Among categories of religious organizations, none is as important but less understood than the parachurch sector (White Reference White1983; Willmer et al. Reference Willmer, Schmidt and Smith1998). The parachurch sector primarily consists of 501(c)(3) public charities focused on providing religious goods and services, most commonly from an evangelical Christian perspective. These organizations are typically created and operated by an individual—a spiritual entrepreneur—without any sponsorship or affiliation with a denomination or congregation. As multiple observers have noted (Lindsay Reference Lindsay2008; Scheitle Reference Scheitle2010), with more than 50,000 such organizations in existence in the United States, parachurch organizations have reshaped the landscape of American Christianity. These organizations, however, have received little research attention compared to congregations and denominations. In this paper, we examine and attempt to account for the origin of unusually highly concentrated geographical clusters of parachurch organizations in four US communities: Tulsa, Oklahoma; Nashville, Tennessee; Colorado Springs, Colorado; and Washington, D.C. We do so drawing upon ideas developed by scholars who have sought to understand the high concentration of firms in “industrial districts.” We argue that the outlying nature of these communities suggests that the densities observed are not simply the result of the typical or normal factors (e.g., evangelical adherence rates) that shape the density of parachurch organizations. Piecing together the sources and nature of these more atypical factors is the puzzle that motivates our analysis.

The economist Alfred Marshall (Reference Marshall1895) coined the term “industrial district” to refer to communities that became defined by an unusual concentration of organizations from a specific industry in or around them (e.g., Silicon Valley, Motor City, Hollywood). In this research, we examine the events and conditions that appear to have given rise to four especially high concentrations of parachurch organizations. We call these communities parachurch spiritual districts. The idea of a spiritual district is not entirely without precedent. Western New York in the early nineteenth century came to be widely known as the “burned-over district” because of its high level of religious activity and innovation. At that time, the area spawned a variety of new religious movements such as the Latter-day Saints (Mormons), the Shakers, the Oneida Society, spiritualism, and the Millerites (Williams Reference Williams2002). In the 1960s and 1970s California also came to be identified as something like a spiritual district due to its high density and production of new religious movements (sometimes referred to as cults in the original research) (Bainbridge and Stark Reference Bainbridge and Stark1980; Stark and Bainbridge Reference Stark and Bainbridge1980).

Understanding the origins of parachurch spiritual districts can not only contribute to our understanding of how parachurch groups become geographically concentrated, but can also illuminate our understanding of contemporary American religion. When exploring American religious geography, it is quite common to focus on the geographical patterns of adherence to particular denominations or religious traditions. Such patterns are primarily the result of migration and settlement patterns. It is clear, however, that the geographical distribution of parachurch organizations is not driven entirely by the same dynamics of migration and settlement that, for instance, made Massachusetts highly Catholic, Nebraska highly Lutheran, or Utah highly Mormon. How did certain communities develop into parachurch spiritual districts? Even for those districts located in the highly evangelical Bible Belt, why did one Bible Belt community become a spiritual district for parachurch organizations and not another? What are the consequences for parachurch organizations and their founders of residing in a spiritual district? To generate answers to these questions we utilize archival records; organizational documents and websites; and information derived from 24 original interviews with organizational and community leaders in four spiritual districts.

Parachurch Organizations and Spiritual Districts

While social scientists, church-goers, and religious leaders have been discussing the rise of parachurch organizations for decades, many of those discussions were limited by the difficulty in bounding the population of interest (Scheitle Reference Scheitle2010). There are a few common traits, though, that characterize most parachurch organizations. First, they are almost all registered as 501(c)(3) public charities. Second, they are dominated by an evangelical Christian identity while typically eschewing any affiliation or identification with any specific denomination or even any specific sub-Christian tradition (e.g., Lutheran, Methodist) (Dollhopf et al. Reference Dollhopf, Scheitle and McCarthy2015; Scheitle Reference Scheitle2010). Finally, they are overwhelmingly focused on providing explicitly religious goods and services (Scheitle Reference Scheitle2010). This last point may seem obvious, but is often distorted by discussions of religious nonprofits as social service providers, typically in discussions of religious groups receiving government funding (Monsma Reference Monsma1996).

The religious goods and services provided by parachurch organizations are diverse. They include but are not limited to offering short-term mission trips, publishing books and other forms of media, itinerant preaching, religious music concerts, and special interest fellowship groups (e.g., Christian Cowboys). Based on a survey of parachurch organizations, Dollhopf et al. (Reference Dollhopf, Scheitle and McCarthy2015) identified six major subsectors within the parachurch population based on their survey of organizations. These subsectors were: (1) media production; (2) religious education, counseling, and preaching; (3) social and humanitarian services; (4) networking and fellowship; (5) mission work; and (6) advocacy and consulting. These categories closely overlap with previous work on identifying subsectors within the parachurch population (Scheitle Reference Scheitle2010).

In addition to engaging in particular activities, parachurch organizations also appear to cluster within certain communities. Consider table 1, which shows the 24 US counties with the highest rates of parachurch populations. These numbers come from the Business Master File, which is the IRS's list of public charities.Footnote 1 For all counties with at least 100,000 people (N = 523), the average rate of parachurch organizations is 1.74 per 10,000 people. Notably, in two counties, Williamson County, Tennessee, and Tulsa County, Oklahoma, the rate is almost five times as high as the average. Furthermore, many of the counties on this list are clustered around larger metropolitan areas, such as Colorado Springs, Colorado, and Nashville, Tennessee.

