Introduction

Over the lifetime of the BABCP, life expectancy in the UK has risen, the number of people over the age of 65 has grown, and the percentage of total population who are aged 65+ has increased. When the BABCP was founded in 1972, life expectancy in the UK was 72 years of age – not much more than the biblical ‘three score years and ten’. In contrast, the life expectancy for a 65-year-old in the UK today is 87 years for a female and 85 years for a male, albeit with considerable variation linked to socio-economic status (www.ons.gov.uk). There are more nonagenarians and centenarians than ever before, with the population aged 90+ years exceeding 600,000 (www.ons.gov.uk).

National policy in England is that older people’s mental health should be embedded as a ‘silver thread’ through all adult mental health, including the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme (NHS England, 2019a, 2019b). A decade ago, Green (Reference Green2011) reported only 3% of referrals to IAPT were for older people compared with a target of 12–15%. Initiatives to increase accessibility of services to older people were introduced, including: employment of National Advisors (Department of Health, 2012); publication of toolkits (Department of Health, 2013); production and promotion of positive practice guidance (Age UK and BABCP, 2021; Department of Health, 2009); and a National Curriculum (Chellingsworth et al., Reference Chellingsworth, Davies and Laidlaw2016). However, the proportion of older people seen in IAPT services has remained consistently and stubbornly below-target. Pre-pandemic, IAPT had yet to improve access to psychological therapies for older people (Clark, Reference Clark2018; NHS Digital, 2020), and the shift to digital during the pandemic is unlikely to have increased the proportion of older service users.

Although older people are under-represented in IAPT, it is often reported that those who do engage ‘do better’ than their younger counterparts; IAPT service users aged 65+ have better recovery rates and improvement rates than adults aged below 65 (NHS Digital, 2020). Various explanations for this finding had been posited: ‘those older people who engage with IAPT are the most capable and require little, if any, adaptation to standard CBT protocols’; ‘CBT therapists in IAPT are already able to work well with older people and do not require additional training or support’. In an attempt to move beyond the service level data available to NHS Digital, a patient-level analysis has recently been published on data from 100,179 service users from eight London IAPT services over 11 years (2008 to 2019; Saunders et al., Reference Saunders, Buckman, Stott, Leibowitz, Aguirre, John and Pilling2021). Older people were more likely than their younger counterparts to receive guided self-help at step 2, were less likely to be stepped up and more likely to receive non-CBT treatments at high intensity (Saunders et al., Reference Saunders, Buckman, Stott, Leibowitz, Aguirre, John and Pilling2021). High intensity (HI) CBT was the last treatment received for only 33% of people aged over 65 years compared with 44% of those aged 18 to 64. This represents a mean of only 14 older people per service per year compared with over 500 aged 18 to 64.

With CBT for anxiety and depression in older people ‘hanging by a thread’ in IAPT, the aim of this paper is to develop recommendations for future directions in training for, and supervision of, CBT for anxiety and depression in later life. This will be achieved through (i) revisiting learning from literature on ‘CBT in older people’ from the BABCP’s first 50 years; (ii) identifying lessons to be learned from case studies of CBT with older people published in the Cognitive Behaviour Therapist (tCBT); and (iii) to consider strategies for enhancing collaborative empiricism for young therapists working with older service users who present with physical and mental health co-morbidities.

CBT with ‘older people’: the evidence base

The first trial of ‘CBT with older people’ was published in 1982, in the USA (Gallagher and Thompson, Reference Gallagher and Thompson1982). In this three-arm study, Lewinsohn’s pleasant events scheduling was compared with Beck’s strategies for addressing cognitive distortions and to brief relational/insight psychotherapy. All three approaches led to reduction in symptoms of depression, but the gains were better maintained after the behavioural and cognitive interventions. Many participants in Gallagher and Thompson’s trial, however, would not be considered ‘old’ in today’s NHS. Whereas the term ‘older people’ commonly refers to those aged 65 and above (with the lower boundary rising to 70 or even 80 years of age to see NHS geriatricians in some geographical areas), the youngest participant in Gallagher and Thompson’s trial was merely 59 years of age. Participants were predominantly in the ‘young-old’ category (ages 65–74), or younger, with mean ages ranging from 66 (behavioural arm) to 69 (relational psychotherapy arm). The oldest participant was 80 years of age (‘middle-old’), with no-one from the ‘old-old’ (85–94 years) or ‘oldest old’ (95+) categories, perhaps due to age profiles at the time, to sampling strategies or to those with co-morbid diagnoses being excluded.

