No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

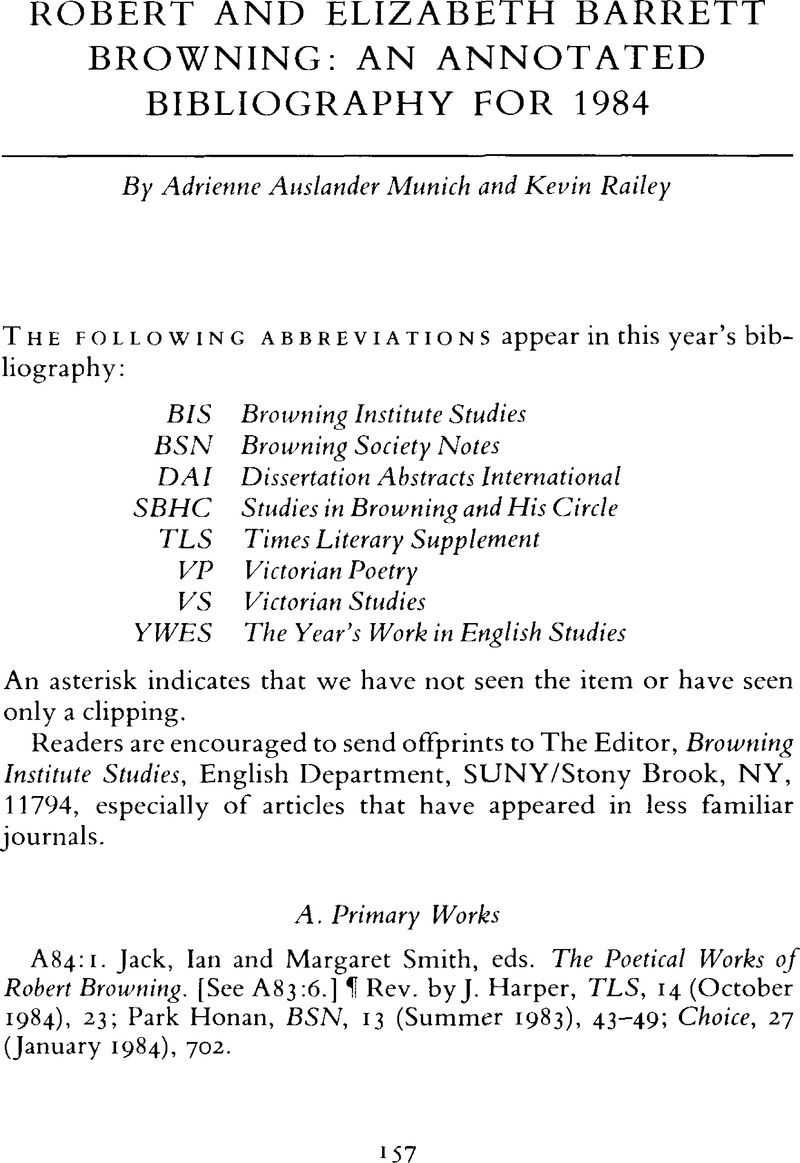

Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning: An Annotated Bibliography for 1984

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 October 2008

Abstract

An abstract is not available for this content so a preview has been provided. Please use the Get access link above for information on how to access this content.

- Type

- Browning Bibliography

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press 1986

References

A. Primary Works

A84:1.Jack, Ian and Smith, Margaret, eds. The Poetical Works of Robert Browning. [See A83:6.]Google Scholar

A84:2.Kelley, Philip and Hudson, Ronald, eds. The Brownings' Correspondence. Winfield, Kansas: Wedgestone Press, 1984. Volume 1: xlviii + 383 pp. Volume 2: xiv + 413 pp.Google Scholar

A84:3.Pettigrew, John and Collins, Thomas J., eds. Robert Browning: The Poems. [See A81:5.]Google Scholar

A84:4.Raymond, Meredith B. and Sullivan, Mary Rose, eds. The Letters of Elizabeth Barrett Browning to Mary Russell Mitford 1836–1854. [See A83:8.]Google Scholar

