Introduction

Newspapers have played an increasingly important role in depicting cities over the last two centuries. The very idea of a city is conceivable only as a set of images, stories and narratives.Footnote 1 It is thus impossible to conceive of modern urban history without considering journalistic chronicles. At the same time, crime and organized crime are an integral part of the contemporary urban landscape. Consider the positions gained over time by the Italian and non-Italian Mafias in many cities of the world, including New York, Tokyo, Rome, London, Liverpool amd Hong Kong.Footnote 2 Mafias have been defined as phenomena embedded in the deepest layers of society.Footnote 3 Journalism plays a crucial role in revealing their illegal activities. The examples of journalists recently murdered in Mexico and Russia are well known. However, the Italian case has a greater historical depth: several reporters have been murdered since the 1960s,Footnote 4 when the Mafias’ networks expanded, to encompass more urban contexts. The expansion of the Mafias runs parallel with the process of modernization and therefore with the often disorderly and speculative urbanization of the country. Yet such an expansion may occur in any environment marked by the presence of organized crime. The transit points of intercontinental-scale trafficking found their home in the cities. The headquarters needed by the Mafias to do business and obtain consensus were also established in the cities. Moreover, cities were generally home to the markets and businesses from which the Mafias profited. Urban history, forms of Mafia crime and investigative journalism are closely inter-related.

This article deals with the Palermo-based left-wing newspaper L'Ora, perhaps the first Italian example of journalism against the Mafia. It was founded in 1900 by the great entrepreneur Ignazio Florio and had undergone several changes before the Italian Communist Party (PCI) acquired it in 1954 with the aim of expanding left-wing opinion in Sicily. The PCI needed a newspaper to discuss Sicilian autonomy, enshrined by the special statute of 1946, and especially the development of the island. The Christian Democratic Party (DC), the leading political force in Italy, had controlled the national and regional governments, as well as most of the local administrations, since 1947. The social-communists,Footnote 5 however, had a strong base in some rural centres already involved in the post-war peasant mobilizations. The Calabrian Vittorio Nisticò, a former journalist of the pro-communist Roman daily Paese Sera, was called to lead L'Ora. Under his editorship,Footnote 6 the newspaper exerted considerable influence in the public sphere, especially in its denunciation of the Mafia. The first great collective campaign headlined ‘Tutto sulla mafia’ (‘All about the Mafia’) of 1958 led to a Mafia bomb attack on its offices – Figure 1 shows the crater that the bomb caused in the typography – and gave rise to an exceptional season of investigative journalism.Footnote 7

Figure 1. The extraordinary edition of the newspaper following the bomb attack of 19 October 1958.

