Introduction

The model presented in this paper has its origins in two observations made by the author in clinical work and in teaching reflective practice: (1) that professional reflective practice has a lot in common with clinical practice when both practitioners and clients are conceptualised as experiential learners, and (2) when conceptualising client problems, there is often a core cognition or constellation of cognitions (called here the ‘Big Idea’) plus a set of psychological and behavioural processes that exert reciprocal influence to maintain the problem. Two conclusions followed from these observations: (1) a model of experiential learning that could be applied to the theory and practice of cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) might usefully be developed by adapting those used in professional reflective practice, and (2) explicitly identifying the ‘Big Idea’ and placing it in the centre of an experiential learning cycle might make the therapeutic tasks and goals clearer for client and therapist.

Psychotherapy has long been considered a learning process (Bandura, Reference Bandura1961), a perspective that is central to the cognitive behavioural psychotherapies; Beck and Weishaar (Reference Beck, Weishaar, Freeman, Simon, Beutler and Arkowitz1989) state that ‘cognitive therapy uses a learning model of psychotherapy’ (p. 30) and in the foundational treatment monograph Cognitive Therapy of Depression by Beck et al. (Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery1979), the approach is described as consisting of ‘highly specific learning experiences’ (p. 4). Bruijniks et al. (Reference Bruijniks, DeRubeis, Hollon and Huibers2019) note that, while the exact working mechanisms of CBT remain unknown, CBT is a skills-based approach that relies on learning and memory where learning capacity moderates treatment success; and Beck (Reference Beck1976) remarked that the task of CBT is not to solve all a client’s problems in therapy but to assist them in ‘learning to learn’ (p. 230) so that they might ultimately become their own therapist (Beck, Reference Beck2011; Knapp and Beck, Reference Knapp and Beck2008). Because the therapist’s interventions are intended to facilitate reflection and self-reflection that enable the client to develop more adaptive constructions of self, experience and the world, CBT’s mode of action might usefully be conceptualised as facilitated experiential learning (Milne et al., Reference Milne, Claydon, Blackburn, James and Sheikh2001).

Developing the art and skill of CBT practice involves a continuing process of learning through reflection on experience (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Chaddock, Davis, Dallos and Stedmon2009), specifically reflecting on and evaluating one’s personal values, clinical competence, and limitations as a CBT practitioner (Hool, Reference Hool2010). Self-practice/self-reflection (SP/SR) is increasingly used in training CBT practitioners to enhance skilfulness by requiring trainees to apply CBT theory and techniques to themselves and share the results of that learning in a supportive learning community, with encouraging results (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Lee, Travers, Pohlman and Hamernik2003). The role of reflection and self-reflection as cognitive-affective skills that enhance capacity for experiential learning could therefore be considered an integral part of both the remediation of client problems through CBT and the professional development of reflective practitioners.

If we were to conceptualise both clients and CBT therapists as experiential learners who seek to become more skilful, we might find that there are processes in common that can inform both training and practice. A modified version of Terry Borton’s (Reference Borton1970) ‘what, so what, now what’ teaching model has therefore been developed to illustrate the role of experiential learning processes in the maintenance of client problems, remediation of those problems in CBT, and in professional development. This paper starts by describing an adapted ‘cloverleaf’ model that places the person of the learner at the heart of three interlocking psychological and behavioural processes: selective attention to salient features of lived experience; cognitive-affective reflective processes that construct meaning from experience; and intentional action as a form of adaptive behavioural experimentation. The model can be used to formulate the maintenance of diverse client problems in terms of learning processes as well as to conceptualise guided discovery, the overall course of treatment, and the conduct of an individual session. Finally, it describes how the model can be used to conceptualise the role of reflection in professional development both in SP/SR and to understand common difficulties that therapists may experience when practising CBT.

The cloverleaf model of experiential learning

Experiential learning has been defined as ‘a methodology of education which has a learning impact on the whole person, including feeling (affect) and behavior, in addition to cognitive stimulation’ (Hoover, Reference Hoover1974; p. 1). Experiential learning’s epistemological roots are in constructivism which regards learning as a process of meaning-making; knowledge is represented in conceptual structures (schema) and constructed through the interaction of the learner with the physical world, in collaborative social settings, and in a cultural and linguistic context (Sjøberg, Reference Sjøberg, Baker, McGaw and Peterson2010). The key role that reflection plays in experiential learning can be traced to the educational theories of John Dewey, the American philosopher, psychologist and educationalist (Roberts, Reference Roberts2006). Dewey (Reference Dewey1938) proposed that learning is mediated by ‘reflective thought’, a systematic, rigorous and disciplined mode of thinking that happens in interactions with other people and requires an attitude that values personal and intellectual growth in oneself and others. Reflection, or reflective thought, enables the learner to make meaning from experience that leads to a deeper understanding of the relationship between experiences and ideas (Rodgers, Reference Rodgers2002).

David Kolb (Reference Kolb1984) synthesised Dewey’s theory of learning with Kurt Lewin’s similar model and Jean Piaget’s developmental psychology to produce a circular model of learning through reflection on experience. Kolb’s model iterates around four processes to form an upward spiral of learning. A person’s engagement with lived concrete experience (CE) provides the raw data for reflective observation (RO). Reflecting on experience leads to the development of rules or principles through abstract conceptualisation (AC), which is a precursor to further intentional active experimentation (AE), which then provides the raw material of further concrete experience. Experience is grasped both perceptually (CE) and intellectually (AC) and transformed through reflection (RO) and intentional action (AE) (Roberts, Reference Roberts2006). However, not all experience is educative; as Dewey (Reference Dewey1938) points out, ‘Any experience is miseducative that has the effect of arresting or distorting the growth of further experience’ (p. 25).

Kolb’s model has been widely used in adult education (Lewis and Williams, Reference Lewis and Williams1994) and applied to CBT (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Westbrook, Fennell, Cooper, Rouf, Hackmann, Bennett-Levy, Buttler, Fennell, Hackmann, Mueller and Westbrook2004; Milne et al., Reference Milne, Claydon, Blackburn, James and Sheikh2001). However, Borton’s (Reference Borton1970) similar but somewhat earlier model has become increasingly influential in professional reflective practice (Rolfe, Reference Rolfe2014) and clinical supervision (Driscoll, Reference Driscoll2000). Borton derived his model from reflections on his experience as an American high school teacher working with under-privileged pupils; his aim was to develop an educational philosophy and curriculum that could ‘reach students at basic personality levels, touch them as individual human beings, and yet teach them in an organized fashion’ (Borton, Reference Borton1970; p. vii, italics in original). Borton described three interacting psychological processes: sensing, a perceptual function which intuitively picks up information; transforming, which conceptualises, abstracts, evaluates and gives meaning and value to the sensed information; and acting, which describes the process of rehearsing possible actions and picking one to enact. The model relies on feedback; once action is taken, the difference between the intended effect of the action and the actual effect is itself sensed and evaluated. Reflection on the disparity between intended action and what is seen to occur provides the basis for further action, thus completing a cycle of learning.

Borton (Reference Borton1970) coined a short colloquial phrase to capture the essence of each process:

‘“What?” for Sensing out the differences between response, actual effect, and intended effect; “So What?” for Transforming that information into immediately relevant patterns of meaning; “Now What?” for deciding on how to Act on the best alternative and reapply it in other situations. This What, So What, Now What sequence became the model on which we built a curriculum designed to make students more explicitly aware of how they function as human beings.’ (pp. 88–89).

Aware that a teacher’s influence was limited, Borton’s (Reference Borton1970) educational goal was to find ways to teach his disadvantaged young pupils enduring processes through which they could change themselves. His curriculum was designed to raise consciousness, which he described as a person’s capacity to view experience more objectively, comparable to Beck’s (Reference Beck1976) concepts of cognitive distancing and decentring. Borton believed that if people could turn their information processing system in on itself then it could lead to ‘self-generating growth’ (p. 87).

Borton’s (Reference Borton1970) model might be preferred over Kolb’s as a model for reflection in CBT for four reasons. Firstly, it is inherently easier to grasp than Kolb’s model; for example, the language is more accessible, making it potentially easier to use. Secondly, Borton’s model aligns with CBT in that it is based on a theory of human information processing that was a product of the same cognitive revolution in psychology in the 1960s that paved the way for the development of the cognitive behavioural therapies (Mahoney, Reference Mahoney1974). Thirdly, both Borton’s model and Beck’s cognitive therapy are metacognitive in that they focus on ‘learning to learn’ (Beck, Reference Beck1976; p. 230). Fourthly, while Kolb’s model separates reflective observation from abstract conceptualisation, Borton’s model is more economical in that it subsumes abstract conceptualisation under ‘transforming’, which is synonymous with reflection and self-reflection.