A84:5.Barrett, Elizabeth Barrett. “Fragment of an ‘Essay on Woman’.” SBHC, 12 (Spring–Fall 1984), 10–12.Google Scholar

B. Reference and Bibliographical Works and Exhibitions

B84:1.Anderson, Vincent P.Robert Browning as a Religious Poet: An Annotated Bibliography of the Criticism. Troy, NY: Whitson, 1983, vii + 302 pp.*Google Scholar

B84:2. “Desiderata for Browning Scholarship.” SBHC, 12 (Spring–Fall 1984), 169. ¶ Five items.Google Scholar

B84:3. “Doctoral Dissertations in Progress.” SBHC, 12 (Spring–Fall 1984), 169. ¶ Three items.Google Scholar

B84:4.Freeman, Ronald E. “A Checklist of Publications.” SBHC, 12 (Spring–Fall 1984), 171–76.Google Scholar

B84:5.Kelley, Philip and Coley, Betty A., comps. The Browning Collections: A Reconstruction with Other Memorabilia. [See B83:3.]Google Scholar

Coover, Chris, Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, 78 (Fourth Quarter 1984), 517–21.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

B84:6.Maynard, John. “Guide to Year's Work in Victorian Poetry: 1983: Robert Browning.” VP, 22 (Autumn 1984), 296–306.Google Scholar

B84:7.Mermin, Dorothy. “Guide to Year's Work in Victorian Poetry: 1983: Elizabeth Barrett Browning.” VP, 22 (Autumn 1984), 292–96.Google Scholar

B84:8.Munich, Adrienne Auslander. “Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning: An Annotated Bibliography for 1982.” BIS, 12 (1984), 189–97.Google Scholar

B84:9.Tobias, Richard C., ed. “Victorian Bibliography for 1983: Browning.” VS, 27 (Summer 1984), 582–83.Google Scholar

C. Biography, Criticism, and Miscellaneous

C84:1.Auerbach, Nina. “Robert Browning's Last Word.” VP, 22 (Summer 1984), 161–73. ¶ “Elizabeth Barrett Browning's celebration of her authority as a woman poet becomes in Robert Browning's major work the apotheosis of an illiterate girl whom the poet loves because she is unheard” (iv). Reference to Aurora Leigh, Men and Women and The Ring and the Book.Google Scholar

C84:2.Baker, W., Glass, S.. “Robert Browning's Iliad: An Unnoted Copy.” SBHC, 12 (Spring–Fall 1984), 148–59. ¶ A Study of Robert Browning's copy of The Iliad reveals that Homer was an inspiration throughout Browning's life, “permitting Browning to ‘dream’” (159).Google Scholar

C84:3.Beck, Ian. “‘The Body's Purpose’: Browning, and so to Beddoes.” BSN, 14 (Spring 1984), 2–20. ¶ Discusses connections between Beddoes' and rb's poetry.Google Scholar

C84:4.Berens, Michael J. “Browning's Karshish – An Unwitting Gospeller.” SBHC, 12 (Spring–Fall 1984), 41–53. ¶ For rb “the Incarnation … must be experienced by each person in his own soul. What matters is whether one will be open to that revelation when it comes. For Karshish, Lazarus is that revelation” (53).Google Scholar

C84:5.Bidney, Martin. “The Exploration of Keatsian Aesthetic Problems in Browning's ‘Madhouse Cells’.” Studies in English Literature 1500–1900, 24 (Autumn 1984), 671–81. ¶ “The real subject of Browning's ‘Madhouse Cells’ is the problematics of imagination, in particular the problematic relation of aesthetic contemplation to a world of process and change” (671).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

C84:6.Black, Jeremy. “King Victor and King Charles: The Historical Background.” BSN, 14 (Spring 1984), 39–49. ¶ Provides the historical background to the events depicted in Browning's play.Google Scholar

