Introduction

The relationship between inequality and economic development has been widely approached in the social sciences. A large bulk of the literature addresses Kuznets’s (Reference Kuznets1955) hypothesis that inequality grows during the first stages of modern economic growth to decline afterward as the economy develops further. This issue is nonetheless far from being settled. While some cross-country studies focusing on the second half of the twentieth century seem to confirm the empirical regularity of the Kuznets curve, others do not find enough support for the inverted U curve (Barro Reference Barro2000, Reference Barro2008; Deininger and Squire Reference Deininger and Squire1998; Gallup Reference Gallup2012). Footnote 1 Long-term longitudinal studies focusing on particular countries have also analyzed this issue. In the case of Britain, inequality seems to have increased in the first half of the nineteenth century during the early stages of industrialization and started falling from then on (Allen Reference Allen2009; Lindert Reference Lindert2000a; Lindert and Williamson Reference Lindert and Williamson1985; Williamson Reference Williamson1985). A similar trend is found for the United States, with a substantial rise in inequality between 1800 and 1860 (Lindert and Williamson Reference Lindert and Williamson2016). In other Western countries such as France, Germany, and Sweden, inequality also followed a U-inverted pattern (Morrison Reference Morrison, Atkinson and Bourguignon2000), while in the case of Italy no evidence is found of an increase in inequality in the early stages of development (Rossi et al. Reference Rossi, Toniolo and Vecchi2001). Likewise, although the Kuznets curve often shows up in long-term country studies, a new wave of increasing inequality has been detected for recent decades (Lindert Reference Lindert, Atkinson and Bourguigon2000b). Footnote 2

One of the main problems regarding these issues is measurement. The quality of the sources employed in the construction of inequality measures is hotly debated (see, e.g., Deininger and Squire Reference Deininger and Squire1998; Gallup Reference Gallup2012). Moreover, while research estimating the evolution of contemporary inequality is relatively abundant, the number of studies dealing with historical inequality from a quantitative point of view is still scarce. Footnote 3 Some attempts have nonetheless been made to correct this situation. Two studies led the way by measuring the distance between unskilled wages and farm rents per acre, on the one hand, and the income earnings of the average citizen, on the other, for different countries during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century (O’Rourke et al. Reference O’Rourke, Taylor and Williamson1996; Williamson Reference Williamson1997).

More recently, Milanovic et al. (Reference Milanovic, Lindert and Williamson2011) have examined this issue even further back relying on social tables from different preindustrial societies such as the Roman Empire, Byzantium, England in 1688, Moghul India in 1750, or China in 1880, only to mention some examples. Footnote 4 Alternatively, recent research has studied the evolution of top income shares for a growing sample of countries (Alvaredo et al. Reference Alvaredo, Atkinson, Piketty and Saez2013; Atkinson et al. Reference Atkinson, Piketty and Sáez2011; Piketty and Saez Reference Piketty and Saez2006, Reference Piketty and Saez2014). Footnote 5 Yet, the fact that the top income database is mostly restricted to the twentieth century does not allow capturing the potential upsurge of inequality during the early stages of development. Footnote 6

The lack of information regarding inequality in nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century Spain has similarly long troubled historians and impeded to follow its evolution, as well as a proper assessment of the relationship between this variable and economic development. The unequal distribution of landownership has been usually considered one of the main causes of the poor performance of Spanish agriculture and the lack of a more rapid industrialization (Nadal Reference Nadal1975; Tortella Reference Tortella2000). Footnote 7 However, as Tortella (Reference Tortella2000, 56) has pointed out, these arguments have not been able to be tested empirically due to the lack of information.

Recent work has begun to fill in this gap by constructing long-term series of inequality at the national level. Prados de la Escosura (Reference Prados De La Escosura2008) has calculated a set of inequality measures for the period going from 1850 to 2000. Footnote 8 His research shows that inequality increased between the mid-nineteenth century and World War I and decreased afterward. Although this downward trend was interrupted during the autarkic decades that followed the Civil War (1940s–50s), the decrease in inequality continued up to the 1980s, when inequality increased again, especially since the beginning of the 1990s. Footnote 9 Important as it is, country-level inequality hides wide differences at more disaggregated levels, an issue that has been hardly explored. Given the sharp regional differences that characterized the Spanish economy, a more spatially disaggregated measure of inequality would drastically improve our understanding of the patterns behind the evolution of income distribution.

To expand our knowledge about these issues, this article analyzes the Spanish experience between 1860 and 1930. Our work provides two main contributions. Firstly, building on earlier work by Williamson (Reference Williamson1997), it constructs a measure of inequality for each one of the Spain’s provinces between 1860 and 1930: an indirect index of inequality defined as the ratio between nominal income per worker and the nominal unskilled wage or Williamson Index (WI). Our data set presents a series of advantages. Most of the international studies employ country-level information, so internal differences at lower levels of aggregation are overlooked. Besides, by focusing on just one country, we avoid the problems that different legal and political regimes impose in cross-country comparisons. In addition, our analysis, unlike other empirical exercises within this literature, is conducted for a historical period that corresponds with the early stages of modern economic growth as stated by Kuznets. This is particularly relevant because cross-country studies have mainly focused, due to data scarcity, on the last decades of the twentieth century or on the period after World War II. Likewise, distributional policies were almost nonexistent during this period, thus enhancing the role of economic forces in explaining the trends in inequality. Lastly, by employing underlying data coming from the same statistical agencies, our study also avoids problems of comparability between different economies, especially acute when comparing data originated in developed and developing countries (Atkinson and Brandolini Reference Atkinson and Brandolini2001; Banerjee and Duflo Reference Banerjee and Duflo2003, 281), or the troublesome conversions of incomes across countries using the purchasing parity power.

