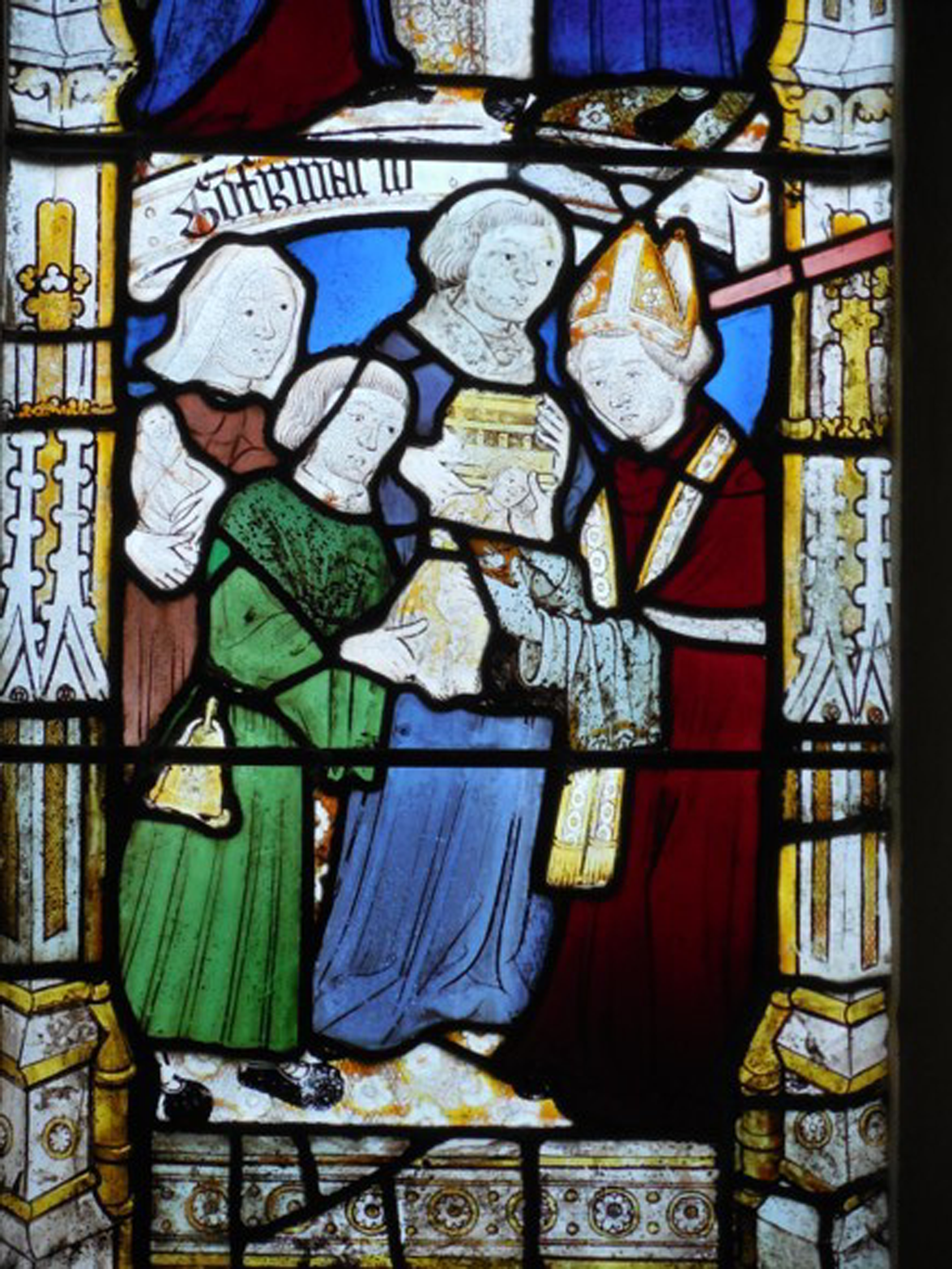

The stained-glass window in the parish church of St Michael's, Doddiscombleigh, in Devon (Figure 1) is a remarkable late medieval survival. Part of a larger scheme depicting the seven sacraments, it was installed around 1495. In this panel, we see the sacrament of confirmation. A mitred bishop is shown laying his hands upon a tiny child presented by his sponsor on the left, behind whom stands a woman cradling an infant in her arms. The cleric in the background holds a casket containing the holy oil or ‘chrism’ with which the child is anointed as part of this rite of Christian initiation, whereby the young were made full members of the Catholic Church. The bishop's thumb is clearly visible, tracing the sign of the cross on his or her forehead.

Figure 1. Panel depicting confirmation in the seven sacraments window, St Michael's parish church, Doddiscombleigh, Devon (c.1495). Reproduced by permission of the rector and churchwardens. Photograph credit: David Cook.

Two other conventional aspects of the pre-Reformation ritual are not present in the picture. One is the gentle blow on the cheek, which the bishop gave to each confirmed person as a reminder to be brave in defending the faith. This symbolic gesture was a mnemonic of the body. The second was the tying of a linen band around the child's head, which they were required to wear for three days in order to protect the sacred substance, and as a token of the fact that they had been strengthened against the assaults of the devil and the world. Many believed that it was unlucky to remove this prematurely. This part of the ritual is clearly depicted in a mid-fifteenth-century altarpiece painted for Jean Chevrot, bishop of Tournai, who is the figure administering the sacrament (Figure 2). To his right, a deacon or priest binds the head of the boy in blue who has just received it; in the foreground, three other children of various ages walk away from the scene. Their white headbands clearly indicate that they too have been blessed by the bishop.

Figure 2. Rogier van der Weyden, The Seven Sacraments (c.1448), Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp, inv. no. 393-395. Photograph credit: Dominique Provost, Collection KMSKA – Flemish Community (CC0).