By 2012, 30 years after the foundation of ‘late-life’ CBT (and 40 years into the history of the BABCP), the evidence base for CBT with older people had grown, but failed to move beyond the ‘young-old’. For example, Becky Gould and colleagues were able to identify 23 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of CBT for depression (Gould et al., Reference Gould, Coulson and Howard2012a) and 12 RCTs of CBT for anxiety (Gould et al., Reference Gould, Coulson and Howard2012b). Meta-analyses of post-treatment outcomes indicated large and significant pooled effect sizes in favour of CBT for depression, and moderate (but significant) pooled effect size in favour of CBT for anxiety (Gould et al., Reference Gould, Coulson and Howard2012a,b). However, ‘older people’ were defined as anyone aged 50+ or 55+ in the depression and anxiety reviews, respectively. As with the Gallagher and Thompson study (1982), trial participants continued to represent the youngest end of ‘old’, with mean ages ranging from 55 to 74 years. Across the two reviews, only one trial (Serfaty et al., Reference Serfaty, Haworth, Blanchard, Buszewicz, Murad and King2009) set the minimum age criterion as 65 years.

In addition to reviews of ‘CBT’ (of varying definition), specific therapies falling under the ‘behavioural and cognitive psychotherapies umbrella’ have also shown effectiveness with depressed older people with co-morbid physical illness. For example, behavioural activation (BA) has a strong evidence base with older people both as a stand-alone treatment and as part of a multi-component intervention (Orgeta et al., Reference Orgeta, Brede and Livingston2017) as does problem-solving therapy for major depressive disorder (Shang et al., Reference Shang, Cao, You, Feng, Li and Jia2021).

Co-morbid physical, cognitive and mental health difficulties

An advantage of the cognitive behavioural approach is that both emotional and physical experiences can be considered. Physical and mental health difficulties commonly co-occur; there are psychological consequences of physical health problems, and physical health is often compromised in people with long-standing mental health problems. Over half (54%) of the population in England aged 65+ are living with two or more of: cancer, coronary heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, respiratory disorders, stroke, arthritis, dementia and depression. Only one in five people aged 65–74 years is condition-free, reducing to fewer than one in ten of those aged 85+ (Kingston et al., Reference Kingston, Robinson, Booth, Knapp and Jagger2018).

Given the high prevalence of physical health morbidity in later life, the evidence base for CBT for anxiety and/or depression in people who have physical health co-morbidities is relevant to CBT practitioners. The mean ages of participants in such trials are similar to, if not older than, ‘older adult’ trials. For example, although not explicitly seeking to study ‘CBT with older people’, the mean age of participants in Williams and colleagues’ (Reference Williams, Johnston and Paquet2020) review of CBT for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was 67 years. Similarly, meta-analyses of CBT for depression and anxiety in cardiovascular disease and Parkinson’s disease respectively included trials with mean ages range from 60 to 63 (Reavell et al., Reference Reavell, Hopkinson, Clarkesmith and Lane2018) and between 60 and 69 (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Yang, Song and Jin2020).

Physical, cognitive and mental health difficulties affect not only the individual but also their close family and friends. There is a significant literature on CBT for family caregivers, many of whom are older people themselves (Sun et al., Reference Sun, Ji, Leng and Wang2022), and also an evidence base for CBT for couples living with physical health conditions (Fischer et al., Reference Fischer, Baucom and Cohen2016).

Summarising the evidence base, ‘CBT with older people’ is effective in reducing depression and anxiety. Whereas early literature was limited by the young-old age of participants and the exclusion of people with co-morbidities, more recent studies have shown that CBT for anxiety and depression in people with physical health conditions is demonstrably effective, even when conditions are chronic, deteriorating and terminal, and, arguably more relevant to older populations, where physical morbidity is high. Translating review findings into practice is hampered by the heterogeneity of content and delivery format. For example, interventions in the CBT for depression meta-analysis by Gould and colleagues (Reference Gould, Coulson and Howard2012a) included group, individual and internet delivery, bibliotherapy and self-management. Studies variously include trial-specific protocols, trial-specific adaptations made to ‘standard’ CBT protocols, and intervention protocols tailored to individual-need as judged appropriate by the trial interventionist. None of the protocols adapted for, and tested with, older populations is yet part of the ‘standard offer’ in IAPT. Although evidence-based CBT protocols are not, and are unlikely ever to be, developed for every combination of physical and mental health co-morbidity, recent developments include CBT manuals that describe a modular approach (e.g. Charlesworth et al., Reference Charlesworth, Sadek, Schepers and Spector2015; Steffen et al., Reference Steffen, Thompson and Gallagher-Thompson2021), thus allowing practitioners to design interventions to meet individual need.