Secondly, a model assessing the different causes behind the evolution of inequality is developed and empirically tested. The results confirm the presence of the Kuznets curve. However, although growing incomes did not directly contribute to reducing inequality, at least during the early stages of modern economic growth, other processes associated with economic growth considerably improved the situation of the bottom part of the population. In this sense, the population shift from rural areas to urban and industrial centers, the demographic transition and the spread of literacy, among others, all partly counterbalanced the initial negative impact of economic growth and helped building a more equal society.

The article is structured as follows. “The Early Stages of Economic Growth in Spain, 1860–1930” offers a brief description of the economic context of the Spanish economy in the period under study. In “Measuring Inequality,” the new regional measure of inequality is presented and a first approach to the relationship between this indicator and early economic growth in Spain is conducted. While “The Determinants of Inequality: Empirical Strategy” develops the methodology employed to explore the drivers of inequality, “The Determinants of Inequality: Results” presents the results of the empirical analysis. After assessing that our results hold under different assumptions in “Robustness Tests,” the conclusion summarizes our contribution.

The Early Stages of Economic Growth in Spain, 1860–1930

Economic growth in Spain progressed at a slow pace during the early stages of development. It was only after World War I when GDP growth rates showed a substantial increase (table 1). Structural change in the Spanish economy was also rather limited. The gradual diffusion of industrialization across Europe in the nineteenth century allowed the countries that joined this process to enter the path of what Simon Kuznets defined as “modern economic growth” (Kuznets Reference Kuznets1971). Spain, a middle-sized country lying in the geographical periphery of Europe, strived from the early decades of the nineteenth century to foster its industrial sector but these initial attempts mostly failed (Nadal Reference Nadal1975). In 1860, the workforce employed in the agrarian sector still accounted for two-thirds of the total active population. By 1910, this share had hardly changed. The reallocation of resources from agriculture to other economic sectors then accelerated and a substantial reduction in the share of the agrarian population took place in the interwar years, reaching 45.5 percent of the total population in 1930 (Nicolau Reference Nicolau, Carreras and Tafunell2005).

Table 1. Real GDP, population, and per capita GDP growth, 1850–1929

Source: Prados de la Escosura (Reference Prados De La Escosura2008, 288). Annual average logarithmic rates.

Economic historians have argued that one of the main reasons that explains why the Spanish economy experienced difficulties to converge with the core European countries was the limited industrialization of the country. During the nineteenth century and up to the Civil War (1936–39), Spain indeed lagged behind the major European economic powers and, generally speaking, the Spanish economy had not witnessed the profound transformations that industrialization implies. In parallel to these developments, the demographic transition was delayed relative to the core European countries (Livi-Bacci Reference Livi-Bacci, Pérez Moreda and Reher1988), thus limiting potential improvements in living standards and health (Pérez Moreda et al. Reference Pérez Moreda, Reher and Sanz2016). The picture was not much better in terms of the educational levels attained by the population. Although literacy levels increased from 26 to 71 percent of the adult population between 1860 and 1930 (Núñez Reference Núñez1992), this figure was still below the levels registered in countries like France or England 60 years before (75 and 80 percent, respectively, in 1870).

This general description of the Spanish economy as a whole hides nonetheless widely diverse regional experiences. Firstly, three regions escaped from this general view of economic backwardness: Catalonia, the Basque Country, and Madrid. In the first two cases, a considerable degree of industrial development was achieved, even for European standards (Carreras Reference Carreras1990). Structural change advanced rapidly in these regions that developed a modern manufacturing sector (table 2). In Catalonia, Barcelona witnessed a remarkable increase in the active population enrolled in industrial activities between 1860 and 1930 (being close to a 60 percent of the total active population in 1930). Similarly, in the Basque provinces of Guipúzcoa and Vizcaya, industrial active population doubled and tripled, respectively, almost reaching a 40 percent of the total active population. Likewise, the growth of Madrid, the capital city, brought about the expansion of the manufacturing, construction, and service sectors. As a result, by 1930, while their population only represented 11.8 percent, 5.9 percent, and 3.8 percent, the contribution of Catalonia, Madrid, and the Basque Country to Spanish industrial output was 34.6 percent, 9.3 percent, and 9.2 percent, respectively.

Table 2. Distribution of the active population in selected provinces by sector

Source: Population censuses for the different provinces and Nicolau (Reference Nicolau, Carreras and Tafunell2005) for Spain. Industry includes manufacturing, mining, and construction. The figures for the nonindustrial regions are computed excluding the four industrial provinces in the table.

