The policy of community care for people with mental illness has led to an improved quality of life for many, but there has been growing concern about its limitations and the impact that these are having on patients, their families and the general public. For patients, its defects are apparent most starkly in the high suicide rate of approximately 1000 per year among those recently in contact with mental health services (Reference ApplebyAppleby, 1997). For the general public, the defects of community care are portrayed most vividly in the homicides committed by people with mental disorders: on average, 40 per year (Reference Taylor and GunnTaylor & Gunn, 1999). Recently, there have been major policy and practice shifts, with an increasing emphasis on using coercion and targeting services on those who are assessed as dangerous. This policy has been heavily criticised by mental health professionals, who have argued that violent patients form a very small sub-section and efforts would be better directed at improving care for all (Reference EastmanEastman, 1997; Reference LeffLeff, 1997; Reference Taylor and GunnTaylor & Gunn, 1999).

METHOD

The study reported in this paper examined the public inquiries held after homicides because they have had a major influence on both public opinion and government policy. A few, well-publicised inquiries were held in the 1980s but the majority have been conducted since 1994 when the Department of Health decided that ‘in cases of homicide, it will always be necessary to hold an inquiry that is independent of the providers involved’ (NHS Executive, 1994). These inquiries examine the quality of care that the patients received, to see what lessons can be learned about reducing the future risk of violence. Each looks at a particular tragedy, but the set of reports needs to be studied as a whole to identify recurrent failings or lessons.

The media attention given to these reports has helped to make violence a central issue in policy debates, but our study questioned to what extent the detailed findings of these inquiries support the current changes in policy. In particular, the analysis focused on the findings relating to whether the homicides were deemed to have been either predictable or preventable and what recommendations were made on reducing violence.

Analysis was made of the findings of the inquiries into homicides by mentally disordered offenders in Britain. Because no official list of inquiries existed, we used information supplied by the Zito Trust, who have been trying to keep a comprehensive record. The sample comprised all reports published between 1988 and 1997: a total of 40 reports. One other report was identified but efforts to obtain a copy were unsuccessful. Only five of these reports were published before 1994 when there was a sharp increase because inquiries after homicides became mandatory to ‘protect the public and patients’ (NHS Executive, 1994). A large number of inquiries set up since 1994 had still failed to publish a report by 1997, hence our total sample was far lower than the number of homicides by mentally disordered offenders during that period.

As recommended in the guidance from the NHS Executive (1994), all the inquiries examined the following topics:

-

(a) the care that the patient was receiving at the time of the incident;

-

(b) the suitability of that care in view of the patient's history and assessed health and social needs;

-

(c) the extent to which that care corresponded with statutory obligations, relevant guidance from the Department of Health and local operational policies;

-

(d) the exercise of professional judgement;

-

(e) the adequacy of the care plan and its monitoring by the keyworker.

The inquiry panels varied in the balance of professionals represented, particularly between psychiatry and law. The reports also varied in length and detail and, it might be argued, in quality. However, this study did not re-examine the evidence or criticise the conclusions, but analysed the published findings because it is these, however fallible, that have been influencing policy makers. Analysis was made of the judgements about whether the homicides had been predictable and/or preventable. Inquiries generally made a clear statement about the predictability of the violence. For example, “ the inquiry records that there was no evidence to indicate that Mr B was a risk to persons other than himself” (Reference Chapman, Ashman and OyebodeChapman et al, 1996) or “this relapse was predictable, as was the increased risk of violence that accompanied it” (Reference Crawford, Devaux and FerrisCrawford et al, 1997).

Most reports also made a judgement about whether the homicide could have been avoided. This included most of the cases where the violence could have been predicted but also some cases where the inquiries concluded that, although the violence was unpredictable, the professionals could have predicted that the patient would become ill again and that if he or she had received a reasonable standard of treatment the homicide would have been prevented. For instance, “we are sympathetic to the fact that Kenneth Grey killing his mother could not be predicted but are convinced that steps could have been taken which might have prevented it from happening” (Reference Mishcon, Dick and WelchMishcon et al, 1995). Reports where the homicide was not judged preventable fell into two categories: those where there was a judgement that they were not preventable and those where there was no clear comment on the matter. For the purpose of our analysis, where the focus was on those considered preventable, these were grouped together and were classified as ‘not judged preventable’.

