Recruitment of doctors into psychiatry has been a concern for decades. Reference Goldacre, Turner, Fazel and Lambert1 In more recent years the issue of recruitment has again become topical as psychiatry has consistently failed to fill all its training posts nationally. In 2011 and 2012, only 83% and 85.3% of core training year 1 (CT1) posts respectively were filled following the second rounds of recruitment. 2,3 This raises many issues including concerns about future workforce planning and also that a need to fill training posts for service provision purposes may lead to recruitment of a lower calibre of trainees with longer-term consequences for the specialty. Reference Pidd4 The Royal College of Psychiatrists has therefore implemented a national 5-year recruitment campaign, 2 with its primary aim to increase recruitment to the CT1 grade of core psychiatry training, achieving a 50% increase in applications and a 95% fill rate by the end of the campaign. The College recruitment strategy outlines a variety of ways in which it is hoped that this will be achieved. One of these includes the creation of summer schools in each regional division, in the hope that this may ‘seed the idea of psychiatry as a career’. 2

In the UK, psychiatry summer schools are a relatively recent phenomenon. They were introduced by the Royal College of Psychiatrists and the Institute of Psychiatry in 2009 when the first event was held in London. Since then this event has run annually, and the concept has been replicated with summer schools emerging in other centres in the UK. Despite much time, energy and effort being invested in such endeavours, there has been very little published on the outcomes of these events; including what makes a successful event and the impact it has on the medical students who attend. A recent article published in The Psychiatrist helpfully outlines guidance on how to create a summer school based on the authors’ experience but recognises there is a need for evaluation of such events. Reference Greening, Tarn and Purkis5

Concerns about recruitment of medical students into psychiatry are not unique to the UK. Similar concerns have been noted in the USA and Canada. Such issues led to the development of a summer school in Toronto that was replicated in other regions in Canada. Reference Andermann, De Souza and Lofchy6 This Canadian enterprise began in 1994 and data from its evaluation suggest a positive influence on career intentions, although less than half the students attending were ultimately matched into psychiatric residency programmes. Interestingly the success rate was higher when only students who attended the parent event were considered. Confounding factors such as difference in summer school programmes and the impact of other recruitment strategies may have contributed to this effect.

In creating a summer school it is important to consider the issues that may influence medical students’ attitudes towards psychiatry. There have been many articles published exploring the reasons why medical students and junior doctors are deterred from pursuing psychiatry as a career. Factors identified include a perceived lack of scientific basis for psychiatric practice, that psychiatry is removed from ‘real medicine’, the perception that patients do not improve or get better, students’ concerns about overidentifying with patients and the perceived low status of psychiatry within the profession. Reference Goldacre, Turner, Fazel and Lambert1,Reference Goldacre, Fazel, Smith and Lambert7-Reference Lambert, Turner, Fazel and Goldacre14 We were also aware from observations and local unpublished work that even following medical school psychiatric placements students are often not aware of the multiple career strands within psychiatry. They also sometimes struggle to appreciate the role of the psychiatrist within patient journeys, and so cannot identify with the reality of what a career as a psychiatrist may entail.

Summer school programme

Tees, Esk and Wear Valleys NHS Foundation Trust ran their first summer school in July 2012 designed by the authors of this article. When devising the programme the team spent time seeking clarity of the purpose of the summer school, which was encompassed in our aims and objectives. The vision was to create an event that did not replicate medical school experience but that aimed to specifically target factors known to negatively influence students and buffer against these, in addition to also nurturing interested students by including items that are felt to attract students towards psychiatry. We aimed to positively influence students’ attitudes and communicate psychiatry as a stimulating and challenging yet rewarding specialty that requires compassionate and skilled doctors who have an important role in assessing and managing patients. The target audience were medical students with an interest in psychiatry, but who had not decided on their career trajectory. Although clinical experience is vital in positively influencing medical student attitudes, it was felt that within a 3-day event we were unlikely to be able to incorporate any meaningful patient content without compromising other aspects of the programme. We aimed to evaluate this event through measuring its impact on students’ career intentions and attitudes towards psychiatry.

Each item within the programme (see online Appendix DS1) was included for the value it could add in communicating a positive message about careers in psychiatry. We were particularly careful to ensure that we highlighted the role of the doctor, the positive challenge involved in assessing and managing cases of complexity and diagnostic uncertainty, the privilege and importance of the doctor-patient experience and a sense of therapeutic optimism through recovery. We selectively involved clinicians who could contribute not only their expertise but who also communicated enthusiasm and professionalism, bearing in mind that the recruitment literature highlights the importance of positive role modelling. Reference Pidd4,Reference Wear and Skillicorn15 We also focused on allowing the students opportunities to build relationships with the clinicians involved in the event. Aware that our programme did not involve actual patient contact, there was a focus on bringing clinical material to life without the need to attend the clinical environment.