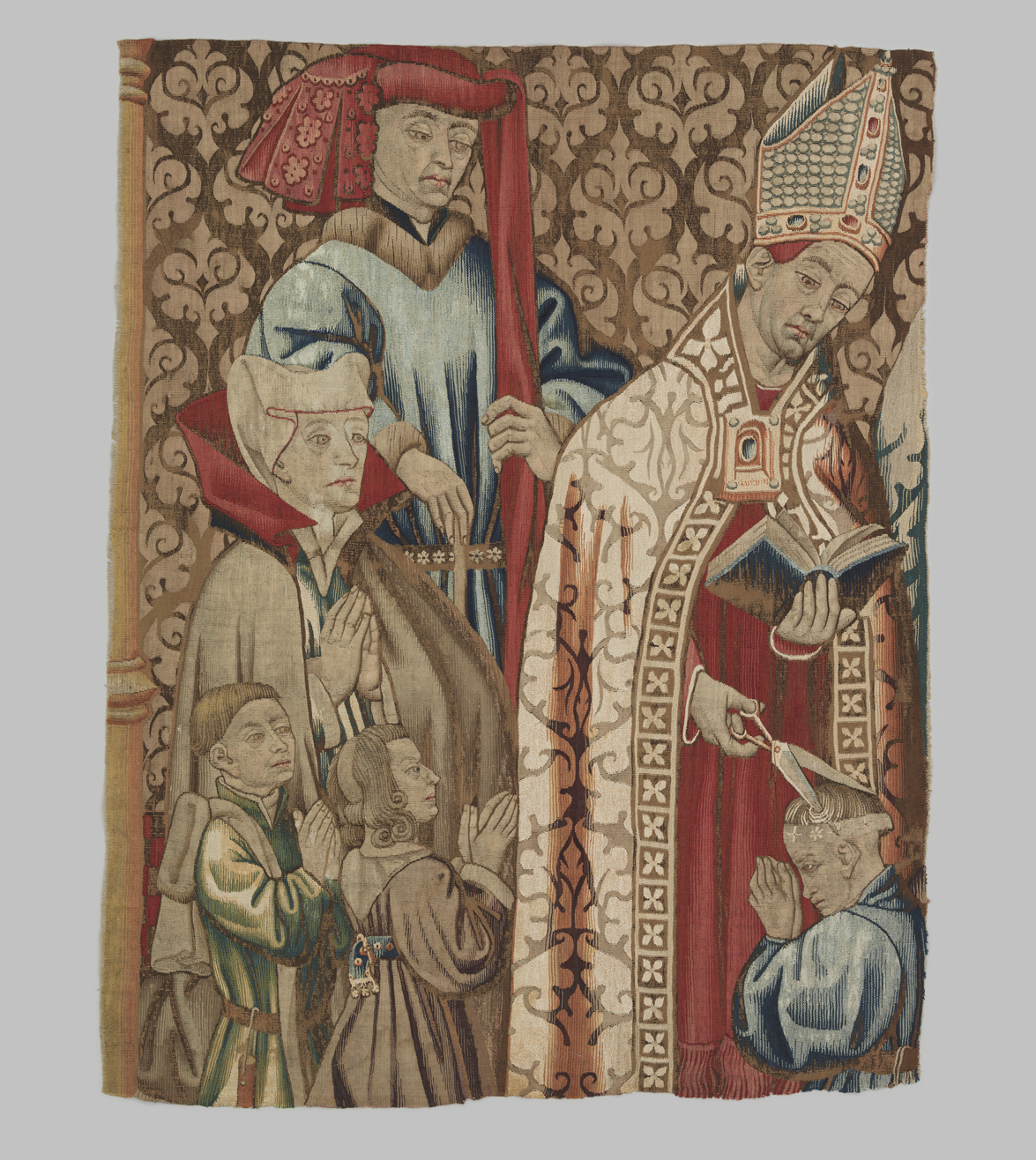

A Flemish tapestry panel dating from the 1470s, now in the Victoria and Albert Museum, captures one further element of the ritual of confirmation, or ‘chrismation’ (Figure 3). It shows the bishop using a large pair of shears to cut the hair of the child kneeling before him with his hands raised in prayer. Next to him stand two other children, whose heads have already been clipped and shaved for anointing. This is an act of holy barbering that deliberately evokes the tonsuring of those about to be ordained as priests.Footnote 1 A practice that continues for newly baptized members of the Orthodox Churches, in the medieval West it signified that the children being confirmed were entering the second stage of the spiritual life cycle. It was a religious rite of passage.

Figure 3. Tapestry panel depicting confirmation (Tournai, 1470–5), © Victoria and Albert Museum, London, T.131-1931.

The Reformation demoted confirmation from its status as one of the seven sacraments. Reduced to a mere ceremony, it had a contested existence in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England. It nevertheless survived in modified form and retained its place in the liturgy of the Church of England. Today, it usually takes place in a person's mid- to late teens. The early modern history of confirmation in England has been comparatively neglected since Canon Ollard's extensive study of it, published in an SPCK volume in 1926.Footnote 2 Susan J. Wright provided a brief treatment of the topic in an essay on the role of the young in the post-Reformation church in 1988.Footnote 3 Patrick Collinson devoted a page and a half to it in The Religion of Protestants, remarking on ‘the considerable obscurity of an important subject’.Footnote 4 David Cressy excluded it from his book on religion and the life cycle, Birth, Marriage and Death, in 1997, along with other ‘petty rituals’ which lacked the degree of ‘structure, scripting, and coherence’ that marked these major milestones.Footnote 5 There is no entry to it in the index to Judith Maltby's Prayer Book and People, while Alec Ryrie makes only incidental reference to confirmation in his evocative study on Being Protestant, suggesting that, though a source of ‘some limited controversy’, it ‘hardly registered’ in devotional life after the Reformation.Footnote 6 Recent work on the later seventeenth and eighteenth centuries is beginning to fill the lacuna in our knowledge of this rite, but it remains an overlooked aspect of religious culture in the wake of the Protestant schism.Footnote 7

This article contends that historians have underestimated confirmation's capacity to illuminate the twists and turns, tensions and frictions, within England's long and troubled Reformation. Close investigation of this rite and its various afterlives offers fresh insight into the evolution of theology, liturgy and ecclesiology in this period, within and beyond the established church and its porous outer rings. As we shall see, this is not simply a story about the origins of the entity anachronistically referred to as ‘Anglicanism’ in this era.Footnote 8 Confirmation also affords an opportunity to explore the revolution in ritual theory precipitated by the Protestant challenge and the role of formal ceremony and habitual gesture, as well as doctrine and belief, in the process of religious change. It complements Arnold Hunt's forthcoming study of the English Reformation as a movement that reconfigured social relations in and through the transformation of bodily routines and dispositions, such as bowing at the name of Jesus, using the sign of the cross, and kneeling to receive communion.Footnote 9 It is a chapter in the history of human touch.

Finally, I seek to reconstruct confirmation as a species of lived religion, through the quasi-ethnographic lens of contemporary observers of this collective public ritual. In adopting the stance of a historical anthropologist, I am conscious of the long shadow cast by Arnold van Gennep's Rites of Passage. Ranging widely across many cultures, his chapter on initiation rites treats them as a sequence of processes of separation, transition and incorporation which loosely, but never exclusively, coincides with the onset of puberty.Footnote 10 In what follows, I explore what it meant to come of age in faith in the post-Reformation period. I investigate the complex and unpredictable ways in which the biological, social and spiritual life cycles both intertwined and diverged in early modern England.

Medieval Chrismation and the Reformation of Confirmation

In the early church, baptism and confirmation were part of a single integrated ceremony of Christian initiation, which was closely followed by the administration of communion. The ritual admission of adult neophytes or catechumens to its ranks was a process orchestrated by bishops, who baptized, confirmed and administered the eucharist in rapid succession. A combination of factors led to the gradual disentangling of these elements from each other: the rising number of infants born to Christian parents and the logistical difficulties that this presented to the increasingly busy episcopal officials who presided over these rituals. Baptism was devolved to the parish priest, but chrismation was reserved to bishops as a residue of their pastoral mission to the laity, and delayed until they were able to visit to confer it upon the faithful. Simultaneously, growing emphasis on original sin fostered a tendency for baptism to occur as soon as possible after birth, lest the child perish without receiving the regenerating grace of the sacrament.Footnote 11

The interval between baptism and confirmation grew over the course of the Middle Ages. In Anglo-Saxon England, the rite became known as ‘bishopping’. It was envisaged as a process by which the candidates reached a higher level of religious maturity and, through the infusion of the Holy Spirit, became more perfect Christians, fit to participate in the holiest mystery, the eucharist. In addition to the rituals described earlier, it was not uncommon for a new name to be given to the confirmed child as a further mark of their movement into a new phase of their lives as Christian believers. As in baptism, they were presented for the rite by a godparent.Footnote 12

