1. Introduction

The multilateral trading system has always accounted for the reality that Members of the World Trade Organization (WTO) would take trade restrictive actions for national security reasons. It is on this premise that multilateral trade agreements contain security exceptions.

For decades, the Contracting Parties of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), and later the broader group of WTO Member States, generally only relied on the GATT security exceptions on sporadic and informal occasions (Mavroidis, Reference Mavroidis2016, 481; Alford, Reference Alford2011). Governments implicitly understood that the security exceptions were important, albeit dangerous for the maintenance of the multilateral trading system.Footnote 1 However, the absence of invocation over time never eradicated the significance of national security as a justification or right of States engaging in international commerce. As economist Thomas Schelling remarked in 1971, ‘trade policy is national security policy’ (United States Commission on International Trade and Investment Policy, 1971, 737).

The 2019 WTO Panel Report for Russia–Traffic in Transit is the first formal analysis of Article XXI:b(iii) of the GATT.Footnote 2 Article XXI provides:

Nothing in this Agreement shall be construed

(a) to require any [Member] to furnish any information the disclosure of which it considers contrary to its essential security interests;

(b) to prevent any [Member] from taking any action which it considers necessary for the protection of its essential security interests;

(i) relating to fissionable materials or the materials from which they are derived;

(ii) relating to the traffic in arms, ammunition and implements of war and to such traffic in other goods and materials as is carried on directly or indirectly for the purpose of supplying a military establishment;

(iii) taken in time of war or other emergency in international relations; or

(c) to prevent any [Member] from taking any action in pursuance of its obligations under the United Nations Charter for the maintenance of international peace and security.Footnote 3

The panel report provides an analytical, legal framework for ascertaining whether a respondent Member properly invoked Article XXI:b(iii) (para. 7.149). The highly sensitive, political nature of this dispute is comprehended in the determination of the standard of review and Russia's burden of proving the factual and legal elements of Article XXI:b(iii).Footnote 4 With Russia refusing to disclose any information, the panel found ‘sufficient’ evidence, based on facts already before it and of ‘common knowledge’, had been presented by Russia to identify the ‘emergency in international relations’ (see Section 3.3). Moreover, in finding an ‘emergency in international relations’ in the sense of Article XXI:b(iii), the panel accepted that Russia's measures were ‘not implausible as measures protective’ of Russia's articulated essential security interests (see Section 3.4). The minimal legal and factual evidence required by the panel from Russia to properly invoke the security exceptions is tethered to its overarching finding that this dispute touched the ‘hard core’ of war or armed conflict. In the end, the panel found Russia had met the requirements for invoking Article XXI:b(iii) of the GATT (para. 7.149).

It remains an open question whether a dispute far from this ‘hard core’ means a WTO panel would (or should) impose a more exacting burden upon the invoking Member. The preliminary economic analysis conducted in this paper evidences obvious economic motivations for the imposition of the transit restrictions considered by the panel, directly questioning the plausibility of such measures and their ‘good faith’ application.

The article is laid out, as follows: Section 2 offers a recap of the facts of the dispute. Section 3 considers the panel's legal interpretive framework for the invocation of Article XXI:b(iii) of GATT, as well as its application to Russia's assertions in this dispute. Section 4 offers economic analysis. Section 5 considers the implications of the panel report. Section 6 concludes.

2. Factual Background

2.1 Russia's Security Measures

As pointed out by the panel (para. 7.5), this case has to be framed within the troubled geopolitical context of Russia and Ukraine and a cooperation history marked by conflicts of varying intensity that culminated with the annexation of Crimea into the Russian Federation on 18 March 2014. This event followed the wave of demonstrations and political unrest of the ‘Euromaidan’ in November 2013 against the decision of the Ukrainian government to strengthen ties with Russia and suspend the signing of an association agreement with the European Union, after which economic and political relations strongly deteriorated. Despite the initial steps taken toward adhesion to the Eurasian Economic Union (EaEU Treaty),Footnote 5 Ukraine decided not to join the EaEU, instead choosing to seek economic integration with the European Union (para. 7.7). On 21 March 2014, Ukraine signed the EU–Ukraine Association Agreement also called the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA).

To de-escalate the situation, and in response to the Russian annexation of Crimea, a series of United Nations General Assembly Resolutions were adopted in 2014 and 2016 (para. 7.8). The events in Ukraine in 2014 were followed by both Russia and Ukraine resorting to economic retaliatory measures and sanctions against each other. During the same period, third countries also imposed economic sanctions against ‘Russian entities and persons’ which led to retaliatory sanctions imposed by Russia on these specific countries (initially, the United States, European Union Member States, Canada, Australia, and Norway) (para. 7.10). Russia's measures took the form of import bans, customs duties, and restrictions on the transit of goods (paras. 7.8–7.19).

2.2 The WTO Challenge

On 14 September 2016, Ukraine initiated a dispute against Russia. At issue were a number of measures taken between 2014 and 2016, including bans of imports of Ukrainian goods. The panel examined measures classified in the three categories summarized below:Footnote 6

1. The 2016 Belarus Transit Requirements require ‘all international cargo transit by road and rail from Ukraine destined for the Republic of Kazakhstan or the Kyrgyz Republic, through Russia, be carried out exclusively from Belarus, and compl[iance] with a number of additional conditions’ (para. 7.106). Such measures make a distinction between the traffic in transit based on the place of departure, of destination, and of entry (para. 8.2.bi).

2. The 2016 Transit Bans on Non-Zero Duty Goods and Resolution No. 778 Goods prohibits all road and rail transit from Ukraine of: (i) ‘goods that are subject to non-zero import duties according to the Common Customs Tariff of the EaEU’, and (ii) ‘goods that fall within the scope of the import bans imposed by Resolution No. 778, which are destined for Kazakhstan or the Kyrgyz Republic’ (para. 7.106). Subject to the 2016 Belarus Transit Requirement, special derogations may be requested to allow the transit of such goods. Such measures make distinctions between the traffic in transit based on the place of departure, of destination, of origin, of entry (para. 8.2.bii), as well as on the duty status.

3. The 2014 Belarus–Russia Border Bans on Transit of Resolution No. 778 Goods provides that veterinary and plant goods subject to veterinary and phytosanitary surveillance and to the import bans under Resolution No. 778 may only transit through designated checkpoints located on the Russian side of the external border of the EaEU (paras. 7.327 and 7.106). Such bans make distinctions between the traffic in transit based on the place of entry and the place of origin (para. 8.2.biii).

Ukraine raised claims under GATT Articles V:1, V:2, V:3, V:4, X:1, X:2, X:3(a), and under several parts of Russia's Working Party Report as incorporated into Russia's Accession Protocol (paras. 7.106, 7.156–7.161, 7.201, 7.357).

Russia raised the general defense of Article XXI:b(iii), but did not rebut any of Ukraine's claims (paras. 7.3, 7.22–7.23). According to Russia, these were ‘serious’ ‘political and security matters’ that ‘should be kept out of the WTO’ (para. 7.22). Instead, Russia asserted that the panel lacked jurisdiction to evaluate the WTO-consistency of its measures, owing to Russia's invocation of GATT Article XXI:b(iii) (para. 7.24). This argument depended upon Russia's interpretation of the wording of Article XXI as conferring ‘sole discretion’ on the invoking Member to determine ‘the necessity, form, design, and structure’ of Article XXI measures (para. 7.28). In other words, its interpretation of the security exceptions was that the exceptions were totally ‘self-judging’ (paras. 7.23, 7.26). According to Russia, such a reading guaranteed unchecked authority to invoke the security exceptions and to refuse to supply information relating to its invocation. Ukraine countered that Article XXI was not subject to the sole authority of Russia, but merely ‘an affirmative defence’, which the panel must examine pursuant to the general standard of review under the DSU (para. 7.31).Footnote 7

As a third party to this dispute, the United States also perceived the text of Article XXI as purely self-judging. However, the United States’ assertion diverted from that of Russia, arguing that all national security-related disputes are ‘non-justiciable’ on the basis that there are ‘no legal criteria by which the issue of a Member's consideration of its essential security interests can be judged’ (para. 7.52). Likewise, the United States argued that ‘[i]ssues of national security are political matters not susceptible for review’ by WTO dispute settlement (para. 7.51, n. 139). Most participating third parties argued the panel did have jurisdiction to examine the case, consequently disagreeing with the United States’ broad claim that the dispute was totally non-justiciable (section 7.5.2).