tCBT ‘older people’ case examples

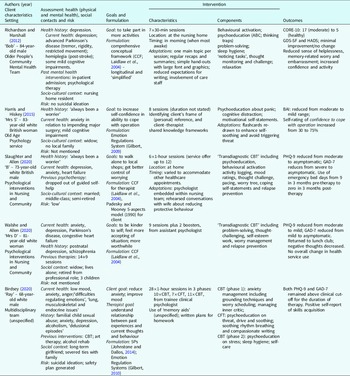

Presentational heterogeneity combined with an absence of evidence-based protocols means that CBT with older people is often idiosyncratic. Whether adapting the ‘best available’ protocol, or devising a unique client-specific approach, clinicians are likely to be using an individual formulation to direct their approach. This may explain why single case studies with older people have an ongoing presence in CBT literature. Five single case studies have been published in tCBT between journal inception (2008) and 1 March 2022 (volume 15). All five case studies were formulation-driven and with clients with mixed anxiety and depression with co-morbid physical health conditions. The setting, client characteristics, goals, formulation approach, intervention characteristics and components and outcomes for the five case studies are provided in Table 1 and synthesised below.

Table 1. Summary of tCBT case studies involving older people

Clients and settings

Three of the studies were with octogenarians (Harris and Hiskey, Reference Harris and Hiskey2015; Richardson and Marshall, Reference Richardson and Marshall2012; Walshe and Allen, Reference Walshe and Allen2020), one with a septuagenarian (Slaughter and Allen Reference Slaughter and Allen2020) plus one person in their late 60s (Birdsey, Reference Birdsey2020). Three of the clients were male, and two female. Four were white British, with ethnicity not specified for one case study. Two cases came from the same service, the ‘Psychological Interventions in Nursing and Community’ service in Berkshire which provides psychological support to patients with long-term health conditions. Two were seen within multidisciplinary mental health teams, at least one of which was specifically for older people, and one was seen in a (secondary care) old age psychology service. None of the cases was seen in IAPT services.

Assessment and goals

The cases are typical of old age presentations in that mixed anxiety and depression are more common in later life than single diagnoses of either depression or anxiety. All five case descriptions included information on current and past physical and mental health, including current neurocognitive status, and current social/family circumstances. A similar approach is described by Pasterfield and colleagues (Reference Pasterfield, Bailey, Hems, McMillan, Richards and Gilbody2014) who, in adapting a behavioural activation manual for people with late-life depression, introduced additional assessment questions on: health conditions and their impact; past active thoughts, plans and preparation regarding suicide, including passive ideation; and social contacts including family. CBT assessment strategies included thought records and activity monitoring. Walshe and Allen (Reference Walshe and Allen2020) used the downward arrow approach to identify underlying self-beliefs. Common presentations included: sadness linked to illness-related losses; anxiety related to healthcare needs and procedures; frustration associated with physical limitation and appraisals of ‘self as worthless/useless’, and embarrassment at the need for help from others. Goals were ‘adjustment’ or ‘management’ focused, for example increasing activities, self-compassion, self-confidence, and sense of self-worth; getting better at worry management.

All five studies included psychometric assessments of anxiety and/or depression. The most common tools were the PHQ-9 (Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Lowe2006) and GAD-7 (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001) with other measures including the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck et al., Reference Beck, Epstein, Brown and Steer1988), the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; Zigmond and Snaith, Reference Zigmond and Snaith1983) and the Clinical Outcomes Routine Evaluation Scale (CORE-10; Connell, Reference Connell2007). The only old age-specific scale used was the short form of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS; Sheikh and Yesavage, Reference Sheikh, Yesavage and Brink1986).

Formulation

The most common formulation template was Laidlaw’s comprehensive conceptual framework (CCF; Laidlaw et al., Reference Laidlaw, Thompson and Gallagher-Thompson2004), used in three of the five cases. Other formulation approaches included the 5Ps (Johnstone and Dallos, Reference Johnstone and Dallos2014), the Emotion Regulations system (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2009, Reference Gilbert2010) and Padesky and Mooney’s five aspects (‘hot cross bun’) model (Reference Padesky and Mooney1990).

The CCF was first published in 2003 when Ken Laidlaw co-authored, with Larry Thompson, Dolores Gallagher-Thompson and Leah Dick-Siskin, the first book on CBT with older people (Laidlaw et al., Reference Laidlaw, Thompson, Gallagher-Thompson and Dick-Siskin2003). Building on previous approaches to psychotherapy with people in later life, the authors considered CBT within the context of gerontology (the scientific study of old age and the process of ageing). They placed the Beckian longitudinal model for emotional disorders within five areas of context of particular relevance to later life, namely: cohort (shared beliefs and experience of an age-specific generation), role investments (importance and function of roles carried on or lost over time), intergenerational linkages (stresses and supports of important close relationships across generations and connecting people with the society and cultures in which they live); sociocultural beliefs (internalisation or rejection of beliefs about ageing in the culture and society in which older people live); and physical health (health function assessed in terms of independence and opportunities for autonomy) (Laidlaw et al., Reference Laidlaw, Thompson, Gallagher-Thompson and Dick-Siskin2003; chapter 3). The following year, the CCF (Laidlaw et al., Reference Laidlaw, Thompson and Gallagher-Thompson2004) was published in the Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy special issue on CBT in later life (2004, volume 32, issue 4). It has since been cited over 100 times, making it the joint-top cited paper from the special issueFootnote 1 , equal with Smith’s review on clinical uses of mindfulness training (Smith, Reference Smith2004).