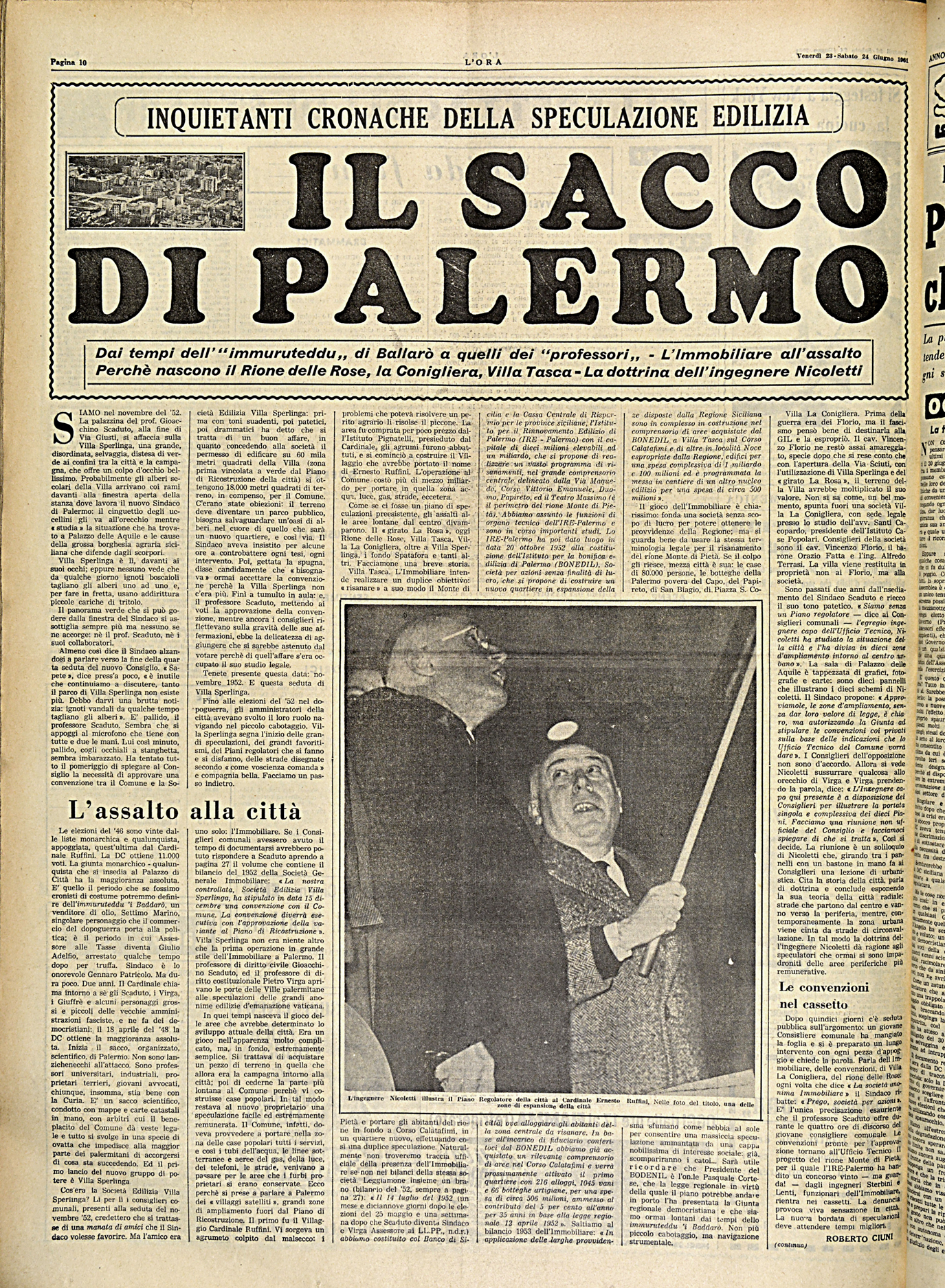

The newspaper has been the subject of numerous discussions and reconstructions, but so far they have been more commemorative and popular than historiographical.Footnote 8 This article seeks to reveal the complexity of some of the dynamics that underpin an important history which extends beyond Palermo and Sicily. It reconstructs the role of L'Ora in denouncing and reacting to the ‘sacco di Palermo’ (sack of Palermo), to use the familiar phrase made popular by the newspaper to describe the profitable real-estate fraud taking place in the city during the early 1960s (Figure 2). ‘Il sacco di Palermo’ was itself the title of a three-part investigative report published by L'Ora in June 1961, even if the role of the Mafia in property speculation was not clear at that time. This article explores the impact of the Mafia groups on Palermo's morphology. The Mafia was able profoundly to modify urban spaces, and to become an agent of transformation in the city, materially expressing its presence on the territory. The interconnection between the Mafia and politics has led to one of the most successful forms of political-criminal production of urban space. Yet a small but combative factor of resistance to the pervasive political-business Mafia system in Palermo also emerged, a field of counter-opinon represented by the newspaper. The article highlights the following factors: the role of criminal groups in redefining the boundaries and spatial relations of the city; the relationship between reality and representation in the complex L'Ora narrative concerning organized crime; the roles it played as autonomous investigative centre and outpost of democracy; its part in the slow emergence of antimafia in the current sense of the term, as a ‘convergence of institutions, political groups and civil society around the legality issue’.Footnote 9 In preparing this article I have used the newspaper's collection, drawing particularly on investigations into the sack of Palermo and the so-called ‘first Mafia war’, as well as journalistic material not intended for publication (preparatory and confidential materials), court records and police reports.Footnote 10

Figure 2. The investigative inquest on the Palermo building speculation, 23 June 1961.

Builders and mobsters

In 1963, the masterwork movie Hands over the City by Francesco Rosi vividly described property speculation in Italy, taking the case of Naples as a symbol of the irrational and uncontrolled urban growth of the post-war era. Although in absolute terms the phenomenon in Palermo was less widespread than in other Italian cities, it highlighted an epochal change in the ruling classes. The devastation of the Palermo landscape marked the swan-song of the ancien régime, the final dissolution of aristocratic high society. The celebrated Tomasi di Lampedusa's novel Il Gattopardo Footnote 11 – as explained by Piero Violante – intended to depict, along with a moment in Sicilian and Italian history, his own understanding of his present: ‘what Lampedusa in fact described with precision and irony was the decline of his class’ (the aristocracy) for the benefit of the ‘ambitiousness of the middle class’.Footnote 12

L'Ora described property speculation taking place in Palermo as a ‘sack’ perpetrated by the so-called VALIGIO business consortium (Vassallo-Gioia-Lima; a builder and two Christian Democratic leaders), which together with the DC councillor for public works, Vito Ciancimino, destroyed the layout of Palermo.Footnote 13 The city expanded northward, mainly towards the Piana dei Colli (the north-western part of Figure 3). In line with the motto of Mayor Lima, ‘Palermo is beautiful, let's make it even more beautiful’, elegant palaces were replaced by large residential areas in direct defiance of the city's regulatory plan and administrative rules. In this way, the municipal government attempted to deal with the demographic increase, emigration from the countryside and the dizzying expansion of regional bureaucracy. The new buildings provided homes for the ruling class and the new middle class of civil servants who, thanks to the clientelist recruitment managed by the DC, granted the Catholic party a devout electorate.Footnote 14

Figure 3. Palermo and its neighbourhoods. Source: Map Box.

Before the inspection conducted in 1964 by the prefect Tommaso BevivinoFootnote 15 revealed the clamorous series of irregularities involved in the city's urban expansion (rigged contracts competition, fake companies, violation of the city plans), L'Ora had issued warnings on several occasions, highlighting the conspicuous increase in violence in relation to construction. It published a brilliant inquiry (‘Miliardi e sangue nella Palermo del ’62’) by the deputy director, Mario Farinella, in February 1962. The reporter began by interviewing the police authorities. The official approach to the problem is demonstrated by the opinion of a questore (an administrative director of the district police), who described the latest chain of killings as a ‘strange coincidence’, suggesting it was not the Mafia who were responsible but ‘criminals with a Mafia mentality’. ‘Commissioner’ – remarked his deputy to the journalist – ‘it is better to let it go…Let's not talk about it; we are Sicilians: why do we have to denigrate our land in this way?’Footnote 16