In the thirteenth century, church councils recommended that confirmation take place when a child was aged between one and three; by the later part of the period, seven was considered the optimal age. From Cuthbert of Lindisfarne in the seventh century to Wulfstan of Worcester in the eleventh, bishops carried this out as they toured their dioceses in the course of visitation, often in the open air, in fields and cemeteries, and on remote hillsides.Footnote 13 The thirteenth century saw greater episcopal efforts to ensure that baptized children were presented for confirmation. Concern that some reached puberty or even old age without receiving it led several bishops to prescribe punishments for negligent parents, such as fasting or exclusion from church. Overwhelmed by the sheer number requiring the rite, others employed suffragans to help them. The scale of the task remained daunting given the size of some of England's dioceses.Footnote 14 In the 1520s and 1530s, Cardinal Wolsey confirmed large crowds of children at St Oswald's Abbey in Yorkshire in two shifts, from 8 to 11 in the morning and from 1 to 4 in the afternoon, where, according to his biographer George Cavendish, he was ‘at the last constrained for weariness to sit down in a chair’. The next morning, he confirmed many more before departing for the village of Cawood. En route he dismounted from his mule to confirm some two hundred children assembled at a stone cross on a green near Ferrybridge.Footnote 15 Some – especially those of royal and aristocratic blood – were still confirmed at a much earlier age in private ceremonies. The future Elizabeth I, for instance, was baptized by Bishop Stokesley and confirmed by Archbishop Cranmer at Greyfriars Church in Greenwich on 10 September 1533, just three days after her birth on 7 September.Footnote 16

The Reformation represented a significant threat to rites such as confirmation that had no explicit foundation in Scripture. John Wycliffe had already savagely attacked it as a ‘frivolous rite’, invented ‘at the prompting of the devil’ to delude the laity; later Lollards alleged that it was ‘nother profitable ne necessarie to the salvacion of mennys sowlis’.Footnote 17 Martin Luther was equally dismissive, scorning it as a form of fraudulent juggling designed to bolster the false charisma of the episcopate.Footnote 18 Early English evangelicals such as William Tyndale and Thomas Becon denounced it as a ‘dumb ceremony’ which fostered an array of superstitious delusions, including the view that ‘if the bishop butter the child in the forehead’ it would be safe from all spiritual peril. The notion that unloosing the cloth tied around their head or neck was a recipe for trouble was no more than a silly taboo. Such ‘reliques of Rome’ were rooted in fake decretals.Footnote 19 John Calvin was even more vehement, declaring that this ‘abortive mask of a sacrament’ was ‘one of the most deadly wiles of Satan’. He scorned the opinion that, until children were ‘besmeared’ by the ‘rotten oil’ that was chrism, they were only ‘half Christians’. These were ‘nothing but theatrical gesticulations, and rather the wanton sporting of apes without any skill in imitation’.Footnote 20 According to the staunchly Calvinist early Elizabethan archdeacon of Colchester, James Calfhill, this ritual had no efficacy ‘unless’, he wrote sarcastically, ‘they have shut the Holy Ghost in their grease pot’.Footnote 21

In short, in the eyes of the reformers, confirmation was not a true sacrament. Its removal restored baptism to its proper place as a sign of God's everlasting promise to the seed of Abraham and their reception into the congregation of Christ's flock. The wider reconceptualization of the very meaning of ritual that the Reformation inaugurated – from a mechanism for creating a holy presence, to an outward representation of a divine decision or event – also emptied it of sacred significance. At best, it fell into the category of things indifferent or adiaphora, the use of which was constrained by the rules of Christian edification and by the danger of scandalizing weaker brethren. Tainted by association with popish idolatry, it ran the risk of nurturing attachment to past error and impeding the advance of the gospel.Footnote 22

Yet Protestants were obliged to admit that one component of the rite did have scriptural precedents. Jacob's blessing of Joseph's children in the Old Testament (Genesis 48: 9–22) prefigured a powerful passage in the New: the Apostles laying their hands upon new believers so that they might receive the Holy Spirit (Acts 8: 17), as the conduits of a kind of personal Pentecost. Accordingly, while fiercely criticizing the adulterated form into which confirmation had degenerated during the Middle Ages, the reformers yearned to revive the practice in what they imagined to be its primitive purity. Calvin did not ‘mislike’ the ancient custom of bringing young children to attest their religious knowledge and make a profession of lively faith when they came to years of discretion, noting that the imposition of hands had no supernatural power in and of itself, but simply invested the process with greater solemnity and reverence.Footnote 23 An order for confirmation drawn up in Strasbourg in 1550 reflects the influence of Martin Bucer, who encouraged adolescents to make a conscious act of voluntary submission to their religion, in order to combat the anabaptist charge that children baptized in infancy were too young to understand the vows made on their behalf.Footnote 24 Bucer's arrival in England the previous year coincided with the first edition of the Book of Common Prayer. This incorporated a translated and modified version of the Sarum office, which dropped the anointing with oil and the linen band, but retained the sign of the cross and the laying on of hands ‘after the example of thy holy Apostles … to certify them (by this signe) of thy favour and gracious goodnes toward them’. The revised liturgy of 1552 quietly dropped the offensive sign of the cross, setting the standard for the Elizabethan Prayer Book of 1559.Footnote 25

Critically, the rite for confirmation was prefaced by a short catechism, which the child was to digest and internalize. Having done so, they would also be able to recite the Lord's Prayer, the Apostles’ Creed and the Ten Commandments in their mother tongue, imploring God in his mercy to ‘kepe us from al sinne and wickedness, and from our gostly enemy, and from everlastyng death’. The rubric instructed that confirmation was to be administered to ‘them that be of perfecte age’ and mature enough to comprehend the core beliefs of their faith. It concluded ‘No manne shall thynke that anye detrimente shall come to children by differryng [i.e. deferring] of theyr confirmacion’ until they had reached this stage. If they died in infancy, but had been baptized, Scripture provided assurance that they were ‘undoubtedly saved’.Footnote 26 The rite discharged their godparents from the responsibility of ensuring the child's religious education and laid it upon the shoulders of the young themselves. As Keith Thomas remarked, the Reformation had the effect of raising the age of religious adulthood, though this was understood less as a numerical gauge than a sliding scale dependent upon the intellectual capacity and spiritual attainment of the individual in question.Footnote 27 In the process it became aligned with biological puberty rather than the earlier years of childhood, that is, with a time when by ‘the frailtye of theyr awne fleshe’ and the temptations of Satan they were liable to lapse into sin.Footnote 28

The close connection between confirmation and catechizing turned the rite into a kind of graduation exercise, as well as an entrance test for admission to holy communion, at least theoretically (Figure 4). Catechisms for ‘children in years and in understanding’ prepared by godly ministers index the disillusionment that set in as the Reformation moved from its illicit protest phase to the status of an institutionalized church, and as the laity failed to display the requisite zeal. They reflect the perception that many needed remedial instruction to bring them up to speed. The ‘babes’ for which these ministers prepared nourishing ‘milk’ were older adults as well as young people.Footnote 29 Directed towards parents and heads of households, these catechisms were part of a campaign for religious education that was seen as key to nurturing the next generation of Protestants: those who had been born into the true church rather than chosen to convert to it. If they encapsulated the conviction that rote learning and memorization of the Prayer Book catechism was insufficient to make real Christians, they themselves were instruments of the same process of confessionalization.Footnote 30 The rite of confirmation had become the formal endpoint of a process of indoctrination, which the godly regarded as a hollow and unsatisfactory substitute for feeling the workings of the Holy Spirit within one.