Using the CCF for their case study of ‘Bob’, an 84-year-old male nursing home resident with Parkinson’s disease and depression, Richardson and Marshall (Reference Richardson and Marshall2012) noted the relevance of cohort beliefs (‘Men should be strong, independent breadwinners’) in understanding avoidance behaviours (e.g. not asking staff for help to join in activities or to attend to care needs) and negative automatic thoughts such as ‘I’m a burden to my family’. It is of note, however, that none of the case studies reported sharing the CCF with the client, instead opting for ‘simplified’ versions. For example, for Bob, a mini-formulation was shared, illustrating the way in which his cognition ‘it’s too difficult’ led to him feeling down and avoiding activities, thus reinforcing rather than disconfirming the belief. Discussing the (mini-)formulation allowed Bob space to generate the alternative thought ‘It’s worth a go – I’ve done it before’. Charlesworth and Reichelt (Reference Charlesworth and Reichelt2004) echoed Gillian Butler’s call for parsimony in formulation (Butler, Reference Butler, Bellack and Hersen1998) by suggesting the use of ‘mini-formulations’ to encapsulate both a problem summary and action-plan rationale. The ‘mini-formulation approach’ has been used in the cognitive therapy treatment manual for use with people with co-morbid anxiety and mild to moderate dementia (Charlesworth et al., Reference Charlesworth, Sadek, Schepers and Spector2015) as trialled by Spector and colleagues (Reference Spector, Charlesworth, King, Lattimer, Sadek, Marston and Orrell2015). Similarly, ‘here and now’ maintaining cycles are encouraged in low-intensity approaches to CBT.

Intervention

(i) Duration and location

The number of sessions of CBT delivered ranged from 7×30 minutes (Richardson and Marshall, 2020) through to 28×1 hour (Birdsey, Reference Birdsey2020). Most were delivered in the client’s own home with timings arranged flexibly to meet client need (e.g. weekly variation to accommodate other healthcare appointments; morning appointments when most awake). Including home visits as part of the IAPT service offer has been included in the latest Positive Practice guidance for IAPT (Age UK and BABCP, 2021).

(ii) Components

Intervention components typically included psychoeducation, behavioural activation, thought-challenging (in particular ‘challenging the inner critic’), problem solving, and relaxation (e.g. deep breathing and guided imagery). Worry management, sleep hygiene, motivational self-statements and relapse prevention were also used in more than one case. Two of the case studies labelled their approach ‘transdiagnostic CBT’ (Slaughter and Allen, Reference Slaughter and Allen2020; Walshe and Allen, Reference Walshe and Allen2020) and two combined CBT with compassion-focused therapy (Birdsey, Reference Birdsey2020; Harris and Hiskey, Reference Harris and Hiskey2015). All included between-session tasks. None of the cases referenced ‘age-augmented’ strategies such as use of selective-optimisation with compensation (SOC) and wisdom enhancement (Laidlaw et al., Reference Laidlaw, Kishita and Chellingsworth2016).

(iii) Adaptations

Adaptations varied depending on the degree of physical and cognitive impairment in the client (see also two-dimensional model of adaptation; James, Reference James2010) but, where mentioned, included: short sessions, having only one main topic per session, use of ‘memory aids’ (unspecified), simple personalised hand-outs with large font and graphics and reduced expectations for writing (e.g. using ‘noticing tasks’ rather than written homework). The authors cited a range of works providing suggestions for adapting CBT for older adults (Chand and Grossberg, Reference Chand and Grossberg2013; Cox and D’Oyley, Reference Cox and D’Oyley2011; Evans, Reference Evans2007; Satre et al., Reference Satre, Knight and David2006; Secker et al., Reference Secker, Kazantzis and Pachana2004) and Richardson and Marshall list the user-friendly terminology that they employed in place of CBT jargon, for example ‘thinking traps’, ‘sad glasses’, ‘rubbishing our successes’ in place of ‘cognitive biases’, ‘selective abstraction’ and ‘discounting the positive’. Harris and Hiskey (Reference Harris and Hiskey2015) describe the importance of adapting materials to ensure that the language and presentation meets needs for self-soothing rather than triggering threat.