The articles by Farinella showed the Mafia's ability to develop business networks involving landlords, builders, public administrators, municipal officials and credit institutions, as well as the growing conflict between the rival gangs. The attention of L'Ora, however, soon focused on specific characters who came to prominence because of the large amounts of money that they made. One of them was Francesco Vassallo, the fourth of 10 sons of a teamster, who came from the Tommaso Natale borgata (outlying suburb). During wartime and the post-war period, he devoted himself to trading in dairy products and other foodstuffs, moving between legal and illegal markets. His marriage to the daughter of an ancient Mafia family, the Messina, allowed him to gain a monopolistic role in the sale of slaughtered meat and agricultural products. However, it was the building industry that provided the launching pad he needed: in 1952, he obtained a contract to construct the sewerage systems in two suburbs, Tommaso Natale and Sferracavallo, after which, thanks to a series of contracts to build public and residential buildings (especially schools), he became the Palermo builder par excellence. Vassallo owed his fortune to the support of municipal and provincial offices, as well as banks.Footnote 17 He therefore reflected a new kind of relationship between the Mafia and politics, as if it had become impossible to distinguish the mafioso from the politician.Footnote 18 In fact, they were two sides of the same modernization process:

This is the fundamental cause – as Raimondo Catanzaro explained – of the intertwining between the Mafia and Christian Democrat politicians in Palermo that appears so strongly organic. The process of social mobility triggered by the enormous amount of public resources provided by the state and by local public and economic development bodies, creates opportunities for the renewal of the leadership of both the DC and the Mafia groups.Footnote 19

For a long time, L'Ora was interested in Angelo La Barbera, who, together with his brother Salvatore, was a prominent figure in the Palermo Mafia in the 1950s and 1960s. He gained popularity when he was the head of the Palermo CentroFootnote 20 family, while his criminal beginnings passed unnoticed. The Palermo Mafia had long been underestimated; it had been less exposed during the previous years and therefore less visible than its rural counterpart. After World War II, it was believed that the Mafia served only to ensure the subordination of the peasants to the landowners. The conflict and post-conflict situation had given a central role to the illegal market and especially to the smuggling of grains, and therefore to the latifundiumFootnote 21 and to the agrarian economy, while the urban context had lost much of its importance.Footnote 22 The phenomenon was depicted as the by-product of traditional and agrarian society. Only a few left-wing observers identified notables like don Calogero Vizzini from Villalba and Giuseppe Genco Russo from Mussomeli,Footnote 23 the leading exponents of the Mafia. Multiple studies have shown that they were not simply tools of the agrarian power structure; though they had been organizers of co-operatives and intermediaries in the transfer of land from the landowners to peasants, they had also taken advantage of the collective movements’ actions after the two world wars.Footnote 24 The same studies have rediscovered Palermo and its urbanized countryside as the original site of Mafia infection, focusing on the ancient relationships between the phenomenon and dynamic sectors (international citrus markets, sulphur-mining industries) of the Sicilian economy. Vizzini himself was a great mining entrepreneur. This factor must be underlined in order to understand how much and for how long the urban component has been underestimated in the debate on the Mafia. In short, in the 1950s, the Mafia was seen as a metaphor for backwardness and underdevelopment and thus irreconcilable with modernity.

The La Barbera brothers were a part of the same milieu as Vassallo – they were also sons of a teamster and came from the Piana dei Colli. Unlike Vassallo, who essentially established himself as a builder, they climbed to the top of the Mafia hierarchy, competing for leadership against the ancient Greco family. They were native to the Partanna-Mondello borgata; they were not descendants of a venerable Mafia dynasty; their personal histories were typical of common criminals: Salvatore was charged with armed assault and aiding and abetting in 1942; Angelo with sexual assault in 1942.Footnote 25 Their careers continued with robberies, the illegal possession of weapons and racketeering. But let us recall the Angelo La Barbera portrait provided (Figure 4) by Mario Farinella in L'Ora (Mario Farinella, il ‘boss’ che ha fretta):

He played the boss role of the 1960s perfectly, performing the traditional Mafia model only with regard to arrogance, contempt for the rights of others, the subtle art of nurturing relations with offices, public bodies, political personalities, while he nourished aversion and disdain for what in some circles were seen as the ancient virtues of the Mafia (prudence, patience, accommodation)…He chose the most modern and lucrative business sectors that Palermo could offer: contracts, transport of materials, construction sites, property speculation and smuggling. Genco Russo, the latifundium, cattle rustling, the lean and bitter Sicily of Don Calò and Vanni Sacco, the Sicily of bloody gardens, battles and defeats on the roads of Corleone among the men of Dr. Navarra and the followers of Liggio, seem to belong to the prehistoric Mafia even if a few years have passed since those terrible events.Footnote 26

Figure 4. The potrait of Angelo La Barbera by Mario Farinella, L'Ora, 22 October 1963.

What did the reporter mean? La Barbera's Mafia seemed new to him when compared to that of Vizzini, Vanni Sacco and Genco Russo, who were considered representative of the traditional model. The substitution of a ‘new’, violent and urban Mafia in place of an old, meek and rural one was an idea that re-emerged strongly in those years. In this case, the new Mafia would be linked to building speculation and trafficking in tobacco and drugs. But the dichotomy old/new Mafia was historically present in the debate (and also in the Mafia ideology, in another sense)Footnote 27 and cyclically proposed by various observers. But this distinction simplifies the reality, given that – to borrow from Giovanni FalconeFootnote 28 – ‘there is always a new Mafia ready to supplant the old one’.Footnote 29 Apart from this, the idea, equally widespread at the time, that a ‘transplant’ of mafiosi from the countryside to the city had occurred did not correspond to reality: it was rather the city that, as it expanded, embraced the territories traditionally controlled by Mafia families of the borgate that surround Palermo and whose agricultural income became urban rent, thus immensely increasing in value.