3. The Panel's Legal Assessment of the Requirements of GATT Article XXI:b(iii)

3.1 The Panel's Jurisdiction to Address Matters Arising in Relation to GATT Article XXI

Judgments are constituted by the disputing parties’ arguments and presentation of claims. The panel began by considering Russia's assertion that Article XXI was entirely self-judging, as the argument for unilateral determination meant that GATT Article XXI:b(iii) would be ‘carve[d] out’ from its jurisdiction (para. 7.57). In response to Russia's objections, the panel recognized its ‘inherent jurisdiction’ to determine all matters (para. 7.53). Further, the panel observed that Articles 1.1 and 1.2 of the DSU set out the rules and procedures as applicable to disputes regarding the covered agreements, including the GATT, without any exceptions or special rules of procedure applying to disputes where a Member invoked Article XXI. Accordingly, Russia's invocation of Article XXI:b(iii) was found to be within the panel's terms of reference (para. 7.55).

To determine whether the panel maintained ‘the power to review’ the application of Article XXI:b, it considered the breadth of the adjectival clause ‘which it considers’ within the introductory paragraph of Article XXI:b (para. 7.58). There were a number of possible elements that this adjectival clause (viewed as self-judging language) qualified, including: (i) the ‘necessity’ of the measures taken for the protection of the invoking Member's essential security interests; (ii) the determination of ‘essential security interests’, or (iii) the entire provision, including assessment of a Member's ‘essential security interests’, the ‘necessity’ of the measures taken, and the connection between such measures and the circumstances described in sub-paragraphs (i) through (iii) of Article XXI:b (para. 7.63). The panel needed to interpret the provision to determine whether certain elements were not subject to the self-judging language; this required evaluating the function of the enumerated circumstances of sub-paragraphs (i) through (iii) in Article XXI:b.

As Russia had only invoked sub-paragraph (iii), the panel focused on the meaning of ‘in time of war or other emergency in international relations’. The panel likened this phrase ‘to a situation of armed conflict, or of latent armed conflict, or of heightened tension of crisis, or of general instability engulfing or surrounding a state’ (paras. 7.75–7.76). The panel supported its understanding against the wording of the other enumerated circumstances in sub-paragraphs (i) and (ii). Further, it emphasized the fact that sub-paragraph (iii) was defined as ‘war or other emergency in international relations’ (paras. 7.71–7.72). Thus, a time of emergency in international relations referred to ‘defence or military interests, or maintenance of law and public order interests’ (paras, 7.75–7.76, 7.111). Concerns involving ‘world politics’ must nevertheless, the panel found, go beyond ‘political or economic conflicts’ with other Members or States (para. 7.75).

The panel found that the preparatory work for the making of the GATT security exceptions was helpful in observing a close connection between the enumerated circumstances and Members’ own articulation of essential security interests (para. 7.83). The drafting history of the security exceptions confirmed that the GATT drafters, particularly the United States (the lead architect), conceptualized both elements of ‘essential security’ and ‘emergency in international relations’ as war or near war-like situations (para. 7.98; see also Pinchis-Paulsen, Reference Pinchis-Paulsen2020, 170).

Other evidence of the International Trade Organisation (ITO) Charter preparatory work elaborates on the intended breadth and depth of the security exceptions (Pinchis-Paulsen, Reference Pinchis-Paulsen2020, 170).Footnote 8 In discussions with other governments, the US delegation was unified in its view that the United States only sought ‘to draft provisions which would take care of real security interests’. The ‘realness’ of a government's security interests informed the circumstances enunciated in the sub-paragraphs. In discussions with other government delegations, the US delegation defended the provision as seeking ‘to limit the exception[s] so as to prevent the adoption of protection for maintaining industries under every conceivable circumstance’. Moreover, the US delegation rejected an interpretation that understood an emergency as addressing food supplies or otherwise permitting ‘anything under the sun’.

While not canvassed by the panel, archived internal US documents deepen our understanding into the drafting of the phrase ‘in times of war or other emergency in international relations’ in Article XXI:b(iii) of the GATT. When drafting the exceptions, the US State Department officials (tasked with foreign economic policy) wanted a narrowly defined exception to constrain other governments from taking measures that contravened ITO commitments. In contrast, the US defense officials sought broadly scoped exceptions that made clear each invoking government retained absolute authority to deter from the multilateral trading rules. These internal debates constituted certain compromises in language; for example, altering the original language of ‘in time of war or imminent threat of war’ to ‘international emergency’ due to concerns of publicizing war preparation strategies in a trade mechanism (Pinchis-Paulsen, Reference Pinchis-Paulsen2020, 140–141). Additionally, the phrase ‘international emergency’ was altered to ‘emergency in international relations’ to clarify that an ‘economic emergency’ did not qualify (Pinchis-Paulsen, Reference Pinchis-Paulsen2020, 142).

The panel determined its jurisdiction through a range of sources. In addition to reliance on historical context to decipher the meaning of sub-paragraph (iii) of Article XXI:b, the panel considered the general object and purpose of the GATT and the WTO Agreement to find that whether actions were taken ‘in time of war or other emergency in international relations’ was an ‘objective state of affairs’ and subject to review by the panel (para. 7.78). It seemed ‘entirely contrary’ to the core aims of security and predictability of the multilateral trading system to include a provision granting any Member ultimate authority over its trading commitments under the GATT and WTO agreements (para. 7.79).

It is also noteworthy that the panel proceeded to consider the propriety of Russia's invocation of Article XXI:b(iii) before examining Ukraine's claims that Russia's measures were inconsistent with the GATT, as well as the Protocol of Accession of the Russian Federation. This was a departure from the approach taken by other WTO panels and the Appellate Body with respect to the invocation of Article XX general exceptions (Van Damme, Reference Van Damme, Bethlehem, McRae, Neufeld and Van Damme2020; Van Den Bossche and Akpofure, Reference Bossche, P. and Akpofure2020). The panel reasoned that unlike measures covered by the general exceptions under Article XX, situations arising under Article XXI:b(iii) were never taken ‘in normal times’ (para. 7.108). This ‘particularity’ of ‘emergency in international relations’ suggests that Article XXI:b(iii) actions are presumed ‘necessary’ (as they are subject to the sole discretion of the invoking Member), though only with respect to the invocation of Article XXI:b(iii) (paras. 7.108, 7.146).

The more recently decided Saudi Arabia–IP Rights panel report suggests that future panels need not apply this panel's order of analysis where the panel's jurisdiction is without question.Footnote 9 It is an open question whether this panel's reversal of the order of analysis would also apply to invocations sub-paragraphs (i) or (ii) of Article XXI:b, as the panel's choice was connected to the temporal limitation of sub-paragraph (iii) and the term ‘necessary’ in the introductory paragraph of Article XXI:b.

3.2 Russia's Refusal to Disclose any Factual Evidence or Legal Arguments

For Russia, the panel (and the WTO more generally) ‘are not in a position to determine whether sovereign states are at war’ (para. 7.28, n. 67). Russia argued that by invoking Article XXI:a, Russia could choose for itself what information to disclose in this dispute (on the basis that subparagraph (a) also contained the self-judging language ‘which it considers’). In this case, Russia refused to supply factual evidence or arguments beyond what ‘it has declared in its first written submission and opening statement at the first meeting of the panel’ (para. 7.129). Ukraine countered that invocation of Article XXI:a does not grant Russia unilateral authority over the assessment of Article XXI:b(iii) and, consequently, Russia cannot evade its burden of proof (para. 7.129).