Figure 4. Minister or layman catechizing children: woodcut in John Day, A booke of Christian prayers (London, 1578), p. 46 (sig. Niir), Cambridge University Library, shelfmark SSS.24.13. Reproduced by permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

Those on the more radical left wing of the Reformation movement remained squeamish about confirmation for these and other reasons. In Edwardian Worcester, Bishop John Hooper refused to carry it out, and it was likewise a sticking point for some of the Marian exiles in Frankfurt in the ‘troubles’ that erupted among English brethren in the mid-1550s.Footnote 31 In puritan circles, it continued to be the target of vicious polemic, not least because of its umbilical link with the disputed institution of episcopacy. The ‘bishopping of baptized children’ was regularly included in the roll call of ‘stinking’ customs and ceremonies which the Romanists had allegedly devised to bedazzle their followers: ‘anoynting, annoyling, absolving, kneeling, knocking, whipping, crouching, kissing, crossing, shaving, greasing, and ten thousand such tri[n]ckets mo[r]e’.Footnote 32 The abrogation of those ceremonies that had been retained within the liturgy of the Elizabethan church remained a priority for the hotter sort of Protestants. The Admonition to Parliament of 1572 described confirmation as ‘popish and pevish’ and the presbyterian leader Thomas Cartwright complained that the imposition of hands by the bishop led country people to go to considerable expense and unnecessary inconvenience in travelling half a score miles or more to obtain this false blessing for their offspring.Footnote 33 A bare ordinance of man, at best it was a superfluous appendix; at worst it led many to doubt the all-sufficiency of baptism.Footnote 34 Never one to mince words, the puritan Anthony Gilby regarded it as a remnant of the ‘olde beaste’, one of the ‘filthy dregges’ that turned the church from the ‘chast spowse of Christ’ into a ‘romish harlot’.Footnote 35 Henry Barrow and the Brownists listed it among other Antichristian ‘abominations’ and ‘trumperies’ that justified their schismatic separation from the Church of England.Footnote 36 At the Easter quarter sessions in Devizes in 1588, the Wiltshire villager Thomas Baslyn, presented for having had his daughter baptized privately at home, declared that the confirmation of children was an unwritten tradition that lacked biblical sanction, like the ‘Juysh cerymonie’ of the churching of women.Footnote 37 Some editions of the Geneva Bible were bound with bowdlerized versions of the Prayer Book that omitted these contested rites to cater for the tastes and accommodate the scruples of England's self-styled godly people.Footnote 38

The Revival of Confirmation

Enquiries about confirmation were not a prominent feature of visitation articles in the Elizabethan period.Footnote 39 John Whitgift's letter to his fellow bishops in 1591 urging the renewal of this ‘auntient and laudable ceremonie’ bears out suggestions that it had been generally neglected in the preceding decades. Whitgift was eager to resurrect it as a strategy for remedying the ‘dissolute’ manners of the youth of the realm, who through ‘the negligence both of natural and spiritual fathers, are not (as were meete) trayned up in the chiefe and neacessarye principells of Christian religion … especially in their tender yeres’. Encouraging bishops to perform it not merely during their visitations but ‘also at other fit opportunities’, Whitgift followed in the footsteps of those Calvinists for whom confirmation, preceded by diligent catechizing, was a tool for fostering the spiritual edification of the young.Footnote 40 But his enthusiasm for it must also be understood in the context of the positive apology for the rite that he was obliged to mount in answer to its hotter sort of Protestant critics. This was elevated to another level by Richard Hooker in Book 5 of his Lawes of Ecclesiasticall Politie published in 1597, in which he accused puritans of ‘sponging out’ a good Christian custom and insisted that the ceremony now practised was not only free from popish error, but bore the imprint of a venerable patristic tradition.Footnote 41

Hooker's text was a straw in the wind of the renewed emphasis on confirmation that became a feature of what Peter Lake has called avant-garde conformity.Footnote 42 Puritan calls for its abolition in the Millenary Petition of 1603 were answered by the ecclesiastical canon of the same year that made it a requirement for bishops to carry out this ‘solemn’ and ‘holy action’, ‘continued from the apostles’ times’, in their triennial visitations.Footnote 43 Jacobean bishops were more assiduous than their predecessors in enquiring about the diligence of ministers in preparing and presenting candidates for confirmation. Bishop John Howson was particularly insistent in his articles for the diocese of Oxford in 1619.Footnote 44 A sermon on Acts 8: 17 preached by his chaplain, Edward Boughen, strongly enjoined its use as a means of strengthening Christians to fight in the battle of life. Reflecting the influence of Arminian opinions gaining ground within the upper ranks of the Church of England, Boughen claimed that confirmation could serve to increase the believer in grace. He invoked the simile of an ‘infant newly borne’ who could not perform the part of a man ‘unlesse age and strength make the addition’, and insisted that although the miraculous powers bestowed upon the apostles at the time of Pentecost were now a thing of the past, their capacity to convey ‘the inward gifts of sanctification’ continued through the ministry of bishops in confirmation. In some sense, therefore, this rite was indeed necessary for salvation and contempt for it would ‘cut off our passage to everlasting blisse’. Boughen lashed out against Reformed churches on the Continent that had ‘pulled downe the Aristocracie of Bishops’ and ‘erected the Anarchie of a confused lay-presbyterie’ and ‘so consequently cast off the sacred use of Confirmation’. Current practice was not compromised by the abuses of the popish sacrament. Its attendant gestures were sanctioned by antiquity: even the use of the sign of the cross was left to the bishop's discretion. Boughen noted that this had been allowed in the 1549 Prayer Book and could find no evidence that it had ever been revoked.Footnote 45

Boughen's celebration of confirmation indexed two developing tendencies. The first was a growing emphasis on the elevated status of those who administered it; the second, a renewed appetite for ceremonialism and sacred gesture. Both were features of the concurrent reassertion of episcopacy north of the border in Scotland. The Perth Articles of 1618 required episcopal confirmation, alongside kneeling to receive the Lord's Supper, private baptism and communion, thereby precipitating protests that culminated in the Bishops’ Wars twenty years later. This stirred renewed debates about the significance of the imposition of hands and whether it was permissible to make use of things indifferent, or whether this should be omitted because it was ‘still abused to make up a bastard Sacrament’. Its opponents insisted that the blessing of the bishop amounted to ‘but a prophanation with his fingers’. Too often administered to children who could give no ‘serious confession of their faith’ but merely ‘utter some few words of a short catechisme like parrets’, the whole rite was a mockery of true apostolic practice.Footnote 46