Borton’s (Reference Borton1970) information processing perspective is, however, somewhat dated (Rolfe, Reference Rolfe2014) and might be enhanced by a biopsychosocial description of the person of the learner at the centre of the learning process. The person of the learner as conceived of here is based on a range of complementary theories, including Mischel’s (Reference Mischel2004) cognitive-affective processing system model of personality, the personal construct psychology of Kelly (Reference Kelly1955), Bandura’s (Reference Bandura1978) reciprocal determinism, Beck’s model of the role of schemas (Beck and Haigh, Reference Beck and Haigh2014), and the developmental psychology of Piaget’s cognitive constructivism, and Vygotsky’s social constructivism (Sjøberg, Reference Sjøberg, Baker, McGaw and Peterson2010).

In summary, while the person of the learner is influenced by an underlying physiological reality in terms of temperament or genetic pre-dispositions and by their unique psychosocial-developmental learning history (Mischel, Reference Mischel2004), individuals are active rather than passive players in their lives (Hammen, Reference Hammen2006). Metaphorically, they are personal scientists who are actively making meaning from experience and refining their construction of reality (Kelly, Reference Kelly1955) in a social context in which there is a ‘continuous reciprocal interaction between behavior and its controlling conditions’ (Bandura, Reference Bandura1971; p. 2). What we think of as fixed personality traits are a repertoire of situationally consistent behaviours that depend on the perceived meaning of a situation. Idiosyncratic meanings are derived from the operation of a dynamic, interactive cognitive-affective processing system that draws on the construal and representations of the self, people and situations, as well as a person’s goals, expectations, beliefs, feeling states, and memories of people and past events (Mischel, Reference Mischel2004). These construals are organised in schemas, although Mischel and Shoda (Reference Mischel and Shoda1995) prefer the term cognitive-affective units to emphasise the interrelationship between cognition and emotion in processing social information relevant to the self and one’s future. Schemas categorise and evaluate experience by screening out, differentiating and coding relevant stimuli (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery1979). Self-schemas consist of ‘cognitive generalizations about the self, derived from past experience, that organize and guide the processing of self related information contained in an individual’s social experience’ (Markus, Reference Markus1977; p. 63). They allow people to organise, summarise or explain their behaviour in specific domains of experience. Interpersonal schemas affect the ways that people attend to and make meaning from relational experience; they are responsible for a dynamic interaction between the self and one’s interpersonal and socio-political environment (Safran, Reference Safran1984). Schemas have plasticity so learning can be understood cognitively in terms of either assimilating new information within existing schemas or accommodating unassimilable experience by altering the structure of the schema itself, as Piaget describes (Sjøberg, Reference Sjøberg, Baker, McGaw and Peterson2010). Learning can also be understood socially in terms of educational interactions between a learner and more knowledgeable others. If pitched within the learner’s zone of proximal development, these interactions move the learner from proximal to actual development, such that what a person ‘can do in cooperation today he can do alone tomorrow’ (Vygotsky, Reference Vygotsky1986; p. 188). The person of the learner is therefore agentic, mutable and interactive; that is, they act on and are acted on by the world, and thus continue to learn and develop across the lifespan in a process of continual adaptation to ecological niches (Lee, Reference Lee and Banks2009).

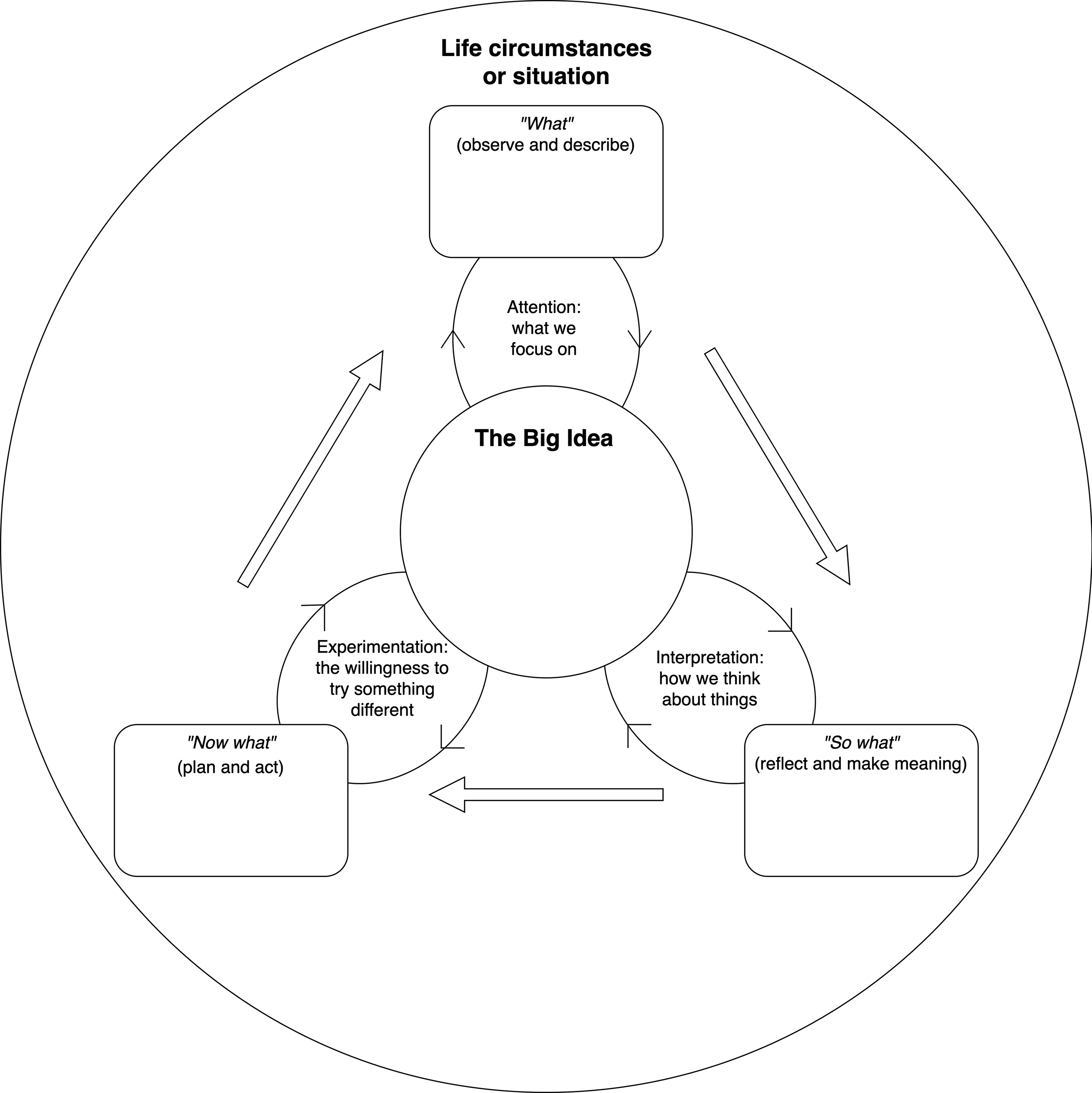

Combining this conceptualisation of the person with Borton’s model of the processes that underpin learning gives rise to a cloverleaf model where the person of the learner is at the centre of a circular experiential learning process consisting of: (1) perceptual and attentional processes that shape a person’s focus on relevant aspects of their life circumstances and lived experience (the ‘what’ of sensing), (2) cognitive-affective processes that generate reflection on experience to understand it better and make meaning from it (the ‘so what’ of transforming), and (3) motivational and behavioural processes that, ideally, align with the person’s desires, goals and values in order that they can act with intentionality on the basis of their reflections (the ‘now what’ of acting). Radiating out from the person at the centre of this ‘cloverleaf’ design are ‘petals’ that show reciprocal patterns of influence between the person and each process: what is sensed is determined by who is doing the sensing and their expectations (Shevrin and Dickman, Reference Shevrin and Dickman1980); what is known, depends on the knower’s epistemic capabilities, for example their capacity to use ‘mature’ over more ‘primitive’ thinking to distance and decentre from ‘hot’ (affectively prepotent) cognitions (Beck, Reference Beck1976; Beck et al., Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery1979); what is done depends on having a repertoire of adaptive behaviours and the capacity to self-regulate (Mischel and Ayduk, Reference Mischel and Ayduk2002). Although the model shows a sequential, closed process, the divisions are somewhat arbitrary and interact in a dynamic fashion (Borton, Reference Borton1970). The person and their process of learning exist in a social, cultural and relational context. People connect with complex social systems at the micro (relational) and macro (cultural) level; they learn in interactions with others, in social settings, and by using cultural artifacts that both constrain and modify the meanings of what is sensed, known, and done (Lee, Reference Lee and Banks2009). This adapted experiential learning model is the basis for understanding and explaining the maintenance of client problems, the CBT therapeutic process, and practitioner professional development (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. The generic cloverleaf model of experiential learning (after Borton, Reference Borton1970).