The disputing parties’ burden of proof is not explicitly set in the DSU or any covered agreement (Van Den Bossche and Zdouc, Reference Van den Bossche and Zdouc2017, 256). The Appellate Body has consistently reasoned that the party asserting a claim or defence ‘adduces evidence sufficient to raise a presumption that what is claimed is true’.Footnote 10 However, ‘how much and precisely what kind of evidence … will necessarily vary from … provision to provision, and case to case’.Footnote 11 Moreover, the Appellate Body has emphasized that ‘a panel is vested with ample and extensive discretionary authority to determine when it needs information to resolve a dispute and what information if needs’.Footnote 12

The DSU does not require ‘special or additional rules of procedure’ when a dispute involves Members’ essential security interestsFootnote 13 (para. 7.56). Nor does it appear to be the case that negotiators considered invocation of Article XXI:a during the negotiation of the DSU.Footnote 14 Without formal interpretation of Article XXI, the Decision of 30 November 1982 provides in its first paragraph that ‘Subject to the exception in Article XXI:a, [Members] should be informed to the fullest extent possible of trade measures taken under Article XXI.’Footnote 15

Returning again to US archived materials, the internal meetings of the State Department officials show deliberation over this question, with State Department officials viewing a ‘general exemption from supplying information’ as ‘unnecessary’ (Pinchis-Paulsen, Reference Pinchis-Paulsen2020, 157). Moreover, it appears that early US drafts anticipated that governments could refuse to provide information in a report, leaving it possible for governments to dictate different procedures behind closed doors (Pinchis-Paulsen, Reference Pinchis-Paulsen2020, 156).

Unfortunately (though, perhaps, understandably so), the panel did not address Russia's invocation of Article XXI:a as independent of, or as related to, its invocation of Article XXI:b. Even while acknowledging that all WTO Members must invoke Article XXI in ‘good faith’ (para. 7.133), the panel did not assess whether Russia had invoked Article XXI:a as a right or justification for refusing to disclose information in good faith.Footnote 16

The political context of the ‘particular circumstances of this dispute’ was such that the panel accepted that Russia had supplied ‘sufficient’ evidence for the panel's objective assessment (para. 7.119). One need not have been in the room to appreciate that pressing on the scope of Article XXI:a in this dispute could have led to Russia's refusal to carry on with the proceedings.Footnote 17 While a finding that a Member need only supply ‘sufficient’ evidence is somewhat indeterminate, the panel's assessment suggested an evidentiary burden far below an ‘overly demanding’ one.Footnote 18

That being said, the reality is that Russia's refusal goes beyond shielding sensitive, confidential information pursuant to general transparency provisions, such as Article X:1 of the GATT. Up until now, there has been no firm elaboration as to what should occur in a situation where an invoking Member withholds all information to demonstrate the legal and factual elements of its invocation of Article XXI. Isabelle Van Damme (2020) reasoned that greater clarification as to how Article XXI:a impacts an invoking Member's burden of proof when invoking Article XXI:b. She observes that accepting that invocation of Article XXI:a is enough to satisfy the burden of proof in this way ‘would considerably undermine a complainant's right of defense’.

In light of Van Damme's concerns, it is clear a responding Member should supply some evidence, even if to explain the nature of the withholding of evidence – that is, to still present legal arguments for the invocation of all parts of Article XXI. Moreover, Michael Hahn (Reference Hahn1991) emphasized that a panel should ‘make every effort to fulfill their duty to obtain a suitable factual basis for the determination of legality’. Where attempts to require a disputing party to supply information to the panel are ‘fruitless’, then the Member refusing to give information could ‘bear the disadvantage arising out of such an omission and lose its protection provided by article XXI’ (Hahn, Reference Hahn1991, 616). The absence of discussion in this case suggests a future panel may address an invoking Member's refusal to disclose information, including possible consideration of the potential of adverse findings in such security-related trade disputes (Hahn, Reference Hahn1991, 616). The impact of Article XXI:a upon a respondent Member's burden of proof obligations with respect to the objective assessment of the sub-paragraphs of Article XXI:b remains an open question.Footnote 19

3.3 Analysing Russia's Invocation of Article XXI:b(iii) of the GATT

The panel developed a two-step approach to evaluating Russia's invocation of Article XXI:b(iii) of GATT. First, the panel objectively assessed whether Russia met the elements within sub-paragraph (iii) of Article XXI:b, namely whether its measures were taken in a time of emergency in international relations. Second, the panel considered whether Russia's invocations met the conditions set out in the introductory paragraph of Article XXI:b (the chapeau of the provision). Specifically, whether Russia has sole, interpretive authority to articulate its essential security interests and the necessity of the actions taken for the protection of those interests.

3.4 Did Russia Act in Time of Emergency in International Relations?

Having already interpreted the phrase, ‘war or other emergency in international relations’, the panel considered Russia's identification of the dispute as such (para. 7.110). However, Russia's refusal to disclose information meant the panel could only consider Russia's assertion that the dispute involved ‘politics, national security and international peace and security’ (para. 7.112). Ukraine countered that Russia had left it and the panel ‘in the dark’ as to what particular ‘other emergency in international relations’ had occurred (para. 7.113). According to Ukraine, Russia failed to meet its burden of proof under GATT Article XXI:b(iii) by ‘not adequately identify[ing] or describ[ing] the 2014 emergency’ (para. 7.113).

Rather than detail the actual emergency in international relations that led to the imposition of trade restrictions, Russia posed ‘hypothetical questions’ to the panel (para. 7.114). The goal was to understand what, hypothetically, could amount to an ‘war or other emergency in international relations’ in the sense of Article XXI:b(iii) (para. 7.114).Footnote 20 The only reference to real life events was the following, general description: ‘the emergency in international relations that occurred in 2014 that presented threats to the Russian Federation's essential security interests’ (paras. 7.112 7.118).

Russia referred to Ukraine's 2016 Trade Policy Review Report (TPRM) to demonstrate the hypothetical situation of ‘the annexation of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the military conflict in the east’ towards the identification of the emergency between them (paras. 7.112–7.118). According to Russia, the TPRM explained in Ukraine's own words, ‘what is going on and how real these whole hypothetical questions are’ (para. 7.115). Ukraine objected to the use of the TPRM on the basis that prior panels had ‘refused to attach importance to the [TPRM]’ in WTO disputes proceedings (paras. 7.116–7.117). In the end, the panel concluded that the TPRM either did not apply to this situation, or that it was ‘precluded from taking into account Russia's reference’ to Ukraine's 2016 TPRM (para. 7.118).

The effort to demonstrate the hypothetical rather than the real helps explain why the panel resorted to ‘facts that are common knowledge and which cannot reasonably be disputed’ (para. 7.118). The panel did not require Russia to do more than reference events in a ‘cryptic’ manner (Addendum, E-1 Interim Review, para. 2.79). Instead, the panel considered it ‘reasonable to infer’ that the sanctions imposed by certain other countries against Russia from 2014 in response to this emergency, which Russia itself acknowledged in its submissions to the panel, formed part of the evidence to identify the situation as an ‘emergency in international relations’ between Russia and Ukraine (Addendum, E-1 Interim Review, para. 2.79). That being said, the panel never directly addressed the ‘situation’ as being the annexation of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea; moreover, it remained careful to ‘not take a position on Russia's involvement in any armed conflict with Ukraine’ (para. 7.5; Addendum, E-1 Interim Review, para. 2.72).

In sum, the panel found there was ‘sufficient’ identification of the situation by Russia, due to the following factors: ‘(a) the time-period in which it arose and continue[d] to exist, (b) that the situation involve[d] Ukraine, (c) that it affect[ed] the security of Russia's border with Ukraine in various ways, (d) that it [had] resulted in other countries imposing sanctions against Russia, and (e) that the situation in question [was] publicly known’ (para. 7.119).