In contrast to case illustrations from Gallagher-Thompson and Thompson (Reference Gallagher-Thompson, Thompson and Pachana2010), none of the tCBT studies involved family members. For client ‘B’ (Slaughter and Allen, Reference Slaughter and Allen2020), opportunities were provided to rehearse with the psychologist conversations that he wanted to have with his wife around reducing the protective behaviours she had put in place since the onset of his heart problems. Further adaptations involving others included briefing care home staff on how to reinforce alternative thoughts (Richardson and Marshall, Reference Richardson and Marshall2012) and checking appropriateness of planned activities with members of the physical health team.

Outcomes

Depression and/or anxiety symptoms reduced from moderate to mild or asymptomatic on psychometric scales for all cases except for ‘Ray’ who scored above clinical cut-off for the duration of therapy (Birdsey, Reference Birdsey2020). There were self-rated reductions in helplessness, memory-related worry and embarrassment (Richardson and Marshall, Reference Richardson and Marshall2012), increased confidence and/or activity (Harris and Hiskey, Reference Harris and Hiskey2015; Richardson and Marshall, Reference Richardson and Marshall2012), increased social contact (Walshe and Allen, Reference Walshe and Allen2020) and reduction in emergency bed days (Slaughter and Allen, Reference Slaughter and Allen2020). It is interesting to speculate why Ray, the youngest of the case studies, receiving over three times as many sessions as any of the other case studies, showed the least symptom reduction. The explanation may lie in: his personal history (he experienced childhood sexual abuse); coping strategies (alcoholism, severing ties with family); or current risk (active suicidal ideation). It is also of note that his period of ‘wellness’ as an early adult was not used to inform his therapy (although recommended in work with older people), and the psychological consequences of his current physical health problems (lung, musculoskeletal and endocrine issues) were not considered. It is reported that he ‘had difficulty regulating emotions’ which is reminiscent of older adults with personality disorders and the work of Videler and colleagues who hypothesise that a focus on early adaptive schema may be a more fruitful approach than targeting maladaptive schema (Videler et al., Reference Videler, van Royen, Legra and Ouwens2020; Videler et al., Reference Videler, Van Beest, Ouwens, Rossi, Van Royen and Van Alphen2021).

Commentary

The content of the five tCBT case studies aligns well with the national curriculum for CBT in the context of long-term persistent and distressing health conditions which recommends: adapting CBT for clients with anxiety and depression presenting in the context of long-term health conditions; including a partner or other significant members of the client’s system in assessment and treatment; working with medically unexplained or persistent and distressing physical symptoms including chronic pain, diabetes, COPD, coronary heart disease and cancer; working across organisations; and applying CBT flexibly, including home visits (NHS England and HEE, 2017) .

Collaborative empiricism, in which the therapist and client together test out a client’s thoughts and assumptions with the mutually agreed goal of improving client wellbeing, is a central tenet of Beckian CBT and a key competency for CBT. Yet, surprisingly, collaboration is only mentioned in two of the five tCBT older adult case studies. The term ‘collaboration’ is used once in the Slaughter and Allen (Reference Slaughter and Allen2020) case study, but only when describing background literature. It is left to Birdsey (Reference Birdsey2020) working with Ray – the youngest case – to use the terms collaborative discussion, collaborative review and collaborative decision-making.

Intergenerational collaboration

In a recent special feature in commemoration of Beck’s contributions to the science and practice of CBT, Christine Padesky reflects both on the novelty of collaborative empiricism in the 1960s–70s and the way in which it sustained Beck’s work over 60 years (Padesky, Reference Padesky2022). On the basis of the tCBT case studies, one might wonder whether an adaptation for CBT with ‘old-old’ people might be to step back from attempts at collaboration and to move instead to a more directive approach, especially where the service user takes a passive rather than active stance. However, as Dick et al. (Reference Dick, Gallagher-Thompson, Thompson and Woods1996) wrote in the Handbook of Clinical Psychology of Ageing, ‘[We] cannot stress enough how the success of c/b [cognitive behavioural] therapy hinges on the collaborative therapeutic relationship’ (p. 522). Collaborative empiricism receives multiple mentions in both Ian A. James’ and Ken Laidlaw’s books on CBT with older people (James, Reference James2010; Laidlaw et al., Reference Laidlaw, Thompson, Gallagher-Thompson and Dick-Siskin2003; Laidlaw, Reference Laidlaw2014) and collaborative working is emphasised in the IAPT clinician guideline for work with older people (Laidlaw et al., Reference Laidlaw, Kishita and Chellingsworth2016). There is, however, surprisingly little guidance on establishing collaborative relationships across generational divides. To deliver CBT in a way that maintains the ‘silver thread’ in all age services, cognitive behavioural therapists need to develop skills in working with people who may be as many as 70 years their senior. Although the age-gap was more likely to be only 40 years or so for the tCBT case studies, this still leaves plenty of opportunity for communication challenges due to the therapist and service user being from different generations. From the tCBT case studies, Harris and Hiskey (Reference Harris and Hiskey2015) describe the important strategy of seeking to identify the client’s frame of (personal) reference and also client–therapist shared knowledge frameworks. Strategies for developing collaboration across generational and cultural divides were illustrated more extensively by Mohlman and colleagues (Reference Mohlman, Cedeno, Price, Hekler, Yan and Fishman2008a), describing the case of Geoffrey, a 66-year-old African American man seeking to overcome anxiety and depression after years of addiction to crack cocaine. Mohlman and colleagues described establishing rapport through:

-

Reflective listening;

-

Presentation of a credible treatment rationale;

-

A collaborative approach to implementation and evaluation of treatment strategies;

-

Acknowledging and discussing demographic differences between the therapist and client;

-

Avoiding the ‘kid glove’ treatment that can become a self-fulfilling prophecy of under-achievement in therapy due to therapist or client falling prey to lowered expectations based on ageism;

-

Respect;

-

Modification of communication style to match the client’s;

-

Use of culturally relevant examples.

The foundation of a treatment rationale and action plan is a shared case conceptualisation, which necessitates finding a formulation that has a good sense of fit with the client’s lived experience whilst encapsulating a mechanism of change. The CCF was an important development in CBT in that it explicitly situates the individual within their personal, familial and cultural context. However, the central placing of Beck’s model of developmental psychopathology does not always sit comfortably with people experiencing late onset difficulties. Longitudinal ‘developmental’ and ‘stress-diathesis’ formulations can have a good ‘fit’ with people who identify with long-standing difficulties, or who recognise ‘triggering of negative self-schema’ in themselves. However, for those who do not regard negative early life experiences as being part of their personal history, or those whose distress is related to late life events such as retirement, bereavement or the onset of late-life illness, more suitable formulation approaches might be those that focus on ‘loss of positive’ (James et al., Reference James, Kendell and Reichelt1999), ‘understandable psychological consequences of life change/life event’ or ‘person-environment fit’ (Chaudhury and Oswald, Reference Chaudhury and Oswald2019). [For more on the interaction of positive and negative beliefs, see James et al. (Reference James, Kendell and Reichelt1999), or James (Reference James2010), p. 90–91.] Examples of the CCF in its entirety are available in Laidlaw’s more recent book (Laidlaw, Reference Laidlaw2014). However, clarifications on its use have also been provided in his subsequent works, including:

-

(i) Whether a life-long perspective is taken depends on whether it will enhance or distract from an understanding of the ‘here and now’ problem (Chellingsworth et al., Reference Chellingsworth, Davies and Laidlaw2016);

-

(ii) The central Beckian ‘depression’ model can be replaced with other CBT models. In other words, the five contextual elements can be placed around any diagnosis-based model (Laidlaw et al., Reference Laidlaw, Kishita and Chellingsworth2016, p. 57);

-

(iii) Therapists do not necessarily need to populate every element of the CCF with every client (Laidlaw et al., Reference Laidlaw, Kishita and Chellingsworth2016, p. 57);

-

(iv) Complexity must be balanced against parsimony such that the focus remains on change in the here and now (Chellingsworth et al., Reference Chellingsworth, Davies and Laidlaw2016);

-

(v) The five contextual factors are not mutually exclusive, e.g. cohort and intergenerational beliefs may overlap (Laidlaw et al., Reference Laidlaw, Kishita and Chellingsworth2016; p. 58).

Ian A. James had already offered an alternative solution to clarifications (i) and (ii) by re-drawing the CCF such that only the ‘here and now maintenance cycle’ is placed centrally, making personal history part of the contextual milieu (James, Reference James2010, p. 92).

An alternative ‘old age specific’ cognitive model comes in the form of Diehl and Wahl’s conceptualisation of ‘awareness of age-related change’ (AARC; Diehl and Wahl, Reference Diehl and Wahl2010) which suggests that a person becomes aware of ageing once they notice that life has changed due to some consequence of ageing in a domain of life that is important and meaningful [for an example, see Laidlaw et al. (Reference Laidlaw, Kishita and Chellingsworth2016), pp. 25–27]. Significant and sustained distress can be triggered by something seemingly trivial in the eyes of others, such as taking a wrong turning in the car, forgetting to take a cake out of the oven, or tripping up whilst walking in the street. An error that seems inconsequential to others may be appraised by the individual as an indicator of age-related incompetence. Beliefs about current or impending ineptitude can then be maintained and exacerbated by internalised ageism alongside catastrophic expectations of dependency and decline. It is also worth noting that the between-person discrepancy in appraisal of a single event, followed by focused hypervigilance for similar occurrences, can also occur the other way about, for example a family member making the catastrophic appraisal for an incident that the older person regards as inconsequential. As is central to cognitive therapy, it is not the events themselves but how we appraise them.