Applications to understanding the maintenance of common client difficulties

Dobson and Dozois (Reference Dobson, Dozois and Dobson2010) describe CBT as an umbrella term for a heterogenous group of theories and therapeutic practices whose proposed mechanisms of change are based on a common cognitive mediational model, i.e. that cognitive activity affects behaviour; can be monitored and altered; and, when altered, can lead to desired changes in behaviour. The version of CBT that is most widely taught and practised in the UK is a modified version of Beck’s cognitive therapy based on the generic cognitive model (Trower, Reference Trower, Dryden and Branch2012). The generic model states that both everyday psychological problems and clinical disorders result from the accentuation of otherwise normal adaptive functioning due to biased information processing. Systematically biased interpretations of events are a consequence of a complex process where genetic pre-dispositions, selective attention, and formative experiences interact to form relatively enduring knowledge structures (schemas) that incorporate biased beliefs (Beck and Haigh, Reference Beck and Haigh2014). Beck’s generic model was modified by Clark (Reference Clark1986) who emphasised a circular model of problem maintenance, and Salkovskis et al. (Reference Salkovskis, Clark and Gelder1996) who highlighted the role of safety-seeking behaviours that prevent disconfirmation of inaccurate or maladaptive beliefs, preventing adaptive learning from taking place (Trower, Reference Trower, Dryden and Branch2012).

More recent CBT models focus on a wider range of psychological processes than biased interpretations, as well as emphasising the adaptive role of emotion in human functioning (Trower, Reference Trower, Dryden and Branch2012). These models include: (1) Teasdale and Barnard’s (Reference Teasdale and Barnard1993) Interacting Cognitive Subsystems model which distinguishes between a verbal, logical, propositional mode of information processing and an emotionally rich, intuitive, implicational system responsible for ‘hot’ cognitions; (2) Wells’ (Reference Wells2000) Self-Regulatory Executive Function (S-REF) model which focuses on the role of worry and rumination, threat monitoring, and maladaptive coping behaviours that either impair flexible self-regulation or prevent corrective learning experiences; (3) Brewin’s (Reference Brewin2006) retrieval competition theory which proposes that dysfunctional belief structures are not themselves changed in successful treatment but alternative positive belief structures are constructed that win a competition for retrieval from memory; and (4) the transdiagnostic approach of Harvey et al. (Reference Harvey, Watkins, Mansell and Shafran2004), which focuses on how self-focused attention, selective memory retrieval, reasoning biases, rumination, and behavioural avoidance/safety-seeking behaviours contribute to the aetiology and maintenance of a wide range of conditions.

Formulation acts as a bridge between CBT theory and practice; it describes the processes that maintain common psychological problems and is a way to tailor generic treatment protocols to individual circumstances and presentations (Westbrook et al., Reference Westbrook, Kennerley and Kirk2007). Appearing to take to heart Kurt Lewin’s maxim that ‘there is nothing more practical than a good theory’ (Lewin, Reference Lewin1952; p. 169), CBT theorists have developed a substantial body of generic and disorder-specific maintenance formulations based on the cognitive content-specificity hypothesis (Beck, Reference Beck1976; Beck and Perkins, Reference Beck and Perkins2001). Several of those models also use a similar flower shape that show in diagrammatic form the relationship between psychological and behavioural processes and the hypothesised core of the disorder. Westbrook et al.’s generic template shows petals that represent diverse ‘vicious cycle’ maintenance processes radiating out from the problem as defined by its unique cognitive, affective, physiological and behavioural components. These vicious cycles include safety-seeking behaviours, escape and avoidance, scanning and hypervigilance, catastrophic misinterpretation, and self-fulfilling prophecies. At the centre of the Salkovskis (Reference Salkovskis2007) vicious flower model of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a misattribution of the significance of intrusions combined with excessive beliefs in personal responsibility to prevent harm to self or others. Radiating out are four maintenance processes: neutralising actions such as rituals; counter-productive safety-seeking behaviours; attention and reasoning biases; and mood changes. Moorey’s (Reference Moorey2010) ‘sad flower’ model of depression places Beck’s depressive mode (Beck and Haigh, Reference Beck and Haigh2014) at the heart of six processes: automatic negative thoughts, rumination and self-attacking, low mood and emotional sensitivity, withdrawal and avoidance, unhelpful behaviours, and decreased motivation and changes to physical regulation.

The cloverleaf model is agnostic about the various models and processes described above; it uses the superordinate concept of experiential learning to attempt to show that common psychological problems can be understood in a learning context. That is, problems are maintained when a person in a specific ecological niche employs ineffective cognitive and behavioural coping responses to adversity that hinder opportunities to learn and practise more adaptive coping and self-regulation. The cloverleaf model is therefore theoretically compatible with any model that recognises that cognitively mediated learning is relevant to the maintenance of psychological distress, that learning is fundamental to adaptation, and that learning can be described in terms of the person of the learner and the ways that they make meaning from their interactions in a social world. In the cloverleaf model, each psychological and behavioural process is seen not as operating individually to produce a cumulative effect, but in interaction with each other to inhibit or facilitate adaptive learning. The focus of the model is the quality of experiential learning that is taking place and its role in successful person-situation adaptation.

When formulating problem maintenance, the cloverleaf model describes a mutual influence between the person and the processes that maintain a problematic relationship to lived experience and to learning from it. At the centre of the model is the person and their problematic trait and state characteristics. Enduring traits might influence the way that a person perceives, thinks and acts; a person might have knowledge deficits in relevant areas, for example about the course and prognosis of the condition, skill deficits in tackling adversity, or more general unhelpful attitudes and beliefs, for example about seeking help. State characteristics, such as symptoms themselves, can interfere with emotional, physiological, cognitive and behavioural functioning and thus the capacity to engage in and learn from experience.

Perceptual processes such as selective attention can focus attention on adversity and perceived threat in what are often objectively difficult, restricted or impoverished life circumstances. Rigid, unproductive and biased thinking fails to challenge credible but inaccurate or unhelpful assumptions. These assumptions are compounded by perseverative cognitive processes such as worry and rumination that inhibit creative thinking and may lead to a preoccupation with adverse life circumstances. In turn, these non-reflective thinking patterns influence people to apply reactive, habitual or life-limiting actions derived from over-learned responses. The negative consequences of these behaviours create more instances of life experience that confirm existing views of oneself or of one’s situation, provoke self-attacking thoughts, and may worsen a person’s life circumstances, for example through failing to attend to necessary life tasks. Opportunities for learning are diminished when unhelpful constructions of the self and world lead to maladaptive actions that manifest as self-fulfilling prophecies (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Ineffective, unskilful or inhibited experiential learning processes.