The panel then considered whether this situation was an ‘emergency in international relations’ under subparagraph (iii) of Article XXI:b (para. 7.120). The panel drew from evidence supplied by Ukraine – specifically, United Nations General Assembly Resolutions – to observe that ‘at least as of March 2014, and continuing at least until the end of 2016, relations between Ukraine and Russia had deteriorated to such a degree that they were a matter of concern to the international community’ (para. 7.122). Moreover, by December 2016, the United Nations General Assembly had recognized the matter ‘as involving armed conflict’ (para. 7.122). Further evidence into the ‘gravity’ of the situation was demonstrated by the fact that other ‘countries [had] imposed sanctions against Russia in connection with this situation’ (para. 7.122). With this evidence, the panel was ‘satisfied’ that the situation constituted an ‘emergency in international relations’ in the sense of subparagraph (iii) of Article XXI:b (para. 7.123). Moreover, in consideration of the timing of the measures, the panel found that Russia acted ‘in time of’ emergency in international relations (paras. 7.124–7.125).Footnote 21

In interim review, Ukraine requested clarification be made in the Report's factual context that ‘Russia has not referred to or relied on either of the United Nations General Assembly Resolutions’ (Addendum, Appendix E, para. 2.17). Ultimately, the panel rejected Ukraine's request (Addendum, Appendix E, para. 2.20).Footnote 22 The panel was clear that it ‘must not make a case for a party where that party has failed to do so’, and must be able ‘to develop its own legal reasoning to support its own findings on the matter under consideration’ (Addendum, Appendix E, para. 2.111). Moreover, a panel's assessment of WTO Agreement texts ‘cannot be limited by the particular interpretations advanced by the parties, where such an interpretation is necessary to resolve the dispute’ (Addendum, Appendix E, para. 2.111). Still, at the final DSB Meeting, Ukraine maintained disappointment that ‘the panel improperly bore the burden of proof and made the case for the respondent’.Footnote 23 A subsequent panel for Saudi Arabia–IP Rights declined to reflect on whether the Russia–Traffic in Transit panel found an ‘emergency in international relations’ with an ‘insufficient basis’ of factual evidence.Footnote 24

3.5 Russia's Articulation of Its Essential Security Interests and the Necessity of Actions Taken

The chapeau of Article XXI:b contains several elements which may fall under the ‘self-judging’ scope of the adjectival clause, ‘which it considers’. In this dispute, the panel addressed the invoking Member's authority to articulate its ‘essential security interests’ and ‘the ‘necessity’ of the measures [taken] for the protection of its essential security interests’ (paras. 7.131, 7.146). It found that an invoking Member has conditioned authority to assert what it considers to be its ‘essential security interests’ (para. 7.98), and unrestrained discretion to determine the ‘necessity’ of measures taken to protect those interests (para. 7.147).

3.5.1 Limited Discretion to Designate Concerns as Essential Security Interests

The panel conditioned Members’ discretion to identify their essential security interests in disputes in two ways. First, a Member's determination of its ‘essential security interests’ had to acknowledge ‘the particular situation and perceptions of the state in question’ over time (para. 7.131). However, the qualifying word ‘essential’ suggested ‘a narrower concept’ – as those generally ‘relating to the quintessential functions of the state, namely, the protection of its territory and its population from external threats, and the maintenance of law and public order internally’ (para. 7.130).

Second, the conception of ‘essential security interests’ had to be limited by a Member's ‘obligation to interpret and apply Article XXI:b(iii) of the GATT 1994 in good faith’ (para. 7.132). The obligation of good faith was both within the WTO's ‘normative environment’ (Koskienniemi, Reference Koskienniemi2006) but was also found within the ‘general principle[s] of law and ‘principle[s] of general international law which ‘underlie[s] all treaties’, and as codified in the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (para. 7.132).Footnote 25 The implicit condition of good faith was an assertion by the panel that invocations of GATT exceptions cannot constitute abusive exercises that circumvent their WTO and GATT commitments– that is, the protection of domestic trade or commercial interests under the cloak of a legitimate public policy objective (paras. 7.98, 7.132–7.133).

The panel then elaborated as to how good faith informed the sufficiency of factual and legal evidence required for a proper invocation of Article XXI:b of GATT. Both elements, the ‘emergency in international relations’ and an invoking Member's ‘essential security interests’ needed to be balanced together (para. 7.135). The panel's full explanation is worth consideration:

The less characteristic is the ‘emergency in international relations’ invoked by the Member, i.e. the further it is removed from armed conflict, or a situation of breakdown of law and public order (whether in the invoking Member or in its immediate surroundings), the less obvious are the defence or military interests, or maintenance of law and public order interests, that can be generally expected to arise. In such cases, a Member would need to articulate its essential security interests with greater specificity than would be required when the emergency in international relations involved, for example, armed conflict. (para. 7.135)

As the emergency at issue was close to ‘the “hard core” of war or armed conflict’ (para. 7.136), the panel required less specificity regarding its articulation of its essential security interests. Due to Russia's refusal to supply any factual or legal arguments in this dispute, the panel had limited information. Russia had referred to ‘certain characteristics of the 2014 emergency that concern the security of the Ukraine–Russia border’ (para. 7.136). Looking to Russia's domestic laws and ‘common knowledge’, the panel noted Russia's ‘allusiveness’ but concluded that Russia's articulation ‘cannot be considered obscure or indeterminate’ (para. 7.137). In addition, the panel considered evidence that the United Nations General Assembly had ‘recognized’ the character of the 2014 emergency ‘as involving armed conflict’, affecting ‘the security of the border with an adjacent country’ and exhibiting the ‘features identified by Russia’ (para. 7.137). More importantly, the panel found ‘nothing’ in Russia's articulation of its essential security interests’ that suggested ‘a means to circumvent its obligations under the GATT 1994’ (para. 7.137). Accordingly, Russia's articulation was found to be ‘minimally satisfactory in these circumstances’ (para. 7.137).

More importantly, the panel emphasized the obligation of good faith to consider the connection between Russia's essential security interests ‘with the measure at issue’ (para. 7.138). Specifically, the panel emphasized good faith was ‘crystallized in demanding that the measures at issue meet a minimum requirement of plausibility in relation to the proffered essential security interests’ (para. 7.138, emphasis added).

The panel scrutinized Ukraine's characterization of the 2016 measures to consider connections between these measures and the evidence that had satisfied the panel as to the ‘emergency in international relations’ (para. 7.141). The panel found Ukraine's decision to pursue economic integration with the European Union ‘cannot reasonably be seen as unrelated’ to the events that led to the ‘emergency in international relations’ during which Russia adopted its measures (para. 7.142). In addition, the panel considered Russia's 2014 measures (that operate to ban transit of goods subject to Russian sanctions from transiting across Russia from its border with Belarus).

The panel likewise found these measures were not ‘so remote from or unrelated to, the 2014 emergency, that it is implausible that Russia implemented the measures for the protection of its essential security interests arising out of that emergency’ (paras. 7.143–7.145, emphasis added).

The panel carefully avoided consideration of the motivations of Russia (that is, whether they were, in fact, retaliatory). Instead, the panel found Russia's measures were taken ‘specifically to prevent circumvention of the import bans’ in response to sanctions imposed on Russia by other countries, in response to the emergency in international relations (para. 7.143). Such evidence was seen to find a relation between Russia's measures and the identified time of emergency in international relations (paras. 7.143–7.145). As such, it was plausible Russia implemented its measures for ‘the protection of its essential security interests arising out of that emergency’ (para. 7.145). As explored in Section 4, the economic analysis argues that such circular assessment of the plausibility of this connection is lacking.

3.5.2 Unlimited Discretion to Determine ‘Necessary’ Measures for the Protection of Its Essential Security Interests

With so much attention spent on what elements of Article XXI:b are not self-judging, there is little analysis on what was subject to the unilateral determination of the invoking Member. Still, the panel interpreted the chapeau of Article XXI:b as granting Russia sole discretion to determine the actions ‘necessary’ for the protection of its essential security interests (para. 7.146).

Our economic assessment questioned the depth of objective review in this dispute, considering the analysis revealed Russia's economic motivations. Perhaps, in light of this, a stricter ‘necessary’ test may have been warranted. For example, the panel could have observed the Article XX ‘necessity’ test and undertaken a ‘holistic’ process of ‘weighing and balancing’ the importance of the objective, the contribution of the measure to that objective, and the trade-restrictiveness of the measure’.Footnote 26 If so, the panel may have found there was no clear evidence demonstrating that Russia's measures contributed to the protection of its essential security interests.

Of course, the obvious difference between Articles XX and XXI is that Article XXI:b qualifies that a Member may take any action ‘which it considers necessary’, whereas Article XX does not. The panel cited its historical consideration to observe that the matters between these two types of exceptions were of a ‘different character’ (para. 7.98(a)). Nevertheless, it is clear the panel was prepared to consider a plausible correlation between the measures at issue and the events that led to the emergency in international relations. However, it did not go so far as to scrutinize the level of protection or whether there is ‘a genuine relationship of ends and means between the objective pursued and the measure at issue’.Footnote 27

4. Economic Interests Casting Doubts on Plausibility and Good Faith

The legal analysis considers the outcome of the panel in a rather positive manner since it asserted the principle that recourse to Article XXI is justiciable and not an easy prey of a self-judging standard. This is indeed a positive message to the international trading system as another building block towards predictability.