TABLE 1. Counties with largest concentration of parachurch organizations

In an analysis of founding rates of parachurch organizations (not shown here), the authors found that the key factors in accounting for why some US counties have higher founding rates of parachurch organizations are the educational level of the county populations and its level of evangelicalism adherence. These relationships were interpreted as reflecting the demand (or market) for parachurch organizations (evangelicalism) and the concentration of individuals with the appropriate characteristics and motivation to create such organizations (education and human capital). Nevertheless, it is obvious that in many counties there is more to the story than just these demographic factors. In some communities, there may be unique historical or local contextual factors driving an exceptionally dense clustering of parachurch organizations. One might think of this as the residual between what one might expect based only on those community characteristics that, in the aggregate, are responsible for generating high rates of local parachurch organizations and what is observed.Footnote 2 For example, Tulsa County, Oklahoma, is estimated to be 35 percent Evangelical Protestant, while Williamson County, Tennessee's population is estimated to be 36 percent Evangelical Protestant (Grammich et al. Reference Grammich, Hadaway, Houseal, Jones, Krindatch, Stanley and Taylor2012). These levels of evangelical adherence are similar to those in Mobile County, Alabama; Caddo Parish, Louisiana; Hinds County, Michigan; and many other Bible Belt communities, not to mention significantly behind counties like Anderson County, South Carolina, and Oklahoma County, Oklahoma, none of which display high concentrations of parachurch organizations. And the Tulsa County, Oklahoma, population is as well educated as the Oklahoma County, Oklahoma, population (29.6 percent to 29.7 percent with bachelor's degree or more, respectively). However, these other highly evangelical communities are nowhere close to having a similar density of parachurch organizations (e.g., Oklahoma County, Oklahoma's parachurch density is 2.85). How did places like Tulsa or Nashville become such hotbeds of activity for parachurch organizations, significantly above and beyond what one might expect? It is this question we now pursue. To begin answering it, we look to previous research examining the origins of what previous analysts have called industrial districts.

Industrial Districts: An Overview

Industrial districts are of interest to economists and policy makers because they are said to produce beneficial “externalities.” Externalities are the effects of an organization's activity that “spill over” into the larger community or environment. These effects are sometimes negative (e.g., pollution), but the spillover in industrial districts can also bring benefits for all the related organizations in the community. Marshall (Reference Marshall1895: 352) described some of the positive externalities produced and received by an organization in an industrial district (e.g., a movie producer in Hollywood) versus an isolated organization (e.g., a movie producer in North Dakota):

[S]o great are the advantages which people following the same skilled trade get from near neighbourhood to one another. The mysteries of the trade become no mysteries. . . . Good work is rightly appreciated, inventions and improvements in machinery, in processes and the general organization of the business have their merits promptly discusses: if one man starts a new idea, it is taken up by others and combined with suggestions of their own; and thus, it becomes the source of further new ideas.

In other words, being around other firms producing similar products and pursuing similar markets can lead to higher levels of creativity, productivity, and learning (Cainelli Reference Cainelli2008).Footnote 3 Locating an organization in a relevant industrial district can also yield material advantages. For example, industrial districts often attract several supporting businesses and institutions, such as specialized suppliers, which can help reduce the costs for all the businesses concentrated within the district.

Industrial districts often represent a delicate balance between competition and cooperation (Chetty and Agndal Reference Chetty and Agndal2008). The key is that the organizations in such districts are not just selling locally, which would make the proximity of competitors more problematic. Because their markets are typically much wider than the local community, industrial district members can benefit from the organizations in their shared neighborhood and still have space to compete far beyond that neighborhood. Interestingly, the rivalries produced by being close to each other are one of the mechanisms that motivates creativity and innovation within industrial districts (Boari et al. Reference Boari, Odorici and Zamarian2003).

On the Origins of Industrial Districts

The potential benefits of industrial districts have led many governmental policy makers to encourage the active creation of such districts through various tax incentives and zoning policies, reasoning that they can help local businesses compete more effectively and, in turn, increase resource flows to the local community (van Dijk Reference van Dijk1995). While this intentional policy making has no doubt aided in the development of some industrial districts, many districts have emerged without such intentional planning. Indeed, the origin of many industrial districts presents a classic “chicken and egg” problem. The benefits provided by an industrial district may shape organizations’ decision to reside in the district, but those benefits do not exist until a critical mass of organizations resides in the district. This suggests that, in the absence of a deliberate intervention, many districts originate through forces that are outside the control and even awareness of the districts’ member organizations and governmental policy makers.

To better understand the origins of these naturally occurring industrial districts, Klepper (Reference Klepper2011) examined the history of the automobile industry in Detroit, Michigan; the tire industry in Akron, Ohio; the semiconductor sector in Silicon Valley, California; and the cotton garment sector in Dhaka, Bangladesh. What he found was more a story of spin-offs. In each of these districts an initial successful firm, such as Olds Motor Works in Detroit, was directly or indirectly connected to the foundings of many of the other similar organizations in the district. This has been found in other studies as well, such as Lamoreaux et al.’s (Reference Lamoreaux, Levenstein and Sokoloff2006) study of Cleveland, Ohio, and the role of Brush Electric Company in producing many of the city's late-nineteenth-century inventors and industrialists.

Other research has pointed to the nature of a community's institutions and infrastructure as one of the keys in explaining why industrial clusters or districts appear in one place and not another. Universities have been identified as playing a key role in the development of so-called knowledge clusters. For instance, Silicon Valley's development is linked with Stanford University, while Cambridge's IT and life sciences sector is connected to Cambridge University (Audretsch et al. Reference Audretsch, Aldridge and Sanders2011; Huggins Reference Huggins2008). Universities are playing an important role in the formation of business clusters in the developing world as well (Wu Reference Wu2007; Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Watanabe and Griffy-Brown2009). There are many religious colleges and theological seminaries in the United States. At least some of these might have a role in the origins of a spiritual district for parachurch organizations.

On Industrial Districts and Religion

As the preceding discussion makes clear, the theory and research on industrial districts rests very much on the theoretical assumption of organizational competition, which is not surprising given that it is typically applied to analyses of for-profit organizations, where competition between organizations is take for granted by most analysts. This raises the question of how appropriate the concept of competition is when exploring the context of religious nonprofit organizations. Indeed, this question taps into a larger, long-running debate within the social scientific study of religion about the appropriateness of using economic conceptualization and propositions for the study of religious organizations (e.g., Miller Reference Miller2002, Reference Miller2006). It is important to remember, though, that parachurch organizations are quite different from most religious congregations and denominations. Most congregations rely on a consistent membership base of individuals, many of whom have long-standing ties to their congregation and community. Such long-term personal membership bases are rarely the source of support for most parachurch organizations (Scheitle Reference Scheitle2010). The large majority of parachurch organizations rely on marketing their goods and services, whether those goods and services are mission trips, concerts, books, or public-speaking engagements. Indeed, one of the standard critiques of parachurch organizations is that they operate too much like businesses (Fitch Reference Fitch2005). This does not mean that parachurch organizations never cooperate with one another or with other kinds of organizations, nor does it mean that parachurch organizations never consider broader goals beyond organizational survival. But such assumptions would not be accurate for many for-profit businesses, either, even though analysts approach understanding them with competition as one of the important assumptions about their emergence, growth, and survival.