C84:7.Blalock, Elizabeth. “The Carnivalesque in Browning's The Ring and the Book.” DAI, 44 (03 1984), 2770A (University of Texas at Austin). ¶ “The subject and central narrative problem of The Ring and the Book is how a lie that presents the illusion of truth can be made to produce a real truth-seeker rather than a reader who passively accepts the artistic image or world as that truth” (2770A).Google Scholar

C84:8.Bogus, Diane S. “Not so Disparate: An Investigation of the Influence of Elizabeth Barrett Browning on the Work of Emily Dickinson.” Dickinson Studies, 49 (06 1984) 38–46. ¶ The poetry of Barrett Browning has a powerful and direct influence on Emily Dickinson; indeed, Emily Dickinson “is in empathy with Barrett Browning” (42).Google Scholar

C84:9.Bolton, Elizabeth. “Browning and the Sublime: A Music of Soul and of Sense.” BSN, 14 (Spring 1984), 21–39. ¶ “Style … in many ways forms the thread of sublimity” (37); Browning's poems serve as mediation between objective and subjective worlds. “Language becomes a music of the soul and the sense” (37). With reference primarily to Men and Women, “Cleon” and “One Word More.”Google Scholar

C84:10.Buckler, William E. “Rereading Henry James Rereading Browning: The Novel in The Ring and the Book.” The Henry James Review, 5 (Winter 1984), 135–45. ¶ James' essay on The Ring and the Book pays homage to rb by following in its form two of the poet's fundamental rubrics: to tell a truth obliquely and to trace an incident in the development of a soul.Google Scholar

C84:11.Campbell, Susie. “‘Painting’ in Browning's Men and Women.” BSN, 14 (Winter 1984), 2–22. ¶ rb's attempt to reach the public by including painting is equivocal; He uses “the ambiguities and difficulties he discovers in pictorial art to discuss such issues as ‘finish’ and the ‘depth’ of a work of art and the integrity of the artist” (9).Google Scholar

C84:12.Chell, Samuel L.The Dynamic Self: Browning's Poetry of Duration. Victoria, B.C.: University of Victoria Press, 1984. 135 pp. ¶ rb's revitalization of the past and hearty acceptance of the present are celebrated aspects of his poetry as are his view of life as endless progress and his quest for the “infinite moment.” Intuition recognizes as indivisible progress what intellect records as isolated facts.Google Scholar

C84:13.Cheskin, Arnold. “‘Jochanan Hakkadosh’ – Rabbi Ben Browning.” SBHC, 12 (Spring–Fall 1984), 134–47. ¶ A wareness “that the one principal in the poem called ‘Tsaddik’ is not Rabbi Jochanan Hakkadosh, but his unseasoned chief disciple … and of Tsaddik's resemblance to Frederick J. Furnivall of the London Browning Society will enable us to enjoy [the poem] as a genuinely interesting allegorical presentation of Browning's earliest reservations about the Society (134).Google Scholar

C84:14.Christ, Carol T.Victorian and Modern Poetics. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1984. ¶ How the Victorian and Modernist poets react against the subjectivity associated with Romanticism by evolving strategies to objectify the materials of poetry. See Index for frequent references to rb.Google Scholar

C84:15.Coates, John. “Two Versions of the Problem of the Modern Intellectual: Empedocles on Etna and ‘Cleon’.” Modern Language Review, 79 (10 1984), 769–82. ¶ Browning's version “… is a disturbing and perhaps truer picture of the modern intellectual than Arnold's straight-forward picture of the tormented seer” (798).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

C84:16.Crowder, Ashby Bland. “Browning's Contemporaries and The Inn Album.” SBHC, 12 (Spring–Fall 1984), 120–33. “In spite of the occasional approbation – mainly from The Athenaeum and the Saturday Review – The Inn Album received rough treatment from Browning's British contemporaries, who were offended by almost all the aspects of the poem” (133). A survey of critical responses.Google Scholar

C84:17.Donovan, Robert Alan. “The Browning Version: A Case-Study in Victorian Hellenism.” Greyfriar, 25 (1984), 62–76. ¶ Due to his non-traditional study of Greek, rb's reading of classical literature is “fresh and immediate,” and, while his translations are “rough and eccentric,” they are valuable. “Separate from the monolithic view of classical civilization developed in universities, rb helped reinvigorate the study of Greek” (74).Google Scholar