Yet, from an economic point of view, such assertion of judicial review constitutes only a first step towards a complete assessment of the arguments put forward by both parties. As pointed out earlier in section 3.2 and eloquently put forward by Lapa (Reference Lapa2020) the ‘level of specificity’ required from Russia to identify ‘the situation of emergency in international relations’, was quite low. Such a light ‘burden of proof’ applied by the panel made it easier for Russia to ‘justify its compliance with the requirements under GATT Article XXI’ (Lapa, Reference Lapa2020).

This section therefore focuses on the substantial issue that the panel had not examined, that is how Russia linked its measures with the requirements under Article XXI, and to what extent such measures meet the minimum requirement of plausibility referred to in the panel report as being essential to crystalized good faith (para. 7.138).

While the panel may have found that measures ‘necessary’ for the protection of essential security interests were left to the discretion of Russia, there was clearly great effort to point out elements of Article XXI without the necessary information to consider the plausibility of essential security interests or whether Russia had implemented measures in good faith and that were plausibly related to its articulated essential security interests. As explained by Lapa (Reference Lapa2020), ‘the fact that Russia has not adopted a full embargo, but rather applied certain restrictive measures’ was not considered by the panel. In addition, since such measures are in contradiction with ‘the aim of the protection of national security’, it would have been essential to fully understand the rational underlying their application.

Moreover, one may wonder the value of the judicial review of measures undertaken under Article XXI without the necessary information to consider the plausibility of essential security interests, or whether the actions taken to protect such interests were, in fact, necessary and undertaken in good faith. Had the panel requested the relevant data to assess the ‘good faith’ application of the measures adopted by Russia, it would have been evident that such measures were not tenable in the absence of a plausible connection to the protection of national security interests.

Analyzing trade flows demonstrates a clear drop in Ukrainian exports to Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, and evidences that the selection of targeted goods follows a tariff revenue rationale is inconsistent with essential security interests. As provided in the next section, this analysis questions the prima facie rationale of first, the 2016 Belarus Transit Requirements and, second, the 2016 Transit Bans on Non-Zero Duty Goods and Resolution No. 778 Goods.

4.1 Ukraine Trade Profile

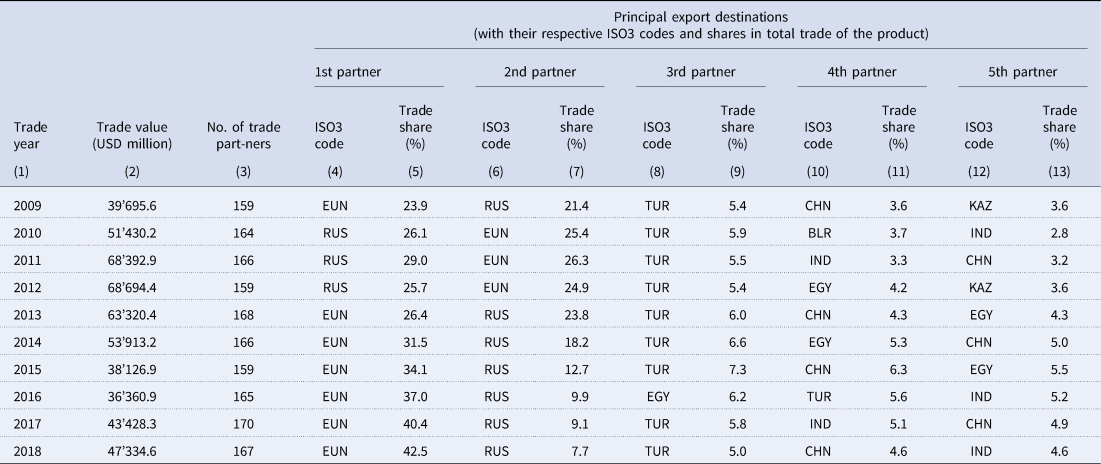

As can be seen in Table 1, Ukrainian exports are mainly oriented towards the European Union and Russia. While the importance of the former in Ukrainian exports was relatively stagnant until 2013, we observe a significant change in 2014 with an increase by 5 percentage points. Even more striking is the reduction in the share of Russia during the same period.Footnote 28 Interestingly, if the objective of the measures enacted by Russia was to dilute the rapprochement of Ukraine and the European Union, the trade data show exactly the contrary.

Table 1. Ukraine principal trading partners, 2013, USD million

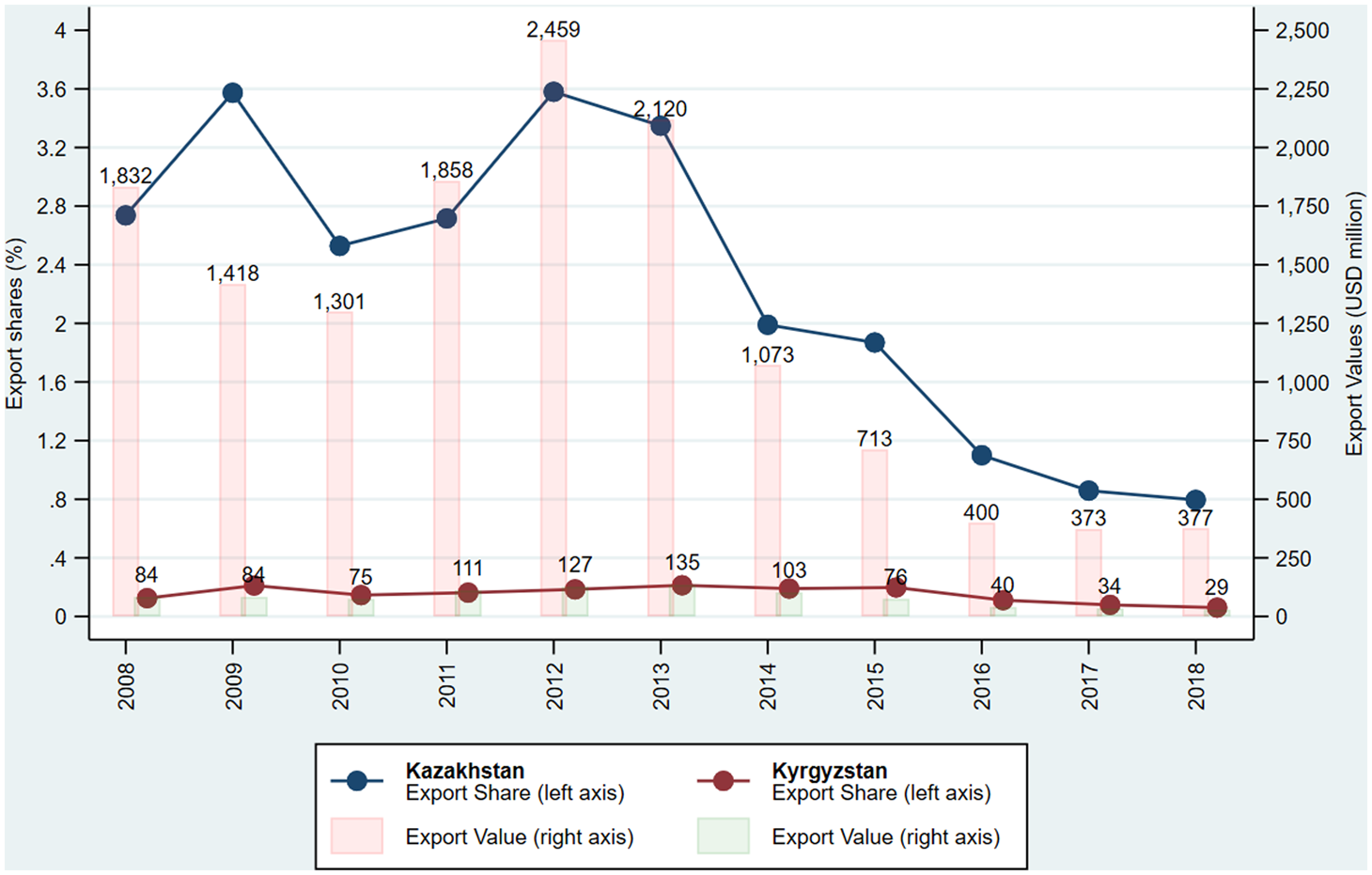

In the context of the dispute at stake, despite the relatively small export shares to Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan reported in Figure 2, important amounts of trade are involved. We can observe a 49% drop in exports to Kazakhstan from 2.1 to 1.07 billion USD between 2013 and 2014 when the first wave of measures was implemented. Such a downward trend continued, although to a slightly lower extent, throughout 2015 (−33.5%) and intensified again in 2016 when the new transit requirements were imposed, with export massively shrinking from 713 to 400 billion USD (−44%). The reaction to the transit requirements of Ukrainian exports to Kyrgyzstan is even more striking, with reductions of trade values by 24, 26, and 47%, respectively in 2014, 2015, and 2016.