In this context, the divergent paths followed by the Spanish regional economies and their timing to join “modern economic growth” led initially to an upswing in regional inequality during the second half of the nineteenth century (Rosés et al. Reference Rosés, Martinez-Galarraga and Tirado2010). However, as industrialization spread into an increasing number of provinces in the first decades of the twentieth century, a process of interregional convergence began. A similar trend is observed in terms of labor productivity: an increase in regional disparities in the second half of the nineteenth century and convergence from then on, only interrupted during the aftermath of World War I. These trends have been linked to structural change and the integration of the Spanish commodity markets due to the removal of institutional barriers and improvements in transport infrastructures, particularly the completion of the railway network (Herranz Reference Herranz2007).

The integration of the Spanish labor market also took place in a context characterized by low rates of interregional migration during the nineteenth century and the early decades of the twentieth century. In the decades between 1877 and 1920, the percentage of permanent internal migrations was low and stable, around 2–3 percent of the total population (Silvestre Reference Silvestre2005). These figures increased in the 1920s reaching rates that almost doubled those of the previous decades (4.3 percent). Even in this context of low internal mobility, Rosés and Sánchez-Alonso (Reference Rosés and Sánchez-Alonso2004) show that real wages in Spain’s regions converged throughout the second half of the nineteenth century and the first decade of the twentieth century. While this trend was interrupted in the years following World War I, it resumed in the 1920s.

In a mainly agrarian country, the situation of the agricultural sector also greatly differed between regions. The existence of market incentives, together with the social and environmental conditions that characterized the different rural societies influenced the crop mix and agricultural productivity. While the Southern half of the country and the Castilian plateau, based on a traditional dry-farming cereal agriculture, expanded arable land without appreciably increasing yields, other regions were able to raise productivity through the employment of more intensive techniques and a more diversified agriculture (Gallego Reference Gallego2001; Simpson Reference Simpson1995a). Footnote 10 Such differences were also present in the distribution of land. On the one hand, while large states relying on cheap labor were the norm in Southern Spain, small family farms predominated in Northern Spain and some areas of the Mediterranean coast. On the other hand, although the liberal state promoted the privatization of the commons throughout the nineteenth century, the outcome of the process was geographically diverse (GEHR 1994).

In a similar vein, important regional differences in educational levels were also present (Núñez Reference Núñez1992). Not only the transition to universal literacy was delayed relative to other European countries but also the spread of literacy was geographically uneven. A dual structure was configured during the period under study with the Northern provinces reaching higher rates of literacy than those in the South of the country. There were, however, some exceptions to this general pattern. The Galician provinces in the North, for instance, did perform badly, while the Mediterranean coast was not as backward as the South.

Lastly, it should be noted that the early stages of modern economic growth in Spain coincided with political transformations that are likely to have an influence on the levels of inequality. Liberal reforms were implemented during a period plagued with social instability and political conflict. Footnote 11 This period was followed by the Bourbon Restoration (1874–1923). A parliamentary monarchy was established, and under this system two dynastic political parties, the liberals and the conservatives, alternated in power. However, it appears that, despite the establishment of universal male suffrage in 1890 and its potential effect on the expansion of political participation, the ruling elites managed to keep a good amount of political power during this period (Curto-Grau et al. Reference Curto-Grau, Herranz-Loncán and Solé-Ollé2012; Moreno-Luzón Reference Moreno-Luzón2007). The Restoration ended in 1923 when it was replaced by a military dictatorship led by Primo de Rivera (1923–30). Interestingly, the Second Republic (1931–36), which also brought about the extension of suffrage to women, attempted to undermine the power of the elites, especially of the large landowners, was followed by a coup d’etat organized by the same threatened elites, which triggered the Civil War and eventually overthrew the democratic government.

Measuring Inequality

The analysis of income distribution usually relies on the information provided by household surveys. In particular, most recent studies are interested in the evolution of disposable income, thus considering household incomes once taxes and government transfers have been paid and received, respectively. The data contained in household surveys usually serves as the basis for the computation of Gini coefficients. Footnote 12 Unfortunately, such information is all too often not available for historical periods: household surveys only began to be published after World War II and they were produced mostly in rich countries and not on a regular basis. Therefore, the limited time coverage of the household surveys implies that studies focusing on distant periods have to rely on alternative measures. Historical indicators of inequality are normally constructed using sources that usually offer scattered and more fragmentary data.

Building on earlier work by Williamson (Reference Williamson1997, Reference Williamson2002), an indicator of inequality is developed here. The WI is an indirect index of inequality defined as the ratio between nominal income per worker (y) and the nominal unskilled wage (wunsk ) Footnote 13 :

By dividing the returns to all factors of production per worker by the returns to unskilled labor, the WI compares the bottom of the distribution to the average income. Footnote 14 Examining the Spanish economy as a whole, Prados de la Escosura (Reference Prados De La Escosura2008, 299) has shown that, before 1950, the evolution of the Gini and the WIs was closely correlated. Footnote 15 In particular, the decomposition of the Gini coefficient reveals that inequality in Spain was driven by the gap between the average returns of proprietors and workers, thus justifying the comparison between average income and unskilled wages as the basis for developing these indexes. Footnote 16 Likewise, income taxes and social transfers were negligible during the period under study, which also supports the adequacy of these indicators (ibid., 291).