The impulses behind the renewed emphasis on confirmation in some reaches of the established churches of England and Scotland came to fuller fruition in the Laudian campaign to restore the beauty of holiness in the 1630s. Leading Laudians, such as Richard Montagu and John Cosin, increasingly recast confirmation in quasi-sacramental terms, dialling down the earlier emphasis on catechetical instruction and highlighting the external actions that lent it reverence and gravity. Cosin also advocated the reanimation of elements of the medieval rite that had been discarded at the Reformation: the symbolic blow on the cheek, the sign of the cross, the anointing with chrism and the appointing of godparents.Footnote 47 The actions of the bishop's hands were reimagined as critical to the process of receiving the Holy Spirit. As James Turrell has argued, this amounted to an attempt to change ‘the official gate to church membership from knowledge to ritual’.Footnote 48 Although these reforms were never fully implemented in practice, it is perhaps telling that Bishop Robert Wright dwelt upon confirmation in his visitation articles for Bristol in 1631, which also asked about unlawful conventicles, private fasts and ‘impugners’ of innocent rites and ceremonies.Footnote 49

Yet if confirmation was steadily harnessed as an arm of the conformist and Laudian agenda to reform the Church of England, its significance for the rival, evangelical strand of churchmanship that ran alongside it cannot be ignored. The overt ceremonialism of Cosin contrasts with the preoccupations of prelate-pastors eager to ensure that it was only administered to those who were properly instructed in the principles of the reformed religion. This was the gist of Thomas Ravis's enquiries about parishes in Gloucester deanery in 1605 and it also characterized the practice of Arthur Lake, bishop of Bath and Wells in the 1620s.Footnote 50 The preaching diary of Tobie Matthew, successively bishop of Durham and archbishop of York, provides a record of his diligence in this department. He confirmed thousands in the course of his visitations, laying hands on ‘many, both young and old’ at Stillingfleet in 1614. At Malton in 1607 there ‘were so many candidates, I nearly melted away with the heat, and did indeed earn the right to go to bed’.Footnote 51 Whether many of these children met the high standards of spiritual understanding idealized by Calvin and his disciples is perhaps doubtful, but Matthew's assiduous commitment to the task both reflects the compatibility of confirmation with an alternative vision of the Jacobean and Caroline Church of England and attests to the capaciousness of that institution.

The example of Joseph Hall, bishop of Exeter and later Norwich, also calls into question any suggestion that confirmation became a monopoly of the Laudians, even as he illustrates its capacity to co-opt theological moderates with some priorities in common. In his visitation articles, Hall was insistent that ‘none doe offer themselves to confirmation, but such as both for yeares and instruction are fit for that institution’.Footnote 52 His book on ‘apostolicall confirmation’, Cheirothesia, published during the Interregnum in 1651, lamented the lapse of this ‘worthy practice’ and argued that its revival would be ‘infinitely advantageous’. ‘How happy it were’, he wrote, ‘if in this case, we could walke with an even foot in the mid-way betwixt Romish Superstition, and profane neglect’. He pushed back against those who ‘cryed down’ and ‘hooted at’ it as an odious remnant of popery. But he was equally determined to strip it of the various ‘fopperies’ that had been added to the ‘plaine and holie dresse’ it had worn in the primitive era: ‘clapping on the cheek, the crosse of the thumb, treading on the toe, filleting the forehead for seven days, and the like’, which were ‘no lesse vaine then new’ and served ‘onely to confirme us in the lightnesse and indiscretion of their founders’. If this ‘trash’ was removed, confirmation still had value and utility, provided the children to whom it was administered went beyond a mere ‘verball learning’ of the articles of their religion. In retaining it, the Church of England was ‘more eminent in this point then her other sisters’. Greater fidelity in carrying it out, he alleged, would have ‘prevented many foul and monstrous exorbitances in matter of Doctrine’ and the ‘many horrible enormities’, ‘woefull distractions’ and ‘Paradoxes of contradiction’ with which the commonwealth was ‘now miserably pestred and over-run’. Quoting Hooker, he said that it would foster true godliness in young children, preserve the seed of the church of God, maintain the unity of the faith, and exclude the ignorant and scandalous from the ‘sacred Ordinance’ of the Lord's Supper.Footnote 53 Hall wrote as if the Church of England had not been disestablished, and his treatise gave expression to the self-conscious identity that was being forged in the crucible of its sufferings as a beleaguered minority. Henry Hammond, the Royalist archdeacon of Chichester and canon of Christ Church in Oxford, was another champion of this ancient Christian custom. His learned Latin tract on the topic, composed during these dark years, appeared posthumously in 1661.Footnote 54

These examples encourage us to avoid boxing confirmation into the overly rigid ecclesiastical taxonomies that have bedevilled our understanding of English Protestantism in the first half of the seventeenth century. They encourage us to avoid seeing it simply as a strand of what later became known as ‘Anglicanism’, and to recognize the coexistence of several overlapping strands of feeling about ‘bishopping’ in the post-Reformation era. Hall's hope that confirmation would serve as a mechanism for healing the divisions created by the events of the 1640s was shared by those who repudiated episcopacy. Presbyterians and Independents likewise perceived it as a solution to the evils unleashed by the Civil Wars. These had placed intolerable strain on the ideal of an inclusive national church and catalysed the radicalization and fragmentation of puritanism and the explosion of sectarianism. The Prayer Book rite of confirmation was a casualty of the liturgical reforms overseen by the Westminster Assembly and found no place in the Directory for Publick Worship.Footnote 55 But in the 1650s figures such as Jonathan Hanmer and Richard Baxter called for its ‘restauration’ as a means of effecting the reconciliation of the ‘disordered Societies’ of Christians that these troubling decades had brought into being. Baxter, who quoted Hammond approvingly, presented it as an effectual ‘Medicine’ to bind up these breaches and wounds, and for Hanmer too it was ‘an Expedient to promote Peace and Unity among Brethren’, whether puritan or episcopalian. Reclaiming it from the degenerate state into which it had descended in the age of Antichrist and reinstating its ‘Primitive pattern’ was essential to effecting a ‘right Reformation’. This rite of investiture was not the preserve of bishops, but, as in continental Protestant churches, an office of regular ministers and pastors.Footnote 56

One imperative for reviving confirmation was to ensure that the children of believing parents who enjoyed baptism as a birth-right made an active and public profession of the personal faith that qualified them for its higher privileges, especially access to the eucharist. If it was a ritual of inclusion and incorporation, paradoxically it was also one of exclusion and separation. Technically, confirmation had long been a qualifying condition for admission to communion in the Church of England, though in practice many communicants had not been blessed by a bishop. The version of it recommended within mid-seventeenth-century puritan circles was designed to sift out the reprobate and ensure that only the worthy received the Lord's Supper.Footnote 57

A second and related incentive was the need to ‘compleat’ church membership. Confirmation was a vital rite of transition to spiritual adulthood. What it entailed was the growth of religious infants and catechumens into mature believers and elders in faith, their evolution from what Hanmer called ‘imperfect Embryoes’ to fully fashioned organisms. This involved an inner process of regeneration: an evangelical experience of conversion or second birth whereby, in an echo of their initial christening, they cast off the old Adam and became new creatures in Christ.Footnote 58 Some dated their birthdays not from their biological, but from their spiritual nativities. The most elaborate exposition of this conception of the religious life cycle was the Congregationalist Ralph Venning's Christs School, which categorized four classes of Christians, noting how few people graduated to the highest rank of ‘fathers’. Most, even those who seemed precocious saints, were mere babes in understanding, however advanced they might be in temporal years. This was a mode of coming of age that was not necessarily tied to a particular stage of human development.Footnote 59