Method

All summer school delegates (n = 19) were asked to complete a questionnaire at the beginning and end of the event. The questionnaire included basic demographics, questions about career intentions, the 30-item Attitudes Toward Psychiatry (ATP-30) Reference Burra, Kalin, Leichner, Waldron, Handsforth and Jarrett16 scale and qualitative free-text feedback on every session in the programme.

The ATP-30 is an attitudinal survey designed to look at medical students’ attitudes towards psychiatry. It was created in 1982 by Burra et al, Reference Burra, Kalin, Leichner, Waldron, Handsforth and Jarrett16 and has not been updated since this time but has been used in numerous studies. The scale was shown to be sensitive in detecting positive shifts in attitude after students had clinical psychiatric placements. In the original paper the third- and fourth-year medical students’ baseline ATP-30 score was a mean of 104.2, with an increase after clinical exposure to 108.5. Since then the scale has been used internationally to assess the impact of teaching, clinical attachments and promotional strategies. Reference Kuhnigk, Hormann, Bothern, Haufs, Bullinger and Harendza17-Reference Agbayewa and Leuchner19 On completing the questionnaire participants are asked to respond to 30 statements using a 5-point likert scale (strongly agree to strongly disagree). Statements are equally positively or negatively phrased. For each respondent a total attitudinal score is calculated. The ATP-30 does not have proven validity for specific items within the scale, but previous research has looked in more detail at the scores and changes of scores on various items to highlight perhaps more subtle influences. Reference Thompson, Dogra and McKinley20 We have therefore also looked at this within our analysis.

We administered the questionnaire using Turning-Point (version 4.2.4.1012 Capacity 5, which is an interactive audience participation software programme that is integrated within Powerpoint 2007, using Windows XP Professional. Students were allocated a number to track changes in their attitudes while maintaining anonymity. Embedding the questionnaire within the opening and closing sessions of the event ensured a 100% response rate. We then planned to compare the mean ATP-30 scores using a paired t-test.

Results

Participants

The summer school was attended by 19 students from various medical schools across the country (Table 1). They ranged in age from 19 to 35 and the majority (74%, n = 14) were female. All attended UK medical schools and the majority (89%, n = 17) spoke English as their first language.