C84:18.Edwards, Suzanne. “‘James Lee's Wife’: Robert Browning's Tennysonian Poem.” SBHC, 12 (Spring–Fall 1984), 87–93. ¶ More so than in any other poem, “James Lee's Wife” shows a Tennysonian stance toward nature – that “nature reflects and actually seems to contribute to human attitudes” (88).Google Scholar

C84:19.Erickson, Lee. Robert Browning: His Poetry and His Audiences. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1984. 287 pp. ¶ Traces development of rb's poetry as a process of self-realization requiring the active recognition of others; rb's sense of audience changes from the general reading public to ebb and ultimately to God.Google Scholar

C84:20.Fowler, James Eric. “The Tempest Legacy: Shakespeare, Browning, Auden.” DAI, 45 (10 1984), 1121A (Rice University). ¶ “‘Caliban upon Setebos’ is carefully poised; in the arrested dialectic of its speaker we may glimpse the satirically deflected hesitancies of a poet uncomfortable with contemporary positivist tendencies … Among the three works is intimated a middle way between idolatrous superstition and despairing agnosticism …” (1121A).Google Scholar

C84:21.Friewald, Bina. “The Printing Woman”s Proper Sphere: The Discursive Moments of Elizabeth Barrett Browning's Aurora Leigh.” DAI, 44 (03 1984), 2770A (Concordia University, Montreal). ¶ Explores and contextualizes Barrett Browning's “monumental endeavor, in Aurora Leigh, of constructing a poetics of the female subject” from two theoretical frameworks: intertextual semiotics and feminist literary criticism.Google Scholar

C84:22.Gibson, Mary Ellis. “One More Word on Browning's ‘One Word More’.” SBHC, 12 (Spring–Fall 1984), 76–86. ¶ “One Word More” shares characteristics of both “expressive lyric” and “dramatic lyric” as defined by Ralph W. Rader. “It is the combination of the dramatic and expressive that forms the power of rb's poem” (76).Google Scholar

C84:23.Gilbert, Sandra M. “From Patria to Matria: Elizabeth Barrett Browning's Risorgimento.” PMLA, 99 (03 1984), 194–211. ¶ “…through her involvement with the revolutionary struggle for political identity that marked Italy's famous risorgimento, Barrett Browning enacted and re-enacted her own personal and artistic struggle for identity…” (194). Barrett Browning “located Herself in a re-creative female poetic tradition [that]… imagined nothing less than the transformation of patria into matria…” (195).Google Scholar

C84:24.Glaysher, Frederick. “At the Dark Tower.” SBHC, 12 (Spring–Fall 1984), 34–40. ¶ “To force an anachronistically Jungian or Conradian interpretation on ‘Childe Roland’… falls short of doing justice to the poem, which is really about the struggle of the soul to reach God” (34).Google Scholar

C84:25.Graham, Carla. “Gigadibs' Bible Lesson.” VP, 22 (Winter 1984), 449–54. ¶ All of John 21, not just selected passages, can sharpen our understanding of the issues involved in “Bishop Blougram's Apology” “when the perceptive reader goes from the poem to his Bible and there finds Blougram's ideas in yet another context” (450).Google Scholar

C84:26.Gridley, Roy E.The Brownings and France: A Chronicle with Commentary. [See C83:25.]Google Scholar

C84:27.Harrison, James. “Browning's ‘Caliban upon Setebos’.” Explicator, 42 (Spring 1984), 24–25. ¶ “Caliban is a shrewd and sympathetic portrayal of someone at an early stage of human development as well as a satire on more ‘advanced’ natural theologians. And he is the latter, surely, all the more tellingly for being the former” (25).Google Scholar

C84:28.Harty, Edward R. “The Dramatic Monologues of Robert Browning with Special Reference to his Religious Themes.” DAI, 44 (02 1984), 2477A (The University of South Africa).*Google Scholar