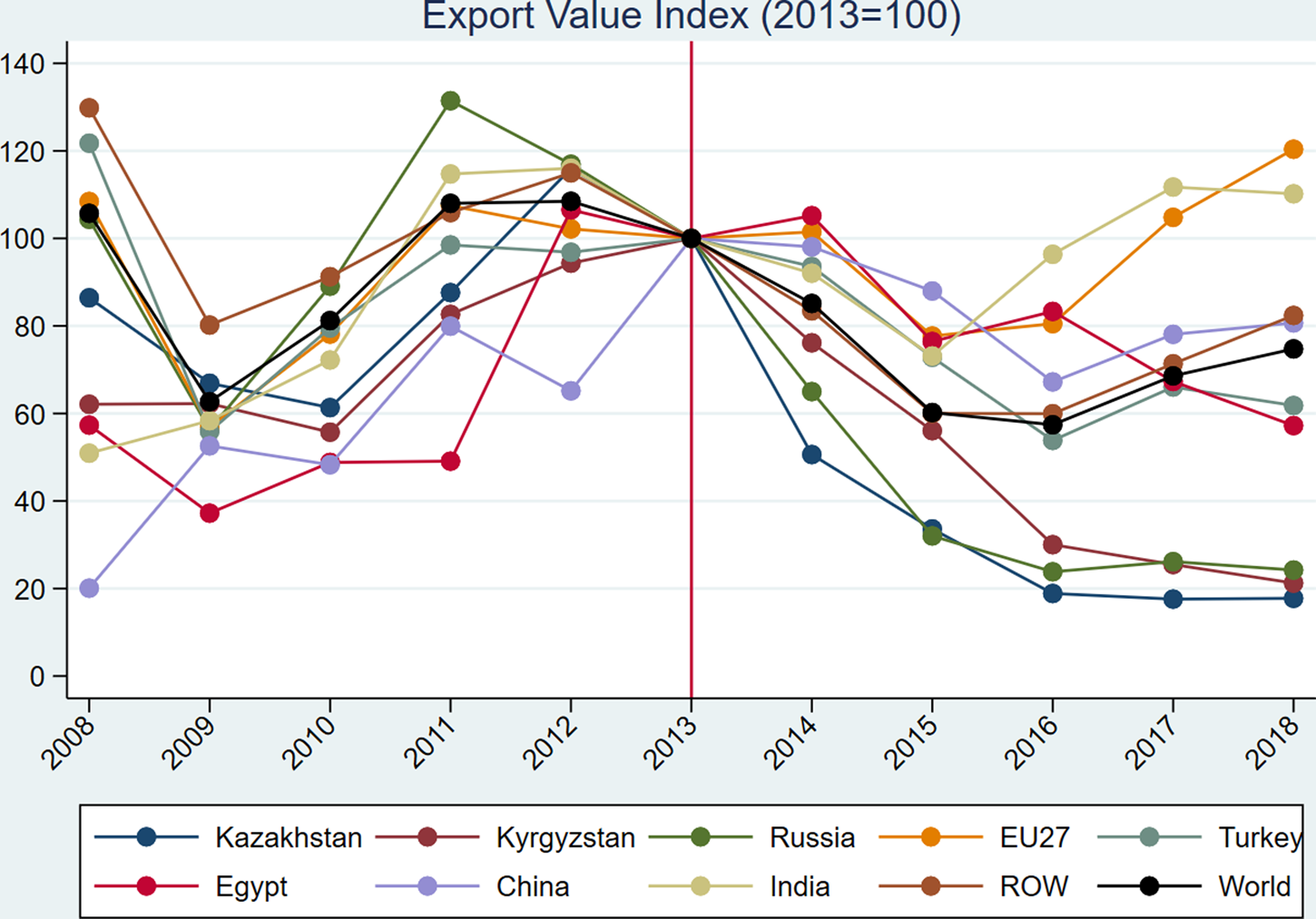

During the period considered, Figure 3 shows that Ukrainian exports decreased to all markets and not only to Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Among Ukraine's main trading partners, only the European Union and India exhibited higher imports from Ukraine in 2017/2018 than in 2013.

However, the negative export trend observed from 2014 to all countries appears to be stronger and more durable for the two destination countries subject to the Russian transit requirements. Indeed, it is particularly interesting to note that while Ukrainian exports decreased to all markets from 2014 onwards, they started to grow again in 2017 to all destinations except Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Even exports to Russia increased in 2017 despite the import ban in place. Therefore, while the three countries followed a similar pattern, clearly distinct from other countries (see dashed-framed area of Figure 3), the additional transit requirements implemented in 2016 examined by the panel are likely to be preventing the Ukrainian exports to Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan to grow again.

Further research is needed to evaluate the welfare impact of such measures and resulting trade effects. More importantly, the question whether this reduction in exports was required to protect Russia's essential security interests cannot be evaluated without conducting a product-specific analysis. In the next section, we identify the products that were the most exported from Ukraine to the two concerned markets before the conflict outbreak and discuss the rational for the selection of the products targeted by the Russia transit requirements.