In analysing predictions of risk, attention was also paid to whether the predictive factors were long-standing or recent, because this has relevance for case management. Any risk assessment is related to a particular point in time and patients' ratings will vary over time. So a patient who is classified as very dangerous at one time may, after treatment or changes in his or her environment, be considered a much lower risk. In examining the statements about the predictability of the violence in the reports, there were clear differences in the patients' histories: some had a fluctuating history in which there had been episodes when they were considered high risk; others had never caused significant concern on this point until immediately before the homicide was committed; and some patients had never given any indication that they might be violent, even immediately prior to the homicide. Christopher Clunis, for instance (Reference Ritchie, Dick and LinghamRitchie et al, 1994), clearly fitted the first category, with a history of violence and a relapsing illness, whereas Philip McFadden had never been assessed as dangerous in the past but displayed acute indicators of violence in the days preceding the homicide (Reference Aronson and DyerAronson & Dyer, 1995). James Stemp, on the other hand, is an example of the third category. He, at no time, presented “as someone who posed a significant risk either to himself or to others” (Reference Adams, Douglas and McIntegartAdams et al, 1997).

In our analysis, we classified a history of violence or high-risk assessments as ‘long-term’ indicators of violence, and the signs and symptoms displayed immediately prior to the violence as ‘imminent’ indicators.

We used the inquiry panel's judgement of whether the patient displayed long-term and/or imminent indicators of violence. This usually coincided with the judgement of professionals involved in the case, but if there was any disagreement it was in that inquiries found more risk indicators.

A characteristic of risk assessments is that they involve estimating a probability — a degree of risk. Patients are not classified into two distinct categories of safe and dangerous. A patient who has been extremely violent may never be classified as a zero risk but may be considered safe enough to be released into the community. The Sinclair Report (Reference Lingham, Candy and BrayLingham et al, 1996) uses the graphic image of a ‘ladder of dangerousness’ up and down which a patient may move. So, when, in our analysis, a report is classified as having concluded that the homicide was predictable, it means that the inquiry panel thought that the probability of violence, at that time, was high enough to warrant action by professionals to try to avert it.

FINDINGS

Predictability of homicide

Eleven inquiries (27.5%) concluded that the violence could have been predicted and 29 (72.5%) considered that there had been insufficient evidence to alert professionals (see Fig. 1). Twenty-four (60%) of the patients had a history of violence or high-risk factors for violence but in only eight did the inquiries consider that there was evidence for judging them to be high risk at the time of the homicide. Sixteen patients who had long-term indicators of violence did not show any imminent signs to indicate that their state of mind was changing significantly.

Fig. 1 Predictability.

In three of the cases that were considered predictable, the patients had shown signs and symptoms indicative of risk only in the days preceding the homicide. Until that point, there had been no serious concern about their dangerousness in their history. Thirteen patients showed neither long-term nor imminent indicators of risk.

Preventability of the homicide

Twenty-six cases (65%) were considered to have been preventable (see Fig. 2). This included nine of the 11 cases deemed to have been predictable. In the other two cases considered predictable, the high risk of violence had, in fact, been recognised. In one case (Reference Richardson, Chiswick and NuttingRichardson et al, 1997), the inquiry agreed with the professionals that they had no legal power to intervene because the patient did not have a mental disorder that made him detainable under the Mental Health Act. In the other case (Reference Aronson and DyerAronson & Dyer, 1995), police were sent to the house to take the patient to hospital and he killed one of them.

Fig. 2 Preventability. [UNK]=Violence predictable [UNK] Violence=not preventable.