In order to improve his situation, Angelo La Barbera embarked in 1949 for New York. There, working as a longshoreman, he met the mafioso Antonino Marsiglia who instructed him ‘about the methods used by the Mafia, using them as soon as he came back home to create…his economic fortune’.Footnote 30 Upon his return to Sicily, he became a transporter of construction materials. His entry into the Mafia circles of Palermo city was sponsored by Bartolo Porcelli, the well-known boss of the Pallavicino borgata. In 1952, La Barbera and Porcelli took joint possession of a trucking company, but not before murdering its owner, the Mafia member Eugenio Ricciardi. La Barbera was denounced for the murder together with the leader of the Acquasanta cosca, Gaetano Galatolo; however, he was acquitted of the charges by virtue of testimonies made in his favour. The Ricciardi affair, therefore, paved the way for La Barbera to assume command of the family of Palermo Centro in 1955, dismissing his former companion Marsiglia and making his brother Salvatore his lieutenant. The La Barberas soon managed to monopolize the interests of the central-northern area of the city, in opposition to the central-southern ones, extending their hegemony over the suburbs of Resuttana, San Lorenzo and Partanna-Mondello.Footnote 31

In this way, the La Barberas encountered the political-administrative circles of building speculation and particularly the Christian Democrat Salvo Lima.Footnote 32 Farinella continued his biographical sketch as follows (La Barbera: il boss che forse pagherà per tutti, Figure 5):

[Angelo La Barbera] very willingly travelled and he always used the plane for his quick movements. His favourite destination was Rome, sometimes Milan. In the capital, especially, he had formed his heterogeneous but high-ranking group of friends: you could see him hanging around indifferently with top-level mobsters (such as his former partner and friend [Rosario] Mancino, Lucky Luciano, Nick Gentile), men from the political environment, fixers…From the sweet and rarefied Roman atmosphere, the old Mafia of the Greco family of Ciaculli [a borgata in the south of Palermo], the Mafia that had sworn to destroy him must have seemed to him so rough, archaic and annoying!Footnote 33

Figure 5. The potrait of Angelo La Barbera by Mario Farinella, L'Ora, 23 October 1963.

These flights seemed to Farinella to be evidence of modernity, as did their purpose: the smuggling of narcotics and cigarettes. In this regard, the relationship between La Barbera and Rosario Mancino, an Italian-American trafficker, was particularly fruitful. In 1964, Mancino was described by the prosecutor Cesare Terranova (killed by the Mafia in 1979) as a ‘skilled and clever mafioso devoted to shady financial operations and drug trafficking’, close to Lucky Luciano, ‘one of the most fearsome exponents of American gangsterism’.Footnote 34

International trafficking was not a new dimension of the Mafia's criminal activities. It has been a constitutive aspect of the Mafia phenomenon since the last quarter of the nineteenth century: however, at the time, it seemed to be innovative in the eyes of those, like Farinella, who had grown up challenging the Mafia of the interior whom they blamed for terrorist reprisals against peasants. It was Mancino, therefore, who linked the La Barberas to the narcotics market. It is no coincidence that Angelo took part in the famous Palermo meeting at the Hotel des Palmes (October 1957) between American and Sicilian Mafia leaders, which was intended to rationalize international drug trafficking in view of the forthcoming shutdown of the Cuban base of operations, on account of the Castro revolution. The news, however, remained secret until L'Ora published it on the occasion of a vast anti-drug operation in August 1965, which led to the arrest of Genco Russo, Frank Coppola, Giuseppe Magaddino and other bosses involved in the business.Footnote 35 Therefore, through construction speculation and drug trafficking, Angelo and Salvatore La Barbera emerged from social and economic marginality, becoming (for those who did not want see the truth) reputable entrepreneurs. They lived in distinct neighbourhoods that they themselves had built by virtue of a clientelist political system, responsible for the destruction of much of the monumental heritage of Palermo.

A combative newspaper

L'Ora established itself as a democratic outpost and, at the same time, as an autonomous investigative centre when the parliamentary commission of inquiry on the Mafia (Commissione parlamentare d'inchiesta sul fenomeno della mafia in Sicilia) was formed.Footnote 36 The newspaper had contributed greatly to the establishment of the Commission, since the legislative proposals on the subject had followed the dynamite attack to the newspaper's office in 1958. The creation of the Commission was due to the increase in Mafia violence and particularly to the Ciaculli massacre (see below), but also to the emergence of the ‘centre-left’ at the national and regional governmental level, as the result of the alliance between the DC and the Italian Socialist Party (PSI). Nisticò was acutely aware of the importance of the Commission, which had long been demanded by the left, so he decided to support it any way he could, by making the newspaper investigations available, giving weight to its activities and also publishing its documents.

I want to quote an unpublished and noteworthy source: it is a memo delivered by Vittorio Nisticò to the Commission of Inquiry during his hearing, on 18 January 1964. The document anticipated the findings of the Bevivino report on property speculation, shedding light on the network of relationships that existed between the municipal administration, Mafia gangs and economic initiatives: it gave an idea of the investigative capability of the newspaper and of its willingness to work in synergy with the Commission. It is not known why the document was not included among the annexes to the Commission's final report in 1976:

Limited in their scope – wrote Nisticò – by the objective difficulties of investigation and verification that every newspaper encounters, these notes illuminate some aspects of the most recent Mafia activity in the city of Palermo and integrate the picture provided by the investigations conducted in the past by our newspaper, the copy of which is presented on the same date to this Commission.Footnote 37

The memorandum described the predominance of the Mafia in the Mercati generali (urban wholesale markets), a subject that the newspaper had also dealt with in previous years. Of greater interest, however, was the part concerning property speculation in building areas: ‘it is painful to note – wrote Nisticò – that…there has not been a single act of the municipal administration which appears to be aimed at controlling, curbing or preventing the Mafia…exercising a real construction racket in the city of Palermo’.Footnote 38 The director also reported a series of observations submitted to the 1959 regulatory plan by notorious individuals considered to belong to the Palermo Mafia.