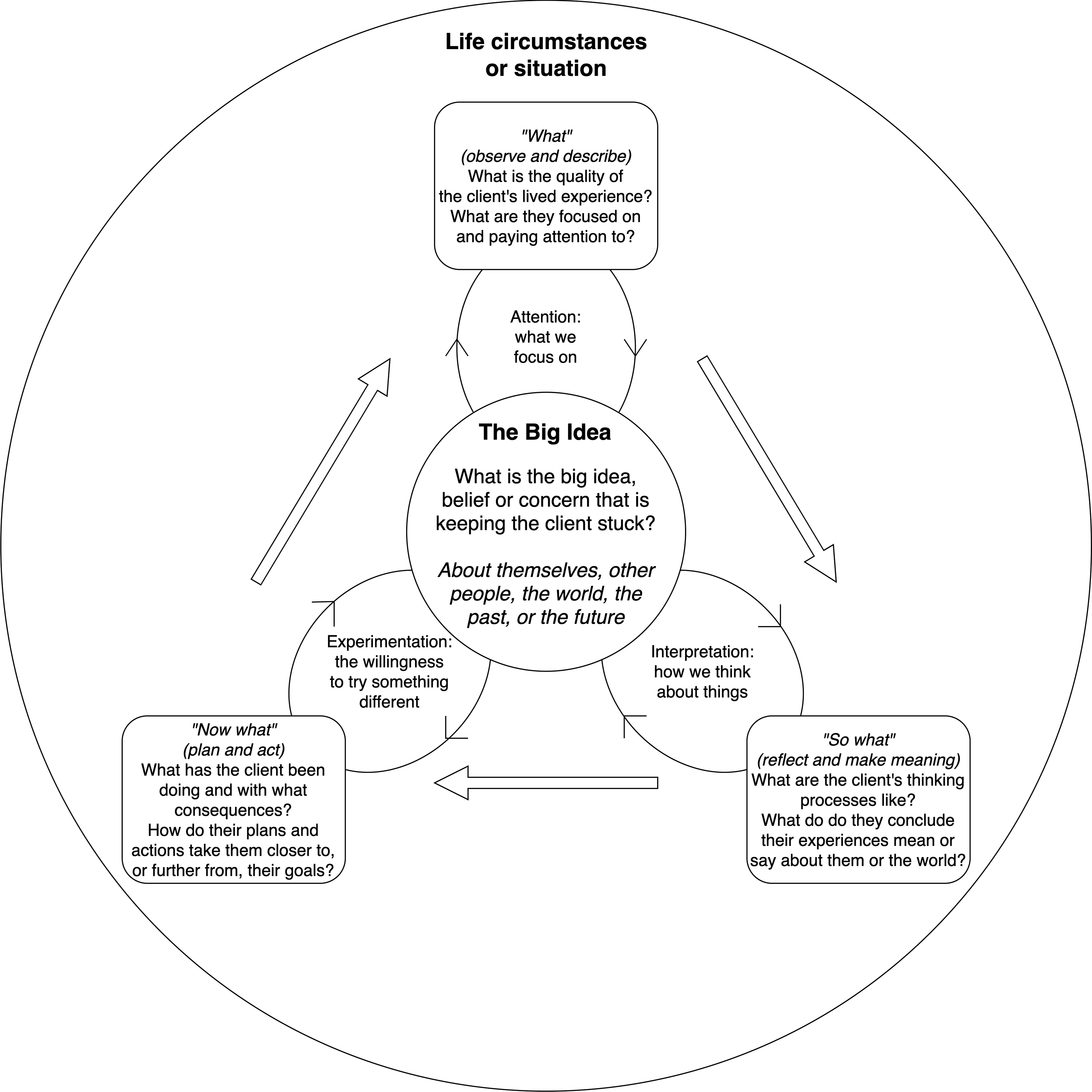

The cloverleaf model can be applied to diverse presentations using Beck’s (Reference Beck1976) cognitive specificity hypothesis by showing how a key cognition, or constellation of cognitions, influence the interlocking psychological and behavioural processes. The phrase the ‘Big Idea’ is used to represent key cognitions to reinforce their centrality to the maintenance of the problem. For example, in Beck’s (Reference Beck1976) model of depression, the Big Idea might consist of a constellation of perceptions of irredeemable loss, failure and defeat, worthlessness and unlovability, and the futility of attempts to rehabilitate one’s life. These cognitions, plus the dominant affective, motivational and physiological features of the condition, influence the processes that maintain low mood. These processes include the ‘what’ of biased attention to features of current experience that conform to depressed expectations, the ‘so what’ of rigid and inflexible constructions of past, present and anticipated future experience, and the ‘now what’ of avoidance, withdrawal and actively unhelpful actions, e.g. alcohol misuse. Viewed as a process of inhibited learning, the ‘what, so what, now what’ cycle of depression aggravates the key features of the condition, as well as having a potentially negative impact on the depressed person’s life situation (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. The maintenance of depression as an experiential learning process.

In the Salkovskis (Reference Salkovskis2007) model of OCD, the Big Idea might be represented as a catastrophic conditional assumption focused on exaggerated responsibility, for example, ‘if I don’t control my thoughts, I could do something really terrible, which would make me an awful person’, sometimes referred to as the person’s ‘Theory A’. To the extent that Theory A is both credible and meaningful, it may come to dominate the response to ego-dystonic intrusions in ways that inhibit the necessary learning that intrusions are not dangerous per se. For example, a person can (1) become focused on and highly vigilant for possible threat, leading them to, (2) use biased and unhelpful thinking both to over-estimate danger and the awfulness of events, as well as to minimise personal coping and environmental resources, and (3) take ineffective and unhelpful action such as ritualised neutralising actions, avoidance or safety-seeking behaviour. The cloverleaf model does not attempt to alter any of the key assumptions of the Salkovskis model that ineffective coping strategies prevent contact with events that could disconfirm unhelpful assumptions. It does, however, put this process and its components at the centre of a maladaptive learning cycle that makes clear both the way that unhelpful beliefs mediate the response to intrusions, and the way that ineffective coping prevents the possibility of trialling through experimentation, and then reinforcing, a more adaptive belief (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. A cloverleaf maintenance formulation of OCD.

The cloverleaf model can also be used for descriptive formulations that link the ‘Big Idea’ with a specific situation. For example, collaboratively formulating a client’s difficulties using the Clark and Wells (Reference Clark, Wells, Heimberg, Liebowitz, Hope and Schneier1995) model of social anxiety, revealed the idiosyncratic ‘Big Idea’ that ‘People reject you if you act strangely: I couldn’t cope with the pain of rejection’. This led to the situation-specific assumption that ‘When I meet my friend for coffee, I could start shaking. He will think I’m weird and not want anything more to do with me’. This chain of assumptions pre-disposes the person to focus both on their social presentation (‘I look jittery’) and physiological indications of anxiety (‘My heart is racing’). They process that information unrealistically (‘I’m going to start shaking uncontrollably if I don’t do something right away’), leading them to take unnecessary remedial action, for example, repeatedly going to the toilet to wash their face in cold water and frequently checking their phone to avoid eye contact. This behaviour has the unfortunate effect of potentially leading to a self-fulfilling prophecy if it elicits unwelcome and embarrassing concern (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. A descriptive formulation of a situation that perpetuates social anxiety.

Creating collaborative formulations using the model can validate how a client’s focus of attention, assumptions, and behaviour make sense if the Big Idea is true but have the unintended consequence of preventing the client from learning that alternative, more helpful, constructions of reality are also possible. In the above example of social anxiety, the client might conclude that ‘I don’t give myself the chance to learn that I might not come across as badly as I fear; I’m unlikely to start shaking uncontrollably; even if I did, my friend is more likely to be sympathetic than judge or reject me’. For the therapist who bears the structure of the model in mind, it can make clearer the implication that if the client’s learning processes can be mobilised in a spirit of non-judgemental, open-minded curiosity, in collaboration with the therapist’s expertise in facilitating experiential learning, then change is possible. By focusing on the role of experiential learning processes and making them explicit, clients can be socialised to the idea that treatment is an opportunity for learning.

Cognitive behaviour therapy as facilitated experiential learning

The idea that psychotherapy, including CBT, is a form of learning has a long history. Bandura’s (Reference Bandura1961) ‘Psychotherapy as a Learning Process’ stated that the meaningful question was not ‘Does psychotherapy work?’, but ‘Can human behavior be modified through psychological means and if so, what are the learning mechanisms that mediate behavior change?’ (p. 143). Bandura discussed the role of psychotherapeutic practices derived from learning principles including counter-conditioning, extinction, discrimination learning, methods of reward, punishment, and social imitation. Since the cognitive revolution, learning has been understood in terms that take account of (1) individual meaning-making, for example in the cognitive constructivism of Piaget, and (2) contextual factors, for example in the social constructivism of Vygotsky (Sjøberg, Reference Sjøberg, Baker, McGaw and Peterson2010). For Mahoney (Reference Mahoney1988), psychotherapy is not ‘essentially different from the process of any other form of human inquiry and learning. It involves an active trial-and-error testing of experiential styles with the intent of developing more viable and satisfying ways of “being in the world.”’ (p. 307). The neuroscientist LeDoux has described a psychotherapy session as ‘A learning experience, one in which memories formed during the session help the person cope with personal challenges in their life’ (LeDoux, Reference LeDoux2015). In designing the revised Cognitive Therapy Scale, Milne et al. (Reference Milne, Claydon, Blackburn, James and Sheikh2001) made use of Kolb’s (Reference Kolb1984) model to conceptualise the tasks and goals of CBT as experiential learning, as follows:

‘In effective therapy patients will tend to reflect on their situation, engage in new experiences (including behaving in alternative ways), engage in problem solving and coping strategies, and finally develop alternative theories and concepts of their world. The information within this system will flow continuously around the cycle interactively, and true accommodation will occur when the information processed leads to a new construction of the world.’ (p. 23)

The view of therapy as an opportunity for learning is uncontroversial; any form of enduring change must involve explicit or implicit learning, at least in the broadest sense. As Orlinsky (Reference Orlinsky2009) points out, ‘When a therapist’s intervention is appropriate, and a patient’s cooperation engages positively with it, chances are good that the patient will “learn” something useful’ (p. 330). However, the approach taken here is that the experiential learning typical of the cognitive behavioural therapies concerns the purposeful reconstruction of meaning through a facilitated process of engagement with alternative constructions of experience. This view can be traced to the work of George Kelly (Reference Kelly1955), whose personal construct psychology had a ‘prominent impact’ on Beck’s cognitive therapy (Knapp and Beck, Reference Knapp and Beck2008: p. 57). Kelly’s central metaphor was of the person-as-scientist, which is at the core of his theory of constructive alternativism, by which he meant the ability to make alternative constructions of experience. In Kelly’s psychology, people learn by being open to new information that refines existing ways of construing themselves and their world. Whether supervising graduate students or in his clinical practice, Kelly practised a similar method of inquiry with each that has a lot in common with contemporary CBT. His goal was to try to help a person:

‘To pinpoint the issues, to observe, to become intimate with the problem, to form hypotheses, to make test runs, to relate outcomes to anticipations, to control his ventures so that he will know what led to what, to generalise cautiously, and to revise his dogma in the light of experience’ (Kelly, Reference Kelly and Maher1969; p. 61).