There was, however, a large group of seventeen cases where inquiries concluded that the homicides had been preventable, but this was not through better risk assessment but through a better level of psychiatric care in general. The violence itself was not predictable but a relapse could have been and, with a reasonable standard of care, should have been predicted so that the patient would not have been in the community in such a disordered state at the time of the homicide. The Norman Dunn inquiry report provides a classic example of this category:

“Two questions arise. The first is — could anyone have foreseen that Norman would have been so violent that he caused his mother to die? The answer, the Inquiry is quite certain, must be no, never. The second, however, is — could this tragedy have been prevented? The answer, the Inquiry is equally certain, must be yes, most definitely. Those who were professionally responsible and directly concerned in the case of Norman in the community had not noticed the deterioration observed by others. Had they done so, there is little doubt that he would have been admitted to hospital and the symptoms of his illness corrected. Norman would have been spared the further deterioration that occurred, his symptoms would have been more easily resolved, his family would have been spared the burden of coping with him in his ill state, and the attack on Mrs M would never have occurred.” (Reference Keating, Collins and WalmsleyKeating et al, 1997)

Correlating preventability with patient history, 16 (66%) cases of those with long-term indicators and nine (56%) of those with no long-term factors were judged preventable homicides.

DISCUSSION

These findings suggest that more homicides could be prevented by improving the response to patients who start to relapse, regardless of their assessed potential for violence, than by trying to identify high-risk patients and target resources on them. According to the inquiries, improved risk assessment would have identified 11 of the 40 cases and the homicides could have been prevented in only nine of them. Seventeen other deaths could have been prevented if professionals had responded more efficiently to signs that the patients were relapsing, although they gave no clear signs that their illness would include violent behaviour on this occasion.

Concern for public safety has been taking political precedence over concern for the welfare of those suffering from mental disorders. With this priority, it might seem, at first glance, plausible to argue that at a time of limited resources it is best to focus them on those patients posing the greatest threat to the public. But these findings show that: those showing long-term signs of dangerousness are only a subsection of those who are violent; even those fitting this category do not always show imminent signs that they are about to be violent; and there are a substantial group of people who display none of the accepted indicators of violence before committing homicide.

IMPROVING RISK ASSESSMENT

It might be argued that the solution lies in improving our ability to assess risk. This, however, is unlikely to lead to substantial increased safety for the public. The finding that only 27.5% of the homicides were predictable is not surprising in the light of other evidence about professionals' ability to predict the rare incidents of violence. Existing risk assessment instruments have low accuracy. Menzies et al (Reference Menzies, Webster and McMain1994) evaluated the predictive validity of two rating scales with disappointing results, leading them to conclude: “the objective of a standardized, reliable, generalizable set of criteria for dangerous predictions, in law and in mental health, is still an elusive and distant objective”.

Further empirical research on indicators of risk may help to improve predictive skills, for example, the large-scale MacArthur Risk Assessment Study now being conducted in the USA is studying the association between risk factors and violent behaviour and aims to improve the validity of clinical risk assessment (Reference Steadman, Monahan and AppelbaumSteadman et al, 1996). However, improving accuracy is difficult and it is unrealistic to expect risk assessments to achieve high accuracy.

Empirical studies to improve the knowledge base face methodological difficulties, summarised by Monahan & Steadman (Reference Monahan and Steadman1996):

“Four methodological problems have especially plagued actuarial research on the assessment of the potential of the mentally disordered for violence: inadequacy of cues or factors chosen to forecast whether violence will occur, inability to determine the extent of violence within the population studied, limited applicability of research designs used to validate risk factors, and failure to coordinate research efforts in the field.” (Reference Monahan and SteadmanMonahan & Steadman, 1996)

The MacArthur Risk Assessment Study is designed to minimise these problems but, although its findings may improve knowledge of risk factors, it is unlikely to lead to highly accurate risk predictions because homicides are so rare. The statistics of predicting relatively rare events, such as violence in those with mental disorders, mean that it is extremely difficult to achieve a predictive system with high accuracy. Even a test with high sensitivity and specificity will produce a high number of false positives (Reference Campbell and MachinCampbell & Machin, 1990; Reference MunroMunro, 1999).

