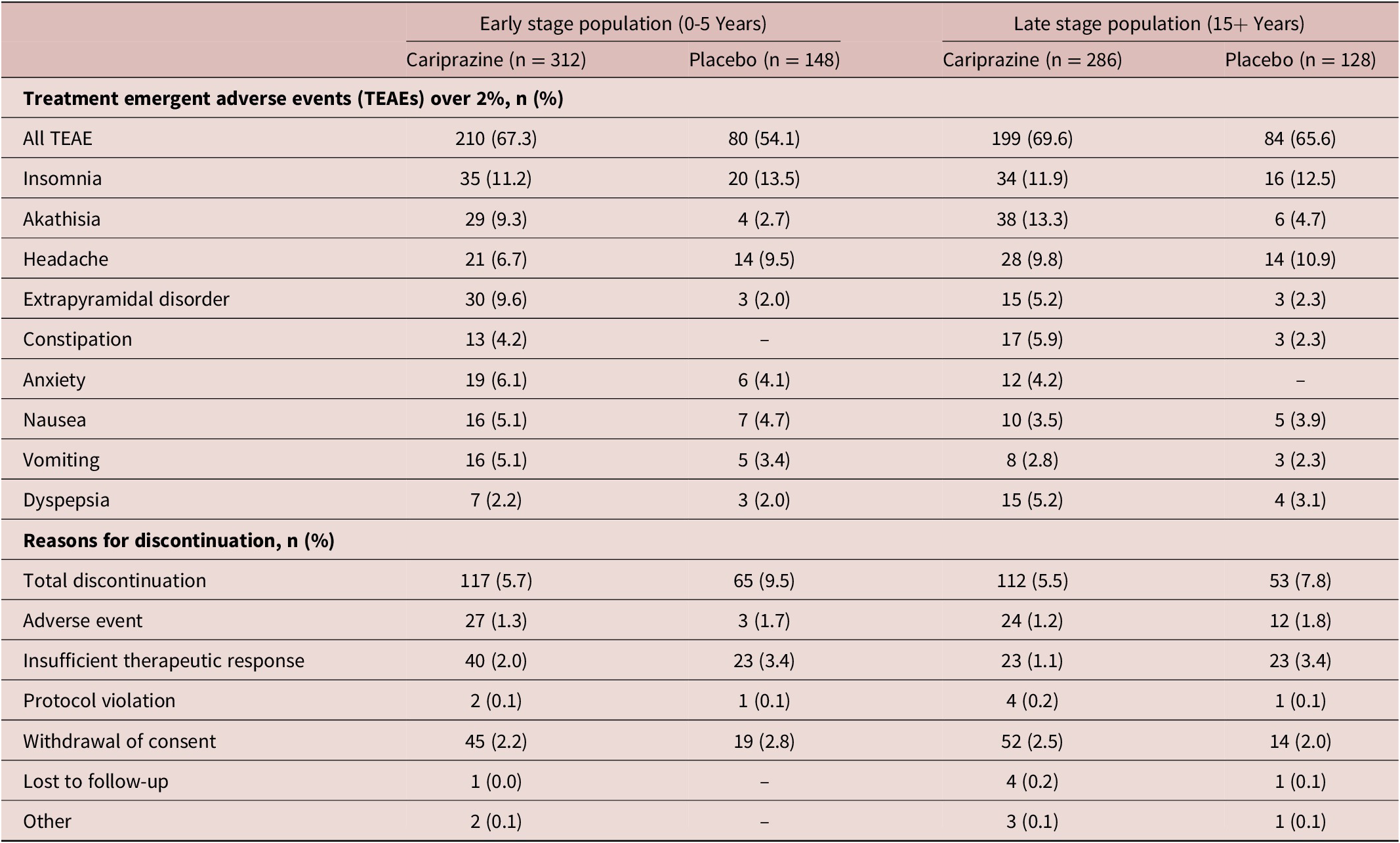

A summary of TEAEs is presented in Table 3. TEAEs in both early stage (CAR 67.3%, PBO 54.1%) and late stage patients (CAR 69.6%, PBO 65.6%) were comparable. Most subjects in the early stage subpopulation reported insomnia (CAR 11.2%, PBO 13.5%), extrapyramidal disorder (CAR 9.6%, PBO 2.0%) and akathisia (CAR 9.3%, PBO 2.7%). Altogether, 5.7% of early stage patients discontinued their cariprazine treatment (PBO 9.5%), mostly due to withdrawal of consent (CAR 2.2%, PBO 2.8%), or insufficient therapeutic response (CAR 2.0%, PBO 3.4%). Similarly, participants of the late stage subpopulation taking cariprazine reported akathisia (CAR 13.3%, PBO 4.7%), insomnia (CAR 11.9%, PBO 12.5%), and headache (CAR 9.8%, PBO 10.9%). In this group, 5.5% of cariprazine-treated patients discontinued their treatment (PBO 7.8%), driven by consent withdrawal (CAR 2.5%, PBO 2.0%) and adverse events (CAR 1.2%, PBO 1.8%).

Table 3. Treatment Emergent Adverse Events.

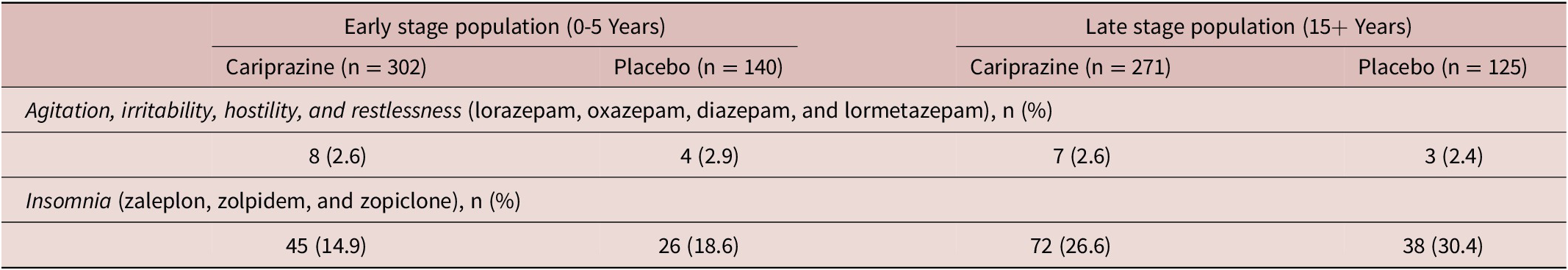

Regarding concomitant medication, 24.7% of cariprazine and 24.4% of placebo treated patients received benzodiazepines for either agitation, irritability, hostility, and restlessness—treated by lorazepam, oxazepam, diazepam, and lormetazepam (CAR 2.8%, PBO 1.8%), or for insomnia—treated by zaleplon, zolpidem, zolpidem tartrate, and zopiclone (CAR 21.6%, PBO 22.6%). In terms of agitation, irritability, hostility, and restlessness, no differences between early stage and late stage patients were detected in neither the cariprazine nor the placebo group (Table 4). In case of insomnia however, more medication was needed for late stage patients (CAR 26.6%, PBO 30.4%), than for patients in the early stage (CAR 14.9%, PBO 18.6%). In terms of the duration of benzodiazepine treatment, patients in the early stage took these medications for shorter period (CAR 55 days, PBO 30 days) than the late stage group (CAR 80 days, PBO 41 days). The duration of benzodiazepine treatment was longer in case of medications for insomnia (CAR 16 days, PBO 20.5 days) as well. Differences regarding responders and nonresponders were also analyzed; 17.8% of responders in the cariprazine and 30.1% in the placebo group received benzodiazepines.