Constructive alternativism anticipated CBT’s therapeutic strategy of collaborative empiricism, which is also a process of joint enquiry between therapist and client. In the generic model of CBT, the tasks of collaborative empiricism are, firstly, to identify maladaptive beliefs associated with problematic situations, and secondly, to design, implement and evaluate empirical tests of those beliefs, a process known as cognitive reconstruction (Beck and Weishaar, Reference Beck, Weishaar, Freeman, Simon, Beutler and Arkowitz1989). Socratic questioning is a discursive cognitive reconstruction strategy used in CBT to examine the meaning and validity of beliefs. Padesky (Reference Padesky1993) has framed Socratic questioning not as a tool to change the client’s mind by pointing out the logical flaws in their beliefs, but as a form of exploratory guided discovery that makes a client’s underlying beliefs and their context explicit. Using the facilitative skills of empathising and careful listening, the therapist asks detailed informational, or ‘what’, questions to elicit what the client thought, felt and did in a given situation, and with what consequences. The therapist then asks synthesising ‘so what’ questions to explore the meaning ascribed to experience and its implications. The cloverleaf model adds an explicit experimentation stage by using ‘now what’ questions to help clients design in vivo tasks to consolidate learning. The cloverleaf format helps the therapist navigate in a structured way the tasks involved in facilitating learning through guided discovery in a way that mirrors the therapist’s use of their reflective system (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Chaddock, Davis, Dallos and Stedmon2009): first to focus attention on a problem, then to reconstruct experience by observation and description, next to synthesise and conceptualise, and finally to plan and act. Targeted focal questions help to move around the cycle. For example: ‘what did you find yourself paying attention to, and why; so what did you make of what you noticed and what other ways are there of thinking about what happened; now what do you think it would help to do as a result of this new way of thinking about the situation?’. Learning is consolidated by checking what impact this process has had on the focal Big Idea identified at the centre of the formulation in the context of the client’s life circumstances.

The difference that Padesky (Reference Padesky1993) describes between Socratic questioning as a tool for changing minds versus guiding discovery was anticipated by Borton’s (Reference Borton1970) two modes of questioning. The first is the analytical mode; an approach that is ‘hard-driving, pointed, sharp, logical, tough, and rigorous’ (p. 89). However, because people find it difficult to change if put under too much pressure, Borton also recommends employing an intuitive contemplative mode that ‘allows alternatives to suggest themselves through free association and metaphor’ (p. 89). Skilful CBT practitioners intuit these differences, sensing when to push clients gently to confront the logical incompatibilities between what they believe and the evidence for it, with the sensitivity required to know when a client needs time and space to reconstruct their understanding in a way that facilitates schema accommodation. A more contemplative mode may be particularly useful, for example, if clients with rigid beliefs feel anxious, disorientated or overly challenged by analytical cognitive reconstruction that questions their familiar ways of construing the world and threatens the coherence of their self-concept.

Another way to reduce anxiety that could inhibit learning is by therapist and client filling in a blank template together, which shifts the focus from an interpersonal encounter to an external, shared project (see Fig. 6). The labels on the template can act as prompts that distinguish between the Big Idea and the processes that maintain it; when the Big Idea is active, clients can describe ‘what’ they pay attention to, the ‘so what’ of how they think about their perceptions, and the ‘now what’ of planning and acting as if the Big Idea were wholly true. The blank template can also be filled in with a more hopeful and positive cycle of learning that stands in contrast to the problem cycle. For example, a client might articulate their ‘Theory B’, that is the Big Idea by which they would like to live their life. A client struggling with low self-esteem might describe their preferred Big Idea as ‘learning to trust my judgement’, another struggling with ego-dystonic sexual intrusions to ‘accept myself as the sexual person I really am’. They would then elaborate what they would be paying attention to, for example focusing on opportunities and broadening their perceptions in the service of enhancing life experience. They might ask so what they would like their life to mean or represent, so what might a flexible, curious and constructive thought process look like, and so what would it mean to respond skilfully and flexibly to troubling thoughts and feelings? Next, they might consider now what they would like to do to plan and invest in personally meaningful and potentially rewarding activities, rather than continue to live a restricted, avoidant, or overly cautious life.

Figure 6. Blank cloverleaf template.

In the author’s practice it has been helpful to place the negative and positive learning cycles side by side so that clients can grasp the difference between life as it is being lived with the problem, or problematic belief, in control of their attention, thinking and actions, as opposed to a vision of what life would look like if the client (1) exercised more choice over what they pay attention to, (2) chose how or whether to engage in reflection on their perceptions, and (3) engaged in purposeful planning and action to expand their horizons. For one anxious and depressed client this was described as the contrast between ‘a circle of fear that I keep nurturing’ versus ‘embracing life and its possibilities’. In the latter case they said that they would make more effort to notice and pay attention to positive events and feelings, let themselves recognise that good things can happen and do last, and experiment with enjoying the moment and allowing wants and desires to surface and be taken seriously.

In other words, the cloverleaf model can help clients develop the vision of an increasingly positive, open and reflective learning cycle where they adapt creatively to, and enhance, their life situation. In a reflective learning cycle people attempt to make the ‘what’ of their lives more expansive and less restrictive by paying balanced attention to all relevant aspects of lived experience. Through a process of critical yet compassionate reflection and self-reflection (an enhanced, reflective ‘so what’ cognitive-affective stance) people develop more flexible, curious and constructive thinking patterns. With a willingness to experiment through ‘now what’ actions, people are encouraged to take intentional action in pursuit of valued goals. Experimentation leads to opportunities for experiences that contribute to personal growth and satisfaction. Emerging from these processes, and influencing them in turn, we might hope that the person of the learner develops (1) a more compassionate and accepting view of their vulnerabilities along with (2) the remediation of painful symptoms, based on (3) developing an accurate understanding of events, increased self-awareness, greater interpersonal skilfulness, improved emotional and behavioural self-regulation, and more helpful attitudes and beliefs, as well as an improved life situation. Clients do not need to learn CBT in as much detail as a practitioner does to become their own therapist; it is the development of an enduring cycle of enhanced experiential learning that may ultimately enhance resilience and be protective against relapse (Fig. 7).

Figure 7. Skilful and effective experiential learning processes.

Uses of the cloverleaf model to consider process issues in CBT

As well as conceptualising the maintenance of client problems as inhibited or ineffective learning, and the remediation of problems as more adaptive learning, the model can be used to represent more general reflective processes and the overall course of CBT. Treatment consists of a cycle of assessment, formulation, intervention and evaluation. The ‘what’ of assessment describes the onset, course, phenomenology, context, and impact of the problem; the ‘so what’ of formulation creates a shared understanding of the relationship between factors that have influenced the aetiology and maintenance of the problem; and the ‘now what’ of interventions involves the planning, sequencing, and delivery of treatment components, combining therapeutic protocol with idiosyncratic adaptations. Evaluation of progress is a reassessment of the original ‘what’ of assessment, as in ‘what’s changed?’. The ‘so what’ of reformulation helps explain how interventions might have had an impact, leading to the ‘now what’ of further interventions, relapse management, and ultimately ending.

Caution is needed in applying the cycle too literally; assessment, formulation and intervention inform each other, and the process may move in a fluid manner. Overall, however, effective treatment will tend to follow the predicted sequence because one cannot formulate accurately without relevant information, and one ought not carry out interventions without some idea of the consequences. As treatment unfolds, new information may come to light, or a new understanding may emerge, that makes it necessary to change focus, alter one’s understanding of what constitutes the problem, and adapt strategies to take account of an evolving understanding. The experience of therapy itself contributes to learning when the accurate empathy of responsive therapists helps clients experiment by trusting that it is safe to disclose more of what deeply troubles them. At the centre of the model is the CBT therapist and their technical, conceptual, and interpersonal knowledge, skills, attitudes and beliefs. Radiating out from the person of the therapist is the skillset associated with each process: the interpersonally sensitive interviewing and information-gathering skills of assessment and evaluation; the collaborative conceptualising skills of formulation; and the technical and interpersonal skills to plan treatment and to implement interventions (Fig. 8).

Figure 8. The elements of a course of CBT as an experiential cycle.

The cloverleaf model can also be used to conceptualise the tasks of therapy associated with specific phases of treatment. If clients present in acute distress, the priority is to assess the ‘what’ of risk and coping resources, asking ‘what is the first priority?’, followed by the ‘so what’ of prioritising, as in ‘so what does this client need right now?’, followed by the ‘now what’ of action by asking ‘now what is going to be most helpful and manageable given this person’s resources?’. In the middle phase of treatment, the more entrenched, chronic and debilitating aspects of the problem tend to be addressed. Sessions often settle into a rhythm of working on medium- to long-term goals and each session tends to return to similar concerns and struggles. The client’s and therapist’s understanding increase incrementally as the cycle is repeatedly circumnavigated. This phase of work often has the quality of chipping away at some central stuck belief, concern, or ‘Big Idea’ that seems to encapsulate a whole philosophy of living. The therapist can use the cloverleaf model to remind themselves of the key questions that need to be repeatedly addressed from session to session when working towards the client’s medium- to long-term goals: what is the client’s life situation and lived reality and in what ways does it provide resources or limit their options; what is the Big Idea, belief, or way of living that is keeping the client stuck; what does that do to the quality of their lived experience and what they focus on and pay attention to; so what effect do their thinking processes have; so what do they think their experiences mean or say about them and the world; now what have they been doing and with what consequences – how realistic are their plans – do their actions take them closer to, or further from, realising their goals? (Fig. 9). In the ending phase of treatment, the focus shifts to life without the therapist’s regular input, for example asking, “what will you focus on in your life?”, and “so what will you need to do to keep an open mind?”, and “now what will you do to keep yourself well?”