ETHICAL PROBLEMS

The fallibility of risk assessments has ethical as well as clinical implications. A false positive may lead to a non-violent patient being detained, whereas a false negative may deprive someone of needed help. When professionals failed to assess Christopher Clunis' potential for violence accurately, both he and his victim suffered an injustice, Jonathan Zito in being killed and Christopher Clunis in not being given the care and treatment he so needed. When decisions have to be made in conditions of uncertainty, policy-makers have to decide on the relative importance of false positives and false negatives (Reference HammondHammond, 1996).

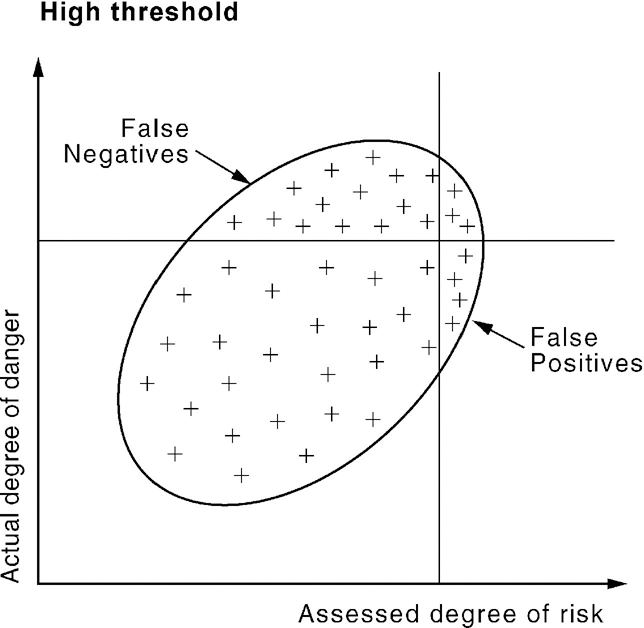

The threshold for professional intervention will vary according to the acceptability of each type of error. The Taylor—Russell diagram (Reference Taylor and RussellTaylor & Russell, 1939) helps to illustrate this. The two axes measure the true degree of danger and the professional assessment of risk. If risk assessment were a perfect science, we would expect cases to fall in a straight line, with real and identified risk being the same (Fig. 3). However, because we only have fallible measures, cases will fall in an ellipse (Fig. 4); the less accurate the diagnostic system, the bigger the scatter. Having estimated the probability of violence, professionals then have to make a decision about the threshold for intervention: how high should the risk be before they intervene? If we draw a line to indicate the threshold, the rate of false positives and false negatives becomes apparent. A low threshold for action produces a high rate of false positives (Fig. 5), whereas, conversely, a high threshold leads to a high number of false negatives (Fig. 6).

Fig. 3 Perfect prediction.

Fig. 4 Imperfect prediction.

Fig. 5 Low threshold.

Fig. 6 High threshold.

Decisions about the threshold for intervention are separate from estimations of the probability of a particular outcome. The issue is clearly illustrated in the two standards of proof in legal system. ‘Beyond reasonable doubt’ is a high threshold, minimising the number of innocent people who will be wrongly convicted, whereas ‘on the balance of probabilities’ is a lower threshold, reducing the number of false negatives.

In mental health work, pressure from the public and politicians to avoid false negatives (violence by people with mental disorders) is pushing the threshold for action down. This, inevitably, has the logical consequence of increasing the number of false positives: patients inaccurately assessed as dangerous. This raises ethical concerns about erosion of patients' civil liberties, especially as the trend appears to be for increasingly coercive measures both in the community and in hospitals.

At a practical level, lowering the threshold for intervention increases the total number of patients assessed as significantly high risk. In a chronically under-funded service, this has the repercussion of reducing the resources available for patients who do not fall into the category of being potentially violent. Ethical concerns can then be raised about those who are ill but are denied services because they are considered to pose no danger to the public.

BALANCING WELFARE AND SAFETY IN CHILD CARE

The dangers of trying to meet the public's unrealistic expectations of professional skill in risk assessment and management are well illustrated by Britain's child protection system (Reference MunroMunro, 1999). Here, the under-standable public concern to prevent children's deaths at the hands of their abusive parents led professionals to adopt a low threshold for intervention in order to minimise false negatives (i.e. to minimise missing children at high risk). The low threshold led to high numbers of false positives (i.e. inaccurately assessing families as dangerous). This led to a backlash against the power of professionals to intervene in family life, exemplified by the public outrage at events in Cleveland when a large number of children were removed from home on suspicion of being sexually abused.