Recommendations for training and supervision

(1) Formulate the person in context, parsimoniously

CBT formulations can take an exclusively intra-personal perspective; for older people generally, and especially those with multi-morbidities, options for intervention are expanded when the individual is considered within the context of their physical and social environment, including family caregivers. If the Laidlaw comprehensive conceptualisation is used, it should be fully exploited to take into account the interactions between the contextual factors and the central maintaining cycle, and used parsimoniously to only include the material of relevance to the case at hand.

(2) Develop long-term conditions competences

Although an IAPT National Curriculum for CBT with Older People is in its second edition (Chellingsworth et al., Reference Chellingsworth, Davies and Laidlaw2016), it is not mentioned in the IAPT manual (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2018, updated 2021). Given the relevance of the national curriculum for CBT in the context of long-term persistent and distressing health conditions (NHS England and HEE, 2017), trainings to meet the long-term conditions (LTC) competences are strongly encouraged for all therapists who might work with older people. IAPT clinicians should receive weekly supervision by senior clinical practitioners with the relevant competences to support continuous improvement (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2018, updated 2021). For the new IAPT-LTC services, it is recommended that supervision is provided by clinical and health psychologists. Although not a required component, acceptance and commitment therapy and mindfulness meditation are competences cited in curriculum, with a recommendation to cover strategies for increasing observation and awareness, psychological flexibility and discussion of values. Transdiagnostic CBT has the advantage of addressing multiple difficulties by targeting mechanisms-in-common, and a modular approach to intervention delivery supports ‘flexible fidelity’, i.e. tailoring to the individual whilst working with a coherent framework. [For a case-based discussion of the balance between individualising treatment and using empirically supported approaches, see Mohlman et al., Reference Mohlman, Cedeno, Price, Hekler, Yan and Fishman2008b.]

(3) Consider differences in client–therapist age as a form of cultural diversity

Age is a protected characteristic (alongside disability, gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion or belief, sex and sexual orientation) for which public organisations have a duty to promote equality and reduce inequality (Equality Act, www.gov.uk/guidance/equality-act-2010-guidance). People should not be discriminated against on the grounds of age. In terms of its positioning within the CBT competences framework, age is considered alongside culture. As stated in the recent guidance on positive practice with older people (Age UK and BABCP, 2021), all other positive practice guides are relevant. The competences required by a therapist working with differences in cohort beliefs are akin to those used for any other attitudinal difference, for example due to religion or culture. Both therapist and client will be aware of the age differential and the associated differences in life experience. Rather than a focus on age per se, trainers and supervisors should encourage therapists to be aware of their own attitudes towards working with clients from different generations who may hold cohort beliefs that do not align with the beliefs of the supervisor or therapist. In order to be truly collaborative it may be necessary for the therapist to accept that the values may differ across cohorts (Laidlaw et al., Reference Laidlaw, Kishita and Chellingsworth2016, p. 57). Recognition of age differences requires adult-to-adult communication. Many older people strongly object to the categorisation of ‘old’ and actively reject the therapist that ‘speaks to them as if they are a child’ or provides ‘baby-ish’ or ‘simplistic’ materials. Tailoring to the individual is more important than following the commonly recommended adaptations of ‘large print’, ‘keeping things slow and simple’ and ‘choose behavioural rather than cognitive’.

(4) Be aware of common therapist beliefs, stereotypes and associated behaviours

The extent and direction of influence of an age gap on the therapeutic relationship depends on the perspectives of both client and therapist, and the skills of the therapist and their supervisor in addressing any associated ‘therapy interfering behaviours’.

Examples include:

-

(i) The Understandability Trap: also known as the ‘fallacy of good reasons’. An example is provided by Laidlaw and colleagues (Reference Laidlaw, Kishita and Chellingsworth2016, p. 6) where an empathic healthcare provider finds themselves thinking ‘If it happened to me, I’d be depressed too’. Over-empathising can paralyse the therapist or trigger ‘over-caring’ at the expense of client autonomy.

-

(ii) When respect is ‘too much of a good thing’: although respect is listed as a competence in the old age national curriculum, and is a key feature in Mohlman et al.’s recommendations for developing a collaborative relationship, it is not helpful if an over-respectful approach leads to a therapist remining quiet through much of the session. Younger therapists may be constrained by familial or cultural beliefs around the importance of respect for elders where it would be seen as ‘rude to interrupt’, or inappropriate to make suggestions to a person with so many years of lived experience.