Observation no. 690 presented by Mancino Rosario, dangerous mafioso, accused of serious crimes, member of the La Barbera gang, fugitive from justice. The applicant, as the owner of a building built in Via Pietro Geromia…calls for the removal of the extension of Via Padovani [that partially covered Via Geromia, disturbing his construction plans]. This was fully accepted. The construction of the aforementioned building was completed by Mancino in 1960 and between 1960 and 1961 several apartments of which the building consists were individually sold by Mancino as shown by the relevant transactions registered in his name…It would appear to the police that the building in question was built by Mancino in partnership with the brothers Salvatore and Angelo La Barbera. The building consists of seven floors. It is to be reasonably believed that for this construction, as well as for the many others he undertook in these years, Mancino must have been in constant contact with the various competent municipal offices.Footnote 39

Even more shocking, Nisticò noted, were the remarks No. 1340 and No. 1341 presented by Nicolò Di Trapani, a dangerous mafioso, who was denounced for various crimes and arrested on 27 June 1962: ‘it is one of the most serious cases of favouritism towards notorious mafiosi, contrary to the general interest of citizenship, and directly connected with serious episodes of crime and precisely with the murder of the mafioso Agostino Caviglia and the attempted murder of the mafioso Vincenzo Di Maria’.Footnote 40 Di Trapani's appeal concerned property sited between Via Notarbartolo and Via Lazio, an area marked by a rapid increase in value and an equally rapid speculative development.

One of the irregularities reported is emblematic of the Mafia's modus operandi. The regulatory plan had envisaged the construction, on a lot owned by Di Trapani and Matteo Citarda (another mafioso), of an elementary school. The owners of the area obtained the right to move the school building to other land. Once the request had been granted and before the regulatory plan became executive by decree of the president of the region, Di Trapani and Citarda built a nine-storey residential building. Nevertheless, the amendment of the regulatory plan determining the transfer of the school, approved by the Department of Public Works and ratified by the municipal administration, was subsequently rejected by the decree of the president of the region that redefined the area for school buildings. The apartment building built by Di Trapani and Citarda in partnership with the builder Girolamo Moncada was therefore illegal in every aspect.Footnote 41 Nisticò concluded in this way:

The cases reported here, for the first time, which we have been able to ascertain and document, are obviously purely illustrative and indicative. However, they serve to demonstrate…how the inclusion of the Mafia in the expansion of the city's economic life, with the consequences of distortion of the laws of the market, bullying and violence, has been facilitated at best by serious shortcomings and omissions on the part of the public authorities, despite the repeated reports and solicitations also made by our newspaper.Footnote 42

Meanwhile, the press campaign against organized crime continued. In an unsigned article published in July 1963 headlined ‘Politica e violenza a Palermo’ (Politics and violence in Palermo), Nisticò explicitly accused the municipal administration of complicity with the Mafia. The references were to the local DC leaders of Amintore Fanfani's faction, the provincial secretary Giovanni Gioia, Mayor Lima and his assessor of public works Vito Ciancimino. Moreover, the position of Lima in the party became more precarious when a voluminous report regarding his activity was handed over to the national secretary Aldo Moro by the central inspector Vincenzo Russo.Footnote 43

The parliamentary commission of inquiry and the competent bodies of the state – wrote Nisticò – will investigate possible links (direct protection, complicity, etc.) between Mafia crime on the one hand and the political circles that revolve in and around the Municipality of Palermo…However, a phenomenon of political responsibility seems to us already defined, indisputable. And it consists precisely of the fact that the municipal policy of these years on contracts, construction and licences has fuelled anarchy and a climate of illegality that constitutes the not coincidental background of the entire revival of the Mafia gangs and criminal explosions that have bloodied and terrorized Palermo.Footnote 44

The episode had a judicial corollary. Lima and Ciancimino denounced Nisticò and Farinella, respectively director and deputy director of the newspaper, for defamation: ‘the newspaper L'Ora – Lima stated in his claim to the prosecutor – has achieved the goal of involving political leaders on a personal basis, accusing me of collusion with the Mafia…with the clear intention of drawing political advantages for the party that the same newspaper supports’.Footnote 45 It was not difficult for Nisticò to demonstrate the legitimacy of the assessments made in the article, by referring to the testimonies of personalities invested with public office, scholars and urban planners; by delivering administrative documentation and a wide range of accusations that had appeared in the Catholic and national press, about which the two plaintiffs had never considered referring a complaint to the judicial authority.

Nisticò was able to prove the accusers’ relations with the Palermo mobsters, relying on the above-mentioned inquiry of the prosecutor Cesare Terranova, in the report drawn up in March 1963 by the lieutenant of the Carabinieri Mario Malausa on the complaints from damaged builders:

In the course of this battle – Nisticò wrote in a draft of a defensive memo – we always encountered difficulties and resistance and also dangers. We were never surprised or intimidated. Among these obstacles and resistances we also count, with regret, this trial that we face fully aware that no retaliation will put in doubt the perfect loyalty, the disinterest and the civic commitment to which we have adhered and will continue to adhere, also trusting in the serenity, objectivity and justice that is entrusted with the assessment of the judicial case. In any case we know that even for the journalist, as has been said for the poet, the success of the mission that he has chosen means that he always relies on the facts but with such force as to make him hurt.Footnote 46

The affair ended in favour of the newspaper; Lima and Ciancimino, taking note of the ‘political character and therefore devoid of any personal animosity of the critical comments in the article’, preferred to reject the complaint.Footnote 47 The controversies surrounding the two characters, however, continued by virtue of their permanence at the apex of city politics. Public opinion perceived Lima as the ‘Sindaco degli anni violenti’ (‘The mayor of the violent years’), the greatest symbol of Palermo's political-Mafia power. Nevertheless, although the debate tended to personalize the problem, the responsibility for the misgovernment of the city and the damage created by it remained with the ruling class and especially with the Fanfani group of the Christian Democrats. Ciancimino managed to become mayor of Palermo in 1970, but criticism by the communists and L'Ora forced him to leave office after a few weeks. Subsequently, both the politicians shifted their allegiance from Fanfani and Gioia to Giulio Andreotti.