Methods

To better understand how parachurch spiritual districts came into existence, we focus our attention on the four districts shown in table 2: Tulsa, Oklahoma; Colorado Springs, Colorado; Nashville, Tennessee; and Washington, D.C. We chose Tulsa and Nashville because they represented the top two counties in terms of parachurch concentration, and they held this position by a large margin. As we noted earlier, even acknowledging the Bible Belt locations of these districts does not immediately explain their density of parachurch organizations. In short, Tulsa and Nashville appeared like natural cases for study given their unusual density of parachurch organizations. We then added Colorado Springs and Washington, D.C., to our case studies because, of those counties with the highest parachurch concentrations (listed in table 1), these two were geographically unusual in that they are not a part of what many consider the so-called Bible Belt. That is, we suspected based on our initial examination that the origins of these two districts might be unique given their seemingly unique locations. Furthermore, Colorado Springs has been singled out in popular and scholarly writing as being unique because of its parachurch community (e.g., Scheitle and Finke Reference Scheitle and Finke2012). This previous notoriety contributed to our motivation to examine this case further.

TABLE 2. Summary information of interviews in four spiritual districts

In examining the origins and dynamics of these parachurch spiritual districts, we rely on a combination of 24 interviews, publicly available documents, IRS records, and organizational websites. Table 2 provides an overview of our interviews. The interviews were semistructured, generally lasting between one and two hours, and were primarily conducted in person, typically in an office or at a local coffee shop. On a few occasions, when the interviewee was willing to participate but unavailable when the interviewer was going to be in the local area, the interview was conducted using a phone or Skype. We attempted to arrange interviews with the primary founders and were able to in most cases, though in some instances, generally with older organizations, the founder was no longer involved. In those cases, we spoke with current organization leaders/staff who were involved early in the organization formation process and knew the founder personally or current leaders who were familiar with the organization's history. Interviews were conducted between 2011 and 2015. Organizations targeted to be interviewed were identified first through IRS records as being consistent with the type of organization in the study (i.e., an NTEE-1 X-code) and being located within the geographic proximity of the identified spiritual districts. The organizations that fit these criteria were then sorted by organizational founding dates so that those founded during approximately the same time frame as those included in our survey—the early to mid-2000s—could be identified and prioritized for contact. Starting with those organizations closest to this founding time frame, groups of approximately 15 to 20 organizations at a time were identified and researched to confirm organizational details (as some organizations no longer operated in the area in which they had registered) and for contact information (some of the organizations lacked current contact information). Any organization determined be in the appropriate geographical area for which contact information was also available then received an e-mail from us explaining the project and requesting an interview. When each set of organizations was exhausted without having successfully generated an interview, the organizations with the next-closest founding dates to the survey's sampling time frame were contacted until all interview slots were booked for a given hotbed community. Given the relatively high failure rate and small size of many of these parachurch organizations, each group of 15 to 20 organizations researched would usually result in only one or occasionally two completed interviews.

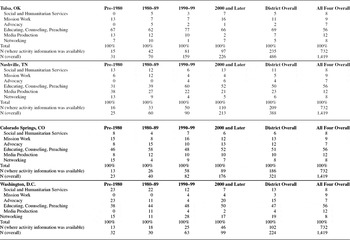

Another primary source of information was an organization's tax return forms, referred to by many as IRS 990s. In addition to containing financial information, these forms also contain descriptions of organizational activities and missions, which we used to classify organizations in the four spiritual districts into an activity-based subsector. Specifically, we classified all hotbed organizations into the six subsectors identified by Dollhopf et al. (Reference Dollhopf, Scheitle and McCarthy2015). However, lower revenue organizations are not required to file these forms, so our ability to code activities was restricted for such organizations. The proportion of organizations for which we could identify activities varied across the four districts we examined. For instance, we could identify activities for 57 percent of the organizations in the Colorado Springs district but only 32 percent of organizations in D.C. Nevertheless, quite a bit of data was available overall from the tax forms, which was supplemented with additional information from publically available documents and organizational websites to compile the data set on which the spiritual district analyses are based. Table 3 shows the distribution of organizations by primary activities and ruling date for each sector. The ruling date for an organization is the date that the organization received tax-exempt status from the IRA. It is not a perfectly valid measure of a founding date because there is often a gap between the establishment of an organization and its filing with IRS, but it is often used as a rough proxy. Experts generally recommend examining the ruling date with larger time intervals rather than specific years to account for some of the uncertainty and error it contains (National Center for Charitable Statistics 2006), so we present four time periods as shown in table 2.

TABLE 3. Distribution of parachurch organizations by district, sector, and IRS registration period (i.e., ruling date)

On the Origins of Spiritual Districts

We begin our examination of parachurch spiritual districts by providing an overview of the history and the unique dynamics within each of them.

Tulsa, Oklahoma: A Successful Initial Inspirational Entrant

In 1948, a religious nonprofit known as Healing Waters, Inc. was established in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Healing Waters, Inc. was founded by Granville Oral Roberts, or simply Oral Roberts, as he became more commonly known. In 1957, the name of Healing Waters, Inc. would be changed to the Oral Roberts Evangelistic Association (Harrell Reference Harrell1985). As we will see, this organization would serve as a catalyst for Tulsa's parachurch transformation, becoming one of the densest clusters of parachurch organizations in the United States.

As his organization and national profile grew, so did Roberts's status in the city. Likely the largest imprint that Roberts and his organization left on Tulsa resulted from the decision in 1961 to establish a school for training evangelists. What began as a small idea would blossom and expand into plans for a full-scale university grounded in the Pentecostal tradition. This university was named, naturally, Oral Roberts University (Harrell Reference Harrell1985). Although legally a separate organization, the university was effectively a subsidiary of the Oral Roberts Evangelistic Association until a scandal forced a clearer separation in 2008 (Blossom Reference Blossom2009). The university's impact on Tulsa, however, goes far beyond the local tourist draw of the campus's iconic prayer tower. Oral Roberts was quoted as saying that he wanted to establish Oral Roberts University to “perpetuate my ministry and multiply it thousands of times” (quoted in Harrell Reference Harrell1985: 207). There is much evidence that he succeeded in achieving this goal. As one interviewee noted, “Oral was trying to bring the ministry of the Holy Spirit into reality in the present day church” and this focus on the here and now may explain the partial manifestation of Roberts's vision in nonprofit organizations.