Attitudes towards psychiatry

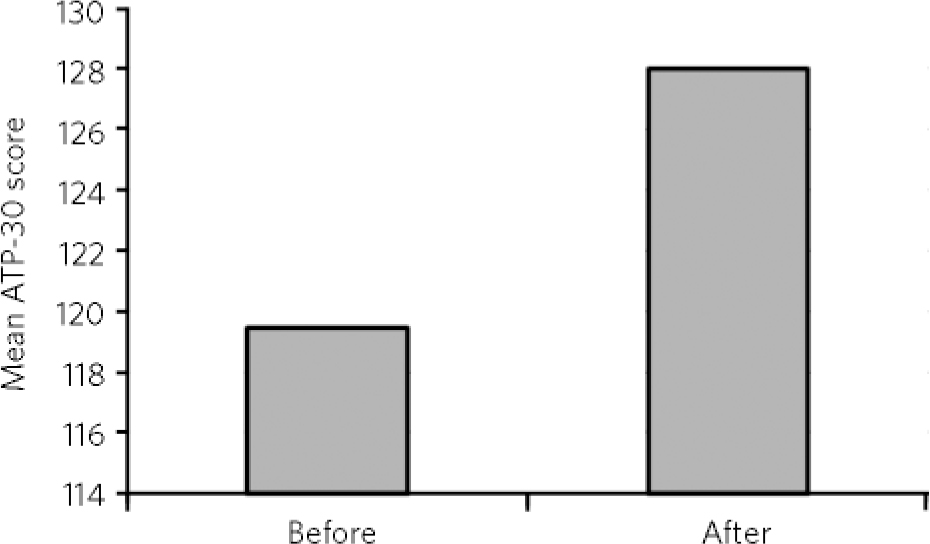

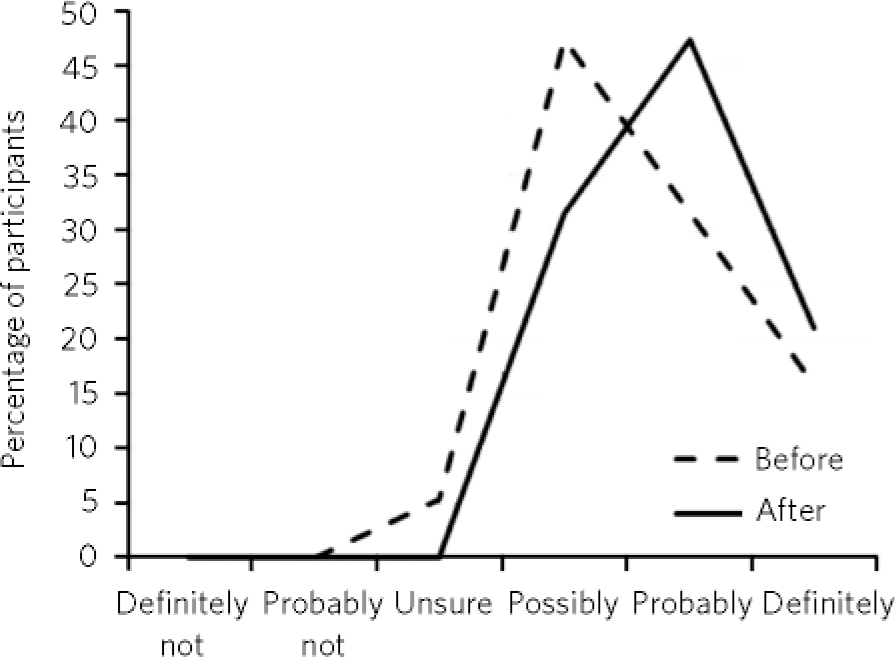

The ATP-30 scores showed that our summer school students already had relatively high baseline scores demonstrating positive attitudes towards psychiatry. The mean ATP-30 score before the summer school was 119 (s.d. = 9.8). Despite these positive initial attitudes, the students were not certain of their career intentions, with only 47% definitely or probably indicating their intent to pursue psychiatry as a career prior to the summer school. There was a notable increase in mean ATP-30 score after the summer school, by 9 points, to a total of 128 (s.d. = 10.6, Fig. 1).

As the results were normally distributed we used a paired t-test to compare the ATP-30 mean difference scores before (119) and after (128) the event. Despite the high baseline scores we demonstrated a highly statistically significant positive increase in attitudes towards psychiatry (t = 5.40, d.f. = 18, P<0.001) following the event.

Table 1 Demographic data

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 5 (26) |

| Female | 14 (74) |

| Medical school year | |

| First | 4 (21) |

| Second | 10 (53) |

| Third | 5 (26) |

| Age, years | |

| ⩽20 | 6 (31) |

| 21-25 | 10 (53) |

| 26-30 | 2 (11) |

| 31-35 | 1 (5) |

| ⩾36 | 0 (0) |

| First language | |

| English | 17 (89) |

| Other | 2 (11) |

| Country of birth | |

| UK | 15 (79) |

| Ireland | 1 (5) |

| Other | 3 (16) |

We also demonstrated a positive shift in career intention with an increase to 68% (n = 13) definitely or probably wanting to pursue psychiatry as a career. At the end of the event none of the students had rejected psychiatry nor did any remain unsure whether to consider it as a potential career (Fig. 2).

Details of response

We looked closely at areas within the ATP-30 to analyse potential specific influences of our programme. We note that the ATP-30, as mentioned previously, does not have proven validity for specific items, but we feel this was an important way to break down our results further, and this has been done previously within the literature. It is important to note that none of the 30 attitudinal statements showed a decrease in score from baseline. They all either remained at the same level or shifted, becoming more positive towards psychiatry.

Fig 1 Mean Attitudes Toward Psychiatry (ATP-30) scores at the beginning and end of the summer school.

Items with the lowest baseline scores

-

(a) These days psychiatry is the most important part of the curriculum in medical schools.

-

(b) The majority of students report that their psychiatric undergraduate training has been very valuable.

-

(c) Psychiatry is a respected branch of medicine.

This appears to show that although most students at our summer school were in their preclinical years, they were still unsure about psychiatry’s place in medical school and the medical arena as a whole.

Items with the highest baseline scores

-

(a) Psychiatric illness deserves at least as much attention as physical illness.

-

(b) It is interesting to try and unravel the causes of a psychiatric illness.