4.2 Product-Specific Analysis and Tariff Revenue

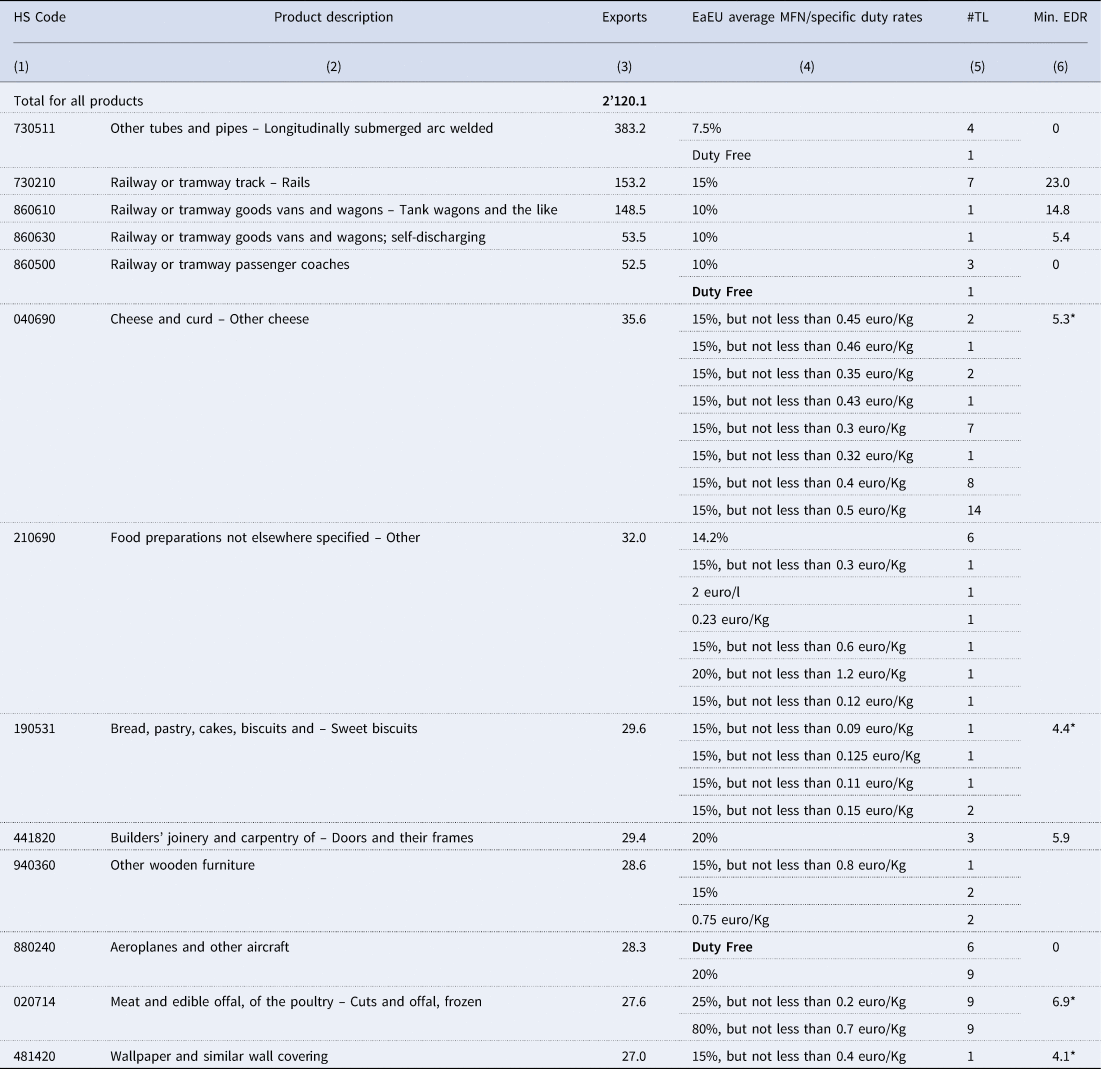

The brief analysis conducted in this section shows that most products exported from Ukraine to Kazakhstan (Table 2) and Kyrgyzstan (Table 3) are dutiable goods, with relatively high tariff rates. Columns (1) and (2) report the product code of the harmonized system at the 6-digit level and its corresponding description. Column (3) shows the export values and is used as reference to sort the data in descending order. Column (4) reports the most-favoured-nation (MFN) rates or specific duty rates applied by the Eurasian Economic Union to the considered product. Column (5) indicates the number of tariff lines (TL) within each tariff subheading (column (1)) to which the specific or ad valorem tariff reported in (4) is applied. Finally, the last column (6) is a rough estimation of the minimum estimated duty revenue (EDR) collected in 2013, prior to the conflict, when the minimum tariff rate reported in (4) for a given product is applied to the export reported under (3). Such value is reported only when a lower bound can be computed.Footnote 29

Table 2. Ukraine – most exported products to Kazakhstan and estimated duty revenue (EDR), 2013, USD million

Notes: Data sorted in descending order of trade value.

* EDR calculated as lower bounds based on the minimum applicable percentage within the HS sub-heading.

Table 3 Ukraine most exported products to Kyrgyzstan and estimated duty revenue (EDR), 2013, USD thousands

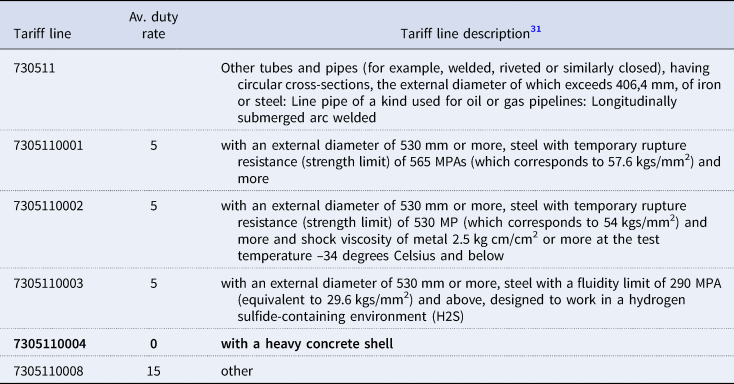

In 2013, the most exported product, tubes and pipes of HS 730511, represented USD 383.2 million of exports to Kazakhstan. Within this subheading, four tariff lines were imposed at an MFN rate of 7.5%. One tariff line was duty free. As we cannot distinguish which portion of trade can be attributed to each line, the minimum EDR is zero. In contrast, rail products of HS 730210 were imposed at a rate of 15%, leading to an estimation of a minimum of USD 23 million of tariff revenue.

Considering together all 11 products for which the minimum EDR could be computed in Table 2, the total amounts to a lower bound of USD 70 million. In the case of Kyrgyzstan (Table 3), such lower bound is 6.9 million distributed over eight products.

This analysis shows that most exported products exported to Ukraine to the two destination countries affected by the measures are mostly dutiable with non-negligible amounts of estimated revenues in 2013. This implies that measures targeting dutiable goods to impose specific transit requirements are detrimental to both parties by affecting a major part of the traffic in transit and generating important tariff revenue losses. Nevertheless, out of the total tariff revenue of the EaEU, such losses may be considered negligible for Russia while targeting dutiable goods ensures that most of the traffic in transit is affected by the measures.

Second, even though Russia's essential security interests were only minimally articulated by Russia, connection between the threat and the measures applied are far from being plausible.

How could products tubes and pipes of tariff line (TL) 7305110004 systematically compromise national interests while those of TL 7305110001 to 7305110003 and of TL 7305110008 would not?Footnote 30 Similarly, how could rail or tram cars for passengers be a threat to national security when their maximum operating speed lies between 140 km/h and 250 km/h (products classified under TL 8605000002 with a non-zero MFN tariff rate of 10%), and are considered ‘inoffensive’ when they reach at least 250 km/h (classified under TL 8605000001 which is duty-free)?

The legal assessment distinguished the GATT ‘necessity’ tests as between Articles XX and XXI, noting that for the security exceptions a panel need not consider specific justifications on which good shall be selected, or evidence of a link between ‘necessary’ measures and the interests at stake. However, it is reasonable to expect such elements to be part of the good faith obligation that underlies the whole GATT, a point emphasized by the panel (para. 7.138). The examples provided in this section clearly show an incoherent treatment of different goods demonstrating that it is quite implausible that such measures are applied with the specific objective to protect essential security interests in times of emergency in international relations.

4.3 Transport Costs and Alternative Routes – What Are the Options for the Future?

The economic study conducted by Ryzhenkov, Saha, Movchan, and Giucci (Reference Ryzhenkov, Saha, Movchan and Giucci2016) already highlighted the challenges faced by Ukraine following the Russia transit requirements. The study reports that as compared to the direct transit route (red arrows in Figure 1, Kyiv-Astana), the indirect route offered by Russia (Figure 1 green arrows) through the Belarus territory represents an increase in distance of about 600 km (+17%), and in time of one to two days for trucks and one day for rail transport.

Figure 1. Transit routes from Ukraine to Kazakhstan

Source: Adapted from Devon, ‘Nuclear Vacuum’ Moore (2012)

In view of bypassing Russia's traffic in transit restriction, a new silk road (Figure 1 black arrows) has been envisaged through the Black Sea, Georgia, Azerbaijan, and the Caspian Sea. In such case, with a distance increase of 1900 km, the transport duration is estimated to increase by six to seven days for trucks, and by a minimum of five days for rail, with limitations due to the ferries capacities in both seas. Based on various assumptions, the authors anticipated a relatively low impact on Ukrainian exports from shifting all cargo to the Belarus route (−13 million, −1.9% of 2015 exports to Kazakhstan). Contrasting these figures to actual data reported in Figure 2 and the 44% drop of exports, we can reasonably conclude that such figures have most likely been underestimated. Finally, the authors also calculated the export losses resulting from the exclusive use of the new silk road to USD 405 million (0.46% of the GDP) and warned about the necessity to expand the ferries’ capacities.

Figure 2. Ukraine exports to Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, absolute and relative values, 2008–2018.

Figure 3. Ukraine Export Value Index (2013 = 100), 2008–2018.

4.4 Discussion on the Preliminary Findings

The data exercise conducted in this paper is only a non-exhaustive overview of the type of data analysis that should have been carried out as part of the panel report to support its conclusions. Economic considerations for the imposition of the transit measures examined by the panel as well as their economic impact are undeniable. Leaving politics aside, the absence of a deeper economic empirical analysis in the panel report casts serious doubts on the ability of the panel to evaluate the plausibility of Russia's essential security interests, and consequently any ‘good faith’ effort to demonstrate a proper invocation of Article XXI:b(iii) of the GATT.