As captured by the WI, inequality would increase over time if average income per worker increases more than the unskilled (agrarian) wage. Alternatively, if the improvement in unskilled wages exceeds that of the average income per worker, income distribution would become less unequal. Given that we adopt a regional approach, it is worth mentioning that spatial inequality contributes to personal inequality (Kanbur et al. Reference Kanbur, Venables and Wan2005). In the case of Spain, as mentioned in the previous section, nominal regional income per worker differentials increased in the second half of the nineteenth century and decreased afterward, except in the aftermath of World War I. In this regard, industrializing regions recorded higher rates of economic growth, GDP per capita, and productivity. Thus, the level of inequality and its changes over time would depend on to what extent economic progress in each Spanish province translated into higher unskilled wages relative to the evolution of the average income per worker. Footnote 17

The WI has been computed for the Spanish provinces during the period of analysis (see the Supplemental Appendix for methodology and sources). At the Spanish level, as previously mentioned, this indicator steadily increased between the 1850s and the end of World War I when it markedly declined up to the 1930s (Prados de la Escosura Reference Prados De La Escosura2008, 293). This evidence thus displays a U-inverted shape that is consistent with the Kuznets hypothesis. However, compared to the evolution of Spain as a whole, a much more complex picture appears when the regionally disaggregated information is considered. Firstly, figure 1 portrays the regional picture and its evolution over time. Yet, extracting general patterns from the observation of the maps is not straightforward. While inequality declined in some provinces, it increased in others. The values of the WI by year and province can be consulted in table A1 in the Supplemental Appendix.

Figure 1. Income inequality in Spain (Williamson Index), 1860–1930.

Secondly, figure 2 plots each province’s inequality index against their level of real income per capita in 1860, 1900, and 1930. To provide a representation of the relationship between economic growth and inequality over time, a quadratic function is fitted to the observations for each period. According to this graph, richer provinces show higher levels of inequality, at least during the first stages of economic growth. Consistent with the Kuznets’s hypothesis, the WI seems to have increased as incomes grew, a relationship that weakened over time as the Spanish economy developed. Footnote 18 Next sections explore this regional variation to fully assess the distinctive impact of growing incomes and economic development on inequality levels. To do so, other potential factors influencing these processes are also taken into account.

Figure 2. Williamson Index, 1860–1930.

The Determinants of Inequality: Empirical Strategy

As explained in the introduction, because of the pioneering article by Kuznets (Reference Kuznets1955), the relationship between economic growth and inequality has received considerable attention (Allen Reference Allen2009; Barro Reference Barro2000, Reference Barro2008; Deininger and Squire Reference Deininger and Squire1998; Gallup Reference Gallup2012; Li et al. Reference Li, Squire and Zou1998; Lindert Reference Lindert, Atkinson and Bourguigon2000b; Lindert and Williamson Reference Lindert and Williamson1985; Milanovic et al. Reference Milanovic, Lindert and Williamson2011; Morrison Reference Morrison, Atkinson and Bourguignon2000). Footnote 19 While some of these studies defend that inequality grows during the early stages of modern economic growth to drop afterward as the economy develops further, others claim that this connection is far from clear. In this section, we test the Kuznets’s hypothesis and examine the potential determinants of inequality using the indicator developed in the preceding text. Relying on a panel data set at the Spanish provincial level at 1860, 1900, 1910, 1920, and 1930, we estimate the following model:

$${Y_{it}} = {\beta _1}GDPp{c_{it}} + {\beta _2}GDPpc{\left( {squared} \right)_{it}} + {\beta _3}IN{D_{it}} + {\beta _4}UR{B_{it}} + {\beta _4}POPDEN{S_{it}} + {\beta _5}FER{T_{it}} + {\beta _6}LI{T_{it}} + {\beta _7}COM{M_{it}} + {a_t} + {u_{it}}$$

$${Y_{it}} = {\beta _1}GDPp{c_{it}} + {\beta _2}GDPpc{\left( {squared} \right)_{it}} + {\beta _3}IN{D_{it}} + {\beta _4}UR{B_{it}} + {\beta _4}POPDEN{S_{it}} + {\beta _5}FER{T_{it}} + {\beta _6}LI{T_{it}} + {\beta _7}COM{M_{it}} + {a_t} + {u_{it}}$$

While Y it denotes the level of inequality in province i at time t, GDPpc it and its square attempt to capture the inverted U-relationship between real income per capita and inequality. The other terms refer to a set of variables that account for other potential determinants of inequality as suggested by the literature and explained in the text that follows. In addition, a t introduces fixed time effects. Footnote 20