-

(c) The practice of psychiatry allows the development of really rewarding relationships with people.

Before the summer school, as expected, those areas scoring highest revealed an inherent interest in some of the factors that make psychiatry unique.

Items with the largest increase in score

-

(a) It is quite easy for me to accept the efficacy of psychiatry.

-

(b) Psychiatry is a respected branch of medicine.

-

(c) Psychiatry has very little scientific information to go on.

-

(d) Psychiatrists tend to be at least as stable as the average doctor.

-

(e) Psychiatric patients are often more interesting to work with than other patients.

Results suggest that our programme seemed to have a particular influence on the perception of the specialty’s standing in medicine and as a scientific discipline.

Fig 2 Participants’ answers regarding choosing psychiatry as a career at the beginning and end of summer school.

Items with no change in score

-

(a) People taking up psychiatry are running away from real medicine.

-

(b) It is interesting to try and unravel the causes of a psychiatric illness.

-

(c) The practice of psychiatry allows the development of really rewarding relationships with people.

-

(d) Psychiatrists talk a lot but do very little.

-

(e) The practice of psychotherapy basically is fraudulent since there is no strong evidence that it is effective.

The majority of areas that the summer school did not influence already had high scores at baseline, although results suggest that there was a potential weakness in our programme in looking at addressing perceptions regarding psychotherapy.

Discussion

These results suggest that a non-clinical summer school positively portraying psychiatry can have a significant impact on medical students’ attitudes towards the specialty. The mean baseline ATP-30 score of 119 (s.d. = 9.8) in our sample of students is higher than baseline scores seen in other medical student populations. For example the mean baseline ATP-30 for fourth-year medical students in one study was 102.6 (s.d. = 10.1) Reference McParland, Noble, Livingston and McManus13 and in another study sixth-form school pupils had a mean baseline of 110 (s.d. = 12.8). Reference Maidment, Livingston, Katona, Whitaker and Katona21 We were surprised that in spite of their initial high ATP-30 scores this short intervention still produced a significant positive shift in attitude and had an influence on students’ apparent career intentions.

We feel this is evidence that summer schools can be effective in influencing students’ opinions. Previous research has suggested that clinical encounters are pivotal in influencing students and changing career intentions. Reference Manassis, Katz, Lofchy and Wiesenthal10 However, our carefully designed programme suggests that patient contact in this type of event is not essential. We believe this is because the programme compensated by focusing on bringing to life patient experiences through cases, highlighting recovery, emphasising an empathic approach and having workshops that included case studies that embodied the role of the psychiatrist in patient journeys. Through not including face-to-face clinical time the programme was able to focus and target areas known to deflect students from psychiatry.

We also found attitudes were changed to a varying degree, and feel this shows that the emphasis of the summer school programme is important. There are already identified aspects, so called ‘push factors’, which make psychiatry less appealing and our baseline scores highlighted one of these especially, regarding psychiatry’s portrayal within the wider medical landscape. It is important to tailor programmes to have an impact on areas where we are aware there are frequently negative misconceptions among students, and that we know are important in discouraging them from pursuing psychiatry. We have shown that developing a carefully chosen programme of events to do just this has led to these areas being influenced substantially more. This was demonstrated through aspects of attitude such as respect for psychiatry, its scientific basis, efficacy of treatment and the interesting nature of work within psychiatry increasing more than others. We also have learnt that having less focus on psychotherapy and talking therapies in general has meant that we did not create opportunities to positively change students’ opinions, and therefore did not seem to influence this aspect on evaluation. It is important to note that although there were a few items on the ATP-30 where the score did not increase, there were no areas of the students’ attitudes that we appear to have had a negative impact on.

Implications

Further evaluation of the longitudinal impact of such interventions needs to be explored, in order to see whether such attitudinal changes are sustained. There is evidence in previous studies Reference Maidment, Livingston, Katona, McParland and Noble11 that attitudes are subject to erosion and alteration at specific points of undergraduate and postgraduate training. This is especially true when considering the stage of training of the delegates, none of whom were in the final years of medical training.

Consideration needs to be given to strategies where the positive experiences of summer schools can be reinforced throughout their medical training. This is an important early influence and contact point. It may be that summer school reunions, using social media to form networks or more formal mentor arrangements could sustain the positive influence over time. We feel summer schools are important and play a part alongside other positive undergraduate experiences of the specialty. We believe they can produce a cumulative effect on influencing students’ positive intentions to pursue psychiatry as a career and that summer schools have a legitimate part to play in the recruitment strategy.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.