Faced with public pressure to avoid any type of error, professionals tried to maximise their accuracy by conducting extremely thorough investigations into any allegations of abuse. This focus on investigations has had two highly undesirable outcomes. It has caused considerable distress and damage to the families, abusive or not, who are subject to them (Reference Farmer and OwenFarmer & Owen, 1995). It has also absorbed so much of the available resources that other parts of the child welfare system are suffering, even services for the children identified by the investigations as at risk (Audit Commission, 1994; Department of Health, 1995).

PUBLIC PERCEPTION OF RISK

Another argument against the current trend, in mental health services, of becoming increasingly concerned with assessing risk and targeting resources on those deemed to be at high risk of violence is that public perception of the risk of violence from people with mental disorders is greatly exaggerated. Taylor & Gunn (Reference Taylor and Gunn1999) have analysed the data on homicides between 1957 and 1995 and shown that, contrary to common myth, there has been no increase in the homicide rate since the policy of community care was implemented. They also help to put the incidence of these homicides in context. Compared with about 40 homicides by the mentally ill per year, “the public is at risk from 600-700 offences per year recorded by the police as homicide, an additional 300 killings by dangerous, drunken or drugged driving or ‘aggravated vehicle taking’ (not included in the official homicide figures) and of the order of 3500-4000 deaths per year in incidents recorded as ‘accidents’ on the roads alone” (Reference Taylor and GunnTaylor & Gunn, 1999).

Coid (Reference Coid1996) cites evidence that rates of homicide by mentally disordered people are remarkably similar in all countries, in stark contrast to overall rates of homicide, which vary dramatically. He suggests that, because Britain has a relatively low rate of homicide, those by the mentally disordered stand out more than in other countries and so receive more attention. This certainly fits with the priority given in Britain to examining each case in depth, contrasting with the USA, with a substantially higher homicide rate, where the homicides by mentally disordered receive little official study.

Mental health services have a dual commitment to maximise the welfare of patients and to protect the public from harm. The policy of community care has, for most patients, led to improved quality of life although the level of funding has meant that they have not received an optimum level of care and treatment. Treatment in the community rather than in isolated institutions has, however, made people with mental disorders more visible to the general public. Their behaviour can, at times, appear strange and frightening. They can actually be violent, usually to themselves but very occasionally to others. Their victims are usually relatives or professionals known to them, with only 13% being strangers (Reference Taylor and GunnTaylor & Gunn, 1999).

As the public inquiries show, there are serious obstacles to increasing public safety by improving risk assessment and targeting services on those deemed potentially violent. Mental health professionals have limited ability to predict rare incidents of violence. However, they have considerable skill in diagnosing and treating mental illness. The public would be better protected by having a good standard of care for all patients.

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

▪ More homicides could be prevented by good mental health care which detected relapse earlier than would be averted by attempts at better risk assessment and management.

-

▪ Risk assessments are fallible. If professionals react to public pressure by trying to avoid false negatives, they will lower the threshold for intervention, leading to an increase in false positives. This raises ethical concerns about patients who are wrongly detained or treated against their will.

-

▪ Targeting limited resources on those deemed potentially violent may lead to serious injustices to people who are seriously ill but pose no danger.

LIMITATIONS

-

▪ The study analyses inquiries' subjective judgements about predictability and preventability, which may be inaccurate. However, the findings of some of these inquiries, whatever their reliability, have been very influential in policy formation. Therefore, it is valuable to consider the total set to find out whether the influential reports are representative.

-

▪ The concept of ‘preventable’ used by inquiries makes implicit reference to the concept of ‘a reasonable standard of practice’ which needs to be clarified.

-

▪ The sample of 40 comprises only those inquiries that had been published by December 1997. Many more are in progress or have been published since then and their findings could usefully be studied.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.