Figure 9. Conceptualising the tasks of therapy associated with the middle phase of CBT.

An additional way to use the model is as a framework to identify problems related to the therapeutic process by helping to formulate obstacles to progress and challenges to the therapeutic relationship, known historically as resistance (Leahy, Reference Leahy2008). Therapy can become a frustrating experience for clients and therapists alike when each has a different idea of the form, function and content of treatment sessions. For example, it can feel disempowering to the therapist if the client seems primarily to be reporting on their experience or complaining about it with little or no insight. It can be helpful to locate the client’s verbal behaviour in the ‘what’ part of the cycle. When clients talk only of ‘what’ has happened and seem impervious to efforts to encourage them to reflect on their experience or try out another point of view, we might ask ourselves ‘what’ behaviour appears to be blocking reflection, for example changing the subject or not letting the therapist get a word in edgeways, ‘what’ appear to be the client’s preoccupations, ‘so what’ does that tell us about each of our understandings of the therapeutic tasks, goals, and our expectations of each other, ‘now what’ should we do to facilitate engagement with learning? For example, it might be that the client’s ‘Big Idea’ of CBT differs from the therapist’s conceptualisation of the respective roles of therapist and client, or perhaps the client has an external locus of control, or synthesising questions activate security operations intended to reduce anxiety (Safran, Reference Safran1984).

Another difficulty can occur when clients get stuck in endless reflection. Sometimes clients who have experience of other forms of therapy or counselling have had few concrete proposals to try out. Socialisation to CBT can help clients understand that therapy is an active process, which some find an enormous relief. Other clients seem threatened by the idea of experimenting, fearful of the consequences, perhaps preoccupied with sunk costs (Leahy, Reference Leahy2000). If speculation about what events mean, or hypothesising about the aetiology of problems, is rife, but there is little concrete evidence of movement towards change, it can help to ask ourselves, ‘what is the bigger project we’re working on here, so what makes it important, now what do we need to do?’. Finally, some clients get stuck in action phases, wanting off-the-shelf techniques to manage problems, perhaps because of emotional avoidance, or because their idea of CBT is one that is primarily technical and mechanistic. It can help to slow down and invite clients to reflect on ‘what’ they expected from CBT, ‘so what’ do they now make of the way the therapist describes and enacts it, and ‘now what’ should we do given these different perspectives?

The model might also be useful to the therapist as a way of thinking about the structure of the session and choice points within it. Based broadly on Judith Beck’s (Reference Beck2011) description of the CBT agenda, a session has three phases: check-in, focus, and check-out. In the check-in phase therapists assess the client’s current mental state and any progress (or deterioration) since the previous session, bridge to the previous session to clarify and consolidate learning, then review home practice to investigate the impact of planned activities. This is followed by a middle phase focusing on the main agenda items, followed by a final phase of planning new between-session activities and a check-out to monitor the impact of the session in terms of the client’s current state (encouraged or discouraged), its interpersonal impact (positive or negative), and any particularly salient learning. Each phase of this fluid process is a potential reflective cycle. For example, reviewing and setting home practice are each experiential learning cycles because between-session tasks create opportunities for learning. Prior to devising further home practice, it can help to ask, ‘what did we discuss that was most relevant today?’, ‘so what did you learn?’, ‘now what are you going to do?’. There are also multiple decision points during a session. While checking-in by asking information-gathering questions (‘how have you been and what have you noticed?’), there may be a temptation to ask synthesising questions (‘so what did you make of that?’) that take the session off at a tangent. Bridging involves asking ‘so what’ questions about learning, and again the temptation may be to engage with deeper reflection, rather than adding items to the agenda.

The cloverleaf model as a model of reflection for professional development

Bennett-Levy et al. (Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Chaddock, Davis, Dallos and Stedmon2009) argue that, despite the common misperception that CBT therapists do not reflect, there are many domains in which reflection is important to CBT practice and development. For example, it is an evidential requirement to write reflective summaries of learning from continuing professional development to maintain accreditation with the British Association of Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy (BABCP, 2020). Similarly, SP/SR activities are being used increasingly often to enahnce therapist proficiency. SP/SR is an experiential learning method by which CBT therapists, often during training, enhance their knowledge and skills by gaining experiential insight into the mechanisms of CBT by practising CBT techniques and formulation on themselves. As a method of teaching, it has been described as learning CBT from the inside out (Haarhoff and Thwaites, Reference Haarhoff and Thwaites2016). Having undertaken a CBT activity on themselves, practitioners are asked to reflect on their experience, often by using a model of reflective practice such as Rolfe et al.’s (Reference Rolfe, Freshwater and Jasper2001) reflexive framework, the Kolb (Reference Kolb1984) experiential learning cycle, Peters’ (Reference Peters1991) DATA model, or Gibbs’ (Reference Gibbs1988) reflective questions. Reflections on the process of SP/SR, rather than the personal content, are often shared, for example in an online community. Research has shown that there is a reciprocal relationship between the level of engagement with SP/SR activities and the extent to which benefits are reported, moderated by factors including expectations of its usefulness (Bennett-Levy and Lee, Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014).

Important though the concepts of reflection and reflective practice have become in training and professional development in CBT, Bennett-Levy et al. (Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Chaddock, Davis, Dallos and Stedmon2009) argue that the terms have been used differently by authors from different traditions. They identify four separate uses: (1) reflective practice as an approach to professional development, which Schön (Reference Schön1987) defined as ‘a dialogue of thinking and doing through which I become more skilful’ (p. 31); (2) reflection as process, which the current author defines as experiential learning based on a constructivist epistemology; (3) reflective skill, which the current author defines as a cognitive-affective process that mediates between observation and action to construct meaning; and (4) a reflective system that constitutes the cognitive apparatus by which knowledge and skills are refined. These four uses can be seen as interlinked in that reflective practice is predicated on an experiential learning process, which in turn makes use of the skills of reflection and self-reflection. These skills are themselves contingent on the functioning of the reflective system (Grimmer, Reference Grimmer2021).

In Bennett-Levy’s (Reference Bennett-Levy2006) model of the acquisition of therapist competence, the reflective system is one component of an information-processing framework consisting of three systems: the declarative system, the procedural system, and the reflective system, which are known collectively as the DPR model. The DPR model distinguishes between two types of knowledge; declarative knowledge (knowing that) which is stored in and retrieved from semantic memory, and procedural knowledge (knowing how) that constitutes a series of interpersonal perceptual capacities, self-schemas, and self-as-therapist schemas that translate into ‘when-then’ practice rules, plans, procedures and skills. The reflective system modifies knowledge and skills in the light of experience.

Useful though the original DPR model has been, it has some limitations. Firstly, it does not appear to capture fully the complexity of the human memory system. The memory system is complex, dynamic and reconstructive where episodic and perceptual memory interact dynamically with semantic, procedural and working memory (Eustache and Desgranges, Reference Eustache and Desgranges2008). Moreover, elements in semantic memory reflect the meaning of experience as constructed from a fallible autobiographical memory system that prioritises coherence over accuracy (Conway and Loveday, Reference Conway and Loveday2015). A second difficulty with the DPR model is that the concept of the reflective system seems to be fully explained by more general models of the executive functions that control cognitive and behavioural inhibition and selective attention, working memory, and cognitive flexibility (Diamond, Reference Diamond2013). Finally, information processing models of human cognition that are not sufficiently contextually sensitive struggle to explain how human meaning-making and complex behaviour patterns arise from reconstructions of experience in memory that have been determined by person-situation interactions as they play out in the social world (Mischel, Reference Mischel2004).

In contrast to the DPR model’s focus on information processing, the cloverleaf model conceptualises the person of the learner in terms of experiential learning, that is, epistemologically as someone who actively constructs meaning from experience through reflection but in a social context that influences or constrains what is known. This perspective allows us to conceptualise both client and therapist as socially situated learners where experiential learning is a form of purposeful adaptation to circumstances. As such, both client and therapist could be seen as striving to become more skilful; for the client in their personal life, for the therapist in their professional life, primarily. If similar mechanisms underpin the acquisition of personal skilfulness in CBT therapy and professional skilfulness in CBT training, then each can usefully inform the other. In a structured learning environment such as clinical supervision, Bennett-Levy et al. (Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Chaddock, Davis, Dallos and Stedmon2009) describe a reflective process of focusing attention on a problematic experience, reconstructing and observing that experience via mental representation, and performing cognitive operations on the representation in order better to conceptualise it and synthesise it with existing knowledge. In the cloverleaf model of CBT, therapists help clients describe and observe (reconstruct) experience from episodic and perceptual memory, reflect on it (relate it to semantic memory), and then make plans according to their newly arrived at understanding. CBT trainees undertake CBT-like activities on themselves in SP/SR, observe and describe (reconstruct) their episodic and perceptual memories in written reflections, in which they also reflect on the meaning of the experience and any learning as it applies to the practice of CBT, with implications for future action. Both client and therapist become more skilful by learning through reflection on doing as they challenge unhelpful or contextually maladaptive beliefs and develop and practise new skills, including the skill of reflection. Skilfulness facilitates the capacity to live more rewarding personal and professional lives within a social context that lends the cultural practice of psychotherapy meaning and significance.