Table 4. Benzodiazepine Use.

Note: Concomitant medication use defined as taking such medications at least five consecutive days.

Discussion

Although baseline PANSS factor scores were quite similar in the two subpopulations, which can be explained by the fact that the studies had a strict inclusion criteria (ie, acute schizophrenia patients with certain disorder severity), some characteristics of the early and late stages were still prevalent. In the early stages of schizophrenia positive and hostility symptoms dominate, with quite high levels of negative symptoms also complicating the clinical picture.Reference Fountoulakis, Dragioti and Theofilidis 13 In contrast, as the disorder progresses, negative and cognitive symptoms became more prevalent with considerable levels of anxiety and/or depression.Reference Fountoulakis, Dragioti and Theofilidis 13 Indeed, in the present pooled analysis, patients in the late stage group exhibited higher baseline scores in the PANSS anxiety/depression and disorganized thought factors. Importantly, differences in change from baseline to week 6 were statistically significant irrespective of the stage of the disorder in favor of cariprazine vs placebo in the PANSS total score. Better response was detected in the early stage group compared to the late stage group, which is line with the assumption that patients in the beginning of the disorder have better treatment response than those who are suffering from schizophrenia for a longer period.Reference Jäger, Riedel and Messer 22 Notably, this was prevalent in patients who were not experiencing their first episode per se, but were still in the beginning of the course of the disorder.