Firstly, Kuznets (Reference Kuznets1955) theorizes that, during the early stages of development, inequality is driven up by the shift of the population from agriculture to the urban and industrial sectors where incomes and inequality tend to be higher, so the fraction of the working force employed in the industrial sector (IND it ) is included in the model. Likewise, increasing market opportunities, which can be accounted for not only by income per capita but also by urbanization (URB it ) and population density (POPDENS it ), may promote inequality due to larger potential gains and risks. However, by providing working opportunities, both the industrial and the urban sector may exert a beneficial influence on wages, potentially decreasing inequality levels. Footnote 21 In the case of Spain, several works have shown the relevance of agglomeration economies in explaining both the large increase in the spatial concentration of manufacturing before the Civil War (Martinez-Galarraga Reference Martinez-Galarraga2012; Rosés Reference Rosés2003; Tirado et al. Reference Tirado, Paluzie and Pons2002) and the long-term evolution of population (Ayuda et al. Reference Ayuda, Collantes and Pinilla2010; Beltrán Tapia et al. Reference Beltrán Tapia, Díez-Minguela and Martinez-Galarraga2018).

Apart from these structural changes, demographic pressures may have also played a role in this process because population growth, by expanding the labor force supply, tends to prevent wages from rising (Lindert and Williamson Reference Lindert and Williamson1985, 354–55). Similarly, demographic growth in rural areas may entail an increase in land prices and in the number of landless peasants (Morrison Reference Morrison, Atkinson and Bourguignon2000, 253). In this sense, during the early stages of economic development, household behavior underwent fundamental transformations such as the increase in female labor force participation, which led to a decline in fertility rates and the onset of demographic transition, thus potentially alleviating demographic pressures (Galor Reference Galor2011, 123–24). The shift from “quantity to quality” in the patterns of fecundity resulted in increasing levels of human capital that may also have affected inequality levels (Becker et al. Reference Becker, Cinnirella and Woessmann2010). In the case of Spain, it has been argued that the increase in children’s literacy at the beginning of the twentieth century is related to the decline in fertility thus offering evidence in favor of the existence of a quantity-quality trade-off (Basso Reference Basso2012).

Plus, in an era in which primary education was the main source of human capital differences (Núñez Reference Núñez, Jerneck, Morner and Tortella2005, 140), the spread of schooling and literacy reduced the high concentration of human capital in the top part of the distribution and, therefore, may have levelled off the playing field (Galor Reference Galor, Aghion and Durlauf2005, 212–14; Morrison Reference Morrison, Atkinson and Bourguignon2000, 252). Footnote 22 According to Rajan and Zingales (Reference Rajan and Zingales2006), elites tried to block the diffusion of education so as to prevent both large-scale reforms and a reduction of the rents accruing to the already educated. However, Galor (Reference Galor2011) suggests that, as the industrialization process advanced, physical capital accumulation was replaced by human capital accumulation as the prime engine of economic growth. In that context, while landowners would favor policies aimed at depriving the masses from education to reduce the mobility of rural workers and keep rural wages low, capitalists or industrialists benefited from human capital accumulation and thus had incentives to support education policies. In a recent study, Beltrán-Tapia and Martinez-Galarraga (Reference Beltrán Tapia and Martinez-Galarraga2018) show, using information from districts (partidos judiciales) in 1860, that there is a negative relationship between the fraction of farm laborers and male literacy rates. Further, they argue that as well as supply factors, demand effects also played a significant role in explaining the negative impact of inequality on education. Footnote 23 Therefore, proxies capturing fertility (FERT it ) and educational levels (LIT it ) are included in the analysis.

The period under analysis also coincides with a massive privatization of common lands in Spain (Beltrán Tapia Reference Beltrán Tapia2016; Iriarte Reference Iriarte2002). By providing pasture, wood, and fuel, among other products, including the possibility of temporary cropping, the commons constituted an important source of complementary income. The disrupting impact of the British enclosures on the living standards of the bottom part of the rural population has been repeatedly stressed (Allen Reference Allen1992; Humphries Reference Humphries1990; Neeson Reference Neeson1993), although these claims have been contested (Clark and Clark Reference Clark and Clark2001; Shaw-Taylor Reference Shaw-Taylor2001). Spanish historiography has also argued that the loss of these collective resources negatively affected rural households but the lack of information on inequality has prevented drawing stronger conclusions (Beltrán Tapia Reference Beltrán Tapia2016; Jiménez Blanco Reference Jiménez Blanco2002; Tortella Reference Tortella2000). Interestingly, although enclosure was highly intense in some regions, other areas were able to preserve large tracts of the commons (GEHR 1994). This heterogeneity therefore allows for empirically testing the effect of the persistence of common lands (COMM it ) on inequality. Table 3 presents summary statistics of all variables employed.

Lastly, a set of time dummies (a t ) accounts for other changes, apart from the economic transformations already considered, which may have affected the Spanish economy, such as the establishment of universal male suffrage in 1890. Recent literature on institutions has stressed that the transition from an oligarchy run by the elites to a more democratic political system involved wide-ranging effects on the economies undergoing those institutional changes (Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2000; Engerman and Sokoloff Reference Engerman and Sokoloff2002; Lindert Reference Lindert2003). The Spanish literature argues, however, that, despite legal changes, economic and political elites were able to keep the political system under their control through different mechanisms such as widespread vote buying, coercion, and mass fraud, among other practices, at least until well into the twentieth century (Curto-Grau et al. Reference Curto-Grau, Herranz-Loncán and Solé-Ollé2012; Moreno-Luzón Reference Moreno-Luzón2007). Trade unions, nonetheless, began to exert an important influence on the labor markets during this period (Prados de la Escosura Reference Prados De La Escosura2008, 303). Given the difficulty of constructing indicators that may capture regional differences in the quality of institutions, the potential impact of these political developments on inequality will therefore be assessed by the time dummies.