-

(iii) ‘Therapeutic nihilism’ (‘what’s the point? – they’ll die soon anyway’) – the belief that a client’s presenting problems are an inevitable consequence of ageing – can lead to hopelessness in the therapist. It is true that none of us are going to get any younger, and it is also the case that there is nothing any of us can do to ‘turn the clock back’. However, depression is separable and reversible, and with passage of time can come change through fresh experiences and alternative perspectives; adverse circumstances can bring personal growth. Depression in people of any age makes it hard to see the light at the end of the tunnel, but believing that the light is there, albeit currently out of sight, is hope that therapists must hold for clients, irrespective of the age of the therapist, or the age of the client.

-

(iv) Fears of ageing, dependency and death: CB therapists may be put off by the feared or actual challenges of working with older clients, and may avoid working with clients from older generations. Ageing anxiety (personal fears about the changes associated with ageing) is associated with fear of death and lower optimism (Barnett and Adams, Reference Barnett and Adams2018), consistent with ‘terror management theory’. The bias against working with medically unwell clients is magnified by higher ageing anxiety and ageist attitudes (Caskie et al., Reference Caskie, Patterson and Voelkner2022). Supervisors do, however, need to be sensitive to the potential for vicarious traumatisation when young therapists are exposed to a client’s multiple losses and learn to fear their own futures. A recent trial of CBT with nurses working with older people led to a reduction in death anxiety (Rababa et al., Reference Rababa, Alhawatmeh, Al Ali and Kassab2021).

-

(v) Neurocognitive overshadowing: deficits in attention, perception, memory, language and executive functioning are features of many health conditions, including diagnostic categories seen in IAPT such as anxiety and depression. However, akin to the cognitive bias of ‘jumping to conclusions’, CB therapists often assume neurocognitive deficits in older people are due to irreversible neurodegenerative decline and reject the individual as unsuitable for therapy. Whilst dementia awareness and onward referral to appropriate services are encouraged, so are an understanding of the potential range of explanatory factors for neurocognitive change, and strategies for remediating and accommodating neurocognitive difficulties. [For neurocognitive training strategies that can be used alongside CBT see De Vito et al. (Reference De Vito, Ahmed and Mohlman2020); for consideration of the ethical and therapeutic aspects of giving feedback on cognitive deficits, see Pachana et al. (Reference Pachana, Squelch, Paton and Pachana2010); for information on CBT for people with dementia, see James (Reference James2010).]

-

(vi) ‘Adultism’: has been defined as ‘the oppression of children by adults’ which occurs when children receive consistent disrespectful and disempowering messages that make them believe that they are not valuable or deserving of respect simply due to their youth. As with other forms of oppression, individuals in the target groups may internalise the beliefs which subsequently guides their behaviour (Graham and King, Reference Graham and King2022). Graham and King developed a five-item scale of ‘adultist concerns’, with items such as ‘an older adult client would think I am not competent because of my age’ or ‘an older client would think that I can’t understand them because of my age’. They found evidence for psychologists-in-training living in the shadow of adultism, for example fearing being told that they are too young to help.

(5) Value intergenerational working

Rather than focus on what younger therapists need to be taught about older people, trainers and supervisors might instead identify strategies to instil in young therapists a sense of confidence in the benefits of their young age, and address barriers to collaboration. Younger therapists pre-occupied with their lack of life experience may hide their anxiety behind a strategy of over-performing, for example trying to prove their worth through information-provision or ‘powering through the protocol’, strategies that can slow rather than enhance either collaboration or change. People in later life often appreciate the company of those from younger generations, value the opportunity to contribute to learning, and feel energised in the presence of youthful vitality. Hearing from people who have lived long lives can bring new perspectives to young therapists and encourage reflection and reflexivity. Collaboration can grow from an acknowledgement that each party brings their own expertise to achieve a common goal, with the older person being the expert in their own life and times, and the younger therapist bringing knowledge of CBT skills and strategies.

Key practice points

-

(1) Literature on ‘counselling older people’ is more commonly focused on the challenges than the solutions (Smith and Pearson, Reference Smith and Pearson2011). In order to ‘embed the silver thread’, cognitive behavioural therapists must be equipped to work with multi-morbidities, for example through undertaking training in long-term conditions work.

-

(2) Collaboration across generational divides requires a willingness to engage with cultural differences associated with people from different generational cohorts.

-

(3) Cognitive behavioural therapists are strongly encouraged to acquaint themselves with existing materials, developed over the past 40 years of CBT with older people, and to use these as a basis for breaking new ground rather than re-inventing wheels.

Data availability statement

No new data are presented.

Acknowledgements

This paper is written in recognition of discussions with and reflection from trainees, trainers, supervisors and older service users ‘thinking CBT’. The anonymous reviewers are thanked for their suggestions for improving an earlier version.

Author contribution

Georgina Charlesworth: Methodology (lead), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing (lead).

Financial support

None.

Conflicts of interest

G.C. is a practising clinical psychologist who has published previously on CBT in later life.

Ethical standards

The author has abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.