As shown in right-hand column of table 4, 58, or about 12 percent, of Tulsa's parachurch organizations were founded by alumnae/i of Oral Roberts University. This is undoubtedly an underestimate because those 58 only include organizations for which we could locate some biographical information on the founders through a website or other source. If we limit the denominator to only those organizations for which we could find biographical information, Oral Roberts University alumni lead more than one-fifth of the parachurch organizations in Tulsa.

TABLE 4. Tulsa Area parachurch organizations and their direct founders’ direct and indirect connections to Oral Roberts University

These direct ties, though, do not provide the full picture of the Oral Roberts's role as a catalyst for spiritual entrepreneurialism both in and outside of the Tulsa spiritual district. If we look in the middle column of table 4, we see that an Oral Roberts University alumnus, Billy Joe Daughtery, founded his own bible institute in Tulsa that has, in turn, spawned several Tulsa-based parachurch founders.Footnote 4 We can draw other indirect connections between the Oral Roberts organizational complex and other parachurch founders in Tulsa. As shown in the left-hand column of table 4, Oral Roberts's friend and influential evangelist in his own right, Kenneth E. Hagin, founded the Rhema Bible Training Center in Tulsa. This center is currently led by his son, Kenneth W. Hagin, who is an alumnus of Oral Roberts University. Rhema Bible Training Center has produced numerous spiritual entrepreneurs who have gone on to found their own parachurch organization in Tulsa.

The Tulsa spiritual district is heavily built around personality-driven organizations. One sign of this is how many of the parachurch organizations appear named after an individual. Based on our analysis of organizational names, 34 percent of Tulsa parachurch organizations are named after a person. This compares to 17 percent of the total number of organizations in the four spiritual districts we examine. While Oral Roberts proved that such personality-driven organizations can grow into something larger and more durable than that one person, many of these organizations are likely more fragile as they often depend on the interest and health of their namesakes. Comparing Tulsa to the other districts in table 3, it is also clear that its parachurch sector is more heavily weighted—well above the average—toward preaching ministries, consistent with our finding of the heavy concentration of person-centered parachurch groups. Looking across the time periods shown in table 3, the preaching focus on Tulsa organizations was present from the beginning and has not changed much over time.

Colorado Springs: The Planned District

Colorado Springs has been called the “Vatican of American evangelicalism” (Rabey Reference Rabey1991), and described by others as a “Mecca” for Evangelical Christians (Brady Reference Brady2005). On the surface this would seem to be a misnomer. Neither Colorado nor Colorado Springs exhibit high rates of adherence to evangelical churches (The Association of Religion Data Archives 2012). But it is not Colorado Springs’ churches or church members that made it a particularly unique place in America's religious geography. Instead, it is its role as probably the most prominent and well-known cluster of parachurch organizations in the United States (Scheitle and Finke Reference Scheitle and Finke2012).

The seeds of Colorado Springs’ spiritual district began to be planted when, in 1946, a Christian organization called Young Life moved to Colorado Springs from Texas. Young Life began in 1938 when Jim Rayburn, a Presbyterian minister, developed the idea of starting Christian clubs within schools to minister to youth who do not attend church. In 1941, Rayburn would formally establish Young Life to replicate his clubs in schools across the country. Five years later, he would relocate the organization to Colorado Springs (Young Life). A few years later a real estate broker contacted Billy Graham about a vacant property in Colorado Springs called Glen Eyrie. Graham ultimately decided to pass on purchasing the property for his revivals ministry but only after he convinced The Navigators, a Christian parachurch organization with whom Graham had previously collaborated, to purchase the property for themselves (“The Navs: 1951–Today”). Both Young Life and The Navigators are still headquartered in Colorado Springs. This early history would seem to point to the same story of a successful early entrant leading to the development of a cluster. While The Navigators and Young Life might have laid some groundwork, however, there is little evidence that they had as much of a direct and active role in the development of Colorado Springs’ spiritual district, at least anywhere near to the same extent as Oral Roberts did in Tulsa. Our examination supports another account that suggest that this spiritual district really began to develop vigorously only in the 1980s (Rabey Reference Rabey1991). As one interviewee reflected, “Navigators has always been here . . . [but] Focus for the Family moving here in early ‘90’s . . . was really what . . . turned Colorado Springs into the Christian ministry mecca.”

The acceleration of the Colorado Springs cluster was partially the result of external economic forces. Consider the case of Focus on the Family, a well-known Christian publishing and media organization. Focus on the Family was headquartered in California until 1991. In the late 1980s, Focus on the Family began looking for a larger space elsewhere as the cost of doing business in California was becoming, they thought, prohibitive because of its expensive property, stringent regulations, and high taxes (Rabey Reference Rabey1991). But it was not just happenstance that led the organization to settle on Colorado Springs. There was an active effort on the part of city officials to recruit nonprofits, and initially Christian nonprofit organizations.

Leaders of the Colorado Springs’ Economic Development Corporation (CSEDC), in particular a woman named Alice Worrell, reached out to Christian organizations to convince them to relocate to the city (Finley Reference Finley1996; Hazlehurst Reference Hazlehurst2007; Rabey Reference Rabey1991). Worrell benefited from her contacts and experiences growing up as the child of parents who taught at an evangelical college (Finley Reference Finley1996). In 1996 Ted Haggard, a Colorado Springs pastor (and graduate of Oral Roberts University) who would later become the powerful leader of the National Association of Evangelicals before a sex scandal ended his career, credited Worrell for the origin of the city's cluster of parachurch organizations (quoted in Asay and Philipps Reference Asay and Philipps2006): “We prayed over the businesses, we prayed over the government. And it was during that time that the city hired a woman that encouraged parachurch ministries to move here.” As Worrell stated in 1991 in a local newspaper, “[B]eing a Christian, it gives me special pleasure and rewarding feeling to be able to work with these kinds of people” (Rabey Reference Rabey1991). Her personal touch worked, as it convinced Focus on the Family and dozens of other organizations to settle in Colorado Springs. It also helped that a Colorado Springs–based foundation, The El Pomar Foundation, provided Focus on the Family a four-million-dollar credit to help with the move (Finley Reference Finley1996).