Table 3. Summary statistics

Source: See text and Supplemental Appendix.

The Determinants of Inequality: Results

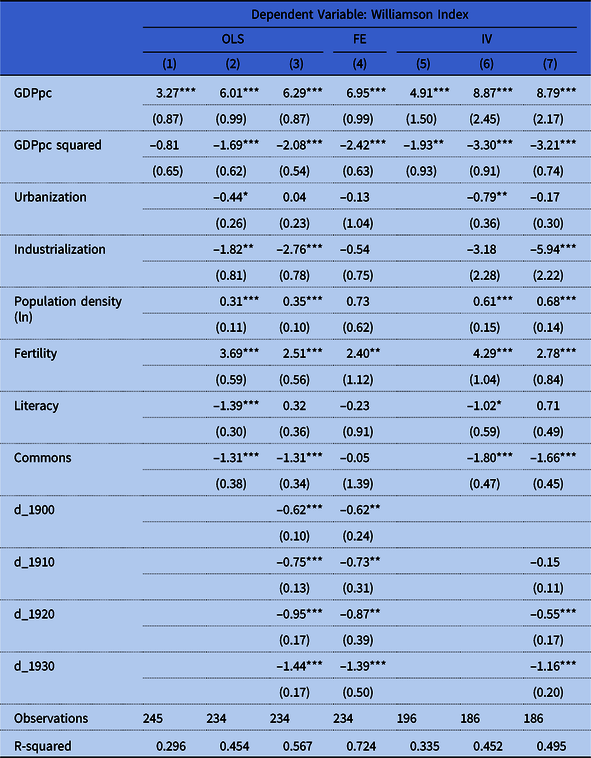

Table 4 reports the results of estimating equation (2) using different methods. Column (1) presents the baseline specification using OLS. Columns (2) and (3) add the set of controls and the time dummies explained in the preceding text, respectively. Footnote 24 To further capture the peculiarities of each province, column (4) employs a fixed-effects specification. The within-province variation of some of the explanatory variables is, however, small, so this specification cannot fully account for their impact on inequality. Despite the inclusion of different factors potentially explaining inequality trends, a potential bias coming from unobserved heterogeneity and simultaneity is worrisome. An instrumental variable approach is therefore conducted using the lagged values of the explanatory variables as instruments, thus allowing us to alleviate endogeneity issues. Footnote 25 Columns (4) to (6) repeat the previous exercise but employing now the IV specification. Footnote 26 Admittedly, by following this approach, we lose one period and our sample is reduced to years 1900, 1910, 1920, and 1930. However, due to the lack of a different instrument, this is the best available strategy to test the robustness of our results. Moreover, despite the increase in standard errors resulting from both implementing the instrumental variable approach and the loss of observations, the IV estimates hardly change and remain statistically significant. Footnote 27

Table 4 Determinants of inequality

Robust standard errors between brackets; *, **, or *** denotes significance at 10, 5, or 1 percent level. For simplicity, the intercept is not reported.

The reported results strongly confirm the presence of the Kuznets curve in the early stages of modern economic growth in Spain. Footnote 28 Inequality tended to rise as the economy grew, but this relationship gradually became weaker and eventually reversed. According to the estimates in column (5), the inflexion point is reached at an income per capita around 1,272 pesetas, when the WI tended to decline thereafter. It is worth noting that the average real GDP per capita went from 359 pesetas in 1860 to 487 and 672 pesetas in 1900 and 1930, respectively. Interestingly, in spite of focusing on a period that only captures the initial stages of modern economic growth, this exercise is able to identify the changing trend in the relationship between income and inequality. Using a long-term longitudinal data at the country level from 1850 to 2000, Prados de la Escosura (Reference Prados De La Escosura2008, 300) also detects the presence of a Kuznets curve in Spain. In that case, the WI suggests that the upswing of inequality ends after World War I.

It should be stressed that the relationship between income and inequality does not disappear when other potential determinants of inequality are included in the model, in spite of being highly correlated with economic development. This means that, apart from the economic, social, and political transformations that usually accompany this process, and that also involve distributional consequences, income still exerts an independent effect. Given that the coefficient almost doubles in size when these variables are introduced, it can be inferred that these other factors were partly offsetting the effect of economic growth on inequality. Footnote 29 The positive dimension of this relationship is likely to be due to the expanding opportunities and risks brought about by increasing incomes. Milanovic et al. (Reference Milanovic, Lindert and Williamson2011) indeed stress that economic growth expands the maximum feasible inequality. Explaining the negative dimension attached to the coefficient on GDP squared is more challenging. Bourguignon (Reference Bourguignon, Aghion and Durlauf2005, 1739–40) argues that, in developing economies, markets function very imperfectly, especially credit markets, resulting in “unbalanced” growth. As the economy develops and markets become better integrated, the impact of growth upon social structures becomes less disrupting and may facilitate that larger parts of the population benefit from expanding opportunities (Dercon Reference Dercon2009).