Regarding the different symptom domains, statistically significant difference was detected in the PANSS positive symptom, negative symptom, disorganized thought, and uncontrolled hostility/excitement factor scores compared to placebo in the early stage group. The greatest change from baseline was found in the positive and negative symptom factor scores, which is not surprising given that these domains had the highest baseline values as well. It is also important to note, that cariprazine was statistically significantly better in reducing cognitive symptoms in this group as measured by the disorganized thought factor score compared to placebo. As cognitive impairment associated with schizophrenia is one of the most important predictors of functional outcomes, it is highly emphasized in the literature that addressing this symptom group is vital if one aims to achieve remission and recovery early in the course of the disorder.Reference Lepage, Bodnar and Bowie 23 -Reference Vishnu Gopal and Variend 25 As currently there is no adequate treatment option for alleviating cognitive deficits, antipsychotics that have the ability to improve such symptoms are preferred over those which deteriorate cognition.Reference Goff, Hill and Barch 26 -Reference Torrisi, Laudani and Contarini 28 It is also worth addressing, that cariprazine was significantly better in treating hostility as well, which is highly prevalent in the beginning of the disorder and is associated with the increased levels of psychotic symptoms.Reference Fountoulakis, Dragioti and Theofilidis 13 , Reference Volavka, Van Dorn, Citrome, Kahn, Fleischhacker and Czobor 29 Thus, cariprazine seems to be a good treatment option from the beginning of the disorder which has been also suggested by an international panel of experts who based their recommendation on real world experiences with cariprazine.Reference Fagiolini, Alcalá and Aubel 30

In contrast to the early stage subpopulation, patients in the late stage group had smaller treatment response, though differences compared to placebo were still significant in three out of the five symptom domains, namely in negative symptom, disorganized thought, and anxiety/depression factor scores. These results are in line with the general literature where it is often reported that patients in the chronic stage of schizophrenia exhibit reduced treatment response to positive symptoms. 31 , Reference Takeuchi, Siu and Remington 32 This is related to the fact that patients in this stage have often had experienced multiple relapses, with each relapse worsening their therapeutic response to antipsychotic medication.Reference Takeuchi, Siu and Remington 32 Importantly, however, the most dominant symptoms in this stage of the disorder are the cognitive, negative, and the anxiety/depressive symptoms and cariprazine showed superiority over placebo in improving these factors.Reference Fountoulakis, Dragioti and Theofilidis 13 In fact, better treatment response was detected in the anxiety/depression factor scores in this subpopulation than in the early stage patients. As the main goal of treatment in late stage schizophrenia besides continuous symptom control is the improvement of the patients’ quality of life,Reference de Bartolomeis, Fagiolini, Vaggi and Vampini 33 which has been continuously found to be related to negative symptoms and cognitive deficits,Reference Novick, Montgomery, Cheng, Moneta and Haro 34 -Reference Kaneko 37 results of this post hoc analysis seem to support the notion that cariprazine is a good choice for this patient population as well. It is also important to note that although in this study population treatment resistant patients were not included, it is a quite common phenomenon in late stage schizophrenia.Reference Potkin, Kane and Correll 38 According to several guidelines, such patients are recommended to be treated with clozapine if multiple antipsychotics have previously failed in alleviating the symptoms.Reference Taylor and Perera 39 , Reference Gaebel, Falkai and Hasan 40 Interestingly, two case reports by De Berardis et al showed that combining cariprazine with clozapine can be helpful, resulting in not only reduction in PANSS scores over time but also in positively affecting weight and BMI.Reference De Berardis, Rapini and Olivieri 41 Indeed, in the general literature it has been already noted that combining clozapine with partial agonists can have beneficial effects.Reference Fagiolini, Alcalá and Aubel 30