When recently interviewed for this research, a representative of the CSEDC discussed the broader context that led Colorado Springs to become a destination for nonprofit headquarters. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the area was coming out of a recession and was desperate to attract new jobs. According to the interview, attracting nonprofit headquarters to the area—not just faith-based ones—was a strategy to redevelop and diversify the local economy. As the CSEDC representative noted:

[W]e had just come out of a pretty bad recession in the late ‘80s in our community and so I think our community was desperate for jobs and so they were just out there looking [for] what we can strategize to attract to this community. They were able to get one [Focus on the Family] and it just kind of snowballed.

Nashville, Tennessee: A Spiritual District within an Industrial District

Nicknamed the “The Buckle of the Bible Belt,” Nashville is home to institutions like the LifeWay Christian Resources (the publishing arm of the Southern Baptist Convention), the National Baptist Publishing Board, the United Methodist Publishing House, Thomas Nelson Publishers, and a number of Christian colleges like David Lipscomb University and Belmont University (Guier and Finch Reference Guier and Finch2007). It might be unsurprising, then, that Nashville area should be densely populated with parachurch organizations. The most distinctive feature of Nashville's parachurch district, though, resides not so much in these long-standing publishing and educational religious institutions, but rather in the proliferation of its many gospel music ministries, feeding off Nashville's vital for-profit “country music” and “gospel music” industries.

In 1925, the National Life and Accident Insurance Company began a new radio station in Nashville called WSM. The station created a live music broadcast called the WSM Barn Dance, primarily as a way of advertising insurance. One day in 1927 the Barn Dance program followed a broadcast of opera classics. The host began the Barn Dance by saying, “You've been up in the clouds with Grand Opera, now get down to earth with us in a performance of the Grand Ole Opry” (Feiler Reference Feiler1998: 27). The Grand Ole Opry would become synonymous with country music, eventually becoming widely broadcast on television, as well. This would lay the groundwork for Nashville to become the center of the country music world.

The connection between this and Nashville's status as a parachurch spiritual district becomes clearer once one understands historical, social, and economic links between country music and Christian music. Country music has often spilled over into Christian music, and vice versa. Consider the following statement by Bill Hearn, President and CEO of the EMI Christian Music Group, a subsidiary of EMI Music, which is one of the largest music companies in the world (Beaujon Reference Beaujon2006: 182): “There is no real market for country Christian music. . . . I think your average country fan is kind of a God-fearing American. Why do I need country Christian when all country is Christian?” So, given this elective affinity between the country and Christian genres, as Nashville became the center of the country music industry it also became the center of the Christian music industry. It should be noted, however, that at one point it appeared as if the Christian music industry might not concentrate so densely in Nashville. For many years Waco, Texas, served as a competing center of the Christian music industry. This center coalesced around Waco-based Word Records, which was founded by a Baylor University graduate named Jarrell McCracken (DeWitt Reference DeWitt2010; Howard and Streck Reference Howard and Streck1999). However, the gravity of Nashville's growing role in the country-Christian industry would eventually pull Word away from Waco. As occurred in the rest of the music industry, a series of corporate buyouts and mergers ended with Word relocating to Nashville.

Reviewing the parachurch organizations in Nashville, we find scores of organizations with connections to the Christian music industry. Many are explicitly focused on producing Christian music and/or promoting a Christian musician. For instance, Pam Thum Ministries is centered on its namesake, who has been nominated for a Grammy and for multiple Dove Awards (given out by the Gospel Music Association based in Nashville). A full account of Betty Jean Robinson's nonprofit gospel ministry is available in her book, Upon Melody Mountain, for sale on her website. Also representative are two family groups of gospel singers, the Joel Hemphill Gospel Association and the Goodman Family Ministries. Both are Nashville-based family gospel enterprises operating as nonprofit parachurch organizations.

With Nashville's dominant music industry, why have so many parachurch music organizations registered as nonprofits rather than maintain affiliation with a for-profit music business or create a business of one's own? One interview with the manager of a gospel parachurch organization, which started out as a for-profit business, sheds light on this:

One of the things we wanted to do [with the nonprofit] was help pass our knowledge on that we have learned over the years. We see a lot of artists out there that have the American Idol goal and we have wanted to help them learn how to be ministers. We have a lot of individuals who are now on the road all the time and have jobs in music groups or drive in a church or have their own ministry so I don't think if we had not had a nonprofit we would have done that.

There are other parachurch organizations founded by Christian musicians that are not focused primarily on producing or promoting Christian music. For instance, the Katina Foundation was founded by a Christian band named The Katinas to help raise funds for missionary projects to help benefit communities. There are even ancillary parachurch organizations dedicated to helping support the Christian music industry in Nashville. PR Ministries was founded by Michael Guido with the goal of ministering to and supporting Christian musicians. As described by PR Ministries (Reference Ministries2012): “The ministry extends to artists and their families when on tour, at home, and in the studio. While artists are on the road, Michael travels with them as their road pastor. This includes Bible study, prayer time, and worship.” Guido has become one of the more prominent musician-serving chaplains, having worked with major Christian acts like Michael W. Smith, dcTalk, and Jars of Clay (Wiechman Reference Wiechman1998).

Our content analysis of the primary stated purpose and activities of the parachurch organizations across districts (taken from the IRS financial returns of the organizations) corroborates the importance of music production and performance to the Nashville spiritual district. As shown in table 3, more than one-fifth of the parachurch organizations in Nashville are focused on media production, almost twice the overall rate seen in the four districts we examine. However, looking at the different time periods shown in table 3, we see that organizations founded in the earliest time periods were even more heavily concentrated in the media production category.

Washington, D.C.: The State-Anchored District

Washington, D.C., like Colorado Springs, might surprise many as the location of a parachurch spiritual district. However, religious organizations have long looked to locate themselves in the area. Lieberson and Allen (Reference Lieberson and Allen1963) found that 10 percent of the national headquarters of religious associations were in Washington, D.C. Indeed, many denominations have an office in Washington for the purposes of advocacy (Kraus Reference Kraus2007). In two of the D.C.-based parachurch organizations we interviewed, the organizations were affiliated with specific religious denominations and found it useful to be near denominational offices, which were in turn located in D.C. to be near the center of national political power.

Examining parachurch organizations in the Washington, D.C., spiritual district, we find several organizations have an understandable interest in government policies, for instance the Catholic Immigration Network and the Center for Interfaith Action on Global Poverty. We also find some membership organizations that might benefit their membership by being at the center of political influence. These include organizations like the International Christian Chamber of Commerce.