C84:29.Healy, David. “‘Fra Lippo Lippi’ and ‘Andrea del Sarto’ as Complementary Poems.” SBHC, 12 (Spring–Fall 1984), 54–75. ¶ Based on William E. Harrold's conception of the “overpoem,” these two poems need to be read in tandem to produce an “‘overpoem’, whose meaning is different from and greater than that derived from a separate reading of the poems” (55).Google Scholar

C84:30.Hickok, Kathleen. “Elizabeth Barrett Browning.” Representations of Women: Nineteenth-Century British Women's Poetry. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1984, pp. 171–96. ¶ ebb's relation to her contemporary women poets. Not only does she align herself with the male poetic tradition but also she manipulates female literary traditions, resisting or undermining conventional Victorian beliefs regarding women, with Aurora Leigh, the century's most important English poem written by a woman.Google Scholar

C84:31.Hoag, Eleanor. “Note on Fragment of an ‘Essay on Woman’.” SBHC, 12 (Spring–Fall 1984), 7–9. ¶ “This previously unpublished poem … exemplifies … both its author's feminism and her admiration of Pope's work” (7).Google Scholar

C84:32.Hogg, James. “Browning's Debt to Vasari,” in Haslaver, Wilfried, introd., A Salzburg Miscellany: English and American Studies, 1964–84. Salzburg: Institute für Anglistik and Americanistik, University of Salzburg Press, 1984, pp. 50–83.*Google Scholar

C84:33.Karlin, Daniel. “The Sources on ‘The Englishman in Italy’.” BSN, 14 (Winter 1984), 23–43. ¶ Traces some of the poem's sources, particularly to rb's correspondence to ebb and argues that the poem is more complex and serious than usually acknowledged.Google Scholar

C84:34.Katz, Richard A. “‘The Glove’ and the Poets.” BIS, 12 (1984), 155–61. ¶ Browning's depiction of the French Renaissance poet, Ronsard, misrepresents and undercuts Ronsard's poetic stature but offers insights into the French poet's lofty artistic qualities.Google Scholar

C84:35.Ketley, Stephanie Anne. “A Study of Robert Browning's Sordello.” DAI, 45 (11 1984), 1408A (University of Western Ontario), ¶ Although Browning is reasonably accurate about historical details, his greater concern is to illustrate the continuities between historical periods determined by universal human inclinations and experiences, and by the continuities of God's providential ways.Google Scholar

C84:36.Kloesel, Lynn Franken. “The Rogue's Eye: Epistemology and Ontology in Subversive Narration.” DAI, 44 (03 1984), 2759A (University of Texas at Austin). ¶ A study of first-person narratives through a narrational property termed “subversive”: “… the subversive narrator … threatens to wrest control of the text from the author and discommodes the ability of the audience to achieve a reading of the text consonant with authorial intention” (2760A). Reference to “My Last Duchess.”Google Scholar

C84:37.Knoepflmacher, U.C. “On Exile and Fiction: The Leweses and the Shelleys,” in Mothering the Mind: Twelve Studies of Writers and Their Silent Partners, eds. Perry, Ruth and Brownley, Martine Watson. New York: Holmes and Meier, 1984, pp. 103–21. ¶ The exile of the Brownings and the Leweses compared, with particular reference to their earlier model in the Shelleys' elopement.Google Scholar

C84:38.Knoepflmacher, U.C. “Projection and the Female Other: Romanticism, Browning, and the Victorian Dramatic Monologue.” VP, 22 (Summer 1984), 139–60. ¶ rb's “perfection of the dramatic monologue allowed him both to ironize the Romantic process of projection and yet to restore prominence to a Female Other on which both he and the Romantics had projected their desire” (iv). Discusses “Porphyria's Lover,” influence of ebb and relationship to Swinburne.Google Scholar