Although not specifically required by Article XXI of the GATT, and in line with Lapa's argument, plausible protection of Russian essential security interests would justify a complete ban of any shipment originating from or having been transited through the Ukrainian territory. But then why did Russia choose to maintain trade, only imposing transit requirements? The panel should have examined the reasons for replacing such a ban or embargo with the imposition of transit requirements through Belarus, including the justifications for such replacement in view of the alleged articulation of Russia's essential security interests. Recognizing the analytical test outlined in Section 3, it is clear the panel sought to leave it to the Member to determine what actions are necessary in times of ‘emergency in international relations’. However, the panel could have considered Russia's decision to increase the length of the transit route through Belarus’ borders (i.e. transit costs) as an indication that the measures were not, at a minimum, plausibly related to Russia's articulated essential security interests. In other words, was there enough assessment done to confirm that Russia had not attempted to merely circumvent its GATT obligations? The information provided in the panel report only allow us to speculate possible reasons that could be related to higher quality of infrastructures and services, as well as enhanced security at the Ukraine–Belarus border posts. It is clear that even in cases of a highly sensitive and political context, there must be factual evidence to consider, even if this meant the panel requested additional information pursuant to Article 13 of the Dispute Settlement Understanding.

The panel sought to address blatant circumvention of GATT/WTO commitments despite the fact that the security exceptions contained some subjective discretion on the part of Russia. But it is clear that even a minimal amount of economic analysis fractures Russia's assertions as to the circumstances and protections sought. The complete ban on non-zero duty goods is a clear example, as the distinction between dutiable and non-dutiable goods calls into question economic considerations that have nothing to do with protection of essential security interests. Instead, this distinction is dictated by tariff revenue considerations. Notwithstanding the panel's finding that Russia may determine the ‘necessity’ of measures taken, this total disconnection between the duty status of traded goods and the articulation of essential security interests rules out the existence of a plausible link between the measures and their alleged objectives. However, it is clear that this consideration did not form a part of the panel's legal assessment of Article XXI:b(iii).

More importantly, the panel devoted a considerable part of its report to emphasizing an obligation of good faith. However, measures targeted towards dutiable goods directly contradict this obligation. It is implausible that only dutiable goods in transit from Ukraine threatened Russia's essential security interests. Generally, such duties are imposed for economic/protectionist reasons. If contribution of the measure to the objective of protecting essential security interests had been a factor, then it would be obvious that the contribution failed. Protection of essential security interests should require a horizontal ban on all imported goods transiting through the territory or on particular goods selected based on security criteria, but not according to their duty status.

In reality, the rationale for such targeted measures implemented by Russia points towards exclusive economic and geopolitical considerations. They could be perceived as another additional form of retaliatory measures for the pro-Europe economic and trade stance adopted by Ukraine, negatively affecting Ukrainian exports. Whether economic retaliatory measures can be used to protect national security by weakening the ‘enemy’ in an international conflict is another question that the panel left unaddressed.

5. Lost in Transit? The Role of the WTO in Essential Security Disputes

In 1947, control over the interpretation of the GATT security exceptions was acknowledged to be a powerful arrow in every country government's quiver (Pinchis-Paulsen, Reference Pinchis-Paulsen2020). For the more powerful, developed countries, specifically the United States, the security exceptions were crucial in on-going geopolitical battles that took place in the mid-twentieth century. For the developing countries, these security exceptions were an opportunity for achieving economic development and full employment – goals which required greater management over trade (and use of trade restrictions) not less, as promoted by the United States. Thus, the drafting of the security exceptions targeted fears of unilateral action and abuses of the security exception – for example, special interests clothed in the mantle of national security. But allocation of responsibility among the country governments (and even, where relevant, the United Nations) also fit into the disputes settlement system of the intended ITO. To support the governments, there would be processes for investigation, consultation, referral to arbitration, and enablement of corrective actions – even for disputes regarding security interests.

A core lesson gained from this analysis suggests there must be more than pro forma reference to WTO rules and good faith (Zarbiyev, Reference Zarbiyev2020). Based on this analysis, justification for the invocation of security exceptions must be held to a high standard – national security measures must be in fact justifiable. Equally important then is not just the existence of this analytical framework but strong regard for the review therein.

Consider, for example, a future dispute involving climate crisis, with growing political demands that view climate crisis as through the lens of security (Jamshidi, Reference Jamshidi2019; Heath, Reference Heath2020a). In such a scenario, it would be crucial to determine whether the climate change mitigation policy measures implemented in response to the environmental risks are connected to the objective of environmental preservation. Whether economic, regulatory, or fiscal, such policies have in general a cross-cutting impact throughout all sectors of society and are likely to directly or indirectly restrict trade. Facts and empirical evidence clearly demonstrating the relevance of the measures and their potential to mitigate climate change are therefore necessary to prevent possible abuse and disguised protectionism. In other words, measures should be evaluated and compared to determine the first best approach, and second-best alternatives that will allow a WTO panel to assess whether, hypothetically, the covered Article XXI:b measures at stake seem plausibly related to an invoking Member's articulated essential security interests. But such an understanding requires a shift in perception of the WTO review process, not as an adversarial one but one meant to facilitate renewed discussion for ‘the development of appropriate governance frameworks at the national level’ (Lang and Cooney, Reference Lang and Cooney2007, 544).

What is most striking about the panel report is not the conclusion that the invocation of the GATT security exceptions should be subject to review; rather it is how hard the panel worked to undertake that review in the absence of factual evidence. In light of the rise of novel security claims (Heath, Reference Heath2020a), it is incumbent on the Members to explore procedures for addressing the scope of Article XXI:a when Article XXI:b is invoked, including peer-review or procedures for engagement with external security experts to consider the relationship between relevant trade measures and the protection of essential security interests. In addition, the Members should rethink the intersection of trade and essential security at the domestic level to aid in the WTO's adaptation towards a politically grounded review, which may find better balance between trade liberalization and Members’ national security policies (Lester and Manak, Reference Lester and Manak2020; Heath, Reference Heath2020a, Reference Heath2020b). As Fuad Zarbiyev (Reference Zarbiyev2020) cautions, a community's ‘lack of reaction is susceptible to being taken as a community license for “anything goes” and can, in the long run, redesign what is visible or worth noticing in that community’. Members must consider the panel report carefully – scholarly assessment is already underway as to how novel assessments of ‘national security’ will reshape the global economy and the multilateral trading system (Heath, Reference Heath2020a; Lester, Reference Lester2020).

6. Conclusion

The Russia–Traffic in Transit panel report offers the most comprehensive guidance for understanding the intersection between national security and trade in the multilateral trading system. From an economic perspective, the application of the outlined legal approach to Russia's measures in this dispute is highly questionable. Indeed, the panel did not require Russia to clearly define its essential security interests, nor did the panel conduct any empirical assessment of the relationship between the measures and such interests. These elements are indispensable to evaluate the real motivation behind the transit restrictions. This calls into question the capacity to rigorously and neutrally rule on the matter.

From a legal perspective, the panel's analytical framework offers future WTO panels the opportunity to check abuses of the GATT security exceptions (Van Den Bossche and Akpofure, Reference Bossche, P. and Akpofure2020). The fact remains that while the panel report answers a significant question about whether GATT Article XXI is wholly self-judging (it is not), there are many questions left unanswered regarding the order of analysis, the applicable standards of review, a respondent Member's burden of proof, and the relationship between the ends and means for protecting essential security interests.

Still, it is abundantly clear that this was a carefully crafted report. The particular circumstances of this dispute – as well as the unprecedented questions before this panel – meant that the panel had to be extremely sensitive to its political nature. Ultimately, the attention to finding a diplomatic path forward failed economic scrutiny, but it met the limits of the legal design of Article XXI:b. In the end, neither Russia nor Ukraine appealed the panel report. Moreover, when the Dispute Settlement Body adopted the panel report, Ukraine noted its disappointment but also acknowledged the panel's findings ‘posed more positive than negative developments for the WTO dispute settlement system’ (Fortnam, Reference Fortnam2019; WTO, 2019).

Acknowledgements

We are highly indebted to Maria Alcover, Chad Bown, Rachel Brewster, Jennifer Hillman, Petros Mavroidis, Federico Ortino, Debra Steger, Isabelle Van Damme, Peter van den Bossche, and Simon Lester, as well as all the participants in the 2019 WTO Case Law Project, for helpful discussions. All errors and omissions are our own.

Annex

Table A1. Tubes and pipes of HS 730511, tariff lines description