A wide range of advocacy-focused parachurch organizations have their base in Washington, D.C. Indeed, looking at table 2 we see that the proportion of advocacy-focused organizations is double that seen across all the districts. For example, Sojourners (“Our Vision” 2015), according to their website, “is a national Christian organization committed to faith in action for social justice . . . that convenes, builds alliances, and mobilizes people of faith, focusing on racial and social justice, life and peace, and environmental stewardship.” One social justice-focused parachurch organization we interviewed mentioned the usefulness of having access to the Congress and the Supreme Court and emphasized that their proximity to policy making was very important for their efforts, underscoring the unique nature of the particular organizations that comprise the Washington, D.C., hotbed.

In addition to the relative commonality of social justice–oriented parachurch organizations in Washington, D.C., we see in table 3 that almost one-fifth of the parachurch organizations in Washington, D.C., are classified as having networking as one of their primary activities, which is double the rate seen in any other spiritual districts. For instance, Foundations and Donors Interested in Catholic Activities “is a network of highly respected major philanthropists, with a distinguished history of success in identifying approaches to giving that have lasting impact. . . . Through its trustee training, research, conferences, consulting services, and links with some of the most experiences private philanthropies assisting Catholic institutions, it provides the essential edge in intelligent and reflective giving.” Similarly, one of the organizations we interviewed effectively functions as a network of people and resources to serve a particularly age constituency of a major denomination; the organization is officially considered a “liaison” for its denomination. In this instance, the networking is largely internal to a particular organization, but allows for the coordination of activity for what had previously been disparate programs, trainings, and ministries.

Overall, proximity is a main theme underlying the location decisions for the types of institutions that dominate the parachurch scene in Washington, D.C.—both proximity to political power as well as proximity to the other people and organizations who are in Washington, D.C., for access to this political power.

Discussion

Having briefly examined the history and composition of these four parachurch spiritual districts, we now turn to highlighting some important themes and drawing specific connections to previous research on industrial districts.

On the Varying Origins of Spiritual Districts

Our exploration of these four communities highlights how “spiritual districts” can be produced by diverse causes and dynamics, much as is the case shown by analyses of industrial districts. It is these historically specific origins and particular community-level dynamics that were central in generating the unusually high concentration of parachurch organizations we find in them, rates much higher than would be expected purely based on demographic factors that generate the distribution of concentrations across all large counties in the United States.

Tulsa appears consistent with Klepper's (Reference Klepper2011) argument about the importance of a highly successful initial entrant into a community as a potentially powerful potential origin of a district. Because many organizations in a district have prior relationships, a dense network of ties exists in the district that can produce a unique “social milieu” (Mottiar and Ingle Reference Mottiar and Ingle2007: 669). As we see in Tulsa, many founders are tied to one another as alumnae/i of Oral Roberts University, Rhema Bible Training Center, or the Victory Bible Institute. Such a thickly networked local environment can lead to a culture of what Mottiar and Ingel (Reference Mottiar and Ingle2007: 669) call “interpreneruship,” or phenomenon of “collective entrepreneurship.”

We interviewed leaders in several organizations in Tulsa that we expected might be outside the tight orbit of the pervasive Oral Roberts network, but we still discovered ties to that institution. One leader mentioned working directly with Oral Roberts University and another mentioned that his children had attended Oral Roberts University. Even among the Tulsa parachurch organizations without direct ties to Oral Roberts University, however, the founders/leaders were keenly aware of the penetration of Oral Roberts University into their community, generally acknowledging the impact and influence of Oral Roberts University. One respondent who was not connected with Oral Roberts University but was familiar with Oral Roberts's work suggested “Oral Roberts would probably . . . have the same philosophical background as what we do.” Another interviewee, who also was unconnected to Oral Roberts University, underscored the importance of the Rhema Bible Institute and Oral Roberts to the spiritual nature of Tulsa, suggesting that “[with] Rhema of course and then Oral Roberts . . . the gospel has saturated this community in many ways because of those strong ministries. We just happen to be one among many and there are other non-faith based ministries here who are not connected to Rhema or Oral.”

Five of our interviewees came to Tulsa specifically to connect to its ministries. One religious nonprofit founder moved to the area in the late 1980s to attend Rhema Bible Institute. This interviewee noted that when they were setting up the nonprofit, the Rhema Bible Institute could recommend a local law office that specialized in the 501(c)(3). Another founder came to the area because he felt called to attend a local Christian college and stayed in the area afterward. Yet another moved to Tulsa initially to work with a particular nonprofit and ultimately founded the US-based office of an international ministry. The other two founders, a married couple, moved to the area on a leap of faith to connect with the Oral Roberts University scene: “[W]e were ripe to say, all right, there's nothing keeping us here, let's just load up the kids and go to ORU.” Later in the interview, the founders further elaborated: “[W]e ended up out here because Oral Roberts was the only one we knew of who actually believed that God could make a difference in people's lives.”

The Tulsa spiritual district does depart from the typical business district in at least one important way. Klepper (Reference Klepper2011: 152) noted that, while a nodal firm often has an important role in generating a district, it often has little motivation in playing this role. In fact, its directors might even want to discourage playing such a role because the spin-offs often result in the firm losing experienced employees and lead immediately to more extensive local competition. In Tulsa, though, we see that the nodal firm, the Oral Roberts Evangelistic Association, played an active role in generating spin-offs. This observation was reiterated in one interview, where the founder said: “They've [Oral Roberts University] had a huge . . . footprint . . . every full gospel ministry in Tulsa has had some kind of a link to Oral Roberts University. . . . Oral Roberts’ vision was to . . . go into every man's world with the gospel . . . almost everywhere I go [in the world], I see the footprint of Oral Roberts University.”

If Tulsa shows us how the proliferation of organizational spin-offs can lead to the creation of a spiritual district, Nashville illustrates how a spiritual district can spin-off from an industrial district. The firms of Nashville's country music industrial district have a natural affinity with many of the parachurch groups that compose its spiritual district. What is perhaps most notable about Nashville's spiritual district is the diversity of organizations that have arisen even within the seemingly narrow category of music-related organizations. Of course, Nashville is also host to plenty of parachurch organizations with no connections to music or the music industry, which also speaks to the effects of collective entrepreneurship that was discussed in the context of Tulsa.