C84:39.Lammers, John Hunter. “‘Caliban upon Setebos’– Browning's Divine Comedy.” SBHC, 12 (Spring–Fall 1984), 94–119. ¶ The major influences on the poem are Paradise Lost, Genesis, the New Testament and Christian theology in general. It is a religious “satire” whose main target is the idea that Christian revelation can be achieved through logic. Only through “magic – and divine and aesthetic significance of words – can revelation be achieved” (119).Google Scholar

C84:40.Larkin, Susan. “Varieties of Religious Experience in the Poetry of Robert Browning.” DAI, 44 (06 1984), 3696A (New York University). ¶ rb's poetry manifests the four major categories of personality discussed by William James in The Varieties of Religious Experience: the healthy-minded soul, the sick soul, the divided self and the saint.Google Scholar

C84:41.Latane, David Eaton Jr “Energetic Exertion – Reading and the Romantic Long Poem: Blake's Jerusalem and Browning's Sordello.” DAI, 45 (07 1984), 192A (Duke University). ¶ The usual image of the reader in Romantic writing is the ‘friend’ or the ‘brother’; if the reader is willing to toil he may, through his ‘imaginary work,’ co-create the meaning of the text and thus become a brother-poet. The two most extreme texts in this regard are Blake's Jerusalem and Browning's Sordello” (192A).Google Scholar

C84:42.Latane, David Eaton Jr. “‘See you?’ Browning, Byron, and the Revolutionary Deluge in Sordello, Book I.” VP, 22 (Spring 1984), 85–91. ¶ “In Sordello, Book I, rb resorts to a metaphorical description of the levelling of the upthrusting land by the sea (I 213–237)” (85) and concludes this passage with “See you?” “Through the language of metaphor, Browning speaks to the problems of the radicalism of the ‘people’ and to the necessity of liberal change” (90).Google Scholar

C84:43.MacLean, Kenneth D. “Faces of the Alien: The Ideology of the Wild Man in Some English and American Writers.” DAI, 45 (12 1984), 1741A (Indiana University of Pennsylvania). ¶ Studies the Wild Man or Caliban figure as he appears in literature from Medieval times to the twentieth century. Browning uses this figure as “an instrument of literary irony” (1741A).Google Scholar

C84:44.McCusker, Jane A. “Browning's Aristophanes’ Apology and Matthew Arnold.” Modern Language Review, 79 (10 1984), 783–96. ¶ “Aristophanes' Apology, like the complex Parleyings (1887), is deeply concerned with the world of Victorian Britain, particularly with the contemporary poetic situation, and is, to be even more specific, a debate with Matthew Arnold about what constitutes the best poetry for the age” (783).Google Scholar

C84:45.Meidl, Anneliese. ‘A Strafford Manuscript in the Lord Chamberlain's Records Office.” BIS, 12 (1984), 163–88. ¶ Attests to the existence of a Strafford manuscript presented for licensing as early as 27 April 1837. Compares this version to the stage version adapted by Charles Macready, generally concluding that the alterations made the play more suitable for the stage.Google Scholar

C84:46.Mermin, Dorothy. “The Domestic Economy of Art: Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning,” in Mothering the Mind: Twelve Studies of Writers and Their Silent Partners, Perry, Ruth and Brownley, Martine Watson, eds. New York: Holmes and Meier, 1984, pp. 82–101. ¶ The pattern of the Brownings' life together was characterized by an anxious mutual solicitude (“selfishness à deux”) that not only served their marriage but nurtured as well their art. “What they gave each other as poets, it seems, was a psychic space in which they could work freely, and the confidence to explore previously repressed or inaccessible desires and fields of experience” (99).Google Scholar

C84:47.Moser, Kay. “Elizabeth Barrett's Youthful Feminism – Fragment of an ‘Essay on Woman’.” SBHC, 12 (Spring–Fall 1984), 13–26. ¶ Discusses Barrett Browning's feminist attitude in ‘Essay on Woman’ as due to her “youthful personal experiences with contemporary male/female relations” (13) and her “reading of Mary Wollstonecraft's A Vindication of the Rights of Woman” (13).Google Scholar