In terms of the safety and tolerability of cariprazine, results have shown only slight differences between the early and late stage subpopulations. The most commonly experienced TEAEs were insomnia and akathisia in both groups, followed by extrapyramidal symptoms and headache. Importantly however, insomnia and headache were more prevalent in the placebo groups than in the cariprazine-treated groups. Another indicator of the fact that cariprazine was well tolerated by both early and late stage groups is that discontinuation due to adverse events was low. Indeed, tolerability of an antipsychotic medication is highly important, as it is directly linked to medication adherence,Reference Higashi, Medic, Littlewood, Diez, Granström and de Hert 42 , Reference DiBonaventura, Gabriel, Dupclay, Gupta and Kim 43 which in turn is connected to relapseReference Xiao, Mi, Li, Shi and Zhang 44 which eventually results in reduced treatment response and worse long-term outcomes.Reference Almond, Knapp, Francois, Toumi and Brugha 45 Although akathisia and extrapyramidal symptoms are the most common adverse events in cariprazine-treated patients, previous studies have shown that majority of such events were mild or moderate in severity and the majority of patients continued treatment despite symptoms.Reference Barabássy, Sebe and Acsai 46 Their findings also suggest that akathisia in cariprazine-treated patients can be well managed with rescue medication and dose reduction.Reference Barabássy, Sebe and Acsai 46 Benzodiazepine use as concomitant medication was comparable in the cariprazine and placebo groups. All in all, it can be concluded that cariprazine was safe and generally well tolerated in patients with early and late stage schizophrenia in the recommended dose range.

The present analysis is however not without limitations. First of all, as emphasized in section “Methods,” patients who were experiencing their first episode of psychosis were excluded from the trials, meaning that a significant subgroup of the early stage patients were not represented in this dataset. Nonetheless, as seen in the results, these patients still showed better treatment response than the late stage group which supports the general notion that patients in the beginning of the disorder are more responsive to treatment. Furthermore, as data were pooled from clinical trials where patients needed to fit into a highly rigorous criteria, differences between subgroups are not as prevalent and hence many typical early and late stage patients were probably not represented adequately in the analysis. This is most prevalent in case of the baseline characteristics, where no major differences between the two subgroups were detected. In spite of this, results of cariprazine treatment indicated different responses in different subgroups which signals that there may be even more pronounced differences in how early and late stage patients respond to treatment in real life. Furthermore, pooling data has its own strengths and weaknesses—while being able to show more robust results, pooling is also prone to biases in terms of revealing something as significant while it is clinically irrelevant or happened by chance. In the case of the present analysis however, given the high similarity between study designs, no such effect is expected. Finally, concomitant medication use other than benzodiazepines were not calculated due to limitations of the available data.

Conclusion

In this post hoc analysis, the efficacy and safety of cariprazine in the early (patients with up to 5 years of schizophrenia) and late (patients with more than 15 years with schizophrenia) stage of schizophrenia were investigated. In conclusion, cariprazine, a potent D3-D2 partial agonist has been found to be safe and effective in the treatment of both groups. Further research is needed to understand its efficacy in first episode population, as these patients were not included in the clinical trials. Nonetheless, based on these results, it is predicted that cariprazine can be a good option for that patient group well. Similarly, further studies are needed to confirm the benefit of combination cariprazine with clozapine in treatment resistant patients in late stage schizophrenia, as reported in several case studies.

Disclosures

Peter Falkai has been an honorary speaker for AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Lilly, Essex, GE Healthcare, GlaxoSmithKline, Gedeon Richter, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Servier, and Takeda and has been a member of the advisory boards of Janssen-Cilag, AstraZeneca, Lilly, and Lundbeck. Andrea Schmitt was an honorary speaker for TAD Pharma and Roche and a member of Roche advisory boards. Zsófia B. Dombi, Ágota Barabássy, and György Németh are employees of Gedeon Richter. Károly Acsai is a former employee of Gedeon Richter.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: P.F., Z.B.D., Á.B., A.S., G.N.; Formal analysis: K.A.; Investigation: Á.B.; Methodology: Z.B.D., K.A.; Project administration: Á.B.; Resources: G.N.; Supervision: P.F., Á.B., A.S., G.N.; Visualization: Z.B.D.; Writing—original draft: Z.B.D.; Writing—review and editing: P.F., Z.B.D., K.A., Á.B., A.S.