Because the language and structure of the cloverleaf model can be used to describe the similarities between the above three activities, it might provide an accessible way for trainee and early career CBT therapists to understand the parallels between their professional reflective practice and their role in facilitating the client’s personal ‘reflective practice’. The following section gives examples of the model being used to attend to process issues, to explore therapists’ understanding of CBT, and to plan professional development activities.

Conceptualising CBT as a learning cycle that iterates repeatedly within sessions and across the course of treatment might help practitioners, particularly trainees and early career therapists, to learn to conceptualise and respond to process difficulties sensitively and effectively. For example, therapist reflection can be enhanced by helping therapists notice their own ‘Big Ideas’ of what CBT should be like, and whether there is a gap between their ‘espoused theories’ (consciously held beliefs and explanations for one’s actions) and their ‘theories-in-use’ (the mental constructs implicit in people’s actual actions) (Schön, Reference Schön1987). When feeling stuck, or a bit lost, or noticing the risk of a rupture in the therapeutic alliance, they might benefit from asking: ‘what’ is my Big Idea about how this therapy should look?, ‘what is my experience of these sessions – what thoughts and feelings do I notice?’, ‘what am I focusing on and paying attention to – the client’s experience or what my supervisor might think?’, ‘so what impact does the therapeutic setting have on the way that the tasks and goals of CBT are understood?’, ‘so what are my thinking processes at the moment – am I making unwarranted assumptions?’, ‘so what do I think the way these sessions are going says or means about the success of the therapy and me as a therapist – am I judging myself fairly?’, ‘now what do I need to do to test out these assumptions that might help move therapy forwards or give me a clearer, more accurate perspective – now what personal behavioural experiment could I try?’.

Borton (Reference Borton1970) wrote of teachers who ‘act as if part of the process were the whole – those sentimentalists who are obsessed with what they are experiencing, those cognitive demons who ask endless So whats, or the activists who confuse perpetual motion with change’ (p. 94). CBT practitioners can fall prey to similar preoccupations: some therapists might prefer to remain in the ‘what’ stage of the cycle, listening attentively, attuning themselves to the client’s concerns, validating their experience, but not asking the questions that help clients confront ideas and processes that hold them back. Some might ask endless informational questions without developing a collaborative understanding of the function of beliefs and behaviour and how they might be tested. On the other hand, therapists might risk repeatedly asking ‘so what’ synthesising questions, insensitive to how challenging it can feel to a client to keep being put on the spot, perhaps because they enjoy the intellectual stimulation of formulating, or because they are fearful of letting clients take seemingly bigger risks than they believe they are ready for. Others might prioritise ‘now what’ action over understanding without having first developed an adequate formulation to guide treatment and make sense of the outcomes of home practice. Clients might then be prescribed between-session tasks based on limited or inaccurate information and with concrete goals that are not necessarily relevant to the maintenance of client problems. Some therapists may default to previous roles that have socialised them into taking a ‘now what’ active approach to treatment based on matching a limited set of prescriptive interventions to presenting problems.

If therapists find themselves stuck in one process, it can help to use the model to identify the obstacles to exploring each domain adequately while still moving smoothly round the cycle. For example, if focused on behavioural change at the expense of exploration, are they avoiding engagement with difficult areas of the client’s experience, such as childhood trauma – ‘what do they believe that might involve and with what consequences? Do they feel out of their depth developing collaborative formulations – so what might that say about them if they struggle to make or share those connections? Do they have knowledge deficits or hold unhelpful beliefs about the content and process of CBT – now what should they do to challenge their understanding or develop their knowledge?’. It can be helpful to reassure inexperienced and uncertain therapists that CBT is a big enough idea that there is more than one way to practise it. With so much ‘what’ to learn, and so many ‘so what’ ways of understanding a client’s difficulties (and indeed our own), and a broad range of ‘now what’ interventions to practise and apply, it can, at times, feel overwhelming and de-skilling. While supervisors and trainers might appear always to know what they’re doing, developing proficiency in integrating all aspects of treatment is a lifetime’s work and we are all still experiential learners.

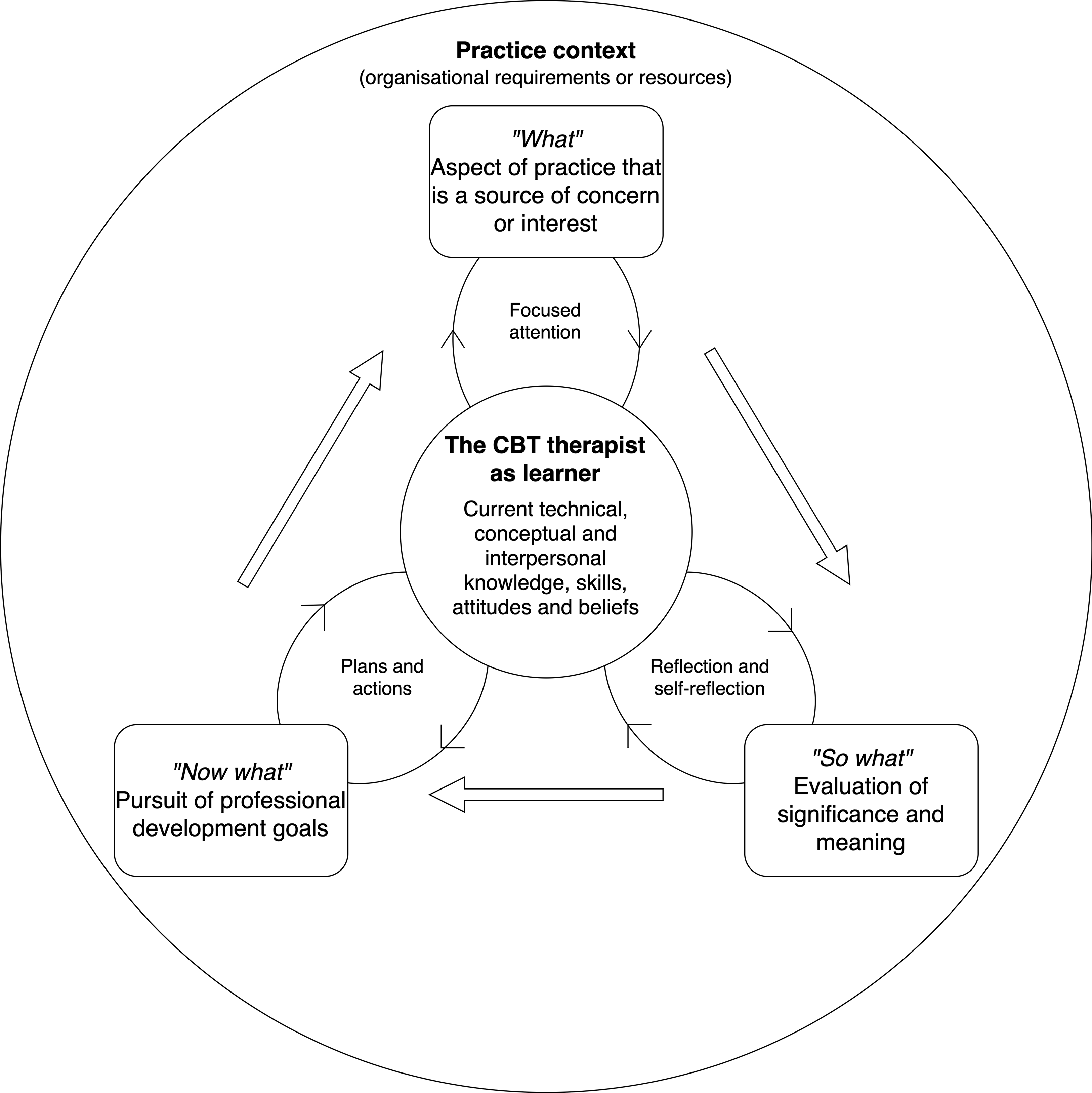

The model can also be used to investigate professional development more broadly and again link it to the idea that both therapist and client are experiential learners. In the latter case the person of the client is at the centre of the cloverleaf, in the former it is the person of the therapist, specifically the technical, conceptual, and interpersonal knowledge, skills, attitudes, and beliefs that contribute to their idea of what it means to be competent or proficient. With the goal of enhancing professional capabilities and with awareness of the current context of practice (e.g. organisational requirements or resources), therapists can focus attention on an aspect of practice that is a source of concern or interest. This can be followed by exploratory reflection on strengths, limitations, and developmental needs in this area, followed by planning and action to address those needs. Again, the same format of questioning can be used: ‘what is the area of practice I would like to address, so what makes it important, now what am I planning to do?’ (Fig. 10).