C84:48.Petch, Simon. “Character and Voice in the Poetry of Robert Browning.” Sydney Studies in English, 10 (Winter 1984–1985), 35–50. ¶ Applies Eliot's “The Three Voices of Poetry” to rb's work. For Eliot, rb, “who speaks in his own voice, cannot bring a character to life” (33); in rb “self, voices and being are terms that replace or circumvent the notion of character” (37), a notion rb constantly reveals as elusive.Google Scholar

C84:49.Peters, John Gerard. “Love, Heaven, and Human Existence: A Note on Elizabeth Barrett Browning's ‘Sonnet XXII’.” SBHC, 12 (Spring–Fall 1984), 32–33. ¶ “‘Sonnet XXII’ is a reaction against utopian idealism…And ultimately, for ebb, joy is internally induced rather than externally induced” (32–33).Google Scholar

C84:50.Rader, Ralph W. “Notes on Some Structural Varieties and Variations in Dramatic ‘I’ Poems and their Theoretical Implications.” VP, 22 (Summer 1984), 103–20. ¶ “…the ‘I’ in dramatic ‘I’ poems stands in (different kinds of) implicit fixed relationship to the poet through creative extension of the natural human capacity to image the action of the self from within and of the ‘other’ from without” (iii). Discussion includes “Porphyria's Lover.”Google Scholar

C84:51.Rogers, Christopher. “Self-Reflexivity in Robert Browning's Poetry.” DAI, 44 (06 1984), 3698A (The University of Toledo). ¶ Browning “achieves an original poetry independent of established forms” (3698A) through the self-reflexivity of his speakers which allows these speakers to comment on themselves and the poetics of the poem.Google Scholar

C84:52.Ross, Blair. “Ripeness is All: Historical Perspective in Browning's ‘Apollo and the Fates’.” VP, 22 (Spring 1984), 15–30. ¶ “Traditionally ‘Apollo and the Fates’ has been interpreted as a clash between optimistic and pessimistic views of the human condition. If, however, the poem is read as a dramatization of a cosmic power struggle…apparent inconsistencies in the plot are resolved” (iii).Google Scholar

C84:53.Rymut, Bernadette Bikus. “Browning's Use of the Grotesque: Studies in Reader Response.” DAI, 45 (07 1984), 193A (St. John's University). ¶ “Following Lee Byron Jennings' definition, the ‘grotesque’ is taken to be the simultaneous arousal of fear and amusement in the reader; this dual reader response is traced throughout ten monologues” (193A).Google Scholar

C84:54.Sharp, Phillip D. “On the Composition of ‘Little Mattie’.” BSN, 14 (Summer 1984), 21–22. ¶ Misdated by twenty years, the poem is found in an 1842 notebook, not published until Last Poems (1862).Google Scholar

C84:55.Sherry, Vincent. “Joyce's Monologues in ‘The Dead’ and Browning's Thought-Tormented Music.” College Literature, II (No. 2, 1984), 134–40. ¶ Joyce records his early reaction to rb in “The Dead,” the story serving as a bridge between Dubliners and the reformed Portrait and marking the point in Joyce's career where the monologue becomes the controlling mode in his fiction.Google Scholar

C84:57.Stephens, Patricia. “Browning's ‘A Woman's Last Word’.” Explicator, 43 (Fall 1984), 35–8. ¶ Proposes a reading of stanzas 6–8 which provides “a more fully specifiable and complete interpretation of the woman's offer of self-surrender” (35).Google Scholar

C84:58.Tarlinskaja, Marina. “Rhythm – Morphology – Syntax – Rhythm.” Style, 8 (Winter 1984), 1–26. ¶ “This paper describes an attempt to find a link between rhythmical (accentual and word boundary) line forms of English verse, and the grammatical (part-of-speech, syntactical) structures that usually fill these forms” (2). Discusses rb, Byron and Pope.Google Scholar

C84:59.Tebbetts, Terrel L. “The Question of Satire in ‘Caliban upon Setebos’.” VP, 22 (Winter 1984), 365–81. ¶ “The critical conflict over ‘Caliban upon Setebos’ can be resolved…if…[one sees that] the poem neither praises nor satirizes: instead, it criticizes with sympathy” (i).Google Scholar