Both the Colorado Springs and Washington, D.C., cases illustrate the central role that government can have in producing spiritual districts, although the role of government in each is very different. In the case of Colorado Springs, a local government agency intentionally sought to convince existing parachurch organizations to relocate to its city. These initial entrants provided an aura of legitimacy and inspiration to other parachurch organizations enhancing their likelihood of moving to the area as well as to new spiritual entrepreneurs contemplating establishing organizations in the community (Meyer and Rowan Reference Meyer and Rowan1977).

By contrast, there was no active recruitment on the part of officials in Washington, D.C., of which we are aware. The case fits neatly, however, into the category that Markusen (Reference Markusen1996: 299) calls “state-anchored industrial districts,” or communities dominated “by one or several large government institutions such as military bases [or] state or national capitals.” In discussing these state-anchored districts, in contrast, however, Markusen focuses on the suppliers and customers of these public institutions, such as housing businesses for a public university or defense contractors for military bases. Given this framework, how can we understand Washington, D.C., as a spiritual district? How might a parachurch organization be a supplier or customer of the federal government? To answer this question, we must expand the focus goods and services beyond those normally encompassed by such a conceptualization of supplier and customer. Centers of government do not simply create an inflated market for goods and services. They also create an inflated market for media, influence, and advocacy. In short, places like Washington, D.C., serve as a magnet for the headquarters of interest groups, and many of the parachurch organizations based there qualify as interest groups.

Many religious nonprofits may have interests that can be served by locating their headquarters at the geographic center of national political decision making. One organization we interviewed had moved its headquarters to Washington, D.C., in the 1990s and elected to stay in Washington, D.C., for several such reasons. These included connections to other nonreligious nonprofits and faith-based nonprofits, opportunities for engaging in coalitional work with other groups who had similarly been drawn to the area for its political centrality—as the executive director noted, “[T]he proximity to those folks makes that work easier.” In their analysis of national headquarters of voluntary organizations, Lieberson and Allen (Reference Lieberson and Allen1963; see also Walker, 1991) found that Washington, D.C., was second only to New York City as the location of such offices. They noted that “Washington exerts a strong ‘pull’ for voluntary associations that function on behalf of its members to represent their interests to the federal government” (323). Furthermore, examining trends in the location of headquarters in the early twentieth century, they found that Washington, D.C., was gaining headquarters faster than other cities, suggesting that “Washington's role as a center for voluntary associations has grown in recent decades” (337).

On the Benefits and Drawbacks of Spiritual Districts for Organizations

In addition to providing greater insight into the different origins of spiritual districts, our interviews also provided insights into some of the advantages and disadvantages being in a spiritual district of parachurch organizations and entrepreneurs may provide. These insights reinforce previous discussions of the often-coexisting cooperative and competitive tensions often found in industrial districts (Chetty and Agndal Reference Chetty and Agndal2008).

Many of our interviewees spoke of the benefits of being in a spiritual district. As previously mentioned, one organizational founder in Tulsa described the effect of having major Oral Roberts University ministries located in town: “[T]he gospel has saturated this community in many ways because of those strong ministries.” Another founder who had no direct Oral Roberts University connections described moving his ministry to Tulsa after getting a job in the area, noting that he received strong support in the community from people who were connected to the region's ministries and found it to be a favorable place to operate a ministry even though he arrived in town with no connections. It appears that the strong network of ministries Oral Roberts University spinned off throughout Tulsa has created an environment that is conducive to parachurch founding and operation generally, because one need not look too far to connect to the Oral Roberts University network or to benefit from the environment of spiritual entrepreneurship even if one does not have direct connections to the major Tulsa-based ministries.

One of our interviews in Nashville was with the leader of a music-based nonprofit that performed in congregations and for various church groups around the country. While the ministry had a record deal, eventually the organization reorganized as a nonprofit and became more oriented toward churches rather than sales through the music industry. The manager notes, though, that it had been beneficial to be near Nashville's music industry if not directly in it: “[I]t helps [to be in Nashville] in the sense of, if you need individuals, be it, publicity people or musicians, recording studios or music publishers, ninety-nine percent of the time, they're here. We're not in the music industry, our . . . ministry is more . . . aimed toward church work, that's where our heart is.”

Donors, of course, are often central to sustaining a 501(c)(3) and having a dense population of parachurch organizations in a particular area might be expected to make fundraising more difficult because of more intense competition. Both the interview with the CSEDC and an interview with a local religious nonprofit suggested, however, that the donor bases for Colorado Springs’ parachurch organizations often lie outside of the area. This may be both cause and consequence of Colorado Springs’ ability to sustain such a dense population of parachurch organizations. As one nonprofit founder reflected, “Very little of our funding comes from Colorado Springs. . . . If you're a Christian living in Colorado Springs, you're already aware of all the big ministries in here you're probably already giving to multiples ones.”

Another consequence of the dense, concentrated populations of parachurch organizations is the opportunity for collaboration, which was particularly apparent in Colorado Springs. The leaders of at least two small organizations who were interviewed mentioned having received training at other local nonprofits that helped them start their own ministries; one pair of founders specifically attended a local seminar on how to form a 501(c)(3): “They give you all the outlines, all the paperwork . . . by 3 o'clock in the afternoon [that same day], we had a Colorado nonprofit.” Another founder mentioned that the organization's staff members had started to take advantage of seminars and leadership development training offered by The Navigators, a large nonprofit headquartered in the area. Overall, the comments of Colorado Springs’ interviewees supported the benefits of “synergy” that happens when multiple organizations in the same sector are located nearby. None of the interviewees suggested the environment was prohibitively difficult to work in (although presumably organizations that experienced intense competition would probably have been less likely to survive and, hence, appear in our sample). One organizational leader expressed indifference to the high density of parachurch organizations, commenting that she figures “there's always plenty of ministry to go around.”

Our interviewees in Washington, D.C., though, appeared to be more aware of the potential competitive dynamics of residing in a spiritual district. Two of the organizational leaders interviewed recognized that there is a fine line between collaboration and competition. As for coordination and competition with other organizations, one D.C. executive director said it's “in reality, a little bit of both.” Another executive director described his group's cooperative/competitive relationship with organizations pursuing similar goals by saying, “We lovingly refer to it as the frenemy status.” Across hotbeds, however, the overarching narrative pointed toward niche filling, which allowed many organizations to benefit from collaboration. The origins of a hotbed may contribute to whether parachurch organizations are more likely to collaborate or focus on finding highly specific niches (Hannan et al. Reference Hannan, Carroll and Pólos2003), or whether their collaborative relationships are likely to spill over into competition. Overall, though, this network of other organizations may not only provide parachurch organizations in a hotbed with collaborative opportunities, but also may encourage them to develop highly specific niches to stay viable—which, as noted with organizational fundraising, can allow an organization to use its distinctiveness to attract donors to their particular organization in contrast to other similar ones.