Once again, internal squabbles ensued regarding the form of the external ritual that accompanied the internal metamorphosis these writers delineated. Echoing Calvin, Hanmer said that if the ceremony of confirmation was ‘drained from these mixtures of humane interventions’, reduced to prayer and the laying on of hands, and administered by every pastor, it would be found to be very commendable.Footnote 60 By contrast, Francis Fulwood, minister at West Alvington in Devon, concluded that though the rite of imposition of hands could be sanctioned once stripped of formality and superstition, it was probably best omitted given that it might ‘grate upon popular prejudice’ and hinder its main objective of reconciling differences. Its superficial similarity with the format of the popish sacrament might drive away those with scruples.Footnote 61

Ironically, similar disputes erupted within the ranks of the Baptists. The puritan revival of apostolic confirmation was partly designed to answer their stinging allegation that people baptized as infants had no understanding of the Christian faith into which they were incorporated.Footnote 62 Only when men and women became adults could they be admitted to the church of Christ. The practice of laying on of hands in believers’ baptism precipitated serious schisms within and between Baptist congregations in the mid-seventeenth century. For some this savoured of the ‘popedom of Rome’; for others it was vindicated by its scriptural and apostolic precedents. Acrimonious conflicts about its validity continued to divide the movement, cutting across the boundary between the General and Particular Baptists.Footnote 63 Henry Danvers's 1674 treatise condemning it was countered the following year by Benjamin Keach's Darkness Vanquished which vigorously defended it as a divine institution. Their books rehearsed familiar arguments about whether this ceremony should be discarded as ‘an Excrement of Antichrist’ because of its connection with ‘superstitious’ and ‘popish’ ‘bishopping’ (‘as if that old-fashioned Garment had but a piece of new-nam'd Cloth put to it, and drest up in another Mode’), or acknowledged as ‘a standing or perpetual Administration’ and used after it had been restored to its pristine purity.Footnote 64 Baptist practice reintegrated baptism and confirmation into a single rite of religious passage, reversing the process that had steadily separated it over the course of the Middle Ages. Adult believers were regenerated by the water of baptism and infused with the gift of the Holy Ghost at the same time, like the early Christians whom they revered.

The Restoration of Confirmation

With the Restoration of the Church of England in 1662, the liturgical rite for confirming those who had ‘come to years of discretion’ was reinstated. In a departure from previous practice, the rubric of the revised Book of Common Prayer now insisted that individuals kneel before the bishop before he laid his hands upon each of them in turn.Footnote 65 The introduction of this bodily gesture of reverence signals the influence of Laudian sacramentalism, especially as articulated by John Cosin, as does the fact that the catechism was no longer presented as part of the liturgy for confirmation, but included in a separate section of the Prayer Book. However, the restored rite also bears the imprint of renewed puritan efforts to reform the ritual, not least in the guise of the concession at the end, that not only those who had been confirmed, but also those ‘ready and desirous’ to be, could be admitted to communion. A by-product of the Savoy Conference of 1661, at which puritan objections to the Prayer Book rite were aired and discussed, this was one small victory for the cause of comprehension. By conceding that confirmation per se was not a strict necessity for admission to the sacrament, it provided a small loophole for those who sought to evade the ritual.Footnote 66

Phillip Tovey's recent overview of Anglican Confirmation between 1662 and 1820 obviates the need for an extended exposition of its history in this period, but the resurgence of this rite of Christian initiation within the Restoration and Hanoverian Church of England must be underlined.Footnote 67 Jeremy Taylor's 1664 treatise on the topic, dedicated to James, duke of Ormonde and viceroy of Ireland, powerfully restated the case for confirmation as a ‘never ceasing ministry’ rooted in apostolic practice that bestowed graces and benefits on those that received it, as well as ‘an effective Deletery to Schism’. This was ‘the earnest of our inheritance’ and ‘the seal of our Salvation’.Footnote 68 A flurry of confirmation sermons likewise dilated on this milestone in the life cycle of faith. John Riland, archdeacon of Coventry, swapped the conventional trope of the ages of man for a botanical metaphor that compared the young Christian to a small slip or graft that, duly watered, would grow into a sturdy, fruit-bearing tree and ‘arrive to a well-rooted and Confirm'd steadiness in God's Paradise’.Footnote 69 Anticipating the van Gennepian concept of the threshold, the Leicestershire rector Benjamin Camfield described baptism as ‘the door or entrance of Christianity’, and confirmation as a further stage of initiation into the community of the faithful.Footnote 70

Others chose the texts of Acts 8: 17 and Hebrews 6: 2 about the laying on of hands for exegesis, upholding this practice as the prerogative of bishops, the ‘superior Servants’ and ‘principal Stewards’ of the Lord's household.Footnote 71 This rite of sacred touch thus helped to rebuild episcopal authority in the Restoration church, just as the royal touch augmented the restored Stuart monarchy: sacerdotalism was the handmaiden of Erastianism and aspiring absolutism, as well as reascendant episcopacy. As Stephen Brogan has shown, the tradition of charismatic healing survived the Reformation for much the same reason: trimmed of its superstitious elements, a ritual that evoked Christ's own thaumaturgic ministry of touch could not easily be completely dismissed. Touching for the king's evil or scrofula was another manifestation of the biblical practice of laying on of hands, albeit one that, with this exception, was widely said by Protestants to have ceased, along with miracles, prophecy and speaking in tongues.Footnote 72 The influence exercised by Valentine Greatrakes, the so-called ‘Stroker’, who allegedly cured thousands of men, women and children suffering from acute diseases and chronic conditions in the mid-1660s, further attests to its resilience.Footnote 73

The religious and political semiotics of bodily gesture were closely intertwined in this period. It is telling that confirmation had been regularly celebrated at the English court since the reign of James I. His children, Henry, Charles and Elizabeth, were confirmed by the dean of the Chapel Royal in splendid ceremonies. Fashionable courtiers such as the duke of Buckingham followed suit in obsequious deference to a rite that the crown evidently regarded as a crucial appendage to monarchical power.Footnote 74 In the later part of the period, the rituals associated with the divine right of kings and of bishops remained mutually reinforcing. Some nonjurors sought to restore the practice of anointing the confirmed with holy oil and making the sign of the cross on their foreheads, keen to underscore the solemnity of the occasion on which they received the gift of the Holy Spirit. They also favoured confirming infants with chrism, returning to the medieval tradition in which the symbolic rite of passage to spiritual maturity occurred soon after birth or in early childhood.Footnote 75