The legal proceedings constituted only one aspect of a larger operation devised by the Palermo establishment to the detriment of the newspaper. The case of Telestar, an evening newspaper set up in 1963 by entrepreneur Arturo Cassina, cannot be omitted. Cassina was a member of the Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre, close to Cardinal Ruffini and exclusive holder of contracts for road maintenance and sewerage in Palermo. He played a significant role in the city's system of power. L'Ora had been campaigning against him for a long time, highlighting the failure of the Control Commission in the supervision of the contract extensions. Cassina unsuccessfully tried to acquire L'Ora, before creating (without appearing on the board of directors) an ultra-Catholic and anti-communist newspaper, Telestar, and called the press officer of the Palermo municipality, Mario Taccari, to manage it. He also tried to deprive L'Ora of workers and editors, offering them significantly higher wages than those paid by the PCI. The newspaper presented itself from its first issue as the ‘Anti-L'Ora’, challenging its adversary with surprising frequency. The aim was to keep the left-wing newspaper under constant pressure and to show how its campaigns discredited Sicily to the advantage of the PCI and Moscow. According to this perspective, the newspaper was nothing more than a fifth column of the Soviet enemy. Telestar did not have a long life. When Taccari stepped down, the newspaper was left without direction and could only rehash its stance as champion of anti-communism and the profiteering of Palermo, until its closure in 1968.

The city at war

The ‘first Mafia war’ ran from December 1962 until the following summer. Palermo was set alight by clashes between gangs fighting for control of drug trafficking and, in more general terms, for the supremacy over the provincial territory. The conflict involved the two hegemonic factions in the north-western and south-eastern areas of the city, led respectively by the La Barberas from Palermo Centro and the Grecos from Ciaculli.

Historians have typically described this conflict as a ‘dialectic’ between the ‘power syndicate’ and the ‘enterprise syndicate’, between the territorial structures of the families and the mobile business network of smuggling.Footnote 48 According to this thesis, there would have been a contradiction between the two organizational models, given the inefficiency of the territorial structures when it came to ‘manage and redistribute profits of the fruitful long-range activities among the affiliates’.Footnote 49 These ideal-types, in short, can still be considered analytically useful today, although in historical reality they have naturally been intertwined rather than distinct.

The La Barberas had been exercising their territorial leadership over the neighbourhoods of western Palermo for some time, by virtue of the consistent firepower unloaded by them on their adversaries. They were part of the Mafia's Provincial Commission created at the end of the 1950s on American impulse.Footnote 50 The Greco controlled the borgata of Ciaculli from the nineteenth century onwards through management of the guardiani (rural watchmen) and irrigation systems, the abigeato (cattle-rustling) and smuggling and racketeering involved in the production and trade of citrus fruits for local, national and transatlantic markets.

Both the La Barberas and the Grecos participated in narcotics trafficking, mediating between the points of production of raw material (located in the Middle East) and the sales areas for the finished product located in the United States. The two groups operated in concert, financing in various percentages the batches of drugs departing from Sicily: in one important case, however, as reported by L'Ora,Footnote 51 a particular shipment of heroin had a far smaller return than expected. A member of the Palermo Mafia Commission close to the Greco, Calcedonio Di Pisa, justified this by claiming to have been swindled by the American buyers. This led to his murder, which set off a clamorous chain of reprisals between the two groups, marked by bursts of machine gun fire, car bombs and raids on the city streets. As a result the La Barberas lost the war.Footnote 52

The climax was reached on 30 June 1963 in Ciaculli with the explosion of a car packed with dynamite (the aforementioned Ciaculli massacre), which killed seven policemen and made a huge impression throughout the country (Figure 6). The day after the attack L'Ora published an extraordinary edition full of reports and in-depth analysis. An editorial (‘La città deve difendersi’, ‘The city must defend itself’) by Nisticò was a call to all the political and social forces to fight the Mafia's arrogance:

What happened on the Ciaculli front has a final warning value: it's not possible to go beyond it, it's not possible to tolerate it. It is time for an outstanding mobilization of public conscience, for a civil revolt that starts from all classes of the population, to say ‘enough!’ and to ask governments and parties to implement all the constitutional measures necessary to create scorched earth around the Mafia organization.Footnote 53

Figure 6. The L'Ora extraordinary edition published on the occasion of the Ciaculli massacre on 1 July 1963.

It was not by chance that Nisticò used the word ‘civil’, indicating that any effective action against the Mafia could only come from the unanimous effort of institutions, public opinion and civil society: parties, trade unions, journalists, intellectuals, associations, common people, all of whom were ready to take sides against the Mafia. The unanimity invoked by Nisticò demonstrates the attempt to widen the antimafia field: in his opinion, however, it was important to remember that the fortunes of the mafiosi continued to depend on the tolerance of the ruling classes and public authorities.