C84:60.Thomas, Charles Flint. “Real Sources for the Bishop's Tomb in the Church of St. Praxed.” SBHC, 12 (Spring–Fall 1984), 160–66. ¶ Discusses the possibility of the tomb of Cardinal Cetive or Cardinal Cetti in St. Praxed's Church being the real source for the poem.Google Scholar

C84:62.Tierce, Mike. “‘Childe Roland’ – A Poetic Version of Browning's ‘Perfection-Imperfection Doctrine’.” American Notes and Queries, 23 (09–10 1984), 10–14. ¶ “… Roland's quest becomes an attempt to reestablish Browning's own, seemingly in adequate, artistic powers” (II). The poem becomes a perfect expression of rb's doctrine.Google Scholar

C84:63.Tucker, Herbert F. Jr “From Monomania to Monologue: ‘St. Simeon Stylites’ and the Rise of the Victorian Dramatic Monologue.” VP, 22 (Summer 1984), 121–37. ¶ “Tennyson's and rb's first monologues may be approached as arch and polemical demystifications of the myth of the autonomous self: the speaker's claim to an exalted subjectivity becomes the impetus for an overthrow that restores him to the contexts he means to escape” (iii). “St. Simeon Stylites” reveals this process and forecasts the eventual direction of Tennyson's monologues.Google Scholar

C84:64.Turner, Craig, ed. The Poet Robert Browning and his Kinsfolk by his Cousin Cyrus Mason. Waco: Baylor University Press, 1983. 240 pp.*Google Scholar

C84:65.Vann, J. Don. “Elizabeth Barrett's Poems (1844).” SBHC, 12 (Spring–Fall 1984), 27–31. ¶ Presents and discusses seven newly discovered reviews.Google Scholar

C84:66.Viscusi, Robert. “‘The Englishman in Italy’: Free Trade as a Principle of Aesthetics.” BIS, 12 (1984), 1–28. ¶ Relates rb's condescending attitude toward Italians to Victorian notions about individual freedoms, expressed in the economic metaphor of free-trade. ‘The Englishman in Italy’ reveals Browning's use of Italy as “stuff for the use of the North” (2), as venture capital for his poetry.Google Scholar

C84:67.Walker, William. “Pompilia and Pompilia.” VP, 22 (Spring 1984), 47–63. ¶ Pompilia's language, allowing for sarcasm as well as subversion, “raises the questions of whether the monologues of The Ring and the Book constitute character concealment or character revealment and whether or not the conventional understanding of character as a unified totality is adequate for an understanding of the work” (iv).Google Scholar

C84:68.Winchell, Mark R. “For All the Heart's Endeavor: Romantic Pathology in Browning and Faulkner.” Notes on Mississippi Writers, 15 (Fall 1983), 57–63. ¶ Compares “Porphyria's Lover” to “A Rose for Emily” in content and imagery, attempting to reveal both rb's and Faulkner's desire to freeze experience in their art.Google Scholar

C84:69.Woodward, Anthony. “The Tragedy of Consciousness in Browning's ‘Cleon’.” English Studies in Africa: A Journal of the Humanities, 25 (1982), 109–16.*Google Scholar

C84:70.Woolford, John. “The Philosophy and Poetics of Power in Browning's Early Work.” BSN, 14 (Summer 1984), 1–21. ¶ As a romantic humanist Browning believed that tyranny is always evil and resistance to tyranny always justified in the tradition of Shelley, Goethe, and Carlyle, but his distrust of political power conflicts with his sense of personal poetic power. With reference to early works, particularly King Victor and King Charles and Pauline.Google Scholar

C84:71.Woolford, John. “Sources for Browning's ‘Cleon’ and ‘Johannes Agricola’.” Notes and Queries, 31 (12 1984), 481–82. ¶ Sources for these poems are discovered in Libellus ii of the Corpus of writings ascribed to Hermes Trismegistus.CrossRefGoogle Scholar