Regarding structural change, although the shift from agriculture to industry has often been linked to increasing inequality following Kuznets’s seminal contribution (Reference Kuznets1955), our results show that other processes correlated with the emergence of an industrial sector, such as urbanization or increasing population density, may explain that trend. Footnote 30 Analyzing the British case, Lindert and Williamson (Reference Lindert and Williamson1985, 367) were indeed very cautious about the supposed effect of the Industrial Revolution on inequality levels. Industrialization, on the contrary, at least in the Spanish case, appears to have reduced inequality by opening up new job opportunities for the lower classes, not only consequently raising their salaries but also increasing their room to maneuver in their relationships with the well-off (Gallego Reference Gallego2007). The availability of industrial jobs meant, for instance, that peasants could threaten to “exit” if their landlords did not provide better wages or rents. Likewise, industrialization may have reduced underemployment in rural areas (Morrison Reference Morrison, Atkinson and Bourguignon2000, 255).

Alternatively, demographic pressures, as shown by the coefficients on population density and fertility, together with expanding economic opportunities, do explain rising inequality trends. In this sense, Kuznets’s intuition (Reference Kuznets1955, 18) that higher birth rates would be unfavorable to the relative economic position of lower-income groups is strongly validated by the data. Also, by affecting the distribution of population and the labor force supply, migration processes are likely to have had opposite effects: releasing demographic pressures in sending areas but exacerbating them in receiving regions (Betrán and Pons Reference Betrán and Pons2011; O’Rourke and Williamson Reference O’Rourke and Williamson1999). Footnote 31 Migrations also have an impact on the age structure of the population. Emigration is highly selective and the group of population that migrates usually consists of young adult males. International emigration of workers increases the dependence ratio in the regions of origin regardless of the destination of these migrants. This effect can be even stronger if migration takes place within the domestic market. In this case, the host regions also receive people of working age, thus reducing their dependency ratio (Williamson Reference Williamson2001). There is indeed evidence that internal and international migration gradually increased during the period under analysis (Sanchéz Alonso Reference Sánchez-Alonso2000; Silvestre Reference Silvestre2005, Reference Silvestre2007).

By contrast, and as expected, increasing educational levels also help reducing inequality (Barro Reference Barro2000, 21). Footnote 32 The diffusion of literacy seems to have facilitated reducing the concentration of human capital in narrow segments of the population (Morrison Reference Morrison, Atkinson and Bourguignon2000). Although its effect disappears when time dummies are added, this may be due to the association between the spread of political voice, state intervention, and the provision of schooling, what would imply multicollinearity problems. In this sense, Lindert (Reference Lindert2003) finds an important link between the expansion of voting rights and increasing schooling enrollment rates. There is indeed evidence that the implementation of a public schooling system largely explains most of the growth in literacy levels in Spain between 1860 and 1930. Footnote 33

Likewise, the stock of common lands shows a negative and statistically significant influence on inequality. The commons seem to have been a crucial asset for the rural population. Not only did these collective resources complement households’ incomes by supplying a variety of goods and services but also their existence influenced the standards of living of the rural working classes by increasing their bargaining power in the labor market (Gallego Reference Gallego2007; Jiménez Blanco Reference Jiménez Blanco2002). Footnote 34 Those regions where large tracts of common lands survived enjoyed higher levels of life expectancy and heights. The link between the commons and inequality is consistent with anecdotal evidence and the historiography on the driving forces behind the privatization of these resources, which stresses how powerful elites promoted this process and became the main beneficiaries from it, especially after 1860 (Jiménez Blanco Reference Jiménez Blanco2002). Footnote 35 A similar story appears evident from the English Parliamentary enclosures where a vast redistribution of agricultural income from the rural poor to the landowners occurred (Allen Reference Allen1992; Humphries Reference Humphries1990).

Lastly, it should be stressed that the time dummies show that, holding everything else fixed, inequality decreased under the period of analysis. Although this timing coincides with the modernization of the economy and the increasing importance of dynamic urban centers, their effect is already accounted for by the control variables. The independent effect of the time dummies may, therefore, be linked to other factors. The literature has pointed to the effects derived from the transition from an oligarchy run by the elites to a more democratic political system (Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2000; Engerman and Sokoloff Reference Engerman and Sokoloff2002; Lindert Reference Lindert2003). The importance of enfranchisement and electoral dynamics within semidemocratic political systems has been stressed for the Spanish case during the monarchic “Restoration” (1874–1923), in which the two dominant parties alternated in office (Curto-Grau et al. Reference Curto-Grau, Herranz-Loncán and Solé-Ollé2012). Although economic and political elites firmly controlled the Spanish political system by widespread vote buying, coercion, and mass fraud, together with promises of individual favors and pork barrel politics, the ability to do so weakened over time as elected candidates from third parties began to gradually gain importance in the political arena from the end of the nineteenth century onward. In this sense, not only the establishment of universal male suffrage in 1890 may have opened new paths for mass political participation but also may have partially corrected some of the malfunctions of the system. Footnote 36 Likewise, the political reforms that a wider political representation usually involves, such as social reforms, increased taxation, or the extension of education, are likely to need time to begin making an impact (Lindert Reference Lindert2003, 342). Inequality also seems to have been considerably reduced during the 1910s and 1920s coinciding with the disruptive effects of the World War I and the increasing role of trade unions in fostering relative wages (Prados de la Escosura Reference Prados De La Escosura2008, 303). Other processes, such as the trade policy or the effect of technological innovation, nonetheless may have also contributed to explaining these trends. Further research is needed to be able to disentangle between these competing explanations. Footnote 37