The Ciaculli massacre was a turning point for several reasons. First of all, it led to the effective constitution of the parliamentary commission of inquest. L'Ora wrote ‘Scatta l'anti-mafia’ (‘The anti-mafia begins’, Figure 7) to inform readers of the first meeting planned by the commissioners after the massacre.Footnote 54 The Mafia violence, therefore, forced the government to take some responsibility. Secondly, the episode marked the resumption of repressive action taken by the state: in the following months, there were numerous police operations carried out between Palermo and its province, followed by the approval in parliament of the first antimafia law focused on internal exile (1965). L'Ora tried to accurately tell the story of the Mafia war, publishing photographs of the main bosses and the organizational charts of the families (Figure 8). It also, thirdly, concentrated on investigative actions, which led to the ‘processone’ (Maxi-trial) celebrated in 1968 in Catanzaro, rather than in Palermo, per legittima suspicione.Footnote 55

Figure 7. The edition of L'Ora announcing the first meeting of the Parliamentary Commission of Inquest, 2 July 1963.

Figure 8. The two Mafia factions at war, L'Ora, 11 September 1963.

The outcome of the trial was unsatisfactory: harsh penalties were only given to Angelo La Barbera (22 years’ imprisonment) and a few others. Many others were acquitted. Moreover, the concomitant legal proceedings in Bari against the Corleonese faction also had limited success, with the acquittal of most of the defendants. However, in the beginning, these repressive actions had a great impact on Mafia families: many affiliates fled to America (Salvatore Greco to Venezuela, Tommaso Buscetta to Mexico), many others were arrested. The Palermo Mafia Commission was dissolved and only reconstituted in 1970, after the conclusion of the Catanzaro trial, in the form of a triumvirate led by Gaetano Badalamenti from Cinisi, Luciano Liggio from Corleone and Stefano Bontade from Palermo. The effect of this first wave of state interventionism, therefore, was also to upset the Mafia's balance: defeated in the conflict against the Grecos, the La Barberas faction was definitively dissolved by the triumvirate at the beginning of the 1970s.

Among the many documents published in these years by the newspaper in support of the parliamentary commission, one in particular is noteworthy: the report regarding 24 mafiosi from Palermo drawn up in March 1963 by the Carabinieri lieutenant Mario Malausa, who died two months later in the Ciaculli massacre (Figure 9). L'Ora first made reference to this source on 24 October 1963, suggesting that the massacre might have been avoided if the report had been in the public eye: now its publication in full caused a stir in public opinion and among the police forces themselves.Footnote 56 The importance of the report led many to wonder whether Ciaculli's car bomb had been intended to target the Carabinieri rather than the Grecos: none of the subsequent investigations, however, confirmed this hypothesis. Certainly, something in the security apparatus did not work, especially at an inter-force co-ordination level, as the Palermo police commissioner, Rosario Melfi, declared to the Commission of Inquest that he had learned of the memo through the newspaper L'Ora. Although the memo was explicitly directed to the commander of the Palermo Internal Carabinieri Group and contained news of the highest importance, no one had thought to share it with the ‘upper echelons’ of the police.Footnote 57 Moreover, the report indicated that one of the 24 bosses, Pietro Buffa from Ciaculli, was the owner of the garage of the Palermo police department.

Figure 9. The Malausa Report, L'Ora, 14 January 1964.

In fact, many aspects of the document were crucial, as they showed the extraordinary longevity of the families of Palermo. The mobsters described in it came from the city or from a nearby province, and had been brought to trial during the Fascist era but acquitted or occasionally given light sentences. At the beginning of the 1960s, they appeared at the head of the same gangs as if nothing had changed: they were tenants and landowners, traffickers, brokers, mediators and traders. None of them came from the latifundium or from the inland area of Sicily, considered as the centre of the ‘Mafia infection’:

Born in Palermo on 21 October 1905 – wrote Malausa about Francesco Targia – …He was a fervent supporter of separatism, but when that movement began to lose power, he followed in the wake of other mafiosi, hopping from one party to another (liberal-monarchic-Christian Democrat). The distaste that he felt for legality clearly demonstrates that it was not a political belief that pushed him toward the DC, but only personal self-interest.Footnote 58

Giuseppe Motisi, a cattle merchant and farmer, would also have been oriented towards the DC, but not because it was ‘his political idea, but in order to support his brother Baldassarre, who [was] a well-known member of that party’.Footnote 59 As such, Baldassarre had been elected to the municipal council on the DC ticket. Nevertheless, the group that best reflected the historical depth and the dynastic character of some of the Palermo gangs was the Greco family, who were divided into two sections located in the borgate of Ciaculli and Croceverde-Giardini. Malausa reported a Francesco Greco born in Palermo on 13 February 1887, connected by ‘adherence and friendships with the Sicilian Region, the Prefecture, the Police Headquarters and many other state bodies’, considered a man who garnered respect and who was endowed with influence over the borgate of Pomara and Acqua dei Corsari. Among the 24 bosses, there was also Francesco Paolo Bontate, known as Don Paolino:

Notoriously affiliated to the Palermo Mafia. In the guise of a merchant and landowner, he helped the Mafia to gain dominance in the food sector throughout the city. He posed as a man of honour and declared himself so. Apparently calm and respectful, but, in fact, he is violent because of his innate instinct for overpowering, imposing his will on others.Footnote 60

The ‘Malausa Report’ described the urban Mafia as an extremely dangerous actor, embedded in the same places for generations, connected in various ways to political circles, public offices and the most diverse sectors of the economy. It highlighted the interconnectedness between the gangs by family, business and comparaggio (artificially created family ties) relationships. Outlining the dense Mafia–political–business network of Palermo, the document gave a very different image of the phenomenon to that created at the time by Michele Pantaleone's best-seller Mafia e politica, and sometimes revamped by the newspaper itself, based on latifundium and on the patriarchs à la Calò Vizzini and Giuseppe Genco Russo. The investigative findings, in other words, highlighted the central role of the urban context, so often underestimated: that the ‘real’ Mafia, its organizational core, did not in fact garrison Villalba, Mussomeli or other localities in the inland countryside, but the ‘Capital’ of the island: Palermo.