Once again though, confirmation was not confined to high church circles. If it offers insight into the afterlives of Laudianism, it also helps to illustrate the current of latitudinarianism that flowed alongside it. The prelate-pastor remained a familiar figure in the Church of England, committed to ensuring that this rite of religious progression was preceded by adequate instruction through catechizing and a true understanding of the baptismal vows they were about to renew. Gilbert Burnet, bishop of Salisbury, who saw confirmation as ‘the most effectual means possible for reviving Christianity’, is perhaps the best example. His practice was to catechize the children of the parish himself before admitting them. The conscientious diligence of Burnet and other bishops, documented by Norman Sykes in his Birkbeck Lectures for 1933, belies the lingering impression that the Church of England was stagnant and worldly in the eighteenth century.Footnote 76 As Robert Cornwall and Phillip Tovey have recently underlined, the picture of perfunctory performance and neglect painted by Canon Ollard requires qualification.Footnote 77 In many ways, this was the heyday of confirmation as a collective public ritual. Confirmation could be privately administered in the domestic chapels of the gentry and aristocracy, but it was also a key embodiment of Christian communitas in the early modern period.Footnote 78

Holy Fairs

In the penultimate section of this article, changing gear from ecclesiastical history to ethnographic analysis, I turn to the significance of confirmation as a social rite of passage. Most of what we know about it is mediated through the distorting lens of elite and literate observers, whether through the recollections of bishops themselves, or their biographers, or the critical reflections of hostile commentators. A repeated theme is the immense popularity of the ritual and the teeming crowds that came to receive the blessing of bishops as they visited their dioceses. Like their medieval predecessors, they sometimes administered the rite in the open air, though this may have been the exception rather than the rule. When Bishop Gervase Babington of Exeter came to Barnstaple in 1595, for instance, he was greeted by the mayor and bailiffs in their scarlet gowns and confirmed a number of boys and girls on the Castle Green. The ‘multitude’ that flocked in from the surrounding countryside on the second day of his visit was such that Babington could ‘scarce pass the street’. On an impulse, he escaped from the throng and left the town ‘forthhence’. Bewailing that they had abandoned their fields to undertake a fruitless journey to obtain confirmation for their children, the people ‘lamented that they had lost a fine harvest day’.Footnote 79 As this example reveals, confirmation was a seasonal event, confined for practical reasons – better weather and the greater passability of roads – to the late spring and summer months. It was organized around the rhythms of agricultural labour and frequently took place on market days. The atmosphere on these occasions was sometimes carnivalesque. In the West Country, Joseph Hall was struck by the ‘overeager and tumultuous affectation’ of the local people for this rite, and the ‘fervour and violence of desire’ with which they sought it out for their children. He regretted that it was not possible to administer it ‘otherwise than in a breathlesse and tumultuary way’.Footnote 80 Richard Corbet, who became bishop of Oxford in 1628, was said to have warned the country folk ‘pressing in to see the ceremony’: ‘Bear off there, or I'll confirm you with my staff’.Footnote 81 If Laudian bishops were particularly perturbed by the lack of sacred solemnity that surrounded confirmation, Presbyterians such as Baxter worried that it had become a mere charade or ‘custom’. He recalled running from school with his classmates at the age of fifteen to receive it ‘with a multitude more, who all went to it as a May-game’, lamenting the fact that none of them were properly prepared and that the bishop ‘dispatched’ them at speed and without assessing whether they were truly Christians in either inward disposition or belief.Footnote 82

One consequence of the large numbers that came to receive it was the exhaustion of the often elderly episcopate, whose aches, pains and ailments were exacerbated by the marathon sessions of confirmation in which they engaged over one or more days, sometimes working late into the evening and clocking up impressive figures in the hundreds and thousands. During the summer months of 1709, for instance, William Wake confirmed some 12,800 people, including 5,200 in Lincolnshire: beginning with 1,200 at Grantham on 7 June and ending with another 1,000 at Boston on the 28th, with visits to Lincoln Cathedral, Caister, Louth and Horncastle in between.Footnote 83 One is left with the impression of a factory production line (not to say a vaccination queue!). The issuing of tickets to candidates deemed to have qualified for the rite by receiving catechetical instruction was designed to ensure that those unprepared did not slip through, as was the requirement that they bring a certificate signed and sealed by their parish minister. But it was also a response to the disorder that not infrequently ensued. This was only partially effective: some forged the necessary documentation and others resorted to gate-crashing. John Priaulx, canon of Salisbury, worried that tickets were being given to those of ‘notorious Ignorance and Profaness’, without due attention to the level of Christian knowledge the recipients possessed.Footnote 84 Churchwardens were employed to hold back the throngs with staves and control ‘the indiscreet forwardness of parents’ who thrust forth their offspring, sometimes at too young an age.Footnote 85 A printed form dating from 1700 provided directions to ministers so that the rite might ‘be done to the more Edification, and greater Advantage of your flock’.Footnote 86 Another issued by Francis Atterbury, bishop of Rochester, said that children should be charged ‘to behave themselves decently and reverently, while it is performing’.Footnote 87 It was evidently an uphill battle to invest the ceremony with an appropriate air of decorum. Occasionally things descended into complete chaos, with young people in high spirits struggling for precedence on their way to the chancel, all the while laughing, talking, scuffling and mischief-making. Writing in 1766, William Cole, parson of Bletchley in Buckinghamshire, complained that confirmations were ‘done in such a Hurry, with such Noise & Confusion, as to seem more like a Bear ba[i]ting than any Religious Institution’.Footnote 88

Phillip Tovey speaks of confirmation as ‘part of the social package’ of being Anglican in eighteenth-century England, a form of ‘folk religion’, the theology of which is for the most part elusive.Footnote 89 It is hard to enter the mental world of those who sought and received it. But snippets of evidence are suggestive. Some, including Nicholas Ferrar, later of Little Gidding, did not scruple to seek it more than once, convinced that there could be no harm in getting a double dose. ‘By his own contrivance’, he was confirmed for a second time in 1598, when his schoolmaster presented him.Footnote 90 The bald and bearded adult men who came to be confirmed by Bishop Corbet in the early seventeenth century were probably not first-time confirmands.Footnote 91 Philip Stubs, chaplain to the bishop of Chichester, thought it a ‘pious Errour … in a great many, who thinking they can't have the Blessing of a Holy Man too often, follow the Bishop almost wheresoever he goes’.Footnote 92

In 1784, a foreign visitor noted that many people he spoke to did not think that the ritual stamped them with ‘an indelible character’. At Bury St Edmunds, he encountered three or four old women who were confirmed every time their diocesan bishop came to town. ‘Their plea is that you cannot have too much of a good thing’.Footnote 93 Such episodes highlight the tension between the clerical understanding of confirmation as a unique and unrepeatable rite of passage, and lay perception that its efficacy was not confined to a single occasion. They illustrate the frictions between formal theology and popular practice.

Some also supposed the rite to have therapeutic effects: in the nineteenth century a Norfolk woman claimed to have been ‘bishopped’ seven times because she found it helped her rheumatism.Footnote 94 Here laying on of hands is conceived of as curative. Confirmation becomes a kind of faith healing, akin to the royal touch and Greatrakes's gift of stroking. Others believed that at the moment of blessing ‘a special Angel-Guardian is appointed to keep their Souls from the assaults of the Spirits of darkness’. Jeremy Taylor thought this supposition was ‘not disagreeable to the intention of this Rite’ and did not explicitly condemn it.Footnote 95 Nor should the possibility be dismissed that some, inspired by the rhetoric of preachers, saw it as an agent of religious regeneration and perfection that enhanced their hopes of reaching heaven. Assessing these opinions against the yardstick of doctrinal ‘orthodoxy’ is unhelpful. It effaces the creative and organic character of lived religion and of rite as a human fact. The extent to which confirmation was a spiritual event for individual laypeople should not be underestimated.