Conclusions

Our analysis of four prominent spiritual districts in the United States—Tulsa, Oklahoma; Colorado Springs, Colorado; Nashville, Tennessee; and Washington, D.C.—highlights some major factors contributing to the industrial district phenomenon that lend, we believe, further insight into how these processes operate outside of the for-profit organizational realm. These factors include the presence of a central organizing force, the provision of positive externalities to a community, the presence of competition beyond the immediate locale, and the growth of ancillary organizations related to the initial central organizing force and its resulting infrastructure. Together, these factors help account, to a greater or lesser degree, for the especially high concentrations parachurch organizations in spiritual districts, concentrations far higher than would be expected based only upon their religious and demographic composition.

First, like the classic US industrial district examples of Motor City and Silicon Valley, each spiritual district we analyzed had a central catalyst that appears to connect directly to the district's growth. What this catalyst was, however, varied across locations, as it does, as well, for industrial districts. Similar to the growth of Silicon Valley, an educational institution played a major role in the development of Tulsa, Oklahoma, as a spiritual district. Colorado Springs, Colorado, and Washington, D.C., both benefit from government institutions, although in quite different ways. Colorado Springs’ development was an intentional aim of the local government, while Washington's was an unintentional consequence of the attractiveness of being near the federal government. Nashville, Tennessee, as we saw, has an aligned music business sector that fuels a large parachurch music ministry presence.

As highlighted in some of the interviews, while not every organization may be directly anchored in the central organizing force that we interpreted as the primary parachurch-attracting feature of the community, many of the organizations benefitted from the resulting spillover effects of that force. The presence of organizational role models, individual mentors, and ancillary support organizations in an area can increase an environment's conduciveness to the founding of new parachurch organizations and can also foster the community attitudes, employee skills, and financial resources that facilitate parachurch success. For example, even the organizations interviewed that were not affiliated with Oral Roberts University found it beneficial to operate in proximity to the university and its spin-off organizations. As we found in the Washington, D.C., hotbed, parachurch organizations choose to locate in the area simply to tap into the existing networks among people and organizations.

As would be expected with industrial districts, we saw evidence of positive externalities spreading into the community surrounding spiritual district. A prime example of this was in Colorado Springs, where the local government perceived that a strong religious presence in the community would bring reliable employees to the region, contributing positively to the local business economy in addition to growing a parachurch base. While industrial districts may be similarly motivated by bringing in a density of desirable employees to a particular area or benefit from local networks, some spillover effects we observed are specific to spiritual districts’ particular central organizing force. For example, as discussed earlier, one parachurch founder interviewed noted in Tulsa that the “the gospel has saturated this community in many ways because of those strong ministries,” referring to Tulsa's educational anchors. Thus, a spillover for spiritual districts in the eyes of parachurch organizations may be the opportunity to share one's beliefs and live among those with similar beliefs. Proselytizing and spiritual community may be uncommon spillover effects for industrial districts, but would be expected to be reasonably common among spiritual districts.

Another feature of industrial districts shared among spiritual districts was the orientation toward competition outside of the immediate geographic area. As Hollywood produces movies to be consumed nationally and internationally, many parachurch organizations in the spiritual districts studied similarly worked at both national and/or international scales. Accordingly, most parachurch organizations raised funds from constituents outside the immediate boundaries of the spiritual district thereby avoiding local fundraising competition. In addition, while these organizations may experience pressures of competition, organizational representatives in each of the spiritual districts suggested that they had developed distinct niches, whether it was in the groups to which they appealed, the style of ministry, or the methods used to work with constituent groups. For example, one music group choose to highlight humor in their performances to be more distinctive, while another organization focused on spiritual development offered a structured writing program. One of the keys to the sustained of growth in a spiritual district, once established, may be continually expanding the diversity of newly formed organizations within the district that can maximize the benefits of collaboration while minimizing the hazards of competition.

Finally, as with industrial districts, spiritual districts spur the growth of ancillary organizations related to the central organizing force, and these organizations benefit from the resulting organizational infrastructure. Another example of this is in Nashville, where music-focused parachurch organizations benefit from the same infrastructure that has grown alongside of the for-profit music business in the area. This can be specifically seen in the Curb College of Entertainment and Music Business as part of Belmont University, which is a Christian liberal arts college in Nashville. While the music industry did not grow up exclusively around this program, it likely emerged to support the various musical endeavors, both for profit and nonprofit, that permeate Nashville.

Through our analyses, we have shown that the concept of industrial districts is robust beyond the for-profit world, particularly when adapting particular concepts for the sometimes-differing logics of parachurch organizations, such as comparing industrial versus spiritual spillover effects. Moreover, this study provides evidence that the organizational forces galvanizing industrial districts are not necessarily specific to the for-profit world; thus, we expect these concepts to be useful for understanding other organizational concentrations beyond businesses and faith-based nonprofits. While our study's scope was restricted to four major spiritual districts in the United States, future research could expand the scope to other areas of high parachurch density and could even compare them to “second-tier spiritual districts” or areas that appear to possess a central organizing force but that nevertheless have not become spiritual districts.

This study of spiritual districts has not only allowed us to deepen the conceptualization of industrial districts, but has also allowed us to better understand the patterns and dynamics of American religion. In the same way that the presence of a high concentration of people of a particular faith, as for instance Mormons in Salt Lake City, has contributed to the character of particular American communities, high concentrations of parachurch organizations are shaping their communities. The strategies of these organizations often results in the availability of a diversity of goods and services within a community and may allow more traditional religious institutions, such as local congregations or regional denominations, to engage a wider population, undertake new activities, or more intensely and efficiently focus their group energies on a certain endeavors while parachurch organizations can supplement or take over tasks that communities or denominations may have previously undertaken alone. While these effects of the growth of parachurch organizations have been seen more broadly, these effects are likely heightened in the local communities in which large numbers of them are concentrated. While the parachurch was once a rarely studied and little understood component of American religion, our analyses have shed some light on how they function alongside other organizations in their communities and how these organizations can be a galvanizing force for local communities above and beyond the impact of congregational and denominational structures that depend upon their religious composition.