Conclusion

The term ‘antimafia’ as an idea that supports law enforcement – that is, the current meaning of the word – originally came from the relationship between public opinion, the parliamentary commission and investigative departments. In this context, L'Ora played a special role, helping to balance the sphere of repression with that of public debate, marking a discontinuity in the history of the fight against the Mafia. The peasant antagonism, which dated back to the popular struggles of the post-war period, was replaced by a different kind of opposition. The post-war mobilizations had subordinated the antimafia struggle, focusing instead on the wider intertwining of social (land aristocracy, Mafia groups) and institutional (police, Carabinieri, judiciary) powers: in other words, no peasant leader would have collaborated with the police or the judicial authorities against the Mafia, because this would have been equivalent to interfacing with the enemy. In order to explain the lack of co-operation with the authorities, it is of course necessary to consider the fear the Mafia instilled in the population. Nevertheless, the constitution of the parliamentary commission in 1963 and the new active role taken up by state institutions meant that some state actors were granted credit that had been decisively denied to them in the previous phase.

A memory of Vincenzo Vasile, L'Ora journalist in 1971–72 and the last director before its closure in 1992, effectively expresses this change. At the beginning of the 1960s, he was a member of a cultural centre close to the newspaper, chaired by the sociologist and activist Danilo Dolci and strongly supported by Nisticò. During the first debate with Leonardo Sciascia, held at the Foro Italico on 15 April 1965, Vasile expressed his disappointment about Sciascia's celebrated novel Il giorno della civetta to the writer:

I know – wrote the journalist – I followed a rigid ideological scheme, but in the name of the mass struggle against the Mafia, I contested that Sciascia had given the role of protagonist and fighter to an exponent of the state apparatus, an officer from the North, the Captain Bellodi, with all the skeletons in the wardrobe of the state from the Portella [della Ginestra] massacre onwards, here in Sicily. More interestingly, and it still resonates in my head, was the answer of Sciascia. Who was certainly intrigued by my disrespectful condemnation: he kindly invited me to look with trust (I think he said: critical trust) at the possibility that within the apparatus, the Carabinieri, the Police, the Magistracy a group of people of tenacious concept [‘persone di tenace concetto’, strong-willed people] could grow, able to turn the page on the negotiations between pieces of the state and the Mafia, in the days of the bandit Giuliano, as in our times.Footnote 61

The pursuit of connections between different aspects of society (public opinion, central and peripheral institutions, political forces) gave the initiative of L'Ora an innovative character and national resonance. Above all, this circularity took place at a cognitive level: the exchange of information between the newspaper, the Commission and law enforcement agencies fed a virtuous mechanism of awareness raising.Footnote 62 In other words: L'Ora caused knowledge about the Mafia, which until then had been confined to police reports, to become public knowledge, feeding an extremely valuable stream of counter-information. The newspaper's success was also translated into sales, which rose from 12,000 to 16,000 in 1954, and to 30,000 in 1966.Footnote 63 The consequent repressive phase, the immediate effect of this process, was ineffective, as a result of the inauspicious outcome of the Bari and Catanzaro trials (1968–69). In the following years, the fight against the Mafia remained the prerogative of a few sections of Sicilian and national society (journalists, politicians, police investigators and prosecutors), until the enemy offensive forced the institutions to respond more incisively. L'Ora counted on a body of left-wing opinion that always remained in the minority. Certainly, the newspaper's action favoured the emergence of a new antimafia awareness, preparing the ground for later battles. As Bianca Stancanelli, a L'Ora journalist between 1978 and 1987, noted:

I think that everything that happened in Palermo that was good, positive, even in those terrible years [the reference is to the Mafia offensive against the state and civil society in 1979–93] owes a great deal to the existence of L'Ora, in the sense…that without L'Ora in Palermo there would not even have been Falcone, Chinnici, the Antimafia Pool.Footnote 64

The role of L'Ora can only be explained in light of the political and cultural competition for the urban space of Palermo. Its investigations, which can be defined as the most realistic post-Fascist representation of the Mafia phenomenon, aimed to disrupt the power relations between the Mafia, politics and business, in an attempt to protect a city that was being gutted from within. Its information, confirmed decades afterward by mass trials, relied on the journalists’ knowledge of the territory and their political and civil commitment. Observing them nowadays represents a cognitive challenge, since we are influenced by ‘history’ reconstructed by the huge trials, and particularly by the ‘Maxi-processo’ (Maxi-trial).Footnote 65 Today everyone ‘knows’ what the Mafia is and always has been, while L'Ora acted in a context in which a large part of Sicilian society continued to deny its existence.

If the Mafia networks actively contributed to the social production of urban space, L'Ora provided a defence against the logic of building speculation, against bad politics, bad business and criminal powers. This contrasts inexorably with the exclusively negative reconstructions of the history of Palermo, Sicily and southern Italy that have long dominated cultured discussion.Footnote 66 The newspaper's experience constituted an engine of institutional awakening against the destruction of urban space, advocating the renegotiation of political and administrative relations between centre and periphery. However, this represents a cognitive challenge for scholars who aim to investigate forms of conflict concerning the physical construction of the city and how these affect its transformation. Such conflicts derive from the ability of certain forms of organized crime to interact with the administrative authorities of the territories and therefore to have a powerful impact on the historical urban development of cities. It would be interesting, however, to broaden the analytical field, better defining the capacity of local politics to influence central policies and therefore to compete for the distribution of resources and their use in urban planning. The case of Palermo represents an unavoidable point of comparison.