However, it is also important to recognize the ways in which confirmation was combined with commensality. Bishop Gilbert Burnet of Salisbury assiduously catechized children himself prior to confirming them, presenting each candidate with a silver crown and concluding the proceedings by inviting them to a Sunday meal.Footnote 96 Food and drink flowed in the towns to which parents brought their children to be bishopped, and a mood of festivity and conviviality abounded.Footnote 97 Striking continuities with the medieval past are clear: confirmation remained a lively rite of passage. It was usually shunted forward in time from childhood to adolescence, but could happen at any point in the life cycle.

It is tempting to see confirmations as the ‘fair days’ of the Church of England, a phrase evocative of that used to describe the mass communions that took place in Presbyterian Scotland and which, imported across the Atlantic, laid the foundations for American revivalism and the Great Awakening. Leigh Eric Schmidt has provided a rich Geertzian thick description of these sacramental events in the reformed calendar, in which ‘religion and culture, communion and community, piety and sociability commingled’. Confirmations present many parallels. Occasions on which the ‘sacred and the social were inextricably combined’, they too question assumptions about the role of the Reformation in the repudiation and devaluation of ritual.Footnote 98 They supply insight into the mixture of theology, liturgy, custom, culture and emotion that surrounds the marking of rites of passage.

The Counter-Reformation of Confirmation

I cannot close without a brief discussion of the role of confirmation within the post-Reformation English Catholic community. The evangelical and Protestant assault upon this sacrament provoked resistance from the beginning. In 1549, the Prayer Book rebels in Devon and Cornwall defended traditional bishopping alongside the Latin mass and ‘all other ancient old ceremonies used heretofore by our mother the holy Church’. Following Edward VI's death, the demand for confirmation was apparently high, with people running to churches and churchyards in such numbers that there was insufficient space to hold them. Forced to confirm in the fields, the bishop of Chester feared that he would be trodden to death by the importunate crowd.Footnote 99 Bishop Bonner's visitation articles for London for 1553 reproved laypeople who refused to bring their own children for confirmation and who dissuaded others from doing so.Footnote 100 The rite in its traditional form was already becoming a litmus test of confessional identity. In its seventh session in 1547, the Council of Trent declared anathema upon heretics who dismissed confirmation as an empty ceremony, denied that it was a true sacrament that imprinted an indelible mark on the soul, denigrated chrism as blasphemous, and said that any simple priest could administer confirmation.Footnote 101 Rome's premier controversialist Robert Bellarmine buttressed Trent's declarations in ‘De Sacramento Confirmationis’, adding to confirmation's status as a shibboleth of Counter-Reformation belief.Footnote 102

Dispensing this sacrament was especially challenging for a missionary church like England's. The amputation of its episcopal hierarchy necessitated concessions and emergency measures: casuists conceded that, in these conditions, the eucharist could be ministered to the unconfirmed if this was due to a lack of bishops. They were also told that Gregory IX had granted the faculty of conferring confirmation to priests, and that the Pope could solve the problem by consecrating some of them as titular bishops, assigning them either to some English diocese or other dioceses in partibus.Footnote 103 This was precisely what happened with the appointment of William Bishop as vicar apostolic and bishop of Chalcedon in 1623, at around the same time as the revival of ceremonialism was starting to take off in the Church of England. He spent the summer after his arrival confirming Roman Catholics in the vicinity of the capital, conferring ‘Christes badge and cognisance’ upon at least two thousand people before winter set in. The Protestant polemicist John Gee mercilessly mocked this ‘puffe-paste Titulado’ to whom people flocked in large numbers: ‘what gadding, what gazing, what prostration, to receive but one drop of that sacred deaw’. Bishop's intention to visit the remote parts of the kingdom the following spring was prevented by his death less than a year later, at the age of seventy.Footnote 104 His successor, Richard Smith, published a treatise showing ‘the necessitie, spirituall profit, and excellencie of this Sacrament’ in 1629, explaining that as in ‘our corporall life, wee bee first Children, and after perfect or compleate men’, so in spiritual life did people proceed from being like newborn infants to children, and from thence to fully-grown men. Failure to be confirmed was a mortal sin. Turning the devout believer into ‘a Souldier of Christ’, this sacrament was a shield to resist Rome's enemies in ‘time of persecution’. It was ‘temeritie to enter into a daungerous Combat without Armour’. In describing the different parts of the ritual, he said that the stroke on the cheek was to admonish the confirmed party of his obligation ‘to beare blowes if neede bee for the profession of Christs faith’.Footnote 105 Confirmation thus became an emblem of the tribulations Roman Catholics suffered and of the resilience and militancy of the English Counter-Reformation.

This experiment in instituting a Tridentine episcopate in England was short-lived, but in the later seventeenth century it acquired a second wind under the Roman Catholic monarch James II. It is significant that in 1686 Henry Hills, printer to the king's chapel and household, issued a short catechism and account of the holy sacrament of confirmation. This too stressed its status as a kind of sword and buckler for those in the midst of trials and tribulations. It explained that the sign of the cross was designed ‘to teach us that we never ought to be asham'd to confess Christ crucifi'd’, and that the little slap on the face was ‘to shew that we ought to be ever ready to suffer all Affronts and Injuries from Men’ without quailing, even to the extent of dying for the sake of Christ.Footnote 106 Roman Catholics were given permission for the public exercise of their religion, and one the first priorities of John Leyburn, consecrated bishop of Adrumentum in 1685, was a provocative confirmation tour of the country which took him from London to the north, and back again through the Midlands. The surviving register of Leyburn's episcopal progress records 20,859 confirmands.Footnote 107 This conspicuous Counter-Reformation spectacle both reflected and fuelled the high hopes of the faithful for the reconversion of England.

Conclusion

Confirmation has proved to be a flexible tool for exploring the theological and liturgical upheavals inaugurated by the English Reformation and its ongoing repercussions over two centuries. Its plural histories have helped to illuminate the ways in which a movement that fundamentally redefined the very meaning of ritual selectively retained and remodelled ceremonies designed to mark the initiation of individual Christians as full members of the Church in heaven and on earth. The debates that this process set off turned around the Church's apostolic heritage and bodily gestures that had their roots in the Bible. This engendered a multiplicity of modes of confirmation that reflected, as well as facilitated, the splintering of Protestant Christianity and its differentiation from Roman Catholicism. Yet if this rite of passage was a fillip to schism and separation, it was also an agent of solidarity and group cohesion. Reformed ambivalence about this ritual did not prevent it from becoming and remaining the focal point of popular piety in Tudor and Stuart society, as well as a ceremony of initiation valorized by clergy of different persuasions, even if they disagreed about its outward form and inward significance. Creating occasions that fused spirituality with senses of belonging and community, confirmation brought people together to celebrate the transition from religious immaturity to knowledge. It was the moment at which, whether they were children in years or understanding, confirmands symbolically came of age and became adults in faith. For contemporaries, this was a potent metaphor for the religious conversion of institutions and systems as well as individuals. It was a way of conceptualizing the momentous ecclesiastical transformation initiated in the early and mid-sixteenth century. In this sense, the Reformation itself may be seen as a rite of passage.