Figure 10. A reflective cycle for professional development.

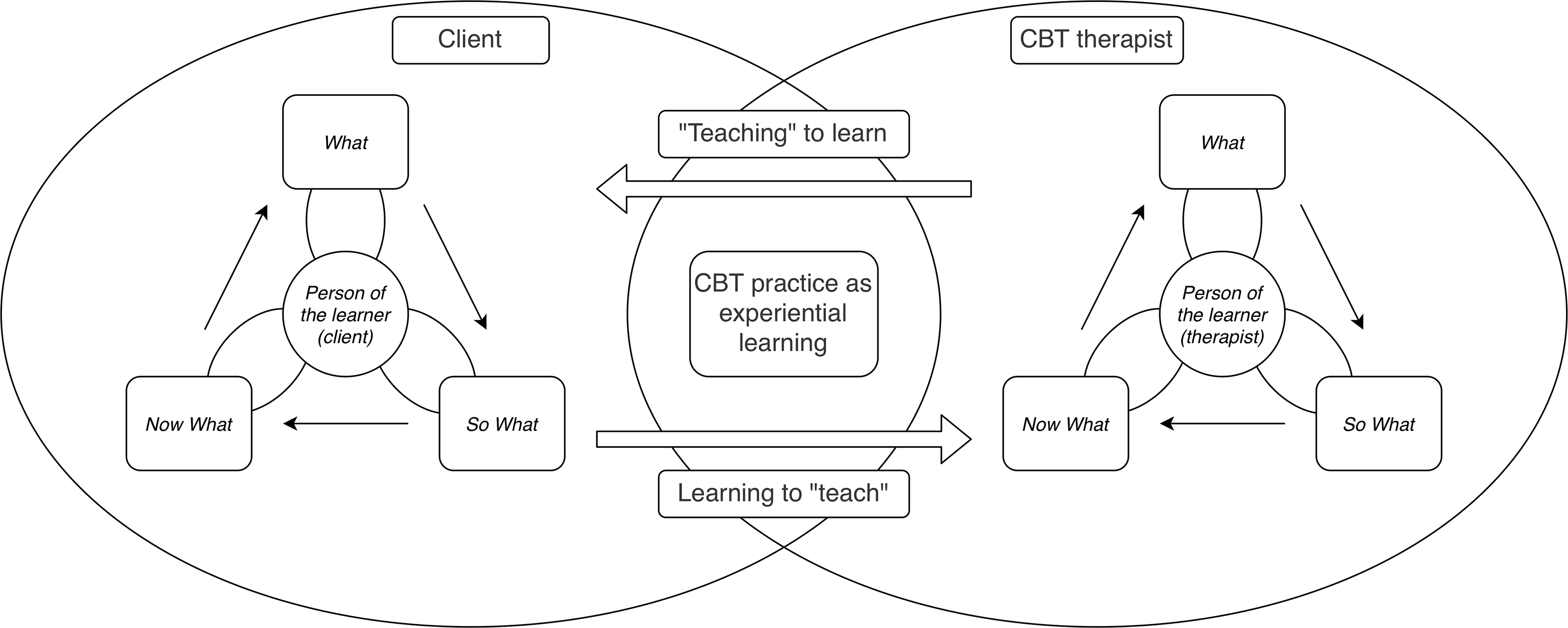

In the examples given above, using the same format of questioning in each domain of professional experience may help trainees see more clearly the learning processes that underlie CBT’s distinctive approach to psychotherapy. Routinely thinking about client process and their own learning using the same method and structure of enquiry based on a model of experiential learning might help create a reflexive conceptual bridge between the practitioner’s professional practice and development, the client’s personal growth, and the process of CBT as facilitated experiential learning. Noticing similarities between domains of learning creates an overarching model that conceptualises the CBT therapist as ‘teaching’ the client to learn, while also learning to ‘teach’ through both direct clinical experience and being in the role of the client, where ‘teaching’ is a synonym for facilitating experiential learning (Fig. 11). One consequence of this reflexive conceptualisation might be an increased empathy for the client as a learner by reflecting on one’s own struggles, confusion, and progress in learning and as a learner.

Figure 11. An overarching model of CBT as experiential learning.

Discussion

The cloverleaf model is intended to help CBT therapists formulate client problems as inhibited or ineffective learning and to show how experiencing CBT as a client, and learning to practise CBT as a therapist, can each be conceptualised as unfolding processes of facilitated experiential learning. Both client and therapist are attempting to become more skilful through monitoring what they pay attention to, enhancing their reflective thinking skills, and finding new ways of acting that create greater possibilities for enhanced life experiences. Increased skilfulness in turn is intended to lead ultimately to a more rewarding and engaged experience of life for clients, and of the practice of CBT for ourselves as mental health professionals.

The model has several potential limitations. The breadth of situations and experiences that it tries to accommodate inevitably reduces the specificity of the model, potentially losing explanatory power. It is a theoretical model and has not been tested empirically or qualitatively for its usefulness to therapists or clients. Research questions might legitimately ask, for example, to what extent it helps clients to grasp their formulation in an accessible and meaningful way that endures both through and beyond treatment. Likewise, it is not clear to what extent it is useful as a conceptual tool for therapists to use within sessions or as applied to their own development. The model might therefore be investigated in clinical and training settings to determine its helpfulness in practice. It would be useful to know whether therapists find it helps synthesise or augment existing models or creates confusion.

It is hoped that the model has at least heuristic value that cuts across multiple domains of client, therapy and therapist experience. Anecdote is not the same as valid and reliable evidence, but the (n=1) experience of the author suggests that there have been several benefits to using the model. Firstly, the model has proved extremely flexible in clinical use. The central part of the model represents the current clinical focus, the ‘Big Idea’, but while this can be a key cognition in the sense of the generic model of CBT, it does not have to be. It might be a specific problem or goal, a guiding principle or value, or a schema mode (Young et al., Reference Young, Klosko and Weishaar2003). What has proved useful is its contribution to identifying a focus for a piece of therapeutic work and then engaging the client or trainee/supervisee in a process of reflective, experiential learning that supports their development.

Secondly, it is a metacognitive model of CBT, that is, it describes processes whereby people learn about themselves as learners. Metacognition refers to a multidimensional set of skills that involve executive control, monitoring, and self-regulation such that strategies learned in one context can be applied in similar but novel contexts (Kuhn and Dean, Reference Kuhn and Dean2004). For the author, understanding progress, and especially maintaining progress, means asking ‘what kind of a learner is this person in the process of becoming?’, whether that person is a client, trainee, supervisee, or oneself. As an overarching conceptual model, it pulls together both the person of the learner and the psychological processes that underpin more-or-less effective learning. Developing and using the model has helped the author develop a higher-order understanding of the links between principles and practice in CBT.

The third benefit is the ability to use the model as part of metacompetence, which is defined as the ability to implement treatment models in a flexible but coherent manner (Roth and Pilling, Reference Roth and Pilling2007). In particular, the model has helped the author to adapt formulations, to work collaboratively with potentially counter-therapeutic client behaviours, and to identify their own unhelpful cognitions. The ‘what, so what, now what’ formula is easy to remember and provides a touchstone for practice in clinical sessions, supervision, and training. Fourthly, in the author’s experience, trainees tend to be somewhat profligate with their use of arrows to connect areas of content when they first create diagrams of formulations. The cloverleaf model might help make clearer and more explicit the psychological process that an arrow represents. Finally, the model’s focus on enduring learning aligns with the author’s personal and practice philosophy of the importance to wellbeing of lifelong learning within a lifespan developmental context. This perspective is consistent with the keep learning element of the five ways to wellbeing model (Aked et al., Reference Aked, Marks, Cordon and Thompson2008), which we might usefully remember to apply equally to ourselves as practitioners and to our clients.

Key practice points

-

(1) When formulating client difficulties, consider using the blank cloverleaf model to explore collaboratively both the maintenance of problems and a vision of wellbeing. Draw out each model separately and compare.

-

(2) When using guided discovery, bear in mind which process you are elaborating – the ‘what’ of describing lived experience, the ‘so what’ of reflection and self-reflection, or the ‘now what’ of intentional action in the service of adaptation. Negotiate moving from one to the other in collaboration with your client.

-

(3) When reflecting on CBT process, including challenges in the therapeutic relationship, consider using the cloverleaf model to formulate and explore both the client’s process (the part of the cycle in which they are stuck) and the CBT practitioner’s beliefs and actions (the parts of the process we favour).

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Ann Hislop for her helpful comments on an earlier draft and the three anonymous reviewers for their detailed and constructive suggestions.

Author contribution

Andrew Grimmer: Conceptualization (lead), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing (lead).

Financial support

This author of this paper received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

The author declares none.

Ethical statement

The author has abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS.

Data availability statement

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.