Robustness Tests

The results reported in the preceding text might be influenced by the way the measure of inequality is constructed. On the one hand, the WI compares income per worker (y) with the unskilled wage (wunsk ). However, it can be argued that, as an economy develops, the share of unskilled workers will drop. If that was the case, comparisons over time could become inconsistent. To overcome this potential problem economic historians have also relied on an inequality measure similar to the WI, which is based not only on the returns of unskilled workers but also on the average returns to all labor (avg w). The denominator of the equation thus includes both the returns of unskilled and skilled workers. This inequality measure can be expressed as:

Prados de la Escosura (ibid., 293) computed WIs both using the unskilled wage and the average wage for Spain as a whole. His results show that both indicators followed a similar trend from the mid-nineteenth century up to the 1950s. This evidence confirms the expected result given that, during the early stages of development, skilled labor represented a small proportion of the total labor force in Spain (ibid., 292). Footnote 38

Yet, as explained in “Measuring Inequality,” structural change in Spain proceeded at different speed across provinces and, consequently, both indicators may differ for different areas in Spain. In particular, if an increase in the share of skilled labor accompanied structural change, this indicator would show disparities both across provinces and compared with the WI. We have thus computed the WI using both unskilled and skilled wages (see Supplemental Appendix for details) and compared this measure with the original version of the WI. As expected, both indicators are highly correlated (r = 0.81). Reassuringly, estimating equation (2) using this alternative indicator hardly change the results reported in the preceding text (see table A2 in the Supplemental Appendix).

We are aware of the potential endogeneity arisen from the fact that one of our independent variables, income per capita, is also employed when computing the WI. This issue may affect the reliability of the estimated coefficients. Relying on other studies that proxy economic development using urbanization ratios (Acemoglu et al. Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2005, 552), we have also reestimated our model employing urbanization rates as a proxy for income per capita. The results of this analysis, reported in table A3 in the Supplemental Appendix, do not qualitatively change the interpretation here, thus mitigating this concern.

Likewise, the effect on inequality of the variables we have analyzed throughout the article might be capturing the influence of other economic and social processes for which we have not yet accounted. Although we have mitigated this concern by implementing different models (Fixed Effects and Instrumental Variables), we now further address this issue by repeating our main specification but adding other variables that may affect inequality. Firstly, to account for the effect of international trade, we test whether our results are robust to the inclusion of two new variables (distance to Madrid or Barcelona and a dummy variable for being a coastal province) and the corresponding interactions with time dummies. The intuition behind this is that if the evolution of international trade had an effect on inequality, this impact would be larger in areas close to international markets (coastal areas and provinces closer to the main Spanish cities: Madrid or Barcelona). The results of this exercise, as reported in table A4 in the Supplemental Appendix, do not alter the image portrayed in the previous section.

Similarly, migratory flows might be filtering how inequality evolves in response to changes in the variables under study. However, controlling for migration does not alter the results (table A5). Footnote 39 In addition, given that our results might depend on how regional GDPs have been adjusted to account for differences in costs of living between provinces, we have carried out an additional robustness test using wheat prices as controls. Footnote 40 As shown in table A6, our results remain virtually identical.

Lastly, given that the literature on Spain tends to stress the differences between Northern and Southern Spain in terms of the importance of landless laborers and the number of days worked (Simpson Reference Simpson1995a), we have further tested the robustness of our results by allowing the possibility that these two macroregions followed different paths. To do so, we have included a time dummy for the Southern provinces, so the analysis can then focus on the variation within these macroregions. To account for a distinct evolution over time, we have also interacted this variable with time dummies. As reported in table A7 in the Supplemental Appendix, results are hardly altered.

Conclusion

In a period in which other potential indicators are lacking, the WI developed here enhances our knowledge about the evolution of Spanish inequality at the provincial level during the early stages of modern economic growth. Importantly, this study shows that country-level inequality hides important differences at more disaggregated regional levels. The analysis also contributes to the debate on the causes behind inequality. While growing incomes appear to have fostered inequality (although at a decreasing rate), other processes associated with economic development, such as the rural exodus to urban and industrial centers, the demographic transition, the spread of literacy, or the effect of extending political participation helped improving the relative standards of living of the lower classes. Therefore, the potential of economic growth to improve the lot of the bottom part of the population becomes conditional on its ability to expand the opportunities available to increasingly wider segments of the population.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ssh.2019.44